1. Introduction

Endometrial cancer (EC) is most often confined to the uterus, with lymph node metastases occurring infrequently [

1]. Sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsy is now recognized as the standard method for surgical staging in EC, offering a less invasive alternative to full lymphadenectomy while maintaining high diagnostic accuracy for metastasis detection [

2,

3]. This approach reduces the risk of complications such as lymphedema or lymphocyst formation, which is particularly important in obese patients—a common comorbidity in EC (74.4% of patients in our cohort had a BMI ≥30).

Various tracers are used for SLN mapping, including technetium-99m (Tc-99m), indocyanine green (ICG), and blue dyes (e.g., Patent Blue). Tc-99m is a widely used radiotracer due to its stability, deep tissue penetration, long retention time in lymph nodes, and its applicability in both planar scintigraphy and hybrid SPECT/CT imaging [

4,

5,

6]. Scintigraphy enables the assessment of SLN presence, its unilateral or bilateral location, and helps plan alternative strategies (e.g., dye usage) in case of non-detection [

7,

8,

9]. Although Tc-99m is highly effective in EC, its utility in other cancers (e.g., melanoma, head and neck cancer) confirms the versatility of this method [

4,

10].

The literature suggests a superiority of hybrid SPECT/CT imaging over planar scintigraphy, both in tumors with complex anatomy [

10,

11] and in gynecologic malignancies [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. However, the effectiveness of sentinel lymph node (SLN) detection depends significantly on the timing of imaging. In most comparative studies, SPECT/CT was performed within so-called short protocols — that is, within three hours after Tc-99m injection — which may not allow for optimal tracer accumulation in SLNs [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16].

In our previous study [

17], we demonstrated high sensitivity of the 18-h planar scintigraphy protocol in a smaller cohort, with no cases of false uptake (“empty pockets”) and minimal background signal from the injection site.

In the present study, we expanded our prior analysis [

17] to a cohort of 125 patients with early-stage endometrial cancer (FIGO I–II), comparing three imaging protocols for sentinel lymph node (SLN) detection: 30-minute planar scintigraphy, SPECT/CT at 1 hour, and 18-hour planar scintigraphy. We evaluated the learning curve effect on bilateral SLN detection and applied quantitative metrics (contrast factor [C-factor] ≥3.61, signal-to-noise ratio [SNR] ≥1.46) for objective image quality assessment.

The aim of the study was to evaluate whether delayed planar scintigraphy with Tc-99m is sufficiently sensitive and clinically effective (including positive and negative predictive values (PPV, NPV) to replace SPECT/CT in standard SLN detection in EC, thereby reducing radiation exposure, cost, and preoperative preparation time.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

This was a retrospective cohort analysis conducted at the Maria Sklodowska-Curie National Research Institute of Oncology, Krakow Branch, Poland, between December 2016 and April 2025. Patients with endometrial cancer (EC) preoperatively classified as FIGO stage I–II (2009 classification), based on clinical and imaging assessment [

18], and who underwent sentinel lymph node (SLN) mapping, were included. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the National Research Institute of Oncology (approval no. 10/2025). All data were anonymized, and patient consent was obtained in accordance with the "Ethics Statement" and "Informed Consent" sections.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Eligible patients had histologically confirmed stage I–II endometrial cancer, had received no neoadjuvant therapy, and had complete clinical and pathological data. Exclusion criteria included advanced-stage disease (FIGO III–IV), age below 18 or above 85 years, and contraindications to surgical treatment. Of the 131 patients initially enrolled in the long planar scintigraphy protocol, six were excluded due to incomplete SPECT/CT imaging data, resulting in a final cohort of 125 patients for analysis.

2.3. Sentinel Lymph Node Mapping and Imaging

All patients underwent total hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy or salpingectomy, and SLN mapping using technetium-99m (Tc-99m) human serum albumin colloid (NanoColl, GE Healthcare). A dose of 120 MBq of Tc-99m was injected into the cervix at the 3 and 9 o'clock positions, both superficially (2–3 mm) and deeply (10–15 mm) into the cervical stroma using a 21G needle.

Sentinel lymph nodes were defined as the first lymph nodes demonstrating radiotracer uptake in a given imaging protocol:

Early planar scintigraphy – performed 30 minutes after injection (~113 MBq, acquisition time 600 s) using a Mediso AnyScan SC gamma camera.

SPECT/CT – performed 1hours after injection (~107 MBq, acquisition time 600 s) using the Mediso AnyScan SPECT/CT system; the additional radiation dose from the CT component was estimated at 1–4 mSv [

19].

Delayed planar scintigraphy – performed 18 hours after injection (~15 MBq, acquisition time 600 s) on the day of surgery.

Intraoperative SLN localization was guided by the results of delayed planar scintigraphy and performed using a handheld gamma probe (Gamma Finder 2, World of Medicine). Identified SLNs were anatomically classified as obturator, internal iliac, external iliac, common iliac, or para-aortic, and ex vivo gamma probe confirmation was performed.

