1. Introduction

HCC continues to pose a significant oncological challenge and remains a major concern in the field of medicine. HCCs that are detected through routine surveillance often have a favorable prognosis, with a disease-free survival rate of over 50% at the five-year mark. On the other hand, HCCs that are detected after the onset of symptoms tend to have a poor prognosis, with a five-year survival rate of less than or equal to 10%. [

1]

One method of assessing the rate of HCC growth is by measuring the tumor volume doubling times (TVDTs), which involves comparing the tumor volumes obtained from consecutive imaging studies. A study conducted by

An et al. aimed to measure the TVDTs of 175 HCC patients, and the results ranged from 11 to 851.2 days, with a median of 85.7 days. [

2]Another systematic literature review conducted by

Nathani et al. included twenty studies involving 1334 patients, and the pooled TVDTs ranged from 3.9 to 5.3 months. [

3] These findings highlight the importance of timely intervention for patients with HCC.

Typically, a regular patient with HCC undergoes a series of steps before TARE, including discussion at a tumor board, admission, mapping, discharge, and readmission for the planned intervention. However, this sequential process may lead to delays in patient management. Therefore, there is a need for a protocol that can expedite the management of HCC patients. One such protocol is the recently developed OMT protocol, which proposes that the patient be admitted, mapped, and treated in a single admission, thereby accelerating the overall management of the patient. In this study, our objective is to evaluate the effectiveness of this newly developed protocol by comparing the survival outcomes before and after its implementation. Assessing the protocol and its effectiveness will provide valuable insights to improve the efficiency of HCC management.

2. Patients and Methods

A retrospective cohort study to assess survival outcomes before and after implementation of the OMT protocol.

All patients in the study were diagnosed with HCC at King Abdulaziz Medical City in Riyadh and whom cases were discussed and approved by the local tumor board committee between the period of 2018 to 2023. The study data were collected and managed via REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at the Medical Imaging Department of King Abdulaziz Medical City, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. [

4,

5,

6] Data were retrospectively retrieved from the electronic medical records and radiology information systems. Baseline clinical, biochemical and imaging findings were retrieved. Portal vein tumoral thrombosis (PVTT) was classified according to the Cheng’s classification. [

6] The interval between MDT to TARE, mapping to TARE and survival from first TARE were calculated.

The recently introduced OMT protocol was applied in late 2020 with the availability of the SIR-Spheres® Y-90 resin microspheres FLEXdose Delivery Program (SIRTex, Massachusetts, USA). In the OMT protocol, patients were admitted, underwent hepatic mapping with lung shunt study, and received treatment the following day within a single hospital stay. The Y90 dose is administered on day 2 pre calibration to maximize the specific activity and reduce the potential embolic effect related to the number of microspheres. This streamlined approach aimed to expedite patient management and reduce the overall treatment time. Prior to implementing the OMT protocol, patients used to undergo the mapping done and then readmission for Y90 administration following dose procurement. This resulted in unnecessary delays in treatment administration or inability to deliver the dose due to disease progression or worsening general condition.

The study was approved by the institutional review board (study number NRR24/046/10, approval number 0000066324) and informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study.

3. Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 29. Continuous variables were reported as mean and standard deviation or median and interquartile range. Categorical variables were presented as frequency and percentage. To compare continuous variables among independent groups, either the t-test or Mann-Whitney U test was used, depending on the distribution of the data. For categorical variables, the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test was used as appropriate. Survival analysis was conducted by Kaplan-Meir and Cox regression. A two-sided p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all tests.

