1. Introduction

Cavitation is a phenomenon which can be usually occurs in ship and hydraulic systems, in biochemical and biomedical and ultrasonic systems, and other industrial applications. The cavitation can be generated in the systems in the form of cluster of tiny bubbles in the size of nanoscale, microscale and macroscale. The formation and collapse of the cavitation bubbles may have negative and positive effects in various applications. As example, the cavitation bubbles can be generated near the surface of immersed bodies and may cause damage on the wall surface of the bodies such as corrosion and erosion on the hydrofoils, ship propellers and rudders, turbine blades and pump impellers and so on. In these cases, the cavitation bubbles may reduce the performance of the ship and hydraulic systems in cavitating regimes (Reisman et al. [

1], Dular et al. [

2], Patella et al. [

3], Huang et al. [

4], Kadivar et al. [

5], Köksal et al. [

6] and Lin et al. [

7]. In addition to the negative effects of cavitation bubbles, there are also some positive effects in biochemical and biomedical systems. The cavitation bubbles can be used for water and wastewater treatment, drug delivery, virus inactivation, energy harvesting, heating systems, surface cleaning and other important applications. Some of the numerous advantageous applications were investigated in the previous works [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. In the real applications, the cavitation phenomenon and generation of tiny bubbles may be affected due to the irregular and regular roughness of the boundaries [

13,

14,

15], viscosity of the liquid [

16], density and radius of the nuclei in the system [

17], ambient temperatures [

18], and the size of the bubble such as nanobubble near a surface [

19]. Before the review of the previous works in the fields of simulation of nanobubble dynamics using Molecular Dynamics Simulation (MD), a short review of the experimental studies and numerical simulations of the bubble dynamics in macroscale was presented in this work.

1.1. Experimental Study of Bubble Dynamics

The cavitation bubbles can be generated within the liquids such as water through various mechanisms. One of well-known mechanism for generation of cavitation or cavitation bubbles is the reduction of local pressure below the saturated vapour pressure of the liquid [

20]. This mechanism usually occurs under natural conditions for a flow with high velocity inside or outside of ship components or hydraulic systems. Other methods of bubble generation are usually occurred in the laboratory conditions such as application of a laser pulse [

21] for formation of plasma-induced cavitation bubble. In addition to the plasma-induced bubbles, an electric spark [

22], or a high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) [

23] can be also used for generation of the cavitation bubble in the laboratory conditions. The laser-induced cavitation bubbles have been utilized in numerous foundational investigations on the bubble dynamics since the 1970s [

24,

25]. Using a laser, the cavitation bubble can be generated through heating up a small amount of a liquid in a specific location. In addition, the cavitation bubble can be induced due to the presentation of the electrodes in the liquid. However, the drawback of the spark-induced bubble is the intrusive nature of this method, [

26]. Numerous studies have been conducted regarding the dynamics of bubbles in the free field conditions and near different boundaries such as rigid surface [

27,

28,

29], mesoscale surface structuring [

30,

49], free surfaces [

31,

32,

33,

34] and flexible boundaries [

35,

36,

37].

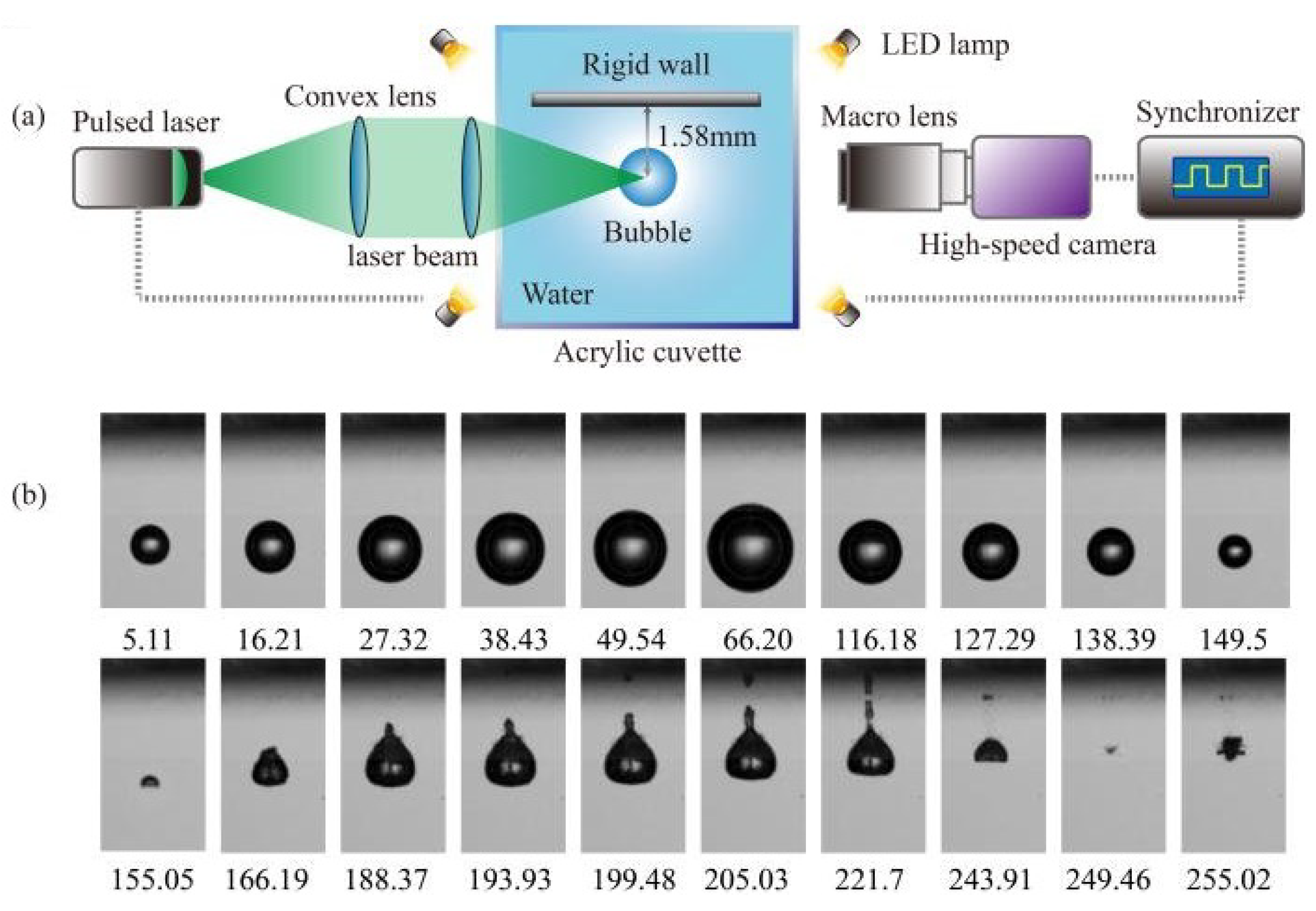

Figure 1 illustrates a schematic view of an experimental setup of the laser-induced cavitation bubble near a rigid surface and some high-speed images of the laser-induced cavitation bubble.

Previous numerical and experimental works dealt mostly with the study of the single cavitation bubble or multiple bubbles in the scale of the mesoscale or macroscale. The generation of the bubbles are mostly occurred with the application of a laser pulse [

21,

38], an electric spark [

22], acoustic waves and utilization of high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) [

23,

39,

40] in free field and near boundaries in the previous studies. The dynamics of laser-induced single cavitation bubble near solid boundaries were studied by researchers Lauterborn et al. [

25], Philipp and Lauterborn [

41] Tomita and Shima [

42], Koch [

43], Kadivar et al. [

30] and Dular et al. [

44]. They experimentally investigated the single cavitation bubble and its undesirable effects, such as erosion on different solid surfaces. They usually used a shadowgraph technique with high-speed camera to capture the dynamics of the bubble near the boundaries. Their results demonstrated that a microjet can be formed during the collapse process of the single bubble near a solid surface. They demonstrated that the microjet can play an important role for the formation of the erosion on the solid boundary during several successive bubble collapses. In addition, they presented that a toroidal cavity structure can be generated after the first and second collapses which can induce more damage or erosion on the solid surface. The reason could be due to the collapse of a cluster of tiny bubbles in the toroidal cavity structures after the collapse stages.

