1. Introduction

Prostate cancer is the second most common malignancy among men and represents a major cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide[

1]. The clinical course of the disease is highly heterogeneous[

2]. While localized stages can be effectively managed with surgery or radiotherapy, advanced cases often require systemic therapy[

3]. Due to the central role of androgens in the development and progression of prostate cancer, androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) is considered the standard first-line treatment[

4]. ADT is typically achieved through pharmacological castration using luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) agonists or antagonists, or through surgical orchiectomy, and is initially effective in the majority of patients. However, over time, many cases develop resistance to androgen deprivation and progress to the so-called “castration-resistant” phase[

5].

Metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) is defined as prostate cancer that progresses biochemically, radiologically, or clinically despite ADT, with evidence of distant metastasis. This stage represents the most aggressive form of the disease and is associated with significantly worse prognosis[

6,

7]. Continued tumor progression despite serum testosterone levels below 50 ng/dL suggests that tumor cells can activate androgen receptor (AR) signaling pathways via alternative mechanisms[

8]. Systemic treatment options in this phase include chemotherapy (e.g., docetaxel, cabazitaxel), radioisotope therapies (e.g., 177Lu-PSMA), immunotherapies, and targeted agents[

9,

10].

In the past decade, next-generation agents targeting the androgen receptor (AR) signaling pathways, particularly abiraterone acetate and enzalutamide, have transformed the treatment landscape of mCRPC by demonstrating significant survival benefits in both clinical trials and real-world settings[

11,

12]. Abiraterone (ABI), a CYP17A1 inhibitor that suppresses androgen production from adrenal and testicular sources, is combined with prednisone and has shown efficacy both before and after chemotherapy (COU-AA-302 and COU-AA-301)[

13,

14]. Enzalutamide (ENZA), a potent AR antagonist, blocks multiple steps of AR signaling and improved survival in both pre- and post-chemotherapy settings (PREVAIL and AFFIRM)[

15,

16]. These agents are now widely used, especially in patients unfit for chemotherapy

In recent years, growing awareness of the role of systemic inflammation in the tumor microenvironment has spurred interest in the prognostic value of systemic inflammatory markers (SIM) such as the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR)[

17,

18]. While neutrophils may promote tumor progression, lymphocytes play a central role in antitumor immunity; thus, an imbalance in these ratios may reflect a disturbed immune-inflammatory response. Due to their affordability, accessibility, and reproducibility, these markers are emerging as practical prognostic tools in clinical practice[

19].

In this context, the present study aimed to evaluate the prognostic impact of SIM—particularly NLR and PLR—assessed before ABI/ENZA therapy in patients with mCRPC, with respect to PSA response, clinical response to treatment, and survival outcomes. This study seeks to contribute to the literature by supporting the integration of low-cost, easily applicable prognostic indicators into clinical decision-making.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Centers

This retrospective, two-center observational study was conducted to evaluate the prognostic role of pre-treatment SIM on treatment response and survival outcomes in patients with mCRPC treated with ABI/ENZA. The study was carried out at the Departments of Medical Oncology of Istanbul Bezmialem University and Istanbul Medipol University Department of Medical Oncology.

2.2. Patient Selection

Patients diagnosed with mCRPC and treated with ABI or ENZA between January 2018 and December 2024 at either center were retrospectively reviewed. Inclusion criteria were:

(1) Histologically confirmed prostate adenocarcinoma,

(2) Castration-resistant disease defined by biochemical, radiological, or clinical progression despite castrate levels of testosterone (<50 ng/dL),

(3) Initiation of at least one cycle of ABI or ENZA,

(4) Availability of baseline clinical variables, PSA data, and pre-treatment complete blood count parameters.

Patients were excluded if they lacked laboratory data from the pre-treatment or initial follow-up period, had concurrent malignancies, or were lost to follow-up. Since the study aimed to assess SIM, patients with conditions that might confound inflammatory markers—such as active infections, advanced heart failure (NYHA Class III or above), chronic kidney disease, or autoimmune/rheumatologic disorders—were also excluded.

2.3. Data Collection

Data were obtained from electronic medical record systems and patient files. Collected variables included demographics (age), disease characteristics (Gleason score, prior treatments such as ADT or docetaxel, and the number of systemic treatment lines prior to ABI/ENZA), ECOG performance status (PS), treatment response (clinical assessment and changes in prostate-specific antigen [PSA]), dates of progression and death, and SIM measured at baseline and during the first post-treatment evaluation. Among these parameters were complete blood count-derived markers, including mean platelet volume (MPV), platelet distribution width (PDW), and platelet-large cell ratio (P-LCR). SIM, namely NLR and PLR, were calculated from respective cell counts[

20].