4. Results

A total of 185 patients (69.2% males) were included in the study, with 88 (47.6%) underwent TARE before the implementation of OMT system in 2021 (Group 1) and 97 (52.4%) afterwards (Group 2). The mean age of the entire cohort was 71 years (±12), with no significant difference between the two groups (p = 0.807). (

Table 1) A significantly larger number of patients treated before 2021 had an ECOG score of 0 (p < 0.001). Patients treated after 2021 more often had unilobar involvement, while those treated earlier were more likely to present with multifocal disease (p = 0.041). More patients with PVTT3 and PVTT4 were treated after the implementation of the OMT protocol (P=0.009) The target perfused liver volume was smaller in the OMT group 523.7±316.6 cc compared to 860±457.8 cc in the pre OMT group (P=0.005) without significant differences in the tumor volume or target tumor dose. (

Table 1)

The median time from multidisciplinary team (MDT) decision to transarterial radioembolization (TARE) was 22 days (IQR 10 to 43) across the entire cohort. When stratified by treatment period, the median time was significantly longer before OMT at 37 days (23 to 57), compared to 15 days (8 to 22) after OMT implementation (p < 0.001). The MDT to TARE interval was not associated with improved survival (HR: 1, 95%CI: 0.995 to 1.005, p = 0.994).

The median time from mapping to the first TARE procedure was 7.5 days (IQR: 1 to 23) for the overall cohort. Prior to OMT implementation, this interval was significantly longer at 21 days (14 to 33), compared to 1 day (1 to 5) after OMT (p<0.001). However, the mapping-to-TARE interval was not significantly associated with overall survival (HR: 1.002; 95% CI: 0.999 to 1.005; p = 0.160).

