1. Introduction

Quantum nanostructures such as quantum dots [

1,

2,

3], lens-shaped structures [

4,

5,

6], and tetrapods [

7] exhibit unique electronic and optoelectronic properties, which make them suitable for applications in multiple fields, from bioimaging [

8] to photovoltaics [

9]. Among these, quantum rings (QR) [

10,

11,

12] have attracted particular interest due to their unique electronic and optical characteristics, including Aharonov-Bohm oscillations and quantum interference effects [

13,

14], which open possibilities for their integration into optoelectronic devices and quantum information technologies [

15,

16,

17].

During the characterization and fabrication process of such structures, it has been possible to experiment with various geometries [

18,

19,

20,

21], many of which are based on coupling structures. In recent years, coupled quantum dot-ring (CQDR) systems [

22,

23,

24,

25] have attracted significant attention due to their highly tunable electronic states, which can be modified by external factors such as electric and magnetic fields, hydrostatic pressure, and structural parameters [

26]. This tunability makes CQDRs promising candidates for applications in optoelectronic devices, optical modulators [

27], and quantum communication technologies [

28]. These structures, formed by a QR coupled to a concentric quantum dot (QD), offer a versatile way to explore quantum interference phenomena and electromagnetically induced transparency (EIT).

CQDRs have also gained relevance due to their ability to host localized electronic states with versatile optical properties [

24,

26,

29,

30]. External perturbations on the structure, such as electric and magnetic fields, can substantially modify the electronic structure of these systems [

31,

32,

33,

34]. For example, the application of an electric field along the growth direction introduces Stark shifts and dipole moment variations [

35,

36,

37]. This motivates continued studies that include these external perturbations.

Recent studies on the interaction between donors and structures have yielded interesting conclusions. Some have concluded that the interaction between the confined electron and the neutral donor center results in position-dependent modifications to transition energies and absorption properties[

32,

38,

39]. Shallow donors add a layer of complexity to CQDRs due to their position within the structure [

40,

41], which plays a critical role in shaping electronic states and optical absorption spectra. Furthermore, recent studies on doubly ionized donors confined in CQDRs have provided information on the role of donor states and their interaction with external probes, such as hydrostatic pressure, electric fields, and temperature variations [

26]. The present study explores the interaction between a shallow donor and a CQDR.

Such facts motivate the present study of the energy levels of a

As CQDR, along with a detailed analysis of the consequences of external factors, such as magnetic and electric fields, while identifying the optoelectronic properties of the heterostructure. Furthermore, the study examines the phenomenon of EIT, in which quantum interference suppresses absorption while maintaining significant nonlinear optical properties [

42,

43].

This paper is organized as follows: in

Section 2, we describe the theoretical model, outlining the fundamental principles that govern the electronic and optical properties of CQDRs, along with a description of the basic theory.

Section 3 presents and discusses our numerical results, highlighting the impact of external perturbations and structural parameters on the electronic states and optical responses. Finally, our main conclusions are provided in

Section 4.

2. Theoretical Framework

In this work, we analyze the energy states and their associated wavefunctions in a CQDR structure under the influence of external electric and/or magnetic fields applied in the z-direction. To complete our study, we investigate optoelectronic properties via EIT in a ladder or cascade configuration and linear optical absorption.

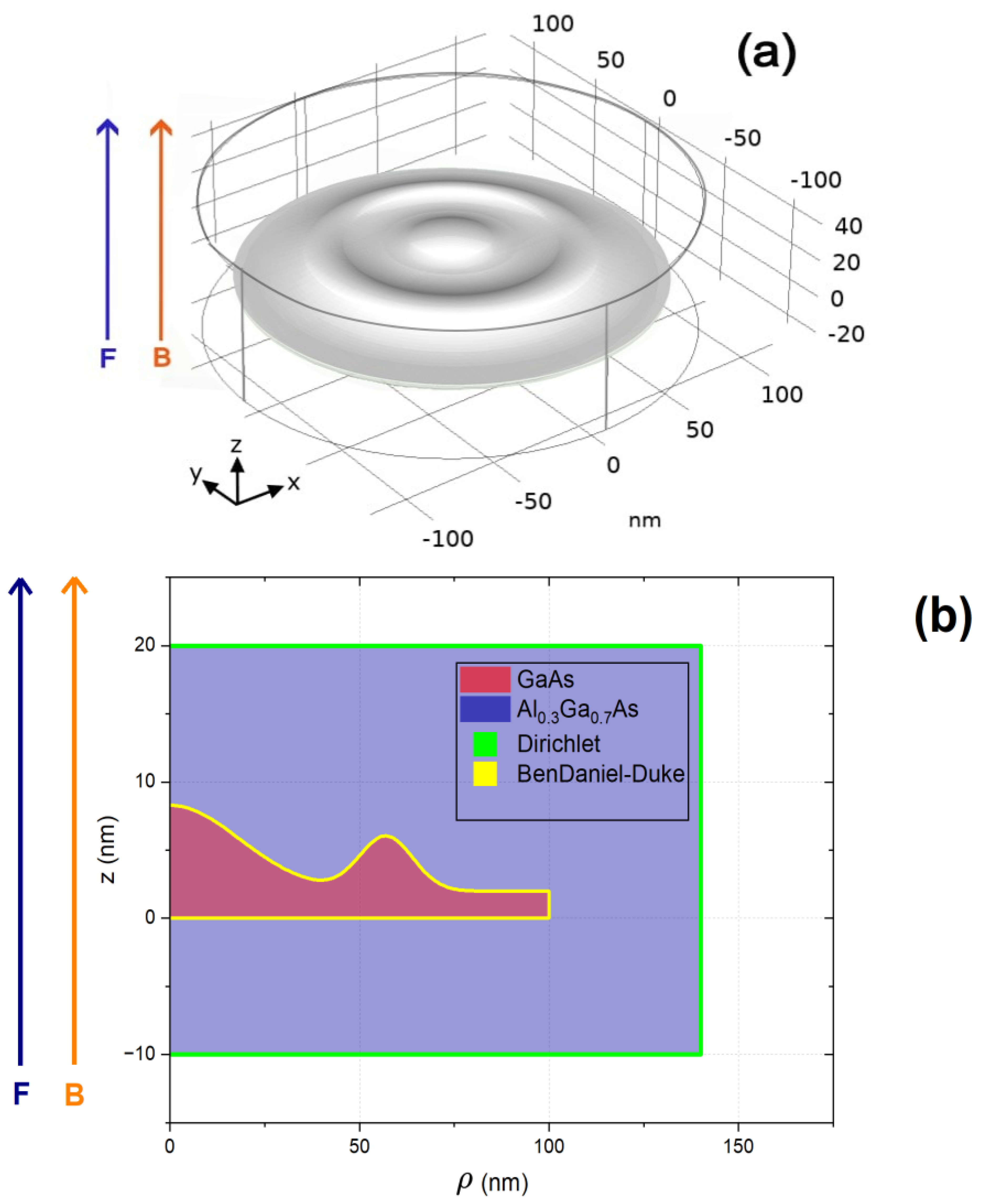

Figure 1 presents a schematic view of the CQDR under study, together with the main dimensions of the heterostructure. A 3D view of the nanostructure is shown in panel

(a), obtained by revolution around the

z-axis of

Figure 1(b). A cross-section of the structure (the

plane) is shown in panel

(b), where the two composing materials are easily identified,

i.e., the GaAs and the

As. The latter displays a barrier-like behavior, while the former presents a well-like behavior. This configuration is suitable for building a 2D-axisymmetric model where azimuthal symmetry reduces the computational cost of numerically solving the three-dimensional Schrödinger equation. The geometry of the nanostructure is a variation of a theoretical function [

32] that accurately reproduces an experimental profile of a GaAs CQDR, as obtained via the AFM technique by Somaschini [

24]. To enhance the visibility of the ring’s influence, the height of the central region (dot) has been deliberately reduced by 65% compared to the original geometry. For the sake of clarity, the reference system and the directions of the external fields are also depicted. The CQDR is made of GaAs, whereas the cylindrical host matrix in which it is embedded is made of

As with

.

