1. Introduction

In the face of accelerating climate change and growing environmental risks, the global banking sector is undergoing a paradigm shift towards sustainable finance. Climate scenarios and climate stress testing have emerged as critical tools in this transition, offering structured frameworks for anticipating the financial impacts of climate-related risks over the medium and long term. These tools help financial institutions navigate the uncertainties associated with the low-carbon transition, assess vulnerabilities to physical and transition risks, and align business strategies with regulatory and sustainability objectives.

The origins of climate scenario analysis can be traced back to the late 19th century, with Svante Arrhenius’ pioneering work on the warming effects of carbon dioxide emissions (Carbon Brief, 2023). Scientific progress accelerated in the second half of the 20th century through the development of General Circulation Models (GCMs), enabling large-scale simulations of the Earth’s climate system. The establishment of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in 1988 marked a turning point in consolidating climate science, resulting in standardized global scenarios such as the Special Report on Emissions Scenarios (SRES), Representative Concentration Pathways (RCPs), and more recently, Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs) (IPCC, 2021).

In the financial sector, interest in applying these scenarios has intensified since 2017, following the creation of the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS). This coalition of central banks and financial supervisors has promoted the integration of climate-related data and models into financial oversight frameworks. Key institutions such as the European Central Bank (ECB) and the European Banking Authority (EBA) have since developed and implemented regulatory tools—such as climate stress tests and ESG risk management guidelines—grounded in NGFS and IPCC scenarios.

This paper examines the evolution, definition, and application of climate scenarios in the context of global banking strategy. It explores the underlying principles of scenario design—plausibility, diversity, transparency, comparability, and stress testing—and analyzes the contributions of NGFS, ECB, and EBA in shaping current regulatory expectations. Furthermore, the study identifies critical implementation challenges and proposes practical recommendations for integrating climate scenarios into the risk management and strategic planning processes of financial institutions. Ultimately, the paper argues that climate scenarios, if properly embedded in supervisory frameworks and internal governance, can act as catalysts for a more resilient and sustainable financial system.

2. Literature Review

The intersection of climate change and financial regulation has given rise to a growing body of literature that examines the role of scenario analysis and climate stress testing in ensuring financial stability and enabling sustainable transitions. This section synthesizes relevant academic, institutional, and regulatory research that underpins the integration of climate scenarios into the global banking strategy.

2.1. Evolution of Climate Scenarios in Science and Policy

Scientific literature has long emphasized the need for structured projections of climate change, beginning with Arrhenius’ early quantification of the greenhouse effect in the 19th century. The formalization of climate scenario frameworks began with the IPCC’s Special Report on Emissions Scenarios (SRES), followed by the development of Representative Concentration Pathways (RCPs) and, more recently, the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs). These models provide the backbone for understanding the physical impacts of climate change under various emissions trajectories and socioeconomic developments (IPCC, 2021).

The SSP-RCP framework, introduced in the IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report, has allowed for more nuanced modeling of future climate risks, incorporating variables such as population growth, economic inequality, energy systems, and policy choices. These scenarios are not forecasts, but rather plausible narratives designed to test systemic vulnerabilities across different dimensions (O’Neill et al., 2017; Hausfather & Peters, 2020).

2.2. Climate Risk and the Financial Sector

The literature on financial sector exposure to climate risks has expanded significantly since the 2015 Paris Agreement. Seminal studies have distinguished between physical risks —such as extreme weather events and sea-level rise—and transition risks , associated with policy, technology, and market changes during the low-carbon shift (Battiston et al., 2017; NGFS, 2020). These risks can affect the value of financial assets, credit risk assessments, and long-term solvency of institutions.

Central banks and regulators have started integrating climate risk into supervisory frameworks, as highlighted by the work of Carney (2015) and further expanded through NGFS publications. The emphasis has shifted from awareness to action, with increasing calls for mandatory disclosure and integration of forward-looking climate scenarios into capital adequacy and stress-testing exercises (Vermeulen et al., 2019; ECB, 2022).

2.3. The Role of NGFS, ECB, and EBA in Scenario Development and Regulation

The NGFS has been instrumental in operationalizing climate scenario analysis for central banks and supervisors. Its scenario framework—published in 2020 and updated regularly—offers three core narratives: Orderly Transition , Disorderly Transition , and Hot House World . These narratives incorporate assumptions on emissions, carbon pricing, energy demand, and climate policy implementation, offering both qualitative and quantitative insights (NGFS, 2022).

Building on this, the European Central Bank (ECB) conducted its first climate stress test in 2022, applying NGFS scenarios to assess capital, liquidity, and profitability risks among 104 significant euro area banks. The results highlighted major gaps in banks’ preparedness, particularly in integrating climate risks into internal risk frameworks (ECB, 2022).

Simultaneously, the European Banking Authority (EBA) has issued regulatory guidelines (EBA/GL/2022/05) mandating the integration of ESG risks—including climate—into banks’ Internal Capital Adequacy Assessment Processes (ICAAP) and governance models. These regulations are supported by Pillar III disclosure requirements and coordinated supervision under the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM), aligning prudential and sustainability objectives (EBA, 2022).