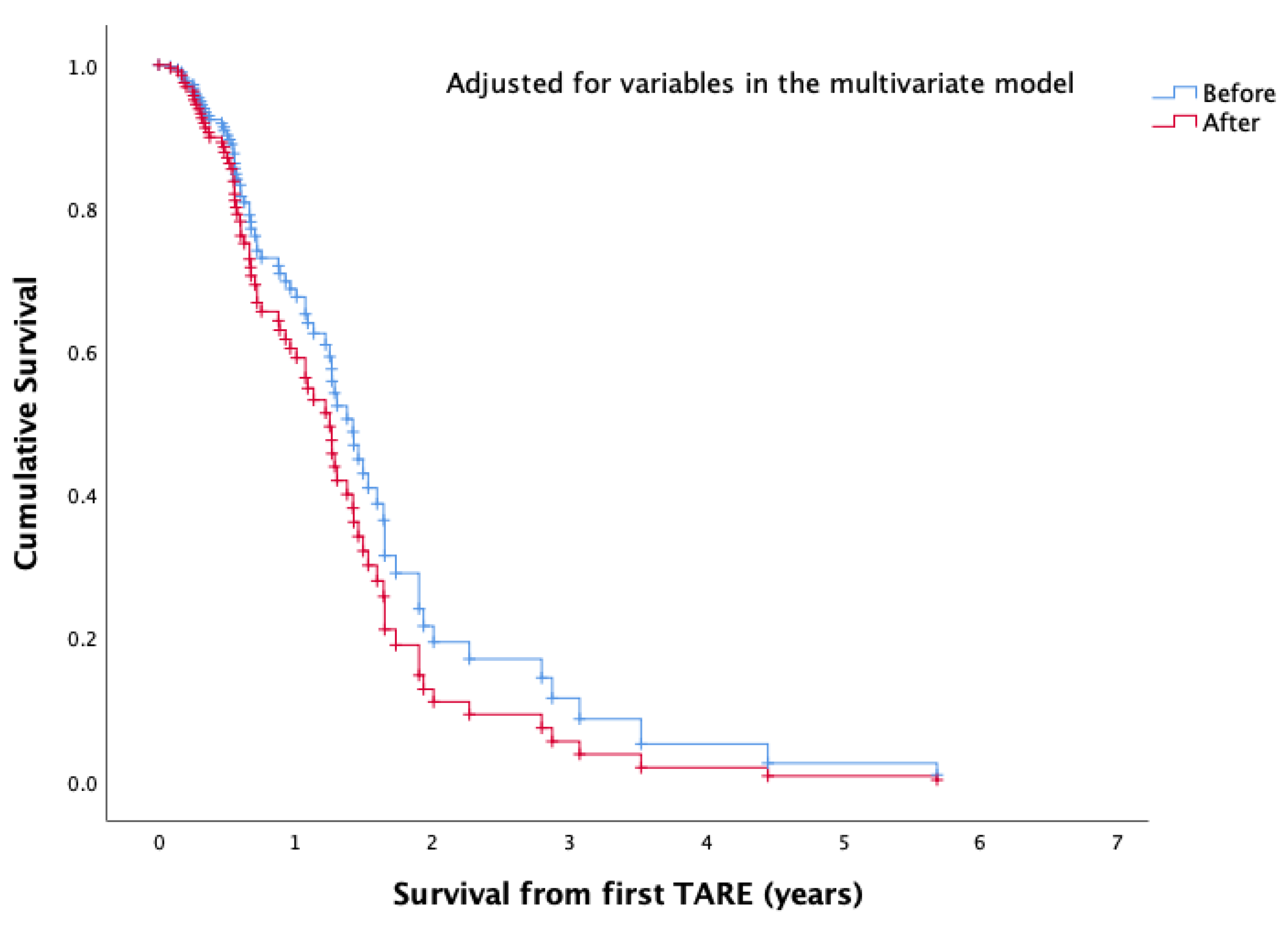

The median survival from the first TARE procedure was 1.4 years (95% CI: 1.1 to 1.6) overall. When stratified by treatment period, patients treated before OMT had a median survival of 1.5 years (95% CI: 1.2 to 1.9), while those treated after OMT implementation had a median survival of 1.2 years (95% CI: 0.9 to 1.6). The difference in survival between the two periods was not statistically significant (p = 0.415).

The survival difference before and after OMT was insignificant even after adjusting for all the variables in the multivariate model (HR: 1.343, 95% CI: 0.75 to 2.406, p = 0.321). (

Figure 1)

5. Discussion

Transarterial radioembolization (TARE) using Yttrium-90 (Y-90) microspheres is a well-established treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), particularly in patients who are not candidates for surgical resection or ablation. Traditionally, TARE involves a two-stage process: an initial mapping angiogram with technetium-99m macroaggregated albumin (Tc-99m MAA) simulation followed days to weeks later by the therapeutic delivery of Y-90 microspheres. While effective, this bifurcated model introduces logistical challenges, including multiple hospital admissions, increased patient anxiety, and delays in treatment delivery.

Several measures have been recently introduced to optimize and streamline the workflow of Y90 treatments including transradial approach, Order-Map-Treat (OMT) and Flexdose programs, single day/admission treatments, single session Y90 treatment without prior mapping and personalized dosimetry softwares. Such compressed timelines and workflow optimizations are especially valuable when rapid treatment decisions are clinically indicated, such as in patients at risk of tumor progression or portal vein thrombosis.

Recent studies have advocated for a single-day or single-admission model, often referred to as Order–Map–Treat (OMT), which consolidates pre-treatment mapping, dosimetry, and therapy into a single hospital visit. This approach has demonstrated feasibility, safety, and improved efficiency in patient care pathways. [

7,

8,

9] The OMT workflow is particularly relevant in the context of streamlined interventional oncology programs. Prior studies reported their experience of delivering both components of the TARE procedure on the same day during the COVID pandemic to maintain the service and minimize hospital stays. [

7,

10] Both studies confirmed the feasibility and safety of the same day protocol, offering a new approach to mitigate the logistical challenges and potential health risks associated with the conventional protocol of two separate admissions. Li et al reported a study of 34 TARE procedures with resin microspheres in 26 patients who underwent same day treatment including the pretreatment mapping and lung shunt fraction study. All procedures were technically successful and only 18% of patients were admitted briefly for observation and symptoms management with a mean total procedure time of 4.2 hours. [

8]

The introduction of the Flexdose delivery program allows personlaization of the administered dose based on the pretreatment angiography and intraprocedural cone-beam CT and offers the possibility of splitting of 90Y resin microsphere activity as needed. This feature of the resin microspheres provides flexibility for changes in the treatment plan and allows customization of the dose and number of particles based on the tumor characteristics including size, vascularity and number of supplying vessels. [

9]

