Submitted:

04 August 2025

Posted:

05 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. General

2.2. NMR Spectra

2.2.1. 1-Ethyl-3-Methylimidazolium Bromide

2.2.2. 1-Butyl-3-Methylimidazolium Bromide

2.2.3. 1-Hexyl-3-Methylimidazolium Bromide

2.2.4. 1-Methyl-3-Octylimidazolium Bromide

2.2.5. 1-Decyl-3-Methylimidazolium Bromide

2.2.6. 1-Benzyl-3-Methylimidazolium Bromide

2.2.7. 1-Methyl-3-(2-Phenylethyl)-Imidazolium Bromide

2.2.8. 1-Methyl-3-(3-Phenylpropyl)-Imidazolium Bromide

2.2.9. 1-(Cyclohexylmethyl)-3-Methylimidazolium Bromide

2.2.10. 1-(2-Cyclohexylethyl)-3-Methylimidazolium Bromide

2.1.11. 1-Allyl-3-Methylimidazolium Bromide

2.1.12. 1-Isobutyl-3-Methyl-Imidazolium Bromide

2.1.13. 1-Isopentyl-3-Methyl-Imidazolium Bromide

2.1.14. 1-(3-Hydroxypropyl)-3-Methyl-Imidazolium Bromide

2.1.15. 1-(3-Cyanopropyl)-3-Methyl-Imidazolium Bromide

2.1.16. 1-(Methoxymethyl)-3-Methylimidazolium Bromide

2.1.17. 1-(2-Methoxy-2-Oxoethyl)-3-Methylimidazolium Bromide

2.1.18. 1-(3-Methoxy-3-Oxopropyl)-3-Methylimidazolium Bromide

2.1.19 1-(Sec-Butyl)-3-Methylimidazolium Bromide

2.1.20. N-Methylimidazole Hydrobromide

2.1.21. 1-Butyl-3-Methylimidazolium Chloride

2.2.22. 1-Hexyl-3-Methylimidazolium Chloride

2.2.23. 1-Methyl-3-Octylimidazolium Chloride

2.2.24. 1-Decyl-3-Methylimidazolium Chloride

2.3. In Vitro Studies

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shamshina; J.; Zavgorodnya; O.; Rogers, R. Ionic Liquids. In Encyclopedia of Analytical Science, 3rd ed.; Reedijk, J. Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2019; 218–225.

- Bogdanov; M. ; Kantlehner, W. Simple Prediction of Some Physical Properties of Ionic Liquids: The Residual Volume Approach. Z. Naturforsch. B 2009, 64, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanov; M. ; Iliev; B.; Kantlehner, W. The Residual Volume Approach II: Simple Prediction of Ionic Conductivity of Ionic Liquids. Z. Naturforsch. B 2009, 64, 756–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippi; F. ; Welton, T. Targeted modifications in ionic liquids—from understanding to design. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2021, 23, 6993–7021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andresová; A.; Bendová; M.; Schwarz; J.; Wagner; Z.; Feder-Kubis, J. Influence of the alkyl side chain length on the thermophysical properties of chiral ionic liquids with a (1R, 2S, 5R)-(−)-menthol substituent and data analysis by means of mathematical gnostics. J. Mol. Liq. 2017, 242, 336–348.

