4.1. Experimental Scenarios

To evaluate the robustness and effectiveness of the proposed M3-DynaFIPS framework—a Multidimensional Metrics Framework for Evaluating Dynamic Fingerprint-Based Indoor Positioning Systems—we conduct a comprehensive performance assessment across three diverse real-world indoor environments. Specifically, the proposed error-weighted probabilistic fusion method is evaluated through a comparative analysis in the following settings: (i) an office environment at the University of Electronic Science and Technology of China (UESTC), (ii) an indoor parking facility at Huawei, and (iii) a university library at Universitat Jaume I in Spain. These distinct scenarios represent varying spatial layouts and signal conditions, allowing us to rigorously assess the generalizability, stability, and adaptability of the proposed localization framework.

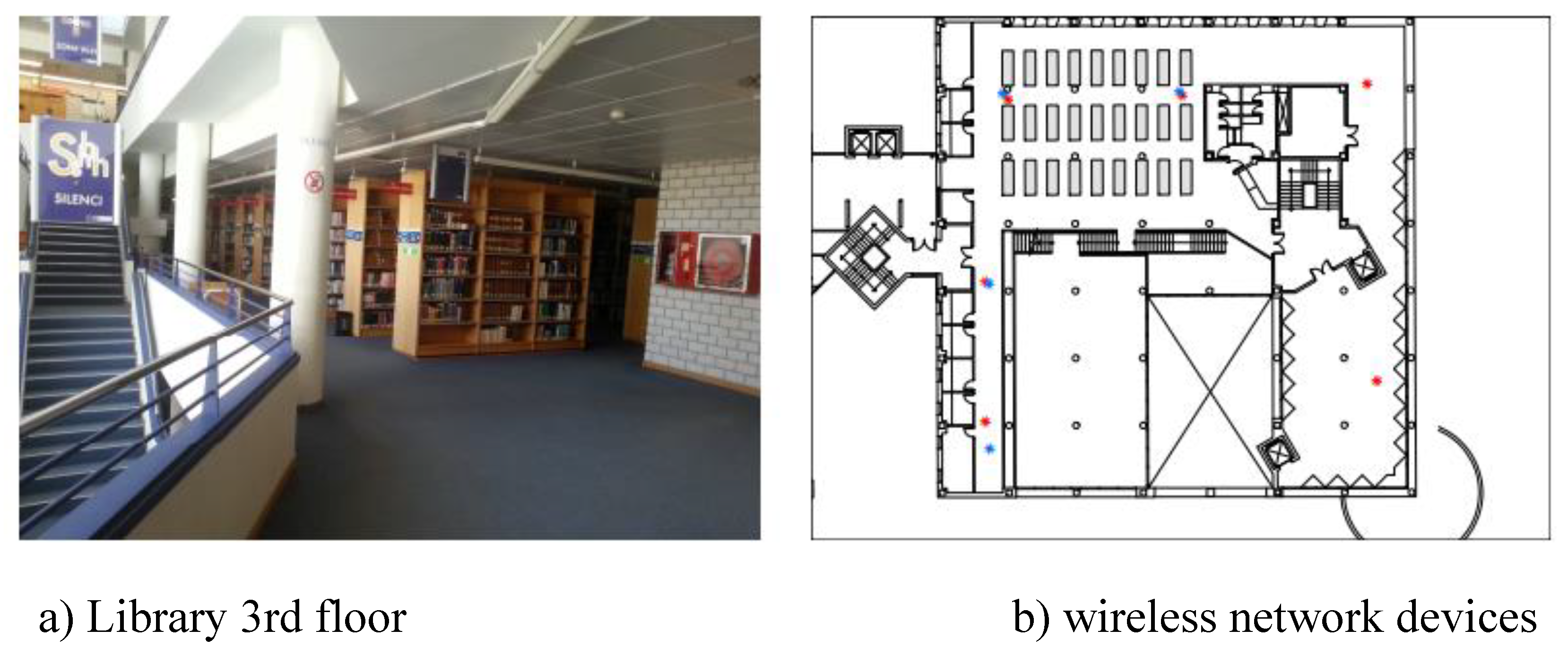

A. Library

The study was conducted on the 3rd and 5th floors of the Universitat Jaume I library in Spain, covering approximately 308.4 m² (

Figure 1a). Over 25 months, Wi-Fi fingerprint data were collected using a Samsung Galaxy S3 smartphone, resulting in a dataset comprising 620 access points (APs) across 106 grid points (

Figure 1b). During the first month, 15 offline and 5 online databases were recorded; in the following months, 1 offline and 5 online databases were collected monthly. Four offline databases from the first month were used as the reference training set, while online datasets from subsequent months served as testing samples to assess signal variability over time. To analyze long-term performance, one offline dataset per month was selected as training data and evaluated against five testing samples from randomly selected months. This approach enabled assessment of signal fluctuation and generalization in dynamic indoor environments. The complete dataset is publicly available on Zenodo [

48]:

https://zenodo.org/record/1066041. A summary of the dataset is provided in

Table 1, supporting the development of the proposed PCA-based RSS fingerprinting localization framework.

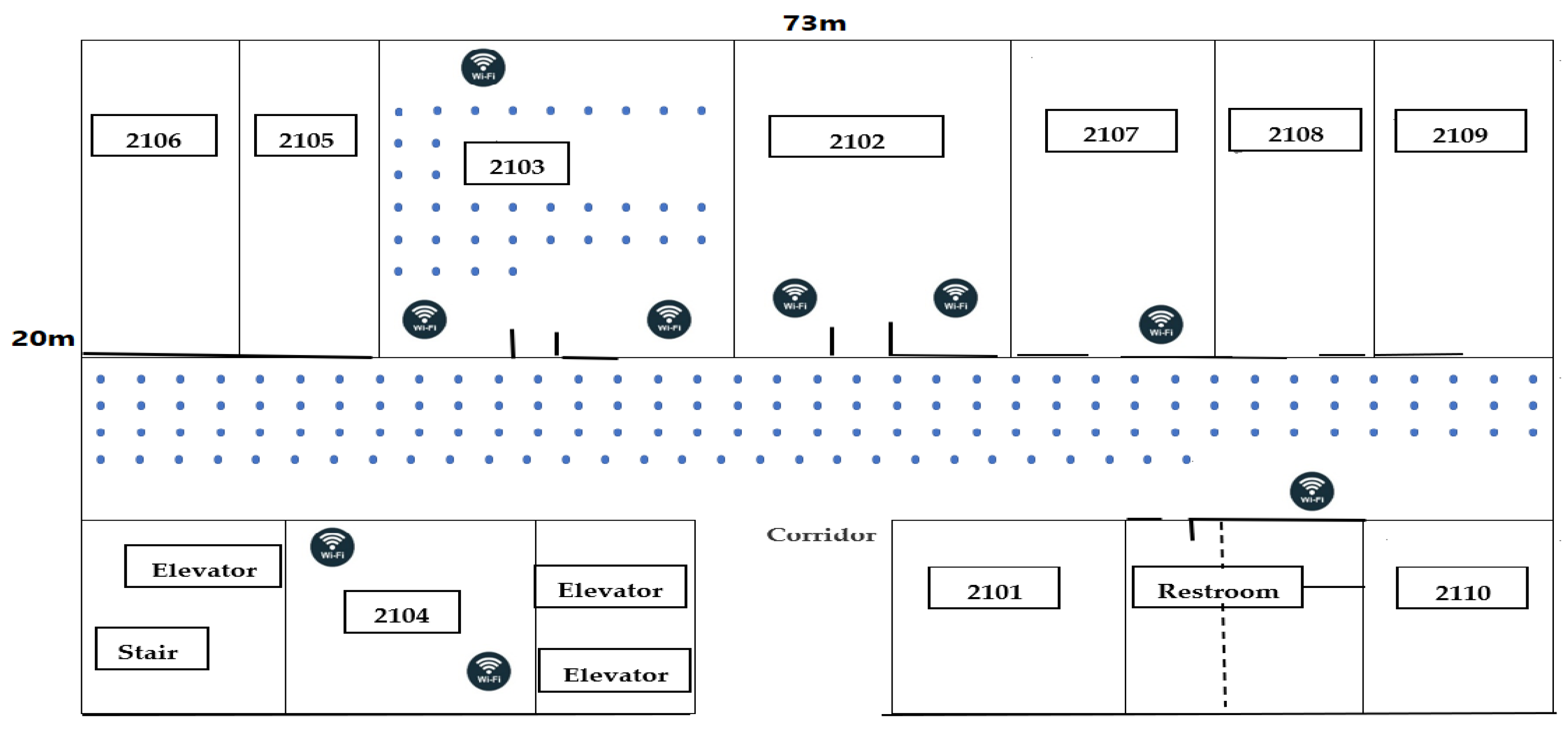

B. Office

To validate the proposed approach under realistic and varying indoor environmental conditions, a real-world office experiment was conducted at the University of Electronic Science and Technology of China (UESTC), specifically on the 21st floor of the Innovation Building, as depicted in

Figure 2. The experimental site covers an area of approximately 1,460 m² and is systematically partitioned into 175 reference points (RPs). To ensure reliable and consistent signal coverage, nine Wi-Fi access points (APs) were strategically installed, with each RP guaranteed to receive signals from at least three APs.

