1. Introduction

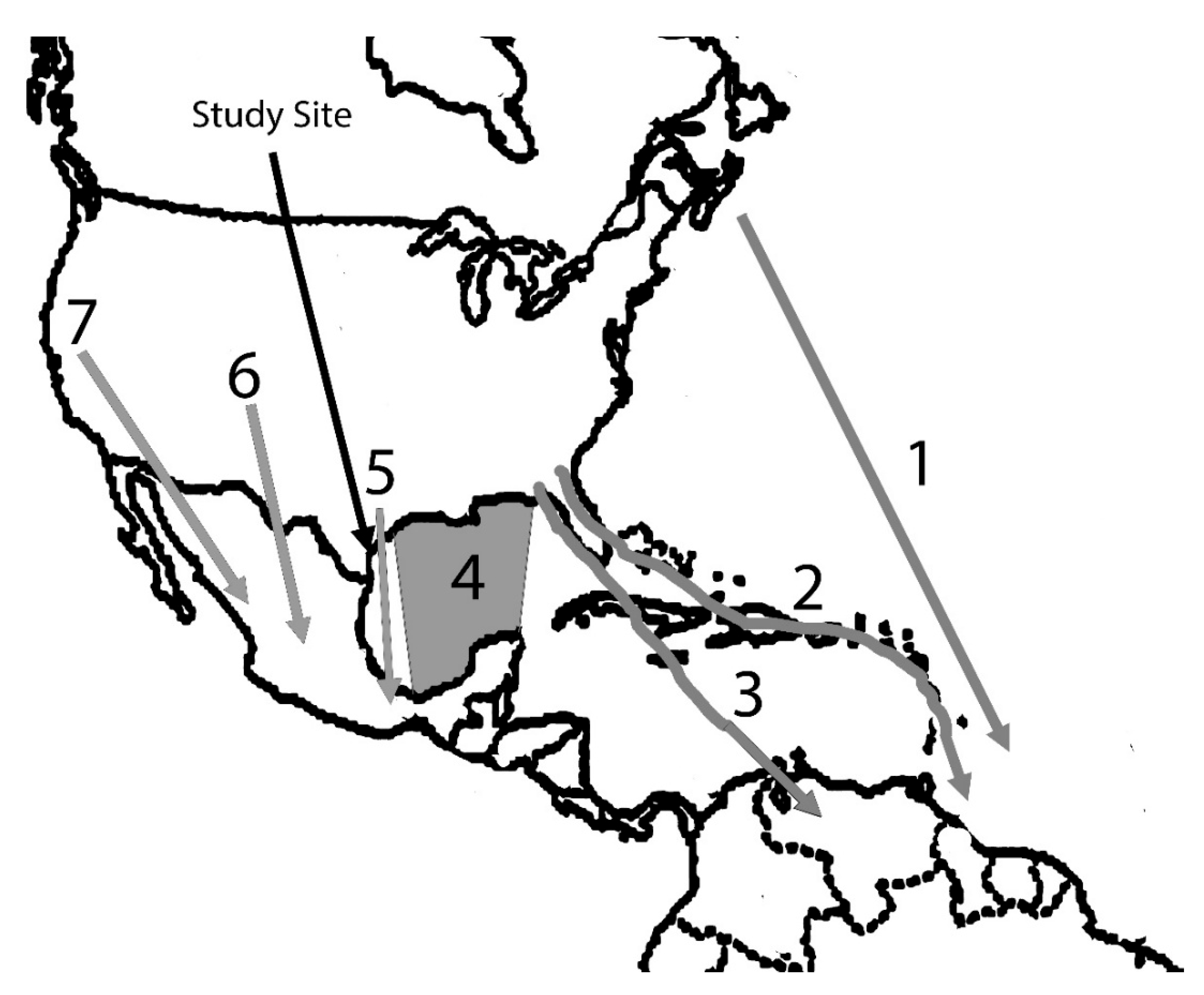

The idea that birds breeding in the Northern Hemisphere follow a particular path or route in moving from breeding areas in northern regions to wintering areas in the south was first developed for Western Hemisphere species in a publication by W. W. Cooke [

1] summarizing data from observations made by thousands of contributors from across the continent submitted to the U. S. Biological Survey over a period of 25 years.

Based on these data, Cooke depicted seven major migration routes (

Figure 1), all from the south-bound, fall perspective. Spring routes evidently were assumed to be the same in reverse (north-bound) for most species since those few known to follow a different route north from that followed south were discussed separately in Cooke’s publication.