- Passos; H. ; Freire; M.; Coutinhoa, J. Ionic liquid solutions as extractive solvents for value-added compounds from biomass. Green Chem. 2014, 16, 4786–4815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. ; Ma; W.; Hu; R.; Dai; X.; Pan, Y. Ionic liquid-based microwave-assisted extraction of phenolic alkaloids from the medicinal plant Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn. J. Chromatogr. A 2008, 1208, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu; T. ; Sui; X.; Zhang; R.; Yang; L.; Zu; Y.; Zhang; L.; Zhang; Y.; Zhang, Z. Application of ionic liquids based microwave-assisted simultaneous extraction of carnosic acid, rosmarinic acid and essential oil from Rosmarinus officinalis. J. Chromatogr. A 2011, 1218, 8480–8489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang; P. ; Wang; R.; Matulis, V. Ionic Liquids as Green and Efficient Desulfurization Media Aiming at Clean Fuel. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogdanov, M. Ionic Liquids as Alternative Solvents for Extraction of Natural Products. In: Alternative Solvents for Natural Products. In Alternative Solvents for Natural Products Extraction. Chemat, F., Vian, M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 127–166. [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanov; M. ; Svinyarov; I.; Keremedchieva; R.; Sidjimov, A. Ionic liquid-supported solid-liquid extraction of bioactive alkaloids. I. New HPLC method for quantitative determination of glaucine in Glaucium flavum Cr. (Papaveraceae). Sep. Purif. Technol. 2012, 97, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonova; K. ; Svinyarov; I.; Bogdanov, M. Hydrophobic 3-alkyl-1-methylimidazolium saccharinates as extractants for L-lactic acid recovery. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2014, 125, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreuter; J. ; Bica-Schröder; K.; Pálvölgyi; Á.; Krska; R.; Sommer; R.; Farnleitner; A.; Kolm; Reischer, G. A novel ionic liquid-based approach for DNA and RNA extraction simplifies sample preparation for bacterial diagnostics. Anal. bioanal. chem. 2024, 416, 7109–7120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sprakel; L. ; Schuur, B. Solvent developments for liquid-liquid extraction of carboxylic acids in perspective. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2019, 211, 935–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira; J. ; Lima, Á.; Freire; M.; Coutinho, J. Ionic liquids as adjuvants for the tailored extraction of biomolecules in aqueous biphasic systems. Green Chem., 2010, 12, 1661–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura; S. ; Silva; F.; Quental; M.; Mondal; D.; Freire; M; Coutinho, J. Ionic-Liquid-Mediated Extraction and Separation Processes for Bioactive Compounds: Past, Present, and Future Trends. Chem. Rev., 2017, 117, 6984–7052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire; M; Neves; C. ; Marrucho; I.; Lopes; J.; Rebelo; L.; Coutinho, J. High-performance extraction of alkaloids using aqueous two-phase systems with ionic liquids. Green Chem., 2010, 12, 1715–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoh, T. Ionic Liquids as Tool to Improve Enzymatic Organic Synthesis. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 10567–10607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imam; H. T.; Krasňan; V.; Rebroš; M.; Marr, A. Applications of Ionic Liquids in Whole-Cell and Isolated Enzyme Biocatalysis. Molecules 2021, 26, 4791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welton, T. Room-Temperature Ionic Liquids. Solvents for Synthesis and Catalysis. Chem. rev., 1999, 99, 2071–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisele; Bica-Schröder; K. (2025). Photocatalytic Carbon Dioxide Reduction with Imidazolium-Based Ionic Liquids. ChemSusChem. 2025, 18, e202402626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stalpaert; M. ; Janssens; K.; Marquez; C.; Henrion; M.; Bugaev; A.; Soldatov; A.; De Vos, D. Olefins from Biobased Sugar Alcohols via Selective, Ru-Mediated Reaction in Catalytic Phosphonium Ionic Liquids. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 9401–9409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao; Y. ; Dong; R.; Pavlidis; I.; Chen; B.; Tan, T. Using imidazolium-based ionic liquids as dual solvent-catalysts for sustainable synthesis of vitamin esters: inspiration from bio- and organo-catalysis. Green Chem. 2016, 18, 1240–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang; J. ; Zhao; X.; Wang, W. Acidic ionic liquid grafted PPF membrane reactor and its catalytic esterification kinetics. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 400, 125319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukawka; R. ; Pawlowska-Zygarowicz; A.; Dzialkowska; J.; Pietrowski; M.; Maciejewski; H.; Bica; K.; Smiglak, M. Highly Effective Supported Ionic Liquid-Phase (SILP) Catalysts: Characterization and Application to the Hydrosilylation Reaction. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 4699–4706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray; A. ; Saruhan, B. Application of Ionic Liquids for Batteries and Supercapacitors. Materials 2021, 14, 2942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagliero; C. & Bicchi, C. Ionic liquids as gas chromatographic stationary phases: how can they change food and natural product analyses? Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2020, 412, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christoff-Tempesta; T. & Epps II, T. Ionic-Liquid-Mediated Deconstruction of Polymers for Advanced Recycling and Upcycling. ACS Macro Lett. 2023, 12, 1058–1070. [Google Scholar]