2.4. Methodological Challenges in Climate Scenario Integration

The academic literature also identifies multiple challenges in applying climate scenarios in financial analysis. These include the long-time horizons (often beyond traditional business planning), the high uncertainty of climate models, data gaps in emissions and exposure, and the need for harmonization across jurisdictions (Batten et al., 2016; Bolton et al., 2020). There is also debate about the calibration of scenarios to capture systemic, non-linear, and cascading effects within the financial system.

Moreover, while scenario narratives are useful for exploring potential futures, they do not provide probabilities, and there is a risk of misinterpretation if used improperly for decision-making or risk pricing. Recent efforts seek to develop hybrid frameworks that integrate macroprudential modeling with scenario-based stress tests, emphasizing robustness over precision (NGFS, 2022; van der Ploeg & Rezai, 2020).

3. Methodology

This study employs a qualitative research design based primarily on the analysis of empirical studies and publicly available case studies conducted by central banks, financial regulators, and international institutions engaged in climate risk assessment. The objective is to critically evaluate how climate scenarios are developed, interpreted, and operationalized within the global banking system, with a focus on the European regulatory context.

3.1. Research Design and Approach

Given the complexity and multi-dimensionality of climate scenario integration in banking, a multiple-case study approach was adopted. This methodology allows for an in-depth, comparative exploration of institutional practices, regulatory strategies, and supervisory methodologies related to climate stress testing and scenario analysis.

The research is exploratory and interpretive , aiming to extract patterns, best practices, and implementation challenges across jurisdictions. Rather than collecting new primary data, the study builds on secondary data sources published by central banks and financial authorities, including stress test results, regulatory guidance, technical annexes, scenario documentation, and thematic reviews.

3.2. Selection of Case Studies

Three key institutions were selected for case-based analysis, based on their leadership in climate scenario integration and the availability of documented methodologies: The Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) – Selected for its global role in scenario development and methodological standardization; the European Central Bank (ECB) – Selected for its 2022 climate stress test, which applied NGFS scenarios to 104 euro area banks, and the European Banking Authority (EBA) – Selected for its regulatory guidelines on ESG risk integration and supervisory convergence through the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM). These institutions represent both the normative (rule-setting) and operational (implementation) dimensions of climate risk management in the financial sector.

3.3. Data Sources

The data used in this study consists of publicly accessible, institutional-level documentation , including but not limited to: NGFS Climate Scenarios (2020, 2022 editions), ECB Climate Stress Test Methodology and Results (2022), EBA Guidelines on ESG Risk Management (EBA/GL/2022/05), related working papers, technical notes, consultation documents, and macroprudential reviews, and supplementary literature from academic and policy journals that analyze or critique these efforts. Documents were selected based on relevance, recency (post-2017), and methodological transparency. Triangulation of sources ensured the robustness and credibility of interpretations.

3.4. Analytical Framework

The analysis is structured along four core dimensions: scenario design – Plausibility, diversity, and scientific grounding of scenario narratives (eg, orderly vs. disorderly transition), regulatory integration – how scenarios are embedded in prudential frameworks (eg, ICAAP, Pillar II/III, capital planning), supervisory practices – methods used in climate stress testing (eg, top-down vs. bottom-up models, horizon and granularity), and institutional gaps and recommendations – identification of implementation challenges and opportunities for harmonization and improvement. Each case was analyzed using a thematic coding strategy, allowing for cross-case comparisons and synthesis of insights relevant to both policy and practice.

This study is limited by its reliance on secondary data , which may not capture internal deliberations, confidential supervisory data, or unpublished pilot exercises. Moreover, while the focus is on European institutions, global developments—particularly in emerging economies—are not extensively covered, which may affect generalizability beyond the EU context.

Nevertheless, the selected case studies offer rich empirical insights and provide a solid basis for understanding the institutional mechanisms driving the integration of climate scenarios into banking strategy.

4. Results and Discussion

This section presents the key findings of the research and discusses the implications of integrating climate scenarios into banking operations. Drawing from institutional case studies, empirical stress test results, and analytical tools, we examine how central banks and financial supervisors are embedding climate scenario analysis into prudential frameworks.

4.1. Climate Stress Testing: A Core Application Area

One of the most significant applications of climate scenarios in the banking sector is through climate stress testing . These simulations evaluate the resilience of financial institutions under various climate transition and physical risk scenarios. They assess the potential impact on capital adequacy, credit portfolios, and operational continuity over medium- and long-term horizons ( Manta O, Palazzo M., 2024) .

In 2022, the European Central Bank (ECB) conducted its first climate stress test , covering 104 significant institutions in the euro area. The exercise was both top-down and bottom-up in structure and focused on three key risk categories: capital depletion, credit losses, and exposure concentration. Key findings include:

Around 60% of banks had not yet developed a climate risk stress testing framework internally.

Over €70 billion in potential losses were estimated under the adverse scenario over a 30-year time horizon , driven mainly by transition risk in high-emission sectors (ECB, 2022).

Over 20% of banks reported high exposure to carbon-intensive sectors , such as fossil fuels, transportation, and heavy industry.

Credit portfolios showed limited sectoral diversification , increasing systemic vulnerabilities in the event of disorderly policy transitions.

