Submitted:

24 July 2025

Posted:

25 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials & Methods

2.1. PDE Model for Continuous Fields

- (i)

- Tumor cells consume oxygen and TAF at fixed rates.

- (ii)

- Drug diffusion and decay are assumed isotropic and linear.

- (iii)

- Angiogenic tip cells follow TAF gradients via chemotaxis.

- (iv)

- Mutation is modeled as a neutral stochastic process.

- (v)

- DNA repair is included but lacks mechanistic biochemical modeling.

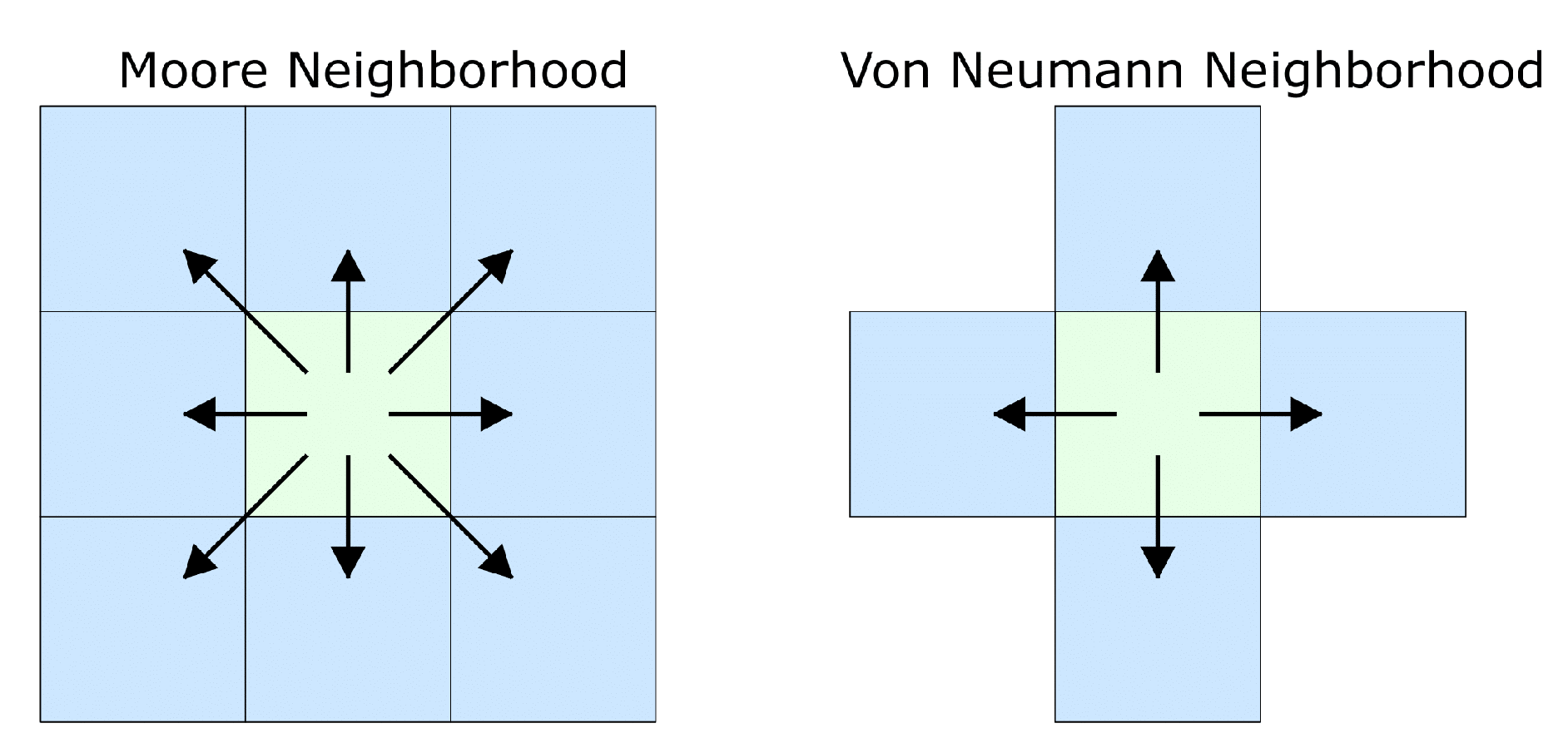

2.2. Agent-Based Model

2.2.1. Tumor Dynamics

- (i)

- is the index of the ancestor cell,

- (ii)

- records the branching decision at the j-th division,

- (iii)

- counts mitotic generations since initiation.

- (i)

- Normoxic () if ,

- (ii)

- Hypoxic () if ,

- (iii)

- Apoptotic (removed immediately from ) if , where are critical thresholds.

- (i)

- Random mutation, where one of predefined phenotypes is selected with equal probability during mutation [54];

- (ii)

- Linear mutation, where phenotypes evolve deterministically along a predefined trajectory of increasing resistance and aggressiveness. Although linear mutation avoids abrupt phenotypic jumps, it enforces a deterministic progression toward aggressive phenotypes, disregarding microenvironmental selection pressures.

