Submitted:

06 August 2025

Posted:

07 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Instrumentation

2.2. Calibration Standards

2.3. Reagents and Solutions

2.4. Sampling of Raw Materials and Cement

2.5. Sample Preparation

2.6. Analysis of Samples

2.7. Determination of Hg Thermospecies by Zeeman Hg Analyzer

3. Results

3.1. Optimization of the Heating Rate in the Evaporation Chamber

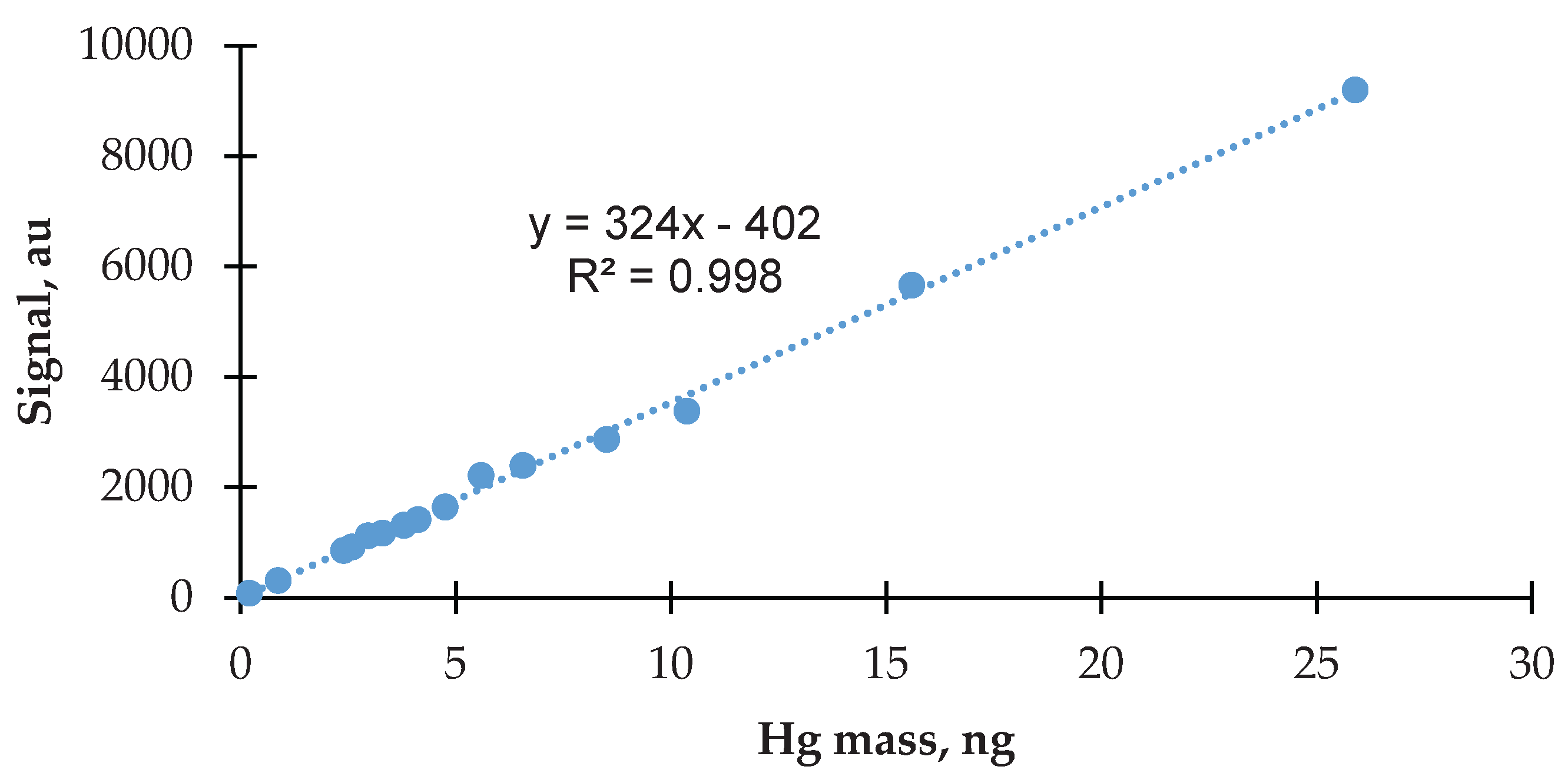

3.2. Calibration of Zeeman Hg Analyzer

3.3. Validation of Analytical Results

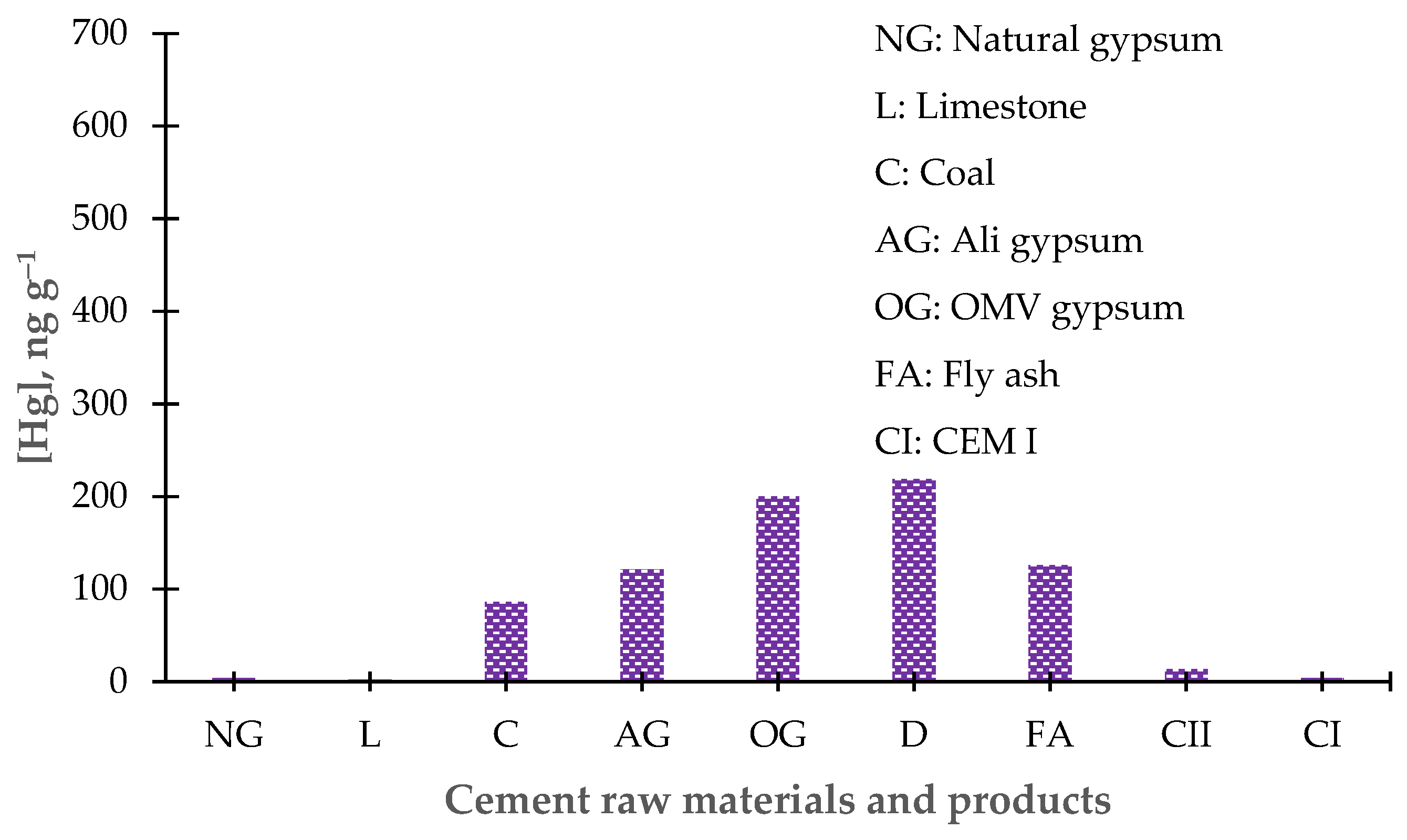

3.4. Results of the Determination of Total Hg in Cement Raw Materials

3.5. Results of Total Hg Determination in Different Grades of Cements

3.6. Results of Total Hg Determination in By-product of Cement Production

3.7. Results of the Determination of Hg Thermospecies

| Material | Total Hg, ng g−1 | Hg thermospecies concentration, ng g−1 | |||

| 20°C−180°C | 180°C−360°C | 360°C − 540°C | 540°C − 720°C | ||

| OMV Gypsum | 208 ± 257 | 200 ± 252 | - | - | - |

| ALI Gypsum | 262 ± 5.37 | 228 ± 30 | - | - | - |

| Fly Ash | 126 ± 48 | 108 ± 48 | - | - | - |

| Coal | 121 ± 26 | 106 ± 22 | - | - | - |

|

Cement Plant |

Sample ID |

Total Hg, ng g−1 |

Hg thermospecies, ng g−1 | |||

| 20°C−180°C | 180°C−360°C | 360°C−540°C | 540°C−720°C | |||

|

PPC De Hoek |

DH14 | 235 ± 6.7 | 194 ± 4.0 | − | − | − |

| DH15 | 179 ± 1.8 | 71.4 ± 0.8 | 12.9 ± 0.10 | 20.9 ± 0.5 | 0.5 ± 0.02 | |

| DH16 | 1663 ± 19.8 | 1223 ± 12 | 390 ± 2.0 | − | − | |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- ATSDR. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. 2017. Substance priority list [online]. Available from: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/spl/index.html [Accessed: 02 May 2018].

