1. Introduction

Robotics in nursing is a relatively new development that emerged in the last decade, and coincides with the gradual rise of service robotics [

1,

2,

3]. Physical services rendered by commercial nursing robots found in hospitals can vary from transport, supplies fetching, patient lift and ambulation tasks [

4,

5,

6].

Patient fall prevention is an important public health issue. In 2024 medical costs for nonfatal fall injuries reached more than

$50 billion and fatal fall injuries exceeded

$754 million in the United States [

7]. Various strategies have been implemented to minimize the probability of inpatient falls during ambulation tasks, including patient fall risk assessments, nurse and patient education, and the use of different sensors [

8,

9,

10]. However, these strategies focus solely on precautionary measures, whereas robots offer a valuable technological alternative by offering walking assistance, avoiding obstacles, and enhancing user balance and stability [

4,

8,

11]. Using these devices reduces the need for human supervision, encourages user independence and safety, making them effective in mitigating the fall-related injuries. Thus, it is crucial to consider how healthcare professionals accept this new technology and what factors may affect this process. The assessment of acceptance of such robots by nurses, especially in fall prevention tasks, is still limited to a few pilot studies [

4,

5,

12] and more work in this area is needed.

Our Adaptive Robot Nursing Assistant (ARNA) robot was designed and built as a general-purpose nursing platform to handle physical tasks in hospital environments [

4,

5,

13]. One of the primary functions of ARNA is ambulation of the recovering patients with fall prevention capabilities that enhance the user’s safety [

13,

14]. In traditional transfer or ambulation tasks fall prevention devices such as gait belts are often used. To address this, ARNA employs full-body fall protection harnesses, which include straps secured across different body parts and connected to the robot. These safety features are further supported by a robust control system, known as model-free neuro-adaptive control (NAC), ensuring enhanced reliability and adaptability. A primary challenge in physical Human-Robot Interaction (pHRI) is developing adaptive control strategies that effectively respond to external forces while ensuring stability and performance. Conventional approaches like impedance control and admittance control have been commonly implemented to manage mechanical compliance and enhance user interaction. However, stability and performance in pHRI remain unresolved issues [

15,

16]. Novel control techniques, such as those based on neural networks, including PNNUI [

17], NAC [

18], and advanced methods like Model Predictive Control (MPC) [

19], offer potential improvements in robot adaptability. In recent years, NAC has been predominantly utilized as the controller for various of our robotic manipulators [

20], with enhancements like HIE-NAC [

21], which integrates human-intent modeling. In this study, we used the original NAC controller for the ARNA robot, aiming to achieve smooth, personalized, and responsive pHRI [

20]. Further details of this control method are comprehensively described in the Methods section.

The present study assesses the nursing students’ attitudes, such as perceived usefulness, perceived assistance, and perceived satisfaction associated with using the ARNA robot in walking tasks with fall prevention devices across three scenarios: a gait belt with human assistance, a gait belt with the robot, and a harness with the robot. The primary goal is to examine the efficacy of the ARNA robot for aiding nurses in ambulating patients in a simulated laboratory environment.

A commonly used framework for evaluating behavioral intention to use technology is primarily based on the TAM models developed by Davis. [

22,

23]. In these models, the perceived usefulness and ease of use psychological constructs were regarded as key explanatory variables. Later, the TAM models were modified to include more external variables (demographic, system characteristics and subjective norms) and constructs (satisfaction, enjoyment, performance) that had a moderating effect on the relationships among TAM variables [

24,

25,

26]. Several studies that use these models offer important additional insights for our current research. For example, differences in age have been found to influence abilities, attitudes, behaviors, and openness to adopt new technologies since older people have lower intention and are less willing to use it [

27,

28]. Gender has been suggested to play an important role in human–robot interaction due to a different perception of robots by males and females. It was found that men tend to view robots as more useful, show a greater intention to use them in the future, and are more willing to integrate them into their daily lives compared to women [

27]. Empirical evidence on differences in perceived usefulness of robots based on race is mixed. Although some studies found that non-whites and ethnic minorities tend to have lower usage of health-related technology compared to whites [

28], the results of the other studies suggest that it is cultural background that affects mostly attitudes and expectations for robots [

29,

30].

Structural equation modeling techniques or multiple regression methods are commonly used to obtain parameter estimates in the TAM framework [

4,

31]. In this study we propose a novel approach geared towards repeated measures experimental designs. It includes a hierarchical linear mixed-effects regression model, with two random effects terms to account for correlations within each subject and within each construct for a given subject [

32]. This approach allows for estimation of parameters by capturing the nested structure of the data and addressing potential intra-individual and intra-construct variability, thus enhancing the robustness of the analysis in small-sample experimental settings.

2. Methods

2.1. ARNA Robot Description

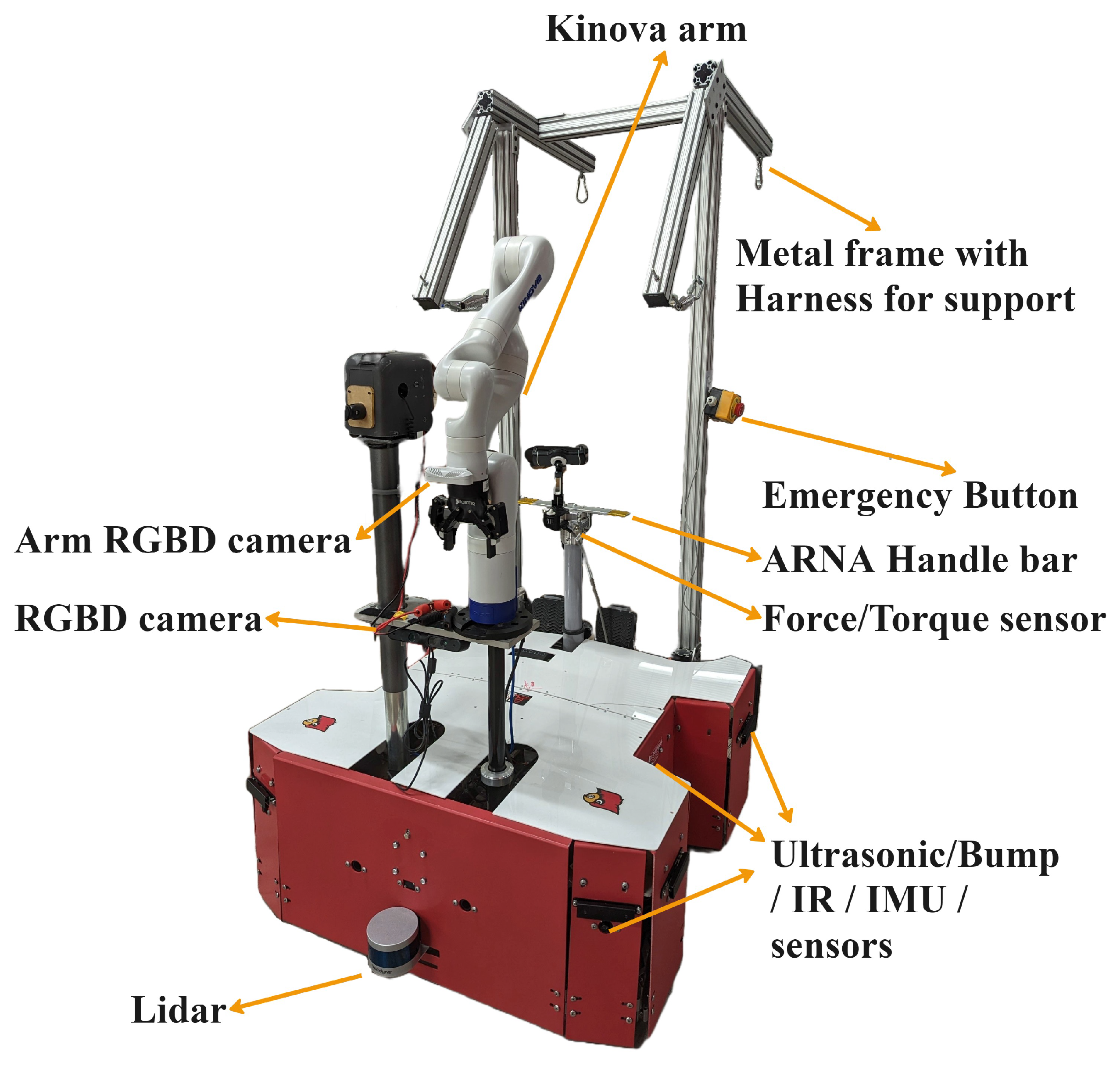

The ARNA robot was designed as a general-purpose robotic nursing assistant aimed at alleviating the physical demands on nurses by providing safe and effective support during patient ambulation tasks. Its primary objective is to assist nurses in hospital settings by safely supporting recovering or mobility-impaired patients during ambulation, thereby reducing the physical strain and risk of injury among healthcare providers. Target tasks specifically include patient walking assistance, fall prevention, and supportive interactions during transfers. The robot’s intended user population includes patients who require physical support during walking tasks and nursing personnel who is directly involved in patient ambulation and caregiving tasks.