These results demonstrate the importance of aligning risk management practices with climate scenario analysis, not only for regulatory compliance but also for long-term solvency and strategic positioning.

4.2. Technological and Analytical Tools Supporting Scenario Integration

In parallel with supervisory efforts, digitalization has supported the development of advanced analytics tools that enhance scenario-based modeling. Tools such as ICE’s Climate Transition Analytics Tool and the Climate Action Tracker have enabled banks to:

Map portfolio alignment with Net Zero trajectories;

Estimated carbon intensity at issuer and portfolio levels;

Simulated policy pathways and their economic-financial impact.

These tools also integrate NGFS scenario pathways and use sectoral benchmarks to estimate relative exposure and transition gaps. For instance, ICE’s platform incorporates real-economy metrics and policy scenarios calibrated to NGFS models (ICE, 2024).

4.3. Broader Applicability Across the Financial System

Stress testing and climate scenario analysis are increasingly being used by insurers, pension funds, and asset managers , in line with recommendations by the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) . A 2023 TCFD review reported that over 1,500 institutions globally had implemented some form of climate scenario analysis in their risk or investment frameworks (TCFD, 2023). The convergence of methods across sectors strengthens financial system resilience to environmental disruptions.

4.4. Empirical Evidence of Climate Intensification

Empirical climate data further justifies the use of scenarios. According to the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) , between 2000 and 2023 , the number of extreme weather events globally has increased by over 80% , with direct losses exceeding $2.5 trillion . In Europe, heatwaves and floods have become more frequent and intense, with significant implications for real estate-backed loans and agricultural credit lines (WMO, 2023).

NASA (2024) data confirms that the global average temperature has risen by approximately 1.2°C above pre-industrial levels, with 2023 being the warmest year on record . These shifts not only affect asset valuations but also increase credit default risk , particularly for long-duration loans and mortgage portfolios in high-risk zones.

4.5. Critical Appraisal of Current Stress Testing Practices

Despite growing adoption, climate stress testing methodologies still face several critical limitations :

Underestimation of tail risks , particularly low-probability, high-impact events known as “Green Swan” events (BIS, 2020; SSRN, 2023 );

Limited data granularity , especially in emerging markets or for small-to-medium banks lacking climate data infrastructure;

Inconsistent methodologies across jurisdictions (eg, scenario assumptions, time horizons, valuation metrics), which impedes cross-country comparability;

Difficulty translating long-term scenario results into short-term financial planning , which constrains managerial actionability (ECB, 2022; EBA, 2022 );

Inadequate modeling of feedback loops between the real economy, the environment, and the financial system.

Table 1 presents the scheme of the integrated climate stress testing process in banks, highlighting the essential stages, main activities and responsibilities related to each phase. The process begins with the diagnosis of exposure, where risk management maps portfolios and regulates climate risks. Then,

the risk and climate analysis team adapts the NGFS and ECB scenarios to the specifics of the financial institution, ensuring the relevance of the tests . This is followed by the modeling and simulation stage, in which the finance team assesses the potential impact on the bank’s capital and liquidity. Next, the compliance department is in charge of reporting to regulatory authorities, such as the EBA and the ECB, as well as publicly communicating the results. The process ends with the implementation and monitoring of exposure reduction plans, a responsibility assumed by top management and strategic teams, for an effective and sustainable management of climate risks ( Iddagoda A et all, 2023) .

Table 2 presents the typical structure of climate risk reporting according to EBA requirements, highlighting the essential elements that financial institutions must include in their documentation. This structure includes, first of all, the presentation of the methodology used for climate risk management, which provides the theoretical and procedural framework of the assessment. This is followed by the detailed analysis of the portfolio exposed to physical and transition risks, essential for identifying specific vulnerabilities. The results of stress tests on multiple scenarios provide a clear perspective on the potential financial impacts, complemented by an assessment of the effects on capital and liquidity. The reporting also includes concrete adjustment and adaptation plans, which reflect the banks’ commitment to proactively manage these risks. Finally, the section dedicated to the future risk and opportunity landscape underlines the importance of a strategic vision that capitalizes on both the challenges and potential benefits generated by the transition to a sustainable economy. This integrated structure ensures increased transparency and a coherent approach to managing climate risks in the banking sector.

The ECB acknowledged in its 2022 report that “climate risk integration into banks’ internal models remains embryonic” and emphasized the need for enhanced governance structures and board-level engagement on climate-related risks.