In cases of intense radiotracer accumulation at the injection site — observed in two patients as strong cervical hotspots — hysterectomy was performed prior to SLN identification with the gamma probe, enabling successful visualization of SLNs located in close proximity to the cervix.

Overall detection rate was defined as the percentage of patients with at least one SLN visualized in a given imaging protocol. For the 18-hour protocol, detection was additionally confirmed intraoperatively and histologically. Bilateral detection was defined as the identification of at least one SLN on each side of the pelvis.

2.4. Histopathological Analysis

Excised SLNs were fixed in formalin, sectioned into 2 mm slices, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Cytokeratin immunohistochemistry was used for metastasis detection and categorized as macrometastasis (>2 mm), micrometastasis (0.2–2 mm), or isolated tumor cells (≤0.2 mm).

2.5. Quantitative Metrics and Statistical Analysis

Scintigraphic image quality was assessed using the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR, threshold ≥1.46) and contrast factor (C-factor, threshold ≥3.61), in accordance with the methodology of Szatkowski et al. [

17]. Regions of interest (ROIs) for SLNs were defined at 50% of the maximum pixel value, while background activity was measured in areas without tracer uptake [

20]. The frequency of false-positive uptake ("empty pockets") in fatty tissue was also recorded.

Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics v28.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Comparisons between imaging protocols (30-minute planar, SPECT/CT, 18-hour planar) were performed using ANOVA for quantitative metrics (SNR, C-factor). Paired t-tests were used for within-subject comparisons of SNR and C-factor. SLN detection and bilateral identification rates were analyzed using the chi-square test. A potential learning curve effect was evaluated by comparing bilateral detection rates in the last 17 consecutive cases with the overall cohort. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

2.6. SLN Evaluation Parameters

The following metrics were assessed:

Detection sensitivity: The percentage of patients with at least one SLN identified and confirmed intraoperatively and histologically. This metric was based on delayed (18-hour) scintigraphy, which was used for surgical planning.

Bilateral detection: The proportion of cases with at least one SLN identified on each side of the pelvis.

Positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV): Calculated based on intraoperative and histopathological verification of SLNs identified on 18-hour scintigraphic images.

Quantitative metrics: Mean values and standard deviations of the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and contrast factor (C-factor), analyzed independently for each imaging protocol.

2.7. Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Maria Sklodowska-Curie National Research Institute of Oncology, Krakow Branch, Poland (date: 9 th January 2025, Approval No. 10/2025).

2.8. Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. All data were anonymized prior to analysis.

3. Results

The study cohort included 125 patients with endometrial cancer, with obesity (BMI ≥30) present in 74.4% of cases (

Table 1). The 18-hour planar scintigraphy protocol achieved the highest SLN detection sensitivity (94.4%, 118/125) compared to SPECT/CT (87.2%, 109/125; OR = 2.48; 95% CI: 0.98–6.27; p = 0.051) and the 30-minute scintigraphy protocol (72%, 90/125) (

Table 2,

Figure 3). Bilateral SLN detection in the 18 h protocol was 80.8% (101/125) versus 73.6% (92/125) with SPECT/CT (OR = 1.51; 95% CI: 0.83–2.75; p = 0.16), with improvement to 88.2% (15/17) in the last 17 cases, suggesting a learning curve effect. The results of the 30-minute and SPECT/CT protocols were not intraoperatively verified. Scintigraphic images in the 18 h protocol demonstrated improved SLN visualization and minimal background signal compared to the 30-minute protocol (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). No cases of so-called “empty pockets” (false uptake in fatty tissue) were observed in the 18 h protocol, as confirmed intraoperatively and histopathologically. Due to the lack of surgical verification in the 30-minute and SPECT/CT groups, the presence or absence of empty pockets in these protocols cannot be definitively assessed.

