1. Introduction

The increasing complexity of smart home and smart building systems necessitates the development of multidisciplinary competencies among engineers, extending beyond technical proficiency to encompass creativity, problem-solving, and a heightened sensitivity to user needs. In the contemporary engineering domain, engineers are tasked with the responsibility of formulating solutions that not only address technological challenges but also enhance the comfort, safety, energy efficiency, and accessibility of living and working environments for diverse user groups, including the elderly, remote workers, and individuals with specific functional needs [

1,

2]. This paradigm shift in engineering education is indicative of a more extensive transformation occurring within technical professions, wherein the ability to incorporate human-centered considerations into design processes is deemed to be as imperative as technical expertise. In this context, Design Thinking (DT) has gained prominence as a pedagogical approach that fosters empathy, creativity, and iterative problem-solving. Engaging students in stages such as Empathize and Define facilitates the translation of user experiences into functional design solutions, thereby helping engineers balance technical feasibility with user-oriented functionality [

3,

4,

5]. However, it should be highlighted that higher education, in particular engineering, also involves innovative methods and tools. The objective of these educational initiatives is twofold: firstly, to encourage students to adopt a proactive and creative approach to their studies; and secondly, to equip them with the necessary skills to thrive in the contemporary engineering sector, which is characterized by fierce competition and rapid technological advancement.

1.1. Simulation Tools in Engineering Education

Simulation-based learning has emerged as a key component of modern engineering education, providing a safe, cost-effective, and scalable environment for bridging the gap between theoretical knowledge and applied practice. In the realm of available platforms, Cisco Packet Tracer has achieved widespread adoption, primarily due to its proficiency in modelling intricate Internet of Things (IoT) networks and smart home or smart building configurations. The applications of this software are extensive, ranging from the simulation of connected home solutions to the design of comprehensive Smart Campus infrastructures. It enables students to configure, test and optimize interconnected systems [

6,

7,

8]. Empirical studies have indicated that such simulations enhance conceptual understanding, problem-solving and creative thinking, particularly in courses requiring the integration of diverse technological components within fieldbus level as well as information and communication technology (ICT) networks with IoT concept [

9].

Beyond supporting classroom instruction, the value of simulation environments in preparing students for the realities of professional engineering practice is increasingly recognized. By replicating the workflows, constraints, and decision-making contexts encountered in real-world projects, platforms such as Cisco Packet Tracer enable students to gain practical experience with IoT and other smart devices management, network integration, and system-level problem-solving in a risk-free virtual setting [

10]. The potential of such environments is further extended by advanced simulation tools, including the Smart Living Environment tools, which model complex user interactions, optimize sensor networks, and support assisted living solutions for older adults [

1]. In this context, simulation tools have emerged as a pedagogical instrument that serves as a conduit between conceptual learning and industry-relevant competencies. These tools are designed to equip future engineers with the technical fluency and adaptability that are essential in dynamic, technology-driven sectors.

1.2. Blended Learning in Higher Engineering Education

Concurrent with these technological and conceptual advancements, blended learning (BL) has become an essential component of higher engineering education. This pedagogical model integrates face-to-face instruction with asynchronous online collaboration, enhancing flexibility and enabling students to engage in meaningful project-based learning regardless of time and location constraints. The efficacy of blended frameworks is especially pronounced when employed in conjunction with collaborative digital platforms, such as Padlet, which facilitates brainstorming and multimedia-based project submissions, thereby promoting transparency and continuous peer feedback [

11,

12,

13]. The integration of BL in technical curricula has been identified as a response to the growing imperative for active, student-centered approaches that facilitate self-directed exploration, peer collaboration, and the iterative refinement of project outcomes. As stated in recent systematic reviews, such models have been shown to significantly improve engagement, digital literacy, and the development of collaborative competencies. These skills are critical for engineers working in globally distributed and interdisciplinary teams [

10,

14,

15,

16]. Moreover, research highlights that integrating these approaches with flipped classroom (FC) strategies and interactive project work enhances student motivation, fosters autonomous learning, and strengthens both technical and interpersonal skills that are crucial for professional practice [

12,

17,

18,

19].

Additionally, BL serves as a pedagogical bridge between academic training and the realities of modern engineering practice, where hybrid collaboration—integrating on-site and remote teamwork—has become the norm. By emulating the workflows and communication structures found in smart campuses and technology-driven enterprises, blended approaches equip students with the necessary skills to thrive in multidisciplinary, digitally mediated, and context-aware project environments [

6]. The alignment of educational methodologies with labor market demands positions BL as a crucial strategy for fostering workforce-ready graduates who are capable of navigating the complexities of the smart technology sector.

1.3. Aim and Contribution of the Study

Despite the growing interest in innovative pedagogical methods, comprehensive approaches that integrate DT, computer-assisted simulation-based problem-solving, and hybrid collaboration in engineering education remain rare. Existing studies have largely focused on these components in isolation, overlooking the potential synergistic impact on student learning outcomes. The present study introduces the initial implementation of a blended, DT–oriented laboratory framework for a master's-level Smart Building Systems course, with the aim of addressing this gap. This framework integrates simulation-based design activities using Cisco Packet Tracer, collaborative tools that facilitate hybrid teamwork, and a computer-assisted human-centered project methodology to enhance both technical and soft skills among students.

The original contribution of this study lies in its integrated pedagogical design, which enables the simultaneous development of technical competencies – such as IoT system modelling and smart space conceptualization – and higher-order skills, including creativity, empathy, and interdisciplinary collaboration. To the author's knowledge, this constitutes the new educational deployment of such a comprehensive model at the host institution, specifically tailored for master's students focusing on smart home and smart building systems. Furthermore, this study presents the author’s approach as an analysis of a selected case study, providing in-depth insights into the design, implementation, and evaluation of this educational model. It is positioned within the broader context of a shifting paradigm in higher technical education, which increasingly embraces blended, student-centered, and competency-oriented approaches to better prepare graduates for complex, technology-driven professional environments. Beyond the consideration of individual tools or methodologies, this approach emphasizes DT as a mechanism for embedding user perspectives into technical solutions, simulation as a bridge between conceptual and applied learning, and blended collaboration as preparation for the hybridized professional environments of the modern engineering sector.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 reviews related work on DT, simulation tools, and BL in engineering education.

Section 3 describes the methodology, including the course context, project framework, and applied tools.

Section 4 presents the results of student projects and survey-based evaluation.

Section 5 discusses these findings in the context of current literature and educational practice.

Section 6 concludes the paper, highlighting key implications and outlining directions for future work.

2. Materials – Related Work

Recent research in the field of engineering education has increasingly explored the intersection of human-centered design, simulation-based learning, and hybrid collaboration. These approaches, which were originally developed in parallel, have now converged to reshape the way in which smart home and smart building systems are taught. As demonstrated in the relevant literature, there has been a shift from isolated applications towards integrated, interdisciplinary frameworks. The following subsections provide an overview of significant advancements in DT, simulation tools, and BL with FC strategies.

2.1. Design Thinking in Engineering Education

In order to prepare engineers for contemporary socio-technical challenges, it is necessary to employ pedagogical frameworks that foster creativity, empathy and interdisciplinary collaboration. Among these, DT has emerged as a particularly influential approach. As Munoz et al. emphasize, the DT approach equips students with the ability to manage ill-structured problems by co-creating solutions with relevant stakeholders [

20]. This conclusion is consistent with the cross-institutional work by McLaughlin et al., which documents how DT fosters collaborative, user-focused problem-solving across four universities [

4]. DT is valued for its process-oriented and iterative nature, which encourages students to navigate uncertainty through cycles of problem definition, ideation, prototyping, and testing [

3]. Beyond enhancing creativity and empathy, DT has been shown to have a positive impact on students' ability to navigate uncertainty through cycles of problem definition, ideation, prototyping, and testing. Research highlights its role in developing creativity, empathy, critical thinking, and rapid prototyping, preparing students to integrate technical feasibility with user needs and engage diverse stakeholders [

20,

21]. A key development in recent applications is the shift from conceptual treatments toward context-specific implementations, embedding DT directly within curricula focused on smart suilding and IoT. In this form, DT serves both as a mindset and a structured pedagogical framework, enabling students to address complex design challenges that require technical proficiency and socio-technical sensitivity [

3,

5].

