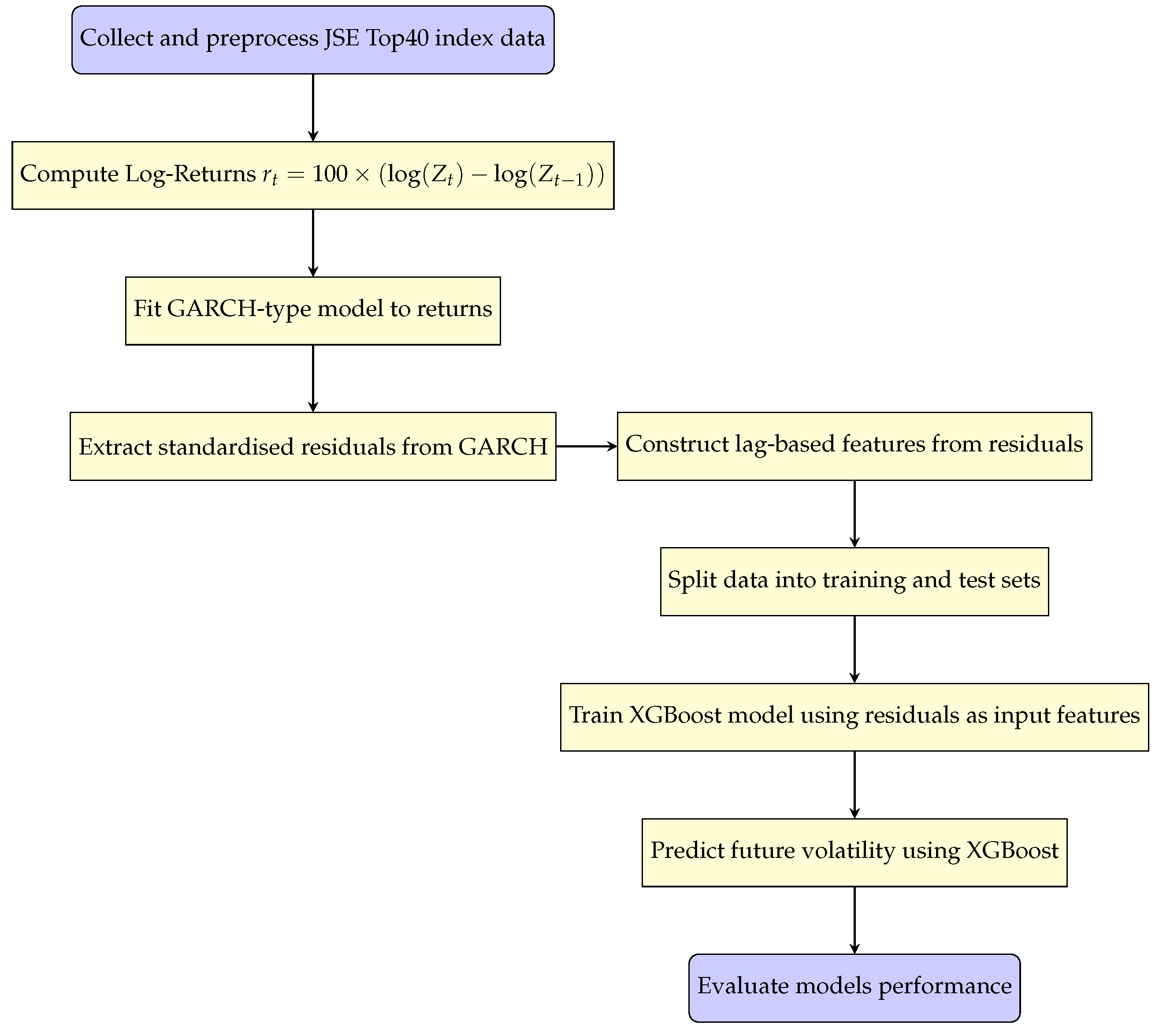

3. Empirical Results and Discussion

3.1. Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA)

3.1.1. Graphical and Statistical Diagnostics of the JSE Top40 Index and it’s Log-Returns

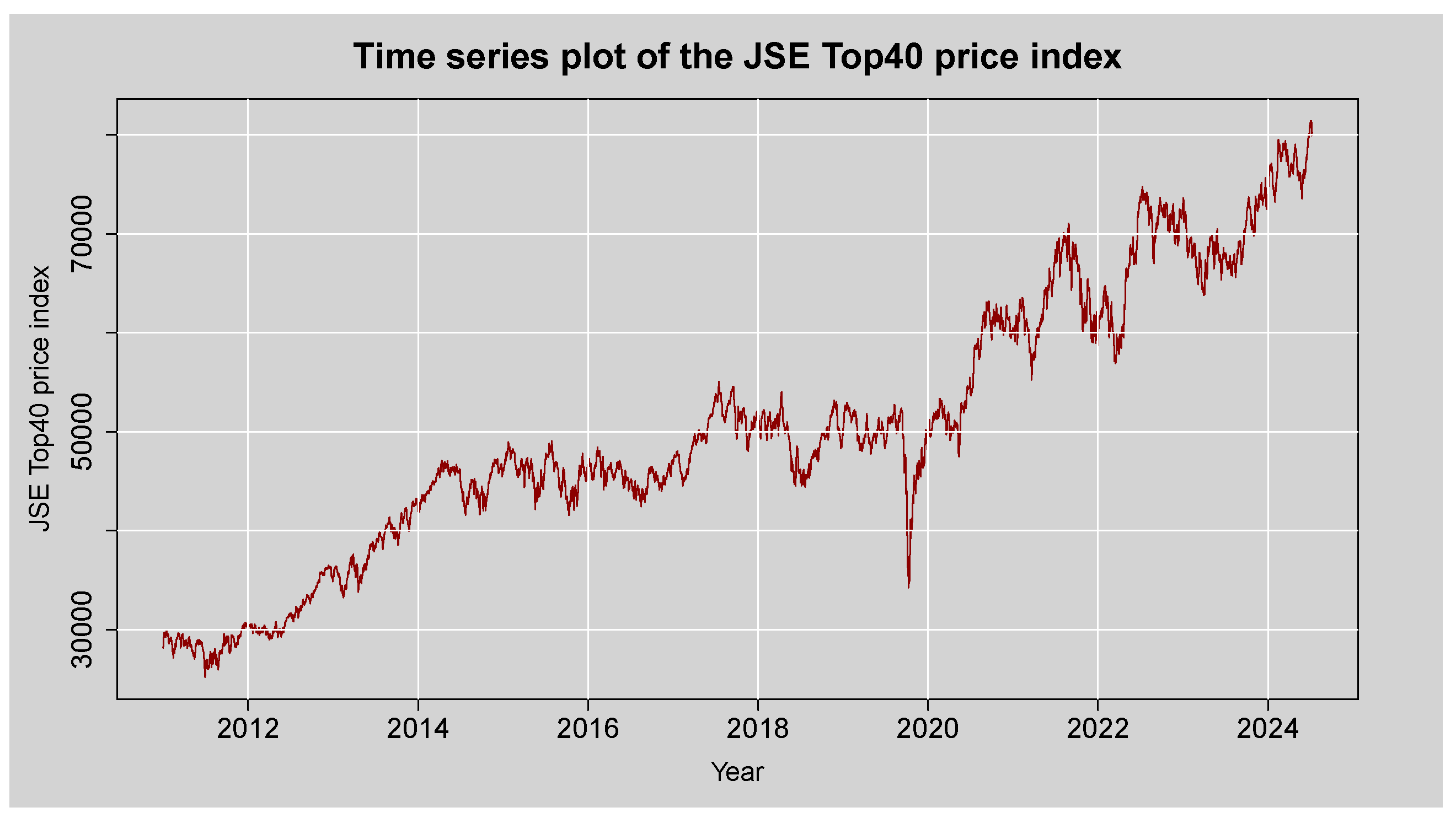

Figure 2 shows the time series plot of the JSE Top40 closing price index from the year 2011 to 2025. The plot is mainly upward-sloping, indicating a general increase in the index over the observed period. The time series plot indicates visible spikes, suggesting some level of volatility, particularly with a drastic drop in early 2020 that is likely to have been brought about by the global impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Following this downfall, the index exhibits a strong recovery and continues rising. The oscillations vary in magnitude with time, capturing different levels of volatility, a common feature of financial time series and conducive to the application of advanced volatility models such as GARCH-XGBoost and GAS. There also does not appear to be any clear-cut seasonal trend in the data, which indicates the absence of periodic recurring effects. Non-stationarity of both the mean and variance of the series indicates the need to transform it into log-returns to facilitate more robust statistical analysis and forecasting.

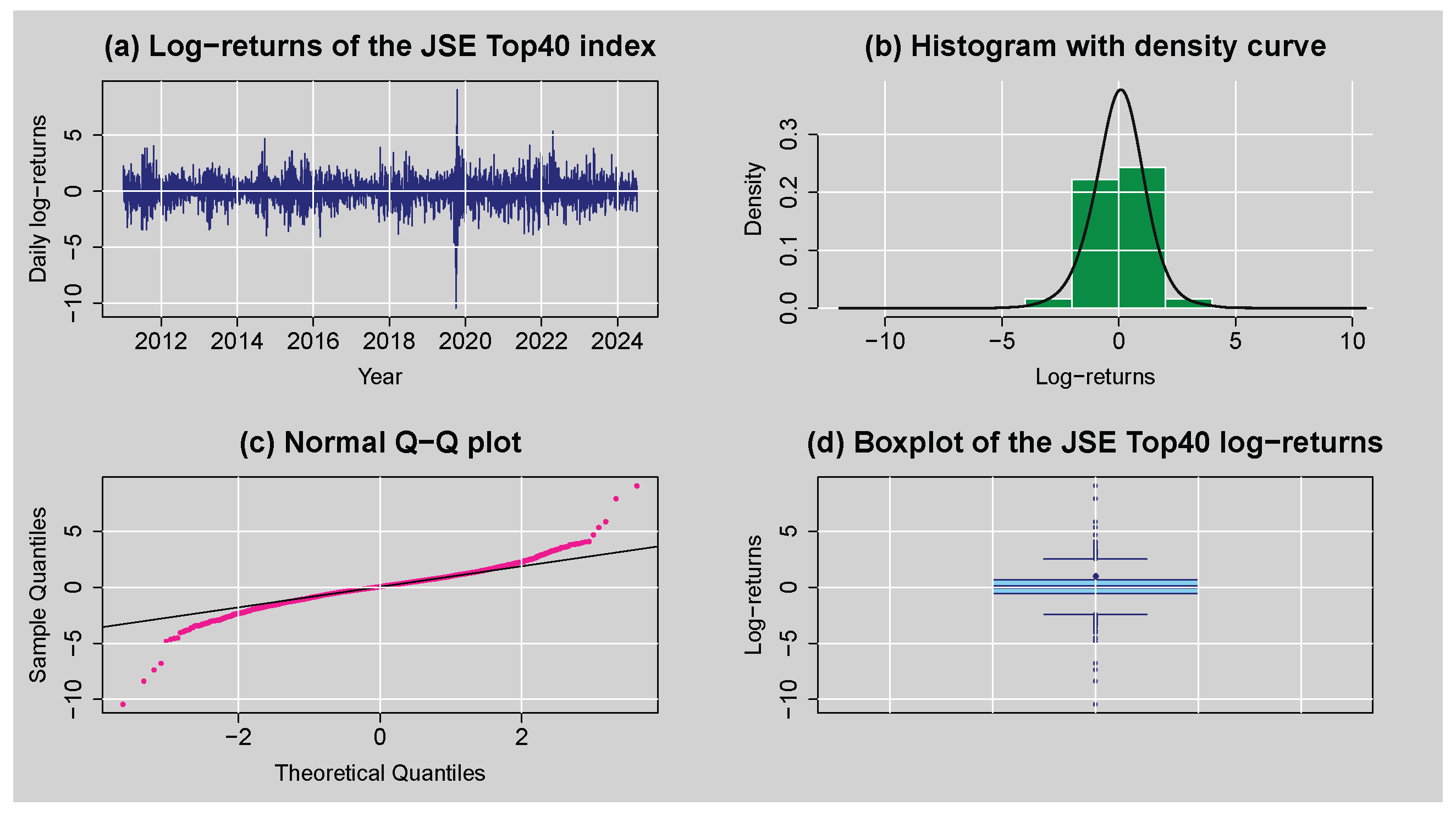

Figure 3 provides a preliminary exploration of the JSE Top40 daily log returns through various graphical techniques. Panel (

a) illustrates the time series plot of the log returns, which were obtained by first differencing the log-transformed price series to induce mean stationarity, which is a necessary condition for most time series modelling techniques. The resulting series has a zero mean and exhibits volatility clustering, where periods of high volatility tend to follow each other, implying conditional heteroskedasticity. Panel (

b), the histogram superimposed with a normal density curve, reveals that the distribution is leptokurtic and slightly negatively skewed and thus implies the presence of heavy tails and asymmetry in the behaviour of the returns. This is also confirmed by panel (

c), the Q–Q plot, with significant deviation from the diagonal line in both tails, confirming non-normality as well as excess kurtosis. Panel (

d), the boxplot, shows that values cluster around the median with a few outlier observations outside the whiskers, also confirming outliers and the fat-tailedness of the distribution. Overall, these findings suggest the presence of non-normality, volatility clustering and extreme returns.