The assumption that members of most migratory species follow the same route north as that followed south served as the principal basis for laboratory experiments on a European-African migrant, the Eurasian Blackcap (

Sylvia atricapilla). It has long been known that migrants held in cages during the migration period continually attempt to launch into flight, a behavior known as

Zugunruhe (frustrated movement) [

2,

3]. Researchers led by Peter Berthold studied

Zugunruhe in juvenile blackcaps from populations with different breeding and wintering areas and found that individuals from different breeding populations oriented their flight attempts in directions that appeared to coincide with the location of their different wintering areas, and that the duration of

Zugunruhe seemed to last for different numbers of days seemingly based on the different distances to their African wintering regions [

4].

These findings led to formulation of the “Migration Route” hypothesis which proposes that migratory birds are able to move between wintering and breeding areas for their species due to a genetic program for migration route that functions by providing instructions concerning the directions the bird must follow along the route and the period of time that it must follow each direction to arrive at the proper place. The same genetically-fixed program for route is followed in reverse north as that followed south for all members of the species regardless of sex or age [

5,

6].

This “Migration Route” hypothesis (also known as “clock-and-compass”, “bearing-and-distance”, or “vector”) serves as the basis for much related work on the phylogeny of migrants in which it is assumed that the migration route is a phylogenetic trait whose evolution dates back thousands of generations [

7,

8,

9,

10].

The Migration Route hypothesis also provides the basis for a considerable amount of current conservation activity focused on migrants, such as the National Audubon Society’s “Americas Flyways Initiative [

11]”, which warns that alteration of critical stopover areas by human activity or climate change can doom entire populations or even species because of migrant inability to change the genetic program for migration route required to reach their wintering areas in fall or their breeding areas in spring.

During the years 1973-1975 we conducted a study of migratory birds at the Welder Wildlife Refuge in South Texas. The main purpose of that study was to gather information on the behavioral ecology of migrants occurring as breeders in northern Minnesota, as transients in coastal Texas, and as wintering birds in southern Veracruz, Mexico [

12,

13,

14,

15]. As part of this process, we gathered an immense amount of ancillary data on fall and spring capture rates for 62 species of passerines that were known to occur along the Texas Central Coast solely as seasonal transients (neither breeding nor wintering in the region) [

16].

Herein we examine that capture information to address the question of a fixed migration route for migrants, and find that our data do not support a Migration Route hypothesis. We consider our data in light of those collected through the crowd-source database, eBird [

17], and on the movement of transient individual migrants gathered using new technologies and conclude that a new hypothesis is required to explain how migrants are able to orient properly in moving between breeding and wintering areas.

2. Study Area

The research was done at the Welder Wildlife Refuge in an 11.4 ha riparian forest bordering the Aransas River, 10 km inland from the immediate coast and 48 km north of Corpus Christi, Texas (

Figure 1). Forest canopy height is 10-15 meters. Dominant species include hackberry (

Celtis sp.), cedar elm (

Ulmus crassifolia), anacua (

Ehretia anaqua), pecan (

Carya illinoensis), and mustang grape (

Vitis mustangensis).

3. Materials and Methods

Nylon mist nets (12 x 2.6 m with 30 mm mesh) were set in five sectors of 10 nets each along a band of forest bordering one km of the western bank of the river. The nets were run during four seasons: fall, 1973 (15 August – 21 October); spring, 1974 (4 March – 24 May); fall, 1974 (20 August – 13 November); spring, 1975 (29 March – 28 May). Data recorded for each bird captured included: date, time, net number, species, mass, sex and age (where possible), molt, and subcutaneous fat. The bird was then provided with a numbered U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service aluminum band and released. Individuals of some species were saved as specimens for additional analysis, such as identification to subspecies, age, or sex where that was not possible for the bird in hand. These specimens are currently housed at the University of Minnesota Bell Museum of Natural History.

