1. Introduction

Philodendron, one of the largest and most economically significant genera in the Araceae family, comprises over 500 species native to the tropical and subtropical Americas and the West Indies [

1,

2]. Renowned for their stunning foliage, diverse forms, and adaptability to indoor environments,

Philodendrons are a cornerstone of the global ornamental plant industry. They hold a dominant position in the foliage trade, particularly in major production hubs like Taiwan and Thailand, meeting a consistent and high consumer demand for interior landscaping plants.

Among the vast array of species,

Philodendron erubescens 'Pink Princess' is especially prized for its unique ornamental value. This cultivar is distinguished by its dark purplish-green leaves that feature striking, unpredictable pink variegation, creating a dramatic visual contrast [

3]. The high demand for 'Pink Princess' is driven by this exceptional beauty, making efficient and reliable mass propagation a critical goal for commercial growers. Despite high demand, the large-scale production of

P. erubescens 'Pink Princess' is constrained by the significant limitations of conventional propagation methods. Traditional propagation through stem cuttings is slow, labor-intensive, and requires a large number of valuable mother plants to generate only a limited number of offspring. Propagation from seed is also impractical due to the short viability of

Philodendron seeds. Furthermore, it carries a risk of genetic variation, which means the desirable pink variegation may not be passed on to the progeny. These traditional techniques are difficult to scale up and often yield a limited number of high-value plants, failing to meet market needs while also posing a risk for transmitting systemic pathogens [

4,

5].

To address these challenges,

in vitro micropropagation has been explored as a superior alternative for the rapid and disease-free clonal multiplication of elite cultivars. This process involves growing plant tissues under sterile conditions and is critically dependent on plant growth regulators (PGRs) like auxins and cytokinins to direct development [

6,

7]. While studies have reported micropropagation protocols for various

Philodendron species, including

P. erubescens 'Pink Princess' [3−5,8], significant gaps still prevent the development of a fully optimized, commercial-scale system. Most conventional tissue culture relies on semi-solid media. This method is labor-intensive, costly, difficult to automate, and ill-suited for large-scale industrial production. Although using liquid media can accelerate growth, the continuous immersion of explants often leads to hyperhydricity. This physiological disorder produces weak, glassy plants with low survival rates after being transferred to soil [

9,

10]. Therefore, this study aims to develop a more efficient micropropagation protocol for

P. erubescens 'Pink Princess' by employing an advanced Temporary Immersion Bioreactor (TIB) system. This novel approach is designed to overcome the limitations of both semi-solid and liquid culture by providing intermittent nutrient immersion and enhanced aeration [

11].

A key secondary challenge is maintaining genetic integrity, as rapid cloning can introduce somaclonal variation. Assessing the genetic fidelity of micropropagated plants is therefore essential for quality control. Various PCR-based molecular markers like Amplified Fragment Length Polymorphism (AFLP), Inter Simple Sequence Repeats (ISSR), Simple Sequence Repeats (SSR), Start Codon Targeted (SCoT), and Random Amplified Polymorphic DNA (RAPD) have been employed to assess the genetic homogeneity amongst the micropropagated plants and donor plants. However, amongst these molecular markers, RAPD is widely used due to its simplicity and efficiency in detecting genetic polymorphisms across a variety of plants [12−15]. Therefore, the specific objectives of this research were: (1) to optimize shoot induction by evaluating different cytokinins; (2) to determine the optimal auxin treatment for root induction; (3) to assess the acclimatization success of TIB-regenerated plantlets; and (4) to evaluate the genetic stability and clonal fidelity of the new plantlets against the mother plant using RAPD markers.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Chemicals

Protocorm-like bodies (PLBs) of P. erubescens 'Pink Princess' were sourced from a private collection in Udon Thani, Thailand (courtesy of Mrs. Nuntipa Khumkarjorn). These explants were established as in vitro stock cultures and maintained on Murashige and Skoog (MS) basal medium. The medium was supplemented with 2.0 mg/L 6-benzylaminopurine (BAP) and 0.5 mg/L 1-naphthaleneacetic acid (NAA). The cultures were incubated at a constant temperature of 25±2 ℃ under a 16-hour photoperiod provided by fluorescent lights at an intensity of 45 μmol/m.s. To ensure vigor and provide sufficient material, the stock cultures were subcultured onto fresh medium every 30 days before being used for experiments.

MS basal medium was purchased from PhytoTech Labs (Kansas, MO, USA). All plant growth regulators, including BAP, NAA, Indole-3-butyric acid (IBA), Indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D), Kinetin (Kn), and Thidiazuron (TDZ), were procured from Sigma-Aldrich Corporation (St. Louis, MI, USA). The planting materials for the acclimatization stage, which included perlite, vermiculite, and peat moss, were purchased from Agro Outlet at Khon Kaen University (Khon Kaen, Thailand).

2.2. The Temporary Immersion Bioreactor (TIB) System Setup

Micropropagation was carried out in a TIB system consisting of two interconnected, 600 mL autoclavable glass vessels. The upper vessel was configured as the culture chamber to hold the plant explants, while the lower vessel served as a reservoir for the liquid medium, with a working volume of 300 mL. The entire TIB unit, including the medium, was autoclaved before use.

The system's operation was automated. A pneumatic pump, regulated by an electronic timer and solenoid valves, delivered sterile-filtered air through a 0.2 µm syringe filter (Minisart® NML, Sartorius Stedim Biotech Gmbh, August-Spindler-Strasse 11, Goettingen, Germany) into the medium reservoir. The resulting positive pressure propelled the liquid medium through a stainless-steel tube into the culture chamber, immersing the explants for a pre-set duration. Upon completion of the immersion period, the timer deactivated the pump and opened the solenoid valve to release the air pressure. This allowed the medium to drain completely back into the reservoir via gravity. This design provides intermittent nutrient contact and a well-aerated environment, which is critical for promoting vigorous growth while preventing conditions like waterlogging and hyperhydricity.

2.3. Effect of Cytokinins on Shoot Induction of Philodendron ‘Pink Princess’

Healthy, 30-day-old PLBs, approximately 1.0–1.5 cm in diameter, were used as explants in this study. This size was selected based on a preliminary study, which indicated it yields optimal growth performance. The explants were cultured in a liquid MS medium supplemented with 30 g/L of sucrose and one of three cytokinins at various concentrations: BAP (0, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 4.0, or 8.0 mg/L), Kn (0, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 4.0, or 8.0 mg/L), or TDZ (0, 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, or 2.0 mg/L). Before use, the pH of all media was adjusted to 5.6–5.8 with 0.1 N NaOH or 0.1 N HCl.