Vogel and Lauterborn [

46] indicated that a significant pressure impact can be formed during the first collapse of a laser-induced single cavitation bubble. Their results revealed that the pressure impact on the boundary can be reached in the range of 60 kbar from a single cavitation bubble collapse. They showed that a major part of the energy of the cavitation bubble collapse may be converted to acoustic energy for different conditions. Tomita et al. [

47] performed an experimental study of a laser-induced bubble close to a curved solid boundary and indicated that the bubble collapse dynamics and the direction of the microjet may be manipulated by the curvature effect of the the solid boundary. Lindau and Lauterborn [

48] investigated the dynamics of a single cavitation bubble near a solid surface and their findings demonstrated that a counter-jet can be generated in the rebound stage of the bubble collapse for a special relative wall distance. Kadivar et al. [

49], studying the dynamics of a laser-induced single bubble near a riblet structure, showed that the microjet may be influenced by the riblet structure at different relative wall distances. In other words, the riblet structures can reduce the cavitation-induced erosion of the bubble collapse on the solid boundary.

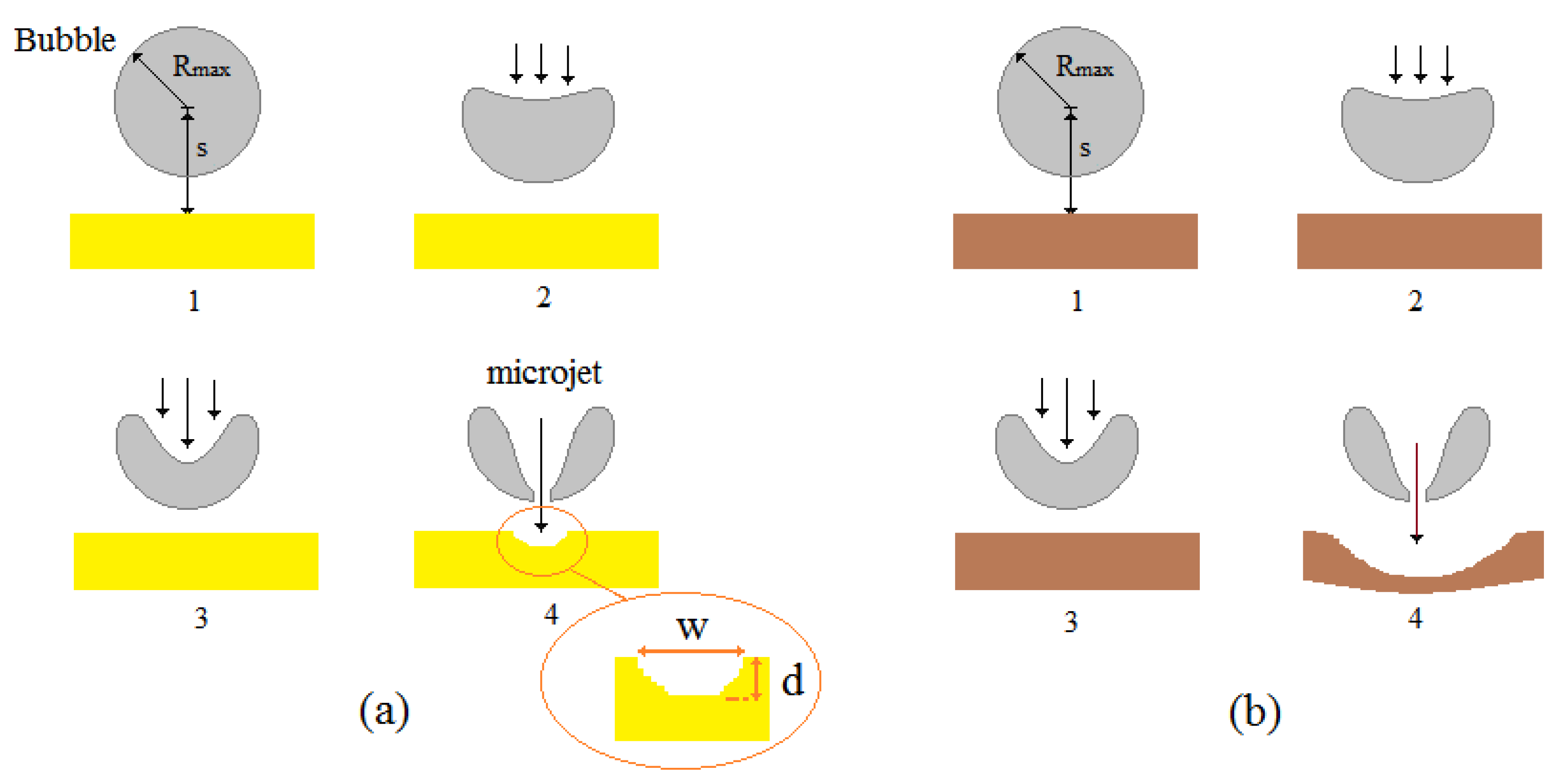

Figure 2 illustrates a schematic view of the expected collapse dynamics of a single cavitation bubble located close to a solid surface and a flexible surface. The parameters

and

d in the images represent the maximum bubble radius and the distance between the bubble center and the solid or flexible surface. The parameter

d and

w show the depth and width of the erosion area on the solid boundary which can be induced due to the bubble collapse on the wall surface. The non-dimensional parameter

known as relative wall distance which is defined the ratio of the distance of the bubble center to the solid or flexible surface and the maximum bubble radius

. As the schematic images shows, the shape of the erosion area on the flexible and solid boundaries may be different. The reason can be due to various material properties of the surfaces and the momentum of the microjet which can be formed during the bubble collapse process on the flexible and solid surfaces.

1.2. Numerical Approaches of Cavitation Bubble Simulation in Macroscale

Before discussion of the numerical approaches, it can be mentioned that there are some analytical methods employed to study the bubble collapse dynamics such as Rayleigh-Plesset, Gilmore equations or a unified theory [

45,

50,

51]. These equations can provide valuable physical insights for understanding of the cavitation bubble formation and collapse dynamics in macroscale. However, they often require different adjustments for consideration of the phase transition, thermodynamic effects, compressibility, threshold of the cavitation or cavitation inception, and bubble lifetime [

52,

53]. In addition, the flow around the bubble during the collapse stage can not be calculated in the analytical methods. Furthermore, the erosion induced by the bubble collapse, roughness of the boundary and interphase of vapor and air phases can not be considered in the analytical calculation. Therefore, the computational method is usually based on Navier-Stokes equations for modelling the dynamics of bubble formation and collapse [

54,

55,

56,

57]. However, corrosion and chemical reaction, phase transition, erosion on the boundaries and molecular effects cannot be fully simulated using these governing equations. Furthermore, the smaller scales such as nanoscales may not be captured due to the continuum-based approach of the Navier-Stokes equations. Regarding the simulation of the bubble in macroscale, different numerical studies were performed using Navier-Stokes equations to simulate the bubble formation, expansion and collapse, Huang et al. [

58,

59,

60]. Zhang and Liu [

61] improved three-dimensional bubble dynamics model based on boundary element method.