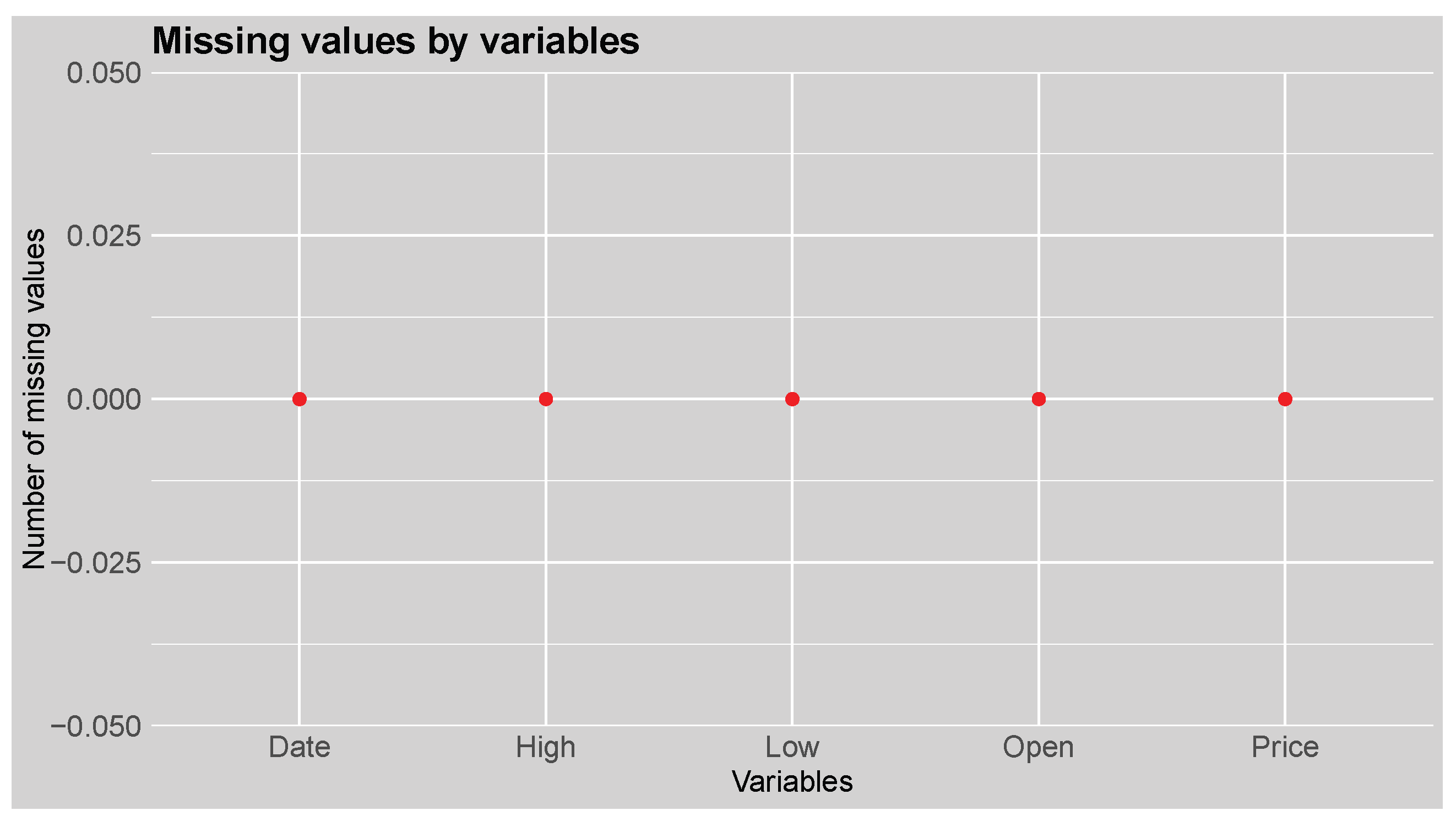

Figure 4 shows the missing value plot for each variable of the JSE Top40 index. The plot indicates that there are no missing observations in any of the variable columns. Overall, this suggests that the JSE Top40 index dataset contains no missing values.

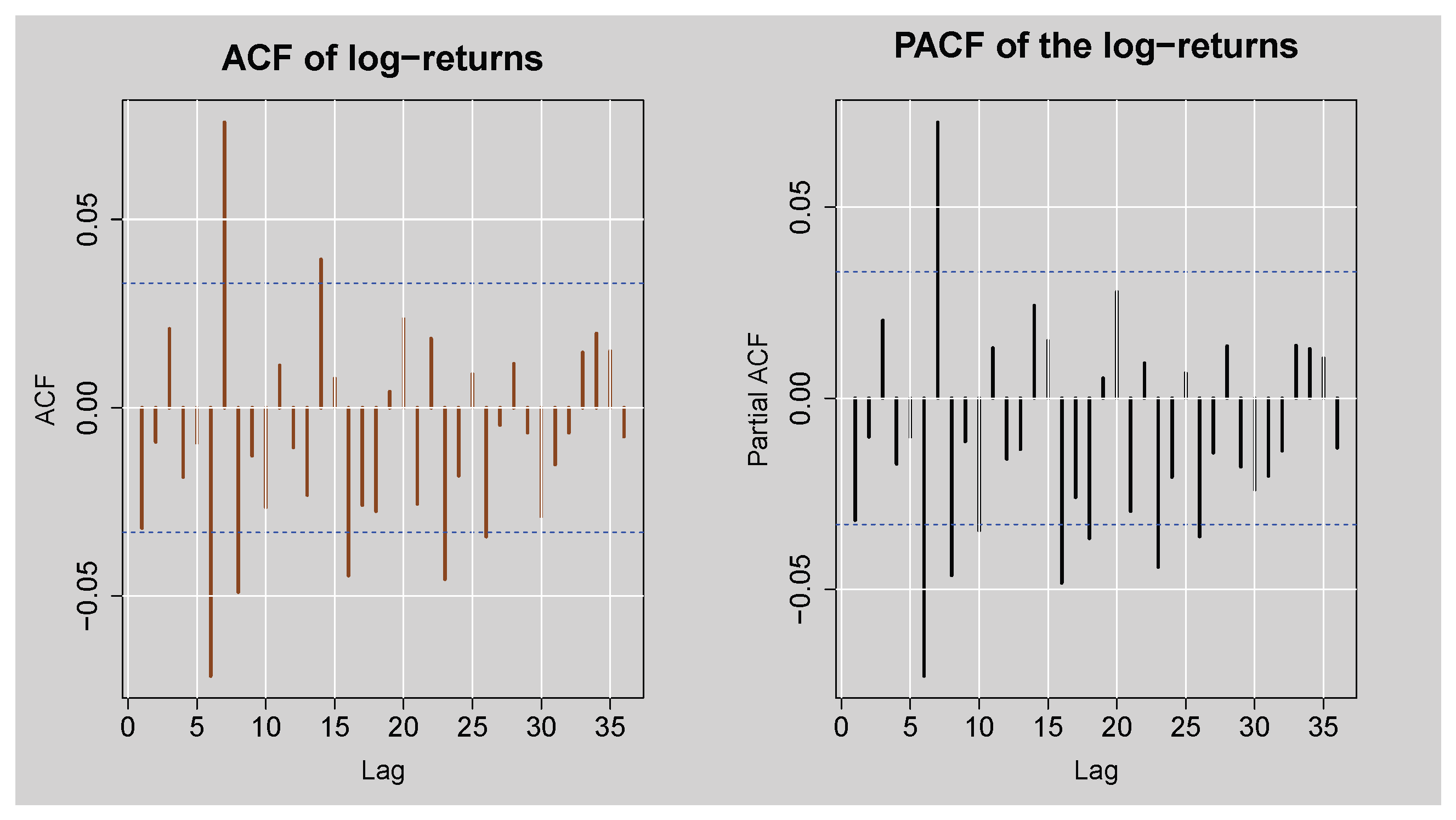

Figure 5 shows the ACF and PACF plots of the JSE Top40 Index daily log returns, providing information about the presence of autocorrelation in the log return series. The ACF plot illustrates a series of significant spikes, particularly in the early few lags, beyond the 95% confidence levels, to signify that the log returns are autocorrelated. Similarly, the PACF plot also shows high peaks at various lags, again reflecting a sign of autocorrelation present in the log return series. These visual inspections are also confirmed by the results in

Table 1 that show the Box-Ljung Q test statistics for various lag lengths. In all the lags which have been reported (

), test statistics are greater than their corresponding critical values, and the p-values are substantially below the level of 5%, and the null hypothesis of no autocorrelation is therefore rejected. Overall, these findings establish statistically significant autocorrelation in JSE Top40 log returns.

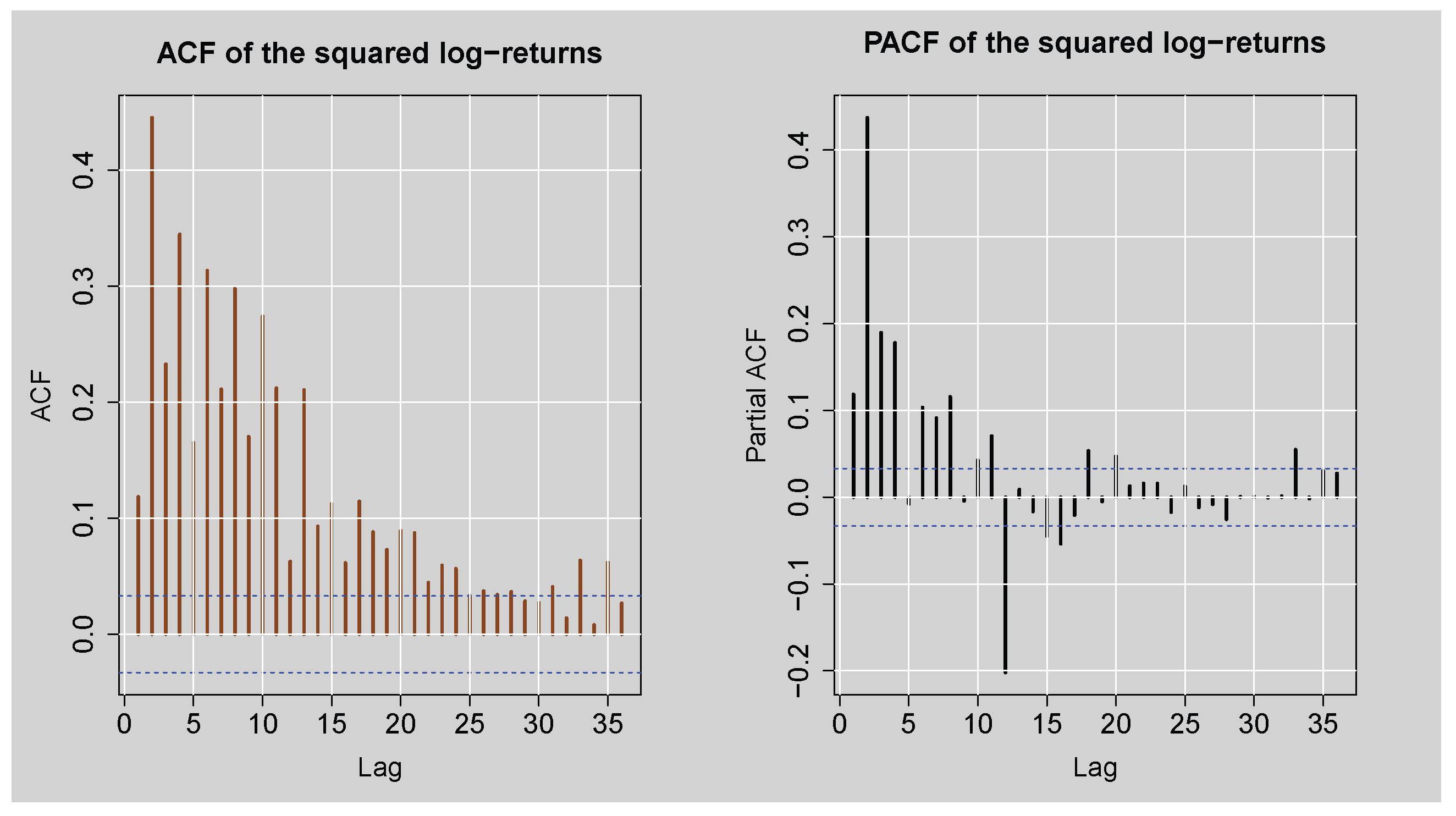

Figure 6 displays the ACF and PACF plots of the squared log returns of the JSE Top40 Index, which are used for identifying second-order dependence (autocorrelation in the variance). Both plots exhibit significant and slowly decaying autocorrelations at multiple lags, especially in the ACF plot, indicating that there is long-lasting autocorrelation in the squared log returns. This is the traditional sign of conditional heteroskedasticity, with the implication that the variance of the log returns is time-varying.

