1. Introduction

Ovarian cancer accounts for approximately 185,000 deaths worldwide annually, with high-grade serous ovarian cancer (HGSC) being the most common and lethal subtype, representing more than 70% of all epithelial ovarian cancer diagnoses [

1]. The current standard of care for first-line treatment in HGSC involves cytoreductive surgery and six cycles of platinum and taxane-based chemotherapy [

2]. While the majority of patients with HGSC initially respond well to chemotherapy, over 70% will relapse within three years, and ultimately developing resistance to treatment [

2,

3,

4].

New treatment modalities, such as poly-ADP-ribosepolymerase (PARP) inhibitors and of anti-angiogenic agents have improved patient outcomes by extending progression free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) [

5,

6,

7,

8]. However, these therapies are frequently associated with substantial toxicity, leading to treatment discontinuation (12-54%), dose reduction (28-70.9%), and dose interruption (20-79.5%) due to adverse effects [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. This challenges underscore the necessity of identifying novel therapeutic approaches that increase PFS and OS without compromising quality of life.

The estrogen receptor (ER) is expressed in the majority of epithelial ovarian cancer cases, rendering it a potential target for endocrine therapy [

10,

11,

12]. Following menopause, estrogen continues to be synthesized synthesized in peripheral tissues such as the liver, adipose tissue, brain, skin, and heart, despite the cessation of ovarian estrogen production [

13]. Endocrine therapy has long been established as the standard maintenance treatment in ER positive breast cancer [

14,

15]. However, in ovarian cancer, endocrine agents such as aromatase inhibitors, fulvestrant, gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogues and tamoxifen have been primarily investigated in relapsed, heavily pretreated patients [

12,

16]. The reported benefits of endocrine therapy of endocrine therapy in ovarian cancer have been inconsistent, and its potential synergy with other targeted therapies, such as PARP inhibitors or anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) antibodies, remains uncertain

. While endocrine therapy is increasingly recognized as a viable option for low-grade serous ovarian cancer (LGSC), its role in the management of HGSC remains a subject of ongoing debate.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design, Study Population and Study Size

