Submitted:

28 July 2025

Posted:

06 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Problem Statement

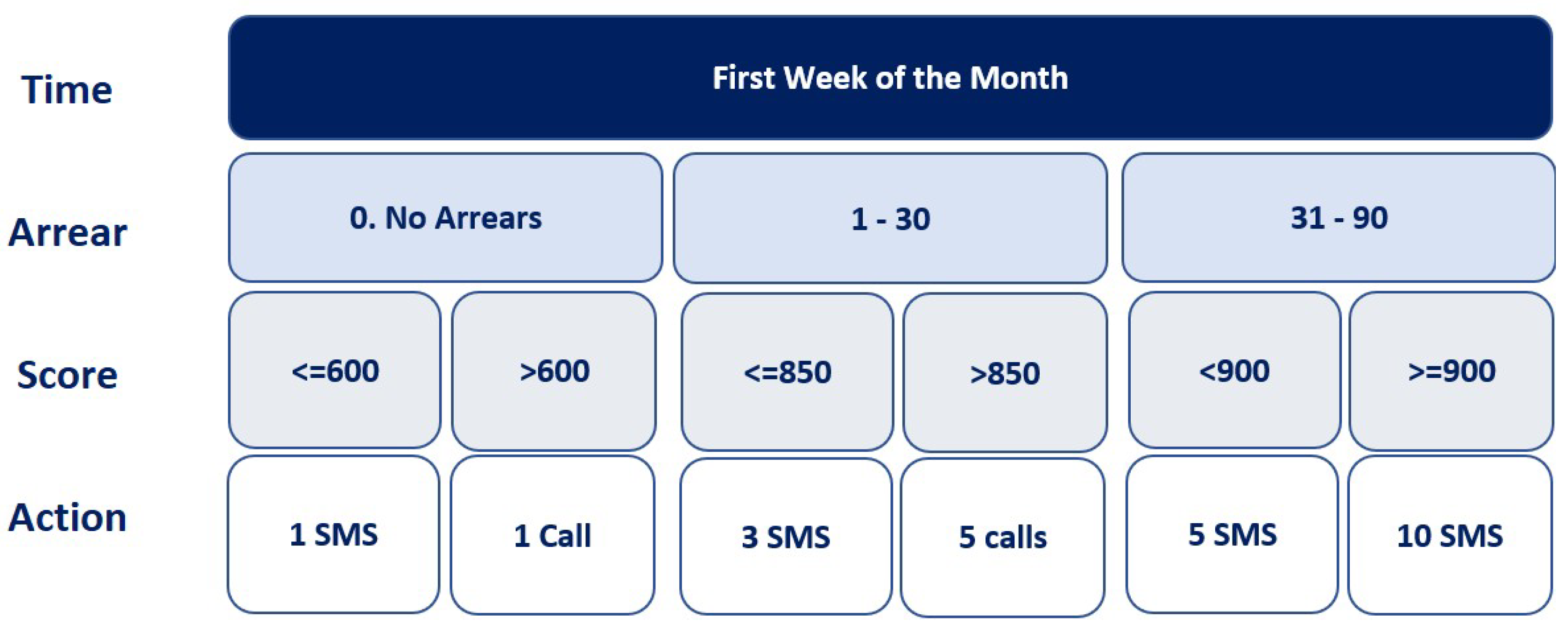

1.2. Scoring Models for Credit Collection

- 0 - No Arrears segment

- 1 - 30 segment

- 31 - 60 segment

- 61 - 90 segment

- 91 - 120 segment

- More than 120 segment

1.3. Literature Review

1.3.1. Credit Scoring with Logistic Regression

1.3.2. Credit Scoring with XGBoost

1.3.3. Credit Scoring with Artificial Neural Networks

1.3.4. Performance Evaluation

1.3.5. Comparison of Models

2. Methodology

