1. Introduction

Peanut and tree nuts are among the predominant foods causing allergic reactions, after fruits, in Europe [

1]. In the last decades there has been an increase in nut and tree nut consumption because of their favourable health benefits. The main reason for the increased consumption of tree nuts is their singular nutritional composition [

2]. Most of proteins causing tree nut allergy are member of protein families of vicilins, legumins, 2S albumins and nsLTPs. Profilins and pathogenesis-related (PR) proteins contributed to pollen associated tree nut allergy. Moreover, oleosin and thaumatin-like proteins are relevant allergens. Most of tree nut allergens have high resistance to enzymatic degradation and denaturation. Currently, at least 11 allergens have been identified in peanut: Ara h 1 (7S vicilin), Ara h 3 and Ara h 4 (11S legumins), Ara h 5 (profilin), Ara h 2, Ara h 6 and Ara h 7 (2S albumins), Ara h 8 (PR-10), Ara h 9 (LTP), Ara h 10 and Ara h 11 (oleosins)[

3]. Ara h 1 constituted around 15% of total proteins, while Ara h 2 constituted about 8%. Several hazelnut proteins have been registered in the WHO-IUS list of allergens: Cor a 1 (Bet v1 homologue), Cor a 2 (profilin), Cor a 8 (LTP), Cor a 9 (11S legumin), Cor a 11 (7S vicilin), Cor a 14 (2S albumin) and Cor a 12, Cor a 13 and Cor a 15 (oleosins) [

4]. The five pistachio major allergens are Pis v 1 (2S albumin), two 11S legumins (Pis v 2 and 5), the 7S vicilin Pis v 3 and the superoxide dismutase Pis v 4 [

5,

6,

7]. Three cashew allergens have been described: Ana o 1 (7S vicilin), Ana o 2 (11S legumin) and Ana o 3 (2S albumin), which can induce severe reactions even at minimal doses [

8,

9]. Most of epitopic regions of Pis v 1 and Pis v 3 are homologs with the epitopes of cashew allergens. This finding is considered the molecular base for the reported cross-reactivity between cashew and pistachio [

10].

The food processing at industrial level is useful to ensure food safety and to improve organoleptic characteristics. This processing can modify the food allergenicity because it can change the physicochemical properties of allergens. The level of modifications is related with factors such as the class of processing used, processing conditions, duration, food matrix, etc [

11,

12,

13]. The modifications that food proteins can suffer during processing includes aggregation, denaturation, and chemical alterations. These alterations might change IgE reactivity, reducing or increasing food allergenicity. Consequently, understanding how food processing can affect the protein characteristics, such as their resistance to pressure and heat, as well as their chemical and mechanical activities is a relevant topic in food allergy management [

14,

15,

16]. The thermal treatments include boiling, frying, roasting, microwave cooking and heating under pressure by autoclaving or DIC (Controlled Instantaneous Depressurization) processing. Non-thermal treatments as enzymatic digestion or HHP (high hydrostatic pressure) might also be used on foods alone or in combinations. These processes can cause modifications in chemical characteristics of proteins or produce biochemical reactions inside the components of food matrix [

17,

18]. There are an extensive number of studies on the modifications of peanut and tree nut allergenicity throughout different heat treatments [

11,

17,

18]. Boiling at 100˚C at several times is not effective to reduce allergenicity of almond, cashew, pistachio, walnut as well as for peanuts, hazelnuts [

19,

20,

21,

22]. The effect of processing on hazelnut reveals an important reduction in its immunoreactivity upon roasting at 140˚C for 40 min although this decrease is not of clinical relevance since 29% of the allergic patient still have allergic symptoms after ingestion of roasted hazelnuts. The influence of autoclaving on tree nut immunoreactivity has been studied on almond, chestnut, cashew, pistachio, hazelnut, walnut, besides peanut [

18,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. After autoclaving these tree nuts, their residual allergenicity is drastically diminished with a direct association with increased heat/pressure and time and even almost abolished at harsh conditions (138˚C for 30 min). The introduction of a hydration step (2h), before autoclaving, followed by drying enhanced the final efficacy of the treatment on almond and hazelnut allergenicity [

21,

22]. In addition, the hazelnut allergen digestibility increased in prehydrated samples compared to the controls and non-resistant peptides survive after both treatments suggesting high protein fragmentation. The influence of other pressured heat treatment, such as Controlled Instantaneous Depressurization (DIC) has been analysed on tree nuts and peanuts allergenicity [

18,

24,

28,

29]. In agreement to these findings, DIC applied at harsh condition (7 bar, 120 s) produce a drastic reduction of the IgE immunoreactivity of tree nut and peanut allergenic proteins. The in vitro results obtained using IgE sera from sensitized patients (immunoblots and ELISA) indicated that the reduction in immunodetection affected more to pistachio (75%) than cashew, but it was not completely abolished. Consequently, pistachio allergens seem to be less resistant than cashew proteins. Combination of pressured heating (autoclave and DIC), and enzymatic hydrolysis using food grade proteases notably reduced the allergenic reactivity. The combination of DIC treatment before enzymatic digestion resulted in the most effective methodology to drastically reduce or indeed eliminate the allergenic capacity of peanuts and tree nuts [

24,

25].

Resistance of proteins to gastrointestinal digestion (GI) represents an important factor for allergenicity evaluation. Higher resistance to digestion seems to increase the sensitization capacity of a food protein and consequently, allergenicity is also incremented [

30]. Stability under gastric conditions has been considered a useful parameter for identification of allergens [

31] and in vitro tests of pepsin digestion was incorporated since 2001 into a FAO/WHO procedure for the allergenicity assessment of novel food proteins [

32]. An allergen must preserve its intact structure during digestion process to sensitize an individual via oral route, thus allowing the intact epitopes to be taken up by the gut to sensitize the mucosal immune system. However, potent allergens do not stable to digestion and the localization of multiple IgE binding epitopes in structural elements not surface-exposed suggest that partial digestion of food allergens in the GI tract does not eliminate their sensitizing capacities [

31]. Previous studies have demonstrated that in vitro digestion products of peanut allergens are able to induce IgE production in rats [

33]. In vitro digestion models simulating the human digestion process are a useful approach to address this issue. The main advantages of this tool are simplicity, low costs and good reproducibility [

34].

In the present study, we investigate the effect of heat and pressure processing on the allergenic protein digestibility of peanut, hazelnut, pistachio and cashew samples.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

Peanuts (

Arachis hypogea, variety Virginia) and commercial unprocessed cashews (

Anacardium occidentale L. type 320) were supplied by Productos Manzanares (Spain). Hazelnut (

Corylus avellana, var. Negreta) and pistachio nuts (

Pistacia vera L. var. Kerman) was obtained by IRTA (Institut de Recerca I Tecnologia Agroalimentaries; Mas de Bover, Tarragona, Spain). All nuts were processed following Cuadrado et al.[

24] to obtain Untreated, Boiled (in distilled water 1:5 w/v, the seeds were boiled at 100°C for 60 min), Autoclaved (in a food-grade autoclave, Compact 40 Benchtop Autoclave, Priorclave, London, UK; at 138˚C, 256 kPa for 30 minutes) and Controlled Instantaneous Depressurization (DIC, 7 bars for 2 min) seeds. This last treatment was performed following a factorial experimental design by La Rochelle University (LaSiE) and described by Haddad et al. [

35].

The processed seeds were homogenized and milled in a particular size <1mm using a kitchen robot (Thermomix 31-1, Vorwerk Elektrowerke, GmbH & Co. KG, Wüppertal, Germany). Flours were defatted with n-hexane and the nitrogen content was determined by LECO analysis according to Official Methods of Analysis [

36]. The protein content was calculated with a conversion factor 5.33. All the treated and untreated flours were stored at 4˚C in polyethylene bags until analysed, such as Control Samples (CS).

2.2. Enzymes and Reagents

α-Amylase from porcine pancreas (A3176-500 KU; Type VI-B, lyophilized powder 5 U/mg solid), bile form bovine and ovine bile acid mixture (B8381-25G), pancreatin from porcine pancreas (P7545-25G, lyophilized powder, 8 X USP) and porcine pepsin from gastric mucosa (P6887-5G, lyophilized powder 3200–4500 U/mg protein) were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (Saint-Louis, MO, USA). All reagents used in the assay are standard analytical grade.

2.3. Patients’ Sera

Sera from 32 patients allergic to peanut, hazelnut, cashew and pistachio were collected in the Allergy Department of any of the three Spanish hospitals (Hospital Universitario Cruces, Fundación Jiménez Díaz, and Hospital Universitario Princesa) during 2020-2022. The investigation was authorized by the Ethics Committees of the three hospitals, in agreement with the regulations of the boards of their organizations (Permissions CBVI839/2M, PIC164-18, No. 3798, respectively).