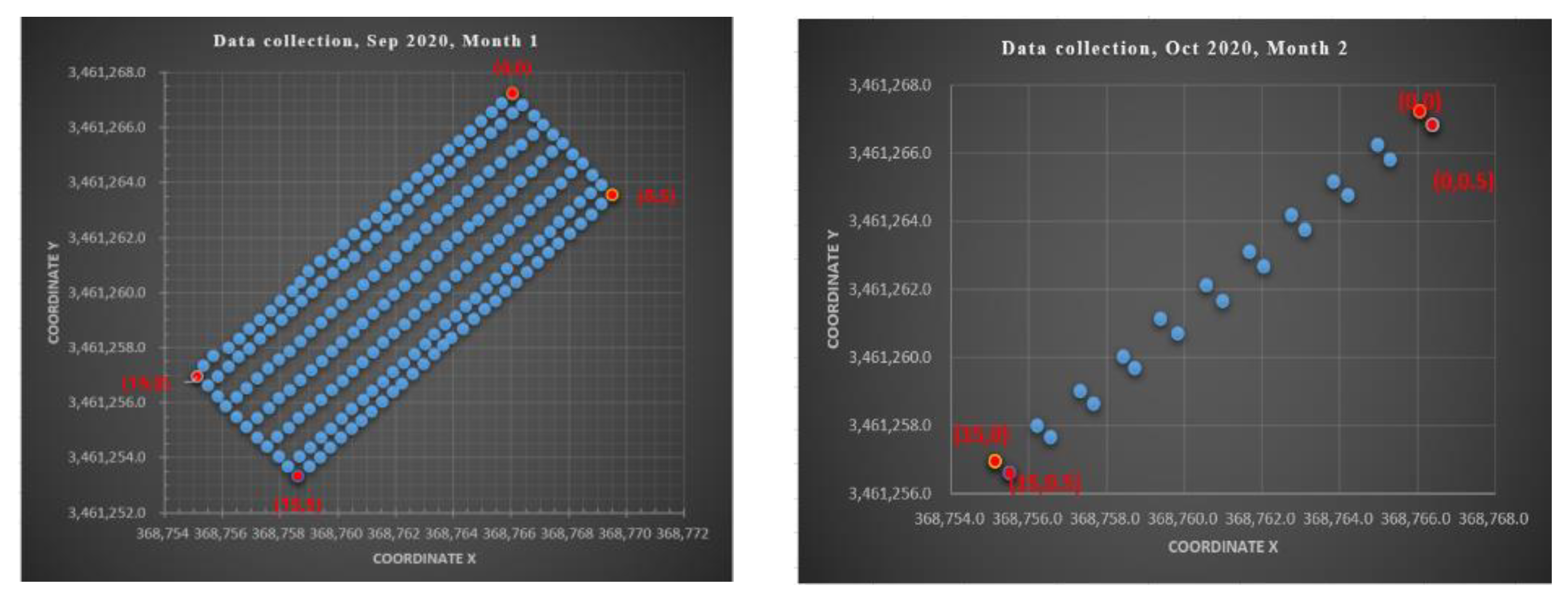

C. Indoor Parking

The experiments were conducted at Huawei within a 75 m² indoor environment, where 225 and 110 RPs were uniformly distributed with a minimum spacing of 0.5 meters, as shown in

Figure 2. Two distinct data collection campaigns were carried out: the first in September 2020 and the second in October 2020. During the first phase, data were collected on eight separate days, resulting in eight measurement sets, while the second phase comprised five measurements across five distinct days. In this study, the second-phase dataset—comprising channel state information (CSI) measurements collected over five consecutive days—was used, with the data fused to construct a robust and representative fingerprint database for performance evaluation. The CSI was captured using a setup that included four base stations and one transmitter, with all data collected via a location server. Notably, the number of RPs captured per day varied across the two periods, leading to an inherent imbalance in the dataset. This variability introduces potential bias, which is explicitly addressed in the subsequent analysis. The spatial layouts and environmental configurations of the experimental scenarios are depicted in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3.

Table 1 [

49,

50,

51] summarizes the key characteristics of the three datasets used to evaluate the performance of the proposed dynamic fingerprint-based indoor positioning algorithms. These datasets were collected across diverse indoor environments—library, office, and indoor parking—with variations in area size, number of RPs, APs, user equipment (UEs), and extracted features.

4.2. Comparative Analysis of Methods

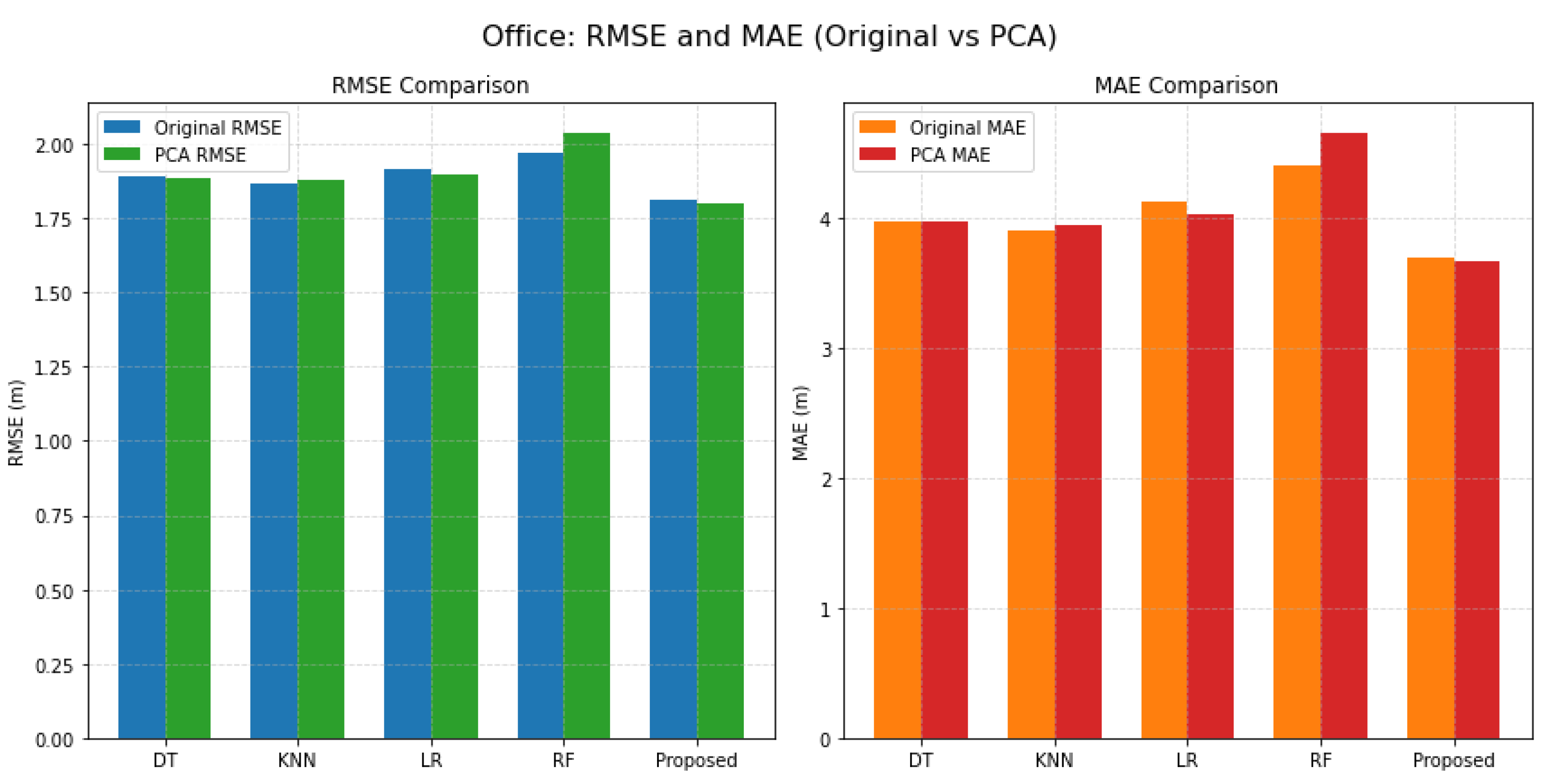

To comprehensively assess the effectiveness of the proposed error-weighted probabilistic fusion approach, a comparative performance analysis was conducted across three distinct indoor environments: an office setting at UESTC, an indoor parking site at Huawei, and a university library at Universitat Jaume I in Spain. The evaluation considered two key dimensions: (i) the use of original feature representations, and (ii) the application of PCA as a dimensionality reduction technique. The analysis employed two complementary accuracy metrics—RMSE and MAE—which align with the Metric dimension of the M3-DynaFIPS framework for multidimensional performance evaluation.