For each treatment, five explants were placed into the upper growth chamber of a TIB system. The lower storage chamber of each bioreactor was then filled with 300 mL of the corresponding liquid medium. All treatments were conducted in triplicate. The cultures were maintained in a growth room at 25±2 °C under a 16-hour photoperiod with a light intensity of 45 μmol/m.s. The TIB system was programmed to immerse the explants by flooding the growth chamber with medium for 4 minutes every 8 hours. After 30 days of cultivation, the number and length of the resulting shoots were recorded.

2.4. Effect of Auxins on Root Formation of Philodendron ‘Pink Princess’

This experiment was designed to compare the efficacy of two culture systems—a TIB and a conventional semi-solid medium—for inducing roots on microshoots. The microshoots used were healthy, well-established explants obtained from the optimal cytokinin treatment in the previous study. In both systems, the effects of three different auxins were evaluated: NAA, IBA, and IAA, each at concentrations of 0, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, and 4.0 mg/L. The basal medium for all treatments was MS supplemented with 30 g/L sucrose. For the semi-solid cultures, the medium was solidified with a gelling agent (e.g., 8 g/L agar). The pH of all media was adjusted to 5.6–5.8 before use.

For the TIB treatments, individual microshoots were placed in the upper growth chamber, with the lower storage chamber containing 300 mL of the corresponding liquid medium. For the semi-solid treatments, individual microshoots were cultured in vessels on the surface of the solidified medium. All treatments were conducted in triplicate. All cultures were maintained in a single growth room at 25±2 °C under a 16-hour photoperiod and a light intensity of 45 μmol/m.s. The TIB systems were programmed for an immersion frequency of 4 minutes every 8 hours. After 30 days of cultivation, the number of roots and their lengths were recorded for comparison.

2.5. Ex vitro Acclimatization of the Plantlets

Rooted plantlets from the semi-solid culture system were selected for acclimatization. To ensure uniformity, only plantlets that were 1.0–1.2 cm in height and possessed at least three healthy roots were chosen for the experiment. The selected plantlets were carefully removed from the culture medium, and their roots were gently rinsed with sterile distilled water to remove any adhering agar. Subsequently, they were transplanted into 7.5 cm diameter plastic pots to evaluate the effect of different potting substrates. The three mixtures tested were: peat moss, perlite, and vermiculite (PPV) (2:1:1, v/v/v), peat moss and vermiculite (PV) (2:1, v/v), and peat moss and perlite (PP) (2:1, v/v). Each substrate treatment consisted of ten replicate plants. The potted plants were placed in a growth chamber and maintained at 25±2 °C with a relative humidity of 45–55%. They were cultured under a 16-hour photoperiod with a light intensity of approximately 45 μmol/m.s. The growth performance of the adapted plantlets was assessed after 30 and 45 days of cultivation by recording the survival rate, plant height, number of leaves, number of roots, and root length.

2.6. Genetic Stability Assessment of the Plantlets

2.6.1. Genomic DNA Extraction

Genomic DNA was extracted from fresh, young leaves of one-year-old mother plants and 45-day-old micropropagated plantlets using the DNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The DNA concentration was measured with a BioDrop µLite spectrophotometer (Denville Scientific Inc., South Plainfield, NJ, USA), while its integrity and quality were verified by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis.

2.6.2. PCR Reaction and RAPD Analysis

DNA amplification was performed using ten RAPD primers (

Table 1). The 25 µL PCR reaction mixture contained 1.0 µL of genomic DNA, 2.5 µL of 10x PCR buffer, 0.5 µL of dNTPs (10 mM), 1.0 µL of MgCl₂ (50 mM), 0.125 µL of Taq DNA polymerase (5 U/µL), 2.5 µL of primer (10 µM), and 17.38 µL of nuclease-free water.

Amplification was conducted in a thermal cycler (C1000 TouchTM cycler, Bio-Rad Lab, Inc., CA, USA) with the following program: an initial denaturation at 94 °C for 4 minutes, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 seconds, annealing at 35 °C for 1 minute, and extension at 72 °C for 2 minutes; and a final extension at 72 °C for 7 minutes. The resulting PCR products were separated on a 1% agarose gel, visualized, and their sizes were determined against a molecular weight marker.

2.7. Experimental Design and Statistical Analysis

A completely randomized design (CRD) was employed for all experiments, including shoot induction, root formation, and ex vitro acclimatization. Each treatment was performed in triplicate. The collected data were analyzed using SPSS Statistics software (Version 28.0, IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and treatment means were compared using Duncan’s Multiple Range Test (DMRT) at a significance level of p < 0.05.

3. Results and Discussion

The micropropagation of

Philodendron species, including the popular

Philodendron ‘Pink Princess’, has traditionally relied on conventional semi-solid and liquid culture systems [3−5,8]. However, both methods have inherent drawbacks that hinder their suitability for commercial-scale production. Semi-solid cultures are labor-intensive, costly, and present challenges for automation. Conversely, while liquid cultures allow for better contact with nutrients, they often lead to hyperhydricity—a physiological disorder causing water-soaked, vitrified tissues in plantlets—which compromises plant quality and survival [

9,

10].

To overcome these limitations, this study utilized a TIB system. This innovative approach merges the benefits of both traditional methods by periodically immersing the plantlets in a liquid medium while ensuring adequate aeration during non-immersion periods. By doing so, the TIB system mitigates the risk of hyperhydricity and reduces manual labor, thus offering a more efficient, automated, and economically beneficial alternative for mass micropropagation [

9,

11]. To develop a complete and reliable protocol, the effects of PGRs on shoot and root induction, the evaluation of the

ex vitro acclimatization of the established plantlets, and the analysis of their genetic stability using RAPD markers were performed and described as follows.

3.1. Effect of Cytokinins on Shoot Induction and Proliferation

Cytokinins are a class of phytohormones essential for regulating numerous aspects of plant development and physiology. Their functions include promoting cell division and expansion, guiding chloroplast differentiation, controlling morphogenesis, managing nutrient allocation, and mediating cellular adaptation to abiotic stresses [16−18].

