Submitted:

06 August 2025

Posted:

07 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

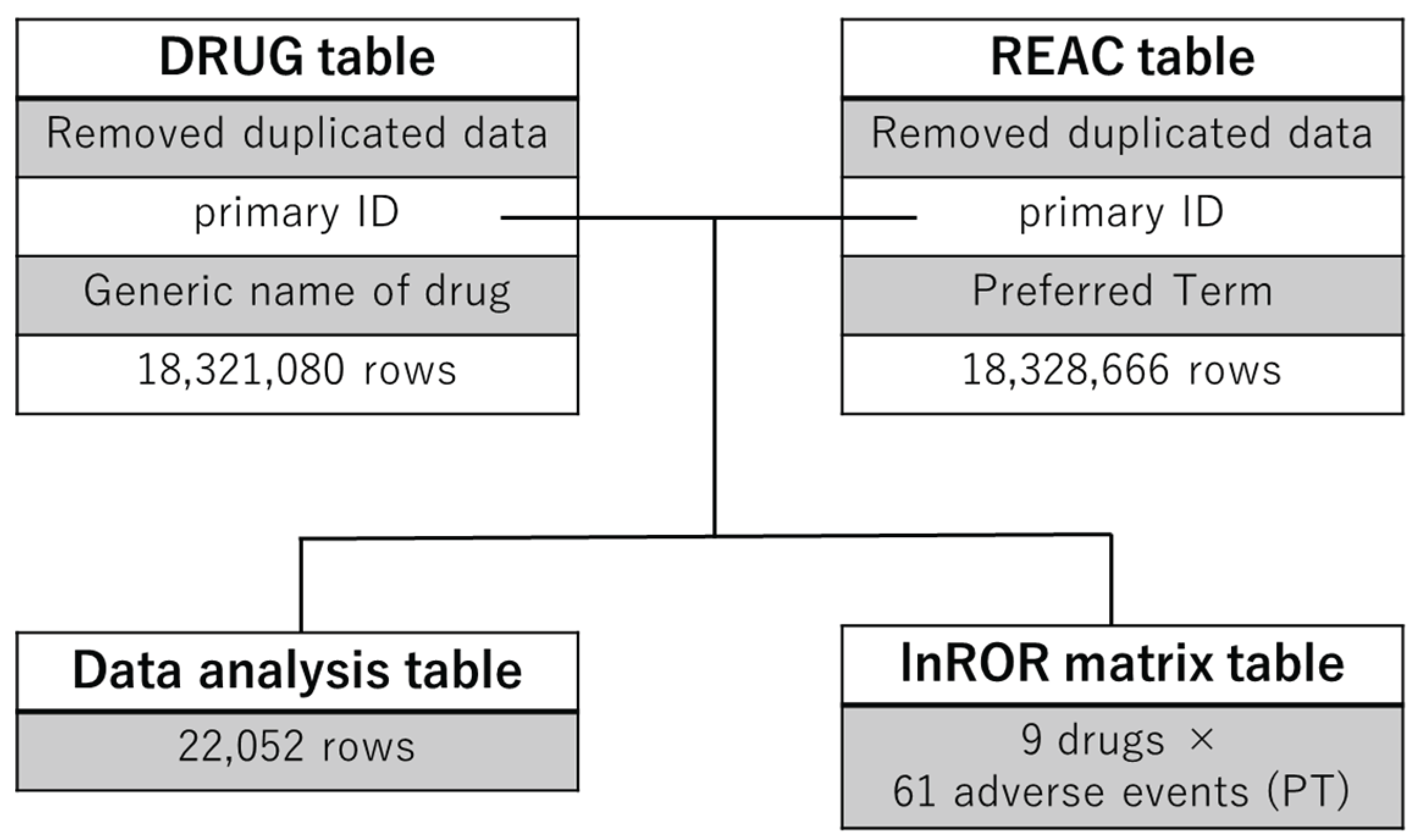

2.1. Construction of the Analytical Data Table

2.2. Number of Reports

2.3. Frequently Reported Adverse Events

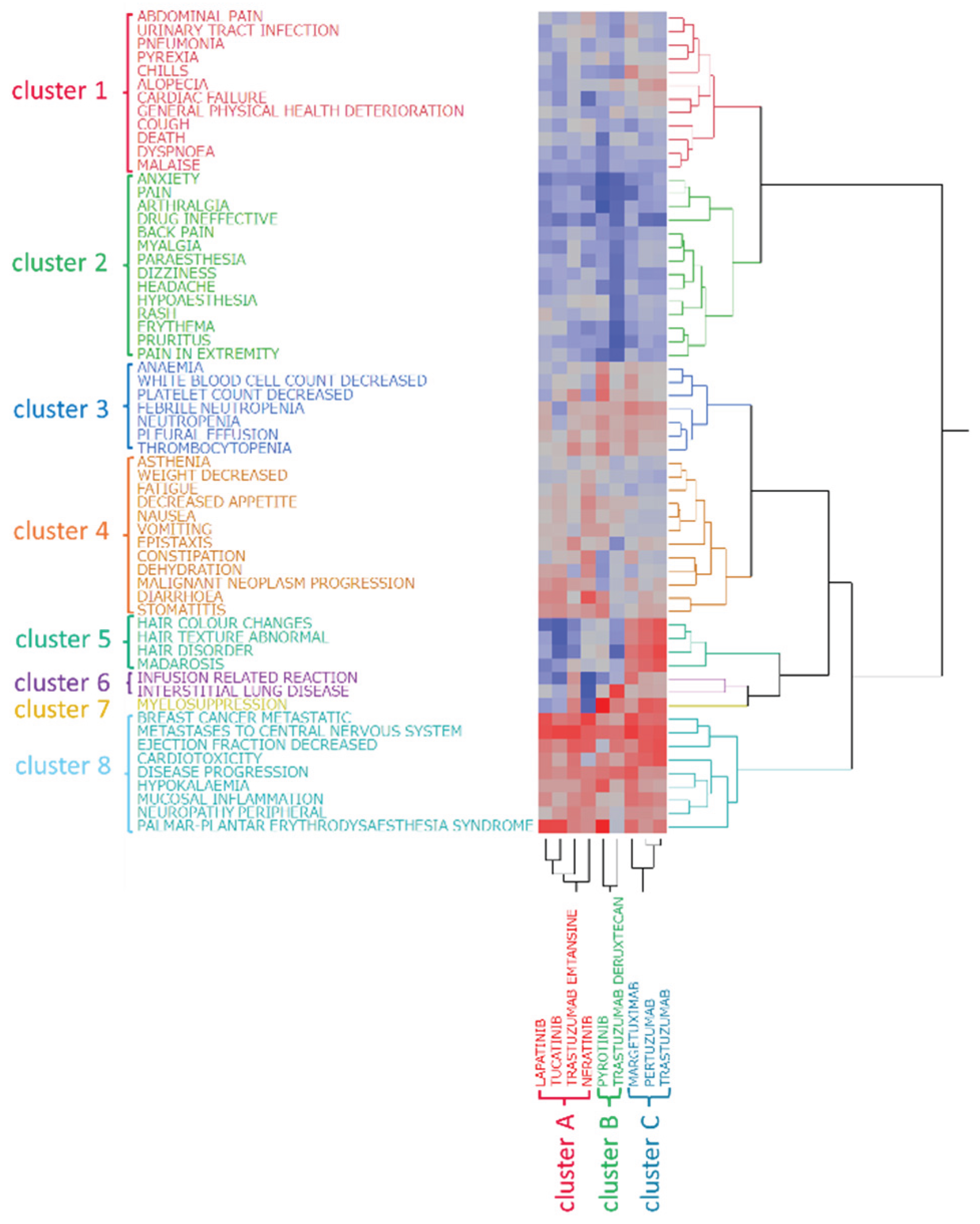

2.4. Hierarchical Cluster Analysis

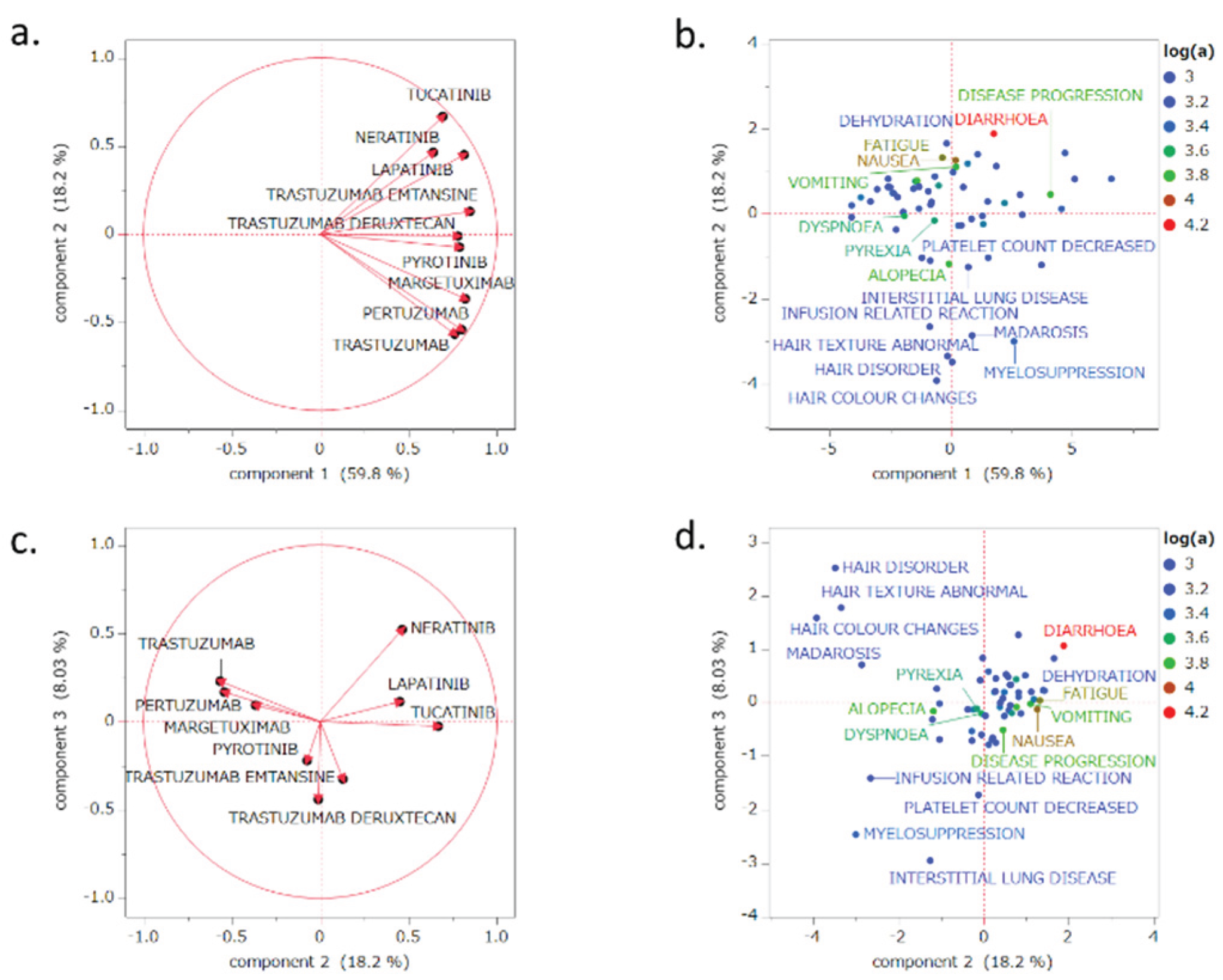

2.5. PCAs

3. Discussion

3.1. Number of Adverse Event Reports Related to HER2 Inhibitors

3.2. Classification of HER2 Inhibitors Based on Hierarchical Clustering Analysis

3.3. Classification of Adverse Events Based on Clustering Analysis

- Cluster 1: abdominal pain, alopecia, cardiac failure, chills, cough, death, dyspnea, general physical health deterioration, malaise, pneumonia, pyrexia, and urinary tract infection

- Cluster 2: anxiety, arthralgia, back pain, dizziness, drug ineffective, erythema, headache, hypoaesthesia, myalgia, pain, pain in extremity, paresthesia, pruritus, and rash

- Cluster 3: anemia, febrile neutropenia, neutropenia, decreased platelet count, pleural effusion, thrombocytopenia, decreased white blood cell count

- Cluster 4: asthenia, constipation, decreased appetite, dehydration, diarrhea, epistaxis, fatigue, malignant neoplasm progression, nausea, stomatitis, vomiting, and decreased weight

- Cluster 5: hair color changes, hair disorders, abnormal hair texture, and madarosis

- Cluster 6: infusion-related reactions and ILD

- Cluster 7: Myelosuppression

- Cluster 8: breast cancer metastatic, cardiotoxicity, disease progression, decreased ejection fraction, hypokalemia, metastases to the central nervous system, mucosal inflammation, peripheral neuropathy, and palmar–plantar erythrodysesthesia syndrome

