KEY MESSAGES

What is already known on this topic

Adult granulosa cell tumors have an indolent course but lack well-established prognostic indicators.

What this study adds

Advanced-stage (FIGO stage III) disease independently predicts recurrence.

How this study might affect research, practice or policy

Supports tailored long-term surveillance strategies based on tumor stage and endometrial pathology.

1. Introduction

Adult granulosa cell tumors are uncommon ovarian malignancies originating from the sex cord-stromal cells of the ovary, accounting for approximately 2–5% of all ovarian cancers [

1]. They are typically diagnosed in perimenopausal or postmenopausal women, although younger patients may also be affected [

2].

These tumors generally exhibit indolent behavior, and prognosis is favorable in most early-stage cases. However, their potential for late recurrence (even decades after initial treatment) necessitates prolonged follow-up [

2]. While 5-year survival rates often exceed 90% in early-stage disease, relapse significantly compromises long-term outcomes [

3].

Surgical resection remains the cornerstone of management, although the role of comprehensive staging, including lymphadenectomy, is debated due to the low incidence of nodal metastasis [

4]. The benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy is also uncertain, particularly in early-stage disease, as high-quality supporting evidence is lacking. Regimens such as bleomycin-etoposide-cisplatin, etoposide-cisplatin, and carboplatin-paclitaxel have been used in both adjuvant and recurrent settings; however, their impact on long-term outcomes remains unclear [

5].

Molecularly, over 90% of adult granulosa cell tumors harbor the somatic FOXL2 c.402C>G (p.C134W) mutation, a highly specific diagnostic biomarker [

6]. Serum markers such as Anti-Müllerian hormone and inhibin B demonstrate diagnostic utility (particularly for recurrence surveillance) although their prognostic significance is less well defined [

7]. Numerous clinicopathological features, including tumor stage, size, mitotic index, residual disease, and endometrial pathology, have been proposed as prognostic indicators [

8]. However, inconsistencies across retrospective studies have limited consensus on their predictive value. In particular, the prognostic relevance of tumor size, adjuvant chemotherapy, and endometrial pathology warrants further investigation.

In this retrospective single-center study, we aimed to evaluate the clinicopathological characteristics, treatment patterns, and long-term outcomes of patients with adult granulosa cell tumors, with a primary focus on disease-free survival. Specifically, we examined the impact of tumor size, mitotic index, FIGO stage, estrogen receptor status, endometrial pathology, and adjuvant treatment regimen on recurrence risk and disease-free survival.

2. Methods

This retrospective cohort study included female patients with histopathologically confirmed adult granulosa cell tumors who were treated and/or followed at the Department of Medical Oncology, Ege University Faculty of Medicine, between January 2012 and 2023. Clinical and pathological data were obtained from electronic hospital records and patient files. Collected variables included age at diagnosis, menopausal status, parity, presenting symptoms, type of surgery, adjuvant treatment status and regimen, recurrence status, and duration of follow-up. Pathological parameters included tumor size, tumor location, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage, mitotic index, endometrial pathology, estrogen receptor status, and inhibin expression. According to current standards in gynecologic oncology, the 2014 FIGO staging system, which remains the most widely adopted and clinically relevant classification for ovarian, fallopian tube, and primary peritoneal cancers, is used in this study [

9].

For statistical analysis, certain continuous variables were categorized to facilitate survival comparisons. Age at diagnosis was grouped as ≤65 years and >65 years; menopausal status as pre-menopausal vs. peri/post-menopausal; tumor size as ≤10 cm and >10 cm; and mitotic index as ≤4 and >4 mitoses per 10 high-power fields (HPF). FIGO stage was classified as early stage (Stage I–II) and advanced stage (Stage III), while parity was categorized as ≤2 and ≥3. Endometrial pathology was classified into three categories: none, non-atypical hyperplasia, atypical hyperplasia, and carcinoma. These categorical groupings were used in Kaplan–Meier survival analyses and multivariable regression models.

Disease-free survival was defined as the time from initial surgery to the date of recurrence or last disease-free follow-up. Overall survival was defined as the time from initial surgery to death from any cause or last known follow-up. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize patient demographics and clinicopathological characteristics. Continuous variables such as age were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and median with interquartile range (IQR). Categorical variables were reported as frequencies and percentages. Survival distributions were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and compared across subgroups using the log-rank test. Five-year disease-free survival and overall survival rates were derived from Kaplan-Meier survival curves.

Associations between recurrence status and clinicopathological variables were evaluated using the Pearson chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test where appropriate. For survival analyses, both univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression models were performed to identify factors associated with disease-free survival. Variables with a p-value < 0.10 in univariate analysis were included in the multivariate model. Hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and corresponding p-values were reported. Forest plots were generated to visually represent the results of the multivariate Cox regression analysis. Due to the limited number of death events (n = 5), multivariate regression analysis for overall survival could not be reliably performed and was therefore omitted.

All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). A two-tailed p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Clinical data were updated before final analysis in July 2025 to ensure the most accurate representation of survival and recurrence outcomes.

