Submitted:

05 August 2025

Posted:

07 August 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

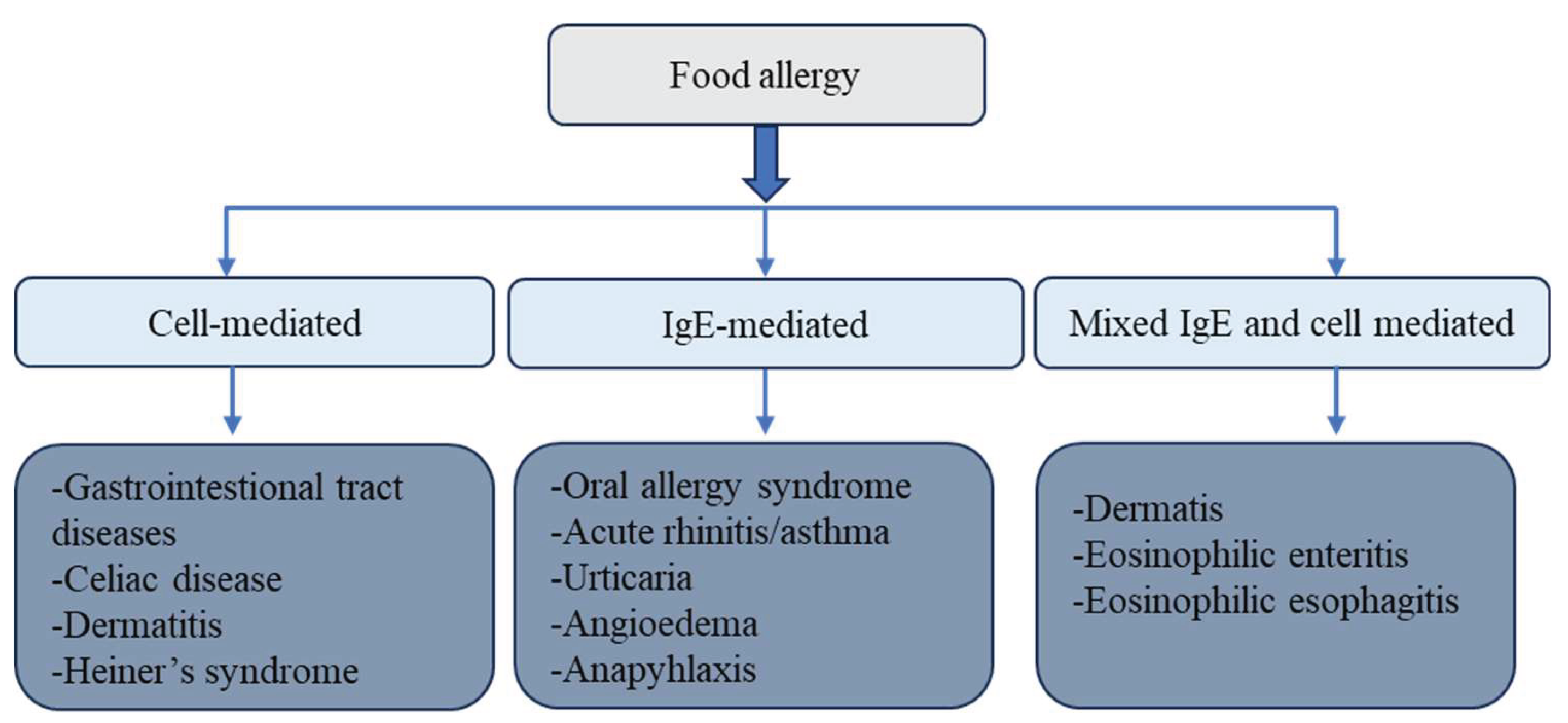

1. Food Allergy and Sensitization: Mechanisms, Pathways, and Risk Factors

- Adjuvant effects of food matrices: Nonallergenic components and microbial products in foods may act as immunological adjuvants, promoting sensitization [6].

