Submitted:

06 May 2025

Posted:

06 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

Data Collection and Selection

Statistical Analyses

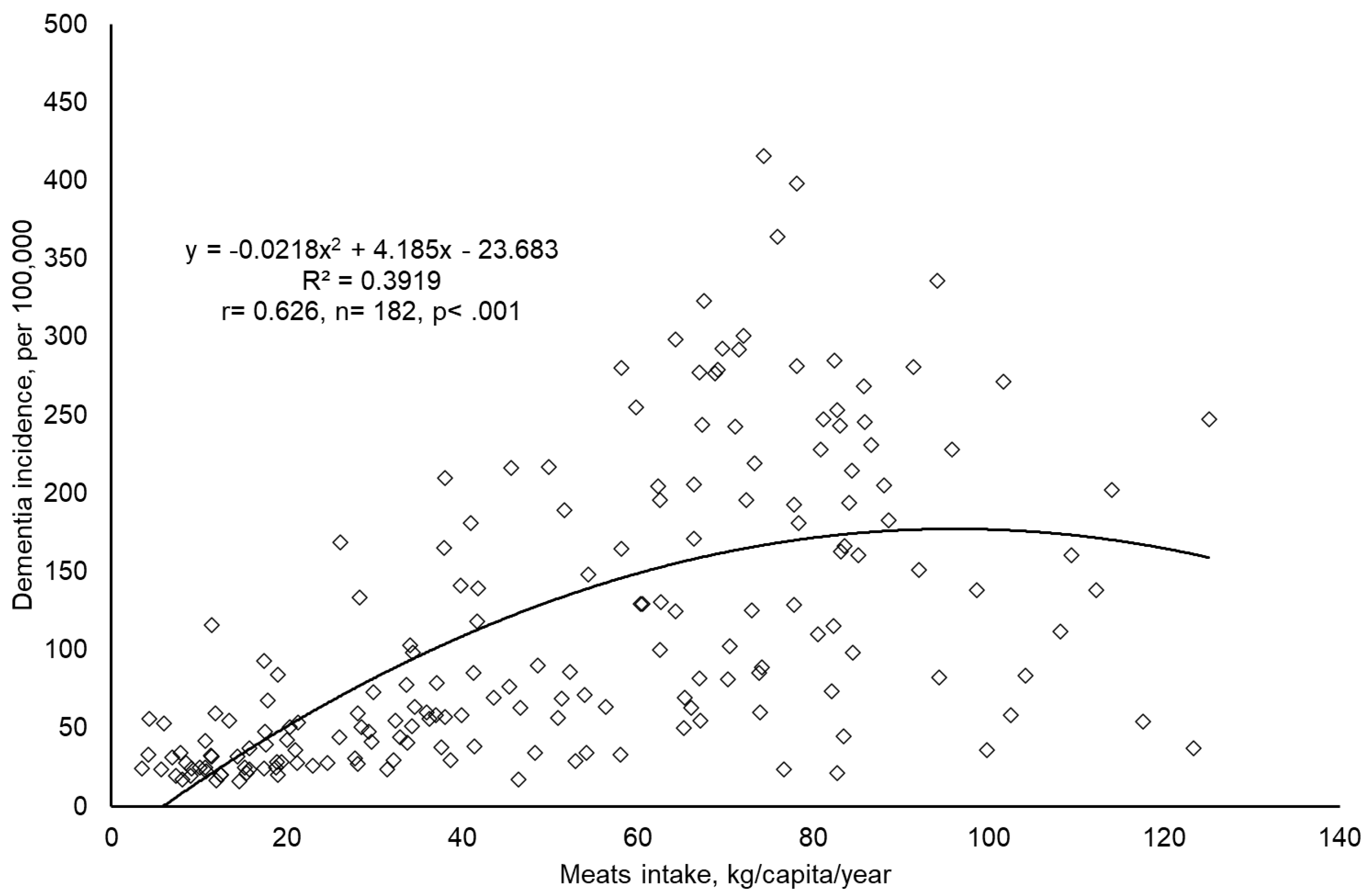

- Initial Data Exploration: Scatter plots were generated using Microsoft Excel® 2016 to visually assess the association between global meat intake and dementia incidence. This preliminary step helped identify any extreme outliers and ensured dataset integrity.