In plant micropropagation, various natural and synthetic cytokinins are used to stimulate growth, with their efficacy being highly dependent on the plant species, the type of explant used, and the specific developmental stage [

18]. The literature documents the successful application of several cytokinins for shoot induction in the

Philodendron genus. These primarily include adenine-type cytokinins such as BAP, BA, Kn, and 2-isopentenyl adenine (2iP), as well as the potent phenylurea-type cytokinin TDZ [4,5,19−21]. Of these, BAP, TDZ, and Kn are frequently reported as the most effective for inducing organogenesis in

Philodendron. Building on these findings, the present study aimed to determine the optimal cytokinin and concentration for shoot proliferation of

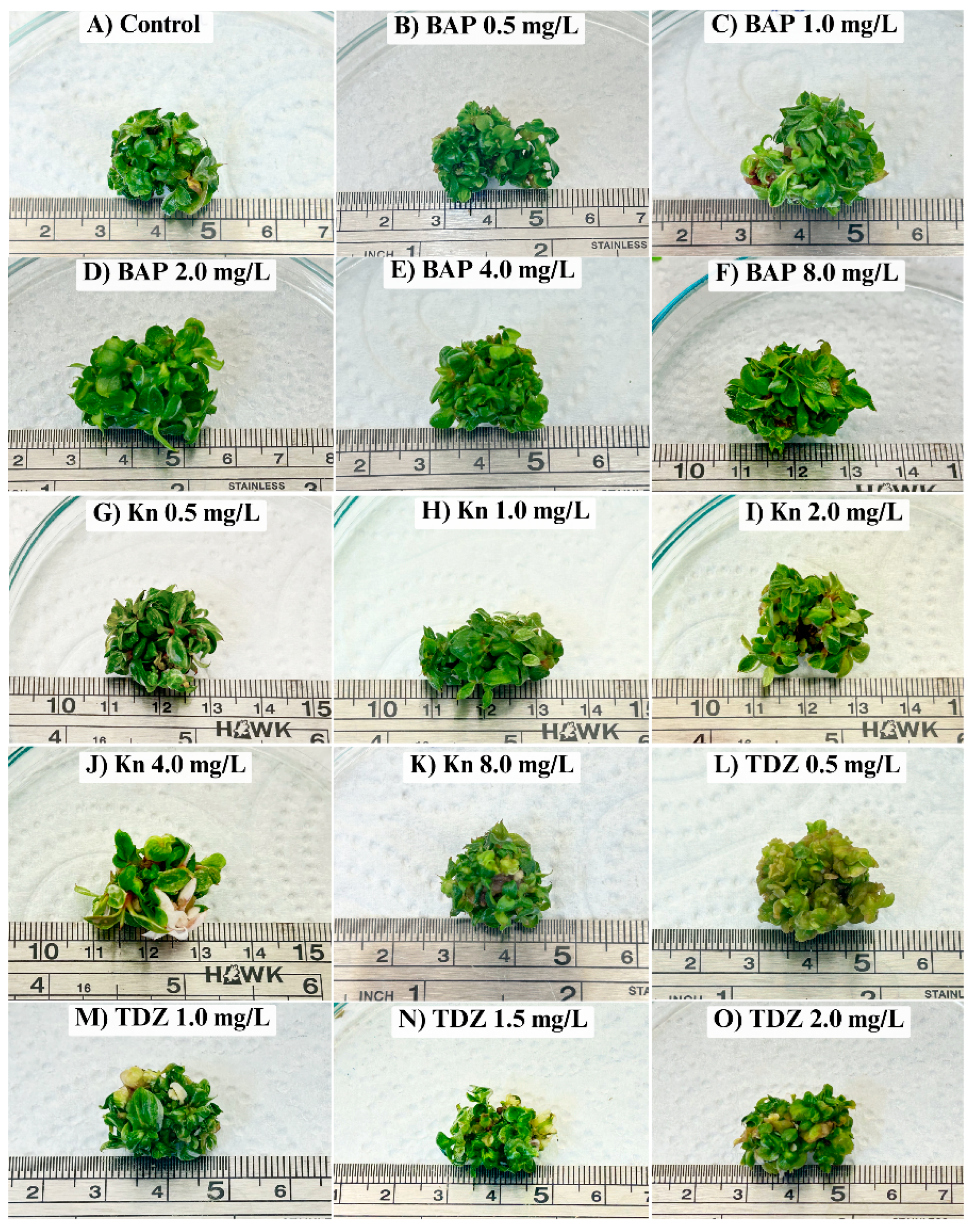

Philodendron ‘Pink Princess’. To achieve this, the effects of BAP, TDZ, and Kn were evaluated within a TIB culture system, with the results presented in

Table 2 and

Figure 1.

The experimental results, summarized in

Table 2, clearly demonstrate that BAP was significantly more effective for inducing shoot proliferation than Kn, TDZ, or the control treatment. While all tested BAP concentrations (0.5–8.0 mg/L) produced a statistically similar number of shoots, optimal shoot elongation was achieved at 1.0 and 2.0 mg/L. These treatments yielded an average of 21.4 shoots per explant with a mean shoot length of 2.4 cm after 30 days in the TIB system. This finding corroborates previous research where 1.0–2.0 mg/L BAP was identified as the optimal concentration for shoot multiplication in

P. bipinnatifidum in a semi-solid medium [

4] and

P. erubescens ‘Pink Princess’ in both semi-solid and liquid media [

5].

In contrast to the potent effects of BAP, both Kn and TDZ demonstrated significantly lower efficacy. Treatment with 1.0 mg/L Kn produced the best result among kinetin concentrations, yielding 16.7 shoots per explant, but shoot elongation was limited. This observation aligns with reports that kinetin is often less effective than BAP, a phenomenon attributed to its slower translocation rates and weaker mitogenic activity [

22]. Treatment with TDZ proved to be even less effective and, at certain concentrations, inhibitory. All TDZ treatments yielded fewer and shorter shoots than the BAP treatments, with the lowest performance (16.5 shoots/explant, 2.0 cm length) recorded at 1.5 mg/L TDZ. As shown in

Figure 1, higher TDZ concentrations led to the formation of undesirable compact and hyperhydric shoots, a common issue with this potent phenylurea-type cytokinin. This is consistent with literature indicating that while low TDZ levels can induce organogenesis, higher concentrations often become phytotoxic or induce stress responses, thereby inhibiting proper shoot development and elongation [

8,

23].

These divergent outcomes underscore that cytokinin efficacy is species-specific and highly dependent on factors such as absorption, translocation to meristematic zones, and metabolic pathways. Based on our comprehensive results, BAP was unequivocally the best choice. To develop a protocol that balances maximum proliferation with cost-effectiveness for large-scale propagation, the lower of the two most effective concentrations was selected. Therefore, a liquid MS medium supplemented with 1.0 mg/L BAP and utilized within the TIB system was established as the optimal condition for subsequent experiments.

It was noteworthy from the current study that the shoot induction rate for

Philodendron ‘Pink Princess’ in our TIB system was 2.7-fold and 1.8-fold higher than rates previously reported for semi-solid and liquid culture systems, respectively [

5]. This result underscores the superior efficacy of the TIB system for micropropagating this cultivar.

