1. Introduction

Over the past three decades, the Web has grown from a niche communication network into a foundational infrastructure that shapes how we live, work, learn, and connect with others [

1]. Yet, as the Web becomes increasingly central to societal functioning, its evolution must be guided not only by technological innovation, but also by principles of inclusivity, fairness, and sustainability [

2]. This dual relationship positions the Web as both a powerful instrument for tackling sustainability challenges and a subject of sustainability itself [

3]. On the one hand, the Web enables scalable solutions for promoting the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), such as improving education access, healthcare delivery, environmental monitoring, and civic engagement. It has the potential to democratize knowledge, amplify marginalized voices, and support data-driven policymaking. On the other hand, the development and deployment of Web technologies must adhere to sustainable and ethical practices [

4]. This includes minimizing environmental impact, ensuring accessibility and equity, and mitigating the digital divide—particularly in alignment with goals like SDG 10, which seeks to reduce inequalities within and among countries. As such, the Web must not only serve as a tool for sustainability but also exemplify it in its design, implementation, and usage. It is imperative that the next generation of Web systems be designed to empower all individuals—particularly those from vulnerable and marginalized communities—by ensuring equitable access and participation in the digital realm [

5].

Web accessibility, which ensures that people with disabilities can perceive, understand, navigate, and interact with the Web, lies at the heart of this vision [

6]. However, despite decades of standards and advocacy, accessibility remains an ongoing challenge—particularly in dynamic, component-based, and media-rich web environments [

7]. This gap calls for new approaches that can scale with the complexity of modern web development and bridge the divide between technical implementation and inclusive design [

8].

Recent advances in Large Language Model (LLM) and Multimodal AI offer a promising path forward [

9]. These models, exemplified by systems such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT and Google’s Gemini, have shown remarkable potential in a variety of domains, including code generation [

10], natural language understanding [

11], and image interpretation [

12]. Their growing integration into software development workflows opens new possibilities for building more accessible, human-centered web systems [

13]. Yet these technologies also raise important questions about bias, sustainability, and the limits of automation in ethically sensitive contexts [

14].

LLMs hold promise in streamlining the validation process for HTML code’s adherence to accessibility standards. Their adeptness at interpreting code enables them to scrutinize web content, identifying potential accessibility shortcomings such as absent alternative text, inadequate semantic structuring, or other deviations from accessibility guidelines. This potential application stands to improve the accessibility auditing process while concurrently elevating the overall quality of web content. Ultimately, this ensures the content caters inclusively to the diverse needs of all users.

This paper investigates how LLMs can support web developers in designing accessible web applications, focusing on their ability to validate and improve accessibility at both the code and content level. Through a series of controlled experiments, we assess their performance in scenarios involving dynamically generated content and asynchronous data handling. We analyze the extent to which these tools can understand and reason about accessibility constraints, and we reflect on their potential—and limitations—as responsible AI agents in web development. In doing so, this work contributes to the broader conversation on how emerging web technologies can be leveraged for social good. Our findings aim to inform researchers and practitioners seeking to integrate LLMs into accessibility workflows in a safe, equitable, and sustainable manner—supporting the Web’s evolution into a truly inclusive platform for all.

The remainder of the paper goes as follows.

Section 2 establishes the background of web accessibility and the role of LLMs in such a context.

Section 3 then details the proposed approach. The results of the experiments are presented in

Section 4. Following this,

Section 5 interprets these results in the context of existing literature and explores the implications for web development practices and accessibility tooling. Finally,

Section 6 summarizes the main contributions of our work and suggests avenues for future research in the pursuit of more accessible web environments.

2. Background and Related Work

Several works investigated the application of LLMs for web accessibility. Othman et al. [

15] study explored the potential of LLMss, specifically ChatGPT, to automatically remediate web accessibility issues and improve compliance with WCAG 2.1 guidelines. The research involved using the WAVE tool to identify accessibility errors on two non-compliant websites, subsequently employing ChatGPT for automated remediation. The effectiveness of this LLM-driven approach was evaluated by comparing its results against manual accessibility testing, offering insights for stakeholders aiming to enhance web accessibility for individuals with disabilities. Parallely, The study by Duarte et al. [

16] explores the potential of LLMs to automate the detection of heading-related accessibility barriers on webpages, addressing limitations in existing automated tools. The authors evaluate three models–Llama 3.1, GPT-4o, and GPT-4o mini–using a controlled set of modified webpages derived from a WCAG-compliant baseline. They identify seven common heading-related barriers (e.g., missing headings, incorrect hierarchy) and design prompts to query the LLMs. Results reveal model-specific strengths: Llama 3.1 excels in detecting structural and semantic barriers (e.g., heading hierarchy), while GPT-4o mini performs better at identifying nuanced problems like accessible names. However, all models struggle with detecting missing headings, underscoring the need for complementary approaches. Then, in the study of Delnevo et al. [

17], authors investigate the potential of LLMs, particularly ChatGPT 3.5, to enhance web accessibility by automating the evaluation and correction of HTML code. Research focuses on critical HTML elements such as forms, tables, and images, assessing their compliance with WCAG accessibility standards. Using a standardized prompt, they evaluate both accessible and non-accessible code snippets, highlighting cases where LLMs successfully identify and rectify issues–such as missing labels in forms or improper semantic structure in tables–while also noting limitations, such as inconsistent suggestions for equivalent accessibility attributes (e.g. scope vs. headers in tables). Moreover, López-Gil and Pereira [

18] explore the potential of LLMs to automate the evaluation of WCAG success criteria that traditionally require manual inspection. Focusing on three specific criteria–1.1.1 (Non-text Content), 2.4.4 (Link Purpose), and 3.1.2 (Language of Parts)–the authors develop LLM-based scripts to assess accessibility compliance. Their approach leverages models like ChatGPT, Claude, and Bard to analyze HTML content, compare textual descriptions, and validate language tags. The results demonstrate that LLMs achieve an 87.18% accuracy in detecting issues missed by conventional automated tools, highlighting their potential to augment accessibility testing. Finally, Huynh et al. [

19], instead, tackled the problem of image accessibility. They presented SmartCaption AI, a tool that leverages LLMs for generating context-aware descriptions of images on web pages. Unlike traditional methods that rely solely on image-to-text algorithms, SmartCaption AI enhances accuracy by first summarizing the surrounding webpage content, providing the LLM with necessary contextual cues. This ensures that generated captions are not only precise but also relevant to the broader page context. The descriptions are then embedded into the webpage’s structure, allowing screen readers to seamlessly vocalize them. The proposed system is implemented as a Chrome extension.

From an educational point of view, Aljedaani et al. [

20], investigate the integration of LLMs, specifically ChatGPT 3.5, into software engineering education to enhance students’ awareness and practical skills in digital accessibility. The study addresses persistent gaps in accessibility compliance, attributed to lack of awareness, knowledge, and practical training among developers. Through an assignment, 215 students evaluated their own websites using accessibility checker tools (WAVE and AChecker), identified violations, and employed ChatGPT to remediate issues. Results demonstrated that 60% of students resolve most violations and 30% of students fixed all violation with ChatGPT, with a general understanding and confidence improvement in implementing accessibility standards.

With regard to mobile applications, Taeb et al. [

21] delved into exploring the utilization of LLMs for assessing the accessibility of mobile applications. The researchers introduce a novel system designed to streamline the evaluation process. This system operates by initially taking a manual accessibility test as input, subsequently leveraging an LLM in conjunction with pixel-based UI Understanding models to execute the test. The outcome is a structured video presentation, divided into chapters for enhanced navigation. The generated video undergoes analysis using specific heuristics aimed at identifying and flagging any potential accessibility issues.