1.2.1. Molecular Dynamics Simulations (MD) Method

A numerical simulation on the atomic or molecular scale is a powerful and accurate method to successfully describe physical properties which depend on the velocities and positions of ions [

94]. The physical and chemical characteristics of a system comprising more than thousands of atoms can be investigated using the molecular dynamics (MD) method in nanometer size and at nanosecond or picosecond time duration [

95]. During the past decade, researchers successfully used the MD approach to study nano-bubble dynamics. In the previous works, the MD method was used to probe nanobubble shrinkage, shock-induced nanobubble collapse, and the effects of ambient temperature on the nanobubble’s collapse. A large-scale atomic/molecular massively parallel simulator (LAMMPS) program [

96] was mostly used to perform all computer simulations of molecular dynamics and an open tool software (OVITO) [

97] was mainly used to visualize the results, see [

69].

In the most of the previous investigations, a momentum mirror protocol was usually performed by the researchers to model the shock-wave formation inside the system for bubble collapse dynamics in the molecular dynamics simulations, [

62,

64,

65,

66]. In addition, the voids of the bubble surface are often created by simply removing fluid molecules within a spherical region or gas-filled bubbles by filling the bubble with a gas in most of the previous works using MD simulation, [

67]. Rawat and Mitra [

68] investigated the nanobubble collapse in water with two different types of bubble creation. They used empty bubble and bubble filled up by

. The compared theses two methods of bubble formation and indicated that

gas within the bubble may lead to an enhancement of the bubble collapse time. In addition, they found that the pressure and temperature rising of the bubble collapse is high for the empty bubble compared to gas-filled bubble. Furthermore, it was shown that the

gas-filled bubble may be dissociated during the collapse process whereas the empty bubble can be remained intact.