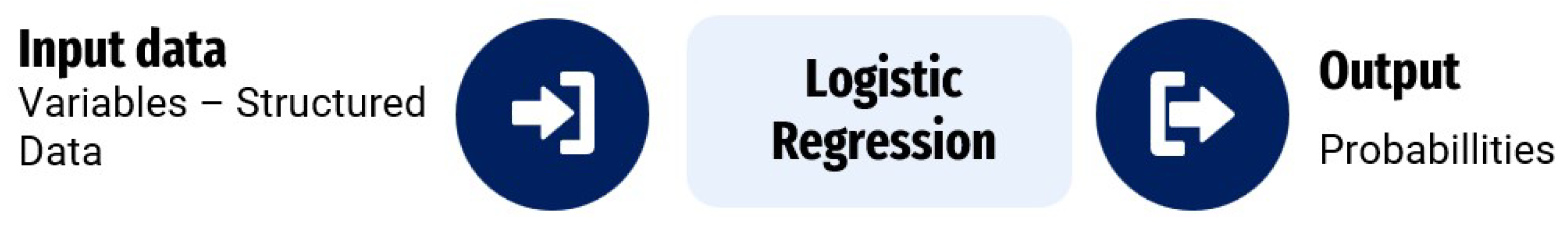

2.0.1. Kolmogorov-Smirnov Tests

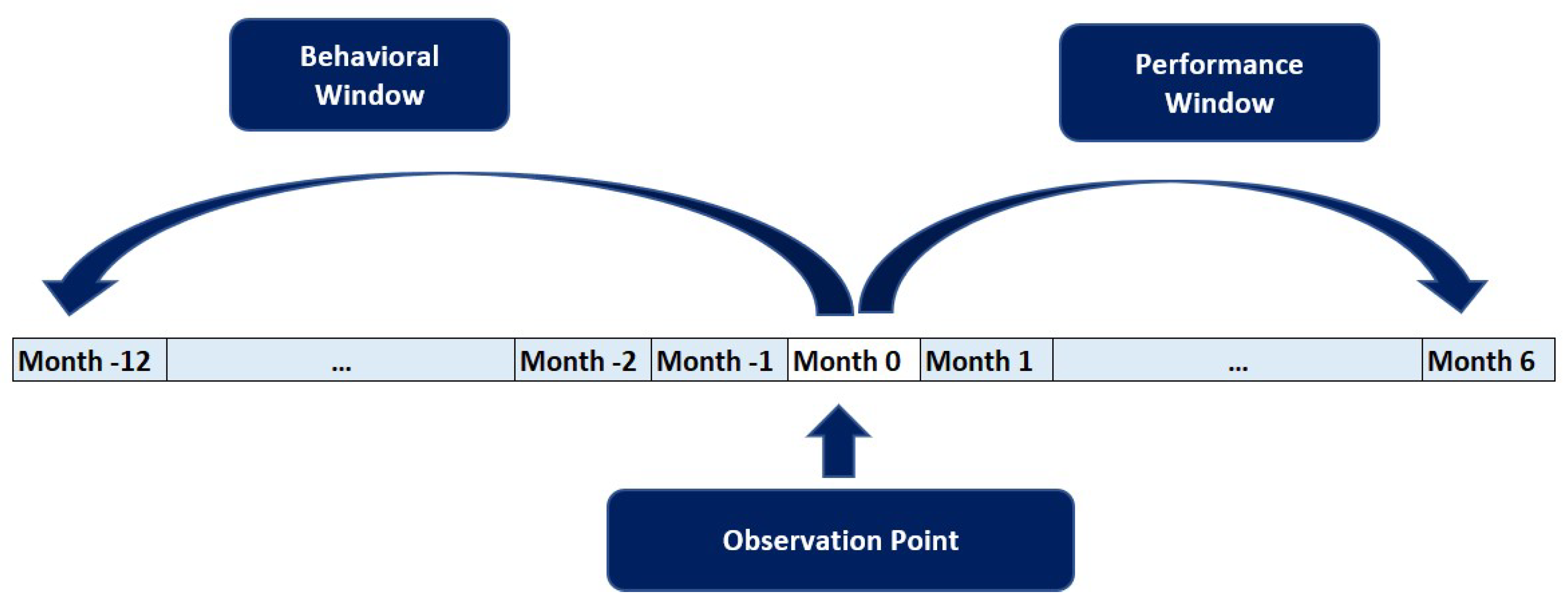

2.1. Data Sample Selection

2.2. Dependent Variable Setting

3. Train and Test Models

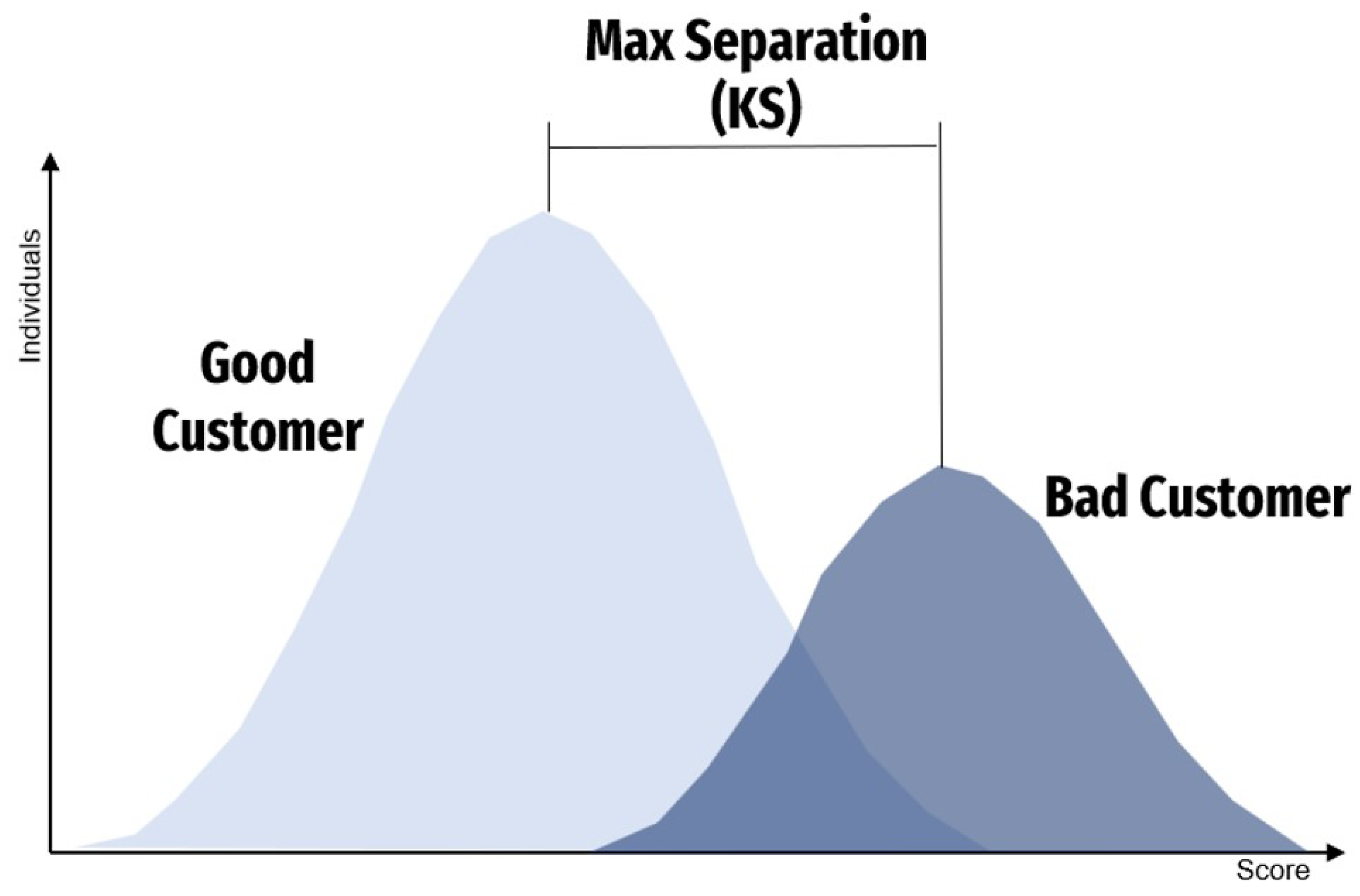

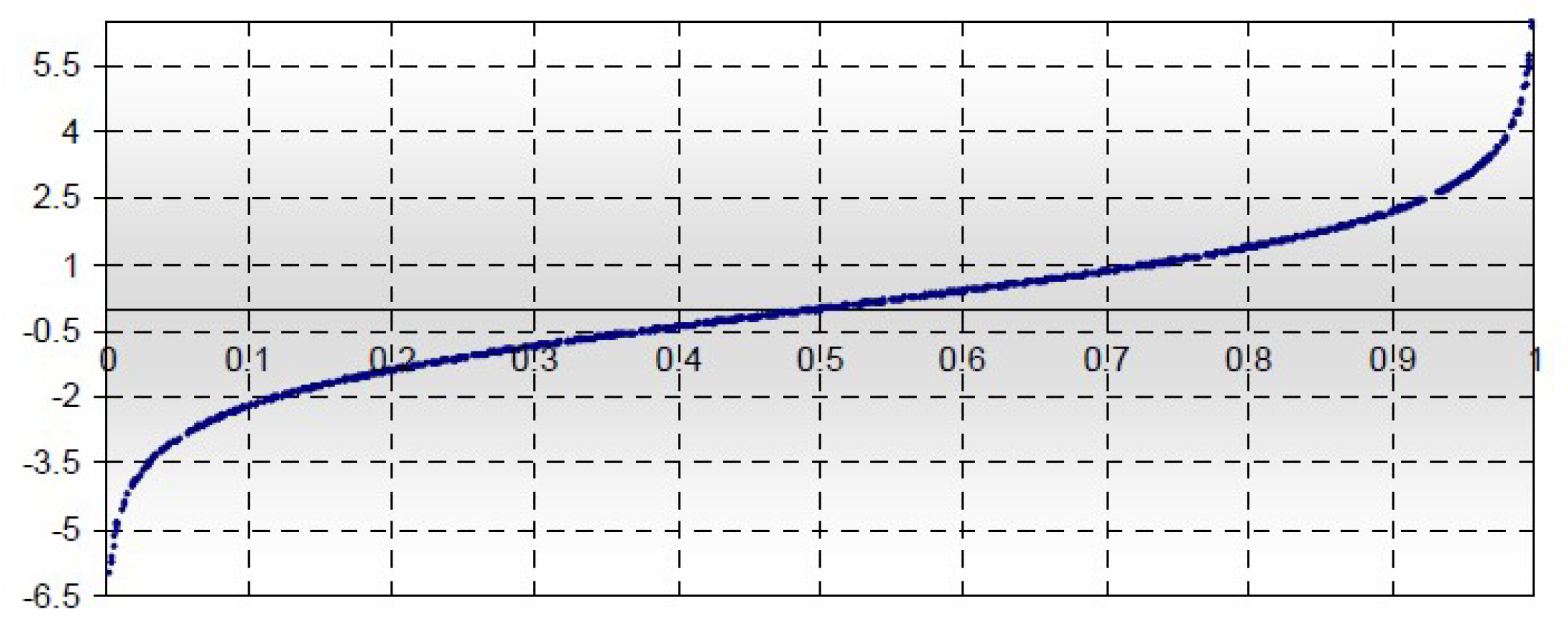

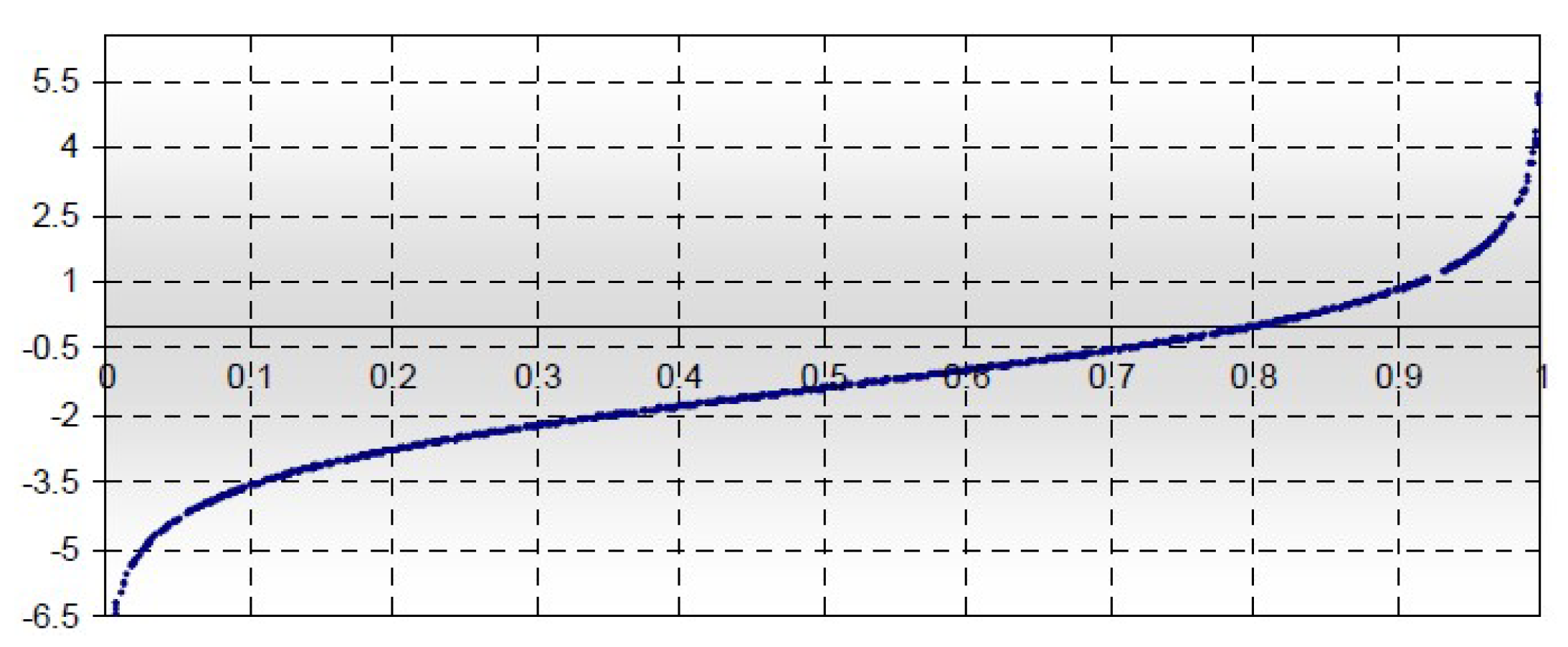

3.1. Logistic Regression Training

3.1.1. Unbalanced Problem

3.2. Extreme Gradient Boosting Training

3.2.1. Hyperparameter Selected and Tuning

3.2.2. XGBoost Hyperparameter Nrounds

3.2.3. XGBoost Hyperparameter Eta

3.2.4. XGBoost Hyperparameter max_depth

3.2.5. XGBoost Hyperparameter min_child_weight

3.2.6. XGBoost Hyperparameter Subsample

3.2.7. XGBoost Hyperparameter colsample_bytree

3.2.8. XGBoost Hyperparameter Lambda

3.3. Artificial Neural Networks Training

- Layers, which are combined into a network (or model)

- The input data and corresponding targets

- The loss function, which defines the feedback signal used for learning

- The optimizer, which determines how learning proceeds

3.3.1. Building the Neural Networks

- How many layers to use?