2.2. Simulation Tools in Smart Building and IoT Education

To bridge the gap between theory and practice, educators increasingly adopt virtual environments in which students can experiment with complex systems, with simulation tools playing a central role. Alfarsi et al. show how Cisco Packet Tracer IoT modules facilitate the design and control of safe home prototypes, demonstrating effective monitoring and control of smart objects in simulated networks [

8]. Building on this, Kumar et al. extend the approach to smart campus ecosystems by modeling solar-powered grids, RFID-enabled access, and IoT-based environmental controls in Packet Tracer 8.2 [

6], marking a shift from single-domain smart homes to multi-layered smart sampus systems. Such platforms facilitate iterative design, enabling rapid prototyping and repeated testing before physical implementation, thereby fostering resilience and adaptive problem-solving in interdisciplinary projects where technical, operational, and user requirements intersect [

22]. Mishra et al. enhance Packet Tracer’s educational value through the use of programmable controllers and scenario-based exercises [

23], while Barriga et al. propose domain-specific simulation languages such as SimulateIoT for automated code generation and more sophisticated experimentation [

24]. Extensions integrating simulation with machine learning further optimize IoT sensor networks for adaptive, energy-efficient smart spaces, broadening the educational context to AI-driven applications [

25].

Furthermore, simulation has evolved from a solitary learning tool into a collaborative design space. Sellberg et al. highlight how virtual labs support interactive, co-constructed learning [

10], a view echoed by Mwansa et al., who emphasize Packet Tracer’s value for teamwork even in resource-constrained settings [

26]. Collectively, the evidence from these studies demonstrate that simulation has matured from a cost-effective hardware substitute into a platform for interdisciplinary collaboration, creative experimentation, and the development of future-ready digital competencies.

2.3. Blended Learning and Hybrid Collaboration in Engineering Education

In response to the need for instructional models reflecting distributed workflows of modern engineering, universities are adopting ecosystems that combine face-to-face and digital collaboration, with BL being a key enabler in this process. In [

13], BL is framed as a strategic innovation rather than a contingency measure and this view is supported by Limaymanta et al. [

27], who show that BL and especially FC enhances higher order thinking in technical disciplines. Gutiérrez-Braojos et al. highlight the role of collaborative digital tools like Padlet as “learning hubs” for peer feedback and transparent project management. This viewpoint is in alignment with Andrews et al. [

28], who propose hybrid models for technical communication education that enchance teamwork and cross-disciplinary communication. These environments foster mutual accountability and distributed responsibility, preparing students for collaborative practices in modern engineering.

Integrating BL with simulation-based virtual labs further amplifies its impact, enabling experiential and project-based learning even in resource-constrained environments [

26]. Such integrations are particularly valuable in IoT-focused programs, where simulated infrastructures create authentic contexts for collaborative problem-solving [

10]. Bibliometric reviews indicate that multimedia-enhanced BL models, including video-based feedback tools like Loom, improve learner autonomy and iterative skill development [

9].

Overall, BL approaches contribute to developing soft skills—communication, adaptability, and cultural competence—critical for global, interdisciplinary teamwork, especially in international smart building projects [

28]. This evolution reflects a shift from flexible delivery toward collaborative, project-based experiences within hybrid ecosystems that integrate simulation, collaborative platforms, and multimedia communication, aligning academic training with the realities of digitally mediated engineering projects.

2.4. Synthesis of Trends and Research Implications

This synthetic literature review reveals a paradigm shift in engineering education for smart home and smart building contexts. DT has evolved from conceptual frameworks to structured, context-specific applications, equipping students with creative, empathic and interdisciplinary competencies. Simulation environments, which were previously considered low-cost alternatives to laboratory settings, have evolved into collaborative design spaces where complex IoT ecosystems can be modelled and iteratively refined. The evolution of blended and hybrid learning has transcended the concept of flexible delivery, actively shaping the social and collaborative dynamics of technical education in accordance with digitally mediated engineering workflows.

While the educational value of each of these approaches – DT, simulation, and BL – has been demonstrated, the potential benefits of their combined application remain largely unexplored. This study proposes a novel framework that integrates human-centered design, simulation-based problem-solving, and hybrid teamwork to enhance both technical and soft skills. The model is consistent with the growing emphasis on holistic, practice-oriented education, the aim of which is to prepare engineers for the socio-technical challenges of smart environments.

3. Methodology

The methodological framework adopted in this study integrates BL, DT, and simulation-driven project work to enhance technical, creative, and collaborative competencies in Smart Building Systems education. This section delineates the course context, the blended and project-based learning approach, the integration of the DT process, the tools and deliverables, and the evaluation strategy.

3.1. Course Context

The case study was conducted within the "Smart Building Systems" laboratory course for first semester master’s students in Industrial and Building Automation at AGH University of Krakow (AGH). A total of 18 students participated in the study, working in teams of three or four members. The course combines technical training in building automation with creative, interdisciplinary design tasks. In the initial phase, students completed practical exercises using laboratory stations equipped with open-standard automation technologies, including KNX and LonWorks—widely used in industry for distributed control networks [

26,

29,

30]. These sessions aimed to develop understanding of decentralized building automation system architecture, particularly at the fieldbus level, and to build configuration skills in real automation environments. This practical foundation proved essential for the subsequent application-oriented project, aligning with literature that emphasizes integrating theoretical learning with practice-oriented tasks in engineering education [

10,

26].

The project-based component, introduced in the final four weeks, focused on selecting smart automation functions and simulating their operation within an IoT-oriented architecture. Students worked collaboratively for approximately three and a half weeks to develop and submit their solutions. As discussed in

Section 1 and

Section 2, the project’s main goals were to foster teamwork, promote self-organization, and encourage the use of collaborative tools relevant to modern engineering practice [

4,

28]. Integrating soft-skill development with technical simulation and system modeling was a central aim, providing students with a comprehensive understanding of the interdisciplinary challenges in the smart building sector.

3.2. Blended Learning Framework

The course adopted BL model combining online and on-site elements, consistent with AGH University’s hybrid teaching practices. Before starting the project, students attended a synchronous online lecture in the FC format. This lecture introduced the DT methodology and its application to smart building projects. Supplementary DT materials were provided via Moodle platform, allowing self-paced review and exploration of practical examples [

17,

27]. An on-site laboratory meeting followed, presenting the project framework, team tasks, tool selection, implementation options, and assessment criteria.

Project development was supported primarily through online consultations, using Padlet as a collaborative platform for asynchronous communication, idea exchange, and DT process documentation. In-person consultations were available upon request, providing flexible access to instructors and technical support. Integrating collaborative digital tools within the BL structure reflects current trends in enhancing transparency, feedback, and distributed teamwork in engineering education [

13]. This blended approach replicated the hybrid workflows of modern engineering, fostering self-directed learning, team collaboration, and sustained project engagement.

3.3. Project Framework

The project component aimed to translate theoretical knowledge from initial laboratory sessions into practical, human-centered solutions for smart home and smart building contexts. Built on experiences with open automation standards like KNX and LonWorks (see

Section 3.1), it engaged students in multidisciplinary team projects integrating user-oriented design with IoT-based system simulation. Project themes and team compositions were predetermined to balance tasks and competencies, with five themes reflecting distinct user profiles and living scenarios: Smart Office & Chill, Senior's Bedroom, Gamer's Room 2.0, Comfortable Living Room for a Senior, and Smart Living Room. These themes encouraged translating user needs into functional specifications, aligning with the DT methodology [

3,

4]. Teams were asked to document their work through the Empathize → Define → Ideate → Prototype → Test stages on Padlet, which functioned as a collaborative workspace for brainstorming, feedback exchange, and project submission, supporting transparency and distributed project management [

13,

28].

After these conceptual phases, students developed functional models and simulations using Cisco Packet Tracer to create virtual prototypes, configure automation scenarios, and test interactions within a simulated IoT ecosystem [

6,

8]. Before this, Sweet Home 3D or Floorplanner was used to design spatial layouts and plan device placement, contextualizing solutions within realistic environments. By emulating automation functions in a risk-free digital setting, students explored configurations and iteratively refined their solutions, reflecting professional engineering workflows [

22]. This structure fostered both technical competence and essential soft skills, including teamwork, self-organization, and effective use of digital collaboration tools in hybrid environments.

Table 1 summarizes the project stages, tools, and expected learning outcomes.

3.4. Tools and Deliverables

As previously outlined, the project integrated simulation, collaboration, and presentation tools to support educational goals and reflect smart building industry practices. In the preliminary phase, students used Sweet Home 3D or Floorplanner to create room layouts and determine device placement, followed by functional modelling in Cisco Packet Tracer. This transition allowed teams to contextualize design decisions and embed technical solutions in realistic living spaces.

Cisco Packet Tracer served as the core simulation platform, enabling students to prototype interconnected devices, configure automation scenarios, and iteratively refine solutions within a risk-free smart building ecosystem. Its dedicated modules for smart home and building applications, along with the ability to integrate open IoT technologies, broadened its relevance for modern automation projects.

