Submitted:

30 July 2025

Posted:

06 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Problem Statement and Mathematical Formulation

2.1. Schematic Representation

2.2. Simplifying Assumptions

2.3. Governing Equations

2.4. Initial and Boundary Conditions

2.5. Dimensionless Numbers

3. Numerical Procedure

4. Verification of Grid Independent and Validation of Computer Program

5. Evaluation of Dimensionless Shadow Area for Different Designs of SGSP

6. Numerical Results and Discussion

6.1. Time–Wise Evolutions of Temperature, Velocity and Concentration Fields in the SGSP

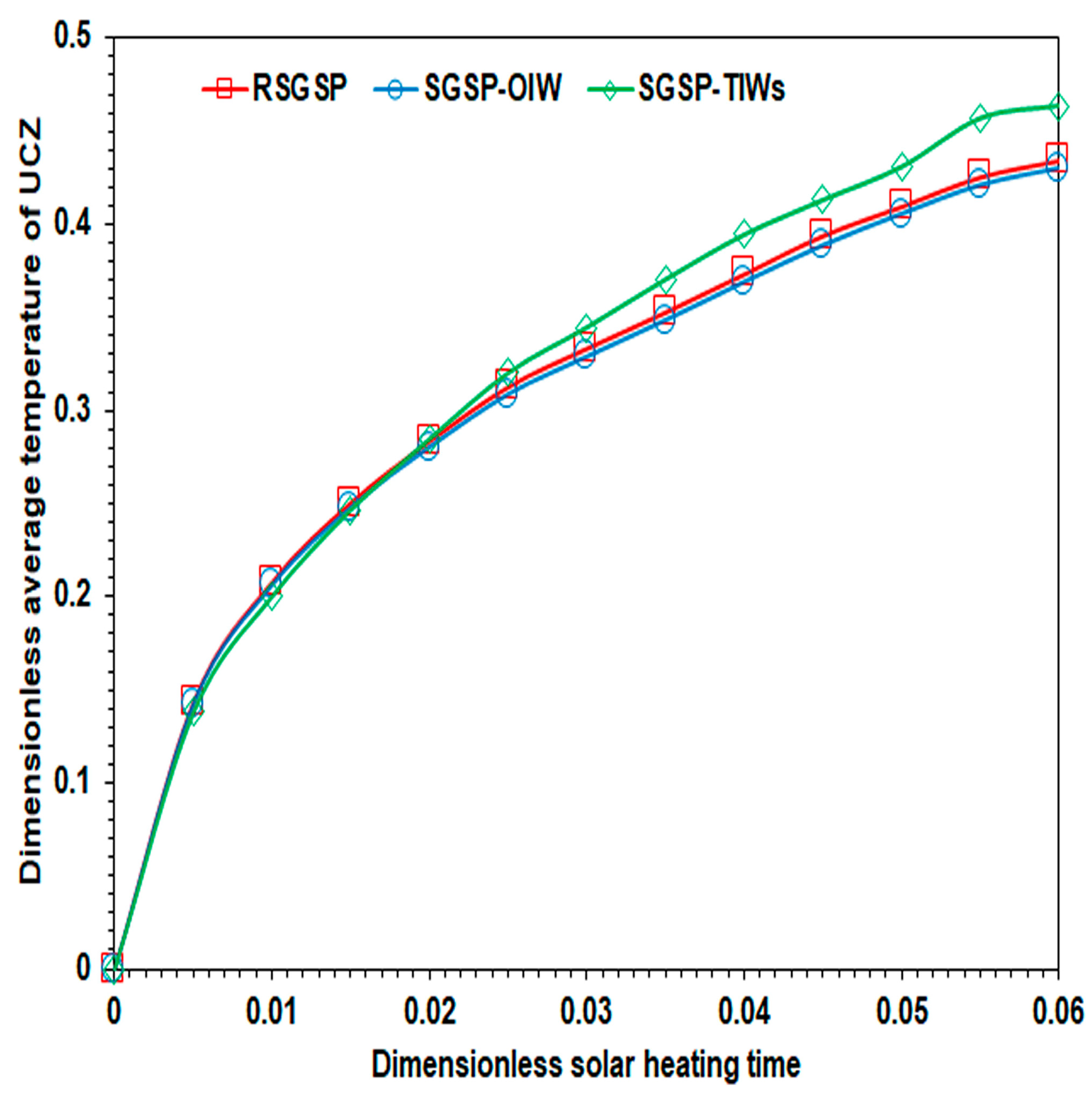

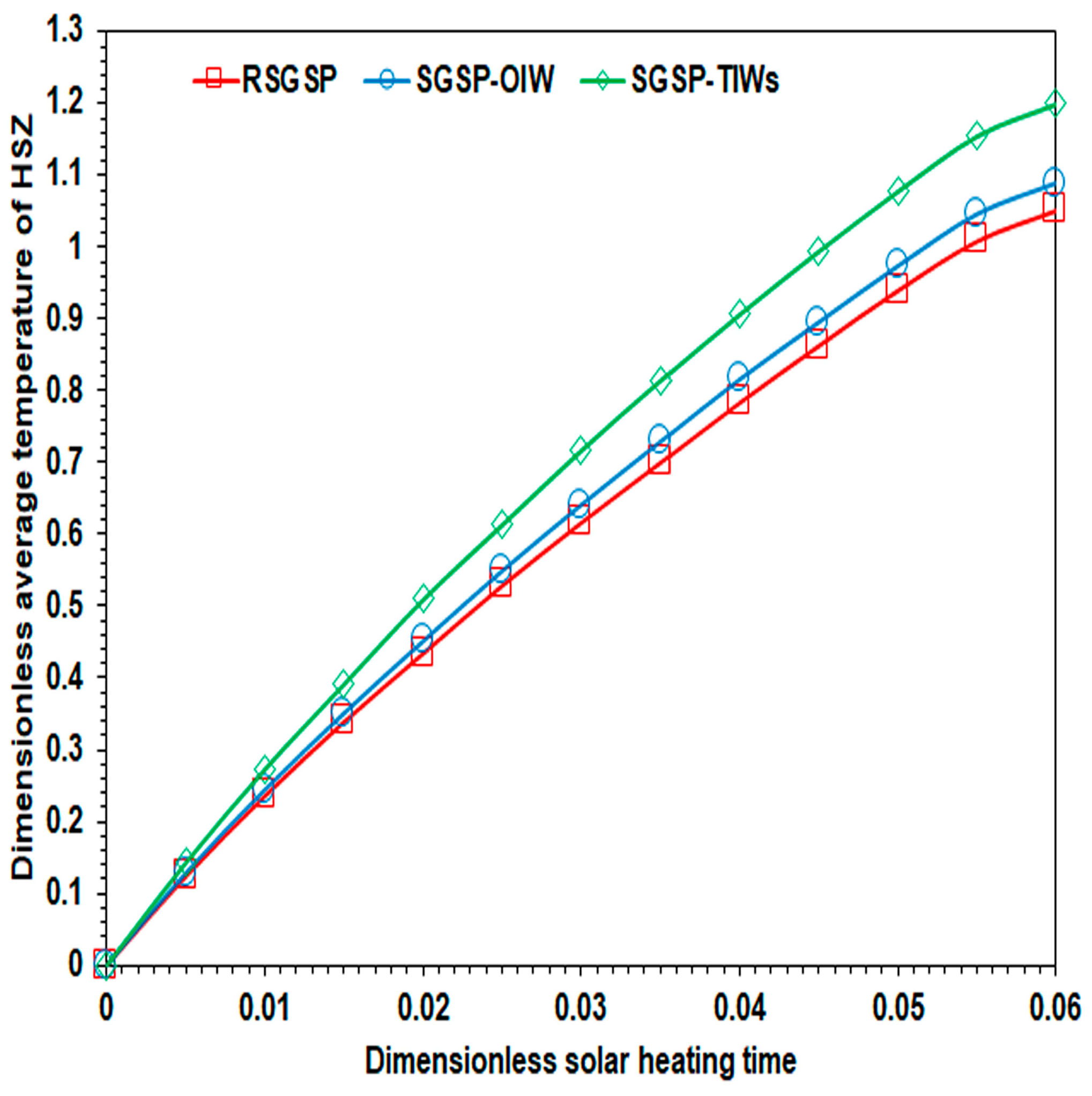

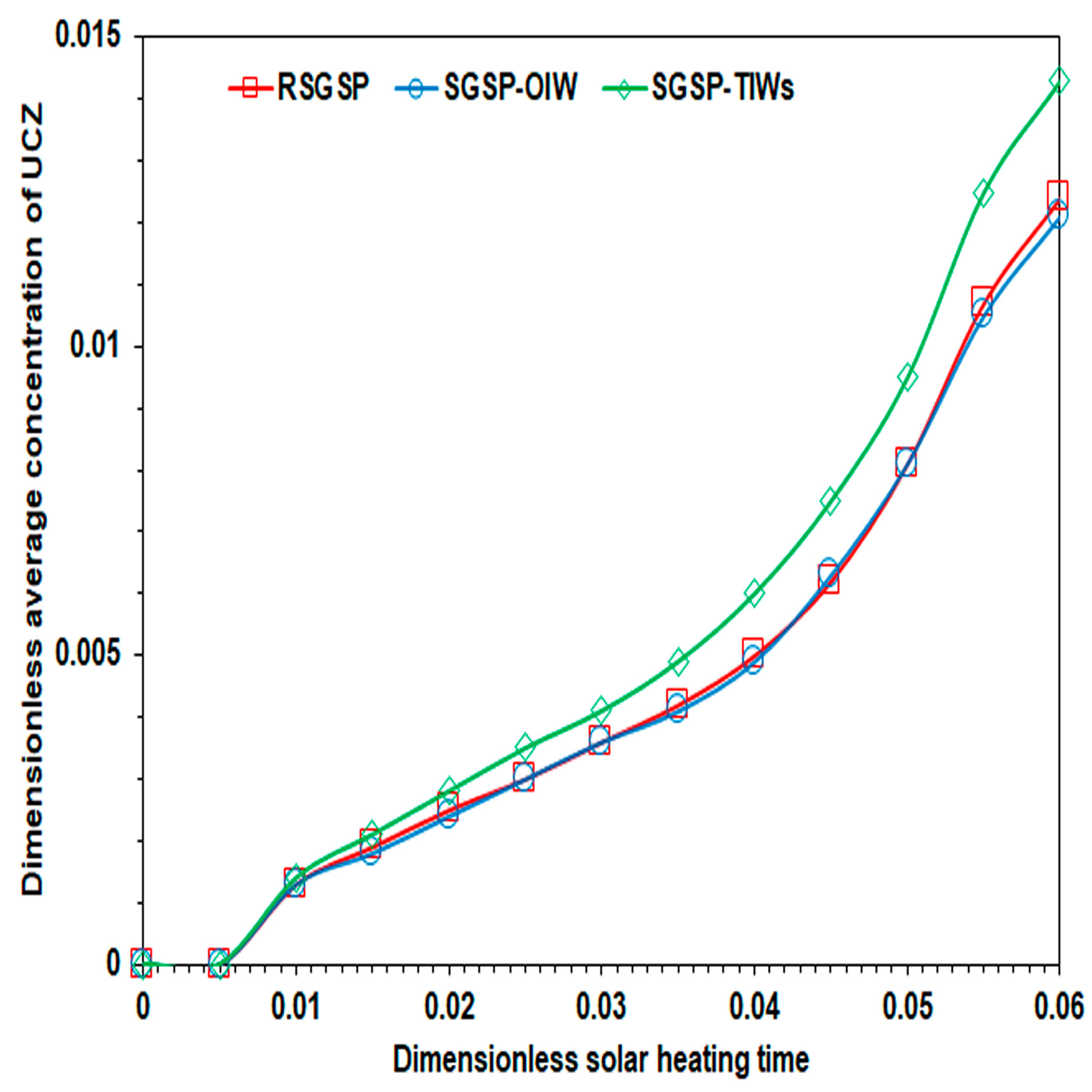

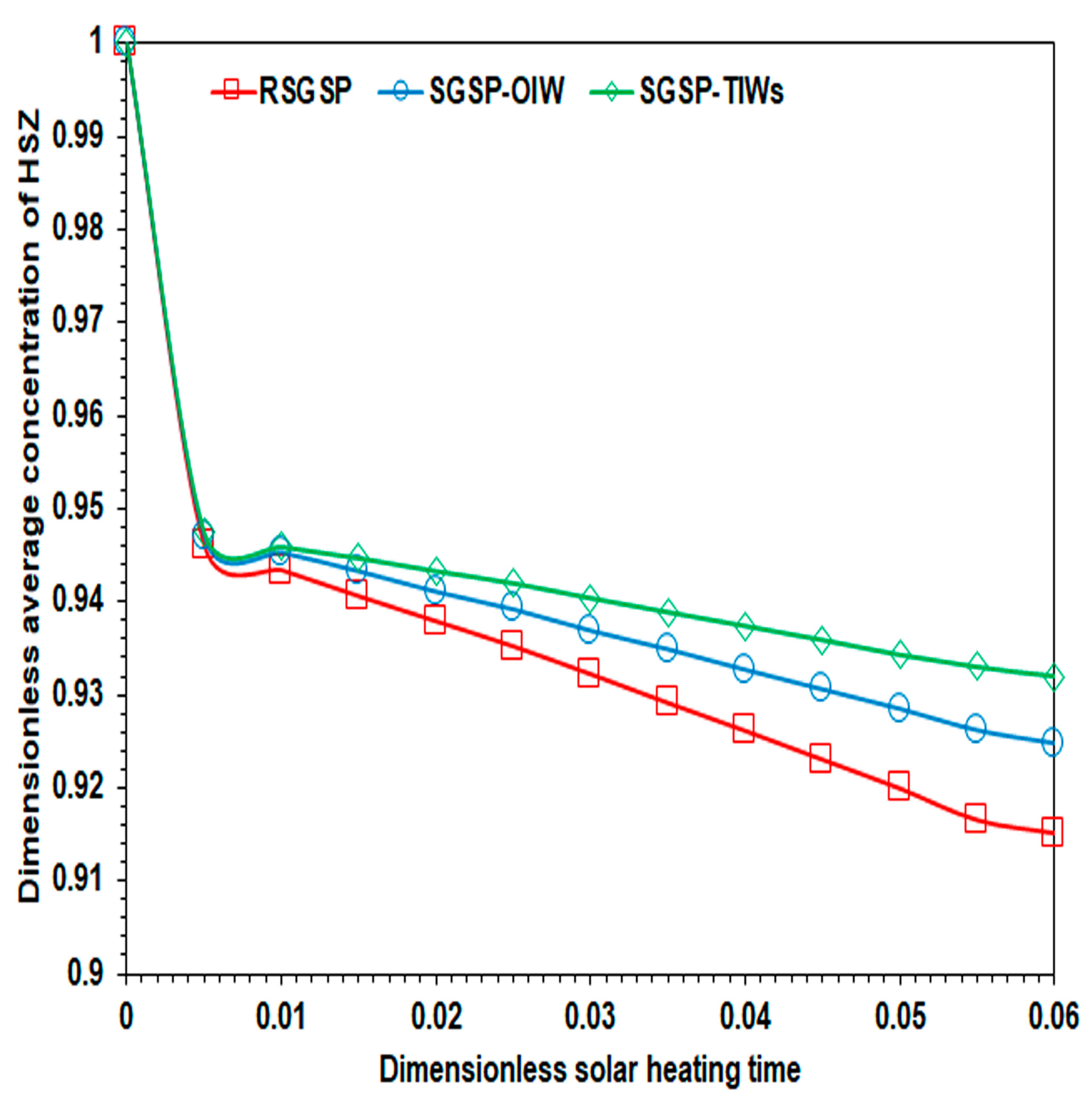

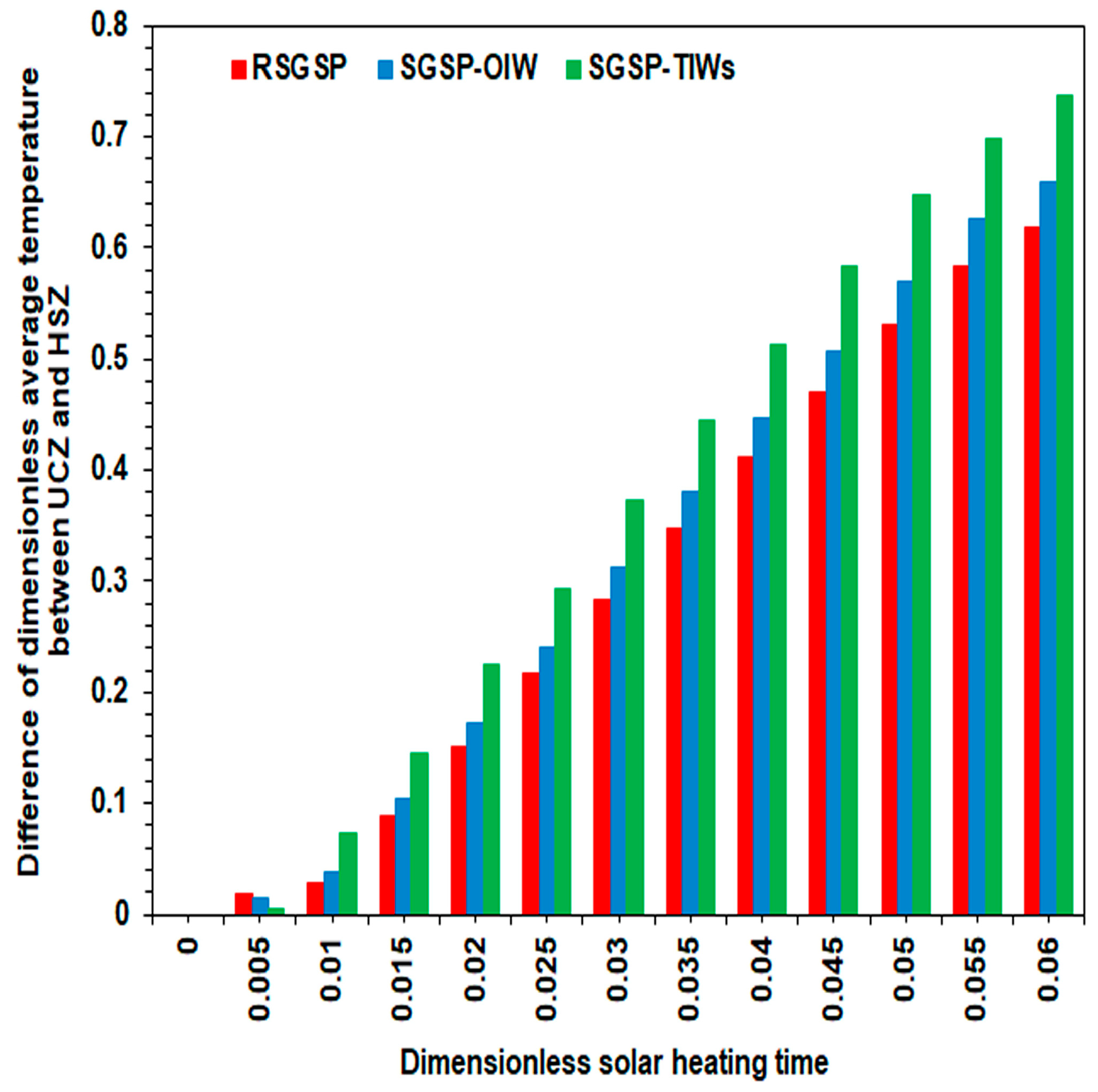

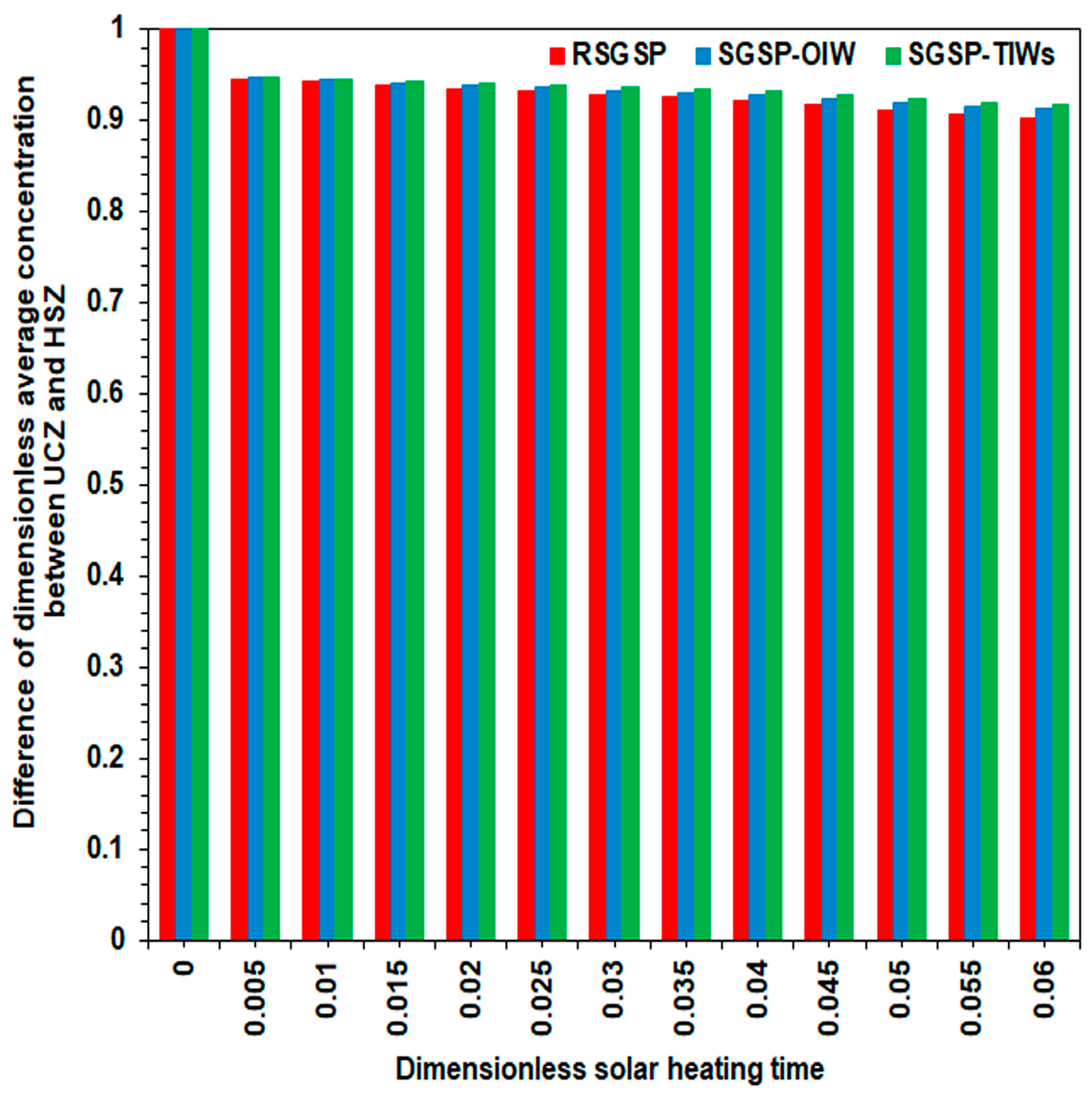

6.2. Time–Wise Evolution of the Dimensionless Average Temperature and Concentration

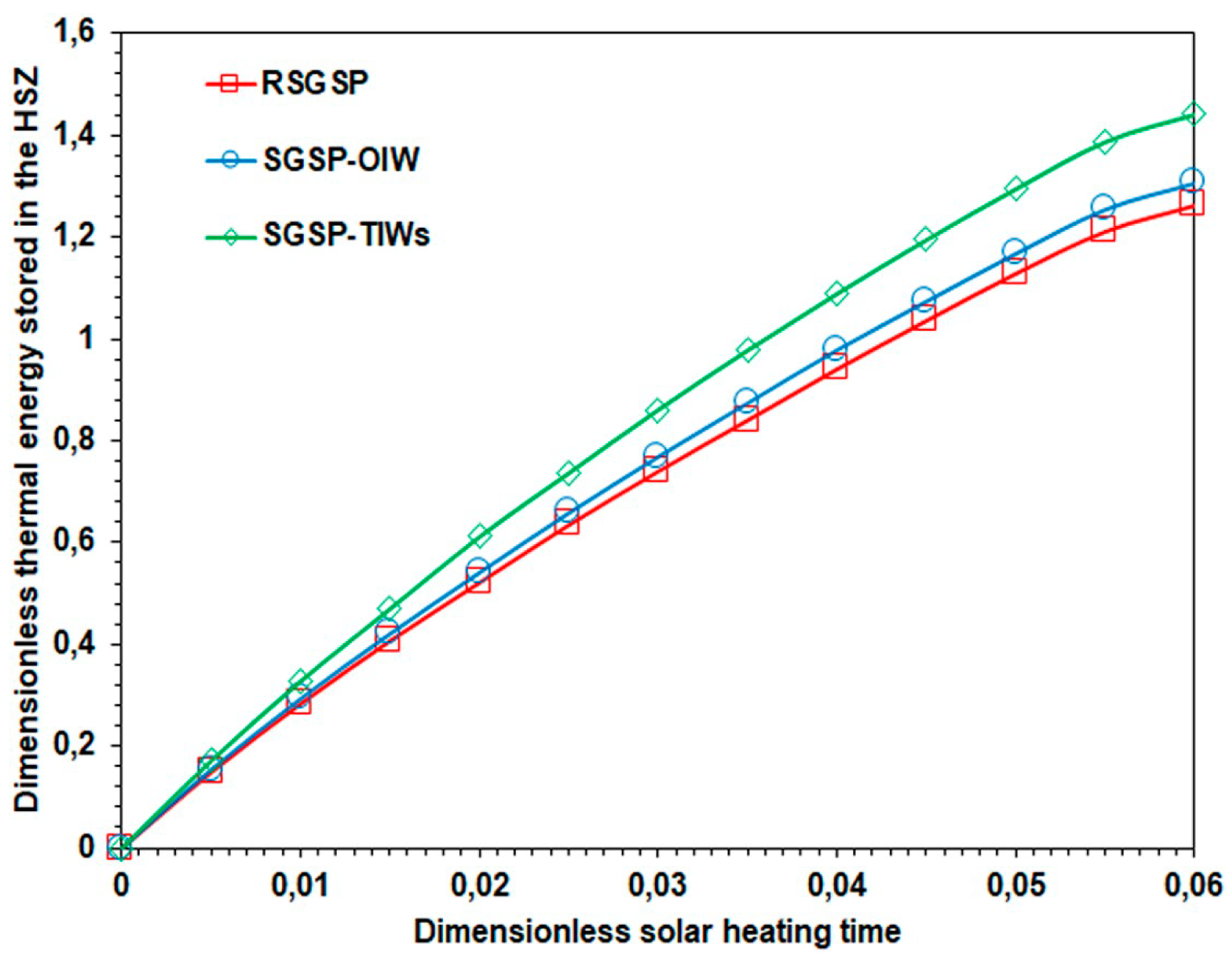

6.3. Time–Wise Evolution of the Dimensionless Thermal Energy Stored in the HSZ

7. Conclusions

Nomenclature

| Ar | aspect ratio = LH-1 |

| Br | buoyancy ratio = βCΔC/(βTΔT) |