- How many hidden units to choose for each layer?

3.3.2. Adding Dropout

4. Interpretability

4.1. Interpretation of Logistic Regression Coefficients

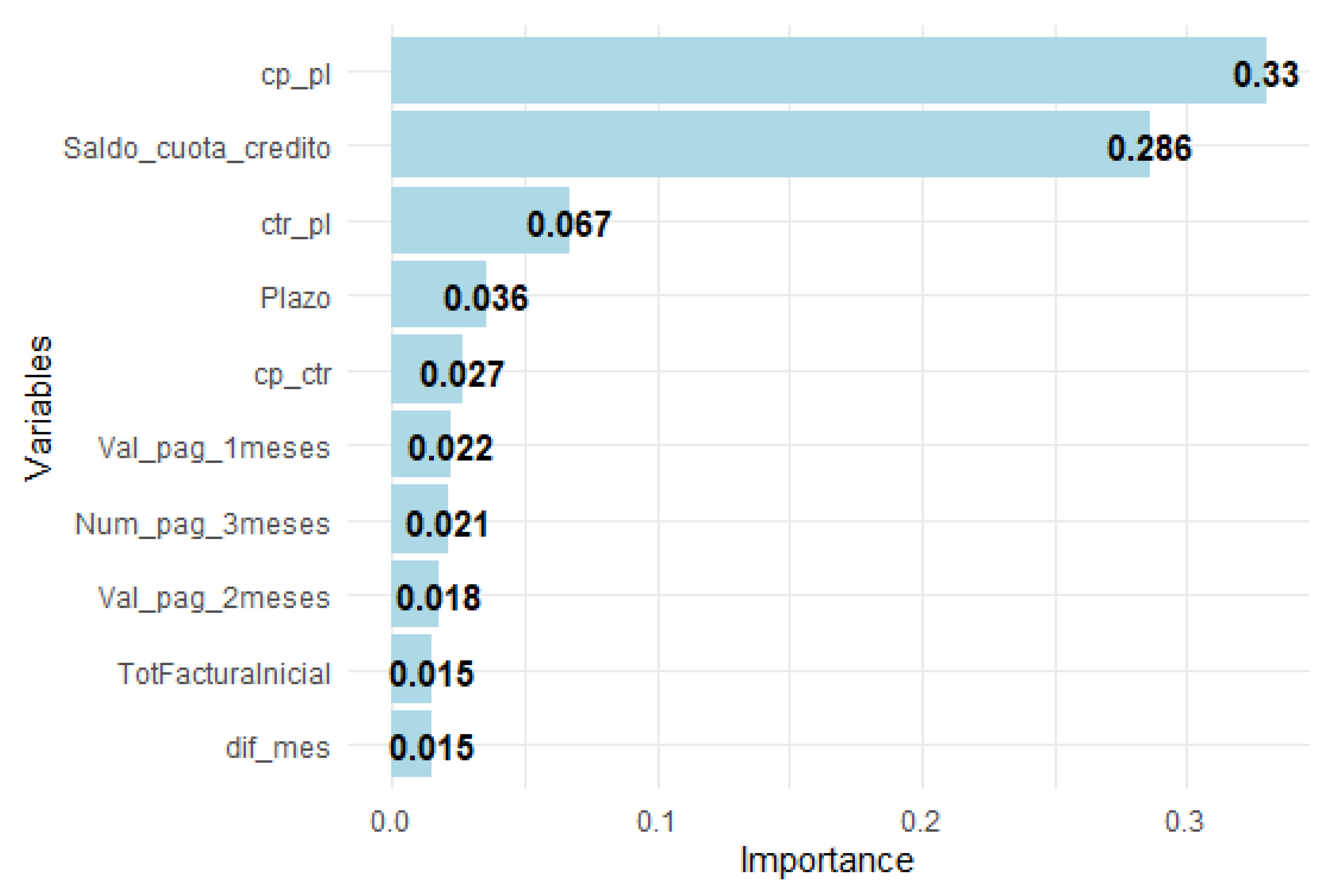

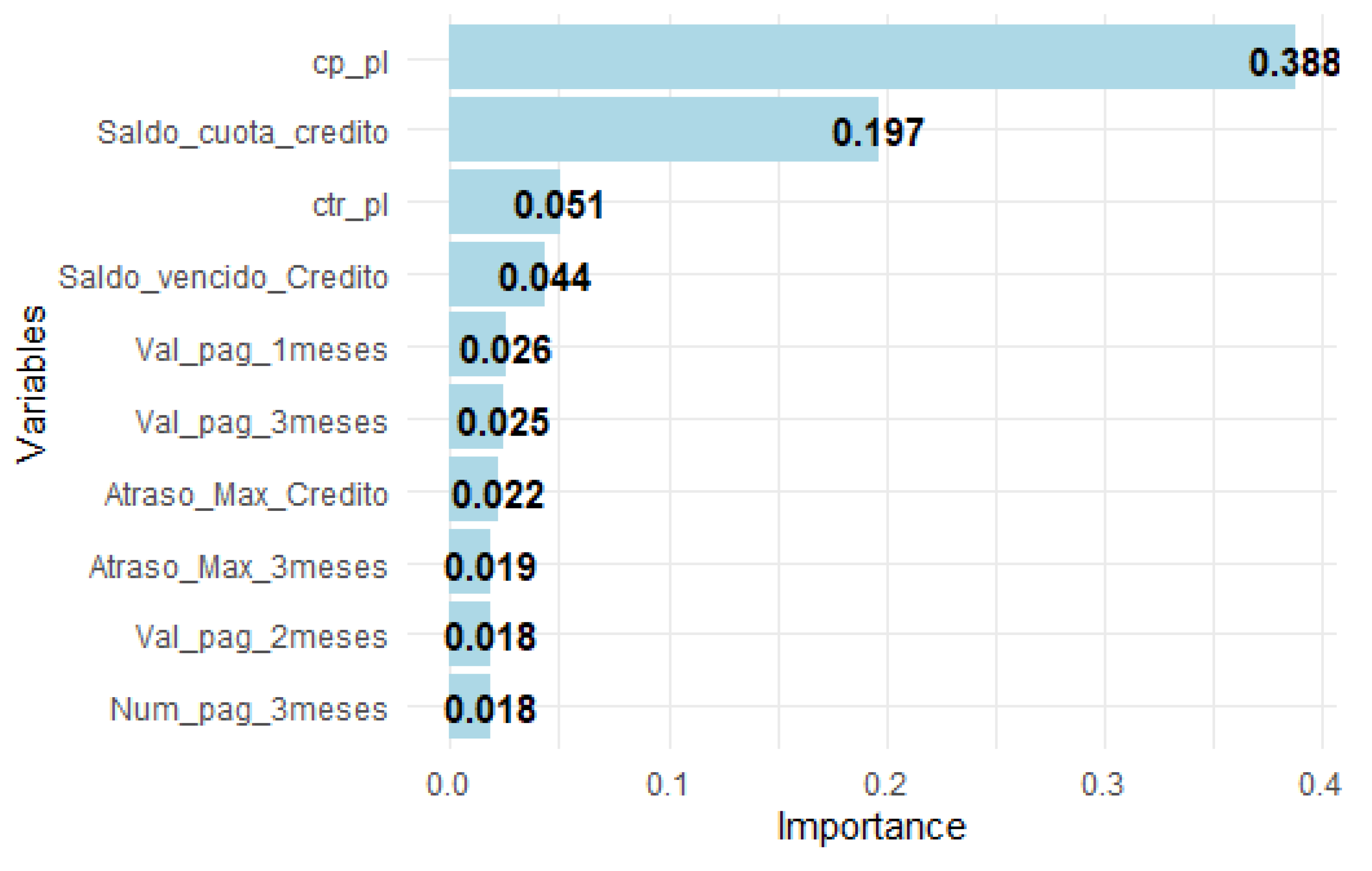

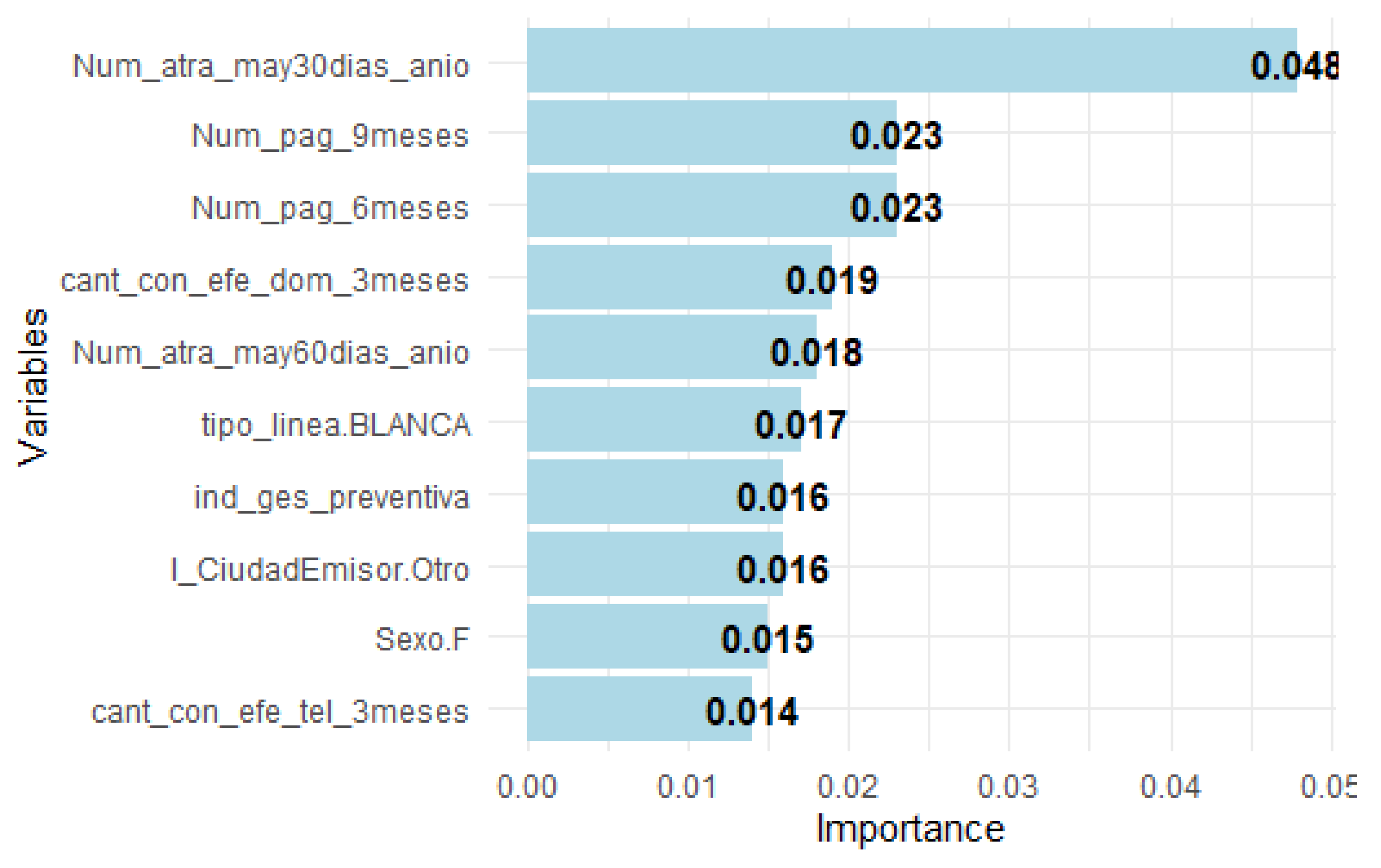

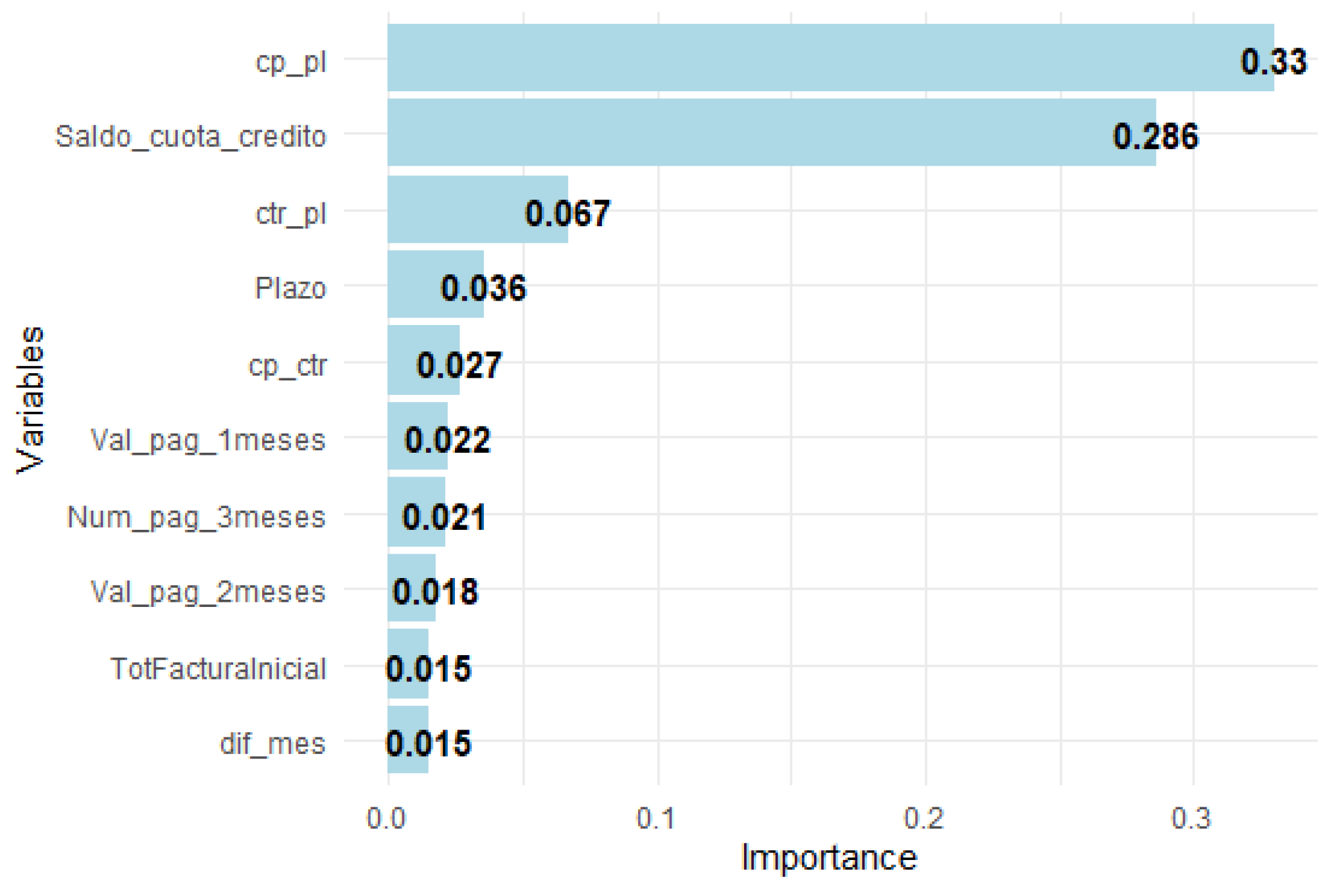

4.2. Interpretation of XGBoost Models Results

5. Results and Discussion

- In Segment 0 Models, XGBoost (63.36%) and ANN (61.84%) outperform LR (56.42%).

- In Segment Model 1 - 30, XGBoost (51.38%) and ANN (50.35%) also outperform LR (47.32%). However, in the 31 - 90 Segment Model, ANN (38.77%) outperforms LR (36.62%), but XGBoost (34.47%) does not.

- Finally, in the All Segments Model, both XGBoost (74.05%) and ANN (73.59%) outperform LR (71.01%).

6. Conclusions

- This paper compares three supervised learning models: logistic regression, XGBoost, and artificial neural networks, using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) statistic as a performance metric. The XGBoost algorithm consistently demonstrated superior performance across various segments, achieving accuracy rates of 63.36% for segments with no lags, 51.38% for segments with 1-30 lags, and 74.05% when all segments were analyzed together. These results indicate that XGBoost is more effective for binary classification compared to both logistic regression and neural networks.

