Submitted:

06 August 2025

Posted:

07 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Ethical Considerations

2.2. Patient Selection

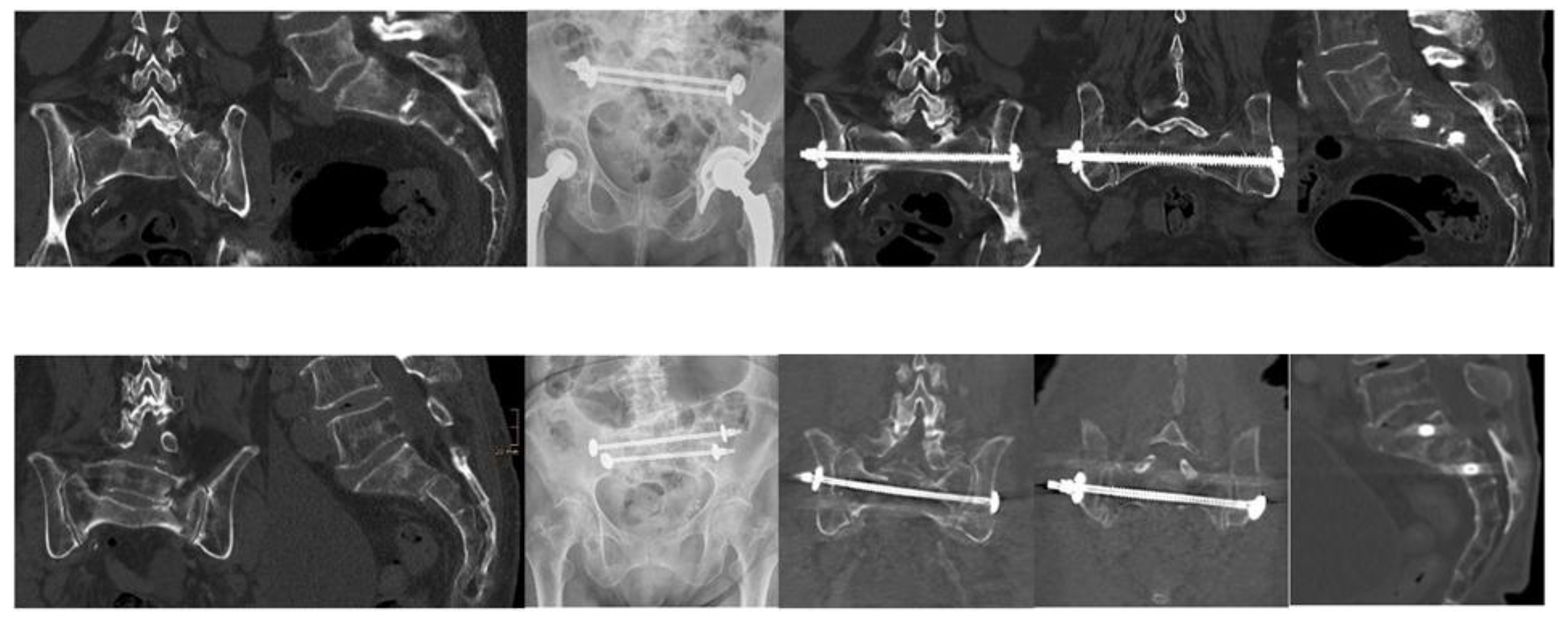

2.3. Surgical Technique

2.4. Data Collection and Variables

2.5. Postoperative Care and Rehabilitation

2.6. Follow-Up Protocol and Radiological Assessment

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Demographics and Baseline Characteristics

