Submitted:

04 August 2025

Posted:

04 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

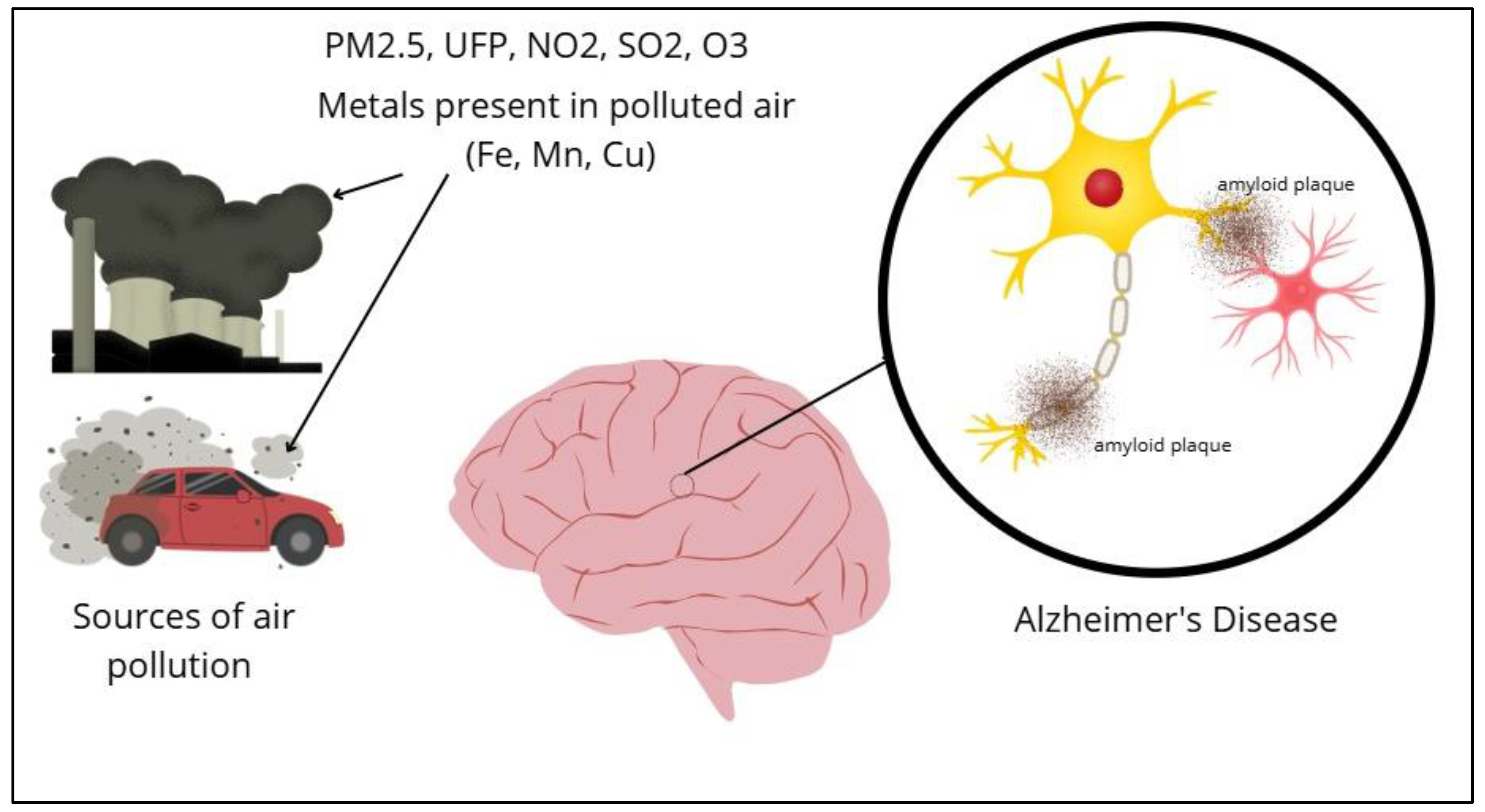

2. Air Pollution as an Environmental Risk Factor in AD

2.1. Sources of Air Pollution: Fine Particulate Matter, PM2.5 (≤2.5 µm) and PM10 (≤10 µm), Organic Compounds, Heavy Metals