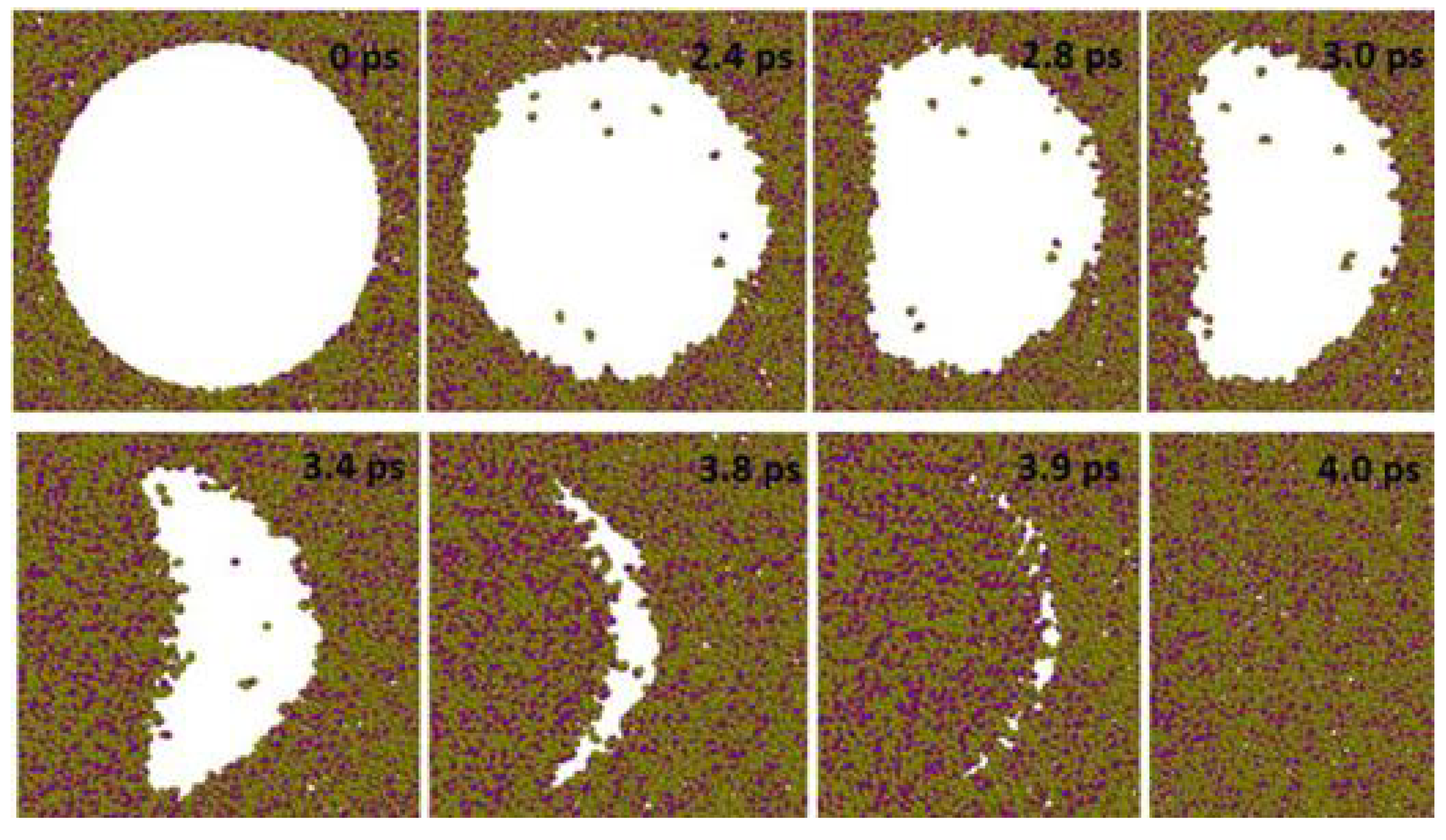

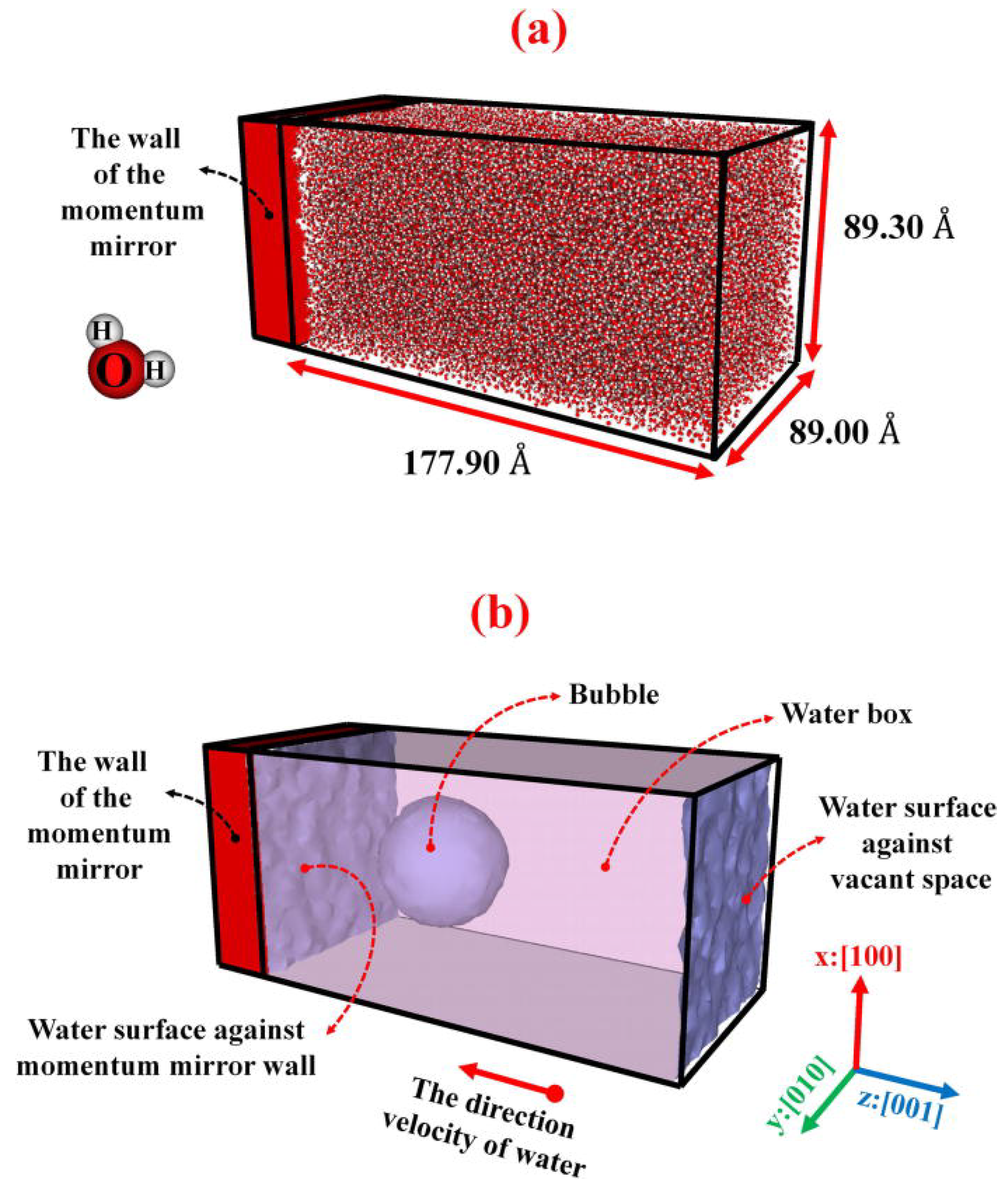

Figure 3 shows the empty nanobubble dynamics during it’s compression and collapse at different time steps.

In the momentum mirror protocol, the simulation box walls in one specific direction can be selected a a mirror wall. That means the component of particle velocity toward the mirror wall will be reversed when the particles cross this mirror wall. Therefore, a shock wave can be formed in the opposite direction of the initial velocity direction. Finally, the generated shock wave can collide with the surface of the bubble and the collapse of the nanobubble will be occurred. In this protocol, the mirror wall is usually considered as a rigid plane which can only reverse the particle velocity towards the plane in one direction. When the nanobubble dynamics near a solid boundary will be studied, the collision of the shock wave with the nanobubble caused collapse of the nanobubble and formation of a nanojet toward the solid surface.

As example,

Figure 4 illustrates the schematic view of the nanobubble, water surface, and mirror wall under the mirror protocol, [

89]. The image

Figure 4 (a) shows the atomic view of the water box at the first stage of the MD simulation and the image

Figure 4 (b) presents the water box after formation the nanobubble. Here, the surface mesh view was used to show the nanobubble surface in the system. The nanobubble radius and the particle velocities in the −z:[00] direction was considered as 2.5 nm and 3 km/s, respectively. Therefore, the shock wave was formed and propagated in the z:[00

] direction.

There is another protocol to generation of required shock-wave inside the system regarding the collapse of the bubble which is known as real wall protocol [

89]. In this method, the researchers considered an aluminum (Al) slab as a real wall instead of the mirror wall. Their results indicated that the real wall can react with the water molecules. They found that the bubble shrinkage and collapse dynamics in the real wall protocol may be similar to the mirror wall protocol; however, a sooner nanobubble collapse can be reached in the real wall protocol. In addition, a type of water vortices and creation of an amorphous layer behind the nanojet can be formed during the nanobubble collapse in the real wall protocol.

1.3. Molecular Dynamics Simulation (MD) of Cavitation Bubble in Nanoscale

In the case of the simulation of nanobubble, the measurement of the attributes of the dynamic of the nanobubble using experimental approaches or other numerical simulation is difficult. The reason is due to the very small size of the nanobubble, the short nanobubble collapse duration and the complex experimental techniques for capturing the quantitative parameters of the bubble dynamics. For the simulation of bubble in nanoscale, the previous studies mostly used a Molecular Dynamics (MD) based method to overcome experimental restrictions [

62,

63,

64,

65,

66]. In addition, the MD method can overcome some of the limitations which are mentioned for simulation of the bubble using other computational methods such as Navier-Stokes equations, [

67,

69,

70]. Using the molecular dynamics (MD) simulation, different works were performed to investigate the collapse dynamics of bubbles with a radius in the range of the nanoscale. Matsumoto et al. [

71] investigated the dynamic of the nanobubble collapse in a liquid using MD simulations. They considered a system with Lennard-Jones liquid and a nanobubble containing gas of soft core particles. Their results showed significant heat and mass transfer on the nanobubble surface after the compression of the system. Xiao et al. [

72] indicated that the local temperature of the fluid inside the nanobubble during the collapse phase can be increased up to five times the system temperature surrounding the nanobubble. In addition, the researchers already found that the local water temperature can be increased significantly during the nanobubble collapse in the range of 4000 K, Lugli et al. [

73]. They indicated that the duration of a nanobubble collapse may be in 1-10 picoseconds.

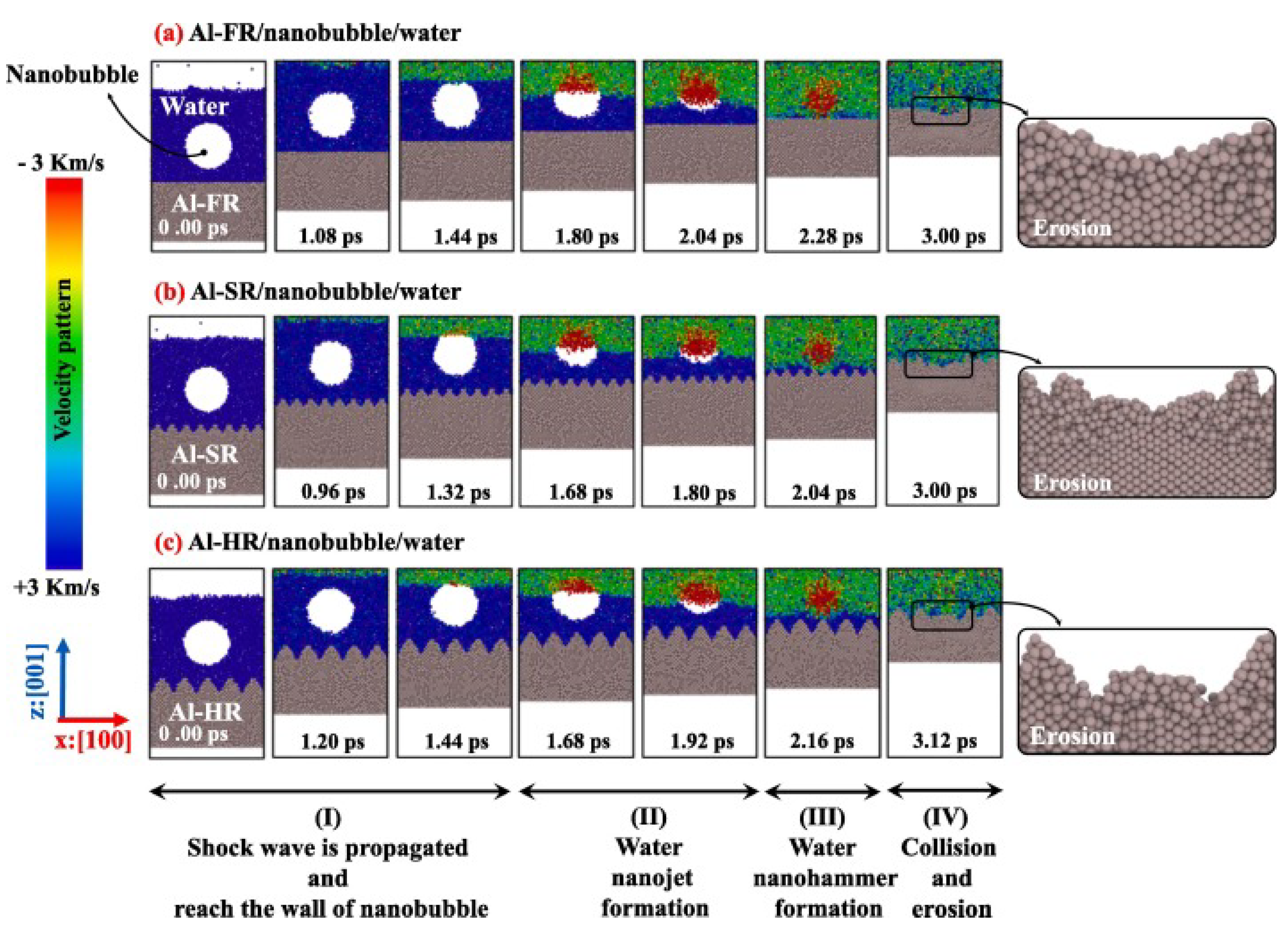

Figure 5 shows a result of velocity contours of nanobubble near an aluminum slab with and without rough boundaries. In the images the shock wave propagation, nanojet and nanohammer generation, and surface erosion can be observed for each cases.