This retrospective study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Ege University Faculty of Medicine (Decision No: 25-3.1T/64, Date: March 20, 2025), and was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

3. Results

A total of 55 patients diagnosed with adult granulosa cell tumors were included in the analysis. The mean age at diagnosis was 50.1 ± 14.9 years, and the median age was 52 years (IQR: 41–60). The median disease-free survival was 92.3 months, and the median overall survival was 113.7 months. Among patients who experienced recurrence, the mean time to relapse was 58.4 months. The estimated 5-year disease-free survival was 84.5% (95% CI: 74.5–94.5%), and the 5-year overall survival was 93.9% (95% CI: 87.2–100.0%).

The majority of patients were postmenopausal (52.7%), and 45.5% had no comorbidities. Recurrence was observed in 23.6% of patients, most commonly in the peritoneum (10.9%). Regarding associated endometrial pathology, 30.9% had non-atypical endometrial hyperplasia. There was a statistically significant association between menopausal status and endometrial pathology (p = 0.002). Among premenopausal patients, 17 had no endometrial pathology, 3 had non-atypical hyperplasia, and 1 had atypical hyperplasia or carcinoma. Among peri/postmenopausal patients, 11 had no endometrial pathology, 14 had non-atypical hyperplasia, and 9 had atypical hyperplasia or carcinoma. Estrogen receptor was positive in 32.7%, while 49.1% of the cohort had unknown estrogen receptor status. Inhibin expression was positive in 83.6% of cases.

Adjuvant chemotherapy was administered to 38.2% of patients, most commonly with bleomycin-etoposide-cisplatin or etoposide-cisplatin regimens. A fertility-sparing surgical approach was rarely used; the majority underwent primary staging surgery (92.7%). Tumors were most frequently located in the left ovary (54.5%), and measured ≤10 cm in 63.6% of cases. Most patients were diagnosed at an early stage (Stage I: 89.1%), and 65.5% had a mitotic index >4 per 10 HPF. The mean and median follow-up durations were 108.4 and 113.7 months, respectively. At the time of analysis, 90.9% of the patients were alive. A detailed distribution of clinicopathological features is provided in

Table 1.

Chi-square tests were performed to evaluate the relationship between recurrence and clinicopathological variables. Recurrence was significantly associated with endometrial pathology (p = 0.025), adjuvant chemotherapy type (p = 0.008), and disease stage (p = 0.045). Recurrence was more frequent in patients with atypical endometrial changes (atypical hyperplasia or carcinoma), those who received bleomycin-etoposide-cisplatin or etoposide-cisplatin chemotherapy, and those diagnosed at stage III, suggesting a link between high-risk pathological or clinical features and relapse. In contrast, age group, menopausal status, tumor size, mitotic index, Ki-67 index, estrogen receptor status, and inhibin expression were not significantly associated with recurrence (all p > 0.05) (

Table 2).