The mathematical function describing the height,

, as depicted in

Figure 1 (a), is formally expressed as[

26]:

In this equation, represents the height of the central dot, denotes its characteristic width, signifies the height of the ring, corresponds to the radius of the ring, indicates the width of the ring and establishes the baseline height. For the specific nanostructure under investigation, the precise values assigned to these parameters are as follows: , , , , , and .

Using the effective mass approximation and taking the assumption of parabolic conduction bands, the Schrödinger equation of an electron interacting with external electric and magnetic fields is written in cylindrical coordinates as follows:

where

i designates each of the quantized states,

i.e., the value

represents the ground state and

corresponds to the excited states. The

j-index identifies each one of the two materials that make up the CQDR, and

e is the absolute value of the electron charge. The values of the effective mass and

depend on the region where the Schrödinger equation is solved, as shown in

Figure 1 (a). The effective mass is considered to be position-independent within each material. The effective mass and the confining potential are taken for the calculations in the following way:

and

In this work, both electric and magnetic fields are applied along the z-direction, i.e., and .

The gauge chosen for the description of the magnetic field effect entails the following conditions for the magnetic vector potential,

:

(i) and

(ii). Under these two conditions, the Hamiltonian in Eq. 2 takes the form:

This Hamiltonian is separable,

, which allows to replace

in Eq.

5 (here

). Taking the derivatives with respect to

, the Schrödinger equation for the radial function

can be written as:

where

are the eigenvalues associated with the 2D-wavefunctions

. The solution of Eq.

6 was investigated using the finite element method (FEM) as implemented in the COMSOL-Multiphysics software [

44]. The boundary conditions were imposed in the following way:

(i) BenDaniel-Duke boundary condition for wave function continuity on the core-shell interface,

,

(ii) BenDaniel-Duke boundary condition for the wave function first derivative continuity:

with

and

(iii) Dirichlet boundary conditions on the outer surface of the embedding

As matrix:

.

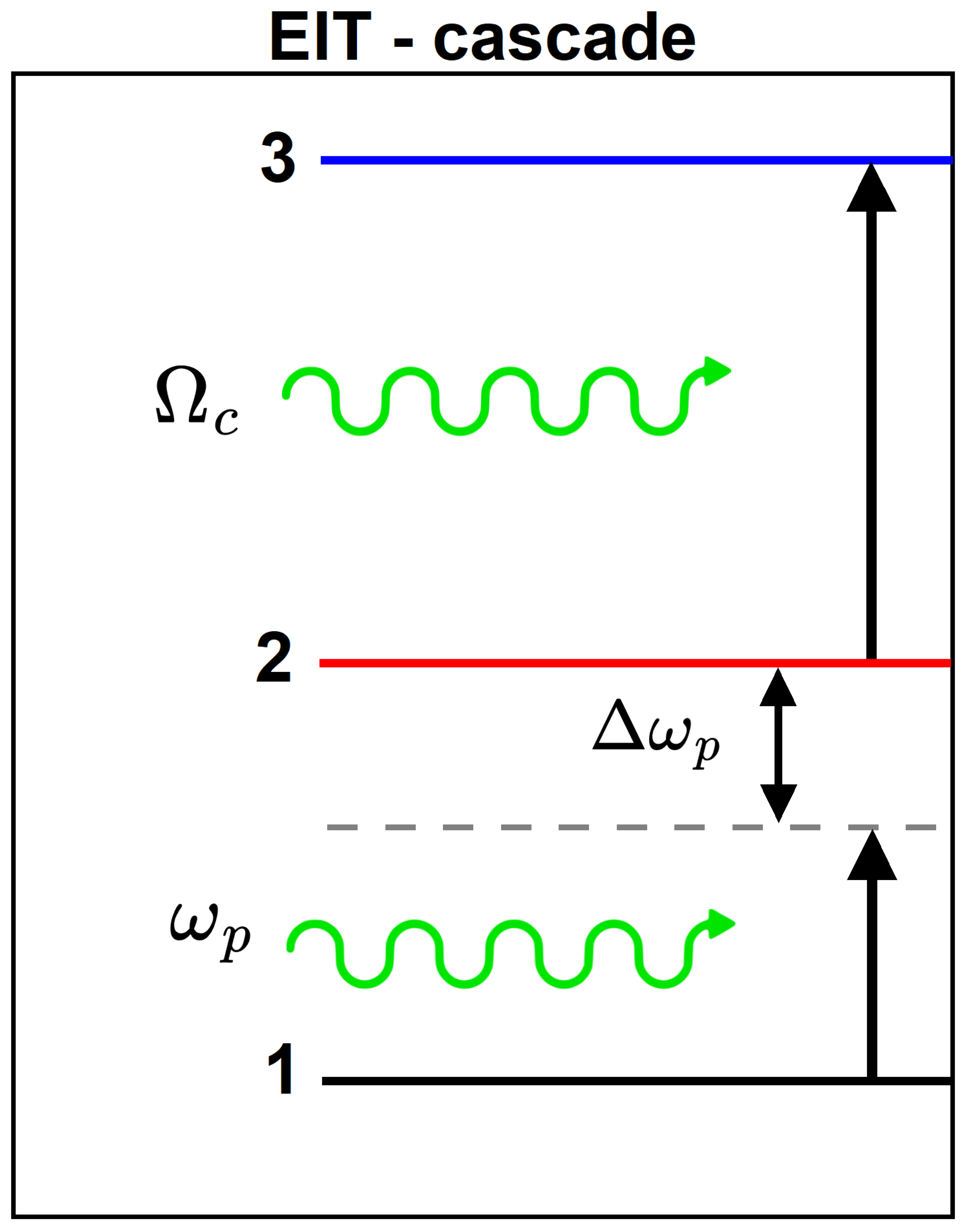

The cascade configuration chosen for the EIT analysis comprises the first three

energy levels and is modeled in

Figure 2.

Within the density matrix approach, an expression for the imaginary part of the linear susceptibility can be derived in terms of the probe field and Rabi frequencies as follows [

31]:

where is the detuning between the probe field frequency and that of the transition,

is the electric dipole matrix element for a transition between states

and

induced by a light field with polarization vector

. While the general notation uses indices

, the specific transition from the ground state to the first excited state (

) is represented by the element

, as shown in the formula,

is the Rabi frequency associated with the aforementioned

transition,

stands for the population difference between the two involved levels, and

are the decay rates for the

transition. The Rabi frequency is taken to be fixed for the material throughout this study. The imaginary part of the linear susceptibility is related to the linear optical absorption, allowing for the EIT calculation as in [

31]:

where

is the speed of light in the medium,

. Finally, the linear optical absorption coefficient (LOAC) for the transition

can be deduced from Eq.

