Submitted:

07 July 2025

Posted:

07 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

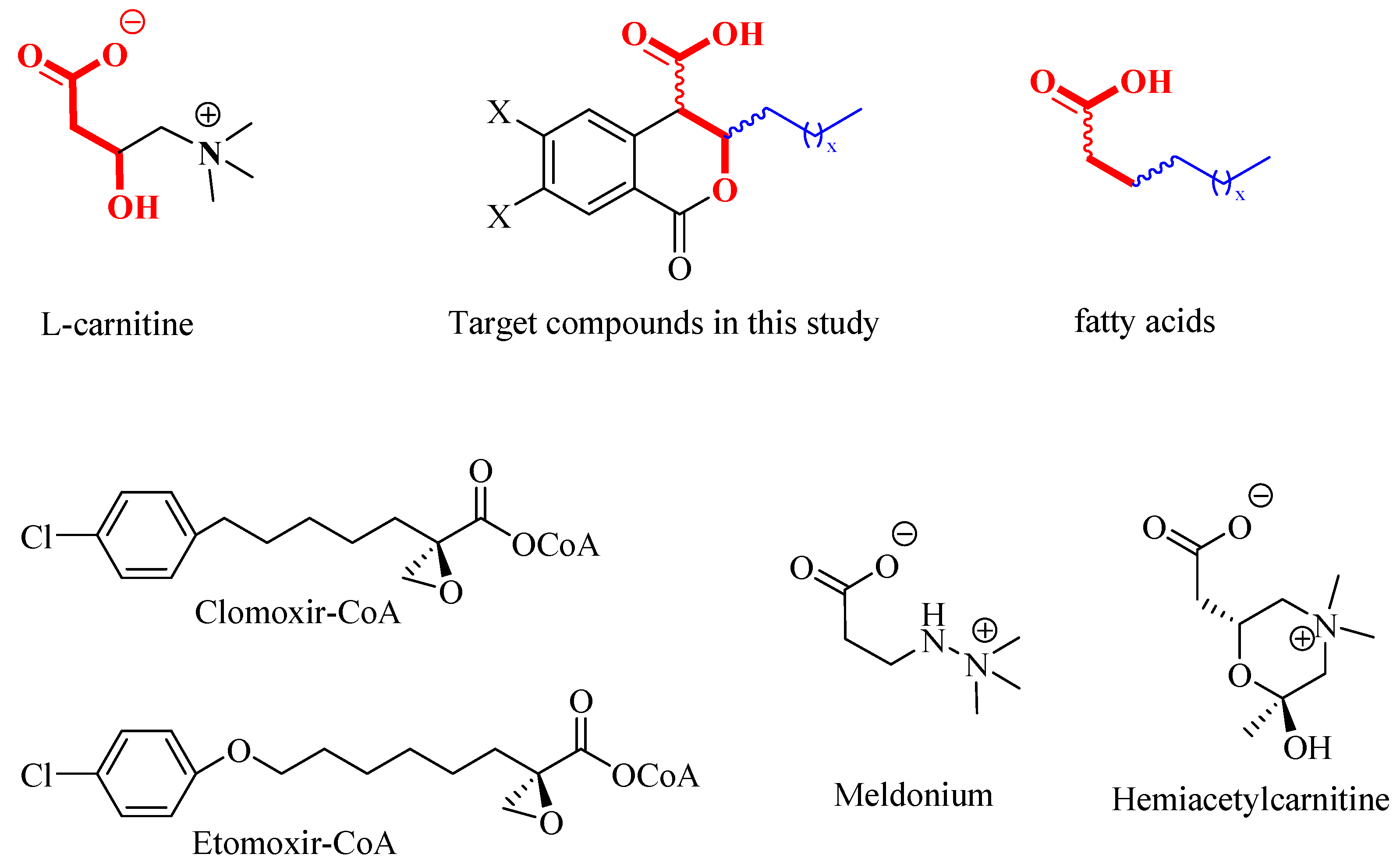

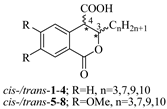

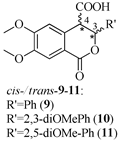

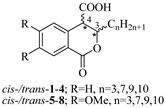