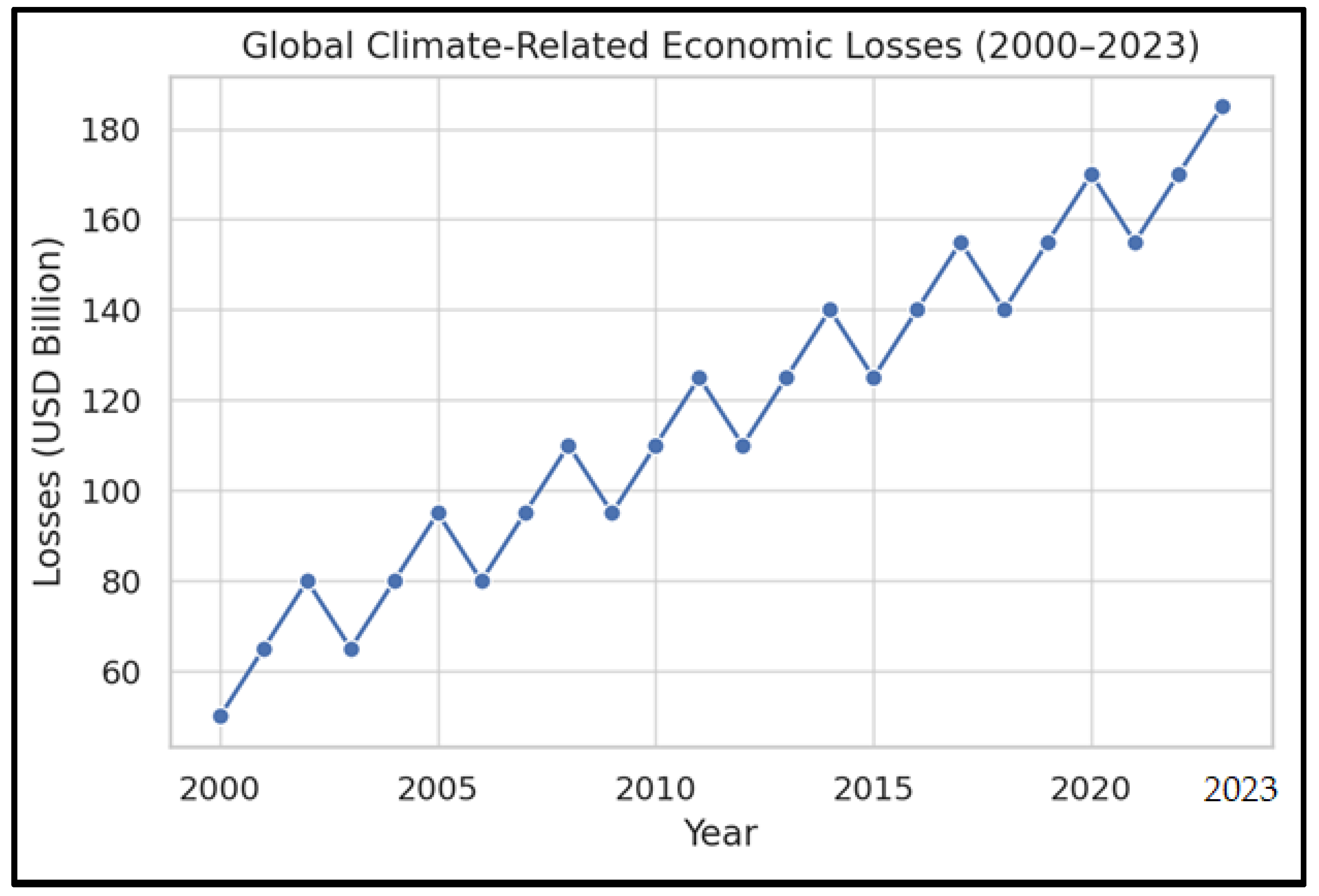

Figure 1.

Global economic losses associated with climate events (2000–2023). Source: author’s processing, Swiss Re Sigma Report on Natural Catastrophes, 2024.

Figure 1.

Global economic losses associated with climate events (2000–2023). Source: author’s processing, Swiss Re Sigma Report on Natural Catastrophes, 2024.

The figure above shows global economic losses associated with climate events over the period 2000–2023, showing a clear upward trend. This trend reflects the increasing frequency and severity of extreme climate events, such as floods, hurricanes and droughts, which are causing increasing damage to infrastructure, agriculture and economic activities worldwide. As climate change becomes more pronounced, the financial impact of these events continues to increase, underscoring the urgent need for effective climate risk adaptation and mitigation strategies.