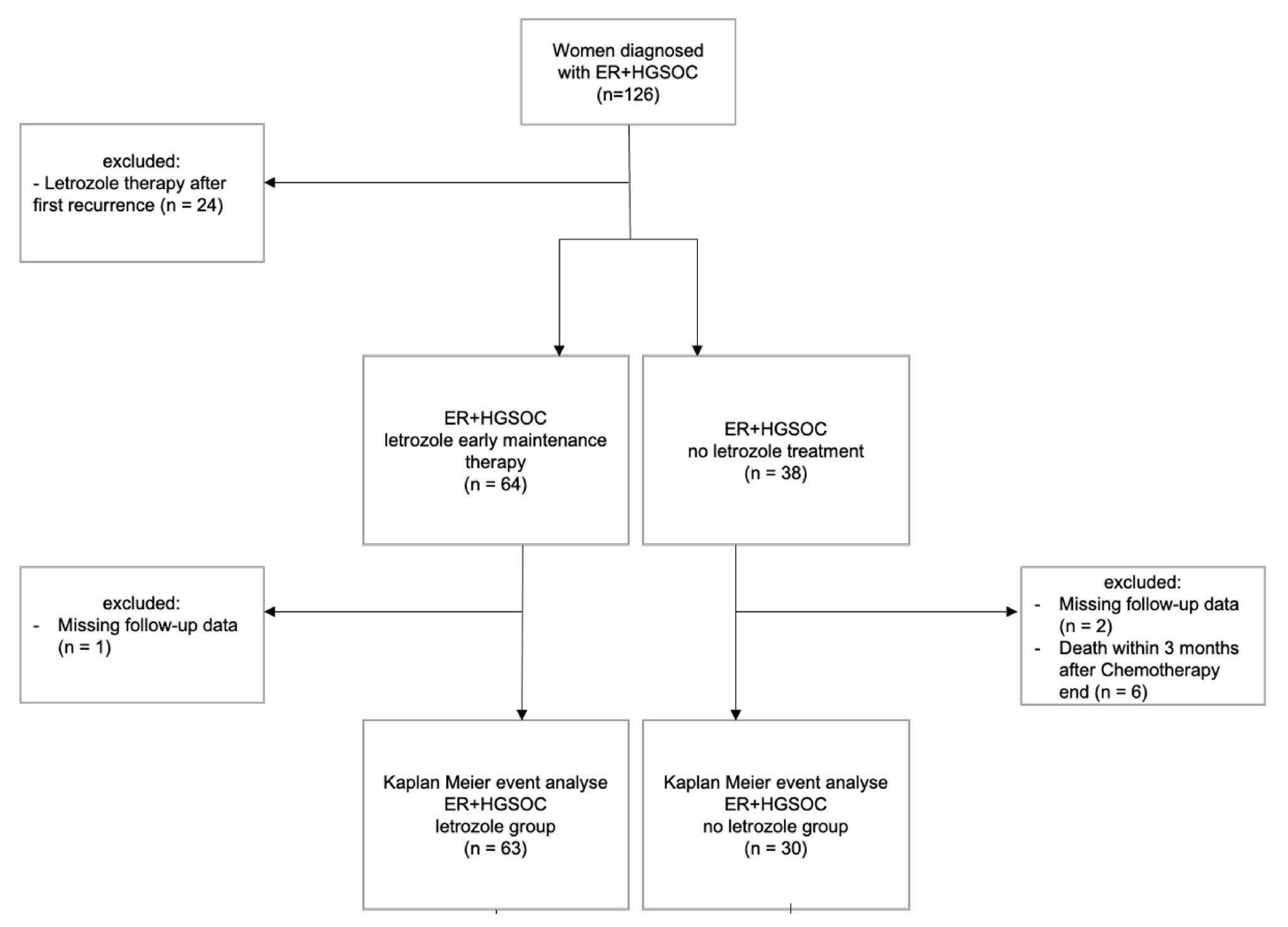

A single centre, retrospective cohort study was conducted at the Gynaecological Cancer Centre of the University Women’s Hospital Basel. We identified and analyzed data of 102 patients with newly diagnosed ER positive HGSC who received maintenance therapy with or without letrozole (2.5 mg daily) between January 2013 and December 2021 (

Figure 1). This study expands on a previously published pilot study involving 50 patients with ER positive HGSC [

17], incorporating data from additional 52 patients enrolled in subsequent years.

The inclusion criteria for this study were 1) histologically confirmed high grade serous ovarian, peritoneal, or fallopian tube cancer and 2) ER expression ≥1% confirmed by immunohistochemistry staining. The decision to administer letrozole was made collaboratively between patients and their physicians. Patients with missing follow-up data were excluded from the analysis, as were those who deceased within three months following completion of adjuvant chemotherapy. During the study period, patients in Switzerland routinely received anti-VEGF antibody bevacizumab in FIGO stage IIIC and IV or in cases with macroscopic residual disease (R) status, in accordance with Swiss-Medic approval. Additionally, since July 2019, Swiss-Medic has approved the use of PARP inhibitor olaparib maintance therapy for patients with newly diagnosed epithelial ovarian cancer.

2.2. Variables, Data Sources and Measurement

Primary endpoints of this study were PFS and OS. PFS was defined as the time from completion of first-line adjuvant chemotherapy until recurrence or death of any cause with recurrence defined as symptomatic relapse confirmed by radiological examination. OS was defined as the time from diagnosis to death of any cause or last follow-up appointment.

Various potential predictive and prognostic factors were evaluated, including ER expression, residual disease status, FIGO stage, age at diagnosis, and the use of letrozole therapy [

17,

18,

19]. To ensure the accuracy of the analysis, potential confounding variables were identified and controlled for. These confounders included co-medication with established maintenance therapies, tumour burden, and variations in treatment duration and initiation timing.

Clinicopathological data and disease progression information were collected by retrospective chart reviews. Side effects were documented during routine oncological follow-up visits every three months. For patients at increased risk for osteoporosis, bone density scans were conducted, and supplemention with Vitamin D, calcium, or denosumab was administered as required to mitigate potential bone loss.

2.3. Quantitative Variables

Patients were assigned to the letrozole group if they had received adjuvant letrozole maintenance therapy for at least three consecutive months. Those who declined or did not receive letrozole for any reason formed the control (no letrozole) group. Letrozole therapy could be initiated at any time after the initial diagnosis, and discontinuation was allowed at the patient’s discretion. Subgroup analysis was performed stratifying patients with no residual disease (R0) and residual disease (R) after primary cytoreductive surgery.

2.4. Statistical Methods

Descriptive statistics were used to evaluate clinical and demographic characteristics of the study cohort. Categorical data were presented as counts and frequencies, while metric or ordinal variables were expressed as medians (min, max). The Kruskal-Wallis test was used for metric and ordinal variables, and chi-squared or Fisher’s exact tests were used for categorical variables. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Time to event analyses were performed using the Kaplan-Meier method, and survival outcomes were compared using log-rank tests. Cox proportional hazard models were used to assess the potential influence of prognostic factors of patient outcomes. Missing data, concerning letrozole exposure, residual disease status, chemotherapy dates, and recurrence dates, primarily due to continuation of therapy at regional hospitals, were documented in a flowchart and excluded from the statistical analysis. All statistical analysis were conducted using R statistical software (version 4.1.3).

3. Results

3.1. Cohort Characteristics

The study cohort included 102 patients with ER positive HGSC, including FIGO stages IC-IV. Among them, 8 patients (7,8%) were classified as FIGO stage I-II, while 94 patients (92,2%) had FIGO stage III-IV disease. The median age of the cohort was 67 years. A total of 64 patients (62,7%) received adjuvant maintenance therapy with letrozole, whereas 38 patients (37,3%) did not. The median follow-up time was 23.5 months. Demographic and clinicopathological baseline characteristics of the study population are summarized in in

Table 1, demonstrating an overall balanced distribution between the letrozole and no letrozole groups. Bevacizumab was administrated as part of adjuvant treatment in 38 patients (60.3%) in the letrozole group and 16 patients (43.2%) in the no letrozole group. A higher proportion of patients with a

BRCA1/2 mutation was observed in the letrozole group (28.6% vs. 10.5%). Additionally, residual disease was more prevalent in the letrozole group compared to the no letrozole group (55% vs. 34.3%).