Padlet functioned as a collaborative digital workspace for asynchronous teamwork, feedback exchange, and project tracking, supporting all stages of the DT process. Project outcomes were disseminated through concise video tutorials (e.g., Loom) and simplified technical documentation using MS Word, OpenOffice, or LaTeX Overleaf, summarizing system architecture, functionalities, and user-focused features.

Students were initially informed about alternative collaboration, documentation, and simulation tools and could propose their own. However, all teams opted for the recommended set of tools—Sweet Home 3D, Floorplanner, Packet Tracer, Padlet, and Loom—due to their usability, alignment with project objectives, and available instructional support.

Table 2 summarizes these tools, their purposes, and educational value.

3.5. Design Thinking Integration

The organization of the project is founded on the DT methodology, which ensures a clear, user-centered workflow for developing smart building solutions. The process was executed in accordance with the five classic stages of DT. The three preliminary stages (Empathize, Define, Ideate) were executed within the Padlet platform, serving as a collaborative space for analysis, brainstorming, and conceptual design. The subsequent two stages (Prototype, Test) were conducted in the Sweet Home 3D and the Cisco Packet Tracer environments, where spatial layouts and functional models of smart building systems were developed and demonstrated.

Table 3 presents overview of these stages, along with the key activities performed by students and the resulting project outputs.

3.6. Evaluation Rules and Final Remarks

The project evaluation combined formal assessment of student deliverables with survey-based feedback to capture both learning outcomes and perceptions of the methodology. Instructor assessment focused on functional simulation models, instructional video tutorials, and technical documentation, with grading criteria including technical accuracy, implementation of smart building functions, creativity, and alignment with user-centered design principles. This ensured that final grades reflected both solution quality and practical application of DT.

Anonymous post-project surveys were utilized to gather student feedback, employing closed-ended questions to assess the perceived usefulness of tools (e.g., Padlet, Cisco Packet Tracer, Loom), clarity of objectives, and the effectiveness of the BL approach. In addition, open-ended questions were included to solicit valuable aspects, challenges, and suggestions for course improvement.

The methodology provided a structured framework for guiding students through a user-centered, simulation-driven design process within a BL environment. This framework combined practical system modelling with collaborative documentation, fostering both the technical and soft skills needed for interdisciplinary smart building projects.

This study did not involve research requiring formal ethical approval. Participation in the survey was voluntary, and all responses were collected anonymously to ensure data confidentiality. During the preparation of this manuscript, the author used ChatGPT (OpenAI, GPT-4.1) to support brainstorming project themes and synthesizing literature. All generated content was critically reviewed and edited by the author, who takes full responsibility for the final version of the manuscript.

4. Results

The implementation of the BL and DT–oriented laboratory framework resulted in a diverse set of student projects, reflecting different levels of engagement, collaboration, and technical depth. For the purposes of this case study, three out of five team projects were selected for detailed analysis, representing varied approaches to user-centered design and levels of advancement. This section presents the outcomes of these projects, highlighting both the process-related artifacts and the developed simulations.

4.1. Student Project Outcomes

The results of the student work are presented in two dimensions: the conceptual artifacts developed during the DT process and the technical prototypes created in Cisco Packet Tracer, complemented by supporting documentation and video tutorials.

4.1.1. Insights from Design Thinking Discussions

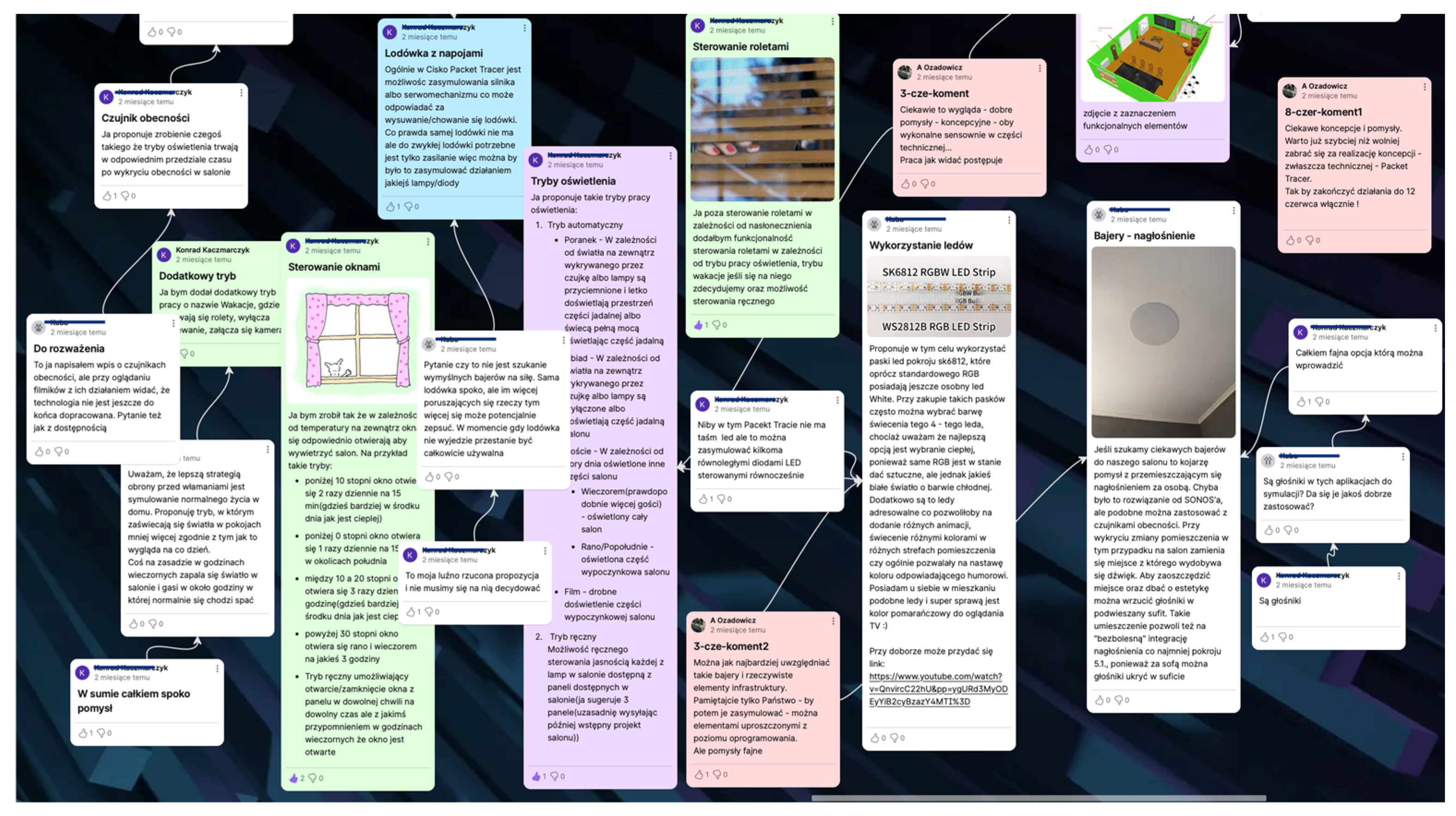

An analysis of Padlet boards created by student teams reveals significant variation in the application of the DT approach, with differences in the depth of exploration, organization of ideas, and linkage to technical implementations.

The objective of the Senior's Bedroom project (Group A) was to establish a secure and user-friendly environment for elderly individuals, with a particular focus on enhancing nighttime mobility and ease of device operation. However, the group's DT process demonstrates a paucity of early-stage exploration. The Empathize stage of the Padlet board contained only a limited number of concise entries, predominantly characterizing fundamental user requirements without implementing systematic approaches such as the "5 x why" method. In a similar manner, the Define stage was reduced to just two concise notes, identifying key challenges such as the need for simplified lighting controls and the integration of emergency assistance functions. This restricted discourse is manifest in the initial segment of the Padlet board, as illustrated in

Figure 1, which presents solely single-level statements concerning user requirements.

During the Ideation stage, the team proposed several solutions; however, many of these were directly derived from the instructor's preliminary guidelines, including automatic floor-level night lighting, voice-based control for lighting and appliances, and an emergency alert mechanism integrated with motion detection. Despite the absence of extensive brainstorming, the group demonstrated an effective structuring of their subsequent notes, directly associating proposed functions with their implementation plans in Cisco Packet Tracer. This transition towards the implementation of practical solutions is evident in the subsequent Padlet entries, as illustrated in

Figure 2. In these entries, students refer to particular prototypes that have been developed within the simulation environment. They also refer to their supplementary 3D room layout and technical documentation. Notes inscribed with a pink background for all the figures are to be regarded as consultative comments issued by the instructor.