- Although logistic regression requires more time for preprocessing and training due to feature engineering and sample balancing, its performance in terms of KS did not outperform XGBoost and neural networks in any of the arrears segments.

- In the 31-90 arrears segment, neural networks outperformed XGBoost with a 38.77% KS value, indicating that the complexity and adaptability of neural networks can be advantageous in certain scenarios, despite the longer training time required.

- The interpretation of XGBoost results relies on how much each variable contributes to the splits in the random trees. In contrast, neural networks are still being studied to achieve satisfactory interpretability. This indicates that when developing a scoring model, one must choose between interpretability and predictability. If the goal is to enhance predictive or discriminative power, XGBoost or neural networks are preferred options. These algorithms can be effectively utilized during the placement, servicing, and collection phases of the credit cycle, as there is a larger volume of data to analyze. This is particularly relevant in collections, where results can change rapidly.

- Future work involves exploring combinations of models to leverage the individual strengths of algorithms like XGBoost and neural networks, aiming to improve prediction accuracy across different segments or scenarios.

Appendix A. Set of Variables for Training Models

| Alias | Variable | Description |

|---|---|---|

| M1 | Atraso_Max_3meses | Maximum arrears in the last three months |

| M2 | Atraso_Max_6meses | Maximum arrears in the last six months |