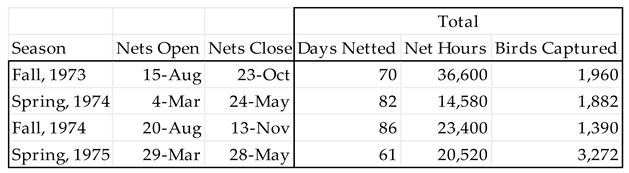

4. Results

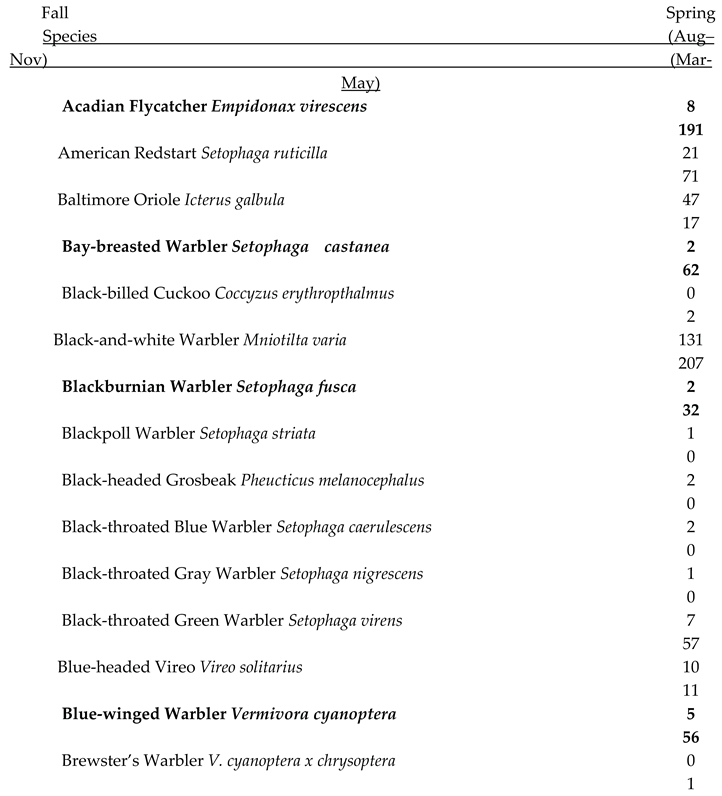

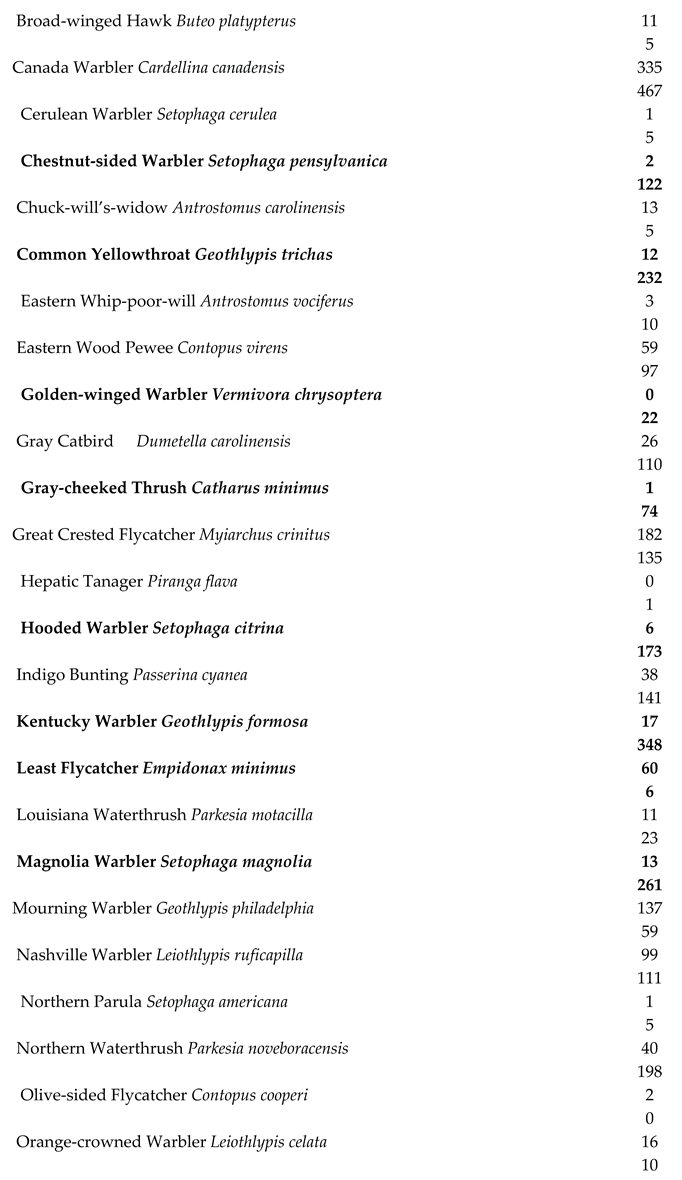

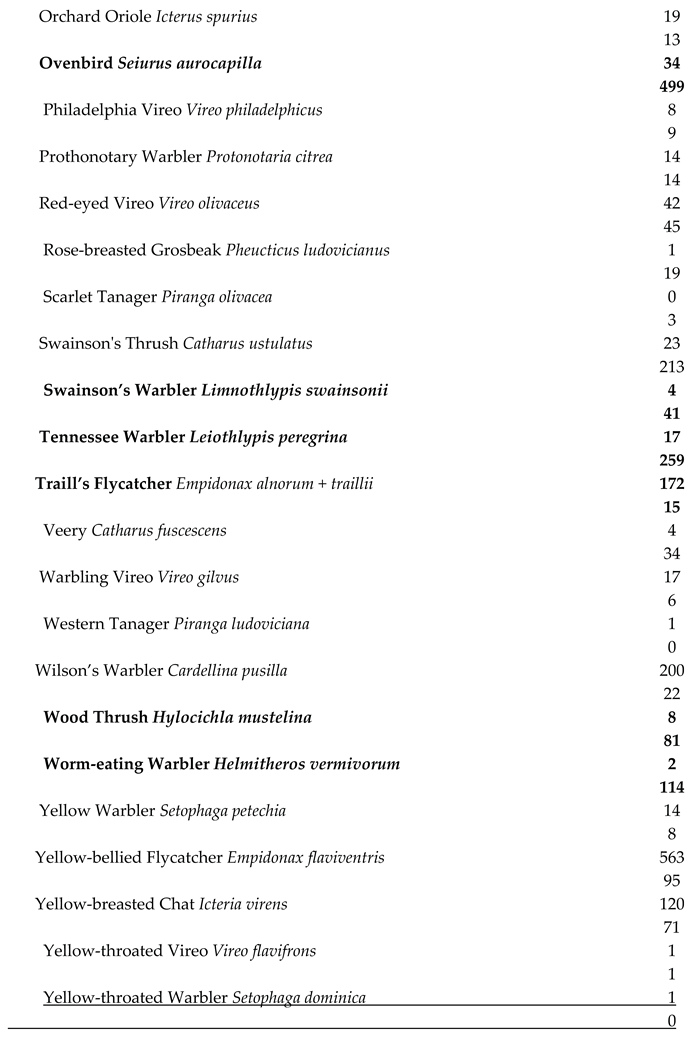

We captured 8,504 birds of 98 species over the four seasons from fall, 1974 through spring, 1975 (

Table 1).

Sixty-two species occurred only as transients. Capture data for these species are presented in

Table 2.

For 16 species, the number of individuals captured in spring was an order of magnitude or more greater than the number captured in fall. An additional 10 species demonstrate a similar westward shift in migration route between fall and spring although not to the extreme demonstrated by the 16 species.