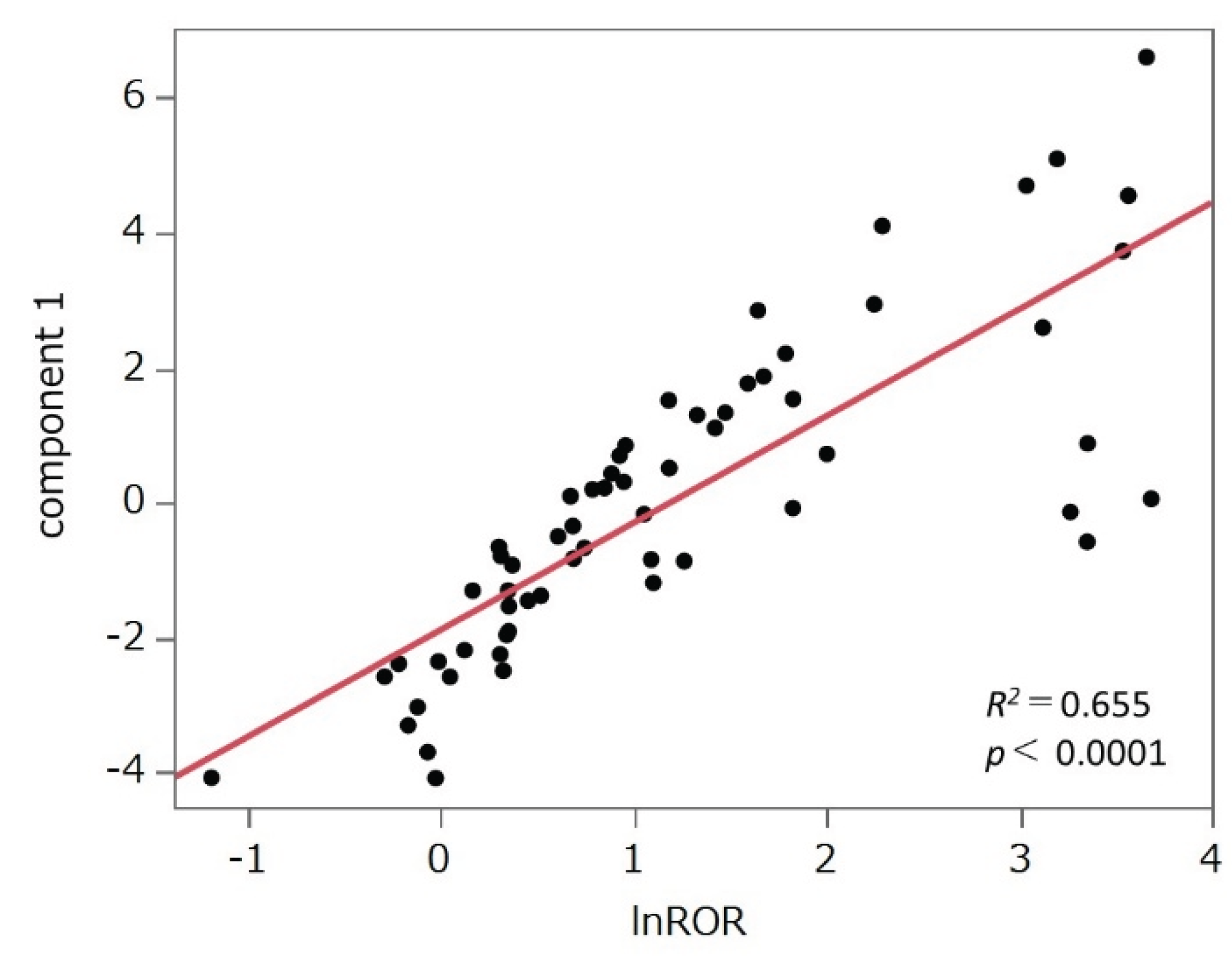

3.4. PCA

3.5. Limitations

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Data Table Construction

4.2. Terminology for Adverse Events and Targeted Drugs

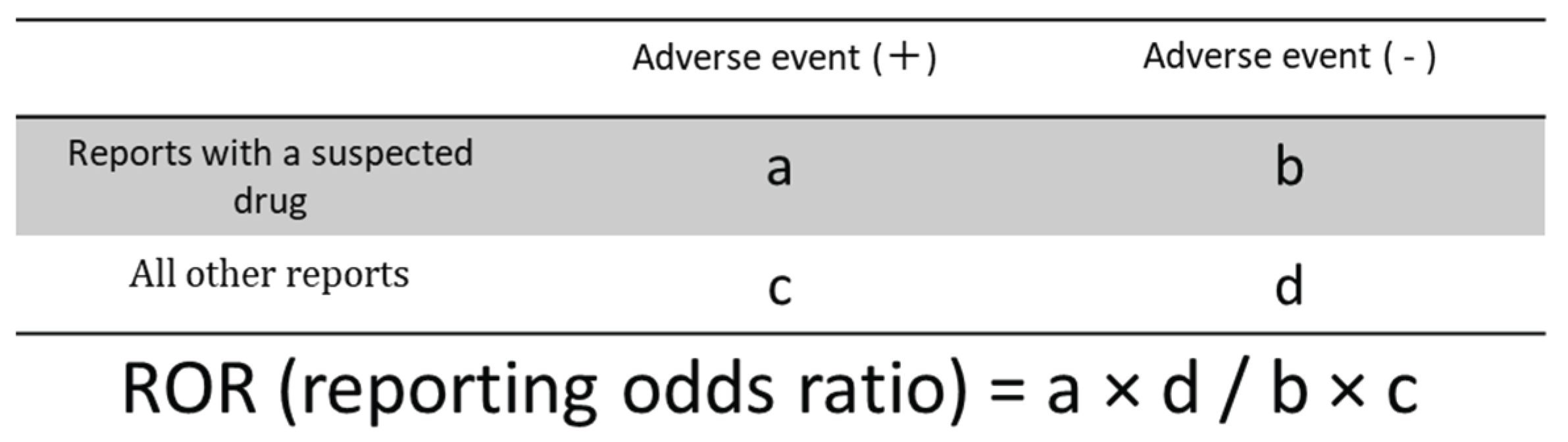

4.3. Relationship Between HER2 Inhibitors and Adverse Events

4.4. Construction of the Data Matrix for Clustering and PCA

4.5. Hierarchical Clustering Analysis

4.6. PCA

4.7. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| ILD | Interstitial lung disease |

| JSPS | Japan Society for the Promotion of Science |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| QoL | Quality of life |