8, subtracting all contributions coming from the third level,

i. e.,

,

.

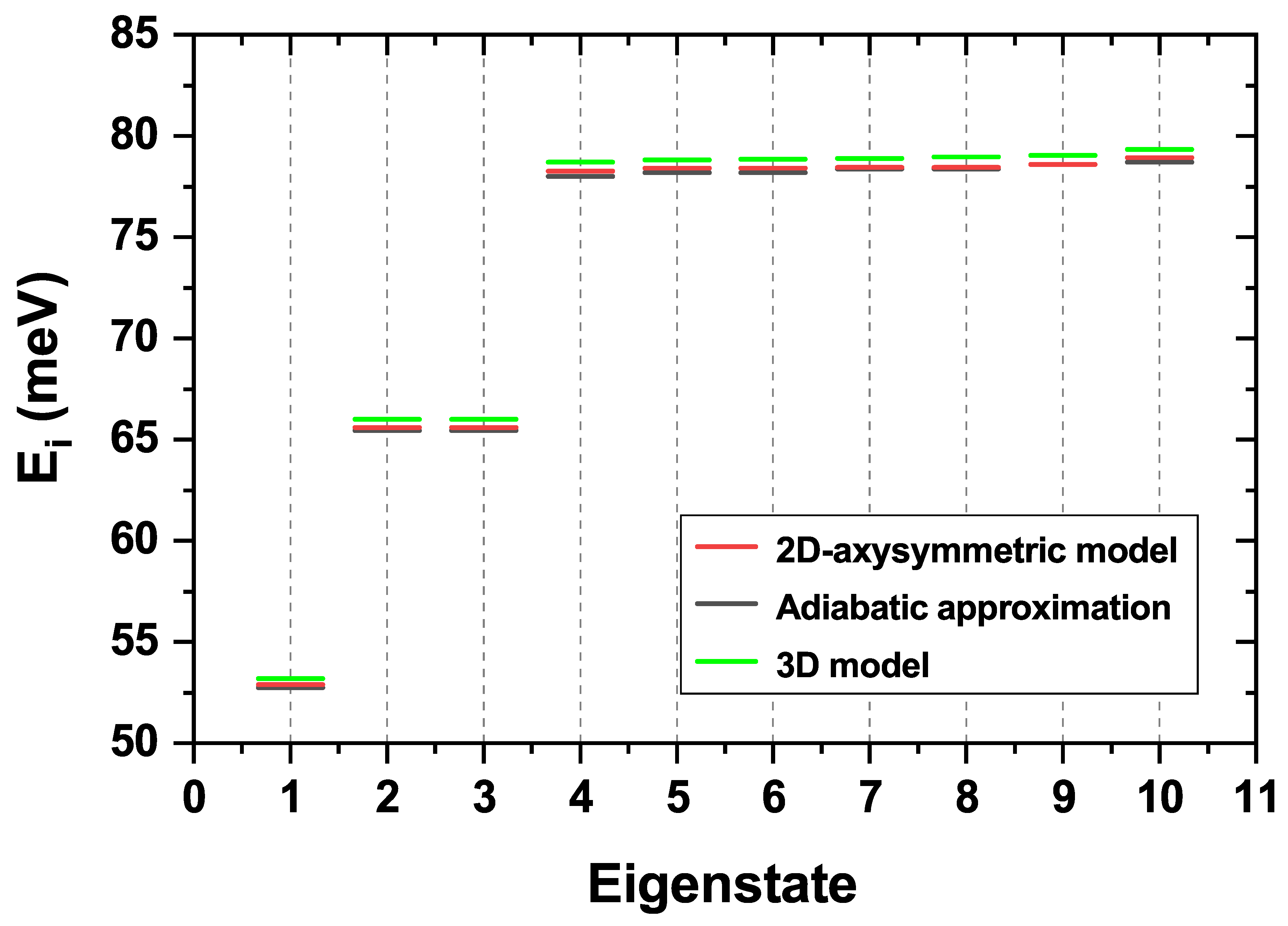

To close this section, we provide in

Figure 3 the comparison of the first ten electron eigenenergies obtained by solving the three-dimensional Schrödinger equation, by implementing the adiabatic approximation, and through the 2D-axisymmetric model described along this section. The use of the adiabatic approximation is justified by the system’s morphological features, where confined carriers experience significantly greater quantum confinement in the

z-direction than in the

plane [

32]. This geometric asymmetry supports the decoupling of the electron’s motion into two separate kinetic contributions (

z-axis and

-plane). The procedure begins by "freezing" the

-plane motion to solve a one-dimensional Schrödinger equation for the

z-axis. The resulting eigenvalues are then introduced into the

-plane Schrödinger equation, reducing the original three-dimensional Hamiltonian to a simplified and numerically solvable two-dimensional problem.

As

Figure 3 shows, the results from all three methods are in very good agreement, the 3D model being the most precise. Therefore, we can confidently conclude that the implementation of the simpler axisymmetric model is justified for our analysis. At this point, it is worth mentioning that the fact of having seven eigenstates with similar energies does not mean a seven-fold degeneracy, given that the eigenenergies associated with the dot are mixed with those associated with the ring. The latter will be thoroughly discussed later on.

3. Results and discussion

The Schrödinger equation, given in Eq.

6, was solved using the FEM via the COMSOL-Multiphysics software [

44] within the effective mass approximation. We computed the lowest confined electron energy states in a GaAs CQDR embedded in an

As cylindrical matrix with

applying external electric and/or magnetic fields perpendicular to the structure. We calculated the EIT and the LOAC in the presence and absence of the fields mentioned above. The parameters for electrons adopted in the numerical calculations are

,

(here,

is the free electron mass) [

45] and the barrier height of

meV [

46]. Calculations were performed for negative and positive values of the electric field

F. The CQDR profile under study is an adaptation of AFM measurements [

24]. In the first stage, the study will focus on analyzing the effects of electric and/or magnetic fields on electron energy levels when the fields are applied perpendicular to the structure.