2.1. Rational Design

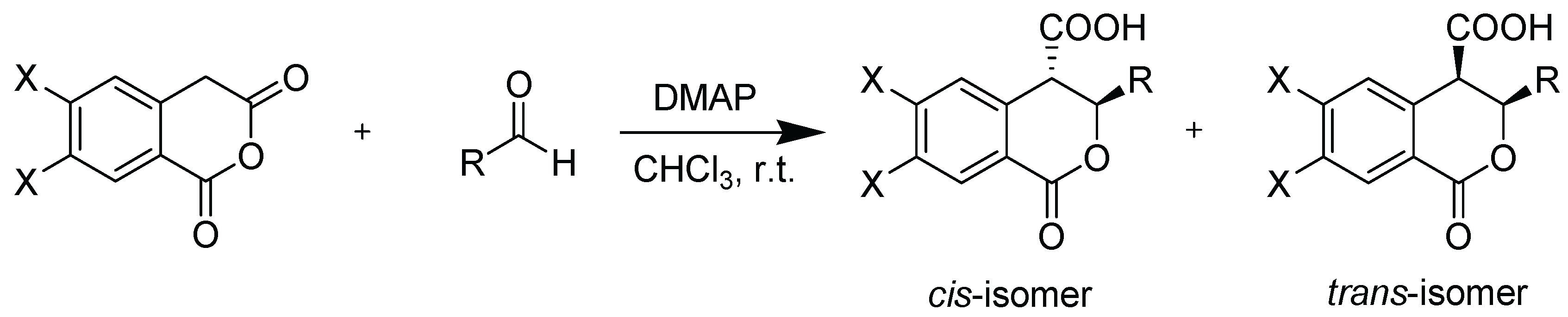

2.2. Synthesis and Characterization

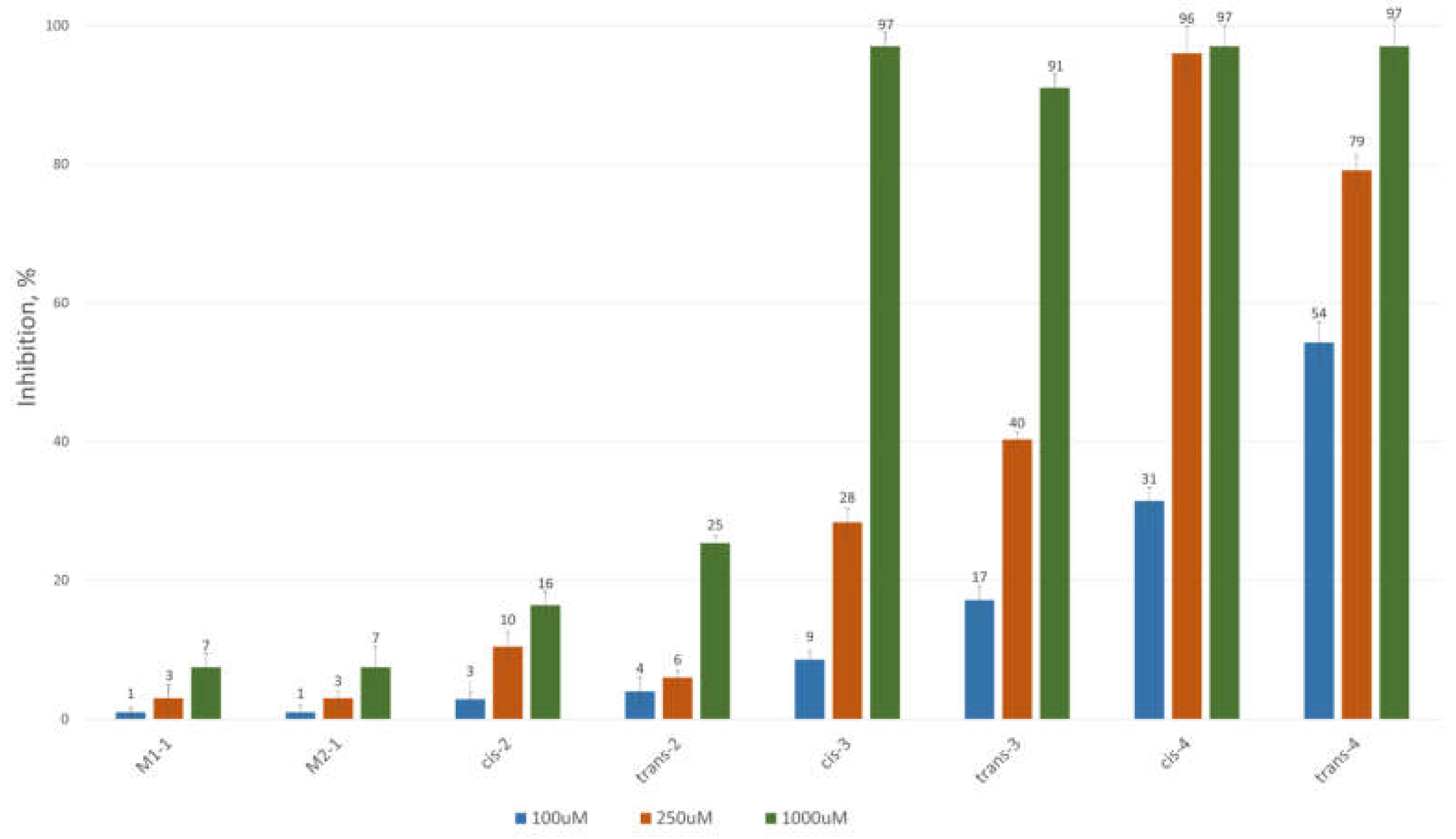

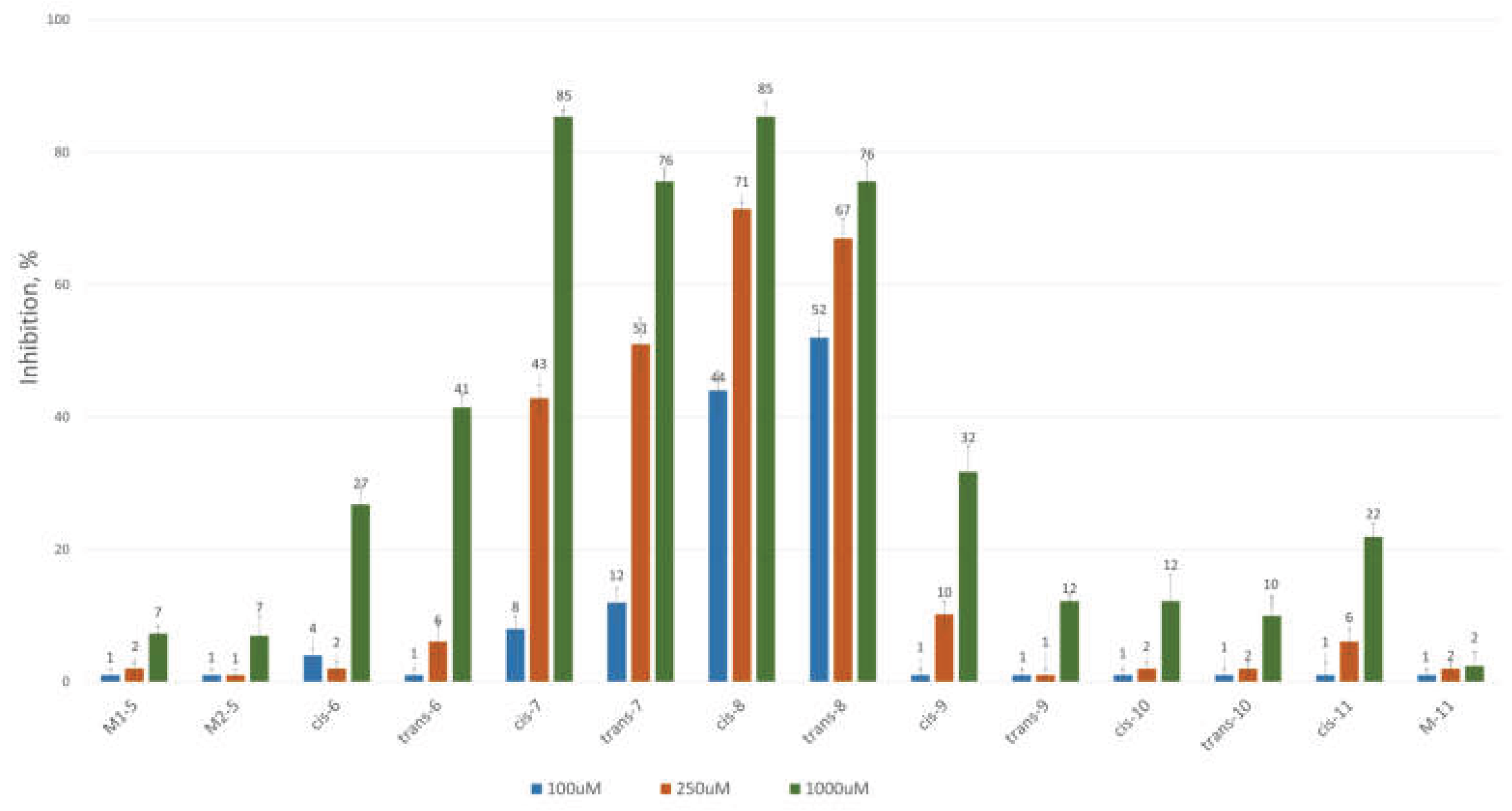

2.3. Biological Assessment

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General

3.2. Synthesis

3.2.1. cis- and trans-(±)-3-propyl-3,4-dihydro-1-oxo-1H-isochromene-4-carboxylic Acids (1)

3.2.2. cis- and trans-(±)-3-Heptyl-3,4-dihydro-1-oxo-1H-isochromene-4-carboxylic Acids (2)

