Submitted:

07 August 2025

Posted:

08 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

Sources of the Biological Materials

Sampling of the Biological Materials

Trapping and Identification of Weed Seeds and Propagules from Samples

Screening Consignments for Phytosanitary Measures at the Port of Entry

Approach Rate

Data Analysis

Results

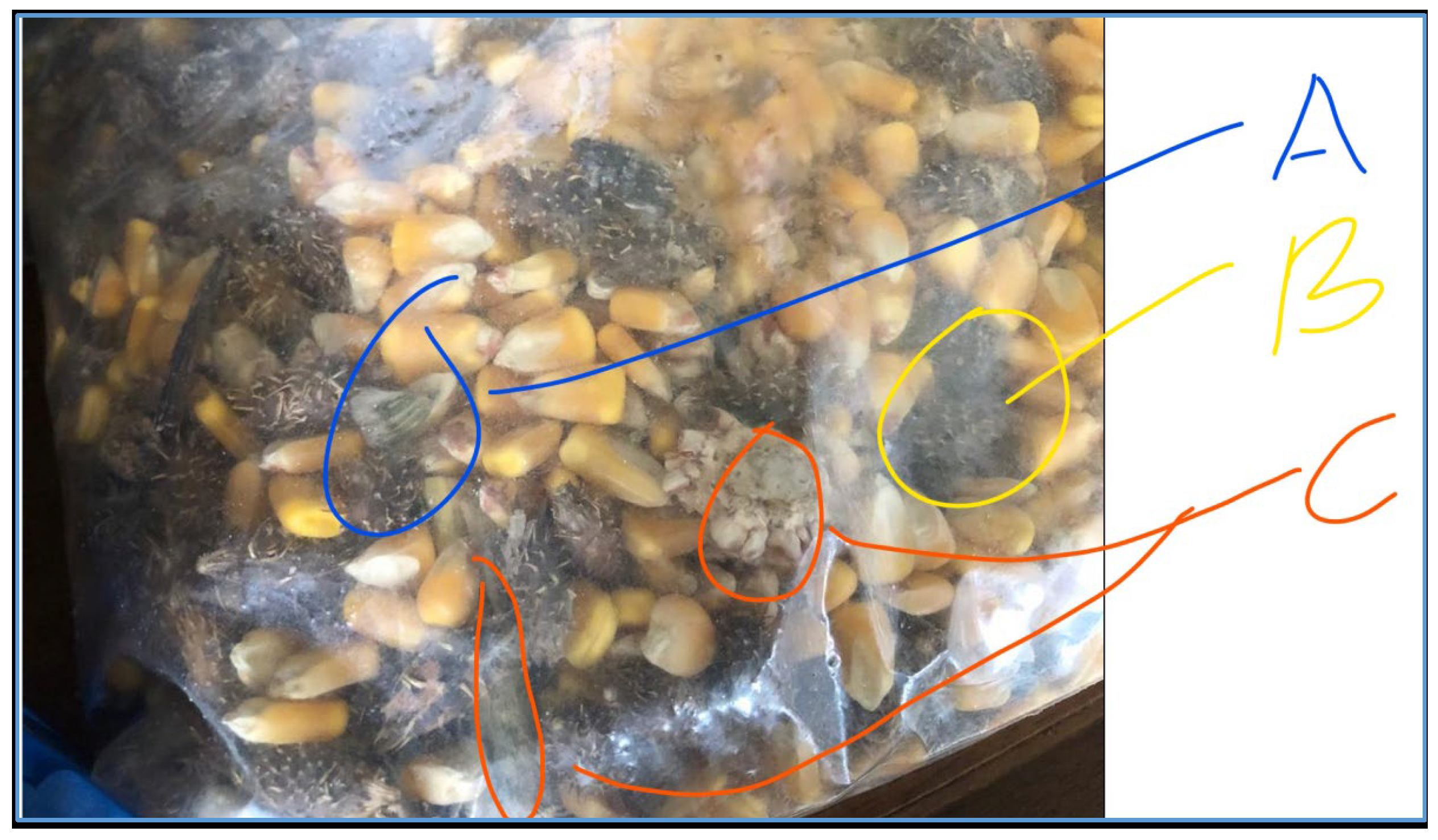

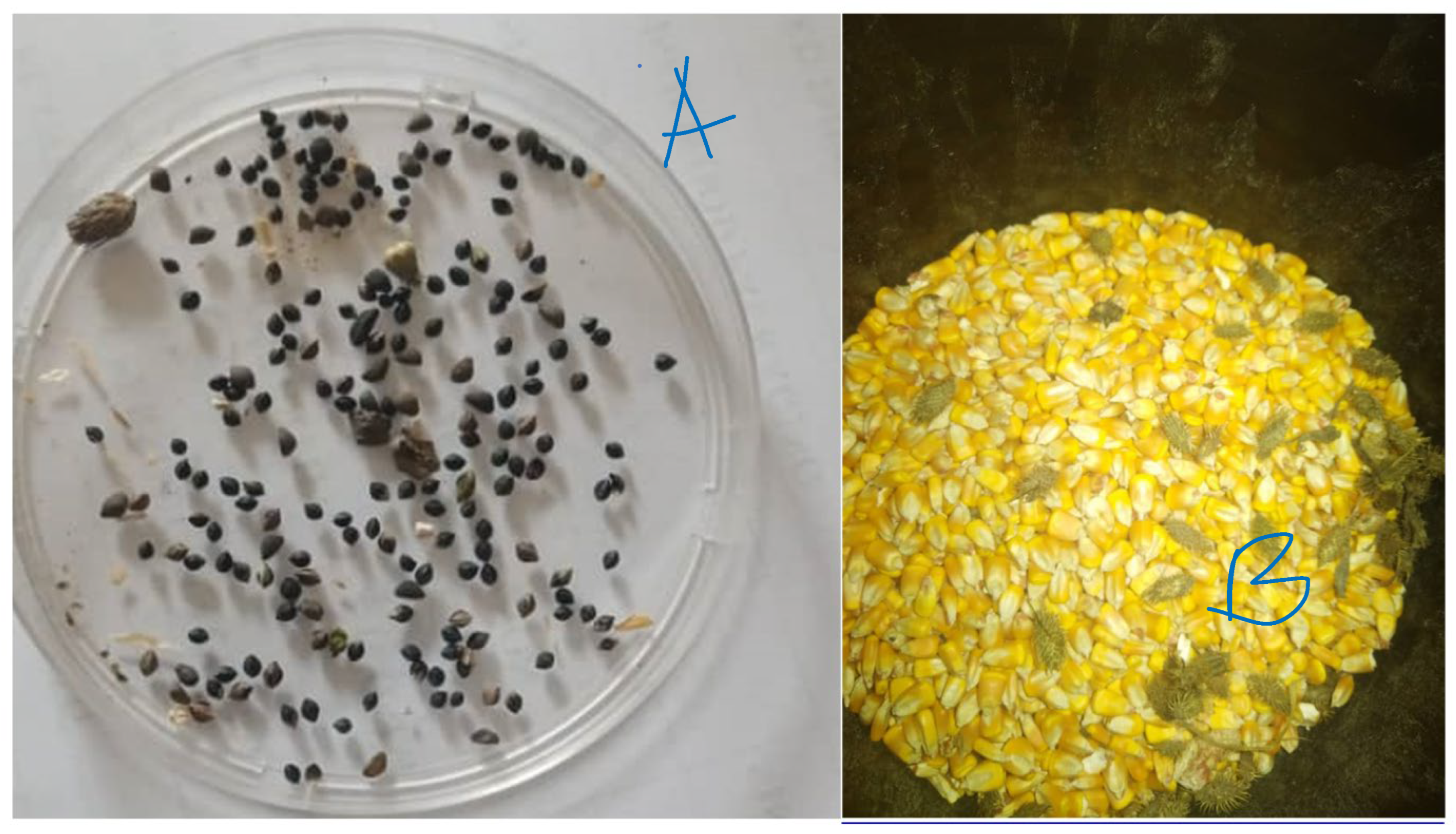

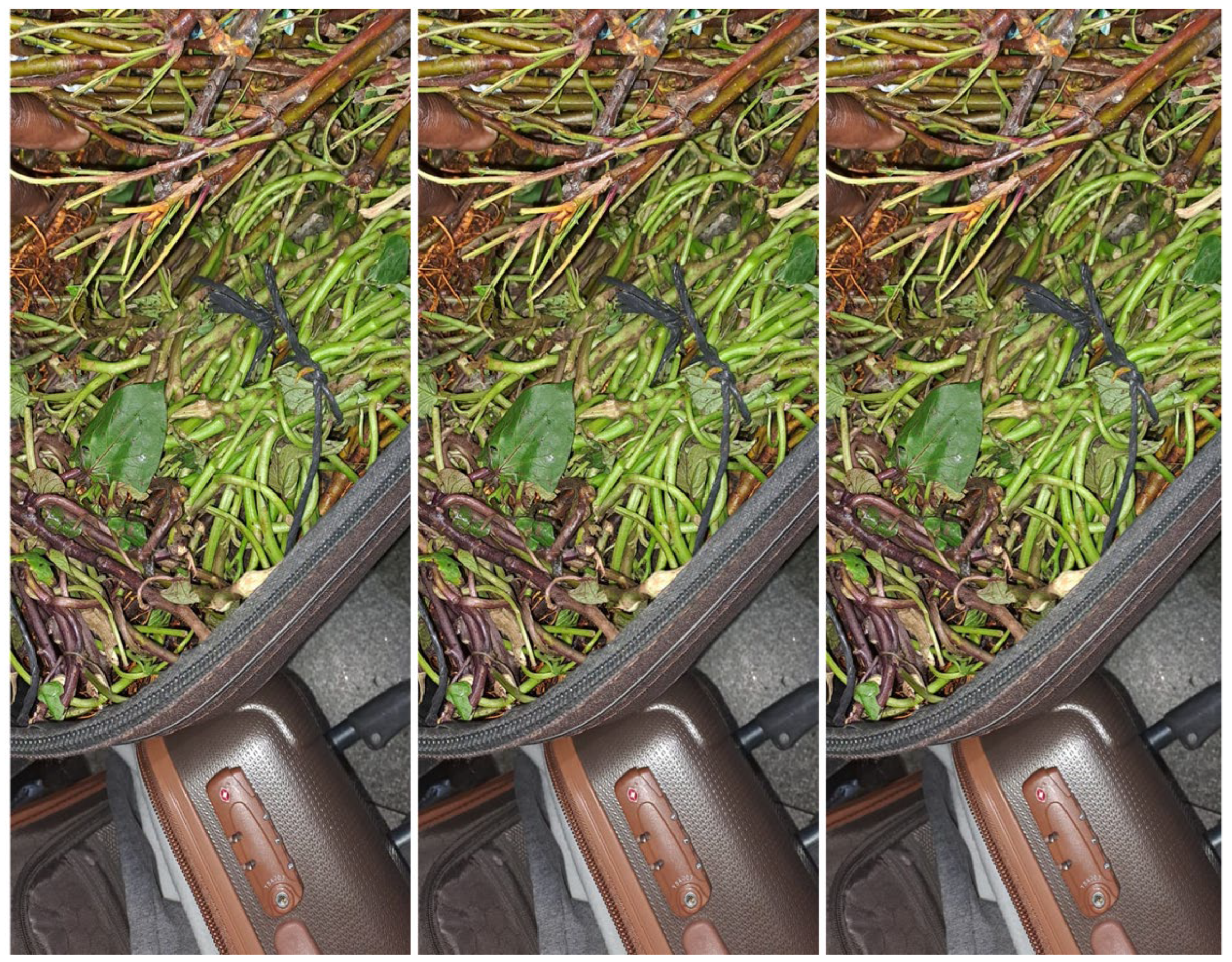

Weed Species Diversity in Pest Pathways Intercepted at Zimbabwe Ports of Entries

Occurrence and Distribution of the Weed Threats Found Associated with Cross Border Traffic at Zimbabwean Ports of Entries