3.2. Safety Profile of Letrozole Treatment

No major adverse side effects of letrozole were observed in our cohort. Treatment interruption due to minor side effects (hot flushes, fatigue, arthralgia) were observed in 8 patients (12.5%).

3.3. Effect of ER Expression on Letrozole Benefit

The median ER expression in the entire cohort was 70%, with a median of 77.5% in the letrozole group versus 60% in the no letrozole group. There was no significant interaction between ER expression and letrozole in relation to PFS (HR 1.02, CI 95% 0.987-1.045, P=0.295) or OS (HR 1.05, CI 95% 0.979-1.124, P=0.176).

3.4. Univariate Survival Analysis of Letrozole as Maintenance Therapy

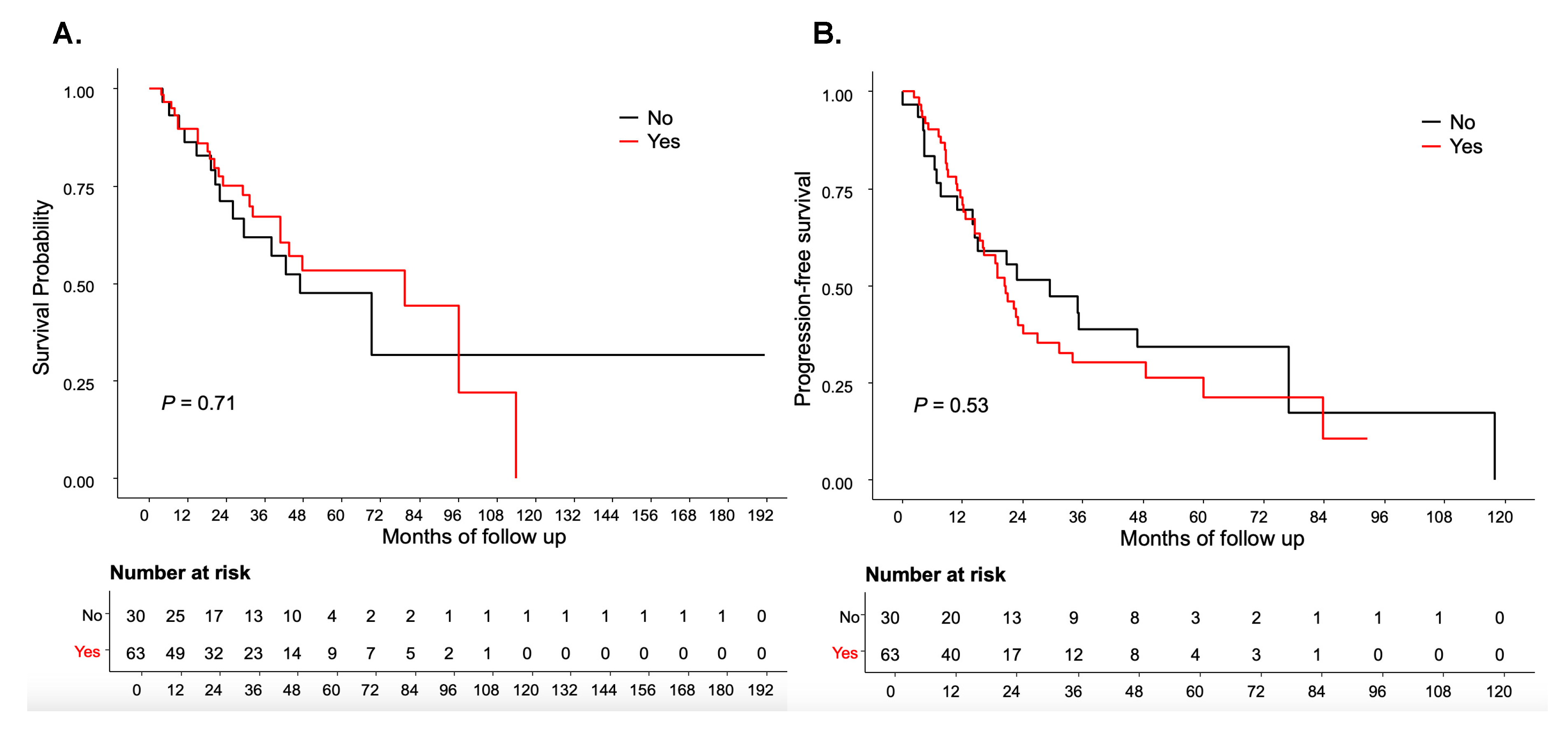

No significant differences were observed in PFS and OS between patients receiving letrozole and those who did not (

P=0.53 and

P=0.71) (

Figure 2A,B). The median PFS was 20.56 months in the letrozole group versus 29.34 months in the no letrozole group, while the median OS was 79.48 months and 46.85 months, respectively.

3.5. Benefit of Letrozole Maintenance Therapy According to Residual Disease

Residual disease status information was available for 95 patients (93.1%). Among these, 50 patients (52.6%) had R0 following primary cytoreductive surgery. In the R0 subgroup, 27 patients (54%) received letrozole, while 23 patients (46%) did not. Within this subgroup, 18 patients (36%), and 15 patients (30%) received PARP inhibitors at some point in their treatment regimen.