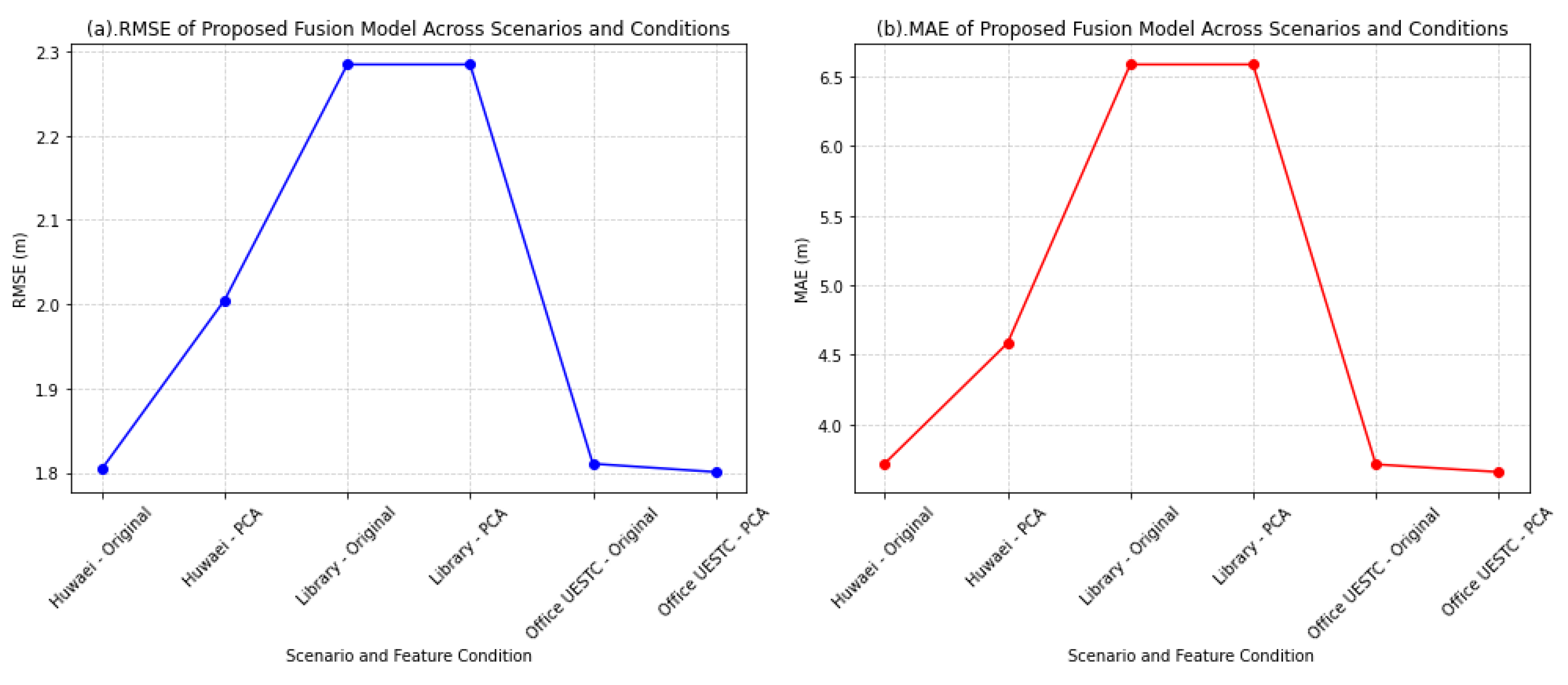

As shown in

Table 2 and

Table 3, the proposed fusion model consistently outperforms individual classifiers (DT, KNN, LR, and RF) across all environments, both in terms of RMSE and MAE. For instance, in the Office dataset, the proposed method achieved the lowest RMSE (1.810 m) and MAE (3.689 m) using original features, outperforming the next best baseline (KNN) by notable margins. Similarly, in the Huawei indoor parking site—characterized by high signal variability due to structural interference—the proposed model demonstrated superior localization performance (RMSE: 1.804 m, MAE: 3.718 m), highlighting its adaptability in dynamic environments. Even in the Library environment, where signal reflection and occlusion effects are more pronounced, the proposed method maintained its relative advantage over all other models (RMSE: 2.272 m, MAE: 6.454 m).

After applying PCA, while a general trend of marginal degradation in performance was observed—particularly in MAE across environments—the proposed model retained its top ranking. This suggests that, although PCA reduces dimensionality and computational complexity, it may also eliminate subtle but discriminative spatial features that are vital for precise localization. Nonetheless, the fusion model's resilience to such information loss illustrates its robustness and generalization capability. These findings corroborate the principles of the M3-DynaFIPS framework, specifically its emphasis on evaluating fingerprint-based indoor positioning systems through multiple performance metrics, under variable environmental conditions, and across different feature representations. The superior performance of the proposed method in all cases underscores its practical viability and effectiveness as a dynamic, adaptive localization solution in real-world indoor scenarios.

