Biological motivation supports the hybrid model design, but rigorous mathematical analysis remains essential to establish its validity and predictive reliability. This section systematically investigates the coupled PDE-ABM framework through three analytical pillars: (i) well-posedness of the PDE-ABM system (

Section 4.1), guaranteeing solution existence, uniqueness, and regularity; (ii) master equation and mean-field analysis (

Section 4.2), connecting discrete stochastic dynamics to deterministic continuum-scale approximations; and (iii) validity regimes for moment closure approximations, linking microscopic randomness with macroscopic behavior. This triad ensures mathematical robustness for therapeutic applications, including chemotherapy optimization and anti-angiogenic interventions.

4.1. Well-Posedness

We establish existence, uniqueness, and regularity of weak solutions for the coupled PDE-ABM system governing the continuous fields

. Without agent interactions, the PDEs reduce to a classical linear parabolic system with guaranteed well-posedness. We formalize this foundation using the Lions–Gelfand triple framework [Theorem 10.9 [

42]; see [

43] for detailed proofs.

Lemma 1 (J.-L. Lions). Let be a Gelfand triple, with V and H Hilbert spaces and V densely and continuously embedded into H. The scalar product and norm for H are and , and the norm for V is . Let . Suppose for almost every , is a time-dependent bilinear form satisfying:

- (i)

For all , the function is measurable.

- (ii)

for almost every and all .

- (iii)

for almost every and all .

where , M, and C are constants. Then for and , there exists a unique function

satisfying the weak formulation:

with initial condition .

We now apply this result to the coupled reaction-diffusion equations on the finite time interval

:

where

and

incorporates agent-dependent reaction terms:

We omit the analysis of the endothelial density equation:

Classical two-dimensional Keller–Segel systems exhibit chemotactic blow-up, that is, unbounded density in finite time [

44,

45], but admit global solutions under small-mass conditions. In particular, consider the following parabolic-elliptic Keller-Segel system:

where

is the outward unit normal to

and

denotes the spatial average of

n. Assume the initial mass satisfies:

Then, a global-in-time weak solution exists under the following conditions:

- (i)

Bounded domain case: If U is a bounded, connected domain and ,

- (ii)

Whole space case: If , with and .

This follows from [

44,

46].

1

Discrete agents represent the endothelial population in our hybrid formulation, replacing continuous density and further regularizing dynamics. Each tip occupies at most one lattice site. Vessel elongation occurs with a fixed period

, and branching requires the tip cell age to exceed the threshold

(

). Anastomosis stabilizes the system: tip encounters cause emerging, reducing the tip count. These rules ensure a finite agent population

and prevent uncontrolled mass concentration, consistent with lattice-based chemotaxis ABMs [

13,

28,

47,

48]. We thus focus our analysis on the

subsystem. To manage PDE-ABM coupling, we introduce:

Assumption A1 (PDE-ABM Coupling).

- (i)

The spatial domain is bounded with boundary .

- (ii)

The initial data is nonnegative and belongs to .

- (iii)

For all and lattice sites :

Assumption A1 (iii) imposes a uniform local density bound, not global agent boundedness, as tumor proliferation may increase over time. This aligns with the biological crowding constraint in ABM rules: lattice sites accommodate finitely many agents within radius , and cell division halts at local density . Consequently, global agent growth does not compromise the local boundedness of PDE source terms, which is essential for coupled system well-posedness.

We define the weak formulation by seeking

satisfying

and

for each

, with:

and initial conditions

. Here

denotes the

inner product, and

is the

duality pairing.

Theorem 1 (Existence and Uniqueness of Weak Solutions).

Assumption A1 guarantees unique weak solutions for the coupled PDE-ABM system (4.1) with:

Proof. Apply Lemma 1 to each component via the Gelfand triple and coercive, bounded bilinear forms for . □

We rigorously couple ABM and PDE dynamics through time discretization and operator splitting:

Theorem 2 (Well-posedness of the Coupled PDE-ABM System). Under Assumption A1 on with time steps :

- (i)

The PDE subsystem admits a unique weak solution with Theorem 1 regularity.

- (ii)

The ABM subsystem defines càdlàg Markov process almost surely for agent marks

Proof. Use mathematical induction over intervals . For , Theorem 1 establishes existence, uniqueness, and regularity on with initial data and fixed agent . Assume the result holds on . For :

- (i)

Solve the parabolic subsystem on

:

which has unique weak solutions by Theorem 1.

- (ii)

Evolve ABM marks on

via:

where

is the Markov transition operator. Piecewise constant agent trajectories with right-continuous and left limits ensure the càdlàg Markov property.