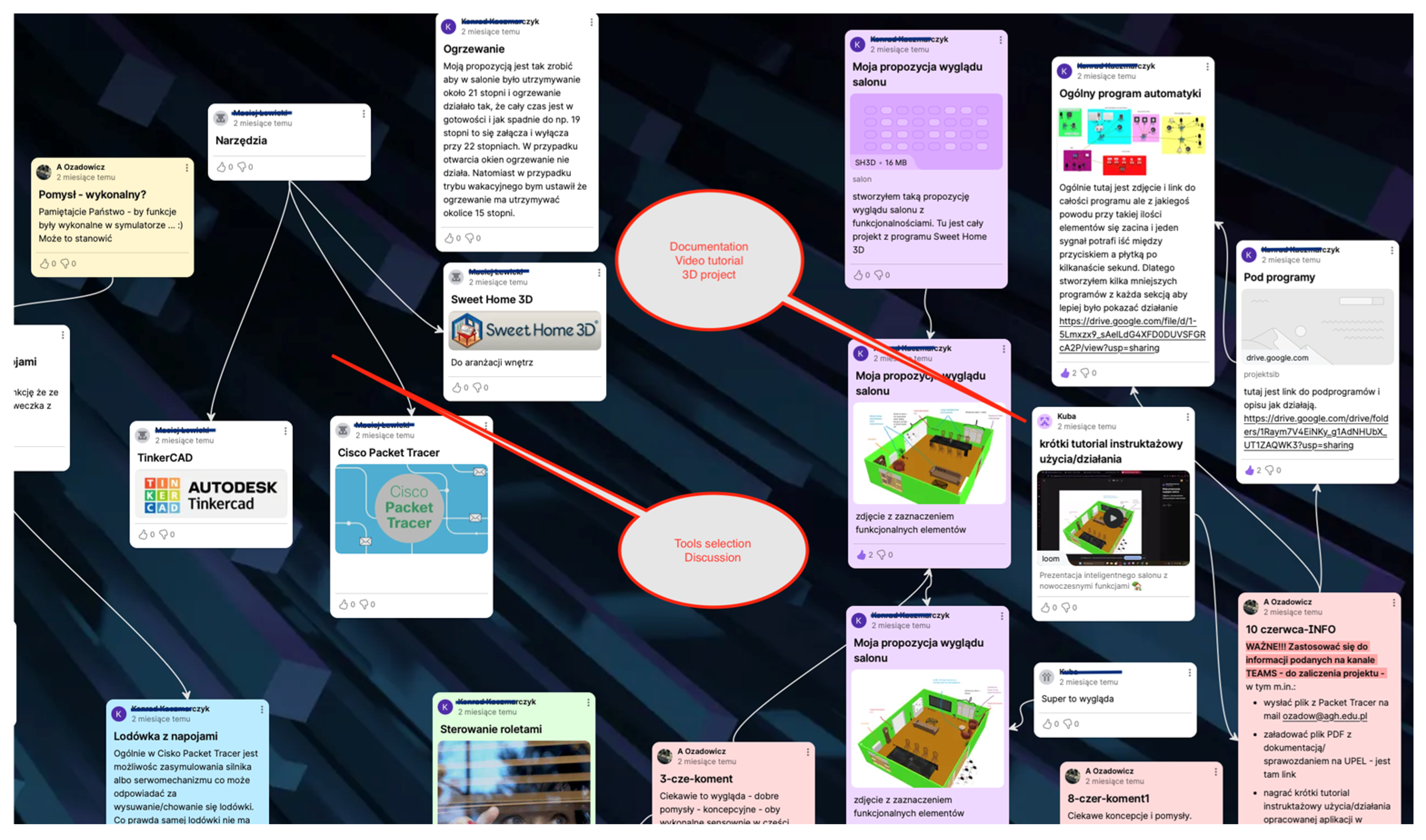

The Gamer's Room 2.0 project (Group B) exhibited a considerably more sophisticated DT process, with discernible advancement evident at every stage. The team's Padlet board comprised a substantial number of notes, reflecting multi-step discussions and clear links between ideas. The evolution of concepts was particularly evident, as initial user needs identified in the Empathize and Define stages were gradually expanded into more detailed solutions during Ideation. This progression is illustrated in

Figure 3, where the Padlet entries demonstrate the evolution of initial concepts—such as lighting personalization and air quality control—into structured plans for integrating multi-zone RGB lighting and adaptive ventilation tailored to gaming sessions.

The group also produced several technically oriented notes detailing the implementation of functions in Cisco Packet Tracer, including automation logic for power-saving routines and the synchronization of lighting with gaming hardware. Their work demonstrated an iterative evolution of the approach to simulating control and monitoring functions, gradually refining the implemented logic to better reflect realistic user scenarios and system responses. As demonstrated in

Figure 4, this progression is evident in the updated simulation models, which are closely aligned with the technical documentation.

The team also incorporated precise references to their supporting documentation and video tutorial, ensuring that the narrative of their design process was complete and accessible. It is noteworthy that the notes on the board reflect active participation from all team members, thus contributing to a dynamic ideation process and resulting in a technically rich and well-justified final solution.

The Smart Living Room project (Group C) produced one of the most comprehensive DT boards among all teams, characterized by a very high number of notes while maintaining clarity through consistent color-coding and categorization. This structure enabled a systematic presentation of ideas and facilitated the identification of connections between different stages of the process. As illustrated in

Figure 5, the team employed a multifaceted approach in the initial Empathize and Define stages, incorporating components of the "5 x why" method to investigate the underlying issues that underpin user needs, such as multi-user personalization and intuitive control interfaces.

A significant strength of this group's work was the evident progression from the identification of problems to the development of original, context-specific solutions. While the instructor's initial guidelines served as a point of departure, the team significantly expanded on them, proposing custom automation profiles for different household members, adaptive scene-based lighting and multimedia modes, and integrated air quality management systems. Furthermore, several notes explored the concept of smart spatial arrangements, proposing detailed device placement in the living area, which complemented their technical documentation. As illustrated in

Figure 6, this phase of the project involved the direct correlation between the proposed layout of devices and the developed prototypes and simulation models. The board also included explicit references to supporting documentation and the video tutorial, ensuring coherence between their conceptual and prototyping stages.