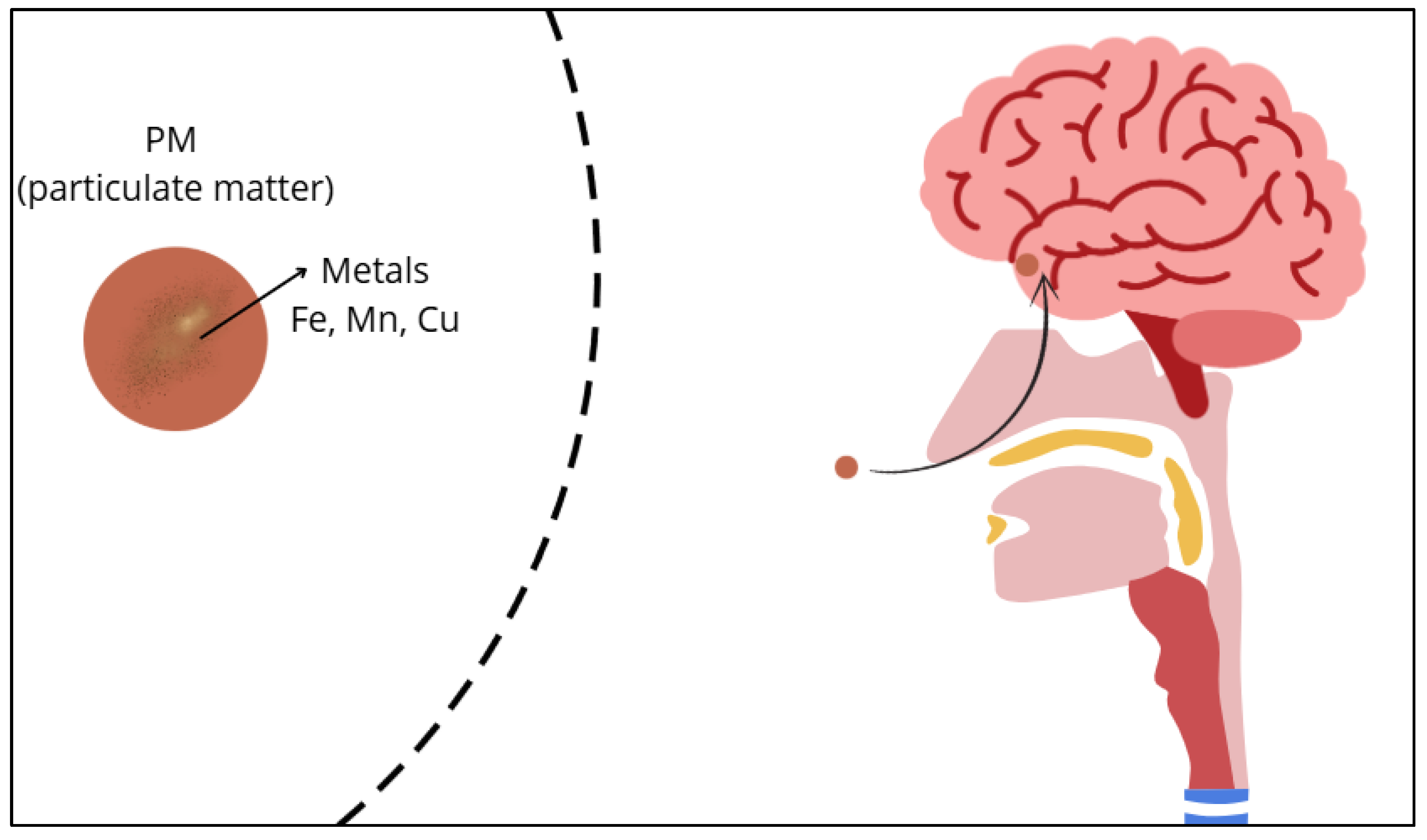

2.2. General Mechanisms by Which Air Pollution Impacts Neurological Health

3. Epidemiological Studies for Alzheimer´s Diseases (AD) and Alzheimer´s Diseases-Related Dementia (ADRD)

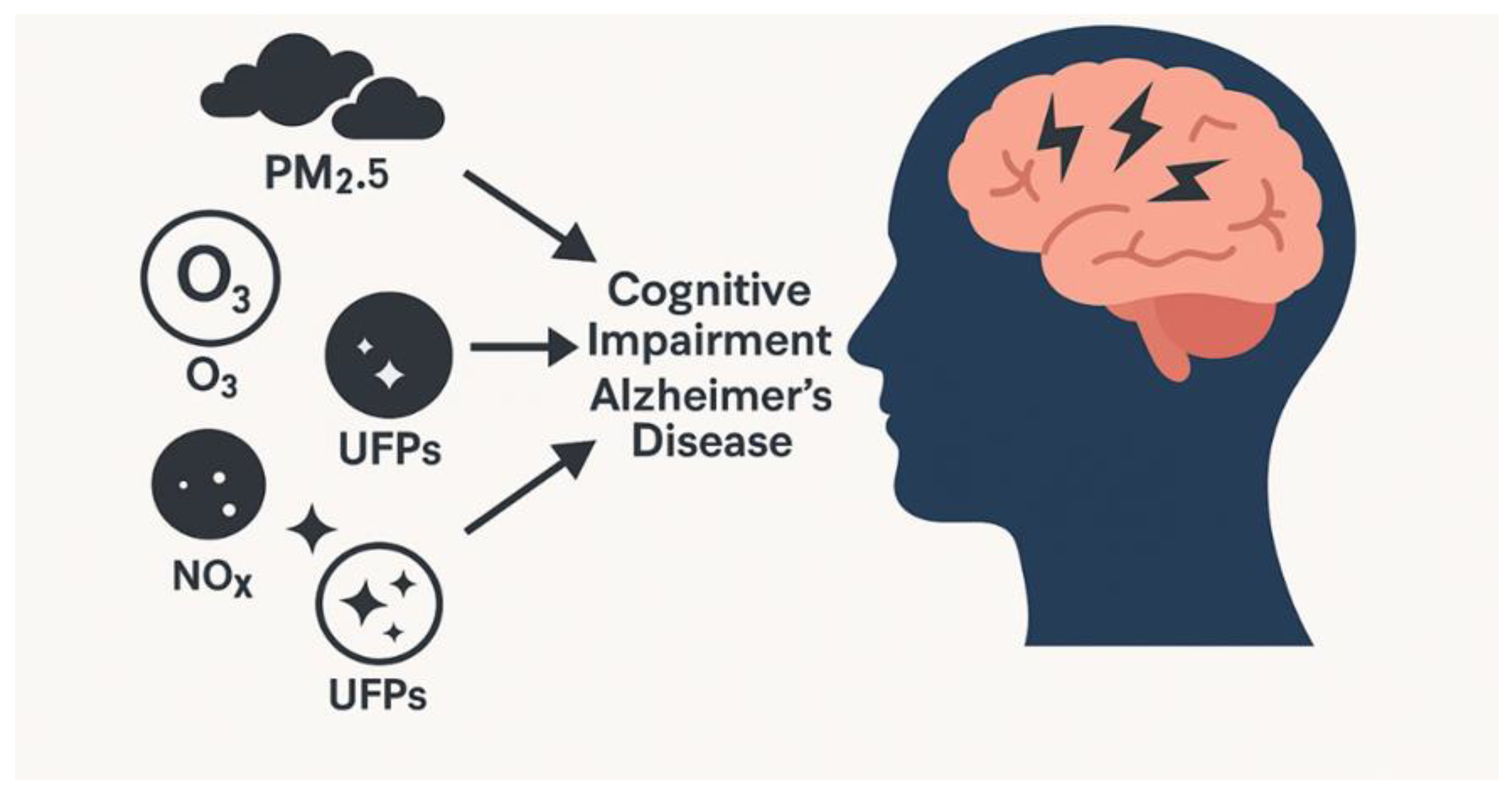

3.1. Epidemiological Studies That Link Exposure to Polluted Air with Cognitive Impairment and AD

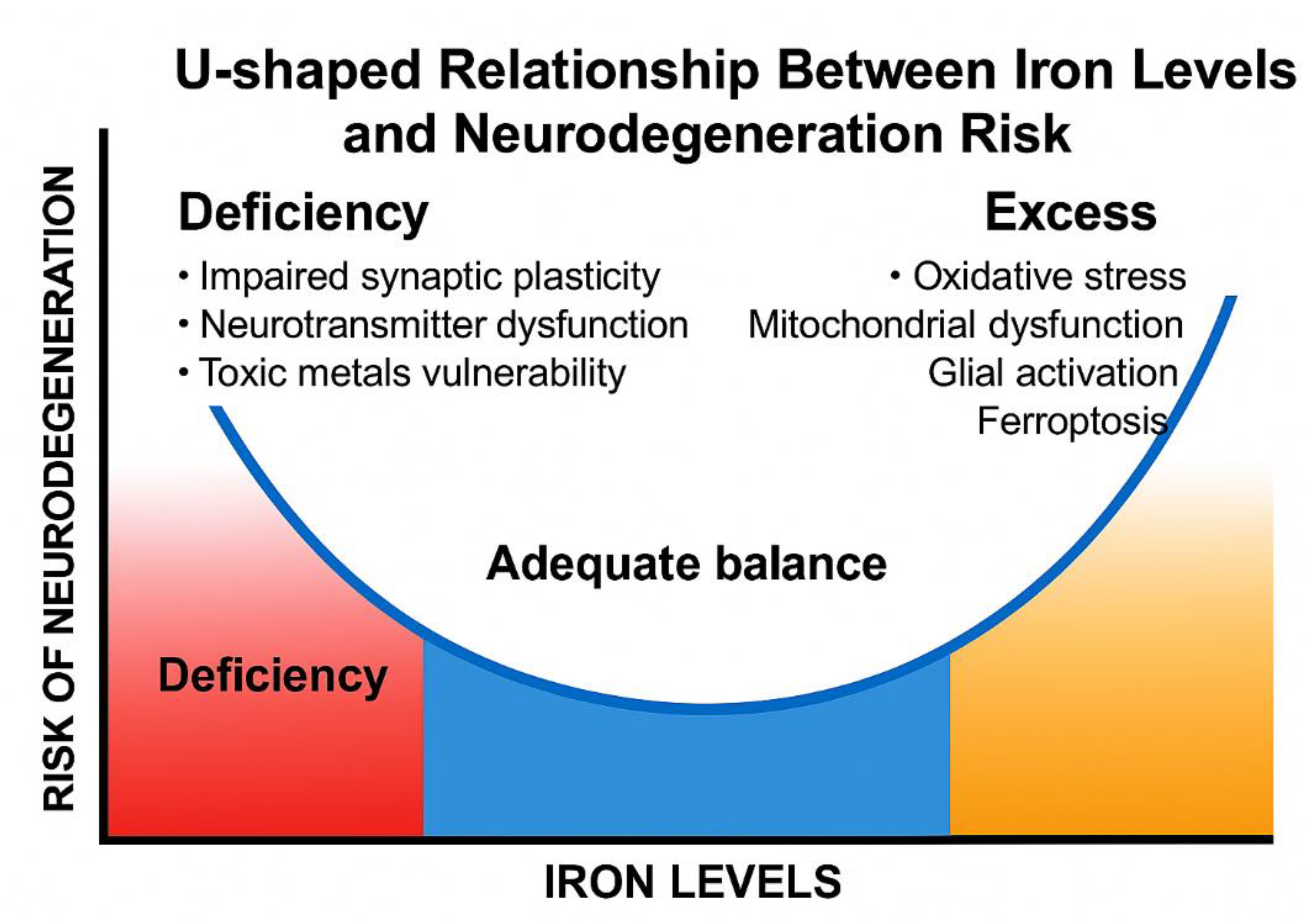

4. Metal Homeostasis in the Brain

4.1. Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Damage

4.2. Activated Microglia and Alzheimer Disease

Astrocytes

Microglia

Oligodendrocytes

Synapsis and AD

5. Public Health Implications

6. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Conclusions

Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, L.; Lin, Y.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, K.; Gong, H.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, B.; Zhang, X.; Sun, M. Microglia-derived extracellular vesicles mediate fine particulate matter-induced Alzheimer's disease-like behaviors through the mir-34a-5p/dusp10/p-p38 mapk pathway. J Hazard Mater 2025, 495, 138853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renesteen, E.; Boyajian, J.; Islam, P.; Kassab, A.; Abosalha, A.; Makhlouf, S.; Santos, M.; Chen, H.; Shum-Tim, C.; Prakash, S. Microbiome engineering for biotherapeutic in Alzheimer's disease through the gut-brain axis: potentials and limitations. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26, 5351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timalsina, D.; Abichandani, L.; Ambad, R. A review article on oxidative stress markers f2-isoprostanes and presenilin-1 in Alzheimer's disease. J Pharm Bioallied Sci 2025, 17(Suppl 1), S109–S112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marogianni, C.; Siokas, V.; Dardiotis, E. Recent Advances in the Detection and Management of Motor Dysfunction in Alzheimer's Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 36, 97–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blennow, K.; Hansson, O. . Blodtest – fönster till hjärnan vid Alzheimers sjukdom [blood biomarkers open a window to brain pathophysiology in Alzheimer's disease]. Lakartidningen 2024, 121, 23150. [Google Scholar]

- Ashton, N.J.; Benedet, A.L.; Molfetta, G.D.; Pola, I.; Anastasi, F.; Fernández-Lebrero, A.; Puig-Pijoan, A.; Keshavan, A.; Schott, J.; Tan, K.; et al. Biomarker discovery in Alzheimer's and neurodegenerative diseases using Nucleic Acid Linked Immuno-Sandwich Assay. Alzheimers Dement. 2025, 21, e14621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince, M.; Wimo, A.; Guerchet, M.; Ali, G.; Wu, Y.; Prina, M. World Alzheimer report 2015 - the global impact of dementia: an analysis of prevalence, incidence, cost and trends. London: Alzheimer's Disease International; 2015, 84. A: London.