Induction extends the result to . □

Remark 1 (Justification of Stepwise Decoupling). Theorem 2 solves the PDE subsystem on each interval with fixed agent configuration . This approach directly implements the hybrid model’s operator–splitting scheme: PDE fields evolve continuously via (4.3) on . While agent updates occur discretely at . Consequently, PDE source terms are piecewise constant in time, preserving well-posedness as a linear parabolic problem on each subinterval. The ABM update (2.2) defines a Markov map at mesh points.

Since the alternating-update rule defines the hybrid model itself, no splitting error accumulates. The piecewise-constant ABM forcing is an exact model component. The induction argument formalizes this sequential construction, guaranteeing existence and uniqueness on each and hence on .

We examine the decoupled system to highlight the ABM’s role. The resulting linear parabolic PDEs with Neumann boundary conditions admit a classical solution via spectral decomposition of the Neumann Laplacian (proof in [

49]):

Theorem 3 (Well-Posedness of Sole PDE System).

The system

admits a unique classical solution:

where the Neumann Laplacian eigenbasis satisfies:

with eigenvalues . Coefficients are . Each is spatially smooth for and temporally analytic for .

The spectral result confirms that without ABM interactions, the PDE subsystem maintains full regularity and decouples completely. In the coupled system, agent density constraints ensure well-posedness despite nonlinear agent-driven reaction terms. Thus, our hybrid framework is both analytically well-posed and biologically interpretable, providing a solid foundation for clinical applications.

Weak solution existence establishes a rigorous mathematical foundation for hybrid models integrating microscopic interactions with macroscopic behaviors. The proof of well-posedness for the coupled PDE-ABM system guarantees that the model behaves predictably under biologically relevant conditions, e.g., bounded agent density due to cell crowding and realistic spatial constraints. This is critical for ensuring that simulated phenomena like angiogenesis, hypoxia-driven resistance, and spatial tumor heterogeneity reflect biological processes rather than numerical artifacts. From a clinical perspective, this mathematical well-posedness lays the foundation for future optimization of treatment regimens (e.g., dosing schedules) within a consistent modeling framework.

4.2. Master Equation Formulation and Mean-Field Limit

Having established deterministic well-posedness, we now analyze stochastic aspects of agent dynamics. Integrating stochastic agent-based dynamics within a continuum PDE framework requires principled linkages between microscopic randomness and macroscopic observables. The CME provides this foundation by capturing the probabilistic evolution of the agent state space. This section derives a lattice-based CME for the hybrid PDE-ABM system, computes first-order moment equations, and establishes conditions justifying a deterministic mean-field approximation. By unifying the hybrid PDE-ABM into a continuous description (4.6), our model connects microscale interactions with macroscale dynamics, replacing the computationally demanding ABM structure in dense tumor regions with an efficient PDE solver.

We analyze a coarse-grained mesoscopic representation of the ABM component. Consider a regular lattice with spacing over the spatial domain. The local agent density function denotes the tumor agent count at site and time t.

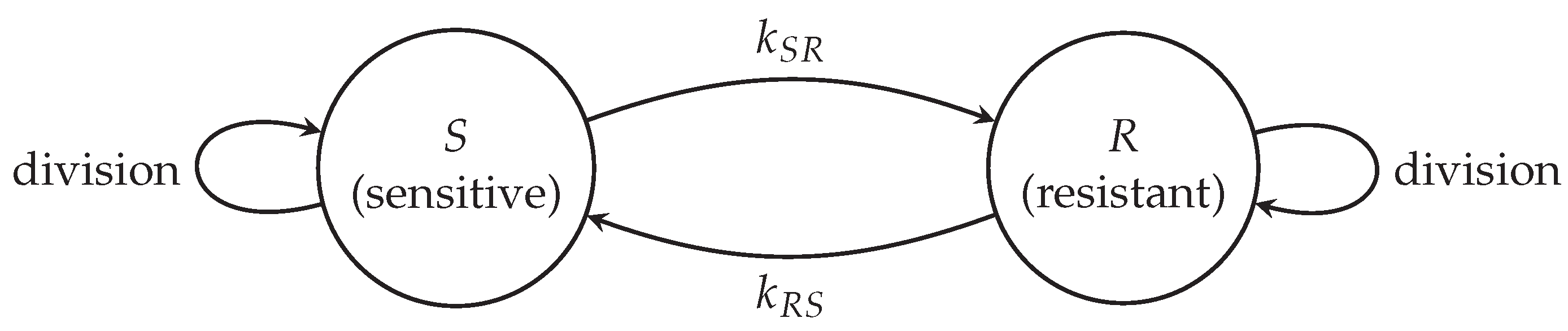

Let represent the discrete ABM configuration at time t. A continuous-time Markov process on governs the stochastic evolution of , with state-dependent transition rates determined by agent rules, including proliferation, death, motility, and phenotypic switching.

