Submitted:

20 December 2024

Posted:

23 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

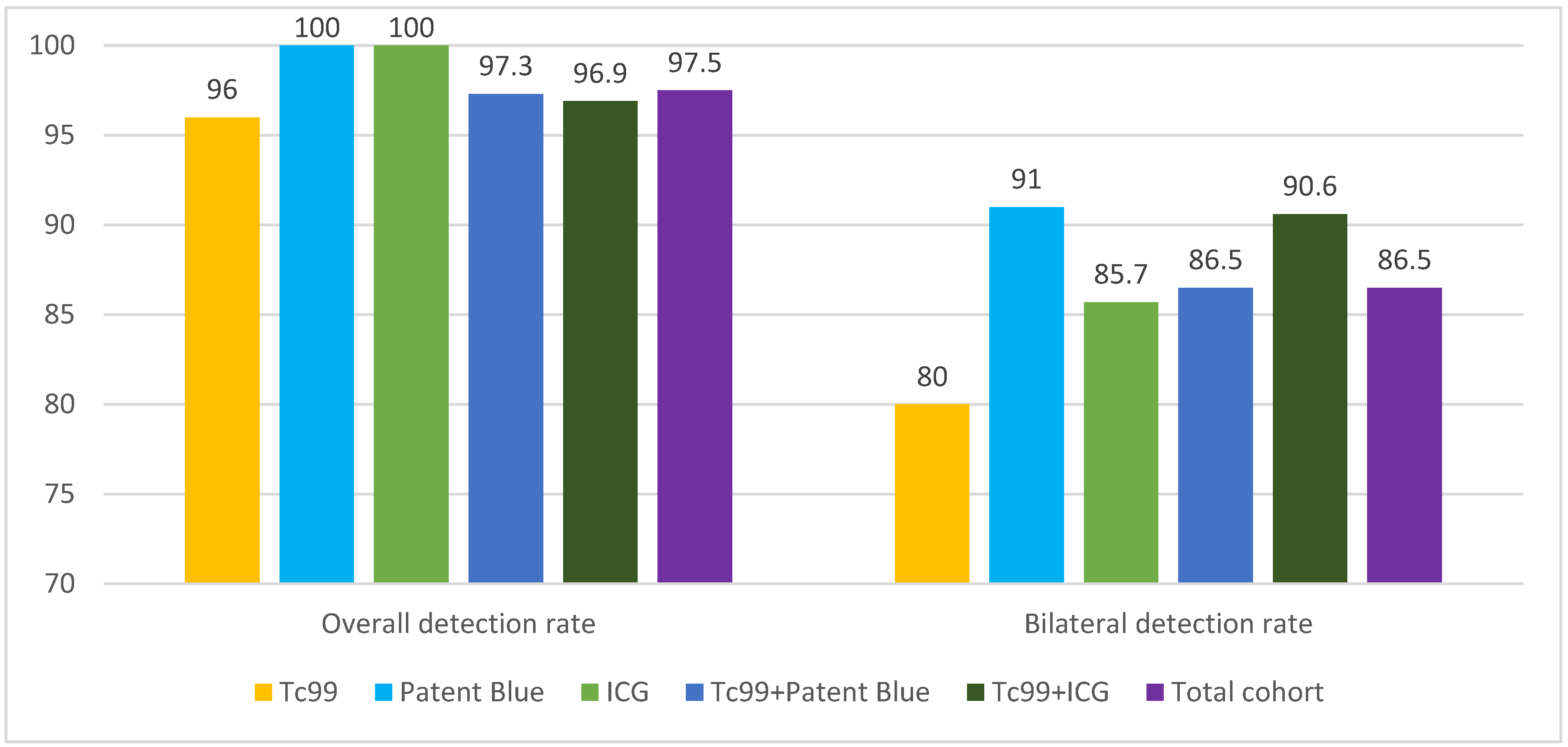

Background/Objectives: Methods: This retrospective cohort study included 119 patients with early-stage EC treated at the Maria Skłodowska-Curie National Research Institute of Oncology between 2016 and 2021. Patients underwent SLNB using technetium-99m (Tc99m), indocyanine green (ICG), Patent Blue, or combinations of these tracers. Detection rates for unilateral and bilateral SLNs and the accuracy of metastasis identification were analyzed. Results: The overall SLN detection rate was 97.5%. Detection rates for individual tracers were 100% for ICG, 100% for Patent Blue, and 96% for Tc99m. Combining tracers achieved detection rates of 96.9% (Tc99m + ICG) and 97.3% (Tc99m + Patent Blue). Bilateral detection was highest with Tc99m + ICG (90.6%) and Patent Blue alone (91%). Metastases were identified in 12% of cases, with combined methods improving metastatic detection. No "empty nodes" were observed with Tc99m, compared to 1.7% with Patent Blue and 0.8% with ICG. Conclusions: While combining Tc99m with dyes did not significantly improve overall detection rates, it enhanced metastasis identification and reduced false-negative results. The findings suggest that combined tracer methods can optimize SLNB accuracy in endometrial cancer. Prospective studies are warranted to validate these results.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- No prior neoadjuvant therapy (chemotherapy or radiotherapy).

- Availability of complete clinical and histopathological data.

- Advanced-stage disease (FIGO stage III-IV).

- Allergic reactions to tracers (ICG, Patent Blue).

- Age below 18 years or above 85 years.

- Comorbidities preventing surgical intervention.

2.3. Sentinel Lymph Node Identification Procedure

2.3.1. Radioactive Tracer Administration (Tc99m):

- Tracer: Technetium-99m-labeled human albumin colloid (NanoColl, GE Healthcare).