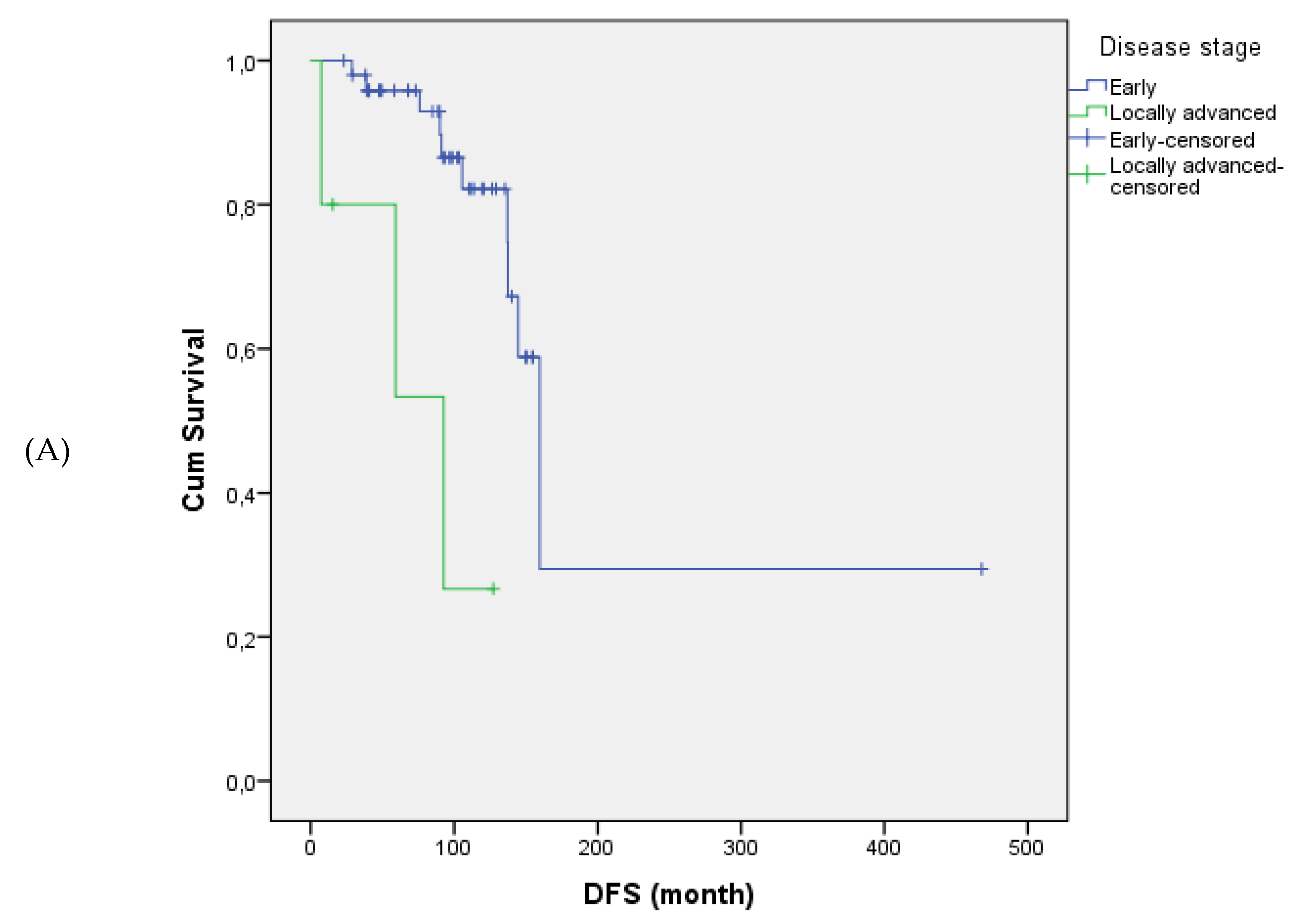

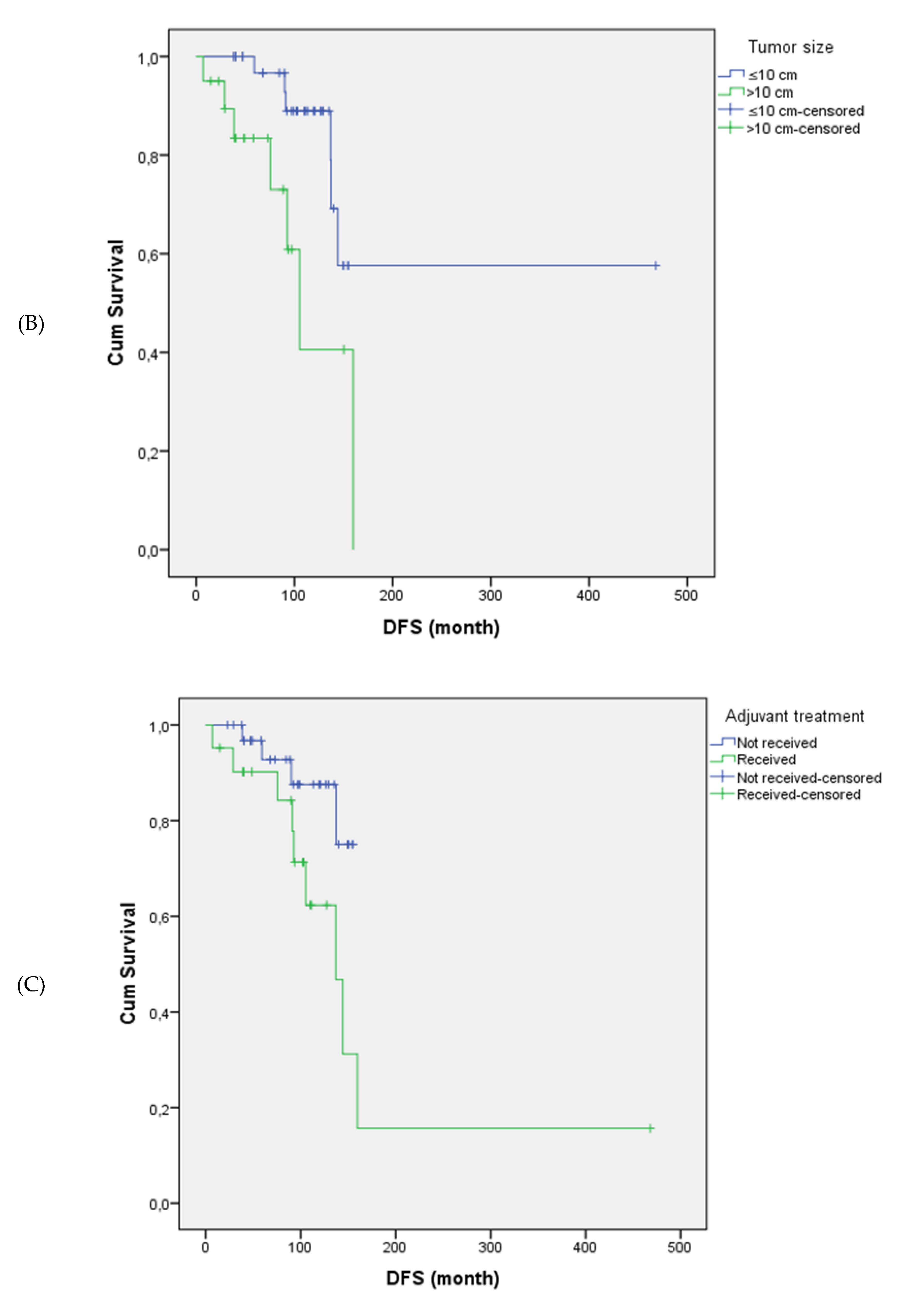

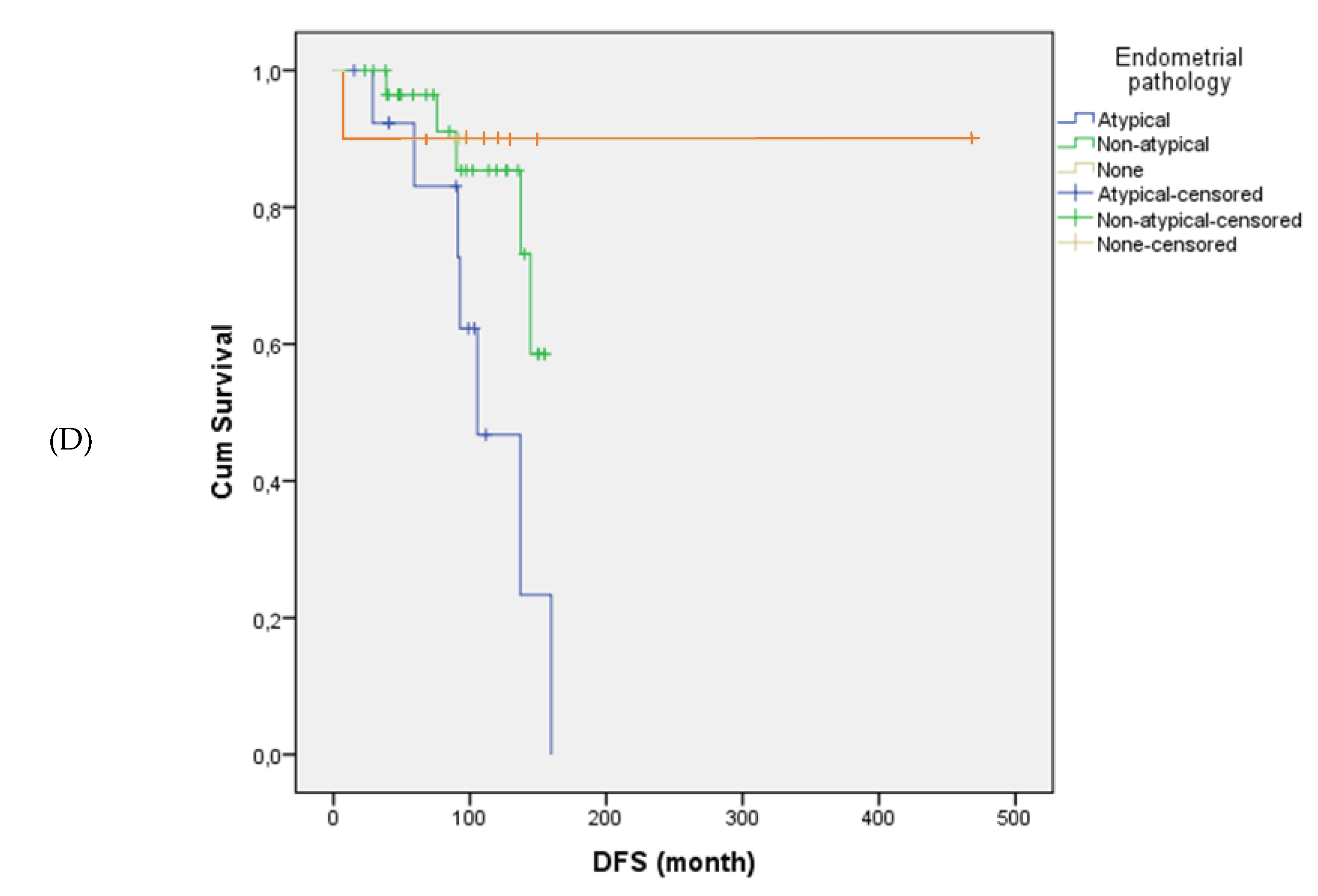

Tumor size and stage were significantly associated with disease-free survival. Patients with tumors >10 cm had significantly shorter disease-free survival compared to those with tumors ≤10 cm (mean: 109.7 vs. 322.5 months, p = 0.017). Disease-free survival was also significantly shorter in patients with locally advanced-stage disease (Stage III) compared to those diagnosed at earlier stages (Stage I–II) (p = 0.001). Similarly, the presence and type of endometrial pathology significantly impacted disease-free survival (p = 0.033); patients with atypical hyperplasia had the poorest outcomes, whereas those without any endometrial pathology showed the most favorable disease-free survival.

The mean disease-free survival was 169.4 months in the adjuvant chemotherapy group and 141.9 months in the non-adjuvant group (p = 0.045). Disease-free survival differed significantly according to adjuvant treatment type (p = 0.003). Among patients who received adjuvant chemotherapy, disease-free survival durations varied by regimen. However, no direct statistical comparison between adjuvant chemotherapy regimens was performed due to small subgroup sizes and limited recurrence events. Other clinicopathological variables, including mitotic index, Ki-67 expression, estrogen receptor status, tumor laterality, parity, inhibin status, and presence of comorbidities, were not significantly associated with disease-free survival (all p > 0.05).

Figure 1 illustrates the differences in disease-free survival according to stage, tumor size, adjuvant therapy, and endometrial pathology.