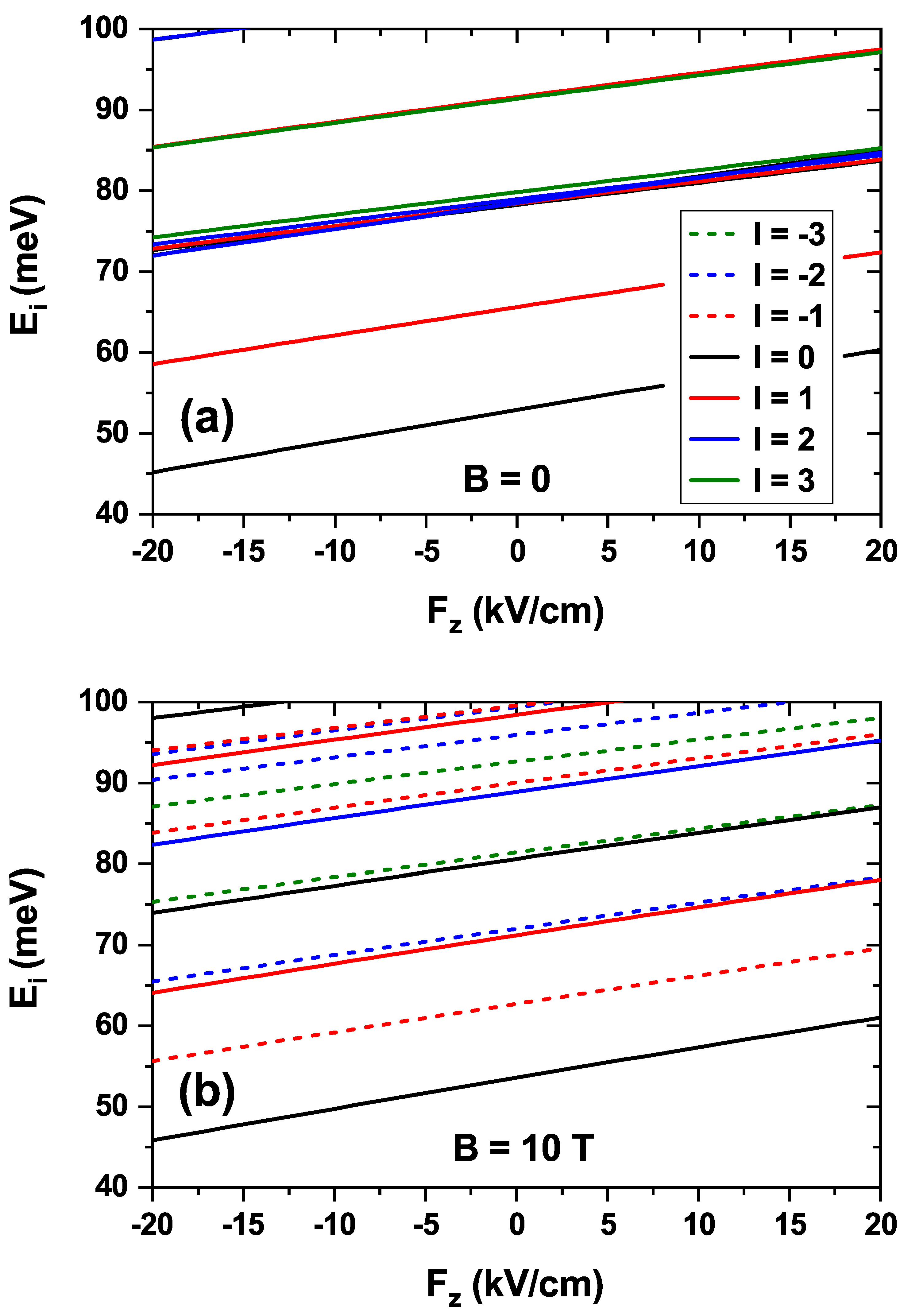

Figure 4 shows the variation in the electron energies of the first states obtained by applying an electric field directed along the

z-axis. Negative field values indicate that the field points in the negative

z-direction. The implementation of a 2D-axisymmetric model allows the distinction of states according to the quantum number

l. In this work, the first states with

are analyzed. Panel

(a) of

Figure 4 is devoted to the case in which no magnetic field is applied, and, therefore, the states with positive (solid lines) and negative (dashed lines)

l are superimposed, as is straightforward from Eq.

6. The energy of the states increases as the electric field shifts from negative to positive values, given that the electron wave function is pushed towards the lower region of the CQDR, becoming more confined as the field intensity increases. The following states, after the first

and

states, which correspond to the dot, are concentrated in less than 5 meV. Here, the ring states appear and are intermixed with the dot states. To complete this analysis, panel

(b) shows the energy variation with the electric field in the presence of a magnetic field, also applied along the

z-direction. This magnetic field is responsible for the degeneracy breaking of the energies associated with

and

. Comparing panels

(a) and

(b) of

Figure 4, states with

(

) are found to display higher (lower) energies than in the absence of the magnetic field. At the same time, all of them show increasing energies as the electric field intensity ranges from more negative to more positive values. In both the absence and the presence of an external magnetic field, a linear increasing trend in the energy levels is observed as the electric field ranges from

to

kV/cm, such that the levels are practically parallel. A linear fit of these allows the calculation of an average slope, which, in the case of a zero magnetic field, is

meV cm/kV, while in the case of a

T magnetic field it is of

meV cm/kV. The relative standard deviation in the first case is

and in the second case is

. The value of this slope can be related to the Stark shift [

47,

48].

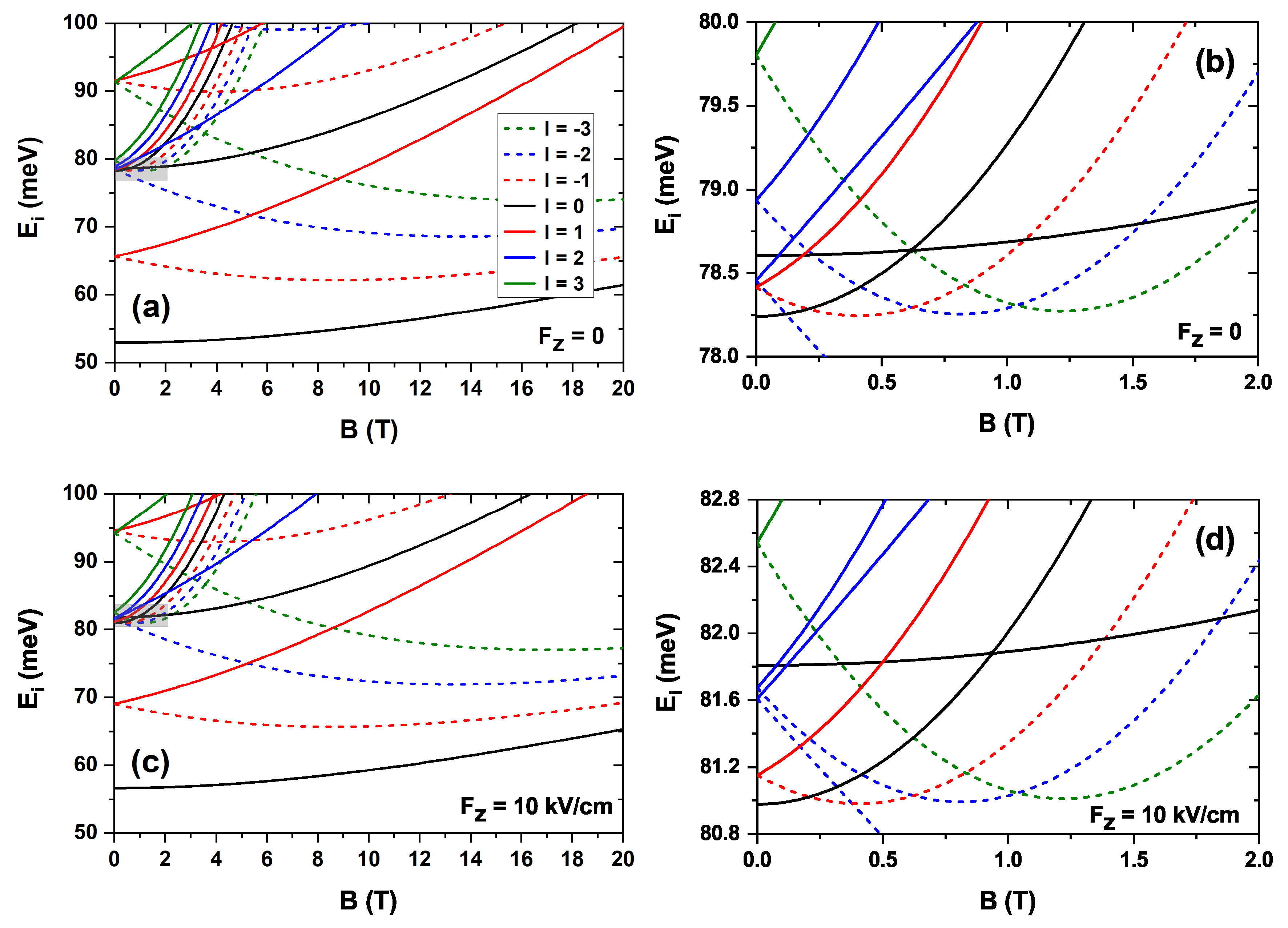

For the sake of completeness, the variation in electron energy is now analyzed in the presence of an externally applied magnetic field, both in the absence and in the presence of an electric field, with both fields parallel to the

z-axis. The results are shown in

Figure 5, which distinguishes the states based on the quantum number

l, as previously discussed. Both levels whose energy decreases with the magnetic field (typically of QDs) and levels whose energy increases (typically of QRs) are observed. Panels