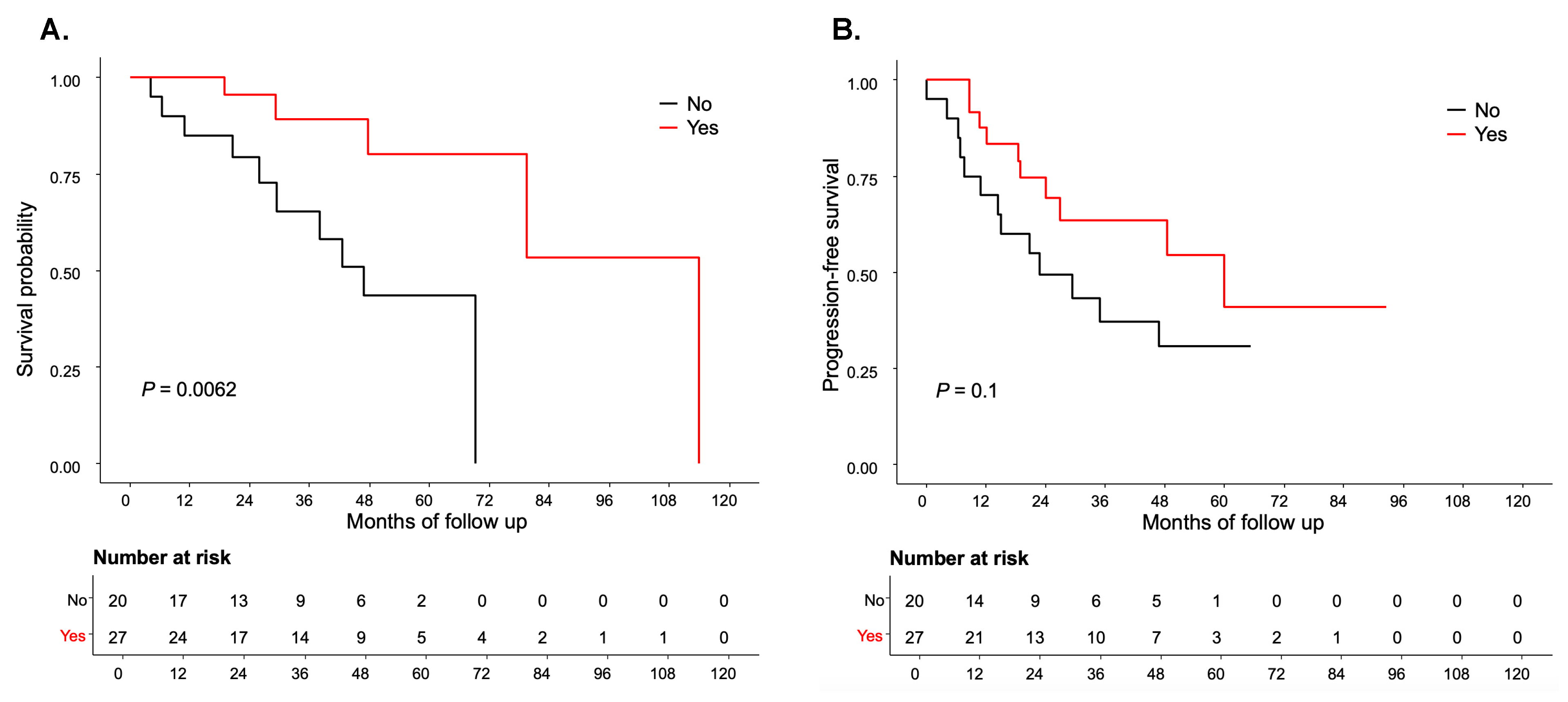

Patients in the R0 subgroup-letrozole group demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in OS compared to the R0-no letrozole-group (median 114 months vs. 56.85 months,

P=0.006) (

Figure 3A). Additionally, a trend towards improved PFS was observed in the R0-letrozole group compared to the R0-no letrozole group (median 59.97 months vs. 22.79 months,

P=0.1), although this did not reach statistical significance (

Figure 3B). Conversely, in patients with R, no statistically significant association was found between adjuvant letrozole therapy and PFS or OS (

P=0.17 and 0.65, respectively) (

Supplementary Tables S1 and S2).

