Submitted:

07 August 2025

Posted:

07 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

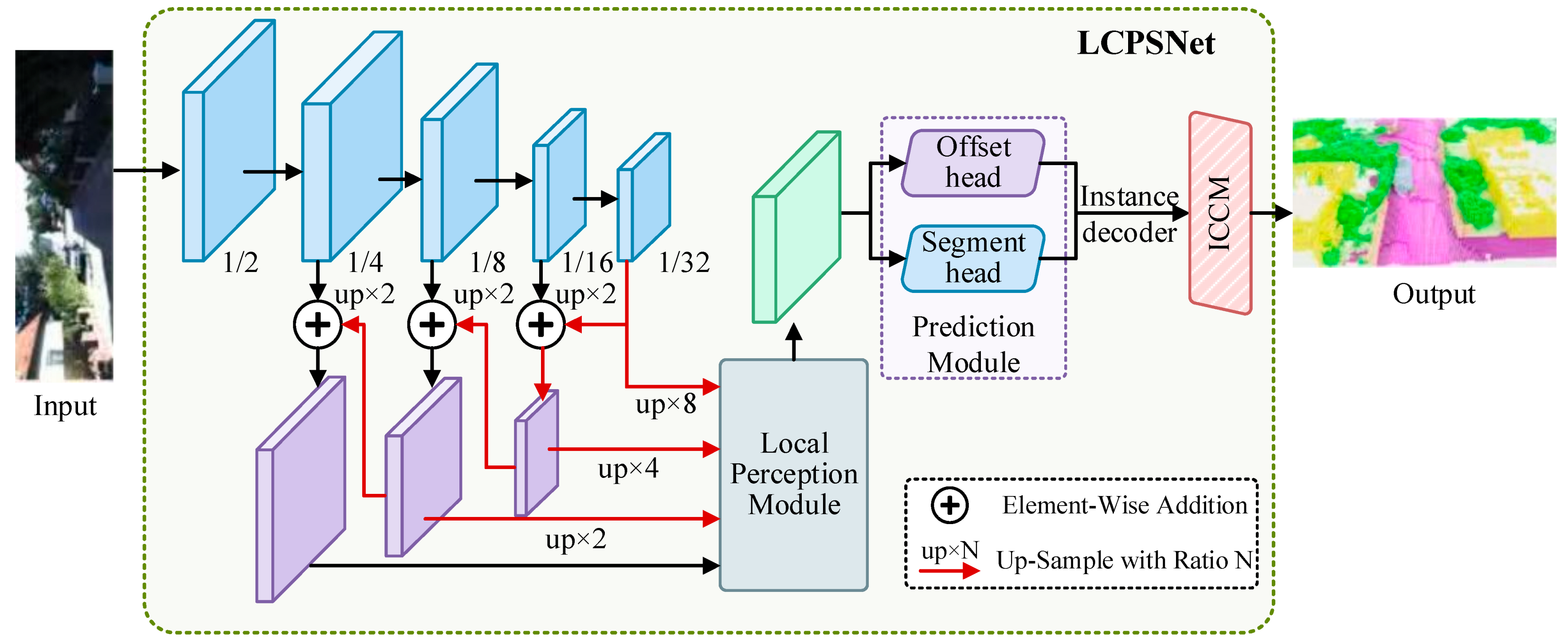

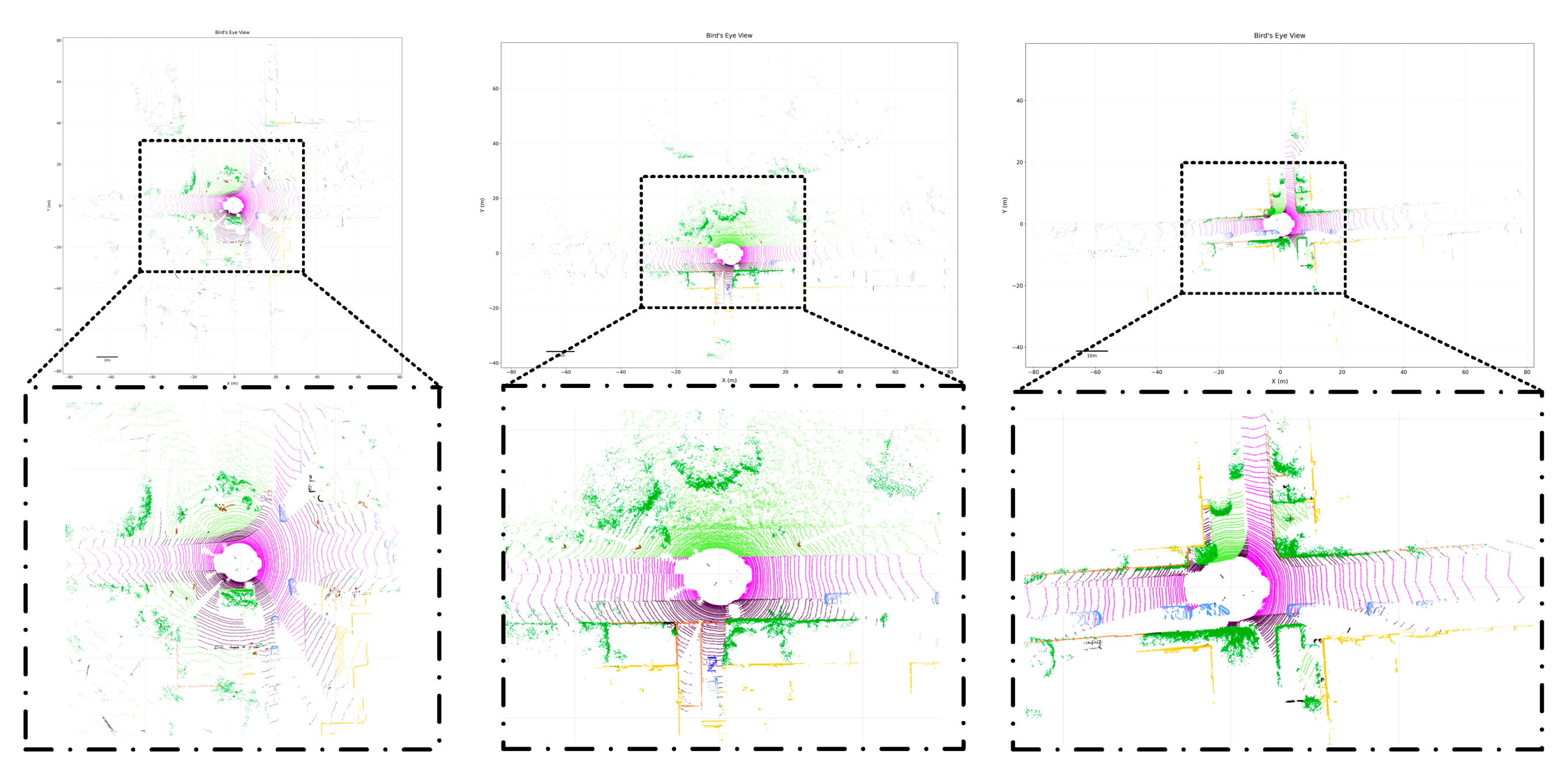

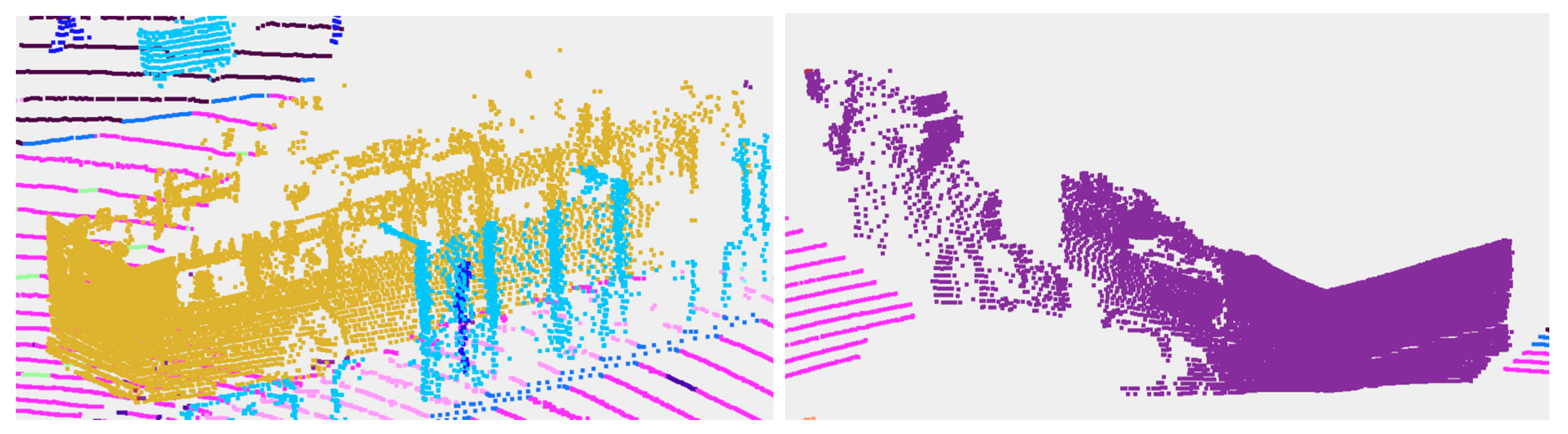

LiDAR and its point cloud data are crucial visual sensors in smart driving cars for sensing the surrounding environment and achieving high accuracy localization. Compared to semantic segmentation, point cloud instance segmentation is a more complicated task. For autonomous driving systems, precise instance segmentation results can offer a more detailed understanding of the scene. The point cloud data is sparse and irregular, and the point cloud density varies with the distance from the sensor. In this paper, a LiDAR channel-aware point segmentation network (LCPSNet) is proposed to address the above problems. Given the distance-dependent sparsity and drastic scale variation of LiDAR, we adopt a top-down FPN. High-level features are progressively upsampled and summed element-wise with the corresponding shallow layers. Beyond this standard fusion, the fused features at 1/16, 1/8, and 1/4 are resampled to a common BEV/polar grid. These aligned features are then fed to the LPM to perform cross-scale, position-dependent weighting and modulation at the same spatial locations. The Local Perception Module (LPM) uses global spatial information to guide, while preserving, attention to group (scale) differences. Position-by-position weighting and re-fusion of local features of each group on the same grid. Enhances both intra-object and tele-context while suppressing cross-instance interference. The Inter-Channel Correlation Module (ICCM) uses a ball query to define local feature regions, modeling the spatio-temporal and channel information of the LiDAR point cloud jointly within the same module. And the inter-channel similarity matrix is computed to remove redundant features and highlight valid features. Experiments on SemanticKITTI and Waymo datasets verify that the two modules effectively improve the local feature and global semantic consistency modeling capabilities, respectively. The PQ of LCPSNet on the SemanticKITTI dataset is 70.9, and the mIoU is 77.1, and the instance segmentation performance exceeds the existing mainstream methods and reaches SOTA.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