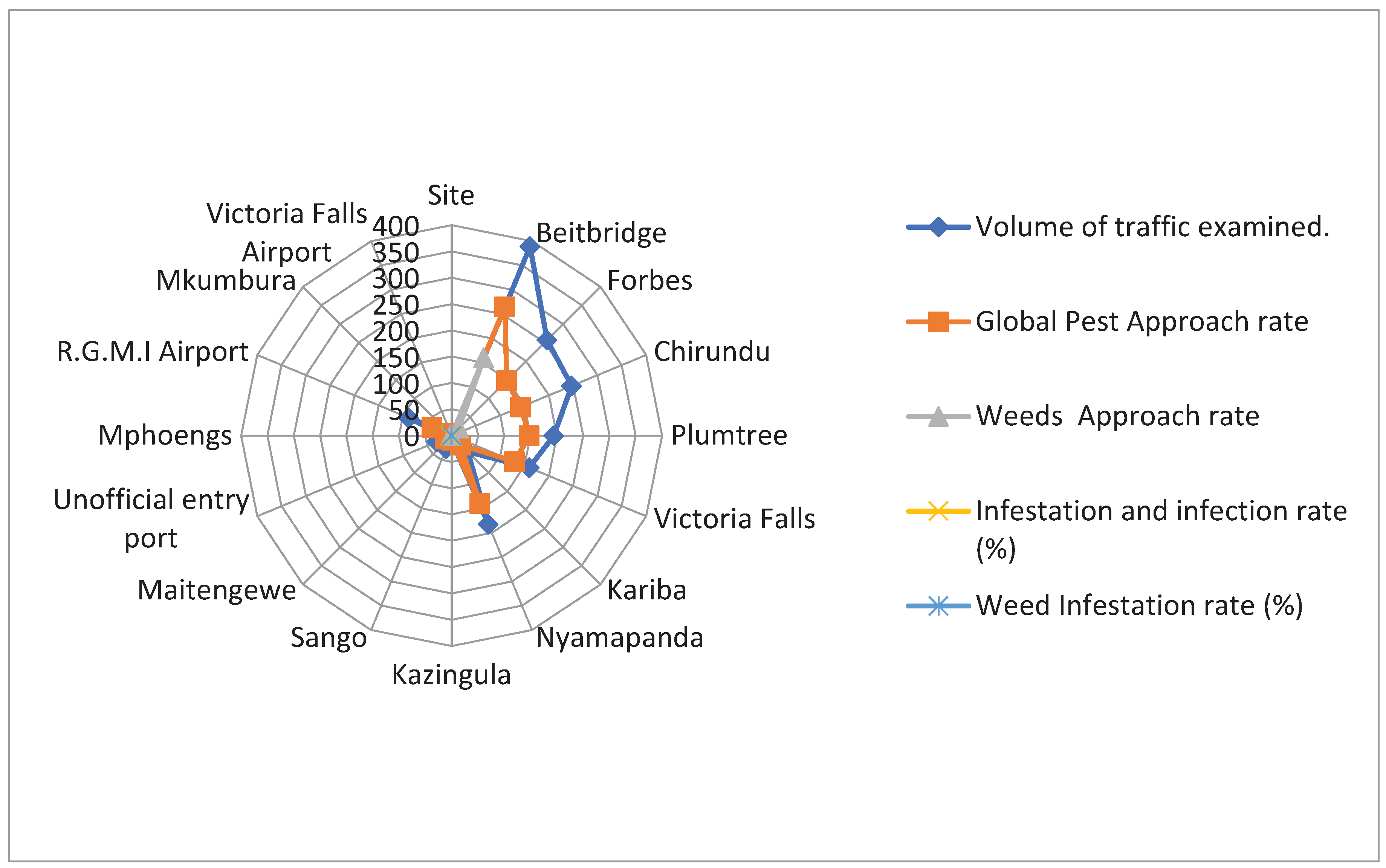

Approach Rates for the Weeds Found in Association with Cross-Border Traffic in Zimbabwe

| Pest Category | Samples Size Analyzed | Pest Approach Rate | Pest Approach Rate Frequency (%) | Pest Infestation Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weeds | 1668 | 182 | 16.95% | 10.91% |

| Other pests | 1668 | 894 | 83.05% | 53.60% |

| Freedom from pests | 1668 | 725 | - | 35.49% |

| Mean | 1668 | 600 | 50% | 33% |

| Standard Deviation | 0 | 372 | 47% | 21% |

|

Site (Port Of Entry) |

Volume Of Traffic Examined. | All Pest Approach Rates | Weeds Approach Rate | Infestation And Infection Rate (%) | Weed Infestation Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beitbridge | 389 | 265 | 160 | 68% | 10.09% |

| Forbes | 257 | 148 | 20 | 58% | 4.05% |

| Chirundu | 247 | 142 | 0 | 57% | 0.00% |

| Plumtree | 194 | 148 | 0 | 76% | 0.00% |

| Victoria Falls | 160 | 130 | 0 | 81% | 0.00% |

| Kariba | 44 | 25 | 0 | 57% | 0.00% |

| Nyamapanda | 182 | 140 | 0 | 77% | 0.00% |

| Kazingula | 10 | 9 | 0 | 90% | 0.00% |

| Sango | 27 | 0 | 0 | 0% | 0.00% |

| Maitengewe | 8 | 6 | 0 | 75% | 0.00% |

| Unofficial entry port | 31 | 13 | 0 | 42% | 0.00% |

| Mphoengs | 14 | 3 | 0 | 21% | 0.00% |

| R.G.M.I Airport | 88 | 40 | 1 | 45% | 4.18% |

| Mkumbura | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0% | 0.00% |

| Victoria Falls Airport | 5 | 5 | 1 | 100% | 2.78% |

| Pearson Chi-Square (5%) | 0.256 | 0.235 | 0.254 | 0.250 | 0.215 |

| Likelihood Ratio (5%) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1,00 | 1.00 |

