Submitted:

04 August 2025

Posted:

05 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

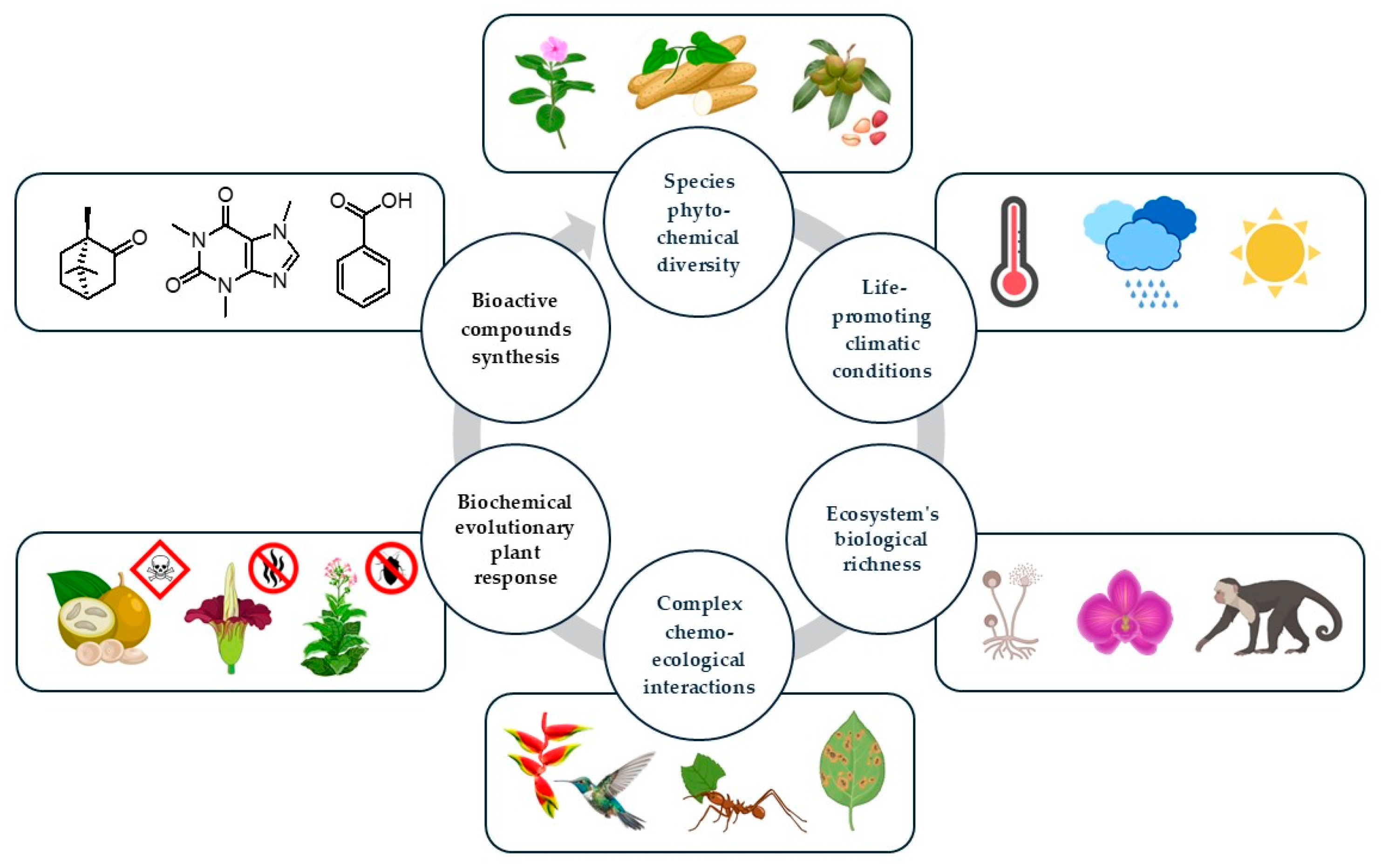

2. Diversity of Secondary Metabolites in Tropical Plants

3. Value of Bioactive Plant-Derived Products of Tropical Origin

