1. Introduction

Lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) are the gateway technology among rechargeable batteries, consisting of various chemistries and compositions that typically include lithium as a key component in the cathode and electrolyte. Initially, LIBs were primarily used in consumer electronics. However, their applications have rapidly expanded in recent years, particularly in battery electric vehicles (BEVs) and large-scale energy storage systems. This growth has significantly increased global demand for LIBs, driven by their high energy density, lightweight design, and declining production costs.

Despite the focus on lithium, LIBs also rely on other critical and finite materials such as cobalt, manganese, and graphite. These materials are often sourced from a limited number of countries, raising concerns about supply chain stability and long-term availability [

1]. Since their commercial introduction in the early 1990s, the use of LIBs has grown exponentially. This trend is expected to continue, fueled by advances in technology and a growing push toward clean energy alternatives [

2,

3]. However, the increasing demand also highlights a key challenge: the limited global reserves of the raw materials necessary for LIB production.

This scarcity underscores the importance of developing efficient recycling strategies to ensure resource sustainability [

4,

5]. Recycling plays a crucial role not only in reducing environmental impact but also in recovering valuable materials that would otherwise be lost during disposal [

6]. End-of-life (EoL) LIBs can be managed through three main strategies: remanufacturing, repurposing, and recycling—each assessed based on the battery’s State of Health (SoH). While remanufacturing and repurposing aim to extend the functional lifespan of batteries, recycling is essential for reclaiming core materials once batteries reach complete degradation [

7]. Unfortunately, in many parts of the world, particularly across Africa, LIB recycling infrastructure remains underdeveloped [

8]. Poor disposal practices—such as dumping LIBs in unregulated landfills—pose serious health and environmental risks due to the presence of toxic metals and flammable organic compounds [

9,

10,

11].

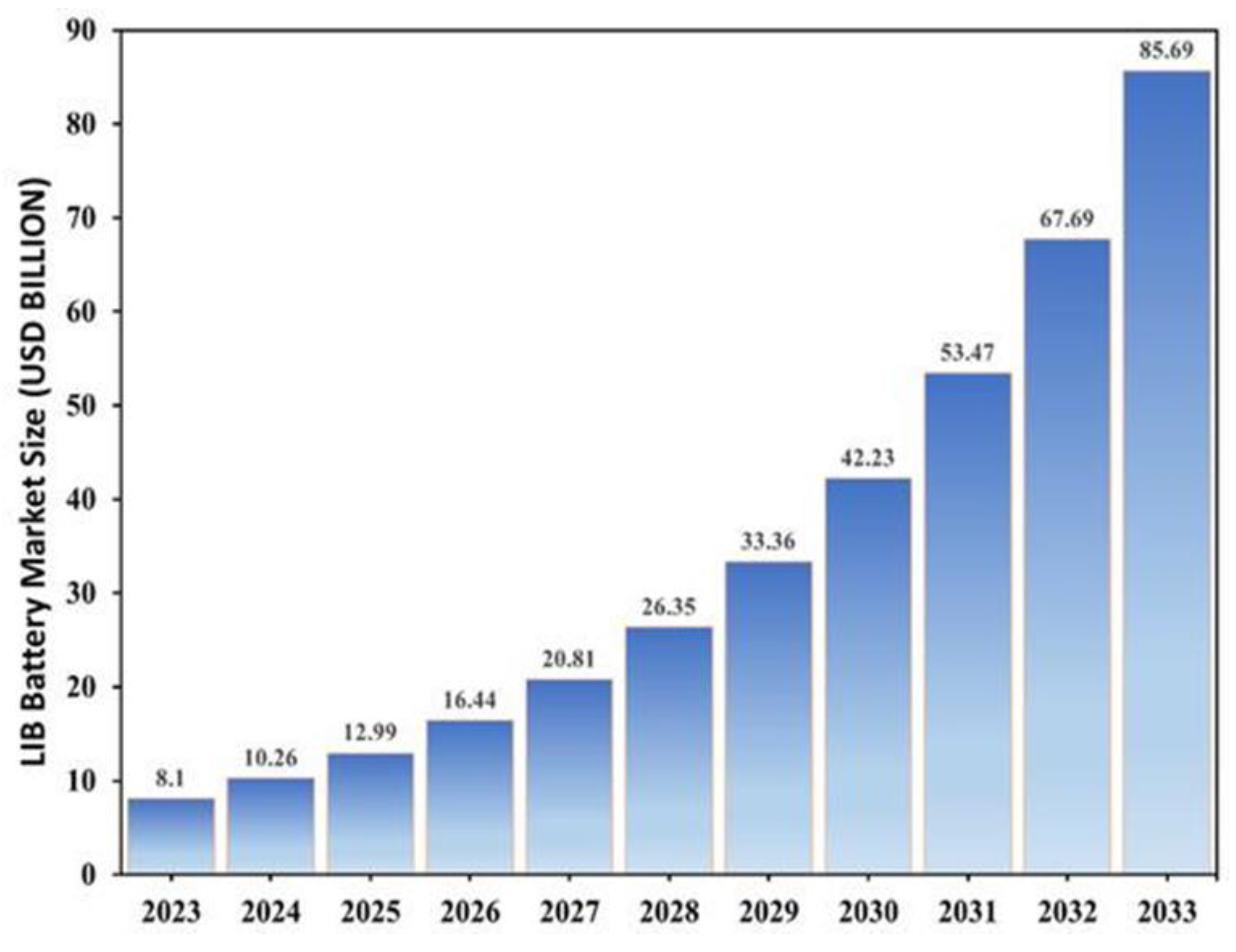

According to market data, the global LIB recycling industry was valued at USD 8.10 billion in 2023 and is projected to reach USD 10.26 billion in 2024. As illustrated in

Figure 1, the market is expected to expand significantly, reaching approximately USD 85.69 billion by 2033 at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 26.6% [

12]. This growth reflects not only rising demand for sustainable battery management but also the economic potential of circular solutions such as resource recovery and job creation [

13]. Additionally, the required global battery capacity is anticipated to increase from approximately 700 GWh in 2022 to 4.7 TWh by 2030 [

14], intensifying the urgency for scalable and effective end-of-life battery solutions.

In response to this global and regional challenge, this study explores practical, low-cost methods for recovering and repurposing spent lithium-ion batteries, particularly within resource-constrained environments. The research focuses on evaluating battery performance through discharging and recharging cycles, assessing safe dismantling practices, and examining the potential of recovered batteries for low-energy applications. Through this work, we aim to contribute toward sustainable LIB waste management and demonstrate feasible approaches for extending the usable life of batteries, ultimately supporting broader efforts toward e-waste reduction and circular economy development.

1.1. Role of Artificial Intelligence in Recycling

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is playing a transformative role across industries, with growing significance in environmental sustainability. In battery recycling, one impactful branch of AI—Computer Vision (CV)—enables systems to interpret and analyze visual data, facilitating the automatic recognition, classification, and tracking of battery types. This has proven especially useful in the sorting and processing of battery waste (B-waste), where accuracy and speed are essential.

CV systems are widely adopted in fields such as object detection and industrial automation and are increasingly being integrated into B-waste management. These systems automate critical tasks such as identifying battery chemistry, determining physical condition, and guiding robotic or conveyor-based sorting mechanisms [

15]. As the complexity and volume of waste grow, CV is expected to play a central role in streamlining the processes of identification, classification, collection, segregation, and monitoring of recyclable materials [

16].

Current sorting solutions use a combination of manual labor and machine learning (ML) algorithms, including Support Vector Machines (SVMs) and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) for material classification [

17]. Technologies like Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) are also employed for contactless identification and tracking of waste streams [

18]. For example, ZenRobotics’ ZRR2 robot in Finland demonstrates the efficacy of combining deep learning and CV in sorting construction waste [

19].