Finally, different perspectives have been investigated in [

22,

23]. Aljedaani et al. [

22]. They did not employed LLMs for accessibility evaluation but they investigated the accessibility of code generated by ChatGPT, focusing on its compliance with WCAG. The authors conducted an empirical evaluation involving 88 web developers who asked to ChatGPT to generate websites, which were then analyzed for accessibility violations using tools like AChecker and WAVE. The results revealed that 84% of the generated websites contained accessibility issues related to perceivability of the interface (e.g., text resizing, color contrast). While ChatGPT demonstrated a 70% success rate in fixing violations in its own code and 73% in third-party GitHub projects, it struggled with specific guidelines–particularly those concerning multimedia content, visual design, layout and spacing, multimodal navigation, and alternative input methods. Instead, Acosta-Vargas et al. [

23] present a comprehensive evaluation of the accessibility of generative AI applications with a specific focus on inclusivity for people with disabilities. Their study evaluates 50 popular generative AI tools–including ChatGPT, Copilot, Midjourney, and DALL-E 2–through a dual-method approach combining automated analysis using the WAVE tool and expert-led manual reviews, based on WCAG 2.2 criteria. The evaluation targets four core principles of accessibility: perceivability, operability, understandability, and robustness. The research identifies significant accessibility barriers in many generative AI applications, particularly related to contrast errors, lack of screen reader support, and inconsistent navigation.

3. Materials and Methods

This Section introduces the Research Questions that drove this study and describes the dataset used in the various experiments, the prompts and the LLMs used.

3.1. Research Questions

To systematically evaluate the capabilities of LLMs to identify and assess accessibility issues, we structured our study around two primary research questions:

RQ1: “How well do LLMs evaluate the accessibility of dynamically generated web content implemented with different JavaScript frameworks (i.e., Vue, React, Angular) and server-side languages (i.e., PHP)?”

RQ2: “How consistent and reliable are LLM evaluations when systematically assessing accessibility across multiple versions of table components?”

3.2. Dataset Description

To comprehensively evaluate the capabilities of LLMs in assessing web accessibility, we curated a diverse dataset designed to address our two primary RQs.

For

RQ1, which examines the LLMs’ performance on dynamically generated content, we developed code snippets that create tables using various JavaScript frameworks and the server-side language PHP. These snippets were designed to showcase different approaches to dynamic content generation, allowing us to evaluate the LLMs’ adaptability across diverse coding paradigms. We selected Vue [

24], Angular [

25], and React [

26] — three of the most widely used front-end frameworks — alongside PHP, still the dominant server-side language [

27]. Vue, React, and Angular share common characteristics, such as a component-based architecture, data-binding mechanisms, and a focus on reusability, making them well-suited for modern web applications [

28]. Each framework, however, brings its own strengths: Vue emphasizes simplicity and flexibility, Angular offers a full-featured, TypeScript-based structure with built-in tools for scalability, and React, developed by Facebook, prioritizes performance with its virtual DOM and declarative UI design. PHP, on the other hand, remains a versatile and widely adopted server-side scripting language, enabling dynamic content generation and powering popular CMS platforms like WordPress and Drupal. This diverse selection ensures our dataset reflects a broad range of web development paradigms, from client-side interactivity to server-side content rendering.

To investigate the consistency and reliability of LLM evaluations across component versions (RQ2), we utilized a dataset of 25 distinct implementations of Vue table components. These components, developed by students from the Web Applications and Services course at the University of Bologna, featured variations in accessibility features, API usage (Composition vs. Options), and overall structure. This diverse dataset provided a rich foundation for assessing the LLMs’ ability to track and evaluate accessibility changes across iterative component development. While we initially explored accessibility evaluations across Vue, React, Angular, and PHP, a more focused approach was necessary for a systematic evaluation of component variations. Specifically, we required a substantial number of implementations centered on a consistent component type (tables), to ensure a robust comparative analysis. To achieve this, we collaborated with the student developers, whose coursework extensively covered Vue, making it the practical choice for our in-depth study. Furthermore, given the architectural similarities among modern JavaScript frameworks like Vue, React, and Angular, we posit that findings derived from a thorough analysis of Vue components are likely to offer insights applicable across these frameworks. It is reasonable to hypothesize that the general trends and patterns observed in LLM evaluations of Vue components would manifest similarly in React and Angular, particularly concerning common accessibility patterns and challenges. Additionally, focusing on a single framework enabled us to achieve a higher degree of granularity in our analysis, allowing for a deeper exploration of specific accessibility nuances and their impact on LLM evaluations. This decision also reflected practical considerations, such as the resources and time constraints inherent in conducting a comprehensive analysis across multiple frameworks. By prioritizing depth over breadth in this phase of our research, we aimed to provide a more detailed and actionable understanding of LLM capabilities in assessing web component accessibility.

All code used in this study has been reported in a GitHub repository

1.

3.3. Prompt Design and Methodology

To ensure a consistent and thorough evaluation of LLM performance across our research questions, we carefully crafted tailored prompts for each scenario. Each prompt aligns with the specific goal of the corresponding research question, ensuring that the model’s output remains focused on the accessibility criteria under investigation. To enhance the effectiveness of these prompts, we employed various prompt engineering techniques, including role prompting [

29]. This involved instructing the LLM to adopt specific roles, such as an accessibility expert or a code reviewer, to guide its analysis and responses. By defining clear roles and providing precise instructions, we aimed to elicit more accurate and relevant evaluations of the accessibility issues present in our dataset. Below, we describe the design and rationale for each prompt, detailing how these techniques were implemented to optimize the LLM’s performance.

For RQ1, where the focus is on dynamically generated content from various frameworks and server-side languages, we crafted a prompt to evaluate accessibility across different paradigms. This prompt acknowledges the interactive nature of the content and asks the model to assess the resulting output:

You are a tool for detailed web accessibility validation.

Analyze the following dynamically generated web content.

The content is produced by a code snippet written in one of the following: Vue, React, Angular, or PHP.

Evaluate the resulting output for accessibility issues according to WCAG 2.2 AA guidelines.

For each issue identified, include:

- The affected element or code portion.

- The corresponding WCAG criterion.

- A brief explanation of the issue.

- A recommendation for fixing it.

— Code Snippet —

$code_snippet$

This design ensures the LLM not only processes the code itself but also infers the resulting structure, focusing on end-user accessibility.

For RQ2, we designed a two-step process to maximize violation detection and identify hallucinations. The prompts support a systematic evaluation of multiple Vue table component implementations, ensuring consistent output formatting. First, a prompt is used to retrieve WCAG 2.2 AA guideline violations found on individual web pages. The prompt is:

You are a tool for detailed web accessibility validation.

Is this VUE component accessible according to WCAG 2.2 guidelines (which include previous WCAG 2.0 and 2.1 standards) at the AA level?

Analyze the following VUE files that make up the component.

After the analysis, create a table with the list of WCAG violations you found, indicating:

- In the first column, the relative success criterion.

- In the second column, the part of code analyzed or a summary of it.

- In the third column, a short description of the problem.

— File: $filename$—

$filecontent$

Then, each violation has been manually evaluated by three reviewers and marked as: OK (if it is correct), A (if it is hallucination), and R (if it is redundant).

Second, a more targeted prompt is employed for each identified violation to confirm its validity and distinguish it from a hallucination. This approach, similar to Chain-of-Verification [

30], requires the LLM to verify its findings incrementally. By checking each part of its response, the LLM can minimize errors and enhance the accuracy of its results. The prompt for the second step is:

You are a tool for detailed web accessibility validation.

I ask you to verify the correctness of the following WCAG 2.2 accessibility issue reports (including WCAG 2.1 and 2.0) generated for components of a Vue.js application.