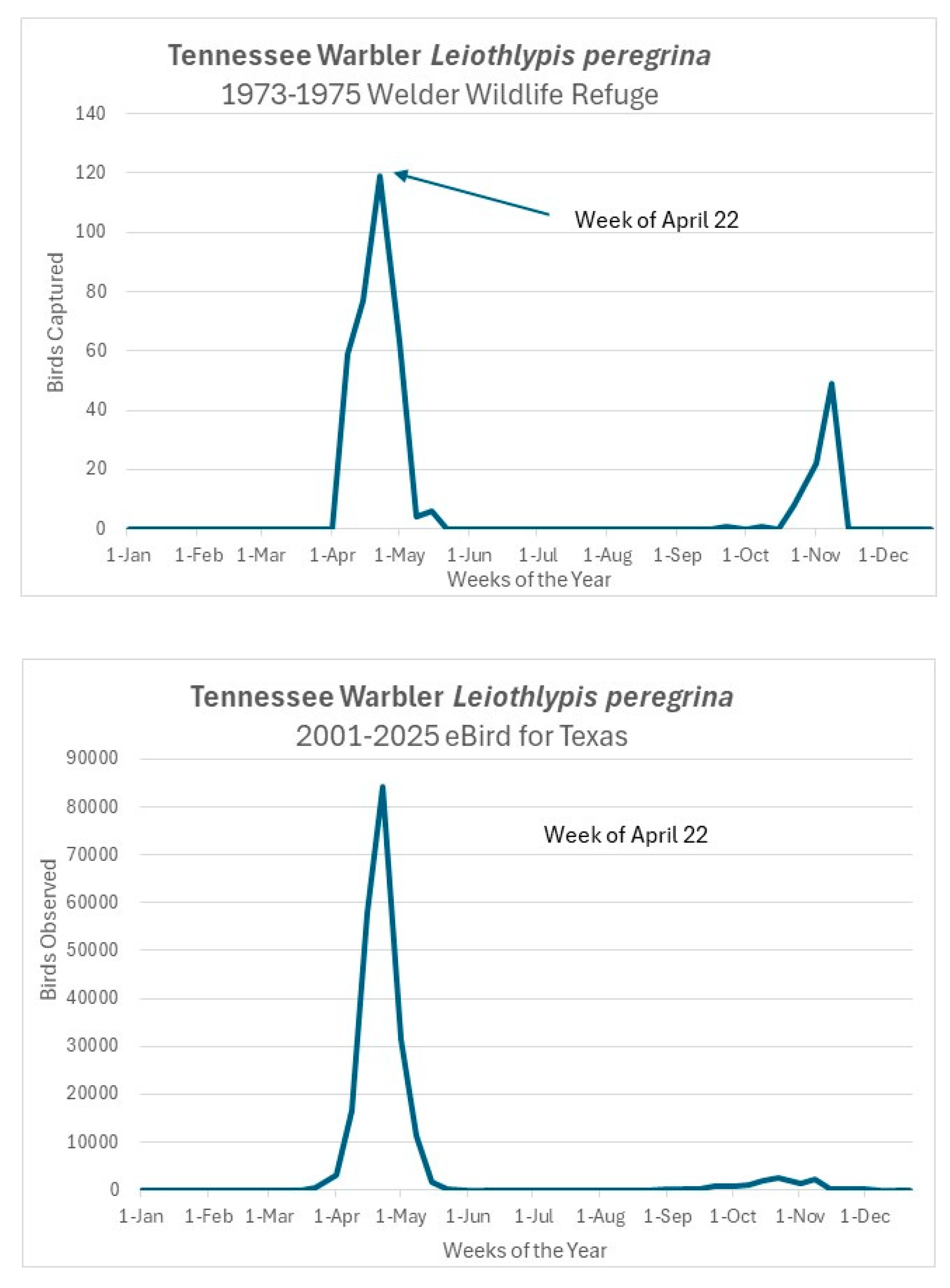

Data based on eBird [

17] sightings from Texas for those species more abundant in spring than in fall corroborate this pattern as exemplified in

Figure 2, which shows a graph of our capture data by week for the Tennessee Warbler (

Leiothlypis peregrina) as compared with a summary of eBird sightings graphed in a similar fashion for the same species over the past 25 years.