| C | concentration of saline solution [kgm-3] |

| Cpa | air specific heat capacity [kJkg-1°C-1] |

| Cp | water specific heat capacity [kJkg-1°C-1] |

| ΔC | difference of concentration = Ch-Cl |

| D | diffusion coefficient [m2s-1] |

| Eth | thermal energy stored in the HSZ [J] |

| H | dimensional height of the pond [m] |

| hc | convective heat transfer coefficient [Wm-2°C-1] |

| L | pond’s length = 3H [m] |

| Le | Lewis number = α/D |

| Lv | latent heat of vaporization [Jkg-1] |

| m | mass of fluid [kg] |

| p | dimensional pressure [Pa] |

| P | dimensionless pressure = p/(ρ0α2/H2) |

| Ps | dimensional pressure of water vapor at the surface of the SGSP [Pa] |

| Pv | dimensional partial pressure of water vapor [Pa] |

| Patm | atmospheric pressure [Pa] |

| Pr | Prandtl number = ν/α |

| qc | convective heat losses [Wm-2] |

| qe | evaporative heat losses [Wm-2] |

| qr | radiative heat losses [Wm-2] |

| proportion of thermal energy generation per unit volume [Wm-3] | |

| q0 | intensity of solar radiation entering the top surface of SGSP [Wm-2] |

| q(z) | quantity of solar radiation at depth z [Wm-2] |