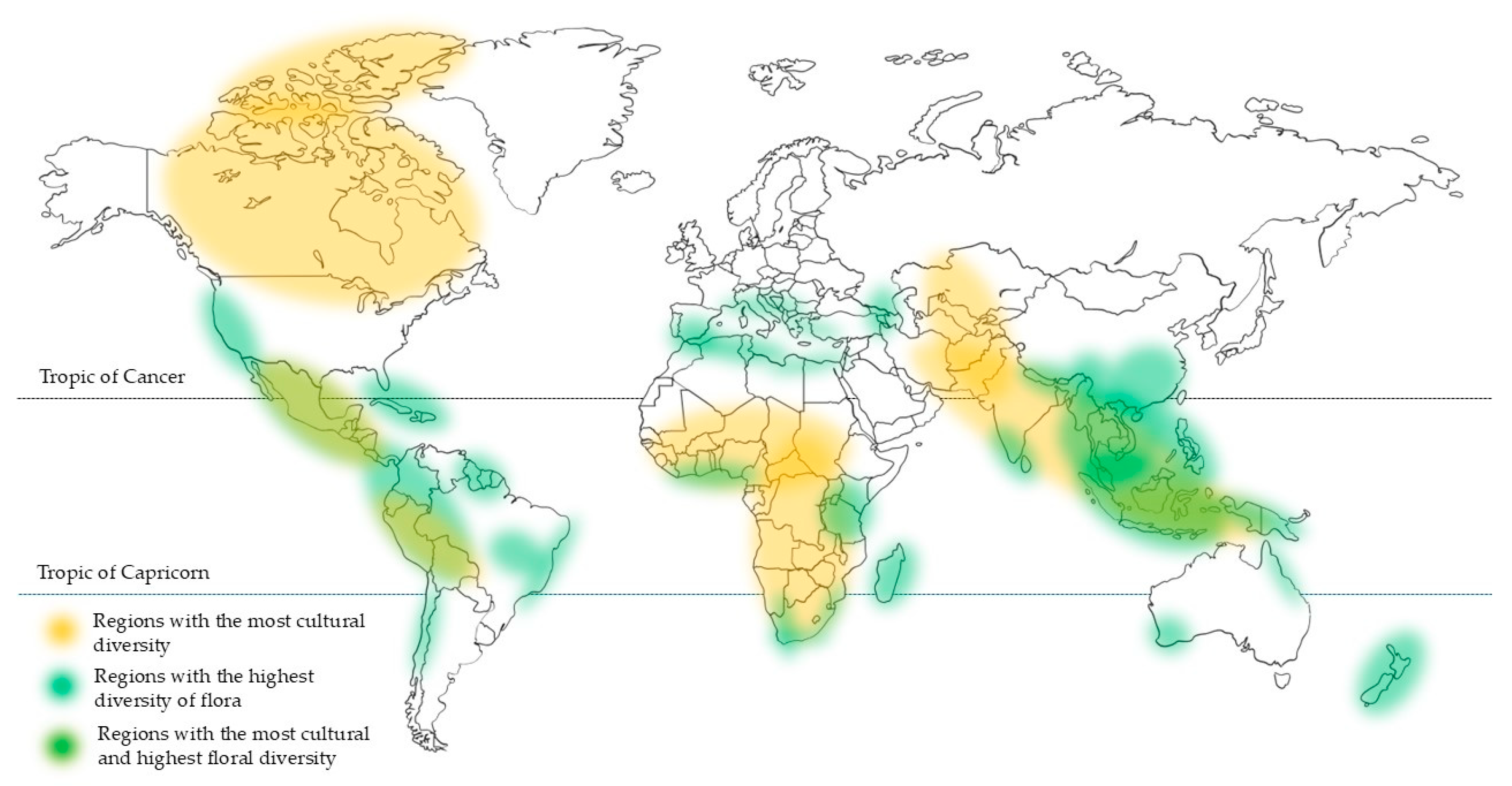

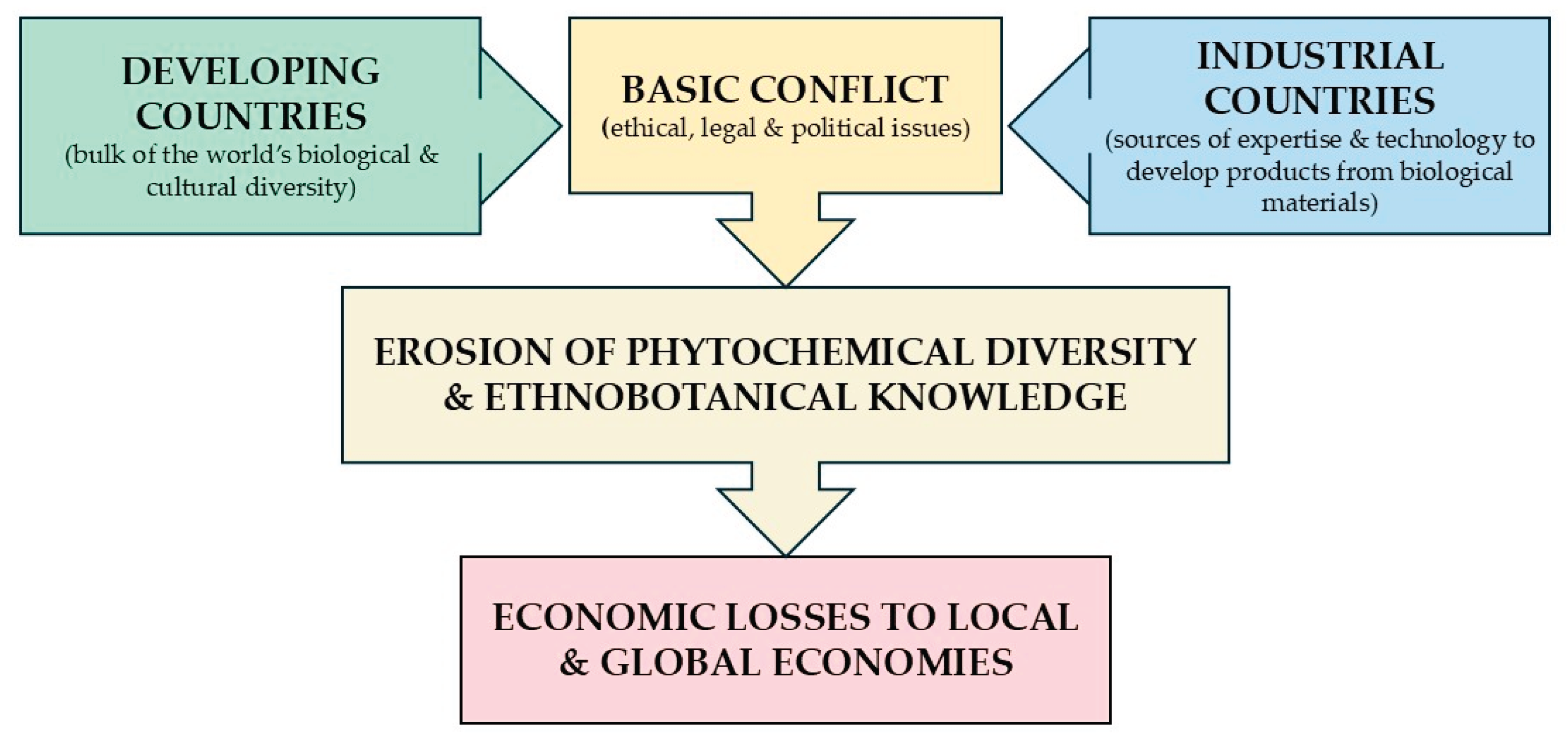

3. Potential of Bioprospecting for Novel Compounds in Tropics

3. Conclusion and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Feeley, K.J.; Stroud, J.T. Where on Earth are the “tropics”? Front. Biogeogr. 2018, 10, e38649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartshorn, G.S. Tropical forest ecosystems. In Encyclopedia of Biodiversity; Levin, S., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands 2013; pp. 269–276. [Google Scholar]