Our institution has intially adopted the same day protocol in which both the mapping and the infusion are performed on one day enocounter. However, this was faced by several logistic challenges including the need to maintain the arterial access and catheter position for longer time, time management and organization between the IR and nuclear medicine departements, patient discomfort due the prolonged procedural and imaging times. Therefore, we modified the protocol to perform the mapping on the first day and the infusion on the following day. This offers more flexibility in time management and allows for better plannig and dose calcuation and reduces patient discomfort. Although this program has not shown significant survival benefits compared to the conventional treatment protocol, the reduction in drop out and time to treatment was evident. This is concordant with a prior study that shows significant reduction in time from the IR clinic visit to treatment from 61 days in the conventional groups compared to 26.5 days in the single session treatment group (p < 0.001). [

11] Nevertheless, the successful implementation of OMT requires robust pre-procedural imaging, patient selection, and coordination between nuclear medicine, interventional radiology, and radiation safety teams. Use of cone-beam CT, same-day SPECT/CT, and real-time dosimetry software has enabled accurate planning and confident administration of therapeutic doses within a single hospital visit.

Another iteration of TARE protocols is the administration of Y90 treatment without prior lung shunt fraction or SPECT/CT study in select patients. This approach utilizes intra-procedural imaging—primarily cone-beam CT to assess the hepatic arterial anatomy and exclude any extrahepatic gastrointestinal enhancement, thereby eliminating the need for a separate mapping procedure. In a recent case series, Berman et al. demonstrated that mapping-free single-session ablative Y-90 treatment was technically successful in 88% of patients, with no reported cases of radiation pneumonitis or non-target embolization [

12]. Gabr et al proposed streamlining radioembolization in UNOS T1/T2 hepatocellular carcinoma by eliminating lung shunt estimation. Patients with solitary HCC or ≤3 Tumors ≤3 cm with no prior history of TIPS can safely receive selective TARE without MAA study with no radiation risk to the lungs. [

13] Similar finding was observed by Mohnasky et al who compared a single session Y90 resin radiation segmentectomy without MAA to conventional Y90 glass protocol in select OPTN stage T2 HCC patients without MVI or TIPS. [

11] There were no ≥grade 3 adverse events and complete response was achieved in 11/12 of the single session patients. [

11] Eliminating the mapping session may be associated with cost reduction from nearly USD 64,000 to USD 38,000 [

11] Kim et al retrospectively compared 100 consecutive patients with HCC within the Milan criteria who underwent regular TARE (n = 38) to streamlined TARE without mapping (n = 62). There was no difference in serious adverse events, complete response or time-to-progression between the treatment protocols and they concluded that eliminating mapping was effective and safe in HCC patients within Milan criteria. [

14]

This study is limited by its retrospective nature, relatively small sample size and some differences in the baseline characteristics between the treatment groups. Patients in the pre OMT group were healthier with better ECOG status and more multinodular disease. On the other hand, patients in the OMT group had more unilobar disease and greater percentage of more advanced PVTT. These differences may be related to selection bias and changes in experience with TARE treatments, which may ultimately translate into differences in survival outcomes.

In conclusion, the OMT approach to Y-90 TARE represents a paradigm shift toward more patient-centered, efficient, and potentially cost-effective care for HCC. As centers gain experience and refine protocols, same-day/admission TARE or even TARE without mapping may become standard practice in appropriately selected patients.

Funding

The study was not supported by any funding.

Conflicts of Interest

Dr. M. Arabi is a proctor for Sirtex Medical.

References

- Bruix J, Sherman M, American Association for the Study of Liver D. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology 2011;53:1020-1022.

- An C, Choi YA, Choi D, et al. Growth rate of early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic liver disease. Clin Mol Hepatol 2015;21:279-286.

- Nathani P, Gopal P, Rich N, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma tumour volume doubling time: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut 2021;70:401-407.

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform 2019;95:103208.

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377-381.

- Shuqun C, Mengchao W, Han C, et al. Tumor thrombus types influence the prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma with the tumor thrombi in the portal vein. Hepatogastroenterology 2007;54:499-502.

