Submitted:

05 August 2025

Posted:

06 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

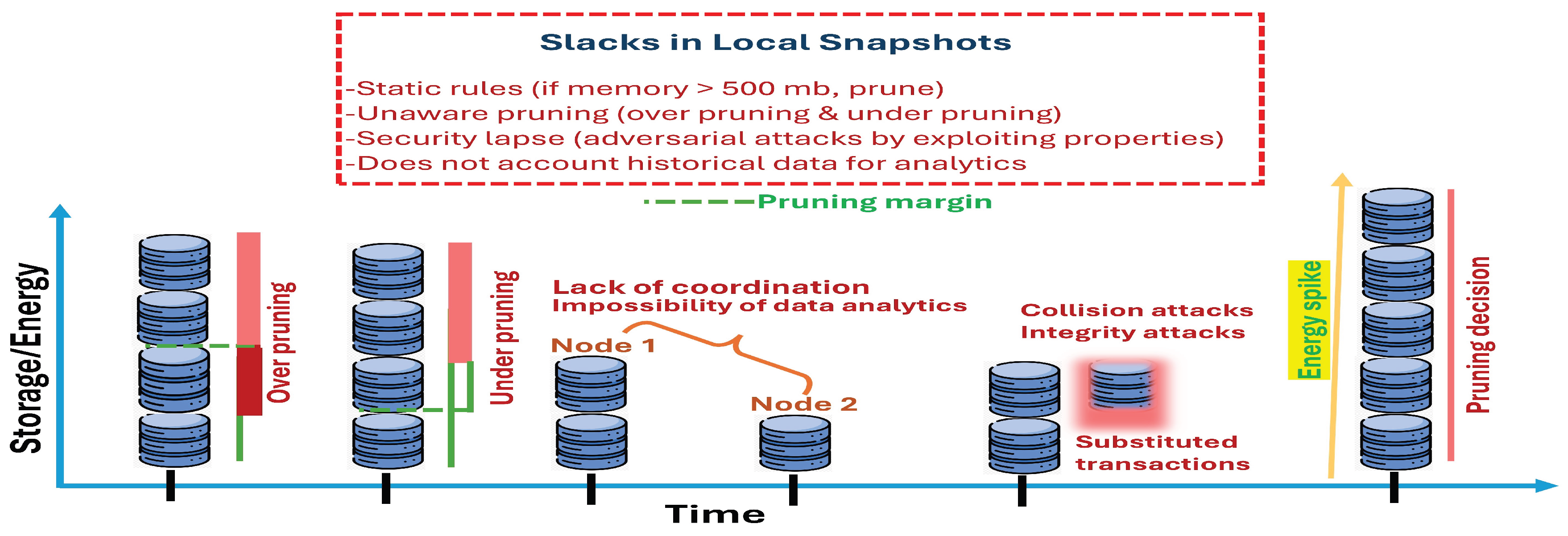

- We formulate the cost optimization problem as a function of the storage, energy and pruning frequency optimization for optimizing the policy of energy and storage consumption and pruning frequency, respectively. Precisely, we optimize storage and energy by strictly satisfying security constraints in sub-problem 1. Then, we jointly optimize the pruning frequency in sub-problem 2, where constraints are relaxed to attain a feasible solution.