Let

denote the probability mass function over all ABM configurations. The CME governing the evolution of

is:

where

denotes the transition rate from configuration

to

. Each transition corresponds to elementary stochastic events with specific forms:

- (i)

Brownian Movement: each cell jumps to neighboring site

at rate

where

denotes the Von Neumann neighborhood (four orthogonal neighbors) of

. The coefficient

originates from the Fokker-Planck equation

for tumor agents undergoing Brownian motion:

with

independent standard Brownian motions.

- (ii)

Regulated Proliferation: Using the Heaviside function

H to identify normoxic states, only normoxic cells proliferate at rate

- (iii)

Drug-Induced Death: Apoptosis occurs at constant rate : .

- (iv)

Mutation: mutation preserves cell counts per voxel, and thus does not appear in the CME.

Define the expected local agent density:

The cádlág property

yields:

The CME governs the change rate due to proliferation, death, and movement:

This equation is unclosed because first-order moments depend on higher-order correlations through nonlinear functions. A tractable macroscopic approximation requires closure. The mean-field approximation assumes statistical independence between agent states, providing the first-moment closure:

Applying this closure yields:

Define the density

gives

, producing the CME for

:

The deterministic approximation holds under the law of large numbers when local agent populations are large and suppress fluctuations. The continuum limit yields the macroscopic density equation:

where

. In the continuum limit, the local cell count is

where

and

denote tumor and vessel agent spatial densities. The uniform bound

implies the tumor cell density constraint:

where

begin the disk area. The maximum local cell count follows as

thus

.

Therefore, applying first-order moment closure yields a deterministic approximation of the tumor density dynamics. This closure is valid under large-population and weak-correlation regimes.

Theorem 4 (Mean–Field Limit for the Tumor Cell Density).

Let denote tumor cell agent counts evolving under the stochastic rules in Section 2 on a lattice with spacing . Assume:

- (i)

Initial agent positions and states are i.i.d. with macroscopic density .

- (ii)

-

The maximum local occupancy satisfies

where is the maximal local cell–vessel occupancy value and the cell radius.

Then, as and , the tumor cell density satisfies:

Here is the macroscopic carrying capacity, H the Heaviside function, the positive part, and d the drug concentration. Diffusion arises from cellular Brownian motion; the reaction term models normoxic proliferation and drug-induced apoptosis.

Theorem 4 provides the leading–order deterministic approximation via first–order moment closure. Agent-based simulations are computationally intensive for tumor populations. The mean-field limit unifies the hybrid model into a computationally efficient continuum description:

The mean-field equation (4.6) allows one to interpret complex, stochastic agent-based behavior through simpler, deterministic PDEs. This bridge from microscale (single-cell events like stochastic phenotype switching) to macroscale (tumor cell density evolution) enables: (i) analytical estimation of tumor front velocity, aiding prognosis (e.g., time to vascular invasion or metastatic risk), (ii) sensitivity to environmental factors (e.g., hypoxia, drug gradients) to be encoded directly in continuous equations, which may inform spatially-resolved treatment planning, and (iii) approximate solutions in real time, supporting integration into clinical decision-support tools, where full ABM simulations may be computationally prohibitive. On the other hand, mean-field approximations neglect fluctuations, so we clarify valid parameter regimes and biological relevance.

Remark 2 (Validity Regime of the Moment Closure). Equation (4.5) uses first–order moment closure , neglecting second-order moments and higher–order cumulants. This requires:

- (i)

Large local populations: per site , making demographic noise under central limit scalings;

- (ii)

Weak correlations:Negligible spatial correlations between neighboring voxels at scale , ensured by fast mixing (large ε) or weakly interactions.

Fluctuations then contribute only corrections, so (4.5) captures population dynamics to leading order.

Biologically, these hold in dense tumor regions where local interactions average stochasticity. They fail in:

- (i)

Early growth stages, invasion fronts, or metastatic niches with small and non-negligible extinction;

- (ii)

Strongly heterogeneous microenvironments where correlations and clustering invalidate the weak–fluctuation assumption.

Solutions include second-order moment closure (e.g., pair approximations) or hybrid models retaining ABM structures in critical regions while using PDE surrogates elsewhere. These are active multiscale modeling research areas.