3.2.3 cis- and trans-(±)-3,4-Dihydro-3-nonyl-1-oxo-1H-isochromene-4-carboxylic Acids (3)

3.2.4. cis- and trans-(±)-3-Decyl-3,4-dihydro-1-oxo-1H-isochromene-4-carboxylic Acids (4)

3.2.5. cis- and trans-(±)-3-propyl-3,4-dihydro-6,7-dimethoxy-1-oxo-1H-isochromene-4-caboxylic Acids (5)

3.2.6. cis- and trans-(±)-3-Heptyl-3,4-dihydro-6,7-dimethoxy-1-oxo-1H-isochromene-4-carboxylic Acids (6)

3.2.7. cis- and trans-(±)-3,4-Dihydro-6,7-dimethoxy-3-nonyl-1-oxo-1H-isochromene-4-carboxylic Acids (7)

3.2.8. cis- and trans-(±)-3-Decyl-3,4-dihydro-6,7-dimethoxy-1-oxo-1H-isochromene-4-carboxylic Acids (8)

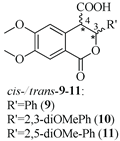

3.2.9. cis- and trans-(±)-3,4-Dihydro-6,7-dimethoxy-1-oxo-3-phenyl-1H-isochromene-4-carboxylic Acids (9)

3.2.10. cis- and trans-(±)-3,4-Dihydro-3-(2,3-dimethoxyphenyl)-6,7-dimethoxy-1-oxo-1H-isochromene-4-carboxylic Acids (10)

3.2.11. cis- and trans-(±)-3,4-Dihydro-3-(2,5-dimethoxyphenyl)-6,7-dimethoxy-1-oxo-1H-isochromene-4-carboxylic Acids (11)