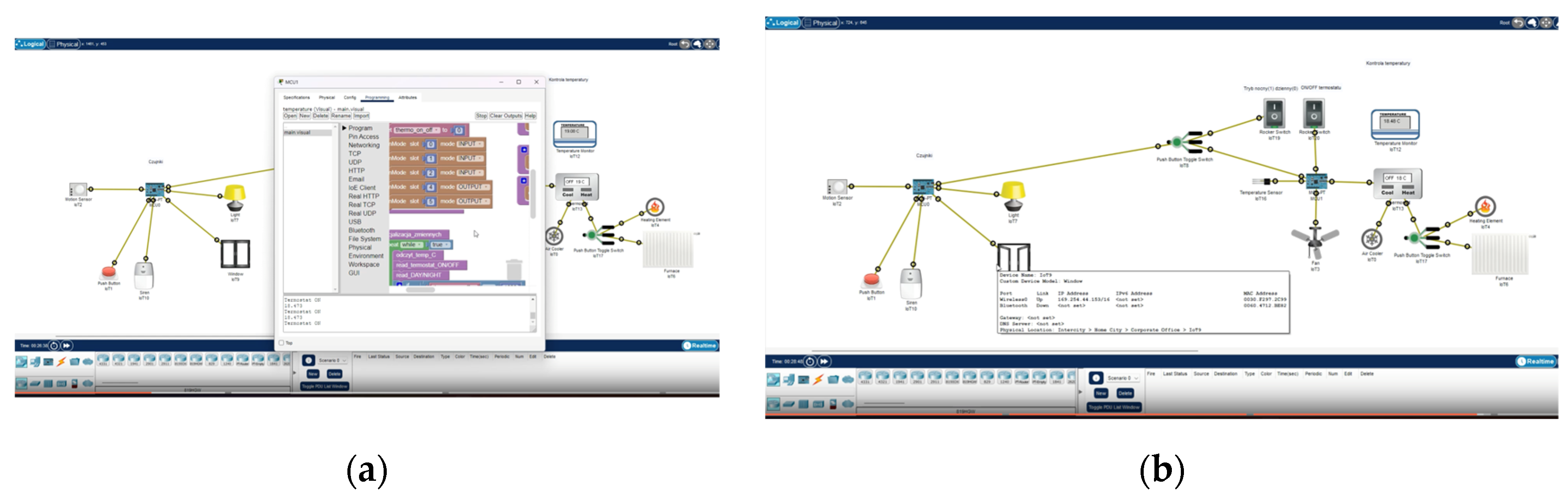

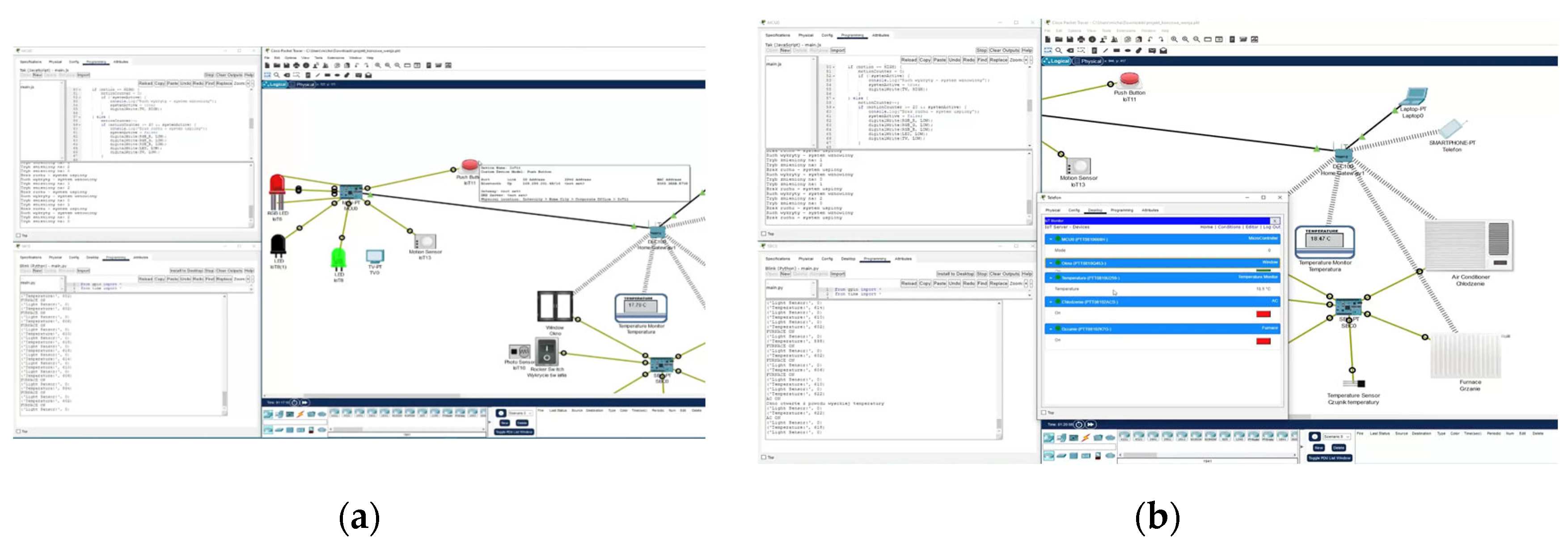

4.1.2. Prototyping in Cisco Packet Tracer and Supporting Documentation

The second phase of the project involved the development of functional prototypes using Cisco Packet Tracer and Sweet Home 3D / Floorplanner, complemented by concise technical documentation and video tutorials. This combination of tools enabled students to design both the logical system behavior and the spatial arrangements of devices, thereby ensuring that conceptual ideas from the DT process were transformed into working simulation models with programmed automation logic and visualized room layouts.

The Senior's Bedroom project implemented a two-mode automation system designed for elderly users. The day mode functioned to maintain conditions that were deemed appropriate for daily activities, with periodic presence checks being conducted. In contrast, the night mode adjusted settings for the purpose of ensuring safe rest, incorporating motion-triggered lighting. Furthermore, an alert mechanism was incorporated to notify caregivers in the event of prolonged inactivity. The video tutorial presented by the group evidently demonstrated the programming of microcontrollers and the configuration of automation logic, while the accompanying documentation thoroughly detailed the core functionalities and device placement. The outputs are combined in

Figure 7, which shows selected screenshots from the video tutorial.

The Gamer's Room 2.0 prototype incorporated automated lighting scenarios customized to the user's activities, encompassing a gaming mode with dynamic RGB effects, a streaming mode with balanced facial illumination and background neutralization, and a night gaming mode with dimmed lighting for eye comfort. The system also incorporated temperature-responsive cooling, energy-saving functions that powered down equipment during inactivity, automated blind control, and centralized mode switching available via a dedicated application or gaming peripherals. The tutorial video provided by the team illustrated microcontroller programming, device communication protocols, and a simulated mobile app interface, while the documentation outlined configuration parameters for each mode. These elements are presented in

Figure 8, which combines a tutorial screenshot with an excerpt from the application interface simulation.

The Smart Living Room group developed a system offering four pre-defined lighting scenes, namely "morning," "lunch," "movie night," and "guests," that could be triggered automatically or manually. Automated blinds and window control systems were calibrated to adjust to sunlight and indoor conditions, with the objective of enhancing comfort and energy efficiency. The presence-based temperature reduction function was employed to optimize energy use in unoccupied rooms. The system integrates data from motion, light, and temperature sensors to dynamically adjust the living room environment without requiring manual intervention. In the video tutorial, the group demonstrated scene-switching logic, microcontroller programming, and real-time data transmission, accompanied by a comprehensive technical summary in the accompanying documentation. As illustrated in

Figure 9, a combination of selected tutorial screenshots and a segment of the structured technical report is employed to demonstrate the implementation of these features.

In summary, the prototyping phase revealed a diversity of organizational approaches among the teams, ranging from straightforward implementations to more elaborate, multi-layered configurations. The projects also differed in the complexity of their automation functions and the degree to which students leveraged simulation tools to integrate logic, spatial design, and user interaction into cohesive smart room solutions.

4.2. Survey Results

In order to provide a comprehensive evaluation of the outcomes of the project, an anonymous post-project survey was conducted among the students. The survey was completed by 12 out of 18 participants, thereby providing a representative insight into perceptions of the project's tools, methodology, organization, and skill development. The questionnaire was constructed to combine closed-ended questions (multiple-choice and Likert-scale) with open-ended questions, thus allowing for both quantitative and qualitative evaluation.

4.2.1. Technical and Methodological Aspects

Students evaluated the usefulness of tools applied in the project. Cisco Packet Tracer was clearly the most valued tool, followed by Sweet Home 3D/Floorplanner, while Padlet was recognized primarily for its role in organizing teamwork (see

Table 4).

The findings of this study corroborate the pivotal function of simulation and visualization platforms in facilitating students' conceptualization and evaluation of smart room solutions, with the Padlet platform operating as an ancillary collaborative instrument. Open-ended responses further emphasized that experimenting with Cisco Packet Tracer and visualizing designs in 3D tools provided students with a practical sense of how their ideas could function in real environments.

Furthermore, an evaluation of the implementation of DT in the structuring of academic work was conducted by the students. While the majority of respondents found it beneficial in terms of facilitating teamwork and translating user needs into technical features, a significant proportion remained neutral, indicating a need for further clarification and guidance on the application of the method (see

Table 5).

The ratings indicate that DT was generally perceived as beneficial, though some students experienced difficulty in fully engaging with the methodology due to their limited prior experience with user-centered design approaches. This observation is consistent with open-ended comments suggesting that more structured, step-by-step support in applying DT stages would facilitate a more profound understanding of the subject matter and render the process more intuitive.

With regard to the development of technical skills in the domains of the Internet of Things (IoT), automation, and simulation, the majority of students expressed a strong conviction of the project's impact, with the majority of respondents assigning a high or very high rating to the perceived benefit (see

Table 6).

This finding serves to substantiate the claim that the project led to a significant enhancement in the practical competencies of the participants with regard to the design and simulation of smart building systems. Responses in the open-ended section indicated that these skills felt directly applicable to future academic and professional tasks, particularly through exposure to new tools and the opportunity to test complex automation scenarios in a safe, simulated environment.

4.2.2. Organizational Aspects and Soft Skills

Students were also invited to evaluate the project in terms of teamwork and organizational skills. The majority of respondents assigned a high or very high rating to these benefits, indicating an appreciation for the collaborative nature of work (see

Table 4).

Table 7.

Benefits for teamwork and organizational skills.

Table 7.

Benefits for teamwork and organizational skills.

| Evaluation |

Percentage of students |

| Very high |

28% |

| High |

39% |

| Medium |

33% |

These responses emphasize the importance of blended collaboration and shared digital workspaces in facilitating group coordination. In accordance with the open-ended responses, a significant proportion of students expressed that, while teamwork was rewarding, clearer task division and intermediate milestones could further improve coordination and reduce workload imbalances.

In response to the question regarding the clarity of project goals and tasks, a divergent set of responses was obtained. While a proportion exceeding fifty per cent of students found them clear, some indicated a need for more structured guidance and better-defined milestones (see

Table 8).

This finding suggests that, while the project framework was comprehensible to the majority, enhancements could be made to enhance transparency and task distribution. The survey results further corroborated this, with several students calling for more upfront information about assessment criteria and project expectations.