2.4. Variable Definitions

PSA response: Defined as a ≥50% decrease from baseline PSA levels (confirmation applied per institutional protocols).

Treatment response (clinical/composite): Defined as a binary variable (“response” vs. “no response”) incorporating PSA response, radiological evaluation, and clinical findings.

NLR and PLR thresholds: Based on ROC analysis and existing literature, thresholds were set at 2.83 for NLR and 156 for PLR; variables were dichotomized accordingly (≤ vs. >).

2.5. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 27.0. Continuous variables were presented as median (minimum–maximum) or mean ± standard deviation, and categorical variables as counts and percentages. Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used for paired comparisons of pre- and post-treatment values. Progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) probabilities were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and differences between groups were compared using the log-rank test.

To identify independent prognostic factors for PFS and OS, variables (clinical covariates, NLR, PLR, ECOG PS, treatment response, etc.) were first evaluated in univariate analysis and then included in a Cox proportional hazards regression model. Results were reported as hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). A two-sided p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

2.6. Ethical Approval

The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was obtained from the Non-Interventional Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Istanbul Medipol University (Approval No: 1212; Date: November 28, 2024). The Department of Medical Oncology at Bezmialem University provided institutional approval for patient data contribution. Patient identities were kept confidential, and data were anonymized prior to analysis.

3. Results

A total of 106 patients with mCRPC were included in the study. The median age at diagnosis was 69 years (range: 40–90), and the median PSA level at diagnosis was 82 ng/mL (range: 4–214.4). The median PSA level prior to initiating ABI/ENZA therapy was 2.84 ng/mL (range: 0.84–14.84). The most common Gleason score pattern was 4+5, observed in 41.5% of patients.

During the castration-sensitive phase, 52.8% of patients received ADT alone, while 47.2% received docetaxel plus ADT. In the castration-resistant setting, the most frequently administered first-line treatments were ENZA (48.1%) and ABI (30.2%). Prior docetaxel use before ABI/ENZA was reported in 63.2% of patients.

Regarding baseline ECOG PS, 19.8% of patients had an ECOG PS of 0, 77.4% had ECOG PS 1, and 2.8% had ECOG PS 2. ABI/ENZA was used as first-line therapy in 78.3% of patients in the mCRPC setting. The clinical response rate was 70.8%, and the PSA response rate was also 70.8%.

NLR was ≤2.83 in 48.1% of patients, and PLR was ≤156 in 49.1% of patients. All baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients are summarized in

Table 1.