The application of AI and ML in recycling has not only increased operational efficiency but also improved the accuracy of material recovery. These technologies process vast datasets much faster than human operators, enabling faster decision-making and reducing error rates. In the context of battery recycling, ML algorithms can help distinguish between healthy and degraded cells, predict reuse potential, and optimize safe disassembly.

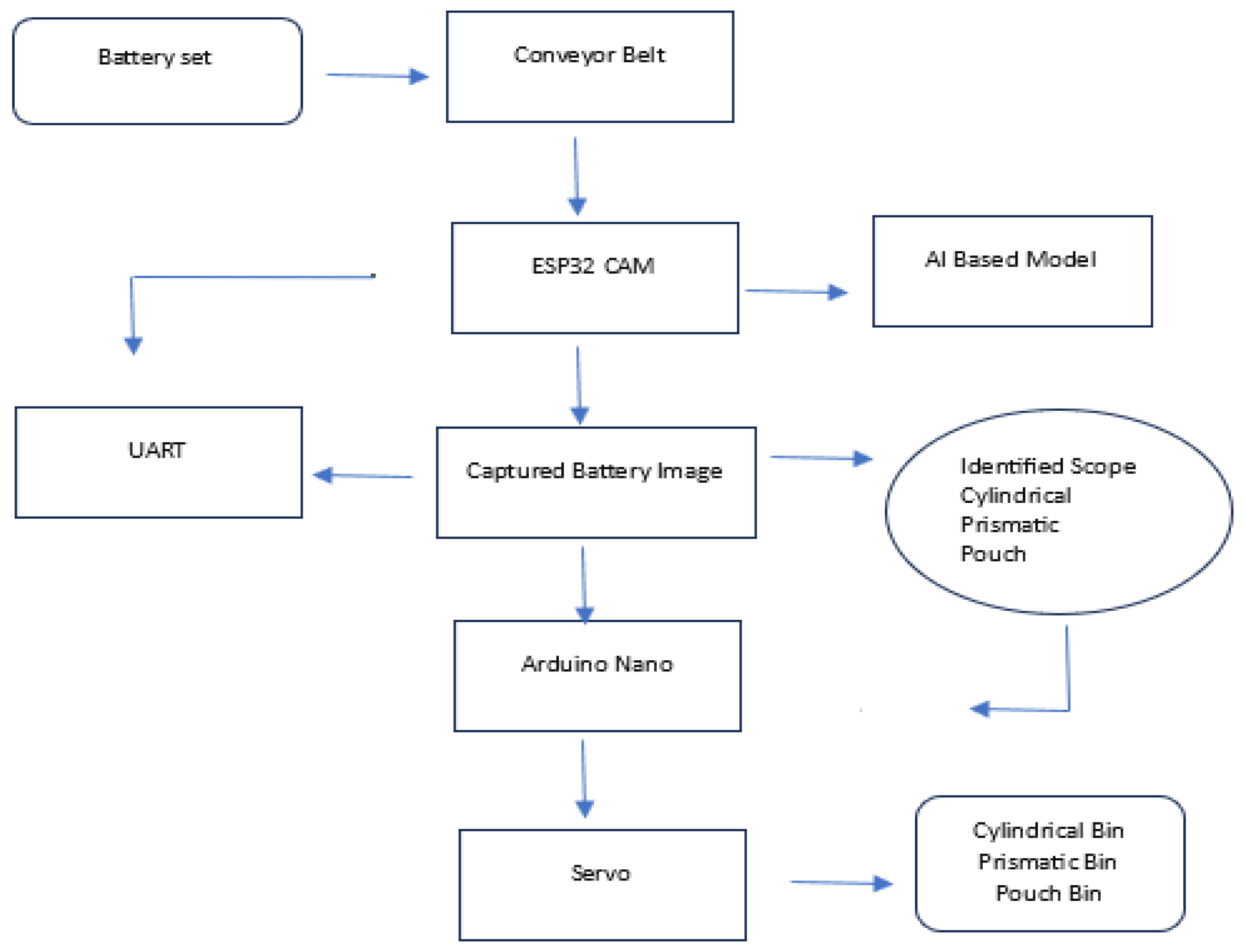

Building upon these advances, this study proposes the development of a lightweight computer vision-based classification system for lithium-ion battery recycling. The system utilizes embedded AI models deployed on resource-constrained microcontrollers (e.g., ESP32-CAM) to perform real-time battery identification and sorting based on physical characteristics. Unlike cloud-based systems, this edge deployment model is designed to function offline, making it suitable for use in low-resource settings or rural environments where internet connectivity is limited or unavailable.

This system addresses three key challenges:

Model compression and deployment – Ensuring that trained models can run efficiently on devices with limited memory and processing power.

Real-time classification – Achieving sufficient inference speed for timely sorting decisions.

Robustness across variations – Ensuring reliable classification despite variations in battery size, wear, and markings.

Several studies have highlighted the challenges of deploying deep learning models on embedded devices, including issues related to model size, inference time, power consumption, and limited computational resources. Techniques such as model quantization, pruning, and knowledge distillation have been explored to overcome these limitations [

20,

21,

22].

This work contributes to the field by applying these principles in a real-world B-waste context, demonstrating how AI-powered, low-cost solutions can enhance circular economy practices in emerging economies.

1.2. Repurposing for Smaller Applications

Discarding cellphone and laptop batteries has raised concerns about possible second use, especially since current recycling resources for lithium-ion (Li-ion) batteries remain insufficient [

23]. While lead-acid battery recycling is well established, recycling systems for Li-ion technologies are still in early stages. From both economic and environmental standpoints, it is inefficient to discard batteries that still retain usable capacity. The financial and labor investments required to produce these batteries—along with the rising costs of critical raw materials—underscore the need for second-life strategies [

24].

A prime example is lithium cobalt oxide (LCO), a widely used cathode material in consumer electronics and electric vehicles (EVs). Cobalt, although essential, is scarce—comprising only 0.0023% of the Earth’s crust—and primarily mined in regions of geopolitical instability, particularly in the Democratic Republic of Congo. These factors have led to steep price hikes, with cobalt soaring from USD 26,500 per ton in September 2016 to USD 94,250 per ton in March 2018 [

25]. Repurposing such batteries maximizes the value extracted from these expensive materials and helps delay costly and inefficient recycling efforts.

Research by [

26] estimates that by 2040, approximately 3.4 million kg of Li-ion battery cells from EVs may enter the waste stream, containing both non-recyclable materials (e.g., graphite) and high-energy-demand materials (e.g., lithium, nickel, aluminum, cobalt). Yet, direct recycling is often impractical due to the complexity and high energy cost of material recovery. For instance, lithium only constitutes 2–7% of a battery

’s total weight, and extracting it via recycling is up to five times more expensive than sourcing it naturally [

27]. Presently, cobalt is the only material with viable recycling returns, but industry efforts are underway to develop cobalt-free chemistries that are cheaper and more sustainable [

27].