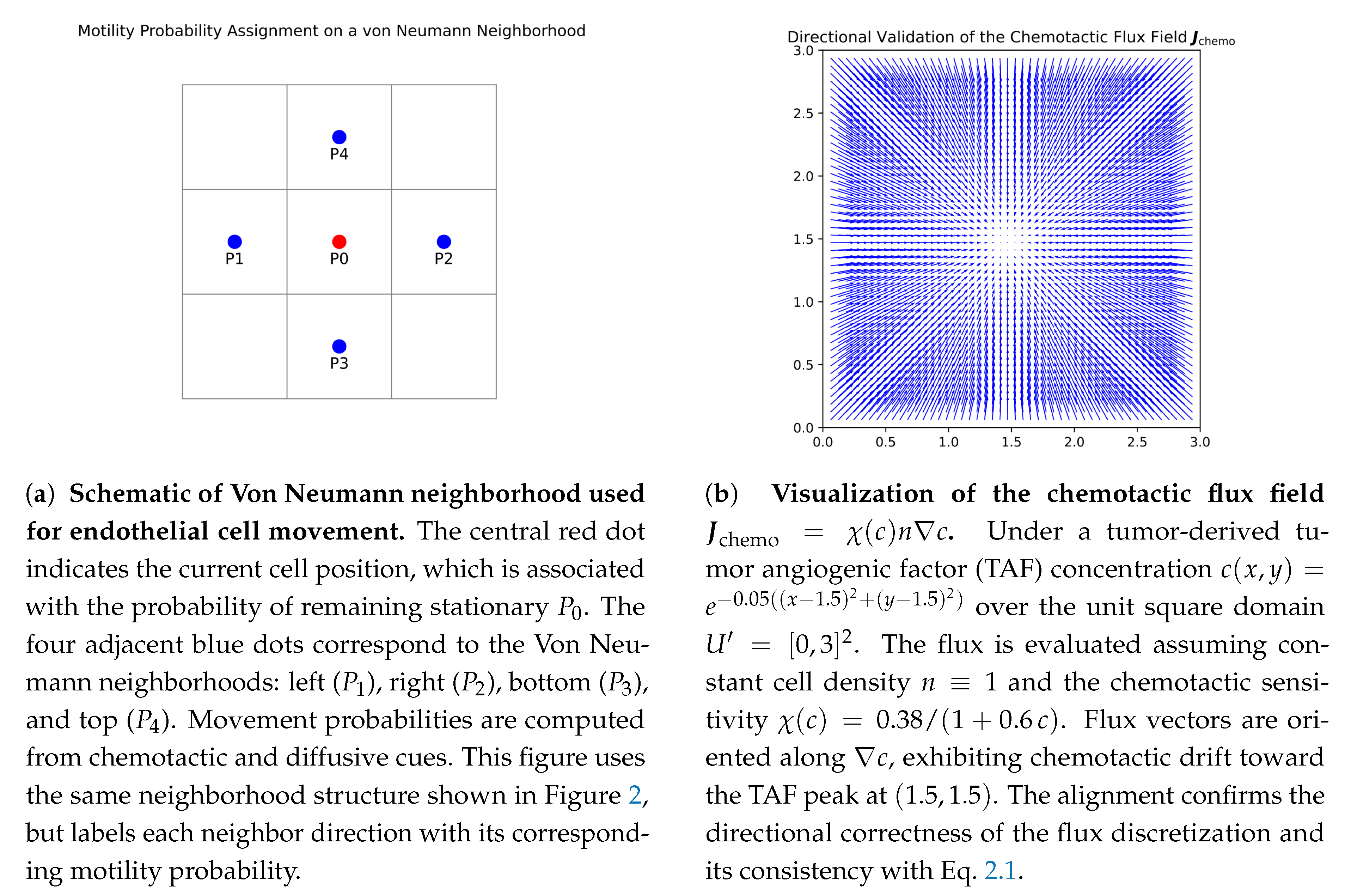

2.2.2. Angiogenesis Dynamics

2.2.3. Biological and Modeling Implications

- (i)

- Multiscale Coupling Validity: The result ensures that stochastic cell-scale events (division, migration, vessel remodeling) can be consistently embedded into tissue-scale PDE frameworks.

- (ii)

- Predictive Stability: The simulation results on hypoxic zones, nutrient distribution, and vascular remodeling demonstrate mathematical robustness rather than being numerical artifacts.

- (iii)

- Groundwork for Control and Optimization: Well-formulated mathematical model creates possibilities to study therapeutic methods such as chemotherapy scheduling and anti-angiogenic therapy through a rigorous mathematical oncology framework.