- Technique: A dose of 1 mCi (60 MBq) Tc99m was injected into the cervix at the 3 and 9 o’clock positions. Half the dose was administered superficially (2–3 mm) and half deeply (10–15 mm) using thin-walled needles (21G).

- Preoperative Imaging: Static scintigraphy and SPECT-CT imaging were performed at 5 minutes, 60 minutes, and 18 hours after tracer administration, using AnyScan Mediso equipment.

2.3.2. Dye Administration:

- Indocyanine Green (ICG): 0.5 ml (1.250 mg ICG) diluted in 5 ml of water was injected into the cervix at the same locations.

- Patent Blue: 2 ml of dye (1 ml per injection site) was administered.

- Timing: Dyes were injected 15–30 minutes before the start of surgery.

2.3.3. Sentinel Lymph Node Identification:

- Surgical Technique: Sentinel lymph node identification was performed laparoscopically using:

- A gamma probe Gamma Finder 2 Word of medicine to localize Tc99m.

- The VS3 Iridium laparoscopic system (Visionsense 3DHD & IR Fluorescence V) for ICG fluorescence visualization and Patent Blue color channels.

- Anatomical Classification: Retrieved sentinel lymph nodes were anatomically classified as:

- Obturator, external iliac, internal iliac, common iliac, and para-aortic.

- Verification: Each excised sentinel lymph node was double-checked ex vivo using a gamma probe to confirm the presence of Tc99m.

2.4. Histopathological Examination

- Lymph Node Sections: Sections were cut at 2 mm thickness.

- Staining: Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and immunohistochemistry (CK – cytokeratins) were performed.

-

Definitions:

- -

- Macrometastases: Lesions >2 mm.

- -

- Micrometastases: Lesions 0.2–2 mm in diameter.

- -

- Isolated Tumor Cells (ITC): Lesions ≤0.2 mm.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.6. SLN Evaluation Parameters

- Detection Rate (DR): The percentage of patients in whom at least one sentinel lymph node (SLN) was identified.

- Bilateral Detection Rate (BDR): The percentage of patients with SLN detected on both sides.

- Sensitivity: The ratio of true positive results to the number of patients with metastases.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

