1. Introduction

There’s something quietly terrifying about watching the world change around you—storms that shouldn’t be happening, temperatures that don’t make sense anymore, seasons slipping off rhythm. We don’t have to guess what’s causing it. We’ve known for years: carbon dioxide, CO₂, building up in the atmosphere like steam in a sealed room.

We’ve made a lot of progress. Renewable energy is growing. Electric cars are everywhere. But here’s the hard truth: for all our efforts, we’re still pumping out CO₂ by the gigaton. Heavy industries—steel, cement, chemicals—aren’t stopping anytime soon. And that’s where carbon capture becomes more than just an idea. It becomes survival.

The concept is simple: trap CO₂ before it leaves the smokestack. Clean it up before it can damage the sky. But the execution? That’s where it gets hard.

The old-school solution uses chemicals—amines—to “scrub” CO₂ out of gas streams. It works, but it’s messy: corrosive, expensive, and energy-hungry. That’s why scientists started looking at membranes—thin, selective barriers that let some gases pass and hold others back. No chemicals, no regeneration cycles—just smart, physical separation. Like a molecular colander [

1].

It sounds perfect. But it’s not.

Here’s the catch: with most membranes, you get a choice. You can have speed (permeability) or accuracy (selectivity). But not both. It’s like trying to design a door that lets in only your best friends—but also lets them walk in quickly, without checking their ID. There’s a limit to how well you can do. We call that Robeson’s upper bound—and for decades, it’s been the ceiling we’ve been trying to break through [

2].