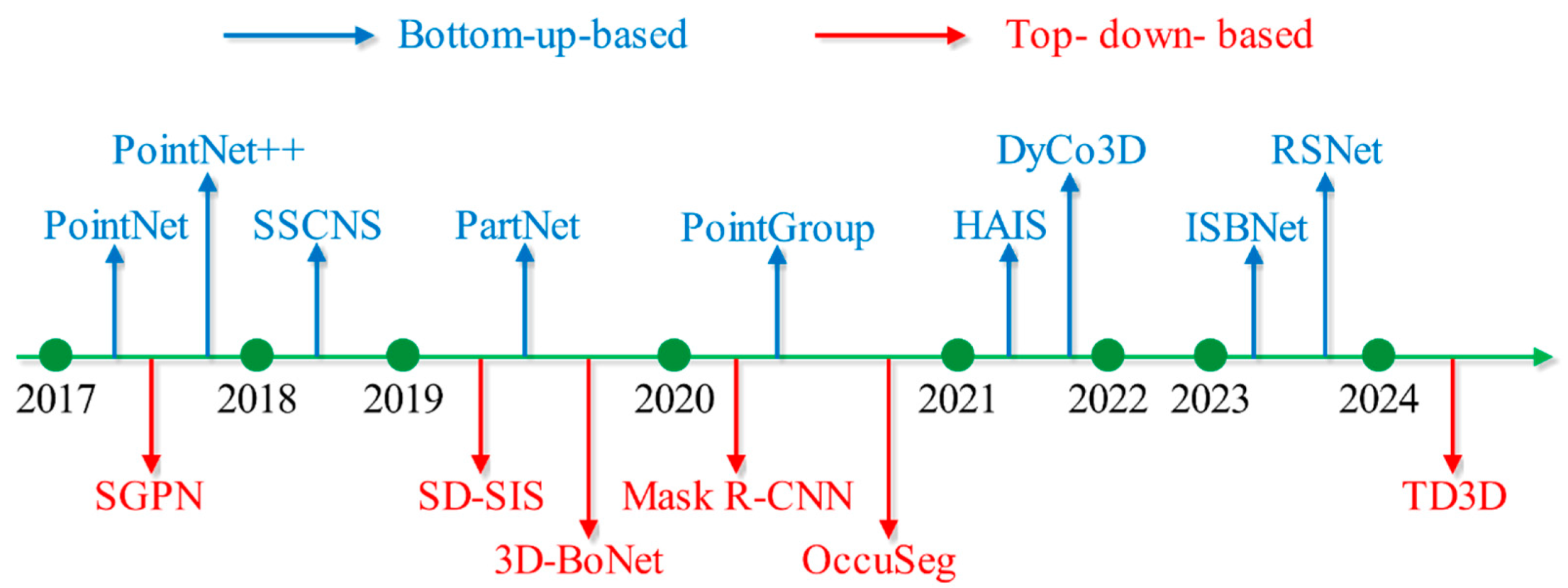

2. Related Work

2.1. Top-Down-Based Methods

2.2. Bottom-Up-Based Methods

3. Methods

3.1. The Overall Structure of the LiDAR Channel-Aware Point Segmentation Network

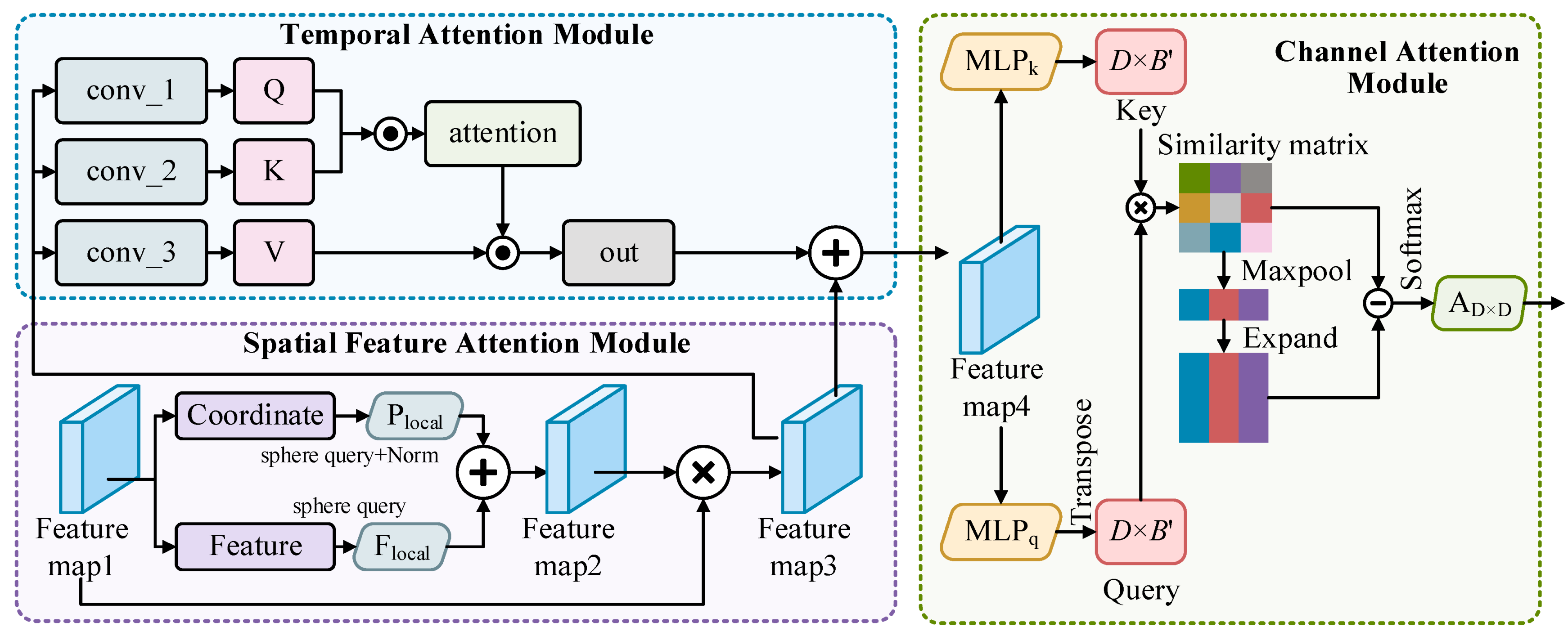

3.2. Local Perception Module

| Algorithm 1 Local Perception Module |

| 1 Input F 2 F’ = Concat(F) 3 F1 = Conv(F’) 4 Global Spatial Attention: 5 F2 = MaxPooling(F1) 6 F2 ’ = ConvTanh(F2) 7 F2 ’’ = ConvTanh(F2’) 8 F3 = Expand(F2 ’’) + F2 9 output = ConvTanh(ConvTanh(F3)) 10 Return output 11 expanded_weights = Expand(output) 12 fused =WiseProduct(F’, expanded_weights) 13 Output fused |