Immunoreactivity against peanut and hazelnut was assayed using two different pools of sera. One of them included 10 sera from individuals sensitized to 2S albumin, 7S vicilin and/or 11S globulins peanut allergens, named as Sprot (storage proteins) (patients no. #3, #4, #5, #8, #9, #15, #17, #21, #27, #31, all used at 1:10 dilution). The other serum pool formed by 17 peanut individuals sensitized to LTP allergen (#2, #6, #10, #11, #12, #13, #14, #16, #18, #19, #20, #25, #26, #28, #30, #32, #33), all used at 1:10 dilution. On the other hand, a pool of sera using serum from 7 (#1, #3, #4, #5, #8, #22, #27) or 15 patients (#2, #6, #10, #11, #13, #14, #16, #18, #19, #20, #23, #24, #26, #30, #33) sensitized to hazelnut Sprot or LTPs respectively was prepared. The pool sera from patients with sensitization to pistachio and cashew (positive skin prick test and specific IgE>0.35 to these nuts) was prepared with 15 sera (# 1, #2, #3, #5, #6, #8, #10, #14, #18, #23, #25, #27, #29, #31, #33) and 12 sera (#1, #3, #4, #5, #6, #8, #10, #18, #25, #27, #31, #33) respectively. Specific information about included patients is listed in

Table S1.

Total IgE and specific serum IgE levels were measured by ImmunoCAP® (ThermoFisher Scientific, Upsala, Sweden). Specific IgE to peanut allergens (Ara h 1, Ara h 2, Ara h 3, Ara h 6, Ara h 8 and Ara h 9), hazelnut allergens (Cor a 1, Cor a 8, Cor a 9 and Cor a 14) and cashew allergens (Ana o 3) were also determined and collected following the manufacturer’s recommendations, taking into account that sIgE value at least above than 0.35 kUA/L was assumed as a positive result.

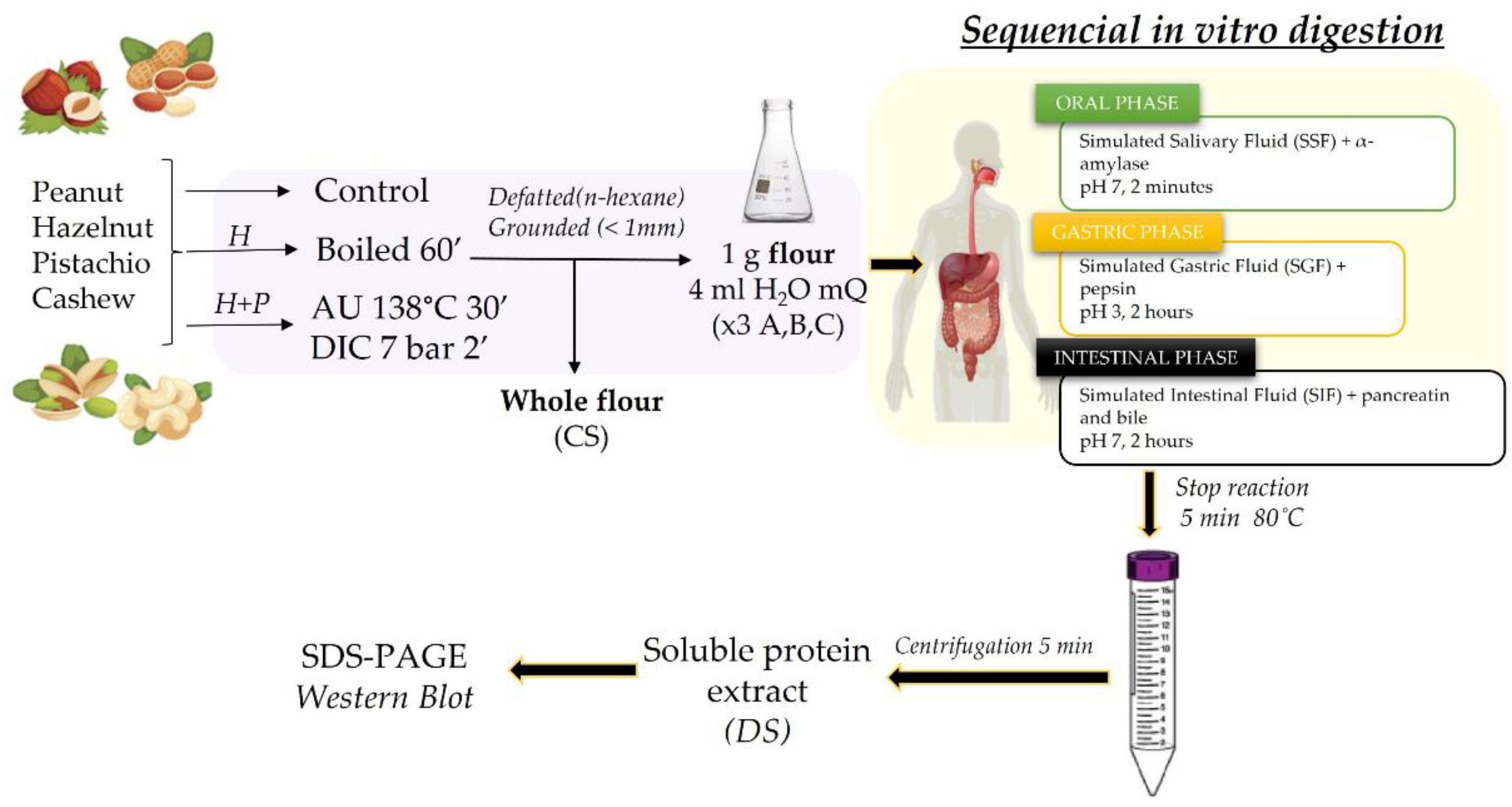

2.4. In Vitro Enzymatic Digestion

The in vitro digestion was sequentially performed following INFOGEST protocol with slight modifications (

Figure 1) [

34]. This method simulated the different conditions of the bolus along the gastrointestinal tract. All samples were performed in triplicate, replies to A, B and C, obtaining the Digested Sample (DS). Appropriate controls without enzymes were also included (CS), being the nut whole extract from defatted flours (

Figure 1).

To simulate the Oral Phase: 1g of defatted flour of each sample were homogenized with MilliQ H2O, ratio 1:4 (w/v), and transferred to a flask. Another mL of MilliQ H2O was added and shaken for 15 minutes at room temperature. At 37˚C under agitation, the sample were mixed with 0.7mL of Simulate Salivary Fluid (SSF) and 5µL of CaCl2 0.3M. Subsequently, 195µL of H2O MiliQ, and 0.1mL of α-amylase was added and incubated for 2 minutes at 37˚C under agitation (160 rpm).

To simulate the Gastric phase: At room temperature, 1.5mL of Simulated Gastric Fluid (SGF) stock solution were added to the samples, and then 1µL of CaCl2 0.3M. The pH was adjusted at pH 3 with HCl 3N, finally, H2O MilliQ was added to complete the final volume of 2 mL. The flask wase incubated for 1h, 37˚C at 160rpm orbital agitation and 0.16mL of Pepsin was added. After this period, the samples were cooled to room temperature.

To simulate the Intestinal phase: the samples were mixed with 2.2 mL of Simulate Intestinal Fluid (SIF) and 8µL CaCl2 0.3M. The pH was adjusted to 7 with NaOH 4N and H2O MilliQ was added to the flask. 1mL of Pancreatin and 0.5mL of Bile salts were mixed and incubated in the flask, for 2h at 37˚C and 160rpm in orbital agitation (final volume 4mL). Finally, the reaction was stopped at 80˚C for 5 minutes. After centrifugation for 5 minutes at 10000g at 4˚C the supernatant was collected and freeze for subsequent analysis.

2.5. SDS-PAGE Analysis

Peanut samples (20µg protein per well) were performed on 4-20% gradient polyacrylamide gels, according to Laemmli method using β-mercaptoethanol (Bio-Rad, CA, USA) and hazelnut, pistachio and cashew samples (20µg protein per well) were loaded in 4-12%, using Bolt LDS sample buffer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The samples were boiled at 60˚C for 10 minutes and loaded in Tris-HCl linear gradient gels (Bio-Rad, CA, USA) and Bolt Bis-Tris Plus gels, respectively. Both protein gels were stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue dye.