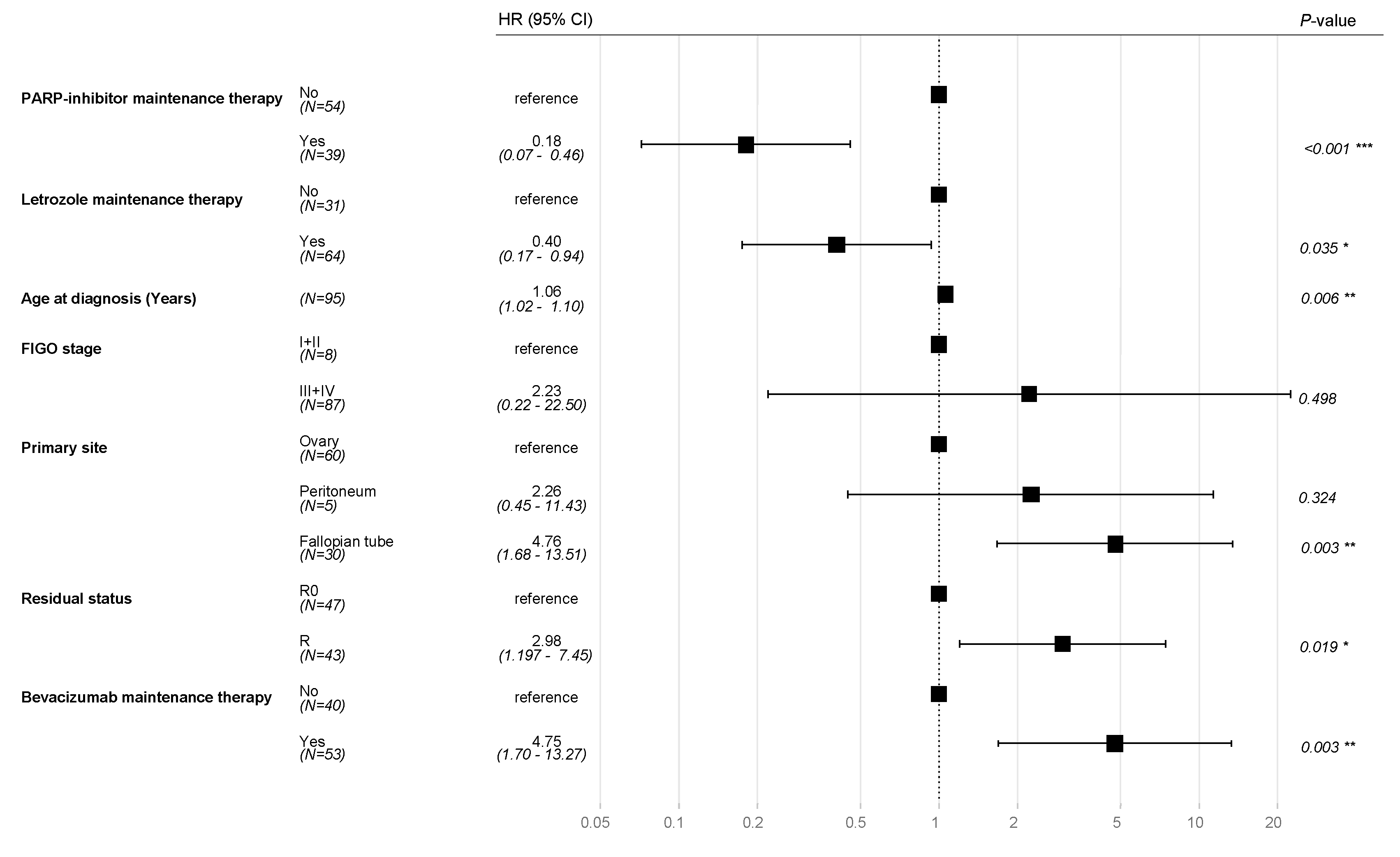

3.6. Benefit of Letrozole Maintenance Therapy after Multivariate Model Adjustment

The typical prognostic factors for ovarian cancer, including FIGO stage, age at diagnosis, residual disease, and primary tumor sites, were incorporated into multivariate Cox regression model alongside treatment regimens with PARP inhibitors and bevacizumab. After adjusting for these variables, adjuvant therapy with letrozole was remained statistical significantly associated with OS (HR 0.40, CI 95% 0.17-0.94, P=0.035).

In addition, PARP inhibitor therapy was associated with an OS benefit (HR 0.18, CI 95% 0.07-0.46

P<0.001). As expected, residual disease (HR 2.98, CI 95% 1.97-7.45,

P=0.019) and adjuvant treatment with bevacizumab (HR 4.75, CI 95% 1.69-13.27,

P=0.003) were associated with poorer OS (

Figure 4).

4. Discussion

Due to the ability aromatase inhibitors for off-label use in Switzerland, we were able to generate a hypothesis regarding the application of letrozole, either alone or in combination with anti-VEGF antibody bevacizumab or PARP inhibitors, as maintenance therapy for patients with ER positive HGSC. Our findings showed that HGSC exhibit a high median ER expression of approximately 70% and that endocrine therapy with letrozole is well tolerated, with a low discontinuation rate of 12.5% in our cohort. While the results from retrospective data cohorts are inherently limited by their non-randomized nature, our results suggest that patients with R0 after primary cytoreductive surgery may experience a survival benefit from adjuvant letrozole therapy.

While endocrine therapy is heavily discussed in LGSC, this study represents the first real world dataset analyzing aromatase inhibitor use in the adjuvant setting alongside routine targeted therapies in HGSC. Despite clear evidence that each ovarian cancer subtype has distinct molecular profiles and ER expression patterns [

20], endocrine therapy has primarily been investigated in small Phase I and II trials involving heavily pretreated patients and mixed histological subtypes [

12,

16]. A meta-analysis of endocrine therapy in patients with recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer described a clinical benefit of 41%, highlighting the existence of a responsive subgroup [

12]. However, the the frequency of hormone receptor expression in HGSC remains variaby reported and is often omitted from existing studies. In agreement with findings from the Ovarian Tumor Tissue Analysis (OTTA) consortium study (20), our cohort demonstrated a high median ER expression rate of 70%, consistent with prior analyses of treatment naive and relapsed HGSC samples [

21].