- Bivariate Correlation Analysis: Both Pearson’s and nonparametric methods, were conducted to determine the strength and direction of associations among variables including meat intake, dementia incidence, economic status, genetic predisposition, aging, and urbanization.

- Partial Correlation Analysis: Pearson’s partial correlation was used to explore the relationship between meat intake and dementia incidence while statistically controlling for economic status, genetic predisposition, aging, and urbanization as confounding factors.

- Multiple Linear Regression: A standard (enter) multiple linear regression was performed to delineate the predictive relationship between dementia incidence (dependent variable) and both the main predictor (meat intake) and confounders. This analysis was conducted to evaluate the independent contribution of meat intake in the presence of economic status, genetic predisposition, aging, and urbanization. The regression model quantified the explanatory power of meat intake by comparing results with and without its inclusion as a predictor. Subsequently, stepwise multiple linear regression was applied to identify the most significant predictors of dementia incidence under similar conditions.

-

Regional Correlation Analysis: Bivariate correlations (Pearson’s r and nonparametric) were extended to regional groupings to capture variations in the relationship between meat intake and dementia incidence. The analysis stratified countries according to:

- ○

- World Bank Income Groups: High, upper-middle, lower-middle, and low-income countries. Special attention was given to compare high-income countries with combined low- and middle-income countries, addressing the WHO’s assertion that over 60% of dementia cases occur in LMICs [36]. Fisher’s r-to-z transformation was applied for these comparisons.

- ○

- United Nations Classification: Developed versus developing countries, with correlation differences analyzed using Fisher’s r-to-z transformation to respond to WHO’s regional focus [37].

- ○

- WHO Regional Classifications: Analyses were stratified by regions (Africa, Americas, Eastern Mediterranean, Europe, South-East Asia, and Western Pacific) [38].

- ○

- Cultural and Economic Groupings: Specific country groupings were analyzed, including members of the Asia Cooperation Dialogue (ACD) [39], Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) [40], the Arab World [41], English-speaking countries (based on government data), Latin America [42], Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) [42], Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) [43], and Southern African Development Community (SADC) [44].

Results

Discussion

Limitation of this Study

Conclusion

Data availability

Ethics approval

Competing interests

Author’s contributions

References

- WHO. Dementia. 2023 March 22 2024]; Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia#:~:text=It%20mainly%20affects%20older%20people,high%20blood%20pressure%20(hypertension).

- von Gunten, A., et al., Neurocognitive disorders in old age: Alzheimer’s disease, frontotemporal dementia, dementia with Lewy bodies, and prion and infectious diseases. Primary Care Mental Health in Older People: A Global Perspective, 2019: p. 251-298.

- Wahl, D., et al., Aging, lifestyle and dementia. Neurobiology of disease, 2019. 130: p. 104481.

- Pistollato, F., et al., Nutritional patterns associated with the maintenance of neurocognitive functions and the risk of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: A focus on human studies. Pharmacological research, 2018. 131: p. 32-43. [CrossRef]

- Valls-Pedret, C., et al., Mediterranean diet and age-related cognitive decline: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA internal medicine, 2015. 175(7): p. 1094-1103.

- Aridi, Y.S., J.L. Walker, and O.R. Wright, The association between the Mediterranean dietary pattern and cognitive health: a systematic review. Nutrients, 2017. 9(7): p. 674. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Lapiscina, E.H., et al., Mediterranean diet improves cognition: the PREDIMED-NAVARRA randomised trial. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 2013. 84(12): p. 1318-1325. [CrossRef]

- Bruinsma, J., World agriculture: towards 2015/2030: an FAO study. 2017: Routledge.

- Albanese, E., et al., Dietary fish and meat intake and dementia in Latin America, China, and India: a 10/66 Dementia Research Group population-based study. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 2009. 90(2): p. 392-400.