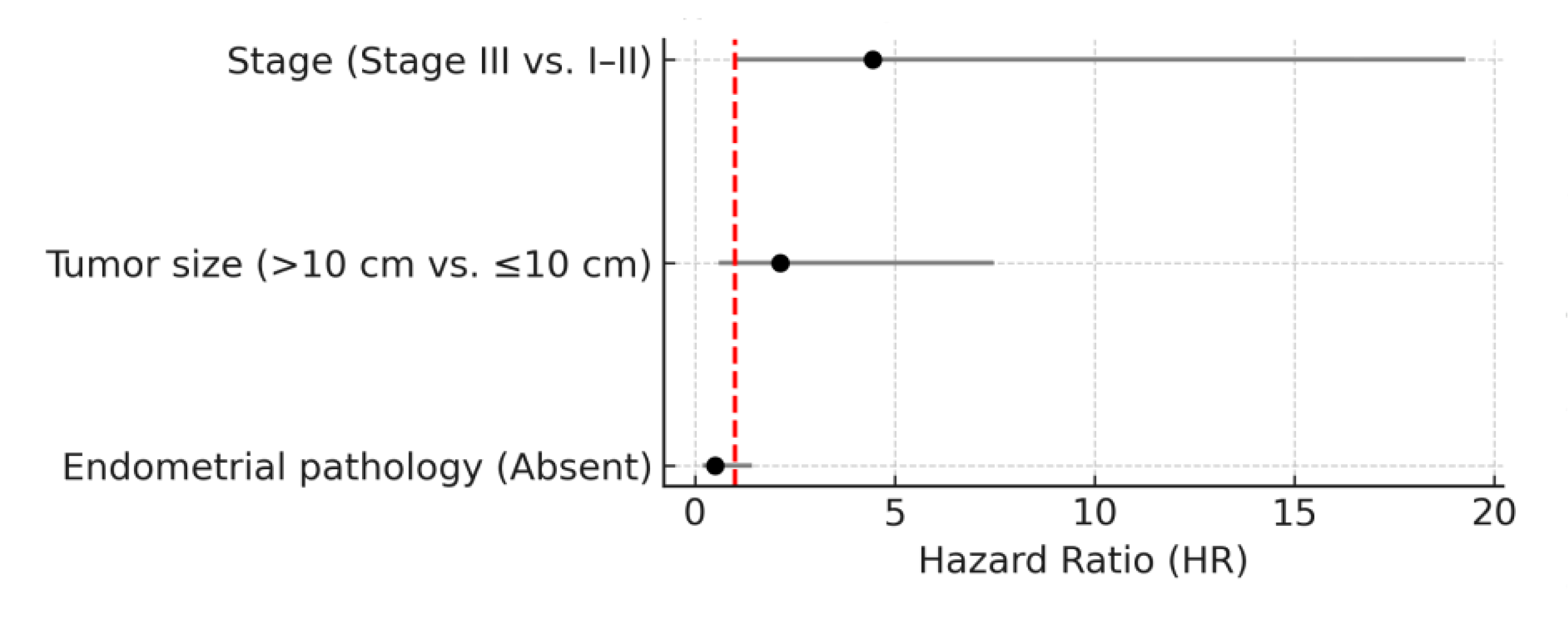

In univariate Cox regression analysis, several variables were significantly associated with disease-free survival. Patients with Stage III disease had significantly poorer disease-free survival compared to those with Stage I–II disease (HR: 7.14; 95% CI: 1.78–28.73; p = 0.006). Tumor size >10 cm was also associated with worse disease-free survival (HR: 3.59; 95% CI: 1.18–10.95; p = 0.025). The absence of endometrial pathology was associated with improved disease-free survival (HR: 0.343; 95% CI: 0.138–0.858; p = 0.022). Adjuvant chemotherapy showed a trend toward shorter disease-free survival (HR: 3.21; 95% CI: 0.96–10.69; p = 0.058), although this did not reach statistical significance.

In multivariate Cox regression analysis, advanced-stage disease (Stage III) remained an independent predictor of shorter disease-free survival (HR: 4.45; 95% CI: 1.03–19.27; p = 0.046). Tumor size >10 cm (HR: 2.13; p = 0.241) and endometrial pathology (HR: 0.51; p = 0.197) did not retain statistical significance in the multivariate model. Although adjuvant treatment (bleomycin-etoposide-cisplatin or etoposide-cisplatin / carboplatin-paclitaxel) was included in the multivariate model due to its p-value < 0.10 in univariate analysis, it did not demonstrate a statistically significant association with disease-free survival (p = 0.537) and was not retained in the final multivariate model. The results of univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses for disease-free survival are presented in

Table 3 and illustrated as a forest plot in

Figure 2.

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Main Results

This study provides a comprehensive assessment of recurrence and disease-free survival in adult granulosa cell tumors. In our cohort of adult granulosa cell tumor patients, FIGO stage III disease was an independent predictor of shorter disease-free survival (HR: 4.45; p = 0.046). While tumor size >10 cm was significant in univariate analysis, it did not retain significance in multivariate models. Patients who received adjuvant chemotherapy also had shorter disease-free survival, although this may reflect treatment selection for higher-risk cases. The median disease-free and overall survival were 92.3 and 113.7 months, respectively. The 5-year disease-free survival rate was 84.5% (95% CI: 74.5–94.5%) and the 5-year overall survival rate was 93.9% (95% CI: 87.2–100.0%). The recurrence rate was 23.6%. Multivariate analysis for overall survival was not feasible due to the limited number of deaths (n = 5).