2. Mitigation Strategies for Food Allergens

2.1. Allergen Elimination and Control Strategies

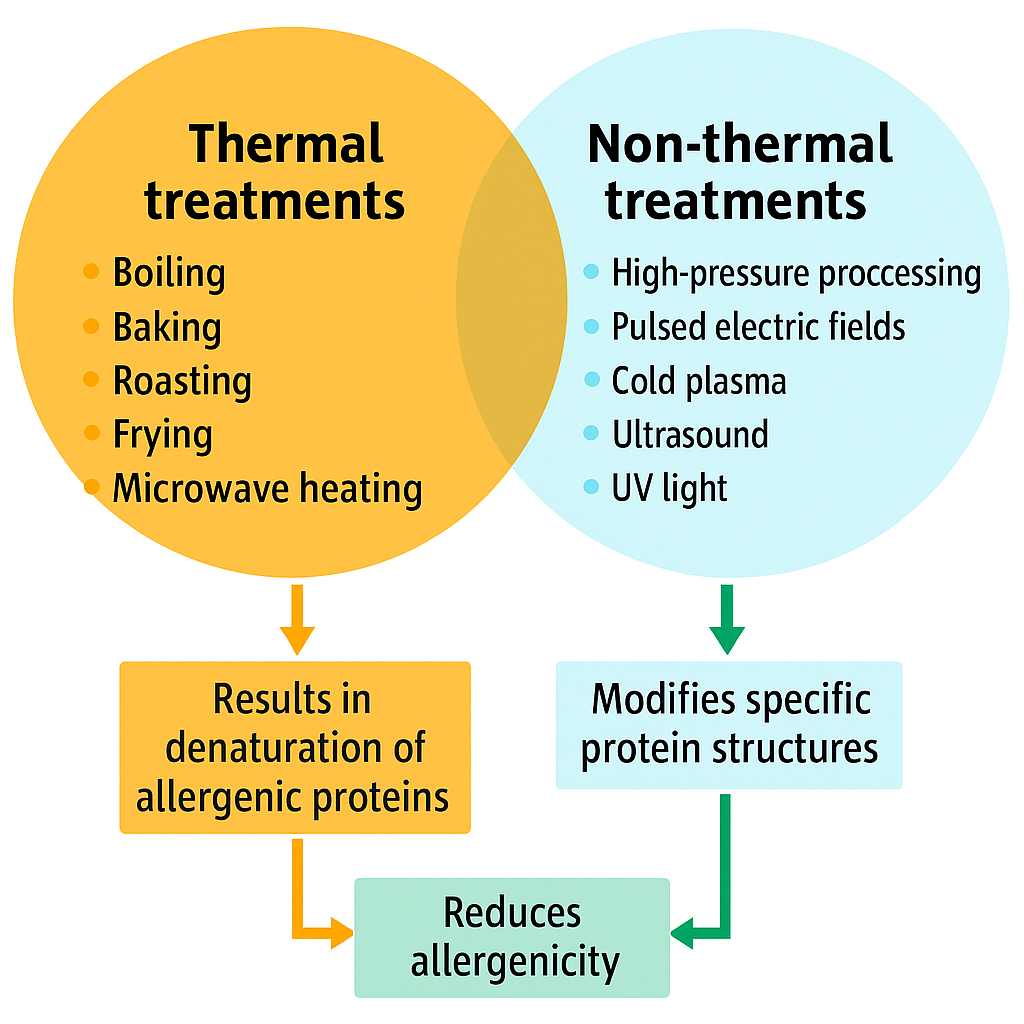

2.2. Effects of Food Processing on Allergen Control

2.3. Thermal Processing and Its Effects on Allergenicity

2.4. Non-Thermal Processing for Allergen Reduction

2.4.1. High Hydrostatic Pressure and Allergenicity in Foods

2.4.2. Pulsed Electric Fields (PEF) Technology and Its Impact on Food Allergenicity

2.4.3. Pulsed Ultraviolet (PUV) Light and Its Impact on Food Allergenicity

2.4.4. Gamma Irradiation and Its Impact on Food Allergenicity

2.4.5. High-Intensity Ultrasound and Its Impact on Food Allergenicity

2.4.6. Cold Plasma and Its Impact on Food Allergenicity

2.4.7. Genetic Modification and Its Role in Reducing Allergenicity

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sicherer, S.H. Clinical Implications of Cross-Reactive Food Allergens. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2001, 108, 881–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicherer, S.H.; Sampson, H.A. Food Allergy: Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2014, 133, 291–307.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renz, H.; Allen, K.J.; Sicherer, S.H.; Sampson, H.A.; Lack, G.; Beyer, K.; Oettgen, H.C. Food Allergy. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2018, 4, 17098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenta, R.; Hochwallner, H.; Linhart, B.; Pahr, S. Food Allergies: The Basics. Gastroenterology 2015, 148, 1120–1131.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breiteneder, H.; Ebner, C. Molecular and Biochemical Classification of Plant-Derived Food Allergens. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2000, 106, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiteneder, H.; Mills, E.N.C. Molecular Properties of Food Allergens. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2005, 115, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chehade, M.; Mayer, L. Oral Tolerance and Its Relation to Food Hypersensitivities. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2005, 115, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, K.-Y.; Tsai, C.-C.; Herbert Wu, C.H.; Lin, R.-H. Epicutaneous Exposure to Protein Antigen and Food Allergy. Clinical & Experimental Allergy 2003, 33, 1067–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lack, G. Update on Risk Factors for Food Allergy. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2012, 129, 1187–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittag, D.; Akkerdaas, J.; Ballmer-Weber, B.K.; Vogel, L.; Wensing, M.; Becker, W.-M.; Koppelman, S.J.; Knulst, A.C.; Helbling, A.; Hefle, S.L.; et al. Ara h 8, a Bet v 1–Homologous Allergen from Peanut, Is a Major Allergen in Patients with Combined Birch Pollen and Peanut Allergy. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2004, 114, 1410–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bischoff, S.; Crowe, S.E. Gastrointestinal Food Allergy: New Insights into Pathophysiology and Clinical Perspectives. Gastroenterology 2005, 128, 1089–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, H.A.; Sicherer, S.H.; Birnbaum, A.H. AGA Technical Review on the Evaluation of Food Allergy in Gastrointestinal Disorders. Gastroenterology 2001, 120, 1026–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sampson, H.A.; Anderson, J.A. Summary and Recommendations: Classification of Gastrointestinal Manifestations Due to Immunologic Reactions to Foods in Infants and Young Children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2000, 30 Suppl, S87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yocum, M.W.; Butterfield, J.H.; Klein, J.S.; Volcheck, G.W.; Schroeder, D.R.; Silverstein, M.D. Epidemiology of Anaphylaxis in Olmsted County: A Population-Based Study. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 1999, 104, 452–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, S.A.; Muñoz-Furlong, A.; Sampson, H.A. Fatalities Due to Anaphylactic Reactions to Foods. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2001, 107, 191–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badina, L.; Barbi, E.; Berti, I.; Radillo, O.; Matarazzo, L.; Ventura, A.; Longo, G. The Dietary Paradox in Food Allergy: Yesterday’s Mistakes, Today’s Evidence and Lessons for Tomorrow. Current Pharmaceutical Design 2012, 18, 5782–5787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Silva, R.; Dasanayake, W.M.D.K.; Wickramasinhe, G.D.; Karunatilake, C.; Weerasinghe, N.; Gunasekera, P.; Malavige, G.N. Sensitization to Bovine Serum Albumin as a Possible Cause of Allergic Reactions to Vaccines. Vaccine 2017, 35, 1494–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyce, J.A.; Assa’ad, A.; Burks, A.W.; Jones, S.M.; Sampson, H.A.; Wood, R.A.; Plaut, M.; Cooper, S.F.; Fenton, M.J.; Arshad, S.H.; et al. Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Food Allergy in the United States: Summary of the NIAID-Sponsored Expert Panel Report. Journal of Pediatric Nursing 2011, 26, e2–e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelman, F.D.; Boyce, J.A.; Vercelli, D.; Rothenberg, M.E. Key Advances in Mechanisms of Asthma, Allergy, and Immunology in 2009. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2010, 125, 312–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverstein, A.M. Clemens Freiherr von Pirquet: Explaining Immune Complex Disease in 1906. Nat Immunol 2000, 1, 453–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turk, J.L. Von Pirquet, Allergy and Infectious Diseases: A Review. J R Soc Med 1987, 80, 31–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmiere, C.; Comment, L.; Mangin, P. Allergic Reactions Following Contrast Material Administration: Nomenclature, Classification, and Mechanisms. Int J Legal Med 2014, 128, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kagan, R.S. Food Allergy: An Overview. Environmental Health Perspectives 2003, 111, 223–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molina, M.A.F.; Kram, Y.E.; Lanser, B.J. The Global Burden of Food Allergy. Immunology and Allergy Clinics 2025, 45, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stapel, S.O.; Kleine-Tebbe, J. Allergy Testing in the Laboratory. In Allergy and Allergic Diseases; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., 2008; pp. 1346–1367 ISBN 978-1-4443-0091-8.

- Schuppan, D.; Junker, Y.; Barisani, D. Celiac Disease: From Pathogenesis to Novel Therapies. Gastroenterology 2009, 137, 1912–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caubet, J.-C.; Ponvert, C. Vaccine Allergy. Immunology and Allergy Clinics 2014, 34, 597–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junker, Y.; Zeissig, S.; Kim, S.-J.; Barisani, D.; Wieser, H.; Leffler, D.A.; Zevallos, V.; Libermann, T.A.; Dillon, S.; Freitag, T.L.; et al. Wheat Amylase Trypsin Inhibitors Drive Intestinal Inflammation via Activation of Toll-like Receptor 4. J Exp Med 2012, 209, 2395–2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catassi, C.; Bai, J.C.; Bonaz, B.; Bouma, G.; Calabrò, A.; Carroccio, A.; Castillejo, G.; Ciacci, C.; Cristofori, F.; Dolinsek, J.; et al. Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity: The New Frontier of Gluten Related Disorders. Nutrients 2013, 5, 3839–3853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiter, B.; Shreffler, W.G. The Role of Dendritic Cells in Food Allergy. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2012, 129, 921–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badina, L.; Barbi, E.; Berti, I.; Radillo, O.; Matarazzo, L.; Ventura, A.; Longo, G. The Dietary Paradox in Food Allergy: Yesterday’s Mistakes, Today’s Evidence and Lessons for Tomorrow. Current Pharmaceutical Design 2012, 18, 5782–5787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burney, P.; Jarvis, D.; Perez-Padilla, R. The Global Burden of Chronic Respiratory Disease in Adults. The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease 2015, 19, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, S.; Lorentz, A. Obesity - A Promoter of Allergy? Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2013, 162, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, C.L.; Levin, M.E. Epidemiology of Food Allergy: Review Article. Current Allergy & Clinical Immunology 2014, 27, 170–176. [Google Scholar]

- Marrs, T.; Bruce, K.D.; Logan, K.; Rivett, D.W.; Perkin, M.R.; Lack, G.; Flohr, C. Is There an Association between Microbial Exposure and Food Allergy? A Systematic Review. Pediatric Allergy and Immunology 2013, 24, 311–320.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martino, D.; Neeland, M.; Dang, T.; Cobb, J.; Ellis, J.; Barnett, A.; Tang, M.; Vuillermin, P.; Allen, K.; Saffery, R. Epigenetic Dysregulation of Naive CD4+ T-Cell Activation Genes in Childhood Food Allergy. Nat Commun 2018, 9, 3308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strachan, D.P. Hay Fever, Hygiene, and Household Size. BMJ 1989, 299, 1259–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alm, B.; Åberg, N.; Erdes, L.; Möllborg, P.; Pettersson, R.; Norvenius, S.G.; Goksör, E.; Wennergren, G. Early Introduction of Fish Decreases the Risk of Eczema in Infants. Archives of Disease in Childhood 2009, 94, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGeady, S.J. Immunocompetence and Allergy. Pediatrics 2004, 113, 1107–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorburn, A.N.; Macia, L.; Mackay, C.R. Diet, Metabolites, and “Western-Lifestyle” Inflammatory Diseases. Immunity 2014, 40, 833–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenta, R. The Future of Antigen-Specific Immunotherapy of Allergy. Nat Rev Immunol 2002, 2, 446–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Kim, J.; Ahn, K. Food Allergy. Korean J Pediatr 2012, 55, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebner, C. Allergene. In Allergologie; Heppt, W., Renz, H., Röcken, M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 1998; ISBN 978-3-662-05660-8. [Google Scholar]