| Site / Port Of Entry | Mean Total Pest Approach Rate | Mean Weed Approach Rate | Mean Pest Infestation/Infection Rate (%). | Mean Weed Infestation Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1) Beit-bridge | 5 | 6.67b | 41.00a | 10.09 |

| 2) Chirundu | 2.1 | 0.0 | 26.5ab | 0 |

| 3) Forbes | 6.8 | 0.83a | 27.5ab | 4.05 |

| 4) Kariba | 0.8 | 0a | 18.3b | 0 |

| 5) Kazingula | 0.3 | 0a | 15.3bcd | 0 |

| 6) Maitengewe | 0.3 | 0a | 7.0cd | 0 |

| 7) Mphoengs | 0.3 | 0a | 1.8cd | 0 |

| 8) Mkumbura | 0.0 | 0a | 0cd | 0 |

| 9) Nyamapanda | 2.1 | 0a | 25.4ab | 0 |

| 10) Plumtree | 2.3 | 0a | 23.7b | 0 |

| 11) R.G.M.I Airport | 3.5 | 0.4a | 24.5b | 4.18 |

| 12) Sango | 0.0 | 0a | 0cd | 0 |

| 13) Unofficial entry port | 0.0 | 0.0a | 21.9b | 0 |

| 14) Victoria Falls | 0.40 | 0a | 25.8ab | 0 |

| 15) Victoria Falls Airport | 0.2 | 0.04a | 12.5bcd | 2.78 |

| Grand mean | 4.5 | 0.51 | 18.1 | 1.41 |

| F Probability | P = 0.181 | P<0.001 | P <0.001 | P <0.001 |

| LSD (5%) | NS | 1.382 | 15.66 | 3.885 |

| CV% | - | 50.7 | 22.6% | 93.8% |

| Source of variation d. f. | s.s. | m. s.v.r. F pr. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year Stratum | 3 | 17.72 | 5.91 | 1.05 | |

| Year x Site Stratum | |||||

| Site | 14 | 991.41 | 70.81 | 12.57 | <.001 |

| Residual | 42 | 236.53 | 5.63 | 1.00 | |

| Year x Site x Main x Pathway | 2 | 184.02 | 92.01 | 16.29 | <.001 |

| Site x Main-Pathway | 28 | 1982.81 | 70.81 | 12.53 | <.001 |

| Residual | 90 | 508.50 | 5.65 | 0.32 | |

| Year.Site.Main_Pathway.Sub_Pathway | |||||

| Sub Pathway | 3 | 132.02 | 44.01 | 2.49 | 0.063 |

| Site x Sub_Pathway | 42 | 1493.11 | 35.55 | 2.01 | 0.001 |

| Residual | 135 | 2387.88 | 17.69 | ||

| Total 359 | 7933.99 | ||||

| Pathway | Mean Weed Approach Rate | Mean Weed Infection Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Organic Materials | 0b | 0b |

| Other Plants | 1.52a | 4.22a |

| Solanaceae | 0b | 0b |

| Grand-Mean | 0.51 | 1.41 |

| F-Probability | (P>0.005) | P<0.001 |

| LSD (5%) | 0.610 | 1.849 |

| CV % | 50.7% | 93.8% |

| Sub-Pathway | Weed Approach Rate | Mean Infestation Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Growing media | 0b | 1.41 |

| other use | 1.52a | 2.13 |

| packaging material | 0b | 1.41 |

| Propagation | 0.51ab | 0.69 |

| Grand Mean | 0.51 | 1.41 |

| F. Prob. | P<0.001 | P= 0.712 |

| LSD (5%) | 1.315 | NS |

Infestation Frequencies for Weeds Found in Association with Cross-Border Traffic into Zimbabwe

Discussion

Conclusion

Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgements

Conflict of Interest

References

- Abalaka S, Fatihu M, Ibrahim N, Ambali S (2014). Haematotoxicity of ethanol extract of Adenium obesum (Forssk) Roem & Schult stem bark in Wistar rats. Tropical Journal of Pharmaceutical Research, 13(11), 1883. [CrossRef]

- Alegbeleye O, Odeyemi O A, Strateva M, Stratev D (2022). Microbial spoilage of vegetables, fruits and cereals. Applied Food Research, 2(1), 100122. [CrossRef]

- Awasthi L P, Das S, Lee R F, Pattanayak S (2024). Plant Pathology. CRC Press.

- Bailey J (2008). First steps in qualitative data analysis: Transcribing. Family Practice, 25(2), 127–131. [CrossRef]

- Bhunjun C S, Phillips A J L, Jayawardena R S, Promputtha I, Hyde K D (2021). Importance of Molecular Data to Identify Fungal Plant Pathogens and Guidelines for Pathogenicity Testing Based on Koch’s Postulates. Pathogens, 10(9), 1096. [CrossRef]

- Brooks D R, Hoberg E P, Boeger W A, Trivellone V (2022). Emerging infectious disease: An underappreciated area of strategic concern for food security. Transboundary and Emerging Diseases, 69(2), 254–267. [CrossRef]

- CABI (2021). Potato virus Y (potato mottle) (p. 43762) [Dataset]. [CrossRef]

- Campbell F, Schlarbaum S (2014). Fading Forests III. American Forests: What Choice Will We Make. The Nature Conservancy, Arlington, VA, and the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN.

- Cantamutto M, Poverene M (2007). Genetically modified sunflower release: Opportunities and risks. Field Crops Research, 101, 133–144. [CrossRef]

- Chakuya J, Furamera CA, Jimu D, Nyatanga T T C (2023). Effects of the invasive Hedychium gardnerianum on the diversity of native vegetation species in Bvumba Mountains, Zimbabwe. International Journal of Environmental Studies, 80(5), 1322–1329. [CrossRef]

- CODEX (1995). CODEX STANDARD FOR MAIZE (CORN). Codex Standard 153-1985.