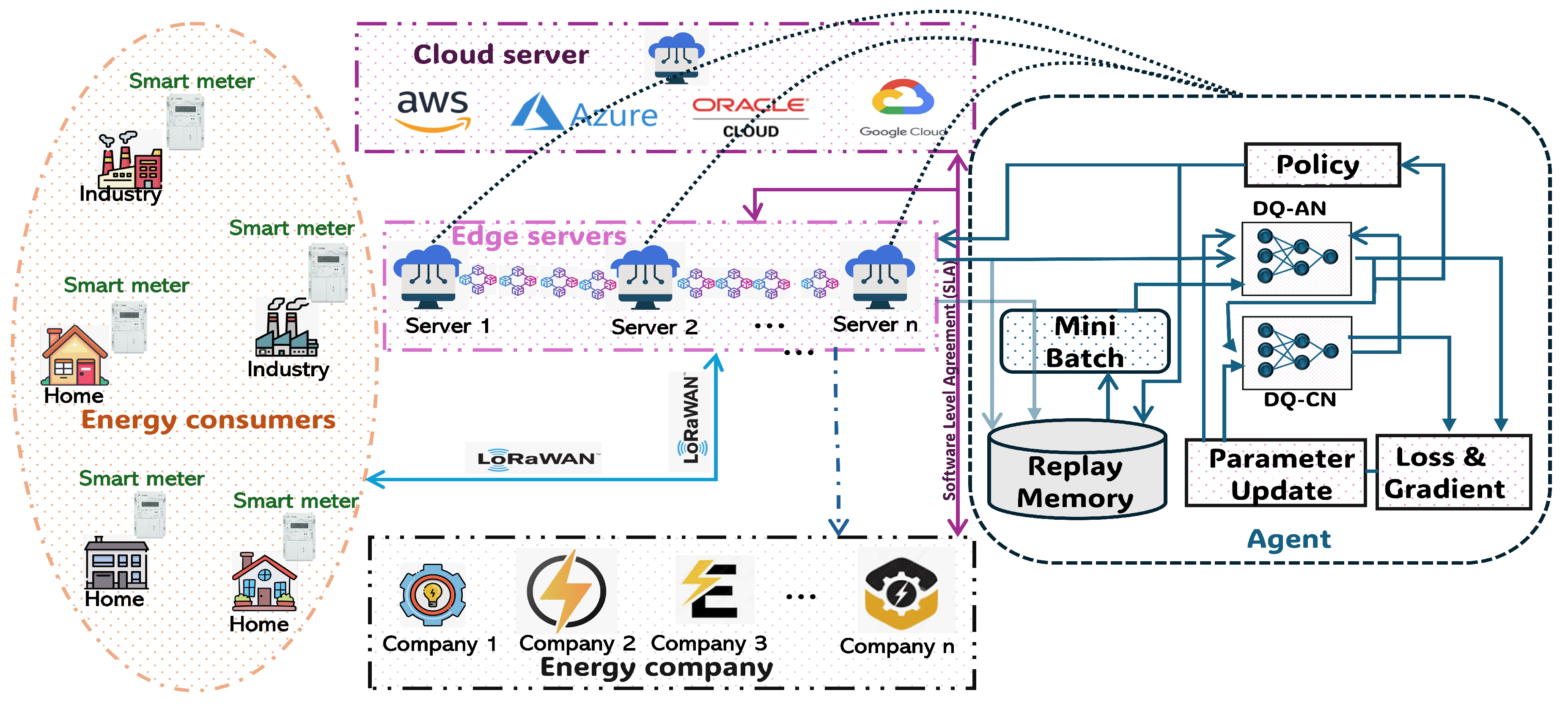

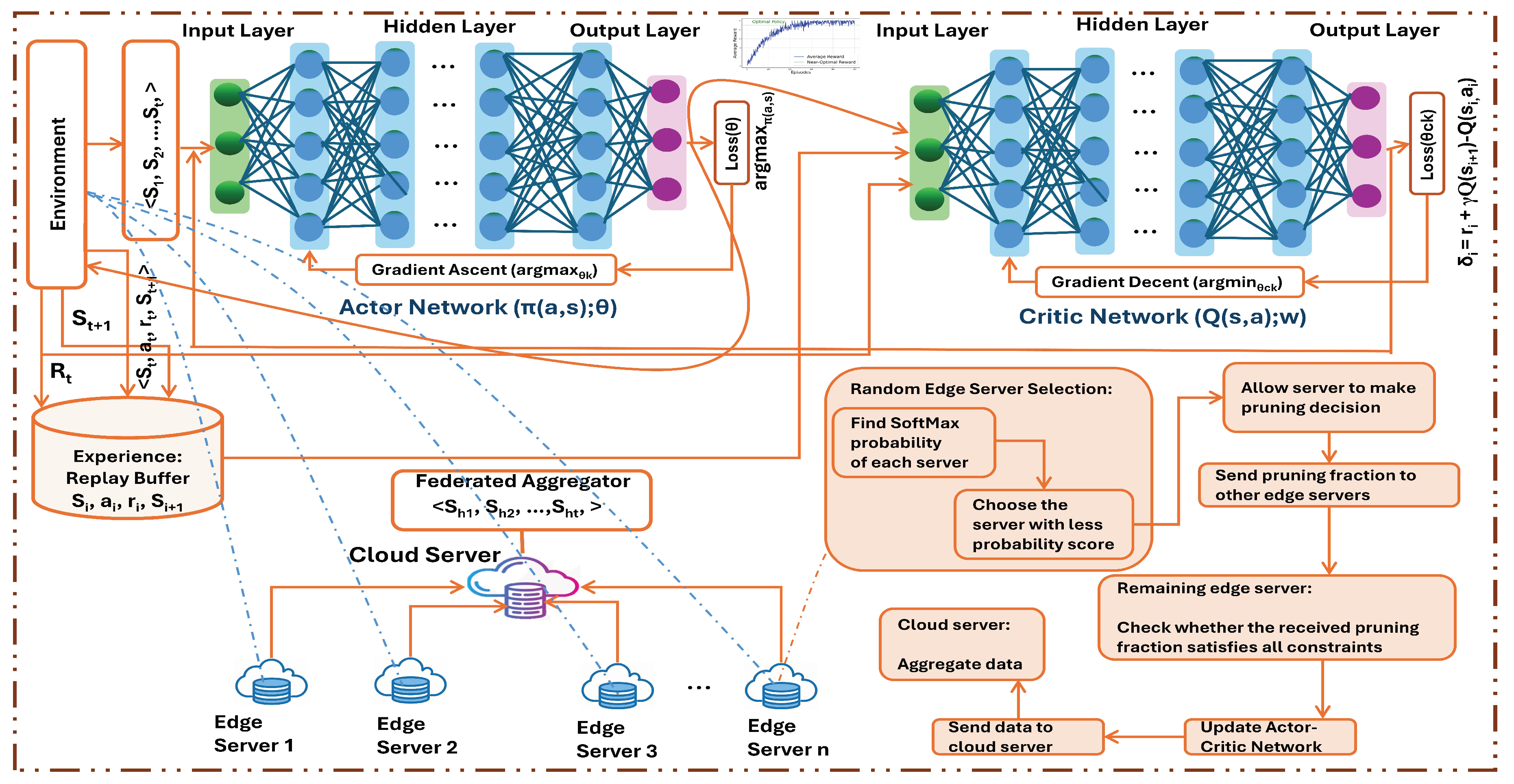

- We develop Actor-Critic method-based deep reinforcement learning algorithms (DQACN) for deep policy optimization, working cooperatively when they are deployed in the edge servers with a cloud service provider.

- Extensively, we perform the Monte Carlo simulation to gain confidence in the performance improvement of proposed algorithms over conventional local snapshots, global snapshots, ordinary deep Q network and random elimination methods.

- We implement and test the proposed algorithms to evaluate their performance robustly in the real-world environment.

2. Related Work

3. Problem Formulation

3.1. IOTA 2.0 (Coordicide)

3.2. Energy Model

3.3. Storage Model

3.4. Problem Formulation

4. Solution Approach Based on Deep Q Actor Critic Network (DQACN)

- For Algorithm 1 (SP 1):

- For Algorithm 2 (SP 2):

| Algorithm 1 Storage and Energy Optimization (SP 1) with Softmax-based Random Server Selection and Actor-Critic Evaluation |

|

| Algorithm 2 Joint Pruning Optimization (SP 2) with Softmax-based Random Server Selection and Actor-Critic Evaluation |

|

4.1. Convergence Proof

4.2. Adversary Model

4.3. Formal Security Analysis

- Real World: Parties execute the protocol (Algorithm 1) in the presence of an adversary .

- Ideal World: Parties interact with an ideal functionality that securely implements the desired behavior, with a simulator emulating the adversary.

- Security Definition: A protocol UC-realizes if, for any adversary , there exists a simulator such that every environment cannot distinguish the real-world execution (with and ) from the ideal-world execution (with and ).

- Proposition 1: Algorithm 1 ensures the first preimage resistance with non-negligible probability.

- Proposition 2: Algorithm 1 satisfies the second preimage resistance with non-negligible probability.