- Wu, Y.S.; Osman, A.I.; Hosny, M.; Elgarahy, A.M.; Eltaweil, A.S.; Rooney, D.W.; Chen, Z.; Rahim, N.S.; Sekar, M.; Gopinath, S.C.B.; Mat Rani, N.N.I.; Batumalaie, K.; Yap, P.S. The toxicity of mercury and its chemical compounds: molecular mechanisms and environmental and human health implications: a comprehensive review. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 5100–5126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jomova, K.; Alomar, S.; Nepovimova, E.; Kuca, K.; Valko, M. Heavy metals: toxicity and human health effects. Arch. Toxicol. 2025, 99, 153–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacyna, E.G.; Pacyna, J.M.; Sundseth, K.; Munthe, J.; Kindbom, K.; Wilson, S.; Steenhuisen, F.; Maxson, P. Global emission of mercury to the atmosphere from anthropogenic sources in 2005 and projections to 2020. Atmos. Environ. 2010, 44, 2487–2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirrone, N.; Cinnirella, S.; Feng, X.; Finkelman, R.B.; Friedli, H.R.; Leaner, J. Global mercury emissions to the atmosphere from anthropogenic and natural sources. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2010, 10, 5951–5964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, H.; Altaf, A.R. Elemental mercury (Hg0) emission, hazards, and control: A brief review. J Hazard Mater Adv 2022, 5, 100049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, S.V.; Kotmic, J.; Gačnic, J.; Živkovic, I.; Koenig, A.M.; Mlakar, T.L.; Hovart, M. Dispersion of airborne mercury species emitted from the cement plant. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 312, 120057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozerova, N.A. Mercury in geological systems. In: Baeyens, W.; Ebinghaus, R.; Vasiliev, O. Global and regional mercury cycles: sources, fluxes and mass balances. NATO ASI Ser. 1996, 21, 463–474. [Google Scholar]