- Ebner, C.; Hoffmann-Sommergruber, K.; Breiteneder, H. Plant Food Allergens Homologous to Pathogenesis-Related Proteins. Allergy 2001, 56, 43–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortolani, C.; Ispano, M.; Ansaloni, R.; Rotondo, F.; Incorvaia, C.; Pastorello, E.A. Diagnostic Problems Due to Cross-reactions in Food Allergy. Allergy 1998, 53, 58–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortolani, C.; Pastorello, E.A. Food Allergies and Food Intolerances. Best Practice & Research Clinical Gastroenterology 2006, 20, 467–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asero, R.; Antonicelli, L. Does Sensitization to Foods in Adults Occur Always in the Gut? Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2011, 154, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartnikas, L.M.; Phipatanakul, W. Turning Up the Heat on Skin Testing for Baked Egg Allergy. Clin Exp Allergy 2013, 43, 1095–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noti, M.; Kim, B.S.; Siracusa, M.C.; Rak, G.D.; Kubo, M.; Moghaddam, A.E.; Sattentau, Q.A.; Comeau, M.R.; Spergel, J.M.; Artis, D. Exposure to Food Allergens through Inflamed Skin Promotes Intestinal Food Allergy through the Thymic Stromal Lymphopoietin–Basophil Axis. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2014, 133, 1390–1399.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astwood, J.D.; Leach, J.N.; Fuchs, R.L. Stability of Food Allergens to Digestion in Vitro. Nat Biotechnol 1996, 14, 1269–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groschwitz, K.R.; Hogan, S.P. Intestinal Barrier Function: Molecular Regulation and Disease Pathogenesis. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2009, 124, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irvine, A.D.; McLean, W.H.I.; Leung, D.Y.M. Filaggrin Mutations Associated with Skin and Allergic Diseases. New England Journal of Medicine 2011, 365, 1315–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrier, C.; Corthésy, B. Gut Permeability and Food Allergies. Clinical & Experimental Allergy 2011, 41, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, M.R.; Johansen, F.-E.; Kahu, H.; Macpherson, A.; Brandtzaeg, P. Hypersensitivity and Oral Tolerance in the Absence of a Secretory Immune System. Allergy 2010, 65, 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thyssen, J.P.; Linneberg, A.; Menné, T.; Johansen, J.D. The Epidemiology of Contact Allergy in the General Population – Prevalence and Main Findings. Contact Dermatitis 2007, 57, 287–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodo, H.W.; Konan, K.N.; Chen, F.C.; Egnin, M.; Viquez, O.M. Alleviating Peanut Allergy Using Genetic Engineering: The Silencing of the Immunodominant Allergen Ara h 2 Leads to Its Significant Reduction and a Decrease in Peanut Allergenicity. Plant Biotechnology Journal 2008, 6, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, E.N.C.; Sancho, A.I.; Rigby, N.M.; Jenkins, J.A.; Mackie, A.R. Impact of Food Processing on the Structural and Allergenic Properties of Food Allergens. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research 2009, 53, 963–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahaman, T.; Vasiljevic, T.; Ramchandran, L. Effect of Processing on Conformational Changes of Food Proteins Related to Allergenicity. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2016, 49, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, M.; Kopper, R.; Pons, L.; Abraham, E.C.; Burks, A.W.; Bannon, G.A. Protein Structure Plays a Critical Role in Peanut Allergen Stability and May Determine Immunodominant IgE-Binding Epitopes. J Immunol 2002, 169, 882–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.L. Food Allergies and Other Food Sensitivities. 2001, 55. 55.

- Crevel, R.W.R. 3 - Food Allergen Risk Assessment and Management. In Handbook of Food Allergen Detection and Control; Flanagan, S., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing Series in Food Science, Technology and Nutrition; Woodhead Publishing, 2015; pp. 41–66 ISBN 978-1-78242-012-5.

- Crevel, R.W.R.; Baumert, J.L.; Baka, A.; Houben, G.F.; Knulst, A.C.; Kruizinga, A.G.; Luccioli, S.; Taylor, S.L.; Madsen, C.B. Development and Evolution of Risk Assessment for Food Allergens. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2014, 67, 262–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crevel, R.W.R.; Baumert, J.L.; Luccioli, S.; Baka, A.; Hattersley, S.; Hourihane, J.O.; Ronsmans, S.; Timmermans, F.; Ward, R.; Chung, Y. Translating Reference Doses into Allergen Management Practice: Challenges for Stakeholders. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2014, 67, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, K.D.; Kronborg, C.; Larsen, J.N.; Dahl, R.; Gyrd-Hansen, D. Patient Related Outcomes in a Real Life Prospective Follow up Study: Allergen Immunotherapy Increase Quality of Life and Reduce Sick Days. World Allergy Organ J 2013, 6, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arora, R.; Kumar, A.; Singh, I.K.; Singh, A. Pathogenesis Related Proteins: A Defensin for Plants but an Allergen for Humans. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2020, 157, 659–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basant, N.; Jain, K.; Mittal, N.; Pandey, S.; Srivastava, V.; Pandey, K. ; Ayushi; Sharma, S.; Tiwari, N. Food Allergies and Their Management. In Traditional Foods; CRC Press, 2025 ISBN 978-1-00-351424-4.

- Cabanillas, B.; Novak, N. Effects of Daily Food Processing on Allergenicity. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2019, 59, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sathe, S.K.; Teuber, S.S.; Roux, K.H. Effects of Food Processing on the Stability of Food Allergens. Biotechnology Advances 2005, 23, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sathe, S.K.; Sharma, G.M. Effects of Food Processing on Food Allergens. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research 2009, 53, 970–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroghsbo, S.; Bøgh, K.L.; Rigby, N.M.; Mills, E.N.C.; Rogers, A.; Madsen, C.B. Sensitization with 7S Globulins from Peanut, Hazelnut, Soy or Pea Induces IgE with Different Biological Activities Which Are Modified by Soy Tolerance. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2011, 155, 212–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, J.L.; Kroghsbo, S.; Madsen, C.B.; Pozdnyakova, I.; Barkholt, V.; Bøgh, K.L. The Impact of Structural Integrity and Route of Administration on the Antibody Specificity against Three Cow’s Milk Allergens - a Study in Brown Norway Rats. Clin Transl Allergy 2014, 4, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, S.B.; Yang, B.-G.; Jang, G.; Kim, D.-Y.; Kim, J.; Oh, S.-M.; Oh, N.; Lee, S.; Moon, J.-Y.; Kim, J.-A.; et al. Combined IgE Neutralization and Bifidobacterium Longum Supplementation Reduces the Allergic Response in Models of Food Allergy. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 5669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, C.N.; Dupre, R.A.; Ebmeier, C.C.; Patil, S.; Smith, B.; Mattison, C.P. Heating Differentiates Pecan Allergen Stability: Car i 4 Is More Heat Labile Than Car i 1 and Car i 2. Food Science & Nutrition 2025, 13, e4747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Calvo, E.; García-García, A.; Madrid, R.; Martin, R.; García, T. From Polyclonal Sera to Recombinant Antibodies: A Review of Immunological Detection of Gluten in Foodstuff. Foods 2021, 10, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spies, J.R. Allergens. Available online: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/pdf/10.1021/jf60191a005 (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Malanin, K.; Lundberg, M.; Johansson, S.G.O. Anaphylactic Reaction Caused by Neoallergens in Heated Pecan Nut. Allergy 1995, 50, 988–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gayraud, J.; Mairesse, M.; Fontaine, J.F.; Thillay, A.; Leduc, V.; Rancé, F.; Parisot, L.; Moneret-Vautrin, D.A. The Prevalence of Sensitization to Lupin Flour in France and Belgium: A Prospective Study in 5,366 Patients, by the Allergy Vigilance Network.

- Abbring, S.; Xiong, L.; Diks, M.A.P.; Baars, T.; Garssen, J.; Hettinga, K.; Esch, B.C.A.M. van Loss of Allergy-Protective Capacity of Raw Cow’s Milk after Heat Treatment Coincides with Loss of Immunologically Active Whey Proteins. Food & Function 2020, 11, 4982–4993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hefle, S.L.; Taylor, S.L. Revealing and Diagnosing Food Allergies and Intolerances. Clinical Nutrition Insight 2005, 31, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Ehn, B.-M.; Ekstrand, B.; Bengtsson, U.; Ahlstedt, S. Modification of IgE Binding during Heat Processing of the Cow’s Milk Allergen β-Lactoglobulin. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 1398–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mine, Y.; Yang, M. Recent Advances in the Understanding of Egg Allergens: Basic, Industrial, and Clinical Perspectives. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 4874–4900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, S.J.; Schmitt, D.A.; Galeano, M.; Hurlburt, B.K. Comparison of the Digestibility of the Major Peanut Allergens in Thermally Processed Peanuts and in Pure Form. Foods 2014, 3, 290–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maleki, S.J.; Sathe, S.K. The Effects of Processing Methods on Allergenic Properties of Food Proteins. In Food Allergy; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., 2006; pp. 309–322 ISBN 978-1-68367-175-6.