- Collier J (2024). Import Health Standard: Seeds for Sowing. Ministry for Primary Industries. New Zealand.

- Cui B, Hu C, Fan X, Cui E, Li Z, Ma H, Gao F (2020). Changes of endophytic bacterial community and pathogens in pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) as affected by reclaimed water irrigation. Applied Soil Ecology, 156, 103627. [CrossRef]

- Douma J C, Pautasso M, Venette R C, Robinet C, Hemerik L, Mourits M C M, Schans J, Van Der Werf W (2016). Pathway models for analysing and managing the introduction of alien plant pests an overview and categorization. Ecological Modelling, 339, 58–67. [CrossRef]

- Dubey S C, Gupta K, Akhtar J, Chalam V C, Singh M C, Khan Z, Singh S P, Kumar P, Gawade B H, Kiran R, Boopathi T, Kumari P (2021). Plant quarantine for biosecurity during transboundary movement of plant genetic resources. Indian Phytopathology, 74(2), 495–508. [CrossRef]

- Eschen R, Rigaux L, Sukovata L, Vettraino A M, Marzano M, Grégoire JC (2015). Phytosanitary inspection of woody plants for planting at European Union entry points: A practical enquiry. Biological Invasions, 17(8), 2403–2413. [CrossRef]

- Fisher R (1954). The Design of Experiments. Hafner Publishing Company.

- Friel S, Schram A, Townsend B (2020). The nexus between international trade, food systems, malnutrition and climate change. Nature Food, 1(1), 51–58. [CrossRef]

- Froese J G, Murray J V, Beeton N J, Van Klinken R D (2024). The Pest Risk Reduction Scenario Tool (PRReSTo) for quantifying trade-related plant pest risks and benefits of risk-reducing measures. Crop Protection, 176, 106484. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Bastidas F (2022). Fusarium oxysporum f.sp. Cubense tropical race 4 (Foc TR4) (p. 59074053) [Dataset]. [CrossRef]

- Getahun S, Kefale H (2023). Problem of Water Hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes (Mart.)) in Lake Tana (Ethiopia): Ecological, Economic, and Social Implications and Management Options. International Journal of Ecology, 2023, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Gilioli G, Schrader G, Grégoire JC, MacLeod A, Mosbach-Schulz O, Rafoss T, Rossi V, Urek G, Van Der Werf W (2017). The EFSA quantitative approach to pest risk assessment – methodological aspects and case studies. EPPO Bulletin, 47(2), 213–219. [CrossRef]

- Gomez KA, Gomez A A (1984). Statistical Procedures for Agricultural Research. Wiley and Sons, New York. ISBN 0-471-87092-7.

- Government of Zimbabwe (2000). Seeds (Certification Scheme) Notice, 2000 (No. [CAP. 19:13; Version Statutory Instrument 213 of 2000.). Government Printers.

- Griffin R (2017). Introduction to the International Symposium for Risk-Based Sampling. International Symposium for Risk- Based Sampling, 6–11. https://nappo.org/application/files/4215/8746/3813/RBS_Symposium_Proceedings_-10062018-e.pdf.

- Guha Roy S, Dey T, Cooke D E L, Cooke L R (2021). The dynamics of Phytophthora infestans populations in the major potato-growing regions of Asia – A review. Plant Pathology, 70(5), 1015–1031. [CrossRef]

- Https://www.health.qld.gov.au/. (n.d.).

- IPPC Secretariat (2016a). Categorization of commodities according to their pest risk. FAO on behalf of the Secretariat of the International Plant Protection Convention (IPPC). https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/24313cae-2ca8-49a2-85cd-16da3fe320e1/content.

- IPPC Secretariat (2016b). INTERNATIONAL STANDARDS FOR PHYTOSANITARY MEASURES ISPM 27 Diagnostic protocols for regulated pests (ISPM No. 32). FAO on behalf of the Secretariat of the International Plant Protection Convention (IPPC). https://assets.ippc.int/static/media/files/publication/en/2024/07/ISPM_05_2024_En_Glossary_PostCPM-18_InkAmdts_2024-07-29.pdf.

- IPPC Secretariat (2019). Categorization of commodities according to their pest risk. International Standards for Phytosanitary Measures 32. (No. International Standards for Phytosanitary Measures 32.; Version 2019).

- IPPC Secretariat (2023). Guidelines for a phytosanitary import regulatory system. Produced by the Secretariat of the International Plant Protection Convention Adopted 2023; published 2023. https://assets.ippc.int/static/media/files/publication/en/2023/04/ISPM_20_2023_En_Import_PostCPM-17_2023-04-14.pdf.

- IPPC Secretariat (2024). Glossary of phytosanitary terms. International Standard for Phytosanitary Measures. FAO on behalf of the Secretariat of the International Plant Protection Convention (IPPC).

- Kachena L, Shackleton R T (2024). The impact of the invasive alien plant Vernonanthura polyanthes on conservation and livelihoods in the Chimanimani uplands of Zimbabwe. Biological Invasions, 26(6), 1749–1767. [CrossRef]

- Kasem SM, Baka Z, El- Metwally M A, Ibrahim A A, Soliman M (2024). Biocontrol Agents of Mycoflora to Improve the Physiological and Genetic Characteristics of Maize Plants. Egyptian Journal of Botany, 64(3), 298–317. [CrossRef]

- Little T M, Hills F J (1978). Agricultural Experimentation. Design and Analysis. Wiley and Sons, New York. Wiley and Sons, New York. I.

- Lovett G, Weiss M, Liebhold A, Holmes T, et la (2016). Nonnative forest insects and pathogens in the United States: Impacts and policy options. Ecological Applications, 26, 1437-1455.

