Submitted:

05 August 2025

Posted:

06 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Cultures and Treatments

2.2. PPARA Silencing

2.3. Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR)

2.4. Immunofluorescence

2.5. Western Blotting

2.6. Cell Proliferation Assay

2.7. Cell Viability Assay

2.8. Determination of Apoptosis by Flow Cytometer

2.9. Assessment of Hypertrophic Phenotype

2.10. Analysis of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS)

2.11. HPLC Determination of Reduced (GSH) and Oxidized Glutathione (GSSG)

2.12. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

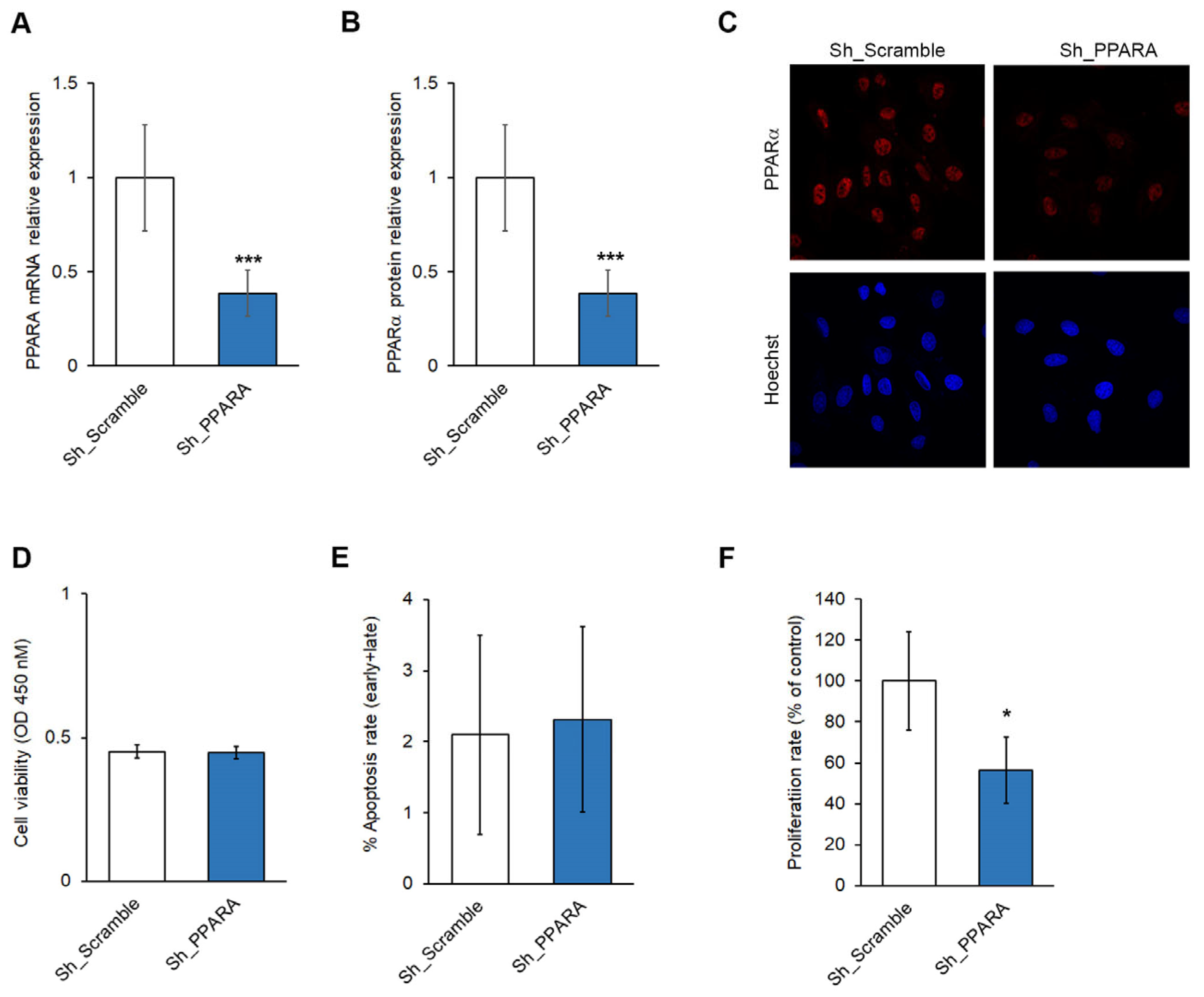

3.1. Effect of PPARA Silencing on Cell Viability and Apoptosis in Cardiomyoblasts

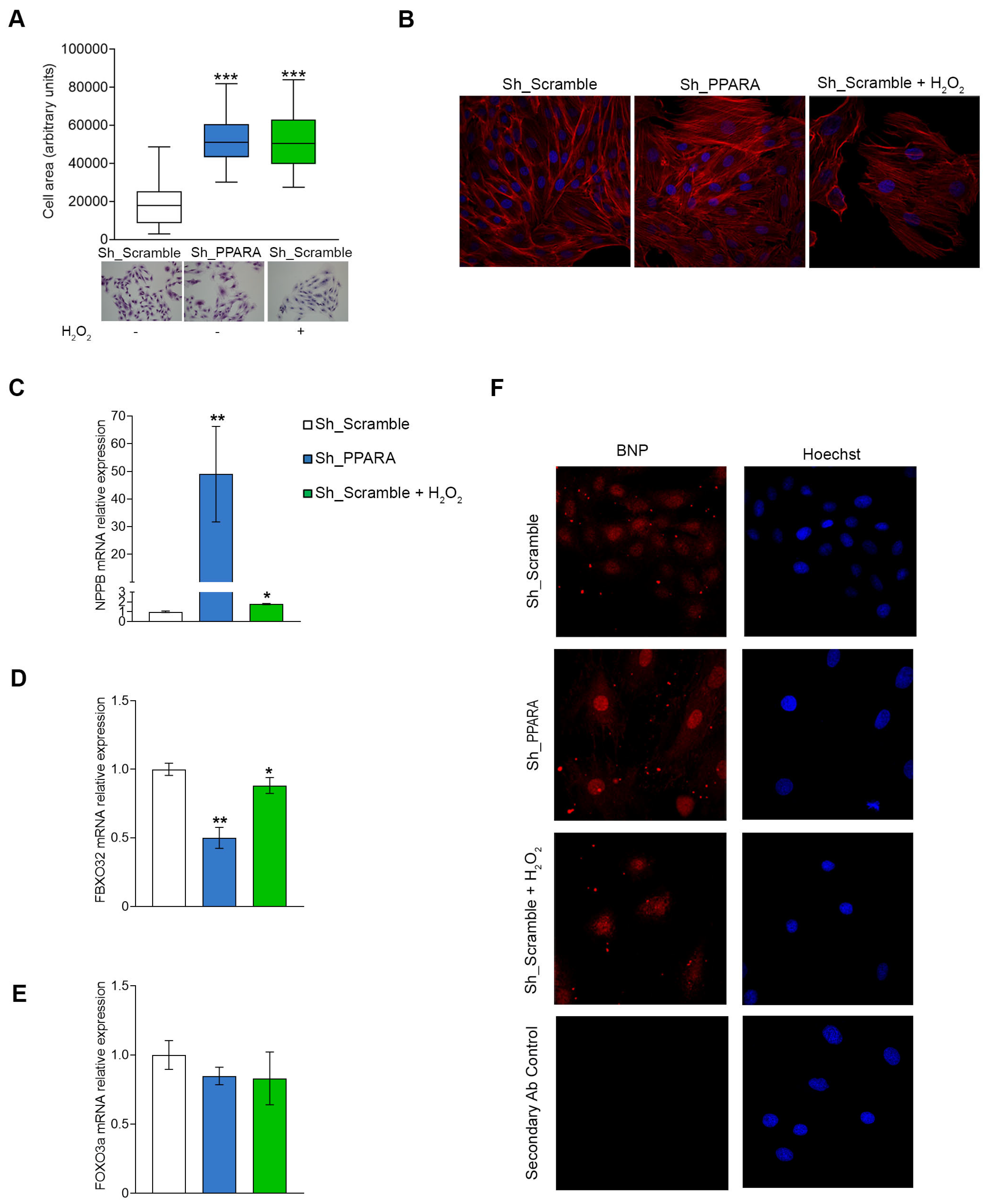

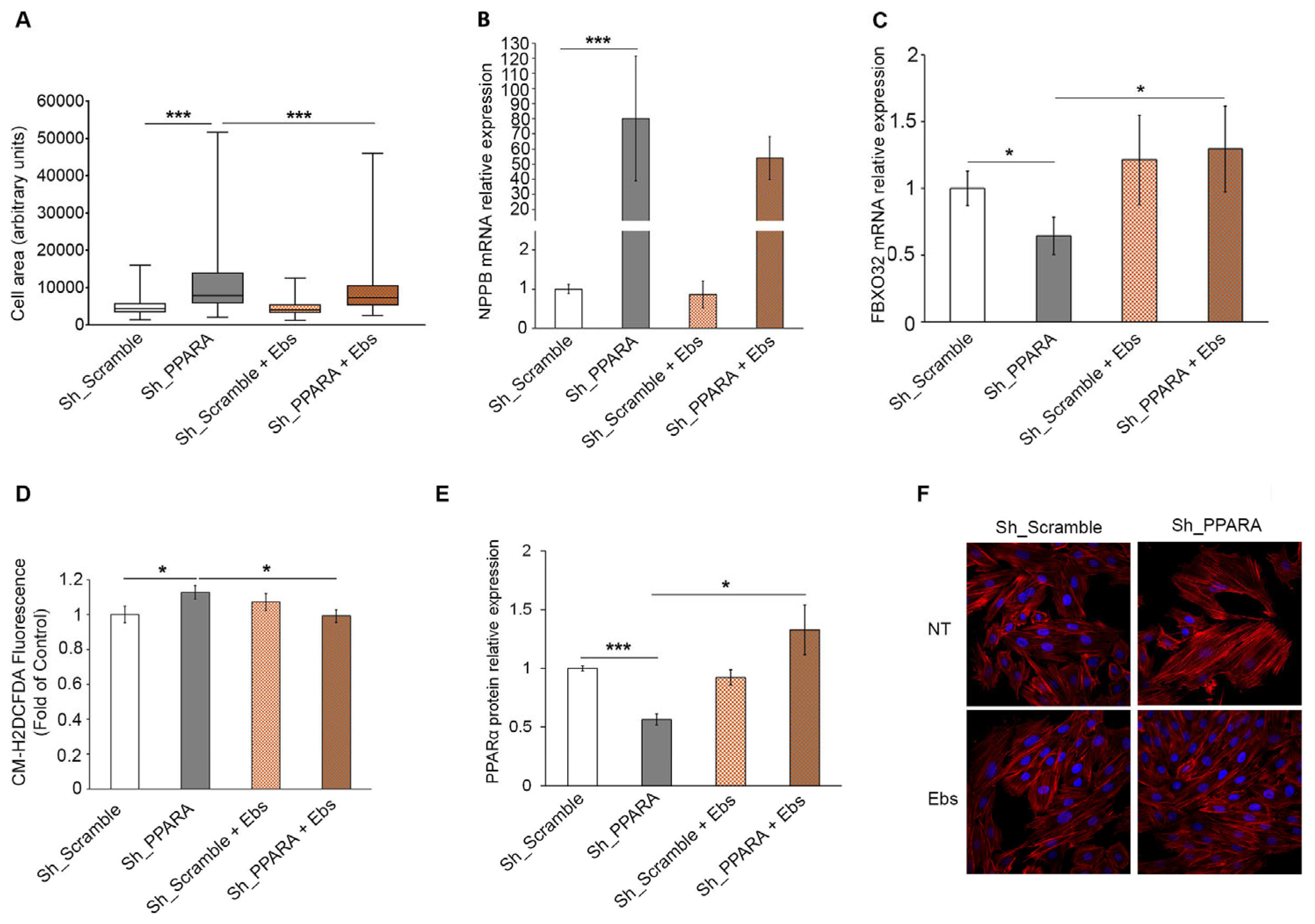