With regard to the complexity of the project, the majority of respondents described it as "sometimes difficult but feasible", indicating that while the project posed challenges, it remained achievable for students at this stage of study (see

Table 6).

Table 9.

Perceived difficulty of the project.

Table 9.

Perceived difficulty of the project.

| Evaluation |

Percentage of students |

| Sometimes difficult but feasible |

83% |

| Adequate |

17% |

The obtained results confirm that the project was appropriately challenging, engaging students in meaningful tasks without overwhelming them. Open-ended responses indicated that, while the workload was indeed challenging, particularly towards the conclusion of the semester, the sense of accomplishment upon completion was a significant factor for many participants.

4.2.3. Insights from Open-Ended Questions

In order to develop the most important themes and suggestions indicated by students in the open-ended questions, and to complement the findings from the previous subsections, a selection of the most significant responses was analyzed.

In the following comments, students highlighted several key strengths of the project. The opportunity to utilize novel tools and simulate smart room environments was met with considerable enthusiasm: “Learning new tools that enable the implementation of similar tasks/projects.” The opportunity to experiment with automation scenarios was valued by others: “Possibility to experiment with different automation scenarios and simulate them.” The importance of teamwork and the observation of group dynamics was emphasized by other participants: “It was more important for me to see how much people care about a given project and how much they are contributing to it.”

With regard to areas for improvement, the following recurrent suggestions were provided and specified by students:

Earlier projects start to reduce the end-of-semester workload: “Completing such a project at a different time would make it less stressful”;

More structured consultations and instructor support during design stages: “On-site group consultations with the instructor are necessary”;

Opportunities for intergroup presentations to exchange feedback: “Adding the ability to present the project to other groups and discuss it together”.

In this section, the author selected only several responses that had the most significant impact as positive and creative feedback. These responses provided both affirmation of the project's value and constructive suggestions for its future refinement. These comments indicate that, while students recognized the project's practical and collaborative nature, they also expressed a desire for more explicit guidance, expanded consultation opportunities, and a schedule that better aligns with the semester workload. These aspects are examined and discussed in further detail in next

Section 5, where their implications for improving the course design are discussed in the context of existing literature.

5. Discussion

The results obtained in this study provide important insights into the integration of simulation-based learning, DT, and BL in smart systems education. The findings of this study indicate that such an approach serves to enhance not only the technical competencies of students but also to cultivate creativity, user empathy, and collaboration. These skills have been identified as being of paramount importance for engineers operating within complex socio-technical contexts [

4,

13]. It is imperative to emphasize that the ensuing discourse interprets these findings in the context of current research, with a particular emphasis on their implications for future educational practice.

This study confirms the pivotal role of simulation platforms in bridging conceptual learning with applied practice. The overwhelmingly positive reception of Cisco Packet Tracer (94% of respondents) highlights its relevance as an educational tool for modelling IoT-based building ecosystems. This observation is consistent with Kumar et al. [

6] and Sellberg et al. [

10], who emphasized the capacity of such virtual environments to facilitate safe experimentation and iterative refinement of complex systems. Furthermore, the combined utilization of Sweet Home 3D and Floorplanner enabled students to contextualize their designs spatially, thereby creating a more authentic and user-oriented experience. This approach is consistent with the recommendations put forward in [

8,

22].

With regard to DT, it should be noted that while the majority of students (67%) found it beneficial for teamwork and project structuring, qualitative feedback revealed difficulties in fully operating it at the early stages. This finding lends partial support to the observations of Muñoz et al. [

20] and McLaughlin et al. [

4], who contend that DT, when introduced to students with limited prior exposure, necessitates meticulous scaffolding. In the absence of such guidance, there is a risk that the methodology may be perceived as abstract, thereby diminishing its intended impact on empathy-driven problem formulation.

A significant finding of this study is that the BL framework, which combines asynchronous Padlet-based collaboration with synchronous consultations, effectively mirrors hybrid professional workflows. This contributes to the perspective advanced by Gudoniene et al. [

13], who conceptualize BL as a multifaceted phenomenon, emphasizing its function in fostering communication and organizational competencies in distributed teams. It is noteworthy that a significant proportion of students (67%) assigned a high or very high rating to the benefits pertaining to teamwork and organizational skills, thereby indicating that the collaborative nature of the course fulfilled its intended objectives. However, it is equally important to recognize that students requested more structured consultations and intermediate milestones. This finding suggests that, while autonomy fosters a sense of agency in learning, it must be balanced with clear coordination mechanisms to prevent uneven distribution of workload, a tension also observed by Andrews et al. [

28] in similar hybrid project environments.

The findings indicate that students valued the project for its practical relevance and direct applicability to real-world scenarios. It was emphasized by several respondents that experimenting with automation in Packet Tracer and visualizing solutions in Sweet Home 3D substantially deepened their understanding of system-user interactions. This finding aligns with the conclusions of Sellberg et al. [

10], who posited that the integration of simulation-based learning with context-specific design tasks fosters more profound conceptual engagement. Conversely, a recurring challenge identified by students concerned the clarity of project goals and assessment criteria, particularly in the initial stages. Moreover, the accumulation of tasks at the conclusion of the semester was identified as a contributing factor to stress, underscoring the necessity for enhanced workload distribution. The absence of intergroup feedback mechanisms was also highlighted, suggesting untapped potential for peer-driven cross-fertilization of ideas. These observations are in alignment with those of Limaymanta et al. [

27], who emphasized the necessity of transparent frameworks and iterative peer interactions in active, project-based learning environments.

Taken together, these findings indicate several directions for improving the course structure. Introducing project work earlier in the semester could mitigate the end-of-term workload peak while enabling deeper iteration cycles. Implementing structured checkpoints with clearly defined deliverables would enhance transparency and help maintain steady team progress. The expansion of DT support—through templates, illustrative cases, or short guided exercises—would likely make the methodology more accessible to students with limited design experience. Finally, incorporating intergroup exchange sessions could foster peer learning, broaden students’ exposure to diverse approaches, and strengthen the collaborative dimension of the course. In a broader context, these results underscore the potential of integrating DT, simulation, and BL as a modular, scalable approach for technical education. Its tool-agnostic design makes it readily adaptable to other curricula focusing on IoT, building automation, or interdisciplinary design challenges. This observation aligns with the paradigm shift in engineering education toward holistic, practice-oriented frameworks that prepare graduates for the complexities of digitally mediated professional environments [

3,

4,

5].

6. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that integrating computer-assisted tools with user-centered and collaborative methodologies creates an effective framework for smart systems education. By combining simulation platforms, spatial design environments, and digital collaboration tools within the BL environment, students were able to develop practical competencies in IoT-based building automation while enhancing their creativity, teamwork, and organizational skills. The application of simulation tools, particularly for modeling and testing smart building functions, has been identified as a pivotal mechanism for the translation of theoretical knowledge into applied system design within a risk-free, iterative environment. The findings also revealed that while DT effectively supported the structuring of projects and the translation of user needs into technical solutions, its application requires more structured guidance, especially for students unfamiliar with user-centered methodologies. Likewise, clearer project milestones and expanded consultation opportunities would further optimize team coordination and workload distribution.

Future work will focus on several key enhancements to the methodology, including earlier project initiation, improved scaffolding for Design Thinking, and the introduction of intergroup exchange sessions to promote peer learning. Another important direction involves integrating advanced simulation tools and AI-based evaluation mechanisms. Furthermore, additional case studies conducted in diverse academic and cultural settings are required to assess the universality of the approach and its adaptability to various areas of technical education. These developments aim to strengthen the framework’s scalability and relevance across a wide range of IoT- and automation-oriented curricula.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request due to restrictions (e.g., privacy, legal or ethical reasons).