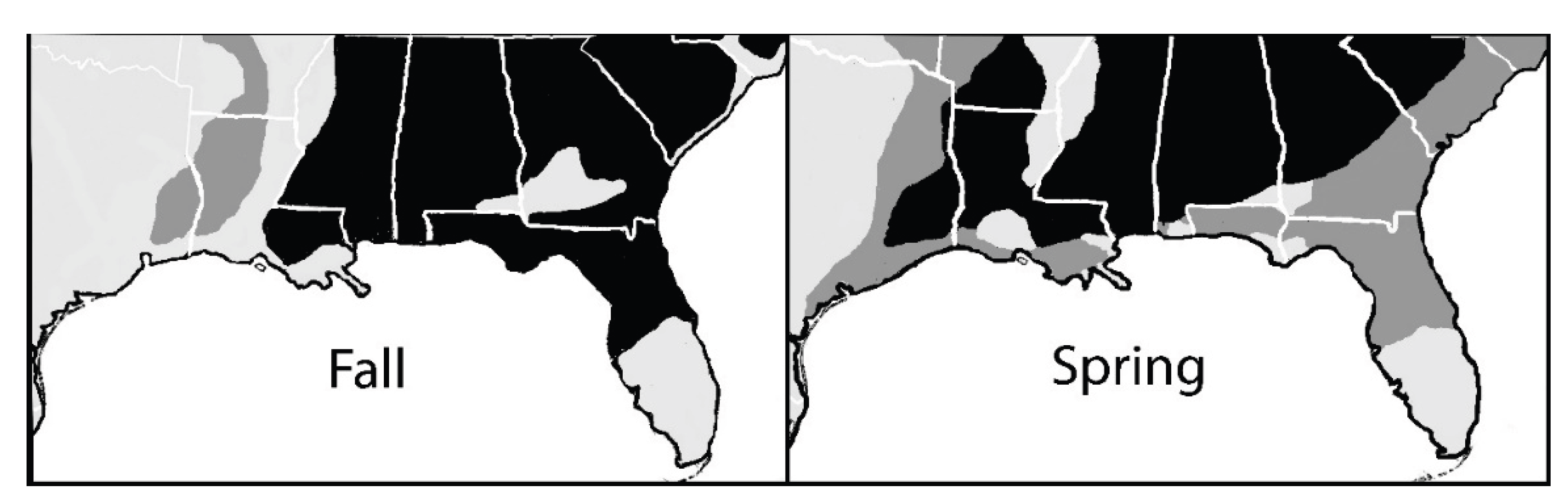

In addition, when eBird sighting data from the entire Gulf region for those birds more common in the western Gulf in spring are compared for fall and spring, it can be seen that the pattern for the eastern Gulf is reversed when compared with the western Gulf, i.e., there are fewer sightings in spring in the eastern Gulf region than in fall (

Figure 3).

5. Discussion

Our data for members of species captured as transients during spring and fall migration at a site near the Texas coast of the western Gulf of Mexico demonstrate conclusively that millions of individuals of several species follow a different route north to their breeding grounds from that followed south to their wintering grounds, findings corroborated by eBird observations for many of the same species from along the Texas coast as well as by eBird maps summarizing fall and spring migration from across the entire Gulf region. Both our data and that derived from eBird document a westward shift in the spring migration route as compared with the fall migration route for large segments of populations for many of the migratory species that breed in eastern North America.

These findings are not a surprise. The extreme differences in fall versus spring numbers along the Texas coast for many transient species has been known for a century or more, and documented prominently in papers by George Williams [

18,

19,

20,

21], and, of course, by thousands of observers since, a practice now systematized by the crowd-source on-line data summaries maintained by eBird [

17].

Our finding that adults and juveniles of the same migratory species follow different routes and timing, as exemplified by our Yellow-bellied Flycatcher (

Empidonax flaviventris) data, also is not a surprise. Reviews in Rappole [

22,

23,

24] summarize extensive documentation of this phenomenon for many species, including most famously, the Blackpoll Warbler (

Setophaga striata) in which the majority of adults take off from the New England coast heading directly over the western North Atlantic toward their South American wintering grounds whereas most juveniles move south along the coastline of the eastern U.S. [

25]. In addition, there are many species in which the majority of males and females or adults and juveniles of a migratory species follow different schedules and/or winter in different regions [

23,

26].

Clearly, a genetically-based program for migration direction and distance does not explain these findings. Video summaries available from eBird of sighting distributions from throughout the year for many migratory species make this astoundingly obvious. Herein we provide a link to one such video, that for the Tennessee Warbler (Leiothlypis peregrina) Tennessee Warbler - Weekly Abundance Map - eBird Status and Trends. This video shows a breeding distribution during the months from May - August for this bird that extends across the boreal forest regions of the entire North American continent. Then as the fall migration progresses through September and October, birds from the eastern portion of the range head more or less directly southward across the eastern U.S. and crossing the eastern Gulf of Mexico en route to wintering grounds in the tropical forests of Central America. However, birds from the western portion of the range head eastward for thousands of kilometers, avoiding (or flying over) the tree-less expanses of the Great Plains, before joining eastern portions of the population in southward migration across the eastern Gulf. The pattern for northbound birds leaving Central America in April and May shows a sharp western shift of several hundred kilometers for the entire wintering population. Obviously, no genetic program for migration direction and duration in Tennessee Warblers can explain this dynamic.

The eBird [

17] data are based on old technology, indeed, the same as used by Cooke in his 1915 paper [

1], namely summarizing the reports of thousands of amateur field biologists. What eBird has added is a vast expansion of the number of observers along with extraordinary algorithms for collection and online display of data. This new methodology makes population movement visible in almost real time. Nevertheless, it does not greatly expand our knowledge of movement of individuals.

Banding studies supplemented by extensive field observation have been extremely helpful in this regard, demonstrating the individual nature of the migration decision based on age, sex, and local conditions such as for the Song Sparrows (

Melospiza melodia) [

27], Eurasian Robin (

Erithacus rubecula) [

28], Prairie Warblers (

Setophaga discolor) [

29]. In addition, intensive, long-term studies at a single site can provide insight into the individual nature of migratory movement [

30]. However, it is new technologies that appear poised to fully elucidate the individual nature of migration, e.g. radio tracking and data loggers [

31,

32,

33,

34].