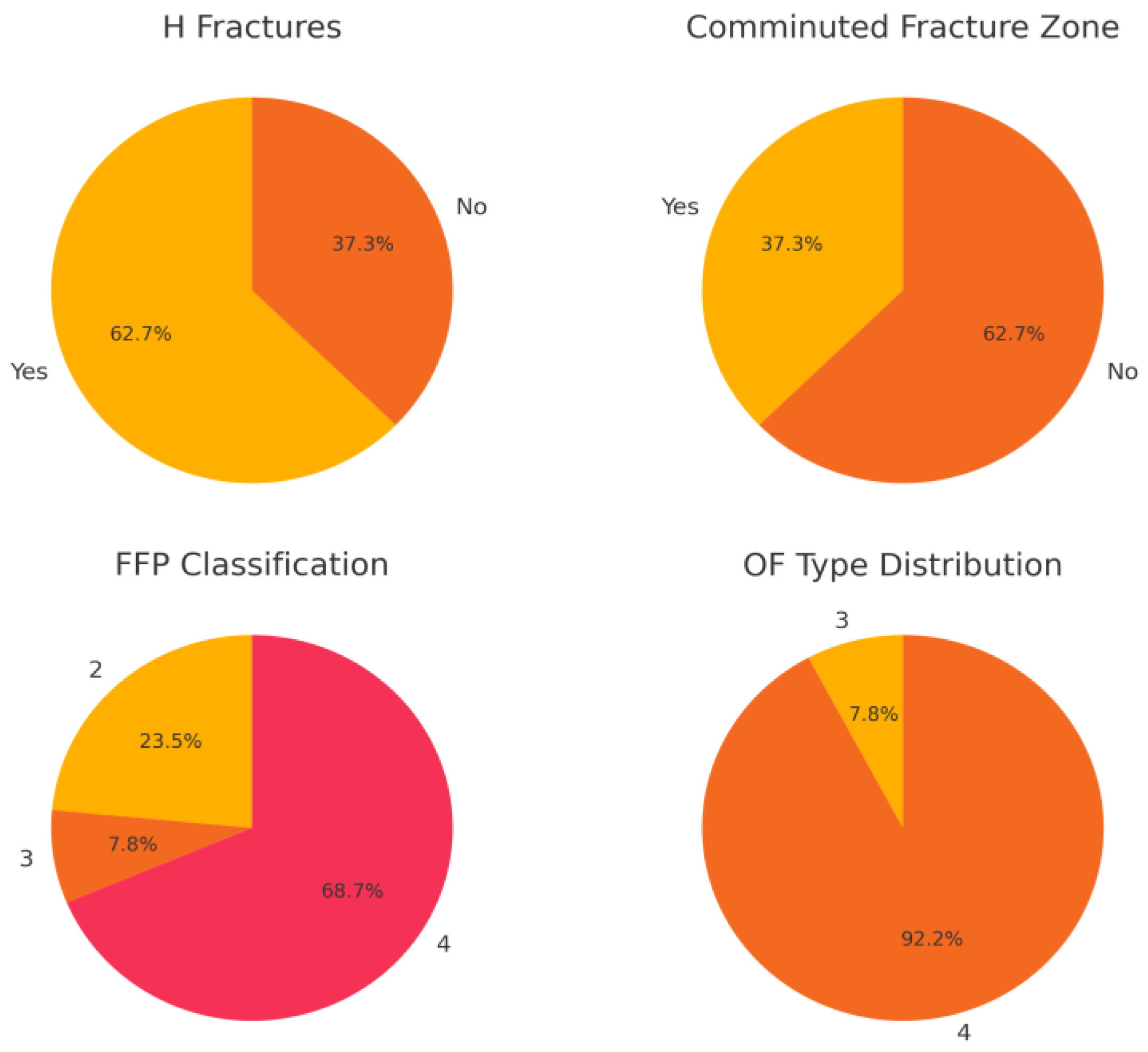

3.2. Fracture Classification and Radiographic Findings

3.3. Surgical Management and Hospital Course

3.4. Postoperative Mobility and Rehabilitation

3.5. Follow-Up Pain and Implant Integrity

| Parameter | Value |

| Demographics Age, median (range) Female, % Male, % |

|

| 77.4 (66-88) years 88.2 11.8 | |

| Fracture Classification FFP Type 4, % FFP Type 2, % FFP Type 3, % OF Type 4, % OF Type 3, % Comminuted zone, % H-type Fractures, % |

|

| 68.7 23.5 7.8 92 8 37.25 62.7 | |

| Operation time, median (range) Hospital stay, median (range) Loosening rate, % |