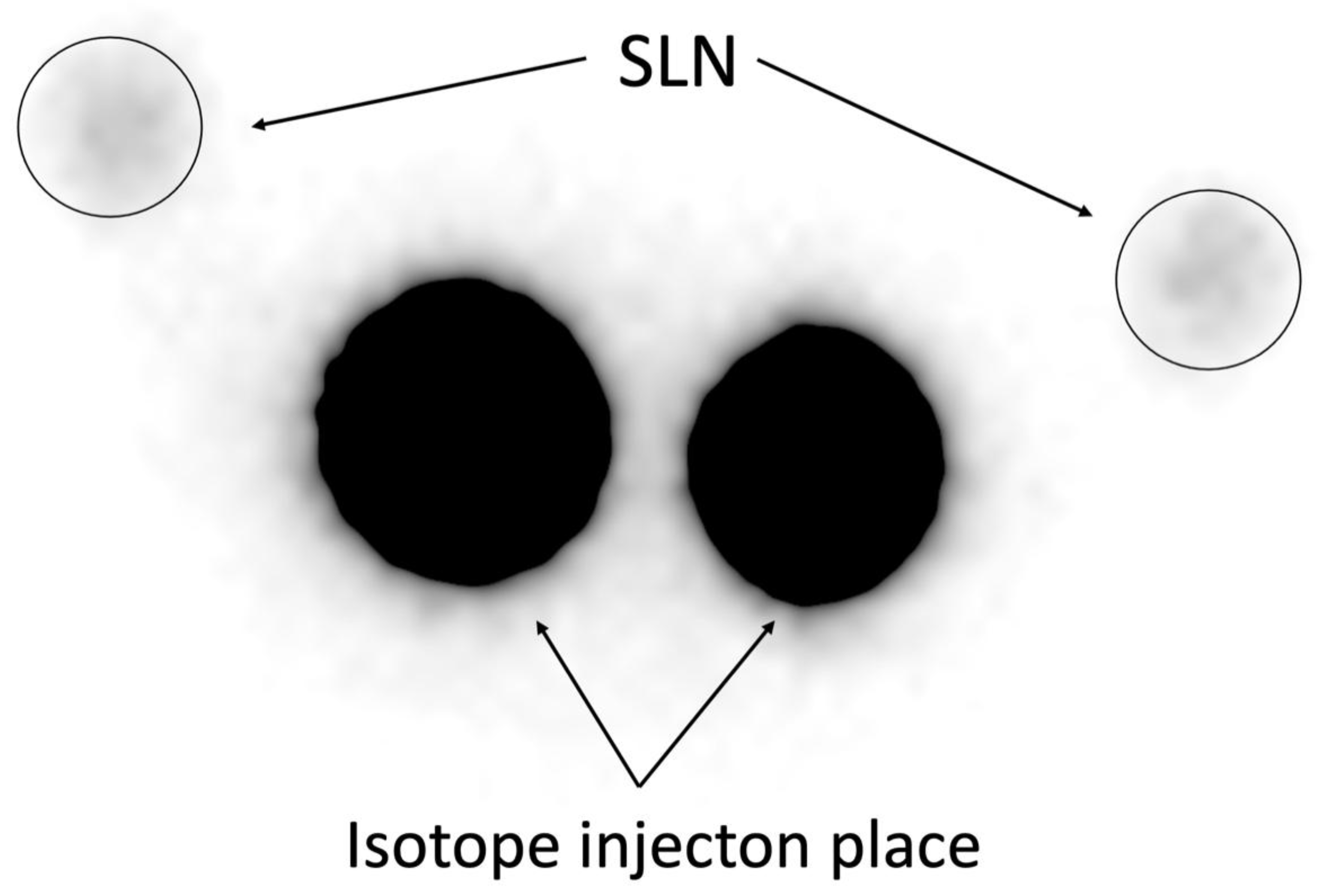

Figure 1.

30-Minute Planar Scintigraphy. Representative image of planar scintigraphy performed 30 minutes after Tc-99m injection (113 MBq), showing SLN uptake with notable background signal interference, resulting in lower detection sensitivity (72,00%,

Table 2). .

Figure 1.

30-Minute Planar Scintigraphy. Representative image of planar scintigraphy performed 30 minutes after Tc-99m injection (113 MBq), showing SLN uptake with notable background signal interference, resulting in lower detection sensitivity (72,00%,

Table 2). .