- Macêdo R L, Haubrock P J, Klippel G, Fernandez R D, Leroy B, Angulo E, Carneiro L, Musseau C L, Rocha O, Cuthbert R N (2024). The economic costs of invasive aquatic plants: A global perspective on ecology and management gaps. Science of The Total Environment, 908, 168217. [CrossRef]

- Mahabaleswara S L, Hodson D P, Alemayehu Y, Mwatuni F, Macharia I, Bekele B, Bomet D, Ngaboyisonga C, Mdili K S, Msiska K, Kamangira D, Mudada N, Prasanna B M (2024). Monitoring and tackling Maize Lethal Necrosis (MLN) in Eastern and Southern Africa from 2014 to 2024. CIMMYT. [CrossRef]

- Mapaura A, Timberlake J (Edds) (2004). A checklist of Zimbabwean vascular plants. Southern African Botanical Diversity Network Report No. 33. SABONET, Pretoria and Harare. Southern African Botanical Diversity Network Report No. 33. SABONET. www.sabonet.org.

- Meissner H Ε, Bertone C A, Ferguson L M, Lemay A V, Schwartzburg K A (2008). Proceedings of the Caribbean Food Crops Society. Proceedings of the Caribbean Food Crops Society., 44 (2), 584–592.

- Meurisse N, Rassati D, Hurley B P, Brockerhoff E G, Haack R A (2019). Common pathways by which non-native forest insects move internationally and domestically. Journal of Pest Science, 92(1), 13–27. [CrossRef]

- Mikulyuk A (2009). Lemna perpusilla (duckweed) (p. 30243) [Dataset]. [CrossRef]

- Montilon V, Potere O, Susca L, Bottalico G (2023). Phytosanitary Rules for the Movement of Olive (Olea europaea L.) Propagation Material into the European Union (EU). Plants, 12(4), 699. [CrossRef]

- Mujaju C, Mudada N, Chikwenhere G P (2021). Invasive Alien Species in Zimbabwe (Southern Africa). In T. Pullaiah & M. R. Ielmini (Eds.), Invasive Alien Species (1st ed., pp. 330–361). Wiley. [CrossRef]

- Munhoz T, Vargas J, Teixeir, L, Staver C, Dita M (2024). Fusarium Tropical Race 4 in Latin America and the Caribbean: Status and global research advances towards disease management. Frontiers in Plant Science, 15. [CrossRef]

- Musabayana Z, Mandumbu R, Mapope N (2024). Allelopathy as a tool for invasiveness of Tithonia diversifolia extracts through in vitro suppression of crop seeds germination. African Journal of Plant Science, 18(4), 28–40. [CrossRef]

- Musawa G (2022). Exposure Risk Assessment to Aflatoxins Through the Consumption of Peanut Among Children Aged 6-59 Months in Lusaka District [Master Thesis]. School of Veterinary Medicine, University of Zambia.

- Mutebi R R, Ario A R, Nabatanzi M, Kyamwine I B, Wibabara Y, Muwereza P, Eurien D, Kwesiga B, Bulag, L, Kabwama S N, Kadobera D, Henderson A, Callahan J H, Croley T R, Knolhoff A M, Mangrum J B, Handy S M, McFarland M A, Sam, J L F, Zhu BP (2022). Large outbreak of Jimsonweed (Datura stramonium) poisoning due to consumption of contaminated humanitarian relief food: Uganda, March–April 2019. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 623. [CrossRef]

- Mwangi R W, Mustafa M, Charles K, Wagara I W, Kappel N. (2023). Selected emerging and reemerging plant pathogens affecting the food basket: A threat to food security. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research, 14, 100827. [CrossRef]

- Naidu V S G R (2012). Hand Book on Weed Identification. Directorate of Weed Science Research, Jabalpur, India Pp 354. https://dwr.icar.gov.in/Downloads/Books_and_Other_publications/Hand%20Book%20on%20-%20Weed%20Identification.pdf.

- NAPPO (2017). Proceedings International Symposium for Risk Based Sampling. North American Plant protection Organisation (NAPPO) Mexico, USA, Canada. https://nappo.org/application/files/4215/8746/3813/RBS_Symposium_Proceedings_-10062018-e.pdf.

- Njambuya J, Stiers I, Triest L (2011). Competition between Lemna minuta and Lemna minor at different nutrient concentrations. Aquatic Botany, 94(4), 158–164. [CrossRef]

- Njoroge S M C, Matumba L, Kanenga K, Siambi M, Waliya, F, Maruwo J, Monyo E S (2016). A Case for Regular Aflatoxin Monitoring in Peanut Butter in Sub-Saharan Africa: Lessons from a 3-Year Survey in Zambia. Journal of Food Protection, 79(5), 795–800. [CrossRef]

- Nyoni (2022). Smuggled tomatoes flood Zim markets Agriculture. Southern Eye. https://www.newsday.co.zw/southerneye/agriculture/article/200004041/smuggled-tomatoes-flood-zim-markets.

- Ormeno J, Sepulveda P, Rojas R, Araya J (2006). Datura genus weeds an epidemiological factor of Alfalfa mosaic virus, Cucumber mosaic virus and Potato virus Y on Solanaceous crops. Agric. Technica, 66, 333-341.

- Osman A E, Bahhady F, Hassan N, Ghassali F, Al Ibrahim T (2006). Livestock production and economic implications from augmenting degraded rangeland with Atriplex halimus and Salsola vermiculata in northwest Syria. Journal of Arid Environments, 65(3), 474–490. [CrossRef]

- Osman A, Mansor M, Abu A (1994). A preliminary study on the distribution and association of mosquito larvae with aquatic weeds. Journal of Bioscience, 54.