- Grant, W.B., Trends in diet and Alzheimer’s disease during the nutrition transition in Japan and developing countries. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 2014. 38(3): p. 611-620. [CrossRef]

- Titova, O.E., et al., Mediterranean diet habits in older individuals: associations with cognitive functioning and brain volumes. Experimental gerontology, 2013. 48(12): p. 1443-1448. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H., et al., Meat consumption, cognitive function and disorders: a systematic review with narrative synthesis and meta-analysis. Nutrients, 2020. 12(5): p. 1528. [CrossRef]

- Ylilauri, M.P., et al., Associations of dairy, meat, and fish intakes with risk of incident dementia and with cognitive performance: the Kuopio Ischaemic Heart Disease Risk Factor Study (KIHD). European Journal of Nutrition, 2022. 61(5): p. 2531-2542. [CrossRef]

- Kouvari, M., S. Tyrovolas, and D.B. Panagiotakos, Red meat consumption and healthy ageing: A review. Maturitas, 2016. 84: p. 17-24. [CrossRef]

- Kim, K., et al., Role of total, red, processed, and white meat consumption in stroke incidence and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Journal of the American Heart Association, 2017. 6(9): p. e005983.

- Wang, Z., et al., Impact of chronic dietary red meat, white meat, or non-meat protein on trimethylamine N-oxide metabolism and renal excretion in healthy men and women. European heart journal, 2019. 40(7): p. 583-594. [CrossRef]

- Quan, W., et al., Association of dietary meat consumption habits with neurodegenerative cognitive impairment: an updated systematic review and dose–response meta-analysis of 24 prospective cohort studies. Food & Function, 2022. 13(24): p. 12590-12601. [CrossRef]

- Stadnik, J., Nutritional Value of Meat and Meat Products and Their Role in Human Health. 2024, MDPI. p. 1446. [CrossRef]

- Juárez, M., et al., Enhancing the nutritional value of red meat through genetic and feeding strategies. Foods, 2021. 10(4): p. 872. [CrossRef]

- IHME, Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network. Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 (GBD 2019) Results. 2020, Seattle, United States: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME): http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool.

- The World Bank. How does the World Bank classify countries? 2022 December 24 2022]; Available from: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/378834-how-does-the-world-bank-classify-countries.

- FAO. FAOSTAT-Food Balance Sheet. 2017 November 26 2022]; Available from: http://faostat3.fao.org/.

- The World Bank. Indicators | Data. 2018; Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator.

- Gaziano, T.A., et al., Growing epidemic of coronary heart disease in low-and middle-income countries. Current problems in cardiology, 2010. 35(2): p. 72-115. [CrossRef]

- You, W. and M. Henneberg, Large household reduces dementia mortality: A cross-sectional data analysis of 183 populations. PloS one, 2022. 17(3): p. e0263309. [CrossRef]

- The World Bank. Life expectancy at birth, total (years). 2022 05 April 2022]; Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.LE00.IN.

- You, W. and M. Henneberg, Meat consumption providing a surplus energy in modern diet contributes to obesity prevalence: an ecological analysis. BMC Nutrition, 2016. 2(1): p. 1-11.

- You, W. and M. Henneberg, Meat in modern diet, just as bad as sugar, correlates with worldwide obesity: an ecological analysis. J Nutr Food Sci, 2016. 6(517): p. 4.

- Smith, S., J. Ralston, and K. Taubert. Urbanization and cardiovascular disease- Raising heart-healthy children in today’s cities 2012 December 24 2022]; Available from: https://world-heart-federation.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/FinalWHFUrbanizationLoResWeb.pdf.

- Allender, S., et al., Quantification of urbanization in relation to chronic diseases in developing countries: a systematic review. J Urban Health, 2008. 85(6): p. 938-951. [CrossRef]

- You, W. and F. Donnelly, Physician care access plays a significant role in extending global and regional life expectancy. European Journal of Internal Medicine, 2022. [CrossRef]

- You, W., et al., Cutaneous malignant melanoma incidence is strongly associated with European depigmented skin type regardless of ambient ultraviolet radiation levels: evidence from Worldwide population-based data. AIMS Public Health, 2022. 9(2): p. 378. [CrossRef]

- You, W., R. Henneberg, and M. Henneberg, Healthcare services relaxing natural selection may contribute to increase of dementia incidence. Scientific Reports, 2022. 12(1): p. 1-10. [CrossRef]

- You, W., et al., Gluten consumption may contribute to worldwide obesity prevalence. Anthropological Review, 2020. 83(3): p. 327-348. [CrossRef]

- You, W. and M. Henneberg, Relaxed natural selection contributes to global obesity increase more in males than in females due to more environmental modifications in female body mass. PloS one, 2018. 13(7): p. e0199594. [CrossRef]

- WHO. Dementia. 2023 March 20 2024]; Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia.