2.6. Immunoblotting Western Blot Experiments

The samples (20µg protein per well) were loaded and resolved on 4-20% gel (Bio-Rad, CA, USA) or 4-12% (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) such as SDS-PAGE Analysis. Proteins were transferred onto PVDF membranes using a transfer equipment (iBlot 2 Western Blot Transfer System, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for 7 minutes at 20 volts. After transference, membranes were washed and incubated in blocking solution (2% non-fat milk in PBS, at room temperature) for 1h and then with 1:10 diluted serum pool from patients, at 4ºC, overnight with agitation. Then, the membranes were washed with PBS-Tween20 and treated with Horseardish peroxidase (HRP) conjugated mouse anti-human IgE (Sigma, Saint Louis, MO, USA) diluted in blocking solution (1:10000). Finally, detection was performed with BCIP/NBT substrate (Sigma, Saint Louis, MO, USA) and revealed using CCD camera system of the ChemiDoc (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

2.7. Inhibition ELISA

A competitive ELISA inhibition assay was realized in peanut and hazelnut samples with some modifications [

24]

. Wells were coated with 100μL of raw nuts protein extracts (0.5 mg/mL in PBS pH 7) in Polystyrene microtiter plates (Immulon 4 HBX, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and then incubated overnight at 4˚C. In parallel, serum pools were prepared from peanut and hazelnut allergic patients, in both cases with sensitization to Sprot. For peanut assay, the pool contained sera from 9 patients (patients no. #3, #4, #5, #8, #15, #17, #21, #27 and #31; diluted 1:10) and in the hazelnut assay, from 7 patients in (#1, #3, #4, #5, #8, #22, #27; diluted 1:10). Pools were respectively preincubated with the digested and undigested samples of raw (control), boiled, autoclaved and DIC treated nuts (final concentrations: 0.1, 0.01, 0.001 mg/mL), overnight at 4˚C with shaking. As a control, an un-inhibited serum was included (serum preincubated with PBS). Then, wells were washed with PBS with 0.1 % Tween-20 and blocked with 100 μL of PBS 3 % non-fat milk, 1 h at 37˚C and then washed again. The un-inhibited and inhibited serums were added to the wells (100 μL per well) for 1 h. After washing, samples were incubated with 100 μL per well of Horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugated mouse anti-human IgE (1:1000 dilution) (Sigma, Saint Louis, MO, USA) for 1h at 37˚C and then washed again. 100 μL of peroxidase substrate (SureBlue TM, KPL, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) were added for peroxidase reaction (30 min). Finally, the reaction was stopped adding 100 μL of 1 % HCl. The optical density (O.D.) was determined at 450 nm and the percentage of inhibition in IgE binding was calculated following to the formula: [(1 – (AI / AN)] x 100, where AI means the O.D. value of samples preincubated with inhibited sera (raw or thermally or enzymatically digested samples), and AN means the O.D. value of samples incubated with un-inhibited sera. All tests were carried out at least in triplicate.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. General Characteristics of Collected Sera

Thirty-two allergic patients were studied in this research (56.26% female, average age 27.6 ± 14.74 years, ranging between 55 and 6 years old), showing immunoreactivity to peanut, hazelnut, cashew and/or pistachio allergens. Total sIgE average was 1078.2 kU/L ± 293.4 (ranged between 7600 and 49 kU/L).

Sera were classified according to sensitivity to specific allergens (when the information was known) (

Table S1). Thus, in peanut and hazelnut, two different sera pools were prepared for each nut, containing sera from patients sensitized to storage proteins from both nuts (named Sprot, being 2S albumins, 7S vicilins and 11S globulins, with 10 or 7 sera per nut, respectively) or to LTP allergen (pools containing 16 and 15 sera, respectively). In the case of cashew and pistachio, from which less information was available about specific allergens, two pools were also prepared. One of them was a pistachio-sensitized pool, containing sera from 15 patients, and another for cashew-sensitized patients that contained 12 sera. Allergy to cashew and pistachio is frequently shared by the same patients, we found that 92% (11/12) of the sera containing sIgE to cashew also were sensitive to pistachio nuts, whereas 73% (11/15) of the patients with sIgE to pistachio (>0.35 kU/L) showed also sIgE to cashew. Interestingly, among the collected sera, any patient was allergic only to cashew and only one showed allergy only to pistachio (patient #29). Half of the patients allergic to cashew showed sIgE > 0.35 kU/L to the 2S albumin Ana o 3 (6/12). Most of the patients (81%) collected in this study were allergic to peanuts (26/32, 7 of them showed allergy only to this nut, 27%), followed by hazelnut (22/32, near to 69%, 2 of them were allergic only to hazelnut, 9%). Almost 22% (7/32) of patients were allergic to the four nuts assayed in this study (

Figure S1A).

As mentioned before, specific IgE for common allergenic proteins (2S, 7S, 11S, PR-10 and LTP) were available for analysis, mostly from peanut and hazelnut (

Table S1). All patients except for one (#29) were allergic to one or both nuts, 19 of them sensitized to LTP allergens (61%) and 12 to Sprot allergens (38.7%) (

Figure S1B).

Among reported symptoms, 50% of the patients showed oral allergy syndrome (OAS) (16/32) whereas almost 41% experienced systemic symptoms such as angioedema, vomiting or urticaria. Five out of 32 did not report or experienced any allergenic symptoms or it is not known (15.6%). None of them suffered anaphylaxis after ingestion of these nuts (

Table S1).

3.2. Efficiency of In Vitro Digestion on Untreated and Processed Samples

Food allergenicity is related to the usually high resistance of the protein allergen to digestive enzymes and tree nuts are not an exception [

37,

38]. Commercially available enzymes are normally designed for improving food digestibility, some sensory properties or enhancing antioxidant capabilities and even reducing the presence of allergenic compounds [

18]. Thus, controlled enzymatic digestion using specific proteases has been assayed as a processing tool to reduce allergenicity of many tree nut allergens including peanut, cashew, pistachio or hazelnut [

19,

28,

39]. A key point to understanding the resistance of any allergenic protein is to know its susceptibility to GI digestion, so we aimed to examine the outcome of in vitro gastric digestion of hazelnut, peanut, pistachio and cashew proteins by following the INFOGEST protocol [

34]. Thus, the structural changes derived from thermal treatments on the protein allergens might have a direct consequence on their GI digestibility, and combination of both processes has been proved to be crucial for understanding and verify the immunoreactivity of these nuts [

40]. We investigated the effect of several thermal processing, combined with or not with pressure, in the GI digestibility of those allergenic proteins. We have assayed INFOGEST protocol on complete flours of those tree nuts after defatting, since the presence of lipids, sugars and other molecules is a limiting factor that increases the complexity of the assay. In this work we have analysed the effects of sequential in vitro digestion simulating oral, gastric and intestinal phases on the IgE-binding capacity of mentioned tree nuts by western blotting and ELISA.

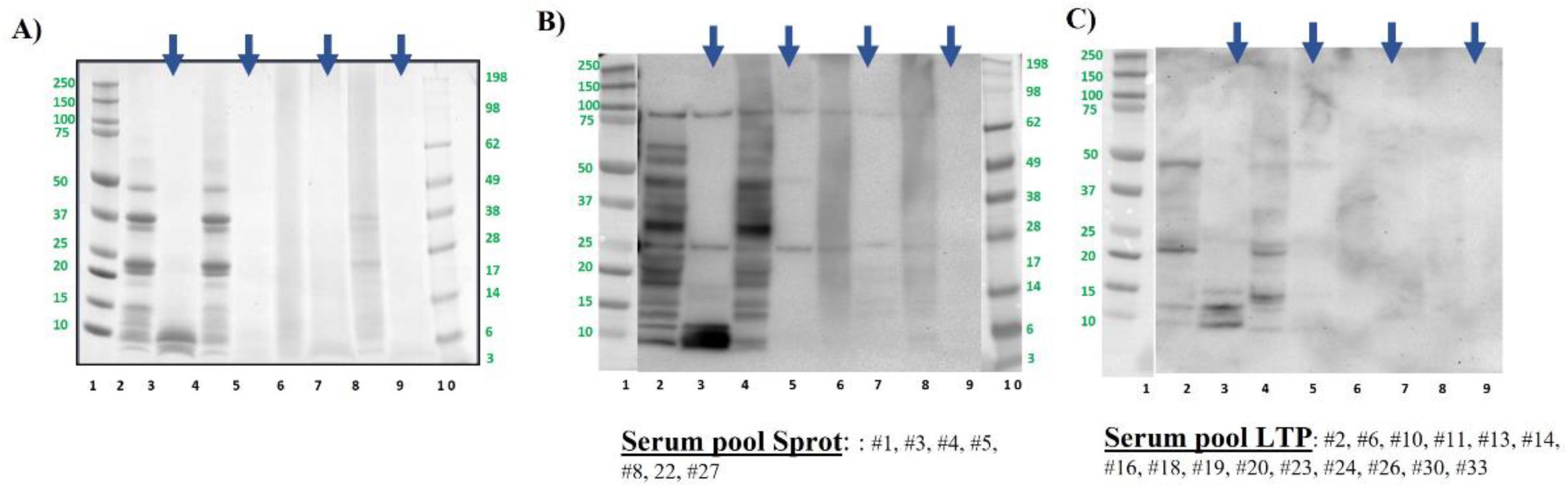

3.2.1. Effect of Processing on the Peanut Protein Profile and IgE-Binding Capacity after In Vitro Gastrointestinal Digestion

Figure 2A show the protein profile of peanut, including untreated and thermally treated samples by boiling or autoclaving at different conditions, before and after INFOGEST assay. GI digestion of raw peanut altered, but not reduced, the protein profile and modified the IgE-binding peptides, when it was assayed with both sera pools (

Figure 2B and

Figure 2C). It can be noticed that boiling for 60 minutes has no effect on the protein band profile of peanut, showing the same band range from 60 to 10 kDa (

Figure 2A, lane 4), approximately, being consistent with the previous results [

38,

39,

41,

42,

43]. After INFOGEST digestion of untreated and boiled samples, peanut protein profile remained the same, but including a not-described protein or a protein accumulation of around 100 kDa (

Figure 2A lanes 2-5).