- Frost JP, Bell J, Lawrance J, Najran P, Mullan D. Ambulatory Same-Day Map-and-Treat Angiography for Selective Internal Radiation Therapy Using a Transradial Approach. Cureus 2022;14:e27741.

- Li MD, Chu KF, DePietro A, et al. Same-Day Yttrium-90 Radioembolization: Feasibility with Resin Microspheres. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2019;30:314-319.

- Paladini A, Spinetta M, Matheoud R, et al. Role of Flex-Dose Delivery Program in Patients Affected by HCC: Advantages in Management of Tare in Our Experience. J Clin Med 2024;13.

- Elsayed M, Loya M, Galt J, et al. Same day yttrium-90 radioembolization with single photon emission computed tomography/computed tomography: An opportunity to improve care during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2021;13:440-452.

- Mohnasky M, Gad S, Fanous M, et al. Initial Experience with Single-Session Resin-Based Transarterial Radioembolization Mapping and Treatment of Small Hepatocellular Carcinomas. Cancers (Basel) 2025;17.

- Berman ZT, Pianka K, Qaseem Y, Redmond J, Minocha J. Single-Session Ablative Transarterial Radioembolization for Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma to Streamline Care: An Initial Experience. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2024;47:1239-1245.

- Gabr A, Ranganathan S, Mouli SK, et al. Streamlining radioembolization in UNOS T1/T2 hepatocellular carcinoma by eliminating lung shunt estimation. J Hepatol 2020;72:1151-1158.

- Kim HC, Suh M, Paeng JC, et al. Streamlining Radioembolization without Lung Shunt Estimation versus Regular Radioembolization in Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma within the Milan Criteria. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2025;36:78-87 e71.

Table 1.

Comparative Baseline Characteristics of Patients Treated with TARE Before and After 2021.

Table 1.

Comparative Baseline Characteristics of Patients Treated with TARE Before and After 2021.