In this context, our study prioritizes battery repurposing over recycling as an interim and practical solution. Repurposing extends battery utility without the high energy and infrastructure demands associated with full recycling processes. This approach supports circular economy principles and helps reduce e-waste while preserving economic value. It also aligns with global sustainability objectives such as the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

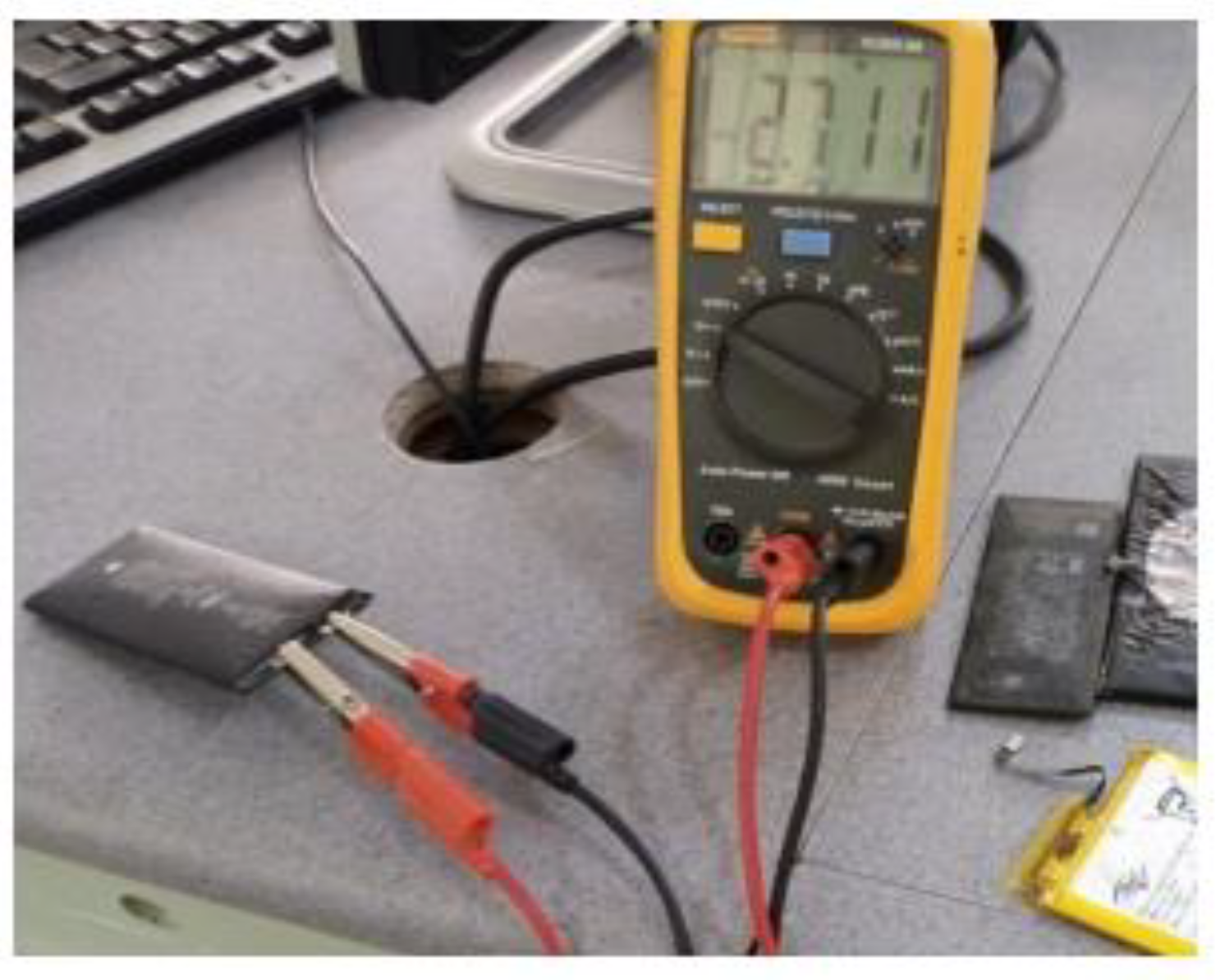

To ensure safe reuse, [

28] proposes a three-stage assessment method. First, a visual inspection identifies physically damaged cells for immediate rejection. Second, a voltage check filters out critically degraded units. Finally, the state of health (SoH) evaluation, typically embedded in a Battery Management System (BMS), quantifies the remaining capacity and predicts lifespan. While SoH estimation remains challenging due to nonlinear battery behavior, it is essential for reliable and safe operation [

29].

In our study, recovered batteries that passed SoH evaluation were repurposed for low-power applications such as powering LED desk lamps, Bluetooth headphones, and emergency power banks. These devices operate within safe voltage and current limits, minimizing risk. When repurposing batteries for such uses, adherence to safety standards is crucial. Guidelines such as IEC 62133 (for secondary cells and batteries in portable applications) and UN Manual of Tests and Criteria, Part III, Subsection 38.3 (for transport safety) provide essential protocols for assessing battery safety post-reuse. Furthermore, national directives like the U.S. EPA’s Battery Safety Best Practices or the EU Battery Directive also inform safe handling and reuse of Li-ion batteries in non-critical systems [

30].

By following such standards and applying rigorous assessment protocols, second-life applications for Li-ion batteries can be safely and responsibly implemented—bridging the gap until scalable, cost-effective recycling becomes widely available.