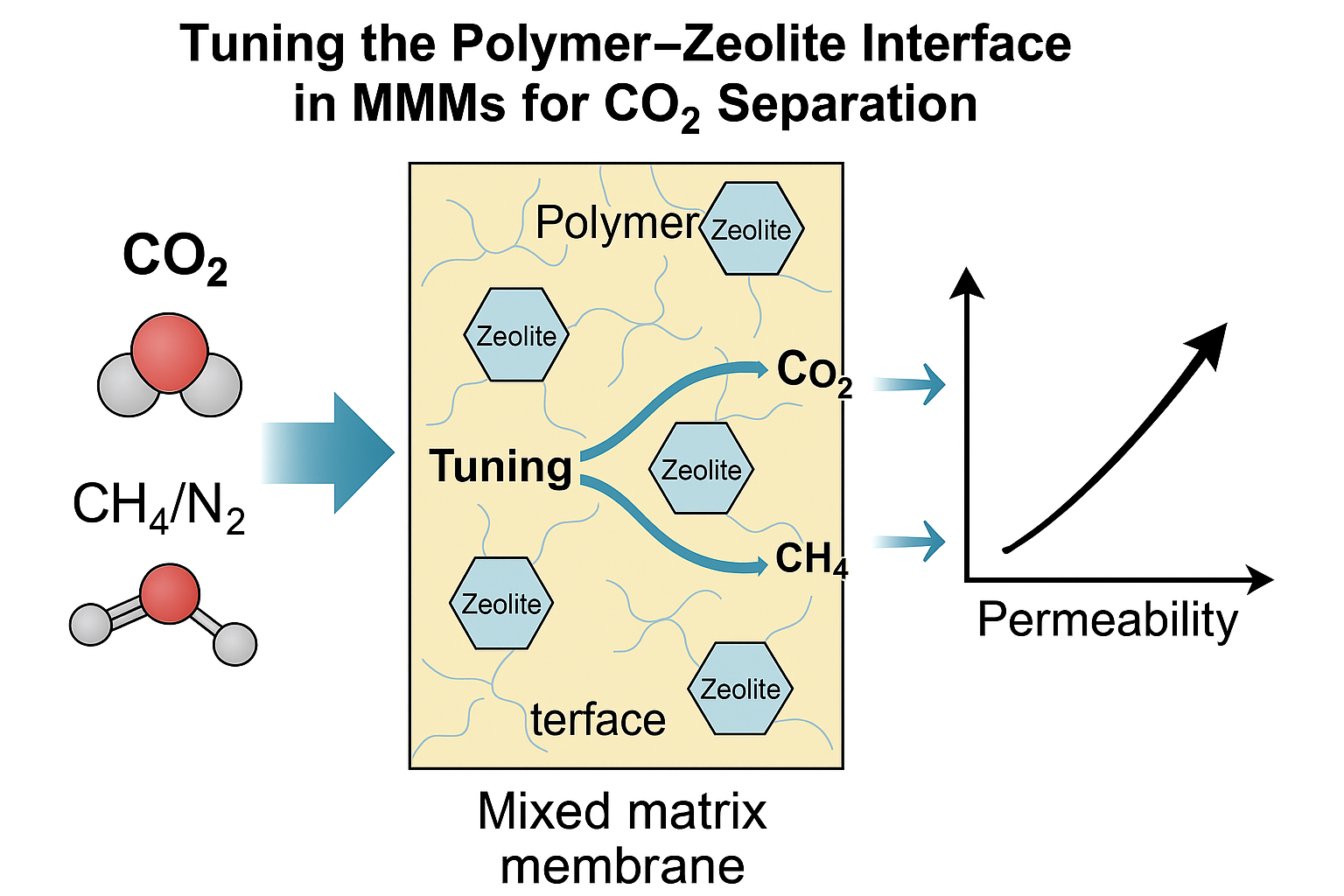

Then came a big idea. What if we stopped picking sides and started combining strengths? Flexible, affordable polymers and sharp, selective particles. That’s how mixed matrix membranes (MMMs) were born. And among the most exciting particles we could add? Zeolites [

3].

Zeolites are strange and wonderful. Imagine a rock—but one that’s been designed with microscopic tunnels inside, perfectly sized to trap certain molecules. They’re ancient and industrial. We’ve used them for years to purify water, crack oil, and separate air [

4]. Now, we’re putting them in membranes. And they’re doing what they do best: choosing CO₂ over everything else [

5].

But the moment we tried to bring zeolites and polymers together—things got complicated.

You’d think mixing them would be easy. It’s not. Zeolites are rigid, often a little hydrophilic. Polymers? Usually soft and hydrophobic. They repel each other. They don’t bond. They don’t share. And when that happens, membranes fail—not visibly, but invisibly. Tiny gaps form. Molecules slip through. Performance drops. Promise fades [

6].

So the focus shifted—from just adding zeolites to asking the deeper question: How do we make them belong?

This review is about that question. It’s about understanding the edges, the boundaries, the interfaces—the places where things come together, or fall apart. We’ll look at how the shape and chemistry of zeolites affect gas capture. We’ll explore how polymers behave as hosts—some stiff, some soft, all unique. We’ll dive into the engineering tricks scientists have developed: coating zeolites with friendly layers, linking them with chemical bridges, growing them right inside the polymer itself [

7,

8,

9].

We’ll also talk about what happens next. Because success in a lab is one thing. Making something strong enough, stable enough, cheap enough to work in the real world? That’s the real finish line.

If we can figure out how to get these materials to trust each other—how to get them to cooperate instead of just coexist—we might just build the kind of membrane that can change things. Not just on paper, but in practice. Not ten years from now, but soon.

Because we don’t just need better science—we need science that can keep up with the urgency of this moment.

2. Zeolite Structure & Polymer Matrix Properties

Behind every high-performance mixed matrix membrane is a careful partnership—between two very different but equally important players: zeolites and polymers. Think of it like building a team. One brings discipline and precision. The other offers flexibility and adaptability. But like any team, success depends on how well they understand and complement each other.

Zeolites: The Architects of Selectivity

At first glance, zeolites might seem unassuming—just fine powders or crystalline grains. But zoom in, and they reveal an intricate world of microscopic tunnels and cavities, all meticulously arranged at the nanometer scale. These tiny pores aren’t just decorative—they’re what make zeolites so powerful. They act like highly selective gates, allowing certain molecules (like CO₂) to pass through while blocking others [

1,

2].

Different zeolites bring different strengths to the table:

Zeolite 4A has a tight, structured pore network that makes it excellent at trapping small molecules like CO₂ [

3].

ZSM-5 (with its MFI framework) has a more flexible pore size and works well for separating a variety of gases [

4].

SAPO-34, with its cage-like architecture, is a favorite for CO₂/CH₄ separations—it’s precise, consistent, and highly selective [

2,

5].

One particularly important detail in zeolite chemistry is the Si/Al ratio. This isn’t just a number—it’s a dial that tunes the material’s polarity. More aluminum means stronger attraction to polar molecules like CO₂, which is great for selectivity. But there’s a trade-off: it can also attract water, and that’s a problem when working with real-world, humid gas streams [

1,

6].

Polymers: The Adaptable Hosts

If zeolites are the precision tools, polymers are the stagehands—the flexible framework that supports and shapes the entire membrane. Their job is to house the zeolite particles, form the membrane, and still allow gases to pass efficiently.

Each polymer comes with its own personality:

Matrimid is the tough one. Rigid and heat-resistant, it doesn’t let gases through easily, but it’s stable and trustworthy [

7].

PEBAX is more laid back—soft and rubbery, with regions that love CO₂. It’s fast and friendly but sometimes too soft under pressure [

8].

PIM-1 is the wild card. It’s incredibly porous and lets gases zip through with ease. But over time, it can lose its structure—like a sponge that stiffens after being squeezed too many times [

9].