| ROR | Reporting odds ratios |

| SRS | Spontaneous reporting systems |

| mAb | Monoclonal antibodies |

| ADC | Antibody-drug conjugates |

| TKI | Tyrosine kinase inhibitors |

References

- Coussens, L.; Yang-Feng, T.L.; Liao, Y.C.; Chen, E.; Gray, A.; McGrath, J.; Seeburg, P.H.; Libermann, T.A.; Schlessinger, J.; Francke, U.; et al. Tyrosine kinase receptor with extensive homology to EGF receptor shares chromosomal location with neu oncogene. Science 1985, 230, 1132–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schechter, A.L.; Stern, D.F.; Vaidyanathan, L.; Decker, S.J.; Drebin, J.A.; Greene, M.I.; Weinberg, R.A. The neu oncogene: an erb-B-related gene encoding a 185,000-Mr tumour antigen. Nature 1984, 312, 513–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravalos, C.; Jimeno, A. HER2 in gastric cancer: a new prognostic factor and a novel therapeutic target. Ann. Oncol. 2008, 19, 1523–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slamon, D.J.; Clark, G.M.; Wong, S.G.; Levin, W.J.; Ullrich, A.; McGuire, W.L. Human breast cancer: correlation of relapse and survival with amplification of the HER-2/neu oncogene. Science 1987, 235, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cameron, D.; Piccart-Gebhart, M.J.; Gelber, R.D.; Procter, M.; Goldhirsch, A.; de Azambuja, E.; Castro, G., Jr.; Untch, M.; Smith, I.; Gianni, L.; et al. 11 years’ follow-up of trastuzumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in HER2-positive early breast cancer: final analysis of the HERceptin Adjuvant (HERA) trial. Lancet 2017, 389, 1195–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccart-Gebhart, M.J.; Procter, M.; Leyland-Jones, B.; Goldhirsch, A.; Untch, M.; Smith, I.; Gianni, L.; Baselga, J.; Bell, R.; Jackisch, C.; et al. Trastuzumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in HER2-positive breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 353, 1659–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joensuu, H.; Kellokumpu-Lehtinen, P.L.; Bono, P.; Alanko, T.; Kataja, V.; Asola, R.; Utriainen, T.; Kokko, R.; Hemminki, A.; Tarkkanen, M.; et al. Adjuvant docetaxel or vinorelbine with or without trastuzumab for breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 354, 809–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, S.H.; Franzoi, M.A.B.; Temin, S.; Anders, C.K.; Chandarlapaty, S.; Crews, J.R.; Kirshner, J.J.; Krop, I.E.; Lin, N.U.; Morikawa, A.; et al. Systemic therapy for advanced human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer: ASCO guideline update. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 2612–2635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianni, L.; Pienkowski, T.; Im, Y.H.; Roman, L.; Tseng, L.M.; Liu, M.C.; Lluch, A.; Staroslawska, E.; de la Haba-Rodriguez, J.; Im, S.A.; et al. Efficacy and safety of neoadjuvant pertuzumab and trastuzumab in women with locally advanced, inflammatory, or early HER2-positive breast cancer (NeoSphere): a randomised multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012, 13, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Minckwitz, G.; Huang, C.S.; Mano, M.S.; Loibl, S.; Mamounas, E.P.; Untch, M.; Wolmark, N.; Rastogi, P.; Schneeweiss, A.; Redondo, A.; et al. Trastuzumab emtansine for residual invasive HER2-positive breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 617–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurvitz, S.A.; Hegg, R.; Chung, W.P.; Im, S.A.; Jacot, W.; Ganju, V.; Chiu, J.W.Y.; Xu, B.; Hamilton, E.; Madhusudan, S.; et al. Trastuzumab deruxtecan versus trastuzumab emtansine in patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer: Updated results from DESTINY-Breast03, a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2023, 401, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Minckwitz, G.; Schwedler, K.; Schmidt, M.; Barinoff, J.; Mundhenke, C.; Cufer, T.; Maartense, E.; de Jongh, F.E.; Baumann, K.H.; Bischoff, J.; et al. Trastuzumab beyond progression: Overall survival analysis of the GBG 26/BIG 3-05 phase III study in HER2-positive breast cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 2011, 47, 2273–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curigliano, G.; Mueller, V.; Borges, V.; Hamilton, E.; Hurvitz, S.; Loi, S.; Murthy, R.; Okines, A.; Paplomata, E.; Cameron, D.; et al. Corrigendum to “Tucatinib versus placebo added to trastuzumab and capecitabine for patients with pretreated HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer with and without brain metastases (HER2CLIMB): Final overall survival analysis. ” Ann. Oncol. 2023, 34, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saura, C.; Oliveira, M.; Feng, Y.H.; Dai, M.S.; Chen, S.W.; Hurvitz, S.A.; Kim, S.B.; Moy, B.; Delaloge, S.; Gradishar, W.; et al. Neratinib plus capecitabine versus lapatinib plus capecitabine in HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer previously treated with ≥2 HER2-directed regimens: Phase III NALA trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 3138–3149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slamon, D.J.; Leyland-Jones, B.; Shak, S.; Fuchs, H.; Paton, V.; Bajamonde, A.; Fleming, T.; Eiermann, W.; Wolter, J.; Pegram, M.; et al. Use of chemotherapy plus a monoclonal antibody against HER2 for metastatic breast cancer that overexpresses HER2. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 344, 783–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.; Miles, D.; Gianni, L.; Krop, I.E.; Welslau, M.; Baselga, J.; Pegram, M.; Oh, D.Y.; Diéras, V.; Guardino, E.; et al. Trastuzumab emtansine for HER2-positive advanced breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 367, 1783–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harpaz, R.; Perez, H.; Chase, H.S.; Rabadan, R.; Hripcsak, G.; Friedman, C. Biclustering of adverse drug events in the FDA’s spontaneous reporting system. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011, 89, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamazaki, R.; Uesawa, Y. Characterization of antineoplastic agents inducing taste and smell disorders using the FAERS database. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, Y.; Chen, J.; Duan, L.; Wang, F.; Lai, H.; Mo, Z.; Zhu, W. Comparing the difference of adverse events with HER2 inhibitors: A study of the FDA adverse event reporting system (FAERS). Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1288362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlam, I.; Swain, S.M. HER2-positive breast cancer and tyrosine kinase inhibitors: The time is now. NPJ Breast Cancer 2021, 7, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Press, M.F.; Cordon-Cardo, C.; Slamon, D.J. Expression of the HER-2/neu proto-oncogene in normal human adult and fetal tissues. Oncogene 1990, 5, 953–962. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, W.; Yang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, D.; Li, N. Pyrotinib for HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Transl. Cancer Res. 2023, 12, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Meng, J.; Mei, X.; Mo, M.; Xiao, Q.; Han, X.; Zhang, L.; Shi, W.; Chen, X.; Ma, J.; et al. Brain radiotherapy with pyrotinib and capecitabine in patients with ERBB2-positive advanced breast cancer and brain metastases: A nonrandomized phase 2 trial. JAMA Oncol. 2024, 10, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurvitz, S.A.; Kim, S.B.; Chung, W.P.; Im, S.A.; Park, Y.H.; Hegg, R.; Kim, M.H.; Tseng, L.M.; Petry, V.; Chung, C.F.; et al. Trastuzumab deruxtecan versus trastuzumab emtansine in HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer patients with brain metastases from the randomized DESTINY-Breast03 trial. ESMO Open 2024, 9, 102924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baselga, J.; Cortés, J.; Kim, S.B.; Im, S.A.; Hegg, R.; Im, Y.H.; Roman, L.; Pedrini, J.L.; Pienkowski, T.; Knott, A.; et al. Pertuzumab plus trastuzumab plus docetaxel for metastatic breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, A.R.; Im, S.A.; Mattar, A.; Colomer, R.; Stroyakovskii, D.; Nowecki, Z.; De Laurentiis, M.; Pierga, J.Y.; Jung, K.H.; Schem, C.; et al. Fixed-dose combination of pertuzumab and trastuzumab for subcutaneous injection plus chemotherapy in HER2-positive early breast cancer (FeDeriCa): A randomised, open-label, multicentre, non-inferiority, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairlamb, D.J. Hair changes following cytotoxic drug induced alopecia. Postgrad. Med. J. 1988, 64, 907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tobin, D.J.; Hagen, E.; Botchkarev, V.A.; Paus, R. Do hair bulb melanocytes undergo apoptosis during hair follicle regression (catagen)? J. Investig. Dermatol. 1998, 111, 941–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westgate, G.E.; Ginger, R.S.; Green, M.R. The biology and genetics of curly hair. Exp. Dermatol. 2017, 26, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, B.A. The hair follicle enigma. Exp. Dermatol. 2017, 26, 472–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belum, V.R.; Marulanda, K.; Ensslin, C.; Gorcey, L.; Parikh, T.; Wu, S.; Busam, K.J.; Gerber, P.A.; Lacouture, M.E. Alopecia in patients treated with molecularly targeted anticancer therapies. Ann. Oncol. 2015, 26, 2496–2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordstrom, J.L.; Gorlatov, S.; Zhang, W.; Yang, Y.; Huang, L.; Burke, S.; Li, H.; Ciccarone, V.; Zhang, T.; Stavenhagen, J.; et al. Anti-tumor activity and toxicokinetics analysis of MGAH22, an anti-HER2 monoclonal antibody with enhanced Fcγ receptor binding properties. Breast Cancer Res. 2011, 13, R123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavenhagen, J.B.; Gorlatov, S.; Tuaillon, N.; Rankin, C.T.; Li, H.; Burke, S.; Huang, L.; Vijh, S.; Johnson, S.; Bonvini, E.; et al. Fc optimization of therapeutic antibodies enhances their ability to kill tumor cells in vitro and controls tumor expansion in vivo via low-affinity activating Fcγ receptors. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 8882–8890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rugo, H.S.; Im, S.A.; Cardoso, F.; Cortés, J.; Curigliano, G.; Musolino, A.; Pegram, M.D.; Wright, G.S.; Saura, C.; Escrivá-de-Romaní, S.; et al. Efficacy of margetuximab vs trastuzumab in patients with pretreated ERBB2-positive advanced breast cancer: A phase 3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2021, 7, 573–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menopause Hair Care: Understanding the Changes and Solutions. Available online: https://restorehairguide.com/does-herceptin-cause-hair-loss-unraveling-the-connection/ (accessed on 14 June 2025).