- Kamimura; A. ; Kawamoto; T.; Fujii, K. Ionic Liquids for the Chemical Recycling of Polymeric Materials and Control of Their Solubility. Chem. Rec. 2023, 23, e202200269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes; J. ; Silva; S.; Reis, R. Biocompatible ionic liquids: fundamental behaviours and applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48, 4317–4335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egorova; K. ; Gordeev; E.; Ananikov, V. Biological Activity of Ionic Liquids and Their Application in Pharmaceutics and Medicine. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 7132–7189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamshina; J. & Rogers, R. Ionic Liquids: New Forms of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients with Unique, Tunable Properties. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 11894–11953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedro; S. ; Freire; C.; Silvestre; A.; Freire, M. The Role of Ionic Liquids in the Pharmaceutical Field: An Overview of Relevant Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci., 2020, 21, 8298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh; O. ; Kaur; R.; Aswal; V.; Mahajan, R. Composition and Concentration Gradient Induced Structural Transition from Micelles to Vesicles in the Mixed System of Ionic Liquid-Diclofenac Sodium. Langmuir. 2016, 32, 6638–6647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viau; L. ; Tourne-Peteilh; C.; Devoisselle; J.; Vioux, A. Ionogels as drug delivery system: One-step sol-gel synthesis using imidazolium ibuprofenate ionic liquid. Chem. comm. 2010, 46, 228–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaitely; V. ; Karatas; A.; Florence, A. Water-immiscible room temperature ionic liquids (RTILs) as drug reservoirs for controlled release. Int. J. Pharm. 2008, 354, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoh; T. ; Takagi, Y. Activation and stabilization of enzymes using ionic liquid engineering, in Biocatalysis in Green Solvents, Lozano, P., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, USA, 2022; pp. 57–83. [Google Scholar]

- Lou; W. ; Zong, M. Efficient kinetic resolution of (R,S)-1-trimethylsilylethanol via lipase-mediated enantioselective acylation in ionic liquids. Chirality 2006, 18, 814–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Persson; M. ; Bornscheuer, U. Increased stability of an esterase from Bacillus stearothermophilus in ionic liquids as compared to organic solvents. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 2003, 22, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarver; C. ; Yuan; Q.; Pusey, M. Ionic Liquids as Protein Crystallization Additives. Crystals 2021, 11, 1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuroda, K. A simple overview of toxicity of ionic liquids and designs of biocompatible ionic liquids. New J. Chem. 2022, 46, 20047–20052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves; A. ; Paredes; X.; Cristino; A.; Santos; F; Queirós, C. Ionic Liquids—A Review of Their Toxicity to Living Organisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee; S. ; Chang; W.; Choi; A.; Koo, Y. Influence of ionic liquids on the growth of Escherichia coli. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2005, 22, 687–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petkovic; M. ; Ferguson; J.; Bohn; A.; Trindade; J.; Martins; I.; Carvalho; M.; Leitão; M.; Rodrigues; C.; Garcia; H.; Ferreira; R.; Seddon; K.; Rebelo; L.; Pereira, C. Exploring fungal activity in the presence of ionic liquids. Green Chem. 2009, 11, 889–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biczak; R. ; Bałczewski; P.; Pawłowska; B.; Bachowska; B.; Rychter, P. Comparison of Phytotoxicity of Selected Phosphonium Ionic Liquid. Ecol. Chem. Eng. S 2014, 21, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura; S. ; Gonçalves; A.; Sintra; T.; Pereira; J.; Gonçalves; F.; Coutinho, J. Designing ionic liquids: the chemical structure role in the toxicity. Ecotoxicol. 2013, 22, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, A. Toxicity and Biodegradability of Solvents: A Comparative Analysis. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Mellado; N. ; Ayuso; M.; Villar-Chavero; M.; Garcia; J.; Rodriguez, F. Ecotoxicity evaluation towards Vibrio fischeri of imidazolium- and pyridinium-based ionic liquids for their use in separation processes. SN Appl. Sci. 2019, 1, 896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