When western blotting was analysed, it can be observed that in vitro digestion of boiled peanut reduces the IgE capacity of serum pool from allergic patients, both in Sprot pool and in LTP pool. It is especially patent in the range below 40 kDa in Sprot pool, remaining slightly visible the Ara h 2 10 kDa digestion-resistant band [

44]. Moreover, that protein of 100 kDa, which did not correspond to any described allergen in peanut, remained intact and with important IgE binding capacity (

Figure 2B, lanes 3 and 5). In the LTP pool, the Ara h 2 doublet bands between 20 and 25 kDa is affected by boiling, being only the heavier protein able to retain the binding of IgE in these sample. Band around 10-12 kDa in this LTP’s pool, which would correspond to nsLTP allergens Ara h 9 or Ara h 16, is slightly reactive in raw and boiled samples, but it disappeared after GI digestion simulation (

Figure 2C, lanes 3 and 5).

It has been already demonstrated that autoclaving, specially at drastic conditions as the assayed in this work (138˚C, 2.56 b and 30 min), reduces the capacity of IgE binding significantly [

24]. The protein smear obtained after in vitro digestion of this pressured-treated sample is almost complete, and the capacity of IgE binding is nearly inexistant (

Figure 2B and C lane 7). Slightly less protein degradation extent can be observed in peanut samples treated by DIC process although important elimination of protein bands was recovered after INFOGEST digestion process (

Figure 2A, lane 8 and 9). Among resistant protein bands, it is noticeable two about 15 and 12 kDa, which were still able to trigger the IgE binding in Sprot pool of serum. In the pool LTP, by contrast, IgE binding profile is practically the same before or after INFOGEST in samples treated by autoclaving and DIC.

Recently, it was demonstrated that peanut pastes (instead of soluble extracts) required not only DIC treatment at specific conditions of 7 b for 2 min but also enzymatic hydrolysis using commercial protease to complete mitigation of IgE reactivity against storage protein allergens [

24]

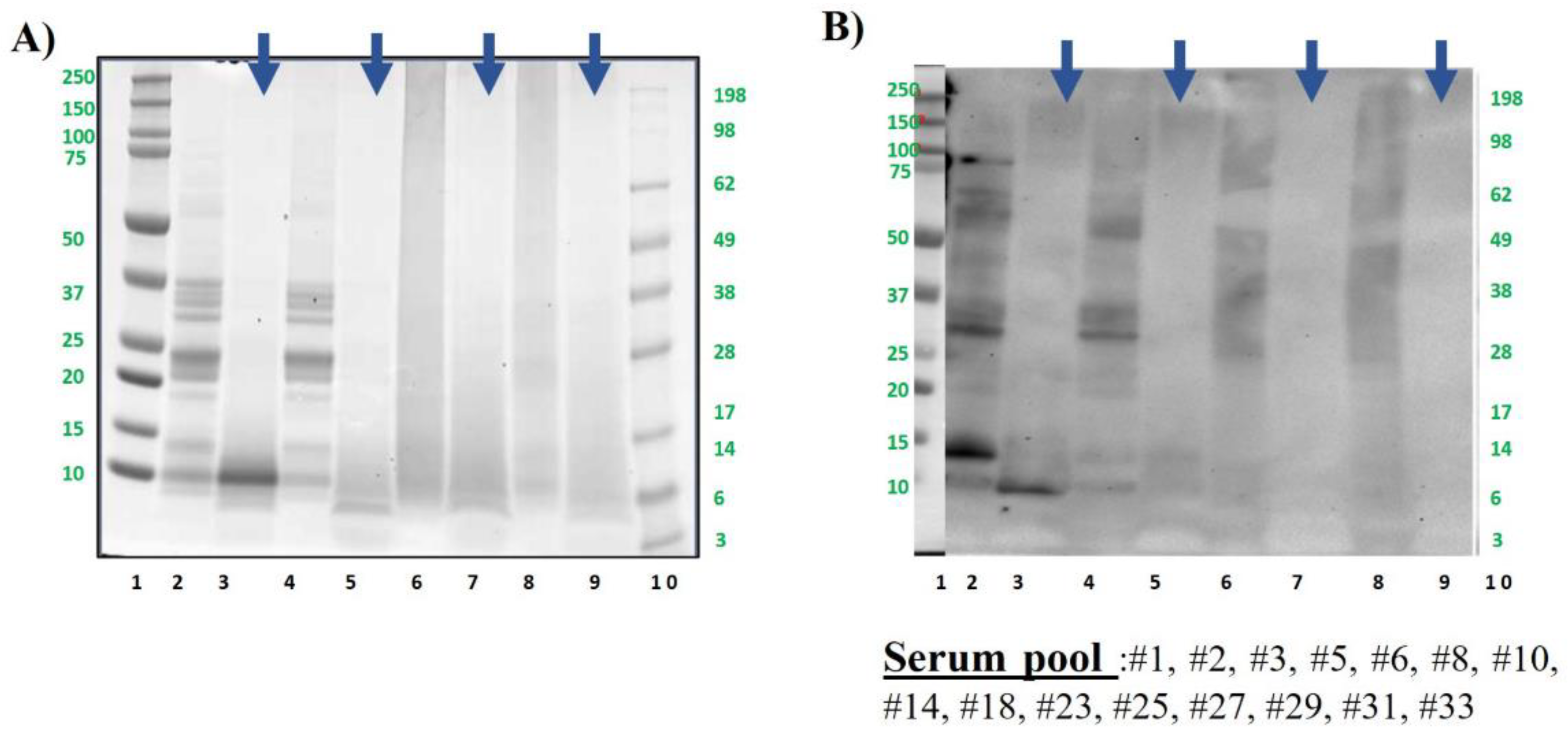

3.2.2. Effect of Processing on the Hazelnut Protein Profile and IgE-Binding Capacity after In Vitro Gastrointestinal Digestion

Protein band pattern of treated and untreated hazelnut samples is shown in

Figure 3A. Raw hazelnut protein profile ranged from 50 to 5 kDa approximately (lane 2). Although not visible in the SDS-PAGE gel, it is noticeable again a band of around 80 kDa in the immunoblotting using the Sprot pool of sera, especially in untreated and boiled samples, before and after digestion (

Figure 3B lanes 2-5). Apart from these bands, not recognized as a described allergen so far, it can be observed that the protein profile in untreated and boiled samples are very similar, as well as the IgE-binding profile. Gastrointestinal digestion of untreated hazelnut decreased the immunoreactivity of most of the allergenic bands, but other seemed to suffer an increase on the IgE binding capacity. In vitro digestion of boiled samples with the simulated GI protocol showed a slightly higher extent than in raw samples, and low molecular weight allergenic protein is lost when both serum pools were assayed (

Figure 3B and C, lanes 3

vs 5).

Thermal treatments, as boiling, modify the structure of allergens, making them more accessible to enzymes pepsin, trypsin or chemo trypsin [

40]. In the Sprot pool, the intense immunogenic band of around 10 kDa would correspond to Cor a 14, the only characterized 2S albumin from hazelnut. In fact, it can be distinguished the small and the large subunits described for this allergen that is also known to be highly resistant protein to temperature and GI digestion. Moreover, a discrete band in the 25 kDa area, probably corresponding to the basic subunit of Cor a 9, had also remained in digesta, but the acidic subunit, expected around 40 kDa, was not visible. Finally, the intense immunoreactive band in the range of 30 kDa observed in untreated and boiled sample (

Figure 3B lane 2 and 4), disappeared in the digested samples, probably converted to shorter peptides. Regarding the serum pool called LTP’s pool we observed that GI digestion of untreated hazelnut, which showed a quite complex profile of multiple immunogenic protein bands, affected the IgE binding capacity importantly, excepting for the doublet around 6-12 kDa that would correspond to the LTP allergen named Cor a 8, even more visible after in vitro digestion (

Figure 3B, lane 3). All these results are in concordance with those obtained recently by other authors, analysing the impact of INFOGEST digestion of roasted and control hazelnuts [

45].

The treatments autoclave and DIC were almost unable to trigger a reaction with IgE from the serum, independently of the assayed pool, even before performing the in vitro digestion. Extraction of proteins during digestion is a key point in those kinds of in vitro protocols, especially when thermally treated samples are included in the study, since are responsible for certain cross-linking and unexpected reactions promoting oligomerization of proteins, reducing the capacity of protein extraction.