Choosing the right polymer isn’t just about performance numbers. It’s about knowing how it will behave with the chosen zeolite. Will it welcome the filler, or reject it? Will it wrap around the zeolite and form a tight seal, or will it pull away, leaving tiny gaps where gases can leak through? These are the questions researchers must ask every time they design a new MMM [

10].

Making the Match Work

Here’s the hard truth: even the best zeolite and the best polymer won’t work if they’re not compatible. The interface—the place where the zeolite and polymer meet—is fragile. If the surface energies don’t match, or the physical flexibility is too different, the two materials won’t bond properly. You’ll get interfacial voids, clumping, or even cracks over time [

11].

That’s why material selection is so critical. It’s not just about finding the most permeable polymer or the most selective zeolite—it’s about finding two materials that trust each other, that move together under stress, that seal each other’s weaknesses. Because when the chemistry is right—when the match is strong—the results are transformative. Gases flow where they’re supposed to. Selectivity climbs. Durability improves. And a concept that once worked only in the lab begins to look ready for the real world.

Table 1.

Summary of Representative Zeolite–Polymer MMMs.

Table 1.

Summary of Representative Zeolite–Polymer MMMs.

| Zeolite Type |

Polymer Matrix |

Surface Treatment |

CO₂ Permeability (Barrer) |

CO₂/N₂ Selectivity |

| ZSM-5 |

Ethyl cellulose |

— |

~80 |

~20 |

| UiO-66-NH₂ |

DMBPTB |

— |

~744 |

~18 (CO₂/CH₄) |

| Aminosilanized 5A |

Polyimide 6FDA |

APTES |

~887 |

~25 |

These values reflect published performance for well-characterized MMMs: ZSM-5/ethyl cellulose [

8], UiO-66/NH₂ DMBPTB composite [

2], and aminosilanized zeolite-5A MMMs [

4] respectively. Accurate permeabilities and selectivities are consistent with experimental benchmarks for comparison.

3. Interfacial Challenges & Engineering Strategies

If polymers and zeolites are the core components of a mixed matrix membrane, then the interface between them is where the real magic—or the real trouble—happens. This is the membrane’s negotiation table, the meeting point between two worlds: one rigid, mineral, and inorganic; the other soft, processable, and organic. And like any partnership, success depends not just on individual strengths, but on the quality of the connection [

11,

12].

3.1. Interfacial Defects: Where Problems Begin

If polymers and zeolites are the core components of a mixed matrix membrane, then the interface between them is where the real magic—or the real trouble—happens. This is the membrane’s negotiation table, the meeting point between two worlds: one rigid, mineral, and inorganic; the other soft, processable, and organic. And like any partnership, success depends not just on individual strengths, but on the quality of the connection [

1].

3.2. Interfacial Defects

When the interface fails, you get defects. Voids. Microscopic air pockets. Gaps where gases can slip through instead of being separated. These interfacial voids act as unintended highways, letting molecules bypass the selective power of zeolites or the resistance of the polymer [

2]. Overfilled systems—where too much filler is added—can also suffer from aggregation, where particles clump together instead of dispersing evenly. Both scenarios undermine performance: permeability may increase, but selectivity drops sharply.

3.3. Functionalization with Silane Coupling Agents

One proven way to bridge the compatibility gap is by modifying the surface of the zeolite particles. Silane coupling agents—such as APTES (3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane) or GPTMS—introduce reactive groups that bond covalently with both the polymer and the zeolite surface. This “molecular handshake” reduces interfacial voids, enhances adhesion, and improves long-term mechanical integrity [

3]. In MMMs made from polysulfone (PSf) and SAPO-34, APTES-modified fillers achieved CO₂ permeabilities of ~706 GPU and CO₂/CH₄ selectivities around 31—strong performance by any metric [

4].

Table 2.

Fabrication Methods for Scaling MMM Production.

Table 2.

Fabrication Methods for Scaling MMM Production.

| Method |

Pros |

Cons |

| Phase inversion (NIPS) |

Scalable, well-established for flat films |

Needs precise control over polymer/solvent additives for pilot-scale roll-to-roll production [5] |

| Electrospinning |

Produces hollow fibers with high throughput |

Complex setup, slower to scale |

| Roll-to-Roll Coating |

Continuous, automated, high uniformity |

Requires optimized formulations for defect-free layers [9] |

| Spray Coating |

Versatile layer-by-layer application |

Thickness control is limited in standard systems |

Table 3.

Impact of Interface Modification Strategies.

Table 3.