2.1.1. Interfaces

To assist nurses and patients, ARNA can be operated in both physical and nonphysical modes. The nonphysical mode of interaction, also called Patient Sitter [

13], is carried out by remote telemanipulation using a joystick or a tablet. For the physical operation mode, a handlebar (Fig.

Figure 1) is fitted on the ARNA base to assist patients during ambulatory physiotherapy exercises, also called Patient Walker[

13]). The handlebar sits on a ATI Axia 80 multi-axis force-torque sensor, and the user can guide the robot in different directions by pushing, pulling, or twisting the handlebar. Hence, this interface acts as a support device for walking and, at the same time, collects interaction forces to power the robotic walker through an adaptive admittance controller.

2.1.2. Interfaces

To assist nurses and patients, ARNA can be operated in both physical and nonphysical modes. The nonphysical mode of interaction, also called Patient Sitter [

13], is carried out by remote telemanipulation using a joystick or a tablet. For the physical operation mode, a handlebar (Fig.

Figure 1) is fitted on the ARNA base to assist patients during ambulatory physiotherapy exercises, also called Patient Walker[

13]). The handlebar sits on a ATI Axia 80 multi-axis force-torque sensor, and the user can guide the robot in different directions by pushing, pulling, or twisting the handlebar. Hence, this interface acts as a support device for walking and, at the same time, collects interaction forces to power the robotic walker through an adaptive admittance controller.

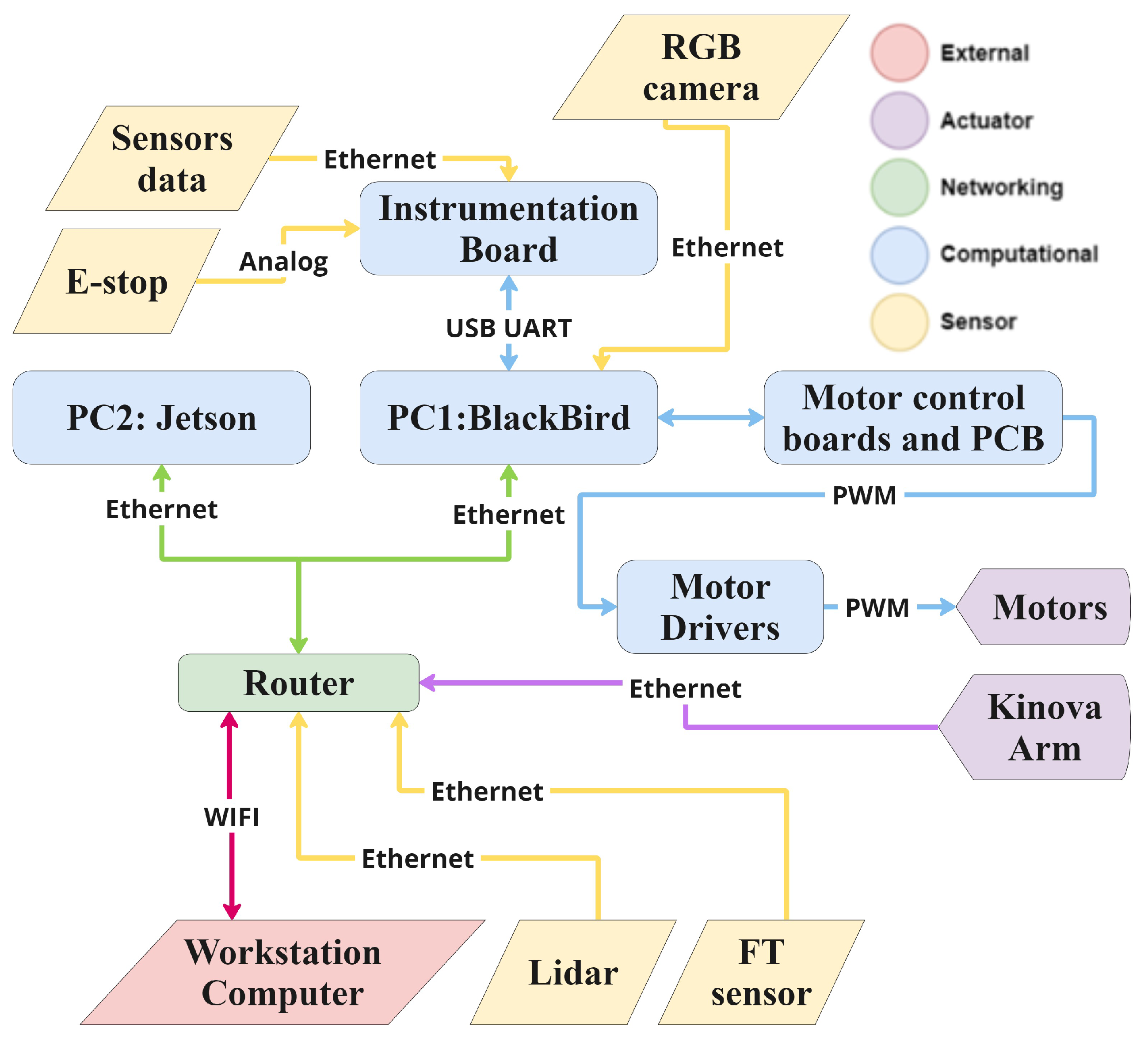

2.1.3. Electronics and Software

The ARNA robot integrates a network of sensors and processors for simultaneous localization and mapping (SLAM), navigation, and emergency stops (Fig.

Figure 2). Twelve sonar sensors are positioned around the base to detect obstacles, while six bump sensors provide emergency stop capability. When sensor readings exceed a defined threshold, an electronic relay disconnects the motor signals, causing an immediate halt. For SLAM and navigation, ARNA uses a Velodyne Puck LiDAR with four IMU transducers for sensor fusion. An ASUS Xtion camera aids in tasks involving the 7-DOF manipulator. ARNA’s data processing, SLAM, intent estimation, and navigation are managed by an Nvidia Jetson TX2 and VersaLogic EPU 4562 Blackbird, with a microcontroller handling data filtering. A Netgear Nighthawk AC1900 router supports networking, interfacing, and remote operation. ARNA operates within a Robot Operating System (ROS) C++/Python environment, enabling modular and open-source software development.