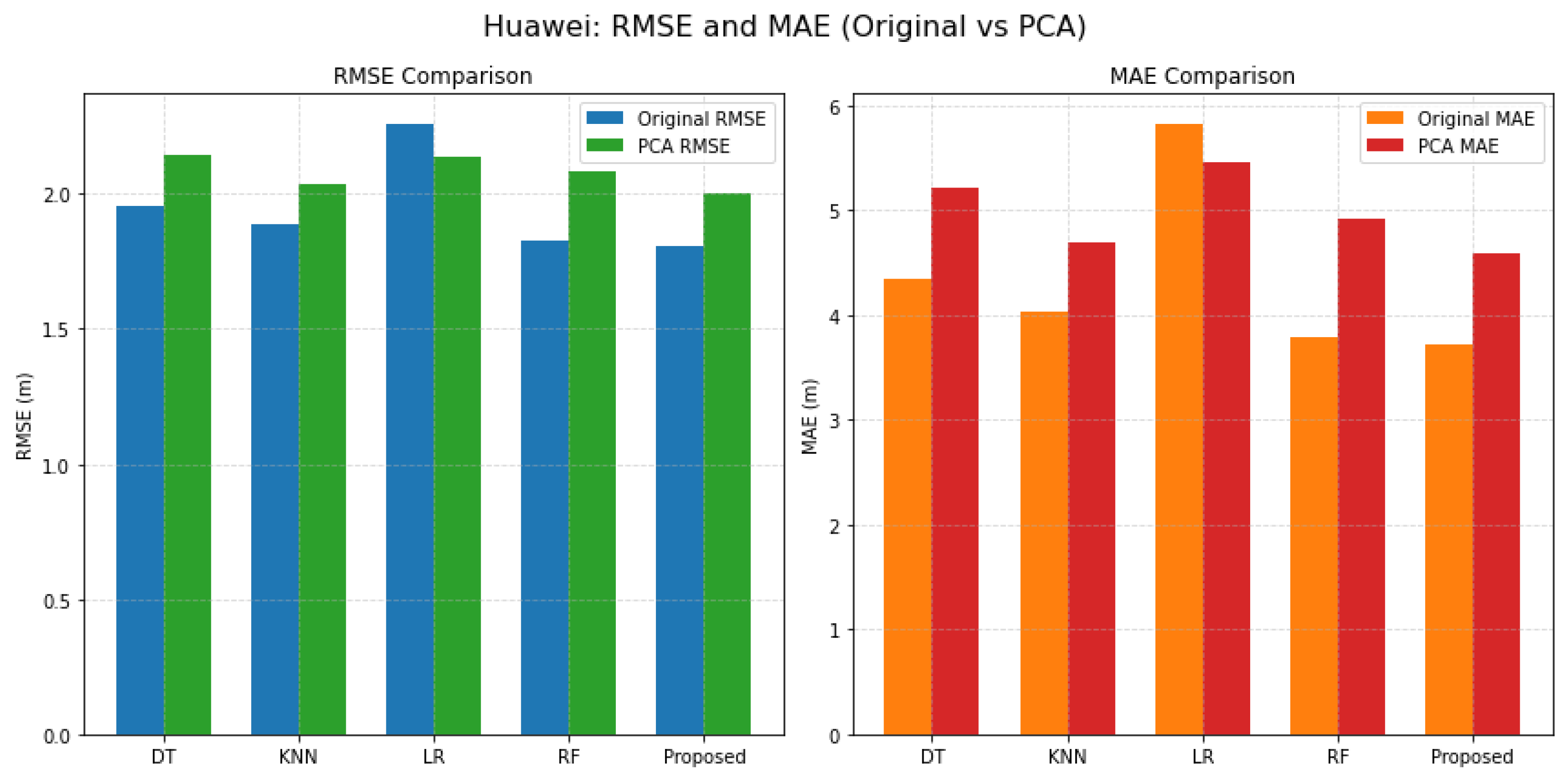

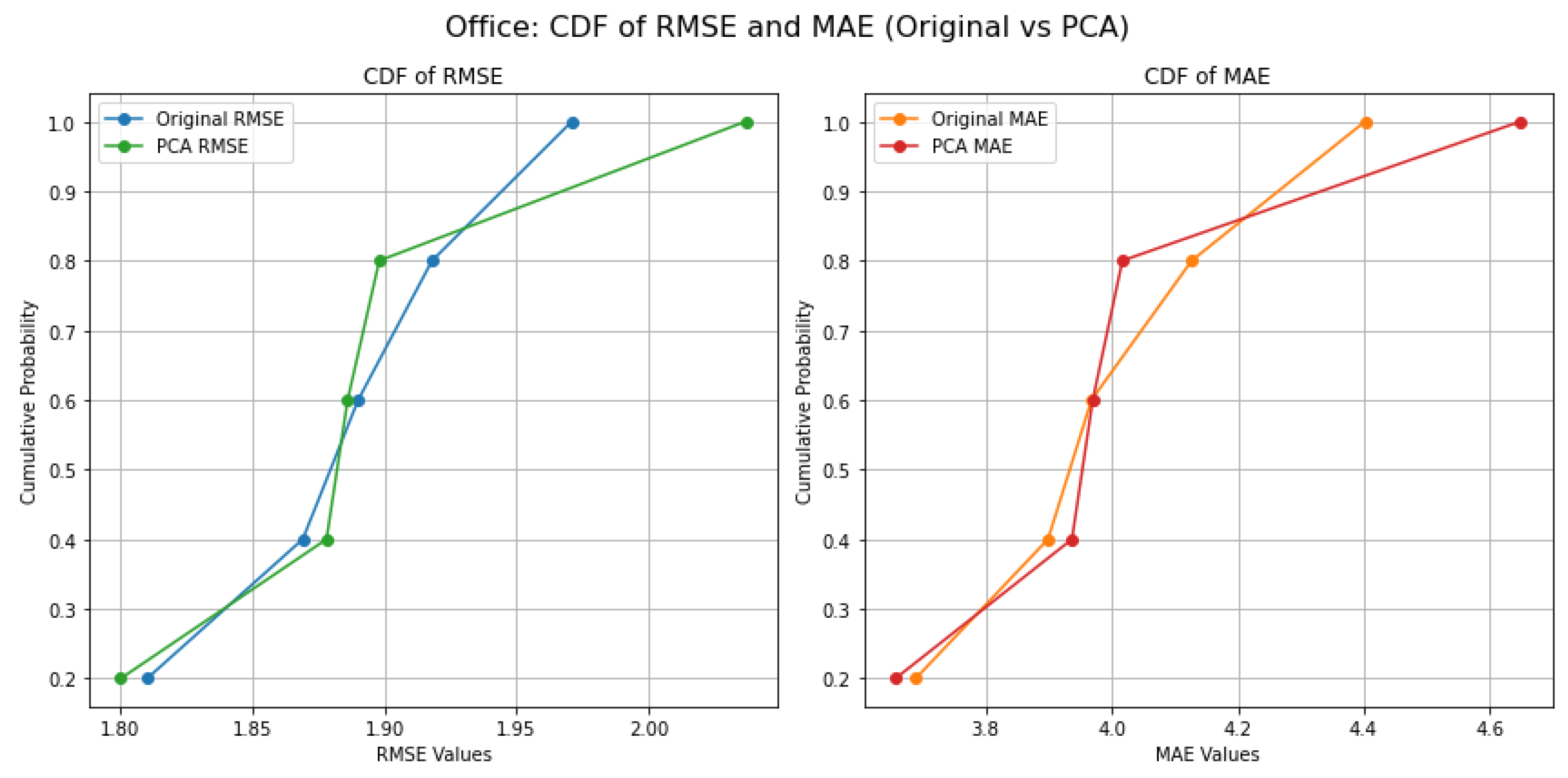

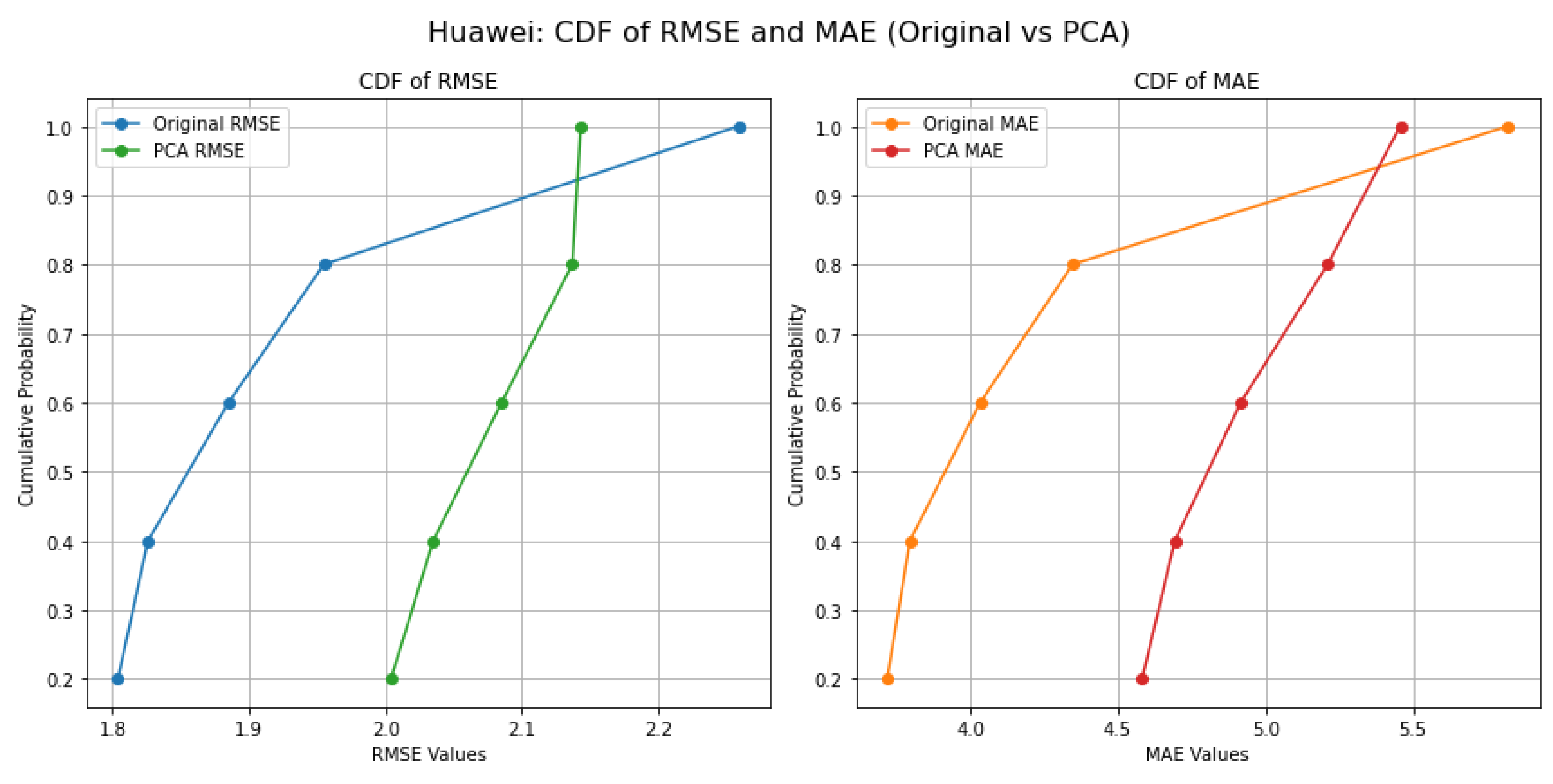

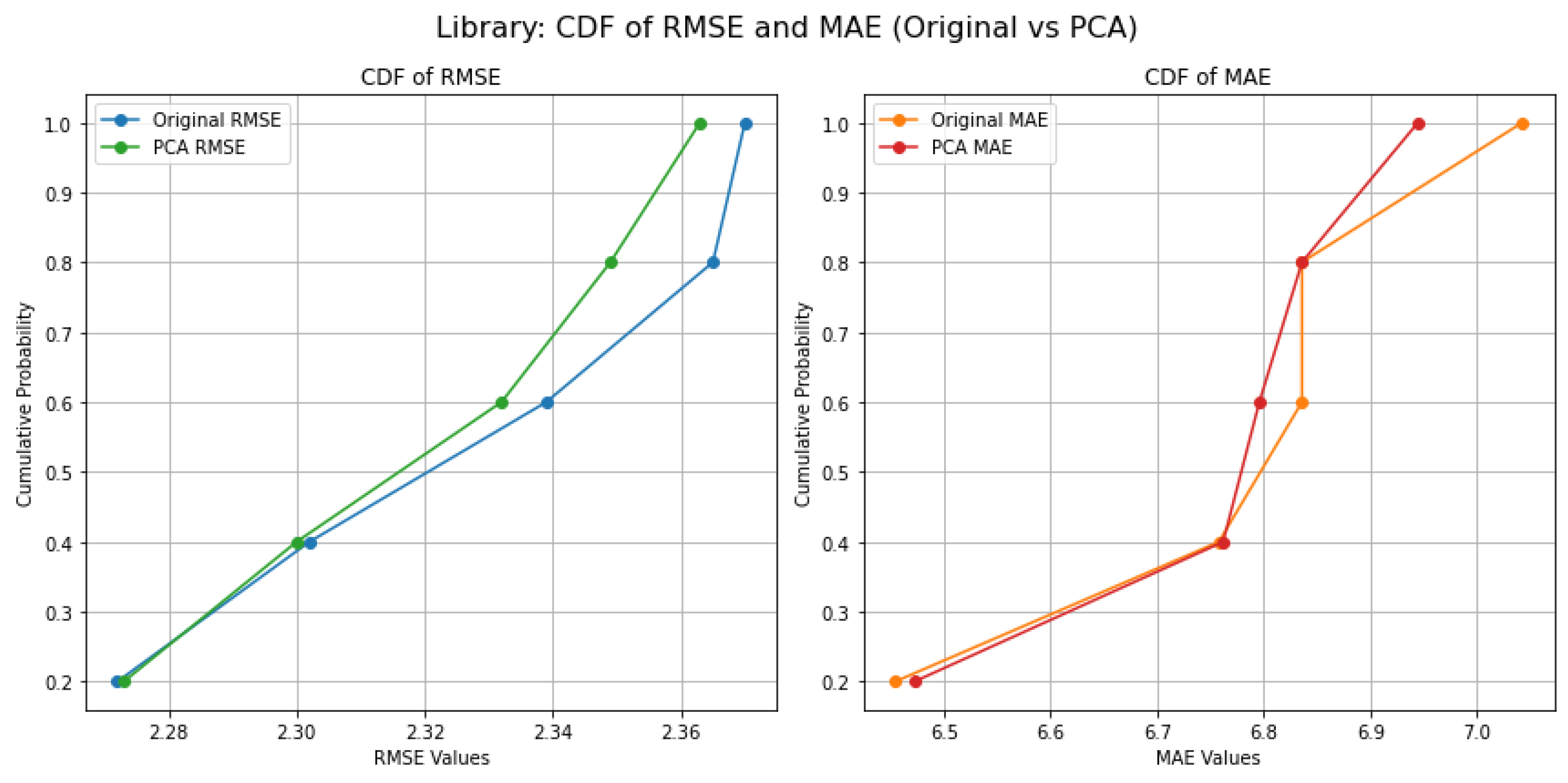

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 illustrate the comparative performance of five localization models—DT, KNN, LR, RF, and the proposed error-weighted fusion approach—across three distinct indoor environments: an academic office, an indoor parking facility, and a university library. The metrics used for evaluation include RMSE and MAE, with results presented both before and after the application of PCA.

The figure reveals several key insights. First, the proposed fusion model consistently yields the lowest error values across all scenarios, underscoring its robustness and adaptability in diverse signal environments. Second, while PCA offers dimensionality reduction benefits, its impact on localization accuracy is mixed [

52]—resulting in slight performance degradation in most cases, particularly in MAE. This indicates that although PCA preserves major variance components, it may also discard subtle signal characteristics critical for precise localization. Furthermore, the Library environment demonstrates higher error magnitudes overall, likely due to increased signal reflections and dynamic obstructions, thereby validating the environmental sensitivity dimension of the M3-DynaFIPS evaluation framework. In summary, the figure supports the conclusion that fusion-based learning, when paired with original high-dimensional feature representations, provides a more reliable and accurate localization strategy in heterogeneous indoor settings.

Figure 4 presents a comparative analysis of RMSE and MAE for the Office environment using two feature sets: Original and PCA. The bar charts illustrate the performance of five classifiers (DT, KNN, LR, RF, and Proposed Method) in predicting the target variable. The Original feature set is represented in blue for RMSE and orange for MAE, while PCA features are shown in green for RMSE and red for MAE. The results indicate that the Proposed Method consistently outperforms other classifiers, particularly in RMSE, suggesting enhanced predictive accuracy with PCA preprocessing.