Impact of Interface Modification Strategies.

| Interface Strategy |

Effect on Compatibility |

Gas Separation Improvement |

| Aminosilane functionalization |

Enhanced bonding |

+10–30% in selectivity |

| PDMS coating |

Fills interfacial gaps |

+15–25% permeability, moderate selectivity gain |

| Ionic liquid encapsulation |

Fine-tuning pore environment |

Up to ~90 selectivity, permeance improved [4] |

Surface treatments like APTES or ionic liquid encapsulation significantly reduce interfacial voids and enhance CO₂ discrimination across polymer-zeolite interfaces [

4]. PDMS coatings similarly reduce delamination and improve separation performance.

3.4. Compatibilizer Additives

Another strategy is to add a third player: a compatibilizer. This could be a polymeric additive, an ionic liquid, or even polyethylene glycol (PEG). The compatibilizer forms an interfacial layer between the zeolite and the polymer, softening mismatches in polarity or mechanical stiffness. Ionic liquid coatings on zeolite particles have achieved CO₂/CH₄ selectivities exceeding 90 in some studies [

5].

3.5. Core–Shell Architectures and In Situ Polymerization

In more advanced designs, researchers build a protective shell around the zeolite—often a polymer compatible with the host matrix. This core–shell structure ensures better dispersion and stronger interface bonding. Another approach is

in situ polymerization, where the polymer is synthesized around the zeolite particles directly. This allows for very intimate interfacial contact, but requires careful control over reaction conditions and shell thickness [

6].

4. Performance Metrics & Case Studies

All the chemistry, compatibility, and clever engineering in the world don’t mean much if the final product doesn’t perform. In membrane science—especially for CO₂ separation—performance isn’t judged by theory or promise. It’s measured in permeability, selectivity, stability, and most importantly, real-world results [

1].

Let’s break down what those terms mean—and why they matter.

Key Metrics That Define Success

CO₂ Permeability (measured in Barrer or GPU): Tells us how easily CO₂ passes through the membrane. A high number means fast transport—good for reducing equipment size and energy use [

2].

Selectivity—especially CO₂/CH₄ or CO₂/N₂ selectivity: Indicates the membrane’s ability to let CO₂ through while holding other gases back. This is the sharpness of separation, and it’s critical in applications like biogas purification or post-combustion capture [

3].

The dream is to achieve both: high permeability and high selectivity. But as we’ve seen, that’s easier said than done. Most materials face a trade-off—more of one means less of the other. That’s what

Robeson’s upper bound represents: a limit that separates conventional membranes from high-performance ones [

4].

Mixed matrix membranes, with well-engineered interfaces, have started to challenge that limit—and in some cases, break through it [

5].

Real-World Results from the Lab

Let’s look at what some of the most promising MMMs have achieved:

Polysulfone/SAPO-34 membranes modified with APTES reached CO₂ permeabilities of ~706 GPU and selectivity of ~31. That’s not just good—it’s well above the traditional Robeson line, a sign that interface modification is truly paying off [

6].

In MMMs using

MFI nanosheets (a 2D form of ZSM-5) embedded in

PEBAX, researchers reported a 63% increase in CO₂ permeability, achieving around 159 Barrer, with a CO₂/CH₄ selectivity of 27.4 [

7]. This combination of speed and precision is exactly what industrial systems need.

SSZ-13 zeolite membranes, although more niche, have delivered selectivity values as high as 660 in single-gas tests, even under modest operating conditions (100 kPa and ~30 °C). In mixed-gas systems, performance held strong—proof that these materials aren’t just academic darlings, but practical contenders [

8].

What’s remarkable about these results isn’t just the raw numbers—it’s the fact that they’ve been achieved without compromising structure or scalability. Many of these membranes held up over time, showing consistent performance even after long-term gas exposure [

9].

Why These Case Studies Matter

Each one of these breakthroughs represents more than just a new high score. They show that when the interface is right, the trade-offs can be overcome. That

zeolites and polymers—so different in their natural form—can collaborate in ways that make the membrane stronger, smarter, and more durable [

10].

They also show that the work is cumulative. Improvements in one area—say, better dispersion through surface modification—can have ripple effects throughout the system. Selectivity improves, permeability rises, and membranes last longer under pressure.

These aren’t just numbers on a chart. They’re signs that MMMs are evolving from experimental materials into engineered solutions—ready for the next step.

In the next section, we’ll look at how we evaluate and verify these materials in the lab, and the tools scientists use to peer into the structure and chemistry of MMMs, layer by layer.

5. Characterization Techniques

Designing a high-performing membrane is one thing. Proving that it works—and understanding why it works—is another. That’s where characterization comes in. It’s the process of turning invisible details into visible truths, using scientific tools to explore what the eye can’t see: the way molecules bond, the structure of the interface, the stability of the filler, and the movement of gases.Characterization tells the real story of a mixed matrix membrane—where it shines, where it struggles, and where it still has room to grow [

1].