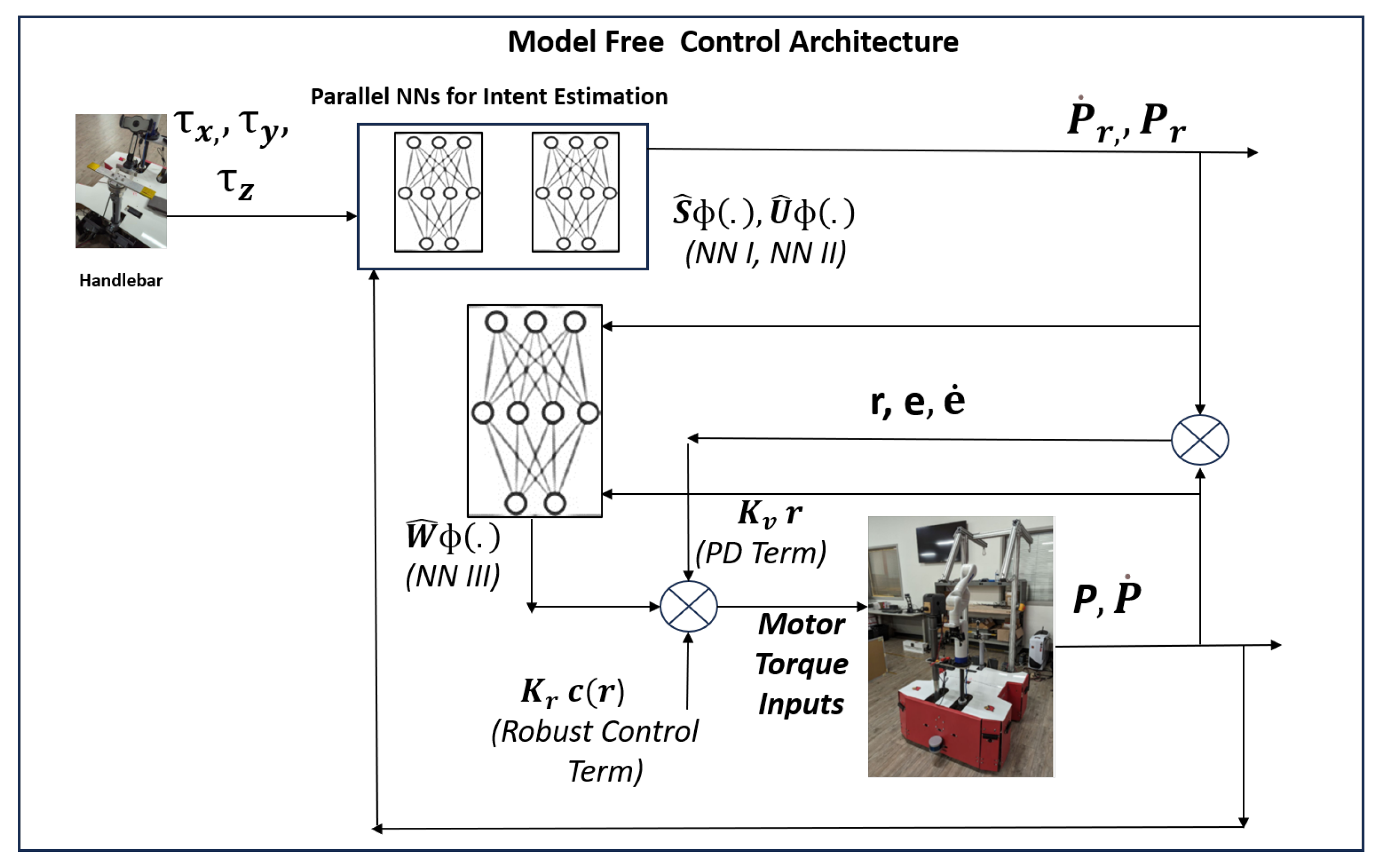

2.2. Model-Free Control Architecture

A model-free NAC controller was developed for ARNA to facilitate a smooth, personalized, and natural pHRI. Depending on the user and operating environment, this framework can adapt its control gains online. This ability to personalize and adapt is crucial, as nursing students, as observers, can witness seamless experiences and natural interactions between patients and robots.

The controller assumes that the user will try to guide the robot along a particular direction and continuously interact with the handlebar to maintain/correct the desired path. The outer intent estimation loop takes the force/torque measurements from the handlebar as its input to estimate the intended reference trajectory from the user (Fig.

Figure 3). These estimated/approximate reference commands are fed to the inner loop of the NAC, which generates the required wheel motor torques to fulfill the goal. The outer intent estimator loop is supported by two neural networks, where one of the neural networks estimates the human gains that vary from user to user. Whereas the other network exploits these gains to generate the approximate reference commands. The inner layer NAC approximates the ARNA robot’s motion dynamics using another neural network. The weights in the inner layer neural network are adapted to generate a suitable feedback linearizing control law, which enforces the tracking error to zero. A brief summary of the neural network-based model-free controller is presented here for completeness (see [

6,

20,

21] for more details).

The user operates the ARNA robot through the sensorized handlebar, which generates three torque outputs (

=

) corresponding to the interaction around the three axes. These torque signals are filtered for noise elimination and fed to outer intent estimation loop along with the current pose and velocity vector:

,

. Assuming the user wants to move ARNA to a desired pose

(unknown to the robot and controller), define a set of tracking error vectors as

and

to a reference robot position

. The outer intent estimation loop uses two neural networks (NN I, NN II) to approximate the human model and intended the desired trajectory, respectively, thereby completely circumventing the need to tune the controller for different users. These neural networks are defined as:

where

,

and

are estimated desired position, velocity and user-specific gains respectively. The variable

denotes the combination of interaction torques, desired position and velocity:

. The unknown weight matrices of the NN I and NN II are denoted by

and

, respectively. The symbol

describes the sigmoid activation function used to build neural networks. Define the estimated error and the discrepancy between the actual and estimated errors as:

where

is the error in weight estimation. The user specific filtered error dynamics is given by:

where

, ⊙ is the Hadamard product and

. Defining a sliding mode error variable

, the weight update laws for the two NNs are chosen as:

where

is design constant and

are design specific positive definite matrices. It can be proved that the weight update equations mentioned above make the estimated desired trajectory converge to actual user intended desired trajectory [

6,

20], and the error between them can be made smaller by tuning the design scalar

.

As the outer loop ensures the estimated desired trajectory vector converges to the true user intended trajectory (which is unknown), the inner NAC loop uses to compute the driving input torques for the motors actuating the wheels of ARNA. Hence, the objective of the NAC loop is to make sure that, a filtered error variable converges to as small value possible. Note that, this will lead to tracking error convergence as the filtered error defines a first order stable dynamics.

The motion dynamics of ARNA can be captured by a Euler-Lagrangian model expressed by:

where

,

represent the moment of inertia and Corriolis matrix respectively. The term

denotes the input torques to the motors,

is the torque due to external disturbances, and the function

represents the cumuative modelling uncertainty which has to approximated by a neural network, i.e.

where

,

and

are the weight matrix corresponding to the outer and hidden layer respectively. It was proved in [

6] that a control law of the form:

where

is the upper bound for weight matrices, assures the bounded tracking performance for ARNA robot. The term

points to the output of neural network whose weights are updated in the following way.

where

is a design constant and

are user defined positive definite matrices.

2.3. Participants

This study investigates the attitudes of nursing students toward the acceptance of ARNA for better user experience and corresponding implications for potential reduction of work-related injuries among healthcare professionals. Test users of the ARNA robot included fifty-eight pre-licensed nursing students (BSN and MEPN) recruited via emails and verbal communication from the School of Nursing, University of Louisville. Students were chosen due to their availability, willingness to participate in repeated sessions, and homogeneity in training background, which allowed us to control for variability in prior clinical experience. This population also represents a critical target group for early-stage testing, where the ARNA robot can be meaningfully assessed before testing in more complex real-world scenarios. Participation of all subjects was both voluntary and confidential. Students received compensation in the form of three hours of clinical credit. The inclusion criteria required that participants were from the School of Nursing and self-reported being physically and psychologically fit to participate in simulated clinical interactions. The exclusion criteria included any self-reported physical limitations that prevented participants from completing the tasks, as well as any self-reported intellectual, cognitive, or developmental disorders that could interfere with task performance. Participants with prior experience using robots in clinical settings were excluded to avoid bias due to familiarity with robotic systems.

An external participant, who was not a nursing student, assumed the role of the simulated patient throughout the experiment. Specifically, the simulated patient was trained prior to data collection to ensure a consistent interaction style with ARNA across all trials. While we acknowledge that experience over time can influence the results of the experiment, that set up was proposed to minimize variability on the patients’ level, since the focus of the study was on the ability to detect effort-related signals from the future nurse practitioners, rather than the simulated patient’s behavior per se.

The University of Louisville Institutional Review Board granted approval to conduct the experiments under IRB no.18.0659. We acknowledge that a portion of the sample data was previously used in an earlier publication [

4].