Table 2 provides formal proof of this finding through Engle’s ARCH LM test at various lag lengths. At all lags (

), the test statistics are far greater than the corresponding critical values, with p-values smaller than

, leading to a decisive rejection of the null hypothesis of no ARCH effects. These results confirm the presence of conditional heteroskedasticity in the squared log returns.

Table 3 summarises the results of stationarity and normality tests applied to the log returns. Both ADF and KPSS tests indicate that the log return series is stationary. However, the JB test strongly rejects the null hypothesis of normality (because

), implying that the log returns are not normally distributed.

Table 4 shows the descriptive statistics of the log-returns of the JSE Top40 index, which reveal significant characteristics about the nature of the log-return distribution. The mean is approximately

, indicating a slight upward trend in the average daily log-returns over the sample period. The distribution is moderately dispersed with a standard deviation (SD) of

, signifying a high level of volatility. The minimum (Min) and maximum (Max) values of

and

, respectively, suggest the presence of extreme log-return values, possibly due to market shocks or outliers. The negative skewness (Skew) coefficient of

implies that the log-return series is slightly skewed to the left, meaning that extreme negative log-returns are more dominant than extreme positive ones. Moreover, the kurtosis (Kurt) value of

exceeds the benchmark value of 3 for a normal distribution, exhibiting a leptokurtic distribution characterised by heavy tails and a higher probability of extreme log-returns. The deviation from normality in the distribution is further evidenced by the JB test in

Table 3, which confirms that the log-return series does not follow a normal distribution. These stylised features regarding the negative skew and excess kurtosis are typical of financial time series data and suggest that models accounting for asymmetry and fat tails may be more appropriate for modelling the volatility of JSE Top40 log-returns.

3.2. Selection of the ARMA(p,q) Mean Model

The mean model for the log-returns was selected by using the auto.arima() function from the forecast package in R (version 4.4.0). The function used ARMA models with Autoregressive (AR) and Moving Average (MA) of a maximum order of 10. Based on information criteria, the most suitable model was found to be ARMA(3,2) with zero mean, which implies that the mean dynamics of the series are best described by an AR(3) and MA(2) model.

3.2.1. ARMA(3,2) Mean Model Diagnostics

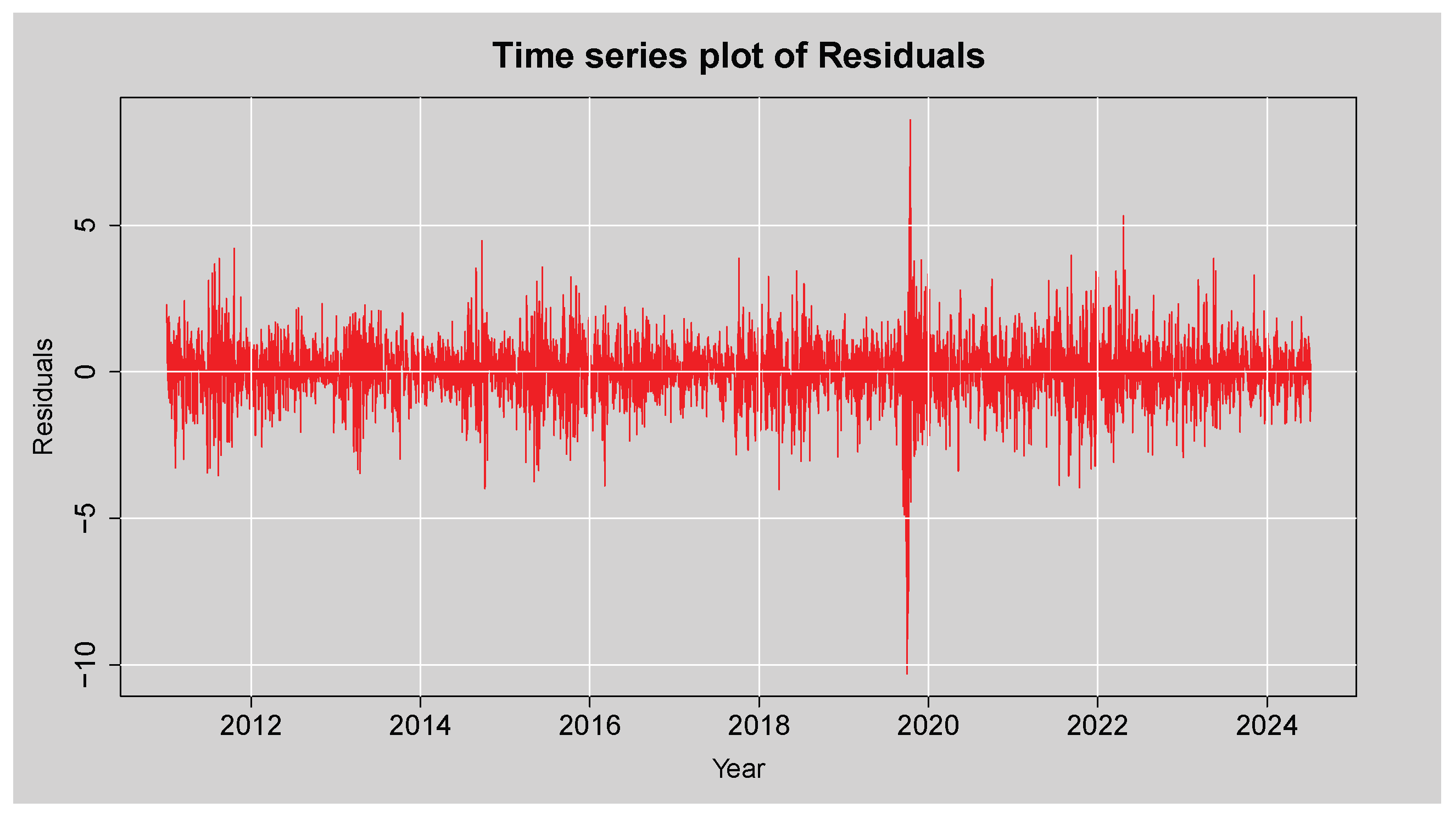

Figure 7 is a plot of the residual values after fitting the ARMA(3,2) mean model to the log returns of the JSE Top40 Index. The residuals move randomly around zero, indicating that the model has effectively removed the linear dependence trend in the mean. However, the graph shows periods of high and persistent volatility, particularly during and around 2020, which is most likely a reflection of the shocks that hit the markets during the COVID-19 pandemic. These clusters of large residuals point towards volatility clustering, which implies the residuals are not homoskedastic. This graphical evidence suggests the likely presence of conditional heteroskedasticity in the residuals.

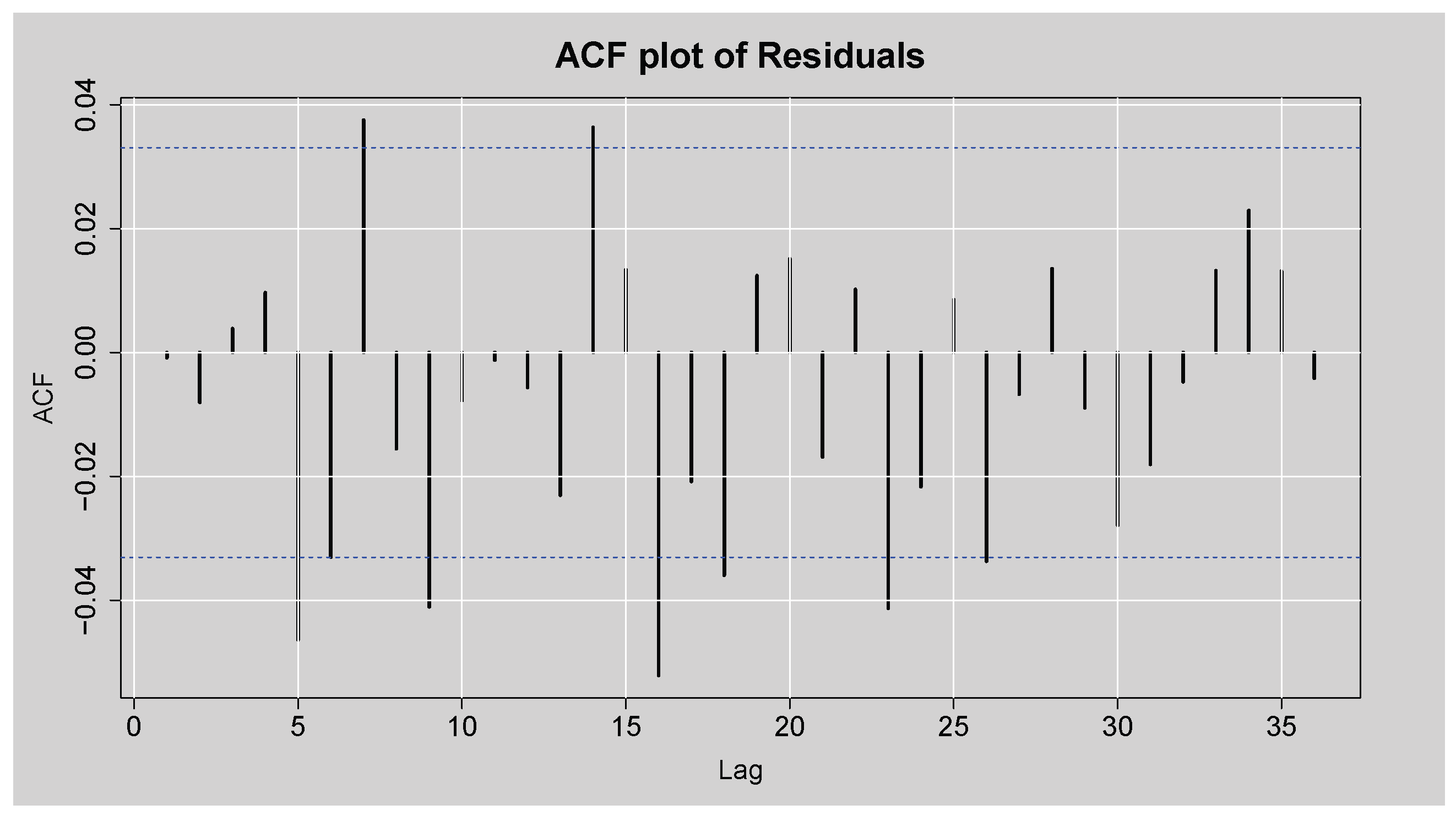

Figure 8 shows the ACF plot of the residuals of the fitted ARMA(3,2) model for the JSE Top40 log returns. While most of the autocorrelation coefficients lie within the 95% confidence bounds, there are statistically significant spikes for some of the lags, which means that not all the autocorrelation was captured in the model. This is confirmed by the Box-Ljung test results shown in

Table 5, where the null hypothesis of no autocorrelation is rejected at all lags considered (lags 10 to 30), with p-values consistently below the 5% significance level. These results indicate the presence of remaining autocorrelation in the residuals, implying that the ARMA(3,2) model does not adequately account for all linear dependencies in the return series. Furthermore, the JB test strongly rejects the null hypothesis of normality (p-value

), indicating that the residuals are not normally distributed.