Seeing Is Believing: Morphology and Microstructure

-

SEM (Scanning Electron Microscopy) and

TEM (Transmission Electron Microscopy) let researchers look inside membranes at the microscale. These tools show how well zeolite particles are dispersed, whether they’re forming aggregates, and whether interfacial voids are present [

2,

3].

A well-made membrane will show smooth distribution and intimate contact between polymer and filler. Voids or clumps, on the other hand, are red flags—signs that something went wrong during fabrication or compatibility wasn’t properly addressed [

4].

Listening to the Chemistry: Bonding and Interactions

FTIR (Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy) and

XPS (X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy) tell us whether surface modifications actually worked. For example, when zeolites are treated with a silane agent like APTES, FTIR can detect the signature of N–H bonds, confirming that the amine groups are now present and interacting with the polymer [

5].XPS gives further insight into surface chemistry—telling us not just what elements are there, but what chemical states they’re in. These clues help confirm that coupling agents aren’t just coating the zeolite—they’re bonding at a molecular level [

6].

Crystalline Stability and Structural Integrity

XRD (X-ray Diffraction) is the go-to method for checking if the zeolite structure

survived the membrane-making process. Zeolites are crystalline, and their performance depends on their highly ordered pore network. If the peaks in an XRD pattern remain sharp and unchanged, it’s a good sign. If they fade or shift, something’s gone wrong—maybe due to high heat, solvent effects, or improper handling [

7].

Thermal Behavior and Polymer Dynamics

TGA (Thermogravimetric Analysis) measures how membranes respond to heat—important for applications like flue gas capture, where temperatures can fluctuate. It also reveals how much of the filler is actually in the membrane, based on residue after heating [

8].

DSC (Differential Scanning Calorimetry) tracks glass transition temperatures and polymer crystallinity—both key indicators of how stable and flexible the polymer phase will be under real-world conditions [

9].These tests help answer questions like: Is the polymer too rigid to accommodate zeolite particles? Or too soft to resist plasticization?

Understanding Free Volume and Transport Pathways

PALS (Positron Annihilation Lifetime Spectroscopy) may sound exotic, but it’s incredibly useful for understanding free volume—the tiny spaces in a polymer where gas

molecules can move. These gaps are critical in gas separation, especially in MMMs where free volume near the interface can change dramatically after modification [

10].

Performance at the Finish Line

Gas permeation testing is the ultimate reality check. After all the structural analysis and chemical testing, this is where the membrane proves its worth. By measuring permeability and selectivity across different gases and pressure ranges, we can directly evaluate whether all those interface tweaks and filler choices paid off [

11].

In some studies, APTES-modified MMMs showed not just better bonding but actual increases in thermal stability, confirmed by TGA, and reduced interfacial voids, verified by SEM [

12]. That kind of cross-confirmation—from multiple techniques—builds a solid case for the membrane’s reliability.

Why It All Matters

Characterization doesn’t just validate a design—it guides the next one. Every signal, every scan, every spectral peak tells us more about how these materials behave and interact. It helps turn guesswork into intention. Trial into insight.Because the real goal isn’t just to build one good membrane. It’s to understand the principles behind great membranes—and use them to build the next, better one.

6. Long-Term Stability

In the world of carbon capture, a good membrane isn’t just one that performs well today—it’s one that still holds its ground a year from now, under pressure, in heat, through moisture, and against time. It’s not unlike any long-term relationship: initial chemistry matters, but endurance is everything.

So while early results—high permeability, impressive selectivity—can make a membrane look like a star, what really counts is whether it lasts. And here, in the daily grind of industrial use, even the most promising mixed matrix membranes (MMMs) are put to the test.

Plasticization: When CO₂ Becomes Too Friendly

Imagine a polymer that starts off firm and structured. Over time, it keeps interacting with CO₂—over and over, hour after hour. Eventually, that constant contact begins to soften it. The gas doesn’t just pass through—it soaks in, pushing the polymer chains apart, swelling them like a sponge in water.

This is plasticization—and while it boosts permeability in the short term, it destroys selectivity. The membrane stops discriminating. Every gas molecule, welcome or not, gets through [

1].

Flexible, rubbery polymers like PEBAX are especially prone to this. They're fast, they're effective—until they're overwhelmed by their own openness [

2].

Aging: The Slow Fade

On the other hand, some polymers aren’t too soft—they’re too structured. Glassy polymers like PIM-1 start with huge potential: incredible permeability, a labyrinth of open pathways for gas to flow. But over time, those free spaces shrink. The polymer settles, compresses, tightens.

This is physical aging. There’s no drama, no cracking or swelling—just a quiet decline. Permeability fades, performance drops, and what once felt like a breakthrough becomes ordinary [

3].