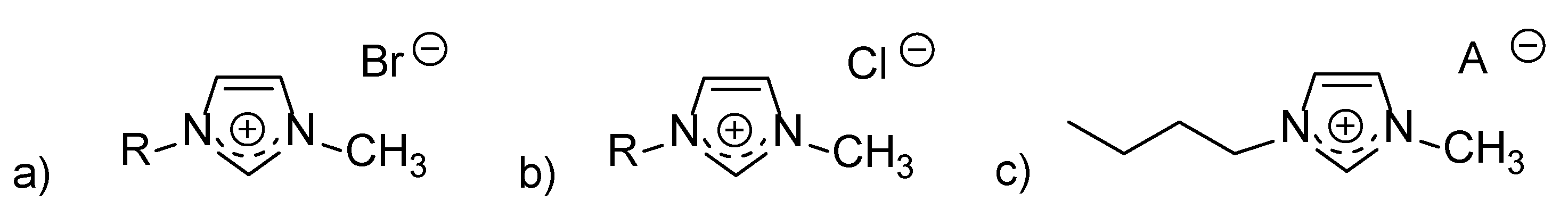

- Stolte; S. ; Matzke; M.; Arning; J.; Böschen; A.; Pitner; W.; Welz-Biermann; U.; Jastorff; B.; Ranke, J. Effects of different head groups and functionalised side chains on the aquatic toxicity of ionic liquids. Green Chem., 2007, 9, 1170–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao; D. ; Yongcheng; L.; Zhang, Z. Toxicity of Ionic Liquids. CLEAN—Soil, Air, Water. 2007, 35, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraiva; M.; Costa; S.; Pinto; P.; Azevedo, A. Environmental impact of ionic liquids: an overview of recent (eco)toxicological and (bio)degradability literature. ChemSusChem. 2017, 10 2321–2347.

- Stock; F. ; Hoffmann; J.; Ranke; J.; Störmann; R.; Ondruschka; B.; Jastorff, B. Effects of ionic liquids on the acetylcholinesterase—a structure–activity relationship consideration. Green Chem. 2004, 6, 286–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan; Y. ; Dong; X.; Yan; L.; Li; D.; Hua; S.; Hu; C.; Pan, C. Evaluation of the toxicity of ionic liquids on trypsin: A mechanism study. Chemosphere 2016, 148, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan; Y. ; Dong; X.; Li; X.; Zhong; Y.; Kong; J.; Hua; S.; Miao; J.; Li, Y. Spectroscopic studies on the inhibitory effects of ionic liquids on lipase activity. Spectrochim. acta. Part A, Mol. Biomol. spectrosc., 2016, 159, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann; D. ; Shimizu; K.; Siopa; F.; Leitão; M.; Afonso; C.; Lopes; J.; Pereira, S. Plasma membrane permeabilisation by ionic liquids: a matter of charge. Green Chem. 2015, 17, 4587–4598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar; V. ; Malhotra, S. Study on the potential anti-cancer activity of phosphonium and ammonium-based ionic liquids. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009, 19, 4643–4646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