- Yudovich, Ya.E.; Ketris, M.P. Mercury in coal: a review Part 1. Geochemistry. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2005, 62, 107–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yudovich, Ya.E.; Ketris, M.P. Mercury in coal: a review Part 2. Coal use and environmental problems. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2005, 62, 135–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, W.; Chen, C.; Liu, S.; Cao, Y. New insight into the characteristics and mechanism of Hg0 removal by NaClO2 in limestone slurry. Energ Fuel 2021, 35, 11403–11414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlakar, T.L.; Horvat, M.; Vuk, T.; Stergarsek, A.; Kotnik, J.; Tratnik, J.; Fajon, V. Mercury species, mass flows and processes in a cement plant. Fuel 2010, 89, 1936–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikkema, J.K.; Alleman, J.E.; Ong, S.K.; Wheelock, T.D. Mercury regulation, fate, transport, transformation and abatement within cement manufacturing facilities: review. Sci. Total Environ. 2011, 409, 4167–4178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Jensen, A.D.; Windelin, C.; Jensen, F. Dynamic measurement of mercury adsorption and oxidation on activated carbon in simulated cement kiln flue gas. Fuel 2012, 93, 649–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.K.; Parlikar, U.V.; Karstensen, K.H. Cement manufacturing-technology, practice and development. In Sustainable management of waste through co-processing, Ghosh, S.K.; Parlikar, U.V., Karstensen, K.H., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, D.; Mao, Y.; Jin, Y.; Song, Z. , Wang, X.; LI, J.; Wang, W. Review on the use of sludge in cement kilns: Mechanism, technical, and environmental evaluation. Process Saf Environ. Prot. 2023, 172, 1072–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogut, K.; Górecki, J.G.; Burmistrz, P. Opportunities for reducing mercury emissions in the cement industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 293, 126053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM Method D3684; Standard test method for total mercury in coal by the oxygen bomb combustion/atomic absorption method. ASTM, 2006.