In breast cancer, ER expression serves as a predictive marker for response to endocrine therapy [

22,

23]. However, its predictive value in ovarian cancer remains unclear. Despite ER expression levels ranging from 1-100% in our cohort, no correlation was observed between ER expression level and letrozole benefit in regards to PFS and OS. These results are consistent with the PARAGON phase II trial, which found no association between ER histoscores and clinical benefit rates [

24]. In contrast, some studies have reported higher response rates in patients with elevated ER histoscores [

11] or a proportional relationship between and ER expression [

25].

Both bevacizumab [

26,

27] and PARP inhibitors [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

28] have demonstrated efficacy in adjuvant and maintenance treatment settings for HGSC in multiple clinical Phase III trials. However, these therapies are frequently associated with substantial toxicities, including fatigue, hypertension, haematological, gastrointenstinal, and renal complications, leading to treatment discontinuation in 12-54% of cases [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

28,

29,

30,

31]. Additionally, control arms in past clinical trials differed from those in contemporary endocrine therapy studies, where new treatment approaches are compared against established maintenance therapies such as PARP inhibitors and bevacizumab. During our study period, bevacizumab was well established, whereas PARP inhibitors were still emerging as standard of care [

5,

9,

32], explaining the lack of combination treatment with bevacizumab and olaparib in our cohort and limited administration of niraparib.

The adjuvant maintenance phase is a critical period where curative potential may be maximized, necessating careful evaluation of treatments based on adverse effects and cost-benefit ratios. In line with previous reports results showing low toxicity in recurrent ovarian cancer [

33] and extensive experience in breast cancer [

34], our findings confirm a favorable safety profile for letrozole in HGSC. The most notable adverse effects of prolonged letrozole (2.5 mg/day) exposure include bone resorption and increased risk of hypercholesterolemia [

35]. However, these effects can be mitigated with bisphosphonates and cholesterol lowering agents. Furthermore, aromatase inhibitors did not show increased cardiovascular events when compared with placebo in the extended-adjuvant setting in breast cancer settings [

36].

The primary strength of this study lies in the off-label use of aromatase inhibitors in the adjuvant setting, a unique aspect facilitated by the Swiss regulatory framework. Additionally, to our knowledge, this is the first real world cohort of patients with HGSC receiving endocrine therapy in the adjuvant setting, whereas previous analyses have focused on heavily pretreated populations. However, this study is inherently limited by its retrospective, single center design. ER expression varied among patients, and the initiation of letrozole therapy occurred at variable time points following adjuvant chemotherapy. Furthermore, a selection bias favoring letrozole administration in patients with greater tumor burden cannot be excluded. Additionally, a positive

BRCA mutation status may confound survival outcomes, as patients with

BRCA-mutated tumours generally exhibit enhanced platinum and PARP inhibitor sensivity compared to non-carriers [

37]. However, the study cohort demonstrated comparable use of maintenance therapies between groups, as further confirmed through the multivariate analysis.

Implications for Practice and Future Research

This study underscores the potential utility of endocrine therapy as well-tolerated maintenance option in HGSC, particularly valuable for geriatric or medically frail patients. While limited by its retrospective design, our findings provide an essential foundation for ongoing and future prospective clinical trials evaluating endocrine therapy in the adjuvant setting of HGSC. Indeed, this real world retrospective data analysis contributed to the development of the ongoing ENGOT-ov54/Swiss-GO-2/MATAO trial [NCT04111978] [

18].

4. Conclusions

ER expression is highly prevalent in HGSC. In the adjuvant setting, letrozole, whether used alone or in combination with standard targeted thearpies, demonstrated a low toxicity profile with a low discontinuation rate. Future prospective clinical trials are needed to identify the subgroup of patients with HGSC who derive the greatest benefit from endocrine maintenance therapy.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Franziska Geissler, Tibor Zwimpfer, Viola Heinzelmann-Schwarz and Ursula Gobrecht-Keller; Data curation, Franziska Geissler, Flurina Graf and Andreas Schötzau; Formal analysis, Franziska Geissler, Tibor Zwimpfer and Andreas Schötzau; Funding acquisition, Franziska Geissler and Tibor Zwimpfer; Investigation, Franziska Geissler, Flurina Graf, Viola Heinzelmann-Schwarz and Ursula Gobrecht-Keller; Methodology, Franziska Geissler, Andreas Schötzau and Viola Heinzelmann-Schwarz; Project administration, Franziska Geissler, Tibor Zwimpfer, Viola Heinzelmann-Schwarz and Ursula Gobrecht-Keller; Resources, Franziska Geissler and Viola Heinzelmann-Schwarz; Software, Andreas Schötzau; Supervision, Franziska Geissler, Tibor Zwimpfer, Viola Heinzelmann-Schwarz and Ursula Gobrecht-Keller; Visualization, Ruth Eller and Andreas Schötzau; Writing – original draft, Franziska Geissler, Flurina Graf, Tibor Zwimpfer and Ursula Gobrecht-Keller; Writing – review & editing, Franziska Geissler, Ruth Eller, Bich Nguyen-Sträuli, Andreas Schötzau, Viola Heinzelmann-Schwarz and Ursula Gobrecht-Keller.