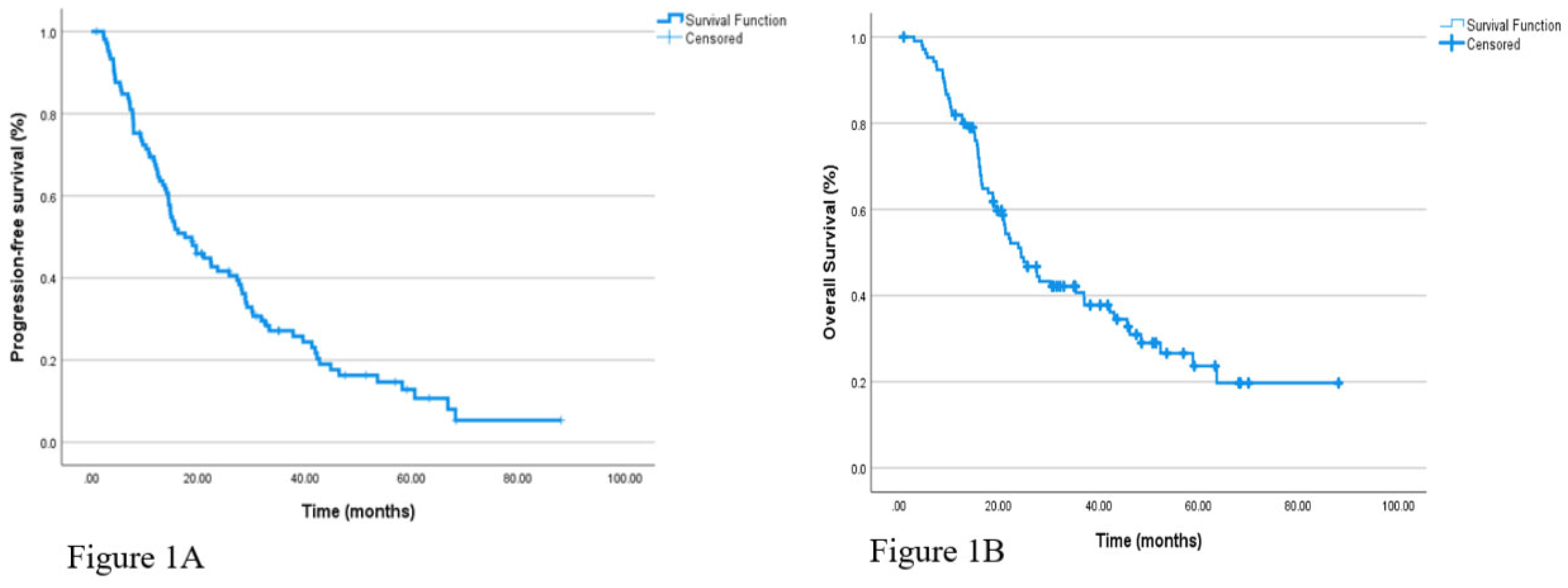

The median follow-up duration in the overall cohort was 28.3 months. During this period, PFS, as evaluated by Kaplan-Meier analysis, was calculated as a median of 17.5 months (95% CI: 11.99–23.07) for all patients. Similarly, the median OS was found to be 24.4 months (95% CI: 18.6–30.2). Kaplan-Meier survival curves for PFS and OS are presented in

Figure 1.

In the subgroup analysis based on treatment regimen, the median PFS was 19.6 months (95% CI: 12.6–26.7) in patients who received ADT alone, and 14.8 months (95% CI: 9.0–20.6) in those who received a combination of ADT and docetaxel. However, this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.618). Similarly, when patients were grouped based on whether they had received docetaxel prior to ABI/ENZA therapy, the median PFS was 19.6 months (95% CI: 7.4–31.8) in those without prior docetaxel and 15.6 months (95% CI: 10.5–20.6) in those with prior docetaxel exposure, with no significant difference observed (p= 0.896).

Kaplan-Meier analysis according to ECOG PS revealed a median PFS of 18.8 months (95% CI: 1.3–36.4) in patients with ECOG PS 0, 17.5 months (95% CI: 11.6–23.5) in those with ECOG PS 1, and 22.4 months (95% CI: 9.7–35.2) in the small subgroup with ECOG PS 2. The difference between groups was not statistically significant (p = 0.963).