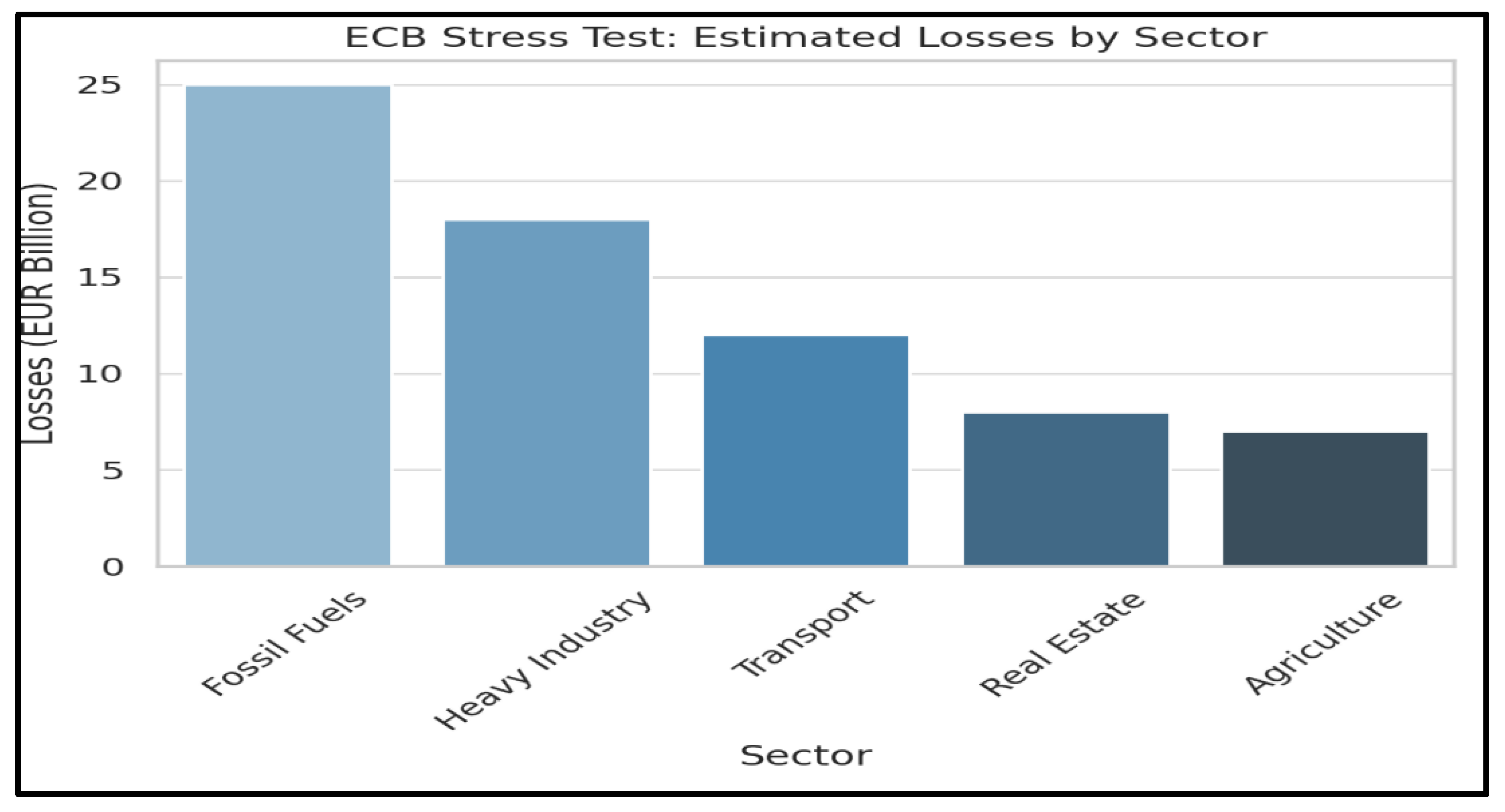

Figure 2.

Results stress tests ECB climate action (2022). Source: author’s processing, ECB Climate Stress Test 2022.

Figure 2.

Results stress tests ECB climate action (2022). Source: author’s processing, ECB Climate Stress Test 2022.

The figure below reflects the results of the European Central Bank’s 2022 climate stress tests, highlighting the estimated potential losses for the economic sectors most vulnerable to climate risks. These tests highlight the different impacts of climate change on different branches of the economy, identifying sectors with high exposures to extreme events and the transition to a low-carbon economy. The results provide crucial insight for policymakers and financial institutions, who need to integrate these risks into their management strategies to ensure long-term economic resilience.