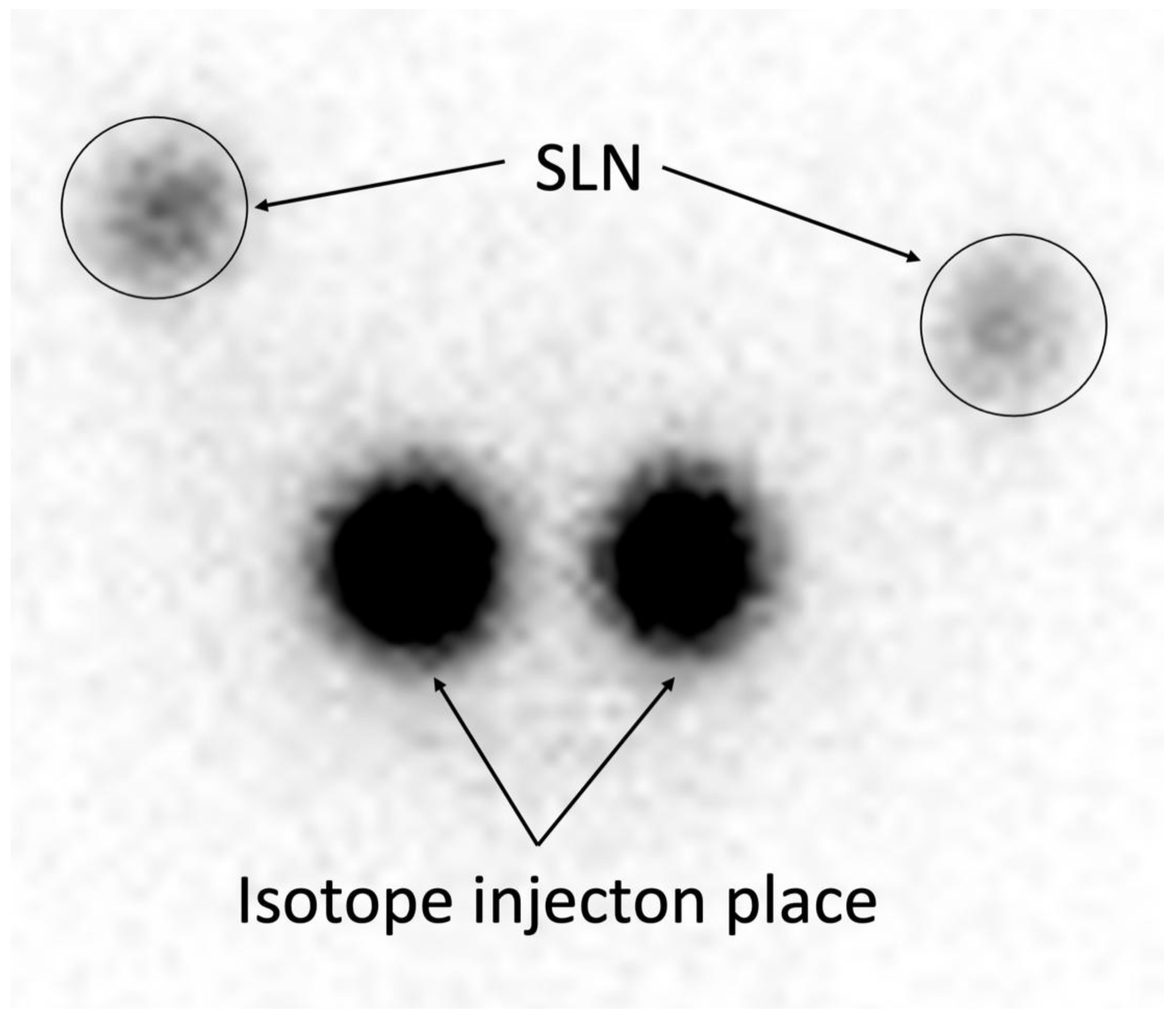

Figure 2.

18-Hour Planar Scintigraphy. Representative image of planar scintigraphy performed 18 hours after Tc-99m injection (15 MBq), demonstrating clear SLN visualization with minimal background interference, achieving high detection sensitivity (94,40%) and 100% PPV/NPV (

Table 2).

Figure 2.

18-Hour Planar Scintigraphy. Representative image of planar scintigraphy performed 18 hours after Tc-99m injection (15 MBq), demonstrating clear SLN visualization with minimal background interference, achieving high detection sensitivity (94,40%) and 100% PPV/NPV (

Table 2).