Ikemoto et al. [

75] performed the MD simulation to study the conditions inside a nanobubble. Their results revealed that the nanobubble can be formed by negative pressure formation in the simple Lennard-Jones system. Matsumoto [

76] studied the surface tension and nanobubble stability in a liquid using a MD simulations. Their results revealed that large negative pressure region can be observed from the behavior of the liquid in the surrounding the nanobubble. Sekine et al. [

77] investigated a liquid-vapor nucleation of Lennard-Jones fluid using MD simulations. They studied the nanobubble formation, nanobubble collapse and boiling process. Liu et al. [

78] studied a flexible water model using molecular dynamics simulations. The effect of shock waves on the collapse of nanobubble and generation of the nanojet in a system using MD simulation was performed by Vedadi et al. [

62]. Their results showed a relationship between the nanojet’s behavior and the nanobubble’s radius during the collapse process of the nanobubble. The cavitation nanobubble dynamics was studied using MD simulations with assuming a hard sphere model for the species inside the nanobubble by Schanz et al. [

79]. A shock wave collision with a nanobubble was investigated using MD simulations by Zhan et al. [

66]. In their results, the formation of a nanojet was found which can be induced the erosion on the solid surface due to the effects of the nanojet impact.

In some of the previous works, the effects of nanobubbles on the lipid or amorphous silica using the MD simulations were investigated. For example, Nomura et al. [

80] performed the reactive molecular dynamics simulations to investigate the shock-induced by the collapse of the nanobubble close to the amorphous silica boundary in water. They indicated that a water jet can be generated in the nanobubble collapse stage. In addition, their results showed formation of a hemispherical pit on the surface due to the nanojet impact on to the silica boundary. Shekhar et al. [

81] investigated the dynamics of the nanobubble dynamics near a silica boundary using billion-atom reactive molecular dynamics simulations. They analyzed the shock-induced collapse of nanobubble on the boundary. Their results showed that the collapse of a nanobubble can generate a nanojet with very high velocity toward the surface which causes a pit on the silic boundary. Sun et al. [

82] studied the effect of the shock wave velocity on the nanobubble collapse dynamics near a membrane using MD simulations. Their results showed that a deformation can be formed on the membrane due to the water nanojets during the nanobubble collapse stage. They found that the pores on the membrane can be generated when the shock velocities are sufficiently high.

Choubey et al. [

63] performed the MD simulations to study the nanobubble collapse dynamics and formation of the deformation on the lipid bilayers. They found the impact of a nanojet on the lipid bilayers can induce a significant damage on the lipid bilayers. Santo and Berkowitz [

64] studied the shock wave induced by the collapse of arrays of nanobubbles near a lipid membrane. They used a coarse-grained molecular dynamics simulations and their results revealed that the impact of the shock waves on the nanobubbles may induce the nanobubble collapse and generate a nanojet near the lipid membrane. In addition, they indicated that the pores can be formed on the lipid surface due to the impact of the nanojet on the lipid boundary. Adhikari et al. [

65] and Nan et al. [

83]) studied the shock wave-induced nanobubble collapse dynamics near a lipid membrane using coarse-grained MD simulations. They assessed the extent of damage induced by the collapse of the nanobubble. In addition, their results showed that the holes on the membrane can not be created in the absence of bubbles. The effects of cavitation nanobubble collapse on the cell membrane’s integrity was studied by Becton et al. [

84] using MD simulations. They found that the the kinetic energy of the shock wave in a small section on the membrane can penetrate at the edge of the cell membrane.

Wu and Adnan [

85] performed the MD simulations to study the effects of a nanobubble collapse on the structure of a neural network of the brain. They discussed about the effects of the size and location of the nanobubble and shock wave induced damage on the structures. Hong et al. [

86] investigated the MD simulations to analyze the stability of the nanobubbles in water. They indicated that the interbubble distance should be smaller than the maximum interbubble distance for stabilization of the nanobubbles with a certain diameter. Zhou et al. [

87] studied the exfoliation of the Mo

layers induced by the nanobubble collapse using MD simulations. They found that in the collision stage of the nanojet with Mo

layers, the surface temperature and pressure may reach a range up to 3000 K and 20 GPa, respectively. Hu et al. [

88] investigated the creation of holes in a bio-membrane induced by shockwave multiple nanobubble collapse in presence of electric fields using MD simulations. Ghoohestani et al. [

89] performed MD simulations to study the reactive-dynamic characteristic of a nanobubble near a solid boundary. They demonstrated that the collision of a shock wave with the nanobubble may induce the collapse of the nanobubble. In addition, their results showed the formation of a nanojet in the nanobubble collapse process.

Zhang et al. [

90] studied the nanobubble cavitation as an effective method for the degradation of polyacrylamide (PAM) wastewater using MD simulation. Their results indicated that the collapse of nanobubbles may induce high-velocity jets in the central region and may generate a deformation of PAM molecular chains. Jiang et al. [