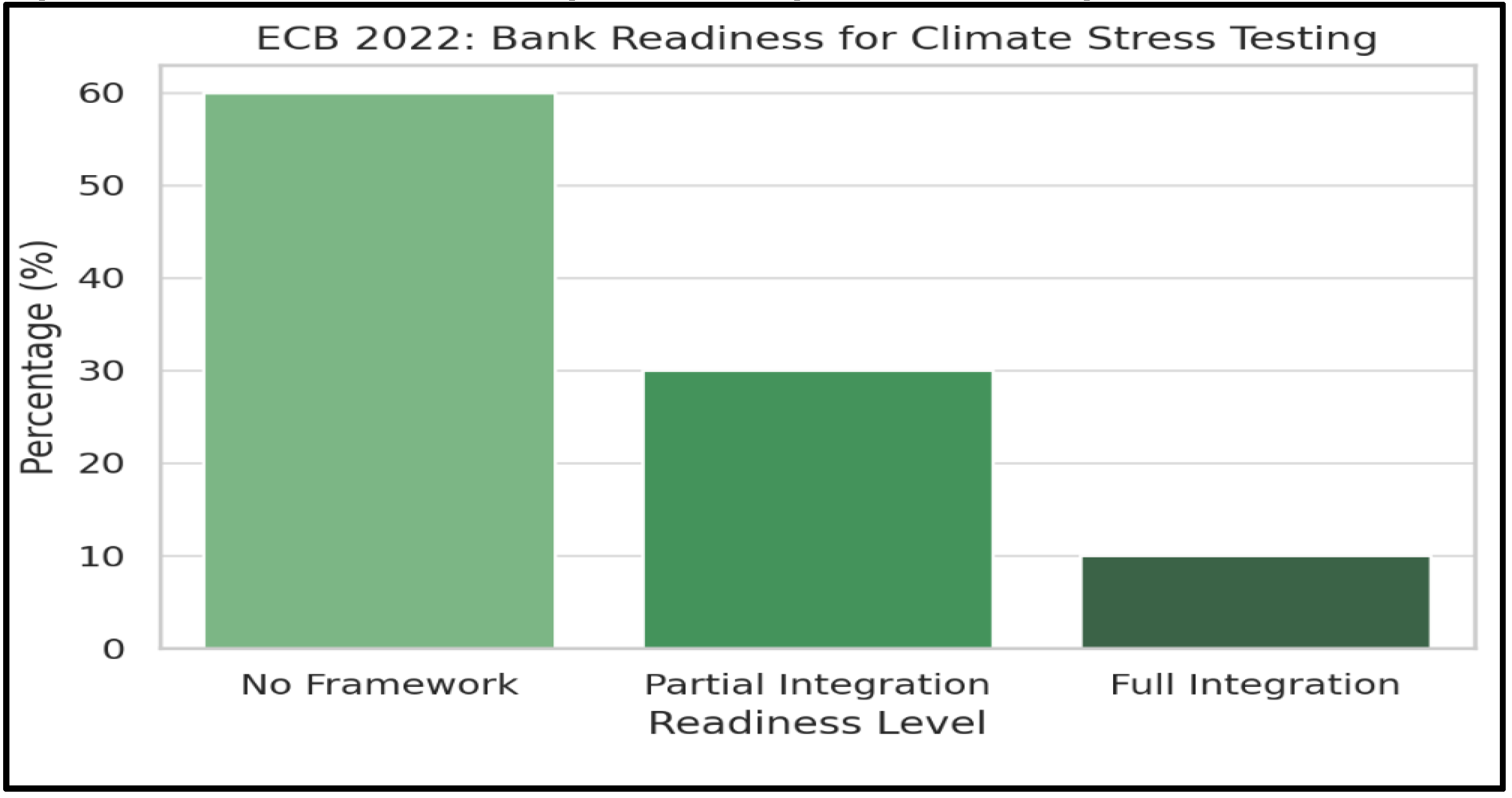

Figure 3.

Banks’ readiness to integrate climate risks. Source: authors’ processing, EBA Report on Management and Supervision of ESG risks in the banking sector (2022).

Figure 3.

Banks’ readiness to integrate climate risks. Source: authors’ processing, EBA Report on Management and Supervision of ESG risks in the banking sector (2022).

The analysis of banks’ readiness to integrate climate risks shows that most financial institutions do not yet have an adequate functional framework in place. This reflects the significant challenges in developing and implementing clear policies and procedures to manage climate change risks. The lack of such a framework may limit banks’ ability to properly assess climate risk exposures and take proactive measures to mitigate them, underscoring the urgent need for strengthened governance and specific tools in the financial sector.