3.2. Effect of PPARA Silencing on Hypertrophic Phenotype in Cardiomyoblasts

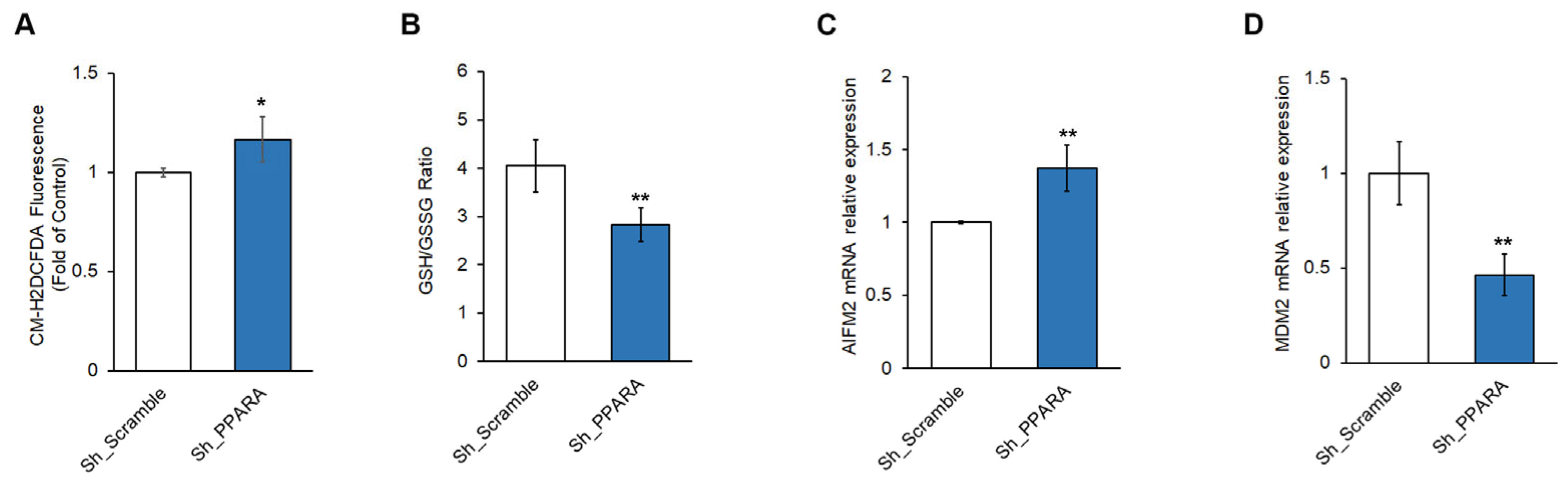

3.3. Effect of PPARA Silencing on Redox Metabolism and Ferroptosis in Cardiomyoblasts

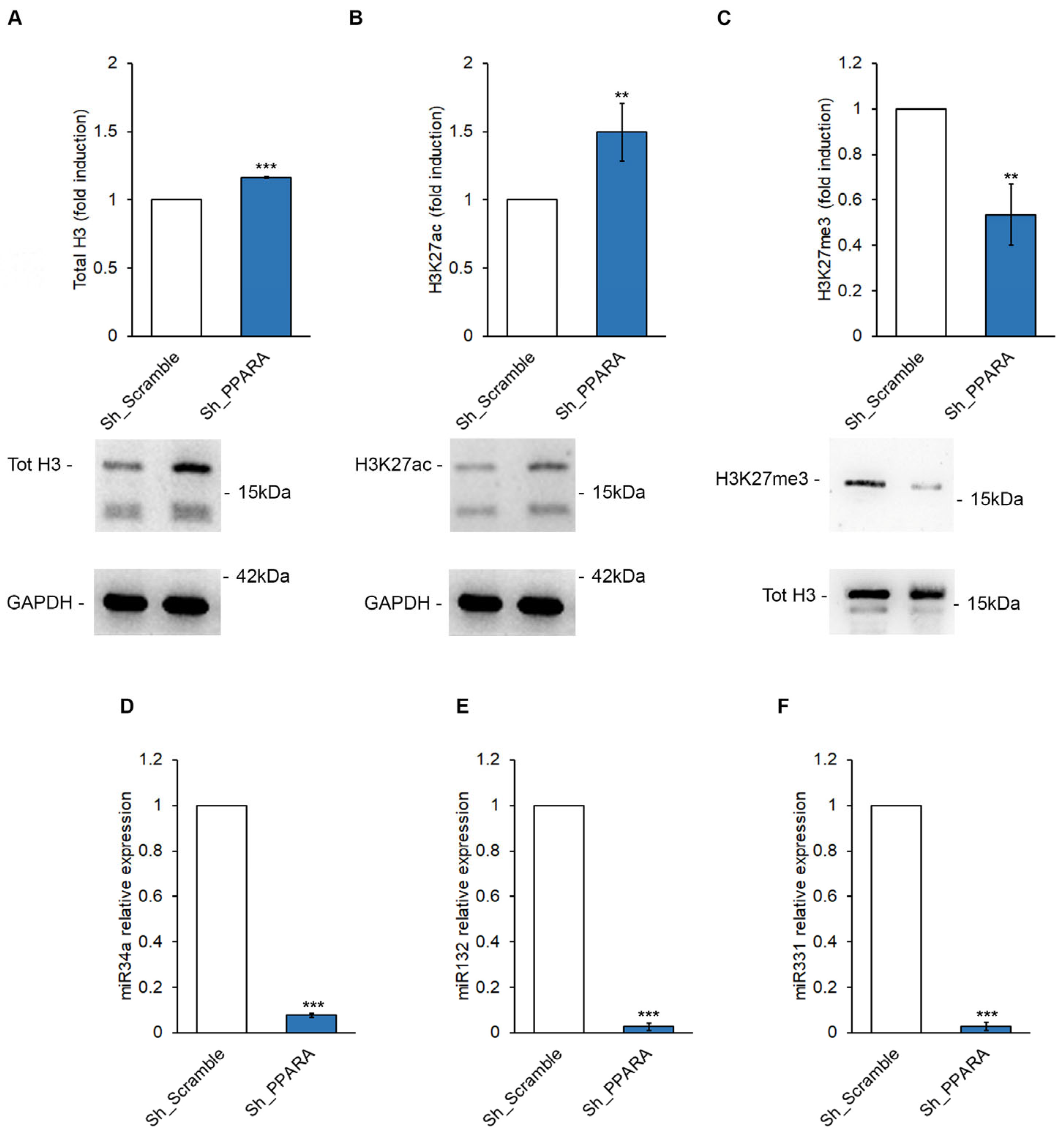

3.4. Effect of PPARA Silencing on Epigenetic Mechanisms Upstream of BNP Expression in Cardiomyoblasts

3.5. Assessment of Hypertrophic Phenotype and Oxidative Stress After Ebs Treatment in Hypertrophic Cardiomyoblasts