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the author used ChatGPT (OpenAI, GPT-4.1) to support brainstorming project themes and synthesizing literature. The author has reviewed and edited the output and takes full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| BL |

Blended Learning |

| DT |

Design Thinking |

| FC |

Flipped Classroom |

| ICT |

Information and Communication Technology |

| IoT |

Internet of Things |

References

- Naccarelli, R.; Casaccia, S.; Pirozzi, M.; Revel, G.M. Using a Smart Living Environment Simulation Tool and Machine Learning to Optimize the Home Sensor Network Configuration for Measuring the Activities of Daily Living of Older People. Buildings 2022, 12, 2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggiulli, M.; Piscitelli, M.S.; Capozzoli, A. A Data-Driven Approach to Evaluate the Smart Readiness Indicator for the Functionality “Respond to Users’ Needs”. In Sustainability in Energy and Buildings 2023; Littlewood John R. and Jain, L. and H.R.J., Ed.; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2024; pp. 589–599. [Google Scholar]

- Koh, J.H.L.; Chai, C.S.; Wong, B.; Hong, H.-Y. Design Thinking and Education. In Design Thinking for Education; Koh, J.H.L., Chai, C.S., Wong, B., Hong, H.-Y., Eds.; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2015; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin, J.E.; Chen, E.; Lake, D.; Guo, W.; Skywark, E.R.; Chernik, A.; Liu, T. Design Thinking Teaching and Learning in Higher Education: Experiences across Four Universities. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0265902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taimur, S.; Onuki, M. Design Thinking as Digital Transformative Pedagogy in Higher Sustainability Education: Cases from Japan and Germany. Int J Educ Res 2022, 114, 101994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B.; Padmanabha, V.; P., J.; Dwivedi, R. Utilizing Packet Tracer Simulation to Modern Smart Campus Initiatives for a Sustainable Future. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 12th International Conference on Smart Energy Grid Engineering (SEGE); IEEE, August 18 2024; pp. 97–102.

- Demeter, R.; Kovari, A.; Katona, J.; Heldal, I.; Costescu, C.; Rosan, A.; Hathazi, A.; Thill, S. A Quantitative Study of Using Cisco Packet Tracer Simulation Software to Improve IT Students’ Creativity and Outcomes. In Proceedings of the 2019 10th IEEE International Conference on Cognitive Infocommunications (CogInfoCom); IEEE, October 1 2019; pp. 353–358. [Google Scholar]

- Ghaliya Alfarsi Using Cisco Packet Tracer to Simulate Smart Home. International Journal of Engineering Research and 2020, V8. [CrossRef]

- Kefalis, C.; Skordoulis, C.; Drigas, A. Digital Simulations in STEM Education: Insights from Recent Empirical Studies, a Systematic Review. Encyclopedia 2025, 5, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellberg, C.; Nazari, Z.; Solberg, M. Virtual Laboratories in STEM Higher Education: A Scoping Review. Nordic Journal of Systematic Reviews in Education 2024, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raes, A.; Detienne, L.; Windey, I.; Depaepe, F. A Systematic Literature Review on Synchronous Hybrid Learning: Gaps Identified. Learn Environ Res 2020, 23, 269–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozadowicz, A. Interactivity — A Key Element of Blended Learning with Flipped Classroom Approach. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 9th International Conference on e-Learning in Industrial Electronics (ICELIE); IEEE, October 17 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Gudoniene, D.; Staneviciene, E.; Huet, I.; Dickel, J.; Dieng, D.; Degroote, J.; Rocio, V.; Butkiene, R.; Casanova, D. Hybrid Teaching and Learning in Higher Education: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2025, 17, 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinel, C.; Schweiger, S. A Virtual Social Learner Community—Constitutive Element of MOOCs. Educ Sci (Basel) 2016, 6, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Rocke, S.; Pooransingh, A.; Ramlal, C.J. Improving Student Engagement in Teaching Electric Machines Through Blended Learning. IEEE Transactions on Education 2019, 62, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klentien, U.; Wannasawade, W. Development of Blended Learning Model with Virtual Science Laboratory for Secondary Students. Procedia Soc Behav Sci 2016, 217, 706–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ożadowicz, A. Modified Blended Learning in Engineering Higher Education during the COVID-19 Lockdown—Building Automation Courses Case Study. Educ Sci (Basel) 2020, 10, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gren, L. A Flipped Classroom Approach to Teaching Empirical Software Engineering. IEEE Transactions on Education 2020, 63, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collado-Valero, J.; Rodríguez-Infante, G.; Romero-González, M.; Gamboa-Ternero, S.; Navarro-Soria, I.; Lavigne-Cerván, R. Flipped Classroom: Active Methodology for Sustainable Learning in Higher Education during Social Distancing Due to COVID-19. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, C.B.; Nanclares, N.H.; Murillo Zamorano, L.R.; Sánchez, J.Á.L. Design Thinking in Higher Education. In Gamification and Design Thinking in Higher Education; Routledge: New York, 2023; pp. 37–61. [Google Scholar]

- Tekaat, J.L.; Anacker, H.; Dumitrescu, R. The Paradigm of Design Thinking and Systems Engineering in the Design of Cyber-Physical Systems: A Systematic Literature Review. In Proceedings of the ISSE 2021 - 7th IEEE International Symposium on Systems Engineering, Proceedings; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., September 13 2021. [Google Scholar]

- AL sultan, O.K.T.; Suleiman, A.R. Simulation of IoT Web-Based Standard Smart Building Using Packet Tracer. In Proceedings of the 2021 7th International Engineering Conference “Research & Innovation amid Global Pandemic" (IEC); IEEE, February 24 2021; pp. 48–53. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, A.; Ghayar, J.; Pendam, R.; Shinde, S. Design and Implementation of Smart Home Network Using Cisco Packet Tracer. ITM Web of Conferences 2022, 44, 01008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barriga, J.A.; Clemente, P.J.; Sosa-Sanchez, E.; Prieto, A.E. SimulateIoT: Domain Specific Language to Design, Code Generation and Execute IoT Simulation Environments. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 92531–92552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naccarelli, R.; Casaccia, S.; Pirozzi, M.; Revel, G.M. Using a Smart Living Environment Simulation Tool and Machine Learning to Optimize the Home Sensor Network Configuration for Measuring the Activities of Daily Living of Older People. Buildings 2022, 12, 2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwansa, G.; Ngandu, M.R.; Dasi, Z.S. Enhancing Practical Skills in Computer Networking: Evaluating the Unique Impact of Simulation Tools, Particularly Cisco Packet Tracer, in Resource-Constrained Higher Education Settings. Educ Sci (Basel) 2024, 14, 1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limaymanta, C.H.; Apaza-Tapia, L.; Vidal, E.; Gregorio-Chaviano, O. Flipped Classroom in Higher Education: A Bibliometric Analysis and Proposal of a Framework for Its Implementation. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning (iJET) 2021, 16, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, C.D.M.; Mehrubeoglu, M.; Etheridge, C. Hybrid Model for Multidisciplinary Collaborations for Technical Communication Education in Engineering. IEEE Trans Prof Commun 2021, 64, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGibney, A.; Rea, S.; Ploennigs, J. Open BMS - IoT Driven Architecture for the Internet of Buildings. In Proceedings of the IECON 2016 - 42nd Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society; IEEE, October 2016; pp. 7071–7076. [Google Scholar]

- Noga, M.; Ożadowicz, A.; Grela, J. Modern, Certified Building Automation Laboratories AutBudNet – Put “Learning by Doing” Idea into Practice. Electrical Review 2012, 137–141. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

The Padlet board (group A) with several notes, posts, materials, comments (screenshot with the original, real view—posts are in Polish, and they contain students’ contributions, remarks, discussions with additional comments and explanations in English).

Figure 1.

The Padlet board (group A) with several notes, posts, materials, comments (screenshot with the original, real view—posts are in Polish, and they contain students’ contributions, remarks, discussions with additional comments and explanations in English).

Figure 2.

The Padlet board (group A) with several notes, posts, materials, comments (screenshot with the original, real view—posts are in Polish, and they contain students’ ideas and links to results with additional comments and explanations in English).

Figure 2.

The Padlet board (group A) with several notes, posts, materials, comments (screenshot with the original, real view—posts are in Polish, and they contain students’ ideas and links to results with additional comments and explanations in English).

Figure 3.

The Padlet board (group B) with several notes, posts, materials, comments (screenshot with the original, real view—posts are in Polish, and they contain students’ contributions, remarks, discussions with additional comments and explanations in English).

Figure 3.

The Padlet board (group B) with several notes, posts, materials, comments (screenshot with the original, real view—posts are in Polish, and they contain students’ contributions, remarks, discussions with additional comments and explanations in English).

Figure 4.

The Padlet board (group B) with several notes, posts, materials, comments (screenshot with the original, real view—posts are in Polish, and they contain students’ ideas and links to results with additional comments and explanations in English).

Figure 4.

The Padlet board (group B) with several notes, posts, materials, comments (screenshot with the original, real view—posts are in Polish, and they contain students’ ideas and links to results with additional comments and explanations in English).

Figure 5.

The Padlet board (group C) with several notes, posts, materials, comments (screenshot with the original, real view—posts are in Polish, and they contain students’ contributions, remarks, discussions with additional comments and explanations in English).

Figure 5.

The Padlet board (group C) with several notes, posts, materials, comments (screenshot with the original, real view—posts are in Polish, and they contain students’ contributions, remarks, discussions with additional comments and explanations in English).

Figure 6.

The Padlet board (group B) with several notes, posts, materials, comments (screenshot with the original, real view—posts are in Polish, and they contain students’ ideas and links to results with additional comments and explanations in English).