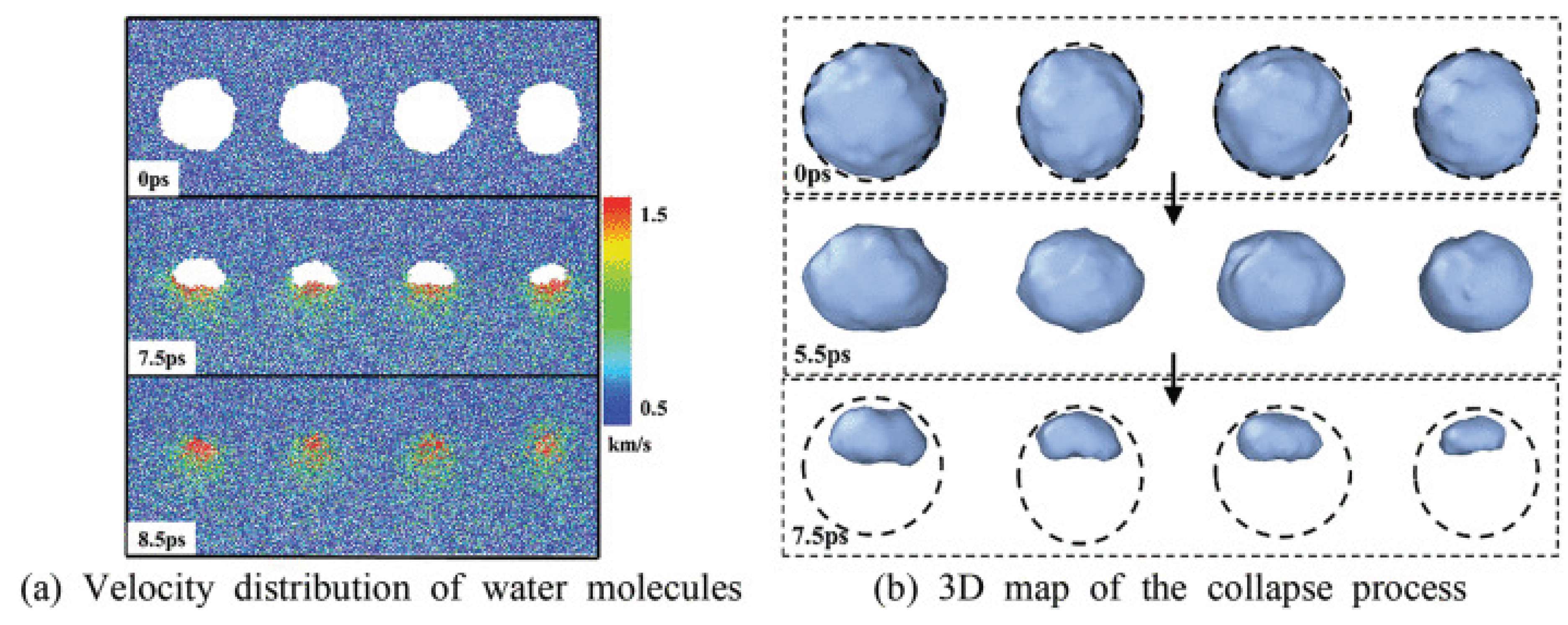

91] investigated the shockwave-induced multi-bubble collapse and its development and evolution process using MD simulation. They found that more energy can be released for a greater number of bubbles. In addition, their results showed that the collapse speed of two sides bubbles may be greater than that of the middle bubble, and the collapse time of the the middle bubble is longer than the collapse time of the two sides bubbles.

Figure 6 shows a velocity distribution and a 3D map of the multiple-bubble collapse process dynamics.

Xu et al. [

92] performed a MD simulation with a coarse-grained force field to study the collapse dynamics of double bubbles with a distance in vertical line. They indicated that the collapse time of the bubble locating above of the other bubble can gradually increase with the increase of the bubble distance. In addition, their finding revealed that the collapse time of the bubble locating below the other bubble may be faster than that of the bubble located on top the first bubble. Tan et al. [

93] studied the dynamic behavior of nano-bubbles near a boundary of single crystal iron (Fe) using molecular dynamics simulations. They found that the nano-bubble diameter is inversely correlated with impact pressure. In addition, their findings showed that the cavitation erosion may induce a structural evolution of iron atoms from bcc to fcc and hcp structures.

2. Conclusions and Perspectives

In this review, an overview of the previous works on the simulation of the nanobubble dynamics using molecular dynamics simulation was presented. The following aspects can be summarized form the previous works:

The previous experimental works of the bubble dynamics were mostly performed by using a laser for generation of the bubbles in mesoscale or millimeter-scale under ambient and free conditions. However, an electric spark or acoustic waves were also used to generate the bubbles near boundaries in the previous studies.

Different analytical approaches such as Rayleigh-Plesset, Gilmore equations and continuum-based approaches like Navier-Stokes equations were used to study the bubble dynamics in macroscale. However, they often require different adjustments for consideration of the phase transition, thermodynamic effects, compressibility, threshold of the cavitation or cavitation inception. In addition, corrosion and chemical reaction, phase transition, bubble induced-erosion on the surfaces and molecular effects cannot be fully simulated using these approaches.

Therefore, the molecular dynamics simulations (MD) can be a powerful numerical simulation method to successfully describe the physical properties of the bubble in nanoscale. A large-scale atomic/molecular massively parallel simulator (LAMMPS) program was widely used in the previous works to perform the simulations of the nanobubble dynamics.

Two different protocols for the generation of required shock-wave inside the system regarding the collapse of nanobubble collapse dynamics were used mostly in the previous works known as mirror wall protocol and real wall protocol. The nanobubble collapse dynamics in the real wall protocol was similar to the mirror wall protocol. However, a form of water vortices and an amorphous layer behind the nanojet can be formed during the nanobubble collapse in the real wall protocol.

Tow different ways were mostly performed for formation of the nanobubble in a MD system. The first one is the voids of the bubble surface which are often created by simply removing fluid molecules within a spherical region. The second way is gas-filled bubbles by filling the bubble with a gas. However, one can see here is a lack of nanobubble simulation studies in which molecular dynamics simulations are better consistent with the experimental observation of the laser-induced bubble. That means, a type of laser-liquid interactions in the LAMMPS or other codes for the MD simulation can be considered in the future for better simulation of the nanobubbles behavior, and the related physical phenomena in a proper way.

In other words, a laser pulse can be simulated directed at the center of a water box in MD simulation for transformation of the laser energy to the water molecules inside a specific region for the future works. In this approach, a hot plasma with a high pressure can be formed and the plasma energy through collision cascades within the water medium may generate a plasma-induced shock wave. Through the dissipation of this plasma shock in a very short time, a nanobubble can be nucleate.

Most of the previous works used the coarse-grained molecular dynamics simulations for the studying of nanobubble dynamics. However, the proposed algorithm and the obtained results can be improved through all-atom and reactive simulations in the future works.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Reisman, G.; Wang, Y.; Brennen, C. Observations of shock waves in cloud cavitation. J. Fluid Mech. 1998, 355, 255–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dular, M.; Bachert, B.; Stoffel, B.; Sirok, B. Relationship between cavitation structures and cavitation damage. Wear 2004, 257, 1176–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patella, R.; Choffat, T.; Reboud, J.; Archer, A. Mass loss simulation in cavitation erosion: Fatigue criterion approach. Wear 2013, 300, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, G. Large eddy simulation of turbulent vortex-cavitation interactions in transient sheet/cloud cavitating flows. Comput. Fluids 2014, 92, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadivar, E. Experimental and Numerical Investigations of Cavitation Control Using Cavitating-Bubble Generators. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Duisburg-Essen, Duisburg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Koeksal, Ç.; Usta, O.; Aktas, B.; Atlar, M.; Korkut, E. Numerical prediction of cavitation erosion to investigate the effect of wake on marine propellers. Ocean Eng. 2021, 239, 109820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Kadivar, E.; Moctar, O.; Neugebauer, J.; Schellin, T. Experimental investigation on the effect of fluid–structure interaction on unsteady cavitating flows around flexible and stiff hydrofoils. J. Phys. Fluids 2022, 34, 083308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrie, A. , Brisken, A., Francis, S., Cumberland, D., Crossman, D. & Newman, C. Microbubble-enhanced ultrasound for vascular gene delivery. Gene Therapy. 2000, 7, 2023–2027. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, S. , Cocks, F., Preminger, G. & Zhong, P. The role of stress waves and cavitation in stone comminution in shock wave lithotripsy. Ultrasound In Medicine & Biology. 2002, 28, 661–671. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, D. , Palanker, D., Huie, P., Miller, J., Marmor, M. & Blumenkranz, M. Intravascular drug delivery with a pulsed liquid microjet. Archives Of Ophthalmology. 2002, 120, 1206–1208. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Marmottant, P.; Hilgenfeldt, S. Controlled vesicle deformation and lysis by single oscillating bubbles. Nature. 2003, 423, 153–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkink, R.; Ohl, C. Laser-induced cavitation based micropump. Lab On A Chip. 2008, 8, 1676–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arndt, R.; Ippen, A. Cavitation near surfaces of distributed roughness. Massachusetts Institute Of Technology Cambridge. ( 1967.