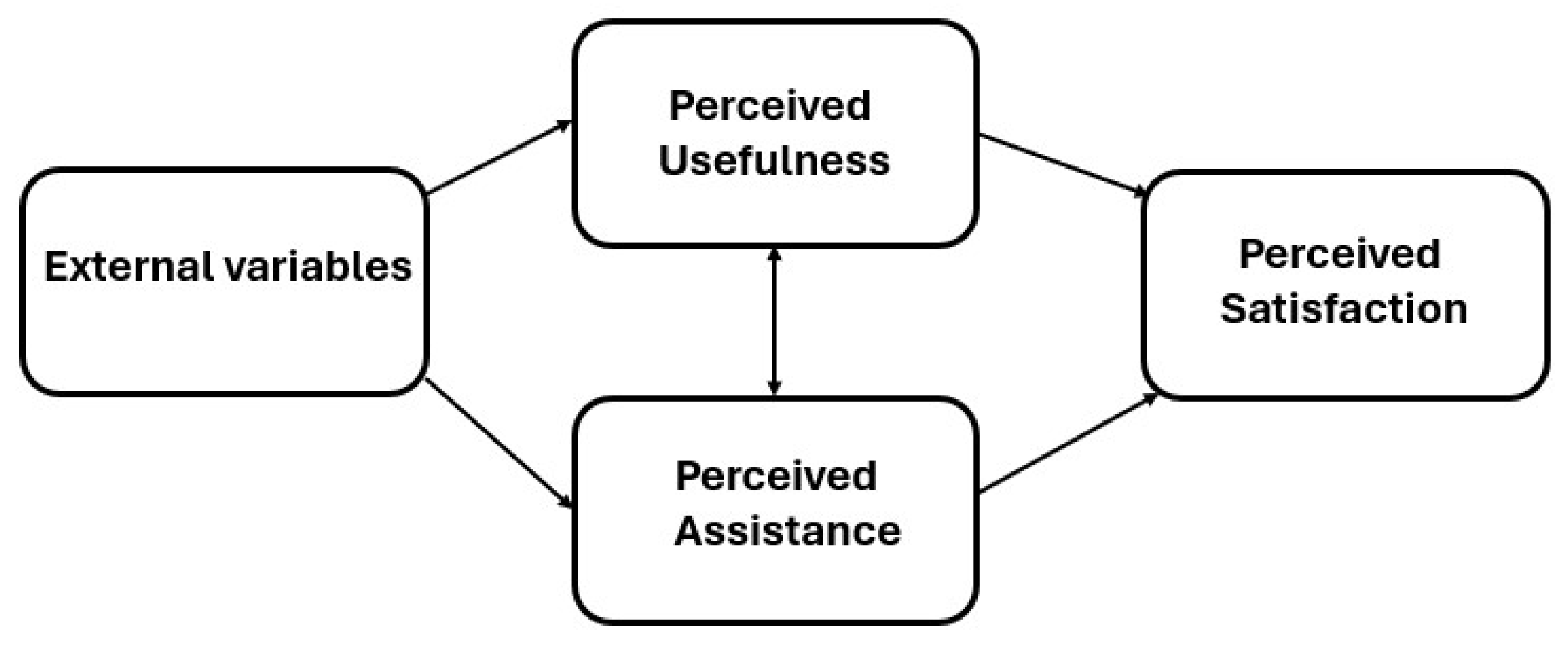

2.4. TAM model hypothesis

In standard Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) framework the two primary variables of perceived usefulness (PU) and perceived ease of use (PEOU) have a mediating role in the inter-relationships between system characteristics (external variables) and the behavioral intentions and eventual usage of the technology [

23,

33]. However, since our nursing student subjects only assisted the simulated patient in walking tasks (hold the belt or harness back strap firmly from the back of the patient) and do not directly control the robot for safty reasons. We substituted PEOU construct with perceived assistance (PA) that refers to how much support and help users believe the technology provides. In other words, we wanted to measure the extent to which participants viewed ARNA as being assistive [

34], consistent with the intelligent systems application of the technology acceptance model [

35]. While PA is not traditionally a standalone variable in classic TAM models, studies show that users are more likely to adopt technology that provides clear assistance aligned with their needs and values, as this perception supports both usefulness and ease of use [

11,

12,

36]. Furthermore, since the subjects under the study were not yet nurse professionals who could provide data on the actual intention to use the technology the behavioral intention construct of the TAM model was substituted by the perceived satisfaction (PS) as a proxy objective measure, an approach consistent with that used in similar studies [

37,

38,

39,

40].

Figure 4 illustrates the proposed TAM relationship framework, with perceived satisfaction (PS) as the response variable influenced by external factors: perceived usefulness (PU), perceived assistance (PA), tasks, and demographics.

During our study, we tested the following hypothesis:

Perceived Usefulness impacts Perceived Satisfaction, as users who find the system useful tend to be more satisfied with it.

Perceived Assistance impacts Perceived Satisfaction by enhancing the user experience that supports task accomplishment.

Perceived Usefulness and Perceived Assistance are significantly higher while using robot in ambulation tasks compared to manual controls

We also tested whether demographic factors such as age, race or gender have significant effects on Perceived Usefulness and Perceived Assistance in this study.

2.5. Intervention

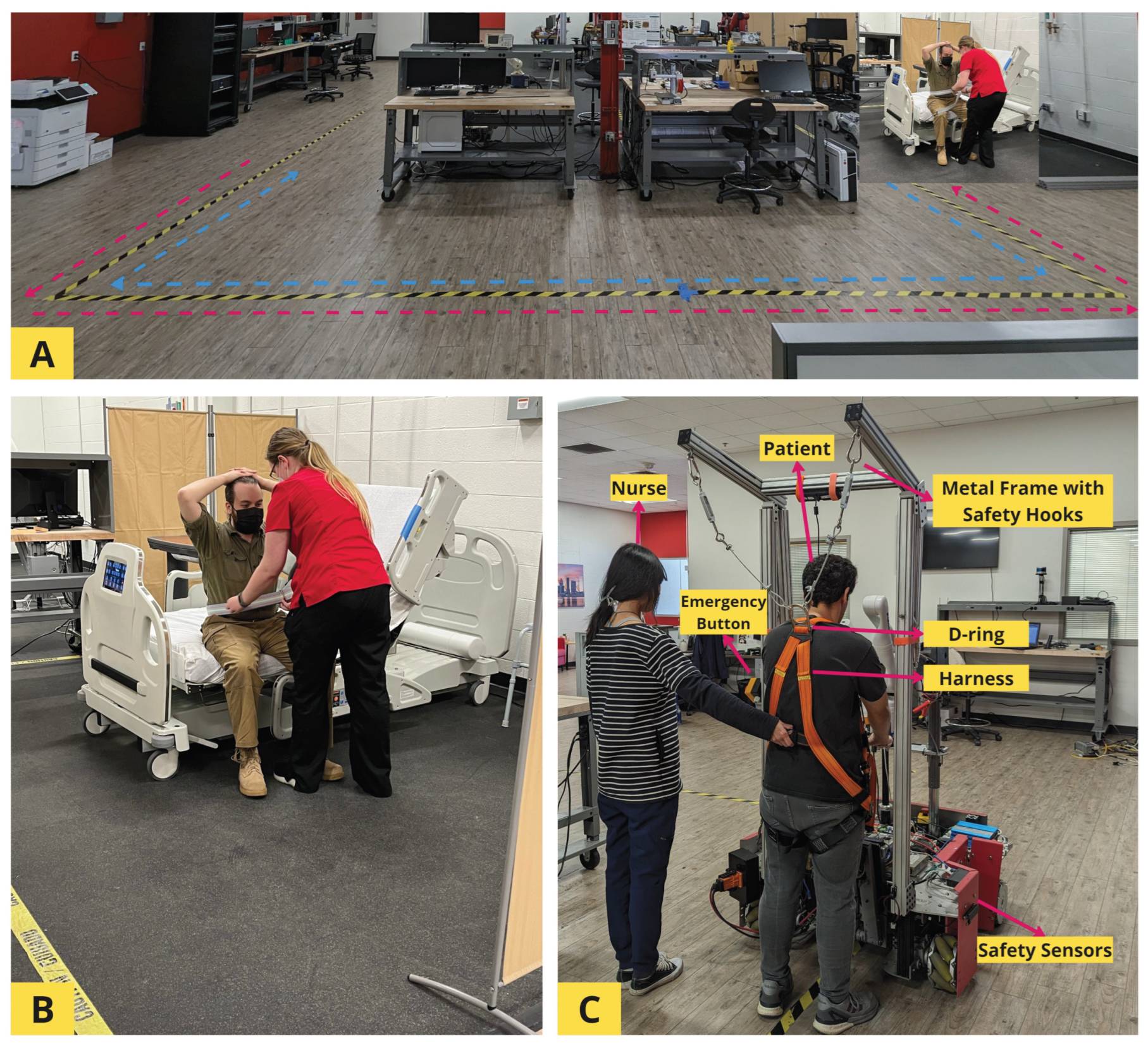

Three intervention scenarios were used by the participants to assist walking a simulated patient with fall prevention devices that included: "Gait Belt+Human" (gait belt with human assistance only, no robot), "GB+ARNA" (gait belt with the ARNA robot), and "Harness+ARNA" (a full-body fall protection harness connected to ARNA robot). As shown in the

Figure 5 part A), the interventions took place in LARRI’s lab with a simulated hospital room and a clearly marked path that resembled a 46.5-foot-long hospital corridor with one right hand side turn (placed 15 foot away from the starting point).