Funding

Franziska Geissler received research support by the Swiss Cancer Research Foundation & Swiss Cancer League [KFS-5445-08-2021]. Tibor Andrea Zwimpfer was supported by the Swiss National Foundation Return CH Postdoc.Mobility (P5R5PM_222151). This work was supported by the Swiss National Foundation (P500PM_20726); Bangerter-Rhyner Stiftung (0297); Margarete and Walter Lichtenstein-Stiftung; and Freie Gesellschaft Basel.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval was obtained from the Ethical Committee of Nordwest- und Zentralschweiz, Switzerland (EKNZ 2023-01324). All patients signed a general consent form, which included further use of health-related data. The anonymization of personal data was guaranteed. The whole study was performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki as well as local laws and regulations.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets that have been used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

Tibor Andrea Zwimpfer reports personal consulting fees from AbbVie that are outside the submitted work. Viola Heinzelmann-Schwarz reports personal consulting fees from AstraZeneca, AbbVie, and GSK that are outside the submitted work.

References

- Webb PM, Jordan SJ. Global epidemiology of epithelial ovarian cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2024, 21, 389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ledermann JA, Raja FA, Fotopoulou C, Gonzalez-Martin A, Colombo N, Sessa C. Newly diagnosed and relapsed epithelial ovarian carcinoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Annals of Oncology 2013, 24, vi24–v32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo N, Sessa C, du Bois A, Ledermann J, McCluggage WG, McNeish I, et al. ESMO–ESGO consensus conference recommendations on ovarian cancer: pathology and molecular biology, early and advanced stages, borderline tumours and recurrent disease. Annals of Oncology 2019, 30, 672–705. [Google Scholar]

- Bowtell DD, Böhm S, Ahmed AA, Aspuria PJ, Bast RC, Beral V, et al. Rethinking ovarian cancer II: reducing mortality from high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2015, 15, 668–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray-Coquard I, Leary A, Pignata S, Cropet C, González-Martín A, Marth C, et al. Olaparib plus bevacizumab first-line maintenance in ovarian cancer: final overall survival results from the PAOLA-1/ENGOT-ov25 trial. Annals of Oncology 2023, 34, 681–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coleman RL, Fleming GF, Brady MF, Swisher EM, Steffensen KD, Friedlander M, et al. Veliparib with First-Line Chemotherapy and as Maintenance Therapy in Ovarian Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 2019, 381, 2403–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore K, Colombo N, Scambia G, Kim BG, Oaknin A, Friedlander M, et al. Maintenance Olaparib in Patients with Newly Diagnosed Advanced Ovarian Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 2018, 379, 2495–2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiSilvestro P, Banerjee S, Colombo N, Scambia G, Kim BG, Oaknin A, et al. Overall Survival With Maintenance Olaparib at a 7-Year Follow-Up in Patients With Newly Diagnosed Advanced Ovarian Cancer and a BRCA Mutation: The SOLO1/GOG 3004 Trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2023, 41, 609–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Martín A, Pothuri B, Vergote I, DePont Christensen R, Graybill W, Mirza MR, et al. Niraparib in Patients with Newly Diagnosed Advanced Ovarian Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 2019, 381, 2391–2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitawaki J, Noguchi T, Yamamoto T, Yokota K, Maeda K, Urabe M, et al. Immunohistochemical localisation of aromatase and its correlation with progesterone receptors in ovarian epithelial tumours. Anticancer Res. 1996, 16, 91–97. [Google Scholar]

- Smyth JF, Gourley C, Walker G, MacKean MJ, Stevenson A, Williams ARW, et al. Antiestrogen Therapy Is Active in Selected Ovarian Cancer Cases: The Use of Letrozole in Estrogen Receptor–Positive Patients. Clinical Cancer Research 2007, 13, 3617–3622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paleari L, Gandini S, Provinciali N, Puntoni M, Colombo N, DeCensi A. Clinical benefit and risk of death with endocrine therapy in ovarian cancer: A comprehensive review and meta-analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2017, 146, 504–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geisler J, Lønning PE. Aromatase Inhibition: Translation into a Successful Therapeutic Approach. Clinical Cancer Research 2005, 11, 2809–2821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muss HB, Case LD, Atkins JN, Bearden JD, Cooper MR, Cruz JM, et al. Tamoxifen versus high-dose oral medroxyprogesterone acetate as initial endocrine therapy for patients with metastatic breast cancer: a Piedmont Oncology Association study. Journal of Clinical Oncology 1994, 12, 1630–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson L, Lawrence D, Dawson C, Bliss J. Aromatase inhibitors for treatment of advanced breast cancer in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langdon SP, Gourley C, Gabra H, Stanley B. Endocrine therapy in epithelial ovarian cancer. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2017, 17, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinzelmann-Schwarz V, Knipprath Mészaros A, Stadlmann S, Jacob F, Schoetzau A, Russell K, et al. Letrozole may be a valuable maintenance treatment in high-grade serous ovarian cancer patients. Gynecol Oncol. 2018, 148, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLaughlin PMJ, Klar M, Zwimpfer TA, Dutilh G, Vetter M, Marth C, et al. Maintenance Therapy with Aromatase Inhibitor in epithelial Ovarian Cancer (MATAO): study protocol of a randomized double-blinded placebo-controlled multi-center phase III Trial. BMC Cancer 2022, 22, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George A, McLachlan J, Tunariu N, Della Pepa C, Migali C, Gore M, et al. The role of hormonal therapy in patients with relapsed high-grade ovarian carcinoma: a retrospective series of tamoxifen and letrozole. BMC Cancer 2017, 17, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieh W, Köbel M, Longacre TA, Bowtell DD, deFazio A, Goodman MT, et al. Hormone-receptor expression and ovarian cancer survival: an Ovarian Tumor Tissue Analysis consortium study. Lancet Oncol. 2013, 14, 853–862. [Google Scholar]