- Verhoeckx, K.C.M.; Vissers, Y.M.; Baumert, J.L.; Faludi, R.; Feys, M.; Flanagan, S.; Herouet-Guicheney, C.; Holzhauser, T.; Shimojo, R.; van der Bolt, N.; et al. Food Processing and Allergenicity. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2015, 80, 223–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhisel-Broadbent, J.; Scanlon, S.M.; Sampson, H.A. Fish Hypersensitivity: I. In Vitro and Oral Challenge Results in Fish-Allergic Patients. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 1992, 89, 730–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemán, A.; Sastre, J.; Quirce, S.; de las Heras, M.; Carnés, J.; Fernández-Caldas, E.; Pastor, C.; Blázquez, A.B.; Vivanco, F.; Cuesta-Herranz, J. Allergy to Kiwi: A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Food Challenge Study in Patients from a Birch-Free Area. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2004, 113, 543–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiocchi, A.; Bouygue, G.R.; Albarini, M.; Restani, P. Molecular Diagnosis of Cow’s Milk Allergy. Current Opinion in Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2011, 11, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiocchi, A.; Pecora, V.; Petersson, C.J.; Dahdah, L.; Borres, M.P.; Amengual, M.J.; Huss-Marp, J.; Mazzina, O.; Di Girolamo, F. Sensitization Pattern to Inhalant and Food Allergens in Symptomatic Children at First Evaluation. Ital J Pediatr 2015, 41, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aalberse, R.C. Structural Biology of Allergens. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2000, 106, 228–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, K.; Herouet-Guicheney, C.; Ladics, G.; Bannon, G.; Cockburn, A.; Crevel, R.; Fitzpatrick, J.; Mills, C.; Privalle, L.; Vieths, S. Evaluating the Effect of Food Processing on the Potential Human Allergenicity of Novel Proteins: International Workshop Report. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2007, 45, 1116–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwan, M.; Vissers, Y.M.; Fiedorowicz, E.; Kostyra, H.; Kostyra, E.; Savelkoul, H.F.J.; Wichers, H.J. Impact of Maillard Reaction on Immunoreactivity and Allergenicity of the Hazelnut Allergen Cor a 11. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 7163–7171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vissers, Y.M.; Blanc, F.; Skov, P.S.; Johnson, P.E.; Rigby, N.M.; Przybylski-Nicaise, L.; Bernard, H.; Wal, J.-M.; Ballmer-Weber, B.; Zuidmeer-Jongejan, L.; et al. Effect of Heating and Glycation on the Allergenicity of 2S Albumins (Ara h 2/6) from Peanut. PLOS ONE 2011, 6, e23998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prabakaran, S.; Damodaran, S. Thermal Unfolding of β-Lactoglobulin: Characterization of Initial Unfolding Events Responsible for Heat-Induced Aggregation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1997, 45, 4303–4308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindslev-Jensen, C.; Skov, P.S.; Roggen, E.L.; Hvass, P.; Brinch, D.S. Investigation on Possible Allergenicity of 19 Different Commercial Enzymes Used in the Food Industry. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2006, 44, 1909–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopper, R.A.; Odum, N.J.; Sen, M.; Helm, R.M.; Stanley, J.S.; Burks, A.W. Peanut Protein Allergens: The Effect of Roasting on Solubility and Allergenicity. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2005, 136, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuo, K.; Hamajima, N.; Hirai, T.; Kato, T.; Koike, K.; Inoue, M.; Takezaki, T.; Tajima, K. Aldehyde Dehydrogenase 2(ALDH2)Genotype Affects Rectal Cancer Susceptibility Due to Alcohol Consumption. Journal of Epidemiology 2002, 12, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayuso, R.; Lehrer, S.B.; Tanaka, L.; Ibanez, M.D.; Pascual, C.; Burks, A.W.; Sussman, G.L.; Goldberg, B.; Lopez, M.; Reese, G. IgE Antibody Response to Vertebrate Meat Proteins Including Tropomyosin. Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology 1999, 83, 399–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varjonen, E.; Björkstén, F.; Savolainen, J. Stability of Cereal Allergens. Clinical & Experimental Allergy 1996, 26, 436–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posch, A.; Chen, Z.; Dunn, M.J.; Wheeler, C.H.; Petersen, A.; Leubner-Metzger, G.; Baur, X. Latex Allergen Database. Electrophoresis 1997, 18, 2803–2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werfel, S.J.; Cooke, S.K.; Sampson, H.A. Clinical Reactivity to Beef in Children Allergic to Cow’s Milk. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1997, 99, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, P.; Vieths, S.; Wangorsch, A.; Nerkamp, J.; Hofmann, T. Maillard Reaction and Enzymatic Browning Affect the Allergenicity of Pru Av 1, the Major Allergen from Cherry (Prunus Avium). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 4002–4007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, K.S.; Ballmer-Weber, B.K.; Lüttkopf, D.; Skov, P.S.; Wüthrich, B.; Bindslev-Jensen, C.; Vieths, S.; Poulsen, L.K. Roasted Hazelnuts – Allergenic Activity Evaluated by Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Food Challenge. Allergy 2003, 58, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, S.J.; Viquez, O.; Jacks, T.; Dodo, H.; Champagne, E.T.; Chung, S.-Y.; Landry, S.J. The Major Peanut Allergen, Ara h 2, Functions as a Trypsin Inhibitor, and Roasting Enhances This Function. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2003, 112, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanga, S.K.; Singh, A.; Raghavan, V. Review of Conventional and Novel Food Processing Methods on Food Allergens. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2017, 57, 2077–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pi, X.; Zhu, L.; Liu, J.; Zhang, B. Effect of Thermal Processing on Food Allergenicity: Mechanisms, Application, Influence Factor, and Future Perspective. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 20225–20240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khammeethong, T.; Phiriyangkul, P.; Inson, C.; Sinthuvanich, C. Effect of Microwave Vacuum Drying and Tray Drying on the Allergenicity of Protein Allergens in Edible Cricket, Gryllus Bimaculatus. Food Control 2024, 160, 110328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiocchi, A.; Restani, P.; Riva, E.; Mirri, G.P.; Santini, I.; Bernardo, L.; Galli, C.L. Heat Treatment Modifies the Allergenicity of Beef and Bovine Serum Albumin. Allergy 1998, 53, 798–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campus, M. High Pressure Processing of Meat, Meat Products and Seafood. Food Eng. Rev. 2010, 2, 256–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messens, W.; Van Camp, J.; Huyghebaert, A. The Use of High Pressure to Modify the Functionality of Food Proteins. Trends in Food Science & Technology 1997, 8, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tauscher, B. Pasteurization of Food by Hydrostatic High Pressure: Chemical Aspects. Z Lebensm Unters Forch 1995, 200, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Considine, K.M.; Kelly, A.L.; Fitzgerald, G.F.; Hill, C.; Sleator, R.D. High-Pressure Processing – Effects on Microbial Food Safety and Food Quality. FEMS Microbiol Lett 2008, 281, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhakal, S.; Liu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Roux, K.H.; Sathe, S.K.; Balasubramaniam, V.M. Effect of High Pressure Processing on the Immunoreactivity of Almond Milk. Food Research International 2014, 62, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba, F.J.; Esteve, M.J.; Frígola, A. High Pressure Treatment Effect on Physicochemical and Nutritional Properties of Fluid Foods During Storage: A Review. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety 2012, 11, 307–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicón, R.; Belloque, J.; Alonso, E.; López-Fandiño, R. Antibody Binding and Functional Properties of Whey Protein Hydrolysates Obtained under High Pressure. Food Hydrocolloids 2009, 23, 593–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heremans, K. The Effects of High Pressure on Biomaterials. In Ultra High Pressure Treatments of Foods; Hendrickx, M.E.G., Knorr, D., Ludikhuyze, L., Van Loey, A., Heinz, V., Eds.; Springer US: Boston, MA, 2001; ISBN 978-1-4615-0723-9. [Google Scholar]