Figure 5 part B) dipicts the process of putting a gait belt on a simulated patient.

Figure 5 part C) demonstrates the ambulation task with a harness and a robot.

2.6. Instruments and Variables

The variable perceived usefulness (PU) (4 items measured on a Likert-type scale (range, 1–5)) evaluated in the study was determined based on the core constructs of the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) [

22,

23]. The perceived usefulness measure was taken directly from the TAM questionnaire [

23] but changing the referent of the technology to ARNA. Additional subjective measures such as perceived assistance (PA) (4 items measured on a Likert-type scale (range, 1–5)) and perceived satisfaction (PS) (5 items measured on a Likert-type scale (range, 1–5)) were constructed based on best practices for corresponding measures of perceived assitance [

34,

35] and perceived satisfaction [

38,

39,

40] by changing the referent for those items to ARNA. The type of tasks and demographics were included based on proposed experimental design.

A detailed per item data dictionary for each construct is provided in the appendix in a

Table A1. Other independent variables included a dummy-coded experimental task variable (Task 1: "GB+Human", Task 2: "GB+ARNA", Task 3: "Harness+ARNA" with a reference: Task 1), Gender (reference: “female”), Race (reference: “White”) and Age.

2.7. Study Design

The study employed a block randomized "Latin square" experimental design with three different tasks for each participant. In that type of design each task appears exactly once in each row and column to control for order and carry-over effects. The first block started with a "Gait Belt+Human" task, the second with a "GB+ARNA" task and the third one with a "Harness+ARNA" task. Since each block of participants was recruited within a restricted time frame, we obtained unequal sample sizes in three blocks. There were 14 subjects randomized to the first block, 28 subjects to the second, and 16 to the third. Nevertheless, a linear mixed-effects modeling technique to obtain parameter estimates handles asymmetrical or unbalanced sample sizes effectively [

41].

2.8. Data Collection Procedure

During the experimental session, each participant was introduced to the ARNA robot and provided a short description of its capabilities in a walking task. In all three scenarios the participant only ambulated the simulated patient who actually walked with a robot holding its handlebars, tugging it to move forward, backward, sideways, or turn. We provided no direct training for a robot operation, except on how to stop it using an emergency button. The robot was also armed with safety sensors to avoid unexpected collisions with the environment.

In all scenarios the simulated patient was seated on a bed and the ARNA robot was stationed at the room’s entrance. The participant, following scripted study procedures, entered the room and applied the test devices, such as a walking belt (gait belt) or a full-body fall protection harness to the simulated patient while standing beside them. The gait belt was fastened at the simulated patient’s waist. The harness was snugly fit over the hips and waist of the patient, attached to two hooks on the robot’s frame and secured by a ring located in the middle of the back and between the patient’s shoulder blades. Next, the simulated patient and a robot walked from and to the hospital bed along a predefined path while the participant held either the gait belt or a waist band of the harness behind the simulated patient.

The duration of the walking portion of the experiment in each task lasted 5-10 minutes, based on whether a robot was used (10 minutes) or not (5 minutes). The experiment was conducted under the same conditions for all participants. Following each of these three tasks, the participants were asked to evaluate their experience of performing tasks and mark the responses in a questionnaire administered via iPad using the Qualtrics. Data from the Qualtrics questionnaire were stored in an online secure Qualtrics cloud and only approved research personnel had access to those data.

The questionnaire was adapted from the original TAM paper [

22] as well as its extentions and usability studies [

5,

13,

14,

42]. The questionnaire’s content validity was established by the paper’s co-authors, who are faculty members with expertise in assistive technologies in robotics, nursing education, and psychology. They provided a multidisciplinary perspective relevant to the development and evaluation of the ARNA robot. This approach aligns with commonly accepted practices in content validation literature, where a panel of five to ten subject matter experts is considered sufficient for ensuring content validity [

43,

44]. For internal consistency, Cronbach’s

for all constructs across each task was calculated.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses with downloaded in CSV format files were performed using R version 4.4.1 software. After the quality checks, de-identification and data cleaning were performed, the Cronbach’s and descriptive statistics were calculated using R built-in libraries (ltm, tidyverse).

An integrated hierarchical linear mixed effect regression model was used to analyze the relationship between the perceived satisfaction as a response variable and other external variables. There were two types of random intercepts introduced: (i) within each subjects and (ii) within each construct for a particular subject to account for the correlation between observations. This type of modeling technique explicitly accounts for the within-subject correlation by including not only fixed but also random effects, borrowing strength across repeated observations and accounting for variability more precisely. It was demonstrated that such models provide greater power to detect true effects making them more robust and generalizable [

32,

45].

The parameter estimates for the model were obtained by using the Wald t-tests with the Satterthwaite approximation for degrees of freedom. The most parsimonious model was chosen based on a likelihood ratio test using a chi-square test statistics. The usual assumptions of normality, homoscedasticity and independence of the residuals and normality of random effects were tested after the model fitting using R built-in libraries.

3. Results

3.1. Reliability of TAM Model Questionnaire

The adapted TAM questionnaire consists of 13 items that include PU, PA and PS domains. The generally accepted thresholds for Cronbach’s alpha between 0.70 and 0.80 are considered acceptable, while a value above 0.80 is regarded as good [

46]. The Cronbach’s

for TAM constructs scores across each task were calculated and provided in the

Table 1. The results indicate acceptable reliabilities.

3.2. Characteristics of Subjects and Variables

There were 58 nursing students included in the analysis.

Table 2 presents a summary of the descriptive statistics for the subjects’ demographic characteristics and other variables. There were 14 subjects assigned to the first sequence, 28 subjects to the second, and 16 to the third. The mean age of was 22.57 (SD= 3.74). Most of the subjects were females (91.38%, n=53). Those identified as Whites constituted more than half of the sample (58.62%, n=34). The second largest race group in the sample was represented by Blacks and African Americans (24.14%, n=14) and followed by Asians (17.24%, n=10).

The comparison of means of TAM constructs scores across all tasks demonstrate that participants regarded the tasks with ARNA robot, on average, more useful and with higher assistance level than with only a human holding a gait belt. The mean scores of perceived satisfaction for both tasks including the robot were also higher than without the robot. Formal tests of differences in means between tasks in a repeated measures experiment design with and without ARNA robot is provided in the next section.

3.3. Hierarchical mixed effect model

Let , and represent the mean scores across corresponding survey items for perceived usefulness, perceived assistance and perceived satisfaction, respectively, for the individual in the repeated measurement. We let be the indicator variables corresponding to task of individual for repeated measurement. Consider equal to 1 if the individual i in the repeated measurement performs the task . It is set to 0 otherwise. Let label corresponding construct such as "PU", "PA","PS". For the race dummy variable let equal to 1 if ("Asian", "Black/African American") and 0 otherwise. And for a gender dummy variable if male and 0 otherwise.

Based on these notations we present the following hierarchical model that analyzes those constructs, tasks and other external variables and their interrelationships in an integrated manner:

for

. And

where

and

are corresponding random effects for

individual and for the construct within the same individual and

is the random noise uncorrelated with any fixed or random effects for

. The nested structure of the random effects implies two levels of covariances:

(the covariance withing measurements of the same construct for the same individual) and

(the weaker covariance between measurements of different constructs within the same individual). As per these notations,

and

represent the differences in the effect of tasks 2 and 3 from the baseline task 1 for a specific construct

c. These parameter effects in the Equation (

11) correspond to the first two arrows from external variables to perceived usefulness and perceived assistance in Fig.

Figure 4. Similarly, the effects of the perceived usefulness and perceived assistance constructs on perceived satisfaction are given by

and

coefficients. These relationships are represented by arrows directed toward the perceived satisfaction node.

The relationship between PU and PA shown in the TAM diagram with an arrow connecting two boxes is not explicitly specified in the equations since it is automatically implied by the structure of our model. First, the model allows both the constructs to be simultaneously affected by the task settings. This itself induces marginal correlations between observed values of these contrasts. Furthermore, the measurements of these constructs within a subject results in a within-subject association. The latter is accounted for by random effects introduced in the model.