(a) and

(c) show the first electron energies as a function of the magnetic field without an electric field and with an electric field of

kV/cm applied to the nanostructure, respectively. From the comparison between them, it is concluded that the electric field does not alter the main features of the electronic structure, but increases the energies associated with all states. As discussed in

Figure 4, the accumulation of states observed corresponds to the emergence of the ring states. Panels

(b) and

(d) correspond to a zoom of the shadow region in panels

(a) and

(c), respectively. The Aharanov-Bohm oscillations, typical of this kind of structure [

49], are observed.

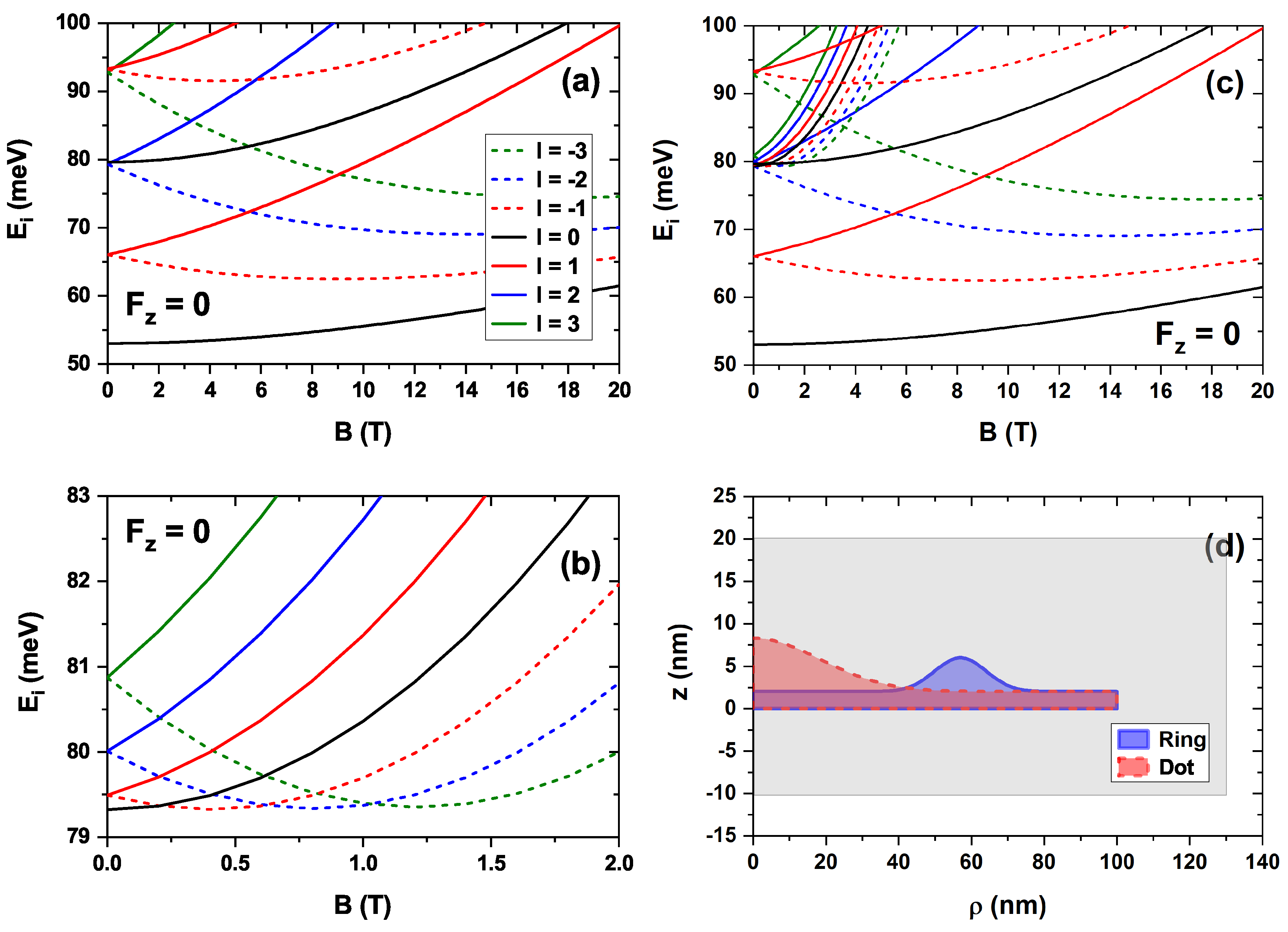

The energy spectrum observed in

Figure 5 can be better understood by decomposing the CDQR into a colloidal quantum dot (CQD) and a colloidal quantum ring (CQR) with the same wetting layer and dimensions as those shown in

Figure 1. The results of this decomposition are shown in

Figure 6, where panel

(a) corresponds to the CQD and panel

(b) corresponds to the CQR. The magnetic field sweep is selected according to panels

(a) and

(c) of

Figure 5. For simplicity, only the case with no external electric field applied to the nanostructure is analyzed. The superposition of panels

(a) and

(b) of

Figure 6 is shown in panel

(c), from which it is clear that the results obtained for the CQDR in

Figure 5 (a) and

(c) are consistent with the aforementioned decomposition of the nanostructure, where the coupling between its components causes them to interact and exhibit slight differences.

The second part of this work is devoted to calculating the EIT in the ladder configuration and LOAC for various values of the electric and magnetic fields.

To begin with,

Figure 7 illustrates the EIT calculation as a function of the probe field energy,

, and the LOAC as a function of the incident photon energy,

, for three different values of the electric field with and without a magnetic field applied to the nanostructure. Looking at panel

(a) of

Figure 7, it is straightforward that the two peaks associated with the EIT present a slightly appreciable blueshift as the absolute value of the electric field increases. Additionally, it is worth noting that the magnitude of the peaks also increases with the absolute value of the electric field. Finally, a particularity arises for the positive value of the electric field, where no EIT is observed. The latter is due to the term of the electric dipole moment matrix corresponding to the transitions involved in the ladder configuration,

i.e., between the ground and the first two excited states. This kind of EIT requires an allowed

transition and a nearly suppressed

transition. The panel

(a) of

Figure 6 illustrates how these matrix terms change their behavior at approximately

kV/cm, making zero the EIT for positive

F-values. The blueshift is justified by the energy levels features shown in

Figure 4 (a). When a magnetic field

T is applied together with the electric field, the EIT in the ladder configuration is observed for positive and negative values of the electric field. This is illustrated on panel

(b) of

Figure 7 and is justified by the dipole moment matrix terms displayed in

Figure 8(b). A slight blueshift occurs as the electric field ranges from positive to negative values. On the other hand, shadowed regions on panels

(a) and

(b) of

Figure 7 show the LOAC as a function of the incident photon energy, which is centered at the minimum located between the two EIT peaks. Again, the term of the zero electric dipole matrix for the transition

at positive electric field values is responsible for the zero LOAC in

(a).