- Rojas-Sandoval J (2020). Vitex agnus-castus (chaste tree) (p. 56520) [Dataset]. [CrossRef]

- Shafi Z, Ilyas T, Shahid M, Vishwakarma S K, Malviya D, Yadav B, Sahu P K, Singh U B, Rai J P, Singh H B, Singh H V (2023). Microbial Management of Fusarium Wilt in Banana: A Comprehensive Overview. In U. B. Singh, R. Kumar, & H. B. Singh (Eds.), Detection, Diagnosis and Management of Soil-borne Phytopathogens (pp. 413–435). Springer Nature Singapore. [CrossRef]

- Shaima Hassan Ali Al-Abbasi, Harith Mustafa, Al-Naqib A T H, Ghufran Aldouri (2021). Weed of Convolvulus arvensis damage and control methods. Unpublished. [CrossRef]

- Sharma M, Dhaliwal I, Rana K, Delta A, Kaushik P (2021). Phytochemistry, Pharmacology, and Toxicology of Datura Species—A Review. Antioxidants, 10(8), 1291. [CrossRef]

- Tambo J A, Kansiime M K, Rwomushana I, Mugambi I, Nunda W, Mloza Banda C, Nyamutukwa S, Makale F, Day R (2021). Impact of fall armyworm invasion on household income and food security in Zimbabwe. Food and Energy Security, 10(2), 299–312. [CrossRef]

- The Head Plant Quarantine Services Institute (2020). Annual Report 2020. [Annual Report]. Plant Quarantine Services Institute, Department of Research and Specialist Services, Mazowe, Zimbabwe.

- The Head Plant Quarantine Services Institute (2022). General Phytosanitary Inspecting and Control Standard Operation Procedures Standard: Operating Procedures for Phytosanitary Inspection and Certification of Plants/ Plant Products & other Regulated Articles. (Version 1). PLANT QUARANTINE SERVICES INSTITUTE Mazowe Research Centre P. Bag 2007 Mazowe, Zimbabwe.

- The Head Plant Quarantine Services Institute (2023). Annual report 2023. [Annual Report]. Plant Quarantine Services Institute, Department of Research and Specialist Services, Mazowe, Zimbabwe.

- Toumasis P, Vrioni G, Gardeli I, Michelaki A, Exindari M, Orfanidou M (2025). Macrophomina phaseolina: A Phytopathogen Associated with Human Ocular Infections—A Case Report of Endophthalmitis and Systematic Review of Human Infections. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(2), 430. [CrossRef]

- Travlos I, Gazoulis I, Kanatas P, Tsekoura A, Zannopoulos S, Papastylianou P (2020). Key Factors Affecting Weed Seeds’ Germination, Weed Emergence, and Their Possible Role for the Efficacy of False Seedbed Technique as Weed Management Practice. Frontiers in Agronomy, 2, 1. [CrossRef]

- Trkulja V, Tomić A, Iličić R, Nožinić M, Milovanović T P (2022). Xylella fastidiosa in Europe: From the Introduction to the Current Status. The Plant Pathology Journal, 38(6), 551–571. [CrossRef]

- Waithira J (2023). Status of Maize Lethal Necrosis in Seed Production Systems and Interaction of Viruses Causing the Disease in Kenya [Thesis, University of Nairobi]. [University of Nairobi]. http://erepository.uonbi.ac.ke/handle/11295/164469.

- Webber J (2010). Pest Risk Analysis and Invasion Pathways for Plant Pathogens. New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science.

- Webber J, Rose J (2008). Dissemination of Aerial and Root Infecting Phytophthoras by Human Vectors 1. Proc. Sudden Oak Death Third Sci. Symp.

- Williams L J, Abdi H (n.d.). Fisher’s Least Significant Difference (LSD) Test.

- Wilson C E, Castro K L, Thurston G B, Sissons A (2016). Pathway risk analysis of weed seeds in imported grain: A Canadian perspective. NeoBiota, 30, 49–74. [CrossRef]

- Zhang B (2012). Evolutionary genetics and human assisted movement of a globally invasive pest (Russian wheat aphid: Diuraphis noxia). [Doctor of Philosophy thesis]. Queensland University of Technology Brisbane, Australia.

- Zhang S, Griffiths J S, Marchand G, Bernards M A, Wang A (2022). Tomato brown rugose fruit virus: An emerging and rapidly spreading plant RNA virus that threatens tomato production worldwide. Molecular Plant Pathology, 23(9), 1262–1277. [CrossRef]

| Name of the entry point | Locations (GPS: Latitude, longitude)# | Category and Characteristic of the Entry Port | Customs declarations characteristics | Operating times of the day | Bordering countries |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Beitbridge Border Port | 22°13’05”S 29°59’10”E | Land border | Commercial and non-commercial cargo | Twenty four hours | South Africa |

| 2. Chirundu Border Port | 16°02’19”S 28°51’09”E | Land border | Commercial and non-commercial cargo | Twenty four hours* | Zambia * |

| 3. Forbes Border | 19°00’18”S 32°42’42”E | Land border | Commercial and non-commercial cargo | Twenty four hours** | Mozambique** |

| 4. Kariba Border Port | 16°31’33”S 28°45’40”E | Land border | Commercial and non-commercial cargo | 0600–2000 hours | Zambia |

| 5. Kazingula Border Port | 17°47’57”S 25°15’24”E | Land border | Commercial and non-commercial cargo | 0600–1800 hours | Botswana |

| 6. Maitengewe Border Port | 20°06’51”S 27°13’49”E | Land border | Non-commercial cargo | 0600–1800 hours | Botswana |

| 7. Mkumbura Border Port | 16°12’04”S 31°41’21”E | Land border | non-commercial cargo | 0600 – 1800 hours | Mozambique |

| 8. Mphongs Border Port | 21°17’26”S 27°53’58”E | Land border | non-commercial cargo | 0600–1800 hours | Botswana |

| 9. Nyamapanda Border Port | 16°57’46”S 32°51’50”E | Land border | Commercial and non-commercial cargo | 0600–2200 hours | Mozambique |

| 10. Plumtree Border Port | 20°32’28”S 27°44’15”E | Land border | Commercial and non-commercial cargo | 0600–2200 hours | Botswana |

| 11. Robert Gabriel Mugabe International Airport (RGMIA) | 17°56’19”S 31°06’54”E | Airport | Commercial and non-commercial cargo | Twenty four hours | Multi-countries |

| 12. Sango Border Port | 22°04’10”S 31°41’01”E | Land border | Commercial and non-commercial cargo | 0600 – 1800 hours | Mozambique |

| 13. Unofficial crossing points | N/A | Unofficial crossing points along the Zimbabwean border. | None | Unofficial | Botswana. Zambia, Zimbabwe and Mozambique |

| 14. Victoria falls Border Port | 17°55’42”S 25°51’49”E | Land border | Commercial and non-commercial cargo | 0600 – 2000 hours | Zambia |

| 15. Victoria Falls International Airport | 18°05’44”S 25°50’59”E | Airport | Commercial and non-commercial cargo | 24 hours | Multi-countries |

| Pathway type | Purpose of the import | Description of the pathway | Comment on this categorization |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Solanaceae species (Juss). |