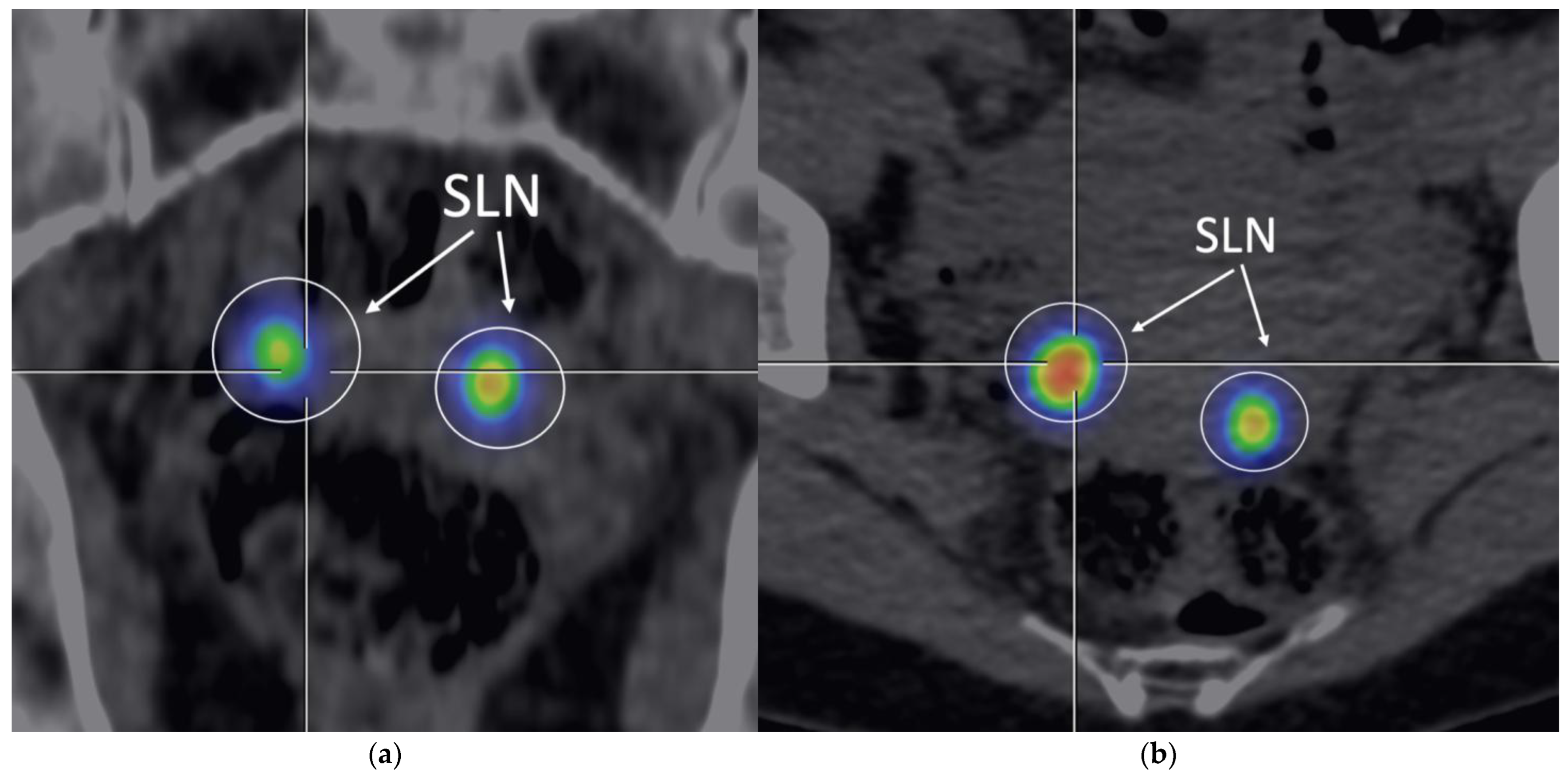

Figure 3.

SPECT/CT. Representative image of SPECT/CT performed 1hours after Tc-99m injection (107 MBq), showing SLN uptake with moderate background signal, with a detection sensitivity of 87,20% (

Table 2). (

a) Frontal view; (

b) Transversal view.

Figure 3.

SPECT/CT. Representative image of SPECT/CT performed 1hours after Tc-99m injection (107 MBq), showing SLN uptake with moderate background signal, with a detection sensitivity of 87,20% (

Table 2). (

a) Frontal view; (

b) Transversal view.

The SLN detection sensitivity in patients with BMI ≥30 was 94% (87/93) for the 18 h protocol, 86% (80/93) for SPECT/CT, and 71% (66/93) for the 30-minute protocol. All 118 cases with positive 18 h scintigraphy were confirmed intraoperatively and histopathologically as lymphatic tissue, resulting in a positive predictive value (PPV) of 100% (95% CI: 96.9–100%). In the 7 cases where SLNs were not visualized with 18 h scintigraphy, the absence of intraoperative detection was also confirmed, suggesting a negative predictive value (NPV) of 100% (95% CI: 59.0–100%), though the limited number of negative cases reduces statistical power.

The total number of SLNs visualized in the 18 h protocol was 152, with a mean of 1.4 nodes per patient (range: 0–4). The most common anatomical locations included obturator nodes (40%), internal iliac (31%), external iliac (19%), common iliac (7%), and paraaortic nodes (3%).

Quantitative metrics confirmed high image quality in the 18 h protocol. The mean contrast ratio (C-factor) was 10.30 ± 1.22, slightly higher than for SPECT/CT (10.20 ± 1.30) and the 30-minute protocol (10.02 ± 2.00). The mean signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) was 3.51 ± 1.2 for the 18 h protocol, compared to 4.22 ± 1.1 for SPECT/CT and 4.61 ± 1.1 for the 30-minute protocol, reflecting the lower tracer activity used in the long protocol (15 MBq vs. 37.8 MBq [

17]). Differences in C-factor values between protocols (18 h: 10.30 ± 1.22; SPECT/CT: 10.20 ± 1.30; 30 min: 10.02 ± 2.00) were not statistically significant (p > 0.05, paired t-test).

Differences in C-factor between protocols (18 h: 10.30 ± 1.22; SPECT/CT: 10.20 ± 1.30; 30 min: 10.02 ± 2.00) were not statistically significant (p>0.05, paired t-test), but the 18-h protocol maintained superior clinical efficacy due to higher detection sensitivity and PPV/NPV.

In two cases (1.6%) in the 30-minute protocol, hysterectomy was required before SLN mapping due to signal interference near the cervix, which allowed for successful identification of sentinel lymph nodes in that region.

4. Discussion

This study evaluated the effectiveness of planar scintigraphy performed at different time intervals after administration of Tc-99m (120 MBq) compared to hybrid SPECT/CT for sentinel lymph node (SLN) detection in patients with endometrial cancer (EC). Three approaches were compared: planar scintigraphy performed 30 minutes after injection, hybrid SPECT/CT performed 1hour post-injection, and delayed planar scintigraphy performed 18 hours post-injection (the so-called delayed protocol).

The highest SLN detection sensitivity was achieved with imaging performed 18 hours after injection (94.40%, 118/125), outperforming both SPECT/CT (87.20%, 109/125; OR = 2.48; 95% CI: 0.98–6.27; p = 0.051) and early planar scintigraphy (72.00%, 90/125) (

Table 2,

Figure 3). Bilateral SLN detection with the 18-hour imaging protocol was 80.80% (101/125) compared to 73.60% (92/125) with SPECT/CT (OR = 1.51; 95% CI: 0.83–2.75; p = 0.16), increasing to 88.20% (15/17) in the last 17 consecutive cases, suggesting a learning curve effect.