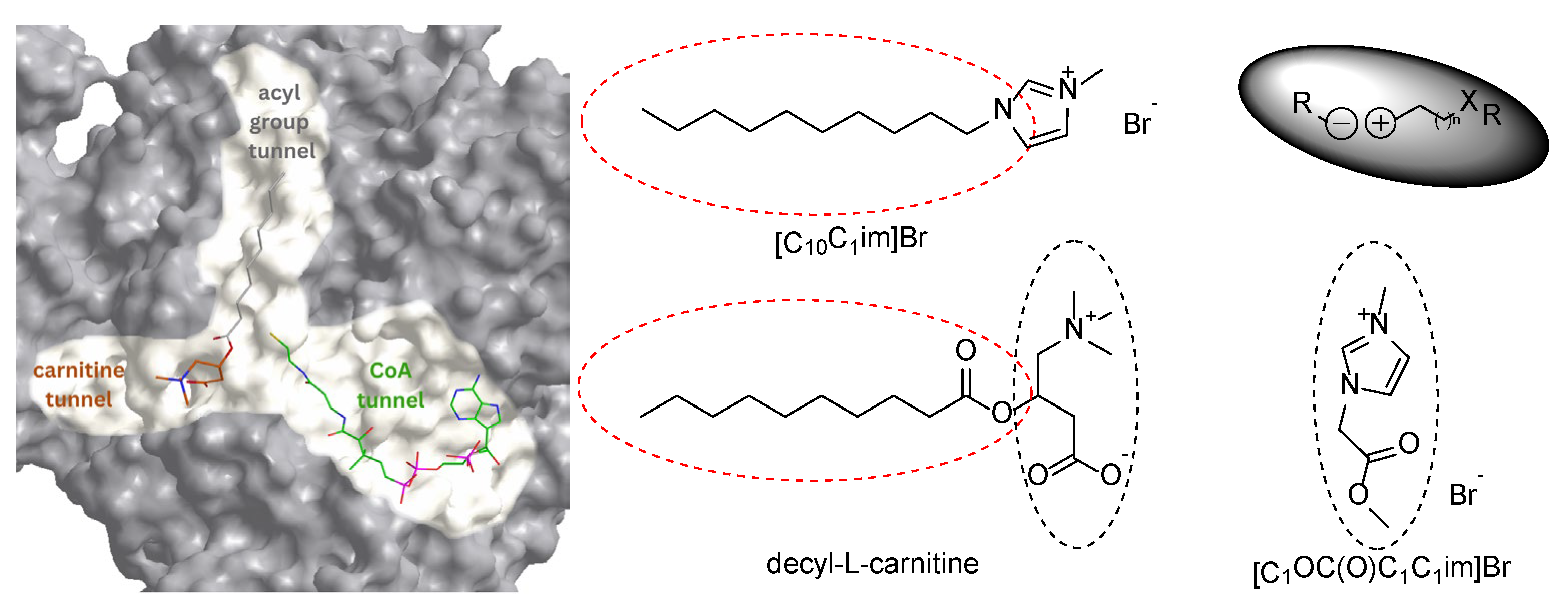

- Volpicella, M.; Sgobba, M.; Laera, L.; Francavilla, A.; De Luca, D.; Guerra, L.; Pierri, C.; De Grassi, A. Carnitine O-Acetyltransferase as a Central Player in Lipid and Branched-Chain Amino Acid Metabolism, Epigenetics, Cell Plasticity, and Organelle Function. Biomol. 2025, 15, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, I.; Yue, K. Long-chain carnitine acyltransferase and the role of acylcarnitine derivatives in the catalytic increase of fatty acid oxidation induced by carnitine. J. Lipid Res. 1963, 4, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsay, R.; Arduini, A. The carnitine acyltransferases and their role in modulating acyl-CoA pools. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1993, 302, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindasamy, L.; Kukar, T.; Lian, W.; Pedersen, B.; Gu, Y.; Agbandje-McKenna, M.; Jin, S.; McKenna, R.; Wu, D. Structural and mutational characterization of L-carnitine binding to human carnitine acetyltransferase. J. Struct. Biol. 2004, 146, 416–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jogl, G.; Tong, L. Crystal structure of carnitine acetyltransferase and implications for the catalytic mechanism and fatty acid transport. Cell 2003, 112, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Govindasamy, L.; Lian, W.; Gu, Y.; Kukar, T.; Agbandje-McKenna, M.; McKenna, R. Structure of human carnitine acetyltransferase. Molecular basis for fatty acyl transfer. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 13159–13165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramsay, R.; Gandour, R.; van der Leij, F. Molecular enzymology of carnitine transfer and transport. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2001, 1546, 21–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogdanov, M.G.; Petkova, D.; Hristeva, D.; Svinyarov, I.; Kantlehner, W. New guanidinium-based room-temperature ionic liquids. Substituent and anion effect on density and solubility in water. Z. Naturforsch. B 2010, 65, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanov, M.G.; Svinyarov, I. Distribution of N-Methylimidazole in Ionic Liquids/Organic Solvents Systems. Processes 2017, 5, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanov, M.G.; Svinyarov, I. Efficient purification of halide-based ionic liquids by means of improved apparatus for continuous liquid-liquid extraction. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2018, 196, 57–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquis, N.; Fritz, I. Enzymological determination of free carnitine concentrations in rat tissues. J. Lipid. Res. 1964, 5, 184–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baici, A. Kinetics of Enzyme-Modifier Interactions; Vienna Springer: Vienna, Austria, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jaudzems, K.; Kuka, J.; Gutsaits, A.; Zinovjevs, K.; Kalvinsh, I.; Liepinsh, E.; Liepinsh, E.; Dambrova, M. Inhibition of carnitine acetyltransferase by mildronate, a regulator of energy metabolism. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem., 2009, 24, 1269–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoyanova, S.; Bogdanov, M. G. Rational Design, Synthesis, and In Vitro Activity of Heterocyclic Gamma-Butyrobetaines as Potential Carnitine Acetyltransferase Inhibitors. Molecules 2025, 30, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoyanova, S.; Bogdanov, M. G. Rational Design, Synthesis and In Vitro Activity of Diastereomeric cis-/trans-3-substituted-3,4-dihydroisocoumarin-4-carboxylic Acids as Potential Carnitine Acetyltransferase Inhibitors. Molecules, 2025, 30, 3159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, K.; Kudo, Y.; Takeda, Y.; Katsuta, S. Partition of Substituted Benzenes between Hydrophobic Ionic Liquids and Water: Evaluation of Interactions between Substituents and Ionic Liquids. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2011, 56, 2160–2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohajeri, A.; Ashrafi, A. Structure and Electronic Properties of Amino Acid Ionic Liquids. J. Phys. Chem. A 2011, 115, 6589–6593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacace, M.; Landau, E.; Ramsden, J. ; The Hofmeister series: salt and solvent effects on interfacial phenomena. Q. rev. biophys. 1997, 30, 241–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. & Cremer, P. Interactions between macromolecules and ions: The Hofmeister series. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2006, 10, 658–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, K.; Elliott, G.; Robertson, H.; Kumar, A.; Wanless, E.; Webber, G.; Craig, V.; Andersson, G.; Page, A. Mitochondrial and metabolic alterations in cancer cells. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2022, 101, 151225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzini, V.; Craig, V. What is the fundamental ion-specific series for anions and cations? Ion specificity in standard partial molar volumes of electrolytes and electrostriction in water and non-aqueous solvents. Chem. Sci. 2017, 10, 3430–3433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Fernández, F.; Ríos, A.; Tomás-Alonso, F.; Gómez, D.; Víllora, G. Stability of hydrolase enzymes in ionic liquids. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 2009, 87, 910–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, A.; Zultanski, S.; Waldman, J.; Zhong, Y.; Shevlin, M.; Peng, F. General Principles and Strategies for Salting-Out Informed by the Hofmeister Series. Org. Process. Res. Dev. 2017, 21, 1355–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