3.3. Inter-Channel Correlation Module Based on Channel Similarity

3.4. Cross Entropy Loss Function

4. Experiments

4.1. Datasets and Metrics

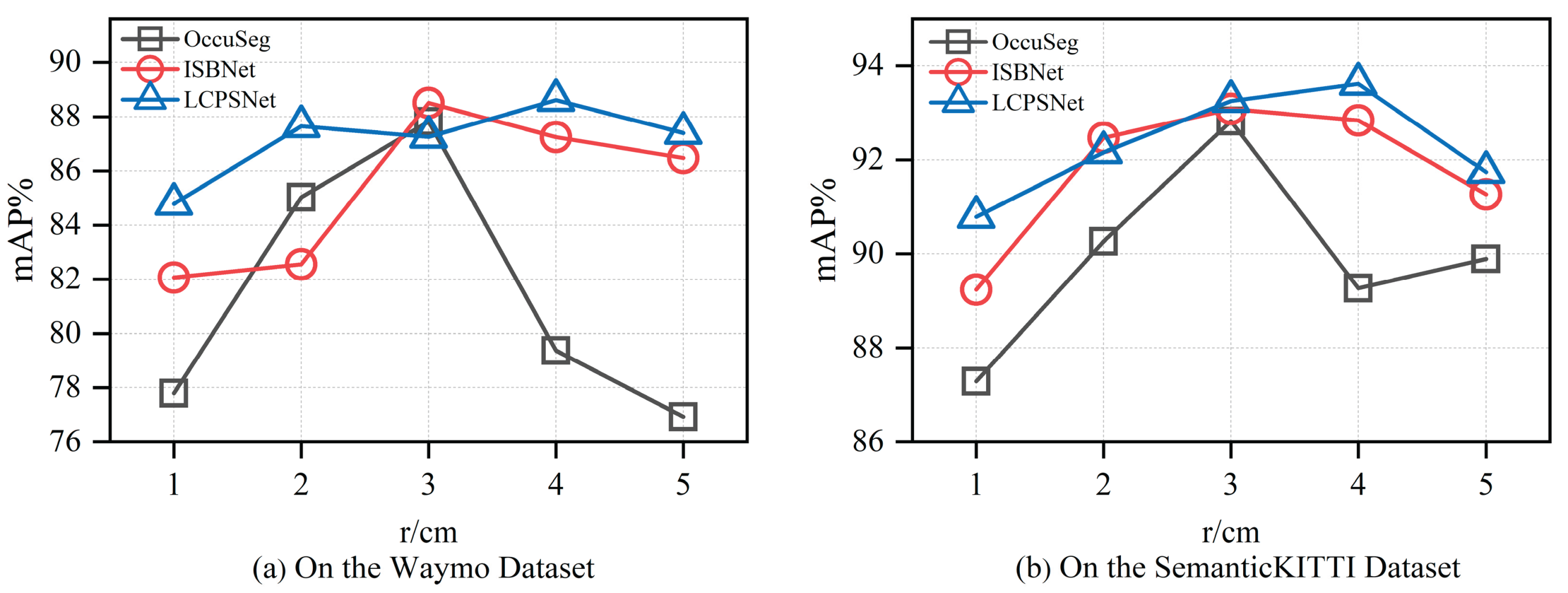

4.2. Ablation Experiments

4.3. Comparison Experiments

5. Conclusions

References

- Huang X S, Mei G F, Zhang J, et al. A comprehensive survey on point cloud registration [EB/OL]. (2021-03-03) [2024-12-12]. https://arxiv.org/abs/2103.02690v2.

- Zeng Y H, Jiang C H, Mao J G, et al. CLIP2: contrastive language-image-point pretraining from real world point cloud data[C]//2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), June 17-24, 2023, Vancouver, BC, Canada. New York: IEEE Press, 2023: 15244-15253.

- Marinos, V., Farmakis, I., Chatzitheodosiou, T., Papouli, D., Theodoropoulos, T., Athanasoulis, D., & Kalavria, E. (2025). Engineering Geological Mapping for the Preservation of Ancient Underground Quarries via a VR Application. Remote Sensing, 17(3), 544.

- Qian R, Lai X, Li X R. 3D object detection for autonomous driving: a survey[J]. Pattern Recognition, 2022, 130: 108796.

- Lee S, Lim H, Myung H. Patchwork: fast and robust ground segmentation solving partial under-segmentation using 3D point cloud[C]//2022 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), October 23-27, 2022, Kyoto, Japan. New York: IEEE Press, 2022: 13276-13283.

- Xiao A R, Yang X F, Lu S J, et al. FPS-Net: a convolutional fusion network for large-scale LiDAR point cloud segmentation[J]. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing, 2021, 176: 237-249.

- Hafiz A M, Bhat G M. A survey on instance segmentation: state of the art[J]. International Journal of Multimedia Information Retrieval, 2020, 9(3): 171-189.

- Guo Y L, Wang H Y, Hu Q Y, et al. Deep learning for 3D point clouds: a survey[J]. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 2021, 43(12): 4338-4364.