Other use | Solanaceae plant material imported for the purpose other than propagation. | The singling out of solanecous plant pest pathway was ascertained from the claim by Ormeno et al. (2006) that solanaceae plants from various parts of the world are critical for their roles in hosting pathogens or diseases of the cultivated plants and hence their importance in the studies of transboundary movement of pests as depicted. The solanaceae contain 98 genera and some 2,700 species (Ormeno et al., 2006). |

| Propagation (planting – including replanting) (IPPC Secretariat, 2024) | Solanaceae plant species material imported with the intention to ensuring their subsequent growth, reproduction or propagation. | ||

| Organic Materials |

Growing media | Any material imported with the intention in which plant roots are growing or intended for that purpose (IPPC Secretariat, 2024, 2023). | Materials like Peat and Peat-Like Materials; wood Residues; Wood residues ; Bagasse; Rice Hulls; Soil; etc. |

| Packaging materials | Imported Material used in supporting, protecting or carrying a commodity (IPPC Secretariat, 2024, 2023) | Packaging material capable of being pathways of pests such as pallets, used bags, etc. | |

| Other plant species |

Propagation (planting including replanting) | Any other plant species material apart from the Solanaceae family imported with an intention to ensure their subsequent growth, reproduction or propagation for solanaceae plants (IPPC Secretariat, 2024). | All propagative materials used for the purposes of reproducing plants or the process of creating new plants from a variety of sources: seeds, cuttings, bulbs and other plant parts (such as whole plants, flowers, tissues, etc.). |

| Other use | Any plant material other than the Solanaceae family imported for any purpose other than propagation (IPPC Secretariat, 2024). | All other plant materials and products imported for the purpose not including propagation. |

| Common Name | Order | Species | Pathways | Purpose of Importation | Pest Status In Zimbabwe | Biosecurity Concern associated with the pest |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| European bindweed. | Solanales | Convolvulus arvensis L. | Wheat grain | Consumption | Absent (Intercepted only) | Invasive weed species, that, reduce the value and importance of agricultural land (Shaima Hassan Ali Al-Abbasi et al., 2021). |

| Common Sunflower | Asterales | Helianthus annuus L. | Maize grain and soya beans | Consumption | Present | Risk of accidental genome contamination with poorly adapted genomes (Cantamutto & Poverene, 2007). |

| Thorn apple, and jimsonweed | Solanales | Datura stramonium L. | Maize grain. | Consumption | Present | Food and feed poisoning (Mutebi et al., 2022; Sharma et al., 2021) |

| Common duckweed | Alismatales | Lemna minor L. | Passenger baggage | Feed production | Present. In national parks (Mapaura & Timberlake, 2004) | A nuisance in water bodies, rice field agroecosystem and in irrigation and drainage channel reservoirs and recreational lakes. Several mosquito larvae, particularly those of Culex bitaeniorhynchus, C. tritaeniorhynchus and Ficalbia minima, are closely associated with Lemna Invasive (Njambuya et al., 2011; A. E. Osman et al., 2006) |

| Lesser duckweed | Alismatales | Lemna aequinoctialis Welw. | Passenger baggage | Feed production | Present in national parks (Mikulyuk, 2009; Mapaura & Timberlake, 2004) | A nuisance in water bodies. |

| Desert rose | Gentianales | Adenium obesum ((Forssk.) Roem. & Schult.) | Passenger baggage | Unknown (suspected ornamental) | Absent (intercepted and destroyed) (The Head Plant Quarantine Services Institute, 2023) | All parts of the plant are toxic and may cause slow heartbeat, low blood pressure, lethargy, dizziness and stomach upset.(Abalaka et al., 2014) (Https://Www.Health.Qld.Gov.Au/, n.d.) |

| Lilac Chaste Tree | Lamiales |

Vitex agnus-castus L. |

Passenger baggage | Unknown (suspected ornamental) | Absent (intercepted only) (The Head Plant Quarantine Services Institute, 2023; Rojas-Sandoval, 2020) | Vitex agnus-castus is widely cultivated as an ornamental and for medicinal use, but it often behaves as a weed and has the potential to grow in a wide range of climates and soil types with a high seed production rate (Rojas-Sandoval, 2020). |

| Apples | Rosales | Malus domestica | Passenger baggage | Planting | Present | Planting material with soil are threats as soils carries a variety of microorganism that threaten the country biosecurity systems (IPPC Secretariat, 2019). |

| Grapes | Vitales | Vitis vinifera L | Passenger baggage | Planting | Present | Planting material with soil are threats as soils carries a variety of microorganism that threaten the country biosecurity systems (Mahabaleswara et al., 2024). |

| Oranges | Sapindales | Citrus × sinensis | Passenger baggage | Planting | Present | Planting material with soil is a threat as soils carry a variety of microorganism that threaten the country’s biosecurity systems (IPPC Secretariat, 2019). |

| Sweet potatoes | Solanales | Ipomea batatas | Passenger baggage | Planting | Present | Introduction of plants for planting need to follow regulated biosecurity measures to reduce accidental introduction of new exotic pest species (Eschen et al., 2015). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).