- Manning, E.; Barnes, J.; Cash, D.; Bartlett, J.; Leung, K.; Ourselin, S.; Fox, N. Apoe ε4 is associated with disproportionate progressive hippocampal atrophy in ad. PLoS One 2014, 9, e97608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Zhou, W.; Chen, X.; Zhang, J. Sex differences in the association of APOE ε4 genotype with longitudinal hippocampal atrophy in cognitively normal older people. Eur J Neurol 2019, 26, 1362–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donkor, D.; Marfo, E.; Bockarie, A.; Tettevi, E.; Antwi, M.; Dogah, J.; Osei, G.; Simpong, D. Genetic and environmental risk factors for dementia in African adults: a systematic review. Alzheimers Dement 2025, 21, e70220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Essone, P.; Adegbite, B.; Mbadinga, M.; Mbouna, A.; Lotola-Mougeni, F.; Alabi, A.; Edoa, J.; Lell, B.; Alabi, A.; Adegnika, A.; et al. Creatine kinase-(mb) and hepcidin as candidate biomarkers for early diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis: a proof-of-concept study in Lambaréné, Gabon. Infection 2022, 50, 897–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mpaka-Mbatha, M.N.; Naidoo, P.; Islam, M.M.; Singh, R.; Mkhize-Kwitshana, Z.L. Anaemia and nutritional status during HIV and helminth coinfection among adults in South Africa. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milicic, A.; Wilson, S.; Javandel, S.; Allen, I.; Tsoy, E.; Ndhlovu, L.; Kibuuka, H.; Semwogerere, M.; Langat, R.; Daud, I.; et al. Plasma inflammatory biomarkers link to worse cognition among Africans with HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2025. [CrossRef]

- Obeagu, E.I. Iron homeostasis and health: understanding its role beyond blood health—a narrative review. Ann. Med. Surg. (Lond.) 2025, 87, 3362–3371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z.; Shen, Q.; Pang, Y.; Li, X.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X.; et al. The synthesized transporter K16APoE enabled the therapeutic HAYED peptide to cross the blood–brain barrier and remove excess iron and radicals in the brain, thus easing Alzheimer's disease. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2019, 9, 394–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milman, N. Dietary iron intakes in men in Europe are distinctly above the recommendations: a review of 39 national studies from 20 countries in the period 1995 - 2016. Gastroenterology Res 2020, 13, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turck, D.; Bohn, T.; Castenmiller, J.; de Henauw, S.; Hirsch-Ernst, K.I.; Knutsen, H.K.; et al. Scientific opinion on the tolerable upper intake level for iron. EFSA J. 2024, 22, e8819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habudele, Z.; Chen, G.; Qian, S.; Vaughn, M.; Zhang, J.; Lin, H. High dietary intake of iron might be harmful to atrial fibrillation and modified by genetic diversity: a prospective cohort study. Nutrients 2024, 16, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, G.; Lu, F.; Guo, Z.; Cai, S.; Huo, T. Excess iron intake induced liver injury: the role of gut-liver axis and therapeutic potential. Biomed Pharmacother 2023, 168, 115728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.; Feng, D.; Zhang, Y.; Zuo, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, L.; Hu, P. Effect and correlation of rosa roxburghii tratt juice fermented by lactobacillus paracasei sr10-1 on oxidative stress and gut microflora dysbiosis in streptozotocin (stz)-induced type 2 diabetes mellitus mice. Foods 2023, 12, 3233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapoor, B.; Biswas, P.; Gulati, M.; Rani, P.; Gupta, R. Gut microbiome and Alzheimer's disease: what we know and what remains to be explored. Ageing Res Rev 2024, 102, 102570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wingo, A.; Vattathil, S.; Liu, J.; Fan, W.; Cutler, D.; Levey, A.; Schneider, J.; Bennett, D.; Wingo, T. LDL cholesterol is associated with higher ad neuropathology burden independent of APOE. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2022, 93, 930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maret, W. The Metals in the Biological Periodic System of the Elements: Concepts and Conjectures. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyengar, V.; Pullakhandam, R.; Nair, K.M. Coordinate Expression and Localization of Iron and Zinc Transporters Explain Iron-Zinc Interactions during Uptake in Caco-2 Cells: Implications for Iron Uptake at the Enterocyte. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2012, 23, 1146–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kondaiah, P.; Yaduvanshi, P.S.; Sharp, P.A.; Pullakhandam, R. Iron and Zinc Homeostasis and Interactions: Does Enteric Zinc Excretion Cross-Talk with Intestinal Iron Absorption? Nutrients 2019, 11, 1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maares, M.; Einhorn, V.; Behrendt, J.; Marczynski, M.; Schüßler, C.; Lieleg, O.; Haase, H. Investigation of competitive binding of the essential trace elements zinc, iron, copper, and manganese by gastrointestinal mucins and the effect on their absorption in vitro. J Nutr Biochem 2025, 144, 109983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noordine, M.L.; Seyoum, Y.; Bruneau, A.; Baye, K.; Lefebvre, T.; Cherbuy, C.; Canonne-Hergaux, F.; Nicolas, G.; Humblot, C.; Thomas, M. The Microbiota and the Host Organism Switch between Cooperation and Competition Based on Dietary Iron Levels. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2361660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, P.W.; Giroux, A.; L’Abbé, M.R. Effect of zinc supplementation on copper status in adult man. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1984, 40, 743–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolff, N.A.; Garrick, M.D.; Zhao, L.; Garrick, L.M.; Ghio, A.J.; Thévenod, F. A Role for Divalent Metal Transporter (DMT1) in Mitochondrial Uptake of Iron and Manganese. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiles, L.I.; Ferrao, K.; Mehta, K.J. Role of Zinc in Health and Disease. Clin. Exp. Med. 2024, 24, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somsuan, K.; Phuapittayalert, L.; Srithongchai, Y.; Sonthi, P.; Supanpaiboon, W.; Hipkaeo, W.; Sakulsak, N. Increased DMT-1 Expression in Placentas of Women Living in High-Cd-Contaminated Areas of Thailand. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2019, 26, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, S.M.; Zhao, N. Expression of Manganese Transporters ZIP8, ZIP14, and ZnT10 in Brain Barrier Tissues. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Steimle, B.L.; Smith, F.M.; Kosman, D.J. The Solute Carriers ZIP8 and ZIP14 Regulate Manganese Accumulation in Brain Microvascular Endothelial Cells and Control Brain Manganese Levels. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 19197–19208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosman, D.J. A Holistic View of Mammalian (Vertebrate) Cellular Iron Uptake. Metallomics 2020, 12, 1323–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzocco, J.C.; Jagadapillai, R.; Gozal, E.; Kong, M.; Xu, Q.; Barnes, G.N.; Freedman, J.H. Disruption of essential metal homeostasis in the brain by cadmium and high-fat diet. Toxicol. Rep. 2020, 7, 1164–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baj, J.; Flieger, W.; Barbachowska, A.; Kowalska, B.; Flieger, M.; Forma, A.; Teresiński, G.; Portincasa, P.; Buszewicz, G.; Radzikowska-Büchner, E.; et al. Consequences of disturbing manganese homeostasis. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 14959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ścibior, A.; Llopis, J.; Dobrakowski, P.P.; Męcik-Kronenberg, T. CNS-Related Effects Caused by Vanadium at Realistic Exposure Levels in Humans: A Comprehensive Overview Supplemented with Selected Animal Studies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ścibior, A.; Llopis, J.; Dobrakowski, P.P.; Męcik-Kronenberg, T. Magnesium (Mg) and Neurodegeneration: A Comprehensive Overview of Studies on Mg Levels in Biological Specimens in Humans Affected Some Neurodegenerative Disorders with an Update on Therapy and Clinical Trials Supplemented with Selected Animal Studies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azman, K.; Ismail, C.; Shafin, N.; Zakaria, R. Alzheimer's disease and inflammation research: a systematic bibliometric review and network visualization of the published literature between 2000 and 2023. Recent Adv Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov.

- Park, H.; Armstrong, M.; Gorin, F.; Lein, P. Air pollution as an environmental risk factor for Alzheimer's disease and related dementias. Med Res Arch 2024, 12, 5825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maher, B. Airborne magnetite- and iron-rich pollution nanoparticles: potential neurotoxicants and environmental risk factors for neurodegenerative disease, including Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2019;71, 361-375. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, C.; Wu, D.; Yang, J.; Lu, X.; Chen, X.Y.; Ma, J.; Lin, C.; Lau, A.K.H.; Jin, Y.; Li, R.; et al. Ambient air pollution and Alzheimer's disease and other dementias: a global study between 1990 and 2019. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Bank. Urgent action needed in south Asia to curb deadly air pollution. 2022. (Accessed on July 21, 2025).

- IQAir. 2023 world air quality report. 2023. Available on: (Accessed on July 21, 2025).

- U.S. Environmental protection agency. Air Quality Trends. 2023. Available online: (Accessed on July 21, 2025).