| RaE | external Rayleigh number = gβTΔTH3/(αν) |

| RaI | internal Rayleigh number = gβTq0H4/(λwαν) |

| RaIE | internal to external Rayleigh number = RaI/RaE |

| Rh | relative humidity |

| Sθ | dimensionless heat source term |

| Sc | Schmidt number |

| t | dimensional time of solar heating [s] |

| ΔT | difference of dimensional temperature = Th-Tl [°C or K] |

| T | dimensional temperature [°C] |

| Ts | dimensional temperature of the top surface of SGSP, [°C] |

| Ta | dimensional ambient temperature [°C] |

| Tsky | dimensional temperature of the sky [°C] |

| u, w | dimensional velocity components [ms-1] |

| U, W | dimensionless velocity components = (u, w)/(α/H) |

| V | dimensional average velocity of wind [ms-1] |

| x, z | dimensional horizontal and vertical axes, respectively [m] |

| X, Z | dimensionless horizontal and vertical axes, respectively, = (x, z)/H |

| ZHSZ | dimensionless depth of HSZ, |

| ZNCZ | dimensionless depth of NCZ, |

| Greek symbols | |

| α | thermal diffusivity [m2s-1] |

| β | angle of the sloped sidewall of the SGSP with the horizontal plan [degree] |