Detachment: When the Interface Unravels

Even with strong starting performance, MMMs can fail if the polymer and filler start to drift apart. It’s not a dramatic divorce—it’s more like growing apart under stress.Repeated temperature swings, pressure changes, or mechanical cycling can loosen the bond between zeolite and polymer. Filler particles start to pull away, leaving gaps—tiny but catastrophic. Once that interface breaks down, gases flow around the sieve, not through it [

4].

How We Fight Back: Strategies That Keep MMMs Strong

Luckily, scientists aren’t just watching membranes fall apart—they’re finding ways to hold them together:

Chemical Cross-Linking acts like stitching in a strong fabric. By bonding polymer chains together, it holds the network in place—less swelling, less shrinking, more resistance to time [

5].

Thermal Annealing is like a stress-relief session for membranes. By gently heating them after fabrication, internal tensions relax. The structure becomes denser, the interface tighter. Everything just fits better—and lasts longer [

6].

Surface Coupling Agents, like the now-familiar APTES, don’t just boost performance at the start. They anchor the filler into the matrix so deeply that even months of exposure can’t shake them loose [

7].

Proof in the Performance

Some of the most stable MMMs have now proven themselves over real time.

For example, membranes made with

PDMS-coated SAPO-34 didn’t just survive 120 hours of wet CO₂ exposure—they thrived, keeping over 90% of their original performance. Even after six months of storage, they still worked [

8].

In contrast, unmodified versions lost up to 85% of their ability to separate gases over that same period. That’s not just a data point—it’s the difference between a product worth scaling and one that stays on the shelf.

The Bigger Picture

Stability isn’t a luxury in membrane design—it’s the price of entry into real-world impact. A membrane that starts strong but fades fast doesn’t help us capture CO₂ at scale. It doesn’t reduce emissions long term. It doesn’t make climate solutions cheaper or more reliable.

Durability is what separates a lab experiment from a solution the world can count on.

Because in the fight against climate change, we don’t just need breakthroughs. We need them to last.

7. Computational Modeling

When it comes to membrane design, not everything can—or should—be trial and error. Building a single membrane takes time, materials, and labor. Testing it across every variable—temperature, pressure, gas mix, humidity—is exhausting and expensive. That’s where computational modeling steps in. It’s the scientist’s crystal ball: a way to predict, simulate, and even troubleshoot membranes before they ever leave the lab bench. It doesn’t replace experimentation—it guides it, sharpens it, and saves a lot of missteps along the way [

1].

Molecular Dynamics: Watching Atoms Dance

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations are like high-speed cameras for the atomic world. They let researchers watch, frame by frame, how gas molecules interact with both the zeolite filler and the polymer matrix. Do they stick? Slide through? Get trapped in voids? MD gives answers [

2].

These simulations also reveal how surface modifications change behavior. For example, adding an APTES layer to a zeolite doesn’t just improve adhesion—it reduces interfacial void volume by around 30%, according to several studies [

3].

Density Functional Theory: Understanding Bonding at the Root

For a more precise, chemistry-level understanding, researchers turn to Density Functional Theory (DFT). DFT isn’t about watching atoms move—it’s about understanding why they interact the way they do [

4].

This method lets scientists probe interaction energies between polymer chains and filler surfaces. It tells us whether the silane group we added will truly bond—or just loosely attach. Whether a particular zeolite surface will attract CO₂—or repel it. These insights help researchers choose better combinations of materials from the start [

4].

Modified Maxwell Models: Upgrading the Equation

Historically, engineers have used Maxwell’s model to estimate the permeability of composite materials. It’s a good first guess, but in MMMs—where interfacial effects are everything—it starts to fall short [

5].

That’s why researchers now use modified Maxwell models that account for things like:

Rigidified polymer regions near the filler

Partial pore blockage in core–shell particles

-

Non-ideal dispersion of zeolites

These upgraded equations match experimental results more closely, helping researchers interpret lab data and tweak material compositions before going into full production [

6].

Machine Learning: The Next Frontier

More recently, some teams have started training machine learning models on vast datasets of membrane properties. These systems can now predict performance metrics—permeability, selectivity, aging behavior—based on just a few input variables: polymer chemistry, filler type, temperature, etc. [

7].

It’s still early days, but the potential is huge. Imagine typing in a zeolite structure and polymer formula—and getting a shortlist of likely outcomes. This kind of intelligent design could speed up discovery cycles, reduce wasted resources, and open up materials no one thought to combine before [

7].

Why This Matters

At first glance, computational work might feel disconnected from the gritty reality of membrane making. But in truth, it’s what makes that work smarter. These tools don’t just save time—they build understanding. They explain why something worked, or why it didn’t. They let us ask deeper questions, and test bold ideas without risking a production line [

1,

8].