- Mollalo, A.; Grekousis, G.; Florez, H.; Neelon, B.; Lenert, L.A.; Alekseyenko, A.V. Alzheimer's disease dementia prevalence in the United States: a county-level spatial machine learning analysis. Am. J. Alzheimers Dis. Other Demen. 2025, 40, 15333175251335570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baez, S.; Castro-Aldrete, L.; Britton, G.; Ibañez, A.; Santuccione-Chadha, A. Enhancing brain health in the global south through sex and gender lens. Nat Ment Health 2024, 2, 1308–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Sung, J.; Yim, S. Pm2.5-associated premature mortality attributable to hot-and-polluted episodes and the inequality between the global north and the global south. Geohealth 2025, 9, e2024GH001290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, J.; Hornburg, K.; Merrill, A.; Marvin, E.; Conrad, K.; Welle, K.; Gelein, R.; Chalupa, D.; Graham, U.; Oberdörster, G.; et al. Brain iron accumulation in neurodegenerative disorders: does air pollution play a role? part fibre toxicol. 2025, 22, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kagerer, S.; Vionnet, L.; van, B.J.; Meyer, R.; Gietl, A.; Pruessmann, K.; Hock, C.; Unschuld, P. Hippocampal iron patterns in aging and mild cognitive impairment. Front Aging Neurosci 2025, 17, 1598859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fano-Sizgorich, D.; Vásquez-Velásquez, C.; Ordoñez-Aquino, C.; Sánchez-Ccoyllo, O.; Tapia, V.; Gonzales, G.F. Iron trace elements concentration in PM10 and Alzheimer's disease in Lima, Peru: ecological study. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirozzi, M.A.; Canale, F.; Di Nardo, F.; Sharbafshaaer, M.; Passaniti, C.; Siciliano, M.; Cirillo, M.; Tessitore, A.; Tedeschi, G.; Esposito, F.; et al. Quantitative susceptibility mapping for investigating brain iron deposits in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: correlations with clinical phenotype and disease progression. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Frontotemporal Degener. 2025, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghaderi, S.; Mohammadi, S.; Ahmadzadeh, A.; Darmiani, K.; Arab, B.M.; Jashirenezhad, N.; Helfi, M.; Alibabaei, S.; Azadi, S.; Heidary, S.; et al. Thalamic magnetic susceptibility (χ) alterations in neurodegenerative diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis of quantitative susceptibility mapping studies. J Magn Reson Imaging 2025, 62, 271–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza Lima, R.; Fornaguera, J. Sex differences in 6-ohda lesioned rats in a preclinical model for parkinson's disease. Behav Brain Res 2025, 490, 115642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanff, A.; McCrum, C.; Rauschenberger, A.; Aguayo, G.; Pauly, C.; Jónsdóttir, S.; Tsurkalenko, O.; Zeegers, M.; Leist, A.; Krüger, R. Sex-specific progression of Parkinson's disease: a longitudinal mixed-models analysis. J Parkinsons Dis 1877718X251339201, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Abzhandadze, T.; Hoang, M.; Raaschou, P.; Norgren, J.; Mo, M.; Molnar, C.; Xu, H.; Kananen, L.; Åkerman, M.; Religa, D.; et al. Temporal trends in sex differences in dementia care- results from the Swedish registry for cognitive/dementia disorders, SveDem. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 18890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cervantes-Valencia, M.; Rojas-Lemus, M.; López-Valdez, N.; González-Villalva, A.; Fortoul, T. Genotoxic and cytotoxic effect of vanadium inhalation and oral administration of hintonia latiflora methanolic extract in mice. J Trace Elem Med Biol 2025, 89, 127677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Q.; Xie, J.; Zhang, L.; Zhen, Y.J.; Wang, Y.; Li, X. Traffic-related pm2.5 pollution in hong kong: component-specific and source-resolved health risks and cytotoxicity. Environ Pollut 2025, 380, 126525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Li, Z.; Wang, K.; Xie, C.; Zhu, J.; Wu, S. Association between ambient fine particulate matter constituents and mortality and morbidity of cardiovascular and respiratory diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ Pollut 2025, 379, 126476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Chai, G.; Song, X.; Hui, X.; Li, Z.; Feng, X.; Yang, K. Long-term exposure to particulate matter on cardiovascular and respiratory diseases in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Public Health 2023, 11, 1134341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Q.; Zou, S.; Hou, D.; An, Q.; Wang, P.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, R.; Huang, J.; Xue, J.; Gu, L. Characteristics and health risks of trace metals in pm2.5 before and during the heating period over three years in shijiazhuang, china. Toxics 2025, 13, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristaldi, A.; Fiore, M.; Oliveri Conti, G.; Pulvirenti, E.; Favara, C.; Grasso, A.; Copat, C.; Ferrante, M. Possible association between PM2.5 and neurodegenerative diseases: A systematic review. Environ. Res. 2022, 208, 112581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishihara, Y.; Tanaka, M.; Nezu, N.; Ishihara, N.; Oguro, A.; Vogel, C.F.A. Pathways to the Brain: Impact of Fine Particulate Matter Components on the Central Nervous System. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyakawa, T.; Ito, A.; Zhu, C.; Shimizu, A.; Matsumoto, E.; Kanaya, Y. Trace elements in PM2.5 aerosols in East Asian outflow in the spring of 2018: emission, transport, and source apportionment, Atmos. Chem. Phys.., 23, 14609–14626. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.Y.; Jeon, J.I.; Jung, J.Y.; Yoon, S.W.; Lee, C.M. PM2.5 and heavy metals in urban and agro-industrial areas: health risk assessment considerations. Asian J. Atmos. Environ. 2024, 18, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbazima, S.J.; Masekameni, M.D.; Nelson, G. Physicochemical Properties of Indoor and Outdoor Particulate Matter 2.5 in Selected Residential Areas near a Ferromanganese Smelter. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordoñez-Aquino, C.; Gonzales-, A.C.; Gonzales, G.F. Manganeso, otro contaminante en el aire que afecta el rendimiento escolar en el Perú. Rev Soc Peru Med Interna. 2023, 36, 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, M.; Ahmed, A.; Luo, W.; Bowman, A.; Tizabi, Y.; Aschner, M.; Ferrer, B. Combined manganese-iron exposure reduced oxidative stress is associated with the nrf2/nqo1 pathway in astrocytic c8-d1a cells. Biol Trace Elem Res 2025. [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Ji, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Li, S.; Qi, Y.; Wang, Y.; Cai, Y.; Lai, T.; Cui, L. Atmospheric Particulate Matter Impairs Cognition by Modulating Synaptic Function via the Nose-to-Brain Route. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 857, 159600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussalo, L.; Afonin, A.M.; Zavodna, T.; Krejcik, Z.; Honkova, K.; Fayad, C.; Shahbaz, M.A.; Kalapudas, J.; Penttilä, E.; Löppönen, H.; Koivisto, A.M.; Malm, T.; Topinka, J.; Jalava, P.; Lampinen, R.; Kanninen, K.M. Traffic-Related Ultrafine Particles Influence Gene Regulation in Olfactory Mucosa Cells Altering PI3K/AKT Signaling. Environ. Int. 2025, 199, 109484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godoy-Lugo, J.A.; Hicks, D.; Durra, S.; Massey, E.R.; Shkirkova, K.; Sauri, A.I.; Kerstiens, E.; Chen, S.; Zhao, L.; Sioutas, C.; Mack, W.J.; Finch, C.E.; Thorwald, M.A. Air Pollution Decreases Postsynaptic PSD-95 and NMDA Receptor Subunits in Synaptosomes from Mouse Cerebral Cortex. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 126845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godoy-Lugo, J.A.; Thorwald, M.A.; Cacciottolo, M.; D'Agostino, C.; Chakhoyan, A.; Sioutas, C.; Tanzi, R.E.; Rynearson, K.D.; Finch, C.E. Air pollution amyloidogenesis is attenuated by the gamma-secretase modulator GSM-15606. Alzheimers Dement. 2024, 20, 6107–6114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, Y.; Agarwal, P.; Vora, V.; Gosavi, S. Impact of air pollution on neurological and psychiatric health. Arch Med Res 2024, 55, 103063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lane, M.; Oyster, E.; Luo, Y.; Wang, H. The effects of air pollution on neurological diseases: a narrative review on causes and mechanisms. Toxics 2025, 13, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wang, J.; Jia, X.; Yang, Y.; Fang, Y.; Ying, X.; Li, H.; Zhang, M.; Wei, J.; Pan, Y. Microglial Polarization in Alzheimer's Disease: Mechanisms, Implications, and Therapeutic Opportunities. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2025, 104, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Sun, W.; Leng, L.; Yang, Y.; Gong, S.; Zou, Q.; Niu, H.; Wei, C. Ultrasound Stimulation Modulates Microglia M1/M2 Polarization and Affects Hippocampal Proteomic Changes in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer's Disease. Immun. Inflamm. Dis. 2024, 12, e70061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.P.; Wei, Y.S.; Hou, L.X.; Du, Y.X.; Yan, Q.Q.; Liu, L.L.; Zhao, Y.D.; Yan, R.Y.; Yu, C.; Zhong, Z.G.; Huang, J.L. Circular RNA APP Contributes to Alzheimer's Disease Pathogenesis by Modulating Microglial Polarization via miR-1906/CLIC1 Axis. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2025, 17, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Song, C.; Zhang, P.; Wang, J.; Huang, W.; Yu, T.; Wei, Z.; Wang, L.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, R.; Hou, L.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, H.; Wang, H. Microglial circDlg1 Modulates Neuroinflammation by Blocking PDE4B Ubiquitination-Dependent Degradation Associated with Alzheimer's Disease. Theranostics 2025, 15, 3401–3423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Liu, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Wu, L.; Chen, L.; Zhou, J.; Wang, F. METTL3/IGF2BP2/IκBα axis participates in neuroinflammation in Alzheimer's disease by regulating M1/M2 polarization of microglia. Neurochem. Int. 2025, 186, 105964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Liang, C.; Chen, X.; Cai, Y.; Cui, L. Interplay Between Microglia and Environmental Risk Factors in Alzheimer's Disease. Neural Regen. Res. 2024, 19, 1718–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Yang, L.; Jiang, W.; Zhang, X.; Yao, Z. Glycolytic Dysregulation in Alzheimer's Disease: Unveiling New Avenues for Understanding Pathogenesis and Improving Therapy. Neural Regen. Res. 2025, 20, 2264–2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalenik, S.; Zaczek, A.; Rodacka, A. Air pollution-induced neurotoxicity: the relationship between air pollution, epigenetic changes, and neurological disorders. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26, 3402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Shao, M.; Song, C.; Zhou, L.; Nie, W.; Yu, H.; Wang, S.; Liu, Y.; Yu, L. The Role of Epigenetic Mechanisms in the Development of PM2.5-Induced Cognitive Impairment. Toxics 2025, 13, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, A. Ambient air pollution and Alzheimer’s disease: the role of the composition of fine particles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2220028120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hullmann, M.; Albrecht, C.; van, B.D.; Gerlofs-Nijland, M.; Wahle, T.; Boots, A.; Krutmann, J.; Cassee, F.; Bayer, T.; Schins, R. Diesel engine exhaust accelerates plaque formation in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Part Fibre Toxicol 2017, 14, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, S.A.; Singhvi, A.; Patil, L.; Gohari, K.; Yitshak Sade, M.; Colicino, E.; Aldridge, M.D.; Baccarelli, A.A.; Kloog, I.; Schwartz, J.; et al. A Comprehensive Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis to Unravel the Noise-Dementia Nexus. Public Health Rev. 2025, 46, 1607355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Havyarimana, E.; Gong, X.; Jephcote, C.; Johnson, S.; Suri, S.; Xie, W.; Clark, C.; Hansell, A.L.; Cai, Y.S. Residential Exposure to Road and Railway Traffic Noise and Incidence of Dementia: The UK Biobank Cohort Study. Environ. Res. 2025, 279, 121787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, F.; Rashedi, V. Simultaneous exposure to noise and carbon monoxide increases the risk of Alzheimer's disease: a literature review. Med Gas Res 2020, 10, 85–90. [Google Scholar]