3.2. Sentinel Lymph Node Detection

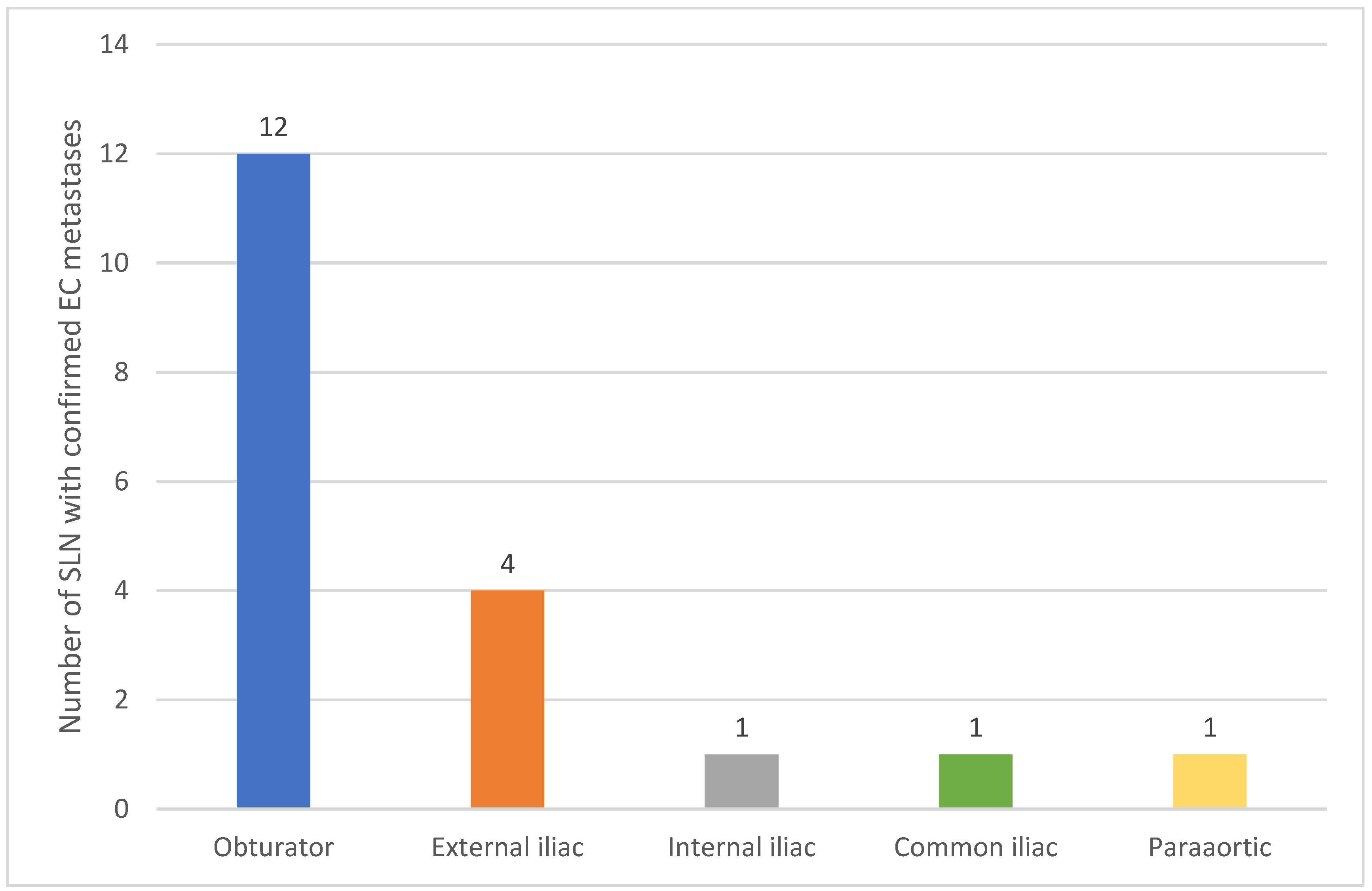

3.3. Metastases and Sample Quality

- 9 were macrometastases,

- 2 were micrometastases,

- 3 were isolated tumor cells.

4. Discussion

4.1. SLN Identification Techniques

4.2. Detection Failures and the Issue of “Empty Nodes”

4.3. Strengths and Limitations of Individual Techniques

4.4. Histopathological Evaluation and Ultrastaging

4.5. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ferlay, J.; Colombet, M. Cancer incidence and mortality patterns in Europe: Estimates for 40 countries and 25 major cancers in 2018. Eur J Cancer. 2018 Nov;103:356-387. [CrossRef]

- Concin, N.; Matias-Guiu, X. ESGO/ESTRO/ESP guidelines for the management of patients with endometrial carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2021 Jan;31(1):12-39. [CrossRef]