Figure 5 compares RMSE and MAE for the Huawei environment, highlighting the efficacy of Original and PCA-derived features across five classifiers. The bar charts reveal distinct performance metrics, with original features (blue for RMSE, orange for MAE) and PCA features (green for RMSE, red for MAE). The analysis shows that while some classifiers exhibit slight variations in performance, the Proposed Method achieves lower RMSE and MAE values, indicating improved model reliability and accuracy when utilizing PCA features. This suggests that dimensionality reduction techniques may enhance predictive modeling in this specific context.

In

Figure 6, the RMSE and MAE for the Library environment are compared using Original and PCA features. The bar charts differentiate between the performance of five classifiers, with original features indicated in blue and orange, and PCA features in green and red. The results demonstrate a notable improvement in predictive accuracy for the Proposed Method, particularly in RMSE. This emphasizes the role of PCA in reducing feature dimensionality and enhancing model performance, making it a valuable approach for datasets with complex interactions among features.

Figure 7 illustrates that the Cumulative Distribution Function (CDF) for RMSE in the Office environment indicates that approximately 70% of predictions using PCA features achieve an RMSE below 1.9, compared to only 50% for original features. Similarly, for MAE, around 65% of predictions with PCA fall below 4.0, whereas only 40% do so with original features. This significant shift underscores the effectiveness of PCA in enhancing model accuracy and reliability in the Office setting.

Figure 8 illustrates that the CDF for RMSE and MAE in the Huawei environment demonstrates that about 60% of predictions using PCA features yield an RMSE below 2.0, compared to just 35% for original features. For MAE, approximately 55% of PCA predictions are below 5.0, while only 30% of original predictions reach this threshold. These findings highlight the substantial improvement in predictive performance when applying PCA, reflecting the importance of dimensionality reduction in this context.

Figure 9 illustrates that the CDF analysis for the library environment reveals that nearly 75% of predictions using PCA features attain an RMSE below 2.4, contrasted with only 50% of original predictions. For MAE, around 70% of PCA results are below 7.0, compared to 45% for original features. This marked enhancement in error reduction demonstrates the significant benefits of using PCA for improving model accuracy in complex datasets like those found in the library environment.

4.4. Computational Time Analysis

In this section, we analyze the computational complexity of our proposed algorithm for Wi-Fi Fingerprint-Based Indoor Location Estimation. We specifically focus on the utilization of various data reduction techniques, namely mean signal values, functional discriminant analysis, correlation analysis and principal component analysis, to extract feature spaces. The algorithms under study were executed on a laptop computer equipped with an AMD Ryzen 3 3200U CPU (2.60 GHz) and 16 GB of RAM. The complexity of an algorithm is primarily assessed based on two factors: time complexity and space complexity. The provided tables (

Table 4 and

Table 5) present the computational time and localization error for various classifiers (DT, KNN, LR, RF) and a proposed fusion model in an "Indoor setting: Office: UESTC" dataset. The analysis covers both original features (

Table 3) and features after PCA application (

Table 4), evaluating training/testing times (seconds), RMSE, and MAE (meters).

As detailed in

Table 3, for the original feature set, the DT classifier exhibited extremely fast training (0.0194 seconds) and testing (0.1555 seconds) times. Its RMSE was 1.890248 m and MAE was 3.9680 m. The KNN classifier, while showing relatively longer training (12.6537 seconds) and testing (1.6511 seconds) times compared to DT and LR, still maintained reasonable efficiency. KNN achieved an RMSE of 1.869913 m and an MAE of 3.8991 m. LR demonstrated fast training (4.0823 seconds) and exceptionally fast testing (0.0040 seconds), with an RMSE of 1.918150 m and MAE of 4.1272 m. The RF classifier was notably efficient in both training (0.1985 seconds) and testing (0.0094 seconds). Its RMSE was 1.971958 m and MAE was 4.3996 m. Among individual classifiers, KNN achieved the lowest RMSE, while KNN also had the lowest MAE. The proposed fusion model consistently achieved superior accuracy, yielding the lowest RMSE of 1.810613 m and MAE of 3.7122 m, with a highly efficient prediction time of 0.0040 seconds.

Following the application of PCA, as presented in

Table 4, significant improvements in computational efficiency were observed across most classifiers. The DT classifier maintained its extremely fast performance, with training time slightly reduced to 0.0132 seconds and testing time to 0.1060 seconds. Its RMSE improved slightly to 1.8867 m, and MAE to 3.9704 m. The KNN classifier experienced a slight increase in training time to 13.2847 seconds, but its testing time remained comparable at 1.4232 seconds. KNN's RMSE slightly improved to 1.8782 m, and MAE to 3.9376 m. LR saw its training time notably reduced to 4.2626 seconds, while testing time remained exceptionally fast at 0.0030 seconds. Its RMSE slightly improved to 1.8983 m, and MAE to 4.0172 m. The RF classifier also saw a reduction in training time to 0.4475 seconds, and its testing time increased to 0.0102 seconds. RF's RMSE was 2.0370 m, and MAE was 4.6490 m. Consistent with the original feature analysis, the proposed fusion model continued to demonstrate the best overall performance in terms of localization error, achieving the lowest RMSE of 1.8008 m and MAE of 3.6572 m, with an exceptionally fast prediction time of 0.0040 seconds.

This analysis for the "Indoor setting: Office: UESTC" dataset reveals that PCA effectively optimized the computational efficiency for most classifiers, particularly reducing the training times for DT, LR, and RF. Interestingly, KNN's training time slightly increased after PCA, which could be due to the specific characteristics of the PCA transformation interacting with KNN's distance calculations. Despite these varied individual impacts, all individual classifiers maintained competitive localization errors. Critically, the proposed fusion model consistently achieved the lowest localization errors (both RMSE and MAE) in both scenarios (original and PCA-reduced features), as clearly depicted in

Table 3 and

Table 4. Its prediction time remained highly efficient, making it an ideal choice for real-time indoor localization applications where both accuracy and speed are paramount. The slight improvements in RMSE and MAE for the fusion model after PCA suggest that the dimensionality reduction, while potentially altering individual classifier dynamics, contributed to a more optimized feature representation for the ensemble, further solidifying its superior performance.

The tables provided (

Table 6 and

Table 7) detail the computational time and localization error for various classifiers (KNN, SVC, LR, RF, and DT in

Table 7) and a proposed fusion model, specifically for an "Indoor setting: Library" dataset. The analysis is presented for both original features (

Table 6) and after Principal Component Analysis (PCA) application (

Table 7), evaluating training/testing times (seconds), RMSE, and MAE (meters). As shown in

Table 5, when using the original features, the DT classifier exhibited a training time of 0.3916 seconds and a testing time of 0.0040 seconds, with an RMSE of 2.3866 m and MAE of 7.0434 m. The KNN had an extremely fast training time of 0.0010 seconds but a slower testing time of 0.1671 seconds; its RMSE was 2.3491 m and MAE was 6.8361 m. LR showed a training time of 2.0389 seconds and a very fast testing time of 0.0030 seconds, achieving an RMSE of 2.3327 m and MAE of 6.7628 m. The RF classifier, while requiring the longest training time among individual classifiers at 4.6775 seconds, had a testing time of 0.1270 seconds and demonstrated the lowest individual RMSE of 2.3275 m and MAE of 6.7584 m. Crucially, the Proposed Fusion Model achieved the lowest overall localization errors, with an RMSE of 2.2845 m and an MAE of 6.5865 m, and a highly efficient prediction time of 0.0060 seconds, underscoring the benefits of an ensemble approach.

Following the application of PCA, as presented in

Table 7, some distinct shifts in performance were observed. The DT classifier, which was not explicitly listed in

Table 6, appears in

Table 7 with a training time of 0.5304 seconds and a testing time of 0.0030 seconds. Its RMSE was 2.3866 m and MAE 7.0434 m. It's noteworthy that these error metrics are identical to those of KNN in

Table 6, which could suggest an inconsistency in table labeling or data. For KNN in

Table 7, training time significantly reduced to 0.0030 seconds, but its testing time increased to 0.4312 seconds. Its RMSE and MAE appear to be 2.3491 m and 6.8361 m, matching the KNN results from

Table 6. For LR, training time slightly increased to 2.2078 seconds, while testing time remained fast at 0.0030 seconds, with consistent RMSE and MAE values. RF also saw an increase in training time to 5.7338 seconds and a slight increase in testing time to 0.1369 seconds, while its error metrics remained consistent with its performance on original features. Consistent with its performance on original features, the proposed fusion model continued to provide the most accurate predictions, yielding an RMSE of 2.2845 m and MAE of 6.5865 m, with a slightly increased prediction time of 0.0070 seconds.

The analysis for the "Indoor setting: Library" dataset highlights a consistent trend where the proposed fusion model consistently delivers superior localization accuracy (lowest RMSE and MAE) across both the original and PCA-reduced feature sets, as evident in both

Table 6 and

Table 6. This robust performance underscores the efficacy of ensemble learning in improving predictive precision regardless of the underlying feature representation. While PCA was applied with the aim of optimizing computational efficiency, its impact varied. For some classifiers (e.g., LR and RF), training times unexpectedly increased after PCA (comparing

Table 6 and

Table 7), suggesting that the principal components might have introduced new computational complexities for these algorithms, or that the original feature space was already sufficiently low-dimensional. Conversely, KNN's training time remained minimal, but its testing time unexpectedly increased post-PCA in this specific setting. Despite these individual classifier variations, the fusion model consistently maintained efficient prediction times, making it a practical choice for real-time indoor localization applications. The minor discrepancies in classifier identification and error values across the two tables for the same indoor setting warrant careful review, but the overarching conclusion regarding the fusion model's superior accuracy remains consistent.