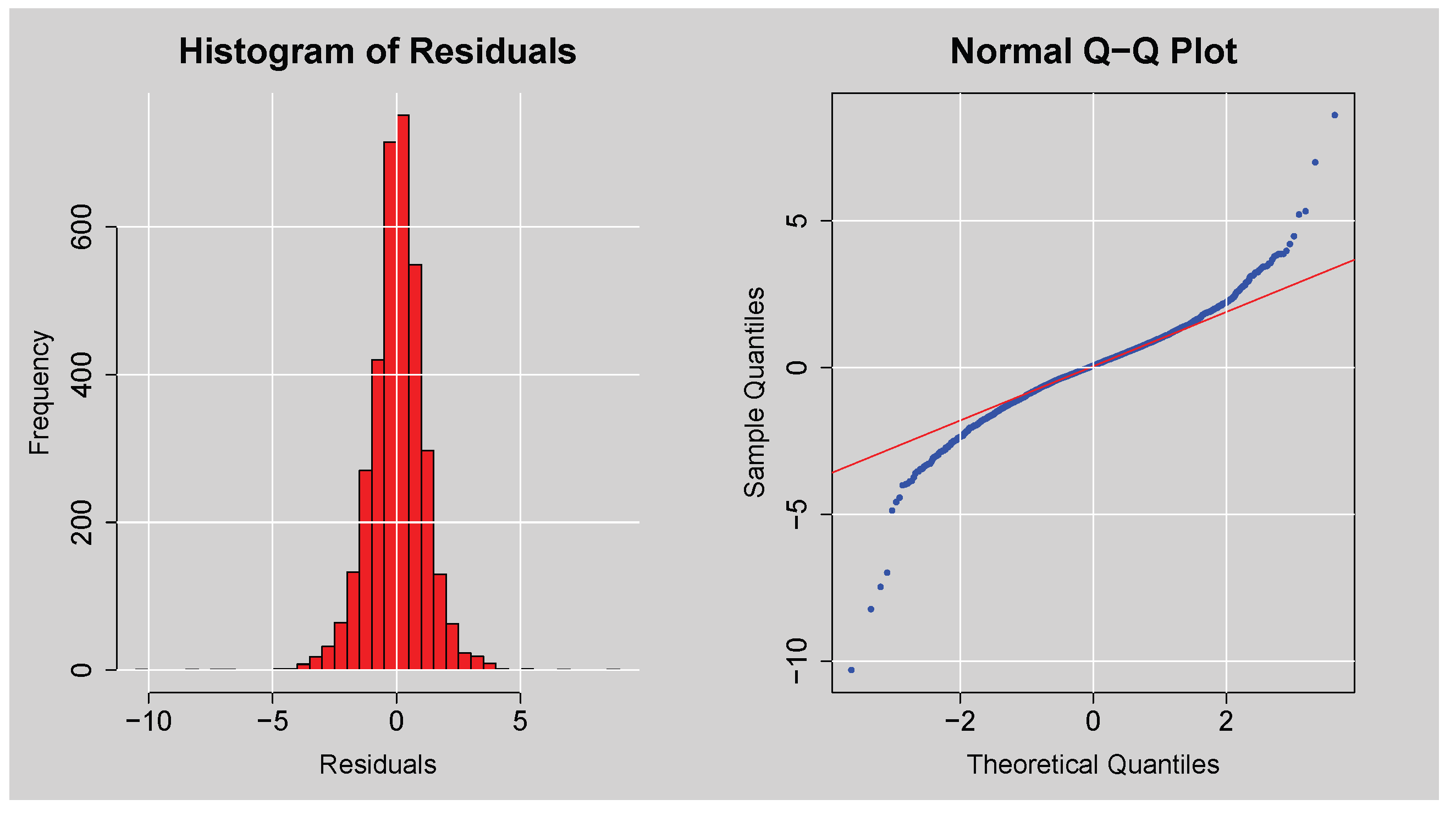

Figure 9 presents a graphical evaluation of the distributional characteristics of the residuals of the ARMA(3,2) model. The histogram (left panel) has a peak close to zero, as one would expect for residuals, but the distribution is leptokurtic (more peaked and heavier-tailed than a normal distribution), indicating non-normality. This is also supported by the Q-Q plot (right panel), in which the points deviate substantially from the 45-degree reference line, especially in the tails. These deviations indicate that the residuals are not normally distributed. This finding is in line with the foregoing JB test result. Fat tails in residuals suggest that the residuals exhibit excess kurtosis, as is common in financial time series, and suggest the potential need for conditional error distributions with heavier tails.

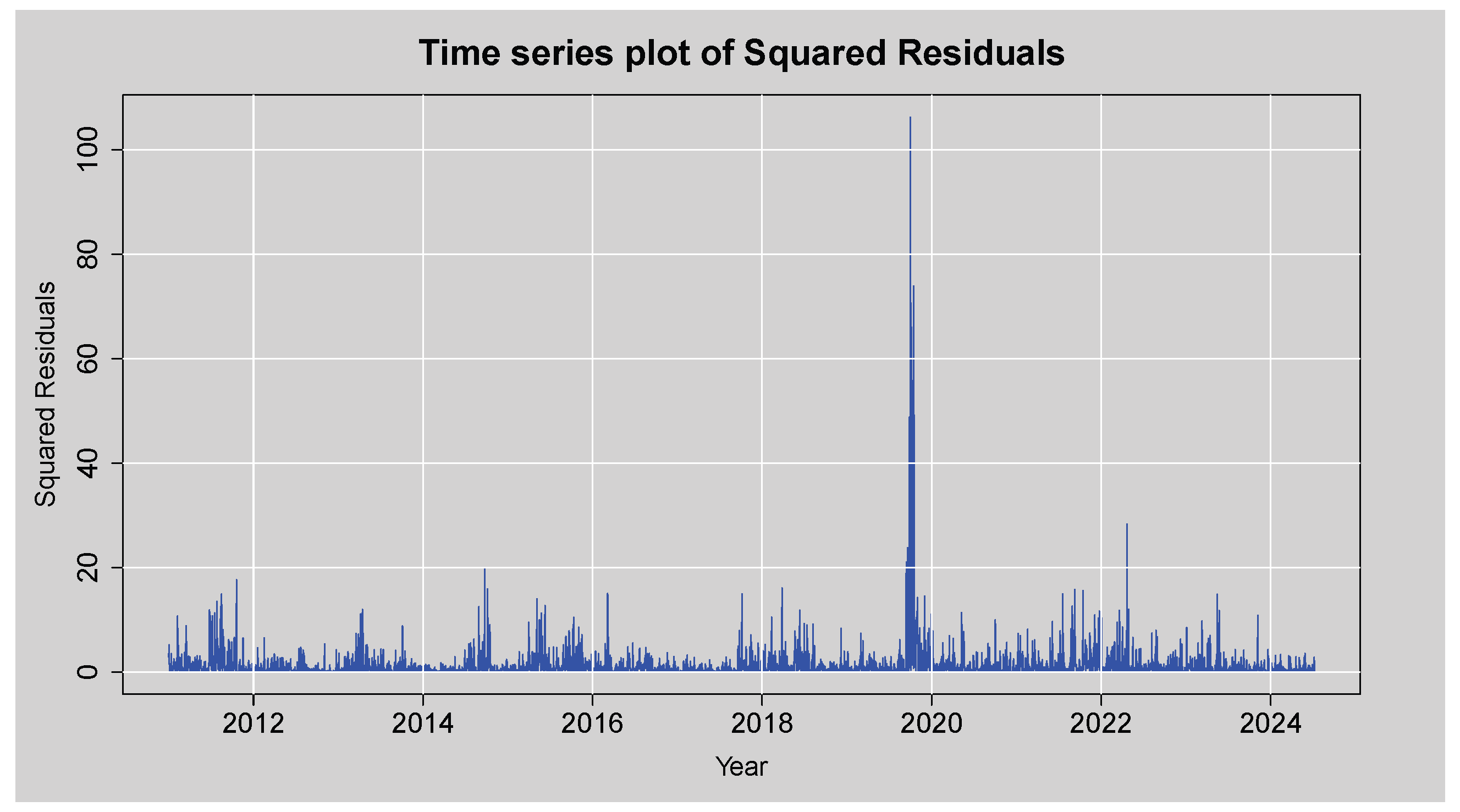

Figure 10 presents the time series plot of the squared residuals of the ARMA(3,2) model for an assessment of the variance’s behaviour over time. Most of the squared residuals are of low magnitude, while the plot contains several bursts of high volatility with a sharply peaked curve at around 2020 that is presumably driven by the COVID-19 pandemic-related financial market crisis. This clustering of large squared residuals is a clear indication of volatility clustering, a stylised fact of financial return series, and points to the presence of conditional heteroskedasticity. The visual evidence from this plot suggests that the variance is not constant over time.

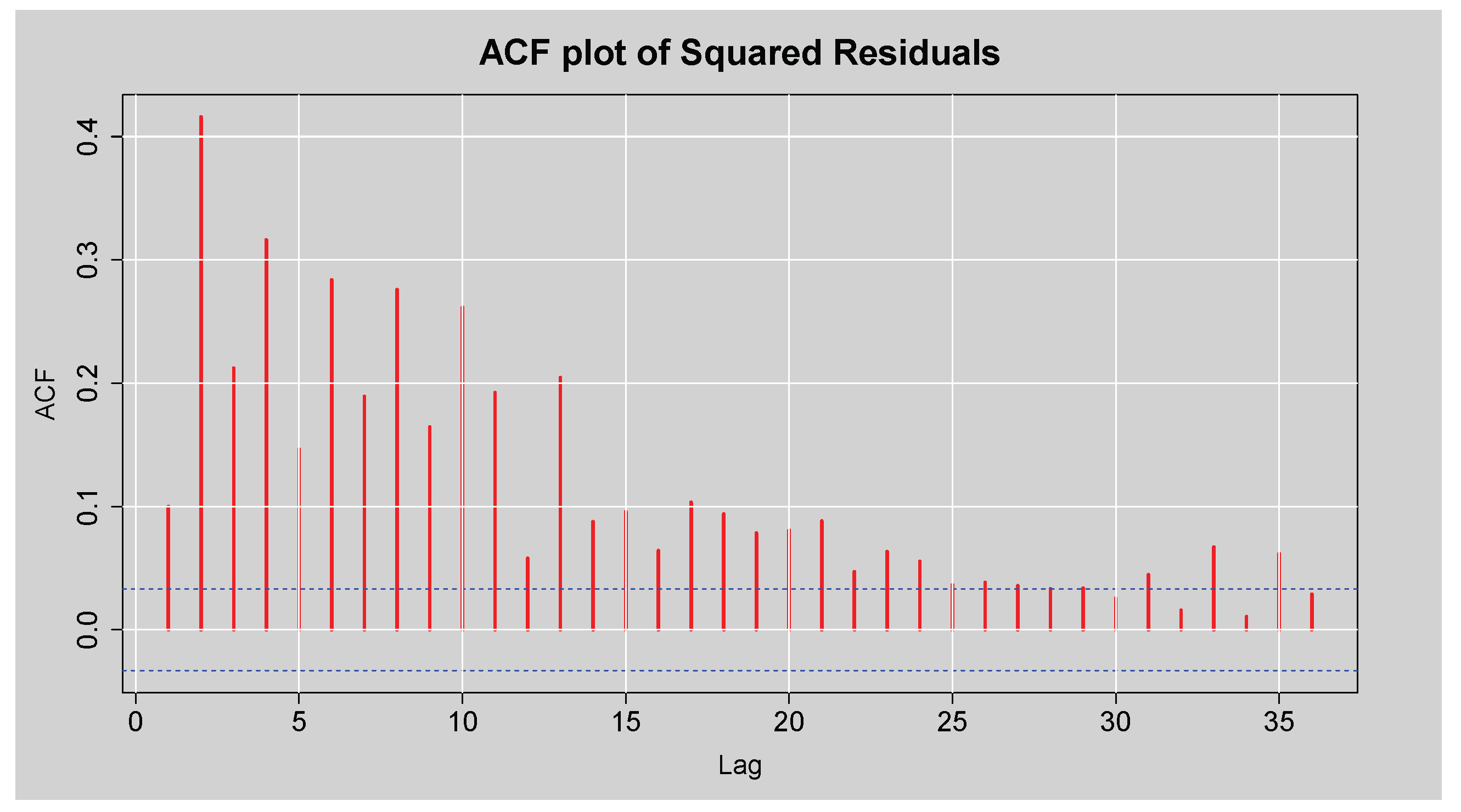

Figure 11 presents the ACF plot of the squared standardised residuals from the ARMA(3,2) model fitted to the JSE Top40 log returns. The plot shows high autocorrelation at a range of lags, and particularly at small orders, with decreases that are comparatively slow as the lag increases. This persistent autocorrelation structure of the squared standardised residuals is very strong and indicates that there is time-varying volatility, i.e., residual variance is time-varying and depends on prior squared values. These findings are statistically confirmed by the results of Engle’s ARCH LM test in

Table 6, which reports extremely large test statistics and p-values less than

at all considered lags. This leads to a decisive rejection of the null hypothesis of no ARCH effects, indicating the presence of conditional heteroskedasticity in the residuals. Furthermore,

Table 7 displays the results of the Box-Ljung test on the squared standardised residuals, with all p-values also being less than

, which suggests the presence of conditional heteroskedasticity; that is, the variance of the residuals is serially correlated and changes over time.