| M3 | Atraso_Max_9meses | Maximum arrears in the last nine months |

| M4 | Atraso_Max_Credito | Maximum arrears since the start of the loan |

| M5 | Atraso_Prom_12meses | Average arrears over the last 12 months |

| M6 | Atraso_Prom_3meses | Average arrears over the last three months |

| M7 | Atraso_Prom_Credito | Average arrears since the start of the loan |

| M8 | Cadena | Distribution chain to which the purchased product belongs |

| M9 | canal_vta | Sales channel through which the loan was acquired |

| M10 | cant_con_efe_dom_12meses | Number of direct contacts at the customer’s home in the last twelve months |

| M11 | cant_con_efe_dom_3meses | Number of direct contacts at the customer’s home in the last three months |

| M12 | cant_con_efe_dom_6meses | Number of direct contacts at the customer’s home in the last six months |

| M13 | cant_con_efe_dom_9mese | Number of direct contacts at the customer’s home in the last nine months |

| M14 | cant_con_efe_tel_12meses | Number of phone contacts with the customer in the last twelve months |

| M15 | cant_con_efe_tel_6meses | Number of phone contacts with the customer in the last six months |

| M16 | cant_con_efe_tel_9meses | Number of phone contacts with the customer in the last nine months |

| M17 | cant_con_efe_tel_mesant | Number of phone contacts with the customer in the previous month |

| M18 | cant_ges_dom_12meses | Number of visits to the customer’s home in the last twelve months |