Create a new markdown table about accessibility issues, similar to the one below, by adding 2 columns: Correctness and Description.

In the "Correctness" column, enter:

"OK" if the reported issue is actually present on the page.

"A" if it is a hallucination (an accessibility error reported that does not actually exist).

"R" if the report is redundant. "Redundant" refers to a suggestion or recommendation provided by the model that, based on the analysis of the rendered HTML code below, does not appear useful or correct.

In the "Description" column, provide a brief justification for your assessment.

Below is the table of reports to verify, followed by the HTML-rendered code of the Vue.js component (rendered using a Node.js server and Chrome browser).

$step 1 result$

$HTML Code Rendered$

This structured output facilitates comparative analysis across the 25 different student-implemented Vue table components, enabling systematic reliability checks.

3.4. Large Language Models

LLMs are self-supervised foundational models that can be prompted or fine-tuned to perform a wide array of natural language processing tasks that once required separate, task-specific systems [

31,

32]. These models are typically built on the Transformer architecture and trained on massive corpora, enabling them to generalize across tasks such as text generation, summarization, question answering, and code understanding [

33]. Their versatility has led to widespread adoption across diverse fields including healthcare [

34], education [

35], and software development.

In this study, we employed three LLMs: GPT-4o mini [

36], o3-mini [

37], and Gemini 2.0 Flash (Gemini) [

38]. These models reflect the current state of scalable instruction-following language models. GPT-4o mini and o3-mini are proprietary models by OpenAI, optimized for performance and efficiency. GPT-4o (short for “omni”) is the latest model in the GPT-4 family, designed for multimodal tasks while maintaining strong natural language understanding and generation capabilities. The mini variants used in our experiments are optimized for speed and cost while retaining a high level of linguistic and reasoning competence.

Gemini, developed by Google DeepMind, is a lightweight and fast variant of the Gemini series, following earlier iterations such as LaMDA and PaLM [

39,

40]. This model is designed to provide rapid responses while maintaining strong instruction-following behavior, making it particularly suitable for real-time evaluation tasks like those required in our accessibility assessment scenarios.

All models were used in zero-shot inference mode via prompting, without any additional fine-tuning. We compared their outputs in terms of consistency, completeness, and alignment with WCAG 2.2 standards. Leveraging multiple LLMs allowed us to examine not only overall performance but also the variation in accessibility evaluation across different architectures and training strategies.

4. Results

The answers to the two Research Questions are discussed in isolation in the following Subsections.

4.1. Validation of Dynamic Generation of HTML Code

In this set of experiments, the evaluation of the accessibility is conducted on the code that generates dynamically the HTML code, taking advantage of frontend Javascript frameworks (i.e., Vue, Angular, and React) and PHP. The experiments are all focused on the generation of the same HTML table.

4.1.1. Accessible Components

The first set of experiments conducted were focused on components that should produce accessible tables.

Table 1 presents the accessibility issues identified by the GPT-4o mini model across dynamically generated table components developed in Angular, React, Vue, and PHP. Although the components were intended to produce accessible tables, several recurring accessibility problems were systematically detected, highlighting common pitfalls even in seemingly well-designed dynamic content.

Non-unique dynamic IDs were reported in Angular, React, and Vue components. This issue violates WCAG Success Criterion 1.3.1 (Info and Relationships), as duplicate IDs can disrupt assistive technologies that rely on a well-formed DOM structure to correctly interpret and navigate page content. The recommended solution involves appending a unique suffix, such as an index value, to dynamically generated IDs to maintain uniqueness.

Across all frameworks and technologies, missing descriptive summaries for the tables were detected, impacting both WCAG 1.3.1 and 1.1.1 (Non-text Content). Providing a clear summary or description is essential for screen reader users to understand the structure and purpose of complex data tables. The LLM suggested using aria-describedby attributes linked to a hidden textual description to address this issue effectively.

Another accessibility gap observed in Angular, React, and Vue components was the absence of loading messages during dynamic content updates, a violation of WCAG 4.1.3 (Status Messages). Without an indication of loading progress, users relying on assistive technologies may experience confusion or uncertainty. Implementing an aria-live region that announces a “Loading...” message ensures that updates are communicated properly to users.

Finally, a lack of error messaging on failure conditions was consistently found across all evaluated technologies, infringing on WCAG 3.3.1 (Error Identification). Without accessible error feedback, users may struggle to understand why a process failed or how to correct it. The suggested remediation involves displaying accessible error messages using ARIA roles such as role="alert" to ensure immediate notification through assistive devices.

Then, we evaluate the same components using Gemini. The results are summarized in

Table 2. Despite the developers’ intention to produce accessible tables, several accessibility deficiencies were highlighted, common to all technologies assessed.

One issue reported across all components was the incorrect use of <th> elements inside <tbody> sections, marked as a violation of WCAG 1.3.1 (Info and Relationships). However, it is important to note that this detection is incorrect: the use of <th> within <tbody> is valid according to the HTML standard and is commonly employed to define row headers within body rows, particularly in complex tables. Thus, this false positive suggests a limitation in Gemini’s handling of advanced table semantics.

A legitimate concern raised was the potentially insufficient contrast for text content, mapped to WCAG 1.4.3 (Contrast Minimum). Ensuring sufficient contrast between text and background is crucial for readability, especially for users with visual impairments. Gemini suggested verifying and adjusting CSS styles applied to table cells to maintain an adequate contrast ratio, a particularly relevant issue as developers often overlook contrast when styling table content.

Gemini also detected redundant and potentially confusing use of the headers attribute in <td> elements. According to WCAG 1.3.1, the headers attribute should be used judiciously, pointing clearly to the id of the corresponding <th> element. Incorrect or excessive use of this attribute can confuse assistive technologies, leading to incorrect interpretation of table relationships. The suggested fix is to simplify and correctly reference column headers.

Finally, Gemini flagged the absence of the summary attribute on <table> elements, again under WCAG 1.3.1. Although the summary attribute is now considered obsolete in HTML5 (with the recommendation to use alternative mechanisms like aria-described-by or a visible caption), its suggestion highlights a persistent tension between formal guidelines and evolving web standards. This observation indicates that Gemini may still prioritize backward-compatible practices in certain cases.

4.1.2. Non-Accessible Components

After the evaluation of components that should produce accessible tables, we moved to components that produce non-accessible tables. In particular, even if table cells have both row and column headings, neither the scope attribute nor the headers attribute were employed.

Table 3 reports the accessibility issues detected by GPT-4o mini in the table components designed to be non-accessible, implemented with Angular, React, Vue, and PHP. As expected, the number and severity of detected violations increased compared to the components intended to be accessible, confirming the tool’s ability to identify meaningful differences in accessibility compliance.

Two critical issues emerged regarding the semantic structure of tables:

Missing scope="col" on column headers: According to WCAG 1.3.1 (Info and Relationships), properly setting the scope attribute in <th> elements is crucial to help assistive technologies interpret the relationship between headers and their corresponding cells. In these non-accessible versions, this attribute was omitted, making it difficult for screen readers to correctly associate headers with data.

Missing scope="row" on row headers: Similarly, for row headers, the absence of scope="row" further degrades the semantic clarity of the tables. Without these markers, navigating large tables becomes significantly more difficult for users relying on assistive technologies.

These issues were not present in the accessible versions, highlighting that proper use of the scope attribute was effective in improving accessibility there.

Several issues were also detected in the accessible components (i.e., no loading message, no error message on failure, and no detailed description of the table) and were highlighted again, suggesting a consistency of evaluation among the various components.

With regard to the evaluation conducted with Gemini, the results are summarized in

Table 4.