Among the 152 SLNs detected using the delayed protocol, most were located in obturator (40%), internal iliac (31%), external iliac (19%), common iliac (7%), and para-aortic (3%) regions.

Complete intraoperative and histopathological confirmation (100%) in the 18-hour protocol and high sensitivity in patients with BMI ≥30 (94%, 87/93) confirm its clinical utility, reducing the need for SPECT/CT in most EC cases.

An ideal tracer for SLN mapping should exhibit rapid clearance from the injection site, high retention in SLNs, and minimal uptake in downstream nodes [

21]. Our results are consistent with the SENTI-ENDO trial, which demonstrated 89% SLN detection sensitivity using Tc-99m in EC [

22]. Tc-99m, due to its stability and precise intraoperative localization using a gamma probe, minimizes the risk of false-positive results, as evidenced by 100% intraoperative and histopathological concordance in the 18-hour protocol.

In contrast to studies where SPECT/CT outperforms planar scintigraphy in short protocols (e.g., Kagoshima University, imaging within 1 h [

12]; Navarro et al., short protocol [

13]), our 18-hour planar scintigraphy achieved higher sensitivity (94,40%) due to prolonged tracer accumulation in SLNs. Similarly, Ogawa et al. reported 100% sensitivity and 0% false-negative rate with Tc-99m phytate in cervical cancer [

23], while Ballester et al. noted reduced sensitivity for same-day lymphoscintigraphy with next-day surgery in EC [

24], supporting the importance of extended imaging timing. Togami et al. [

12] and Bats et al. [

7] reported higher false-negative rates with short protocols (23% and 16-h imaging, respectively), underscoring timing’s critical role.

Quantitative metrics such as SNR (3.51 ± 1.2 for 18 h; 4.22 ± 1.1 for SPECT/CT; 4.61 ± 1.1 for 30 min) and C-factor (10.30 ± 1.22 for 18 h; 10.20 ± 1.30 for SPECT/CT; 10.02 ± 2 for 30 min) enabled objective image quality assessment (

Table 2). Although the SNR was lower in the 18-hour protocol—due to lower tracer activity (15 MBq vs. 37.8 MBq [

17])—the higher contrast coefficient (C-factor) indicates better SLN image contrast, supporting the detection effectiveness of this protocol.

Injection site signal interference occurred in only 2 patients (1.6%), requiring hysterectomy before SLN mapping. The minimal background signal in EC—unlike in cervical cancer (CC), where strong cervical uptake hinders imaging [

25,

26,

27]—supports the adequacy of planar scintigraphy in EC. In CC, a meta-analysis by Kraft and Havel showed 90% SPECT/CT sensitivity for SLNs in atypical locations [

28], but in EC, where SLN locations are generally predictable, the benefits of SPECT/CT appear limited, as noted by van der Ploeg et al. [

29].

Our cohort included 74.4% of patients with BMI ≥30 (

Table 1), and the 94% detection sensitivity in this group using the 18-hour protocol exceeds the performance of ICG, where obesity is associated with a higher rate of SLN detection failure [

30]. While SPECT/CT has shown improved accuracy in breast cancer patients with BMI >30 (59% vs. 22% for planar scintigraphy [

31]), the 18-hour protocol in EC achieved comparable results without additional radiation from CT (1–4 mSv [

32]).

The limitations of this study include the fact that intraoperative confirmation of sentinel lymph nodes was available only for patients imaged with the 18-hour protocol, which precludes direct assessment of detection accuracy in the other groups (SPECT/CT and 30-minute planar imaging). Additionally, the small number of cases without SLN detection in the 18-hour group (n=7) prevents reliable evaluation of specificity and negative predictive value (NPV). The wide confidence intervals for odds ratios (e.g., 0.98–6.27 for sensitivity) reflect the limited statistical power and warrant confirmation in larger cohorts.

Future directions include the application of artificial intelligence (AI) in the analysis of scintigraphic images. Deep learning algorithms could automatically segment SLNs, improve detection accuracy in cases with high background signal, optimize Tc-99m dosing based on BMI, and predict signal interference risks, thereby supporting clinical decision-making [

17,

20,

33].