- Kadivar, E. el Moctar, A. Investigation of cloud cavitation passive control method for hydrofoils using Cavitating-bubble Generators (CGS). International Cavitation Symposium (CAV2018), Baltimore, MD, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Churkin, S.A.; Pervunin, K.S.; Kravtsova, A.Y.; Markovich, D.M.; Hanjalić, K. Cavitation on NACA0015 hydrofoils with different wall roughness: High-speed visualization of the surface texture effects. Journal of Visualization. 2016, 19, 587–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iga, Y. , Okajima, J., Yamagichi, Y., Sasaki, H. & Ito, Y. Thermodynamic suppression effect of cavitation arising in a hydrofoil in 140 °C hot water. Journal Of Fluids Engineering. 2023, 3145, 011207. [Google Scholar]

- Venning, J. , Pearce, B. & Brandner, P. Nucleation effects on cloud cavitation about a hydrofoil. Journal Of Fluid Mechanics. 2022, 947, 011207. [Google Scholar]

- Phan, T. , Kadivar, E., Nguyen, V., Moctar, O. & Park, W. Thermodynamic effects on single cavitation bubble dynamics under various ambient temperature conditions. J. Phys. Fluids. 2022, 34, 023318. [Google Scholar]

- Ghoohestani, M. , Rezaee, S., Kadivar, E. & Moctar, O. Thermodynamic effects on nanobubble’s collapse-induced erosion using molecular dynamic simulation. Physics Of Fluids. 2023, 35, 073319. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, S. , Lautz, J., Sankin, G., Szeri, A. & Zhong, P. Bubble proliferation or dissolution of cavitation nuclei in the beam path of a shock-wave lithotripter. Physical Review Applied. 2015, 3, 034002. [Google Scholar]

- Akhatov, I. , Vakhitova, N., Topolnikov, A., Zakirov, K., Wolfrum, B., Kurz, T., Lindau, O., Mettin, R. & Lauterborn, W. Dynamics of laser-induced cavitation bubbles. Experimental Thermal And Fluid Science. 2002, 26, 731–737. [Google Scholar]

- Obreschkow, D. , Kobel, P., Dorsaz, N., De Bosset, A., Nicollier, C. & Farhat, M. Cavitation bubble dynamics inside liquid drops in microgravity. Physical Review Letters. 2006, 97, 094502. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, L. , Xu, W., Zhong, T. & Li, N. A high-speed photographic study of ultrasonic cavitation near rigid boundary. Journal Of Hydrodynamics, Ser. B. 2008, 20, 637–644. [Google Scholar]

- Lauterborn, W. High-speed photography of laser-induced breakdown in liquids. Applied Physics Letters. 1972, 21, 27–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauterborn, W.; Bolle, H. Experimental investigations of cavitation-bubble collapse in the neighbourhood of a solid boundary. J. Fluid Mech. 1975, 72, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, J. , Gleeson, A., Roberts, R. & Rogers, R. A spark-generated bubble model with semi-empirical mass transport. The Journal Of The Acoustical Society Of America. 1997, 101, 1908–1920. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q. , Liu, W., Zhang, A. & Sui, Y. Bubble dynamics in very close to a rigid boundary. Interface Focus. 2015, 5, 20150048. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S. , Han, R., Zhang, A. & Wang, Q. Analysis of pressure field generated by a collapsing bubble. Ocean Engineering. 2016, 117, 22–38. [Google Scholar]

- Kadivar, E. , Phan, T., Park, W. & Moctar, O. Dynamics of a single cavitation bubble near a cylindrical rod. Physics Of Fluids. 2021, 33. [Google Scholar]

- Kadivar, E. , Moctar, O. & Sagar, H. Experimental study of the influence of mesoscale surface structuring on single bubble dynamics. J. Ocean Engineering. 2022, 260, 111892. [Google Scholar]

- Saleki-Haselghoubi, N. , Shervani-Tabar, M., Taeibi-Rahni, M. & Dadvand, A. Numerical study on the oscillation of a transient bubble near a confined free surface for droplet generation. Theoretical And Computational Fluid Dynamics. 2014, 28, 449–472. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, N. , Wu, W., Zhang, A. & Liu, Y. Experimental and numerical investigation on bubble dynamics near a free surface and a circular opening of plate. Physics Of Fluids. 2017, 29. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, T. , Baac, H., Ok, J., Youn, H. & Guo, L. Nozzle-free liquid microjetting via homogeneous bubble nucleation. Physical Review Applied. 2015, 3, 044007. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S. , Zhang, A. & Wang, S. Experimental and numerical studies on “crown” spike generated by a bubble near free-surface. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Goh, B. , Gong, S., Ohl, S. & Khoo, B. Spark-generated bubble near an elastic sphere. International Journal Of Multiphase Flow. 2017, 90, 156–166. [Google Scholar]

- Turangan, C. , Ong, G., Klaseboer, E. & Khoo, B. Experimental and numerical study of transient bubble-elastic membrane interaction. J. Appl. Phys. 2006, 100. [Google Scholar]

- Sagar, H. & Moctar, O. Dynamics of a cavitation bubble near a solid surface and the induced damage. J. Fluids And Structures 2020, 92, 102799. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z. , Wei, S., Wang, P., Qiu, W. & Zhang, G. Progress in applications of laser induced cavitation on surface processing. Optics & Laser Technology 2024, 170, 110212. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, T. Effect of ultrasonic frequency on mass transfer of acoustic cavitation bubble. Chemical Engineering Science 2024, 300, 120654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauterborn, W. & Mettin, R. Acoustic cavitation: Bubble dynamics in high-power ultrasonic fields. Power Ultrasonics 2023, 23–52. [Google Scholar]

- Philipp, A. & Lauterborn, W. Cavitation erosion by single laser-produced bubbles. J. Fluid Mech. 1998, 361, 75–116. [Google Scholar]

- Tomita, Y.; Shima, A. Mechanisms of impulsive pressure generation and damage pit formation by bubble collapse. J. Fluid Mech. 1986, 169, 535–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, M. Laser Cavitation Bubbles at Objects: Merging Numerical and Experimental Methods; University of Goettingen: Göttingen, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dular, M.; Požar, T.; Zevnik, J.; Petkovšek, R. High speed observation of damage created by a collapse of a single cavitation bubble. Wear 2019, 418–419, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A. , Li, S., Cui, P., Li, S. & Liu, Y. A unified theory for bubble dynamics. Phys. Fluids 2023, 35. [Google Scholar]

- Vogel, A.; Lauterborn, W. Acoustic transient generation by laser-produced cavitation bubbles near solid boundaries. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1988, 84, 719–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomita, Y.; Robinson, P.; Tong, R.; Blake, J. Growth and collapse of cavitation bubbles near a curved rigid boundary. J. Fluid Mech. 2002, 466, 259–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindau, O.; Lauterborn, W. Cinematographic observation of the collapse and rebound of a laser-produced cavitation bubble near a wall. J. Fluid Mech. 2003, 479, 327–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadivar, E.; Moctar, O.; Skoda, R.; Löschner, U. Experimental study of the control of cavitation-induced erosion created by collapse of single bubbles using a micro structured riblet. Wear 2021, 486–487, 204087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y. , Wang, Z. & Zou, L. Analytical investigation of the nonlinear dynamics of empty spherical multi-bubbles in hydrodynamic cavitation. Phys. Fluids 2020, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Alehossein, H. & Qin, Z. Numerical analysis of Rayleigh–Plesset equation for cavitating water jets. International Journal For Numerical Methods In Engineering 2007, 72, 780–807. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, K. , Zhao, D. & Zhang, L. Theoretical research on the motion of spherical bubbles with surface tension. Acta Mechanica Sinica 2023, 39, 322341. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, A. , Li, S., Xu, R., Pei, S., Li, S. & Liu, Y. A theoretical model for compressible bubble dynamics considering phase transition and migration. Journal Of Fluid Mechanics 2024, 999, A58. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S. , Phan, T., Nguyen, V., Duy, T., Nguyen, Q. & Park, W. Numerical simulation of wall shear stress and boundary layer flow from jetting cavitation bubble on unheated and heated surfaces. International Journal Of Heat And Mass Transfer 2024, 222, 125189. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, J. , Liu, Y., Wang, S., Zhang, S. & Tao, L. Numerical analysis of nonlinear interaction between a gas bubble and free surface in a viscous compressible liquid. Phys. Fluids 2023, 35. [Google Scholar]

- Lechner, C. , Lauterborn, W., Koch, M. & Mettin, R. Jet formation from bubbles near a solid boundary in a compressible liquid: Numerical study of distance dependence. Physical Review Fluids 2020, 5, 093604. [Google Scholar]