Table 4 presents the accessibility issues identified by Gemini in the intentionally non-accessible table components built with Angular, React, Vue, and PHP. In a manner parallel to the findings observed with o3-mini on these same components, beyond the issues previously identified in the accessible versions of these components, Gemini additionally flagged the absence of both scope and id attributes within the table header cells (<th>) located in the <head>.

4.1.3. Cross-Framework and Language Accessibility Evaluation by LLMs

The results demonstrate that LLM-based models, specifically GPT-4o mini and Gemini, are capable of detecting a wide range of accessibility issues in dynamically generated web components across different JavaScript frameworks (Vue, React, Angular) and PHP. However, their performance also reveals distinct strengths and limitations.

Overall, both models consistently identified critical accessibility problems affecting dynamically generated tables. Improper scope and headers management for table elements, were systematically detected across all frameworks, indicating that LLMs generalize well across different frontend and backend technologies.

When evaluating components intended to be accessible, both GPT-4o mini and Gemini successfully pinpointed subtle but important shortcomings. GPT-4o mini focused more on semantic and interaction aspects (e.g., dynamic ID generation, live updates, error reporting), while Gemini highlighted additional presentation issues, like color contrast problems. However, Gemini also exhibited a notable false positive (incorrectly reporting the use of <th> in <tbody> as a violation), revealing that its knowledge about valid complex table semantics was not fully aligned with modern HTML standards.

In evaluating non-accessible components, both models correctly detected the missing use of scope and headers attributes. This confirms that the models are sensitive enough to distinguish between different levels of accessibility compliance and can detect both superficial and deep structural accessibility flaws.

In summary, LLMs such as o3-mini and Gemini can effectively evaluate the accessibility of dynamically generated web content across different frameworks and languages, identifying both high-level and detailed WCAG violations. However, occasional inaccuracies and outdated suggestions imply that their outputs should be critically reviewed by accessibility experts before being fully trusted in critical evaluation contexts.

4.2. Vue Table Components Analysis

4.2.1. Initial Accessibility Violation Detection

In the initial phase of our evaluation, we employed the first prompt detailed in

Section 3.3 to analyze accessibility issues using both GPT-4o mini and Gemini, subsequently conducting a manual expert review of the detected issues.

The findings for GPT-4o mini and Gemini are respectively summarized in

Table 5 and

Table 6. GPT-4o mini detected a total of 512 violations across various WCAG criteria. Of these, 103 issues (20.1%) were judged fully correct (OK), while 358 issues (69.9%) were classified as hallucinations (A), meaning that although the model flagged real accessibility concerns, the details or severity were partially incorrect or incomplete. Only a small fraction, 51 issues (10.0%), were classified as redundant (R), indicating false positives where no genuine accessibility problem existed.

Conversely, the results for Gemini showed a different profile. A total of 384 violations were detected, with 113 issues (29.5%) deemed fully correct (OK) and 77 issues (20.1%) classified as hallucinations (A). However, a significant number — 193 issues (50.4%) — were considered redundant (R), revealing a greater tendency of Gemini to flag accessibility violations that, upon manual inspection, were found to be incorrect or not impactful.

In both cases, Criterion 1.3.1 (Info and Relationships) yielded the highest number of detections (167 and 189 cases for GPT-4o mini and Gemini, respectively). However, the classification differed notably between the two models: for GPT-4o mini, the majority of these detections were marked as hallucinations, suggesting frequent but only partially accurate identification of semantic issues. For Gemini, a significant portion under Criterion 1.3.1 was instead classified as redundant, indicating a high rate of false positives related to the interpretation of semantic relationships.

It is also noteworthy that Gemini achieved a higher percentage of fully correct detections (29.5%) compared to GPT-4o mini (20.1%), suggesting better precision in those cases where the model correctly identified an accessibility problem. Furthermore, Gemini demonstrated a considerably lower proportion of hallucinations (20.1% versus 69.9%), meaning that when it raised issues, they were more often either entirely correct or entirely wrong, with fewer partially accurate findings.

Nevertheless, this advantage came at the cost of a much higher redundancy rate (50.4% versus 10.0%), indicating that Gemini flagged many issues that were not actually accessibility violations, which could potentially overwhelm developers with unnecessary corrective actions and reduce the practical efficiency of its assessments.

In summary, these results highlight a fundamental trade-off between the two LLMs. While GPT-4o mini tends to identify a broader set of potential accessibility concerns, its inclination towards generating a high number of reports requiring human verification and interpretation represents a significant limitation. Conversely, Gemini demonstrates slightly better precision in correct detections, but this quality is counterbalanced by a considerable risk of over-reporting and potentially hallucinations, undermining the overall effectiveness of the system.

4.2.2. Consistency and Reliability of LLM Accessibility Evaluations

Following the initial detection of accessibility violations, described in the previous subsection, a second verification phase was introduced to validate the correctness of each issue. This step employed a targeted prompt inspired by the Chain-of-Verification approach [

30], where each model was required to reassess its own outputs by incrementally analyzing its reported violations in the context of the rendered HTML source code. This method allowed for a more controlled inspection of each LLM’s self-consistency and factual grounding.