- ASTM Method D6414; Standard test methods for total mercury in coal and coal combustion residues by acid extraction or wet oxidation/cold vapour atomic absorption. ASTM, 2006.

- US EPA method 7471; Mercury in solid or semisolid waste (manual cold-vapour technique). US EPA, 2007.

- ASTM method D6722; Standard test method for total mercury in coal and coal combustion residues by direct combustion analysis. ASTM, 2001.

- US EPA method 7473: Mercury in solids and solutions by thermal decomposition, amalgamation and atomic absorption spectrophotometry. US EPA, 2007.

- Merriam, N.W.; Cha, C.Y.; Kang, T.W.; Vaillancourt, M.B. Development of an advanced continuous mild gasification process for the production of coproducts. Task 4, Mild gasification tests. United States. 1990. Available from: https://www.osti.gov/biblio/6133465 [Accessed: 20 November 2022].

- Merdes, A.C.; Keener, T.C.; Khang, S.J.; Jenkins, R.G. Investigation into the fate of mercury in bituminous coal during mild pyrolysis. Fuel 1998, 77, 1783–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Keener, T.C.; Khang, S.J. 2000. The effect of coal volatility on mercury removal from bituminous coal during mild pyrolysis. Fuel Process Technol. 2000, 67, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guffey, F.D.; Bland, A.E. 2004. Thermal pretreatment of low-ranked coal for control of mercury emissions. Fuel Process Technol. 2004, 85, 521–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Lu, G.; Chan, O.Y. Fundamental study on mercury release characteristics during thermal upgrading of an Alberta sub-bituminous coal. Energ Fuel 2004, 18, 1855–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strezov, V.; Morrison, A.; Nelson, P.F. Pyrolytic mercury removal from coal and its adverse effect on coal swelling. Energ Fuel 2007, 21, 496–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Chang, L.; Liu, W.; Xiong, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, J. Advances in mercury removal from coal-fired flue gas by mineral adsorbents. J. Chem. Eng. 2020, 379, 122263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sholupov, S.; Pogarev, S.; Ryzhov, V.; Mashyanov, N.; Stroganov, A. Zeeman atomic absorption spectrometer RA-915+ for direct determination of mercury in air and complex matrix samples. Fuel Process Technol. 2004, 85, 473–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.J.; Zhuang, Z.X.; Wang, Y.R.; Huang, Z.Y.; Wang, X.R.; Lee, F.S.C. An analytical study of bioaccumulation and the binding forms of mercury in rat body using thermolysis coupled with atomic absorption spectrometry. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2005, 538, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panichev, N.A.; Panicheva, S.E. Determination of total mercury in fish and sea products by direct thermal decomposition atomic absorption spectrometry. Food chem. 2015, 166, 432–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sholupov, S.; Ganeev, A. Zeeman atomic absorption spectrometry using high frequency modulated light polarization. Spectrochim. Acta. Part B 1995, 50, 1227–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathebula, M.W.; Panichev, N.; Mandiwana, K. Determination of mercury thermospecies in South African coals in the enhancement of mercury removal by pre-combustion technologies. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 19282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, O.C.; Scheiner, B.J. Investigation of metal and non-metal migration through phosphogypsum. In AIME Proceedings on the Symposium on Emerging Process Technologies for a Cleaner Environment, Phoenix, USA, February 24–27.

- Carbonell-Barrachina, A.; Delaune, R.D.; Jugsujinda, A. Phosphogypsum chemistry under highly anoxic conditions. J. Waste Manag. 2002, 22, 657–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tayibi, H.; Choura, M.; Lopez, F.A.; Alguacil, F.J.; Lopez-Delgado, A. Environmental impact and management of phosphogypsum. J. Environ. Manage. 2009, 90, 2377–2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Z.; Wu, G.; Su, R.; Li, C.; Liang, P. Mobility and contamination assessment of mercury in coal fly ash, atmospheric deposition, and soil collected from Tianjin, china. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2011, 30, 1997–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rompalski, P.; Smolinski, A.; Krzton, H.; Gazdowicz, J.; Howaniec, N.; Rog, L. Determination of mercury content in hard coal and fly ash using X-ray diffraction and scanning electron microscopy coupled with chemical analysis. Arab. J. Chem. 2019, 12, 3927–3942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wu, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, T.; Zhang, Y.; Pan, W.P. Speciation analysis of Hg, As, Pb, Cd, and Cr in fly ash at different ESP’s hoppers. Fuel 2020, 280, 118688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P. , Gogineni, A.; Ammarullah, M.I. Sustainable bioengineering approach to industrial waste management: LD slag as a cementitious material. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, I.H.; Abdullah, M.M.A.B.; Heah, C.Y.; Liew, Y.M. Behaviour changes of ground granulated blast furnace slag geopolymers at high temperature. Adv. Cem. Res. 2020, 32, 465–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreda-Piñeiro, J.; Beceiro-González, E.; Alonso-Rodríguez, E.; González-Soto, E.; López-Mahía, P.; Muniategui-Lorenzo, S.; Prada-Rodríguez, D. Use of low temperature ashing and microwave acid extraction procedures for As and Hg determination in coal, coal fly ash, and slag samples by cold vapor/hydride generation AAS. At. Spectrosc. 2001, 22, 422–428. [Google Scholar]