- Dounias, E. Rainforest, tropical. In The International Encyclopedia of Anthropology; Callan, H., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York City, USA; 2018; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith, F.B. Tropical rain forests — what are they really like. In Tropical Rain Forest: A Wider Perspective; Goldsmith, F.B., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, Netherlands, 1998; Conservation Biology Series, Volume 10, pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Burslem, D.F.R.P. , Garwood, N.C., Thomas, S.C. Tropical forest diversity - The plot thickens. Science 2001, 291, 606–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, M.G. , Bravo, G.A., Claramunt, S., Cuervo, A.M., Derryberry, G.E., Battilana, J., Seeholzer, G.F., McKay, J.S., O’Meara, B.C., Faircloth, B.C., Edwards, S., Perez-Eman, J., Moyle, R.G., Sheldon, F.H., Aleixo, A., Smith, B., Chesser, R.T., Silveira, L.F., Cracraft, J., Brumfield, R.T., Derryberry, E. The evolution of a tropical biodiversity hotspot. Science 2020, 370, 1343–1348. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, N. , Mittermeier, R.A., Mittermeier, C.G., da Fonseca, G.A.B., Kent, J. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 2000, 403, 853–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camara-Leret, R. , Frodin, D.G., Adema, F., Anderson, C., Appelhans, M.S., Argent, G., Guerrero, S.A., Ashton, P., Baker, W.J., Barfod, A.S., Barrington, D., Borosova, R., Bramley, G.L.C., Briggs, M., Buerki, S., Cahen, D., Callmander, M.W., Cheek, M., Chen, C.W., Conn, B.J., Coode, M.J.E., Darbyshire, I., Dawson, S., Dransfield, J., Drinkell, C., Duyfjes, B., Ebihara, A., Ezedin, Z., Fu, L.F., Gideon, O., Girmansyah, D., Govaerts, R., Fortune-Hopkins, H., Hassemer, G., Hay, A., Heatubun, C.D., Hind, D.J.N., Hoch, P., Homot, P., Hovenkamp, P., Hughes, M., Jebb, M., Jennings, L., Jimbo, T., Kessler, M., Kiew, R., Knapp, S., Lamei, P., Lehnert, M., Lewis, G.P., Linder, H.P., Lindsay, S., Low, Y.W., Lucas, E., Mancera, J.P., Monro, A.K., Moore, A., Middleton, D.J., Nagamasu, H., Newman, M.F., Lughadha, E.N., Melo, P.H.A., Ohlsen, D.J., Pannell, C,M,, Parris. B,, Pearce, L., Penneys, D.S., Perrie, L.R., Petoe, P., Poulsen, A.D., Prance, G.T., Quakenbush, J.P., Raes, N., Rodda, M., Rogers, Z.S., Schuiteman, A., Schwartsburd, P., Scotland, R.W., Simmons, M.P., Simpson, D.A., Stevens, P., Sundue, M., Testo, W., Trias-Blasi, A., Turner, I., Utteridge, T., Walsingham, L., Webber, B.L., Wei, R., Weiblen, G.D., Weigend, M., Weston, P., de Wilde, W., Wilkie, P., Wilmot-Dear, C.M., Wilson, H.P., Wood, J.R., Zhang, L.B., van Welzen, P.C. New Guinea has the world’s richest island flora. Nature 2020, 584, 579–583. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Christenhusz, M.J.M. , Fay, M.F., Clarkson, J.J., Gasson, P., Morales, J., Barrios, J.B.J., Chase, M.W. Petenaeaceae, a new angiosperm family in Huerteales with a distant relationship to Gerrardina (Gerrardinaceae). Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2010, 164, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couvreur, T.L.P. , Niangadouma, R., Sonke, B., Sauquet, H. Sirdavidia, an extraordinary new genus of Annonaceae from Gabon. PhytoKeys 2015, 46, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirzo, R. , Raven, P.H. Global state of biodiversity and loss. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2003, 28, 137–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prance, G.T. , Beentje, H., Dransfield, J., Johns, R. The tropical flora remains undercollected. Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 2000, 87, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, M. , Gibbons, S. Ethnopharmacology in drug discovery: An analysis of its role and potential contribution. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2001, 53, 425–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedio, B.E. , Parker, J.D., McMahon, S.M,, Wright, S.J. Comparative foliar metabolomics of a tropical and a temperate forest community. Ecology 2018, 99, 2647–2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stork, N.E. Tropical forest dynamics: The faunal components. Monogr. Biol. 1996, 74, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Albuquerque, U.P. , Ramos, M.A., Melo, J.G. New strategies for drug discovery in tropical forests based on ethnobotanical and chemical ecological studies. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012, 140, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulp, M. , Bohlin, L. Functional versus chemical diversity: is biodiversity important for drug discovery? Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2002, 23, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erb, M. , Kliebenstein, D.J. Plant secondary metabolites as defenses, regulators, and primary metabolites: the blurred functional trichotomy. Plant Physiol. 2020, 184, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Khayri, J.M. , Rashmi, R. , Toppo, V., Chole, P.B., Banadka, A., Sudheer, W.N., Nagella, P., Shehata, W.F., Al-Mssallem, M.Q., Alessa, F.M., Almaghasla, M.I., Rezk, A.A.S. Plant secondary metabolites: The weapons for biotic stress management. Metabolites 2023, 13, 716. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, A. , G.M., Waraich, E.A., Awan, T.H., Yavas, I., Hussain, S. Plant secondary metabolites and abiotic stress tolerance: Overview and implications. In Plant Abiotic Stress Responses and Tolerance Mechanisms; Hussain, S., Hussain Awan, T., Ahmad Waraich, E., Awan, M., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2023; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ramawat, K.G. Goyal, S. Co-evolution of secondary metabolites during biological competition for survival and advantage: An overview. In Co-evolution of Secondary Metabolites. Reference Series in Phytochemistry; Merillon, J.M., Ramawat, K., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Germany, 2019; pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich, P.R. , Raven, P.H. Butterflies and plants: a study in coevolution. Evolution 1964, 18, 586–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coley, P.D. , Heller, M.V., Aizprua, R., Arauz, B., Flores, N., Correa, M., Gupta, M., Solis, P.N., Ortega-Barria, E., Romero, L.I., Gomez, B., Ramos, M., Cubilla-Rios, L., Capson, T.L., Kursar, T.A. Using ecological criteria to design plant collection strategies for drug discovery. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2003, 1, 421–428. [Google Scholar]