4.2. Results in the Context of Published Literature

These findings are consistent with previous reports from multiple large-scale cohorts [

10,

11]. The Helsinki cohort further supports the unpredictable recurrence pattern of adult granulosa cell tumors reporting a median time to relapse of 89 months and frequent asymptomatic presentations. While tumor rupture was the only independent predictor of recurrence in that study, we identified advanced FIGO stage as the strongest prognostic factor [

2]. Multiple retrospective studies have confirmed that advanced FIGO stage (beyond IA) is linked to shorter disease-free and overall survival in adult granulosa cell tumors, highlighting the prognostic importance of tumor stage at diagnosis across different populations [

12,

13,

14].

In a cohort of 61 adult granulosa cell tumor patients, the recurrence rate was 26%, with a median time to relapse of 5.5 years. Reported 5-year disease-free and overall survival rates were 84% and 93%, respectively [

15], closely aligning with our findings of 84.5% and 93.9%. Similarly, Şahin et al. reported 5-year disease-free and overall survival rates of 85% and 100%, respectively, with a lower recurrence rate (13.4%) than in our series (23.6%). Advanced FIGO stage and positive peritoneal cytology were independent predictors of shorter disease-free survival [

16]. Supporting prolonged follow-up, recent studies show that up to one-third of recurrences occur after 10 years, especially in stage IC and cyst rupture cases [

17]. In contrast, a small retrospective study of 18 patients found no significant difference in disease-free survival across FIGO stages (p = 0.52), likely due to early-stage predominance and low event rate [

18]. In another multicenter prospective study of 208 patients reported no benefit of additional staging surgery and suggested that follow-up beyond five years may be unnecessary, as survival did not differ between recurrences detected during scheduled visits and those diagnosed symptomatically [

19]. Although overall survival analysis was limited in our cohort due to the low number of observed death events (n=5), the 5-year overall survival rate of 89.3% closely aligns with previously reported ranges in the literature (85–95%). Large retrospective series consistently report favorable survival outcomes in early-stage adult granulosa cell tumors: overall survival exceeding 90% has been described for early-stage cases in institutional studies [

16,

20,

21,

22]. Collectively, these data reinforce the indolent but persistent nature of adult granulosa cell tumors, underscore the generally favorable long-term prognosis when diagnosed early, and support our observed overall survival despite incomplete multivariate modeling.

Stage III disease was independently associated with shorter disease-free survival in our cohort, consistent with the MITO study, which emphasized the risk of late recurrence. While the MITO study reported a median recurrence time of 53 months and 47% of relapses beyond five years, our cohort showed a similar interval but a lower 5-year recurrence rate (32.7%) [

3]. This lower rate may be attributed to the predominance of early-stage diagnoses and standardized surgical management at a high-volume tertiary center, emphasizing the value of expert care. With a median follow-up of nearly 10 years, the mean time to recurrence was 58.4 months, and several relapses occurred beyond five years, underscoring the indolent but late-relapsing nature of adult granulosa cell tumors. These findings support a risk-adapted follow-up strategy, particularly for patients with advanced stage.

Consistent with the national Turkish TOG cohort, our study demonstrated comparable 5-year disease-free survival (84.5% vs. 86%) and confirmed advanced FIGO stage as a key predictor of recurrence. Both cohorts also linked atypical endometrial pathology and postmenopausal status to poorer outcomes, suggesting a hormone-dependent mechanism—supported by the estrogen-secreting nature of adult granulosa cell tumors. In the TOG cohort, hyperplasia and concurrent endometrial carcinoma were observed in 30% and 7.5% of cases, respectively [

8]; similarly, our cohort showed rates of 12.7% and 5.4%, predominantly in postmenopausal women (p = 0.002). Similarly, a large retrospective analysis in Japan reported complex atypical hyperplasia in 7.3% and low-grade endometrial carcinoma in 3.1% of cases, with tumor size significantly predicting synchronous endometrial cancer in menopausal patients [

23]. These findings underscore the need for thorough endometrial assessment, especially in patients over 40 or those with abnormal uterine bleeding. Although estrogen receptor status was unknown in many cases, prior studies suggest a possible association with hormone responsiveness, though its prognostic significance remains uncertain.

In our study, tumor size >10 cm was associated with shorter disease-free survival in univariate analysis. Consistent with our findings, several retrospective and multicenter studies have shown that although larger tumor size may initially appear prognostic, it often loses independent significance after adjusting for confounding factors such as stage and completeness of surgery [

24,

25,

26]. These patterns collectively suggest that larger tumor size may reflect increased tumor burden or surgical complexity rather than being a direct driver of recurrence. Standardizing tumor size thresholds and reporting criteria in future studies is essential to clarify its true prognostic role.

Consistent with our findings, multiple large-scale analyses have consistently reported no significant benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy on recurrence or survival outcomes in adult granulosa cell tumors, even in advanced or recurrent stages. Some studies have even associated adjuvant treatment with worse progression-free or disease-free survival, raising concerns about potential overtreatment in low-risk patients [

5,

16,

27,

28]. Notably, the MITO-9 study confirmed that adjuvant chemotherapy lacked independent prognostic significance in FIGO stage IC patients, whereas incomplete surgical staging and non-specialized care settings were stronger predictors of recurrence [

29]. This reinforces the notion that chemotherapeutic regimens may not improve prognosis unless applied in clearly defined high-risk cases. Given the lack of randomized data, clinicians should be cautious when generalizing the potential benefits of adjuvant chemotherapy. Consistent with previous studies, our findings do not support its routine use in adult granulosa cell tumors; instead, treatment decisions should be individualized within multidisciplinary care pathways, preferably in specialized centers.