The results of the estimation of the reduced models in the form of (11) but with only one random effect term across individuals for

are provided in the appendix in

Table A2 and

Table A2. They suggest that the participants rate robot’s performance in terms of perceived usefulness and perceived assistance in ambulation tasks higher than with the human and a gait belt along since all coefficients for robot tasks are positive and highly significant. It was found that variables such as race or age do not have any effect on PU or PA. The gender (male) had a positive significant effect on PU (

).

Table 3 summarizes the results of the estimation of the model (12) with only one demographic variable, gender (age and race were excluded from the analysis due to insignificance). It can be seen that the effects of PU and PA on PS are positive and highly significant (

,

, and

,

). The estimates of the interaction terms of PU and PA with all tasks for the ARNA robot are positive and highly significant with all

. The gender variable becomes insignificant (

). The total model’s explanatory power was substantial with

= 0.93. The high ICC=0.89 indicates the appropriateness of the inclusion of random effects. Thus, both intervention scenarios that employed ARNA robot were seen as more useful, providing higher assistance levels in ambulation tasks in contrast to the non-robot scenario.

4. Discussion

The present study examines the use of robotic assistant ARNA in patient’s ambulation tasks. As it was previously shown, the integration of robots into direct nursing care may not only provide a possible solution to mitigate the physical demands of the healthcare workers but also reduce risks of work-related injuries [

4,

13,

47,

48]. The present study further highlights ARNA’s capabilities and model-free control architecture (NAC), demonstrating its potential as a robotic assistant. Observations by nursing student participants revealed seamless and natural interactions between humans and the robot, underscoring ARNA’s effectiveness in supporting ambulation tasks.

We hypothesized that ARNA robot is perceived more useful and has a higher level of assistance by nursing students in a simulated patient’s walking task with either gait belt or harness attached to the robot than with a human and a gait belt alone. The perceived ease of use construct in this study was substituted by perceived assistance, since the nursing students did not directly control the robot. Furthermore, the hypothesis whether the perceived usefulness and perceived assistance while using robot leads to a higher level of perceived satisfaction also was tested. The hypothesis testing was conducted via an extended TAM framework [

24,

33] that included external variables (tasks, age, gender and race). A hierarchical linear mixed effects regression model with two random effects that captured the correlations within each subject as well as within each construct for a particular subject was used to produce parameter estimates. The above findings also demonstrate that, in addition to traditional SEM models, that require a large number of observations [

49], or multivariate regression models, that can not be used in a repeated measures experimental designs, our approach could be easily implemented to evaluate the corresponding inter-relationships between contracts and external variables [

32,

50].

Our hypothesis that higher levels of perceived satisfaction would be reported when performing ambulation tasks with a robot compared to with a human was fully supported, particularly in terms of perceived usefulness and assistance. The simultaneous estimation of those effects confirmed the previous findings on the importance of these constructs in the technology adoptation process [

4,

11,

13,

31]. Additionally, none of the demographic variables—such as race, or age—were found to significantly affect the self-reported constructs mean scores. Although our reduced model indicated that male participants perceived the robot as more useful than female participants, a finding consistent with previous research based on gender roles and stereotypes theories [

51,

52], the limited gender variability in our sample (53 females vs. 5 males) constrained the statistical power of this result in the integrated model, rendering the effect non-significant. This imbalance limits the ability to draw firm conclusions about gender-based differences. Thus, it is essential for future research to purposefully explore these psychological constructs across more balanced and diverse samples.

The current study highlights some common limitations and important directions for future research. The first limitation is the current ARNA robot’s size, which is too large for use in tight spaces. While the harness and frame offer protection during potential falls, implementing an immediate automatic stop mechanism is still necessary for an effective fall response. To address this, we recently designed a new handlebar equipped with pressure sensors to detect hand presence and grip force. This enables the robot to halt immediately during a fall, enhancing patient safety during ambulation tasks.

Next, the use of a single simulated patient and a sample of nursing students may limit the study’s generalization to broader clinical settings, where various healthcare professionals work with diverse patient populations. Future research should include patients with different profiles to enhance the generalization of the findings and evaluate potential effects related to user experience. Nursing students may not accurately reflect the perspectives, clinical decision-making, and judgment of experienced nursing professionals, primarily due to their limited exposure to real-world healthcare settings, especially in matters related to patient safety. As a result, in our experiments, the perceived level of satisfaction was used only as a proxy for actual intent to use the robot. Further research is needed in this area to evaluate true perception of the technology by both patients and practicing nurse professionals across various clinical roles to validate the acceptance of ARNA robot in more complex and dynamic care environments.

At this stage of the research, the study was exploratory in nature, aiming to assess system feasibility and gather preliminary data on user interaction and physiological responses. As such, a formal sample size calculation was not performed, and an ideal number of participants could not be predetermined due to the novelty of the setup. However, the chosen sample size was consistent with similar pilot studies in the field [

4,

13] and was sufficient to identify practical challenges and inform future findings. Generally, as it was demonstrated before in similar studies, a larger sample size with fifty one participants per group in repeated measures experimental designs to detect effect sizes of 0.4 or greater may enhance statistical power and improve the reliability and robustness of the findings [

53].

While the study did not find significant effects for race and age, we acknowledge that these and other contextual factors (for example, technology anxiety, work experience or other subjective norms [

31,

54]) may still warrant further exploration through other instruments such as focus groups, interviews or open-ended survey questions to enrich the understanding of participants’ attitudes and perceptions, particularly regarding the robotic assistants.

5. Conclusions

This study explored nursing students’ attitudes (perceived usefulness, perceived assistance and perceived satisfaction) toward accepting the ARNA robot while performing walking tasks with fall prevention devices (gait belt and a full-body protection harness). The overall findings show that participants perceive walking tasks with the robot as more useful, offering a higher level of assistance compared to those performed with a human alone. This, in turn, resulted in a greater level of satisfaction from using the technology. These results support previous findings on attitudes and factors that affect user’s acceptance of new technology [

4,

11,

13]. They can provide a basis for ongoing discussions regarding the acceptance of service robots by medical personnel engaged in daily caregiving tasks [

36,

47].

The effects of demographic variables (sex, race, and age) on perceived satisfaction and assistance were found to be non-significant, likely due to limited variability in these characteristics within the sample and the relatively small overall sample size in our experiment that aimed to evaluate the impact of such variables on psychological constructs [

55,

56]. However, we demonstrated that men perceived the ARNA robot in ambulation tasks as more useful than women. This effect may be explained by the tendency to view robots as tools for tasks traditionally linked to masculine roles, which can enhance perceptions of its usefulness by males [

57,

58]. But again, due to a low variability in the sample this finding may also be attributed to a measurement bias along.

To analyze survey-based quantitative data, we used an extended TAM model with external variables, substituting a standard perceived ease of use construct on perceived assistance within the proposed relationship framework [

31,

36]. The use of the perceived assistance construct relates to how much help the robot provides in a specific context, for example, in any ambulation, lifting, or guidance tasks. And that perception of usefulness and assistance, as shown in previous studies [

11,

12,

36], may in turn influence perceived satisfaction which can serve as a proxy for the behavioral intention to adopt the new technology. This framework can be applied to similar contexts involving other assistive robots designed for specific functions. The hierarchical mixed effect model with two random terms was used to obtain the parameter estimates.This modeling approach enabled the analysis of interrelationships among TAM model variables in an integrated way, while also accommodating a relatively small sample size, controlling for individual differences, and facilitating efficient within-subject comparisons across different conditions.

We believe our work can contribute to a better understanding of the factors that affect the acceptance of new technology, ultimately supporting the creation of a healthier, safer, and less burdensome work environment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.P. and C.L.; methodology, I.K., P.S., R.M., J.G., D.P. and B.E.; software, I.K.,P.S. and M.R.; validation, I.K., P.S., M.L.,B.E., M.E., E.Y.; formal analysis, I.K., P.S., R.M., D.P. and J.G.; investigation, I.K., P.S., R.M., M.R., J.G. and D.P.; resources, D.P., B.E. and C.L.; data collection, I.K., P.S. and N.Z; writing—original draft preparation, I.K., R.M., P.S., J.G., B.E. and M.R.; writing—review and editing, I.K., P.S., J.G., R.M., B.E. and D.P.; visualization, I.K. and P.S.; supervision, R.M., J.G., M.L., and D.P.; project administration, D.P., B.E. and M.L.; funding acquisition, D.P., B.E., and M.L.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Science Foundation grant FW-HTF-2026584.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of University of Louisville, KY, USA (protocol code 18.0659 and date of approval 08.06.2018).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are not openly available due to reasons of sensitivity and are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Data are located in controlled access data storage at Louisville Automation and Robotics Research Institute (LARRI), University of Louisville.