- Rentschler, K.; Kodavanti, U. Mechanistic insights regarding neuropsychiatric and neuropathologic impacts of air pollution. Crit Rev Toxicol 2024, 54, 953–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobolewski, M.; Conrad, K.; Marvin, E.; Eckard, M.; Goeke, C.; Merrill, A.; Welle, K.; Jackson, B.; Gelein, R.; Chalupa, D.; et al. . The potential involvement of inhaled iron (fe) in the neurotoxic effects of ultrafine particulate matter air pollution exposure on brain development in mice. Part Fibre Toxicol 2022, 19, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cory-Slechta, D.A.; Marvin, E.; Welle, K.; Goeke, C.; Chalupa, D.; Oberdörster, G.; Sobolewski, M. Male-Biased Vulnerability of Mouse Brain Tryptophan/Kynurenine and Glutamate Systems to Adolescent Exposures to Concentrated Ambient Ultrafine Particle Air Pollution. Neurotoxicology 2024, 104, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Liu, L.; Shu, Z.; Zhang, W.; Huang, C.; Zhu, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, W.; Li, G.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, Q.; Jiang, G. Magnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles: An Emerging Threat for the Environment and Human Health. J. Environ. Sci. (China) 2025, 152, 188–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trani, J.; Singh, R.; Walker, A.; Bekena, S.; Zhu, Y.; Williams, J.; Buckner, T.; Millsap, M.; Chen, C.; Taylor, K.; et al. . Structural and social determinants of dementia risk among adults racialized as black: results from a community-based system dynamics approach. Alzheimers Dement 2025, 21, e70494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadowska, A.; Grzesiak, M. Rola steroidów płciowych w chorobach neurodegeneracyjnych [the role of steroid hormones in the neurodegenerative diseases]. Postepy Biochem 2022, 68, 387–398. [Google Scholar]