Figure 6.

The Padlet board (group B) with several notes, posts, materials, comments (screenshot with the original, real view—posts are in Polish, and they contain students’ ideas and links to results with additional comments and explanations in English).

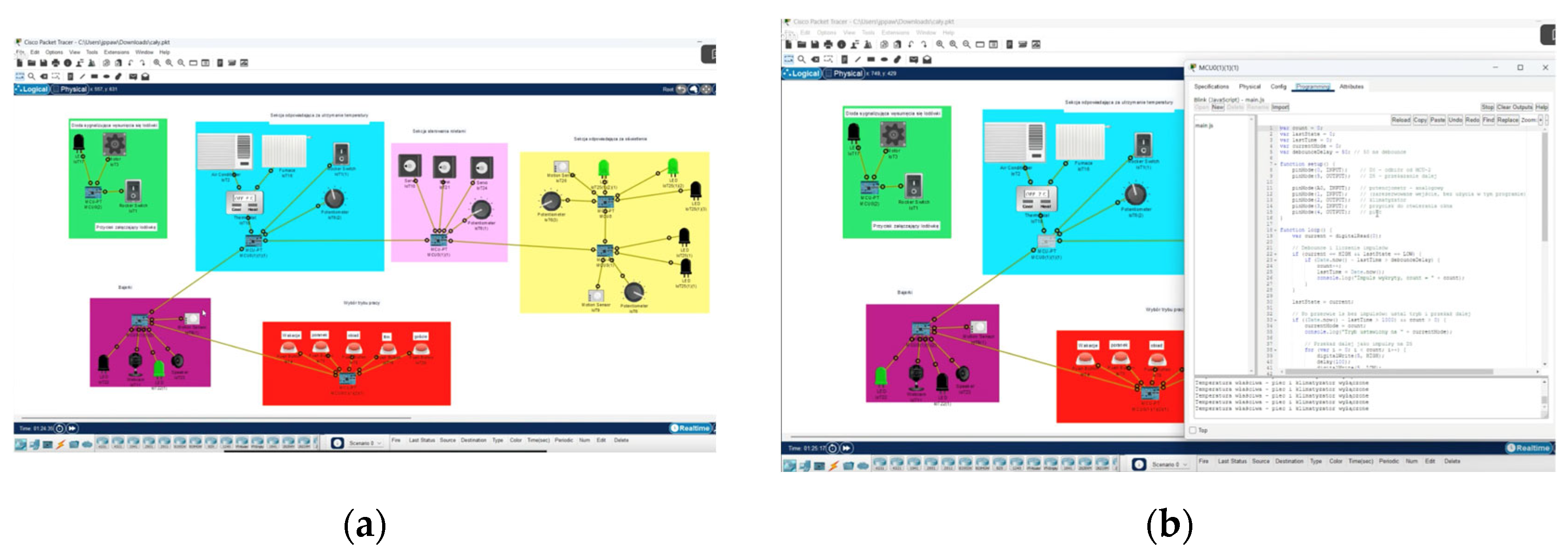

Figure 7.

Screenshots from the Cisco Packet Tracer - group A – original view with notes in Polish: (a) Project view with the microcontroller unit programming window; (b) Project view with the IoT device details window.

Figure 7.

Screenshots from the Cisco Packet Tracer - group A – original view with notes in Polish: (a) Project view with the microcontroller unit programming window; (b) Project view with the IoT device details window.

Figure 8.

Screenshots from the Cisco Packet Tracer - group B – original view with notes in Polish: (a) Project view with a window for programming the microcontroller unit and data transmission; (b) Project view with a window for visualizing the IoT module parameters from the mobile device simulation.

Figure 8.

Screenshots from the Cisco Packet Tracer - group B – original view with notes in Polish: (a) Project view with a window for programming the microcontroller unit and data transmission; (b) Project view with a window for visualizing the IoT module parameters from the mobile device simulation.

Figure 9.

Screenshots from the Cisco Packet Tracer - group C – original view with notes in Polish: (a) Project view with clearly marked component elements and operating modes; (b) Project view with the microcontroller unit programming window.

Figure 9.

Screenshots from the Cisco Packet Tracer - group C – original view with notes in Polish: (a) Project view with clearly marked component elements and operating modes; (b) Project view with the microcontroller unit programming window.

Table 1.

Overview of the project stages, tools used and expected learning outcomes.

Table 1.

Overview of the project stages, tools used and expected learning outcomes.

| Project stage |

Tools used |

Expected learning outcomes |

| Introduction & preparation |

Flipped Classroom lecture (online), Moodle resources |

Understanding of DT methodology

and project scope |

| Organizational meeting |

On-site session in laboratory |

Clarity of project goals, team roles,

and assessment criteria |

| Design Thinking process |

Padlet (collaborative platform) |

User analysis, ideation,

documentation, teamwork |

| Spatial design |

Sweet Home 3D / Floorplanner |

Planning room layouts and placement

of automation and smart devices |

| Simulation & prototyping |

Cisco Packet Tracer |

Virtual modeling of IoT-based smart building functions, iterative refinement |

| Presentation & evaluation |

Padlet (final documentation),

video tutorials |

Communication of solutions,

peer and instructor feedback |

Table 2.

Overview of the project stages, tools used and expected learning outcomes.

Table 2.

Overview of the project stages, tools used and expected learning outcomes.

| Tool |

Purpose |

Educational value |

| Sweet Home 3D / Floorplanner |

Creating visual room layouts and planning the placement of automation and smart

devices before functional modeling |

Enhancing spatial awareness,

contextualizing technical designs,

and improving the integration of automation systems into realistic environments |

| Cisco Packet Tracer |

Virtual modeling of IoT-based smart

building systems

and testing automation scenarios;

includes dedicated smart home

and smart building simulation modules with support for open IoT technologies |

Developing applied skills in IoT network design and iterative prototyping |

| Padlet |

Collaborative documentation of

Design Thinking stages, idea sharing,

and feedback exchange |

Enhancing teamwork, asynchronous

collaboration,

and project management skills |

| Loom |

Recording short video tutorials

demonstrating system functionalities |

Improving digital communication

and presentation competencies |

MS Word, OpenOffice,

LaTeX Overleaf |

Preparing simplified technical

documentation summarizing system

architecture, functionalities,

and user-oriented features |

Building technical reporting skills

and translating complex systems

into accessible documentation |

Table 3.

Design Thinking process: stages, student activities, and project outputs.

Table 3.

Design Thinking process: stages, student activities, and project outputs.

| Design Thinking stage |

Key students’ activities |

Project outputs |

| Empathize |

In-depth analysis of assigned user groups, mapping daily routines,

identifying pain points

and expectations for smart living

environments (Padlet) |

User profiles with documented

needs and priorities |

| Define |

Synthesizing findings into structured problem statements, identifying

design constraints and measurable

project goals (Padlet) |

Clear problem definitions

with prioritized design objectives |

| Ideate |

Generating a wide range of solution concepts, group discussions to evaluate feasibility and potential impact,

selecting the most promising ideas

for further development (Padlet) |

Conceptual solution outlines

and prioritized proposals |

| Prototype |

Translating selected ideas into

functional system models within

the simulation environment (Sweet Home 3D, Packet Tracer), establishing logical automation structures, designing device interactions, and programming universal microcontroller units

available in the software to implement custom smart building functions |

Configured simulation models

representing realistic

smart building scenarios

with programmed automation logic |

| Test |

Presenting the functioning

of designed applications through

instructional video tutorials,

highlighting different organizational approaches to activating and managing smart functions (Packet Tracer) |

Video presentations demonstrating system operation and documenting

varied strategies for function activation |

Table 4.

Most useful tools for project implementation (multiple responses allowed).

Table 4.

Most useful tools for project implementation (multiple responses allowed).

| Tool |

Percentage of students |

| Cisco Packet Tracer |

94% |

| Sweet Home 3D / Floorplanner |

72% |

| Padlet |

50% |

Table 5.

Evaluation of Design Thinking use in the project.

Table 5.

Evaluation of Design Thinking use in the project.

| DT Evaluation |

Percentage of students |

| Very helpful |

6% |

| Rather helpful |

61% |

| Neutral |

33% |

Table 6.

Benefits for technical skills development (IoT, automation, simulation).

Table 6.

Benefits for technical skills development (IoT, automation, simulation).

| Evaluation |

Percentage of students |

| Very high |

22% |

| High |

72% |

| Medium |

6% |

Table 8.

Clarity of project goals and tasks.

Table 8.

Clarity of project goals and tasks.

| Evaluation |

Percentage of students |

| Very clear |

28% |

| Rather clear |

28% |

| Medium |

22% |

| Insufficiently clear |

22% |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).