Despite extensive evidence alluded to above for the individual nature of migration, the “Migratory Route” hypothesis has been widely accepted as fact. A major reason for this may lie in its apparent explanatory power for certain genetically-based findings. For instance, experiments showing that offspring from parents from populations with different wintering areas display

Zugunruhe directions intermediate between the two [

35] clearly demonstrate the genetic nature of migratory travel. However, attributing this behavior to a migration route program is not warranted. The behavior can as easily be attributed to inheritance of knowledge of the wintering area location in the offspring, in which case following a migratory direction intermediate to the different wintering areas of the parents could be interpreted as resulting from confusion as to which wintering area to go to rather than which migratory route to follow.

Similar genetic arguments in support of the Migration Route program have been put forward by Brelsford and Irwin [

10] who argue that the reason hybrids between members of populations of a species with different migration routes are apparently unsuccessful (assumed because known interbreeding has not subsumed population differences) is that the traits governing migration route might be inappropriate, resulting in low fitness for hybrids. However, reduced fitness for hybrids could easily result from confusion over which wintering area location to choose as over which migratory route to follow.

6. Conclusions

Our findings make clear that a migratory bird’s travel to, and return from, the appropriate wintering area for its species cannot be explained by the Migration Route hypothesis. We suggest that it is knowledge of the location of the breeding and/or wintering area for the species that is passed between generations that explains how this is accomplished, an idea that we term the “Destination” hypothesis. This theory is supported by field data on migrants of many different taxonomic groups in addition to birds (e.g., bats, turtles, fish, and insects) [

23]. How this information is exchanged is unknown at present, but evidence of its existence is extensive, most strikingly perhaps in the Monarch Butterfly (

Danaus plexippus) in which movement between breeding and wintering areas is accomplished by members of different generations [

36].

Regardless of how travel between wintering and breeding areas is accomplished, it is obvious that most migratory birds of most species do not follow the same route north as that followed south. In fact, data gathered from the field augmented by new technologies, as discussed above, demonstrate that each individual follows its own path that will differ from one journey to the next based on its own situation including species, location, sex, age, experience, and its immediate environment.

Funding

This research was funded by the Welder Wildlife Foundation, P.O. Box 1400, Sinton, Texas through a doctoral fellowship grant to John H. Rappole.

Data Availability Statement

The original data are contained in catalogs in the possession of the senior author. All capture data were extracted and summarized in spreadsheet format for the purposes of this paper and saved in files entitled “Welder Netting Data 1973-1975” copies of which are available on request from the senior author.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Welder Wildlife Foundation for financial support particularly Director Dr. Clarence Cottam, Assistant Directors Caleb Glazener and Eric Bolen, and the trustees. We thank George Jonkel, Brian Sharpe, and Jay Sheppard of the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Bird-Banding Laboratory, R. A. Hodgins and Wayne Adams of U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Bureau of Enforcement, and William Sheffield and Robert Misso of the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department for the permits necessary to complete the study. Field assistance was provided by Gene Blacklock, Christopher P. Barkan, Robert Zink, Bruce Fall, Rebecca Bolen, Karilyn Mock, Howard Galloway, Douglas Mock, and Joe Folse.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cooke, W. W. 1915. Bird Migration. U. S. Department of Agriculture, Washington, D.C.

- Groebbels, F. Zur Physiologie der Vogelzuges. Verh. Ornithol. Ges. Bayern 18:44-74.

- Kramer, G. 1952. Experiments on bird orientation. Ibis 94:265-285.

- Berthold, P. 1988. The control of migration in European warblers. Proceedings of the International Ornithological Congress 19:215-249.

- Berthold, P. 1996. Control of Bird Migration. Chapman and Hall, London.

- Pulido, F. 2007. The genetics and evolution of bird migration. BioScience 57:165-174.

- Baker, A. J. 2002. The deep roots of bird migration: Inferences from the historical record preserved in DNA. Ardea 90:503-513.

- Ruegg, K. C. , and T. B. Smith. 2002. Not as the crow flies: A historical explanation for circuitous migration in Swainson’s Thrush (Catharus ustulatus). Proceedings of the Royal Society B 269:1375-1381.

- Irwin, D. E. , and J. H. Irwin. 2005. Siberian migratory divides – the role of seasonal migration in speciation. Pp. 27-40 in Birds of Two Worlds (R. Greenberg a d P. Marra, eds.). Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore.

- Brelsford, A. , and D. E. Irwin. 2009. Incipient speciation despite little assortative mating: The Yellow-rumped Warbler hybrid zone. Evolution 63:3050-3060.

- National Audubon Society. 2022. Americas Flyways Initiative.