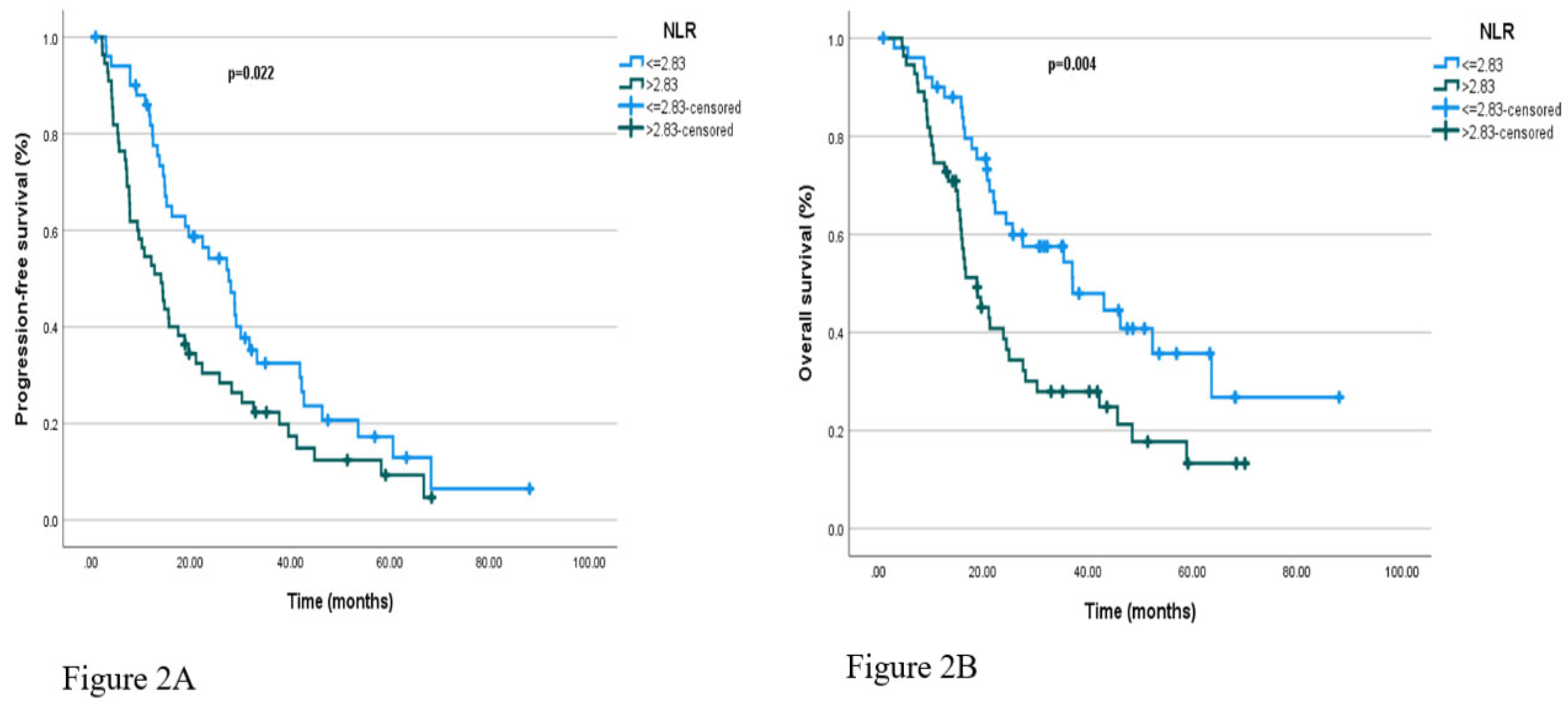

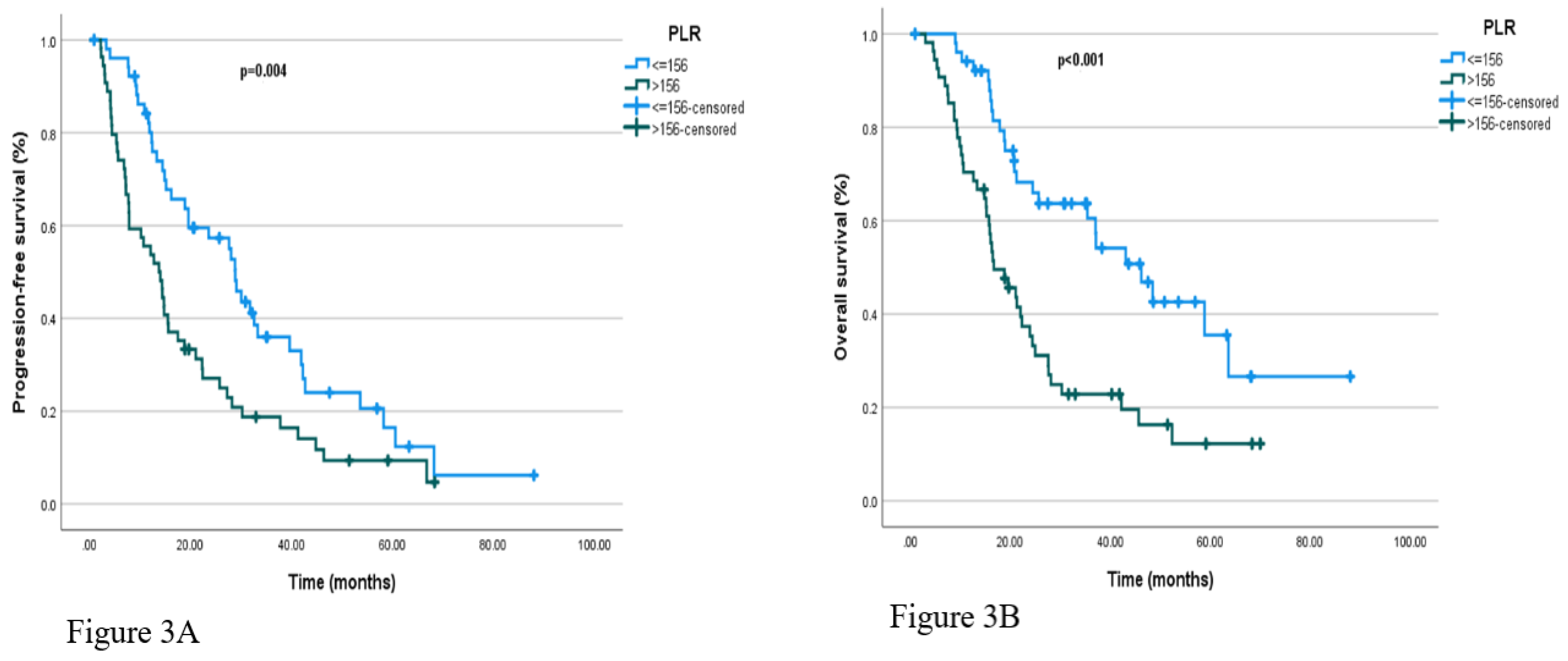

Regarding hematologic markers, patients with NLR ≤2.83 had a median PFS of 27.7 months (95% CI: 19.8–35.5), compared to 14.1 months (95% CI: 9.4–18.8) in those with NLR>2.83 (p = 0.022). Similarly, median PFS was 28.9 months (95% CI: 25.9–31.9) in patients with PLR ≤156, and 13.8 months (95% CI: 9.3–18.3) in those with PLR >156, with the difference reaching statistical significance (p=0.022 and p = 0.004, respectively). Kaplan-Meier curves illustrating PFS according to baseline NLR and PLR categories are presented in

Figure 2A and

Figure 3A, respectively.

To evaluate changes in selected hematological parameters before and after ABI/ENZA treatment, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was performed. No statistically significant differences were observed in any parameter. The median MPV values before and after treatment did not differ significantly (Z = –0.467, p = 0.640). Similarly, no significant changes were observed in P-LCR percentage (Z = –1.199, p = 0.231), MPV/PDW ratio (Z = –1.576, p = 0.115), or PDW levels (Z = –1.651, p = 0.099). These findings suggest that the evaluated hematologic parameters did not change significantly following treatment.

In the analysis based on treatment response, patients who responded to therapy had a median PFS of 28.2 months (95% CI: 24.7–31.8), compared to 7.8 months (95% CI: 6.9–8.7) in non-responders. The corresponding mean PFS durations were 33.8 and 10.6 months, respectively. This difference was statistically significant (p <0.001), indicating that response to therapy is a strong predictor of PFS.

Regarding PSA levels, the median pre-treatment PSA was 9.00 ng/mL (range: 0–66,495), which decreased to 0.84 ng/mL (range: 0–51,508) after treatment. This change was found to be statistically significant (Z = –6.283, p <0.001), with 85.7% of patients demonstrating a meaningful decline in PSA levels.

In the OS subgroup analysis based on treatment regimen, the median OS was 22.0 months (95% CI: 17.3–26.7) in patients who received ADT alone, and 27.6 months (95% CI: 17.8–37.4) in those treated with ADT plus docetaxel; this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.884). Similarly, when comparing OS by the line of systemic therapy in which ABI/ENZA was used, the median OS was 25.7 months (95% CI: 16.8–34.5) for first-line and 31.6 months (95% CI: 12.3–35.5) for later lines, with no significant difference (p = 0.637).