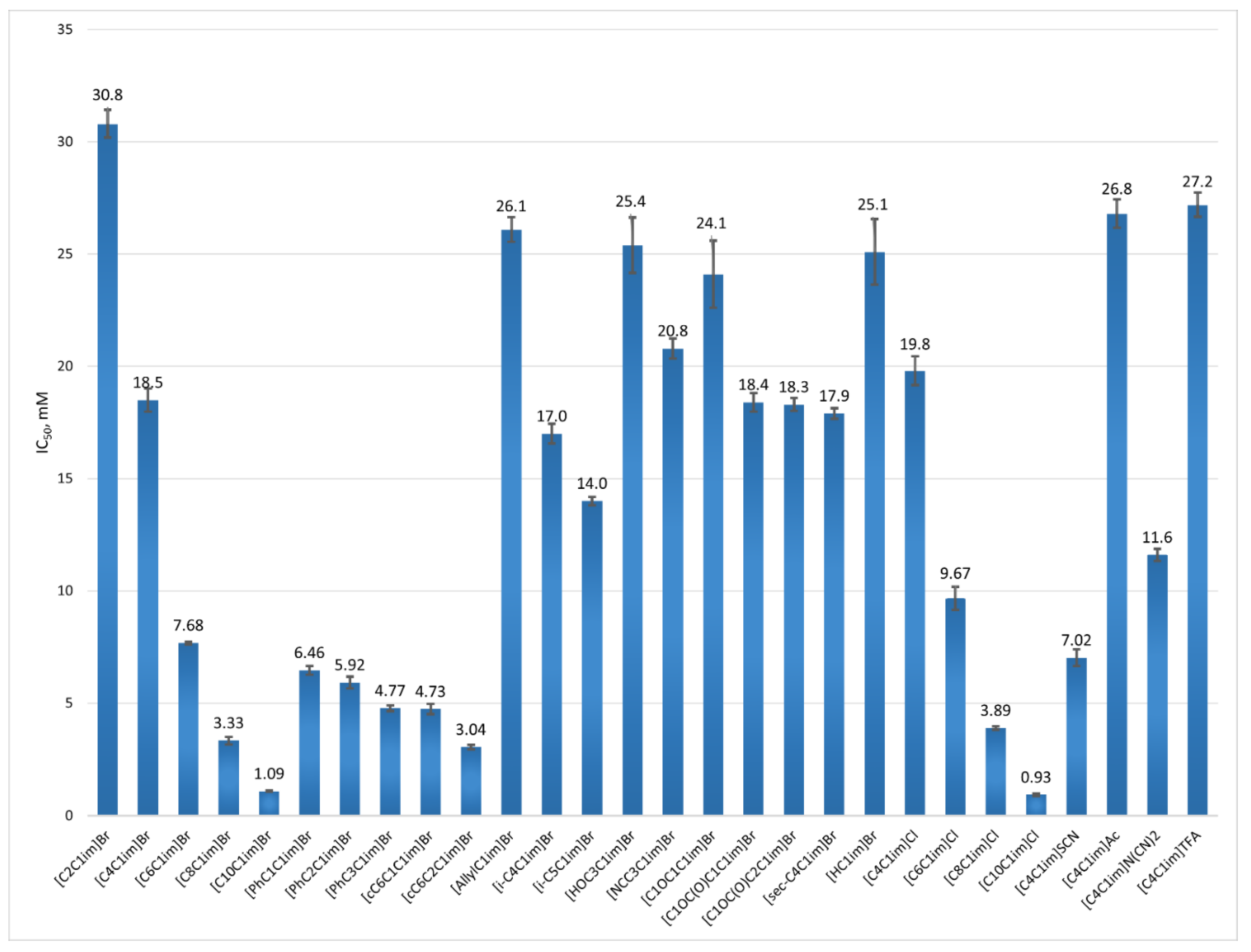

| Abbreviation | Name | IC50, mM |

|---|---|---|

| [C2C1im]Br | 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium bromide | 30.8 ± 0.62 |