Acknowledgments

We are deeply saddened to report that our co-author, Dr. Mitra passed away during the preparation of this manuscript. We honor his contributions to this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ARNA |

Adaptive Robot Nursing Assistant |

| TAM |

Technology Acceptance Model |

| NAC |

Neuro-Adaptive Control |

| pHRI |

Physical Human-Robot

Interaction |

| MPC |

Model Predictive Control |

| HIE |

Human-Intent Estimator |

| PNNUI |

Parallel Neural Network User Interface |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Based on a Likert-scale applied to each set of questionnaires below, please respond (mark) on how strong you agree or disagree with the statements about ARNA/GaitBelt using five-point scale in the following anchors: (1) Strongly disagree, (2) Disagree, (3) Neutral, (4) Agree, (5) Strongly Agree.

Table A1.

Itemized questionnaire

Table A1.

Itemized questionnaire

| Construct |

Item Statement |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

| Perceived Usefulness (PU) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| PU1 |

ARNA/GaitBelt enables nurses to complete patient care more quickly |

|

|

|

|

|

| PU2 |

ARNA/GaitBelt improves patient care and management |

|

|

|

|

|

| PU3 |

ARNA/GaitBelt increases nurses’ productivity in patient care |

|

|

|

|

|

| PU4 |

ARNA/GaitBelt makes nurses’ patient care and management easier |

|

|

|

|

|

| Perceived Assistance (PA) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| PA1 |

ARNA/GaitBelt could provide accurate assistant service |

|

|

|

|

|

| PA2 |

ARNA/GaitBelt provides reliable assistant service |

|

|

|

|

|

| PA3 |

ARNA/GaitBelt provides safe assistant services |

|

|

|

|

|

| PA4 |

ARNA/GaitBelt provides convenient assistant services |

|

|

|

|

|

| Perceived Satisfaction (PS) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| PS1 |

I am completely satisfied with using ARNA/GaitBelt in patient care |

|

|

|

|

|

| PS2 |

I feel very confident in using ARNA/GaitBelt in patient care |

|

|

|

|

|

| PS3 |

I found it easy to use ARNA/GaitBelt in patient care |

|

|

|

|

|

| PS4 |

I can accomplish tasks quickly using ARNA/GaitBelt |

|

|

|

|

|

| PS5 |

I believe that using ARNA/GaitBelt in patient care will increase the quality of nursing tasks |

|

|

|

|

|

Appendix A.2

Table A2.

Effects of tasks and demographic variables on Perceived Usefulness (PU)

Table A2.

Effects of tasks and demographic variables on Perceived Usefulness (PU)

| Perceived Usefulness |

|---|

| Predictors |

Estimates |

CI |

p-value

|

| Task 2 |

0.56 *** |

0.31–0.80 |

|

| Task 3 |

0.67 *** |

0.42–0.92 |

|

| Gender (Male) |

0.57 * |

0.03–1.11 |

|

| Race (Black) |

-0.00 |

-0.37–0.37 |

0.996 |

| Race (Asian) |

-0.02 |

-0.40–0.43 |

0.934 |

| Age |

0.0047 |

-0.04–0.05 |

0.826 |

| Random Effects |

|

0.46 |

|

|

|

0.17 |

|

|

| ICC |

0.28 |

|

|

|

58 |

|

|

| Marginal / Conditional

|

0.151 / 0.385 |

Appendix A.3

Table A3.

Effects of tasks and demographic variables on Perceived Assistance (PA)

Table A3.

Effects of tasks and demographic variables on Perceived Assistance (PA)

| Perceived Assistance |

|---|

| Predictors |

Estimates |

CI |

p-value

|

| Task 2 |

0.39 *** |

0.18–0.60 |

|

| Task 3 |

0.50 *** |

0.30–0.71 |

|

| Gender (Male) |

-0.17 |

-0.63–0.28 |

0.456 |

| Race (Black) |

0.01 |

-0.31–0.33 |

0.936 |

| Race (Asian) |

0.05 |

-0.30–0.41 |

0.765 |

| Age |

0.00 |

-0.03–0.04 |

0.841 |

| Random Effects |

|

0.32 |

|

|

|

0.13 |

|

|

| ICC |

0.29 |

|

|

|

58 |

|

|

| Marginal / Conditional

|

0.101 / 0.361 |

References

- Zhang, S.; Liu, L.; Peng, T.; Ding, S. Patterns and Trends in Global Nursing Robotics Research: A Bibliometric Study. Journal of Nursing Management 2025, 2025, 7853870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalo de Diego, B.; González Aguña, A.; Fernández Batalla, M.; Herrero Jaén, S.; Sierra Ortega, A.; Barchino Plata, R.; Jiménez Rodríguez, M.L.; Santamaría García, J.M. Competencies in the Robotics of Care for Nursing Robotics: A Scoping Review. In Proceedings of the Healthcare. MDPI, Vol. 12; 2024; p. 617. [Google Scholar]

- Soriano, G.P.; Yasuhara, Y.; Ito, H.; Matsumoto, K.; Osaka, K.; Kai, Y.; Locsin, R.; Schoenhofer, S.; Tanioka, T. Robots and robotics in nursing. In Proceedings of the Healthcare. MDPI, Vol. 10; 2022; p. 1571. [Google Scholar]

- Logsdon, M.C.; Kondaurova, I.; Zhang, N.; Das, S.; Edwards, B.D.; Mitchell, H.; Nasroui, O.; Erdmann, M.; Yu, H.; Alqatamin, M.; et al. Perceived Usefulness of Robotic Technology for Patient Fall Prevention. Workplace Health & Safety.

- Das, S.K.; Saadatzi, M.N.; Wijayasinghe, I.B.; Abubakar, S.O.; Robinson, C.K.; Popa, D.O. Adaptive robotic nursing assistant, 2022. US Patent App. 17/604, 035.

- Das, S.K. Adaptive physical human-robot interaction (PHRI) with a robotic nursing assistant. Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 3268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, A. Elderly fall statistics, 2024. Accessed on , 2025. 06 January.