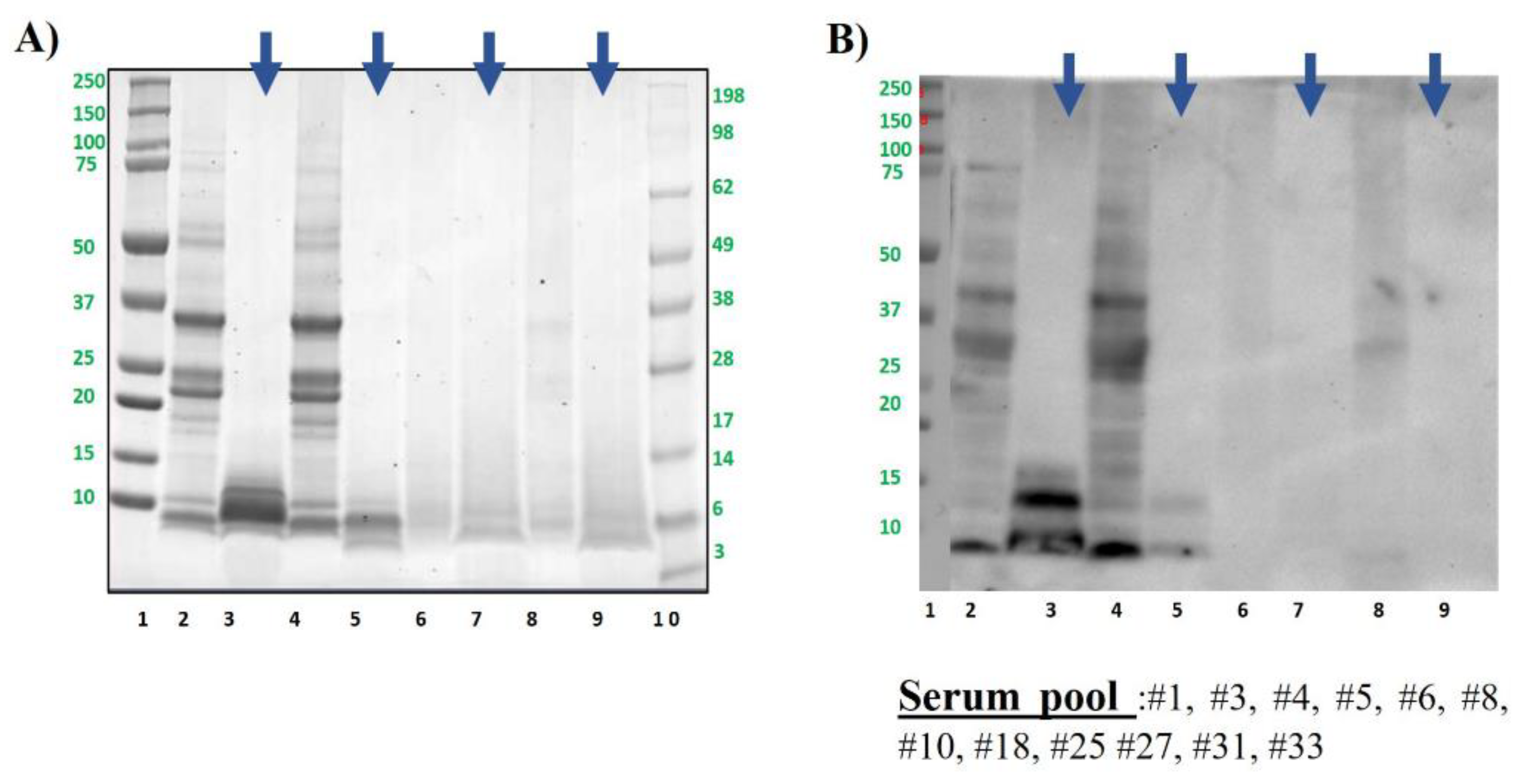

3.2.3. Effect of Processing on the Pistachio Protein Profile and IgE-Binding Capacity after In Vitro Gastrointestinal Digestion

Polypeptide profile of pistachio samples was the expected for this nut, ranged between 100 and around 5 kDa, being almost the same profile in boiled samples (

Figure 4A). Obtained results regarding GI digestion were like those described for hazelnut. After digesting by GI simulation, most of the proteins were eliminated even in the untreated samples (

Figure 4A), resulting only the ones with molecular weight below 10 kDa, that were indeed immunoreactive by western blotting (

Figure 4B lane 3). That band, that was also visible as the typical doublet in lane 2 of raw pistachio pre-digestion, corresponds to the 2S albumin Pis v 1 [

10,

43].

As observed in previous studies, boiling had no effect on the IgE binding capacity of pistachio, but after simulated GI digestion it is only slightly visible the bands of Pis v 1, whereas the immunoreactive bands corresponding to intact and subunits of Pis v 2 (11S albumin, around 50 kDa and 30 and 20 kDa respectively) were not patent after digestion (lanes 3 and 5 vs 1 and 4). As confirmed also in previous studies, autoclave and DIC treatment affected seriously to the protein and immunogenic pattern of pistachio (lanes 6 and 8 in

Figure 4A and B) [

27,

28].

3.2.4. Effect of Processing on the Cashew Protein Profile and IgE-Binding Capacity after In Vitro Gastrointestinal Digestion

As seen with pistachio, cashew protein profile is very similar in untreated and boiled samples, and in general, more reactive than pistachio, in concordance again with previous data [

27]. After being submitted to GI digestion simulation, protein profiles are slightly different, since in boiled samples are retained proteins with lower molecular weight than in untreated (below 10 kDa,

Figure 5A lanes 3 and 5).

That bands or peptide fragments are in fact corresponding to Ana o 3 [

46], the 2S albumin of cashew, being still importantly immunoreactive in the untreated nut and significantly less in boiled one. Cashew and pistachio shared most of the serum from allergic patients in the assayed pool (

Figure S1) and showed similar capacity to bind IgE before and after the digestion of extremely treated samples. Thus, both autoclave and DIC provoked a strong decrease in the number of immunoreactive bands in western blot, as demonstrated previously by our group [

25,

27,

28,

29], even thought was possible to visualize some small proteins in SDS-PAGE. In DIC samples at the assayed conditions, was still subtly visible the band around 30 kDa corresponding to the acidic subunit of Ana o 2, the 11S albumin, but after the simulation of GI digestion no bands were representative in that thermally treated cashew.

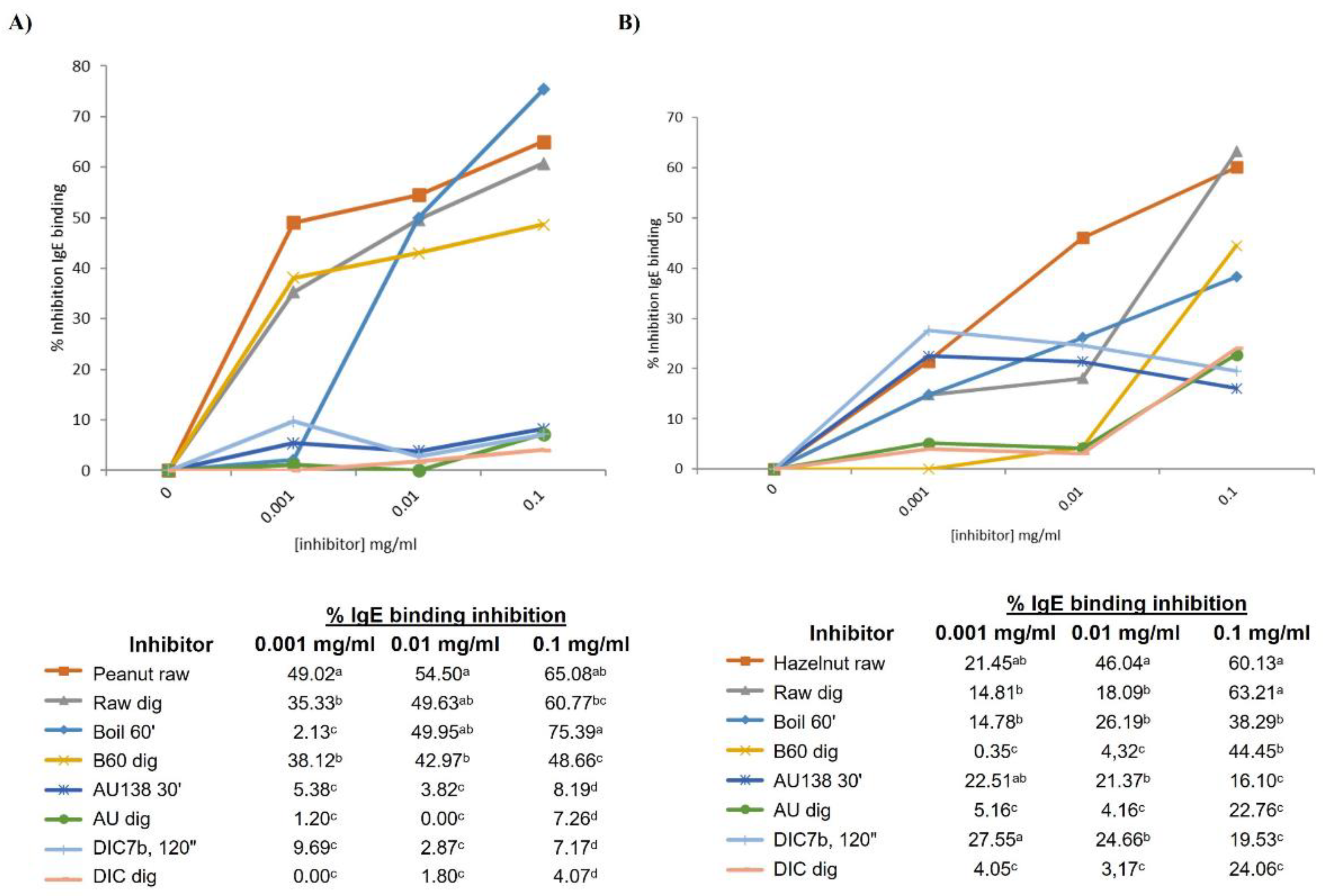

3.2.5. ELISA Inhibition

A competitive inhibition ELISA was performed using the Sprot pool sera, containing serum from 10 patients reactive to storage proteins of peanut (

Figure S1). Untreated peanut was coated in the plate (control), incubated with inhibitors at different concentrations and the percentage of inhibition was calculated as described in section 2.7 in Materials and Methods. Untreated peanut, with and without in vitro digestion, competed for IgE binding at similar extent at a concentration of 0.1 mg/ml (65.08% and 60.77%) (

Figure 6A). In accordance with the immunoblotting, digesta of boiled peanut had less capacity than not digested to compete for the IgE binding; autoclaved and DIC-treated samples pre and post in vitro digestion showed similar results, being the weakest competitors for IgE binding.