- Ooka, J.K. , Owens, D.K. Allelopathy in tropical and subtropical species. Phytochem. Rev. 2018, 17, 1225–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnason, J.T. , Bernards, M.A. Impact of constitutive plant natural products on herbivores and pathogens. Can. J. Zool. 2010, 88, 615–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenes-Arguedas, T. , Horton, M.W., Coley, P.D., Lokvam, J., Waddell, R.A., Meizoso-O’Meara, B.E., Kursar, T.A. Contrasting mechanisms of secondary metabolite accumulation during leaf development in two tropical tree species with different leaf expansion strategies. Oecologia 2006, 149, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yulvianti, M. , Zidorn, C. Chemical diversity of plant cyanogenic glycosides: An overview of reported natural products. Molecules 2021, 26, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, R.J. Anthropogenic impacts on tropical forest biodiversity: a network structure and ecosystem functioning perspective. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2010, 365, 3709–3718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollenbeck, E.C. , Sax, D.F. Experimental evidence of climate change extinction risk in Neotropical montane epiphytes. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McChesney, J.D. , Venkataraman, S.K., Henri, J.T. Plant natural products: Back to the future or into extinction? Phytochemistry 2007, 68, 2015–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruetsch, Y.A. , Boni, T., Borgeat, A. From cocaine to ropivacaine: the history of local anesthetic drugs. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2001, 1, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tse, E.G. , Korsik, M., Todd, M.H. The past, present and future of anti-malarial medicines. Malar. J. 2019, 18, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soejarto, D.D. , Farnsworth, N.R. Tropical rain forests: potential source of new drugs? Perspect. Biol. Med. 1989, 32, 244–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, J.M. , Goh, N.K., Chia, L.S., Chia, T.F. Recent advances in traditional plant drugs and orchids. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2003, 24, 7–21. [Google Scholar]

- Jachak, S.M. , Saklani, A. Challenges and opportunities in drug discovery from plants. Curr. Sci. 2007, 92, 1251–1257. [Google Scholar]

- Mendelsohn, R. , Balick, M.J. The value of undiscovered pharmaceuticals in tropical forests. Econ. Bot. 1995, 49, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hai, D.V. , Quang, B.H., Bach, T.T., Binh, T.D., Choudhary, R.K., Lee, J. Tripterygium wilfordii (Celastraceae): A new generic and species record for the flora of Vietnam. Korean J. Plant Taxon. 2021, 51, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C. , He, X.J., Li, L., Lu, C., Lu, A.P. Effect of the natural product triptolide on pancreatic cancer: A systematic review of preclinical studies. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skorupan, N. , Ahmad, M.I., Steinberg, S.M., Trepel, J.B., Cridebring, D., Han, H.Y., Von Hoff, D.D., Alewine, C. A phase II trial of the super-enhancer inhibitor Minnelide™ in advanced refractory adenosquamous carcinoma of the pancreas. Future Oncol. 2022, 18, 2475–2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, M.S. Natural products to drugs: natural product-derived compounds in clinical trials. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2008, 25, 475–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambisan, P. Chapter 8 - Biodiversity and sharing of biological resources. In An Introduction to Ethical, Safety and Intellectual Property Rights Issues in Biotechnology; Nambisan, P., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2017; pp. 189–209. [Google Scholar]