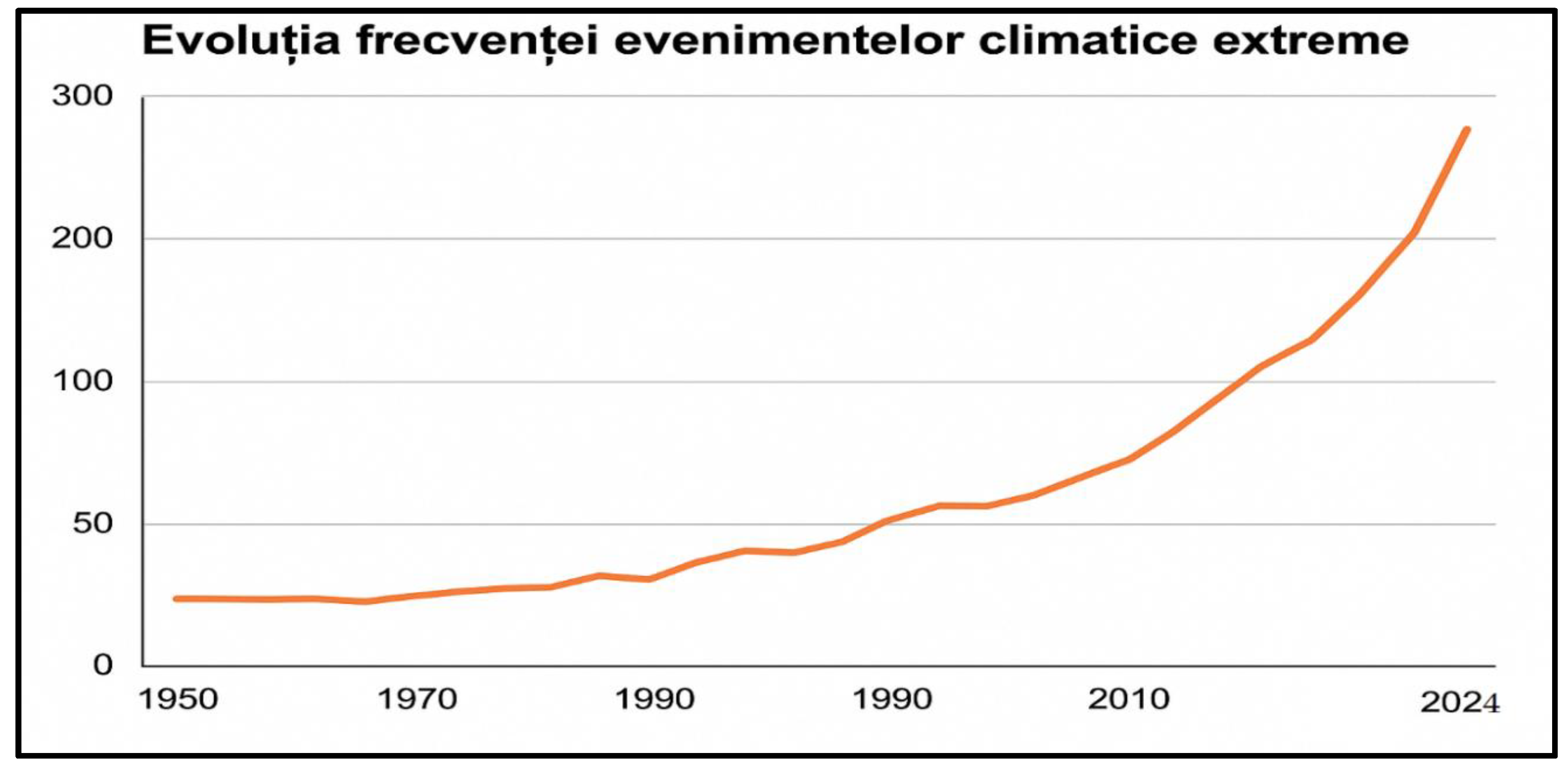

The evolution of the frequency of extreme climate events during the period 1950–2024, illustrated in the graph above (

Figure 4), shows a significant and accelerated increase in the frequency of heat waves, floods and droughts globally. This trend is supported by data updated by

the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) and

NASA , which highlight INCREASE events extreme climates as a result of climate change cLIMATE anthropogenic . Growth frequently THESE event reflect the impact accumulated heating globe on systems natural , what What generates risks INCREASED for ecosystems , infrastructure and societies across the world world .

5. Recommendations and Practical Steps for Enhancing the Implementation of Climate Scenarios and Stress Testing

Strategic Recommendations

To effectively integrate climate scenario analysis and stress testing into the core banking framework, several strategic directions are recommended:

Advance sector- and region-specific modeling methodologies by developing granular and calibrated tools that reflect differentiated climate exposure across geographies and industries.

Improve data quality and accessibility through institutional partnerships between public authorities, academic institutions, and the private sector. Harmonized climate and financial datasets are essential for robust scenario construction.

Incorporate dynamic modeling frameworks , including feedback loops between the financial system, the economy, and environmental variables, to capture the complexity of climate impacts.

Establish harmonized disclosure and benchmarking frameworks , aligned with the guidelines of the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) and the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), to enable comparability and transparency across institutions.

Strengthen climate competence within the financial sector by investing in specialized training for risk managers, analysts, and supervisors. Capacity building is essential to interpret scenario outputs and translate them into strategic actions.

Adopt proactive transition strategies , embedded at the board and executive levels, to ensure climate-related risks are considered in all phases of business planning, risk appetite setting, and capital allocation.

Operational Implementation Steps

To operationalize these recommendations, financial institutions should adopt the following sequential and actionable steps:

Clearly define governance responsibilities related to climate risk within the bank’s organizational structure, assigning oversight to executive leadership and dedicated committees.

Select and calibrate NGFS climate scenarios that are relevant to the institution’s business model, geographic exposure, and value chain, ensuring contextual sensitivity.

Develop financial risk models that assess the impact of physical and transition risks on credit, market, and operational exposures across various time horizons.

Periodically conduct climate stress tests , integrating results into the institution’s capital planning, ICAAP frameworks, and business continuity strategies.

Establish transparent reporting mechanisms to communicate climate risk exposures, scenario results, and mitigation actions to regulators, shareholders, and the broader public.

Continuously update scenarios and assumptions based on evolving climate science, policy developments, and technological advancements.

Adopt a dynamic and forward-looking risk posture , which includes concrete de-risking measures such as portfolio rebalancing, strategic divestment, or green lending policies.

6. Conclusions, Limitations, and Directions for Future Research

Conclusions

This study underscores the critical role of climate scenarios and climate stress testing as strategic tools in enabling a sustainable transition within the global banking sector. The integration of these instruments is no longer optional, but rather a necessity for institutions seeking to manage long-term climate-related risks and align their operations with international regulatory expectations. The analysis reveals that organizations such as the NGFS, ECB, and EBA have laid important foundations for scenario design, stress test frameworks, and supervisory alignment.

However, while progress has been made in scenario development, challenges remain regarding their operationalization, comparability, and strategic relevance at the institutional level. The use of digital analytical tools, improved data infrastructures, and harmonized risk reporting are essential enablers for deepening the impact of these frameworks. Furthermore, the growing intensity and frequency of climate-related events underscore the urgency of embedding these assessments into capital planning, governance structures, and broader business strategy.

Limitations of the Study

While this paper provides a comprehensive review of existing frameworks and empirical applications by central banks and regulatory bodies, it has certain limitations:

Lack of original empirical modeling : The analysis relies on secondary data and case studies rather than proprietary stress test simulations or econometric models.