In the analysis based on prior docetaxel or similar therapy, the median OS was 22.0 months (95% CI: 16.9–27.1) in patients without prior therapy and 25.0 months (95% CI: 18.4–31.5) in those with prior treatment, again showing no significant difference (p = 0.744).

When stratified by ECOG PS, median OS was 37.0 months (95% CI: 13.4–60.6) in patients with ECOG PS 0, 22.0 months (95% CI: 17.1–27.0) in those with ECOG PS 1, and 0.24 months (95% CI: 0.0–48.6) in those with ECOG PS 2. The mean OS durations were 37.4, 38.2, and 20.4 months, respectively. These differences were not statistically significant (p = 0.498).

In the survival analysis based on baseline NLR, patients with NLR ≤2.83 had a median OS of 37.1 months (95% CI: 18.7–55.5), whereas those with NLR>2.83 had a median OS of 18.8 months (95% CI: 13.5–24.1), with a statistically significant difference (p = 0.004). Similarly, in the analysis based on PLR, the median OS was 46.2 months (95% CI: 33.5–58.9) in patients with PLR ≤156, compared to 16.7 months (95% CI: 10.9–22.5) in those with PLR >156; this difference was also statistically significant (p <0.001). These results suggest that elevated PLR and NLR values may be associated with poorer prognosis. Kaplan-Meier curves for OS according to baseline NLR and PLR categories are shown in

Figure 2B and

Figure 3B, respectively.

Details of the univariate analysis, including median durations and statistical significance levels of variables associated with PFS and OS, are summarized in

Table 2.

In the multivariate Cox regression analysis for PFS, the model included PLR, NLR, ECOG PS, and treatment response. The overall model was statistically significant (χ² = 49.609, df = 4, p <0.001). Among the included variables, only treatment response was significantly associated with a lower risk of progression (Hazard Ratio [HR]: 4.308, 95% CI: 2.634–7.046; p <0.001). Although elevated PLR showed a trend toward increased risk of progression, it did not reach statistical significance (HR: 1.720, 95% CI: 0.967–3.061; p = 0.065). No significant associations were observed between PFS and NLR (p = 0.845) or ECOG PS (p = 0.475). These findings suggest that, on multivariate analysis, treatment response was the only independent predictor of PFS.