- Anifowose, S.O. , Alqahtani, W.S.N., Al-Dahmash, B.A., Sasse, F., Jalouli, M., Aboul-Soud, M.A.M., Badjah-Hadj-Ahmed, A.Y., Elnakady, Y.A. Efforts in bioprospecting research: A survey of novel anticancer phytochemicals reported in the last decade. Molecules 2022, 27, 8307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efferth, T. , Banerjee, M., Paul, N., Abdelfatah, S., Arend, J., Elhassan, G., Hamdoun, S., Hamm, R., Hong, C.L., Kadioglu, O., Nass, J., Ochwangi, D., Ooko, E., Ozenver, N., Saeed, M.E.M., Schneider, M., Seo, E.J., Wu, C.F., Yan, G., Zeino, M., Zhao, Q.L., Abu-Darwish, M.S., Andersch, K., Alexie, G., Bessarab, D., Bhakta-Guha, D., Bolzani, V., Dapat, E., Donenko, F.V., Efferth, M., Greten, H.J., Gunatilaka, L., Hussein, A.A., Karadeniz, A., Khalid, H.E., Kuete, V., Lee, I.S., Liu, L., Midiwo, J., Mora, R., Nakagawa, H., Ngassapa, O., Noysang, C., Omosa, L.K., Roland, F.H,, Shahat, A.A., Saab, A,, Saeed, E.M., Shan, L.T., Titinchi, S.J.J. Biopiracy of natural products and good bioprospecting practice. Phytomedicine 2016, 23, 166–173. [Google Scholar]

- Macilwain, C. When rhetoric hits reality in debate on bioprospecting. Nature 1998, 392, 535–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijer, D. , Beniddir, M.A., Cole,y C.W., Mejri, Y.M., Ozturk, M., van der Hooft, J.J.J., Medema, M.H., Skiredj, A. Empowering natural product science with AI: Leveraging multimodal data and knowledge graphs. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2025, 42, 654–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzvetkov, N.T. , Kirilov, K., Matin, M., Atanasov, A.G. Natural product drug discovery and drug design: Two approaches shaping new pharmaceutical development. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2024, 39, 375–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfender, J.L. , Litaudon, M., Touboul, D., Queiroz, E.F. Innovative omics-based approaches for prioritisation and targeted isolation of natural products - new strategies for drug discovery. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2019, 36, 855–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockelman, W.Y. Bioprospecting in Thai forests: Is it worthwhile? Pure Appl. Chem. 1997, 70, 23–7. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, M.E. The Nagoya Protocol on Access and Benefit Sharing: International treaty poses challenges for biological collections. BioScience 2015, 65, 543–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin, R.; The most (and least) culturally diverse countries in the world. Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2013/07/18/the-most-and-least-culturally-diverse-countries-in-the-world/ (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Alves, R.R.N. , Rosa, I.M.L. Biodiversity, traditional medicine and public health: Where do they meet? J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2007, 3, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wainwright, C.L. , Teixeira, M.M., Adelson, D.L., Buenz, E.J., David, B., Glaser, K.B., Harata-Lee, Y., Howes, M.J.R., Izzo, A.A., Maffia, P., Mayer, A.M.S., Mazars, C., Newman, D.J., Lughadha, E.N., Pimenta, A.M.M., Parra, J.A.A., Qu, Z.P., Shen, H.Y., Spedding, M., Wolfender, J.L. Future directions for the discovery of natural product-derived immunomodulating drugs: An IUPHAR positional review. Pharmacol. Res. 2022, 177, 106076. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Species | Origin | Compound | Product | Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capsicum annuum L. | Mexico, Guatemala | Capsaicin | Qutenza patch (Averitas Pharma, Morristown, USA) | Treatment of neuropathic pain associated with postherpetic neuralgia or with diabetic peripheral neuropathy of the feet. |