2.3. Discretization Framework

3. Results

3.1. Parameterization and Non-dimensionalization

3.2. Agent-based Simulation Design

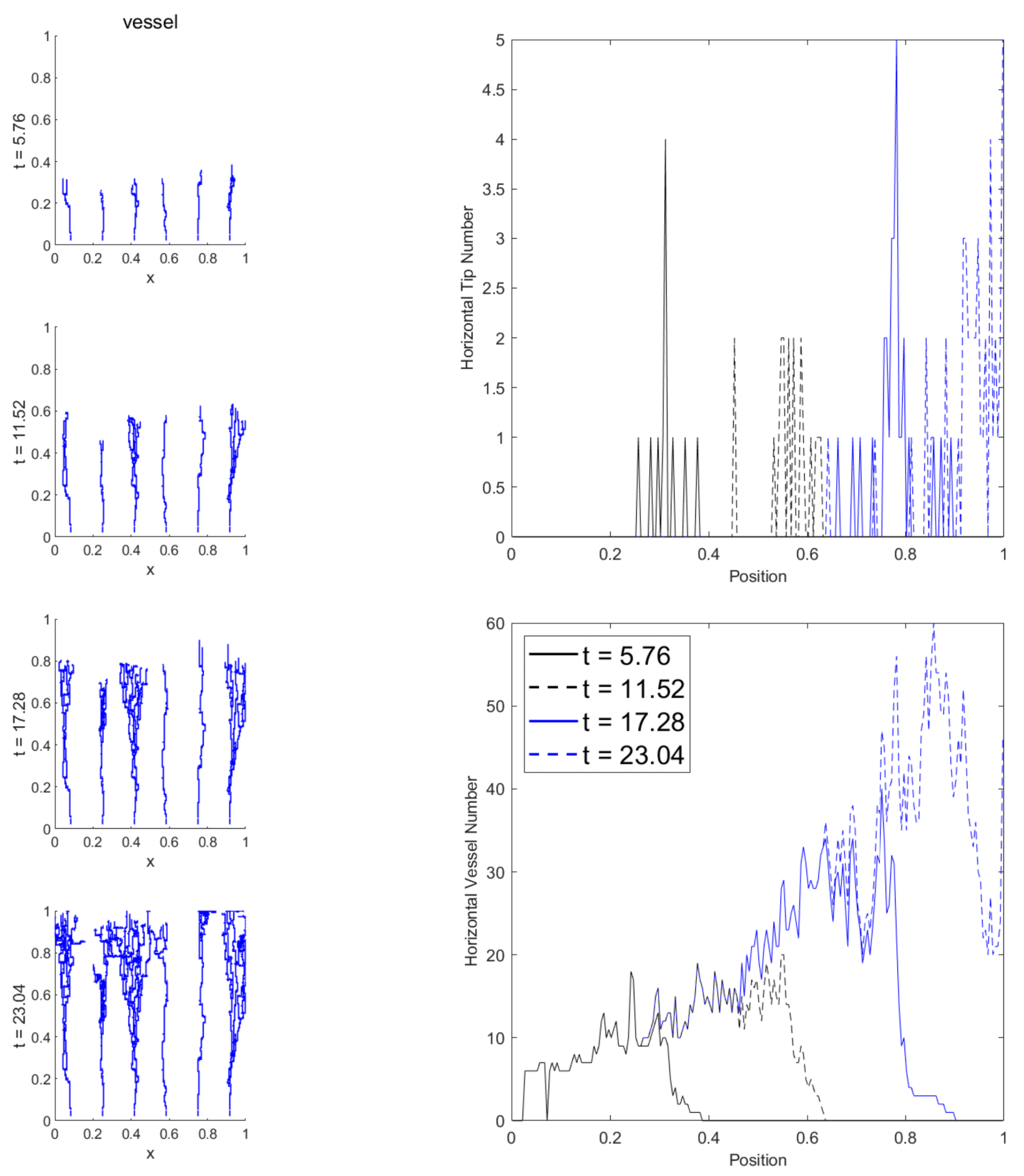

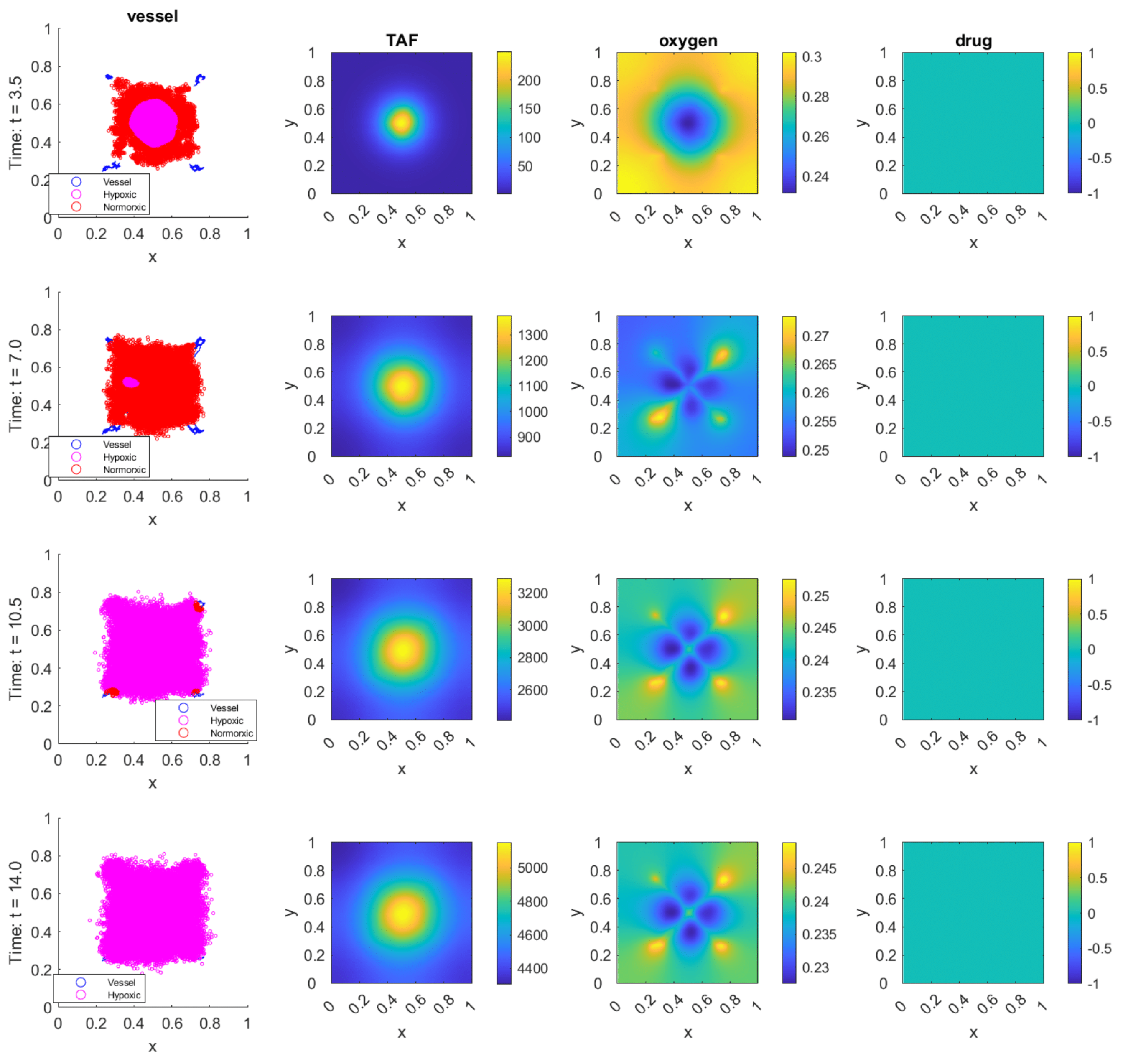

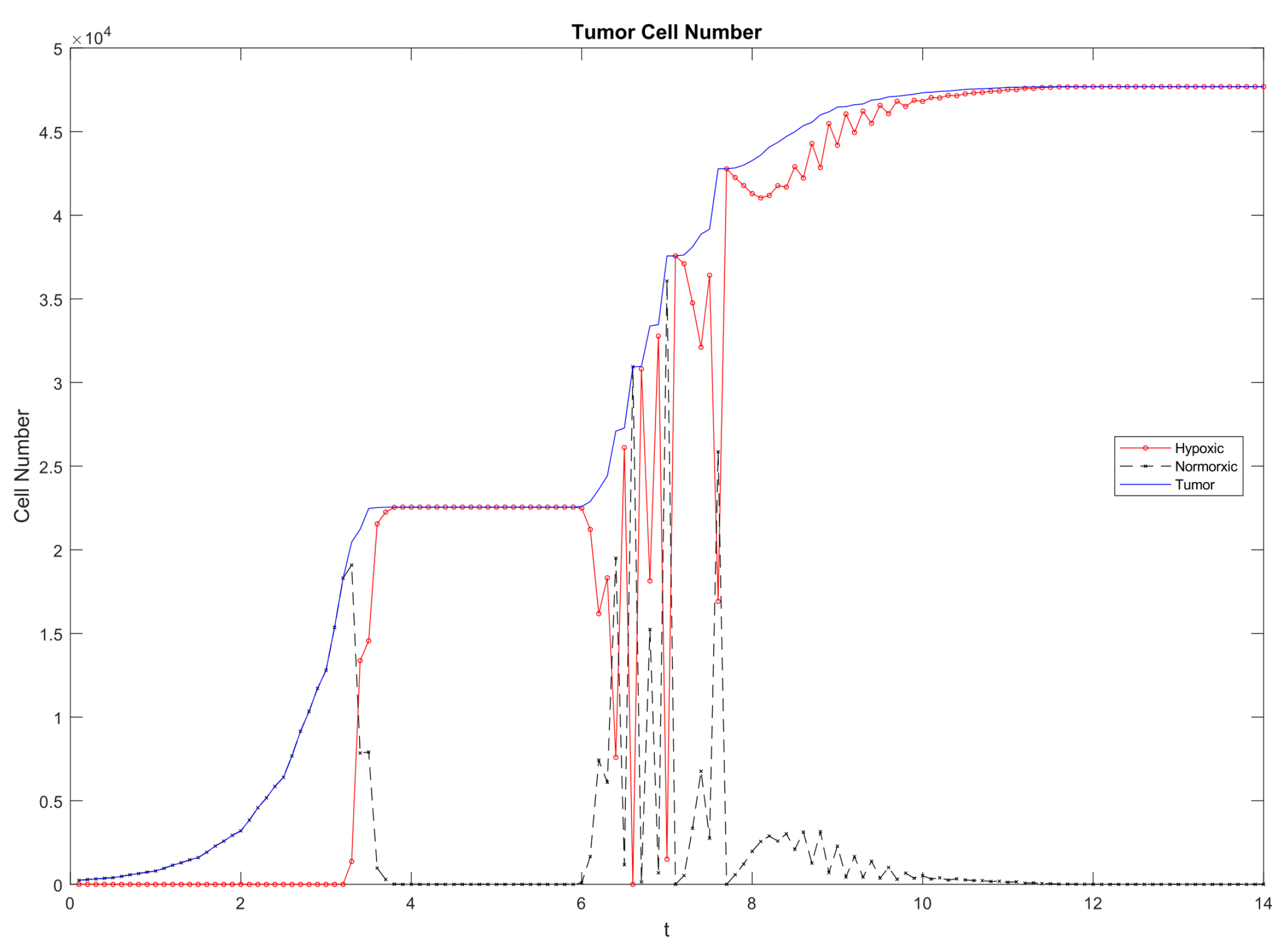

3.3. Emergent Vascularization and Tumor Growth

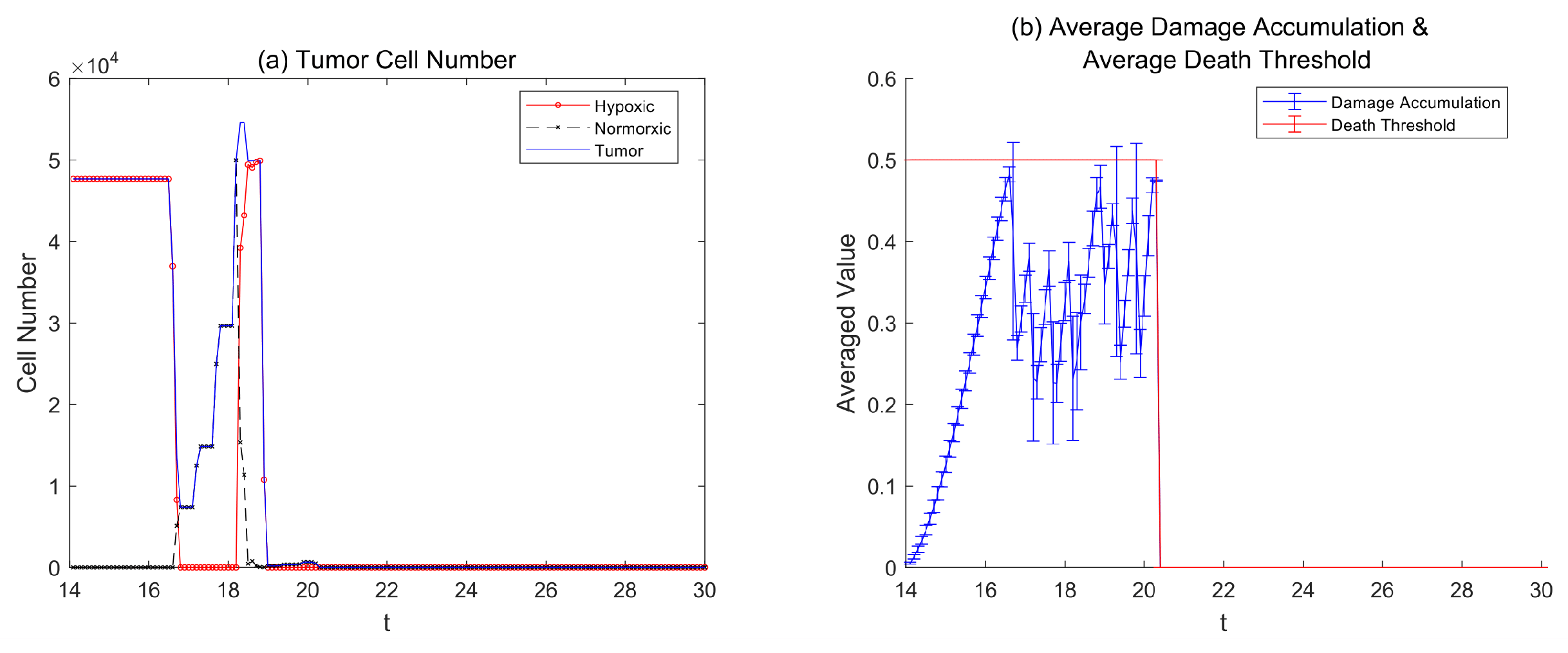

3.4. Therapy Without Resistance

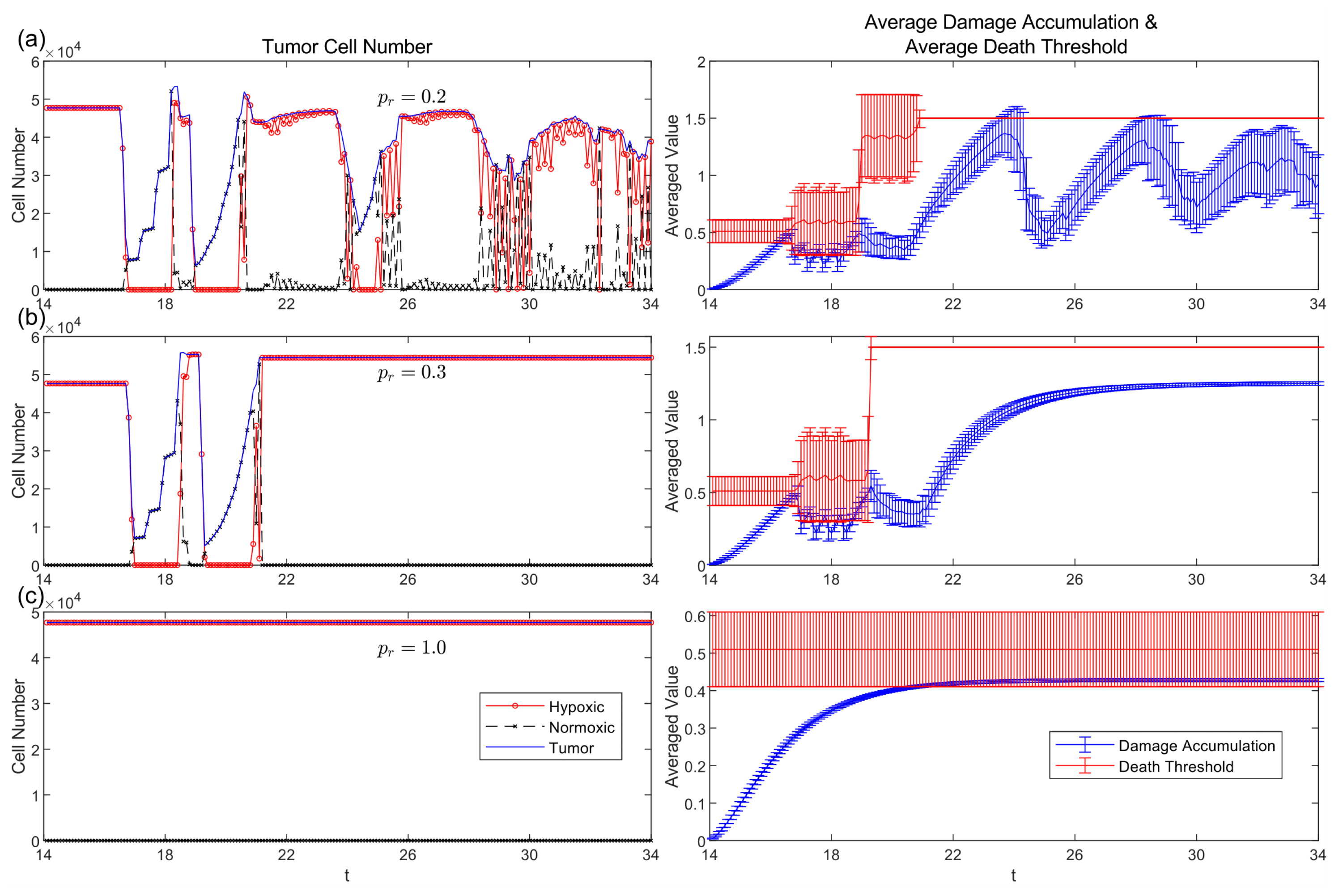

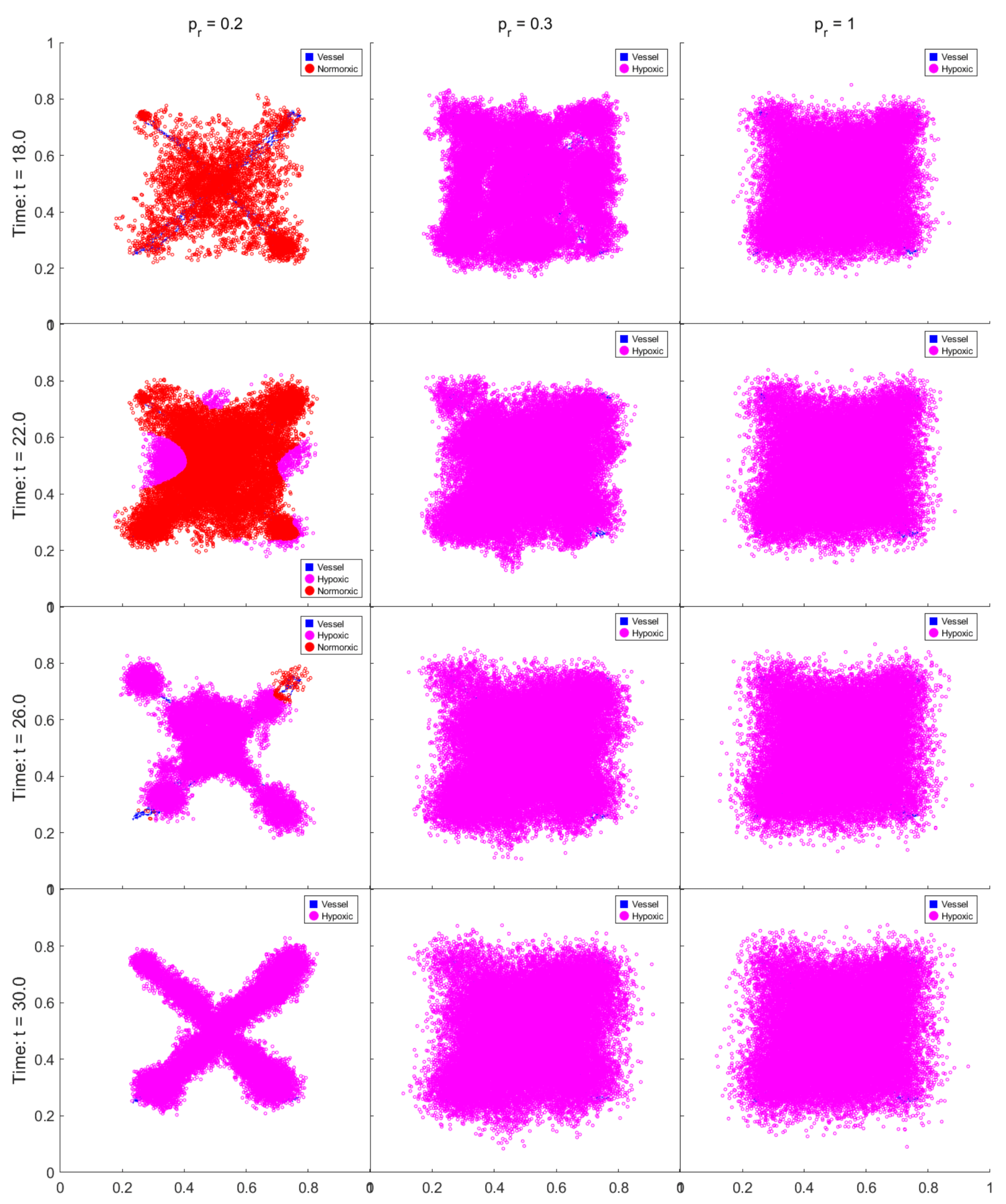

3.5. Passive and Active Resistance Mechanisms

3.6. Comparative Strategy Evolution

4. Biological Implications and Future Directions

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PDE | Partial differential equation |

| ABM | Agent-based model |

| TME | Tumor microenvironment |

| TAF | Tumor angiogenic factor |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

| HIF- | Hypoxia-inducible factor |

| HDC | Hybrid discrete-continuous |

| ADI | Alternating direction implicit |

| EGFR | Epidermal growth factor receptor |

| NSCLC | Non-small cell lung cancer |

| PI3K | Phosphoinositide 3-kinase |

| AKT | Protein kinase B |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| ODE | Ordinary differential equation |

| PTEN | Phosphatase and tensin homolog |

| DCE-MRI | dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging |

References

- Vogel, A.; Meyer, T.; Sapisochin, G.; Salem, R.; Saborowski, A. Hepatocellular carcinoma. The Lancet 2022, 400, 1345–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbeck, N.; Gnant, M. Breast cancer. The Lancet 2017, 389, 1134–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordhandas, S.; Zammarrelli, W.A.; Rios-Doria, E.V.; Green, A.K.; Makker, V. Current Evidence-Based Systemic Therapy for Advanced and Recurrent Endometrial Cancer. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network 2023, 21, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaseb, A.O.; Hasanov, E.; Cao, H.S.T.; Xiao, L.; Vauthey, J.N.; Lee, S.S.; Yavuz, B.G.; Mohamed, Y.I.; Qayyum, A.; Jindal, S.; et al. Perioperative nivolumab monotherapy versus nivolumab plus ipilimumab in resectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised, open-label, phase 2 trial. The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2022, 7, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, C.; Hagopian, G.; Nagasaka, M. Neoadjuvant therapy in non-small cell lung cancer. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology 2023, 190, 104080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyth, E.C.; Nilsson, M.; Grabsch, H.I.; Van Grieken, N.C.; Lordick, F. Gastric cancer. The Lancet 2020, 396, 635–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenova, Y.; Burkitbayev, Z.; Kalibekov, N.; Digay, A.; Zhaxybayev, B.; Shatkovskaya, O.; Khamzina, S.; Zharlyganova, D.; Kuanysh, Z.; Manatova, A. The Evolving Role of Chemotherapy in the Management of Pleural Malignancies: Current Evidence and Future Directions. Cancers 2025, 17, 2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, P.; Jiang, J.; Zhou, L.; Huang, Z.; Nice, E.C.; Huang, C.; Fu, L. Mitochondrial adaptation in cancer drug resistance: prevalence, mechanisms, and management. Journal of Hematology & Oncology 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, A.C.; Richiardone, E.; Jorge, J.; Polónia, B.; Xavier, C.P.; Salaroglio, I.C.; Riganti, C.; Vasconcelos, M.H.; Corbet, C.; Sarmento-Ribeiro, A.B. Impact of cancer metabolism on therapy resistance – Clinical implications. Drug Resistance Updates 2021, 59, 100797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holohan, C.; Van Schaeybroeck, S.; Longley, D.B.; Johnston, P.G. Cancer drug resistance: an evolving paradigm. Nature Reviews Cancer 2013, 13, 714–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boulos, J.C.; Yousof Idres, M.R.; Efferth, T. Investigation of cancer drug resistance mechanisms by phosphoproteomics. Pharmacological Research 2020, 160, 105091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malla, R.; Bhamidipati, P.; Samudrala, A.S.; Nuthalapati, Y.; Padmaraju, V.; Malhotra, A.; Rolig, A.S.; Malhotra, S.V. Exosome-Mediated Cellular Communication in the Tumor Microenvironment Imparts Drug Resistance in Breast Cancer. Cancers 2025, 17, 1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skourti, E.; Seip, K.; Mensali, N.; Jabeen, S.; Juell, S.; ynebråten, I.; Pettersen, S.; Engebraaten, O.; Corthay, A.; Inderberg, E.M.; et al. Chemoresistant tumor cell secretome potentiates immune suppression in triple negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Research 2025, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, C.; Mei, Y.; Zhong, W.; Fan, W.; Liu, L.; Feng, Z.; Bai, X.; Liu, C.; Xiao, M.; et al. Irinotecan alleviates chemoresistance to anthracyclines through the inhibition of AARS1-mediated BLM lactylation and homologous recombination repair. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2025, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Yang, C.; Li, J.; Wang, R.; Min, J.; Song, Y.; Su, H. The type I collagen paradox in PDAC progression: microenvironmental protector turned tumor accomplice. Journal of Translational Medicine 2025, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saha, S.; Bhat, A.; Kukal, S.; Phalak, M.; Kumar, S. Spatial heterogeneity in glioblastoma: Decoding the role of perfusion. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Reviews on Cancer 2025, 1880, 189383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belotti, D.; Pinessi, D.; Taraboletti, G. Alternative Vascularization Mechanisms in Tumor Resistance to Therapy. Cancers 2021, 13, 1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altrock, P.M.; Liu, L.L.; Michor, F. The mathematics of cancer: integrating quantitative models. Nature Reviews Cancer 2015, 15, 730–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, A.; Moes, D.J.A.; Van Hasselt, J.G.; Swen, J.J.; Guchelaar, H.J. A Review of Mathematical Models for Tumor Dynamics and Treatment Resistance Evolution of Solid Tumors. CPT: Pharmacometrics & Systems Pharmacology 2019, 8, 720–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Hu, B. Mathematical modeling and computational prediction of cancer drug resistance. Briefings in Bioinformatics 2018, 19, 1382–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, A.; Kohandel, M.; Clairambault, J. Integrating Biological and Mathematical Models to Explain and Overcome Drug Resistance in Cancer, Part 2: from Theoretical Biology to Mathematical Models. Current Stem Cell Reports 2017, 3, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhao, T.; Hu, Y.; Ren, S.; Tian, T. Mathematical Modelling and Bioinformatics Analyses of Drug Resistancefor Cancer Treatment. Current Bioinformatics 2024, 19, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picco, N.; Sahai, E.; Maini, P.K.; Anderson, A.R. Integrating Models to Quantify Environment-Mediated Drug Resistance. Cancer Research 2017, 77, 5409–5418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevertz, J.L.; Aminzare, Z.; Norton, K.A.; Perez-Velazquez, J.; Volkening, A.; Rejniak, K.A. Emergence of Anti-Cancer Drug Resistance: Exploring the Importance of the Microenvironmental Niche via a Spatial Model, 2014. Version Number; 1. [CrossRef]