- Vetter M, Stadlmann S, Bischof E, Georgescu Margarint EL, Schötzau A, Singer G, et al. Hormone Receptor Expression in Primary and Recurrent High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer and Its Implications in Early Maintenance Treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Effects of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy for early breast cancer on recurrence and 15-year survival: an overview of the randomised trials. The Lancet 2005, 365, 1687–1717.

- Tamoxifen for early breast cancer: an overview of the randomised trials. Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group. Lancet 1998, 351, 1451–1467. [Google Scholar]

- Kok PS, Beale P, O’Connell RL, Grant P, Bonaventura T, Scurry J, et al. PARAGON (ANZGOG-0903): a phase 2 study of anastrozole in asymptomatic patients with estrogen and progesterone receptor-positive recurrent ovarian cancer and CA125 progression. J Gynecol Oncol. 2019, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley B, Hollis RL, Nunes H, Towler JD, Yan X, Rye T, et al. Endocrine treatment of high grade serous ovarian carcinoma; quantification of efficacy and identification of response predictors. Gynecol Oncol. 2019, 152, 278–285. [Google Scholar]

- Burger RA, Brady MF, Bookman MA, Fleming GF, Monk BJ, Huang H, et al. Incorporation of Bevacizumab in the Primary Treatment of Ovarian Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 2011, 365, 2473–2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perren TJ, Swart AM, Pfisterer J, Ledermann JA, Pujade-Lauraine E, Kristensen G, et al. A Phase 3 Trial of Bevacizumab in Ovarian Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 2011, 365, 2484–2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujade-Lauraine E, Hilpert F, Weber B, Reuss A, Poveda A, Kristensen G, et al. Bevacizumab Combined With Chemotherapy for Platinum-Resistant Recurrent Ovarian Cancer: The AURELIA Open-Label Randomized Phase III Trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2014, 32, 1302–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza MR, Monk BJ, Herrstedt J, Oza AM, Mahner S, Redondo A, et al. Niraparib Maintenance Therapy in Platinum-Sensitive, Recurrent Ovarian Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 2016, 375, 2154–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman RL, Oza AM, Lorusso D, Aghajanian C, Oaknin A, Dean A, et al. Rucaparib maintenance treatment for recurrent ovarian carcinoma after response to platinum therapy (ARIEL3): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. The Lancet 2017, 390, 1949–1961. [Google Scholar]

- Pujade-Lauraine E, Ledermann JA, Selle F, Gebski V, Penson RT, Oza AM, et al. Olaparib tablets as maintenance therapy in patients with platinum-sensitive, relapsed ovarian cancer and a BRCA1/2 mutation (SOLO2/ENGOT-Ov21): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, 1274–1284. [Google Scholar]

- Ray-Coquard I, Pautier P, Pignata S, Pérol D, González-Martín A, Berger R, et al. Olaparib plus Bevacizumab as First-Line Maintenance in Ovarian Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 2019, 381, 2416–2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchetti C, De Felice F, Ergasti R, Scambia G, Fagotti A. Letrozole in the management of advanced ovarian cancer: an old drug as a new targeted therapy. International Journal of Gynecologic Cancer 2020, 30, 1058–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aromatase inhibitors versus tamoxifen in early breast cancer: patient-level meta-analysis of the randomised trials. The Lancet 2015, 386, 1341–1352.

- Mukherjee AG, Wanjari UR, Nagarajan D, K K V, V A, P JP, et al. Letrozole: Pharmacology, toxicity and potential therapeutic effects. Life Sci. 2022, 310, 121074. [CrossRef]

- Khosrow-Khavar F, Filion KB, Al-Qurashi S, Torabi N, Bouganim N, Suissa S, et al. Cardiotoxicity of aromatase inhibitors and tamoxifen in postmenopausal women with breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Annals of Oncology 2017, 28, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinopoulos PA, Norquist B, Lacchetti C, Armstrong D, Grisham RN, Goodfellow PJ, et al. Germline and Somatic Tumor Testing in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer: ASCO Guideline. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2020, 38, 1222–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).