3.3. In Vitro Studies

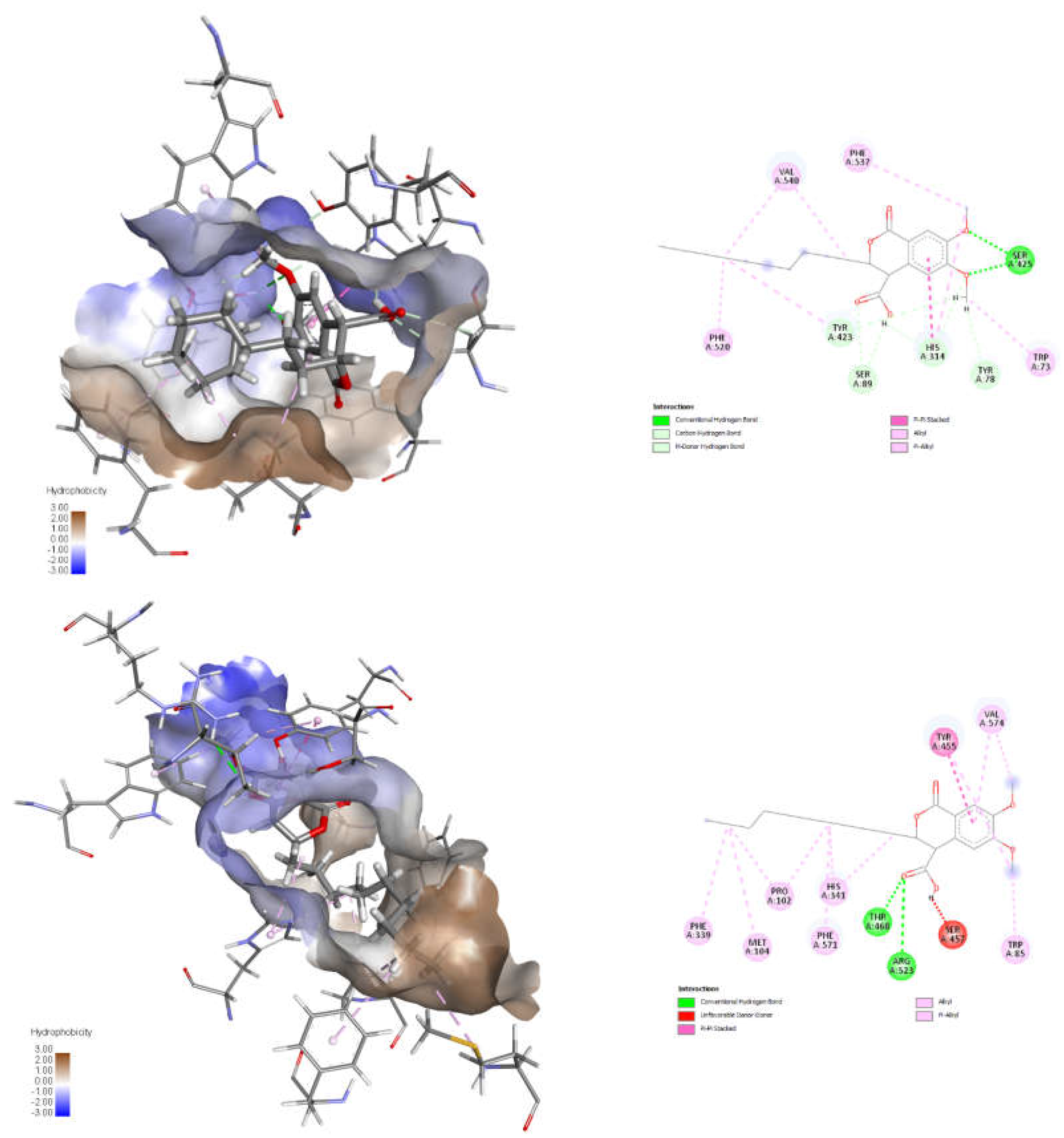

3.4. Molecular Docking

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Govindasamy, L.; Kukar, T.; Lian, W.; Pedersen, B.; Gu, Y.; Agbandje-McKenna, M.; Jin, S.; McKenna, R.; Wu, D. Structural and mutational characterization of L-carnitine binding to human carnitine acetyltransferase. J. Struct. Biol. 2004, 146, 416–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jogl, G.; Tong, L. Crystal structure of carnitine acetyltransferase and implications for the catalytic mechanism and fatty acid transport. Cell 2003, 112, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnefont, J.; Djouadi, F.; Prip-Buus, C.; Gobin, S.; Munnich, A.; Bastin, J. Carnitine palmitoyltransferases 1 and 2: Biochemical, molecular and medical aspects. Mol. Aspects Med. 2004, 25, 495–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sierra, A.; Gratacós, E.; Carrasco, P.; Clotet, J.; Ureña, J.; Serra, D.; Asins, G.; Hegardt, F.; Casals, N. CPT1c is localized in endoplasmic reticulum of neurons and has carnitine palmitoyltransferase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 6878–6885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Govindasamy, L.; Lian, W.; Gu, Y.; Kukar, T.; Agbandje-McKenna, M.; McKenna, R. Structure of human carnitine acetyltransferase. Molecular basis for fatty acyl transfer. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 13159–13165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nechaeva, G. Zheltikova, E. Effects of Meldonium in early postmyocardial infarction period. Kardiologiia 2015, 55, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liamina, N. Kotel'nikova, E., Karpova, É., Biziaeva, E., Senchikhin, V., Lipchanskaia, T. Cardioprotective capabilities of drug meldonium in secondary prevention after percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with documented myocardial ischemia. Kardiologiia 2014, 54, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keung, W. Ussher, J. R., Jaswal, J. S., Raubenheimer, M., Lam, V. H., Wagg, C. S., Lopaschuk, G. D. Inhibition of carnitine palmitoyltransferase-1 activity alleviates insulin resistance in diet-induced obese mice. Diabetes 2013, 62, 711–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Đurašević, S. Stojković, M., Bogdanović, L., Pavlović, S., Borković-Mitić, S., Grigorov, I., Bogojević, D., Jasnić, N., Tosti, T., Đurović, S., Đorđević, J., Todorović, Z. The Effects of Meldonium on the Renal Acute Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury in Rats. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Đurašević, S. Stojković, M., Sopta, J., Pavlović, S., Borković-Mitić, S., Ivanović, A., Jasnić, N., Tosti, T., Đurović, S., Đorđević, J., Todorović, Z. The effects of meldonium on the acute ischemia/reperfusion liver injury in rats. Sci. rep. 2021, 11, 1305. [Google Scholar]

- Mørkholt, A. Wiborg, O., Nieland, J. Blocking of carnitine palmitoyl transferase 1 potently reduces stress-induced depression in rat highlighting a pivotal role of lipid metabolism. Sci. Rep. 2017; 7, 2158. [Google Scholar]

- Trabjerg, M. Andersen, D., Huntjens, P., Mørk, K., Warming, N., Kullab, U., Skjønnemand, M., Oklinski, M., Oklinski, K., Bolther, L., Kroese, L., Pritchard, C., Huijbers, I., Corthals, A., Søndergaard, M., Kjeldal, H., Pedersen, C., Nieland, J. Inhibition of carnitine palmitoyl-transferase 1 is a potential target in a mouse model of Parkinson's disease. NPJ Parkinson's Dis. 2023, 9, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory, K. Elliott, G., Robertson, H., Kumar, A., Wanless, E., Webber, G., Craig, V., Andersson, G., Page, A. Mitochondrial and metabolic alterations in cancer cells. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2022, 101, 151225. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y. Chen, S., Liu, Z., Lu, Y., Xia, G., Liu, H., He, L., She, Z. Bioactive Metabolites from Mangrove Endophytic Fungus Aspergillus sp. 16-5B. Mar. drugs, 2015; 13, 3091–3102. [Google Scholar]