- Lu B, Liu Y W, Zhang Y H, et al. Point cloud segmentation algorithm based on density awareness and self-attention mechanism[J]. Laser & Optoelectronics Progress, 2024, 61(8): 0811004.

- Ai D, Zhang X Y, Xu C, et al. Advancements in semantic segmentation methods for large-scale point clouds based on deep learning[J]. Laser & Optoelectronics Progress, 2024, 61(12): 1200003.

- Zhang K, Zhu Y W, Wang X H, et al. Three-dimensional point cloud semantic segmentation network based on spatial graph convolution network[J]. Laser & Optoelectronics Progress, 2023, 60(2): 0228007.

- Xu X. Research on 3D instance segmentation method for indoor scene[D]. Daqing: Northeast Petroleum University, 2023: 12-13.

- Cui L Q, Hao S Y, Luan W Y. Lightweight 3D point cloud instance segmentation algorithm based on Mamba[J]. Computer Engineering and Applications, 2025, 61(8): 194-203.

- Wang W Y, Yu R, Huang Q G. SGPN: similarity group proposal network for 3D point cloud instance segmentation [EB/OL]. (2017-11-23) [2024-12-12]. arXiv:1711.08588.

- Hou J, Dai A, Nießner M. 3D-SIS: 3D semantic instance segmentation of RGB-D scans[C]//2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), June 15-20, 2019, Long Beach, CA, USA. New York: IEEE Press, 2019: 4416-4425.

- Lin K H, Zhao H M, Lv J J, et al. Face detection and segmentation based on improved mask R-CNN[J]. Discrete Dynamics in Nature and Society, 2020, 2020(1): 9242917.

- Yang B, Wang J, Clark R, et al. Learning object bounding boxes for 3D instance segmentation on point clouds[C]//Proceedings of the 33rd Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, 2019: 1-10.

- Han L, Zheng T, Lan X, et al. OccuSeg: occupancy aware 3D instance segmentation[C]//Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2020: 2937-2946.

- Kolodiazhnyi M, Vorontsova A, Konushin A, et al. Top-down beats bottom-up in 3D instance segmentation[C]//2024 IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), January 3-8, 2024, Waikoloa, HI, USA. New York: IEEE Press, 2024: 3554-3562.

- Charles R Q, Li Y, Hao S, et al. PointNet++: deep hierarchical feature learning on point sets in a metric space[EB/OL]. (2017-06-07) [2024-12-12]. https://arxiv.org/abs/1706.02413.

- Charles R Q, Hao S, Mo K C, et al. PointNet: deep learning on point sets for 3D classification and segmentation[C]//2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), July 21-26, 2017, Honolulu, HI, USA. New York: IEEE Press, 2017: 77-85.

- Mo K C, Zhu S L, Chang A X, et al. PartNet: a large-scale benchmark for fine-grained and hierarchical part level 3D object understanding[C]//2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), June 15-20, 2019, Long Beach, CA, USA. New York: IEEE Press, 2019: 909-918.

- Graham B, Engelcke M, Maaten V D L. 3D semantic segmentation with submanifold sparse convolutional networks[C]//Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2018: 9224-9232.

- Jiang L, Zhao H, Shi S, et al. PointGroup: dual-set point grouping for 3D instance segmentation[C]//Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2020: 4866-4875.

- Chen S Y, Fang J M, Zhang Q, et al. Hierarchical aggregation for 3D instance segmentation[EB/OL]. (2021-08-06)[2024-12-12]. arXiv:2108.02350.

- He T, Shen C, Hengel V D A. DyCO3D: robust instance segmentation of 3D point clouds through dynamic convolution[C]//Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2021: 354-363.

- Ngo T D, Hua B S, Nguyen K. ISBNet: a 3D point cloud instance segmentation network with instance-aware sampling and box-aware dynamic convolution[C]//2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), June 17-24, 2023, Vancouver, BC, Canada. New York: IEEE Press, 2023: 13550-13559.