- Proposition 3: Collision resistance with non-negligible probability is achieved by Algorithm 1.

- Proposition 4: Integrity with non-negligible probability is ratified by Algorithm 1.

5. Simulation and Analysis

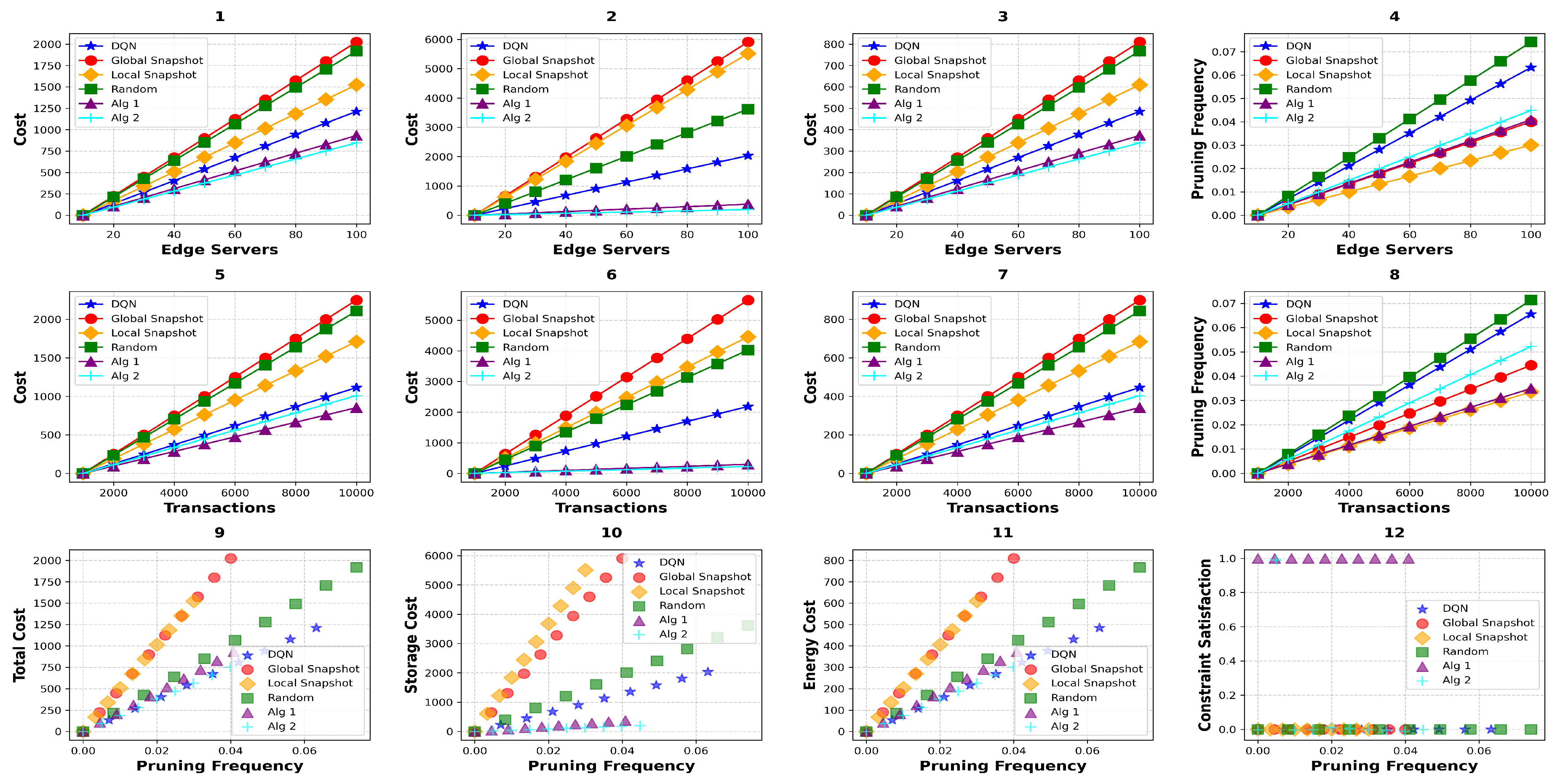

- SRQ 1: How much efficiency is attained by DQACN (Algorithm 1 and Algorithm 2) w.r.t. the local snapshot mechanism in IOTA 2.0?