- Jariwala, N. Mehta, G., Bhatt, V., Hussein, S., Parker, K., Yunus, N., Parker, J., Guo, J., Gatza, M. CPT1A and fatty acid β-oxidation are essential for tumor cell growth and survival in hormone receptor-positive breast cancer. NAR cancer, 2021; zcab035. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X. Yang, C., Huang, C., Wang, W. Dysfunction of the carnitine cycle in tumor progression. Heliyon 2024, 10, e35961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monaco, M. Fatty acid metabolism in breast cancer subtypes. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 29487–29500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, M., Diesch. Diesch, J., Casquero, R., Buschbeck, M. Epigenetic-Transcriptional Regulation of Fatty Acid Metabolism and Its Alterations in Leukaemia. Front. Genet. 2018, 9, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y. Wang, Y., Li, Y., Li, Z., Kong, W., Zhao, X., Chen, S., Yan, L., Wang, L., Tong, Y., Shao, Y. Carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1A promotes mitochondrial fission and regulates autophagy by enhancing MFF succinylation in ovarian cancer. Commun. Biol. 2023, 6, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L. Chen, C., Zhao, C., Li, T., Ma, L., Jiang, J., Duan, Z., Si, Q., Chuang, T. H., Xiang, R., & Luo, Y. Targeting carnitine palmitoyl transferase 1A (CPT1A) induces ferroptosis and synergizes with immunotherapy in lung cancer. Sign. Transduct. Targ. Ther. 2024, 9–64. [Google Scholar]

- Stoyanova, S. Bogdanov, M. G. Rational Design, Synthesis, and In Vitro Activity of Heterocyclic Gamma-Butyrobetaines as Potential Carnitine Acetyltransferase Inhibitors. Molecules 2025, 30, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, A. Isocoumarins, miraculous natural products blessed with diverse pharmacological activities. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 116, 290–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, R. Isocoumarins. Developments since 1950. Chem. Rev. 1964, 64, 229–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napolitano, E. The synthesis of isocoumarins over the last decade. A review. Org. Prep. Proced. Int. 1997, 29, 631–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, A. O. Almasri, D. M., Bagalagel, A. A., Abdallah, H. M., Mohamed, S. G. A., Mohamed, G., Ibrahim, S. Naturally Occurring Isocoumarins Derivatives from Endophytic Fungi: Sources, Isolation, Structural Characterization, Biosynthesis, and Biological Activities. Molecules 2020, 25, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, H. Jabeen, F., Krohn, K., Al-Harrasi, A., Ahmad, M., Mabood, F., Shah, A., Badshah, A., Ur Rehman, N., Green, I., Ali, I., Draeger, S., Schulz, B. Antimicrobial activity of two mellein derivatives isolated from an endophytic fungus. Med. Chem. Res. 2015, 24, 2111–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, H. Krohn, K., Draeger, S., Meier, K., Schulz, B. Bioactive chemical constituents of a sterile endophytic fungus from Meliotus dentatus. Rec. Nat. Prod. 2009, 3, 114–117. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, M. Yuan, L., Guo, D., Ye, Y., Da-Wa, Z., Wang, X., Ma, F. W., Chen, L., Gu, Y., Ding, L., Zhou, Y. (2018). Bioactive halogenated dihydroisocoumarins produced by the endophytic fungus Lachnum palmae isolated from Przewalskia tangutica. Phytochem. 2018, 148, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orfali, R. Perveen, S., AlAjmI, M., Ghaffar, S., Rehman, M., AlanzI, A., Gamea, S., Essa Khwayri, M. Antimicrobial Activity of Dihydroisocoumarin Isolated from Wadi Lajab Sediment-Derived Fungus Penicillium chrysogenum: In Vitro and In Silico Study. Molecules 2022, 27, 3630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aly, A. H. Edrada-Ebel, R., Wray, V., Müller, W. E., Kozytska, S., Hentschel, U., Proksch, P., & Ebel, R. Bioactive metabolites from the endophytic fungus Ampelomyces sp. isolated from the medicinal plant Urospermum picroides. Phytochem. 2008, 69, 1716–1725. [Google Scholar]