Figure 6B shows the capacity of every inhibitor (pre and post digestion of untreated and treated hazelnut) to compete with raw samples for the binding the IgE from Sprot pool sera, composed by the serum from 7 allergic patients. Again, untreated hazelnut, before and after INFOGEST protocol, showed similar percentage of IgE binding inhibition at maximum concentration of 0.1 mg/ml (60 and 63%), although at lower concentrations there were significant differences in the competition ability of untreated (raw) pre and post digestion. Also at maximum concentration, digested and non-digested boiled hazelnut showed similar capacity to bind IgE, whereas by immunoblotting we observed an important loss of immunoreactive bands in digested samples from untreated and boiled hazelnut. A significant reduction in the percentage of inhibition is in fact observed when the concentration of the inhibitor was lower than 0.1 mg/ml (table below

Figure 6B). Interestingly, although again by immunoblotting treated samples by autoclave and DIC were not immunoreactive, we found a range of 16 to 27% of inhibition in the IgE binding of those samples in every assayed concentration, although that percentage was significantly reduced after digestion with the INFOGEST protocol. Since in ELISA allergens and proteins are in their native structure, we could assume that some of the allergens may not induce the binding of IgE when proteins or peptides are denatured. Moreover, ELISA is normally more sensitive than western blotting for detecting proteins in the matrix [

45].

Since behaviour of treatments on GI digestibility, protein profiles and IgE binding capacity resulted to be similar among the 4 assayed nuts, we decide to perform these two inhibition ELISA tests only for peanut and hazelnut, using Sprot sera pool, as two representative experiments.

5. Conclusions

One important characteristic contributing to food allergenicity is the resistance to digestion shown by protein allergens. We investigated the stability and the IgE binding capacity of the main allergenic proteins of raw and treated peanut, hazelnut, cashew and pistachio nuts after applying gastric digestion conditions. In this study, we describe that processing based on temperature or temperature and pressure as autoclave (thermal) or DIC (non-thermal) affects the extent of GI digestion of peanut, hazelnut, cashew and pistachio allergens, based on INFOGEST in vitro protocol. Boiled samples are best digested than raw in all the assayed nuts. Autoclave treatment, at specific conditions of 30 min at 256 kPa and 138˚C, as well as DIC treatment at 7bar for 2 min, practically remove the immunoreactivity of these allergenic sources, and there is almost no difference between digested and non-digested extracts. As we have demonstrated in previous studies, we have observed that processing as autoclave and DIC have a relevant affection on the overall immunoreactivity of allergenic proteins from peanut, hazelnut, cashew and pistachio whereas other thermal treatment, as boiling for 1 hour, did not affect to the protein profile and IgE binding capacity of those nuts. Gastrointestinal digestion alone already extensively affects the protein pattern and modify the immunoreactive band profile of raw peanut, hazelnut, cashew and pistachio, similarly to the boiled samples, being decreased in number and intensity. The application of severe food processing treatments, combined with the study of the GI influence on highly allergenic nuts might be the first gate for new hypoallergenic formulations. In the future, it would be interesting to characterize by mass spectrometry the remaining peptides after GI digestion in raw and treated peanut samples, as well as to analyse the effects of this digestion on purified major allergens, submitted to specific thermal processing, regarding structure and IgE binding capability.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org, Figure S1: Distribution of collected sera by allergenicity to each nut. Table S1: Immunological and clinical information of the 32 patients included in the study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M.P., C.C..; methodology, A.S., C.A., S.P.; formal analysis, A.S., C.A., S.P.; investigation, A.S, C.A., M.M.P., R.L., C.C.; resources, R.L. and C.C.; data curation, M.M.P. C.C; writing—original draft preparation, A.S., C.A. M.M.P. R.L. C.C.; writing—review and editing, M.M.P., R.L, C.C.; supervision, C.C..; project administration, R.L., C.C.; funding acquisition, R.L., C.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación, grant number AGL2017-83082-R and PID 2021-1229420B-100.

Data Availability Statement

We encourage all authors of articles published in MDPI journals to share their research data. In this section, please provide details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analysed or generated during the study. Where no new data were created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, a statement is still required. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at

https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

References

- Lyons, S.A.; Clausen, M.; Knulst, A.C.; Ballmer-Weber, B.K.; Fernandez-Rivas, M.; Barreales, L.; Bieli, C.; Dubakiene, R.; Fernandez-Perez, C.; Jedrzejczak-Czechowicz, M.; et al. Prevalence of Food Sensitization and Food Allergy in Children Across Europe. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice 2020, 8, 2736-2746.e9. [CrossRef]

- Ros, E. Health Benefits of Nut Consumption. Nutrients 2010, 2, 652–682.

- Palladino, C.; Breiteneder, H. Peanut Allergens. Mol Immunol 2018, 100, 58–70. [CrossRef]

- Costa, J.; Mafra, I.; Carrapatoso, I.; Oliveira, M.B.P.P. Hazelnut Allergens: Molecular Characterization, Detection, and Clinical Relevance. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2016, 56, 2579–2605. [CrossRef]

- Ayuso, R.; Grishina, G.; Ahn, K.; Bardina, L.; Beyer, K.; Sampson, H. Identification of a MnSOD-like Protein as a New Major Pistachio Allergen. In Proceedings of the J Allergy Clin Immunol; 2007; Vol. 119, p. S115.

- Noorbakhsh, R.; Mortazavi, S.A.; Sankian, M.; Shahidi, F.; Tehrani, M.; Jabbari Azad, F.; Behmanesh, F.; Varasteh, A. Pistachio Allergy-Prevalence and In Vitro Cross-Reactivity with Other Nuts. Allergology International 2011, 60, 425–432. [CrossRef]

- Willison, L.N.; Tawde, P.; Robotham, J.M.; Penney, R.M.; Teuber, S.S.; Sathe, S.K.; Roux, K.H. Pistachio Vicilin, Pis v 3, Is Immunoglobulin E-Reactive and Cross-Reacts with the Homologous Cashew Allergen, Ana o 1. Clin Exp Allergy 2008, 38, 1229–1238. [CrossRef]

- Robotham, J.M.; Wang, F.; Seamon, V.; Teuber, S.S.; Sathe, S.K.; Sampson, H. a.; Beyer, K.; Seavy, M.; Roux, K.H. Ana o 3, an Important Cashew Nut (Anacardium Occidentale L.) Allergen of the 2S Albumin Family. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2005, 115, 1284–1290. [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Robotham, J.M.; Teuber, S.S.; Sathe, S.K.; Roux, K.H. Ana o 2, a Major Cashew (Anacardium Occidentale L.) Nut Allergen of the Legumin Family. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2003, 132, 27–39. [CrossRef]

- Ahn, K.; Bardina, L.; Grishina, G.; Beyer, K.; Sampson, H.A. Identification of Two Pistachio Allergens , Pis v 1 and Pis v 2 , Belonging to the 2S Albumin and 11S Globulin Family. Clinical & Experimental Allergy 2009, 39, 926–934. [CrossRef]

- Cabanillas, B.; Novak, N. Effects of Daily Food Processing on Allergenicity. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2017, 11, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Saiz, R.; Benedé, S.; Molina, E.; López-Expósito, I. Effect of Processing Technologies on the Allergenicity of Food Products. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2015, 55, 1902–1917. [CrossRef]

- Vanga, S.K.; Raghavan, V. Processing Effects On Tree Nut Allergens: A Review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2016, 57, 3794–3806. [CrossRef]

- Costa, J.; Bavaro, S.L.; Benedé, S.; Diaz-Perales, A.; Bueno-Diaz, C.; Gelencser, E.; Klueber, J.; Larré, C.; Lozano-Ojalvo, D.; Lupi, R.; et al. Are Physicochemical Properties Shaping the Allergenic Potency of Plant Allergens? Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2022, 62, 37–63.