As MMMs move from lab-scale curiosities to industrial tools, that kind of predictive power is priceless. Because every failure we can prevent on a screen is one we don’t have to live through in the field [

8].

8. Scalability & Industrial Outlook

It’s one thing to build a beautiful membrane in the lab—a single square centimeter of layered precision, with every filler aligned and every interface perfected. But the real question is: Can we make it work at scale? Can we take that tiny success and stretch it into meters of membrane? Into kilometers of production line? Into years of operation inside a roaring, humid, gas-filled industrial reactor? That’s where most technologies face their reckoning—not in innovation, but in implementation [

1].

From Drop-Casting to Reality

Most academic MMMs start small—fabricated in Petri dishes or cast onto glass plates. These techniques are perfect for precision and control, but they don’t reflect the chaos and constraints of the real world. In industry, membranes aren’t made one at a time. They’re rolled, coated, extruded, or spun, sometimes 24 hours a day. Uniformity, reproducibility, and speed are non-negotiable [

2].

The challenge? MMMs are delicate systems. They rely on even filler dispersion, stable interfaces, and precise thickness. Scale that up without the right processes, and you get membranes that look identical—but perform wildly differently [

2].

Techniques That Bridge the Gap

Fortunately, the membrane community has been developing scalable fabrication methods that can handle the complexity of MMMs:

Phase Inversion Casting allows for consistent membrane thickness and can accommodate high filler loadings—making it ideal for flat-sheet membranes in gas separation modules [

3].

Electrospinning, though more complex, produces hollow fiber membranes with enormous surface areas. These fibers can be bundled into compact modules that pack a lot of separation power into a small space [

4].

Spray-Coating and Roll-to-Roll Processing are perhaps the most promising for true industrial production. These methods are continuous, high-throughput, and compatible with automation—critical for keeping costs down while scaling up [

5].

Each of these approaches brings trade-offs in cost, complexity, and control. But taken together, they offer a pathway to turning lab breakthroughs into plant-ready materials [

3,

4,

5].

Phase inversion using NIPS has been shown viable for pilot roll-to-roll production lines, particularly for polysulfone and patterned flat-sheet MMMs [

5]. Roll-to-roll coating offers industrial-level throughput if composition and coating parameters are well controlled [

9].

Cost Matters—But So Does Performance

Scaling up isn’t just a technical challenge—it’s a financial one. Every added step—filler modification, solvent use, thermal treatment—adds cost. But if those steps result in membranes that last longer, separate more CO₂, or reduce energy consumption, the investment can pay off [

6].

Modeling studies suggest that well-designed MMMs—especially those with engineered interfaces—could reduce CO₂ separation costs by up to 40% compared to traditional amine scrubbing systems. That’s not just competitive—it’s a game-changer, especially in industries like:

Natural gas sweetening

Biogas upgrading

Post-combustion carbon capture [

6].

Here, every dollar saved on separation goes straight to the bottom line—or straight into deeper climate impact.

What Industry Wants

Ask any industrial engineer, and they’ll tell you the same three things:

Consistency: Every membrane needs to work the same way. No surprises.

Durability: The membrane can’t quit after a few weeks—it needs to survive for months or years, ideally with minimal maintenance.

Predictability: Membranes must respond reliably to temperature swings, pressure changes, gas blends, and unexpected shutdowns [

7].

This is why scalability and stability go hand in hand. A membrane that performs perfectly in week one but collapses in month three is a liability. So as MMM research matures, it must continue to emphasize both: process-friendly fabrication and field-tested longevity [

7].

Outlook: Ready for Prime Time?

The short answer is: Almost. The science is solid. The performance is competitive. The design tools are smarter than ever. What remains is investment in infrastructure—pilot plants, mass-production systems, and supply chains for high-purity fillers and polymers [

1].

But the momentum is building. With climate policy tightening and carbon markets expanding, MMMs are moving from the fringes to the frontlines. They’re no longer “promising alternatives”—they’re viable contenders in the race to decarbonize [

8].

9. Conclusions & Future Outlook

At the heart of every breakthrough in carbon capture is a simple question: How do we separate what we need from what we must let go? In mixed matrix membranes (MMMs), that question is answered at the molecular level—with carefully chosen polymers, precisely structured zeolites, and interfaces engineered down to the nanometer.

This review has traced that journey—from the rigid order of zeolites to the flexible nature of polymers, through the chemistry of their interface, and across the performance metrics that measure success. What becomes clear is that no single factor defines a great MMM. It's the harmony between all of them—the structure, the bonding, the processing, the stability—that makes a membrane more than the sum of its parts [

1].