| [C4C1im]Br | 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium bromide | 18.5 ± 0.51 |

| [C6C1im]Br | 1-hexyl-3-methylimidazolium bromide | 7.68 ± 0.06 |

| [C8C1im]Br | 1-methyl-3-octylimidazolium bromide | 3.33 ± 0.17 |

| [C10C1im]Br | 1-decyl-3-methylimidazolium bromide | 1.09 ± 0.02 |

| [PhC1C1im]Br | 1-benzyl-3-methylimidazolium bromide | 6.46 ± 0.20 |

| [PhC2C1im]Br | 1-methyl-3-(2-phenylethyl)-imidazolium bromide | 5.92 ± 0.26 |

| [PhC3C1im]Br | 1-methyl-3-(3-phenylpropyl)-imidazolium bromide | 4.77 ± 0.13 |

| [cC6C1C1im]Br | 1-(cyclohexylmethyl)-3-methylimidazolium bromide | 4.73 ± 0.23 |

| [cC6C2C1im]Br | 1-(2-cyclohexylethyl)-3-methylimidazolium bromide | 3.04 ± 0.10 |

| [AllylC1im]Br | 1-allyl-3-methylimidazolium bromide | 26.1 ± 0.55 |

| [i-C4C1im]Br | 1-isobutyl-3-methyl-imidazolium bromide | 17.0 ± 0.44 |

| [i-C5C1im]Br | 1-isopentyl-3-methyl-imidazolium bromide | 14.0 ± 0.18 |

| [HOC3C1im]Br | 1-(3-hydroxypropyl)-3-methyl-imidazolium bromide | 25.4 ± 1.24 |

| [NCC3C1im]Br | 1-(3-cyanopropyl)-3-methyl-imidazolium bromide | 20.8 ± 0.45 |

| [C1OC1C1im]Br | 1-(methoxymethyl)-3-methylimidazolium bromide | 24.1 ± 1.49 |

| [C1OC(O)C1C1im]Br | 1-(2-methoxy-2-oxoethyl)-3-methylimidazolium bromide | 18.4 ± 0.42 |

| [C1OC(O)C2C1im]Br | 1-(3-methoxy-3-oxopropyl)-3-methylimidazolium bromide | 18.3 ± 0.29 |

| [sec-C4C1im]Br | 1-(sec-butyl)-3-methylimidazolium bromide | 17.9 ± 0.24 |

| [HC1im]Br | N-methylimidazole hydrobromide | 25.1 ± 1.46 |

| [C4C1im]Cl | 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium chloride | 19.8 ± 0.64 |

| [C6C1im]Cl | 1-hexyl-3-methylimidazolium chloride | 9.67 ± 052 |

| [C8C1im]Cl | 1-methyl-3-octylimidazolium chloride | 3.89 ± 0.07 |

| [C10C1im] Cl | 1-decyl-3-methylimidazolium chloride | 0.93 ± 0.05 |

| [C4C1im]SCN | 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium thiocyanate | 7.02 ± 0.37 |

| [C4C1im]Ac | 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate | 26.8 ± 0.64 |

| [C4C1im]N(CN)2 | 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium dicyanamide | 11.6 ± 0.28 |

| [C4C1im]TFA | 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium trifluoroacetate | 27.2 ± 0.54 |

| Type of Inhibition | Ki, [mM] | α | R2 | AIC | Sy.x |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mixed | 0.77 | 3.00 | 0.96794 | -2782.048 | 8.425 × 10−9 |

| Non-competitive | 1.46 | 1 | 0.96435 | -2776.382 | 8.823 × 10−9 |

| Competitive | 0.40 | - | 0.95716 | -2762.621 | 9.670 × 10−9 |

| Uncompetitive | 0.97 | - | 0.94465 | -2743.398 | 1.099 × 10−8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).