3.3. Fitting of ARMA(3,2)-GARCH-type Models

Table 8 provides a comparison of ARMA(3,2)–GARCH-type models fitted under different conditional error distributions: STD, SSTD, GED, SGED, and GHD. The evaluation criteria used are the AIC, BIC, HQIC, and LL. Among all specifications, the ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1) model under the SSTD exhibits the lowest values for AIC, BIC, and HQIC and the highest LL value. These results suggest that ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1) with SSTD is the optimal model and provides the best in-sample fit compared to the sGARCH and GJR-GARCH variants under the same distributional error assumptions.

3.3.1. ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1) Model Diagnostics

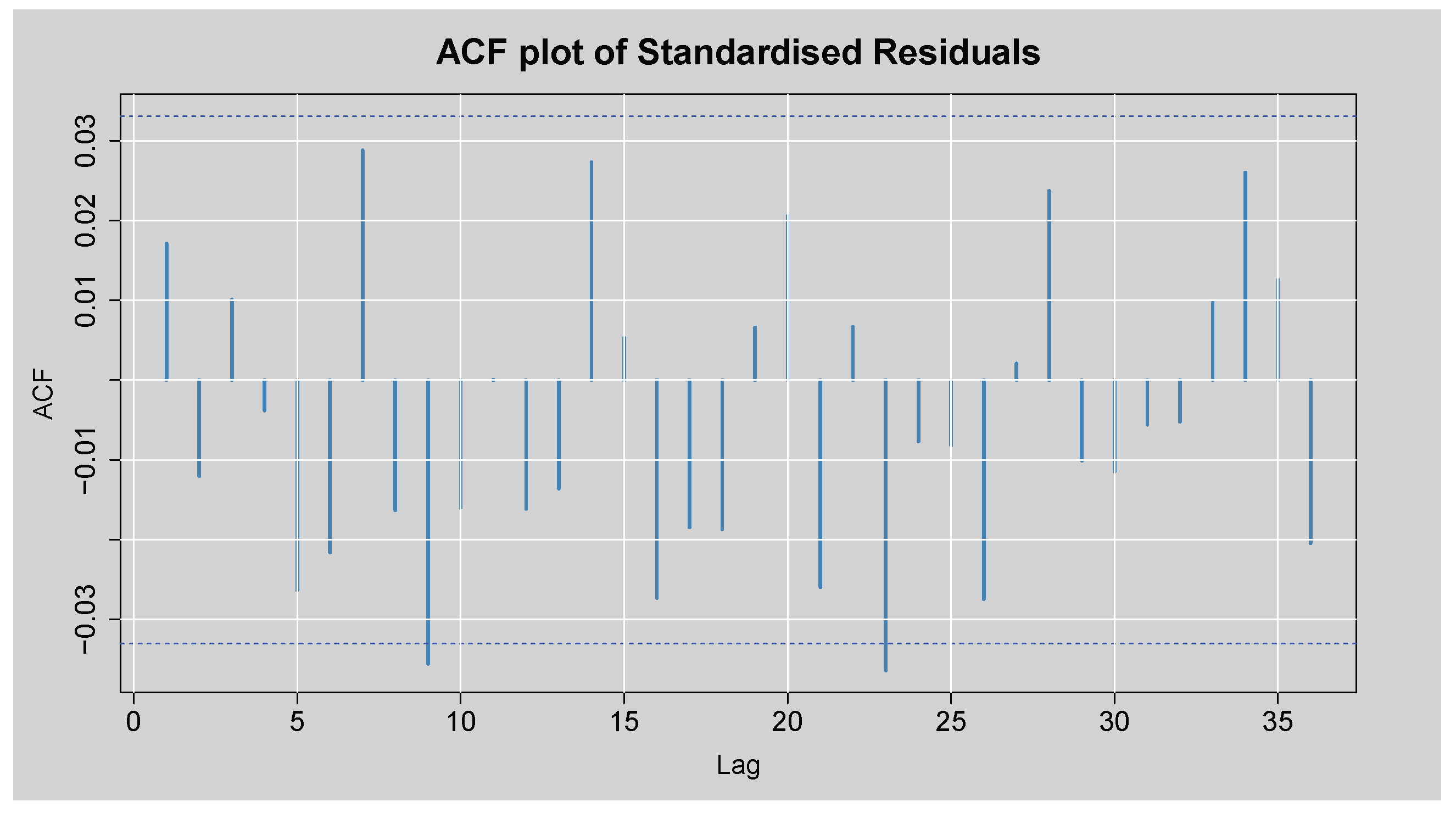

Figure 12 displays the ACF plot of the standardised residuals obtained from the ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1) model. Most autocorrelation coefficients lie within the 95% confidence bounds, with only a few marginally exceeding the limits. This visual evidence indicates that the model has captured the linear dependence structure adequately, as little to no residual autocorrelation remains. This is also supported by the Box-Ljung test of the standardised residuals presented in

Table 9. p = 0.309 at lag 1, which is well above the 5% level of significance, and consequently, there is no statistically significant autocorrelation at lag 1. Although lag 14 has p = 0.00087, reflecting residual autocorrelation, the value of p for lag 24 is 0.069, which is only marginally more than the 5% level. Overall, these results confirm that the ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1) model has indeed eliminated much of the autocorrelation from the residuals, with the residuals that are left being nearly white noise.

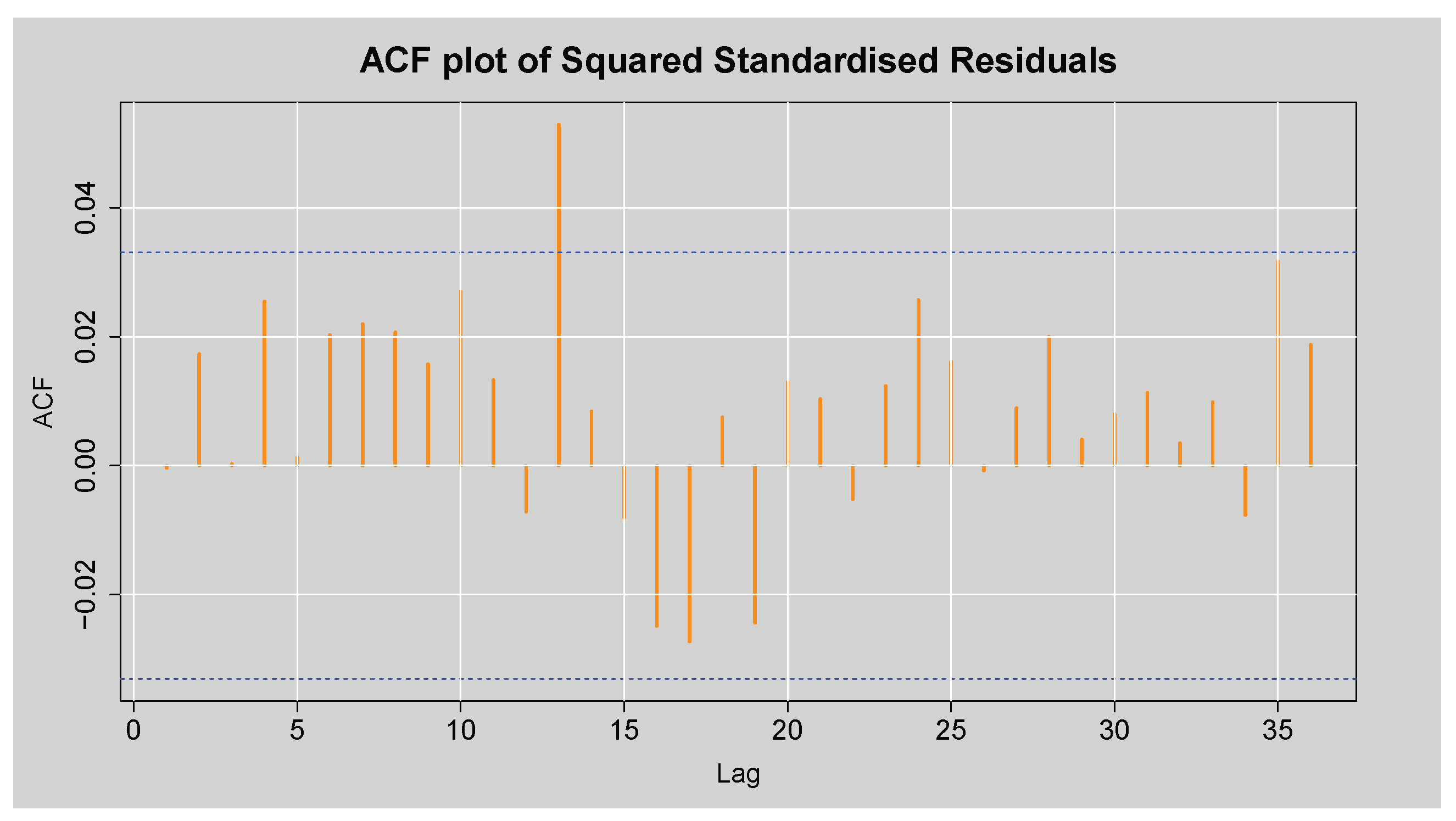

Figure 13 shows the ACF plot of the squared standardised residuals of the ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1) model. There is little significant autocorrelation evident, as most of the spikes are inside the 95% confidence limits, and a couple of small lags reach the boundary. This visual outcome suggests that the conditional heteroskedasticity has been adequately captured by the ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1) model, leaving little to no remaining structure in the squared standardised residuals. This observation is reinforced by the results of Engle’s ARCH LM test shown in

Table 10, where all p-values at lags 3, 5, and 7 are substantially greater than 0.05. Hence, we fail to reject the null hypothesis of no ARCH effects, confirming the absence of remaining conditional heteroskedasticity in the squared standardised residuals. Similarly,

Table 11 presents the Box-Ljung test statistics on the squared standardised residuals, which also yield non-significant p-values across all reported lags. This validates the finding that the model has eliminated any remaining conditional heteroskedasticity in the squared standardised residuals. Overall, these results show that the ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1) model is a good fit for modelling both the average and the ups and downs of the JSE Top40 log returns.

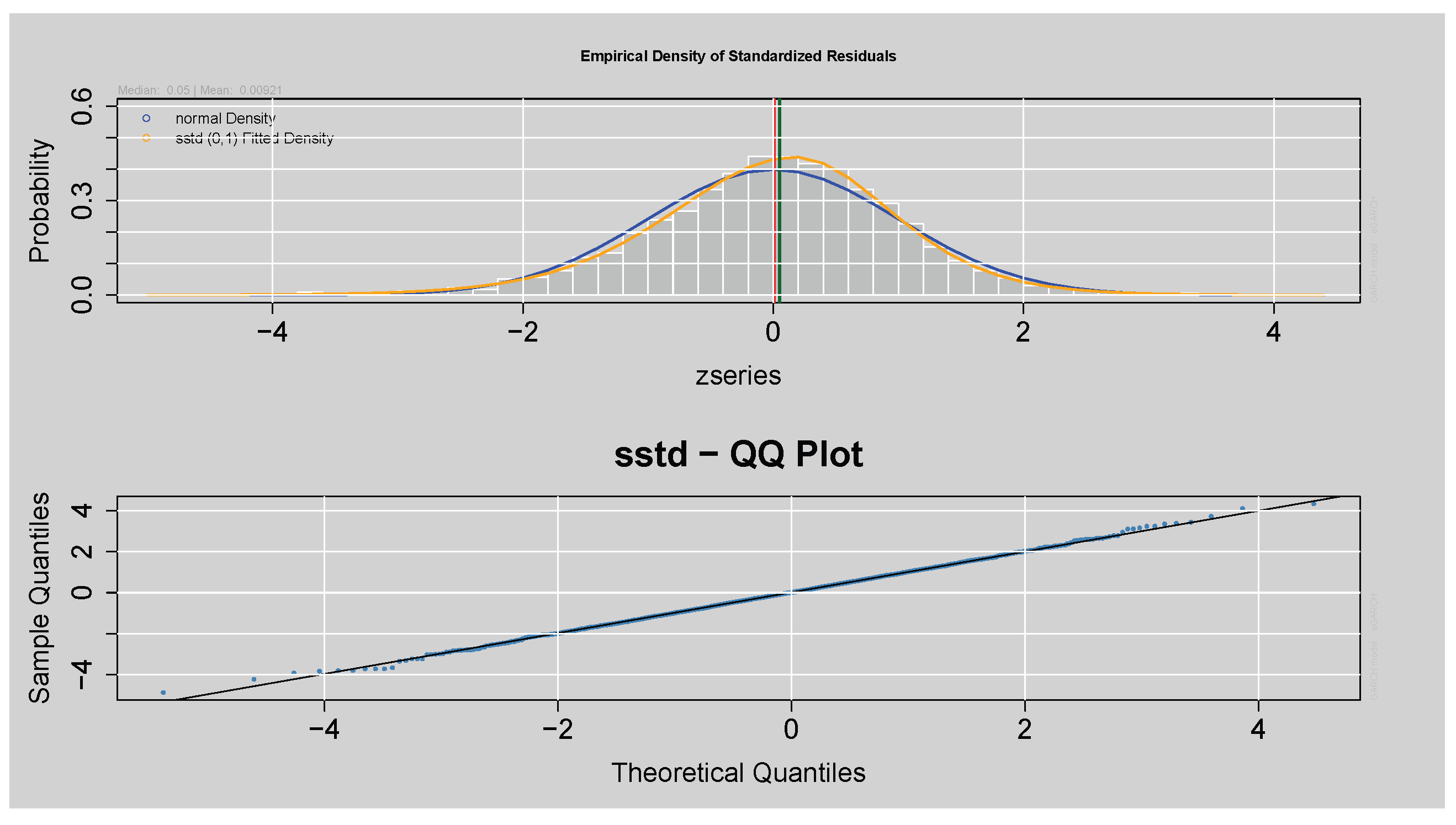

The top panel in

Figure 14 shows that the fitted model’s standardised residuals closely follow the fitted SSTD with fatter tails than the normal density. The lower Q-Q plot confirms this by showing that most points are along the 45-degree line, suggesting a good fit, although the slight deviation of the tails suggests some residual non-normality. Overall, the residuals exhibit a distribution with the assumed SSTD.