| Hansaplast, heat plaster, pads or cream (Beiersdorf, Hamburg, Germany) | Muscle pain relief. | |||

| Catharanthus roseus (L.) G.Don | Madagascar | Vincristine | Cytocristin, vincristine sulphate injection (Cipla, Mumbai, India) | Treatment of leukaemias, malignant lymphomas, multiple myeloma, solid tumours and idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. |

| Vinblastine | Cytoblastin, vinblastine sulphate injection (Cipla, Mumbai, India) | Treatment of Hodgkin’s disease, lymphocytic and histiocytic lymphoma, mycosis fungoides, advanced carcinoma of the testis, Kaposi’s sarcoma and Letterer-Siwe disease. | ||

| Cinchona officinalis L. | Ecuador | Quinidine | Quinidine sulfate tablet (Sandoz, Princeton, USA) | Conversion and reduction of frequency of relapse into atrial fibrillation/flutter, suppression of ventricular arrhythmias and treatment of malaria. |

| Quinine | Qualaquin, quinine sulfate (Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Mumbai, India) | Treatment of uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria. | ||

| Coffea arabica L. | Ethiopia, Kenya, Sudan | Caffeine | Coffekapton (Strallhofer Pharma, Siegendorf, Austria) | Stimulation and increase performance in cases of mental and physical fatigue. Analgesic effect on headaches (e.g. migraine). |

| Coldrex tablets (Omega Pharma, UK) containing paracetamol, phenylephrine hydrdochloride, ascorbic acid, terpin hydrate and caffeine | Relief of the symptoms of influenza and colds., caffeine is present as a mild stimulant. | |||

| Peyona, caffeine citrate (CHIESI Farmaceutici, Parma, Italy) | Treatment of primary apnea of premature newborns. | |||

| Erythroxylum coca Lam. | Bolivia, Brazil North, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru | Cocaine | Numbrino, cocaine hydrochloride (Lannett Company, Philadelphia, USA) | Induction of local anesthesia of the mucous membranes when performing diagnostic procedures and surgeries on or through the nasal cavities in adults. |

| Myroxylon balsamum (L.) Harms | From Mexico to from northern South America | Benzyl benzoate | Ascabiol, topical lotion containing benzyl benzoate and sulfirame (Laboratories FRILAB SA, Geneva, Switzerland) | Treatment of scabies. Also proposed in the fall trombiculosis (mullet or chiggers). |

| Nicotiana tabacum L. | Bolivia | Nicotine | Nicorette, nicotine lozenge, gum, inhalator, nasal spray, tablet and patch (GlaxoSmithKline, Brentford, Middlesex, UK) | Help relieve cigarette cravings and nicotine withdrawal symptoms. |

| Physostigma venenosum Balf. | West Africa | Physostigmine | Anticholium, physostigmine salicylate injection (Dr. Franz Kohler Chemie, Bensheim, Germany) | For the treatment of postoperative disorders and as antidote and/or antagonist in case of intoxication. |

| Pilocarpus jaborandi Holmes | Northeast Brazil | Pilocarpine | Pilocarpine hydrochloride ophthalmic solution (Akorn, Lake Forest, US) | Reduction of elevated intraocular pressure in patients with open-angle glaucoma or ocular hypertension, management of acute angle-closure glaucoma, prevention of postoperative elevated intraocular pressure associated with laser surgery and induction of miosis. |

| Rauvolfia serpentina (L.) Benth. ex Kurz | India, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Indonesia, Burma | Reserpine | Reserpine tablets (Sandoz, Princeton, USA) | Treatment of mild to moderate hypertension. Relief of symptoms in agitated psychotic states (e.g., schizophrenia). |

| Senna alexandrina Mill. | Sahara & Sahel to Indian subcontinent | Sennoside A & B | Pursennide (Novartis International, Basel, Switzerland) | Symptomatic treatment of constipation. |

| Styrax benzoin Dryand. | Bangladesh, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Thailand, Vietnam | Benzoic acid | Whitfield’s ointment containing benzoic and salicylic acids (Lambsmead, Richmond, UK) | Topical treatment of dermatophyte infections. Also used to treat skin conditions such as eczema, psoriasis and skin inflammation and irritations caused by burns and insect bites. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).