- Furuta, T. Fukuyama, Y., Asakawa, Y. Polygonolide, an isocoumarin from Polygonum hydropiper possessing anti-inflammatory activity. Phytochem. 1986, 25, 517–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, Z. Lin, X., Lu, X., Tu, Z., Wang, J., Kaliyaperumal, K., Liu, J., Tian, Y., Xu, S., Liu, Y. Botryoisocoumarin A, a new COX-2 inhibitor from the mangrove Kandelia candel endophytic fungus Botryosphaeria sp. KcF6. J. Antibiot. 2015, 68, 653–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopklang, K. Choodej, S., Hantanong, S., Intayot, R., Jungsuttiwong, S., Insumran, Y., Ngamrojanavanich, N., Pudhom, K. Anti-Inflammatory Properties of Oxygenated Isocoumarins and Xanthone from Thai Mangrove-Associated Endophytic Fungus Setosphaeria rostrata. Molecules 2024, 29, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukandar, E. Kaennakam, S., Raab, P., Nöst, X., Rassamee, K., Bauer, R., Siripong, P., Ersam, T., Tip-pyang, S., Chavasiri, W. Cytotoxic and Anti-Inflammatory Activities of Dihydroisocoumarin and Xanthone Derivatives from Garcinia picrorhiza. Molecules 2021, 26, 6626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartlett, K. Sherratt, St., Turnbull, D. (1984). Inhibition of hepatic and skeletal muscle carnitine palmitoyltransferase I by 2[5(4-chlorophenyl)pentyl]-oxirane-2-carbonyl-CoA. Biochem. Soc. Trans., 12(4): 688–689.

- Wolf, H. Eistetter, K., Ludwig, G. (1982). Phenylalkyloxirane carboxylic acids, a new class of hypoglycaemic substances: hypoglycaemic and hypoketonaemic effects of sodium 2-[5-(4-chlorophenyl)-pentyl]-oxirane-2-carboxylate (B 807-27) in fasted animals. Diabetologia., 22(6):456-63.

- Lilly, K. Chung, C., Kerner, J., VanRenterghem, R., Bieber, L. (1992). Effect of etomoxiryl-CoA on different carnitine acyltransferases. Biochem. Pharmacol., 43(2):353-61.

- Selby, P. Sherratt, H. (1989). Substituted 2-oxiranecarboxylic acids: a new group of candidate hypoglycaemic drugs. Trends Pharmacol. Sci., 10(12):495-500.

- Jaudzems, K. Kuka, J., Gutsaits, A., Zinovjevs, K., Kalvinsh, I., Liepinsh, E., Liepinsh, E., Dambrova, M. Inhibition of carnitine acetyltransferase by mildronate, a regulator of energy metabolism. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2009, 24, 1269–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gandour, R. Colucci, W., Stelly, T., Brady, P., Brady, L. (1986). Active-site probes of carnitine acyltransferases. Inhibition of carnitine acetyltransferase by hemiacetylcarnitinium, a reaction intermediate analogue. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., 138:735-741.

- O’Connor, R.; Guo, L.; Ghassemi, S.; Snyder, N.; Worth, A.; Weng, L.; Kam, Y.; Philipson, B.; Trefely, S.; Nunez-Cruz, S.; et al. The CPT1a inhibitor, etomoxir induces severe oxidative stress at commonly used concentrations. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 6289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcule. Available online: http://mcule.com (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- Rufer, A. Thoma, R., Benz, J., Stihle, M., Gsell, B., De Roo, E., Banner, D., Mueller, F., Chomienne, O., Hennig, M. (2006). The crystal structure of carnitine palmitoyltransferase 2 and implications for diabetes treatment. Structure 2006, 14, 713–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanov, M. Palamareva, M. Cis/trans-Isochromanones. DMAP induced cycloaddition of homophthalic anhydride and aldehydes. Tetrahedron 2004, 60, 2525–2530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoyanova, S.; Bogdanov, M.G. Synthesis and Characterization of cis-/trans-(±)-3-Alkyl-3,4-dihydro-6,7-dimethoxy-1-oxo-1H-isochromene-4-carboxylic Acids. Molbank 2025, 2025, M1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanov, M.; Todorov, I.; Manolova, P.; Cheshmedzhieva, D.; Palamareva, M. Configuration and conformational equilibrium of (±)-trans-1-oxo-3-thiophen-2-yl-isochroman-4-carboxylic acid methyl ester. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004, 45, 8383–8386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miliovsky, M.; Svinyarov, I.; Mitrev, Y.; Evstatieva, Y.; Nikolova, D.; Chochkova, M.; Bogdanov, M. A novel one-pot synthesis and preliminary biological activity evaluation of cis-restricted polyhydroxy stilbenes incorporating protocatechuic acid and cinnamic acid fragments. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 66, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miliovsky, M.; Svinyarov, I.; Prokopova, E.; Batovska, D.; Stoyanov, S.; Bogdanov, M. Synthesis and Antioxidant Activity of Polyhydroxylated trans-Restricted 2-Arylcinnamic Acids. Molecules 2015, 20, 2555–2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquis, N. Fritz, I. Enzymological determination of free carnitine concentrations in rat tissues. J Lipid Res. 1964, 5, 184–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baici, A. Kinetics of Enzyme-Modifier Interactions; 1st ed.; Springer: Vienna, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Trott, O.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock Vina: Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2009, 31, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, G.M.; Huey, R.; Lindstrom, W.; Sanner, M.F.; Belew, R.K.; Goodsell, D.S.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock 4 and AutoDock Tools 4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 2009, 30, 2785–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BIOVIA Discovery Studio Visualizer. Available online: https://discover.3ds.com/discovery-studio-visualizer-download (accessed on 27 January 2025.).