Although FOXL2 mutation is present in over 90% of adult granulosa cell tumors and serves as a specific diagnostic marker, molecular analysis could not be performed in our study. As recent studies have suggested a possible prognostic role for FOXL2 and other molecular alterations [

30,

31], future research incorporating comprehensive molecular profiling is warranted to better guide individualized management.

4.3. Strengths and Weaknesses

This study provides one of the most up-to-date analyses of adult granulosa cell tumors, incorporating clinical follow-up data as of July 2025. The inclusion of late recurrences (a hallmark of adult granulosa cell tumors) enhances the accuracy of long-term outcome assessment. A key strength is the consistency in diagnostic, surgical, and therapeutic management, as all patients were treated at a single tertiary center, reducing inter-institutional variability and strengthening internal validity. The study offers detailed clinicopathological data, including tumor size, mitotic index, disease stage, endometrial pathology, estrogen receptor status, and adjuvant treatment.

Robust statistical methods were applied, including Kaplan–Meier analysis, log-rank tests, and Cox regression modeling with clinically relevant thresholds. Analytical transparency was maintained by addressing discrepancies between mean disease-free survival and Kaplan–Meier estimates, likely due to censoring and subgroup imbalances. The study also provides real-world insight into the use of adjuvant chemotherapy in adult granulosa cell tumors, a field lacking prospective data, and explores recurrence timing and patterns.

However, limitations exist. The retrospective design introduces potential selection and information bias. The relatively small sample size limited statistical power, particularly in multivariate analyses. Lack of FOXL2 mutational testing, a key diagnostic and potential prognostic biomarker, precluded molecular-outcome correlations. Additionally, unknown estrogen receptor status in nearly half the cohort hindered assessment of hormone receptor-related prognostic implications. Due to limited subgroup sizes, statistical comparisons between adjuvant chemotherapy subgroups could not be conducted. The paradox of longer mean disease-free survival despite early recurrences in some subgroups likely reflects censoring effects and group heterogeneity. Lastly, serum Anti-Müllerian hormone levels were not consistently available, preventing evaluation of its prognostic or surveillance role.

These limitations underscore the need for larger, prospective multicenter studies with standardized molecular profiling to validate biomarkers and guide individualized, risk-adapted strategies in adult granulosa cell tumors.

5. Conclusions

Taken together, our findings highlight the importance of individualized risk stratification and prolonged surveillance in patients with adult granulosa cell tumors, particularly those with advanced-stage disease. The elevated recurrence risk observed in stage III cases may reflect microscopic peritoneal dissemination or suboptimal cytoreduction, thereby justifying follow-up beyond the conventional 5-year period. These results underscore the value of clinicopathology-based decision-making and advocate for multicenter collaborations to enhance prognostic modeling and optimize management in this rare tumor entity.

Future prospective studies integrating centralized pathology review and molecular profiling are warranted to validate these observations. Incorporating emerging biomarkers, such as FOXL2 mutation status or circulating tumor DNA, may also enable risk-adapted follow-up strategies and facilitate earlier detection of recurrence.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: AG, OÖ, PP, BKY, EG, UAŞ; Data curation: AG, OÖ, PP; Formal analysis: AG, OÖ, DG; Investigation and Methodology: AG, OÖ, BK, DG; Supervision: BKY, EG, UAŞ; Writing – original draft: AG; Writing – review & editing: AG, OÖ, PP; All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The authors declare that they have no financial relationships or funding sources to disclose related to this study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to our colleagues in the Department of Medical Oncology at Ege University Hospital for their invaluable support and collaboration.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- Gu, Y.; Wang, D.; Jia, C.; et al. Clinical characteristics and oncological outcomes of recurrent adult granulosa cell tumor of ovary: a retrospective study of seventy patients. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2023, 102, 782–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryk, S.; Färkkilä, A.; Bützow, R.; et al. Characteristics and outcome of recurrence in molecularly defined adult-type ovarian granulosa cell tumors. Gynecol Oncol. 2016, 143, 571–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangili, G.; Ottolina, J.; Gadducci, A.; et al. Long-term follow-up is crucial after treatment for granulosa cell tumours of the ovary. Br J Cancer. 2013, 109, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Likic Ladjevic, I.; Dotlic, J.; Stefanovic, K.; et al. Fertility-sparing surgery for non-epithelial ovarian malignancies: ten-year retrospective study of oncological and reproductive outcomes. Cancers (Basel). 2025, 17, 1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Yang, J.; Zhang, X.; et al. Role of adjuvant chemotherapy in stage IC ovarian granulosa cell tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gynecol Oncol. 2025 Apr 14. [CrossRef]