- Peñas, E.; Préstamo, G.; Luisa Baeza, M.; Martínez-Molero, M.I.; Gomez, R. Effects of Combined High Pressure and Enzymatic Treatments on the Hydrolysis and Immunoreactivity of Dairy Whey Proteins. International Dairy Journal 2006, 16, 831–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleber, N.; Maier, S.; Hinrichs, J. Antigenic Response of Bovine β-Lactoglobulin Influenced by Ultra-High Pressure Treatment and Temperature. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies 2007, 8, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, T.; Katayama, E.; Matsubara, S.; Omi, Y.; Matsuda, T. Release of Allergenic Proteins from Rice Grains Induced by High Hydrostatic Pressure. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 3124–3129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odani, S.; Kanda, Y.; Hara, T.; Matuno, M.; Suzuki, A. Effects of High Hydrostatic Pressure Treatment on the Allergenicity and Structure of Chicken Egg White Ovomucoid. High Pressure Bioscience and Biotechnology, 2007, 1, 252–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.-S.; Tang, C.-H.; Li, B.-S.; Yang, X.-Q.; Li, L.; Ma, C.-Y. Effects of High-Pressure Treatment on Some Physicochemical and Functional Properties of Soy Protein Isolates. Food Hydrocolloids 2008, 22, 560–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akdemir Evrendilek, G. Chapter 14 - Pulsed Electric Field Processing: Food Pasteurization, Tissue Treatment, and Seed Disinfection. In Food Packaging and Preservation; Jaiswal, A.K., Shankar, S., Eds.; Academic Press, 2024; pp. 259–273 ISBN 978-0-323-90044-7.

- Barba, F.J.; Parniakov, O.; Pereira, S.A.; Wiktor, A.; Grimi, N.; Boussetta, N.; Saraiva, J.A.; Raso, J.; Martin-Belloso, O.; Witrowa-Rajchert, D.; et al. Current Applications and New Opportunities for the Use of Pulsed Electric Fields in Food Science and Industry. Food Research International 2015, 77, 773–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzimitakos, T.; Athanasiadis, V.; Kalompatsios, D.; Mantiniotou, M.; Bozinou, E.; Lalas, S.I. Pulsed Electric Field Applications for the Extraction of Bioactive Compounds from Food Waste and By-Products: A Critical Review. Biomass 2023, 3, 367–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarmush, M.L.; Golberg, A.; Serša, G.; Kotnik, T.; Miklavčič, D. Electroporation-Based Technologies for Medicine: Principles, Applications, and Challenges. Annual Review of Biomedical Engineering 2014, 16, 295–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evrendilek, G.A. Pulsed Electric Field Treatment for Beverage Production and Preservation; Springer International Publishing, 2017; ISBN 978-3-319-32886-7.

- Evrendilek, G.A. Influence of High Pressure Processing on Food Bioactives. In Retention of Bioactives. In Retention of Bioactives in Food Processing; Jafari, S.M., Capanoglu, E., Eds.; Food Bioactive Ingredients; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2022; ISBN 978-3-030-96885-4. [Google Scholar]

- Lebovka, N.; Vorobiev, E.; Chemat, F. Enhancing Extraction Processes in the Food Industry; CRC Press, 2016; ISBN 978-1-4398-4595-0.

- Toepfl, S.; Heinz, V.; Knorr, D. High Intensity Pulsed Electric Fields Applied for Food Preservation. Chemical Engineering and Processing: Process Intensification 2007, 46, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akdemir Evrendilek, G.; Tanriverdi, H.; Demir, I.; Uzuner, S. Shelf-Life Extension of Traditional Licorice Root “Sherbet” with a Novel Pulsed Electric Field Processing. Frontiers in Food Science and Technology 2023, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akdemir Evrendilek, G.; Hitit Özkan, B. Pulsed Electric Field Processing of Fruit Juices with Inactivation of Enzymes with New Inactivation Kinetic Model and Determination of Changes in Quality Parameters. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies 2024, 94, 103678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Loey, A.; Verachtert, B.; Hendrickx, M. Effects of High Electric Field Pulses on Enzymes. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2001, 12, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.-N.; Zeng, X.-A.; Tang, T.; Jiang, Z.; Liu, Y.-Y. Unfolding and Nanotube Formation of Ovalbumin Induced by Pulsed Electric Field. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies 2018, 45, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Yang, R. Comparative Study of Inactivation and Conformational Change of Lysozyme Induced by Pulsed Electric Fields and Heat. Eur Food Res Technol 2008, 228, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Yang, R. Effect of High-Intensity Pulsed Electric Fields on the Activity, Conformation and Self-Aggregation of Pepsin. Food Chemistry 2009, 114, 777–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Cai, M.; Cheng, J.-H.; Sun, D.-W. Effects of Electric Fields and Electromagnetic Wave on Food Protein Structure and Functionality: A Review. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2018, 75, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, Z.; Mo, H. Effects of Pulsed Electric Fields on Physicochemical Properties of Soybean Protein Isolates. LWT - Food Science and Technology 2007, 40, 1167–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Cheng, L.; Wang, L.; Guan, Z. Inactivation Effects of PEF on Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) and Pectinesterase (PE). IEEE Transactions on Plasma Science 2006, 34, 2630–2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, P.E.; Van der Plancken, I.; Balasa, A.; Husband, F.A.; Grauwet, T.; Hendrickx, M.; Knorr, D.; Mills, E.N.C.; Mackie, A.R. High Pressure, Thermal and Pulsed Electric-Field-Induced Structural Changes in Selected Food Allergens. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research 2010, 54, 1701–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobajas, A.P.; Agulló-García, A.; Cubero, J.L.; Colás, C.; Segura-Gil, I.; Sánchez, L.; Calvo, M.; Pérez, M.D. Effect of High Pressure and Pulsed Electric Field on Denaturation and Allergenicity of Pru p 3 Protein from Peach. Food Chemistry 2020, 321, 126745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.; Tu, Z.; Wang, H.; Zhang, L.; Gao, Y.; Li, X.; Tian, M. Immunogenic and Structural Properties of Ovalbumin Treated by Pulsed Electric Fields. International Journal of Food Properties 2017, 20, S3164–S3176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanga, S.K.; Singh, A.; Raghavan, V. Effect of Thermal and Electric Field Treatment on the Conformation of Ara h 6 Peanut Protein Allergen. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies 2015, 30, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanga, S.K.; Singh, A.; Kalkan, F.; Gariepy, Y.; Orsat, V.; Raghavan, V. Effect of Thermal and High Electric Fields on Secondary Structure of Peanut Protein. International Journal of Food Properties 2016, 19, 1259–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paschke, A. Aspects of Food Processing and Its Effect on Allergen Structure. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research 2009, 53, 959–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Lu, X.; Zeng, X.; Lin, S. Regulation of Ovalbumin Allergenicity and Structure-Activity Relationship Analysis Based on Pulsed Electric Field Technology. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024, 261, 129695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shriver, S.K.; Yang, W.W. Thermal and Nonthermal Methods for Food Allergen Control. Food Eng. Rev. 2011, 3, 26–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.-Y.; Yang, W.; Krishnamurthy, K. Effects of Pulsed UV-Light on Peanut Allergens in Extracts and Liquid Peanut Butter. Journal of Food Science 2008, 73, C400–C404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garvey, M.; Rowan, N. Pulsed UV as a Potential Surface Sanitizer in Food Production Processes to Ensure Consumer Safety. Current Opinion in Food Science 2019, 26, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-lópez, V.M. Continuous UV-C Light. In Decontamination of Fresh and Minimally Processed Produce; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., 2012; pp. 365–378 ISBN 978-1-118-22918-7.

- Gómez-López, V.M.; Koutchma, T.; Linden, K. Chapter 8 - Ultraviolet and Pulsed Light Processing of Fluid Foods. In Novel Thermal and Non-Thermal Technologies for Fluid Foods. In Novel Thermal and Non-Thermal Technologies for Fluid Foods; Cullen, P.J., Tiwari, B.K., Valdramidis, V.P., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, 2012; ISBN 978-0-12-381470-8. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamurthy, K.; Tewari, J.C.; Irudayaraj, J.; Demirci, A. Microscopic and Spectroscopic Evaluation of Inactivation of Staphylococcus Aureus by Pulsed UV Light and Infrared Heating. Food Bioprocess Technol 2010, 3, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorman, S.; McGlade, J.P.; Lambert, M.J.M.; Strickland, D.H.; Thomas, J.A.; Hart, P.H. UV Exposure and Protection against Allergic Airways Disease. Photochem Photobiol Sci 2010, 9, 571–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keklik, N.M.; Krishnamurthy, K.; Demirci, A. 12 - Microbial Decontamination of Food by Ultraviolet (UV) and Pulsed UV Light. In Microbial Decontamination in the Food Industry; Demirci, A., Ngadi, M.O., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing Series in Food Science, Technology and Nutrition; Woodhead Publishing, 2012; pp. 344–369 ISBN 978-0-85709-085-0.