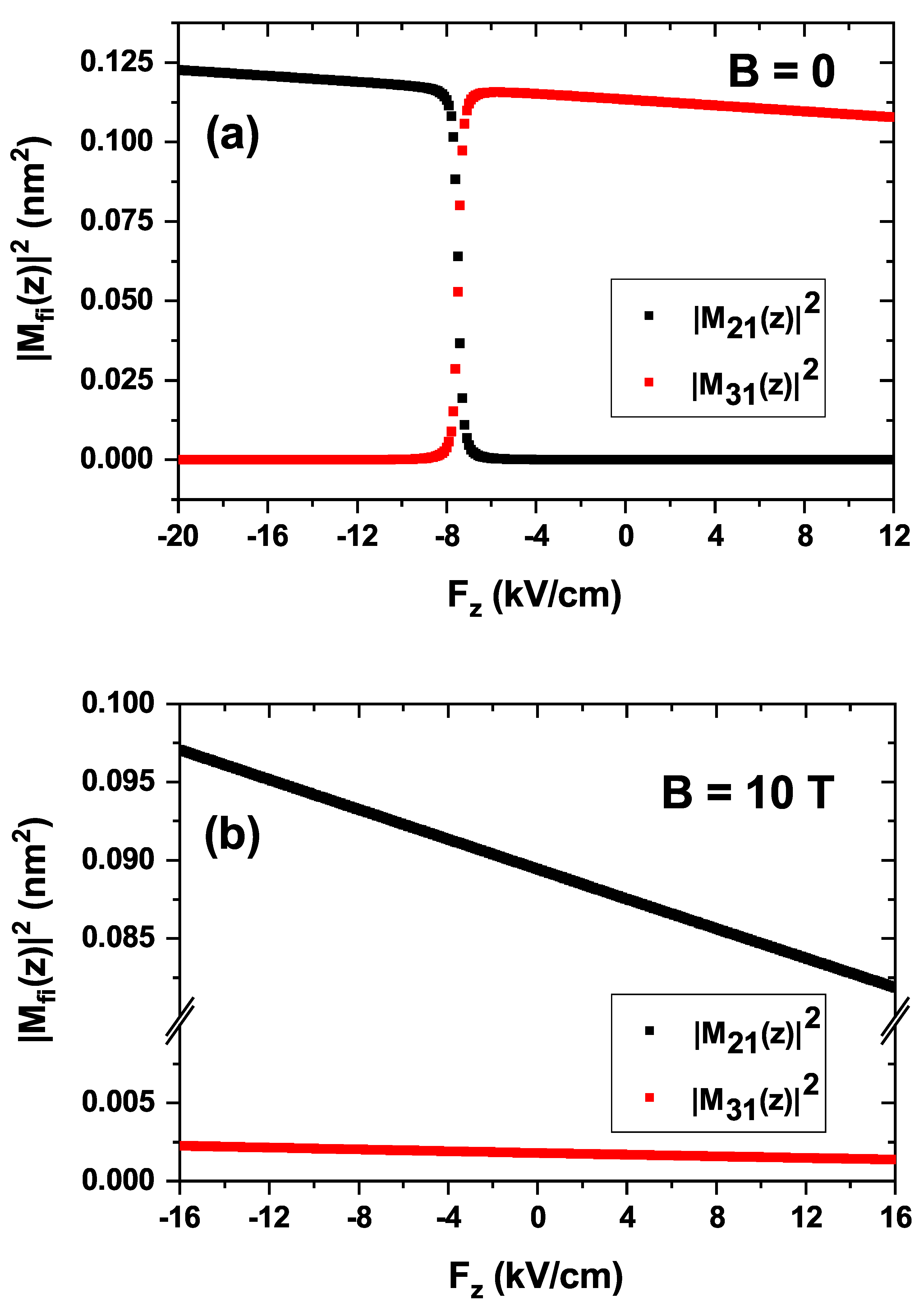

The behavior of the dipole matrix terms shown in

Figure 8, which directly impacts the EIT spectra in

Figure 7, is governed by the energy shifts of the electronic states under external fields. To illustrate this dependence,

Figure 9 plots the energies of the first three states with angular momentum

, denoted as

(where

is the principal quantum number and

), as a function of the applied electric field. Panel

(a) shows the case without a magnetic field (B = 0 T), while panel

(b) corresponds to a magnetic field (B = 10 T). The gray shaded areas indicate the specific electric field values used for the calculations in

Figure 7.

To better visualize the non-linear component of the Stark effect, which is crucial for determining the dipole moments, a dominant linear trend has been subtracted from the energy values. This data processing step allows the quadratic shifts and level anti-crossings which are otherwise obscured to be clearly observed, providing a direct insight into the physics governing the dipole matrix elements.