3.2. Effect of Auxin on Root Induction

Auxins are a class of phytohormones critical for establishing root system architecture, governing both adventitious and lateral root development in a dose- and type-dependent manner [

7,

24]. While previous studies have documented the successful use of various auxins for rooting

Philodendron species, these efforts have primarily relied on solid or semi-solid culture media [4,5,19−21]. To investigate the potential of liquid culture for this process, we tested three common auxins—NAA, IBA, and IAA—across a concentration range of 0.5 to 4.0 mg/L for rooting

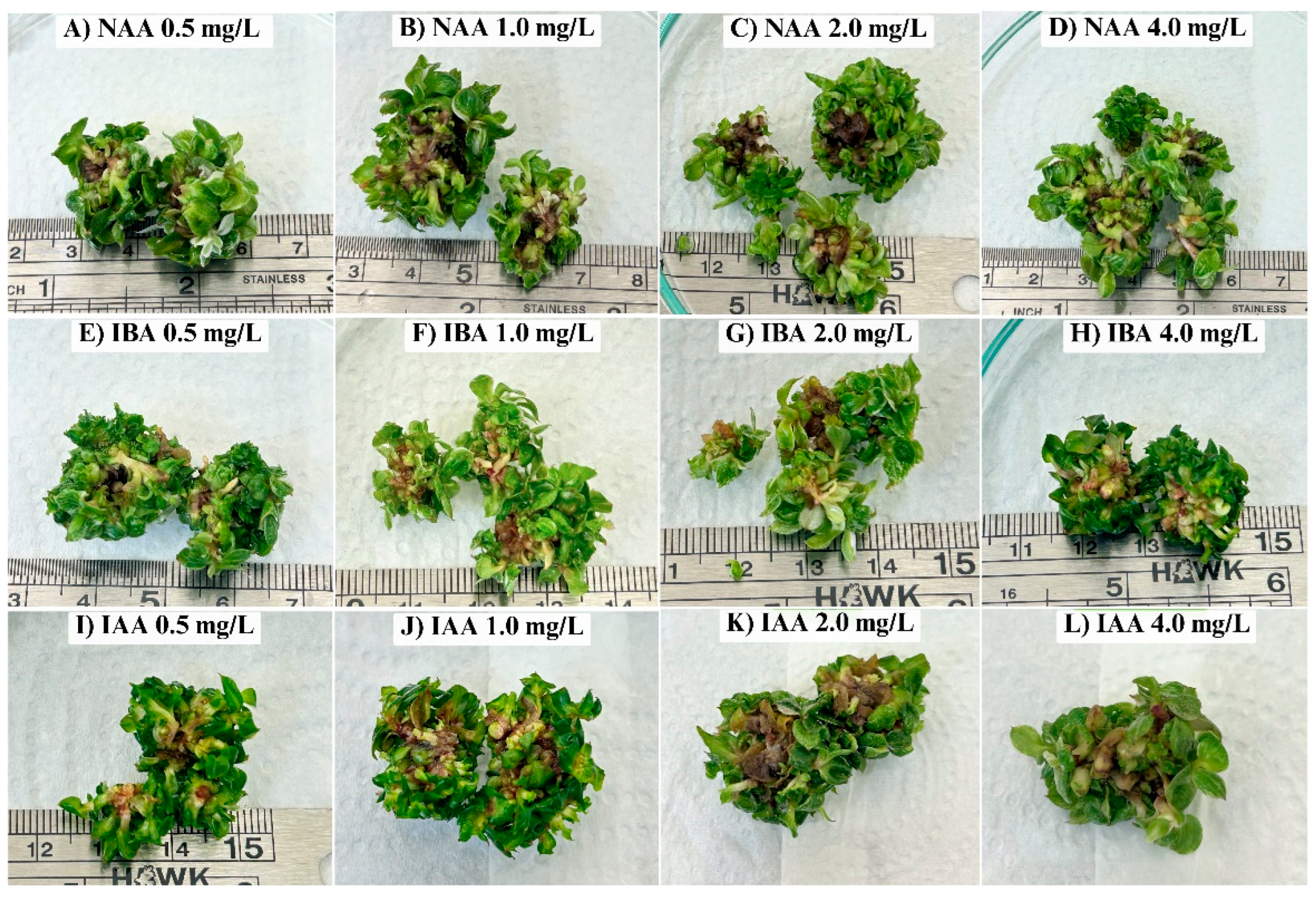

Philodendron 'Pink Princess' microshoots in a TIB system. The protocol involved an immersion frequency of 4 minutes every 8 hours. However, after a 30-day culture period, this method proved entirely unsuccessful. As illustrated in

Figure 2, root initiation was negligible across all treatments, and the plantlets exhibited severe signs of phytotoxicity, including extensive basal necrosis and a failure to thrive.

This inhibitory outcome can likely be attributed to suboptimal physical conditions within the bioreactor rather than the hormonal treatments themselves. The TIB system's efficacy relies on a delicate balance between nutrient solution immersion and gaseous exchange [

25]. The prolonged 8-hour interval between immersions may have led to excessive aeration and dehydration stress at the explant base. In response, the plantlets may have entered a state of reduced metabolic activity to conserve water, thereby preventing the energy-demanding process of root initiation. Consequently, we concluded that this TIB protocol was unsuitable, and future work must focus on optimizing immersion frequency and duration to successfully root this cultivar in a liquid system.

To isolate the effects of the auxins from the influence of the culture system, a parallel experiment was conducted on a semi-solid MS medium using the same hormonal treatments. In contrast to the TIB results, significant differences in rooting were observed (

Table 3). Both the hormone-free control and the 0.5 mg/L NAA treatment failed to produce roots, indicating an absolute requirement for exogenous auxin. While IBA induced rooting, consistent with its reported efficacy in other

Philodendron species [

21,

26,

27], its performance was suboptimal. The highest IBA concentration (4.0 mg/L) yielded the longest roots (1.2 cm) but only an average of 2.5 roots per shoot. The most effective treatment was unequivocally 0.5 mg/L IAA, which produced the highest number of roots (3.0 per shoot) with substantial length (~1.1 cm). This demonstrates IAA's high potency at low concentrations for this cultivar. However, IAA exhibited a classic dose-dependent inhibitory effect, as higher concentrations (e.g., 4.0 mg/L) significantly suppressed root elongation (~0.3 cm).

Our finding that IAA yielded a superior root system compared to NAA and IBA can be explained by their fundamental biochemical differences. As the primary natural auxin, IAA is subject to the plant's endogenous metabolic controls, allowing for rapid degradation after initiating root primordia. This transient action prevents accumulation to supraoptimal, inhibitory levels, thereby promoting the crucial subsequent stage of root elongation [

7,

28]. In contrast, the synthetic auxins NAA and IBA are more resistant to metabolic breakdown, leading to prolonged activity within the plant tissue. NAA, with its high potency and stability, frequently causes an initial burst of root primordia that subsequently fail to elongate due to persistent supraoptimal concentrations, resulting in a mass of short, callused, and non-functional roots [

29]. IBA, while also stable, is generally considered less phytotoxic. It is thought to function as a pro-drug that is slowly converted into IAA by the plant, providing a more gradual rooting stimulus. However, this conversion process is still less finely tuned than the plant's direct regulation of endogenous IAA, which accounts for the superior root morphology observed with direct IAA application in this study [

28,

30,

31].