- Lin, N.U.; Diéras, V.; Paul, D.; Lossignol, D.; Christodoulou, C.; Stemmler, H.J.; Roché, H.; Liu, M.C.; Greil, R.; Ciruelos, E.; et al. Multicenter phase II study of lapatinib in patients with brain metastases from HER2-positive breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009, 15, 1452–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachelot, T.; Romieu, G.; Campone, M.; Diéras, V.; Cropet, C.; Dalenc, F.; Jimenez, M.; Le Rhun, E.; Pierga, J.Y.; Gonçalves, A.; et al. Lapatinib plus capecitabine in patients with previously untreated brain metastases from HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer (LANDSCAPE): A single-group phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2013, 14, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, R.A.; Gelman, R.S.; Anders, C.K.; Melisko, M.E.; Parsons, H.A.; Cropp, A.M.; Silvestri, K.; Cotter, C.M.; Componeschi, K.P.; Marte, J.M.; et al. TBCRC 022: A phase II trial of neratinib and capecitabine for patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer and brain metastases. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 1081–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, N.U.; Borges, V.; Anders, C.; Murthy, R.K.; Paplomata, E.; Hamilton, E.; Hurvitz, S.; Loi, S.; Okines, A.; Abramson, V.; et al. Intracranial efficacy and survival with tucatinib plus trastuzumab and capecitabine for previously treated HER2-positive breast cancer with brain metastases in the HER2CLIMB trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 2610–2619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, O.; Xiong, Y.; Endo, S.; Yoshihara, K.; Garimella, T.; AbuTarif, M.; Wada, R.; LaCreta, F. Population pharmacokinetics of trastuzumab deruxtecan in patients with HER2-positive breast cancer and other solid tumors. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 109, 1314–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venur, V.A.; Leone, J.P. Targeted therapies for brain metastases from breast cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mair, M.J.; Bartsch, R.; Le Rhun, E.; Berghoff, A.S.; Brastianos, P.K.; Cortes, J.; Gan, H.K.; Lin, N.U.; Lassman, A.B.; Wen, P.Y.; et al. Understanding the activity of antibody–drug conjugates in primary and secondary brain tumours. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 20, 372–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askoxylakis, V.; Ferraro, G.B.; Kodack, D.P.; Badeaux, M.; Shankaraiah, R.C.; Seano, G.; Kloepper, J.; Vardam, T.; Martin, J.D.; Naxerova, K.; et al. Preclinical efficacy of ado-trastuzumab emtansine in the brain microenvironment. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2015, 108, djv313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, F.; Ouyang, Q.; Li, W.; Jiang, Z.; Tong, Z.; Liu, Y.; Li, H.; Yu, S.; Feng, J.; Wang, S.; et al. Pyrotinib or lapatinib combined with capecitabine in HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer with prior taxanes, anthracyclines, and/or trastuzumab: A randomized, phase II study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 2610–2619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcenas, C.H.; Hurvitz, S.A.; Di Palma, J.A.; Bose, R.; Chien, A.J.; Iannotti, N.; Marx, G.; Brufsky, A.; Litvak, A.; Ibrahim, E.; et al. Improved tolerability of neratinib in patients with HER2-positive early-stage breast cancer: The CONTROL trial. Ann. Oncol. 2020, 31, 1223–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rugo, H.S.; Bianchini, G.; Cortes, J.; Henning, J.W.; Untch, M. Optimizing treatment management of trastuzumab deruxtecan in clinical practice of breast cancer. ESMO Open 2022, 7, 100553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhu, C.; Dong, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Ren, D.; Zhao, F.; Zhao, J. Disproportionality analysis of interstitial lung disease associated with novel antineoplastic agents during breast cancer treatment: A pharmacovigilance study. EClinicalMedicine 2025, 82, 103160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saglio, G.; Kim, D.W.; Issaragrisil, S.; le Coutre, P.; Etienne, G.; Lobo, C.; Pasquini, R.; Clark, R.E.; Hochhaus, A.; Hughes, T.P.; et al. Nilotinib versus imatinib for newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 2251–2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, T.P.; Munhoz, E.; Salvino, M.A.; Ong, T.C.; Elhaddad, A.; Shortt, J.; Quach, H.; Pavlovsky, C.; Louw, V.J.; Shih, L.Y.; et al. Nilotinib dose-optimization in newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukaemia in chronic phase: final results from ENESTxtnd. Br. J. Haematol. 2017, 179, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, D.G.; Tsimberidou, A.M. Dasatinib in chronic myeloid leukemia: A review. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2009, 5, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendell, J.C.; Domchek, S.M.; Burstein, H.J.; Harris, L.; Younger, J.; Kuter, I.; Bunnell, C.; Rue, M.; Gelman, R.; Winer, E. Central nervous system metastases in women who receive trastuzumab-based therapy for metastatic breast carcinoma. Cancer 2003, 97, 2972–2977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, R.; Dang, C.T.; Malkin, M.G.; Abrey, L.E. The risk of central nervous system metastases after trastuzumab therapy in patients with breast carcinoma. Cancer 2004, 101, 810–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romond, E.H.; Perez, E.A.; Bryant, J.; Suman, V.J.; Geyer, C.E., Jr.; Davidson, N.E.; Tan-Chiu, E.; Martino, S.; Paik, S.; Kaufman, P.A.; et al. Trastuzumab plus adjuvant chemotherapy for operable HER2-positive breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 353, 1673–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain, S.M.; Baselga, J.; Kim, S.B.; Ro, J.; Semiglazov, V.; Campone, M.; Ciruelos, E.; Ferrero, J.M.; Schneeweiss, A.; Heeson, S.; et al. Pertuzumab, trastuzumab, and docetaxel in HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 724–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardiotoxicity: An Unexpected Consequence of HER2-Targeted Therapies. Available online: https://www.acc.org/latest-in-cardiology/articles/2016/06/06/09/32/cardiotoxicity (accessed on 14 June 2025).