In the multivariate analysis for OS, patients with PLR >156 had significantly worse survival compared to those with PLR ≤156 (HR: 2.01, 95% CI: 1.09–3.72; p = 0.026). In contrast, NLR category, ECOG PS, and treatment response were not significantly associated with OS (p> 0.05). These results indicate that PLR may serve as an independent prognostic factor for overall survival.

4. Discussion

In this study, we analyzed the prognostic impact of SIMs—namely the NLR and PLR—on PFS and OS in patients with mCRPC prior to treatment with ABI/ENZA. Our findings demonstrated that both NLR and PLR levels were significantly associated with survival outcomes, and notably, elevated PLR was identified as an independent risk factor for OS. These results support the growing body of literature emphasizing the prognostic role of inflammation-based hematologic parameters in recent years.

In our cohort, patients with lower pre-treatment NLR (<2.83) had significantly longer PFS, consistent with findings reported by Pisano et al., who showed that mCRPC patients with NLR >3 experienced significantly shorter PFS and OS after ABI/ENZA therapy. Although NLR was significantly associated with PFS in univariate analysis in our study, this significance was lost in multivariate analysis, suggesting that the impact of NLR on clinical outcomes may depend on additional factors such as PSA response or ECOG PS.

PLR, on the other hand, appeared to have a stronger prognostic significance in our analysis. Patients with PLR >156 had significantly shorter OS (p = 0.006), and high PLR remained an independent prognostic factor in multivariate analysis (HR: 2.01; p = 0.026). This finding aligns with the meta-analysis by Guan et al., which included 11 studies and concluded that elevated PLR was associated with poor survival in mCRPC, with a particularly strong impact on OS[

19].

Similarly, Salciccia et al. highlighted the prognostic value of both NLR and PLR in a comprehensive meta-analysis that included both metastatic and non-metastatic prostate cancer patients. However, they emphasized that these markers had a more pronounced prognostic role in the metastatic subgroup[

21]. Our study, which focused solely on mCRPC patients, further supports the clinical relevance of PLR within this population.

Interestingly, in our study, patients who responded to treatment had significantly longer PFS and OS. In multivariate analysis, treatment response emerged as the only independent predictor of PFS. This highlights the critical influence of early therapeutic response on survival and suggests that biological response markers (e.g., inflammatory indices) may not be sufficient as standalone prognostic tools. This observation is in line with subgroup findings from the CARD trial, which reported that high NLR was associated with poor response to AR inhibitors like ABI/ENZA, and switching to cabazitaxel may be more advantageous in such patients[

22].

Moreover, Guan et al. reported that PLR might be a more stable marker than NLR, which can be affected by infections, steroid use, and various immune conditions[

19]. These biological differences may explain the stronger prognostic value of PLR observed in our study.

In another study by Fukuokaya et al., which examined PLR along with other platelet parameters, high MPV was associated with poor prognosis in patients treated with ABI, but this association was not observed with ENZA [

23]. This suggests that inflammation-related markers may have treatment-specific prognostic implications. Although our study did not conduct separate analyses for ABI and ENZA due to limited sample size, PLR was found to hold prognostic value regardless of treatment agent.

We also assessed the potential changes in hematologic parameters before and after ABI/ENZA therapy using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. No statistically significant differences were observed in MPV, P-LCR, PDW, or the MPV/PDW ratio. These results indicate that these inflammatory markers carry prognostic information primarily in the pre-treatment period and remain relatively stable throughout treatment. This may reflect that these indices are systemic manifestations of tumor-related inflammation and that hormonal therapies such as ABI/ENZA do not exert direct suppressive effects on these hematologic reflections.

Similarly, Fukuokaya et al. found that platelet indices like MPV and PDW had prognostic significance at baseline but did not change significantly during treatment with ABI/ENZA[

23]. These findings suggest that inflammation-based hematologic markers may be better interpreted as static prognostic indicators rather than dynamic biomarkers. On the other hand, the lack of post-treatment changes might indicate that AR inhibitors have no direct anti-inflammatory effects in this patient population. Therefore, the prognostic and predictive roles of changes in inflammatory markers post-treatment remain controversial and require validation in larger, prospective studies.