The results of this second step is summarized in

Table 7 and

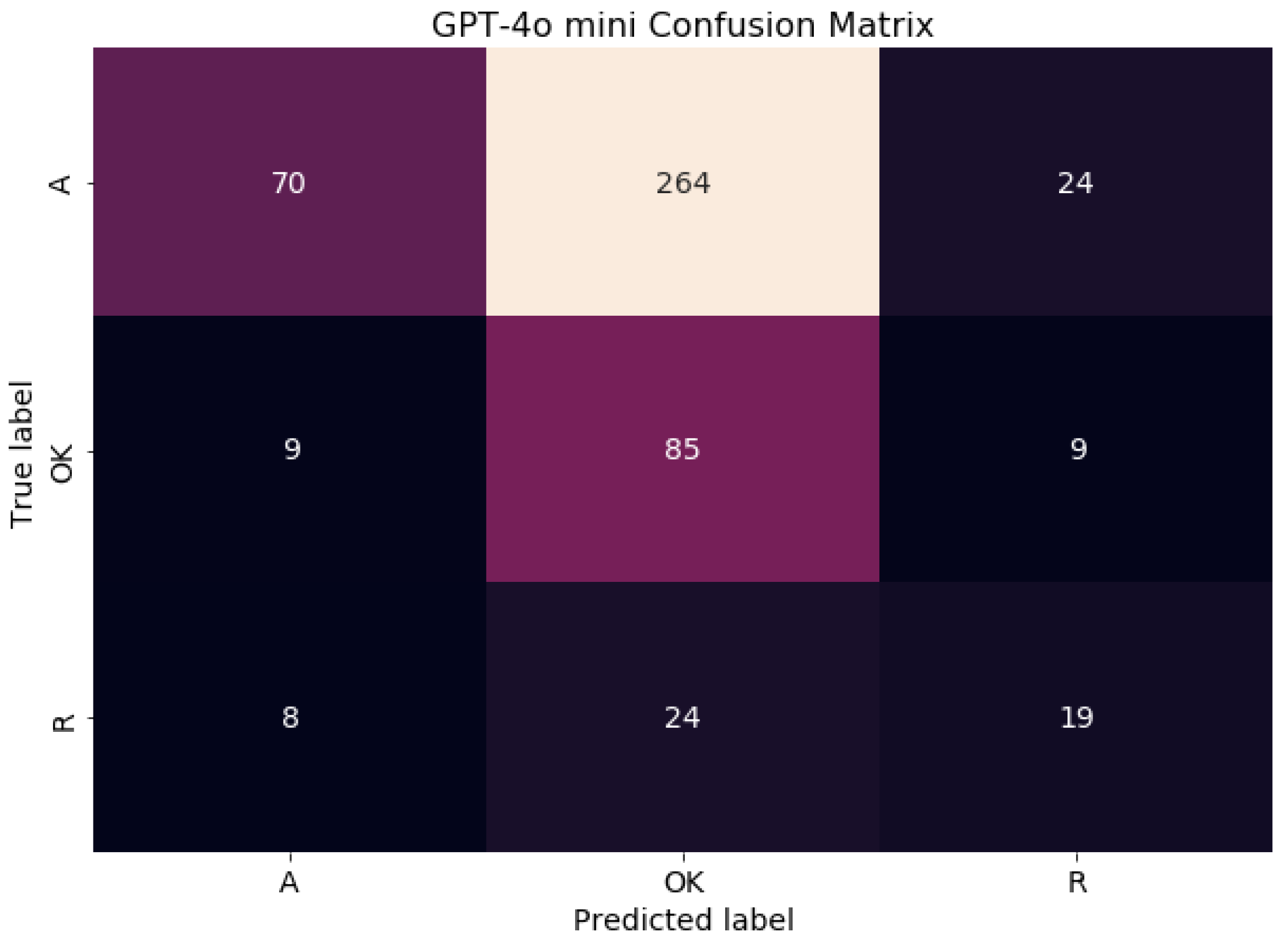

Table 8. GPT-4o mini demonstrated limited reliability, achieving an overall accuracy of 34%. While it performed well in recognizing actual accessibility issues (Recall

OK = 0.83), its low Precision for that class (0.23) indicates a high false-positive rate. Notably, it exhibited poor consistency in identifying hallucinated issues (Recall

A = 0.2), meaning it frequently failed to recognize when a previously reported hallucination was invalid. Its balanced performance in detecting redundant issues (F1

R = 0.37) was moderate, but not particularly strong.

The relative confusion matrix, depicted in

Figure 1, reveals how the GPT-4o mini model performed in classifying violations as Hallucinations, Ok, or Redundant. It shows the counts of correct and incorrect predictions for each category. Notably, the model struggled most with accurately identifying Hallucinations, often misclassifying them as Ok. The Ok category also saw some misclassifications, while the Redundant category had a relatively lower number of correct predictions compared to its errors. Overall, the matrix highlights the specific types of classification mistakes the model made across the different violation categories.

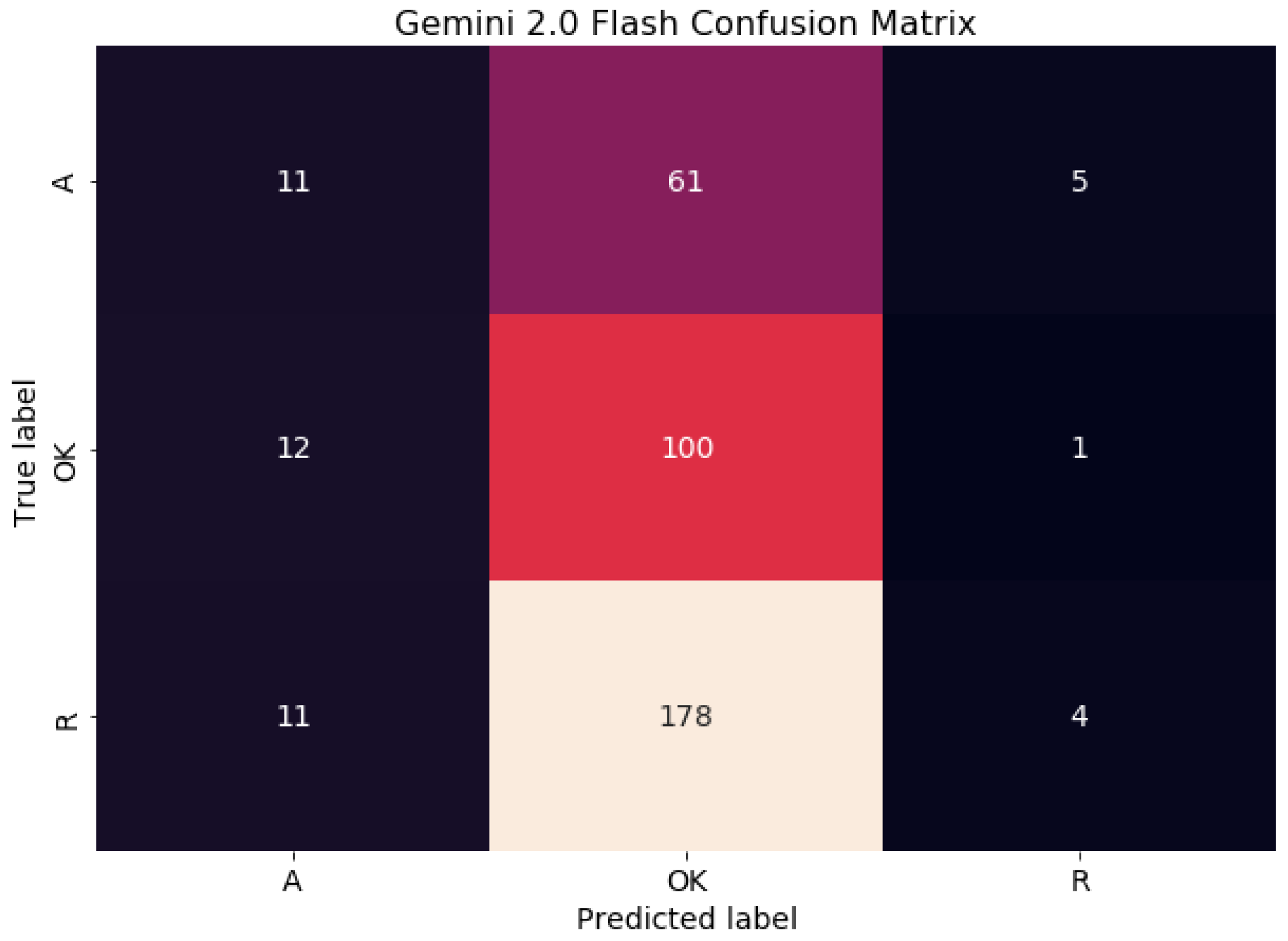

Gemini yielded an even lower overall accuracy of 30%, and its classification reliability was markedly inconsistent across classes. It achieved the highest recall for correct issues (RecallOK = 0.88), suggesting strong sensitivity to real violations. However, the precision for this class was modest (0.29), again reflecting a substantial number of false positives. The model performed especially poorly in identifying redundant outputs (RecallR = 0.02), indicating it was largely unable to recognize when its own suggestions were unnecessary or irrelevant.

The confusion matrix (

Figure 2 for Gemini illustrates its performance in classifying violations into Hallucinations (A), Ok, and Redundant (R) categories. Looking at the matrix, we can see how many instances of each true category were correctly and incorrectly predicted by the model. For Hallucinations, while some were correctly identified, a larger number were misclassified as Ok. The Ok category shows a high number of correct classifications, but also some instances incorrectly labeled as Hallucinations and Redundant. Finally, for the Redundant category, there were a few correct predictions, but a significant number were wrongly classified as Ok. This matrix provides a clear picture of the specific types of errors Gemini made across the different violation types.