- Nicoletti, A.; Baschi, R.; Cicero, C.E.; Iacono, S.; Re, V.L.; Luca, A.; Schirò, G.; Monastero, R.; Gender Neurology Study Group of the Italian Society of Neurology. Sex and gender differences in Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a narrative review. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2023, 212, 111821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Q.; Li, Q.; Guo, J. Causal relationship between sex hormones and risk of developing common neurodegenerative diseases: a mendelian randomization study. J Integr Neurosci 2024, 23, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, C.; Tang, Y. Association between levels of sex hormones and risk of multiple sclerosis: a mendelian randomization study. Acta Neurol Belg 2024, 124, 1913–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.; Li, Y.; Yang, L.; Luo, Y.; Yao, X. Bridging systemic metabolic dysfunction and Alzheimer's disease: the liver interface. Mol Neurodegener 2025, 20, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Nunez, J.; Toresco, D.; Wen, C.; Slotabec, L.; Wang, H.; Zhang, H.; Rouhi, N.; Adenawoola, M.; Li, J. Alterations in the inflammatory homeostasis of aging-related cardiac dysfunction and alzheimer's diseases. FASEB J 2025, 39, e70303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, J.D.; Flowers, C.H.; Skikne, B.S. The quantitative assessment of body iron. Blood 2003, 101, 3359–3364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.J.; Zeng, Q.G.; Zeng, H.X.; Meng, W.J.; Wu, Q.Z.; Lv, Y.; Dai, J.; Dong, G.H.; Zeng, X.W. Novel Perspective on Particulate Matter and Alzheimer's Disease: Insights from Adverse Outcome Pathway Framework. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 367, 125601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafin, P.; Zaremba, M.; Sulejczak, D.; Kleczkowska, P. Air pollution: a silent key driver of dementia. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzhrani, A.; Stockfelt, L.; Xu, Y.; Harari, F.; Gustafsson, S.; Engström, G.; Hansson, O.; Oudin, A. Long-term exposure to air pollution and validated cases of Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia in the Malmö diet and cancer cohort. J Alzheimers Dis 13872877251360225, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Wu, X.; Danesh, Y.M.; Braun, D.; Abu, A.Y.; Wei, Y.; Liu, P.; Di, Q.; Wang, Y.; Schwartz, J.; et al. . Long-term effects of pm2·5 on neurological disorders in the american medicare population: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Planet Health 2020, 4, e557–e565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, P.; Yung, K. Air pollution and alzheimer's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Alzheimers Dis. 2020, 77, 701–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, A.J.; Brauer, M.; Burnett, R.; Anderson, H.R.; Frostad, J.; Estep, K.; Balakrishnan, K.; Brunekreef, B.; Dandona, L.; Dandona, R.; et al. Estimates and 25-Year Trends of the Global Burden of Disease Attributable to Ambient Air Pollution: An Analysis of Data from the Global Burden of Diseases Study 2015. Lancet 2017, 389, 1907–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jutila, O.I.; Mullin, D.; Vieno, M.; Tomlinson, S.; Taylor, A.; Corley, J.; Deary, I.J.; Cox, S.R.; Baranyi, G.; Pearce, J.; et al. Life-course exposure to air pollution and the risk of dementia in the Lothian Birth Cohort 1936. Environ Epidemiol. 2024, 9, e355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, R.; Tong, X.; Shen, X.; Ran, J.; Sun, S.; Yao, X.I.; Shen, C. Longitudinal Associations between Air Pollution and Incident Dementia as Mediated by MRI-Measured Brain Volumes in the UK Biobank. Environ. Int. 2025, 195, 109219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón-Garcidueñas, L.; Cejudo-Ruiz, F.R.; Stommel, E.W.; González-Maciel, A.; Reynoso-Robles, R.; Silva-Pereyra, H.G.; Pérez-Guille, B.E.; Soriano-Rosales, R.E.; Torres-Jardón, R. Sleep and Arousal Hubs and Ferromagnetic Ultrafine Particulate Matter and Nanoparticle Motion Under Electromagnetic Fields: Neurodegeneration, Sleep Disorders, Orexinergic Neurons, and Air Pollution in Young Urbanites. Toxics 2025, 13, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón-Garcidueñas, L.; González-Maciel, A.; Reynoso-Robles, R.; Cejudo-Ruiz, F.R.; Silva-Pereyra, H.G.; Gorzalski, A.; Torres-Jardón, R. Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration, and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Start in Pediatric Ages: Ultrafine Particulate Matter and Industrial Nanoparticles Are Key in the Early-Onset Neurodegeneration: Time to Invest in Preventive Medicine. Toxics 2025, 13, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunawan, C.; Fleming, C.; Irga, P.J.; Wong, R.J.; Amal, R.; Torpy, F.R.; Golzan, M.; McGrath, K.C. Neurodegenerative effects of air pollutant particles: Biological mechanisms implicated for early-onset Alzheimer's disease. Environ. Int. 2024, 185, 108512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trentalange, A.; Badaloni, C.; Porta, D.; Michelozzi, P.; Renzi, M. Association between Air Quality and Neurodegenerative Diseases in River Sacco Valley: A Retrospective Cohort Study in Latium, Central Italy. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2025, 267, 114578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, H.C.; Shekha, T.A.M.; Annajigowda, H.H.; Charly, D.; Jessy, A.; Suresh, S.; Bhardwaj, S.; Anirudhan, A.; Mensegere, A.; Issac, T.G. Current Status of Research on the Modifiable Risk Factors of Dementia in India: A Scoping Review. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2025, 105, 104390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, D.; Paul, K.C.; O'Sharkey, K.; Paik, S.A.; Yu, Y.; Bronstein, J.M.; Ritz, B. Challenges in Studying Air Pollution to Neurodegenerative Diseases. Environ. Res. 2025, 278, 121597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Steinmetz, J.; Marsh, E.K.; Aravkin, A.Y.; Ashbaugh, C.; Murray, C.J.L.; Yang, F.; Ji, J.S.; Zheng, P.; Sorensen, R.J.D.; et al. A Systematic Review with a Burden of Proof Meta-Analysis of Health Effects of Long-Term Ambient Fine Particulate Matter (PM2.5) Exposure on Dementia. Nat. Aging 2025, 5, 897–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Liu, T. Greenness Modified the Association of PM2.5 and Ozone with Global Disease Burden of Alzheimer's Disease and Other Dementias. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 26823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, S.; Braun, D.; Wu, X.; Yitshak-Sade, M.; Blacker, D.; Kioumourtzoglou, M.A.; Schwartz, J.; Mork, D.; Dominici, F.; Zanobetti, A. The Impacts of Air Pollution on Mortality and Hospital Readmission among Medicare Beneficiaries with Alzheimer's Disease and Alzheimer's Disease-Related Dementias: A National Retrospective Cohort Study in the USA. Lancet Planet. Health 2025, 9, e114–e123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorthy, S.; Dazard, J.E.; Chen, Z.; Charak, R.; Palanivel, S.; Deo, S.; Al-Kindi, S.G.; Rajagopalan, S. Non-Traditional Socio-Environmental and Geospatial Determinants of Alzheimer's Disease-Related Dementia Mortality. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 984, 179745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dos Santos, N.; Yariwake, V.; Marques, K.; Veras, M.; Fajersztajn, L. Air pollution: a neglected risk factor for dementia in Latin America and the Caribbean. Front Neurol 2021, 12, 684524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Q.; Deng, Y.L.; Liu, Y.; Steenland, K. Associations between Ultrafine Particles and Incident Dementia in Older Adults. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 5443–5451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.; Ye, H.; Dong, Z.; Amujilite; Zhao, M.; Xu, Q.; Xu, J. The health and economic burden of ozone pollution on Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment in China. Environ Res 2024, 259, 119506. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, H.; Zhu, Q.; Ma, T.; Liu, Y.; Steenland, K. The Role of the Components of PM2.5 in the Incidence of Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders. Environ. Int. 2025, 200, 109539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, H.; Chen, G.; Wu, L.; Lou, H. Synergistic Impact of Air Pollution and Artificial Light at Night on Memory Disorders: A Nationwide Cohort Analysis. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaney, S.W.; Stegmuller, A.; Mork, D.; Mock, L.; Bell, M.L.; Gill, T.M.; Braun, D.; Zanobetti, A. Extreme Heat and Hospitalization among Older Persons with Alzheimer Disease and Related Dementias. JAMA Intern. Med. 2025, 185, 412–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, A.; Miller, E.C.; De Jager, P.L.; Avila-Rieger, J.; Arce Rentería, M.; Reed, A.; Hohman, T.J.; Jefferson, A.L.; Barnes, L.L.; Arvanitakis, Z.; et al. The Association Between Age of Menopause and Hysterectomy Status and Alzheimer's Disease Risk in a Cohort of Older White and Black Women. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluta, R. Gender-Dependent Modulation of Alzheimer's Disease by Brain Ischemia. Comment on Lohkamp et al. Sex-Specific Adaptations in Alzheimer's Disease and Ischemic Stroke: A Longitudinal Study in Male and Female APPswe/PS1dE9 Mice. Life (Basel). 2025, 15, 1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antwi, M.H.; Bockarie, A.; Osei, G.N.; Donkor, D.M.; Simpong, D.L. Cytokines and immune biomarkers in neurodegeneration and cognitive function: A systematic review among individuals of African ancestry. Alzheimers Dement. 2025, 21, e70514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Luca, A.; Luca, M.; Ferri, R.; Barbanti, M.; Malaguarnera, R.; Pecorino, B.; Scollo, P.; Serretti, A. Medical Comorbidities in Alzheimer's Disease: An Autopsy Confirmed Study with a Focus on Sex-Differences? Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2025, 22, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Carney, B.N.; Illiano, P.; Pohl, T.M.; Desu, H.L.; Mini, A.; Mudalegundi, S.; Asencor, A.I.; Jwala, S.; Ascona, M.C.; Singh, P.K; et al. Astroglial TNFR2 signaling regulates hippocampal synaptic function and plasticity in a sex dependent manner. Brain Behav Immun. 2025, 129, 757–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez, M.C.; Freeborn, D.L.; Vulimiri, P.; Valdez, J.M.; Kodavanti, U.P.; Kodavanti, P.R.S. Acute Ozone-Induced Transcriptional Changes in Markers of Oxidative Stress and Glucocorticoid Signaling in the Rat Hippocampus and Hypothalamus Are Sex-Specific. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, A. The metallobiology of Alzheimer's disease. Trends Neurosci 2003, 26, 207–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, P.; Pinto, E.; Santos, A.; Almeida, A. Reference values for trace element levels in the human brain: a systematic review of the literature. J Trace Elem Med Biol 2021, 66, 126745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbo, D.; Gasparotti, R.; Renzetti, S. Exploring the Neural Correlates of Metal Exposure in Motor Areas. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, C.; Qin, L.; Liao, X.; Zhao, L. The Close Relationship between Trace Elements (Cu, Fe, Zn, Se, Rb, Si, Cr, and V) and Alzheimer's Disease: Research Progress and Insights. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 90, 127692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jomova, K.; Alomar, S.; Nepovimova, E.; Kuca, K.; Valko, M. Heavy metals: toxicity and human health effects. Arch Toxicol 2025, 99, 153–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhapola, R.; Sharma, P.; Kumari, S.; Bhatti, J.S.; HariKrishnaReddy, D. Environmental toxins and Alzheimer’s disease: a comprehensive analysis of pathogenic mechanisms and therapeutic modulation. Mol. Neurobiol. 2024, 61, 3657–3677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, C.; Li, D.; Zhang, J.; Yin, Z.; Li, F. Scorpion venom heat-resistant synthetic peptide alleviates neuronal necroptosis in Alzheimer's disease model by regulating Lnc Gm6410 under PM2.5 exposure. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Balendra, V.; Obaid, A.A.; Esposto, J.; Tikhonova, M.A.; Gautam, N.K.; Poeggeler, B. Copper-mediated β-amyloid toxicity and its chelation therapy in Alzheimer's disease. Metallomics 2022, 14, mfac018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.R.; Rauf, A.; Akter, S.; Akter, H.; Al-Imran, M.I.K.; Fakir, M.N.H.; Thufa, G.K.; Islam, M.T.; Hemeg, H.A.; Abdulmonem, W.A.; et al. Neuroprotective Potential of Curcumin in Neurodegenerative Diseases: Clinical Insights into Cellular and Molecular Signaling Pathways . J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2025, 39, e70369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schipper, D.A.; Schipper, H.M. Neurodegeneration with Brain Iron Accumulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 1480, 291–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wydrych, A.; Pakuła, B.; Jakubek-Olszewska, P.; Janikiewicz, J.; Dobosz, A.M.; Cudna, A.; Rydzewski, M.; Pierzynowska, K.; Gaffke, L.; Cyske, Z.; et al. Metabolic Alterations in Fibroblasts of Patients Presenting with the MPAN Subtype of Neurodegeneration with Brain Iron Accumulation (NBIA). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 1871, 167541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wydrych, A.; Pakuła, B.; Janikiewicz, J.; Dobosz, A.M.; Jakubek-Olszewska, P.; Skowrońska, M.; Kurkowska-Jastrzębska, I.; Cwyl, M.; Popielarz, M.; Pinton, P.; et al. Metabolic Impairments in Neurodegeneration with Brain Iron Accumulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 1866, 149517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, G.; Rahaman, M.; Perez, E.; Khan, K. Associations of environmental exposure to arsenic, manganese, lead, and cadmium with alzheimer's disease: a review of recent evidence from mechanistic studies. J Xenobiot 2025, 15, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, R.; Zucca, F.; Duyn, J.; Crichton, R.; Zecca, L. The role of iron in brain ageing and neurodegenerative disorders. Lancet Neurol 2014, 13, 1045–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colvin, R.A.; Jin, Q.; Lai, B.; Kiedrowski, L. Visualizing metal content and intracellular distribution in primary hippocampal neurons with synchrotron X-ray fluorescence. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0159582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, Y.; Zhong, J.; Teng, M.; Peng, J.; Huang, H.; Aschner, M.; Jiang, Y. Advances in research on neurotoxicity and mechanisms of manganese, iron, and copper exposure, alone or in combination. J Appl Toxicol 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.; Zhu, W.; Wei, L.; Zhao, J. Iron homeostasis imbalance and ferroptosis in brain diseases. MedComm 2023, 4, e298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kittilukkana, A.; Carmona, A.; Normand, L.; Gibout, C.; Somogyi, A.; Pilapong, C.; Ortega, R. Storage and transport of labile iron is mediated by lysosomes in axons and dendrites of hippocampal neurons. Metallomics 2025, 17, mfaf021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Z.; Yang, L.; Li, M.; Zhang, Q.; Li, J.; Zhang, N.; Che, Y.; Chen, Y.; Liang, P.; Wang, Y.; et al. The Role of Iron Homeostasis Imbalance in T2DM-Associated Cognitive Dysfunction: A Prospective Cohort Study Utilizing Quantitative Susceptibility Mapping. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2025, 46, e70263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yang, Y.; Wu, J.; Wang, L.; Ji, G.; Dang, Y. Copper homeostasis and cuproptosis in health and disease. MedComm (2020). 2024, 5, e724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Alghadir, A.; Gabr, S.; Al-Eisa, E. . Assessment of the effects of glutamic acid decarboxylase antibodies and trace elements on cognitive performance in older adults. Clin Interv Aging 2015, 10, 1901–7. [Google Scholar]