- Yang, W.W.; Mwakatage, N.R.; Goodrich-Schneider, R.; Krishnamurthy, K.; Rababah, T.M. Mitigation of Major Peanut Allergens by Pulsed Ultraviolet Light. Food Bioprocess Technol 2012, 5, 2728–2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinlschmidt, P.; Ueberham, E.; Lehmann, J.; Reineke, K.; Schlüter, O.; Schweiggert-Weisz, U.; Eisner, P. The Effects of Pulsed Ultraviolet Light, Cold Atmospheric Pressure Plasma, and Gamma-Irradiation on the Immunoreactivity of Soy Protein Isolate. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies 2016, 38, 374–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tammineedi, C.V.R.K.; Choudhary, R.; Perez-Alvarado, G.C.; Watson, D.G. Determining the Effect of UV-C, High Intensity Ultrasound and Nonthermal Atmospheric Plasma Treatments on Reducing the Allergenicity of α-Casein and Whey Proteins. LWT - Food Science and Technology 2013, 54, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-W.; Kim, J.-H.; Yook, H.-S.; Kang, K.-O.; Lee, S.-Y.; Hwang, H.-J.; Byun, M.-W. Effects of Gamma Radiation on the Allergenic and Antigenic Properties of Milk Proteins. Journal of Food Protection 2001, 64, 272–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manzocco, L.; Panozzo, A.; Nicoli, M.C. Effect of Ultraviolet Processing on Selected Properties of Egg White. Food Chemistry 2012, 135, 522–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surowsky, B.; Schlüter, O.; Knorr, D. Interactions of Non-Thermal Atmospheric Pressure Plasma with Solid and Liquid Food Systems: A Review. Food Eng Rev 2015, 7, 82–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meza-Morales, W.; Estévez-Carmona, M.M.; Alvarez-Ricardo, Y.; Obregón-Mendoza, M.A.; Cassani, J.; Ramírez-Apan, M.T.; Escobedo-Martínez, C.; Soriano-García, M.; Reynolds, W.F.; Enríquez, R.G. Full Structural Characterization of Homoleptic Complexes of Diacetylcurcumin with Mg, Zn, Cu, and Mn: Cisplatin-Level Cytotoxicity in Vitro with Minimal Acute Toxicity in Vivo. Molecules 2019, 24, 1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shriver, S.; Yang, W.; Chung, S.-Y.; Percival, S. Pulsed Ultraviolet Light Reduces Immunoglobulin E Binding to Atlantic White Shrimp (Litopenaeus Setiferus) Extract. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2011, 8, 2569–2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Saiz, R.; Benedé, S.; Molina, E.; López-Expósito, I. Effect of Processing Technologies on the Allergenicity of Food Products. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2015, 55, 1902–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uesugi, A.R.; Danyluk, M.D.; Harris, L.J. Survival of Salmonella Enteritidis Phage Type 30 on Inoculated Almonds Stored at −20, 4, 23, and 35°C. Journal of Food Protection 2006, 69, 1851–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Beltrán, J.; Welti-Chanes, J.; Barbosa-Cánovas, G.V. Ultraviolet-C light processing of grape, cranberry and grapefruit juices to inactivate Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Journal of Food Process Engineering 2009, 32, 916–932. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1745-4530.2008.00253.x (accessed on 4 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Pathak, B.; Omre, P.K.; Bisht, B.; Saini, D. Effect of thermal and non-thermal processing methods on food allergens.

- Tolouie, H.; Mohammadifar, M.A.; Ghomi, H.; Hashemi, M. Cold Atmospheric Plasma Manipulation of Proteins in Food Systems. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2018, 58, 2583–2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shriver, S.K.; Yang, W.W. Thermal and Nonthermal Methods for Food Allergen Control. Food Eng. Rev. 2011, 3, 26–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz, A.F.M.; Souza, M.P.; Carneiro-da-Cunha, M.G.; Medeiros, P.L.; Melo, A.M.M.A.; Aguiar, J.S.; Silva, T.G.; Silva-Lucca, R.A.; Oliva, M.L.V.; Correia, M.T.S. Molecular Fragmentation of Wheat-Germ Agglutinin Induced by Food Irradiation Reduces Its Allergenicity in Sensitised Mice. Food Chemistry 2012, 132, 1033–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Hu, C.; Gao, J.; Li, X.; Wu, Z.; Yang, A.; Chen, H. A Potential Practical Approach to Reduce Ara h 6 Allergenicity by Gamma Irradiation. Food Chemistry 2013, 136, 1141–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, S.; Jang, D.-I.; Lee, J.-W.; Kim, J.-H.; Byun, M.-W.; Lee, S.-Y. Evaluation of Reduced Allergenicity of Irradiated Peanut Extract Using Splenocytes from Peanut-Sensitized Mice. Radiation Physics and Chemistry 2009, 78, 615–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhenxing, L.; Hong, L.; Limin, C.; Jamil, K. The Influence of Gamma Irradiation on the Allergenicity of Shrimp (Penaeus Vannamei). Journal of Food Engineering 2007, 79, 945–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaddouri, H.; Mimoun, S.; El-Mecherfi, K.E.; Chekroun, A.; Kheroua, O.; Saidi, D. Impact of γ-Radiation on Antigenic Properties of Cow’s Milk β-Lactoglobulin. Journal of Food Protection 2008, 71, 1270–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, M.; Venkatachalam, M.; Teuber, S.S.; Roux, K.H.; Sathe, S.K. Impact of γ-Irradiation and Thermal Processing on the Antigenicity of Almond, Cashew Nut and Walnut Proteins. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 2004, 84, 1119–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leszczynska, J.; Łącka, A.; Szemraj, J.; Lukamowicz, J.; Zegota, H. The Influence of Gamma Irradiation on the Immunoreactivity of Gliadin and Wheat Flour. Eur Food Res Technol 2003, 217, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.-H.; Kim, J.-H.; Lee, J.-W.; Yoo, Y.-C.; Kim, M.R.; Park, K.-S.; Byun, M.-W. Ovalbumin Modified by Gamma Irradiation Alters Its Immunological Functions and Allergic Responses. International Immunopharmacology 2007, 7, 464–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, K.J.; Delsignore, M.E. Protein Damage and Degradation by Oxygen Radicals. III. Modification of Secondary and Tertiary Structure. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1987, 262, 9908–9913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, M.-W.; Kim, J.-H.; Lee, J.-W.; Park, J.-W.; Hong, C.-S.; Kang, I.-J. Effects of Gamma Radiation on the Conformational and Antigenic Properties of a Heat-Stable Major Allergen in Brown Shrimp. Journal of Food Protection 2000, 63, 940–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.-H.; Lee, J.-W.; Lee, Y.-S.; Lee, S.-Y.; Kim, M.-R.; Yook, H.-S.; Byun, M.-W. Change of an Egg Allergen in a White Layer Cake Containing Gamma-Irradiated Egg White. Journal of Food Protection 2004, 67, 1725–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zhu, W.; Zeng, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, H.; Li, Z. Insight into the Mechanism of Allergenicity Decreasing in Recombinant Sarcoplasmic Calcium-Binding Protein from Shrimp (Litopenaeus Vannamei) with Thermal Processing via Spectroscopy and Molecular Dynamics Simulation Techniques. Food Research International 2022, 157, 111427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kume, T.; Furuta, M.; Todoriki, S.; Uenoyama, N.; Kobayashi, Y. Status of Food Irradiation in the World. Radiation Physics and Chemistry 2009, 78, 222–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piyasena, P.; Mohareb, E.; McKellar, R.C. Inactivation of Microbes Using Ultrasound: A Review. International Journal of Food Microbiology 2003, 87, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrapala, J.; Oliver, C.; Kentish, S.; Ashokkumar, M. Ultrasonics in Food Processing. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry 2012, 19, 975–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soria, A.C.; Villamiel, M. Effect of Ultrasound on the Technological Properties and Bioactivity of Food: A Review. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2010, 21, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemat, F.; Rombaut, N.; Sicaire, A.-G.; Meullemiestre, A.; Fabiano-Tixier, A.-S.; Abert-Vian, M. Ultrasound Assisted Extraction of Food and Natural Products. Mechanisms, Techniques, Combinations, Protocols and Applications. A Review. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry 2017, 34, 540–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knorr, D.; Froehling, A.; Jaeger, H.; Reineke, K.; Schlueter, O.; Schoessler, K. Emerging Technologies in Food Processing. Annual Review of Food Science and Technology 2011, 2, 203–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, T.J. Ultrasonic Cleaning: An Historical Perspective. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry 2016, 29, 519–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Sun, D.; Sun, X.; Zhu, C.; Wang, Q. Combining Ultrasound and Microwave to Improve the Yield and Quality of Single-Cell Oil from Mortierella Isabellina NTG1−121. Journal of the American Oil Chemists’ Society 2018, 95, 1535–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Guo, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Z. Effects of Ultrasound Combined with Hydrothermal Treatment on the Quality of Brown Rice. LWT 2024, 196, 115874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Chen, W.; Zhou, P. Conformation Stability, in Vitro Digestibility and Allergenicity of Tropomyosin from Shrimp (Exopalaemon Modestus) as Affected by High Intensity Ultrasound. Food Chemistry 2018, 245, 997–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-L.; Mao, H.-Y.; Cao, M.-J.; Cai, Q.-F.; Su, W.-J.; Zhang, Y.-X.; Liu, G.-M. Purification, Physicochemical and Immunological Characterization of Arginine Kinase, an Allergen of Crayfish (Procambarus Clarkii). Food and Chemical Toxicology 2013, 62, 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanic-Vucinic, D.; Stojadinovic, M.; Atanaskovic-Markovic, M.; Ognjenovic, J.; Grönlund, H.; van Hage, M.; Lantto, R.; Sancho, A.I.; Velickovic, T.C. Structural Changes and Allergenic Properties of β-Lactoglobulin upon Exposure to High-Intensity Ultrasound. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research 2012, 56, 1894–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barre, A.; Jacquet, G.; Sordet, C.; Culerrier, R.; Rougé, P. Homology Modelling and Conformational Analysis of IgE-Binding Epitopes of Ara h 3 and Other Legumin Allergens with a Cupin Fold from Tree Nuts. Molecular Immunology 2007, 44, 3243–3255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Lin, L.; Chau, F. Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Ginseng Saponins from Ginseng Roots and Cultured Ginseng Cells. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry 2001, 8, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Vanga, S.K.; McCusker, C.; Raghavan, V. A Comprehensive Review on Kiwifruit Allergy: Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, Management, and Potential Modification of Allergens Through Processing. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf 2019, 18, 500–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Wang, J.; Raghavan, V. Critical Reviews and Recent Advances of Novel Non-Thermal Processing Techniques on the Modification of Food Allergens. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2021, 61, 196–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jadhav, H.B.; Annapure, U.S.; Deshmukh, R.R. Non-Thermal Technologies for Food Processing. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-Q.; Chen, Q.; Liu, X.-H.; Chen, Z.-X. Inactivation of Soybean Lipoxygenase in Soymilk by Pulsed Electric Fields. Food Chemistry 2008, 109, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Zeng, Q.-H.; Wang, L.; Wang, J.J.; Li, S.; Zhu, J.; Zeng, X.-A. Novel Thawing Method of Ultrasound-Assisted Slightly Basic Electrolyzed Water Improves the Processing Quality of Frozen Shrimp Compared with Traditional Thawing Approaches. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry 2024, 107, 106931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, M.; Bhandari, B.; Yang, C. Ultrasound Treatment of Frozen Crayfish with Chitosan Nano-Composite Water-Retaining Agent: Influence on Cryopreservation and Storage Qualities. Food Research International 2019, 126, 108670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekezie, F.-G.C.; Cheng, J.-H.; Sun, D.-W. Effects of Atmospheric Pressure Plasma Jet on the Conformation and Physicochemical Properties of Myofibrillar Proteins from King Prawn (Litopenaeus Vannamei). Food Chemistry 2019, 276, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkataratnam, H.; Cahill, O.; Sarangapani, C.; Cullen, P.J.; Barry-Ryan, C. Impact of Cold Plasma Processing on Major Peanut Allergens. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 17038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nooji, J.K. 2011. Reduction of wheat allergen potency by pulsed ultraviolet light, high hydrostatic pressure, and non-thermal plasma (Doctoral dissertation, University of Florida).