- Volpi, L.; Sozzi, G. Long term complications following pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy for endometrial cancer, incidence and potential risk factors: a single institution experience. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2019 Feb;29(2):312-319. [CrossRef]

- Ballester, M.; Dubernard, G. Use of the sentinel node procedure to stage endometrial cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008 May;15(5):1523-9. [CrossRef]

- Delpech, Y.; Cortez, A. The sentinel node concept in endometrial cancer: histopathologic validation by serial section and immunohistochemistry. Ann Oncol. 2007 Nov;18(11):1799-803. [CrossRef]

- Keshtgar, M.R.; Ell, P.J. Sentinel lymph node detection and imaging. Eur J Nucl Med. 1999 Jan;26(1):57-67. [CrossRef]

- Bodurtha Smith, A.J.; Fader, A.N. Sentinel lymph node assessment in endometrial cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017 May;216(5):459-476.e10. [CrossRef]

- Daraï, E.; Dubernard, Gnc. E. Sentinel node biopsy for the management of early stage endometrial cancer: long-term results of the SENTI-ENDO study. Gynecol Oncol. 2015 Jan;136(1):54-9. [CrossRef]

- Sozzi, G.; Fanfani, F. Laparoscopic sentinel node mapping with intracervical indocyanine green injection for endometrial cancer: the SENTIFAIL study - a multicentric analysis of predictors of failed mapping. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2020 Nov;30(11):1713-1718. [CrossRef]

- Tortorella, L.; Casarin, J. Sentinel lymph node biopsy with cervical injection of indocyanine green in apparent early-stage endometrial cancer: predictors of unsuccessful mapping. Gynecol Oncol. 2019 Oct;155(1):34-38. [CrossRef]

- Taşkın, S.; Sarı, M.E. Risk factors for failure of sentinel lymph node mapping using indocyanine green/near-infrared fluorescent imaging in endometrial cancer. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2019 Jun;299(6):1667-1672. [CrossRef]

- Tanner, E.J.; Sinno, A.K. Factors associated with successful bilateral sentinel lymph node mapping in endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2015 Sep;138(3):542-7. [CrossRef]

- Altgassen, C.; Müller, N. Immunohistochemical workup of sentinel nodes in endometrial cancer improves diagnostic accuracy. Gynecol Oncol. 2009 Aug;114(2):284-7. [CrossRef]

- Amant, F.; Mirza, M.R. Cancer of the corpus uteri. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2018 Oct;143 Suppl 2:37-50. [CrossRef]

- Female Genital Tumours, WHO Classification of Tumours, 5th Edition, Volume 4. World Health Organization. 2020.

- Rocha, A.; Domínguez, A.M. Indocyanine green and infrared fluorescence in detection of sentinel lymph nodes in endometrial and cervical cancer staging - a systematic review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016 Nov;206:213-219. [CrossRef]

- Abu-Rustum, N.R. Update on sentinel node mapping in uterine cancer: 10-year experience at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2014 Feb;40(2):327-34. [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Yoo, H.J. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in endometrial cancer: meta-analysis of 26 studies. Gynecol Oncol. 2011 Dec;123(3):522-7. [CrossRef]

- Body, N.; Grégoire, J. Tips and tricks to improve sentinel lymph node mapping with Indocyanin green in endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2018 Aug;150(2):267-273. [CrossRef]

- Geppert, B.; Lönnerfors, C. A study on uterine lymphatic anatomy for standardization of pelvic sentinel lymph node detection in endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2017 May;145(2):256-261. [CrossRef]

- Khoury-Collado, F.; Glaser, G.E. Improving sentinel lymph node detection rates in endometrial cancer: how many cases are needed? Gynecol Oncol. 2009 Dec;115(3):453-5. [CrossRef]

- Holloway, R.W.; Abu-Rustum, N.R. Sentinel lymph node mapping and staging in endometrial cancer: A Society of Gynecologic Oncology literature review with consensus recommendations. Gynecol Oncol. 2017 Aug;146(2):405-415. [CrossRef]

- Holub, Z.; Jabor, A. Laparoscopic detection of sentinel lymph nodes using blue dye in women with cervical and endometrial cancer. Med Sci Monit. 2004 Oct;10(10):CR587-91.