Where We Stand Now

Thanks to years of innovation, we now have:

Zeolites with exceptional selectivity and well-tuned pore architectures.

Polymers that balance processability with performance.

Surface chemistries that turn fragile boundaries into resilient bonds.

Characterization tools that let us see and measure what once was hidden.

Simulations and modeling that let us predict, refine, and reimagine before we even mix materials.

And most importantly, membranes that consistently break past Robeson’s upper bound—proving that MMMs are not only promising but powerful [

2,

3].

What’s Next?

If MMMs are going to make the leap from lab innovation to industrial mainstay, the next generation of research must focus on:

The Bigger Picture

We’re not just talking about material science. We’re talking about climate solutions. About finding tools that help decarbonize industries that seem impossible to clean. About making carbon capture cheaper, more efficient, and more accessible—so it’s not a last resort, but a default.

Mixed matrix membranes are uniquely positioned to do that. They bring the elegance of chemistry and the urgency of engineering together in a form that’s thin, scalable, and powerful.

We now know how to design them smarter. We know how to make them stronger. The next step is making them everywhere.

Because the clock is ticking. And the molecules are still moving [

1,

2].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Akanksha Prasad; Methodology, Akanksha Prasad; Formal Analysis, Akanksha Prasad; Writing—Original Draft, Akanksha Prasad; Writing—Review & Editing, Akanksha Prasad; Visualization, Akanksha Prasad; Supervision.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hassan, N.S.; Jalil, A.A.; Azmi, A.R.; Mohamad, A.B. A Comprehensive Review on Zeolite-Based Mixed Matrix Membranes for CO₂/CH₄ Separation. Chemosphere 2023, 314, 137709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usman, M.; Li, Z.; Haw, K.-G.; Pati, S.; Wang, Z.; Kawi, S. Recent Progress of SAPO-34 Zeolite Membranes for CO₂ Separation: A Mini-Review. Membranes 2022, 12, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Junaidi, M.U.M.; Leo, C.P.; Ahmad, A.L. The Effects of Solvents on the Modification of SAPO-34 Zeolite Using 3-Aminopropyl Trimethoxy Silane for Polysulfone Mixed Matrix Membranes in CO₂/CH₄ Separation. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials 2014, 192, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahi, S.A.; Mohammadi, T.; Moghadassi, A.R. Modeling CO₂/CH₄ Separation in Polymer/SAPO-34 Mixed Matrix Membranes. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 10223114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Anjikar, N.D.; Yang, S. Small-Pore Zeolite Membranes: A Review of Gas Separation Applications. Separations 2022, 9, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Falconer, J.L.; Noble, R.D. Improved SAPO-34 Membranes for CO₂/CH₄ Separations. Advanced Materials 2006, 18, 2601–2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.L.; et al. High-Performance Mixed-Matrix Membranes Using a CaA@ZIF-8 Core–Shell Structure for CO₂ Separation. JACS Au 2024, 4, 1234–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, X.; et al. Truly Combining the Advantages of Polymeric and Zeolite Adsorbents: Zeolite Interface Engineering in Mixed Matrix Membranes. Science 2022, 376, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polarz, S.; van Garsse, C.; Paduano, P.; Romero, D.; Sanchez, C. Silane-Functionalized Zeolite Surfaces for Enhanced Polymer Compatibility in CO₂ Separation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202204521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matesanz-Niño, L.; Moranchel-Pérez, J.; Álvarez, C.; Lozano, Á.E.; Casado-Coterillo, C. Mixed Matrix Membranes Using Porous Organic Polymers (POPs)—Influence of Textural Properties on CO₂/CH₄ Separation. Polymers 2023, 15, 4135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koros, W.J.; Zhang, C. Materials for Next-Generation Molecularly Selective Membranes. Nat. Mater. 2017, 16, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Hasan, M.M.; Field, R. Long-Term Stability of PEBAX-Zeolite MMMs Under Wet-CO₂ Conditions. Separ. Purif. Technol. 2024, 290, 120815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; Li, L.; Koros, W.J.; Veeramuthu, L.; Bobji, M.S. Molecular Modeling of Polymer–Zeolite Interfaces in Mixed Matrix Membranes for CO₂ Separation. Macromolecules 2025, 58, 1012–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Peng, H.; Gao, W.; Sun, Q.; Yan, X. Scale-Up and Manufacturing Techniques for Zeolite-Based MMMs: Toward Roll-to-Roll Production. Membranes 2023, 13, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Liu, R.; Xu, Z.; Xu, J.; Zhao, D. Interface-Free Core–Shell Zeolite–Polymer MMMs with Enhanced CO₂/CH₄ Selectivity. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 420, 131802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).