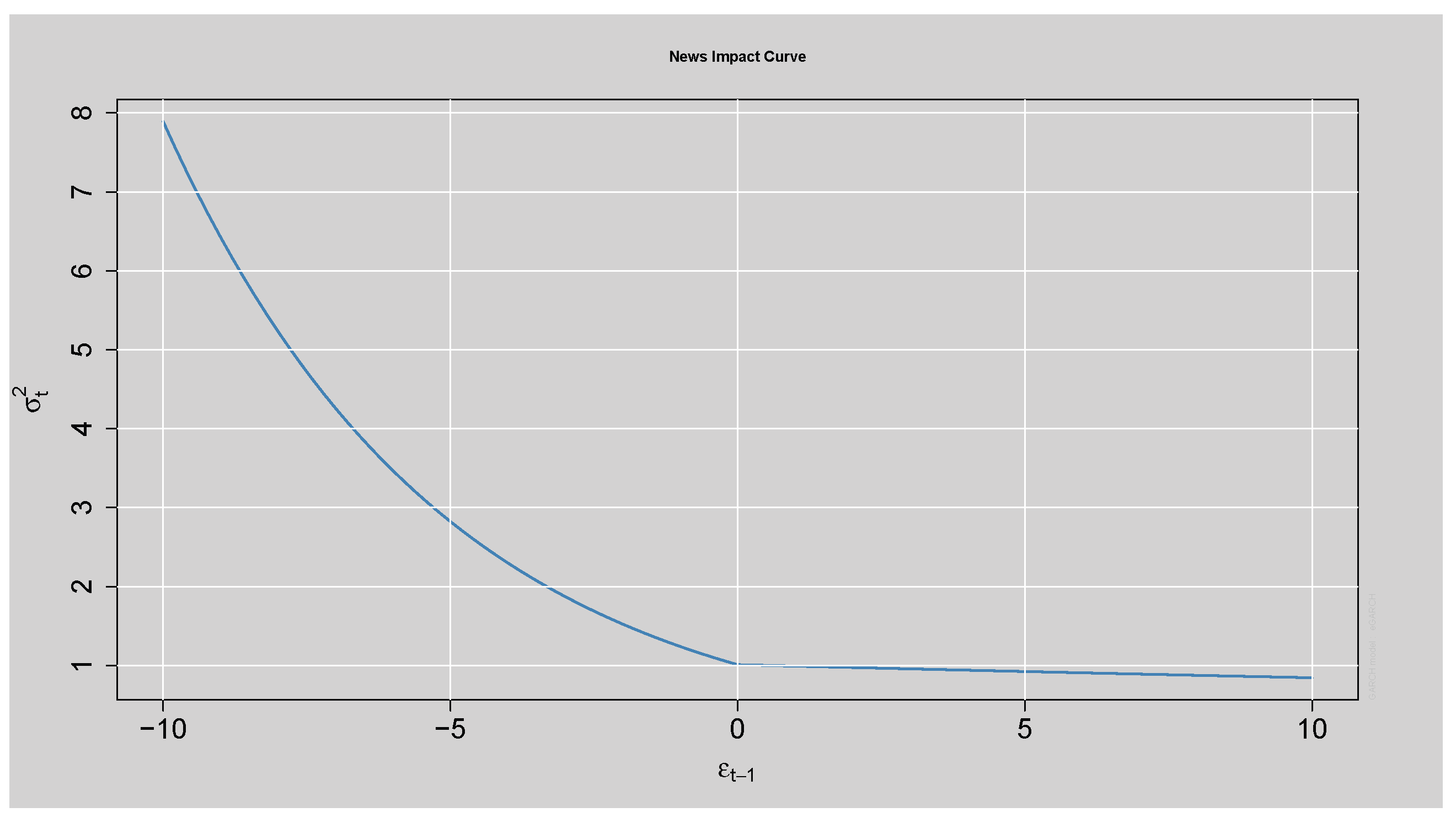

The News Impact Curve in

Figure 15 shows that negative shocks have a greater effect on future volatility than positive shocks of the same magnitude, indicating strong asymmetry. This confirms that the fitted ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1) model captures the leverage effect present in the data.

The findings in

Table 12: Sign Bias Test reveal that the individual terms of sign bias (negative or positive sign) are not statistically significant since their respective p-values are above 0.05. However, the joint effect has a p-value greater than the 5% threshold, providing evidence for asymmetry. These results also align with

Figure 15: News Impact Curve, where it is clear that the negative shocks have more influence on volatility than positive shocks.

The mean

parameter and the constant term

in the variance equation shown in

Table 13 are statistically insignificant, as indicated by their p-values greater than

, suggesting they do not have a meaningful impact on the model. However, the parameters

and

are highly significant with p-values

, implying that past shocks and past volatility significantly influence current volatility. The model exhibits strong persistence in volatility, as shown by the high value of

, indicating that volatility clusters persist over time. Moreover, the positive and significant leverage term

suggests evidence of asymmetry, meaning that negative shocks tend to increase volatility more than positive shocks of the same magnitude. This is also demonstrated by the News Impact Curve shown in

Figure 15.

3.4. Fitting the hybrid ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1)-XGBoost Model (Two-Step Approach)

In this section, a two-step approach modelling framework was employed to enhance the forecasting performance and quantify uncertainty in the standardised residual time series. The approach began with fitting an ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1) model to the daily log returns of the JSE Top40 Index. The autocorrelation linear structure, conditional heteroskedasticity and asymmetry were captured by the ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1). The rugarch package from R (version 4.4.0) estimated the model under an SSTD for innovations to accommodate both skewness and heaviness in tails. Once the optimal ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1) model was fitted, the standardised residuals were extracted for further analysis. In the second step, the standardised residuals were modelled using the XGBoost algorithm. This ML method was selected due to its high flexibility in capturing nonlinear patterns and interactions that traditional time series models might overlook. To prepare standardised residuals for XGBoost, a set of lag features (lags 1 to 15) and rolling window statistics (means and standard deviations over window sizes 2, 3, 5, 10, and 20) were generated using data.table and zoo packages in R (version 4.4.0). These features were designed to reflect temporal dependencies and local volatility structure in the standardised residuals.

The prepared data was also split into three sets: 60% for model training, 20% for calibration (for the construction of prediction intervals), and 20% for out-of-sample testing. The XGBoost model was trained on the squared error loss function with a five-fold cross-validation to determine the optimal number of boosting rounds. Hyperparameters were a 0.05 learning rate, an optimal depth of 4, and a subsample ratio of 0.8 to prevent overfitting. Predictions were made on the test and calibration sets after training.To measure how uncertain the forecast is, we used the differences between what we predicted and what actually happened in the calibration set to create 90% prediction intervals. Specifically, the 95th and 5th percentiles of the obtained residuals were used to add to the test set point predictions in order to find the lower and upper bounds of the prediction interval, respectively. For this purpose, the algorithm mimics the conformal prediction principles, wherein the prediction intervals are obtained from the residual distribution over a calibration set, with finite-sample coverage guarantees without strong assumptions on the residual’s distribution. The 90% prediction intervals were complemented by the inclusion of 95% and 99% prediction intervals constructed from the 97.5th/2.5th and 99.5th/0.5th percentiles of calibration residuals. This approach provided a useful way of constructing data-driven nonparametric intervals capturing model uncertainty without strong distributional assumptions. Overall, the two-step approach allowed the power of classical time series modelling (via ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1)) to be merged with the potential of ML (via XGBoost) to produce accurate point forecasts as well as useful prediction intervals for the standardised residual series.

3.4.1. Forecast Performance Evaluation of Residual-Adjusted Forecasts from hybrid ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1)-XGBoost Model

Table 14 presents the first ten forecast results obtained from the hybrid model. Each row shows the actual standardised residual and the corresponding point prediction from the model. The table demonstrates that the forecast values are generally close to the actual standardised residuals, indicating that the model performs well in approximating future values. This supports the model’s accuracy in point forecasting and highlights its potential effectiveness in capturing the underlying dynamics of the residuals.

Table 15 shows the forecast accuracy measures of the hybrid ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1)-XGBoost model fitted using a two-step approach. The hybrid ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1)-XGBoost model was validated using some measures of the accuracy of forecasts on the test sample of the standardised residuals. MASE is 0.0534 and RMSE is 0.1386, indicating a reasonably low value of the error in the prediction of the model. MAE is 0.0595, suggesting that, on average, the predictions of the model are about 0.06 units away from the actual standardised residuals. MAPE is 27.93%, and sMAPE is 16.41%. These values show moderate relative accuracy of the forecast, and sMAPE is a more accurate and symmetric performance measure of percentage errors that is suited for standardised residuals in which values can be positive as well as negative.

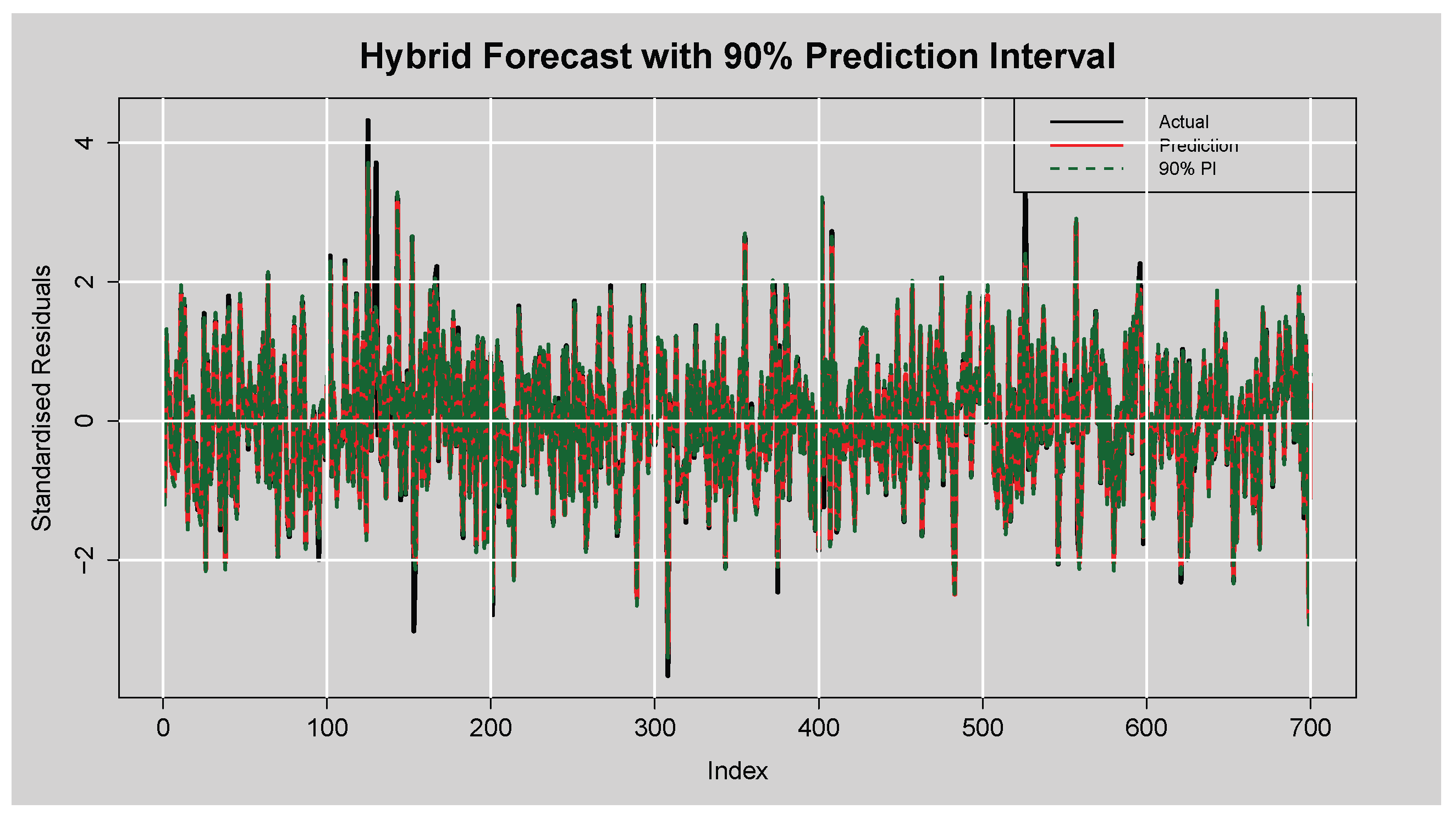

Figure 16 displays the forecast performance of the hybrid ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1)-XGBoost model on the test set of standardised residuals, along with its corresponding