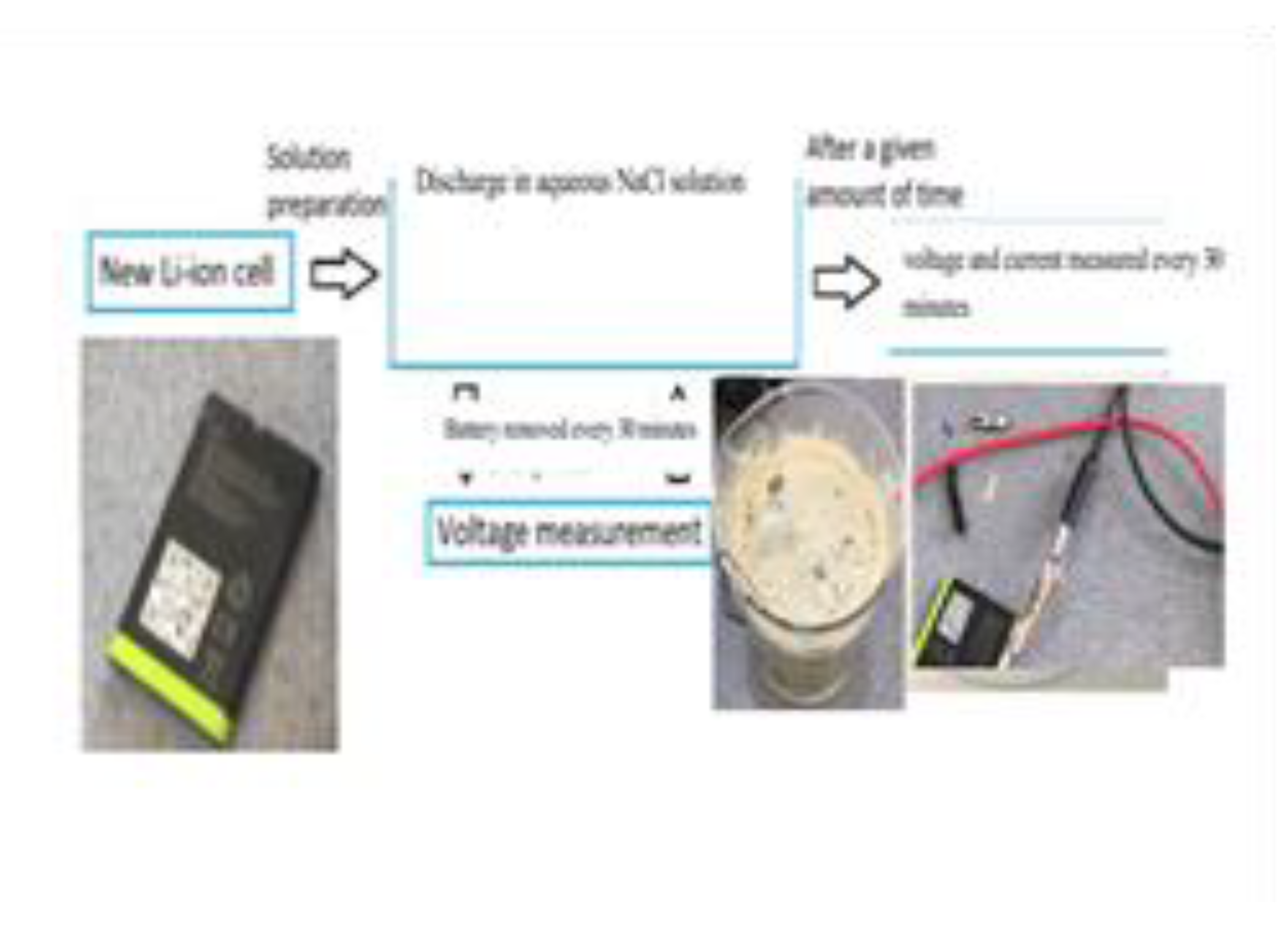

1.3. Discharge with NaCl

Before lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) can be safely dismantled or recycled, residual electrical energy must be neutralized to avoid hazards such as thermal runaway, electric shock, or short circuits. Among the available discharge methods, immersion in sodium chloride (NaCl) brine solution has emerged as a cost-effective, simple, and relatively safe technique [

28]. However, while effective in energy neutralization, post-discharge brine presents environmental management challenges that must be addressed early in any end-of-life battery treatment system.

Discharged LIBs may release trace heavy metals such as cobalt, nickel, and manganese, which can leach into the brine during immersion. Furthermore, the electrochemical reactions in high-salinity brine can lead to hydrogen gas generation and pH fluctuations, which in turn increase the corrosiveness of the solution and pose hazards to waste treatment systems. A drop in pH below 5 or a rise above 9 is especially significant, as it indicates a shift in leachate chemistry, potentially mobilizing toxic ions into solution [

31]. As a result, post-discharge brine should be treated as hazardous waste, requiring neutralization (e.g., via lime or sodium hydroxide) and filtration before disposal or reuse [

32]. Environmental regulations in regions like the EU and US mandate such precautions to avoid secondary pollution and groundwater contamination.

In this context, discharging charged LIBs via brine immersion offers a safer and more controlled alternative to direct short-circuiting or resistive discharging, especially for small-scale and low-resource recycling settings [

28]. This technique relies on the ionic conductivity of saline water, which enables gradual dissipation of stored energy through the conductive medium. Typically, a 10% NaCl solution can reduce the voltage of a standard 18650 cell to below 1 V in less than 12 hours without significant temperature rise or gas evolution [

31]. However, the discharge rate is influenced by battery design, state of charge, electrolyte leakage, and electrolyte/binder degradation over time.

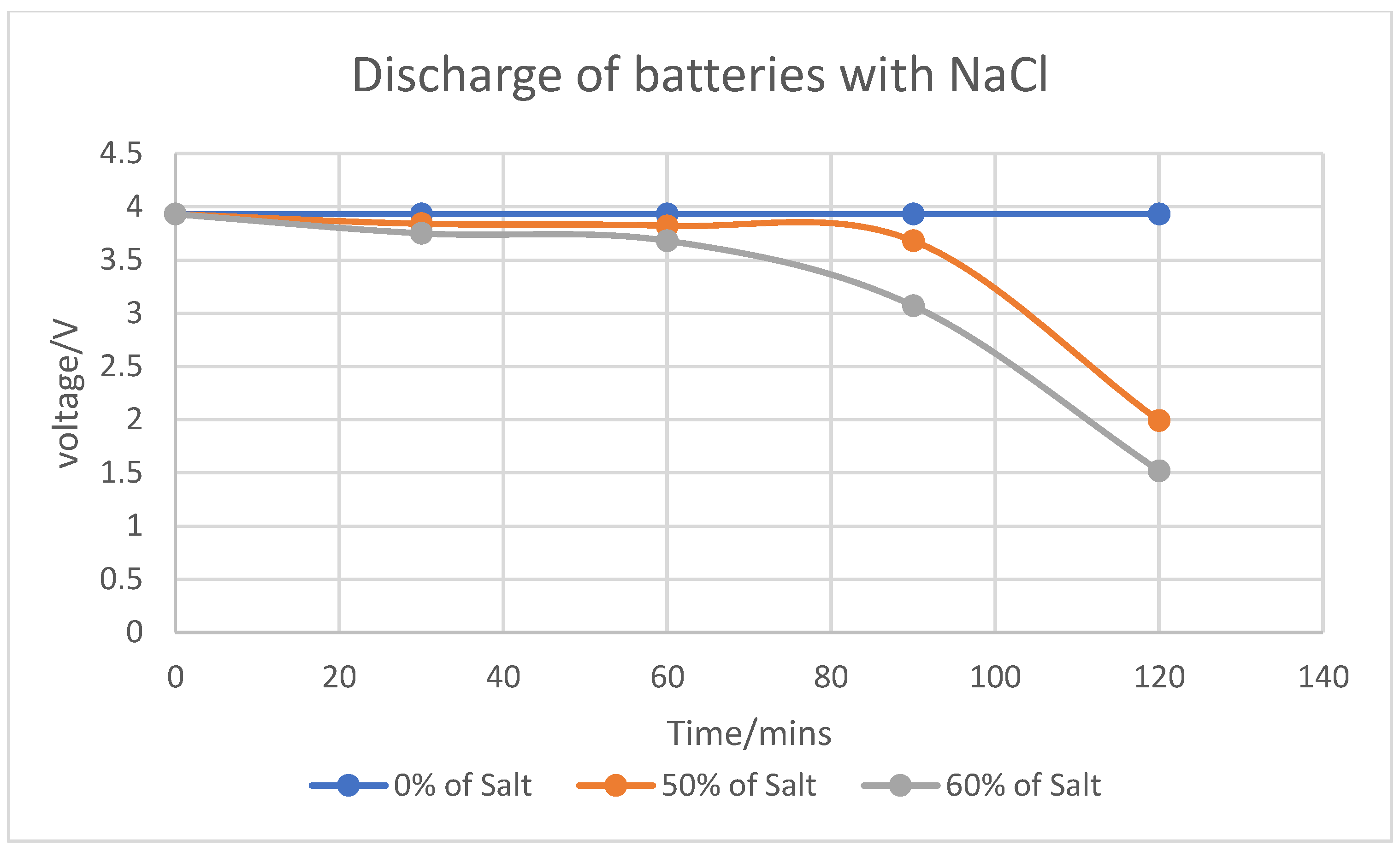

Higher salt concentrations—such as 50% or 60% NaCl—can significantly accelerate discharge, reducing time to less than 6 hours. However, this increase in concentration also raises risks of electrode corrosion, brine contamination, and excess hydrogen gas generation, which can pose flammability risks in confined spaces [

30]. Studies show that 10–15 wt% NaCl provides an optimal balance between safety, discharge efficiency, and minimal side reactions [

31]. Nonetheless, prolonged immersion—even at moderate concentrations—can lead to structural degradation of electrodes and electrolyte components, further contaminating the brine.

In our study, we integrate this discharge technique within a broader framework for LIB circularity. Specifically, we present a low-cost, AI-powered LIB sorting and management system using the ESP32-CAM microcontroller, capable of classifying batteries by geometry (cylindrical, prismatic, pouch) without relying on high-performance computing platforms. Post-sorting, batteries undergo voltage-based screening and controlled recharging, followed by discharge profiling and safe pack formation for second-life applications.