Experimental results provided in

Table 8 and Table 9 detail the computational time and localization error for various classifiers and a proposed fusion model, both with original features and after PCA application for an Indoor Parking: Huawei dataset. The performance is evaluated using training and testing times (in seconds) and localization error metrics (RMSE and MAE in meters). For the original feature set (

Table 8), the DT classifier exhibited a significantly high training time of 980.1522 seconds, but a very fast testing time of 0.0940 seconds. Its RMSE was 1.9551 m, and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) was 4.3474 m. The KNN classifier showed remarkably fast training (0.0923 seconds) but a considerably slow testing time (125.1278 seconds), characteristic of lazy learning. KNN's RMSE was 1.8856 m and MAE was 4.0339 m. LR and RF classifiers had moderate training times (199.2367 and 182.9394 seconds, respectively) and efficient testing times (0.2043 and 0.2492 seconds). Among individual classifiers, RF demonstrated the best performance with an RMSE of 1.8269 m and MAE of 3.7951 m. The proposed fusion model significantly outperformed all individual classifiers in terms of accuracy, achieving the lowest RMSE of 1.8043 m and MAE of 3.7186 m, with a very efficient prediction time of 0.1024 seconds.

The application of PCA (Table 9) for dimensionality reduction led to substantial changes in computational times. For DT, training time drastically reduced to 21.6870 seconds, and testing time to 0.0263 seconds. Its RMSE became 2.1431 m and MAE 5.2113 m. KNN's training time remained minimal at 0.0086 seconds, and its testing time saw a significant reduction to 10.3623 seconds. KNN's RMSE was 2.0354 m and MAE 4.6934 m. LR and RF also experienced substantial decreases in training times (7.8969 and 22.1852 seconds, respectively) and remained efficient in testing (0.0224 and 0.1427 seconds). Among individual classifiers, RF again achieved the lowest RMSE of 2.0857 m and MAE of 4.9166 m after PCA. The Proposed Fusion Model consistently maintained its superior performance, yielding the lowest RMSE of 2.0048 m and MAE of 4.5828 m, with a highly efficient prediction time of 0.0504 seconds.

This analysis clearly demonstrates the trade-offs between computational efficiency and localization accuracy. The original feature set, while yielding slightly better individual classifier performance in terms of error (e.g., lower RMSE for RF), came with significantly higher training times for most models, particularly DT. The application of PCA dramatically reduced training and, notably, KNN testing times across all classifiers, indicating its effectiveness in optimizing computational efficiency. However, this reduction in dimensionality generally led to a slight increase in localization errors for individual classifiers. Crucially, the proposed fusion model consistently emerged as the most robust solution. It not only achieved the lowest localization errors (both RMSE and MAE) in both scenarios (original and PCA-reduced features) but also maintained very efficient prediction times. This highlights the substantial benefits of ensemble learning, as the fusion model effectively mitigates the individual weaknesses of base classifiers and leverages their collective strengths, providing superior and more reliable localization accuracy regardless of the feature set complexity. The reduced prediction time of the fusion model after PCA is particularly noteworthy for real-time applications where computational constraints are critical.

Table 7.

Computational Time and Localization Error Analysis with original features.

Table 7.

Computational Time and Localization Error Analysis with original features.

| Indoor Parking : Huwaei |

Computationl Analysis: Error in meters |

| Classifiers |

Training/Testing (sec) |

RMSE (m) |

Training/Testing (sec) |

MAE (m) |

| DT |

980.1522 (0.0940) |

1.9551 |

978.3586 (0.0519) |

4.3474 |

| KNN |

0.0923 (125.1278) |

1.8856 |

0.0581 (104.1552) |

4.0339 |

| LR |

199.2367 (0.2043) |

2.2591 |

151.3298 (0.1749) |

5.8233 |

| RF |

182.9394 (0.2492) |

1.8269 |

121.6935 (0.2587) |

3.7951 |

| Proposed Fusion Model |

— (0.1024) |

1.8043 |

— (0.0624) |

3.7186 |

Table 8.

Computational Time and Localization Error Analysis after PCA applied.

Table 8.

Computational Time and Localization Error Analysis after PCA applied.

| Indoor Parking : Huwaei |

Computationl Analysis: Error in meters |

| Classifiers |

Training/Testing (sec) |

MAE (m) |

Training/Testing (sec) |

RMSE (m) |

| DT |

21.6870 (0.0263) |

5.2113 |

21.0898 (0.0254) |

2.1431 |

| KNN |

0.0086 (10.3623) |

4.6934 |

0.0150 (12.3805) |

2.0354 |

| LR |

7.8969 (0.0224) |

5.4575 |

9.2242 (0.0371) |

2.1376 |

| RF |

22.1852 (0.1427) |

4.9166 |

21.5566 (0.1845) |

2.0857 |

| Proposed Fusion Model |

— (0.0504) |

4.5828 |

— (0.0570) |

2.0048 |

The provided line graphs in

Figure 10 (a) & (b) visualize the RMSE and MAE performance of the proposed fusion model across three distinct indoor scenarios (Huawei, Library, and Office UESTC), evaluated with both original features and after PCA application.

- (a)

-

RMSE of Proposed Fusion Model Across Scenarios and Conditions

The RMSE graph illustrates the following trends in the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) of the Proposed Fusion Model:

Huawei Scenario: The RMSE for the Huawei dataset increases from approximately 1.80 m with original features to around 2.00 m after PCA. This suggests that for this specific indoor parking environment, the dimensionality reduction performed by PCA led to a slight degradation in the model's ability to precisely estimate location, likely due to the loss of some discriminative information.

Library Scenario: A distinctive plateau is observed for the library dataset, where the RMSE remains constant at approximately 2.28 m for both original features and after PCA. This indicates that for the library environment, PCA did not significantly impact the fusion model's RMSE performance, implying either that the original feature space was already efficiently utilized or that the principal components effectively retained the critical information without introducing further error. This scenario consistently shows the highest RMSE among the three environments.

Office UESTC Scenario: In contrast to Huawei, the Office UESTC dataset shows a slight decrease in RMSE, moving from approximately 1.81 m with original features to around 1.80 m after PCA. This suggests that for this office environment, PCA might have successfully removed noise or irrelevant features, leading to a marginal improvement in the fusion model's RMSE. The Office UESTC scenario consistently demonstrates the lowest RMSE among the three environments.

- (b)

-

MAE of Proposed Fusion Model Across Scenarios and Conditions

The MAE graph reveals similar patterns in the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) of the Proposed Fusion Model:

Huawei Scenario: The MAE for the Huawei dataset also shows an increase from approximately 3.72 m (original) to around 4.58 m (PCA), mirroring the RMSE trend. This reinforces the observation that PCA might have negatively impacted the average absolute error for this environment.

Library Scenario: Similar to RMSE, the MAE for the Library dataset remains constant at approximately 6.59 m for both original and PCA-applied features. This consistent behavior across both RMSE and MAE further emphasizes that PCA did not alter the fusion model's average absolute error in this setting, which is also the scenario with the highest MAE.

Office UESTC Scenario: The MAE for the Office UESTC dataset shows a slight decrease from approximately 3.71 m (original) to around 3.66 m (PCA). This aligns with the RMSE trend, suggesting that PCA contributed to a minor reduction in the average absolute error for this office environment. The Office UESTC scenario generally exhibits the lowest MAE.

The analysis of both RMSE and MAE graphs demonstrates the robust performance of the Proposed Fusion Model across diverse indoor localization environments. However, the impact of PCA as a dimensionality reduction technique on the fusion model's accuracy is scenario-dependent.

For the Huawei dataset, PCA appears to have a detrimental effect on both RMSE and MAE, indicating that the reduced feature set might have lost crucial information, leading to slightly less accurate predictions.

For the Library dataset, PCA has a neutral effect on the fusion model's localization error metrics, suggesting that the dimensionality reduction neither significantly improved nor degraded performance in terms of accuracy. This particular environment consistently presents the highest errors among the three.

For the Office UESTC dataset, PCA leads to a marginal improvement in both RMSE and MAE, implying that it might have helped in filtering out noise or redundant features, thus slightly enhancing the model's predictive capability. This environment consistently achieves the lowest errors.

In conclusion, while the proposed fusion model maintains strong performance across all tested indoor environments, the decision to apply PCA as a preprocessing step for localization error reduction should be made on a per-scenario basis. The results indicate that for optimal accuracy with the fusion model, PCA may be beneficial in certain environments (e.g., Office UESTC), neutral in others (e.g., Library), and potentially detrimental in some (e.g., Huawei), underscoring the importance of empirical evaluation for specific deployment contexts.

Figure 11 illustrates the comparative computational time required for training and testing across five localization models—DT, KNN, LR, RF, and the proposed fusion method—under both RMSE- and MAE-based evaluation metrics, using (a) original features and (b) PCA-reduced features. Each model is assessed for four performance aspects: training time (RMSE), testing time (RMSE), training time (MAE), and testing time (MAE). From

Figure 8(a), using the original feature space, the KNN classifier exhibits the highest training and testing times, with training times reaching 12.65 seconds (RMSE) and 13.07 seconds (MAE), and testing times at 1.65 seconds (RMSE) and 1.54 seconds (MAE). This is due to the instance-based nature of KNN, where distance calculations are deferred until inference. The Random Forest model has relatively low training and testing times—0.1985 seconds (RMSE) and 0.0094 seconds (RMSE), respectively—making it more suitable for real-time settings. The proposed fusion model demonstrates negligible training time (~0 sec) and low inference time (~0.004 to 0.0052 seconds) under both metrics, affirming its computational efficiency.

In

Figure 11 (b), after applying PCA for dimensionality reduction, training and testing times are generally reduced across all models, particularly for Decision Tree and Logistic Regression. For instance, DT's training time decreased from 0.0194 to 0.0132 seconds, and its testing time dropped from 0.1555 to 0.1060 seconds under the RMSE criterion. However, PCA introduced a slight increase in training overhead for Random Forest (from 0.1985 to 0.4475 seconds) and testing time for KNN remained relatively high due to persistent neighborhood computations even in reduced feature space. Notably, the proposed fusion method maintained its advantage across both feature configurations, with consistently minimal training and inference costs, unaffected by the PCA transformation. This reaffirms its suitability for deployment in real-time or resource-constrained indoor localization systems where computational efficiency is critical.