- Linglin Fu; Bobby J. Cherayil; Haining Shi; Yanbo Wang; Yang Zhu Food Allergy From Molecular Mechanisms to Control Strategies; Springer, 2019;

- Valdelvira, R.; Garcia-Medina, G.; Crespo, J.F.; Cabanillas, B. Novel Alimentary Pasta Made of Chickpeas Has an Important Allergenic Content That Is Altered by Boiling in a Different Manner than Chickpea Seeds. Food Chem 2022, 395. [CrossRef]

- Masthoff, L.J.; Hoff, R.; Verhoeckx, K.C.M.; van Os-Medendorp, H.; Michelsen-Huisman, A.; Baumert, J.L.; Pasmans, S.G.; Meijer, Y.; Knulst, A.C. A Systematic Review of the Effect of Thermal Processing on the Allergenicity of Tree Nuts. Allergy 2013, 68, 983–993. [CrossRef]

- Cuadrado, C.; Sanchiz, Á.; Linacero, R. Nut Allergenicity: Effect of Food Processing. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Cuadrado, C.; Arribas, C.; Sanchiz, A.; Pedrosa, M.M.; Gamboa, P.; Betancor, D.; Blanco, C.; Cabanillas, B.; Linacero, R. Effects of Enzymatic Hydrolysis Combined with Pressured Heating on Tree Nut Allergenicity. Food Chem 2024, 451. [CrossRef]

- Hansen, K.S.; Skov, P.S.; Vieths, S.; Poulsen, L.K. Roasted Hazelnuts – Allergenic Activity Evaluated by Double-Blind , Placebo-Controlled Food Challenge. 2003, 1, 132–138.

- De Angelis, E.; Di Bona, D.; Pilolli, R.; Loiodice, R.; Luparelli, A.; Giliberti, L.; D’uggento, A.M.; Rossi, M.P.; Macchia, L.; Monaci, L. In Vivo and In Vitro Assessment and Proteomic Analysis of the Effectiveness of Physical Treatments in Reducing Allergenicity of Hazelnut Proteins. Nutrients 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- De Angelis, E.; Bavaro, S.L.; Forte, G.; Pilolli, R.; Monaci, L. Heat and Pressure Treatments on Almond Protein Stability and Change in Immunoreactivity after Simulated Human Digestion. Nutrients 2018, 10. [CrossRef]

- Cabanillas, B.; Maleki, S.J.; Rodriguez, J.; Cheng, H.; Teuber, S.S.; Wallowitz, M.L.; Muzquiz, M.; Pedrosa, M.M.; Linacero, R.; Burbano, C.; et al. Allergenic Properties and Differential Response of Walnut Subjected to Processing Treatments. Food Chem 2014, 157, 141–147. [CrossRef]

- Cuadrado, C.; Sanchiz, A.; Arribas, C.; Pedrosa, M.M.; Gamboa, P.; Betancor, D.; Blanco, C.; Cabanillas, B.; Linacero, R. Mitigation of Peanut Allergenic Reactivity by Combined Processing: Pressured Heating and Enzymatic Hydrolysis. Innovative Food Science and Emerging Technologies 2023, 86. [CrossRef]

- Cuadrado, C.; Sanchiz, A.; Vicente, F.; Ballesteros, I.; Linacero, R. Changes Induced by Pressure Processing on Immunoreactive Proteins of Tree Nuts. Molecules 2020, 25, 954–965. [CrossRef]

- Lopez, E.; Cuadrado, C.; Burbano, C.; Jimenez, M.A.; Rodriguez, J.; Crespo, J.F. Effects of Autoclaving and High Pressure on Allergenicity of Hazelnut Proteins. J Clin Bioinforma 2012, 2, 2043–9113. [CrossRef]

- Sanchiz, A.; Cuadrado, C.; Dieguez, M.C.; Ballesteros, I.; Rodriguez, J.; Crespo, J.F.; de las Cuevas, N.; Rueda, J.; Linacero, R.; Cabanillas, B.; et al. Thermal Processing Effects on Cashew and Pistachio Allergenicity. Food Chem 2018, 245, 595–602. [CrossRef]

- Cuadrado, C.; Cheng, H.; Sanchiz, Á.; Ballesteros, I.; Easson, M.; Grimm, C.C.; Dieguez, M. del C.; Linacero, R.; Burbano, C.; Maleki, S.J. Influence of Enzymatic Hydrolysis on the Allergenic Reactivity of Processed Cashew and Pistachio. Food Chem 2018, 241, 372–379. [CrossRef]

- Vicente, F.; Sanchiz, A.; Rodríguez-Pérez, R.; Pedrosa, M.; Quirce, S.; Haddad, J.; Besombes, C.; Linacero, R.; Allaf, K.; Cuadrado, C. Influence of Instant Controlled Pressure Drop (DIC) on Allergenic Potential of Tree Nuts. Molecules 2020, 25. [CrossRef]

- Pali-Schöll, I.; Untersmayr, E.; Klems, M.; Jensen-Jarolim, E. The Effect of Digestion and Digestibility on Allergenicity of Food. Nutrients 2018, 10. [CrossRef]

- Korte, R.; Bräcker, J.; Brockmeyer, J. Gastrointestinal Digestion of Hazelnut Allergens on Molecular Level: Elucidation of Degradation Kinetics and Resistant Immunoactive Peptides Using Mass Spectrometry. Mol Nutr Food Res 2017, 61, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- FAO/WHO Expert consultation on Allergenicity of Foods Evaluation of Allergenicity of Genetically Modified Foods;

- Bøgh, K.L.; Madsen, C.B. Food Allergens: Is There a Correlation between Stability to Digestion and Allergenicity? Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2016, 56, 1545–1567. [CrossRef]

- Minekus, M.; Alminger, M.; Alvito, P.; Ballance, S.; Bohn, T.; Bourlieu, C.; Carrière, F.; Boutrou, R.; Corredig, M.; Dupont, D.; et al. A Standardised Static in Vitro Digestion Method Suitable for Food-an International Consensus. Food Funct 2014, 5, 1113–1124. [CrossRef]

- Haddad, J.; Louka, N.; Gadouleau, M.; Juhel, F.; Allaf, K. Application Du Nouveau Procédé de Séchage/Texturation Par Détente Instantanée Contrôlée DIC Aux Poissons: Impact Sur Les Caractéristiques Physico-Chimiques Du Produit Fini. Science des Aliments 2001, 21, 481–498.

- AOAC Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International, 17th Edition 2003.

- Roux, K.H.; Teuber, S.S.; Sathe, S.K. Tree Nut Allergens. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2003, 131, 234–244. [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Guo, R.; White, B.L.; Yancey, A.; Sanders, T.H.; Davis, J.P.; Burks, A.W.; Kulis, M. Allergenic Properties of Enzymatically Hydrolyzed Peanut Flour Extracts. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2013, 162, 123–130. [CrossRef]

- Cabanillas, B.; Pedrosa, M.M.; Rodríguez, J.; Muzquiz, M.; Maleki, S.J.; Cuadrado, C.; Burbano, C.; Crespo, J.F. Influence of Enzymatic Hydrolysis on the Allergenicity of Roasted Peanut Protein Extract. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2012, 157, 41–50. [CrossRef]

- Villa, C.; Carriço-Sá, B.; Teixeira, C.S.S.; Dias, C.; Costa, R.; M. Pereira, C.; Mafra, I.; Costa, J. γ-Conglutin Immunoreactivity Is Differently Affected by Thermal Treatment and Gastrointestinal Digestion in Lupine Species. Foods 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Cabanillas, B.; Cuadrado, C.; Rodriguez, J.; Hart, J.; Burbano, C.; Crespo, J.F.; Novak, N. Potential Changes in the Allergenicity of Three Forms of Peanut after Thermal Processing. 2015, 183, 18–25. [CrossRef]

- Cabanillas, B.; Maleki, S.J.; Rodríguez, J.; Burbano, C.; Muzquiz, M.; Jiménez, M.A.; Pedrosa, M.M.; Cuadrado, C.; Crespo, J.F. Heat and Pressure Treatments Effects on Peanut Allergenicity. Food Chem 2012, 132, 360–366. [CrossRef]

- Bueno-Díaz, C.; Martín-Pedraza, L.; Parrón, J.; Cuesta-Herranz, J.; Cabanillas, B.; Pastor-Vargas, C.; Batanero, E.; Villalba, M. Characterization of Relevant Biomarkers for the Diagnosis of Food Allergies: An Overview of the 2s Albumin Family. Foods 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- Maleki, S.J.; Schmitt, D.A.; Galeano, M.; Hurlburt, B.K. Comparison of the Digestibility of the Major Peanut Allergens in Thermally Processed Peanuts and in Pure Form. Foods 2014, 3, 290–303. [CrossRef]

- Prodić, I.; Smiljanić, K.; Nagl, C.; Ballmer-Weber, B.; Hoffmann-Sommergruber, K.; Veličković, T.Ć. INFOGEST Digestion Assay of Raw and Roasted Hazelnuts and Its Impact on Allergens and Their IgE Binding Activity. Foods 2022, 11. [CrossRef]

- Reitsma, M.; Bastiaan-Net, S.; Sforza, S.; Van Der Valk, J.P.M.; Van Gerth Van Wijk, R.; Savelkoul, H.F.J.; De Jong, N.W.; Wichers, H.J. Purification and Characterization of Anacardium Occidentale (Cashew) Allergens Ana o 1, Ana o 2, and Ana o 3. J Agric Food Chem 2016, 64, 1191–1201. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Experimental procedure for the in vitro static digestion model and performed analysis for peanut, hazelnut, pistachio and cashew allergens. H – heat; P – pressure; CS – control sample.