Based on the current results, 0.5 mg/L IAA in a semi-solid medium was identified as the optimal protocol for rooting

Philodendron 'Pink Princess'. It is noteworthy that this finding contrasts with results for

P. bipinnatifidum, where NAA was superior [

4]. This discrepancy underscores a critical principle in micropropagation: the optimal type and concentration of auxin are highly species- and even cultivar-dependent.

3.3. Ex Vitro Acclimatization of the Plantlets

The transition from sterile, high-humidity

in vitro conditions to a non-sterile, low-humidity

ex vitro environment is a critical bottleneck in micropropagation. Successful acclimatization, which ensures plantlet survival and vigor, is highly dependent on the choice of growing substrate [

21]. An ideal substrate must provide a balanced environment that supports fragile, newly-formed roots with adequate aeration, moisture retention, and physical support. While numerous materials have been tested, such as sand, cocopeat, peat moss, perlite, vermiculite, and soilrite [

5,

27,

32,

33], composite substrates combining peat moss (for water/nutrient retention), perlite (for aeration and drainage), and vermiculite (for moisture retention and cation exchange) are often cited for superior performance [

4,

26].

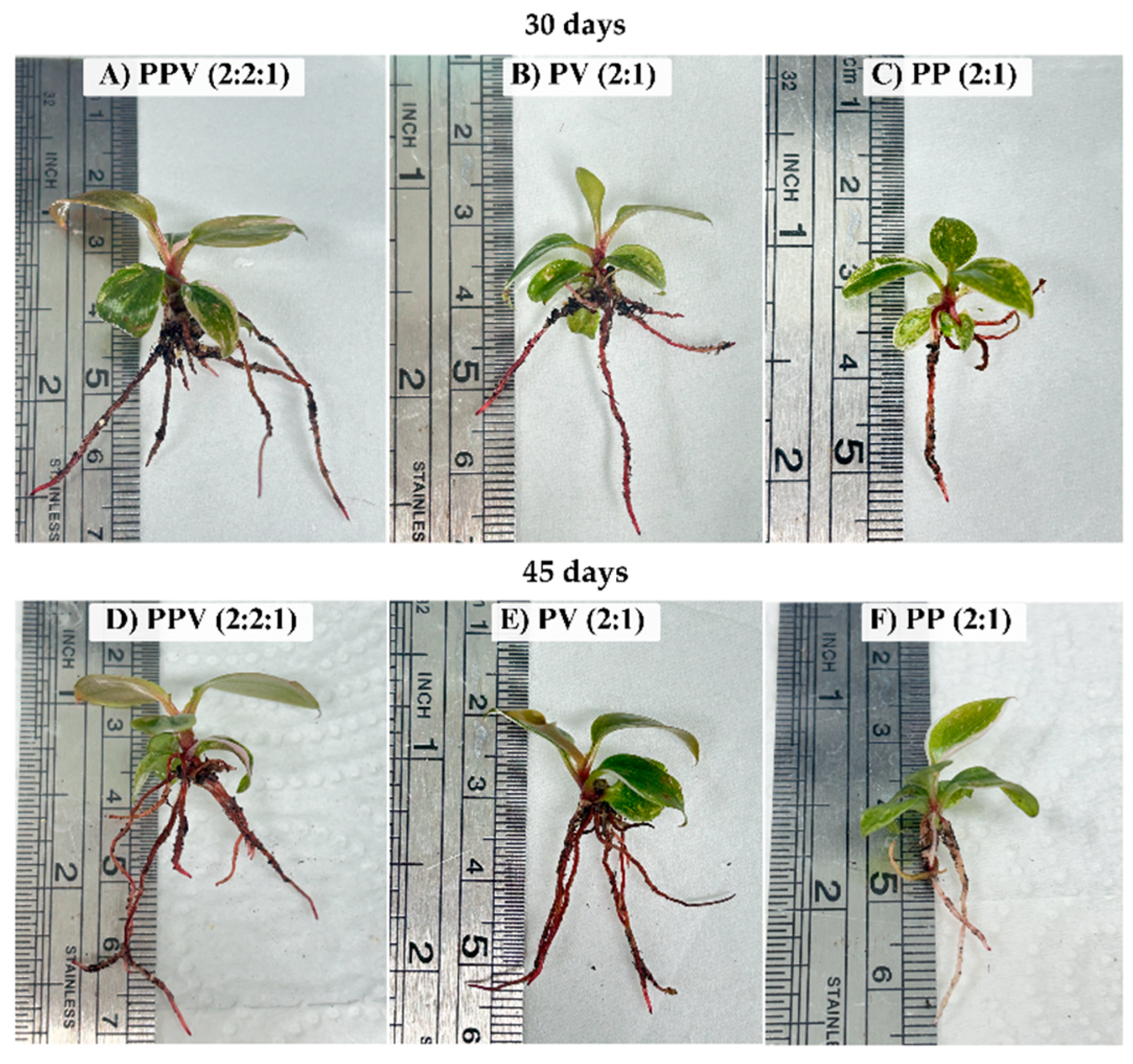

Building on this knowledge, we evaluated three substrate mixtures for the

ex vitro acclimatization of

Philodendron 'Pink Princess'. The most effective formulation was unequivocally a 2:1:1 ratio of peat moss, perlite, and vermiculite (PPV). This substrate yielded a 100% survival rate and promoted significantly superior growth across all measured parameters, including leaf number, root number, root length, and plant height, at both 30 days and 45 days post-transplant (

Table 4,

Figure 3). The success of this mixture can be attributed to the synergistic effect of its components, which created an optimal balance between water availability, nutrient absorption, and root zone aeration [

4,

26].

In comparison, substrate mixtures lacking one component were less effective. Both the 2:1 peat moss/vermiculite (PV) mixture and the 2:1 peat moss/perlite (PP) mixture resulted in a reduced survival rate of 90%. Notably, the plantlets in the PV mixture exhibited better overall growth than those in the PP mixture. This suggests that the water-retaining properties of vermiculite were more critical for this species' initial establishment than the enhanced aeration provided by perlite, a finding that aligns with reports on other plants like tea clones [

34], wasabi [

35], and banana [

9,

3][

38].

3.4. Assessment of Genetic Stability of Micropropagated Plantlets

Maintaining the genetic integrity of micropropagated plants is paramount, as the stresses of

in vitro culture can induce somaclonal variation—genetic or epigenetic changes that may compromise desirable traits [

39]. Factors such as explant source, culture type, culture duration, and the specific combinations of PGRs can disrupt cellular stability and lead to off-types, undermining the goal of clonal propagation [40−42]. Consequently, assessing the genetic fidelity of regenerated plants is a critical quality control measure.