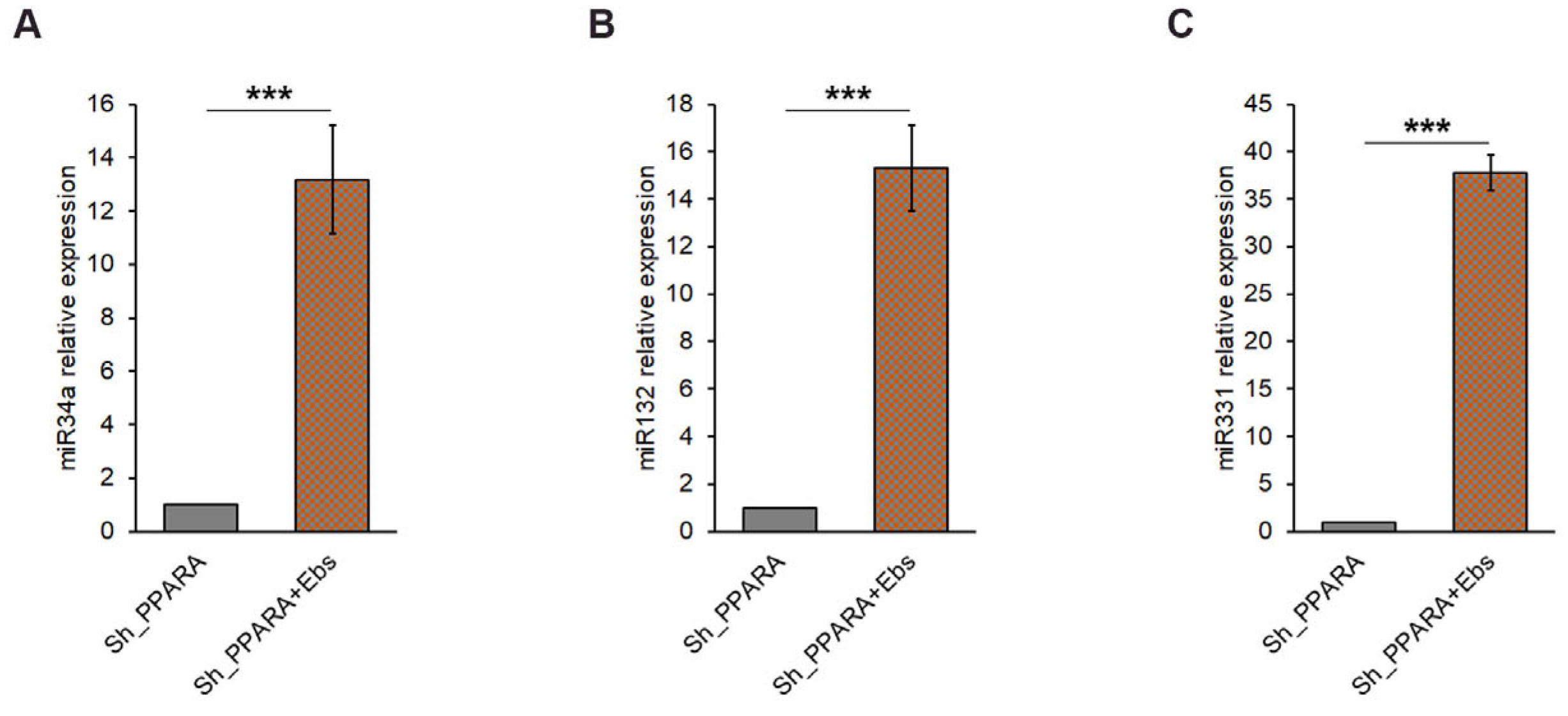

3.6. Assessment of Epigenetic Changes After Ebs Treatment in Hypertrophic Cardiomyoblasts

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 3’UTR | 3'-untranslated region |

| ACOX1 | Acyl-coenzyme A oxidase 1 gene |

| AIFM2 | AIF family member 2 |

| BNP | Protein B-type natriuretic peptide |

| CH | Cardiac hypertrophy |

| CM-H2DCFDA | 5-(6)-Chloromethyl-2',7'-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate, acetyl ester |

| Ebs | Ebselen |

| FBXO32 | Muscle Atrophy F-box gene |

| FOXO3 | Forkhead box O3 gene |

| GAPDH | Glyceraldehyde-3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase gene |

| GSH | Reduced glutathione |

| GSSG | Oxidized glutathione |

| H2O2 | Hydrogen peroxide |

| MDM2 | Mouse double minute 2 homolog |

| NFE2 | Nuclear factor erythroid 2 gene |

| NPPB | Brain Natriuretic Peptide B gene |

| PBS | Phosphate Buffered Saline |

| PPAR | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor family of lipid-activated nuclear receptors |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SYBR-green | 2-[N-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-N-propylamino]-4-[2,3-dihydro-3-methyl-(benzo-1,3-thiazol-2-yl)-methylidene]-1-phenyl-quinolinium |