- Flandoli, F.; Leocata, M.; Ricci, C. The Mathematical modeling of Cancer growth and angiogenesis by an individual based interacting system. Journal of Theoretical Biology 2023, 562, 111432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Yu, J.; Liu, Y.; Xie, L.; Hu, F.; Liu, H. Hypoxia-driven angiogenesis and metabolic reprogramming in vascular tumors. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, M.; Xu, P.; Cheng, R.; Li, N.; Cao, S.; Guo, Q.; Wang, X.; Li, C.; Bai, N.; Jiang, B.; et al. ROS-ATM-CHK2 axis stabilizes HIF-1α and promotes tumor angiogenesis in hypoxic microenvironment. Oncogene 2025, 44, 1609–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rankin, E.B.; Giaccia, A.J. The role of hypoxia-inducible factors in tumorigenesis. Cell Death & Differentiation 2008, 15, 678–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billy, F.; Ribba, B.; Saut, O.; Morre-Trouilhet, H.; Colin, T.; Bresch, D.; Boissel, J.P.; Grenier, E.; Flandrois, J.P. A pharmacologically based multiscale mathematical model of angiogenesis and its use in investigating the efficacy of a new cancer treatment strategy. Journal of Theoretical Biology 2009, 260, 545–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, T.L.; Byrne, H.M. A mathematical model to study the effects of drug resistance and vasculature on the response of solid tumors to chemotherapy. Mathematical Biosciences 2000, 164, 17–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodzioch, M.; Bajger, P.; Foryś, U. Angiogenesis and chemotherapy resistance: optimizing chemotherapy scheduling using mathematical modeling. Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology 2021, 147, 2281–2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Bao, J.; Shao, Y. Mathematical Modeling of Therapy-induced Cancer Drug Resistance: Connecting Cancer Mechanisms to Population Survival Rates. Scientific Reports 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spill, F.; Guerrero, P.; Alarcon, T.; Maini, P.K.; Byrne, H.M. Mesoscopic and continuum modelling of angiogenesis. Journal of Mathematical Biology 2015, 70, 485–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balding, D.; McElwain, D. A mathematical model of tumour-induced capillary growth. Journal of Theoretical Biology 1985, 114, 53–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, H.M.; Chaplain, M.A.J. Mathematical models for tumour angiogenesis: Numerical simulations and nonlinear wave solutions. Bulletin of Mathematical Biology 1995, 57, 461–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, J.D. Mathematical biology. 1: An introduction; Number 17 in Interdisciplinary applied mathematics, Springer-Verlag GmbH: Berlin Heidelberg, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Giverso, C.; Ciarletta, P. Tumour angiogenesis as a chemo-mechanical surface instability. Scientific Reports 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norton, K.A.; Gong, C.; Jamalian, S.; Popel, A.S. Multiscale Agent-Based and Hybrid Modeling of the Tumor Immune Microenvironment. Processes 2019, 7, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, J.; Robertson-Tessi, M.; Anderson, A.R. Agent-based methods facilitate integrative science in cancer. Trends in Cell Biology 2023, 33, 300–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biomathematics Laboratory, Department of Applied Mathematics, School of Mathematical Science, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran. .; Jamali, Y. Modeling the Immune System Through Agent-based Modeling: A Mini-review. Immunoregulation 2024, 6, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picco, N.; Milne, A.; Maini, P.; Anderson, A. The role of environmentally mediated drug resistance in facilitating the spatial distribution of residual disease., 2024. [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Lin, H.; Sun, X. Multiscale modeling of drug resistance in glioblastoma with gene mutations and angiogenesis. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal 2023, 21, 5285–5295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapidus, I.; Schiller, R. Model for the chemotactic response of a bacterial population. Biophysical Journal 1976, 16, 779–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauffenburger, D.; Kennedy, C.R.; Aris, R. Traveling bands of chemotactic bacteria in the context of population growth. Bulletin of Mathematical Biology 1984, 46, 19–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherratt, J.A. Chemotaxis and chemokinesis in eukaryotic cells: The Keller-Segel equations as an approximation to a detailed model. Bulletin of Mathematical Biology 1994, 56, 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodward, D.; Tyson, R.; Myerscough, M.; Murray, J.; Budrene, E.; Berg, H. Spatio-temporal patterns generated by Salmonella typhimurium. Biophysical Journal 1995, 68, 2181–2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsen, L.; Sherratt, J.A.; Maini, P.K.; Arnold, F. A mathematical model for the capillary endothelial cell-extracellular matrix interactions in wound-healing angiogenesis. IMA journal of mathematics applied in medicine and biology 1997, 14, 261–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melicow, M.M. The three steps to cancer: A new concept of cancerigenesis. Journal of Theoretical Biology 1982, 94, 471–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mac Gabhann, F.; Popel, A.S. Differential binding of VEGF isoforms to VEGF receptor 2 in the presence of neuropilin-1: a computational model. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology 2005, 288, H2851–H2860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addison-Smith, B.; McElwain, D.; Maini, P. A simple mechanistic model of sprout spacing in tumour-associated angiogenesis. Journal of Theoretical Biology 2008, 250, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A spatial model of tumor-host interaction: Application of chemotherapy. Mathematical Biosciences and Engineering 2009, 6, 521–546. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, A. Continuous and Discrete Mathematical Models of Tumor-induced Angiogenesis. Bulletin of Mathematical Biology 1998, 60, 857–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, G.H.; Fatt, I.; Goldstick, T.K. Oxygen Consumption Rate of Tissue Measured by a Micropolarographic Method. The Journal of General Physiology 1966, 50, 317–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A Hybrid Multiscale Model of Solid Tumour Growth and Invasion: Evolution and the Microenvironment. Single-Cell-Based Models in Biology and Medicine; Birkhäuser Basel: Basel, 2007; pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmielecki, J.; Foo, J.; Oxnard, G.R.; Hutchinson, K.; Ohashi, K.; Somwar, R.; Wang, L.; Amato, K.R.; Arcila, M.; Sos, M.L.; et al. Optimization of Dosing for EGFR-Mutant Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer with Evolutionary Cancer Modeling. Science Translational Medicine 2011, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chignola, R.; Foroni, R.; Franceschi, A.; Pasti, M.; Candiani, C.; Anselmi, C.; Fracasso, G.; Tridente, G.; Colombatti, M. Heterogeneous response of individual multicellular tumour spheroids to immunotoxins and ricin toxin. British Journal of Cancer 1995, 72, 607–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demicheli, R.; Pratesi, G.; Foroni, R. The Exponential-Gompertzian Tumor Growth Model: Data from Six Tumor Cell Lines in Vitro and in Vivo. Estimate of the Transition point from Exponential to Gompertzian Growth and Potential Cinical Implications. Tumori Journal 1991, 77, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twentyman, P.R. Response to chemotherapy of EMT6 spheroids as measured by growth delay and cell survival. British Journal of Cancer 1980, 42, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakuma, J. Cell kinetics of human squamous cell carcinomas in the oral cavity. The Bulletin of Tokyo Medical and Dental University 1980, 27, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wilson, G.; McNally, N.; Dische, S.; Saunders, M.; Des Rochers, C.; Lewis, A.; Bennett, M. Measurement of cell kinetics in human tumours in vivo using bromodeoxyuridine incorporation and flow cytometry. British Journal of Cancer 1988, 58, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chignola, R.; Foroni, R. Estimating the Growth Kinetics of Experimental Tumors From as Few as Two Determinations of Tumor Size: Implications for Clinical Oncology. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 2005, 52, 808–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miles, B.; Tadi, P. Genetics, Somatic Mutation. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, A.; Sleeman, B.; Young, I.; Griffiths, B. Nematode movement along a chemical gradient in a structurally heterogeneous environment : 2. Theory. Fundamental and Applied Nematology 1997, 20, 165–172. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, A.R.A. A hybrid mathematical model of solid tumour invasion: the importance of cell adhesion. Mathematical Medicine and Biology: A Journal of the IMA 2005, 22, 163–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, K.W.; Mayers, D.F. Numerical solution of partial differential equations: an introduction; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge ; New York, 1994.