| M19 | cant_ges_dom_3meses | Number of visits to the customer’s home in the last three months |

| M20 | cant_ges_dom_9meses | Number of visits to the customer’s home in the last nine months |

| M21 | cant_ges_efe_dom_12meses | Number of unsuccessful home visits in the last twelve months |

| M22 | cant_ges_efe_dom_6meses | Number of unsuccessful home visits in the last six months |

| M23 | cant_ges_efe_dom_9meses | Number of unsuccessful home visits in the last nine months |

| M24 | cant_ges_efe_dom_mesant | Number of unsuccessful home visits in the previous month |

| M25 | cant_ges_efe_tel_9meses | Number of unsuccessful phone calls in the last nine months |

| M26 | cant_ges_efe_tel_mesant | Number of unsuccessful phone calls in the previous month |

| M27 | cant_ges_tel_12meses | Number of phone calls in the last 12 months |

| M28 | cant_ges_tel_6meses | Number of phone calls in the last 6 months |

| M29 | cant_ges_tel_9meses | Number of phone calls in the last 9 months |

| M30 | Cant_Num_Telef_Referen | Number of reference phone numbers held by the customer |

| M31 | Cant_Productos | Number of billed products |

| M32 | CapitalInteres | Capital with interest |

| M33 | cp_ctr | Ratio of paid installments to installments due |

| M34 | cp_pl | Ratio of paid installments to loan term |

| M35 | ctr_pl | Ratio of remaining installments to loan term |

| M36 | Cuotas_pagad_credito | Number of installments paid on the loan |

| M37 | Cuotas_pendt_credito | Number of installments due |

| M38 | CuotasGratis | Indicator of whether the customer has a free installment promotion |

| M39 | desc_mejor_resp_dom_3meses | Best response obtained from home visits in the last three months |

| M40 | desc_mejor_resp_dom_6meses | Best response obtained from home visits in the last six months |

| M41 | desc_mejor_resp_dom_9meses | Best response obtained from home visits in the last nine months |

| M42 | desc_mejor_resp_tel_6meses | Best response obtained from phone calls in the last six months |

| M43 | dif_mes | Number of months between the loan disbursement and the reporting date |

| M44 | Edad | Customer’s age in years at the time of data extraction |

| M45 | ID_Num_Telef_Particular1 | Indicator of whether the customer has a landline at home |

| M46 | ind_ges_preventiva | Indicator of whether preventive management was performed |

| M47 | IngresosPropios | Estimated value of customer’s own income |

| M48 | Inicial | Total initial payment at the time the loan was taken |

| M49 | Inicialbono | Amount less than an installment paid at the start of the loan |

| M50 | linea | Product line |

| M51 | MesesGracia | Number of grace months before the first installment due date |

| M52 | Num_atra_may_60dias_anio | Number of delinquencies over 60 days in the past year |

| M53 | Num_atra_may30dias_anio | Number of delinquencies over 30 days in the past year |

| M54 | Num_pag_12meses | Number of payments made in the last twelve months |

| M55 | Num_pag_3meses | Number of payments made in the last three months |

| M56 | Num_pag_6meses | Number of payments made in the last six months |

| M57 | Num_pag_9meses | Number of payments made in the last nine months |

| M58 | Pago_efec_1mes | Payment made for the installment due on the reporting date |

| M59 | Plazo | Total number of loan installments |

| M60 | RalacionTrabajo | Indicator of the customer’s current employment status |

| M61 | Rango_mora_max_mesant | Maximum arrear range in the month prior to the reporting date |

| M62 | Rango_mora_mesact | Current delinquency range as of the reporting month |

| M63 | region | Geographic region of the customer’s home |

| M64 | Saldo_cuota_credito | Outstanding installment balance |

| M65 | Saldo_vencido_Credito | Overdue loan balance |

| M66 | Sexo | Gender as self-identified by the customer |

| M67 | TasaCredito | Effective interest rate of the loan |

| M68 | tipoinicialbono | Type of initial bonus received when the loan was taken |

| M69 | TotFacturaInicial | Total billed amount excluding interest |

| M70 | Val_pag_1meses | Amount paid the month before the reporting date |

| M71 | Val_pag_2meses | Amount paid two months before the reporting date |

| M72 | Val_pag_3meses | Amount paid three months before the reporting date |

| M73 | ValorCuota | Total installment amount including interest |

Appendix B. Logistic Regression and XG Boost Results

| Alias | Beta Estimated | Description |

|---|---|---|

| V1 | -1.74701 | M34 <= 0.56 & M58(0; 77.62] & M55(2;3] |

| V2 | -1.74726 | M34 <= 0.56 & M58(77.62; 102.88] & M72(159.2;293.94] |

| V3 | -0.40177 | M34(0.56;0.77] |

| V4 | 1.61231 | M34 > 0.77 |

| V5 | 0.87094 | M64 <= 197.79 |

| V6 | -0.85414 | M64 > 1121.02 & M33(0.8;1] & M70 > 24.61 |

| V7 | -0.27386 | M35 <= 6.5 & M56(5;6] & M36 <= 11 |

| V8 | 0.10523 | (M38 == BONO INICIAL + N CUOTAS GRATIS | M38 == CUOTAS GRATIS) & M49 <= 0 & (M63 == QUITO | M63 == GUAYAQUIL) |

| V9 | -0.46984 | M38 == NULL |

| V10 | 0.08418 | M67(0;15] & M48 > 59 |

| V11 | -0.15439 | (M68 == NULL & M71(102.58;136.09] & M73(47.18;77.8]) | (M68 == NULL & M71(153.54;236.16] & M73 > 77.8) |