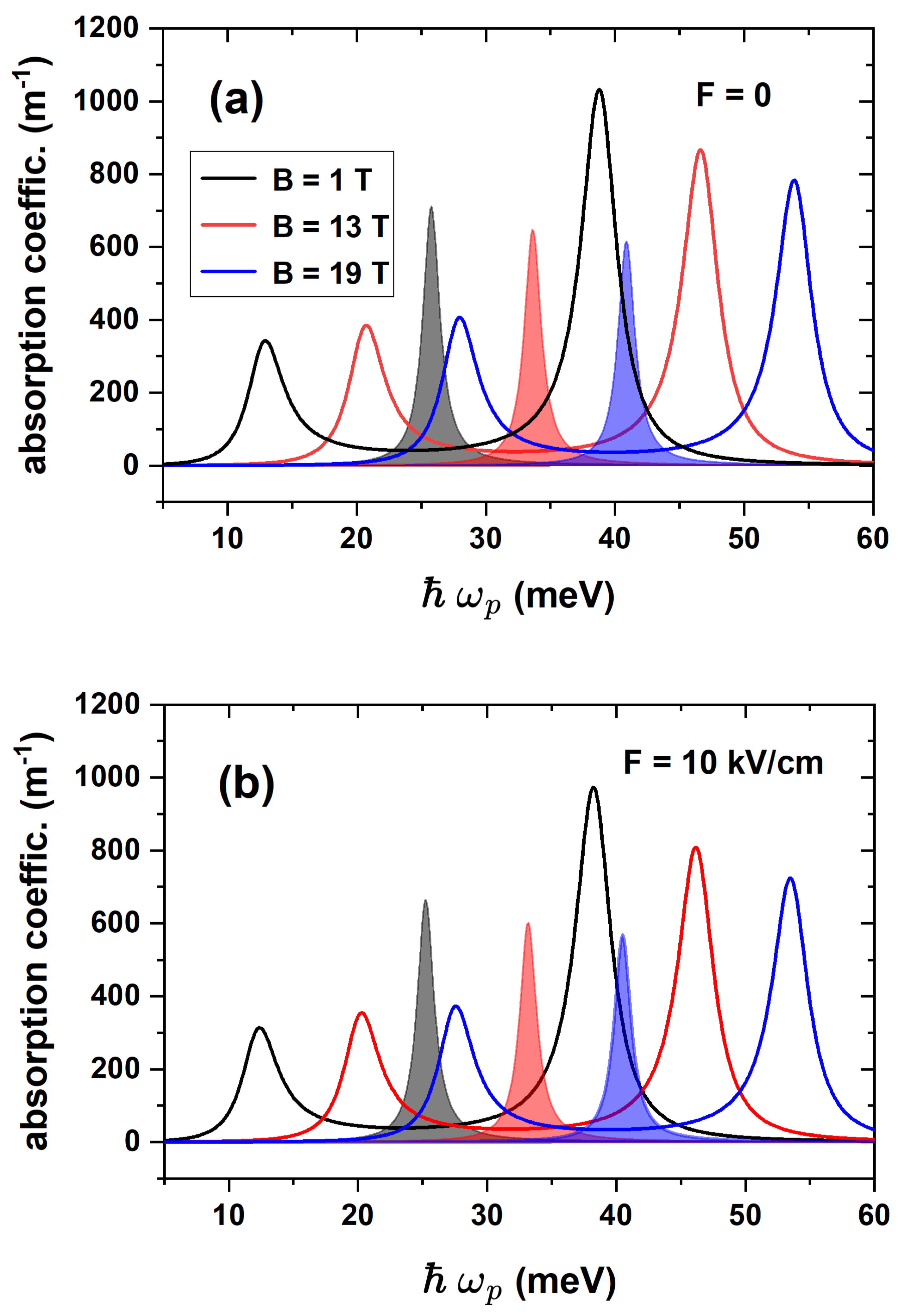

Figure 10 illustrates the dependence of the EIT and LOAC on the magnetic field, both in the absence and presence of an external electric field. Panel

(a) shows the results for a zero electric field, it is clear that the EIT peaks shift toward higher energies as the magnetic field strength increases and that the LOAC peaks undergo the same energy shift. Panel

(b) is homologous to

(a), but subjecting the system to an external electric field of

kV/cm. Comparing the EIT and LOAC peaks in both panels, it is straightforward that the effect of the electric field is practically negligible compared to the magnetic field, with only a slight variation in the magnitude and position of the peaks being observed. The magnitude of the EIT peaks decreases slightly between

(a) and

(b), and the shift of the peaks to lower energies in the presence of the electric field is practically imperceptible. The electric field causes once more the emergence of the LOAC peaks at lower energies and their magnitude to be slightly lower compared to the case without the electric field. All this is justified by the electronic structure shown in

Figure 5.

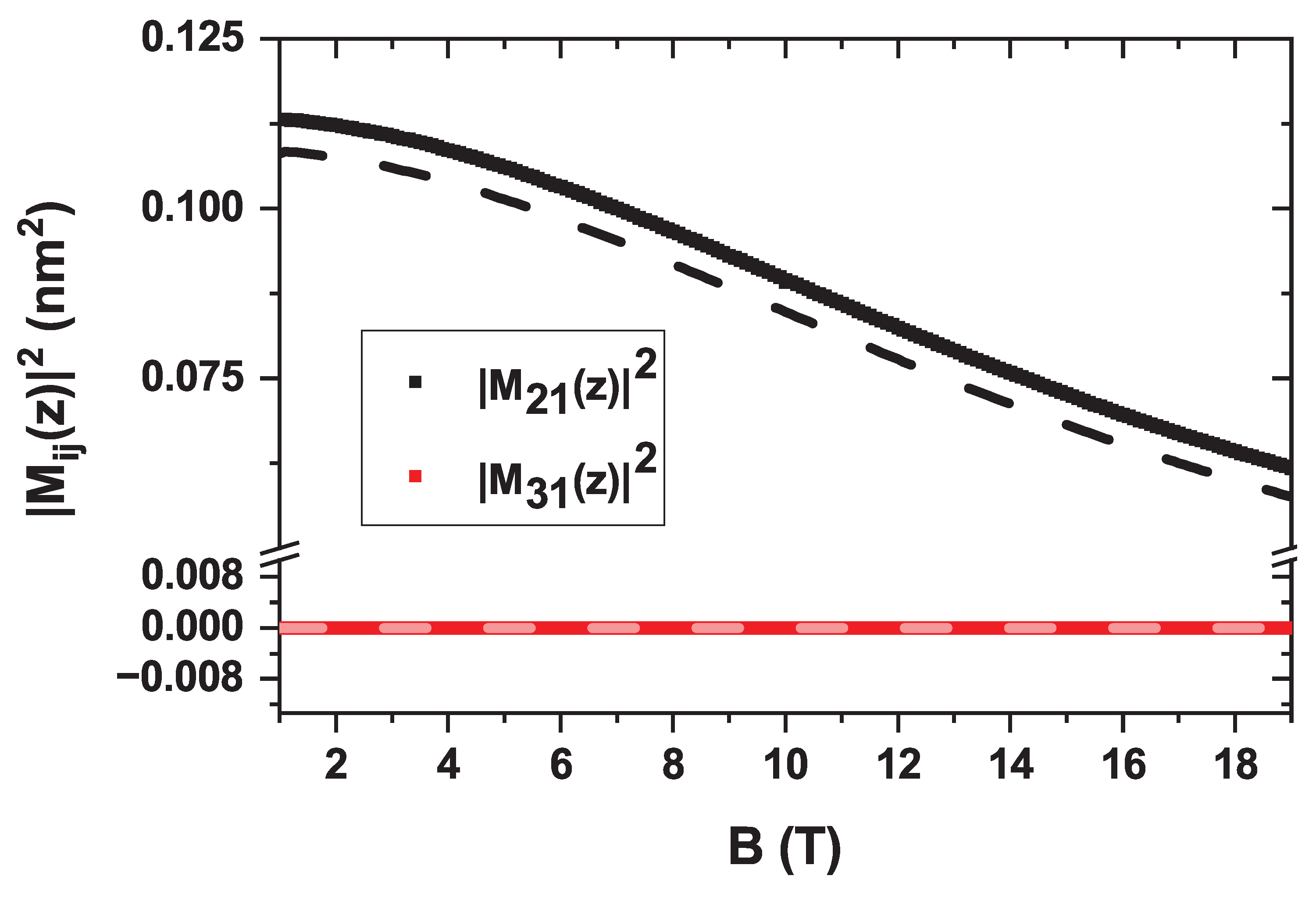

In contrast to

Figure 7, the non-zero EIT shown in

Figure 10 is explained by the behavior of the electric dipole matrix elements, which are depicted in

Figure 11. This figure displays the squared dipole moments for the

transition (

) and the

transition (

) as a function of the magnetic field. The results are shown for both a zero electric field (solid lines) and an external electric field of

kV/cm (dashed lines).

A direct comparison between the solid and dashed curves reveals that the influence of the electric field on the dipole moments is minimal, confirming that the system’s optical response is predominantly governed by the magnetic field. The most significant trend observed is the systematic decrease of the primary dipole matrix element,

, as the magnetic field strength increases. This behavior is a direct consequence of magnetic confinement. The applied Lorentz force radially compresses the electron wavefunctions, leading to a reduced spatial overlap for the dipole transition. Consequently, the magnitude of

is diminished, which directly suppresses the transition probability and, therefore, the overall absorption intensity [

50]. It is also noteworthy that the

element is nearly zero across the entire range, indicating that the

transition is dipole-forbidden for this light polarization, consistent with the selection rules.