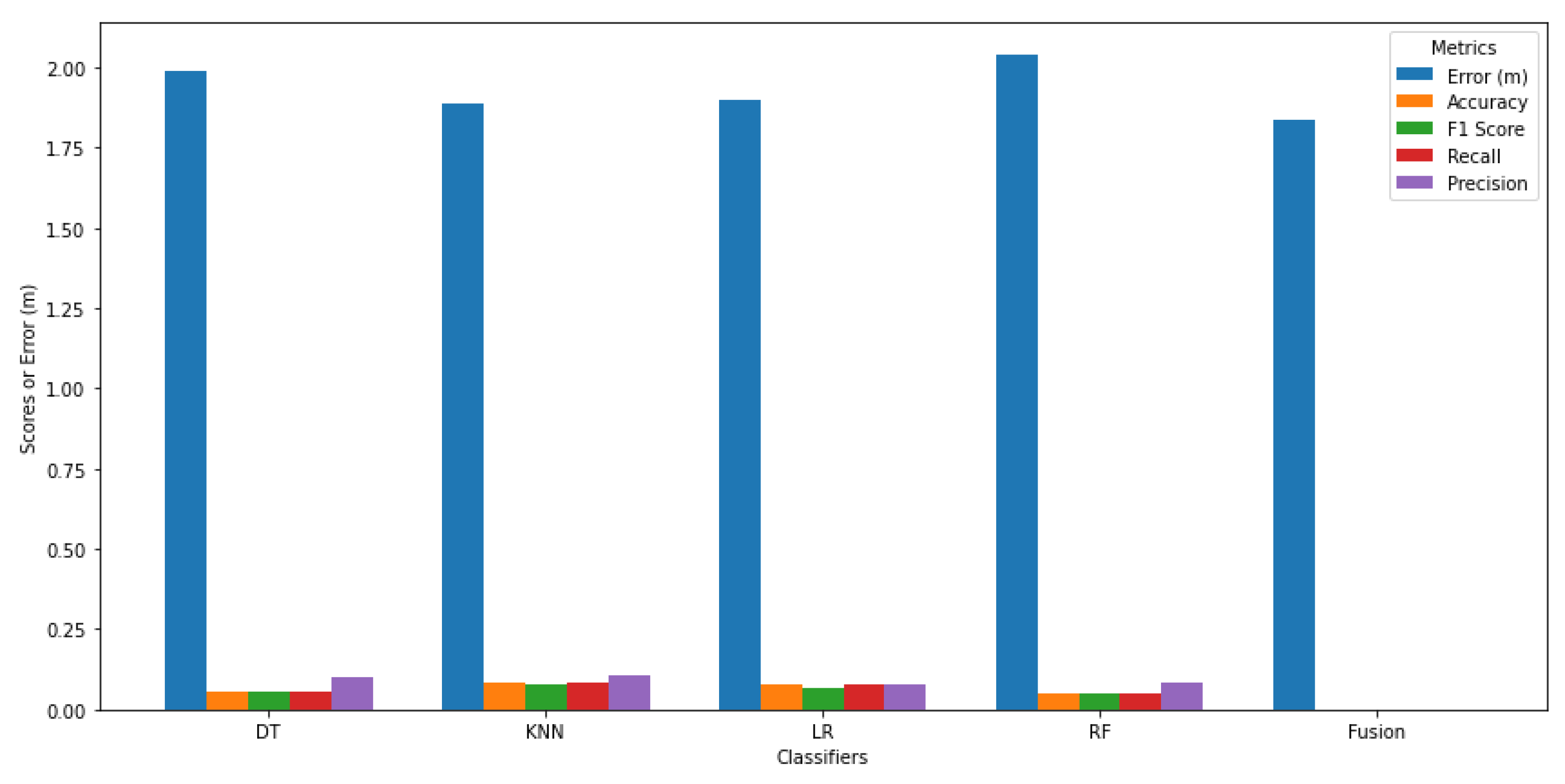

Figure 12 illustrates the comparative performance metrics of four classifiers— DT, KNN, LR, RF—and a Fusion model for the office environment. The grouped bar chart showcases each classifier's Accuracy, F1 Score, Recall, Precision, and Error in meters. From the figure, it is evident that all classifiers exhibit low performance across the metrics, with DT achieving the highest Accuracy at 0.0554 and Precision at 0.0982. KNN follows closely with slightly better performance in F1 Score and Recall. The RF classifier shows the poorest results overall, with an Accuracy of only 0.0503. The Fusion model, intended to combine the strengths of the individual classifiers, fails to improve predictive performance, resulting in an Accuracy of 0.0000 and highlighting the limitations of the approach in this specific context. The Error metrics indicate that all classifiers struggle with localization accuracy, with the Fusion model yielding a minimal error of 1.834229m, which, despite being the lowest, does not translate into effective classification. This analysis underscores the limitations of relying solely on traditional localization error metrics such as RMSE or MAE for performance evaluation. Instead, a multidimensional assessment framework incorporating classification-based metrics—such as Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1 Score—provides a more comprehensive understanding of model behavior and predictive reliability. These metrics reveal critical performance variations across models and conditions, underscoring the need for continued optimization and exploration of alternative algorithms to enhance robustness and generalizability in dynamic indoor environments.

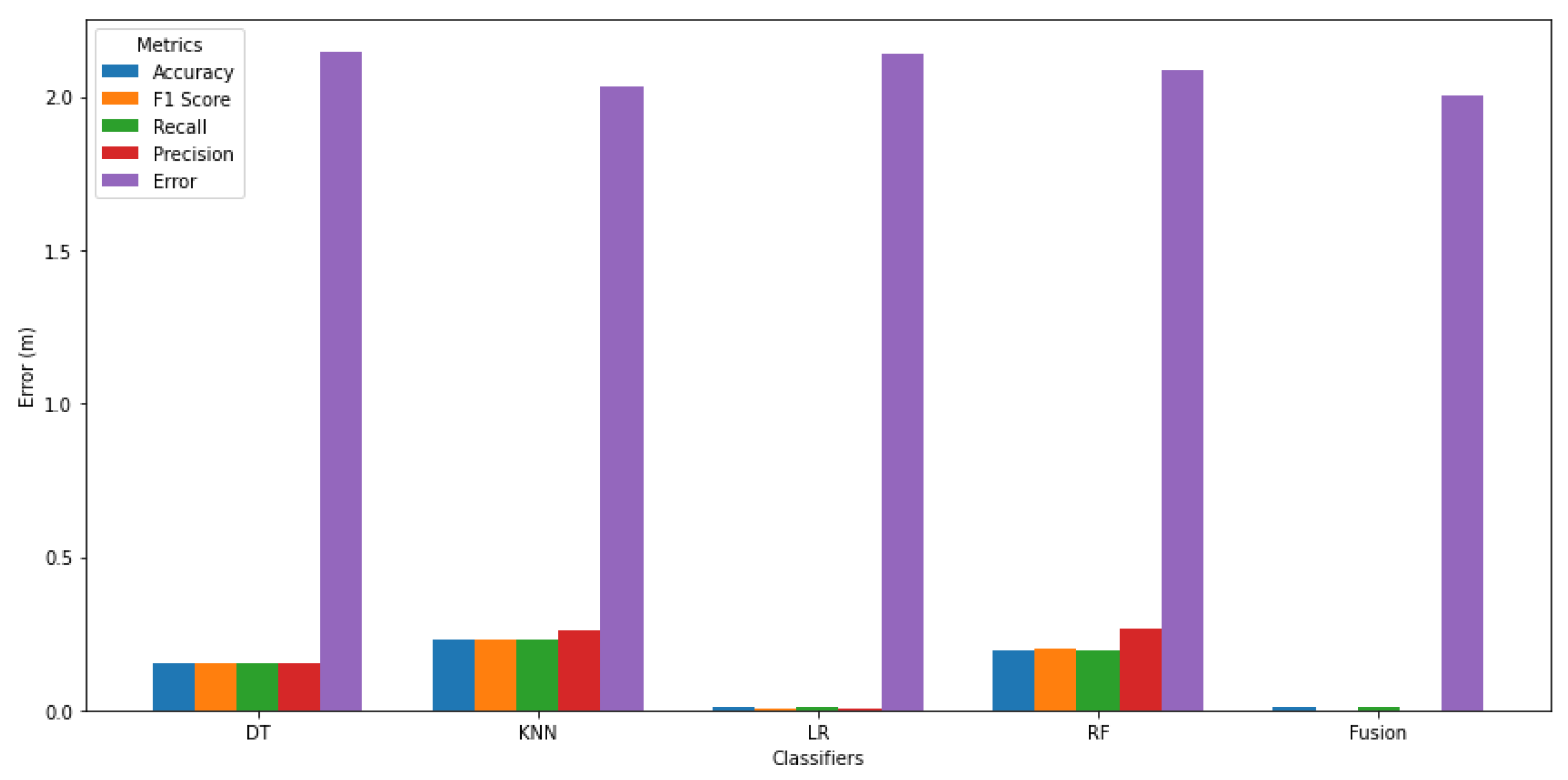

Figure 13 depicts a comprehensive comparison of the performance metrics for four individual classifiers and a fusion model for the indoor parking environment, highlighting key metrics such as Accuracy, F1 Score, Recall, and Precision. The grouped bar chart illustrates that KNN outperforms the other classifiers in all metrics, achieving an Accuracy of 0.2282 and a Precision of 0.2602, indicating its effectiveness in correctly classifying instances. Conversely, LR exhibits the poorest performance, with an Accuracy of only 0.0135 and an F1 Score of 0.0051, suggesting significant limitations in its predictive capability. RF demonstrates moderate performance, while DT shows subpar results across the board. Notably, the fusion model fails to enhance classification performance, achieving a mere Accuracy of 0.0101 and minimal values in Precision and F1 Score, which raises concerns about the efficacy of combining classifiers in this context. Importantly, this analysis underscores that multidimensional metrics are vital for evaluating model efficacy; low localization error, as indicated by RMSE and MAE, does not guarantee robust predictive performance across all dimensions. Metrics such as Accuracy, F1 Score, Recall, and Precision can reveal significant differences in model efficiency, emphasizing the need for comprehensive evaluation to ensure effective predictive capability.