- Sam, R.Y.; Lau, Y.F.P.; Lau, Y.; Lau, S.T. Types, functions and mechanisms of robot-assisted intervention for fall prevention: A systematic scoping review. Archives of gerontology and geriatrics 2023, 115, 105117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callis, N. Falls prevention: Identification of predictive fall risk factors. Applied nursing research 2016, 29, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heng, H.; Jazayeri, D.; Shaw, L.; Kiegaldie, D.; Hill, A.M.; Morris, M.E. Hospital falls prevention with patient education: a scoping review. BMC geriatrics 2020, 20, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadatzi, M.N.; et al. Acceptability of Using a Robotic Nursing Assistant in Health Care Environments: Experimental Pilot Study. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2020, 22, e17509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, C.; Yuan, R.; Mao, B.; Liu, Q.; Wang, W.; He, Y. Technology Acceptance of Socially Assistive Robots Among Older Adults and the Factors Influencing It: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Applied Gerontology 2024, 43, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abubakar, S.; Das, S.K.; Robinson, C.; Saadatzi, M.N.; Logsdon, M.C.; Mitchell, H.; Chlebowy, D.; Popa, D.O. Arna, a service robot for nursing assistance: System overview and user acceptability. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 16th International Conference on Automation Science and Engineering (CASE). IEEE; 2020; pp. 1408–1414. [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg, C.L.; Sevil, H.E.; Behan, D.; Popa, D.O. Robotic Nursing Assistant Applications and Human Subject Tests through Patient Sitter and Patient Walker Tasks. Robotics 2022, 11, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Xue, C.; Yu, X.; Li, Z.; Yang, C. Admittance-Based Controller Design for Physical Human–Robot Interaction in the Constrained Task Space. IEEE Transactions on Automation Science and Engineering 2020, 17, 1937–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Zhang, C.; Si, W.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, C.; Zeng, C. A Physical Human–Robot Interaction Framework for Trajectory Adaptation Based on Human Motion Prediction and Adaptive Impedance Control. IEEE Transactions on Automation Science and Engineering 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SharafianArdakani, P.; Hanafy, M.A.; Kondaurova, I.; Ashary, A.; Rayguru, M.M.; Popa, D.O. Adaptive User Interface With Parallel Neural Networks for Robot Teleoperation. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2025, 10, 963–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hejrati, M.; Mattila, J. Physical Human–Robot Interaction Control of an Upper Limb Exoskeleton With a Decentralized Neuroadaptive Control Scheme. IEEE Transactions on Control Systems Technology 2022, 32, 905–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itadera, S.; Dean-León, E.; Nakanishi, J.; Hasegawa, Y.; Cheng, G. Predictive Optimization of Assistive Force in Admittance Control-Based Physical Interaction for Robotic Gait Assistance. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2019, 4, 3609–3616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremer, S.; Das, S.K.; Wijayasinghe, I.B.; Popa, D.O.; Lewis, F.L. Model-free online neuroadaptive controller with intent estimation for physical human–robot interaction. IEEE Transactions on Robotics 2019, 36, 240–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trombley, C.; Rayguru, M.; Sharafian, P.; Kondaurova, I.; Zhang, N.; Alqatamin, M.; Das, S.K.; Popa, D.O. Neural Human Intent Estimator for an Adaptive Robotic Nursing Assistant. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 20th International Conference on Automation Science and Engineering (CASE). IEEE; 2024; pp. 2428–2434. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F.D. A technology acceptance model for empirically testing new end-user information systems: Theory and results. Ph.D. Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS quarterly 1989, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Bala, H. Technology Acceptance Model 3 and a Research Agenda on Interventions. Decision Sciences 2008, 39, 273–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahri, N.A.; Yahaya, N.; Al-Rahmi, W.M.; Aldraiweesh, A.; Alturki, U.; Almutairy, S.; Shutaleva, A.; Soomro, R.B. Extended TAM based acceptance of AI-Powered ChatGPT for supporting metacognitive self-regulated learning in education: A mixed-methods study. Heliyon 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eskandari, S.; Valente, J.P. A REVIEW OF THE APPLICATION OF TECHNOLOGY ACCEPTANCE MODELS IN THE HEALTHCARE. MCCSIS 2024, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Weßel, M.; Ellerich-Groppe, N.; Koppelin, F.; Schweda, M. Gender and age stereotypes in robotics for eldercare: ethical implications of stakeholder perspectives from technology development, industry, and nursing. Science and Engineering Ethics 2022, 28, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauk, N.; Hüffmeier, J.; Krumm, S. Ready to be a silver surfer? A meta-analysis on the relationship between chronological age and technology acceptance. Computers in Human Behavior 2018, 84, 304–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, V.; Rooksby, M.; Cross, E.S. Social robots on a global stage: establishing a role for culture during human–robot interaction. International Journal of Social Robotics 2021, 13, 1307–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haring, K.S.; Mougenot, C.; Ono, F.; Watanabe, K. Cultural differences in perception and attitude towards robots. International Journal of Affective Engineering 2014, 13, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M. Technology Acceptance Model: A Review. Journal of Advanced Research in Information Technology, Systems and Management 2023, 7, 4–7. [Google Scholar]

- Faisal, H.; Zakria, M.; Ali, N.; Khalid, N. Multilevel Modeling Approach for Hierarchical Data an Empirical Investigation. Open Journal of Statistics 2024, 14, 689–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Davis, F.D. A Theoretical Extension of the Technology Acceptance Model: Four Longitudinal Field Studies. Management Science 2000, 46, 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Tan, X.; Zheng, H. A meta-analysis of the impact of trust on technology acceptance model: Investigation of moderating influence of subject and context type. International Journal of Information Management 2011, 31, 572–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorm, E.S.; Combs, D.J. Integrating transparency, trust, and acceptance: The intelligent systems technology acceptance model (ISTAM). International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction 2022, 38, 1828–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felding, S.A.; Koh, W.Q.; Teupen, S.; Budak, K.B.; Laporte Uribe, F.; Roes, M. A scoping review using the Almere model to understand factors facilitating and hindering the acceptance of social robots in nursing homes. International Journal of Social Robotics 2023, 15, 1115–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayardoost Tabrizi, S.; Sabzian, A.; Moeini, A.; Yakideh, K. TAM-Based Model for Evaluating Learner Satisfaction of E-Learning Services Case Study: E-Learning System of University of Tehran. International Journal of Web Research 2023, 6, 105–112. [Google Scholar]

- Arthur Jr, W.; Bennett Jr, W.; Edens, P.S.; Bell, S.T. Effectiveness of training in organizations: a meta-analysis of design and evaluation features. Journal of Applied psychology 2003, 88, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkpatrick, D.L.; Craig, R.; Bittel, L. Evaluation of training. Evaluation of short-term training in rehabilitation, 1970; 35. [Google Scholar]

- Kraiger, K.; Ford, J.K.; Salas, E. Application of cognitive, skill-based, and affective theories of learning outcomes to new methods of training evaluation. Journal of applied psychology 1993, 78, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal-Rusiel, J.L.; Greve, D.N.; Reuter, M.; Fischl, B.; Sabuncu, M.R.; Initiative, A.D.N.; et al. Statistical analysis of longitudinal neuroimage data with linear mixed effects models. Neuroimage 2013, 66, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andini, N.A.M.; Dellia, P.; Ghaffar, A.; Rohimah, S.; et al. Analysis of User Satisfaction with the Dana Application Using the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) Method. Journal of Artificial Intelligence and Engineering Applications (JAIEA) 2024, 3, 824–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Gómez, E.; Martín-Salvador, A.; Luque-Vara, T.; Sánchez-Ojeda, M.A.; Navarro-Prado, S.; Enrique-Mirón, C. Content validation through expert judgement of an instrument on the nutritional knowledge, beliefs, and habits of pregnant women. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavrilas, L.; Kotsis, K.T. Development and validation of a survey instrument towards attitude, knowledge, and application of educational robotics (Akaer). International Journal of Research & Method in Education 2025, 48, 44–66. [Google Scholar]

- Bash, K.L.; Howell Smith, M.C.; Trantham, P.S. A systematic methodological review of hierarchical linear modeling in mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research 2021, 15, 190–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H. Reliability using Cronbach alpha in sample survey. The Korean Journal of Applied Statistics 2021, 34, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Kyrarini, M.; Lygerakis, F.; Rajavenkatanarayanan, A.; Sevastopoulos, C.; Nambiappan, H.R.; Chaitanya, K.K.; Babu, A.R.; Mathew, J.; Makedon, F. A survey of robots in healthcare. Technologies 2021, 9, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Yin, L.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, R.; Cai, W. Prevalence of work-related musculoskeletal disorders among nurses: a meta-analysis. Iranian journal of public health 2023, 52, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tangri, K.; Joghee, S.; Kalra, D.; Shameem, B.; Agarwal, R. Assessment of perception of usage of mobile social media on online business model through technological acceptance model (TAM) and structural equation modeling (SEM). In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Business Analytics for Technology and Security (ICBATS). IEEE; 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Hayat, M.J.; Hedlin, H. Modern statistical modeling approaches for analyzing repeated-measures data. Nursing research 2012, 61, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winkle, K.; Melsión, G.I.; McMillan, D.; Leite, I. Boosting robot credibility and challenging gender norms in responding to abusive behaviour: A case for feminist robots. In Proceedings of the Companion of the 2021 ACM/IEEE international conference on human-robot interaction; 2021; pp. 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.H.; Yen, C.L.A. Implicit and explicit attitudes toward service robots in the hospitality industry: Gender differences. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly 2023, 64, 212–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serdar, C.C.; Cihan, M.; Yücel, D.; Serdar, M.A. Sample size, power and effect size revisited: simplified and practical approaches in pre-clinical, clinical and laboratory studies. Biochemia medica 2021, 31, 27–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marangunić, N.; Granić, A. Technology Acceptance Model: A Literature Review from 1986 to 2013. Universal Access in the Information Society 2015, 14, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakens, D. Sample size justification. Collabra: psychology 2022, 8, 33267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marszalek, J.M.; Barber, C.; Kohlhart, J.; Cooper, B.H. Sample size in psychological research over the past 30 years. Perceptual and motor skills 2011, 112, 331–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abel, M.; Buccino, G.; Binkofski, F. Perception of robotic actions and the influence of gender. Frontiers in Psychology 2024, 15, 1295279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Widder, D.G. Gender and Robots: A Literature Review. arXiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).