Institutional bias : The study focuses primarily on European institutions (ECB, EBA, NGFS), potentially overlooking unique approaches from emerging markets or non-European jurisdictions.

Temporal limitations : The fast-evolving nature of climate risk frameworks means that some findings may become outdated as methodologies improve or new regulatory mandates are introduced.

Limited granularity : Sector-specific impacts are discussed at an aggregated level; further disaggregation by bank type, region, or size would enhance the applicability of insights.

Directions for Future Research

Future research should build on these insights by:

Developing quantitative stress testing models that simulate climate risk transmission channels using real banking data, particularly in emerging and developing economies.

Exploring behavioral responses of financial institutions and regulators to climate scenarios, including risk aversion, capital allocation, and governance shifts.

Assessing the effectiveness of scenario-based strategies in actually reducing portfolio-level emissions or reorienting credit towards green investments.

Comparing jurisdictional approaches to climate stress testing to identify best practices and gaps in international coordination.

Integrating socio-economic variables such as inequality, labor market shifts, and regional vulnerability into stress testing models to better reflect systemic impacts.

In the context of accelerating climate change and increasing regulatory expectations, the integration of climate scenarios and stress testing within banking frameworks represents not only a risk management imperative, but also a strategic lever for long-term financial resilience. As banks evolve from awareness to action, the quality of scenario design, the robustness of institutional responses, and the alignment with international standards will determine the credibility and effectiveness of their climate transition efforts. This study contributes to the ongoing dialogue by mapping current practices, identifying key implementation gaps, and outlining a pathway towards more resilient and forward-looking banking systems capable of supporting a sustainable global economy.

References

- Battiston, S.; Mandel, A.; Monasterolo, I.; Schütze, F.; Visentin, G. A climate stress-test of the financial system. Nature Climate Change 2017, 7, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batten, S.; Sowerbutts, R.; Tanaka, M. (2016). Let’s talk about the weather: The impact of climate change on central banks. Bank of England Staff Working Paper, No. 603. https://www.bankofengland.co.uk.

- Bolton, P.; Després, M. ; Pereira da Silva, LA, Samama, F.; Svartzman, R. (2020). The Green Swan: Central banking and financial stability in the age of climate change, Bank for International Settlements. https://www.bis.org/publ/othp31.htm.

- Bundesbank & NGFS. (2023). NGFS Climate Scenarios for Central Banks and Supervisors, NGFS Climate Scenarios for Central Banks and Supervisors . https://www.ngfs.net.

- Carbon Brief. (2023). Timeline: The history of climate modeling, https://www.carbonbrief.org.

- Carney, M. (2015). Breaking the tragedy of the horizon – Climate change and financial stability. Speech at Lloyd’s of London, 2015; https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/speech/2015. [Google Scholar]

- European Banking Authority (EBA). (2022). Report on management and supervision of ESG risks for credit institutions and investment firms, https://www.eba.europa.eu.

- European Central Bank (ECB). (2022). 2022 Climate Risk Stress Test, https://www.ecb.europa.eu.

- Hausfather, Z.; Peters, G.P. Emissions – the ‘business as usual’ story is misleading. Nature 2020, 577, 618–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICE Data Services. (2024). Climate Transition Analytics Tool – Technical Guide, Intercontinental Exchange. https://www.theice.com.

- Iddagoda A, Manta O, Dissanayake H, Abeysinghe R, Perera D. Combatting Environmental Crisis: Green Orientation in the Sri Lanka Navy. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2023; 16, 180. [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). (2021). Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis, Report (AR6). Geneva: IPCC. https, Sixth Assessment Report (AR6). Geneva: IPCC. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1.

- Manta O, Palazzo M. Transforming Financial Systems: The Role of Time Banking in Promoting Community Collaboration and Equitable Wealth Distribution. FinTech. 2024; 3, 407-423. [CrossRef]

- National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). (2024). Extreme Weather and Climate Change, https://climate.nasa.gov.

- Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS). (2023). Climate Scenarios for Central Banks and Supervisors – Technical Documentation, https://www.ngfs.net.

- O’Neill, BC, Kriegler, E. ; Riahi, K.; et al. The roads ahead: Narratives for shared socioeconomic pathways describing world futures in the 21st century. Global Environmental Change 2017, 42, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SSRN. (2023). Climate Risk Stress Testing: A Critical Survey and Classification, Science Research Network, https://www.ssrn.com.

- Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD). (2023). Scenario Analysis in Climate-Related Risk Disclosure, Stability Board, Financial Stability Board. https://www.fsb.org.

- van der Ploeg, F.; Rezai, A. The risk of policy tipping and stranded carbon assets. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 2020, 100, 102–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeulen, R.; Schets, E.; Lohuis, M.; Kouwenberg, R.; Jansen, D. (2019). The Heat Is On: Climate Risk Exposure in the Financial Sector. ECB Working Paper, No. 632. https://www.ecb.europa.eu.

- World Meteorological Organization (WMO). (2023). Climate Change and Heatwaves – State of the Global Climate 2023, https://public.wmo.int.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).