- United Nations Statistics Division. Composition of macro geographical (continental) regions, geographical sub-regions, and selected economic and other groupings. 2013 03.10.2016]; Available from: http://unstats.un.org.

- WHO. WHO regional offices. 2018 11.26.2015]; Available from: http://www.who.int.

- Asia Cooperation Dialogue. Member Countries. 2018; Available from: http://www.acddialogue.com.

- Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation. Member Economies-Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation. 2015 [11.26.2015]; Available from: http://www.apec.org.

- The World Bank. Arab World | Data. 2015; Available from: http://data.worldbank.org/region/ARB.

- The United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization. UNESCO Regions-Latin America and the Caribbean. 2014 [11.26.2015]; Available from: http://www.unesco.org.

- OECD. List of OECD Member countries. 2015; Available from: http://www.oecd.org.

- South Africa Development Community. Southern African Development Community: Member States. 2015 [18.06.2015]; Available from: http://www.sadc.int.

- Shiraseb, F., et al., Red, white, and processed meat consumption related to inflammatory and metabolic biomarkers among overweight and obese women. Frontiers in nutrition, 2022. 9: p. 1015566. [CrossRef]

- Ospina-E, J., et al., Substitution of saturated fat in processed meat products: A review. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition, 2012. 52(2): p. 113-122. [CrossRef]

- Buawangpong, N., et al., Increased plasma trimethylamine-N-oxide levels are associated with mild cognitive impairment in high cardiovascular risk elderly population. Food & Function, 2022. 13(19): p. 10013-10022. [CrossRef]

- Xie, L., et al., Research progress on the association between trimethylamine/trimethylamine-N-oxide and neurological disorders. Postgraduate Medical Journal, 2024. 100(1183): p. 283-288. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H., et al., Meat consumption and risk of incident dementia: cohort study of 493,888 UK Biobank participants. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 2021. 114(1): p. 175-184. [CrossRef]

- Ngabirano, L., et al., Intake of meat, fish, fruits, and vegetables and long-term risk of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 2019. 68(2): p. 711-722.

- Barberger-Gateau, P., et al., Fish, meat, and risk of dementia: cohort study. Bmj, 2002. 325(7370): p. 932-933.

- Fischer, K., et al., Prospective associations between single foods, Alzheimer’s dementia and memory decline in the elderly. Nutrients, 2018. 10(7): p. 852. [CrossRef]

- De la Monte, S.M., et al., Epidemiological trends strongly suggest exposures as etiologic agents in the pathogenesis of sporadic Alzheimer’s disease, diabetes mellitus, and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Journal of alzheimer’s disease, 2009. 17(3): p. 519-529.

- Barnard, N.D., A.E. Bunner, and U. Agarwal, Saturated and trans fats and dementia: a systematic review. Neurobiology of aging, 2014. 35: p. S65-S73. [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.-P., et al., High salt induced hypertension leads to cognitive defect. Oncotarget, 2017. 8(56): p. 95780. [CrossRef]

- Roberts, R.O., et al., Relative intake of macronutrients impacts risk of mild cognitive impairment or dementia. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease, 2012. 32(2): p. 329-339. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.-L., et al., Iron and Alzheimer’s disease: from pathogenesis to therapeutic implications. Frontiers in neuroscience, 2018. 12: p. 632. [CrossRef]