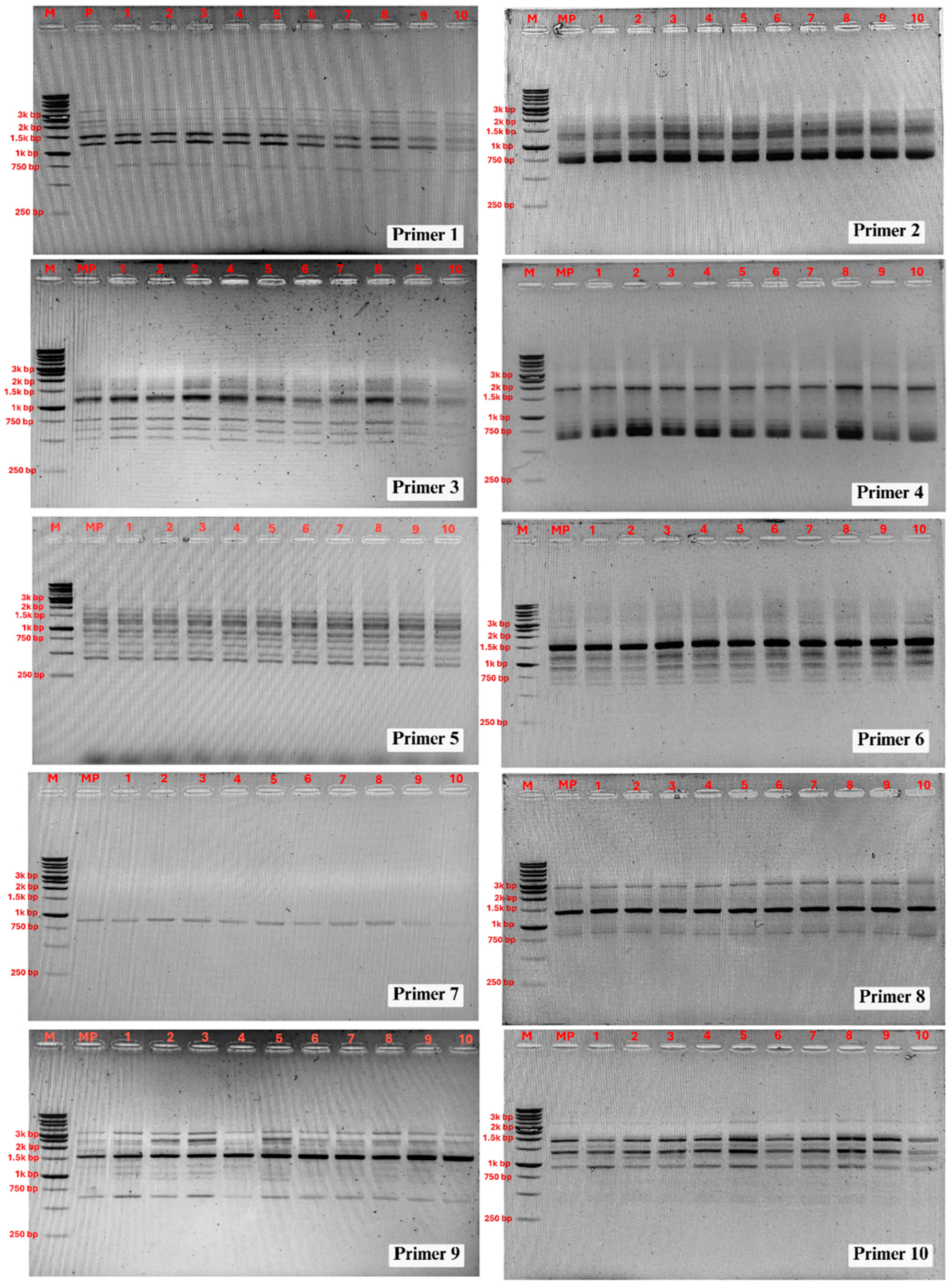

In this study, RAPD analysis was employed to evaluate the genetic stability of TIB-regenerated

Philodendron ‘Pink Princess’ plantlets against the original mother plant. A total of 10 primers were used to screen 10 randomly selected clones. The primers generated a total of 73 clear and reproducible bands ranging from 400 to 3500 bp, with an average of 7.3 bands per primer (

Table 1). The amplified DNA profiles for all 10 clones were monomorphic and identical to that of the mother plant, revealing no detectable polymorphism (

Figure 4). This result confirms that the developed TIB protocol facilitates true-to-type clonal multiplication of

Philodendron ‘Pink Princess’.

The high genetic fidelity observed in this study indicates that the TIB system, under the conditions tested, provides a stable environment for the clonal propagation of this cultivar. These findings align with previous reports where high genetic stability was confirmed in other micropropagated aroids, such as

Anthurium andreanum (using ISSR markers) and

P. bipinnatifidum (using RAPD markers) [

4,

43]. The absence of variation suggests that the protocol successfully mitigates the primary factors known to induce somaclonal variation.

However, while RAPD markers are sensitive for detecting broad genomic changes [

44,

45], they are known to have limitations, including issues with reproducibility and dominance. For robust validation intended for commercial-scale production, employing multiple, more advanced marker systems is highly recommended [

15,

46]. Future work should focus on corroborating these findings using co-dominant markers or those with higher reproducibility, such as ISSR and SCoT markers. SCoT markers, which are based on functional gene regions, are particularly promising due to their high reliability and are increasingly used for both genetic diversity and fidelity assessments [47−49]. Such multi-marker validation would provide the highest level of confidence in the genetic integrity of the propagated plantlets.