Figure 1.

Experimental procedure for the in vitro static digestion model and performed analysis for peanut, hazelnut, pistachio and cashew allergens. H – heat; P – pressure; CS – control sample.

Figure 2.

Peanut protein samples were analysed by SDS-PAGE electrophoresis in 4-20% tris-glycine protein gels (A) and by immunoblotting using a pool of sera from peanut allergic patients (grouped in 2S albumins (B) or LTP allergic individuals (C)). Lane 2: Control, raw whole peanut flour (CS). Lane 3: Control digested peanut (DS). Lane 4: boiled for 60 min whole peanut flour. Lane 5: boiled for 60 min digested peanut DS. Lane 6: AU 138°C, 30 min whole peanut flour. Lane 7: AU 138°C 30 min digested peanut DS. Lane 8: DIC 7b, 2 min whole peanut flour. Lane 9: DIC 7 b, 2 min digested peanut DS. Lanes 1 and 10: Molecular Weight Marker Precision Plus and See Blue (10-250 kDa, BioRad and 3-198 kDa, Invitrogen, respectively). Laemmli Loading buffer containing 4% of β-mercaptoethanol was used in all samples. Digested samples are highlighted with blue arrows above the figure.

Figure 2.

Peanut protein samples were analysed by SDS-PAGE electrophoresis in 4-20% tris-glycine protein gels (A) and by immunoblotting using a pool of sera from peanut allergic patients (grouped in 2S albumins (B) or LTP allergic individuals (C)). Lane 2: Control, raw whole peanut flour (CS). Lane 3: Control digested peanut (DS). Lane 4: boiled for 60 min whole peanut flour. Lane 5: boiled for 60 min digested peanut DS. Lane 6: AU 138°C, 30 min whole peanut flour. Lane 7: AU 138°C 30 min digested peanut DS. Lane 8: DIC 7b, 2 min whole peanut flour. Lane 9: DIC 7 b, 2 min digested peanut DS. Lanes 1 and 10: Molecular Weight Marker Precision Plus and See Blue (10-250 kDa, BioRad and 3-198 kDa, Invitrogen, respectively). Laemmli Loading buffer containing 4% of β-mercaptoethanol was used in all samples. Digested samples are highlighted with blue arrows above the figure.

Figure 3.

Hazelnut protein samples were analysed by SDS-PAGE electrophoresis in MES 4-12% protein gels (A) and by immunoblotting using a pool of sera from hazelnut allergic patients (distributed in 2S albumins (B) or LTP allergic individuals (C)). Lane 2: Control, raw whole hazelnut flour (CS). Lane 3: Control digested hazelnut (DS). Lane 4: boiled for 60 min whole hazelnut flour. Lane 5: boiled for 60 min digested hazelnut DS. Lane 6: AU 138°C, 30 min whole hazelnut flour. Lane 7: AU 138°C 30 min digested hazelnut DS. Lane 8: DIC 7b, 2 min whole hazelnut flour. Lane 9: DIC 7 b, 2 min digested hazelnut DS. Lanes 1 and 10: Molecular Weight Markers Precision Plus and See Blue (10-250 kDa, BioRad and 3-198kDa, Invitrogen, respectively). Bolt LDS Sample Buffer (Invitrogen) + Sample reducing agent was used in all samples. Digested samples are highlighted with blue arrows above the figure.

Figure 3.

Hazelnut protein samples were analysed by SDS-PAGE electrophoresis in MES 4-12% protein gels (A) and by immunoblotting using a pool of sera from hazelnut allergic patients (distributed in 2S albumins (B) or LTP allergic individuals (C)). Lane 2: Control, raw whole hazelnut flour (CS). Lane 3: Control digested hazelnut (DS). Lane 4: boiled for 60 min whole hazelnut flour. Lane 5: boiled for 60 min digested hazelnut DS. Lane 6: AU 138°C, 30 min whole hazelnut flour. Lane 7: AU 138°C 30 min digested hazelnut DS. Lane 8: DIC 7b, 2 min whole hazelnut flour. Lane 9: DIC 7 b, 2 min digested hazelnut DS. Lanes 1 and 10: Molecular Weight Markers Precision Plus and See Blue (10-250 kDa, BioRad and 3-198kDa, Invitrogen, respectively). Bolt LDS Sample Buffer (Invitrogen) + Sample reducing agent was used in all samples. Digested samples are highlighted with blue arrows above the figure.

Figure 4.

Pistachio protein samples were analysed by SDS-PAGE electrophoresis in MES 4-12% protein gels (A) and by immunoblotting using a pool of sera from pistachio allergic patients (B). Lane 2: Control, raw whole pistachio flour (CS). Lane 3: Control digested pistachio (DS). Lane 4: boiled for 60 min whole pistachio flour. Lane 5: boiled for 60 min digested pistachio DS. Lane 6: AU 138°C, 30 min whole pistachio flour. Lane 7: AU 138°C 30 min digested pistachio DS. Lane 8: DIC 7b, 2 min whole pistachio flour. Lane 9: DIC 7 b, 2 min digested pistachio DS. Lanes 1 and 10: Molecular Weight Markers Precision Plus and See Blue (10-250 kDa, BioRad and 3-198 kDa, Invitrogen, respectively). Bolt LDS Sample Buffer (Invitrogen) + Sample reducing agent was used in all samples. Digested samples are highlighted with blue arrows above the figure.

Figure 4.

Pistachio protein samples were analysed by SDS-PAGE electrophoresis in MES 4-12% protein gels (A) and by immunoblotting using a pool of sera from pistachio allergic patients (B). Lane 2: Control, raw whole pistachio flour (CS). Lane 3: Control digested pistachio (DS). Lane 4: boiled for 60 min whole pistachio flour. Lane 5: boiled for 60 min digested pistachio DS. Lane 6: AU 138°C, 30 min whole pistachio flour. Lane 7: AU 138°C 30 min digested pistachio DS. Lane 8: DIC 7b, 2 min whole pistachio flour. Lane 9: DIC 7 b, 2 min digested pistachio DS. Lanes 1 and 10: Molecular Weight Markers Precision Plus and See Blue (10-250 kDa, BioRad and 3-198 kDa, Invitrogen, respectively). Bolt LDS Sample Buffer (Invitrogen) + Sample reducing agent was used in all samples. Digested samples are highlighted with blue arrows above the figure.

Figure 5.

Cashew protein samples were analysed by SDS-PAGE electrophoresis in MES 4-12% protein gels (A) and by immunoblotting using a pool of sera from cashew allergic patients (B). Lane 2: Control, raw whole cashew flour (CS). Lane 3: Control digested cashew (DS). Lane 4: boiled for 60 min whole cashew flour. Lane 5: boiled for 60 min digested cashew DS. Lane 6: AU 138°C, 30 min whole cashew flour. Lane 7: AU 138°C 30 min digested cashew DS. Lane 8: DIC 7b, 2 min whole cashew flour. Lane 9: DIC 7 b, 2 min digested cashew DS. Lanes 1 and 10: Molecular Weight Markers Precision Plus and See Blue (10-250 kDa, BioRad and 3-198kDa, Invitrogen, respectively). Bolt LDS Sample Buffer (Invitrogen) + Sample reducing agent was used in all samples. Digested samples are highlighted with blue arrows above the figure.

Figure 5.

Cashew protein samples were analysed by SDS-PAGE electrophoresis in MES 4-12% protein gels (A) and by immunoblotting using a pool of sera from cashew allergic patients (B). Lane 2: Control, raw whole cashew flour (CS). Lane 3: Control digested cashew (DS). Lane 4: boiled for 60 min whole cashew flour. Lane 5: boiled for 60 min digested cashew DS. Lane 6: AU 138°C, 30 min whole cashew flour. Lane 7: AU 138°C 30 min digested cashew DS. Lane 8: DIC 7b, 2 min whole cashew flour. Lane 9: DIC 7 b, 2 min digested cashew DS. Lanes 1 and 10: Molecular Weight Markers Precision Plus and See Blue (10-250 kDa, BioRad and 3-198kDa, Invitrogen, respectively). Bolt LDS Sample Buffer (Invitrogen) + Sample reducing agent was used in all samples. Digested samples are highlighted with blue arrows above the figure.

Figure 6.

Competitive ELISA inhibition of the IgE binding to untreated or raw peanut (A) or hazelnut (B), by increasing concentration from 0.001 to 0.1 mg/ml of raw, boiled, autoclaved or DIC treated with and without in vitro digestion. Below each figure, percentage of inhibition is shown in the table. Means in the same column followed for the same superscript are not significantly different according to Duncan’s test. Colour code is indicated in the tables.

Figure 6.

Competitive ELISA inhibition of the IgE binding to untreated or raw peanut (A) or hazelnut (B), by increasing concentration from 0.001 to 0.1 mg/ml of raw, boiled, autoclaved or DIC treated with and without in vitro digestion. Below each figure, percentage of inhibition is shown in the table. Means in the same column followed for the same superscript are not significantly different according to Duncan’s test. Colour code is indicated in the tables.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).