| βT | thermal expansion coefficient [K-1] |

| βC | concentration expansion coefficient [m3kg-1] |

| λw | thermal conductivity of water [Wm-1K-1] |

| ν | cinematic viscosity [m2s-1] |

| ρ | density [kgm-3] |

| ρr | reference density [kgm-3] |

| φ | dimensionless salt concentration = (C–Cl)/ΔC |

| Δ | difference of dimensionless average concentration = |

| θ | dimensionless temperature = (T–Ta)/ΔT |

| Δ | difference of dimensionless average temperature = |

| τ | dimensionless solar heating time = t/(H2/α) |

| μ | extinction coefficient of saltwater [m-1] |

| εw | emissivity of water |

| σ | Stefan–Boltzmann constant [Wm-2K-4] |

| Ψ | portion of intensity of solar radiation |

| Φ | dimensionless coefficient of solar radiation absorption = μH |

| Subscripts | |

| a | ambient |

| h | high value |

| l | low value |

| r | reference |

| th | thermal |

| * | dimensionless variable |

| Abbreviations | |

| HSZ | heat storage zone |

| NCZ | non–convective zone |

| OIW | one inclined wall |

| PCM | phase change material |

| RSGSP | rectangular salinity gradient solar pond |

| SGSP | salinity gradient solar pond |

| SGSP-OIW | salinity gradient solar pond with one inclined wall |

| SGSP-TIWs | salinity gradient solar pond with two inclined walls |

| TIWs | two inclined walls |

| UCZ | upper convective zone |

Appendix A

References

- M.R. Assari, H.B. Tabrizi, A.K. Nejad, M. Parvar. Experimental investigation of heat absorption of different solar pond shapes covered with glazing plastic. Sol. Energy 122 (2015) 569–578. [CrossRef]

- L. Hongsheng, J. Linsong, W. Dan, S. Wence. Experiment and simulation study of a trapezoidal salt gradient solar pond. Sol. Energy 122 (2015) 1225-1234. [CrossRef]

- A.A. Dehghan, A. Movahedi, M. Mazidi. Experimental investigation of energy and exergy performance of square and circular solar ponds. Sol. Energy 97 (2013) 273–284. [CrossRef]

- M. Khalilian. Experimental and numerical investigations of the thermal behavior of small solar ponds with wall shading effect. Sol. Energy 159 (2018) 55–65. [CrossRef]

- B.A. Jubran, H. Al-Abdali, S. Al-Hiddabi, H. Al-Hinai, Y. Zurigat. Numerical modelling of convective layers in solar ponds. Sol. Energy 77 (2004) 339–345. [CrossRef]

- A.H. Sayer, H. Al-Hussaini, A.N. Campbell. Experimental analysis of the temperature and concentration profiles in a salinity gradient solar pond with, and without a liquid cover to suppress evaporation. Sol. Energy 155 (2017) 1354–1365. [CrossRef]

- M. Ines, P. Paolo, F. Roberto, S. Mohamed. Experimental studies on the effect of using phase change material in a salinity-gradient solar pond under a solar simulator. Sol. Energy 186 (2019) 335–346. [CrossRef]

- J.A.G. Beik, M.R. Assari, H. Basirat Tabrizi. Transient modeling for the prediction of the temperature distribution with phase change material in a salt-gradient solar pond and comparison with experimental data. J. Energy Storage 26 (2019) 101011. [CrossRef]

- M.A. Al-Nimr, A.M.A. Al-Dafaie. Using nanofluids in enhancing the performance of a novel two-layer solar pond. Energy 68 (2014) 318-326. [CrossRef]

- P. Sarathkumar, A.R. Sivaram, R. Rajavel, R. Praveen Kumar, S.K. Krishnakumar. Experimental investigations on the performance of a solar pond by using encapsulated PCM with nanoparticles. Mater. Today Proc. 4 (2017) 2314-2322. [CrossRef]

- M.R. Assari, A.J.G. Beik, R. Eydi, H.B. Tabrizi. Thermal–salinity performance and stability analysis of the pilot salt–gradient solar ponds with phase change material. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 53 (2022) 102396. [CrossRef]

- M. Arulprakasajothi, R. Santhanakrishnan, A. Saranya, Y. Devarajan. Augmentation of heat storage capacity of compact salinity gradient solar pond using dragon fruit extract coated magnesium powder and paraffin wax. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 50 (2024) 102518. [CrossRef]

- M. Arulprakasajothi, N. Poyyamozhi, A. Saranya, K. Elangovan, Y. Devarajan, S. Murugapoopathi, K.T.T. Amesho. An experimental investigation on winter heat storage in compact salinity gradient solar ponds with silicon dioxide particulates infused paraffin wax. J. Energy Storage 82 (2024) 110503. [CrossRef]