- Ray, L.J.; Young, R.H.; Sabbagh, M.F.; et al. Adult granulosa cell tumors of the ovary with tubular differentiation: a report of 80 examples of an underemphasized feature with clinicopathologic and genomic differences from other sex cord-stromal tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2025, 49, 770–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levin, G.; Zigron, R.; Haj-Yahya, R.; et al. Granulosa cell tumor of ovary: a systematic review of recent evidence. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2018, 225, 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oktar, O.; Korkmaz, V.; Tokalıoğlu, A.; et al. Prognostic factors of adult granulosa cell tumors of the ovary: a Turkish retrospective multicenter study. J Gynecol Oncol. 2024, 35, e39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, S.; Avesani, G.; Panico, C.; et al. Ovarian cancer staging and follow-up: updated guidelines from the European Society of Urogenital Radiology female pelvic imaging working group. Eur Radiol. 2025, 35, 4029–4039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inzani, F.; Santoro, A.; Travaglino, A.; et al. Prognostic predictors in recurrent adult granulosa cell tumors of the ovary: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2022, 306, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyibozkurt, A.C.; Topuz, S.; Gungor, F.; et al. Factors affecting recurrence and disease-free survival in granulosa cell tumors of the ovary. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2010, 31, 667–671. [Google Scholar]

- Sehouli, J.; Drescher, F.S.; Mustea, A.; et al. Granulosa cell tumor of the ovary: 10 years follow-up data of 65 patients. Anticancer Res. 2004;24(2C):1223–1229.

- Le, D.T.; Do, T.A.; Nguyen, L.L.T.; et al. Clinical and paraclinical features, outcome, and prognosis of ovarian granulosa cell tumor: a retrospective study of 28 Vietnamese women. Rare Tumors. 2022, 14, 20363613221148547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babarović, E.; Franin, I.; Klarić, M.; et al. Adult granulosa cell tumors of the ovary: a retrospective study of 36 FIGO stage I cases with emphasis on prognostic pathohistological features. Anal Cell Pathol (Amst). 2018, 2018, 9148124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhusaini, H.; Elshenawy, M.A.; Badran, A.; et al. Adult-type ovarian granulosa cell tumour: treatment outcomes from a single-institution experience. Cureus. 2022, 14, e31045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, M.; Arslanca, T.; Uçar, Y.Ö.; et al. The experience of a tertiary center for adult granulosa cell tumor: which factors predict survival? J Ovarian Res. 2024, 17, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, M.K.; Fong, P.; Mesnage, S.; et al. Stage I granulosa cell tumours: a management conundrum? Results of long-term follow up. Gynecol Oncol. 2015, 138, 285–91. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Temtanakitpaisan, A.; Kleebkaow, P.; Aue-aungkul, A. Adult-type granulosa cell ovarian tumor: clinicopathological features, outcomes, and prognostic factors. Asian Pac J Cancer Care. 2019, 4, 33–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brink, G.J.; Groeneweg, J.W.; Sickinghe, A.A.; et al. Is it time to abandon staging surgery and prolonged follow-up in patients with primary adult-type granulosa cell tumor? J Ovarian Res. 2025, 18, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, J.; Jiang, W. Effects of different surgical extents on prognosis of patients with malignant ovarian sex cord-stromal tumors: a retrospective cohort study. Sci Rep. 2024, 14, 22630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seagle, B.L.; Ann, P.; Butler, S.; et al. Ovarian granulosa cell tumor: a National Cancer Database study. Gynecol Oncol. 2017, 146, 285–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Liu, Y.; et al. Can adjuvant chemotherapy improve the prognosis of adult ovarian granulosa cell tumors? : a narrative review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022, 101, e29062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokalioglu, A.A.; Oktar, O.; Sahin, M.; et al. Defining the relationship between ovarian adult granulosa cell tumors and synchronous endometrial pathology: does ovarian tumor size correlate with endometrial cancer? J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2024, 50, 655–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, S.H.; Lee, S.J.; Kim, D.Y.; et al. A long-term follow-up study of 91 cases with ovarian granulosa cell tumors. Anticancer Res. 2014, 34, 1001–10. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, H.D.; Lin, H.; Jao, M.S.; Wang, K.L.; et al. A long-term follow-up study of 176 cases with adult-type ovarian granulosa cell tumors. Gynecol Oncol. 2012, 124, 244–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaacoub, S.; Hajj, L.; Khairallah, A. A clinicopathological study about the epidemiology of granulosa cell tumors in Lebanon. BMC Cancer. 2024, 24, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Y.; Yang, H. The prognostic significance of adjuvant chemotherapy in adult ovarian granulosa cell tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Control. 2023, 30, 10732748231215165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plett, H.; Ricciardi, E.; Vacaru, V.; et al. Adult ovarian granulosa cell tumors: analysis of outcomes and risk factors for recurrence. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2023, 33, 734–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergamini, A.; Cormio, G.; Ferrandina, G.; et al. Conservative surgery in stage I adult type granulosa cell tumors of the ovary: results from the MITO-9 study. Gynecol Oncol. 2019, 154, 323–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michálková, R.; Šafanda, A.; Hájková, N.; et al. The molecular landscape of 227 adult granulosa cell tumors of the ovary: insights into the progression from primary to recurrence. Lab Invest. 2025, 105, 102201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brink, G.J.; Hami, N.; Nijman, H.W.; et al. The prognostic value of FOXL2 mutant circulating tumor DNA in adult granulosa cell tumor patients. Cancers (Basel). 2025, 17, 1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).