prediction intervals. The actual standardised residuals are plotted in black, while the red line represents the point forecasts generated by the XGBoost component. The shaded region between the dotted green lines is the lower and upper bounds of the

empirical prediction intervals constructed based on the calibration residuals. From the

Figure 16, there is clear evidence that the hybrid model was tracking the dynamics of the residual series well. The modelled series follows the rise and fall of the actual standardised residuals, including at the points of sharp peaks and troughs. The presence of several extreme spikes, particularly between indices

and at index 600, were generally well-bound within the range of the interval, indicating the model’s ability to respond to abrupt volatility.

Furthermore, the vast majority of actual values lie within the prediction intervals, visually supporting the previously reported empirical coverage rate, which exceeds the nominal level. This suggests that the constructed intervals are not only reliable but slightly conservative (an often preferred trait in financial forecasting), where underestimation of uncertainty can have costly implications. Additionally, the temporal average width is fairly consistent with the reported average width of , demonstrating reliable quantification of uncertainty without inflated spread. Altogether, the plot attests to the numerical performance measures and confirms that the hybrid model is precise in point forecasting as well as data-efficient in deriving forecast uncertainty from prediction intervals.

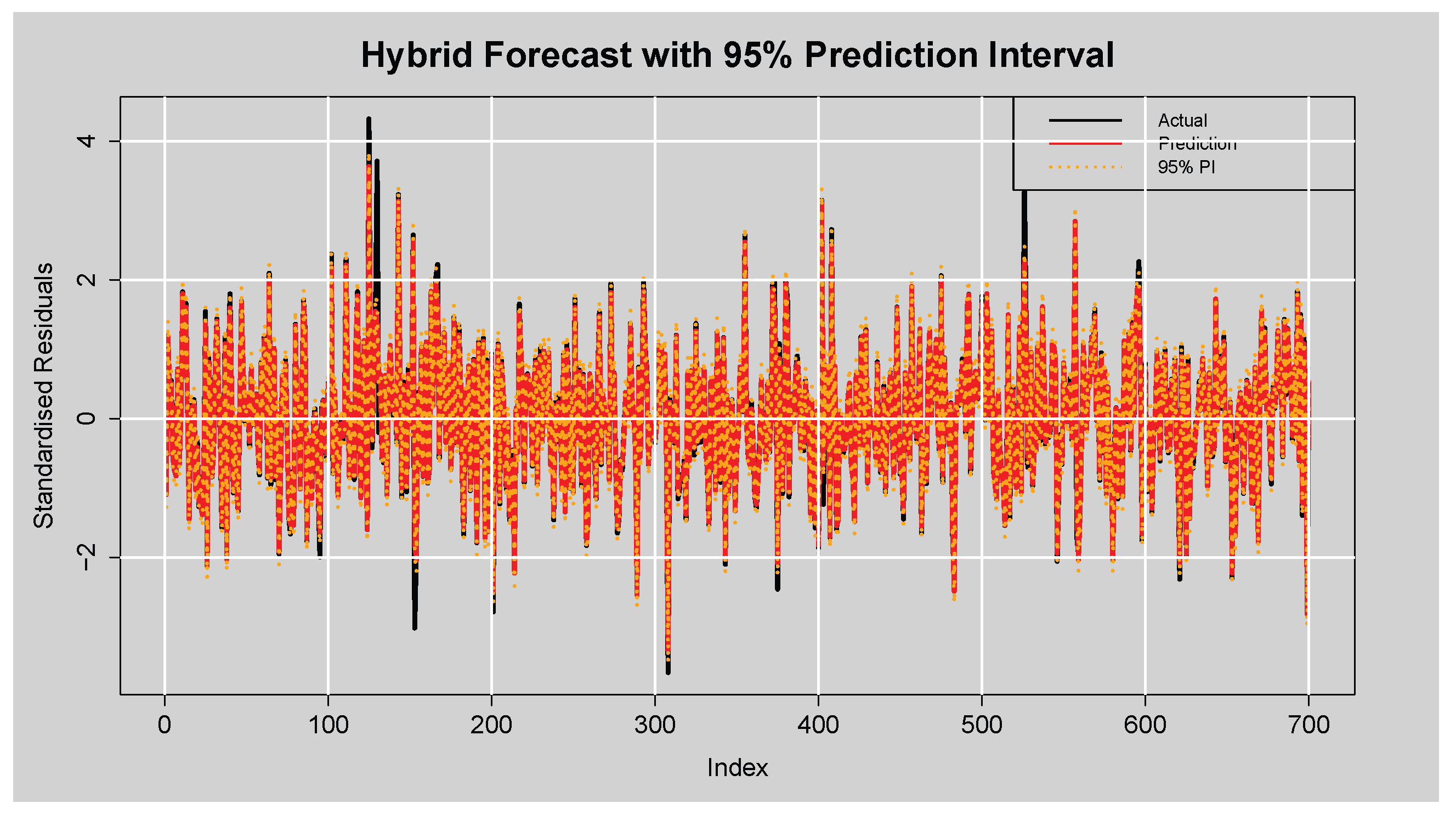

Figure 17 shows that the hybrid model’s

prediction intervals effectively capture the uncertainties in forecasts, with

of the actual standardised residuals falling within the interval. This indicates slightly conservative, yet reliable, prediction intervals. The average interval width of

reflects a reasonable balance between precision and coverage, confirming the model’s strong calibration and forecasting performance.

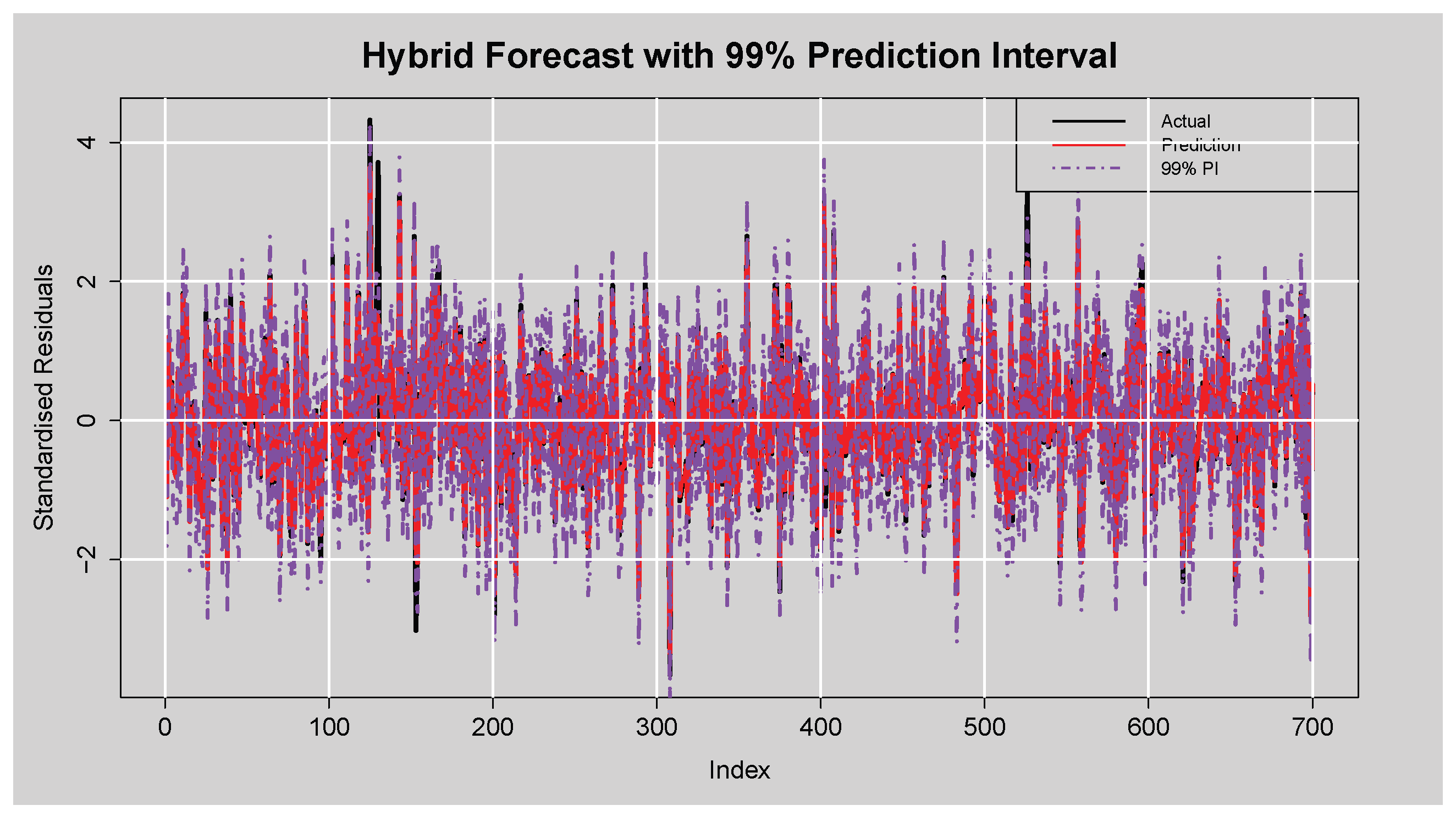

Figure 18 provides a demonstration of the robustness of the hybrid model’s

prediction interval with an empirical coverage rate of

. This indicates that nearly all actual standardised residuals fall inside the interval, a remarkable quantification of uncertainty. The average interval width of

, while wider than for lower levels, is to be expected and acceptable for so high a confidence level. This wider band enhances the reliability of coverage and makes the model particularly well-suited for risk-attentive forecasting scenarios.

The results of the prediction interval test in

Table 16 indicate that the coverage probabilities (PICP) of the 90%, 95%, and 99% intervals are 94.0000%, 97.1429%, and 99.2857%, respectively. These results suggest that the prediction intervals are well-calibrated since they closely estimate or slightly exceed their nominal confidence levels. The normalised average interval widths (PINAD) for the 90%, 95%, and 99% intervals are 0.7939%, 0.7984%, and 0.8130%, respectively, reflecting growing interval width with increased confidence levels. Moreover, both the average interval widths (PINAW) and their scaled values (PICAW) increase with higher confidence levels due to the inherent trade-off between interval sharpness and coverage. Generally, the results indicate that the model is able to produce reliable and informative prediction intervals across all confidence levels.