- E. Farsijani, A. Shafizadeh, H. Mobli, A. Akbarzadeh, M. Tabatabaei, W. Peng,M. Aghbashlo. Enhanced performance and stability of a solar pond using an external heat exchanger filled with nano-phase change material. Energy 292 (2024) 130423. [CrossRef]

- N. Poyyamozhi, S.S. Kumar, R.A. Kumar, G. Soundararajan. An investigation into enhancing energy storage capacity of solar ponds integrated with nanoparticles through PCM coupling and RSM optimization. Renew. Energy 221 (2024) 119733. [CrossRef]

- K. Choubani, O. Ghriss, N.H. Alrasheedi, S. Dhaoui and A. Bouabidi. Experimental Investigation of a Phase-Change Material’s Stabilizing Role in a Pilot of Smart Salt-Gradient Solar Ponds. Frontiers Heat Mass Transfer 22 (1) (2024) 342-358. [CrossRef]

- H. Wang, C.Y. Zhang, L.G. Zhang. Effect of steel-wires and paraffin composite phase change materials on the heat exchange and exergetic performance of salt gradient solar pond. Energy Reports 8 (2022) 5678–5687. [CrossRef]

- D. Tian, Z.G. Qu, J.F. Zhang, Q.L. Ren. Enhancement of solar pond stability performance using an external magnetic field. Energy Conv. Manag. 243 (2021) 114427. [CrossRef]

- M.S. Sodha, N.D. Kaushika, S.K. Rao. Thermal analysis of three zones solar pond. Energy Res. 5 (1981) 321-40.

- S.V. Patankar. Numerical heat transfer and fluid flow. Washington: Hemisphere Publishing Corporation, 1980.

- R. Boudhiaf, M. Baccar. Transient hydrodynamic, heat and mass transfer in a salinity gradient solar pond: A numerical study. Energy Conv. Manag. 79 (2014) 568-580. [CrossRef]

- R. Boudhiaf, A.B. Moussa, M. Baccar. A two-dimensional numerical study of hydrodynamic, heat and mass transfer and stability in a salt gradient solar pond. Energies 5 (2012) 3986–4007. [CrossRef]

- H. Han, T.H. Kuehn. Double-diffusive natural convection in a vertical rectangular enclosure–II: Numerical study. Int. J. Heat Mass Trans. 34 (1991) 461–471.

- R. Boudhiaf. Numerical temperature and concentration distributions in an insulated salinity gradient solar pond. Renewables: Wind, Water, and Solar (2015) 2-10. [CrossRef]

- V.V.N. Kishore, V.A. Joshi. A practical collector efficiency equation for non-convecting solar ponds. Sol. Energy 33 (5) (1984) 391–395. [CrossRef]

- G.V. Parmelee, W.W. Anbele. Radiant energy emissions of atmosphere and ground. ASHVE Trans. (1952) 58-85.

- H. Kurt, F. Halici, A.K. Binark. Solar pond conception–experimental and theoretical studies. Energy Conver. Manag. 41 (9) (2000) 939-951. [CrossRef]

- H. Han, T.H. Kuehn. Double-diffusive natural convection in a vertical rectangular enclosure–I: experimental study. Int. J. Heat Mass Transfer 34 (2) (1991) 449–59.

- M. Corcione. Effects of the thermal boundary conditions at the sidewalls upon natural convection in rectangular enclosures heated from below and cooled from above. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 42 (2003) 199–208.

- F. Suarez, S.W. Tyler, A.E. Childress. A fully coupled, transient double-diffusive convective model for salt–gradient solar ponds. Int. J. Heat Mass Trans. 53 (2010) 1718-1730.

- J.A. Duffie, W.A. Beckman. Solar Engineering of Thermal Processes. John Wiley and Sons, 1980.

- M.R. Jaefarzadeh. Thermal behavior of a small salinity-gradient solar pond with wall shading effect. Sol. Energy 77 (2004) 281-290.

- M. Karakilcik, I. Dincer, I. Bozkurt, A. Atiz. Performance assessment of a solar pond with and without shading effect. Energy Conver. Manag. 65 (2013) 98-107. [CrossRef]

| i | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Ψ | 0.237 | 0.193 | 0.167 | 0.179 | 0.224 |

| Φ | 0.032 | 0.45 | 3 | 35 | 225 |

| Governing equations | F | SF | |

| Eq. (11) | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Eq. (12) | U | Pr | |

| Eq. (13) | W | Pr | |

| Eq. (14) | θ | 1 | |

| Eq. (15) | φ | 1/Le | 0 |

| Dimensionless shading area for D1 (or D2) | Dimensionless shading area for D3 | ||||

| 0.186 | 0.45 | 1.1 | 0.021 | 0.052 | 0.126 |

| Dimensionless parameter | Value |

| Ar | 3 |

| Br | 10 |

| RaIE | 14 |

| ZNCZ | 0.8 |

| ZHSZ | 0.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).