- Rappole, J. H. 1974. Migrants and space: The wintering ground as a limiting factor for migrant populations. Bulletin of the Texas Ornithological Society 7:2-4.

- Rappole, J. H., D. W. Warner, and M. A. Ramos. 1977. Territoriality and population structure in a small passerine community. Amer. Midl. Natur. 97:110-119.

- Rappole, J. H. , and D. W. Warner. 1978. Migrant population ecology: relevance to conservation theory. Trans. N. Amer. Wildl. Nat. Resour. Conf. 43:235-240.

- Rappole, J. H. , and D. W. Warner. 1980. Ecological aspects of avian migrant behavior in Veracruz, Mexico. Pp. 353-394 In Migrant birds in the Neotropics: ecology, behavior, conservation, and distribution (A. Keast & E.S. Morton, Eds.), Smithsonian Inst. Press, Washington, D.C.

- Oberholser, H. C. 1974. The Bird Life of Texas. University of Texas Press, Austin.

- eBird; https://ebird.org. Jun2, 11, 2025; Sullivan, B.L., C.L. Wood, M.J. Iliff, R.E. Bonney, D. Fink, and S. Kelling. 2009. eBird: a citizen-based bird observation network in the biological sciences. Biological Conservation 142: 2282-2292.

- Williams, G. G. 1945. Do birds cross the Gulf of Mexico in spring? Auk 62:98–111.

- Williams, G. G. 1947. Lowery on trans-Gulf migration. Auk 64:217–238.

- Williams, G. G. 1950. The nature and causes of the coastal hiatus. Wilson Bulletin 62:175–182.

- Williams, G. G. 1951. Letter to the editor. Wilson Bulletin 63:52–54.

- Rappole, J. H. 1995. The ecology of migrant birds: A Neotropical perspective. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, DC.

- Rappole, J. H. 2013. The Avian Migrant. Columbia University Press. New York.

- Rappole, J. H. 2022. Bird Migration: A New Understanding. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore.

- Nisbet, I. C. T., W. H. Drury, Jr., and J. Baird. 1963. Weight loss during migration. Part 1. Deposition and consumption of fat by the Blackpoll Warbler (Dendroica striata). Bird-Banding 34:107–138.

- Helm, B. 2006. Zugunruhe, 5: and non-migratory birds in circannual context. Journal of Avian Biology 37.

- Nice, M. M. 1937. Studies in the life history of the Song Sparrow. Volume 1. Transactions of the Linnean Society of New York 37.

- Lack, D. L. 1943. The life of the robin. Witherby, London.

- Nolan, V., Jr. 1978. The ecology and behavior of the Prairie Warbler Dendroica discolor. Ornithological Monographs 26. American Ornithologists’ Union, Washington, DC.

- Berry, James M. and Rappole, John Sr. (2023) "Seasonal Change in the Avian Community of a Western New York Shrub Swamp," North American Bird Bander: Vol. 48 : Iss. 4, Article 2. Available at: https://digitalcommons.usf.

- Stutchbury, B. J. M., S. A. Tarof, T. Done, E. A. Gow, P. M. Kramer, J. Tautin, J. W. Fox, and V. Afanasyev. 2009. Tracking long-distance songbird migration by using geolocators. Science 323:896.

- British Trust for Ornithology. 2011a. Tracking cuckoos into Africa. http://www.bto.org/science/ migration/tracking-studies/cuckoo-tracking Accessed. 7 February.

- British Trust for Ornithology. 2011b. Tracking nightingales into Africa. http://www.bto.org/ science/migration/tracking-studies/nightingale-tracking Accessed. 7 February.

- Hewson, C. M., K. Thorup, J. W. Pearce-Higgins, and P. W. Atkinson. 2016. Population decline is linked to migration route in the Common Cuckoo. [CrossRef]

- Helbig, A. J. 1996. Genetic basis, mode of inheritance and evolutionary changes of migratory directions in Palearctic warblers (Aves: Sylviidae). Journal of Experimental Biology 199:49-55.

- Brower, L. P. 1995. Understanding and misunderstanding the migration of the monarch butterfly (Nymphalidae) in North America: 1857–1995. Journal of the Lepidopterists Society 49:304–385.

- Rappole, J. H. 2024. Migration Mysteries. Texas A&M University Press, College Station, Texas.

- Helbig, A. J. 2003. Evolution of bird migration: A phylogenetic and biogeographic perspective. Pp. 3-21 In Avian Migration (P. Berthold, E. Gwinner, and E. Sonnenschein, eds.) Springer-Verlag, Heidelberg.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).