4. Conclusions

This research successfully establishes a comprehensive and highly efficient micropropagation protocol for the commercially valuable ornamental, P. erubescens ‘Pink Princess’. The study demonstrates the superiority of a hybrid approach, leveraging a TIB system for the shoot proliferation stage and a semi-solid medium for rooting. The TIB system, when supplied with MS medium containing 1.0 mg/L BAP, proved ideal for rapid shoot multiplication, yielding nearly 21 shoots per explant while preventing hyperhydricity. For the subsequent rooting stage, a transition to a semi-solid MS medium supplemented with 0.5 mg/L IAA was essential, indicating that constant, stable contact with the rooting hormone is more critical for adventitious root formation in this cultivar than the intermittent immersion provided by the TIB. This two-step process overcomes the common limitations of both static liquid and solid culture systems. The resulting plantlets were not only morphologically robust but also genetically stable, as confirmed by RAPD analysis, which showed 100% clonal fidelity with the mother plant. This genetic uniformity, combined with a 100% survival rate during ex vitro acclimatization in a peat-perlite-vermiculite substrate, validates the reliability of the entire pipeline from lab to greenhouse. In summary, the integrated protocol developed herein provides a scalable, efficient, and genetically stable method for the mass propagation of P. erubescens ‘Pink Princess’. This work offers a significant advancement for commercial growers seeking to meet market demand and provides a robust model for the conservation and propagation of other valuable Araceae species.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.K., S.T. and P.T.; methodology, B.K.V., P.K., S.T. and P.T.; software, P.T.; validation, P.K., S.T. and P.T.; formal analysis, B.K.V., P.K., S.T. and P.T.; investigation, B.K.V. and S.T.; resources, P.K. and P.T.; data curation, P.K., S.T. and P.T.; writing—original draft preparation, B.K.V., S.T. and P.T.; writing—review and editing, P.K., S.T. and P.T.; visualization, B.K.V. and P.T.; supervision, P.K. and P.T.; project administration, P.T.; funding acquisition, P.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Research Program funding from the Research and Innovation Department, Khon Kaen University (grant number: RP68-6-Research Center-001). A part of this research was also supported by the International Affairs Division, Faculty of Technology, and Department of Biotechnology, Khon Kaen University, through Khon Kaen University Scholarship for ASEAN & GMS countries’ personnel.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Prof. Mamoru Yamada (Yamaguchi University) for his invaluable guidance and suggestions throughout the experimental work and manuscript preparation. The authors also acknowledge the Department of Biotechnology, Faculty of Technology, Khon Kaen University, for providing the necessary facilities and resources for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mayo, S.J. A Revision of Philodendron Subgenus Meconostigma (Araceae). Kew Bull. 1991, 46, 601. [CrossRef]

- Croat, T.B. A Revision of Philodendron Subgenus Philodendron (Araceae) for Mexico and Central America. Ann. Mo. Bot. Gard. 1997, 84, 311–704. [CrossRef]

- Chiewchan, N.; Saetiew, K.; Teerarak, M. The effect of BA on inducing shoots of Philodendron erubescens ‘Pink Princes’ in vitro. Int. J. Agric. Technol. 2023, 19, 23852398.

- Alawaadh, A.A.; Dewir, Y.H.; Alwihibi, M.S.; Aldubai, A.A.; El-Hendawy, S.; Naidoo, Y. Micropropagation of Lacy Tree Philodendron (Philodendron bipinnatifidum Schott ex Endl.). HortScience 2020, 55, 294–299. [CrossRef]

- Klanrit, P.; Kitwetcharoen, H.; Thanonkeo, P.; Thanonkeo, S. In Vitro propagation of Philodendron erubescens ‘Pink Princess’ and ex vitro acclimatization of the plantlets. Horticulturae. 2023, 9, 688.

- Yunita, R.; I Nugraha, M.F. Effect of auxin type and concentration on the induction of Alternanthera Reineckii roots in vitro. IOp Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 653, 012073.

- Sosnowski, J.; Truba, M.; Vasileva, V. The Impact of Auxin and Cytokinin on the Growth and Development of Selected Crops. Agriculture 2023, 13, 724. [CrossRef]

- Han, B.-H.; Park, B.-M. In vitro micropropagation of Philodendron cannifolium. J. Plant Biotechnol. 2008, 35, 203–208. [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, T.; İnan, S.; Dündar, İ. Comparison of temporary immersion bioreactor (SETISTM) and classical solid culture in micropropagation of ‘Grand Naine’ (Musa spp.) banana cultivar. J. Agri. Sci. 2023, 15, 5160.

- Gupta, S.D.; Prasad, V.S.S. Matrix-supported liquid culture systems for efficient micropropagation of floricultural plants. Floriculture, Ornamental and Plant Biotechnology: Advances and Tropical Issue. 2006, 2, 488495.

- Uma, S.; Karthic, R.; Kalpana, S.; Backiyarani, S.; Saraswathi, M.S. A novel temporary immersion bioreactor system for large scale multiplication of banana (Rasthali AAB—Silk). Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Rai, M.K.; Phulwaria, M.; Harish; Gupta, A.K.; Shekhawat, N.S.; Jaiswal, U. Genetic homogeneity of guava plants derived from somatic embryogenesis using SSR and ISSR markers. Plant Cell, Tissue Organ Cult. (PCTOC) 2012, 111, 259–264. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.K.; Harish; Rai, M.K.; Phulwaria, M.; Agarwal, T.; Shekhawat, N. In vitro propagation, encapsulation, and genetic fidelity analysis of Terminalia arjuna: A cardioprotective medicinal tree. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2014, 173, 1481–1494.

- Alwahibi, M.S.; Alawaadh, A.A.; Dewir, Y.H.; Soliman, D.A.; Seliem, M.K. Assessment of genetic fidelity of lacy tree philodendron (Philodendron bipinnatifidum Schott ex Endl.) micro propagated plants. Bionatura 2022, 7, 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Al-Aizari, A.A.; Dewir, Y.H.; Ghazy, A.-H.; Al-Doss, A.; Al-Obeed, R.S. Micropropagation and genetic fidelity of Fegra Fig (Ficus palmata Forssk.) and grafting compatibility of the regenerated plants with Ficus carica. Plants. 2024, 13, 1278.

- Kieber, J.J.; Schaller, G.E. Cytokinin signaling in plant development. Development 2018, 145, dev149344. [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, S.S.; Mekureyaw, M.F.; Pandey, C.; Roitsch, T. Role of Cytokinins for Interactions of Plants With Microbial Pathogens and Pest Insects. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 10, 1777. [CrossRef]

- Emery, R.J.N.; Kisiala, A. The Roles of Cytokinins in Plants and Their Response to Environmental Stimuli. Plants 2020, 9, 1158. [CrossRef]

- Khamrit, R.; Jongrungklang, N. Determining Optimal Mutation Induction of Philodendron billietiae Using Gamma Radiation and In Vitro Tissue Culture Techniques. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 1164. [CrossRef]

- Maikaeo, L.; Puripunyavanich, M.; Limtiyayotin, M.; Orpong, P.; Kongpeng, C. Micropropagation and gamma irradiation mutagenesis in Philodendron billietiae. Thai J. Agric. Sci. 2024, 57, 1119.

- Kang, I.; Sivanesan, I. Micropropagation of Philodendron ‘White Knight’ via shoot regeneration from petiole explants. Plants. 2025, 14, 1714.

- Klaocheed, S.; Jehsu, W.; Choojun, W.; Thammasiri, K.; Prasertsongskun, S.; Rittirat, S. Induction of Direct Shoot Organogenesis from Shoot Tip Explants of an Ornamental Aquatic Plant, Cryptocoryne wendtii. Walailak J. Sci. Technol. (WJST) 2018, 17, 293–302. [CrossRef]

- Dewir, Y.H.; Nurmansyah; Naidoo, Y.; da Silva, J.A.T. Thidiazuron-induced abnormalities in plant tissue cultures. Plant Cell Rep. 2018, 37, 1451–1470. [CrossRef]

- Wiesman, Z.; Riov, J.; Epstein, E. Comparison of movement and metabolism of indole-3-acetic acid and indole-3-butyric acid in mung bean cuttings. Physiologia Plantarum. 1988, 74, 556560.