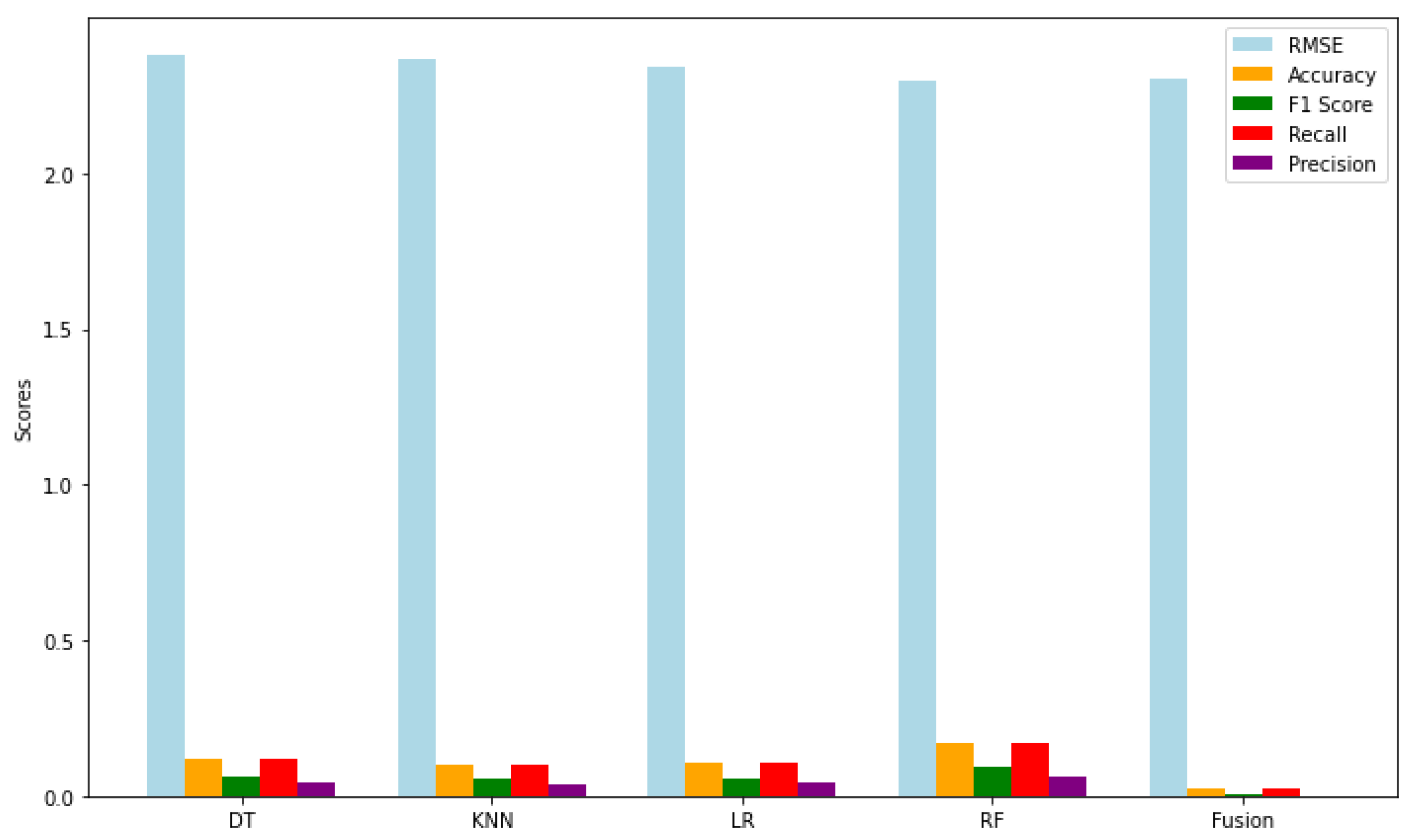

Figure 14 illustrates the performance metrics of four classifiers—DT, KNN, LR, and RF—alongside their fusion. The metrics displayed include RMSE, Accuracy, F1 Score, Recall, and Precision. The RMSE values indicate that all classifiers have moderate prediction errors, ranging from approximately 2.30 to 2.37, with RF exhibiting the lowest RMSE, suggesting it provides the most accurate predictions among the individual classifiers. Interestingly, the fusion method shows a slightly better RMSE than some individual classifiers, hinting at potential benefits in combining predictions. However, the accuracy values for all classifiers are relatively low, with RF achieving the highest accuracy at 0.1702, while the fusion method has the lowest accuracy at 0.0247. This indicates that simply averaging the predictions does not effectively enhance overall performance.

The F1 scores mirror the trends observed in accuracy, with RF performing the best at 0.0908. The fusion method's F1 score of 0.0031 suggests it struggles with balancing precision and recall, limiting its effectiveness. Similarly, recall values align closely with accuracy metrics, highlighting RF's ability to identify relevant instances at 0.1702, while the fusion method's low recall of 0.0247 indicates it likely misses many true positive cases, a critical limitation. Finally, precision scores are low across the board, with RF again leading at 0.0649, while the fusion method's precision of 0.0017 raises concerns about the reliability of its positive predictions. The experimental results demonstrate that the RF classifier consistently achieves superior performance across a range of evaluation metrics. However, the relatively weak performance of the fusion strategy emphasizes the need for careful model selection and tuning within ensemble learning frameworks. Importantly, this analysis underscores the value of adopting a multidimensional evaluation approach—beyond conventional localization error metrics such as RMSE or MAE—by incorporating classification-oriented metrics like Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1 Score. Such a comprehensive assessment offers deeper insights into model behavior and robustness. These findings highlight the necessity for further investigation into advanced fusion strategies to enhance the collective performance of integrated classifiers, as illustrated in

Figure 14.

4.5. Comparison of Localization Performance

This section presents a comparative evaluation of localization performance using the proposed M3-DynaFIPS framework, emphasizing its distinct capability to assess indoor localization systems through a multidimensional performance lens, rather than the conventional reliance on single scalar error metrics. Unlike prior state-of-the-art localization methods that report performance predominantly through metrics such as RMSE or MAE [

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62,

63,

64,

65], the proposed framework introduces a confidence-weighted probabilistic fusion strategy supported by a multidimensional evaluation paradigm. This includes classification-based metrics (Accuracy, Recall, Precision, and F1 Score), enabling a more holistic and discriminative assessment of system performance in dynamic indoor environments.

- (a)

Comparative Accuracy Against State-of-the-Art Models

The proposed fusion model was rigorously benchmarked against several well-established and high-performing localization algorithms, including UFL [

53], MMSE [

54], DFC [

55], KWNN [

56], MUCUS [

57], KAAL [

58], LPJT [

59], TCA [

60], JGSA [

61], CDLS [

62], ISMA [

63], KNN [

64], LSTP [

64], and TransLoc [

65]. These algorithms, as reported in recent literature, typically yield localization errors ranging between 2 to 3.67 meters under various conditions. In contrast, M3-DynaFIPS achieved consistently lower RMSE values across multiple real-world indoor settings:

Office (UESTC): 1.80 m (after PCA)

Library (UJI): 2.28 m (constant across preprocessing)

Indoor Parking (Huawei): 1.80 m (original) and 2.00 m (after PCA)

In particular, the proposed model outperformed UFL [

53], which previously reported an RMSE of 2.60 m in the office setting. Compared to advanced alternatives such as LPJT (2.74 m), TCA (3.14 m), CDLS (2.80 m), and KNN (3.67 m), M3-DynaFIPS consistently demonstrated superior localization accuracy, reaffirming its competitive advantage.

- (b)

Multidimensional Evaluation vs. Single-Metric Paradigms

A critical distinction between the proposed framework and existing methods lies in the evaluation methodology. While all compared models solely report scalar localization errors (e.g., RMSE or MAE) as the primary performance metric, M3-DynaFIPS explicitly challenges this one-dimensional evaluation practice. Our framework:

Captures classification performance (Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1 Score);

Assesses computational efficiency (training/testing time);

Evaluates robustness under environmental variability;

Accounts for generalizability and scalability across multiple environments.

This multidimensional assessment reveals a more comprehensive picture of model behavior. Notably, while RMSE values for the fusion model are the lowest across all environments, classification-based metrics uncover performance limitations in some scenarios—such as lower F1 scores in the Library and Office environments—demonstrating that low localization error does not necessarily equate to strong classification performance.

- (c)

Preprocessing Strategy and Robustness

The framework was utilized PCA to reduce feature dimensionality while retaining 95% of the variance. The comparative analysis shows that PCA contributes to improved computational efficiency and marginally enhances accuracy in structured environments (e.g., Office), while maintaining robustness in more complex signal spaces (e.g., Library). Despite minor trade-offs introduced by dimensionality reduction, the fusion model's performance remains stable, highlighting its resilience to feature transformation and reinforcing the value of the confidence-weighted ensemble design. In summary, the comparative analysis highlights the following key insights:

The proposed M3-DynaFIPS framework significantly outperforms state-of-the-art methods in terms of localization accuracy across diverse real-world environments.

It introduces a novel, multidimensional evaluation approach, unlike conventional methods that rely solely on RMSE/MAE.

PCA-based preprocessing improves computational efficiency with minimal loss in accuracy, particularly suitable for real-time applications.

The framework exposes latent performance limitations in classifier decision boundaries that would otherwise be overlooked by traditional evaluation metrics.

Together, these results affirm that M3-DynaFIPS is not only more accurate but also more insightful and practically deployable for dynamic, long-term indoor localization applications.