| |

Total |

< 2021 |

≥ 2021 |

P value |

| N |

185 |

88 (47.6%) |

97 (52.4%) |

|

| Age (years) |

71±12 |

71±12 |

71±12 |

0.807 |

| Gender |

| Female |

57 (30.8%) |

25 (28.4%) |

32 (33%) |

0.527 |

| Male |

128 (69.2%) |

63 (71.6%) |

65 (67%) |

| BMI |

29±8 |

30±9 |

28±7 |

0.682 |

| ECOG Performance Status |

| 0 |

114 (62.3%) |

69 (80.2%) |

45 (46.4%) |

<0.001 |

| 1 |

51 (27.9%) |

13 (15.1%) |

38 (39.2%) |

| 2 |

12 (6.6%) |

3 (3.5%) |

9 (9.3%) |

| 3 |

6 (3.3%) |

1 (1.2%) |

5 (5.2%) |

| DM |

130 (70.3%) |

66 (75%) |

64 (66%) |

0.200 |

| Prior interventions |

| None |

118 (63.8%) |

55 (62.5%) |

63 (64.9%) |

0.011 |

| Ablation |

6 (3.2%) |

0 (0%) |

6 (6.2%) |

| Surgery |

2 (1.1%) |

0 (0%) |

2 (2.1%) |

| Systemic |

5 (2.7%) |

1 (1.1%) |

4 (4.1%) |

| TACE/TAE |

52 (28.1%) |

30 (34.1%) |

22 (22.7%) |

| TARE |

2 (1.1%) |

2 (2.3%) |

0 (0%) |

| Cirrhosis |

151 (81.6%) |

73 (83%) |

78 (80.4%) |

0.707 |

| Child score |

| A5 |

52 (28.1%) |

18 (20.5%) |

34 (35.1%) |

0.218 |

| A6 |

79 (42.7%) |

44 (50%) |

35 (36.1%) |

| B7 |

32 (17.3%) |

16 (18.2%) |

16 (16.5%) |

| B8 |

10 (5.4%) |

4 (4.5%) |

6 (6.2%) |

| B9 |

3 (1.6%) |

1 (1.1%) |

2 (2.1%) |

| C10 |

1 (0.5%) |

0 (0%) |

1 (1%) |

| Etiology of cirrhosis |

| Cryptogenic |

84 (45.4%) |

40 (45.5%) |

44 (45.4%) |

0.029 |

| Hemochromatosis |

1 (0.5%) |

1 (1.1%) |

0 (0%) |

| Hep B |

34 (18.4%) |

16 (18.2%) |

18 (18.6%) |

| Hep C |

50 (27%) |

28 (31.8%) |

22 (22.7%) |

| NASH |

15 (8.1%) |

2 (2.3%) |

13 (13.4%) |

| Schistosomiasis |

1 (0.5%) |

1 (1.1%) |

0 (0%) |

| BCLC stage |

| 0 |

20 (10.8%) |

15 (17%) |

5 (5.2%) |

0.091 |

| A |

56 (30.3%) |

23 (26.1%) |

33 (34%) |

| B |

64 (34.6%) |

31 (35.2%) |

33 (34%) |

| C |

42 (22.7%) |

18 (20.5%) |

24 (24.7%) |

| D |

3 (1.6%) |

1 (1.1%) |

2 (2.1%) |

| Extent of intrahepatic disease |

| Bilobar |

28 (15.5%) |

13 (15.5%) |

15 (15.5%) |

0.041 |

| Multifocal |

55 (30.4%) |

33 (39.3%) |

22 (22.7%) |

| Segmental |

43 (23.8%) |

20 (23.8%) |

23 (23.7%) |

| Unilobar |

55 (30.4%) |

18 (21.4%) |

37 (38.1%) |

| Replacement of liver by tumor |

| less than 25% |

128 (70.3%) |

55 (63.2%) |

73 (76.8%) |

0.184 |

| 25-50% |

36 (19.8%) |

21 (24.1%) |

15 (15.8%) |

| 50-75% |

16 (8.8%) |

10 (11.5%) |

6 (6.3%) |

| >75% |

2 (1.1%) |

1 (1.1%) |

1 (1.1%) |

| largest lesion size (cm) |

5.8±4 |

6.3±4 |

5.5±3.9 |

0.181 |

| Portal Vein Tumoral Thrombosis |

55 (30.6%) |

26 (30.6%) |

29 (30.5%) |

|

| PVTT 1 |

6 (3.2%) |

4 (4.5%) |

2 (2.1%) |

0.009 |

| PVTT 2 |

24 (13%) |

16 (18.2%) |

8 (8.2%) |

| PVTT 3 |

16 (8.6%) |

3 (3.4%) |

13 (13.4%) |

| PVTT 4 |

8 (4.3%) |

2 (2.3%) |

6 (6.2%) |

| Splenomegaly |

64 (34.6%) |

28 (31.8%) |

36 (37.1%) |

0.536 |

| Ascites |

36 (19.5%) |

16 (18.2%) |

20 (20.6%) |

0.713 |

| Varices |

40 (21.6%) |

16 (18.2%) |

24 (24.7%) |

0.290 |

| Whole liver volume |

1653.2±497 |

1654.2±487.3 |

1652.4±507.5 |

0.981 |

| Target perfused liver volume |

638.2±399.6 |

860±457.8 |

523.7±316.6 |

0.005 |

| Tumor volume |

283.2±399.1 |

284.7±321.5 |

282±454.9 |

0.965 |

| Y90 Dose |

1.6±0.8 |

1.7±0.7 |

1.4±0.8 |

0.006 |

| Target tumor dose |

141.2±58 |

146.5±47.9 |

137.4±64.2 |

0.333 |

| Treated lobe |

| Left |

31 (16.8%) |

11 (12.5%) |

20 (20.6%) |

0.165 |

| Rad segmentectomy |

12 (6.5%) |

3 (3.4%) |

9 (9.3%) |

| Right |

130 (70.3%) |

63 (71.6%) |

67 (69.1%) |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).