Finally, a meta-analysis by Zhou et al. demonstrated that patients with high inflammatory markers had higher recurrence rates even after radical treatments, suggesting that inflammation is a biologically relevant prognostic mechanism across all stages of disease[

24].

Taken together, our findings indicate that inflammation-based markers, which are low-cost, widely accessible, and easily integrated into clinical practice, have prognostic value in the mCRPC setting. However, prospective studies with larger sample sizes and more homogeneous patient populations are warranted before these markers can be routinely used to guide clinical decision-making.

5. Conclusions

In this study, the prognostic value of SIMs measured before ABI/ENZA treatment was evaluated in patients with mCRPC. The findings demonstrated that PLR was a significant predictor of OS. PLR appears to be a low-cost and clinically applicable prognostic marker that can be assessed prior to treatment. While NLR was significantly associated with PFS in univariate analysis, it did not retain independent prognostic significance in multivariate analysis.

In our study, patients who responded to treatment had significantly longer PFS, and treatment response emerged as the strongest predictor of PFS in multivariate analysis. This suggests that achieving an early clinical response plays a central role in determining disease trajectory. On the other hand, no significant changes were observed in MPV, PDW, or P-LCR after ABI/ENZA treatment, indicating that these inflammation-based markers may serve as static prognostic tools rather than dynamic indicators of treatment response.

Overall, the findings suggest that SIMs such as NLR and PLR—particularly when assessed at baseline—may have potential in risk stratification and personalized treatment planning. Despite the increasing use of molecular biomarkers, these parameters offer practical and economic advantages due to their simplicity and accessibility.

However, this study has certain limitations, including its retrospective design, relatively small sample size, and heterogeneous follow-up duration. Further prospective, multicenter studies with larger cohorts are needed to confirm the clinical applicability of our findings.

In conclusion, simple hematologic parameters such as NLR and especially PLR may provide meaningful prognostic information in patients with mCRPC and may contribute to the development of individualized treatment strategies in this population.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.M., E.S., L.Ş.C., Ö.Y., Ö.A., Ö.F.Ö. and J.H.; methodology, H.M., M.Ş. and E.S.; software, H.M., L.Ş.C., A.B., Ö.A., Ö.F.Ö. and J.H.; validation, H.M., M.Ş. and H.Ö.; formal analysis, H.M. and A.B; investigation, H.M.; resources, H.M. and A.B.; data curation, H.M., H.Ö., Ö.A., J.H., Ö.F.Ö. and Ö.Y.; initial manuscript drafting was carried out by H.M., and A.B.; H.M. was responsible for manuscript revision and editing; data visualization was performed by H.M.; supervision was led by A.B.; H.M. and E.S. managed project coordination and oversight. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethical Institutional Review Board (Approval No: 1212; Date: November 28, 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bray F: Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A.Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries.CA: a cancer journal for clinicians.2018;68(6):394-424. [CrossRef]

- Van Poppel H, Roobol MJ, Chapple CR, Catto JW, N’Dow J, Sønksen J, et al.Prostate-specific antigen testing as part of a risk-adapted early detection strategy for prostate cancer: European Association of Urology position and recommendations for 2021.European Urology.2021;80(6):703-11. [CrossRef]

- Mottet N, Bellmunt J, Bolla M, Briers E, Cumberbatch MG, De Santis M, et al.EAU-ESTRO-SIOG Guidelines on Prostate Cancer. Part 1: Screening, Diagnosis, and Local Treatment with Curative Intent.European Urology.2017;71(4):618-29. [CrossRef]

- Parker C, Castro E, Fizazi K, Heidenreich A, Ost P, Procopio G, et al.Prostate cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up†.Annals of Oncology.2020;31(9):1119-34. [CrossRef]

- Aliberti A, Bada M, Rapisarda S, Natoli C, Schips L, Cindolo L.Adherence to hormonal deprivation therapy in prostate cancer in clinical practice: a retrospective, single-center study.Minerva Urol Nefrol.2019;71(2):181-4. [CrossRef]

- Le TK, Duong QH, Baylot V, Fargette C, Baboudjian M, Colleaux L, et al.Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer: From Uncovered Resistance Mechanisms to Current Treatments.Cancers.2023;15(20):5047. [CrossRef]

- ŞEN F.Kastrasyon Dirençli Metastatik Prostat Kanserli Hastaya Yaklaşım.Turkiye Klinikleri Medical Oncology-Special Topics.2015;8(3):39-50.