- Pillay, S.; Byrne, H.M.; Maini, P.K. Modeling angiogenesis: A discrete to continuum description. Physical Review E 2017, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, L.; Yan, W.; Zhu, L.; Tang, C.; Wang, G. The role of blood flow in vessel remodeling and its regulatory mechanism during developmental angiogenesis. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 2023, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, M.A. Evolutionary dynamics: exploring the equations of life; Belknap Press of Harvard University Press: Cambridge, Mass, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Araten, D.J.; Golde, D.W.; Zhang, R.H.; Thaler, H.T.; Gargiulo, L.; Notaro, R.; Luzzatto, L. A Quantitative Measurement of the Human Somatic Mutation Rate. Cancer Research 2005, 65, 8111–8117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godin-Heymann, N.; Bryant, I.; Rivera, M.N.; Ulkus, L.; Bell, D.W.; Riese, D.J.; Settleman, J.; Haber, D.A. Oncogenic Activity of Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Kinase Mutant Alleles Is Enhanced by the T790M Drug Resistance Mutation. Cancer Research 2007, 67, 7319–7326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulloy, R.; Ferrand, A.; Kim, Y.; Sordella, R.; Bell, D.W.; Haber, D.A.; Anderson, K.S.; Settleman, J. Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Mutants from Human Lung Cancers Exhibit Enhanced Catalytic Activity and Increased Sensitivity to Gefitinib. Cancer Research 2007, 67, 2325–2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Fan, W.; Liu, Z.; Xiao, H.; Wu, J.; Tang, R.; Tu, J.; Qiao, L.; Huang, F.; Xie, W.; et al. Adjuvant Transarterial Chemoembolization With Sorafenib for Portal Vein Tumor Thrombus: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Surgery 2024, 159, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.W.; Kim, J.S.; Choi, W.M.; Choi, J.; Lee, D.; Shim, J.H.; Lim, Y.S.; Lee, H.C.; Kim, K.M. Synergistic Effects of Transarterial Chemoembolization and Lenvatinib on HIF-1α Ubiquitination and Prognosis Improvement in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Clinical Cancer Research 2025, 31, 2046–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathematical Modeling of the Metastatic Process. Experimental Metastasis: Modeling and Analysis; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 2013; pp. 189–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franssen, L.C.; Lorenzi, T.; Burgess, A.E.F.; Chaplain, M.A.J. A Mathematical Framework for Modelling the Metastatic Spread of Cancer. Bulletin of Mathematical Biology 2019, 81, 1965–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, M.H.R.; Wong, C.C.L. Hypoxia, Metabolic Reprogramming, and Drug Resistance in Liver Cancer. Cells 2021, 10, 1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Zhang, X.; Wang, W.; Li, X.; Sun, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Q.; Li, Y.; Hu, F.; Ren, H. Metabolic reprogramming and therapeutic resistance in primary and metastatic breast cancer. Molecular Cancer 2024, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mashouri, L.; Yousefi, H.; Aref, A.R.; Ahadi, A.M.; Molaei, F.; Alahari, S.K. Exosomes: composition, biogenesis, and mechanisms in cancer metastasis and drug resistance. Molecular Cancer 2019, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiau, C.; Cao, J.; Gong, D.; Gregory, M.T.; Caldwell, N.J.; Yin, X.; Cho, J.W.; Wang, P.L.; Su, J.; Wang, S.; et al. Spatially resolved analysis of pancreatic cancer identifies therapy-associated remodeling of the tumor microenvironment. Nature Genetics 2024, 56, 2466–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibue, T.; Weinberg, R.A. EMT, CSCs, and drug resistance: the mechanistic link and clinical implications. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology 2017, 14, 611–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Song, X.; Xu, D.; Tiek, D.; Goenka, A.; Wu, B.; Sastry, N.; Hu, B.; Cheng, S.Y. Stem cell programs in cancer initiation, progression, and therapy resistance. Theranostics 2020, 10, 8721–8743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylianopoulos, T.; Munn, L.L.; Jain, R.K. Reengineering the Physical Microenvironment of Tumors to Improve Drug Delivery and Efficacy: From Mathematical Modeling to Bench to Bedside. Trends in Cancer 2018, 4, 292–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadipour, M.; Momeni, M.M.; Soltani, M. Effect of hydraulic conductivity and permeability on drug distribution, an investigation based on a part of a real tissue, 2023. Version Number; 1. [CrossRef]