To evaluate energy neutralization efficiency, we immersed various cells in 50% and 60% NaCl solutions, observing full discharge within 3–5 hours. However, electrolyte leakage, visible corrosion, and pH drop from ~7.5 to below 5 were observed, reinforcing the need for brine pH stabilization and post-treatment. These findings support recommendations for environmental discharge management and underscore the importance of coupling electrochemical protocols with waste treatment strategies.

This work offers a practical and affordable approach to small-scale LIB repurposing, combining AI-driven battery identification, embedded health assessment, and electrochemical safety protocols with consideration for environmental discharge trade-offs.

5. Conclusions

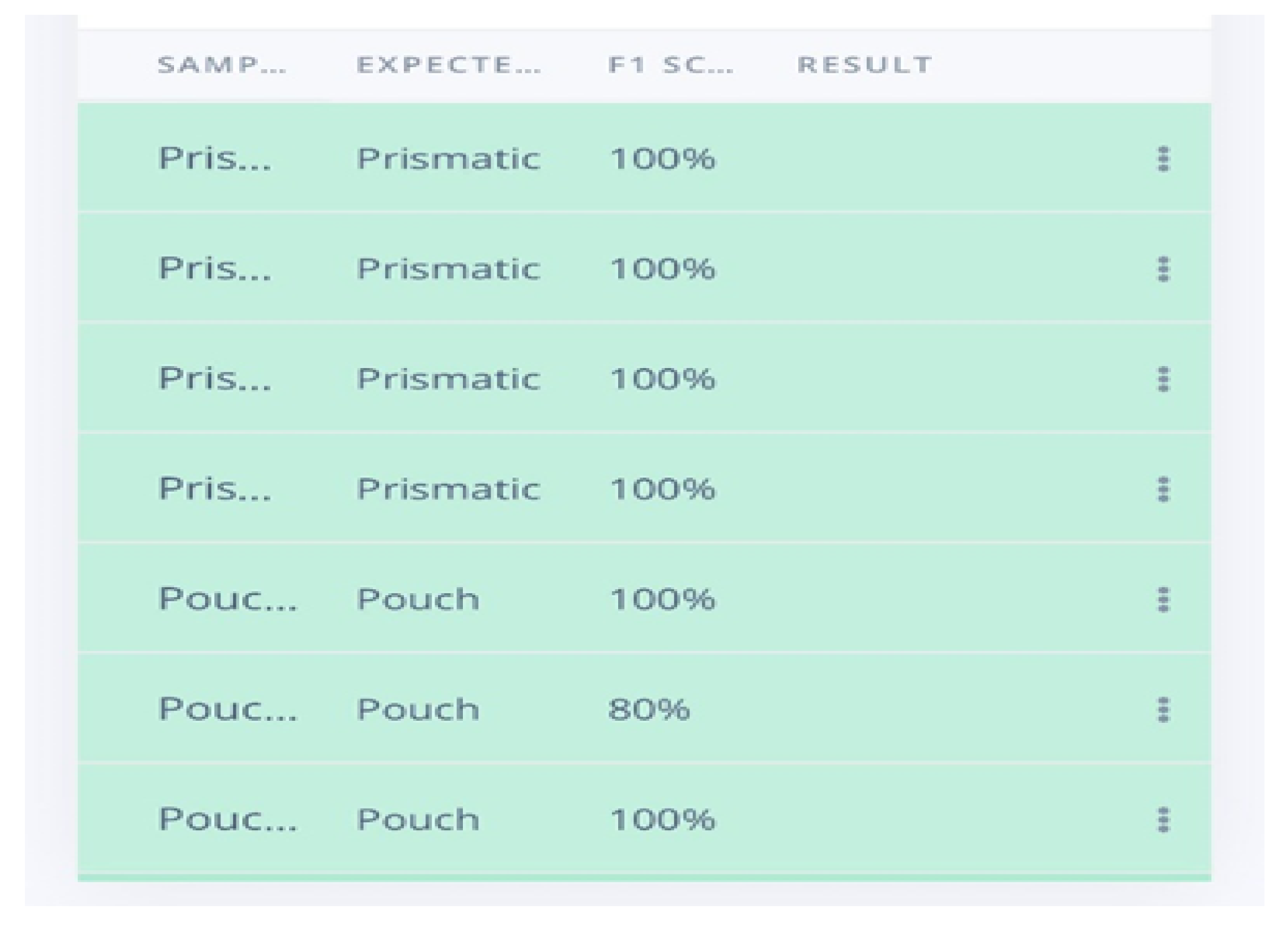

5.1. LIB Separator

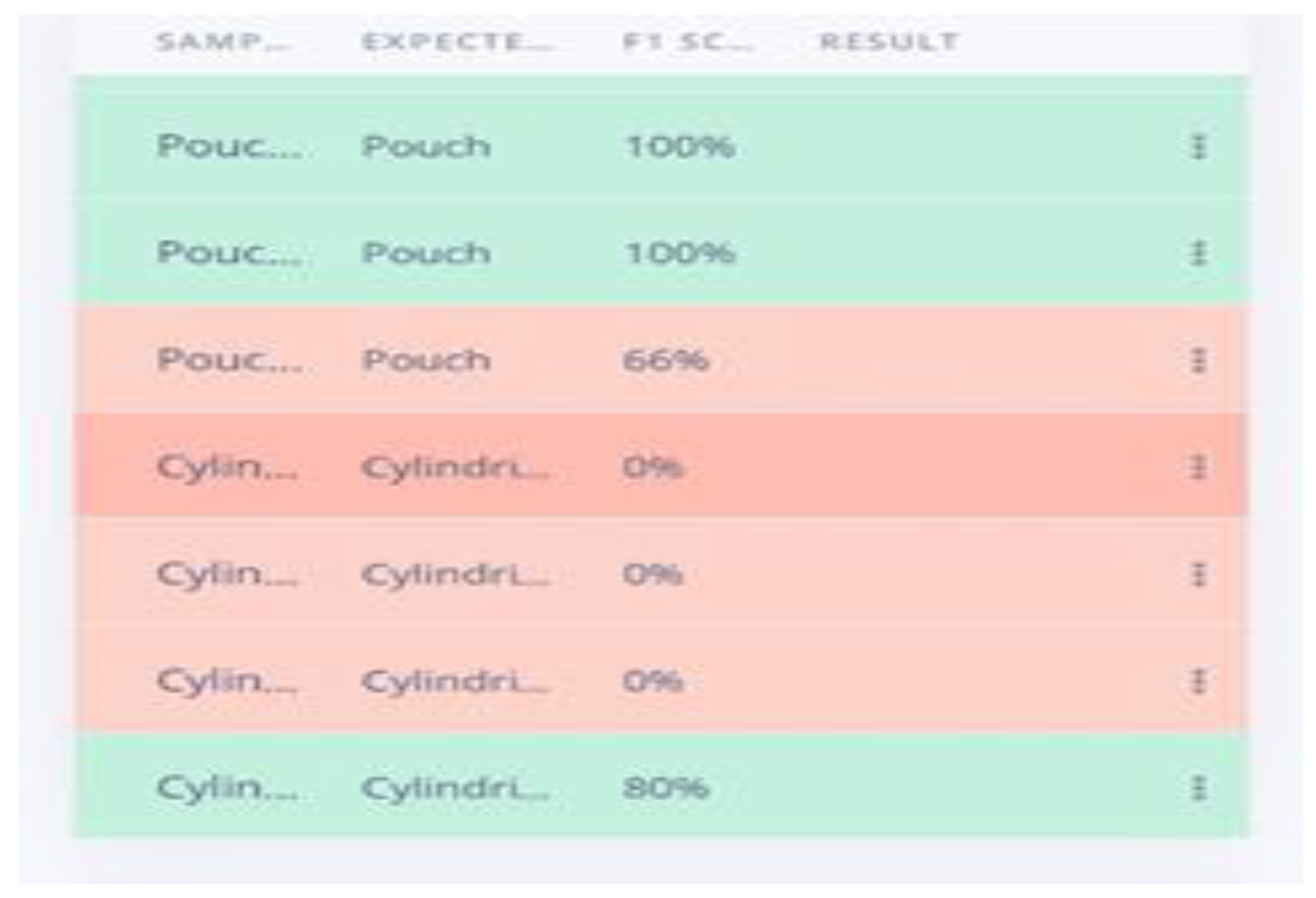

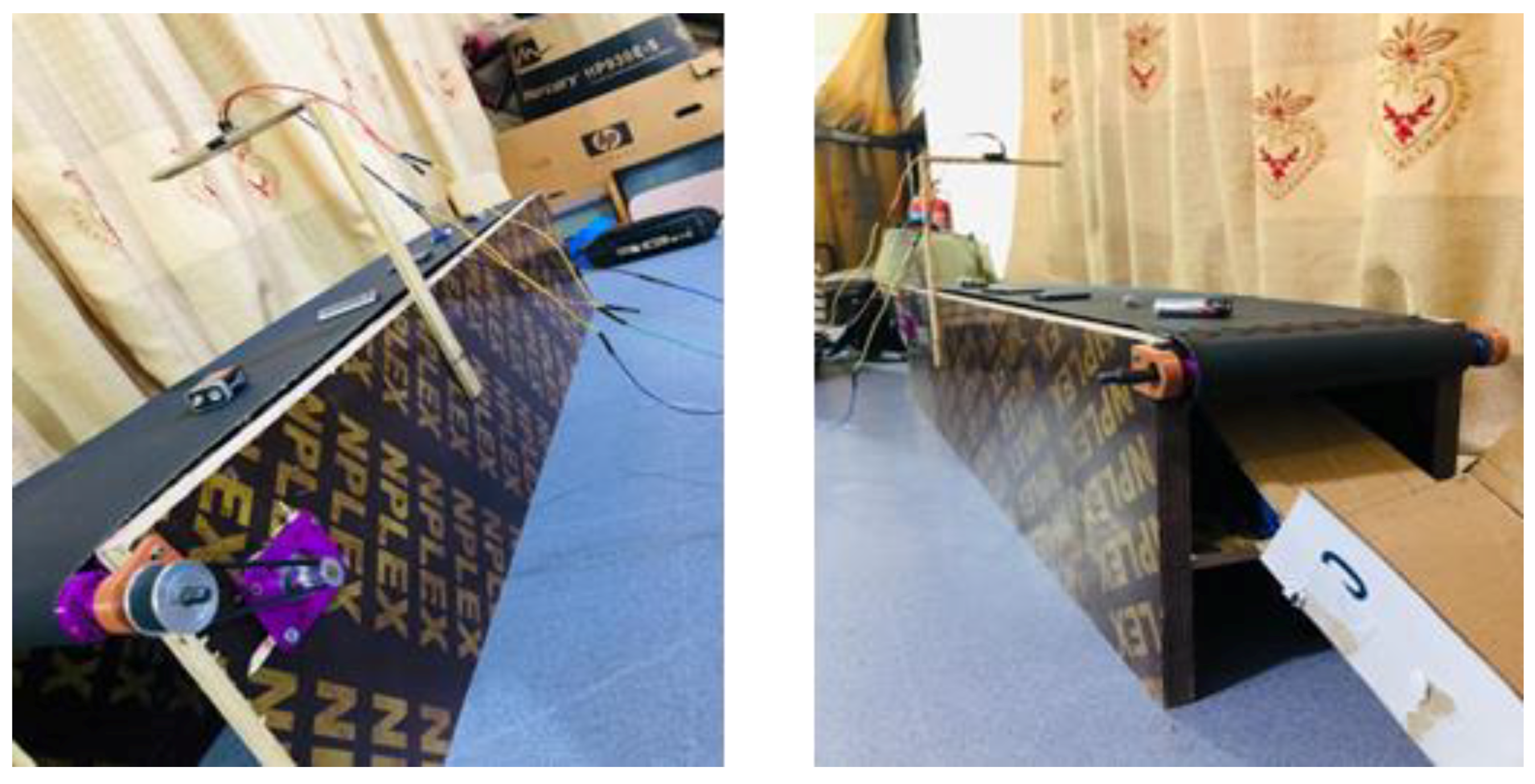

The research advanced the development of an AI-powered LIB separator designed to enhance the safety and efficiency of battery recycling processes. This system incorporated machine learning models trained to identify cylindrical, pouch, and prismatic batteries based on shape and direct them to designated collection points via a conveyor belt system. Despite promising results, the real-time application was impacted by limited processing power and environmental lighting conditions, leading to inconsistencies in performance. This highlights the importance of ongoing optimization to ensure reliable battery sorting under variable conditions.

The ESP-32’ robustness in operation would have been a cause for the 69.23% accuracy; a higher value was expected than that. The accuracy is believed to have reduced to the type and orientation of the cylindrical batteries’ recall and precision. The output wasn’t what was expected, with a device of high resolution like the Raspberry Pi it is believed that the system will work without flaws.