- Kwakman, J.J.M.; Elshot, Y.S.; Punt, C.J.A.; Koopman, M. Management of cytotoxic chemotherapy-induced hand-foot syndrome. Oncol. Rev. 2020, 14, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, N.; Lee, S.J.; Ohtani, S.; Im, Y.H.; Lee, E.S.; Yokota, I.; Kuroi, K.; Im, S.A.; Park, B.W.; Kim, S.B.; et al. Adjuvant capecitabine for breast cancer after preoperative chemotherapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 2147–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bang, Y.J.; Van Cutsem, E.; Feyereislova, A.; Chung, H.C.; Shen, L.; Sawaki, A.; Lordick, F.; Ohtsu, A.; Omuro, Y.; Satoh, T.; et al. Trastuzumab in combination with chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for treatment of HER2-positive advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer (ToGA): A phase 3, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2010, 376, 687–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassoon, I.; Blanc, V. Antibody–drug conjugate (ADC) clinical pipeline: A review. Methods Mol. Biol. 2013, 1045, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manabe, S. Development and current status of antibody–drug conjugate (ADC). Drug Deliv. Syst. 2019, 34, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogitani, Y.; Aida, T.; Hagihara, K.; Yamaguchi, J.; Ishii, C.; Harada, N.; Soma, M.; Okamoto, H.; Oitate, M.; Arakawa, S.; et al. DS-8201a, a novel HER2-targeting ADC with a novel DNA topoisomerase I inhibitor, demonstrates a promising antitumor efficacy with differentiation from T-DM1. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 22, 5097–5108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakada, T.; Sugihara, K.; Jikoh, T.; Abe, Y.; Agatsuma, T. The latest research and development into the antibody–drug conjugate, [fam-] trastuzumab deruxtecan (DS-8201a), for HER2 cancer therapy. Chem. Pharm. Bull. (Tokyo) 2019, 67, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doronina, S.O.; Toki, B.E.; Torgov, M.Y.; Mendelsohn, B.A.; Cerveny, C.G.; Chace, D.F.; DeBlanc, R.L.; Gearing, R.P.; Bovee, T.D.; Siegall, C.B.; et al. Development of potent monoclonal antibody auristatin conjugates for cancer therapy. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003, 21, 778–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uppal, H.; Doudement, E.; Mahapatra, K.; Darbonne, W.C.; Bumbaca, D.; Shen, B.Q.; Du, X.; Saad, O.; Bowles, K.; Olsen, S.; et al. Potential mechanisms for thrombocytopenia development with trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1). Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doi, T.; Shitara, K.; Naito, Y.; Shimomura, A.; Fujiwara, Y.; Yonemori, K.; Shimizu, C.; Shimoi, T.; Kuboki, Y.; Matsubara, N.; et al. Safety, pharmacokinetics, and antitumour activity of trastuzumab deruxtecan (DS-8201), a HER2-targeting antibody–drug conjugate, in patients with advanced breast and gastric or gastro-oesophageal tumours: A phase 1 dose-escalation study. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, 1512–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Arx, C.; De Placido, P.; Caltavituro, A.; Di Rienzo, R.; Buonaiuto, R.; De Laurentiis, M.; Arpino, G.; Puglisi, F.; Giuliano, M.; Del Mastro, L. The evolving therapeutic landscape of trastuzumab–drug conjugates: Future perspectives beyond HER2-positive breast cancer. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2023, 113, 102500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumagai, K.; Aida, T.; Tsuchiya, Y.; Kishino, Y.; Kai, K.; Mori, K. Interstitial pneumonitis related to trastuzumab deruxtecan, a human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-targeting Ab–drug conjugate, in monkeys. Cancer Sci. 2020, 111, 4636–4645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS). Available online: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-approvals-and-databases/fda-adverse-event-reporting-system-faers (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Lawson, R. Small sample confidence intervals for the odds ratio. Commun. Stat. Simul. Comput. 2004, 33, 1095–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Drug | Number of cases |

|---|---|

| Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) | 94,516 |

| Trastuzumab | 67,765 |

| Pertuzumab | 26,692 |

| Margetuximab | 59 |

| Antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) | 13,381 |

| Trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1) | 7,897 |

| Trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd) | 5,484 |

| Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) | 23,967 |

| Lapatinib | 16,073 |

| Tucatinib | 5,402 |

| Neratinib | 2,162 |

| Pyrotinib | 330 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).