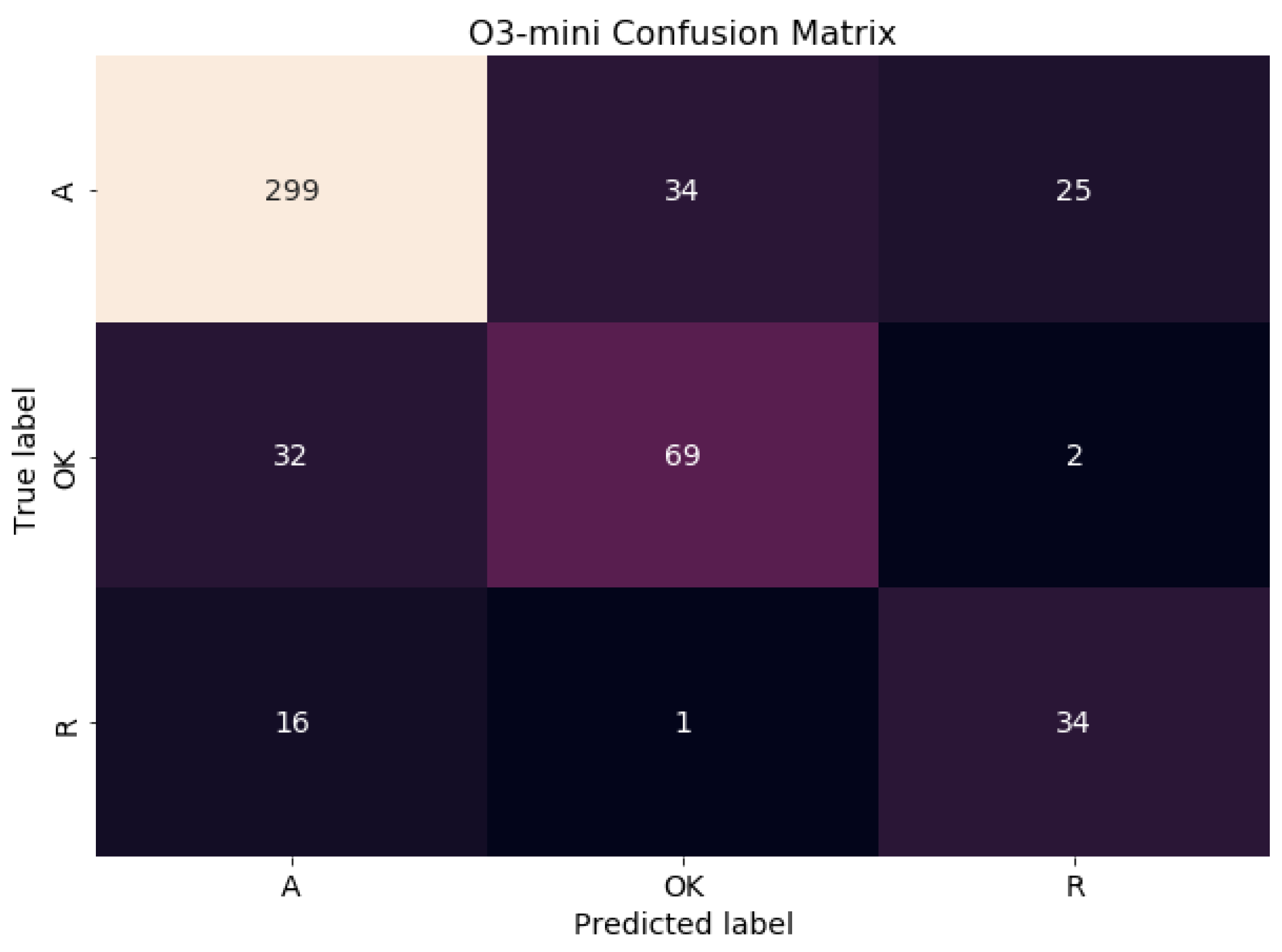

Finally, we conducted a further test using a more powerful model, O3-mini, which analyzed the violations raised by GPT 4o-mini. In contrast to the previous models, O3-mini exhibited significantly more consistent and reliable behavior, achieving an overall accuracy of 79%. It demonstrated strong performance across all classes, particularly in detecting hallucinations (F1A = 0.85) and correctly identifying redundant suggestions (F1R = 0.61). Unlike the other two models, O3-mini balanced both precision and recall effectively, resulting in a respectable F1-score of 0.67 for actual accessibility violations.

Table 9.

Performance metrics for O3-mini’s classification of previous output violations identified by GPT-4o mini.

Table 9.

Performance metrics for O3-mini’s classification of previous output violations identified by GPT-4o mini.

| Class |

Precision |

Recall |

F1-Score |

Support |

Accuracy |

| A |

0.86 |

0.84 |

0.85 |

358 |

0.79 |

| OK |

0.66 |

0.67 |

0.67 |

103 |

| R |

0.56 |

0.67 |

0.61 |

51 |

The confusion matrix for O3-mini, which analyzed violations identified by GPT 4o-mini, reveals a strong performance in classifying these violations. The model correctly identified a large number of Hallucinations (A), with fewer being misclassified as Ok or Redundant. For truly Ok violations, O3-mini showed a good level of accuracy, with a smaller number being incorrectly labeled as Hallucinations. The Redundant (R) category also saw a reasonable number of correct classifications, although some were misidentified as Hallucinations. Overall, the matrix indicates that O3-mini demonstrates a better ability to distinguish between these violation types compared to the previous models, aligning with its reported higher accuracy and balanced precision-recall.

Figure 3.

Confusion Matrix of O3-mini’s classification of previous output violations identified by GPT-4o mini.

Figure 3.

Confusion Matrix of O3-mini’s classification of previous output violations identified by GPT-4o mini.

These findings underscore that while GPT-4o mini and Gemini are capable of generating plausible accessibility reports even suffering from hallucinations and redundant violations, they suffer from low self-verification reliability, particularly in distinguishing between valid, redundant, and hallucinated issues. Their limited ability to reassess their own outputs poses risks for over-reporting or misguiding developers in real-world auditing scenarios. By contrast, O3-mini appears to offer a more dependable approach to systematic accessibility evaluation, especially when applied in multi-stage workflows where validation and refinement are essential.

Addressing RQ2 of how consistent and reliable LLM evaluations are when systematically assessing accessibility across multiple versions of table components, the results of our second evaluation phase reveal significant inconsistencies and varying levels of reliability among different LLMs. The stark contrast observed, with O3-mini demonstrating high accuracy while GPT-4o mini and Gemini exhibited relatively poor performance in verifying accessibility violations, underscores the critical need for robust internal validation within LLMs used for such tasks. Although initial outputs from all models appeared plausible, only O3-mini consistently and reliably distinguished between actual issues, hallucinations, and redundant suggestions during the self-verification process. This finding indicates that the initial output quality of an LLM is not a sufficient measure of its practical reliability for accessibility evaluations; a systematic self-verification step is crucial for ensuring robustness. The inconsistency observed, where over-reporting can lead to wasted effort and under-reporting to non-compliance, poses a serious challenge for real-world applications. Consequently, these findings strongly support the necessity of multi-step LLM evaluation pipelines and prompt further investigation into how architectural differences or training objectives influence a model’s ability to reason reliably when performing systematic accessibility assessments across table component versions.

5. Discussion and Limitations

The results of this study demonstrate both the promise and current limitations of using LLMs for automated accessibility evaluations of dynamically generated web content. In addressing RQ1, the evaluation shows that both GPT-4o mini and Gemini are capable of identifying a broad spectrum of accessibility violations across multiple frontend frameworks and backend technologies. These models consistently surfaced key issues such as missing scope attributes, redundant or incorrect use of headers, and absent dynamic feedback mechanisms—violations that are crucial to ensuring WCAG compliance. However, despite their capacity to detect many legitimate issues, both models also produced a substantial number of hallucinated or redundant violations. These inaccuracies suggest a knowledge gap or misalignment with current HTML5 semantics. Additionally, the reliance on deprecated attributes like summary points to a tendency in some models to prioritize outdated best practices, potentially introducing confusion or unnecessary remediation work for developers.