- SRQ 2: How far do DQACN (Algorithm 1 and Algorithm 2) satisfy the constraints strictly?

- SRQ 3: What is the cost-benefit of the proposed algorithms over local snapshot in IOTA 2.0?

| City | 1-Year | 2-Year | 3-Year | 4-Year | 5-Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amsterdam | 5,585,700 | 11,171,400 | 16,757,100 | 22,342,800 | 27,928,500 |

| Beijing | 136,652,240 | 273,304,480 | 409,956,720 | 546,608,960 | 683,261,200 |

| Cincinnati | 1,857,440 | 3,714,880 | 5,572,320 | 7,429,760 | 9,287,200 |

| Delhi | 204,978,360 | 409,956,720 | 614,935,080 | 819,913,440 | 1,024,891,800 |

| Milan | 8,693,120 | 17,386,240 | 26,079,360 | 34,772,480 | 43,465,600 |

6. Implementation Study

7. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

| 1 | |

| 2 | |

| 3 |

Appendix A.

Appendix A.1. Proof for the NP-Hardness of SP 2

Appendix A.2. Assumptions

Appendix A.3. Proof of Theorem 1:

Appendix A.4. Proof of Theorem 2:

Appendix A.5. Ideal Functionality F PRUNE:

-

Initialization:

- Stores a ledger of transactions , where , is the Winternitz One-Time Signature (WOTS), and is the Merkle root.

- Maintains storage and energy for each server at time n.

- Security parameters: (hash length), ensuring preimage resistance, collision resistance (birthday paradox), and integrity for WOTS.

-

Transaction Submission:

-

On input from :

- –

- Compute , , and update Merkle root.

- –

- If H is collision-resistant () and verifies, add to .

- –

- Send to for storage, updating .

-

-

Pruning Request:

-

On input from :

- –

-

Check constraints:

- *

- (historical data retention).

- *

- (pruning limit).

- *

- Bills settled ().

- *

- Security: Ensure pruning retains first/second preimage resistance, collision resistance, and integrity (via sufficient transactions for hash/Merkle checks).

- –

- If valid, remove fraction of transactions, updating .

- –

- Output .

-

-

Adversary Interaction:

- can submit fake transactions .

-

rejects if:

- –

- (first preimage resistance).

- –

- but (second preimage/collision resistance).

- –

- fails WOTS verification (integrity).

- can query , but cannot modify valid entries.

-

Output:

- Return updated , , and to , , and CSP, ensuring no security violations.

Appendix A.5.1. Proof of Proposition 1

- Ideal World: In , submits . The functionality checks , rejecting if false. Since H is modeled as a random oracle with output space, , ensuring first preimage resistance.

- Real World: Algorithm 1 prunes transactions while ensuring , retaining enough transactions to maintain hash security (constraint : ). The hash function H (e.g., SHA-256) is preimage-resistant, and pruning decisions enforce sufficient storage to verify .

- Simulator : simulates ’s view by generating transactions using a random oracle H. If submits , computes and forwards to , which rejects unless . Since uses the same H, the probability of finding such that remains .

- Indistinguishability: The environment sees identical outputs in both worlds: valid transactions are stored, and invalid ones rejected. The constraint ensures enough data to enforce preimage resistance, matching ’s rejection of fake inputs.

- Algorithm 1 UC-realizes for first preimage resistance, as ’s success probability is negligible ().

Appendix A.5.2. Proof of Proposition 2

- Ideal World: rejects if but . For a random oracle H, , ensuring second preimage resistance.

- Real World: Algorithm 1’s constraint () ensures pruning retains transactions to verify . The hash function’s second preimage resistance guarantees that finding with is computationally infeasible.

- Simulator : simulates ’s view, computing for valid transactions. If submits , computes and forwards to , which rejects unless , with probability .

- Indistinguishability: cannot distinguish real and ideal worlds, as both reject with . Algorithm 1’s storage constraints ensure verification data persists, aligning with .

- Algorithm 1 UC-realizes for second preimage resistance, with ’s success probability .