70.3 minutes (41-110) |

| 9.2 days (5-14)0 | |

| Mobilty and Pain Walker at discharge, % High Walker at discharge Crutches at discharge Bedridden No walking aids Pain level at 3 months, mean (0-10) Pain level at 12 months, mean (0-10) |

64.71 11.76 19.61 1.96 1.96 1.9 1.96 1.09 |

4. Discussion

4.1. Advantages of TSB Fixation

4.2. Reconsidering Morphology-Driven Decision-Making

4.3. Comparison to Literature

4.4. Health-Economic Considerations

4.5. Limitations

4.6. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Abbreviations

| SPF | Spinopelvic Fixation |

| TSB | Transsacral Bar |

| SIFs | Osteoporotic Sacral Insufficiency Fractures |

| FFP | Fragility Fractures of Pelvis |

| OF | Osteoporotic Fractures |

References

- Rommens PM, Hofmann A. Comprehensive classification of fragility fractures of the pelvic ring: recommendations for surgical treatment. Injury. 2013;44(12):1733-1744. [CrossRef]

- Höch A, Pieroh P, Henkelmann R, Josten C, Böhme J. Outcome and 2-year survival rate in elderly patients with lateral compression fractures of the pelvis. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil. 2017;8(1):3-9. [CrossRef]

- Nuber S, Schubert A, Fürmetz J, Pflug A, Böcker W, Kammerlander C, Böcker W, Nüchtern JV. Midterm follow-up of elderly patients with fragility fractures of the pelvis: a prospective cohort study comparing operative and non-operative treatment according to a therapeutic algorithm. Injury. 2022;53(2):496-505. [CrossRef]

- Mendel T, Schenk P, Ullrich BW, Hofmann GO, Goehre F, Schwan S, Schütz T, Arand C. Mid-term outcome of bilateral fragility fractures of the sacrum after bisegmental transsacral stabilization versus spinopelvic fixation: a prospective study of two minimally invasive fixation constructs. Bone Joint J. 2021;103-B(3):462-468. [CrossRef]

- Gänsslen A, Hüfner T, Krettek C. Percutaneous iliosacral screw fixation of unstable pelvic injuries by conventional fluoroscopy. Oper Orthop Traumatol. 2006;18(3):225-244. [CrossRef]

- Rommens PM, Boudissa M, Krämer S, Kisilak M, Hofmann A, Wagner D. Operative treatment of fragility fractures of the pelvis: a critical analysis of 140 patients. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2022;48(4):2881-2896. [CrossRef]

- Eckardt H, Egger A, Hasler RM, Zech CJ, Vach W, Suhm N, Morgenstern M, Saxer F. Good functional outcome in patients suffering fragility fractures of the pelvis treated with percutaneous screw stabilisation: assessment of complications and factors influencing failure. Injury. 2017;48(12):2717-2723. [CrossRef]

- Wagner D, Kisilak M, Porcheron G, Krämer S, Mehling I, Hofmann A, Rommens PM. Trans-sacral bar osteosynthesis provides low mortality and high mobility in patients with fragility fractures of the pelvis. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):14201. [CrossRef]

- Peng Y, Zhang G, Zhang S, Ji X, Li J, Du C, Zhao W, Zhang L. Biomechanical study of transsacral-transiliac screw fixation versus lumbopelvic fixation and bilateral triangular fixation for “H”- and “U”-type sacrum fractures with traumatic spondylopelvic dissociation: a finite element analysis study. J Orthop Surg Res. 2021;16(1):428. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).