In addressing RQ2, the evaluation revealed significant disparities in model reliability when subjected to a verification phase using the Chain-of-Verification-inspired prompt. Here, both GPT-4o mini and Gemini displayed weak self-consistency, with low overall accuracy (34% and 30%, respectively), high false positive rates, and limited ability to correctly reassess hallucinated or redundant violations. The performance gaps between detection and verification stages underscore a fundamental limitation in their reasoning stability and factual grounding, which is critical for trustworthy automated evaluations. By contrast, the O3-mini model, when used in a second-stage validation role, demonstrated markedly superior consistency and judgment, achieving a high overall accuracy of 79%. It excelled not only in distinguishing valid issues from hallucinations but also in recognizing when previously flagged items were either spurious or redundant. This finding suggests that a tiered evaluation pipeline—where a high-recall model conducts the initial pass and a more conservative, high-precision model validates those findings—could be a viable and practical strategy for integrating LLMs into real-world accessibility audits.

One of the most interesting results obtained is that LLMs can make some considerations about web accessibility based on the dynamic behavior of the elements. In the experiments, LLMs raised accessibility concerns regarding asynchronous data loading and error handling. Such issues can not be detected by standard validation tools. Such a capability has the potential to upend the validation process. Before, when using server-side languages or Javascript frameworks, the validation process was to be carried out on the generated HTML code for each dynamic page. Taking advantage of LLMs, the validation process can be continuously carried out while developing the code base. The cross-framework consistency of detection also suggests that LLMs are sufficiently abstracted from framework-specific syntax to generalize accessibility reasoning across languages like PHP and JavaScript-based frontend libraries. This opens opportunities for scalable accessibility checks in continuous integration pipelines regardless of the underlying stack.

On the negative side, despite their potential benefits, the experiments conducted illustrate that utilizing LLMs without human oversight poses challenges. The inconsistencies, especially in hallucination management and redundant suggestion identification, underscore the risks of deploying LLMs for automated audits without human oversight. Over-reporting can lead to audit fatigue or unnecessary fixes, while under-reporting critical issues risks poor user experience for people with disabilities. Then, the content generated by LLMs may perpetuate biases and inaccuracies inherent in their training data, as highlighted in previous studies [

41]. This raises concerns about over-reliance on LLM output, leading to potential neglect of manual review and correction [

42]. Furthermore, in many jurisdictions, compliance with accessibility standards is a legal obligation, and web developers ultimately bear the responsibility for ensuring adherence to these standards [

43]. The results advocate for future research focused on refining LLM behavior through prompt engineering, feedback-loop training, or architectural improvements to promote better fact-grounding and domain alignment.

Ultimately, while LLMs are well-positioned to assist in accessibility evaluation tasks, their integration must be framed within a structured, multi-step validation pipeline, ideally guided by expert review and aligned with modern web standards. Further investigation into model behavior on domain-specific knowledge, semantic parsing of complex HTML structures, and evolution-aware guideline interpretation (e.g., accounting for HTML5 updates) will be critical to advancing the dependability of LLMs in this space.

5.1. Limitations

It is important to acknowledge several limitations inherent in our current study. First, it is important to note that while the implemented components in our experiments exhibited significant diversity in their internal structure, they were limited in scope, primarily generating tables rather than fully functional websites. It is worth considering, however, that validating table generation, as performed by the components in our dataset, represents one of the more complex aspects of accessibility validation.

In addition, the validation of individual components does not guarantee the accessibility of the overall HTML page. Indeed, various accessibility issues can emerge when integrating these components into a complete web page.

Our systematic investigation focused primarily on components built with Vue. We hypothesized that the behavior observed would not differ significantly across other frameworks (such as React or Angular) or languages (like PHP). However, a comprehensive evaluation encompassing each of these technologies would be necessary to rigorously confirm this assumption.

Furthermore, the handling of images warrants separate and more in-depth consideration. The generation of effective alternative text is highly context-dependent, varying based on the specific role an image plays within a webpage.

Finally, the challenges extend beyond image accessibility to encompass other crucial aspects such as accommodating color blindness and ensuring sufficient color contrast. To address these multifaceted issues comprehensively, a multimodal approach could be implemented, considering not only the HTML code but also the associated CSS and the final rendered output of the web page.

6. Conclusion and Future Works

As the Web continues to evolve into a critical infrastructure for modern society, ensuring its inclusivity, equity, and sustainability becomes not only a technical challenge but also a moral imperative. This paper has explored the emerging role of LLM in supporting web developers toward more accessible and human-centered web design. Through a series of targeted experiments, we demonstrated that state-of-the-art LLMs such as ChatGPT and Gemini can effectively identify common accessibility issues in both static and dynamically generated content, providing valuable insights on code structure, semantic correctness, and even user experience considerations such as asynchronous data handling.

Our findings highlight a key opportunity: LLMs can serve as real-time collaborators that integrate accessibility validation into the development workflow, potentially lowering the barriers to inclusive design and helping democratize web accessibility knowledge. However, this potential comes with important caveats. LLMs are not infallible—they can overlook nuanced accessibility challenges, propagate biases from training data, and struggle with multimodal or context-dependent content. Human oversight, critical reflection, and a deep understanding of accessibility principles remain indispensable.

This paper paves the way for several future works. Some experiments could be focused on the fine-tuning of LLMs with the perspective of web accessibility to make the model understand some very specific and advanced aspects of it. Another promising research direction involves leveraging LLMs to generate concise and comprehensible summaries of web content, enhancing accessibility for individuals with cognitive disabilities or those seeking shorter, more digestible information. Furthermore, integrating a conversational agent into the website could further bridge the accessibility gap. Users with disabilities could interact with this agent directly, bypassing the need to navigate the website’s interface to locate specific information.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.D. and P.S.; methodology, B.B.; software, B.B.; validation, M.A., B.B. and G.D.; data curation, M.A.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A., B.B.; writing—review and editing, G.D. and P.S.; visualization, M.A.; supervision, P.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

We thank Giulia Bonifazi for her precious support and all the students who developed a version of the Vue components. During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the authors used ChatGPT for the purposes of writing assistance. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LLM |

Large Language Model |

| SDGs |

Sustainable Development Goals |

References

- Hall, W.; Tiropanis, T. Web evolution and Web Science. Comput. Netw. 2012, 56, 3859–3865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S., M.; Nallasivam, A.; K. N., A.S.I.; Desai, K.; Kautish, S.; Ghoshal, S. Universal Access to Internet and Sustainability: Achieving the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals. In Digital Technologies to Implement the UN Sustainable Development Goals; Springer Nature Switzerland, 2024; pp. 235–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathor, S.; Zhang, M.; Im, T. Web 3.0 and Sustainability: Challenges and Research Opportunities. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huda, M. Empowering application strategy in the technology adoption: Insights from professional and ethical engagement. J. Sci. Technol. Policy Manag.t 2019, 10, 172–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warschauer, M.; Matuchniak, T. New Technology and Digital Worlds: Analyzing Evidence of Equity in Access, Use, and Outcomes. Rev. Res. Educ. 2010, 34, 179–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leuthold, S.; Bargas-Avila, J.A.; Opwis, K. Beyond web content accessibility guidelines: Design of enhanced text user interfaces for blind internet users. Int. J. -Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2008, 66, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ara, J.; Sik-Lanyi, C.; Kelemen, A. Accessibility engineering in web evaluation process: a systematic literature review. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2023, 23, 653–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herlina. Integrating Accessibility Features and Usability Testing for Inclusive Web Design. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Intelligent Cybernetics Technology & Applications (ICICyTA); IEEE, 2024; pp. 1284–1289. [CrossRef]