- Welter, M.; Rieger, H. Interstitial Fluid Flow and Drug Delivery in Vascularized Tumors: A Computational Model. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e70395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pink, D.B.S.; Schulte, W.; Parseghian, M.H.; Zijlstra, A.; Lewis, J.D. Real-Time Visualization and Quantitation of Vascular Permeability In Vivo: Implications for Drug Delivery. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e33760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nandigama, R.; Upcin, B.; Aktas, B.H.; Ergün, S.; Henke, E. Restriction of drug transport by the tumor environment. Histochemistry and Cell Biology 2018, 150, 631–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu Lila, A.S.; Matsumoto, H.; Doi, Y.; Nakamura, H.; Ishida, T.; Kiwada, H. Tumor-type-dependent vascular permeability constitutes a potential impediment to the therapeutic efficacy of liposomal oxaliplatin. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics 2012, 81, 524–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, S.; Wong, A.H.K.; Jain, R.K. Vascular Normalization as a Therapeutic Strategy for Malignant and Nonmalignant Disease. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine 2012, 2, a006486–a006486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gremonprez, F.; Descamps, B.; Izmer, A.; Vanhove, C.; Vanhaecke, F.; De Wever, O.; Ceelen, W. Pretreatment with VEGF(R)-inhibitors reduces interstitial fluid pressure, increases intraperitoneal chemotherapy drug penetration, and impedes tumor growth in a mouse colorectal carcinomatosis model. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 29889–29900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powathil, G.; Kohandel, M.; Milosevic, M.; Sivaloganathan, S. Modeling the Spatial Distribution of Chronic Tumor Hypoxia: Implications for Experimental and Clinical Studies. Computational and Mathematical Methods in Medicine 2012, 2012, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, R.K.; Martin, J.D.; Stylianopoulos, T. The Role of Mechanical Forces in Tumor Growth and Therapy. Annual Review of Biomedical Engineering 2014, 16, 321–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Maar, J.S.; Sofias, A.M.; Porta Siegel, T.; Vreeken, R.J.; Moonen, C.; Bos, C.; Deckers, R. Spatial heterogeneity of nanomedicine investigated by multiscale imaging of the drug, the nanoparticle and the tumour environment. Theranostics 2020, 10, 1884–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Huang, J.; Gao, S.; Jin, H.; He, J. A temporo-spatial pharmacometabolomics method to characterize pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in the brain microregions by using ambient mass spectrometry imaging. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B 2022, 12, 3341–3353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Randall, E.C.; Emdal, K.B.; Laramy, J.K.; Kim, M.; Roos, A.; Calligaris, D.; Regan, M.S.; Gupta, S.K.; Mladek, A.C.; Carlson, B.L.; et al. Integrated mapping of pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in a patient-derived xenograft model of glioblastoma. Nature Communications 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Lu, H.; Liu, A.; Weng, J.; Gan, L.; Zhou, L.; Ding, X.; Li, S. TRANS: a prediction model for EGFR mutation status in NSCLC based on radiomics and clinical features. Respiratory Research 2025, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arledge, C.A.; Zhao, A.H.; Topaloglu, U.; Zhao, D. Dynamic Contrast Enhanced MRI Mapping of Vascular Permeability for Evaluation of Breast Cancer Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Response Using Image-to-Image Conditional Generative Adversarial Networks, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Ferrier, M.C.; Sarin, H.; Fung, S.H.; Schatlo, B.; Pluta, R.M.; Gupta, S.N.; Choyke, P.L.; Oldfield, E.H.; Thomasson, D.; Butman, J.A. Validation of Dynamic Contrast-Enhanced Magnetic Resonance Imaging-Derived Vascular Permeability Measurements Using Quantitative Autoradiography in the RG2 Rat Brain Tumor Model. Neoplasia 2007, 9, 546–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagher-Ebadian, H.; Brown, S.L.; Ghassemi, M.M.; Nagaraja, T.N.; Valadie, O.G.; Acharya, P.C.; Cabral, G.; Divine, G.; Knight, R.A.; Lee, I.Y.; et al. Dynamic contrast enhanced (DCE) MRI estimation of vascular parameters using knowledge-based adaptive models. Scientific Reports 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Field | Diffusion | Decay | Uptake | Supply |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | None | None | None | |

| c | from hypoxic cells | |||

| d | at vessels | |||

| o |

| Symbol | Quantity | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| L | Length | Spatial extent of parent vessel to tumor distance |

| Time | Typical diffusion timescale / cell cycle duration | |

| , , , | Field concentrations | Normalization of PDE variables |

| Parameter | Meaning |

|---|---|

| PDE-related parameters | |

| Diffusion coefficients of endothelial cells (n), TAF (c), drug (d), and oxygen (o) | |

| Chemotactic sensitivity coefficient | |

| Saturation parameter for chemotaxis | |

| Natural decay rates of TAF, drug, and oxygen, respectively | |

| Cellular uptake rates of drug and oxygen | |

| Vessel supply rates of drug and oxygen | |

| TAF production rate by hypoxic cells and uptake rate by endothelial cells | |

| Indicator functions for tumor agents and vessel locations | |

| ABM-related parameters | |

| , , , , | Sets of all tumor cells, normoxic tumor cells, hypoxic tumor cells, vessel cells, and endothelial tip cells at time t |

| Angiogenic network at time t | |

| , | Lineage identifiers for tumor and endothelial tip cells |

| , , | Spatial coordinates of agents , , at time t |

| , , , , , | Local oxygen, drug level, accumulated DNA damage, death threshold, age, and maturation time for tumor cell |

| Age of endothelial tip cell | |

| Cellular radius | |

| Mutation intensity for the Poisson process | |

| DNA damage repair or clearance rate | |

| Tumor cell motility coefficient | |

| Maximum oxygen concentration | |

| Hypoxia threshold and apoptosis threshold for oxygen concentration | |

| Probabilities of endothelial cell remaining stationary or moving left, right, down, or up | |

| Minimum age required for tip branching | |

| Branching intensity coefficient | |

| Death thresholds for sensitive and resistant tumor cells | |

| Multiplicative factor defining resistance death threshold () | |

| Tumor cell cycle duration | |

| Proliferation rate of normoxic tumor cells | |

| Crowding threshold above which proliferation is suppressed | |

| Treatment-on and drug holiday durations | |

| PDE-related parameters | |

| Non-dimensionalization parameters | |

| L | Characteristic length scale |

| Characteristic time scale | |

| Reference field concentrations used for normalization | |

| Parameter | Description | D-value (SI units) | ND-value | Source / Justification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial discretization | (n/a) | 0.005 | Calculated | |

| Temporal discretization | (n/a) | 0.01 | Stability constraint | |

| Cellular influence radius | 0.005 | [48] | ||

| TAF diffusion coefficient | 0.12 | [49,50] | ||

| TAF decay rate | 0.002 | [29] | ||

| TAF production rate | [51] | |||

| TAF uptake rate | (n/a, nondimensionalized) | 0.1 | [52] | |

| Drug diffusion coefficient | (scaled) | 0.5 | Modeling choice | |

| Drug decay rate | (scaled) | 0.01 | [24] | |

| Drug uptake rate | (scaled) | 0.5 | [24] | |

| Drug supply rate | (scaled) | 2 | [24] | |

| Damage clearance rate | (scaled) | 0.2 | [24] | |

| Oxygen diffusion coefficient | 0.64 | [53] | ||

| Oxygen decay rate | 0.025 | [54] | ||

| Oxygen uptake rate | 34.39 | [24] | ||

| Oxygen supply rate | (calibrated) | 3.5 | Calibrated for model consistency | |

| Tumor motility intensity | (modeling choice) | 0.01 | Modeling choice | |

| Maximum oxygen concentration | 1 | [51] | ||

| Hypoxia threshold | (threshold setting) | 0.25 | [51] | |

| Apoptosis threshold | (threshold setting) | 0.05 | [51] | |

| Endothelial diffusion coefficient | [52] | |||

| Chemotaxis coefficient | 0.38 | [52] | ||

| Chemotaxis saturation parameter | (scaled) | 0.6 | [52] | |

| Branching age threshold | (scaled) | 0.5 | [52] | |

| Branching intensity coefficient | (scaled) | 1 | [25] | |

| Death threshold (sensitive cells) | (scaled) | 0.5 | [24] | |

| Death threshold ratio (resistant cells) | [55] | |||

| Cell cycle duration | 0.56–0.69 | [56,57,58,59,60,61] | ||

| Proliferation rate | Derived from | 1.0082–1.2323 | Derived | |

| Maximum neighbor cell count | (modeling choice) | 10 | [25] |

| Treatment | strategy | preexisting | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10 | 40 | 10 | pulsed | |||||

| 2 | 20 | 30 | 5 | pulsed | |||||

| 3 | 30 | 20 | pulsed | ||||||

| 4 | 40 | 10 | pulsed | ||||||

| 5 | 50 | 0 | 2 | continuous | |||||

| 6 | 50 | 0 | 5 | continuous | |||||

| 7 | 50 | 0 | 10 | continuous |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).