Appendix A.5.3. Proof of Proposition 3

- Ideal World: rejects pairs if and . For a random oracle, the birthday paradox bounds , ensuring collision resistance.

- Real World: Algorithm 1 enforces (), retaining transactions to detect collisions. The hash function’s collision resistance ensures finding with requires operations.

- Simulator : generates for valid transactions. If submits , computes , , forwarding to , which rejects if . The probability of a collision is .

- Indistinguishability: Both worlds reject collisions identically, with Algorithm 1’s constraints ensuring sufficient storage for hash verification, matching .

- Algorithm 1 UC-realizes for collision resistance, with ’s success probability .

Appendix A.5.4. Proof of Proposition 4

- Ideal World: verifies transactions via WOTS signatures () and Merkle roots. If submits , it’s rejected unless verifies for and matches ’s Merkle root. WOTS ensures .

- Real World: Algorithm 1 uses WOTS signatures and Merkle roots, with constraint () ensuring enough transactions remain to verify integrity. Pruning only occurs for settled bills (), preserving valid data.

- Simulator : simulates ’s view, generating valid . If submits , checks via WOTS and forwards to , which rejects invalid signatures. Forgery probability is .

- Indistinguishability: sees identical ledger updates, with both worlds rejecting fake transactions. Algorithm 1’s constraints ensure that signature verification data persists.

- Algorithm 1 UC-realizes for integrity, with ’s success probability .

Appendix B.

| Metrics | IOTA 2.0 (Mana & FPC) | Blockchain (PoW) | Blockchain (PoS) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Consensus Mechanism | Mana (reputation-based) + FPC (voting-based) | PoW (hash-based) | PoS (stake-based) |

| Energy Consumption | Low | High | Low |

| Storage | Low | High | High |

| Decentralization | High | High | High |

| Scalability | High | Low | Moderate |

| Sybil Protection | Mana | Computational power | Stake |

| Pruning | Local snapshot | Possible | Possible |

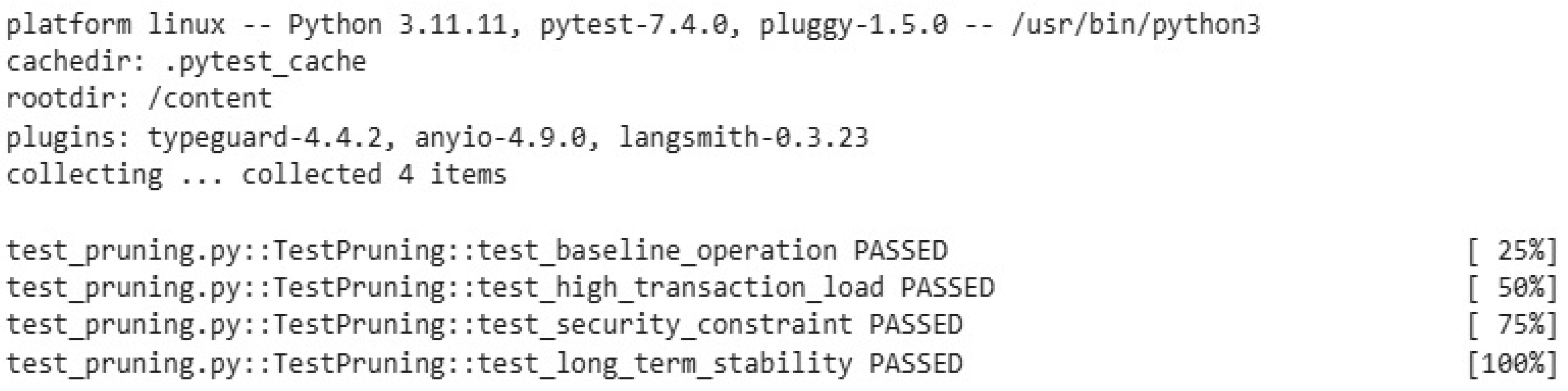

| Test Case | Description | Parameters | Test Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Operation | Run a single edge server with simulated IOTA transactions for 1 hour. | - Storage usage (MB) - Energy usage (CPU %)- Pruning frequency () | Pass |

| High Transaction Load | Simulate 10,000 transactions/hour on 3 edge servers. | - Storage reduction (%) - Energy reduction (%) - Mana value | Pass |

| Security Constraint | Inject 1000 fake transactions; monitor pruning impact. | - Storage for security (MB) - Collision resistance () - Preimage resistance ( 1 & 2) () | Pass |

| Long-Term Stability | Run 5 edge servers for 24 hours with variable transaction rates (1000–5000/hour). | - Storage usage - Energy usage - Agent’s regret (Is it sublinear?) | Pass |