- Hlawitschka, M. , Kováts, P., Dönmez, B., Zähringer, K. & Bart, H. Bubble motion and reaction in different viscous liquids. Experimental And Computational Multiphase Flow. pp. 1-13, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, G.; Zhang, M.; Han, L.; Ma, X.; Huang, B. Physical investigation of acoustic waves induced by the oscillation and collapse of the single bubble. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021, 72, 105440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Wang, S.; Li, S.; Zhang, A.M. Numerical investigation of an underwater explosion bubble based on FVM and VOF. Applied Ocean Research 2018, 74, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, T.H.; Nguyen, V.T.; Park, W.G. Numerical study on strong nonlinear interactions between spark-generated underwater explosion bubbles and a free surface. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer 2020, 163, 120506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.M.; Liu, Y.L. Improved three-dimensional bubble dynamics model based on boundary element method. Journal of Computational Physics 2015, 294, 208–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedadi, M.; Choubey, A.; Nomura, K.; Kalia, R.; Nakano, A.; Vashishta, P.; Duin, A. Structure and dynamics of shock-induced nanobubble collapse in water. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 105, 014503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choubey, A.; Vedadi, M.; Nomura, K.; Kalia, R.; Nakano, A.; Vashishta, P. Poration of lipid bilayers by shock-induced nanobubble collapse. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2011, 98, 023701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santo, K.; Berkowitz, M. shock wave-induced collapse of arrays of nanobubbles located next to a lipid membrane: Coarse-Grained computer simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B 2015, 119, 8879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, U.; Goliaei, A.; Berkowitz, M. Mechanism of membrane poration by shock wave-induced nanobubble collapse: A molecular dynamics study. J. Phys. Chem. B 2015, 119, 6225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, S.; Duan, H.; Pan, L.; Tu, J.; Jia, D.; Yang, T.; Li, J. Molecular dynamics simulation of shock-induced microscopic bubble collapse. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2021, 23, 8446–8455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaee, S.; Kadivar, E.; el Moctar, O. The role of sawtooth-shaped nano riblets on nanobubble dynamics and collapse-induced erosion near solid boundary. Journal Of Molecular Liquids 2024, 405, 124947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, S.; Mitra, N. Atomistic insight into the shock-induced bubble collapse in water. Physics of Fluids 2023, 35, 097114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaee, S.; Kadivar, E.; el Moctar, O. Molecular dynamics simulations of a nanobubble’s collapse-induced erosion on nickel boundary and porous nickel foam boundary. Journal Of Molecular Liquids 2024, 397, 124029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D. , Zhang, X., Dong, R. & Wang, H. The impact of low-velocity shock waves on the dynamic behaviour characteristics of nanobubbles. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2024, 26, 11945–11957. [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto, M.; Miyamoto, K.; Ohguchi, K.; Kinjo, T. Molecular Dynamics Simulation of a Collapsing Bubble. Prog. Theor. Phys. Suppl. 2000, 138, 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C.; Heyes, D.; Powles, J. The Collapsing Bubble in a Liquid by Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Mol. Phys. 2002, 100, 3451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugli, F.; Höfinger, S.; Zerbetto, F. The Collapse of Nanobubbles in Water. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 8020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadivar, E.; Rajabpour, A.; el Moctar, O. Nanobubble Collapse Induced Erosion near Flexible and Rigid Boundaries: A Molecular Dynamics Study. Fluids 2023, 8, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikemoto, N.; Kinouchi, S.; Matsumoto, M. MD-CFD hybrid simulation of a nanobubble. In Proceedings of the ASME Heat Transfer Summer Conference, HT2007-32647, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–12 July 2007; pp. 71–76. [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto, M. Surface Tension and Stability of a Nanobubble in Water: Molecular Simulation. J. Fluid Sci. Technol. 2008, 3, 9220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekine, M.; Yasuoka, K.; Kinjo, T.; Matsumoto, M. Liquid-Vapor nucleation simulation of Lennard-Jones fluid by Molecular Dynamics Method. Fluid Dyn. Res. 2008, 40, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Fu, Q.; Kang, J. Cavitation and negative pressure: A flexible water model molecular dynamics simulation. Int. J. Stat. Probab. 2019, 8, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schanz, D.; Metten, B.; Kurz, T.; Lauterborn, W. Molecular dynamics simulations of cavitation bubble collapse and sonoluminescence. New J. Phys. 2012, 14, 113019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, K.; RKKalia,; A. ; Vashishta, P.; Duin, A. Mechanochemistry of shock-induced nanobubble collapse near silica in water. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2012, 101, 073108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekhar, A.; Nomura, K.; Kalia, R.; Nakano, A.; Vashishta, P. Nanobubble collapse on a silica surface in water: Billion-Atom reactive molecular dynamics simulations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2013, 111, 184503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Lin, X.; Zhang, Z.; Gu, N. Impact of shock-induced lipid nanobubble collapse on a phospholipid membrane. J. Phys. Chem. C 2016, 120, 18803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, N. , Si, D.; Hu, G. Nanoscale cavitation in perforation of cellular membrane by shock-wave induced nanobubble collapse. J. Chem. Phys. 2018, 149, 074902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becton, M.; Averett, R.; Wang, X. Effects of nanobubble collapse on cell membrane integrity. J. Micromech. Mol. Phys. 2017, 2, 1750008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Adnan, A. Effect of shock-induced cavitation bubble collapse on the damage in the simulated perineuronal Net of the Brain. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 5323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Choe, S.; Jong, U.; Pak, M.; Yu, C. The maximum interbubble distance in relation to the radius of spherical stable nanobubble in liquid water: A molecular dynamics study. Fluid Phase Equilibria 2019, 487, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Rajak, P.; Susarla, S.; Ajayan, P.; Kalia, R.; Nakano, A.; Vashishta, P. Molecular simulation of MoS2 exfoliation. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 16761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Zhang, L.; Joshi, R. Numerical evaluations of membrane poration by shockwave induced multiple nanobubble collapse in presence of electric fields for transport through cells. AIP Adv. 2019, 9, 045006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoohestani, M.; Rezaee, S.; Kadivar, E.; Esmaeilbeig, M. Reactive-dynamic characteristic of a nanobubble collapse near a solid boundary using molecular dynamic simulation. Phys. Fluids 2023, 35, 022003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Fan, Z.; Cai, L.; Fu, Y.; Liu, J.; Liu, Q.; Tong, Q.; Qiao, S.; Sun; A. Polyacrylamide structural instability and degradation induced by nanobubbles: A molecular simulation study. Phys. Fluids 2025, 37, 022024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, X.; Xu, W.; Guo, W.; Xiang, Q. Molecular Dynamics Simulation of Bubble Arrangement and Cavitation Number Influence on Collapse Characteristic. Fluid Dynamics & Materials Processing 2025, 21, 471–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Zhou, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, G.; Guo, W.; Zhao, F.; Wang, X. Multifactorial Analysis of the Collapse Process of Double Bubbles Based on the Coarse-Grained Force Field in Free Domain. Langmuir 2025, 41, 3706–3715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, C.; Shang, J.; Li; Z. Simulation of cavitation erosion damage and structural evolution caused by nano-bubbles for iron. Physics of Fluids 2024, 36, 042003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavi, S. Molecular simulations: Fundamentals and practice. (John Wiley & Sons,2020).

- Vergadou, N.; Theodorou, D.N. Molecular modeling investigations of sorption and diffusion of small molecules in glassy polymers. Membranes 2019, 9, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieve, D.C.; Russel, W.B. Simplified predictions of hamaker constants from lifshitz theory. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1988, 125, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stukowski, A. Visualization and analysis of atomistic simulation data with OVITO–the Open Visualization Tool. Modelling And Simulation In Materials Science And Engineering. 2009, 18, 015012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).