- Dasan, B.G.; Boyaci, I.H. Effect of Cold Atmospheric Plasma on Inactivation of Escherichia Coli and Physicochemical Properties of Apple, Orange, Tomato Juices, and Sour Cherry Nectar. Food Bioprocess Technol 2018, 11, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pankaj, S.K.; Wan, Z.; Keener, K.M. Effects of Cold Plasma on Food Quality: A Review. Foods 2018, 7, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pankaj, S.K.; Keener, K.M. Cold Plasma: Background, Applications and Current Trends. Current Opinion in Food Science 2017, 16, 49–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.L.; Hefle, S.L. Will Genetically Modified Foods Be Allergenic? Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2001, 107, 765–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupa, P.; Nakamura, S.; Katayama, S.; Mine, Y. Attenuation of Allergic Immune Response Phenotype by Mannosylated Egg White in Orally Induced Allergy in Balb/c Mice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 9479–9487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, Y.; Faustinelli, P.; Ramos, M.L.; Hajduch, M.; Stevenson, S.; Thelen, J.J.; Maleki, S.J.; Cheng, H.; Ozias-Akins, P. Reduction of IgE Binding and Nonpromotion of Aspergillus Flavus Fungal Growth by Simultaneously Silencing Ara h 2 and Ara h 6 in Peanut. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 11225–11233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, E.M.; Helm, R.M.; Jung, R.; Kinney, A.J. Genetic Modification Removes an Immunodominant Allergen from Soybean, Plant Physiol 2003, 132, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Allergen Type | Response to Thermal Processing |

| Bet v 1-like proteins (e.g., Mal d 1 in apple, Pru av 1 in cherry) | Highly sensitive to heat; prone to unfolding. Susceptible to chemical changes such as Maillard reaction products in high-sugar foods and interactions with polyphenols, leading to decreased allergenic potential. |

| Prolamin superfamily proteins (e.g., non-specific lipid transfer proteins [nsLTPs], 2S albumins like Mal d 3; tropomyosin; parvalbumin) | Moderately heat stable; proteins unfold to a limited extent but tend to regain their structure upon cooling. Maillard reactions may still enhance allergenic potential. |

| Cupin family proteins (e.g., Ara h 1 in peanut); Lipocalins (e.g., β-lactoglobulin and α-lactalbumin in milk) | Partially resistant to denaturation; undergo partial unfolding and tend to aggregate. Can form structural networks (e.g., in emulsions or gels). Heat can also lead to Maillard reactions, which may increase allergenicity. |

| Flexible proteins (e.g., caseins in milk, gluten storage proteins in wheat, ovomucoid in egg) | Structurally dynamic and heat-resistant; maintain mobility and do not exhibit classic denaturation behavior under thermal conditions. Their allergenicity remains largely unchanged. |

| Technology | Mechanism of Action | Limitations |

| High-Pressure Processing | Disrupts non-covalent bonds within proteins; alters protein conformation through aggregation and gelation, affecting epitope exposure; enhances enzymatic hydrolysis. | Dual effects of pressure require accurate control; combining with other treatments may be necessary to optimize results. |

| Pulsed Electric Fields | Alters the secondary structure of allergenic proteins. | Often used alongside heat treatments to improve efficacy. |

| Pulsed UV Light | Delivers high-intensity UV pulses that cause photochemical modifications in proteins, including structural changes and epitope destruction | Limited penetration depth; potential degradation of sensitive nutrients; treatment uniformity can be challenging depending on food surface characteristics. |

| Cold Plasma | Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS and RNS) interact with antigens, altering protein configurations. | High equipment costs; limited understanding of how cold plasma mitigates food allergens; potential cytotoxic effects of treated liquids warrant further investigation. |

| Ultrasound | Cavitation generated by ultrasonic waves breaks peptide bonds, leading to irreversible unfolding and structural disruption of allergenic proteins. | Can negatively impact product color, flavor, and nutritional quality. |

| Gamma Irradiation | Allergenic proteins absorb radiation, altering their 3D structures; free radical formation leads to water radiolysis and modification of amino acid side chains. | Effective dose levels are not clearly established; not all protein-rich foods are currently approved for irradiation in the EU; concerns remain regarding food irradiation safety. |

| Food Variety | Treatment Conditions | Key Findings | Reference |

| Soybean | 300 MPa, 40°C, 15 min | HHP notably reduced allergenicity in soybean sprouts, with only an 18% decrease in essential amino acids and overall nutritional value. HHP may offer a viable method for producing low-allergen soybean sprouts. | [2] |