Author Contributions

R. V. H. Hahn: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing - Review and Editing, Visualization. A. S. Giraldo-Neira: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing - Review and Editing, Visualization. J. A. Vinasco: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing - Review and Editing, Visualization. J. A. Gil-Corrales: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing - Review and Editing, Visualization. A. L. Morales: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Writing - Review and Editing, Visualization. C. A. Duque: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Writing - Review and Editing, Visualization.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the As three-dimensional CQDR geometry (a), together with a -plane slice of the CQDR and the cylindrical boundary for visualization of the main dimensions of the heterostructure (b). The reference system and the directions of the externally applied electric and magnetic field are also depicted.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the As three-dimensional CQDR geometry (a), together with a -plane slice of the CQDR and the cylindrical boundary for visualization of the main dimensions of the heterostructure (b). The reference system and the directions of the externally applied electric and magnetic field are also depicted.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the three-level system in a ladder or cascade configuration interacting with control and probe electromagnetic fields of frequencies and , respectively. For clarity, the detuning is also depicted.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the three-level system in a ladder or cascade configuration interacting with control and probe electromagnetic fields of frequencies and , respectively. For clarity, the detuning is also depicted.

Figure 3.

First ten electron eigenenergies in the GaAs/AlGaAs CQDR structure obtained by the 2D-axisymmetric model (red), the adiabatic approximation (black), and the three-dimensional model (green).

Figure 3.

First ten electron eigenenergies in the GaAs/AlGaAs CQDR structure obtained by the 2D-axisymmetric model (red), the adiabatic approximation (black), and the three-dimensional model (green).

Figure 4.

Energy variation of the first low-lying electron states in the absence of magnetic field (a) and with an externally applied magnetic field of T along the z-axis (b), as a function of the external electric field, applied along the z-direction. The negative values of the electric field are related to the negative z-axis.

Figure 4.

Energy variation of the first low-lying electron states in the absence of magnetic field (a) and with an externally applied magnetic field of T along the z-axis (b), as a function of the external electric field, applied along the z-direction. The negative values of the electric field are related to the negative z-axis.

Figure 5.

Energy spectrum as a function of the magnetic field intensity for different values of the quantum number l. The calculations correspond to zero electric field (a) and kV/cm (c). A zoom of the gray-highlighted energy region in (a) and (c) for magnetic field values between 0 and 2 T is also presented in panels (b) and (d), respectively. In all cases, the magnetic field is applied along the positive z-direction.

Figure 5.

Energy spectrum as a function of the magnetic field intensity for different values of the quantum number l. The calculations correspond to zero electric field (a) and kV/cm (c). A zoom of the gray-highlighted energy region in (a) and (c) for magnetic field values between 0 and 2 T is also presented in panels (b) and (d), respectively. In all cases, the magnetic field is applied along the positive z-direction.

Figure 6.

Energy spectrum as a function of the magnetic field intensity for different values of the quantum number l as a result of the decomposition of the complete structure in the quantum dot (a) and the quantum ring (b). The superposition of the results shown in (a) and (b) is shown in panel (c). A schematic representation of the nanostructures is shown in (d). The calculations correspond to a zero electric field. In all cases, the magnetic field is applied along the positive z-direction.

Figure 6.

Energy spectrum as a function of the magnetic field intensity for different values of the quantum number l as a result of the decomposition of the complete structure in the quantum dot (a) and the quantum ring (b). The superposition of the results shown in (a) and (b) is shown in panel (c). A schematic representation of the nanostructures is shown in (d). The calculations correspond to a zero electric field. In all cases, the magnetic field is applied along the positive z-direction.

Figure 7.

Electromagnetically induced transparency (solid lines) in the ladder configuration associated with the first three energy levels for three different values of the electric field with zero magnetic field (a) and T (b) as a function of the probe field energy. The corresponding values of the linear absorption coefficient in terms of the incident-photon energy are represented by the shaded regions. For visualization, the absorption curves have been divided by 3. In all cases, the magnetic field is applied along the positive z-direction.

Figure 7.

Electromagnetically induced transparency (solid lines) in the ladder configuration associated with the first three energy levels for three different values of the electric field with zero magnetic field (a) and T (b) as a function of the probe field energy. The corresponding values of the linear absorption coefficient in terms of the incident-photon energy are represented by the shaded regions. For visualization, the absorption curves have been divided by 3. In all cases, the magnetic field is applied along the positive z-direction.

Figure 8.

Squared absolute value of reduced () electric dipole moments involved in the calculation of the electromagnetically induced transparency, and for zero magnetic field (a) and under the effect of a T magnetic field (b), as functions of the externally applied electric field . The values correspond to the ground (1) and first two excited (2, 3) states and are obtained for linearly polarized light in the z-direction. The magnetic field is applied along the z-direction.

Figure 8.

Squared absolute value of reduced () electric dipole moments involved in the calculation of the electromagnetically induced transparency, and for zero magnetic field (a) and under the effect of a T magnetic field (b), as functions of the externally applied electric field . The values correspond to the ground (1) and first two excited (2, 3) states and are obtained for linearly polarized light in the z-direction. The magnetic field is applied along the z-direction.

Figure 9.

Energy of the first three

states (

,

, and

) as a function of the applied electric field F, calculated for

(a) a zero magnetic field (B = 0 T) and

(b) a magnetic field of B = 10 T. Note that a dominant linear component has been subtracted from the plotted energy values to emphasize the non-linear Stark effect. The gray shaded areas correspond to the electric field values used in

Figure 7.

Figure 9.

Energy of the first three

states (

,

, and

) as a function of the applied electric field F, calculated for

(a) a zero magnetic field (B = 0 T) and

(b) a magnetic field of B = 10 T. Note that a dominant linear component has been subtracted from the plotted energy values to emphasize the non-linear Stark effect. The gray shaded areas correspond to the electric field values used in

Figure 7.

Figure 10.

Electromagnetically induced transparency in the cascade configuration and the corresponding values of the linear absorption coefficient associated with the three first energy levels for three different values of the magnetic field with zero electric field (a) and kV/cm (b) in terms of the incident photon energy. In all cases, the magnetic field is applied along the positive z-direction.

Figure 10.

Electromagnetically induced transparency in the cascade configuration and the corresponding values of the linear absorption coefficient associated with the three first energy levels for three different values of the magnetic field with zero electric field (a) and kV/cm (b) in terms of the incident photon energy. In all cases, the magnetic field is applied along the positive z-direction.

Figure 11.

Squared electric dipole matrix elements, , as a function of the applied magnetic field B. The figure shows the elements for the transitions from the ground state () to the first two excited states, (black) and (red). Solid lines correspond to a zero electric field (), while dashed lines represent the results under an external electric field of kV/cm. Calculations assume linearly polarized light along the z-direction.

Figure 11.

Squared electric dipole matrix elements, , as a function of the applied magnetic field B. The figure shows the elements for the transitions from the ground state () to the first two excited states, (black) and (red). Solid lines correspond to a zero electric field (), while dashed lines represent the results under an external electric field of kV/cm. Calculations assume linearly polarized light along the z-direction.