| V12 | -0.11464 | M31 > 2 & (M50 == Tienda | M50 == Recojo) & M60 == NO |

| V13 | -0.67996 | M35 <= 0.75 |

| Intercept | -0.80574 |

| Alias | Beta Estimated | Description |

|---|---|---|

| V1 | 1.56644 | M64 ≤ 123.25 |

| V2 | -0.00106 | M64(123.25;311.02] (cont) |

| V3 | -0.81316 | M64 > 922.58 & M37 ≤ 0 & M58(58.87;117.52] |

| V4 | -0.23837 | M34(0.28;0.65] & M55(2;3] & M4 ≤ 5 |

| V5 | 0.70477 | M34 > 0.83 (cont) |

| V6 | -0.17784 | M55(2;3] & M4 ≤ 5 |

| V7 | -0.54773 | M35 ≤ 3.2 & M65 ≤ 0 |

| V8 | 0.64187 | M35 > 0.87 (cont) |

| V9 | -0.01297 | M36(3;14] (cont) |

| Intercept | -0.39452 |

| Alias | Beta Estimated | Variable |

|---|---|---|

| V1 | -0.52883 | M1 ≤ 11 |

| V2 | -0.58201 | M1(11;27] & M64 > 297.19 |

| V3 | 0.19268 | M1 > 42 |

| V4 | -0.30622 | M3(29;45] |

| V5 | 0.51679 | M3(45;55] & M58 ≤ 0 |

| V6 | 0.77430 | M6 > 49.67 & M53 ≤ 2 |

| V7 | 0.12466 | M52 ≤ 0 & M65 > 108.23 |

| V8 | 0.16562 | (M50 == VIDEO M50 == AUDIO M50 == CONSTRUCCION) & M15 ≤ 0 & M69 ≤ 2046.82 |

| V9 | 0.16522 | (M39 == MENSAJE A TERCEROS M39 == CONTACTO SIN COMPROMISO) & M28 > 10 |

| V10 | 0.18916 | M12 ≤ 0 & M26 ≤ 0 & M47 ≤ 353 |

| Intercept | 0.69485 |

References

- Arnold, T. B.; Emerson, J. W. Nonparametric goodness-of-fit tests for discrete null distributions. R Journal 2011, 3(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartz, E. , Bartz-Beielstein, T., Zaefferer, M., & Mersmann, O. (2023). Hyperparameter tuning for machine and deep learning with r: A practical guide. [CrossRef]

- Bussmann, N. , Giudici, P., Marinelli, D., & Papenbrock, J. 2021. Explainable machine learning in credit risk management. Computational Economics.

- Capelo Vinza, J. A. (2012). Modelo de aprobación de tarjetas de crédito en la población ecuatoriana bancarizada a través de una metodología analítica, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T. , & Guestrin, C. 2016. Xgboost: A scalable tree boosting system. InProceedings of the 22nd acm sigkdd international conference on knowledge discovery and data mining (pp. 785–794).

- Chen, Y. , Wang, H., Han, Y., Feng, Y., & Lu, H. (2024). Comparison of machine learning models in credit risk assessment. ( 2024). Comparison of machine learning models in credit risk assessment. Applied and Computational Engineering74, 278–288.

- Chollet, F. 2018. Deep learning with R/François Chollet; with JJ Allaire. Deep learn. R.

- Cifuentes Baquero, N. , & Gutiérrez Murcia, L. (2022). Modelo predictivo de la probabilidad de aumento de los días de mora para usuarios de tarjeta de crédito.

- Deisenroth, M. P. , Faisal, A. A., & Ong, C. S. (2020). Mathematics for machine learning.

- Ertel, W. (2018). Introduction to artificial intelligence.

- Galindo, J. , & Tamayo, P. (2000). Credit risk assessment using statistical and machine learning: basic methodology and risk modeling applications. Computational economics, 15.

- Hernández, R. , Fernández, C., Baptista, P., et al. (2014). Metodología de la investigación, m: méxico.

- Iñiguez, C. , & Morales, M. (2009). Selección de perfiles de clientes mediante regresión logística para muestras desproporcionadas, validación, monitoreo y aplicación en la proyección de provisiones. Escuela Politécnica Nacional, Ecuador.

- Jácome Jara, M. S. (2014). Construcción de un modelo estadístico para calcular el riesgo de deterioro de una cartera de microcréditos y propuesta de un sistema de gestión para la recuperación de la cartera en una empresa de cobranzas, E: Quito, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, D. B. , & Solomon, A. (2002). Managing a consumer lending business. (No Title).

- Li, Z. Extracting spatial effects from machine learning model using local interpretation method: An example of SHAP and XGBoost. Computers, Environment and Urban Systems 96 2022, 96, 101845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddala, G. S. , Contreras García, J., Lozano López, V., García Ferrer, A., et al. (1985). Econometría.

- Massey Jr, F. J. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for goodness of fit. Journal of the American statistical Association 1951, 46(253), 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnar, C. Interpretable machine learning. 2021. Available online: https://fedefliguer.github.io/AAI/redes-neuronales.html (accessed on day month year).

- Pérez Tatamués, A. E. (2014). Modelo de activación de tarjetas de crédito en el mercado crediticio ecuatoriano a través de una metodología analítica y automatizada en r, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Reche, J. L. C. (2013). Regresión logística. Tratamiento computacional con R. Universidad de Granada.

- Sanchez Farfan, Y. S. (2023). Aplicación del modelo credit scoring y regresión logística en la predicción del crédito, en una entidad financiera de la ciudad del Cusco 2022.

- Suquillo Llumiquinga, J. A. Credit scoring: aplicando técnicas de regresión logística y modelos aditivos generalizados para una cartera de crédito en una entidad financiera. (B.S. thesis), Quito, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Támara-Ayús, A. L.; Vargas-Ramírez, H.; Cuartas, J. J.; Chica-Arrieta, I. E. Regresión logística y redes neuronales como herramientas para realizar un modelo Scoring. Revista Lasallista de Investigación 2019, 16(1), 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, L.; Crook, J.; Edelman, D. Credit scoring and its applications; SIAM, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas Lara, D. O. Metodología para la obtención de un modelo de cobranza de créditos masivos. desarrollo y obtención de un modelo de scor. (Unpublished master’s thesis), Quito, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Yeh, I.-C.; Lien, C.-h. Credit Scoring Using Machine Learning Techniques: A Review and Open Research Issues. Mathematics 2023, 11(4), 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Train | Test | Validation |

|---|---|---|

| 87,821 | 37,638 | 18,819 |

| 61% | 26% | 13% |

| Dep.Var. | Arrears | Train | Test | Validation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G | B | G | B | G | B | ||

| Y1 | 0-no arrears | 75% | 25% | 75% | 25% | 75% | 25% |

| 1-30 | 68% | 32% | 68% | 32% | 67% | 33% | |

| 31-90 | 32% | 68% | 32% | 68% | 33% | 67% | |

| Y2 | All | 63% | 37% | 63% | 37% | 63% | 37% |

| 0 Segment Models | 1–30 Segment Model | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LR | XGB | ANN | LR | XGB | ANN | |

| 56.42% | 63.36% | 61.84% | 47.32% | 51.38% | 50.35% | |

| 31–90 Segment Model | All Arrears Model | |||||

| LR | XGB | ANN | LR | XGB | ANN | |

| 36.62% | 34.47% | 38.77% | 71.01% | 74.05% | 73.59% | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).