- Rozumna, N.; Hanzha, V.; Shkryl, V.; Lukyanetz, E. Dantrolene protects hippocampal neurons against amyloid-β₁₋₄₂-induced calcium dysregulation and cell death. Neurochem Res 2025, 50, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Shen, R.; Qian, M.; Zhou, Z.; Xie, B.; Jiang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Dong, W. Ferroptosis in Alzheimer's disease: the regulatory role of glial cells. J. Integr. Neurosci. 2025, 24, 25845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, S.M.; Zhao, N. ZIP14 deletion disrupts divalent metal homeostasis in mouse cerebrospinal fluid. Cell Biochem. Funct. 2025, 43, e70086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Chen, M.; Duan, J.; Lu, R.; Li, L. ZnTs: Key Regulators of Zn²⁺ Homeostasis in Diseases. Cell Biol. Int. 2025, 49, e70056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samokhina, E.; Mangat, A.; Malladi, C.; Gyengesi, E.; Morley, J.; Buskila, Y. Potassium homeostasis during disease progression of alzheimer's disease. J Physiol 2025, 603, 3405–3424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Gao, L.; Yang, Y.; Shi, D.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, X.; Huang, Y.; Wu, J.; Meng, J.; Li, H.; et al. Protective role of mitophagy on microglia-mediated neuroinflammatory injury through mtDNA-sting signaling in manganese-induced parkinsonism. J Neuroinflammation 2025, 22, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obeng, S.; Kulhánek, M.; Balík, J.; Černý, J.; Sedlář, O. Manganese: from soil to human health-a comprehensive overview of its biological and environmental significance. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Chakraborty, S.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Lee, E.; Paoliello, M.; Bowman, A.; Aschner, M. Manganese homeostasis in the nervous system. J Neurochem 2015, 134, 601–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, A.; Oliveira-Paula, G.; Tinkov, A.; Skalny, A.; Tizabi, Y.; Bowman, A.; Aschner, M. Role of manganese in brain health and disease: focus on oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med 2025, 232, 306–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wang, X.; Xia, J.; Jia, J.; Zhang, S.; Wang, W.; He, W.; Song, X.; Chen, L.; Niu, P.; et al. Small extracellular vesicles-derived from 3d cultured human nasal mucosal mesenchymal stem cells during differentiation to dopaminergic progenitors promote neural damage repair via mir-494-3p after manganese exposed mice. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2024, 280, 116569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Lv, S.; Zhao, H.; He, G.; Liang, H.; Chen, K.; Qu, M.; He, Y.; Ou, C. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 as targets for neuroprotection : from ferroptosis to Parkinson's disease. Neurol Sci 2025, 46, 1111–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Tao, Z.; Zhang, X.; Hu, J.; Wang, S.; Xing, G.; Ngeng, N.A.; Malik, A.; Appiah-Kubi, K.; Farina, M.; et al. Manganese overexposure results in ferroptosis through the HIF-1α/p53/SLC7A11 pathway in ICR mouse brain and PC12 cells. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 279, 116481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Villahoz, B.; Ponzio, R.; Aschner, M.; Chen, P. Signaling pathways involved in manganese-induced neurotoxicity. Cells 2023, 12, 2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, K.; Oaks, B. U-shaped curve for risk associated with maternal hemoglobin, iron status, or iron supplementation. Am J Clin Nutr 2017, 106(Suppl 6), 1694S–1702S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzales, G.F.; Valverde-Aparicio, V.M. Impacto de la nueva definición de anemia por parte de la Organización Mundial de la Salud: el rol en investigación de la Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia. Acta Herediana 2024, 67, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbano, T.; Michalke, B.; Chiari, A.; Malagoli, C.; Bedin, R.; Tondelli, M.; Vinceti, M.; Filippini, T. Iron species in cerebrospinal fluid and dementia risk in subjects with mild cognitive impairment: a cohort study. Neurotoxicology 2025, 110, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monzel, A.S.; Enríquez, J.A.; Picard, M. Multifaceted Mitochondria: Moving Mitochondrial Science Beyond Function and Dysfunction. Nat. Metab. 2023, 5, 546–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokota, M. Analysis of Dopaminergic Neuron-Specific Mitochondrial Morphology and Function Using Tyrosine Hydroxylase Reporter iPSC Lines. Anat. Sci. Int. 2025, 100, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neikirk, K.; Harris, C.; Le, H.; Oliver, A.; Shao, B.; Liu, K.; Beasley, H.K.; Jamison, S.; Ishimwe, J.A.; Kirabo, A.; et al. Air Pollutants as Modulators of Mitochondrial Quality Control in Cardiovascular Disease. Physiol. Rep. 2024, 12, e70118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mussalo, L.; Lampinen, R.; Avesani, S.; Závodná, T.; Krejčík, Z.; Kalapudas, J.; Penttilä, E.; Löppönen, H.; Koivisto, A.M.; Malm, T.; et al. Traffic-Related Ultrafine Particles Impair Mitochondrial Functions in Human Olfactory Mucosa Cells—Implications for Alzheimer's Disease. Redox Biol. 2024, 75, 103272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grujicic, J.; Allen, A.R. MnSOD mimetics in therapy: exploring their role in combating oxidative stress-related diseases. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Sun, X.; Chen, B.; Dai, R.; Xi, Z.; Xu, H. Insights into manganese superoxide dismutase and human diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 15893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschner, M.; Skalny, A.; Rongzhu, L.; Santamaria, A.; Lee, E.; Bowman, A.; Tizabi, Y.; Zhou, J.; Tinkov, A. The role of epigenetics in manganese neurotoxicity: an update with a focus on non-coding RNAs and histone modifications. Neurochem Res 2025, 50, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calderón-Garcidueñas, L.; Stommel, E.W.; Torres-Jardón, R.; Hernández-Luna, J.; Aiello-Mora, M.; González-Maciel, A.; Reynoso-Robles, R.; Pérez-Guillé, B.; Silva-Pereyra, H.G.; Tehuacanero-Cuapa, S.; et al. Alzheimer and Parkinson Diseases, Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Overlapping Neuropathology Start in the First Two Decades of Life in Pollution Exposed Urbanites and Brain Ultrafine Particulate Matter and Industrial Nanoparticles, Including Fe, Ti, Al, V, Ni, Hg, Co, Cu, Zn, Ag, Pt, Ce, La, Pr and W Are Key Players. Metropolitan Mexico City Health Crisis Is in Progress. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2024, 17, 1297467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iban-Arias, R.; Portela, A.S.D.; Masieri, S.; Radu, A.; Yang, E.J.; Chen, L.C.; Gordon, T.; Pasinetti, G.M. Role of Acute Exposure to Environmental Stressors in the Gut-Brain-Periphery Axis in the Presence of Cognitive Resilience. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2025, 1871, 167760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucini, C.; Gatta, C. Glial diversity and evolution: insights from teleost fish. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz de León-López, C.A.; Navarro-Lobato, I.; Khan, Z.U. The role of astrocytes in synaptic dysfunction and memory deficits in Alzheimer’s disease. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, P.R.; Ay, M.; Langley, M.; Plunk, E.; Strazdins, R.; Abu-Salah, A.; Anchan, A.; Shah, A.; Sarkar, S. Neurotoxicants Driving Glial Aging: Role of Astrocytic Aging in Non-Cell Autonomous Neurodegeneration. Toxicol. Sci. 2025, kfaf088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favetta, G.; Bubacco, L. Beyond Neurons: How Does Dopamine Signaling Impact Astrocytic Functions and Pathophysiology? Prog. Neurobiol. 2025, 251, 102798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duhaini, M.; Shamroukh, H.S.; Zhang, Z.; Kondapalli, K.C. Astrocyte Secretome Remodeling under Iron Deficiency: Potential Implications for Brain Iron Homeostasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 14, bio062057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moro, A.S.; Balestrucci, C.; Cozzi, A.; Santambrogio, P.; Levi, S. Neuroferritinopathy Human-Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Astrocytes Reveal an Active Role of Free Intracellular Iron in Astrocyte Reactivity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 6197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, A.; Prasad, R. Recent discoveries on the functions of astrocytes in the copper homeostasis of the brain: a brief update. Neurotox. Res. 2014, 26, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Su, X.; Wang, Y.; Liang, W.; Wang, D.; Huo, D.; Wang, H.; Qi, Y.; Zhang, W.; Han, L.; et al. Comm domain containing 4 inhibits hephaestin and ferroportin to enhance neuronal ferroptosis by disturbing the cu-fe balance in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain Res 2025, 1861, 149707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Squitti, R.; Ventriglia, M.; Simonelli, I.; Bonvicini, C.; Costa, A.; Perini, G.; Binetti, G.; Benussi, L.; Ghidoni, R.; Koch, G.; et al. Copper imbalance in Alzheimer's disease: meta-analysis of serum, plasma, and brain specimens, and replication study evaluating atp7b gene variants. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, C.; Chen, B.; Yang, H.; Zhou, X. The Dual Role of Microglia in Alzheimer’s Disease: From Immune Regulation to Pathological Progression. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2025, 17, 1554398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Kou, Y.; Ni, Y.; Yang, H.; Xu, C.; Fan, H.; Liu, H. Microglia efferocytosis: an emerging mechanism for the resolution of neuroinflammation in Alzheimer's disease. J. Neuroinflammation 2025, 22, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valiukas, Z.; Tangalakis, K.; Apostolopoulos, V.; Feehan, J. Microglial activation states and their implications for Alzheimer's disease. J. Prev. Alzheimers Dis. 2025, 12, 100013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, V.; Kumari, S.; Dhapola, R.; Sharma, P.; Beura, S.K.; Singh, S.K.; Vellingiri, B.; HariKrishnaReddy, D. Shedding Light on Microglial Dysregulation in Alzheimer’s Disease: Exploring Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Avenues. Inflammopharmacology 2025, 33, 679–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebrahimi, R.; Shahrokhi, N.S.; Falah, T.M.; Karimi, Z.; Sadr, S.; Ramadhan, H.D.; Talebian, N.; Esmaeilpour, K. Microglial activation as a hallmark of neuroinflammation in Alzheimer's disease. Metab Brain Dis 2025, 40, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, R.; Choudhary, H.H.; Zhang, F.; Mehta, H.; Yoshida, J.; Thomas, A.J.; Hanafy, K. Microglial TLR4-Lyn kinase is a critical regulator of neuroinflammation, Aβ phagocytosis, neuronal damage, and cell survival in Alzheimer's disease. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 11368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, C.; Ealy, A.; Gregory, A.; Janarthanam, C.; Albers, W.; Richardson, G.; Jin, H.; Zenitsky, G.; Anantharam, V.; Kanthasamy, A.; et al. Pathological α-synuclein dysregulates epitranscriptomic writer mettl3 to drive neuroinflammation in microglia. Cell Rep 2025, 44, 115618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyarko-Danquah, I.; Pajarillo, E.; Kim, S.; Digman, A.; Multani, H.; Ajayi, I.; Son, D.; Aschner, M.; Lee, E. Microglial sp1 induced lrrk2 upregulation in response to manganese exposure, and 17β-estradiol afforded protection against this manganese toxicity. Neurotoxicology 2024, 103, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sil, M.; Mukherjee, N.; Chatterjee, I.; Ghosh, A.; Goswami, A. Glial cells in Alzheimer's disease: pathogenic mechanisms and therapeutic frontiers. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2025, 75, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szwed, M.; de Jesus, A.V.; Kossowski, B.; Ahmadi, H.; Rutkowska, E.; Mysak, Y.; Baumbach, C.; Kaczmarek-Majer, K.; Degórska, A.; Skotak, K.; et al. Air pollution and cortical myelin T1w/T2w ratio estimates in school-age children from the ABCD and NeuroSmog studies. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 2025, 73, 101538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herting, M.M.; Burnor, E.; Ahmadi, H.; Eckel, S.P.; Gauderman, W.; Schwartz, J.; Berhane, K.; McConnell, R.; Chen, J.C. Air pollution exposure, prefrontal connectivity, and emotional behavior in early adolescence. Res. Rep. Health Eff. Inst. 2025, 2025, 1–56. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lamorie-Foote, K.; Liu, Q.; Shkirkova, K.; Ge, B.; He, S.; Morgan, T.E.; Mack, W.J.; Sioutas, C.; Finch, C.E.; Mack, W.J. Particulate matter exposure and chronic cerebral hypoperfusion promote oxidative stress and induce neuronal and oligodendrocyte apoptosis in male mice. J. Neurosci. Res. 2023, 101, 384–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakhoyan, A.; Shkrkova, K.; Sizdahkhani, S.; Huuskonen, M.T.; Lamorie-Foote, K.; Diaz, A.; Chen, S.; Liu, Q.; D'Agostino, C.; Zhang, H.; et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of white matter response to diesel exhaust particles. Res. Sq. Preprint, rs.3.rs-3087503. 3087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Yin, Y.; Xia, X.; Que, X.; Liu, X.; Zhao, G.; Chen, J.; Chen, Q.; Xu, Z.; Tang, Y.; Qin, Q. Regulation of synaptic function and lipid metabolism. Neural Regen. Res. 2026, 21, 1037–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Qin, C. Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis: standing at the crossroad of lipid metabolism and immune response. Mol Neurodegener 2025, 20, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badia-Soteras, A.; Mak, A.; Blok, T.M.; Boers-Escuder, C.; van den Oever, M.C.; Min, R.; Smit, A.B.; Verheijen, M.H.G. Astrocyte-Synapse Structural Plasticity in Neurodegenerative and Neuropsychiatric Diseases. , Biol. Psychiatry 2025, S0006-3223(25)01125-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salardini, E.; O'Dell, R.S.; Tchorz, E.; Nabulsi, N.B.; Huang, Y.; Carson, R.E.; van Dyck, C.H.; Mecca, A.P. Assessment of the Relationship between Synaptic Density and Metabotropic Glutamate Receptors in Early Alzheimer’s Disease: A Multi-Tracer PET Study. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2025, 17, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin Flores, N.; Podpolny, M.; McLeod, F.; Workman, I.; Crawford, K.; Ivanov, D.; Leonenko, G.; Escott-Price, V.; Salinas, P.C. Downregulation of Dickkopf-3, a Wnt Antagonist Elevated in Alzheimer's Disease, Restores Synapse Integrity and Memory in a Disease Mouse Model. eLife 2024, 12, RP89453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, R. Biomarkers for Synaptic Dysfunction in Alzheimer’s Disease. Neural Regen. Res. 2026, 21, 683–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanaki Bavarsad, M.; Spina, S.; Oehler, A.; Allen, I.E.; Suemoto, C.K.; Leite, R.E.P.; Seeley, W.S.; Green, A.; Jagust, W.; Rabinovici, G.D.; Grinberg, L.T. Comprehensive Mapping of Synaptic Vesicle Protein 2A (SV2A) in Health and Neurodegenerative Diseases: A Comparative Analysis with Synaptophysin and Ground Truth for PET-Imaging Interpretation. Acta Neuropathol. 2024, 148, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzioras, M.; McGeachan, R.I.; Durrant, C.S.; Spires-Jones, T.L. Synaptic Degeneration in Alzheimer Disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2023, 19, 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mecca, A.P.; Ashton, N.J.; Chen, M.K.; O'Dell, R.S.; Toyonaga, T.; Zhao, W.; Young, J.J.; Salardini, E.; Bates, K.A.; Ra, J.; et al. Cerebrospinal Fluid and Brain Positron Emission Tomography Measures of Synaptic Vesicle Glycoprotein 2A: Biomarkers of Synaptic Density in Alzheimer's Disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2025, 21, e70344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiankhaw, K.; Chattipakorn, N.; Chattipakorn, S. . Pm2.5 exposure in association with ad-related neuropathology and cognitive outcomes. Environ Pollut 2022, 292(Pt A), 118320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, A.; Ali, M.U.; Mayhew, A.; Aryal, K.; Correia, R.H.; Dash, D.; Manis, D.R.; Rehman, A.; O'Connell, M.E.; Taler, V.; et al. Environmental risk factors for all-cause dementia, Alzheimer's disease dementia, vascular dementia, and mild cognitive impairment: An umbrella review and meta-analysis. Environ. Res. 2025, 270, 121007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| MATRIX | METALS FOUND / RESULTS | AGE | LOCATION | METHOD | REFERENCE |