- Smith, B.; Backes, F. The role of sentinel lymph nodes in endometrial and cervical cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2015 Dec;112(7):753-60. [CrossRef]

- Vermeeren, L.; van der Ploeg, I.M. SPECT/CT for preoperative sentinel node localization. J Surg Oncol. 2010 Feb 1;101(2):184-90. [CrossRef]

- Keidar, Z.; Israel, O. SPECT/CT in tumor imaging: technical aspects and clinical applications. Semin Nucl Med. 2003 Jul;33(3):205-18. [CrossRef]

- Papadia, A.; Zapardiel, I. Sentinel lymph node mapping in patients with stage I endometrial carcinoma: a focus on bilateral mapping identification by comparing radiotracer Tc99m with blue dye versus indocyanine green fluorescent dye. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2017 Mar;143(3):475-480. [CrossRef]

- Ballester, M.; Dubernard, G. Detection rate and diagnostic accuracy of sentinel-node biopsy in early stage endometrial cancer: a prospective multicentre study (SENTI-ENDO). Lancet Oncol. 2011 May;12(5):469-76. [CrossRef]

- Rossi, E.C., Kowalski, L.D. A comparison of sentinel lymph node biopsy to lymphadenectomy for endometrial cancer staging (FIRES trial): a multicentre, prospective, cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2017 Mar;18(3):384-392. [CrossRef]

- Kessous, R.; How, J. Triple tracer (blue dye, indocyanine green, and Tc99) compared to double tracer (indocyanine green and Tc99) for sentinel lymph node detection in endometrial cancer: a prospective study with random assignment. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2019 Sep;29(7):1121-1125. [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, S.; Bebia, V. Technetium-99m-indocyanine green versus technetium-99m-methylene blue for sentinel lymph node biopsy in early-stage endometrial cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2020 Mar;30(3):311-317. [CrossRef]

- How, J.; Gotlieb, W.H. Comparing indocyanine green, technetium, and blue dye for sentinel lymph node mapping in endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2015 Jun;137(3):436-42. [CrossRef]

| Feature | Characteristic | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Histologic Type | Endometrioid | 113 | 95.0% |

| Serous | 3 | 2.5% | |

| Clear Cell | 3 | 2.5% | |

| Lymphovascular Space Invasion (LVSI) | Present | 12 | 10.0% |

| Absent | 107 | 90.0% | |

| Myometrial Invasion | 0% | 10 | 8.4% |

| <50% | 66 | 55.5% | |

| >50% | 43 | 36.1% | |

| Lymphadenectomy | Bilateral Pelvic | 20 | 16.8% |

| Paraaortic | 7 | 5.9% | |

| FIGO Stage | IA | 11 | 9.2% |

| IB | 56 | 47.1% | |

| II | 31 | 26.1% | |

| IIIA | 3 | 2.5% | |

| IIIB | 2 | 1.7% | |

| IIIC1 | 12 | 10.1% | |

| IIIC2 | 4 | 3.3% | |

| FIGO Grade | G1 | 59 | 49.6% |

| G2 | 52 | 43.7% | |

| G3 | 8 | 6.7% | |

| Total | 119 | 100.0% |

| Parameter | Tc99m (N=25) | Blue Dye (N=11) | ICG2 (N=14) | Tc99m + Blue Dye (N=37) | Tc99m + ICG2 (N=32) | Total Cohort (N=119) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Detection Rate |

24 (96.0%) | 11 (100.0%) | 14 (100.0%) | 36 (97.3%) | 31 (96.9%) | 116 (97.5%) | 0.921 |

| Bilateral Detection Rate |

20 (80.0%) | 10 (91.0%) | 12 (85.7%) | 32 (86.5%) | 29 (90.6%) | 103 (86.5%) | 0.815 |

| Confirmed Metastases |

5 (25.0%) | 1 (9.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 6 (16.2%) | 2 (6.3%) | 14 (11.8%) | 0.266 |

| Lymph Node Location | Unilateral Metastases (N=8) | Bilateral Metastases (N=5) | Isolated Metastasis (N=1) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obturator | 5 | 7 | 0 | ||||

| External Iliac | 2 | 2 | 0 | ||||

| Internal Iliac | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Common Iliac | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||||

| Paraaortic | 0 | 0 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).