|

|

|||

| Compd. | Binding Energy (kcal/mol) | |||

| (3R,4R) | (3S,4S) | (3R,4S) | (3S,4R) | |

| 1 | -5.9 (cis) | -6.5 (cis) | -6.2 (trans) | -6.1 (trans) |

| 2 | -6.2 (cis) | -6.5 (cis) | -6.5 (trans) | -5.5 (trans) |

| 3 | -6.4 (cis) | -6.4 (cis) | -6.3 (trans) | -5.5 (trans) |

| 4 | -6.2 (cis) | -5.8 (cis) | -6.1 (trans) | -6.5 (trans) |

| 5 | -6.5 (cis) | -6.0 (cis) | -5.9 (trans) | -5.9 (trans) |

| 6 | -6.6 (cis) | -5.7 (cis) | -6.4 (trans) | -6.1 (trans) |

| 7 | -6.2 (cis) | -5.6 (cis) | -6.0 (trans) | -5.9 (trans) |

| 8 | -6.0 (cis) | -5.6 (cis) | -5.4 (trans) | -6.0 (trans) |

| 9 | -6.6 (trans) | -6.9 (trans) | -6.8 (cis) | -6.9 (cis) |

| 10 | -7.0 (trans) | -7.0 (trans) | -6.4 (cis) | -6.8 (cis) |

| 11 | -6.8 (trans) | -7.0 (trans) | -6.7 (cis) | -6.4 (cis) |

| Compd. | ||||

| L-carnitine | -4.5 | |||

| acetyl-CoA | -5.8 | |||

| Meldonium | -4.5 | |||

|

|

|||

| Compd. | Binding Energy (kcal/mol) | |||

| (3R,4R) | (3S,4S) | (3R,4S) | (3S,4R) | |

| 1 | -7.6 (cis) | -7.4 (cis) | -7.2 (trans) | -7.3 (trans) |

| 2 | -6.0 (cis) | -8.4 (cis) | -7.0 (trans) | -7.6 (trans) |

| 3 | -8.2 (cis) | -7.3 (cis) | -7.5 (trans) | -7.9 (trans) |

| 4 | -7.5 (cis) | -7.6 (cis) | -7.6 (trans) | -8.1 (trans) |

| 5 | -7.4 (cis) | -7.4 (cis) | -7.2 (trans) | -7.4 (trans) |

| 6 | -7.1 (cis) | -7.1 (cis) | -7.8 (trans) | -7.0 (trans) |

| 7 | -7.7 (cis) | -7.2 (cis) | -7.5 (trans) | -7.1 (trans) |

| 8 | -7.3 (cis) | -7.7 (cis) | -7.3 (trans) | -7.7 (trans) |

| 9 | -8.6 (trans) | -8.7 (trans) | -8.1 (cis) | -8.6 (cis) |

| 10 | -8.3 (trans) | -8.3 (trans) | -8.3 (cis) | -8.3 (cis) |

| 11 | -8.5 (trans) | -8.3 (trans) | -8.3 (cis) | -8.4 (cis) |

| Compd. | ||||

| L-carnitine | -4.5 | |||

| palmitoyl-CoA | -4.6 | |||

| Meldonium | -4.4 | |||

| Etomoxir | -7.2 | |||

| Compd. |

Type of Inhibition |

α | R2 | AIC | Sy,x |

| cis-8 | mixed | 0.97 | 0.98027 | -1562.764 | 2.987 × 10-9 |

| non-competitive | 1 | 0.98027 | -1565.380 | 2.947 × 10-9 | |

| uncompetitive | - | 0.97141 | -1550.555 | 3.547 × 10-9 | |

| competitive | - | 0.93830 | -1519.782 | 5.211 × 10-9 | |

| trans-8 | mixed | 0.21 | 0.97682 | -1548.364 | 3.576 × 10-9 |

| uncompetitive | - | 0.97551 | -1548.795 | 3.626 × 10-9 | |

| non-competitive | 1 | 0.97122 | -1542.332 | 3.931 × 10-9 | |

| competitive | - | 0.89542 | -1490.723 | 7.493 × 10-9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).