- Tariq, S.A.; Hill, J.O. Thermal analysis of mercury(I) sulfate and mercury (II) sulphate. J Therm Anal Calorim 1981, 21, 277–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lide, D.R. CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 90th Edition. CRC Press 2020, 725–726. [Google Scholar]

- Sedlar, M.; Pavlin, M.; Popovic, A.; Hovart, M. Temperature stability of mercury compounds in solid substrates. Open Chem. 2015, 13, 404–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Zhang, C.; Kong, X.M.; Zhuo, Y.Q.; Zhu, Z.W. Mercury release from fly ashes and hydrated fly ash cement pastes. Atmos. Environ. 2018, 178, 11−18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, Z.; Wu, T.; Chen, J.; Fu, C.; Zhang, L.; Feng, X.; Fu, X.; Tang, L.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Z. Atmospheric mercury emissions from two pre-calciner cement plants in Southwest China. Atmos. Environ. 2019, 199, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berisha, S.; Živković, I.; Kotnik, J.; Mlakar, T.L.; Hovart, M. Quantification of total mercury in samples from cement production processing with thermal decomposition coupled with AAS. Accred. Qual. Assur. 2020, 25, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; He, J.; Xiao, Y.; Li, J.; Di, Y. 2021. Characterization of input materials to provide an estimate of mercury emissions related to China’s cement industry. Atmos. Environ. 2021, 246, 118133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashyanov, N.; Pogarev, S.E.; Panova, E.G.; Panichev, N.; Ryzhov, V. Determination of mercury thermospecies in coal. Fuel 2017, 203, 973–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Analyte | Heating Stage Temperature range |

| Total Hg determination | Single stage: Ambient T−720ºC |

| Stage 1: Ambient T−340ºC | |

| Stage 2: 344−378ºC | |

| Hg thermospecies | Stage 3: 387−485ºC |

| Stage 4: 510−617ºC | |

| Stage 5: 641−720ºC | |

| Stage 6: 720ºC −Ambient T (Cooling) |

| SARM 20 | NCSZC 78001 | |||

| Instrument | Certified value | Found value | Certified value | Found value |

| RA-915+ | 250 ± 30 | 247 ± 4.0 | 39 ± 0.9 | 38 ± 1.0 |

| DMA-80 | 250 ± 30 | 251 ± 5.0 | 39 ± 0.9 | 38 ± 0.8 |

| Raw Materials | PPC Jupiter, ng g−1 | PPC De Hoek, ng g−1 | PPC Hercules, ng g−1 |

| Limestone | 2.40 ± 0.28 | 3.02 ± 0.32 | 2.19 ± 0.32 |

| Fly Ash | 160 ± 2.55 | N | 89 ± 25 |

| Slag | 2.56 ± 0.41 | 3.23 ± 0.36 | 1.58 ± 0.19 |

| Natural Gypsum | 5.75 ± 0.47 | 2.84 ± 1.19 | 2.30 ± 0.33 |

| OMV Gypsum | 395 ± 4.83 | N | N |

| ALI Gypsum | N | N | 262 ± 7.38 |

| Raw Coal | 28.7 ± 2.63 | 87 ± 2.24 | 142 ± 19 |

| Cement Plant | Total Hg (ng g−1) |

| PPC Jupiter | 6.56 ± 0.72 a |

| 31.0 ± 4.14 b | |

| PPC De Hoek | 1.20 ± 0.020 a |

| 2.93 ± 0.28 b | |

| PPC Hercules | 1.32 ± 0.83 a |

| 8.13 ± 2.50 b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).