- Duarte, C.; Costa, M.; Seixas Pereira, L.; Guerreiro, J. Expanding Automated Accessibility Evaluations: Leveraging Large Language Models for Heading-Related Barriers. In Proceedings of the Companion Proceedings of the 30th International Conference on Intelligent User Interfaces. ACM, 2025, IUI ’25; pp. 39–42. [CrossRef]

- Zan, D.; Chen, B.; Zhang, F.; Lu, D.; Wu, B.; Guan, B.; Yongji, W.; Lou, J.G. Large Language Models Meet NL2Code: A Survey. In Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers); 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Xu, J.; Gui, H.; Sun, M.; Zhang, Z.; Liang, L.; Zhou, J. Improving Natural Language Understanding for LLMs via Large-Scale Instruction Synthesis. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 2025, 39, 25787–25795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koga, S. Advancing large language models in nephrology: bridging the gap in image interpretation. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 2024, 29, 128–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Gil, J.M.; Pereira, J. Turning manual web accessibility success criteria into automatic: an LLM-based approach. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2024, 24, 837–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Guan, S.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H. Towards trustworthy LLMs: a review on debiasing and dehallucinating in large language models. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, A.; Dhouib, A.; Nasser Al Jabor, A. Fostering websites accessibility: A case study on the use of the Large Language Models ChatGPT for automatic remediation. In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on PErvasive Technologies Related to Assistive Environments. ACM, 2023, PETRA `23; 2023; pp. 707–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, C.; Costa, M.; Seixas Pereira, L.; Guerreiro, J. Expanding Automated Accessibility Evaluations: Leveraging Large Language Models for Heading-Related Barriers. In Proceedings of the Companion Proceedings of the 30th International Conference on Intelligent User Interfaces. ACM, 2025, IUI ’25; pp. 39–42. [CrossRef]

- Delnevo, G.; Andruccioli, M.; Mirri, S. On the Interaction with Large Language Models for Web Accessibility: Implications and Challenges. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 21st Consumer Communications & Networking Conference (CCNC). IEEE; 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Gil, J.M.; Pereira, J. Turning manual web accessibility success criteria into automatic: an LLM-based approach. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2024, 24, 837–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, G.K.; Lin, W. SmartCaption AI - Enhancing Web Accessibility with Context-Aware Image Descriptions Using Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Computer and Applications (ICCA). IEEE; 2024; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljedaani, W.; Eler, M.M.; Parthasarathy, P.D. Enhancing Accessibility in Software Engineering Projects with Large Language Models (LLMs). In Proceedings of the 56th ACM Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education V. 1. ACM, 2025, SIGCSE TS 2025; 2025; pp. 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taeb, M.; Swearngin, A.; School, E.; Cheng, R.; Jiang, Y.; Nichols, J. AXNav: Replaying Accessibility Tests from Natural Language. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.02424. [Google Scholar]

- Aljedaani, W.; Habib, A.; Aljohani, A.; Eler, M.; Feng, Y. Does ChatGPT Generate Accessible Code? Investigating Accessibility Challenges in LLM-Generated Source Code. In Proceedings of the 21st International Web for All Conference. ACM, 2024, W4A ’24; 2024; pp. 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta-Vargas, P.; Salvador-Acosta, B.; Novillo-Villegas, S.; Sarantis, D.; Salvador-Ullauri, L. Generative Artificial Intelligence and Web Accessibility: Towards an Inclusive and Sustainable Future. Emerg. Sci. J. 2024, 8, 1602–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novac, O.C.; Madar, D.E.; Novac, C.M.; Bujdosó, G.; Oproescu, M.; Gal, T. Comparative study of some applications made in the Angular and Vue. In js frameworks. In Proceedings of the 2021 16th International Conference on Engineering of Modern Electric Systems (EMES). IEEE; 2021; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Geetha, G.; Mittal, M.; Prasad, K.M.; Ponsam, J.G. Interpretation and Analysis of Angular Framework. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Power, Energy, Control and Transmission Systems (ICPECTS). IEEE; pp. 1–6.

- Javeed, A. Performance optimization techniques for ReactJS. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Electrical, Computer and Communication Technologies (ICECCT). IEEE; 2019; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Gope, D.; Schlais, D.J.; Lipasti, M.H. Architectural support for server-side PHP processing. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM/IEEE 44th Annual International Symposium on Computer Architecture (ISCA). IEEE; 2017; pp. 507–520. [Google Scholar]

- Bielak, K.; Borek, B.; Plechawska-Wójcik, M. Web application performance analysis using Angular, React and Vue. js frameworks. J. Comput. Sci. Inst. 2022, 23, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, A.; Zhao, S.; Chen, H.; Li, Q.; Qin, Y.; Sun, R.; Zhou, X.; Wang, E.; Dong, X. Better Zero-Shot Reasoning with Role-Play Prompting. In Proceedings of the 2024 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (Volume 1: Long Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics; 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhuliawala, S.; Komeili, M.; Xu, J.; Raileanu, R.; Li, X.; Celikyilmaz, A.; Weston, J.E. Chain-of-Verification Reduces Hallucination in Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the ICLR 2024 Workshop on Reliable and Responsible Foundation Models.

- Sejnowski, T.J. Large language models and the reverse turing test. Neural computation 2023, 35, 309–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, L.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Hou, L.; Nie, L.; Li, J. A survey of knowledge enhanced pre-trained language models. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, B.; Ross, H.; Sulem, E.; Veyseh, A.P.B.; Nguyen, T.H.; Sainz, O.; Agirre, E.; Heintz, I.; Roth, D. Recent advances in natural language processing via large pre-trained language models: A survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 56, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirunavukarasu, A.J.; Ting, D.S.J.; Elangovan, K.; Gutierrez, L.; Tan, T.F.; Ting, D.S.W. Large language models in medicine. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 1930–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alqahtani, T.; Badreldin, H.A.; Alrashed, M.; Alshaya, A.I.; Alghamdi, S.S.; bin Saleh, K.; Alowais, S.A.; Alshaya, O.A.; Rahman, I.; Al Yami, M.S.; et al. The emergent role of artificial intelligence, natural learning processing, and large language models in higher education and research. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenAI. GPT-4o. https://openai.com/index/hello-gpt-4o/, 2024. Accessed February 28, 2025.

- OpenAI. o3-mini. https://openai.com/index/openai-o3-mini/, 2022. Accessed February 28, 2025.

- Google. Gemini 2.0 Flash. https://ai.google.dev/models/gemini, 2024. Accessed February 28, 2025.

- Thoppilan, R.; De Freitas, D.; Hall, J.; Shazeer, N.; Kulshreshtha, A.; Cheng, H.T.; Jin, A.; Bos, T.; Baker, L.; Du, Y.; et al. Lamda: Language models for dialog applications. arXiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhery, A.; Narang, S.; Devlin, J.; Bosma, M.; Mishra, G.; Roberts, A.; Barham, P.; Chung, H.W.; Sutton, C.; Gehrmann, S.; et al. Palm: Scaling language modeling with pathways. arXiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nozza, D.; Bianchi, F.; Hovy, D.; et al. Pipelines for social bias testing of large language models. Proceedings of BigScience Episode# 5–Workshop on Challenges & Perspectives in Creating Large Language Models. Association for Computational Linguistics; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kasneci, E.; Seßler, K.; Küchemann, S.; Bannert, M.; Dementieva, D.; Fischer, F.; Gasser, U.; Groh, G.; Günnemann, S.; Hüllermeier, E.; et al. ChatGPT for good? On opportunities and challenges of large language models for education. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2023, 103, 102274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazar, J. Due Process and Primary Jurisdiction Doctrine: A Threat to Accessibility Research and Practice? In Proceedings of the 20th international ACM SIGACCESS conference on computers and accessibility; 2018; pp. 404–406. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).