- Quistini A, Chierigo F, Fallara G, Depalma M, Tozzi M, Maggi M, et al.Androgen Receptor Signalling in Prostate Cancer: Mechanisms of Resistance to Endocrine Therapies.Res Rep Urol.2025;17:211-23. [CrossRef]

- Poon DMC, Cheung WSK, Chiu PKF, Chung DHS, Kung JBT, Lam DCM, et al.Treatment of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: review of current evidence and synthesis of expert opinions on radioligand therapy.Frontiers in Oncology.2025;Volume 15 - 2025. [CrossRef]

- He L, Fang H, Chen C, Wu Y, Wang Y, Ge H, et al.Metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: Academic insights and perspectives through bibliometric analysis.Medicine.2020;99(15):e19760. [CrossRef]

- George DJ, Ramaswamy K, Yang H, Liu Q, Zhang A, Greatsinger A, et al.Real-world overall survival with abiraterone acetate versus enzalutamide in chemotherapy-naïve patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer.Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis.2024;27(4):756-64. [CrossRef]

- Shore ND, Ionescu-Ittu R, Laliberté F, Yang L, Lejeune D, Yu L, et al.Beyond Frontline Therapy with Abiraterone and Enzalutamide in Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer: A Real-World US Study.Clin Genitourin Cancer.2021;19(6):480-90. [CrossRef]

- Ryan CJ, Smith MR, Fizazi K, Saad F, Mulders PFA, Sternberg CN, et al.Abiraterone acetate plus prednisone versus placebo plus prednisone in chemotherapy-naive men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (COU-AA-302): final overall survival analysis of a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study.The Lancet Oncology.2015;16(2):152-60. [CrossRef]

- Bono JSd, Logothetis CJ, Molina A, Fizazi K, North S, Chu L, et al.Abiraterone and Increased Survival in Metastatic Prostate Cancer.New England Journal of Medicine.2011;364(21):1995-2005. [CrossRef]

- Beer TM, Armstrong AJ, Rathkopf DE, Loriot Y, Sternberg CN, Higano CS, et al.Enzalutamide in Metastatic Prostate Cancer before Chemotherapy.New England Journal of Medicine.2014;371(5):424-33. [CrossRef]

- Scher HI, Fizazi K, Saad F, Taplin M-E, Sternberg CN, Miller K, et al.Increased Survival with Enzalutamide in Prostate Cancer after Chemotherapy.New England Journal of Medicine.2012;367(13):1187-97. [CrossRef]

- Kumarasamy C, Tiwary V, Sunil K, Suresh D, Shetty S, Muthukaliannan GK, et al.Prognostic Utility of Platelet–Lymphocyte Ratio, Neutrophil–Lymphocyte Ratio and Monocyte–Lymphocyte Ratio in Head and Neck Cancers: A Detailed PRISMA Compliant Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.Cancers.2021;13(16):4166. [CrossRef]

- Şahin E, Kefeli U, Zorlu Ş, Seyyar M, Ozkorkmaz Akdag M, Can Sanci P, et al.Prognostic role of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio, systemic immune-inflammation index, and pan-immune-inflammation value in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer patients who underwent 177Lu–PSMA-617.Medicine.2023;102(47). [CrossRef]

- Guan Y, Xiong H, Feng Y, Liao G, Tong T, Pang J.Revealing the prognostic landscape of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer patients treated with abiraterone or enzalutamide: a meta-analysis.Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Diseases.2020;23(2):220-31. [CrossRef]

- Templeton AJ, McNamara MG, Šeruga B, Vera-Badillo FE, Aneja P, Ocaña A, et al.Prognostic Role of Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio in Solid Tumors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute.2014;106(6). [CrossRef]

- Salciccia S, Frisenda M, Bevilacqua G, Viscuso P, Casale P, De Berardinis E, et al.Prognostic role of platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in patients with non-metastatic and metastatic prostate cancer: A meta-analysis and systematic review.Asian Journal of Urology.2024;11(2):191-207. [CrossRef]

- de Wit R, Wülfing C, Castellano D, Kramer G, Eymard JC, Sternberg CN, et al.Baseline neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a predictive and prognostic biomarker in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer treated with cabazitaxel versus abiraterone or enzalutamide in the CARD study.ESMO Open.2021;6(5):100241. [CrossRef]

- Fukuokaya W, Kimura T, Urabe F, Kimura S, Tashiro K, Tsuzuki S, et al.Blood platelet volume predicts treatment-specific outcomes of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer.International Journal of Clinical Oncology.2020;25(9):1695-703. [CrossRef]

- Wang J, Zhou X, He Y, Chen X, Liu N, Ding Z, et al.Prognostic role of platelet to lymphocyte ratio in prostate cancer: A meta-analysis.Medicine.2018;97(40):e12504. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).