Appendix C.

| Notation | Value |

|---|---|

| N | 10-100 |

| 1000-10000 | |

| 0 to 1 | |

| 1000 | |

| 5000 (base) | |

| 5000 × 0.6 = 3000 (base) | |

| 0 to 1000 | |

| 0.9 | |

| 0.1 | |

| 0.4 | |

| 0.4 | |

| 0.2 | |

| 0.05 | |

| Uniform(0.01, 0.1) | |

| 0.0001 |

| City | Population | Smart Meters [29] | Edge Servers [30] | Renting Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amsterdam | 900,000 [28] | 630,000 | 13 | 5,000 |

| Beijing | 22,000,000 [31] | 15,400,000 | 308 | 5,000 |

| Cincinnati | 300,000 [32] | 210,000 | 5 | 5,000 |

| Delhi | 33,000,000 [33] | 23,100,000 | 462 | 5,000 |

| Milan | 1,400,000 [34] | 980,000 | 20 | 5,000 |

References

- Wan, S.; Lin, H.; Gan, W.; Chen, J.; Yu, P.S. Web3: The Next Internet Revolution. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2024, 11, 34811–34825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Xiang, Y.; Shi, J.; Gao, P.; Wang, H.; Xiao, X.; Wen, B.; Li, Q.; Hu, Y.C. Make Web3.0 Connected. IEEE Transactions on Dependable and Secure Computing 2022, 19, 2965–2981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, G.; Gürcan, Ö.; Potop-Butucaru, M. G-IOTA: Fair and confidence aware tangle. In Proceedings of the IEEE INFOCOM 2019 - IEEE Conference on Computer Communications Workshops (INFOCOM WKSHPS); 2019; pp. 644–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Xiao, X.; Hecker, A.; Dustdar, S. Characterizing IOTA Tangle with Empirical Data. In Proceedings of the GLOBECOM 2020 - 2020 IEEE Global Communications Conference; 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koštál, K.; Bahar, M.N.; Numyalai, S.; Ries, M. Beyond Integration: Advancing Electricity Metering with Secure and Transparent Blockchain-IoT Solutions. In Proceedings of the 2024 47th International Conference on Telecommunications and Signal Processing (TSP); 2024; pp. 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhavana, G.; Anand, R.; Ramprabhakar, J.; Meena, V.; Jadoun, V.K.; Benedetto, F. Applications of blockchain technology in peer-to-peer energy markets and green hydrogen supply chains: a topical review. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 21954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, W.; Xie, X.; Huang, Y.; Qian, T.; Li, W.; Li, X.; Xu, Z. Exploring the potential of IoT-blockchain integration technology for energy community trading: Opportunities, benefits, and challenges. CSEE Journal of Power and Energy Systems 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Ma, S.; Guo, C.; Wu, Y.; Dai, H.N.; Wu, D. Blockchain-based power energy trading management. ACM Transactions on Internet Technology (TOIT) 2021, 21, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, C.; Collins, J.; Prestwich, S.; Visentin, A. Electricity price forecasting in the irish balancing market. Energy Strategy Reviews 2024, 54, 101436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, J.W.; Ramachandran, G.S.; Dorri, A.; Jurdak, R. Blockchain data storage optimisations: a comprehensive survey. ACM Computing Surveys 2024, 56, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Feng, G.; Ren, Y.; Zhang, X. On cloud storage optimization of blockchain with a clustering-based genetic algorithm. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2020, 7, 8547–8558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Y.; Jin, S.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Y. Blockchain storage and computation offloading for cooperative mobile-edge computing. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2021, 8, 9084–9098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alofi, A.; Bokhari, M.A.; Bahsoon, R.; Hendley, R. Optimizing the energy consumption of blockchain-based systems using evolutionary algorithms: A new problem formulation. IEEE Transactions on Sustainable Computing 2022, 7, 910–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akrasi-Mensah, N.K.; Agbemenu, A.S.; Nunoo-Mensah, H.; Tchao, E.T.; Ahmed, A.R.; Keelson, E.; Sikora, A.; Welte, D.; Kponyo, J.J. Adaptive storage optimization scheme for blockchain-IIoT applications using deep reinforcement learning. IEEE Access 2022, 11, 1372–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Ren, Y.; Xu, M.; Feng, G. An improved nsga-iii algorithm based on deep q-networks for cloud storage optimization of blockchain. IEEE Transactions on Parallel and Distributed Systems 2023, 34, 1406–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanis, Z.; Durusu, A. Cooperative Behaviors and Multienergy Coupling through Distributed Energy Storage in the Peer-to-Peer Market Mechanism. IEEE Access 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreps, D.M. Nash equilibrium. In Game theory; Springer, 1989; pp. 167–177.