- Piñero, D.J. and J.R. Connor, Iron in the brain: an important contributor in normal and diseased states. The Neuroscientist, 2000. 6(6): p. 435-453. [CrossRef]

| Meat intake | Dementia Incidence | Economic Affluence | Genetic Predisposition | Ageing | Urban Living | |

| Meat intake | 1 | .588*** | .622*** | .638*** | .639*** | .562*** |

| Dementia Incidence | .678*** | 1 | .604*** | .606*** | .741*** | .502*** |

| Economic Affluence | .759*** | .777*** | 1 | .567*** | .733*** | .649*** |

| Genetic Predisposition | .751*** | .848*** | .895*** | 1 | .876*** | .523*** |

| Ageing | .682*** | .829*** | .880*** | .930*** | 1 | .604** |

| Urban Living | .578*** | .525*** | .720*** | .630*** | .640*** | 1 |

| Variables | Partial Correlation to Dementia Incidence | Partial Correlation to Dementia Incidence | ||||

| r | P | df | r | p | df | |

| Meat intake | .227 | < .010 | 170 | - | - | - |

| Economic Affluence | - | - | - | .376 | <.001 | 173 |

| Genetic Predisposition | - | - | - | .372 | <.001 | 176 |

| Ageing | .587 | <.001 | 178 | |||

| Urban Living | - | - | - | .257 | <.001 | 178 |

| Table 3-1: ENTER | Excluding Meat Intake | Including Meat Intake | |||

| Variables Entered | Beta | Sig. | Beta | Sig. | |

| Meats intake | Not added | Not applicable | .202 | < .001 | |

| Economic Affluence | .063 | .447 | .082 | < .010 | |

| Genetic Predisposition | - .141 | .201 | - .183 | .344 | |

| Ageing | .788 | < .001 | .721 | .113 | |

| Urban Living | .043 | .525 | - .017 | < .001 | |

| Table 3-1: STEPWISE | Meat Intake not Added | Meat Intake Added | |||

| Rank | Variables Entered | Adjusted R Square | Rank | Variables Entered | Adjusted R Square |

| 1 | Ageing | .539 | 1 | Ageing | .544 |

| Meats Intake | Not significant | 2 | Meats Intake | .563 | |

| Genetic Predisposition | Not significant | 3 | Genetic Predisposition | .571 | |

| Economic Affluence | Not significant | Economic Affluence | Not significant | ||

| Urban Living | Not significant | Urban Living | Not significant | ||

| Country Groupings | Pearson r | p | Nonparametric | p | n |

| Worldwide | .588 | < .001 | .678 | < .001 | 182 |

| United Nations common practice | |||||

| Developed countries | .098 | .526 | - .004 | .978 | 44 |

| Developing countries | .496 | . < .001 | .604 | < .001 | 138 |

| Fisher r-to-z transformation | Developing vs Developed:z= 2. 5, p < .010 | Developing vs Developed:z= 3.94, p < .001 | |||

| World Bank income classifications | |||||

| High Income (HI) countries | -.073 | .598 | -.129 | .353 | 54 |

| Low Income (LI) countries | .184 | .349 | .236 | 0.226 | 28 |

| Low Middle Income (LMI) countries | .368 | < .010 | .478 | < .001 | 49 |

| Upper Middle Income (UMI) countries | .198 | .165 | .260 | .066 | 51 |

| Low- and middle-income countries (LI, LMI, UMI) | .521 | < .001 | .668 | < .001 | 128 |

| Fisher r-to-z transformation | Low- and middle-income vs High: z= 3.92, p< .001 | Low- and middle-income vs High: z= 5.64, p< .001 | |||

| WHO regions | |||||

| African region countries | .587 | < .001 | .453 | < .010 | 45 |

| American region countries | .578 | < .001 | .590 | < .001 | 35 |

| Eastern Mediterranean region countries | - .095 | .682 | .113 | .626 | 21 |

| European region countries | .471 | < .001 | .348 | < .050 | 50 |

| South-East Asian Region countries | .197 | .585 | .321 | .365 | 10 |

| Western Pacific Region countries | .302 | .183 | .183 | .427 | 21 |

| Countries grouped with various factors | |||||

| Asia Cooperation Dialogue (ACD) | .150 | .456 | .002 | .990 | 27 |

| Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) | .658 | < .010 | .696 | < .010 | 17 |

| Arab World | - .185 | .423 | - .061 | .793 | 21 |

| English as official language (EOL) | .651 | < .001 | .775 | < .001 | 51 |

| Latin America (LA) | .640 | < .001 | .723 | < .001 | 23 |

| Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) | .491 | < .010 | .538 | < .001 | 33 |

| Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) | - .035 | .838 | - .143 | .407 | 36 |

| Southern African Development Community (SADC) | .685 | < .010 | .553 | < .050 | 16 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).