5. Conclusions

The 18-hour planar scintigraphy with Tc-99m (120 MBq) is a highly effective method for SLN detection in early-stage EC, achieving 94.4% sensitivity, 100% PPV/NPV, and 80.8% bilateral detection, improving to 88.2% in the last 17 cases due to a learning curve effect. Its efficacy in patients with BMI ≥30 (94%) and minimal background interference eliminate the routine need for SPECT/CT, reducing radiation exposure and costs. Further multicenter studies and AI integration could standardize and optimize this approach.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, W.S., K.K. and P.B.; methodology W.S,K.K, P.B,R.P, K.R. and J.R,.; software, W.S, K.K, K.P, M.N.; validation P.B,J.R,T.B, E.K, K.R..; formal analysis, W.S, K.K, P.B, K.P, M.N., R.P., T.B., J.R, E.K, K.R.; investigation.W.S, K.K, K.P, P.B. , M.N, E.K and J.R, resources W.S, K.K., P.B, J.R, T.B .; data curation W.S, K.K, R.P, M.N, E.K , K.P, P.B.; writing—original draft preparation W.S, K.K, K.P,.; writing—review and editing W.S, K.P., K.R, K.K. and R.P,.; visualization K.K,E.K.; supervision P.B,J.R, T.B .; project administration W.S, K.K, K.P, P.B.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration 292 of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Maria Skłodowska-Curie National Research Institute of Oncology (NIO-PIB), Krakow Branch, Poland (Approval No. 10/2025, date: 9 January 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

At the start of the treatment, written consent was obtained from all 125 subjects involved in this study for the purpose of retrospective analysis of their medical data.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lu KH, Broaddus RR. Endometrial Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020 , Nov 19;383(21):2053-2064.

- Smith B, Backes F. The role of sentinel lymph nodes in endometrial and cervical cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2015, Dec;112(7):753-60.

- Frati A, Ballester M. Contribution of Lymphoscintigraphy for Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy in Women with Early Stage Endometrial Cancer: Results of the SENTI-ENDO Study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(6):1980-6.

- Mar MV, Miller SA,. Evaluation and localization of lymphatic drainage and sentinel lymph nodes in patients with head and neck melanomas by hybrid SPECT/CT lymphoscintigraphic imaging. J Nucl Med Technol. 2007, Mar;35(1):10-6; quiz 17-20.

- Ballinger JR. Challenges in Preparation of Albumin Nanoparticle-Based Radiopharmaceuticals. Molecules. 2022, Dec 6;27(23):8596.

- Szatkowski W, Słonina D,. The role of technetium-99m isotope in sentinel lymph node identification in gynecological cancers. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother. 2025, Jun 7;30(2):257-268.

- Bats AS, Lavoué V,. Limits of day-before lymphoscintigraphy to localize sentinel nodes in women with cervical cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008 Aug;15(8):2173-9.

- Papadia, A.; Zapardiel, I. Sentinel lymph node mapping in patients with stage I endometrial carcinoma: A focus on bilateral mapping identification by comparing radiotracer Tc99m with blue dye versus indocyanine green fluorescent dye. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 143, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szatkowski W, Pniewska K,. The Assessment of Sentinel Lymph Node Mapping Methods in Endometrial Cancer. J Clin Med. 2025, Jan 21;14(3):676.

- Tew K, Farlow D. SPECT/CT in Melanoma Lymphoscintigraphy. Clin Nucl Med. 2016, Dec;41(12):961-963.

- Even-Sapir E, Lerman H,. Lymphoscintigraphy for sentinel node mapping using a hybrid SPECT/CT system. J Nucl Med. 2003, Sep;44(9):1413-20.

- Togami S, Kawamura T,. Comparison of lymphoscintigraphy and single photon emission computed tomography with computed tomography (SPECT/CT) for sentinel lymph node detection in endometrial cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2020, May;30(5):626-630.

- Navarro AS, Angeles MA. Comparison of SPECT-CT with intraoperative mapping in cervical and uterine malignancies. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2021, May;31(5):679-685.

- Buda A, Elisei F,. Integration of hybrid single-photon emission computed tomography/computed tomography in the preoperative assessment of sentinel node in patients with cervical and endometrial cancer: our experience and literature review. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2012, Jun;22(5):830-5.

- Martínez A, Zerdoud S,. Hybrid imaging by SPECT/CT for sentinel lymph node detection in patients with cancer of the uterine cervix. Gynecol Oncol. 2010, Dec;119(3):431-5.

- Belhocine TZ, Prefontaine M,. Added-value of SPECT/CT to lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymphadenectomy in gynaecological cancers. Am J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2013; 3(2):182-93.

- Szatkowski W, Popieluch J. Numerical Analysis of Sentinel Lymph Node Detection Using Technetium-99m: A Step Toward Objective Scintigraphy Evaluation in Oncology. Bio-Algorithms and Med-Systems. 2025, ;21(1):7-12.

-

Female Genital Tumours. WHO Classification of Tumours, 5th ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 4.

- Buck AK, Nekolla S. SPECT/CT. J Nucl Med. 2008, Aug;49(8):1305-19.

- Bi WL, Hosny A,. Artificial intelligence in cancer imaging: Clinical challenges and applications. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019, Mar;69(2):127-157.

- Li J, Zhuang Z,. Advances and perspectives in nanoprobes for noninvasive lymph node mapping. Nanomedicine (Lond). 2015;10(6):1019-36.

- SENTI-ENDO Trial Group. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in endometrial cancer: A multicenter prospective validation study. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(18):2159–2166.

- Ogawa S, Kobayashi H. Sentinel node detection with (99m)Tc phytate alone is satisfactory for cervical cancer patients undergoing radical hysterectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy. Int J Clin Oncol. 2010, Feb;15(1):52-8.