| PM2.5 (EXPERIMENTAL EXPOSURE) | Fe, Mn | Mice (juvenile and adult) | Controlled experimental settings | Experimental | [68] |

| AIRBORNE PM10 | Fe, Cu, Mn, Zn, SO2 | ≥ 60 years | Lima, Peru | Ecology | [51] |

| AIRBORNE ULTRAFINE PM | Fe, Ti, Hg, Ni, Co, Cu, Zn, Cd, Al, Mg, Ag, Ce, La, Pr, W, Ca, Cl, K, Si, S, Na y C | Pediatric to older adults | Mexico City | Pathology, Imaging | [109] |

| UFPS | Adolescent mice | Laboratory setting | Experimental Animal Study | [91] | |

| PM2.5 | SO42- , OC, Cu | ≥ 60 years | USA | Cohort study, modeling | [122] |

| PM10 | Fe, Mn | All ages | La Oroya, Cerro de Pasco, Callao, Junín, Lima (Peru) | Narrative synthesis | [67] |

| FE EXPOSURE | Magnetite (Fe₃O₄) | Mice: juvenile | University of Rochester Medical Center, USA | Pathology & Imaging | [49] |

| DIESEL EXHAUST PARTICLES | altered myelin composition in multiple regions | Mice: adult | Zilkha Neurogenetic Institute, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, USA | Pathology & Imaging | [198] |

| IN BLOOD (FER-1 , MNCL2 , FER-1 + MNCL2 ) | Mn-exposed mice exhibited movement impairment and encephalic pathological changes, with decreased HIF-1α, SLC7A11, and GPX4 proteins and increased p53 protein levels. Fer-1 exhibited protective effects against Mn-induced both behavioral and biochemical changes | Mice: juvenile | Department of Preventive Medicine and Public Health Laboratory Sciences, School of Medicine, Jiangsu University, Zhenjiang, Jiangsu 212013, China | Experimental Animal Study | [163] |

| POLLUTANT IRON-BASED PARTICLE, HYDROCARBON-BASED DIESEL COMBUSTION PARTICLE AND MAGNETITE PARTICLES | Neuronal cell loss was shown in the hippocampal and somatosensory cortex, with increased detection of Aβ plaque, | Mice: juvenile | Australian Institute for Microbiology and Infection, University of Technology Sydney, Sydney, Australia | Experimental Animal Study | [111] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).