- Huang X S, Mei G F, Zhang J, et al. A comprehensive survey on point cloud registration [EB/OL]. (2021-03-03)[2024-12-12]. https://arxiv.org/abs/2103.02690v2.

- Behley J, Garbade M, Milioto A, et al. Semantickitti: A dataset for semantic scene understanding of lidar sequences[C]//Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision. 2019: 9297-9307.

- Sun P, Kretzschmar H, Dotiwalla X, et al. Scalability in perception for autonomous driving: Waymo open dataset[C]//IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. New York: IEEE, 2020: 2446-2454.

| Combination | LPM | ICCM | mIoU (%) | PQ |

| Baseline | × | × | 69.9 | 61.4 |

| LPM | √ | × | 72.4 | 64.8 |

| ICCM | × | √ | 72.9 | 65.2 |

| LCPSNet (Ours) | √ | √ | 77.1 | 70.9 |

| Category | Baseline | LPM | ICCM | LCPSNet(Ours) |

| car | 94.3 | 94.7 | 95 | 98.2 |

| bicy | 68.3 | 69.3 | 68.5 | 72.4 |

| moto | 70.8 | 72.3 | 72.8 | 75.7 |

| truc | 59.1 | 60.8 | 60.2 | 63.9 |

| o.veh | 69.4 | 71 | 71.8 | 74.5 |

| ped | 73.7 | 75.8 | 76.1 | 79.3 |

| b.list | 70.5 | 71.3 | 71.5 | 75.2 |

| m.list | 56.1 | 58.1 | 58.1 | 60.9 |

| road | 88.2 | 89.2 | 89.2 | 92.9 |

| park | 69.9 | 72 | 71.9 | 74.4 |

| walk | 75.6 | 76.4 | 76.8 | 79.7 |

| o.gro | 42.5 | 44 | 43.8 | 46.5 |

| build | 89.9 | 90.1 | 91 | 93.8 |

| fenc | 67.4 | 69.7 | 69.5 | 72.9 |

| veg | 83 | 84.8 | 85.3 | 87.8 |

| trun | 72.4 | 73 | 73.6 | 76.6 |

| terr | 68.1 | 70.3 | 69.6 | 73.4 |

| pole | 63.9 | 65.1 | 66.1 | 68.7 |

| sign | 64.9 | 65.6 | 65.9 | 68.9 |

| mIoU | 69.9 | 72.4 | 72.9 | 77.1 |

| Combination | LPM | ICCM | mIoU (%) |

| Baseline | × | × | 62.7 |

| LPM | √ | × | 66.9 |

| ICCM | × | √ | 67.5 |

| LCPSNet (Ours) | √ | √ | 70.4 |

| Waymo | r (cm) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| OccuSeg | 77.79 | 85.02 | 87.81 | 79.37 | 76.93 | |

| ISBNet | 82.07 | 82.55 | 88.5 | 87.24 | 86.47 | |

| LCPSNet | 84.78 | 87.64 | 87.25 | 88.61 | 87.39 | |

| SemanticKITTI | r (cm) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| OccuSeg | 87.29 | 90.26 | 92.82 | 89.26 | 89.89 | |

| ISBNet | 89.24 | 92.47 | 93.08 | 92.84 | 91.26 | |

| LCPSNet | 90.78 | 92.16 | 93.25 | 93.61 | 91.74 |

| Method | PQ | mIoU (%) |

| PointNet | 17.5 | 18.2 |

| PointNet++ | 20.8 | 23.4 |

| SSCNS | 35.2 | 37.9 |

| PolarNet | 54.3 | 55.7 |

| PointGroup | 41.7 | 42.5 |

| Cylinder3D | 66.8 | 68.9 |

| AF2S3Net | 64.9 | 69.7 |

| RangeFormer | 64.1 | 73.6 |

| SDSeg3D | 62.6 | 70.4 |

| SpAtten | 70.5 | 76.8 |

| LCPSNet (Ours) | 70.9 | 77.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).