References

- Nakamura, M.; Sadoshima, J. Mechanisms of physiological and pathological cardiac hypertrophy. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2018, 15, 387–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiattarella, G.G.; Hill, J.A. Inhibition of hypertrophy is a good therapeutic strategy in ventricular pressure overload. Circulation 2015, 131, 1435–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desvergne, B.; Wahli, W. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors: nuclear control of metabolism. Endocr. Rev. 1999, 20, 649–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barger, P.M.; Brandt, J.M.; Leone, T.C.; Weinheimer, C.J.; Kelly, D.P. Deactivation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha during cardiac hypertrophic growth. J. Clin. Invest. 2000, 105, 1723–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guellich, A.; Damy, T.; Lecarpentier, Y.; Conti, M.; Claes, V.; Samuel, J.L.; Quillard, J.; Hébert, J.L.; Pineau, T.; Coirault, C. Role of oxidative stress in cardiac dysfunction of PPARalpha-/- mice. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2007, 293, H93–H102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, K.; Fujii, H.; Takahashi, T.; Kodama, M.; Aizawa, Y.; Ohta, Y.; Ono, T.; Hasegawa, G.; Naito, M.; Nakajima, T.; et al. Constitutive regulation of cardiac fatty acid metabolism through peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha associated with age-dependent cardiac toxicity. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 22293–22299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, L.K.; Finck, B.N.; Kelly, D.P. Mouse models of mitochondrial dysfunction and heart failure. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2005, 38, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takano, H.; Nagai, T.; Asakawa, M.; Toyozaki, T.; Oka, T.; Komuro, I.; Saito, T.; Masuda, Y. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor activators inhibit lipopolysaccharide-induced tumor necrosis factor-alpha expression in neonatal rat cardiac myocytes. Circ. Res. 2000, 87, 596–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hescheler, J.; Meyer, R.; Plant, S.; Krautwurst, D.; Rosenthal, W.; Schultz, G. Morphological, biochemical, and electrophysiological characterization of a clonal cell (H9c2) line from rat heart. Circ. Res. 1991, 69, 1476–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldman, A.T.; Wolfe, D. Tissue processing and hematoxylin and eosin staining. Methods Mol. Biol. 2014, 1180, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panera, N.; Gnani, D.; Piermarini, E.; Petrini, S.; Bertini, E.; Nobili, V.; Pastore, A.; Piemonte, F.; Alisi, A. High concentrations of H2O2 trigger hypertrophic cascade and phosphatase and tensin homologue (PTEN) glutathionylation in H9c2 cardiomyocytes. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2016, 100, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, J.; Barnett, P.; Christoffels, V.M. Structure and function of the Nppa-Nppb cluster locus during heart development and disease. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2018, 75, 1435–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubattu, S.; Stanzione, R.; Cotugno, M.; Bianchi, F.; Marchitti, S.; Forte, M. Epigenetic control of natriuretic peptides: implications for health and disease. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2020, 24, 5121–5130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.Q.; Shehadeh, L.A.; Mitrani, J.M.; Pessanha, M.; Slepak, T.I.; Webster, K.A.; Bishopric, N.H. Quantitative control of adaptive cardiac hypertrophy by acetyltransferase p300. Circulation 2008, 118, 934–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, V.; Bell, G.W.; Nam, J.; Bartel, D.P. Predicting effective microRNA target sites in mammalian mRNAs. eLife 2015, 4, e05005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, B.C.; Gao, X.M.; Tham, Y.K.; Kiriazis, H.; Winbanks, C.E.; Ooi, J.Y.; Boey, E.J.; Obad, S.; Kauppinen, S.; Gregorevic, P.; et al. Silencing of miR-34a attenuates cardiac dysfunction in a setting of moderate, but not severe, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. PLoS One 2014, 9, e90337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.J.; Wang, L.P.; Li, R.C.; Wang, M.; Huang, Z.H.; Zhu, M.; Wang, J.X.; Wang, X.J.; Wang, S.Q.; Xu, M. Abnormal expression of miR-331 leads to impaired heart function. Sci. Bull. (Beijing) 2019, 14, 1011–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinkel, R.; Batkai, S.; Bähr, A. Bozoglu, T.; Straub, S.; Borchert, T.; Viereck, J.; Howe, A.; Hornaschewitz, N.; Oberberger, L.; et al. AntimiR-132 Attenuates Myocardial Hypertrophy in an Animal Model of Percutaneous Aortic Constriction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 23, 2923–2935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Wang, P.; Dong, C.; Zhao, Y.; Zhou, J.; Yuan, C.; Zou, L. Mechanisms of ebselen as a therapeutic and its pharmacology applications. Future Med. Chem. 2020, 23, 2141–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barchielli, G.; Capperucci, A.; Tanini, D. The Role of Selenium in Pathologies: An Updated Review. Antioxidants 2022, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, P.F. PPARα: An emerging target of metabolic syndrome, neurodegenerative and cardiovascular diseases. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 2022, 13, 1074911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fillmore, N.; Mori, J.; Lopaschuk, G.D. Mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation alterations in heart failure, ischaemic heart disease and diabetic cardiomyopathy. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2014, 171, 2080–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Fang, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, D.; Wu, L.; Wang, Y. PPARα Ameliorates Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity by Reducing Mitochondria-Dependent Apoptosis via Regulating MEOX1. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 528267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarra-Lara, L.; Hong, E.; Soria-Castro, E.; Torres-Narváez, J.C.; Pérez-Severiano, F.; Del Valle-Mondragón, L.; Cervantes-Pérez, L.G.; Ramírez-Ortega, M.; Pastelín-Hernández, G.S.; Sánchez-Mendoza, A. Clofibrate PPARα activation reduces oxidative stress and improves ultrastructure and ventricular hemodynamics in no-flow myocardial ischemia. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2012, 60, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, M.S.; Ambrose, L.; Ball, V.; Clarke, K.; Carr, C.A.; Tyler, D.J. The age-dependent development of abnormal cardiac metabolism in the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α-knockout mouse. Atherosclerosis 2024, 399, 118599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.H.; Willis, M.S.; Lockyer, P.; Miller, N.; McDonough, H.; Glass, D.J.; Patterson, C. Atrogin-1 inhibits Akt-dependent cardiac hypertrophy in mice via ubiquitin-dependent coactivation of Forkhead proteins. J. Clin. Invest. 2007, 117, 3211–3223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, K.N. Molecular Signaling Mechanisms and Function of Natriuretic Peptide Receptor-A in the Pathophysiology of Cardiovascular Homeostasis. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 693099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.H.; Kedar, V.; Zhang, C.; McDonough, H.; Arya, R.; Wang, D.Z.; Patterson, C. Atrogin-1/muscle atrophy F-box inhibits calcineurin-dependent cardiac hypertrophy by participating in an SCF ubiquitin ligase complex. J. Clin. Invest. 2004, 114, 1058–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pruimboom-Brees, I.; Haghpassand, M.; Royer, L.; Brees, D.; Aldinger, C.; Reagan, W.; Singh, J.; Kerlin, R.; Kane, C.; Bagley, S.; et al. A critical role for peroxisomal proliferator-activated receptor-alpha nuclear receptors in the development of cardiomyocyte degeneration and necrosis. Am. J. Pathol. 2006, 169, 750–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smeets, P.J.; Teunissen, B.E.; Willemsen, P.H.; van Nieuwenhoven, F.A.; Brouns, A.E.; Janssen, B.J.; Cleutjens, J.P.; Staels, B.; van der Vusse, G.J.; van Bilsen, M. Cardiac hypertrophy is enhanced in PPAR alpha-/- mice in response to chronic pressure overload. Cardiovasc. Res. 2008, 78, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elia, A.; Mohsin, S.; Khan, M. Cardiomyocyte Ploidy, Metabolic Reprogramming and Heart Repair. Cells 2023, 12, 1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, Y.S.; Oh, H.; Rhee, S.G.; Yoo, Y.D. Regulation of reactive oxygen species generation in cell signaling. Mol. Cells 2011, 32, 491–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giustarini, D.; Colombo, G.; Garavaglia, M.L.; Astori, E.; Portinaro, N.M.; Reggiani, F.; Badalamenti, S.; Aloisi, A.M.; Santucci, A.; Rossi, R.; et al. Assessment of glutathione/glutathione disulphide ratio and S-glutathionylated proteins in human blood, solid tissues, and cultured cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2017, 112, 360–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadian, K.; Stockwell, B.R. SnapShot: Ferroptosis. Cell 2020, 181, 1188–1188.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo,Y. ; Lu, C.; Hu, K.; Cai, C.; Wang, W. Ferroptosis in Cardiovascular Diseases: Current Status, Challenges, and Future Perspectives. Biomolecules 2022, 3, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauck, L.; Stanley-Hasnain, S.; Fung, A.; Grothe, D.; Rao, V.; Mak, T.W.; Billia, F. Cardiac-specific ablation of the E3 ubiquitin ligase Mdm2 leads to oxidative stress, broad mitochondrial deficiency and early death. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0189861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, G.; Meng, L.; Cao, S.; Liu, S.; Wu, J.; Li, Q.; Huang, W.; Zhang, L. PPARα alleviates iron overload-induced ferroptosis in mouse liver. EMBO Rep. 2022, 23, e52280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papait, R.; Cattaneo, P.; Kunderfranco, P.; Greco, C.; Carullo, P.; Guffanti, A.; Viganò, V.; Stirparo, G.G.; Latronico, M.V.; Hasenfuss, G.; et al. Genome-wide analysis of histone marks identifying an epigenetic signature of promoters and enhancers underlying cardiac hypertrophy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 20164–20169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernardo, B.C.; Yildiz, G.S.; Kiriazis, H.; Harmawan, C.A.; Tai, C.M.K.; Ritchie, R.H.; McMullen, J.R. In Vivo Inhibition of miR-34a Modestly Limits Cardiac Enlargement and Fibrosis in a Mouse Model with Established Type 1 Diabetes-Induced Cardiomyopathy, but Does Not Improve Diastolic Function. Cells 2022, 19, 3117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabłak-Ziembicka, A.; Badacz, R.; Okarski, M.; Wawak, M.; Przewłocki, T.; Podolec, J. Cardiac microRNAs: diagnostic and therapeutic potential. Arch. Med. Sci. 2023, 5, 1360–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wallach, J.; Duane, S.; Wang, Y.; Wu, J.; Wang, J.; Adejare, A.; Ma, H. Developing selective histone deacetylases (HDACs) inhibitors through ebselen and analogs. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2017, 11, 1369–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, W.; Qiao, X.; Fang, Y.; Guo, R.; Bai, P.; Liu, S.; Li, T.; Jiang, Y.; Wei, S.; Na, Z.; et al. Epigenetics-targeted drugs: current paradigms and future challenges. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 2024, 1, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).