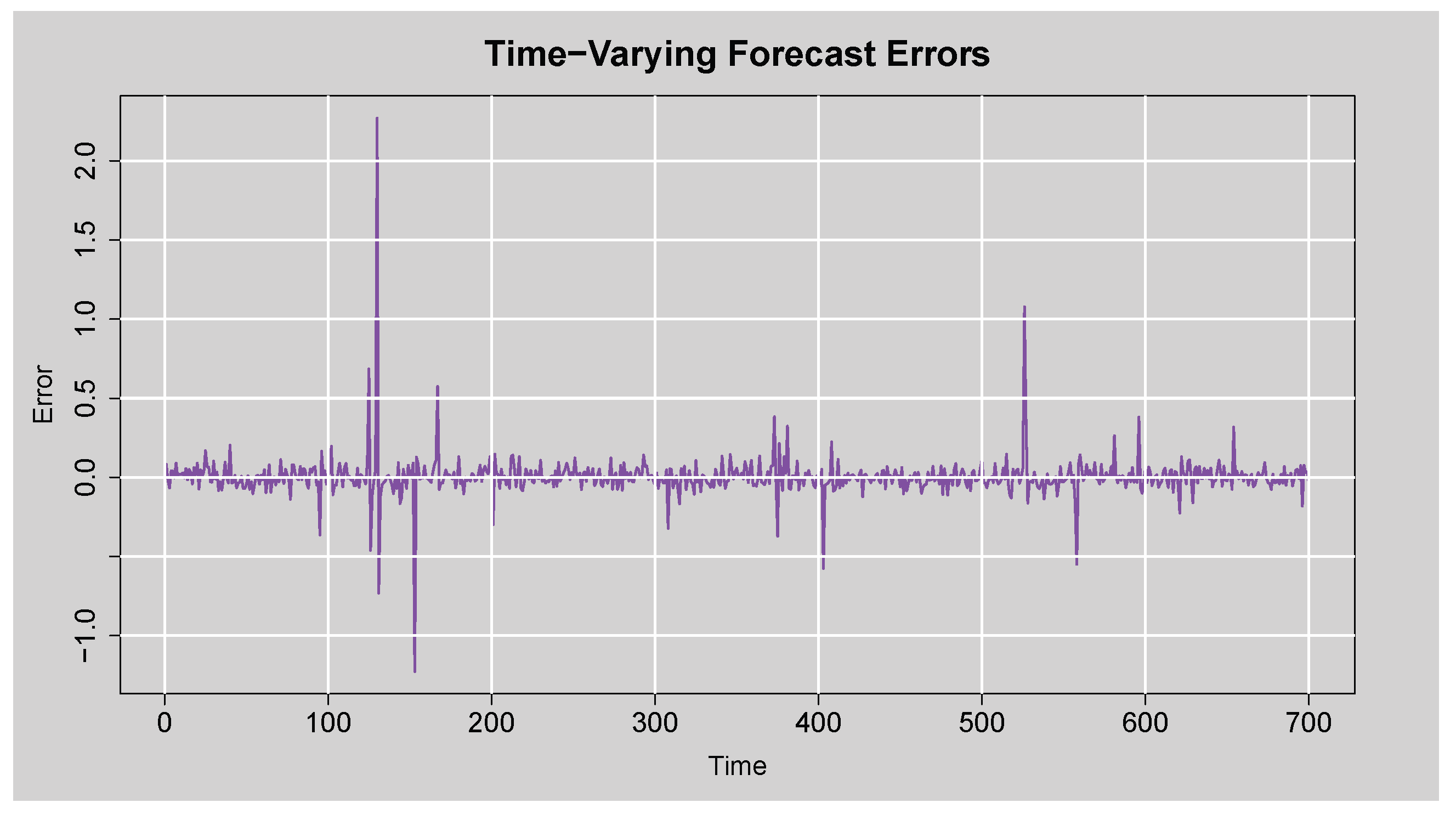

The time-varying forecast errors plot in

Figure 19 indicates the difference between actual and predicted standardised residuals over time. Most errors are around zero, suggesting consistent and unbiased forecasts. There are a few large spikes representing occasional larger forecast deviations, but they are infrequent and not systematic. This reaffirms the model’s ability to generate stable forecasts with occasional outliers, possibly due to unexpected volatility shocks.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.M., T.R. and C.S.; methodology, I.M.; software, I.M.; validation, I.M., T.R. and C.S.; formal analysis, I.M.; investigation, I.M., T.R. and C.S.; data curation, I.M.; writing—original draft preparation, I.M.; writing—review and editing, I.M., T.R. and C.S.; visualization, I.M.; supervision, T.R. and C.S.; project administration, T.R. and C.S.; funding acquisition, I.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 2.

Time series plot of the JSE Top40 Price Index.

Figure 2.

Time series plot of the JSE Top40 Price Index.

Figure 3.

(a) Log-returns for JSE Top40 stock index, (b) histogram with density curve plot of daily log-returns, (c) normal Q–Q plot of daily log-returns, and (d) boxplot of the JSE Top40 log-returns.

Figure 3.

(a) Log-returns for JSE Top40 stock index, (b) histogram with density curve plot of daily log-returns, (c) normal Q–Q plot of daily log-returns, and (d) boxplot of the JSE Top40 log-returns.

Figure 4.

Missing value plot of each variable of the JSE Top40 index.

Figure 4.

Missing value plot of each variable of the JSE Top40 index.

Figure 5.

ACF and PACF plots of the standardised JSE Top40 log-returns.

Figure 5.

ACF and PACF plots of the standardised JSE Top40 log-returns.

Figure 6.

ACF and PACF plots of the squared standardised JSE Top40 log-returns.

Figure 6.

ACF and PACF plots of the squared standardised JSE Top40 log-returns.

Figure 7.

Time series plot of the Residuals from ARMA(3,2) model.

Figure 7.

Time series plot of the Residuals from ARMA(3,2) model.

Figure 8.

ACF and PACF plots of the Residuals from ARMA(3,2) model.

Figure 8.

ACF and PACF plots of the Residuals from ARMA(3,2) model.

Figure 9.

Histogram and Normal Q-Q plots of the Residuals from ARMA(3,2) model.

Figure 9.

Histogram and Normal Q-Q plots of the Residuals from ARMA(3,2) model.

Figure 10.

Time series plot of the Squared Residuals from ARMA(3,2) model.

Figure 10.

Time series plot of the Squared Residuals from ARMA(3,2) model.

Figure 11.

ACF plot of the Squared Residuals from ARMA(3,2) model.

Figure 11.

ACF plot of the Squared Residuals from ARMA(3,2) model.

Figure 12.

ACF plot of the Standardised Residuals from ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1) model.

Figure 12.

ACF plot of the Standardised Residuals from ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1) model.

Figure 13.

ACF plot of the Squared Standardised Residuals from ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1) model.

Figure 13.

ACF plot of the Squared Standardised Residuals from ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1) model.

Figure 14.

Q-Q and Empirical Density plots of the Standardised Residuals from ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1) model.

Figure 14.

Q-Q and Empirical Density plots of the Standardised Residuals from ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1) model.

Figure 15.

News Impact Curve.

Figure 15.

News Impact Curve.

Figure 16.

Forecast of Standardised Residuals with 90% Prediction Intervals from the ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1)-XGBoost Model.

Figure 16.

Forecast of Standardised Residuals with 90% Prediction Intervals from the ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1)-XGBoost Model.

Figure 17.

Forecast of Standardised Residuals with 95% Prediction Intervals from the ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1)-XGBoost Model.

Figure 17.

Forecast of Standardised Residuals with 95% Prediction Intervals from the ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1)-XGBoost Model.

Figure 18.

Forecast of Standardised Residuals with 99% Prediction Intervals from the ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1)-XGBoost Model.

Figure 18.

Forecast of Standardised Residuals with 99% Prediction Intervals from the ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1)-XGBoost Model.

Figure 19.

Time-Varying Forecast Errors plot.

Figure 19.

Time-Varying Forecast Errors plot.

Table 1.

Results of the Box-Ljung Q test for autocorrelation detection.

Table 1.

Results of the Box-Ljung Q test for autocorrelation detection.

| Lag |

Statistic |

Critical value |

p-value |

| 10 |

|

|

|

| 15 |

|

|

|

| 20 |

|

|

|

| 25 |

|

|

|

| 30 |

|

|

|

| 35 |

|

|

|

Table 2.

Results of the Engle’s ARCH LM test for heteroscedasticity detection.

Table 2.

Results of the Engle’s ARCH LM test for heteroscedasticity detection.

| Lag |

Statistic |

Critical value |

p-value |

| 10 |

|

|

|

| 15 |

|

|

|

| 20 |

|

|

|

| 25 |

|

|

|

| 30 |

|

|

|

| 35 |

|

|

|

Table 3.

Summary of stationarity and normality tests for the log-returns.

Table 3.

Summary of stationarity and normality tests for the log-returns.

| Test |

Statistic |

p-value |

Conclusion |

Decision |

| ADF |

|

|

Reject H0

|

Stationary |

| KPSS |

|

|

Fail to reject H0

|

Stationary |

| JB |

|

|

Reject H0

|

Not normally distributed |

Table 4.

Summary statistics of the log-returns.

Table 4.

Summary statistics of the log-returns.

| Min |

|

|

Mean |

|

Max |

SD |

Skew |

Kurt |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 5.

Box-Lyung and JB test on the ARMA(3,2) Residuals.

Table 5.

Box-Lyung and JB test on the ARMA(3,2) Residuals.

| Lag |

Statistic |

p-value |

| 10 |

|

|

| 15 |

|

|

| 20 |

|

|

| 25 |

|

|

| 30 |

|

|

| 30 |

|

|

|

|

|

Table 6.

Engle’s ARCH LM test on the ARMA(3,2) Residuals.

Table 6.

Engle’s ARCH LM test on the ARMA(3,2) Residuals.

| Lag |

Statistic |

p-value |

| 10 |

|

|

| 15 |

|

|

| 20 |

|

|

| 25 |

|

|

| 30 |

|

|

Table 7.

Box-Ljung test on the ARMA(3,2) Squared Residuals.

Table 7.

Box-Ljung test on the ARMA(3,2) Squared Residuals.

| Lag |

Statistic |

p-value |

| 10 |

|

|

| 15 |

|

|

| 20 |

|

|

| 25 |

|

|

| 30 |

|

|

Table 8.

Evaluation metrics for ARMA(3,2)–GARCH-type models under different conditional distributions.

Table 8.

Evaluation metrics for ARMA(3,2)–GARCH-type models under different conditional distributions.

| |

Conditional Distributions |

| Model |

|

STD |

SSTD |

GED |

SGED |

GHD |

| ARMA(3,2)-sGARCH(1,1) |

AIC |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

BIC |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

HQIC |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

LL |

|

|

|

|

|

| ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1) |

AIC |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

BIC |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

HQIC |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

LL |

|

|

|

|

|

| ARMA(3,2)-GJR-GARCH(1,1) |

AIC |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

BIC |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

HQIC |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

LL |

|

|

|

|

|

Table 9.

Box-Lyung test on the ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1) Standardised Residuals.

Table 9.

Box-Lyung test on the ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1) Standardised Residuals.

| Lag |

Statistic |

p-value |

| 1 |

|

|

| 14 |

|

|

| 24 |

|

|

Table 10.

Engle’s ARCH LM test on the ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1) Standardised Residuals.

Table 10.

Engle’s ARCH LM test on the ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1) Standardised Residuals.

| Lag |

Statistic |

p-value |

| 3 |

|

|

| 5 |

|

|

| 7 |

|

|

Table 11.

Box-Ljung test on the ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1) Squared Standardised Residuals.

Table 11.

Box-Ljung test on the ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1) Squared Standardised Residuals.

| Lag |

Statistic |

p-value |

| 1 |

|

|

| 5 |

|

|

| 9 |

|

|

Table 12.

Sign Bias Test Results.

Table 12.

Sign Bias Test Results.

| |

t-value |

p-value |

| Sign Bias |

|

|

| Negative Sign Bias |

|

|

| Positive Sign Bias |

|

|

| Joint Effect |

|

|

Table 13.

Parameter Estimates of the ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1) model.

Table 13.

Parameter Estimates of the ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1) model.

| Parameter |

Estimate |

p-value |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 14.

First 10 Forecast Results from the Hybrid ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1)-XGBoost Model.

Table 14.

First 10 Forecast Results from the Hybrid ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1)-XGBoost Model.

| Actual |

Prediction |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 15.

Forecast Accuracy Measure Results from the Hybrid ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1)-XGBoost Model.

Table 15.

Forecast Accuracy Measure Results from the Hybrid ARMA(3,2)-EGARCH(1,1)-XGBoost Model.

| Forecast Accuracy Measures |

|---|

| MASE |

RMSE |

MAE |

MAPE(%) |

sMAPE(%) |

|

|

|

|

|

Table 16.

Evaluation Metrics of the Prediction Intervals

Table 16.

Evaluation Metrics of the Prediction Intervals

| Evaluation Metrics |

|---|

| PINC(%) |

PICP(%) |

PINAW(%) |

PICWA(%) |

PINAD(%) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|