- Ma, J.; Zhang, X.; Li, X. Demystifying Blockchain Scalability: Sibling Chains with Minimal Interleaving. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Security and Privacy in Communication Systems. Springer; 2023; pp. 265–286. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton, R.S.; Barto, A.G. Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction, 2nd ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bertsekas, D.P.; Tsitsiklis, J.N. Neuro-Dynamic Programming; Athena Scientific: Belmont, MA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Tsitsiklis, J.N. Asynchronous Stochastic Approximation and Q-Learning. Machine Learning 1994, 16, 185–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konda, V.R.; Tsitsiklis, J.N. Actor-Critic Algorithms. SIAM Journal on Control and Optimization 2000, 42, 1143–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, R.S.; McAllester, D.A.; Singh, S.P.; Mansour, Y. Policy Gradient Methods for Reinforcement Learning with Function Approximation. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 12 (NIPS 1999); Solla, S.A.; Leen, T.K.; Müller, K.R., Eds. MIT Press; 2000; pp. 1057–1063. [Google Scholar]

- Tsitsiklis, J.N.; Van Roy, B. An Analysis of Temporal-Difference Learning with Function Approximation. IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control 1997, 42, 674–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakade, S. A Natural Policy Gradient. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 14 (NIPS 2001); Dietterich, T.G.; Becker, S.; Ghahramani, Z., Eds. MIT Press; 2002; pp. 1531–1538. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, R.J. Simple Statistical Gradient-Following Algorithms for Connectionist Reinforcement Learning. Machine Learning 1993, 8, 229–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filar, J.; Vrieze, K. Competitive Markov Decision Processes; Springer: New York, NY, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Population Division. World Urbanization Prospects, 2018. 2018 Revision.

- International Energy Agency. Smart Meters in Buildings, 2023.

- AWS IoT Architecture Guidelines, 2023.

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. China Statistical Yearbook, 2023.

- U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey, 2023. 2023 Estimates.

- UN Data. India Population Projections, 2023.

- Eurostat. Urban Population Statistics, 2023.

| Notation | Description |

|---|---|

| Generic Variables | |

| N | Total number of edge servers |

| n | Time |

| Subset of edge servers participating in FPC consensus at time n | |

| Energy cost per hash computation | |

| Energy cost per signature computation | |

| Energy cost per pruning operation | |

| Energy cost per FPC query/vote operation at server i | |

| Energy cost per mana update operation at server i | |

| Energy cost per message attachment operation at server i | |

| Efficiency factor of server i | |

| Mana of server i at time n | |

| Nodes involved in the consensus (binary variable) | |

| Mana decay rate | |

| Mana scaling factor | |

| Set of smart meters pledging mana to server i | |

| Message Variables | |

| Number of messages processed by server i at time n | |

| Number of hash computations per message at server i | |

| Number of signature verifications per message at server i | |

| Number of FPC queries/votes by server i at time n | |

| Number of mana updates due to message issuance by server i at time n | |

| Number of mana decay updates by server i at time n | |

| Pruning Variables | |

| Fraction of messages pruned by server i at time n | |

| Total unpruned messages at server i at time n | |

| Number of finalized messages at server i at time n | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).