- Ahmadian, M.; Babaei, A.; Shokri, S.; Hessami, S. Micropropagation of carnation ( Dianthus caryophyllus L . ) in liquid medium by temporary immersion bioreactor in comparison with solid culture. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2017, 15, 309–315. [CrossRef]

- Hassan, H.M.S.; Ali, M.A.M.; Soliman, D.A. EFFECT OF LOW COST GELLING AGENTS AND SOME GROWTH REGULATORS ON MICROPROPAGATION OF Philodendron selloum. J. Plant Prod. 2016, 7, 169–176. [CrossRef]

- Akramian, M.; Khaleghi, A.; Arjmand, H.S. Optimization of plant growth regulators for in vitro mass propagation of Philodendron cv. Birkin through shoot tip culture. Greenh. Plant Prod. J. 2024, 1, 55–62. [CrossRef]

- Woodward, A.W.; Bartel, B. Auxin: regulation, action, and interaction. Ann. Bot. 2005, 95, 707−735.

- Hausman, J.F. Changes in peroxidase activity, auxin level and ethylene production during root formation by poplar shoots raised in vitro. Plant Growth Regul. 1993, 13, 263–268. [CrossRef]

- Epstein, E.; Ludwig-Müller, J. Indole-3-butyric acid in plants: Occurrence, synthesis, metabolism and transport. Physiol. Plant. 1993, 88, 382–389.

- Epstein, E.; Sagee, O.; Zelcer, A. Uptake and metabolism of indole-3-butyric acid and indole-3-acetic acid by Petunia cell suspension culture. Plant Growth Regul. 1993, 13. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.I.; Ahmad, N.; Anis, M. The role of cytokinins on in vitro shoot production in Salix tetraspera Roxb.: a tree of ecological importance. Trees. 2011, 25, 577584.

- Abdalla, N.; Ragab, M.; El-Miniawy, S.; Arafa, N.; Taha, H. A New Aspect for In vitro Propagation of Jerusalem Artichoke and Molecular Assessment Using RAPD, ISSR and SCoT Marker Techniques. Egypt. J. Bot. 2020, 61, 203–218. [CrossRef]

- Gonbad, R.A; Moghaddam, S.S.; Sinniah, U.R.; Aziz, M.A.; Safarpour, M. Determination of potting media for effective acclimatization in micropropagated plants of tea clone Iran 100. Int. J. Forest Soil Erosion. 2013, 3, 4044.

- Hoang, N.N.; Kitaya, Y.; Shibuya, T.; Endo, R. Effects of supporting materials in in vitro acclimatization stage on ex vitro growth of wasabi plants. Sci. Hortic. 2020, 261. [CrossRef]

- Erol, M.H.; Dönmez, D.; Biçen, B.; Şimşek, Ö.; Kaçar, Y.A. Modern Approaches to In Vitro Clonal Banana Production: Next-Generation Tissue Culture Systems. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 1154. [CrossRef]

- Uma, S.; Karthic, R.; Kalpana, S.; Backiyarani, S. Evaluation of temporary immersion bioreactors for in vitro micropropagation of banana (Musa spp.) and genetic fidelity assessment using flow cytometry and simple-sequence repeat markers. South Afr. J. Bot. 2023, 157, 553–565. [CrossRef]

- Thanonkeo, S.; Kitwetcharoen, H.; Thanonkeo, P.; Klanrit, P. Temporary immersion bioreactor (TIB) system for large-scale micropropagation of Musa sp. cv Kluai Numwa Pakchong 50. Horticulturae. 2024, 10, 1030.

- Krishna, H.; Alizadeh, M.; Singh, D.; Singh, U.; Chauhan, N.; Eftekhari, M.; Sadh, R.K. Somaclonal variations and their applications in horticultural crops improvement. 3 Biotech 2016, 6, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Lal, D.; Singh, N. Mass multiplication of Celastrus paniculatus Willd: An important medicinal plant under in vitro conditions via nodal segments. Int. J. Biodivers. Conserv. 2010, 2, 140–145.

- Bairu, M.W.; Aremu, A.O.; Van Staden, J. Somaclonal variation in plants: causes and detection methods. Plant Growth Regul. 2010, 63, 147–173. [CrossRef]

- Premvaranon, P.; Vearasilp, S.; Thanapornpoonpong, S.-N.; Karladee, D.; Gorinstein, S. In vitro studies to produce double haploid in Indica hybrid rice. Biologia 2011, 66, 1074–1081. [CrossRef]

- Gantait, S.; Mandal, N.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Das, P.K. In vitro Mass Multiplication with Pure Genetic Identity in Anthurium andreanum Lind.. Plant Tissue Cult. Biotechnol. 1970, 18, 113–122. [CrossRef]

- El-Banna, A.; Khatab, I. ASSESSING GENETIC DIVERSITY OF SOME POTATO (Solanum tuberosum L.) CULTIVARS BY PROTEIN AND RAPD MARKERS. Egypt. J. Genet. Cytol. 2013, 42, 89–101. [CrossRef]

- Salama, D.M.; Osman, S.A.; Abd EL-Aziz, M.; Abd ELwahed, M.S.; Shaaban, E. Effect of zinc oxide nanoparticles on the growth, genomic DNA, production and the quality of common dry bean (Phaseolus vulgaris). Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2019, 18, 101083.

- Lakshmanan, V.; Venkataramareddy, S.R.; Neelwarne, B. Molecular analysis of genetic stability in long-term micropropagated shoots of banana using RAPD and ISSR markers. Electron. J. Biotechnol. 2007, 10. [CrossRef]

- Cabo, S.; Ferreira, L.; Carvalho, A.; Martins-Lopes, P.; Martín, A.; Lima-Brito, J.E. Potential of Start Codon Targeted (SCoT) markers for DNA fingerprinting of newly synthesized tritordeums and their respective parents. J. Appl. Genet. 2014, 55, 307–312. [CrossRef]

- Fang-Yong, C.; Ji-Hong, L. Germplasm genetic diversity of Myrica rubra in Zhejiang Province studied using inter-primer binding site and start codon-targeted polymorphism markers. Sci. Hortic. 2014, 170, 169–175. [CrossRef]

- Thakur, J.; Dwivedi, M.D.; Sourabh, P.; Uniyal, P.L.; Pandey, A.K. Genetic homogeneity revealed using SCoT, ISSR and RAPD markers in micropropagated Pittosporum eriocarpum Royle-an endemic and endangered medicinal plant. PLoS ONE. 2016, 11, e0159050.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).