5.2. Characterization and Repurposing

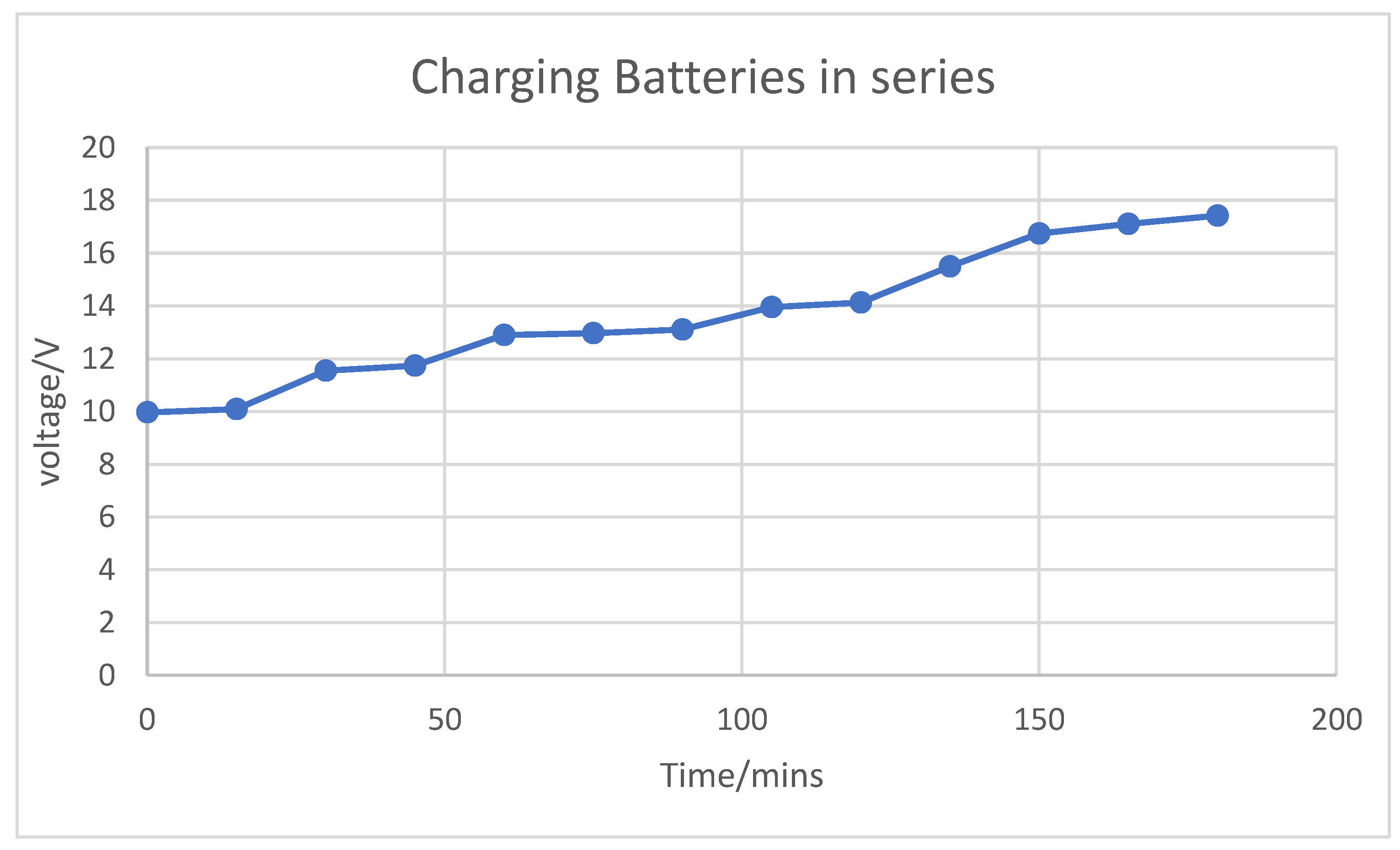

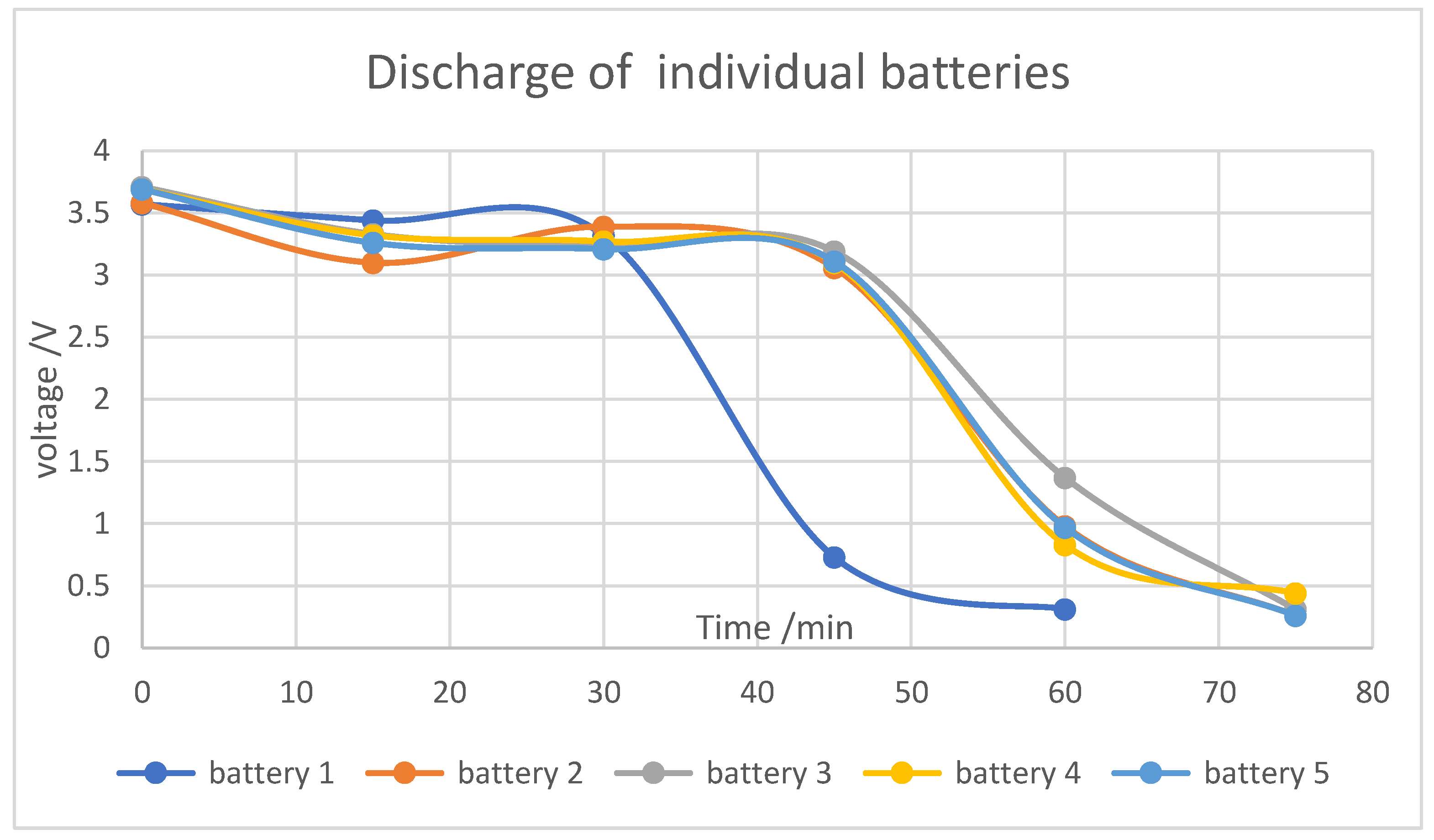

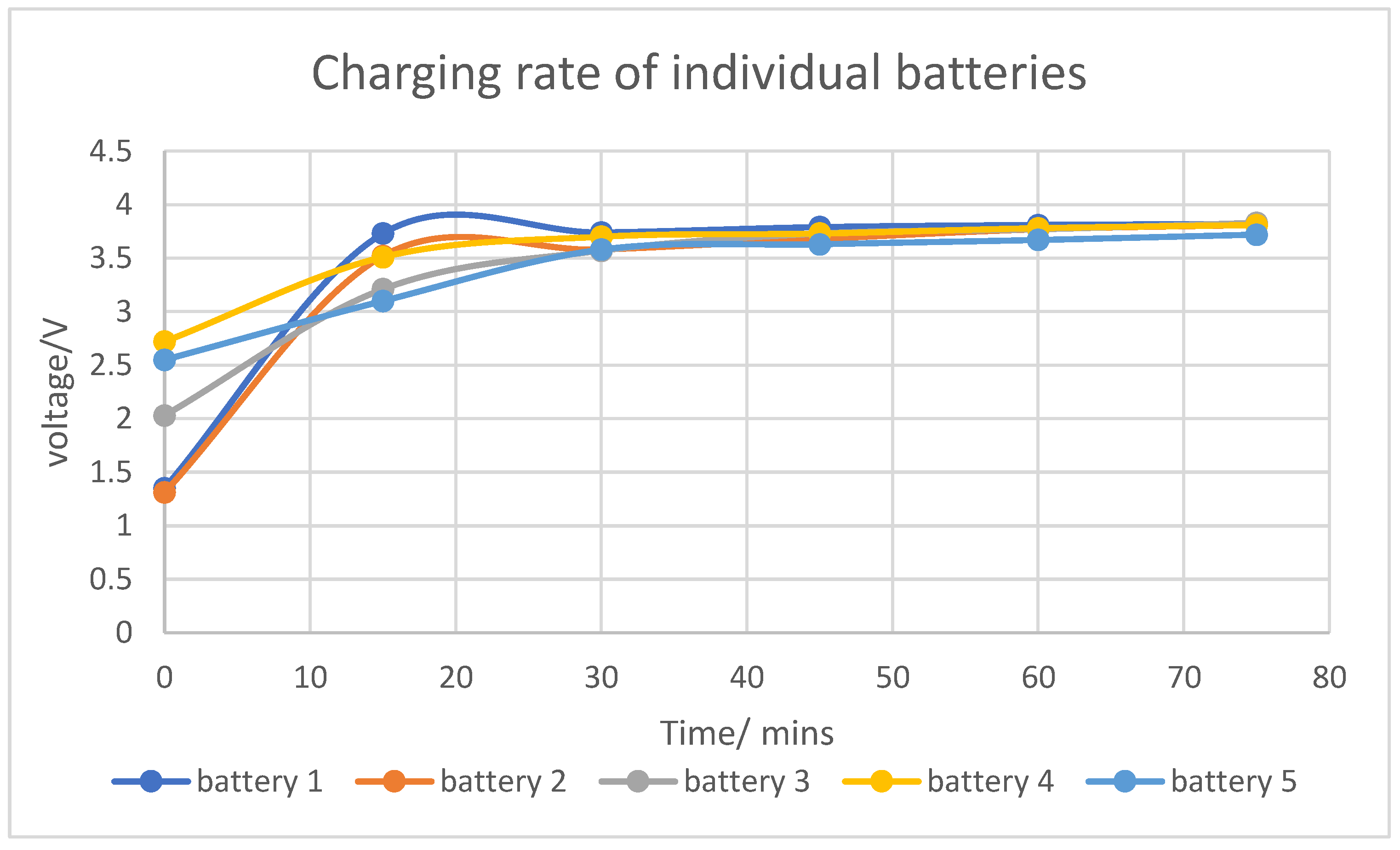

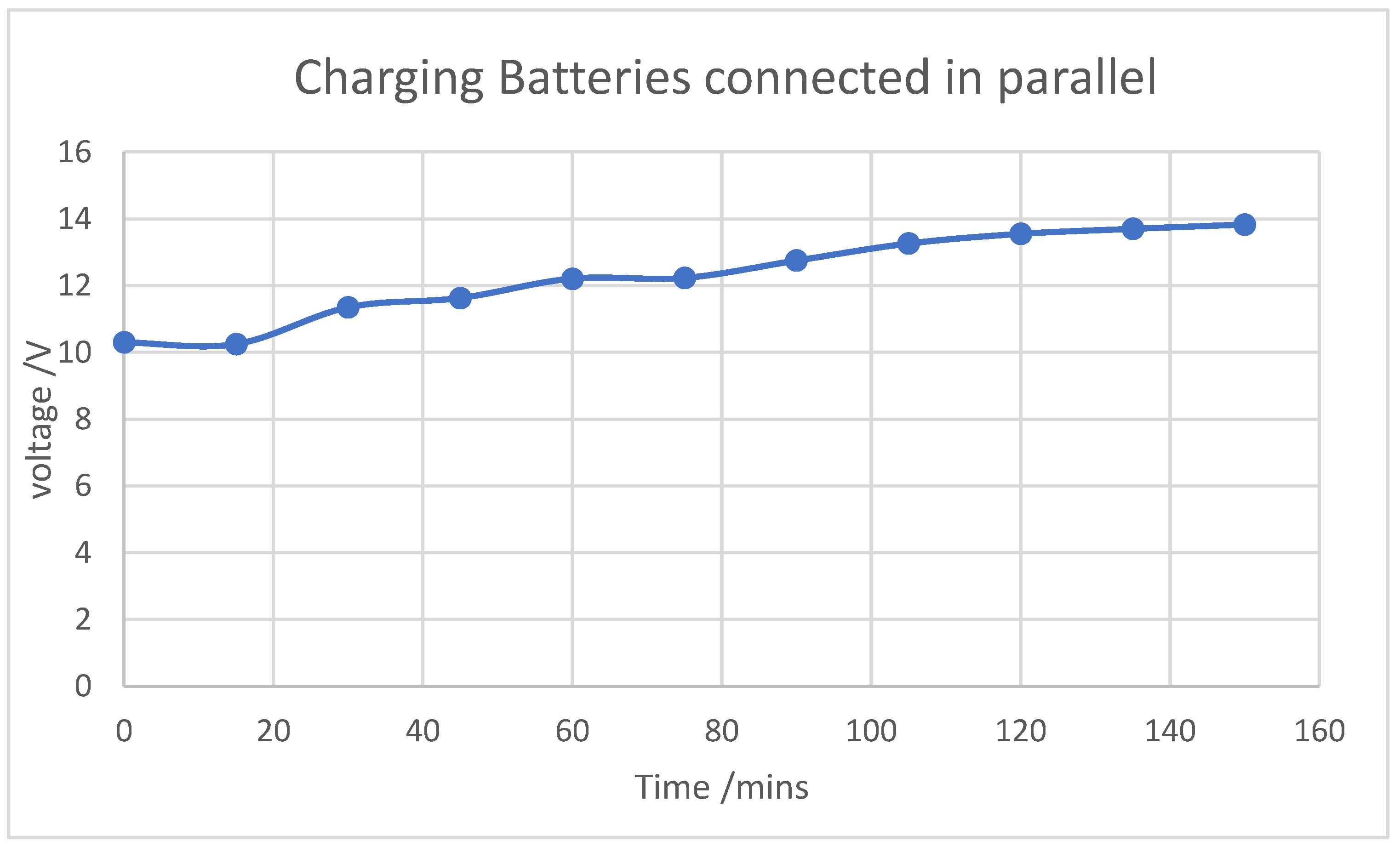

The widespread retirement of lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) emphasizes the urgent need to develop strategies for their safe and eco-friendly recycling. Recycling stands out as a promising method for maximizing the surplus value of retired LIBs while adhering to standards of reliability, efficiency, and sustainability. The primary objective of this research was to design a charging and discharging mechanism for used LIBs, assessing their viability for small-scale applications.

Through extensive characterization of the batteries, including analysis of their charging and discharging rates, we determined their potential for use as energy storage (backup) systems for such applications. The results revealed that the charging and discharging rates of the used batteries closely resembled those of a typical power bank, suggesting their suitability for backup energy storage.

However, when tested for small-scale applications, the system constructed from these batteries was unable to power devices like smartphones. This was due to the higher current output of the charging system, which exceeded the input current tolerance of smartphones. As a result, the smartphone’s surge protection mechanism intervened, cutting off power and preventing the devices from charging.

While the used LIBs showed potential as energy storage solutions for small-scale applications, further adjustments to the charging system would be necessary to ensure compatibility with sensitive devices like smartphones.

5.3. Discharge with NaCl

The use of sodium chloride (NaCl) as an electrolyte for discharging spent LIBs proved effective and practical. Experiments showed that batteries immersed in NaCl solutions discharged to voltages between 1.55 and 1.99V over two hours. The results confirmed that higher electrolyte concentrations accelerated the discharge rate, while extended discharge times mitigated voltage recovery, indicating a stronger discharge at consistent concentrations. However, minor rust formation on battery casings underscored the need for further evaluation to avoid long-term structural issues, despite the rust being superficial.

Incorporating safe discharge practices can significantly reduce environmental risks associated with LIB disposal. Sodium chloride solutions provide an accessible and secure method for de-energizing batteries, minimizing hazards during handling and transport. Public education campaigns on safe disposal methods and coordinated collection efforts can further reduce risks and enhance community safety. Future studies should include examining other electrolyte solutions, tracking side reactions, and testing multiple batteries to assess scalability and collective discharge behavior.