| Soybean | 400 MPa | Treatment improved protein solubility and hydrophobicity, while decreasing β-sheet content. | [3] |

| Soy protein isolate (infant formula) | 300 MPa, 15 min | Allergenicity reduced by 46.8% due to structural and interaction changes in SPI, suggesting enhanced safety in allergic individuals. | [4] |

| Peanut | 150–800 MPa, 20–80°C, 10 min; 60–180 MPa | No major changes observed in allergen secondary structure under HHP. However, high-pressure microfluidization reduced Ara h 2 allergenicity by modifying its structure and increasing UV absorption and hydrophobicity. | [5,6] |

| Tofu | 300 MPa, 40°C, 15 min | HHP did not change tofu protein composition but lowered intensity of some protein bands. Allergenicity remained unchanged. | [2] |

| Rice | 100–400 MPa, 10–120 min; 300 MPa, 30 min + Protease N | Pressure facilitated allergen release into surrounding solution; with protease, allergens were nearly eliminated from rice grains. | [7] |

| Almond | 600 MPa, 4–70°C, 5–30 min | No significant change in allergen concentration or IgE-binding capacity as per SDS-PAGE, WB, and ELISA. | [8] |

| Whey protein isolate | 200–600 MPa, 30–68°C, 10–30 min | Antigenicity of β-lactoglobulin increased with pressure, temperature, and duration. | [9] |

| Skim milk | 200–600 MPa, 30–68°C, 10–30 min | β-lactoglobulin levels rose post-treatment; thermal addition mitigated allergenicity, but HHP-treated samples retained higher β-lg than controls. | [9] |

| Sweet whey | 200–600 MPa, 30–68°C, 10–30 min | β-lg antigenicity rose at moderate temperatures and pressures; higher temperatures reduced but did not eliminate antigenicity. | [9] |

| Milk | >100 MPa + chymotrypsin/trypsin, 20 min | Proteolysis of β-lg was accelerated under HHP, suggesting potential for hypoallergenic food production. | [10] |

| Apple | 400–800 MPa, 80°C, 10 min | Mal d 3 allergen lost α-helical structure, becoming a random coil; immunoreactivity declined at ≥400 MPa. | [6] |

| Apple | 700 MPa, 115°C, 10 min | Mal d 1 showed minimal changes at 20°C, but more pronounced at 80°C; Mal d 3 IgE reactivity dropped by ~30%. | [11] |

| Apple | 600 MPa, 5 min | Mal d 1 immunoreactivity decreased by >50% with combined high pressure and heat. | [11] |

| Apple | 600 MPa, 5 min; repeated consumption | Daily intake of HHP-treated apple gel for 3 weeks led to desensitization in highly allergic individuals; 90% negative skin tests post-treatment. | [12] |

| Carrot | 500 MPa, 50°C, 10 min | Slight increase in β-sheet structure of Dau c 1; no change in immunoreactivity observed. | [13] |

| Carrot juice | 400–550 MPa, 3–10 min; 500 MPa, 30–50°C, 10 min | HHP had no observable effect on the allergenic potential of carrot juice. | [13] |

| Celeriac | 700 MPa, 118°C, 10 min | Allergenicity of Api g 1 was significantly reduced through combined pressure and thermal processing. | [11] |

| Celery | 500 MPa, 50°C, 10 min | Api g 1 structural changes were pressure-dependent but did not impact allergenicity. | [14] |

| Food material | Target allergen | Treatment | Effect on immunoreactivity | References |

| Milk | α-casein, α-lactalbumin | UVC treatment (15 min) | 25% α-casein reduction | [166] |

| β-lactoglobulin | UVC treatment (15 min) | 27.7% whey fractions reduction | [166] | |

| Egg | Ovalbumin | UV processing (0.61 kJ/m2) | No effect | [168] |

| Ovomucoid | UV processing (63.7 kJ/m2) | No effect | [168] | |

| Shrimp | Tropomyosin | PUV sterilization (4 min) | Reduced | [170] |

| Peanut | Ara h 1, Ara h 2, Ara h 3 | PUV treatment on butter slurry (1–3 min); raw and roasted peanuts (2–6 min) | 67% reduction IgE binding of peanut butter slurry; 12.5 folds reduction, 100% reductiom total extracts | [164] |

| Soy | Gly m5 | PUV treatment (1–6 min) | 100% reduction Gly m5 reduced | [165] |

| Gly m6 | PUV treatment (1–6 min) | Gly m6 retained | [165] | |

| Soy extracts (e.g., glycinin, β-conglycinin) | PUV treatment 2 min | 20% reduction | [164] | |

| PUV treatment 4 min | 40% reduction | [164] | ||

| PUV treatment 6 min | 50% reduction | [164] |

| Mechanism | Details | Impact on Allergenicity | Citations |

| Photo-oxidation | PUV emits intense UV-C light (200–280 nm) that causes oxidative modifications, particularly in amino acids like tryptophan, tyrosine, and methionine. | Oxidative damage to amino acid residues alters the structure of allergenic epitopes. | [158] |

| Disruption of Disulfide Bonds | High-energy UV pulses can break disulfide bridges that maintain protein conformation. | Destabilization of tertiary structure reduces IgE-binding ability. | [160] |

| Epitope Modification | PUV alters conformational and linear epitopes through structural denaturation. | IgE-binding is reduced due to loss of native allergenic regions. | [68,101] |

| Protein Aggregation / Fragmentation | UV treatment may lead to cross-linking or fragmentation, depending on exposure time and intensity. | Aggregation can mask epitopes; fragmentation may eliminate allergenic potential. | [101,160,161] |

| Surface Effects | PUV has limited penetration depth (~microns); primarily impacts food surface proteins. | Effective for surface allergens; limited impact on allergens embedded within the food matrix. | [162,163] |

| Dose- and Matrix-Dependent Effects | Allergen reduction is influenced by pulse energy, duration, distance, and the optical properties (color, opacity) of the food. | Matrix composition may shield proteins or influence energy absorption, thus modulating allergenicity outcomes. | [164] |

| Food Matrix | Irradiation Dose (kGy) | Effect on Allergen | Mechanism/Observation | Reference |

| Egg (Ovalbumin) | 10–100 | Reduced allergenicity | Change in molecular weight; protein aggregation and cross-linking (disulfide bonds) | [174,177] |

| White Cake (with egg) | 10–20 | Reduced ovalbumin reactivity | Reduction in IgE binding | [174] |

| Shrimp (Tropomyosin) | 7–10 | Undetectable tropomyosin band; reduced IgE binding | Protein denaturation, aggregation; turbidity and surface hydrophobicity changes | [145] |

| Shrimp (Tropomyosin) | 1–15 + heat (100°C) | 5–30-fold reduction in IgE binding | Synergistic effect with heat treatment | [170] |

| Egg (Ovomucoid) | 10 + heat | Almost undetectable levels of ovomucoid | Irradiation more effective than heat alone due to ovomucoid heat stability | [156] |

| Tree Nuts (Almonds, Cashews, Walnuts) | 1–25 ± heat | Minimal change in allergenicity | Allergens stable under irradiation and heat | [179] |

| Food | Target Allergen | Treatment | Immunoreactivity | References |

| Soy | Proteins | 37 kHz, 10 min | Reduced 24% | [195] |

| Milk | α-casein | 500 W and 20 kHz (10–30 min) | No effect | [155] |

| β-lactoglobulin | 500 W and 20 kHz (10–30 min) | No effect | [195] | |

| α-lactalbumin | 500 W and 20 kHz (10–30 min) | No effect | [190] | |

| Peanut | Ara h1 | 50 Hz for 5 h | Reduced 84.8% | [196] |

| Ara h2 | 50 Hz for 5 h | Reduced 4.88% | [197] | |

| Shrimp (boiled) | Proteins | 30 kHz, 800 W (0–50 °C, 0–30 min) | Reduced 40%–50% | [197] |

| Shrimp (raw) | Proteins | 30 kHz, 800 W (0–50 °C, 0–30 min) | Reduced up to 8% | [197] |

| Crayfish | Tropomyosin | 100–800 W, 15 min | Reduced | [198] |

| Shrimp and allergens | Multiple (including tropomyosin) | 30 Hz, 800 W (30–180 min) | Reduced up to 75% | [170] |

| Crayfish | Arginine kinase | 200 W, 30 °C (10–180 min) | No effect | [189] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).