- Ballester M, Rouzier R. Limits of lymphoscintigraphy for sentinel node biopsy in women with endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2009, Feb;112(2):348-52.

- Frumovitz M, Coleman RL. Usefulness of preoperative lymphoscintigraphy in patients who undergo radical hysterectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy for cervical cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006, Apr;194(4):1186-93.

- Pandit-Taskar N, Gemignani ML. Single photon emission computed tomography SPECT-CT improves sentinel node detection and localization in cervical and uterine malignancy. Gynecol Oncol. 2010, Apr;117(1):59-64.

- Zhang WJ, Zheng R. [Clinical application of sentinel lymph node detection to early stage cervical cancer]. Ai Zheng. 2006, Feb;25(2):224-8.

- Kraft O, Havel M. Detection of Sentinel Lymph Nodes in Gynecologic Tumours by Planar Scintigraphy and SPECT/CT. Mol Imaging Radionucl Ther. 2012, Aug;21(2):47-55.

- van der Ploeg IM, Valdés Olmos RA. The additional value of SPECT/CT in lymphatic mapping in breast cancer and melanoma. J Nucl Med. 2007, Nov;48(11):1756-60.

- Dampali R, Nikolettos K. The Impact of Body Mass Index on Sentinel Lymph Node Identification in Endometrial Cancer. Anticancer Res. 2025, Apr;45(4):1575-1581.

- van der Ploeg IM, Valdés Olmos RA. The impact of body mass index on sentinel lymph node visualization using planar scintigraphy and SPECT/CT. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008, 35(5):780–785.

- Law M, Ma WH. Evaluation of patient effective dose from sentinel lymph node lymphoscintigraphy in breast cancer: a phantom study with SPECT/CT and ICRP-103 recommendations. Eur J Radiol. 2012, May;81(5):e717-20.

- Le TD, Shitiri NC. Image Synthesis in Nuclear Medicine Imaging with Deep Learning: A Review. Sensors (Basel). 2024, Dec 18;24(24):8068.

Table 1.

Patient and Tumor Characteristics 1.

Table 1.

Patient and Tumor Characteristics 1.

| Feature |

Characteristic |

N |

% |

| Age (years) |

Mean ± SD |

67.5 ± 9.7 |

– |

| Histologic Type |

Endometrioid |

109 |

87.20% |

| Serous |

10 |

8.00% |

| |

Clear-Cell |

6 |

4.80% |

| Lymphovascular Space Invasion (LVSI) |

Present |

17 |

13.60% |

| Absent |

108 |

86.40% |

Myometrial Invasion

|

0% |

19 |

15.20% |

| <50% |

74 |

59.20% |

| |

>50% |

32 |

25.60% |

| Lymphadenectomy |

Performed |

22 |

17.60% |

| |

Not Performed |

103 |

82.40% |

| |

|

|

|

| FIGO Stage |

IA |

29 |

23.20% |

| |

IB |

57 |

45.60% |

| |

II |

16 |

12.80% |

| |

IIIA |

4 |

3.20% |

| |

IIIB |

2 |

1.60% |

| |

IIIC1 |

13 |

10.40% |

| |

IIIC2 |

4 |

3.20% |

| FIGO Grade |

G1 |

60 |

48.00% |

| |

G2 |

53 |

42.40% |

| |

G3 |

12 |

9.60% |

| BMI Category |

<25 |

8 |

6.40% |

| |

25–29.9 |

19 |

15.20% |

| |

≥30 |

93 |

74.40% |

| Total |

|

125 |

100.00% |

Table 2.

Effectiveness of Sentinel Lymph Node (SLN) Detection in Endometrial Cancer by Imaging Protocol1.

Table 2.

Effectiveness of Sentinel Lymph Node (SLN) Detection in Endometrial Cancer by Imaging Protocol1.

| Parameter |

30-Minute Planar Scintigraphy |

SPECT/CT |

18-Hour Planar Scintigraphy |

| Overall Detection Rate (%) |

72.00% (90/125)* |

87.20% (109/125)* |

94.40% (118/125) |

| Bilateral Detection Rate (%) |

60.00% (75/125)* |

73.60% (92/125)* |

80.80% (101/125)† |

| |

|

|

| Intraoperative Confirmation (%) |

Not verified* |

Not verified* |

100.00% |

Histopathological Confirmation (%)

|

Not verified* |

Not verified* |

100.00% |

| PPV (%) |

Not verified* |

Not verified* |

100.00% (95% CI: 96.9–100.0) |

| NPV (%) |

Not verified* |

Not verified* |

100.00% (95% CI: 59.0–100.0) |

| SNR (mean ± SD) |

4.61 ± 1.10 |

4.22 ± 1.10 |

3.51 ± 1.20 |

| C-factor (mean ± SD) |

10.02 ± 2.00 |

10.20 ± 1.30 |

10.30 ± 1.22 |

| Sensitivity, BMI ≥30 (%) |

71.00% (66/93)* |

86.00% (80/93)* |

94.00% (87/93) |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).