2. Materials and Methods

This chapter details the methodological structure of the assessment method we propose with this contribution, developed to evaluate empathic immersive storytelling in VR/AR learning environments through an application of a specific case study project. In line with the project’s objectives and current best practices in immersive experience assessment, we first explain how the key analytical dimensions were identified, then outline the design of a dual-path protocol combining subjective (conscious) and objective (unconscious) data collection methods. Each component is described with the level of granularity required to support reproducibility and potential adaptation in similar research contexts. In addition to the structure of the method itself, this chapter also reports on its application in two testing phases: a preliminary internal validation, aimed at proof-testing the coherence and usability of the designed tools, and the subsequent user study conducted with selected participants, from which evaluative data were collected and analyzed.

2.1. The EMOTIONAL Case Study Project

The methodological approach has been tested within the framework of EMOTIONAL project. The EMOTIONAL project is primarily aimed at training designers and entrepreneurs to develop a deeper understanding of sustainability through emotionally-driven immersive storytelling. As part of Italy’s National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), under the PE11 - MICS (Made in Italy Circolare e Sostenibile) program, the initiative (Experience Made in Italy: Immersive Storytelling Design for Contemporary Values and Sustainability) seeks to equip professionals with innovative communication and design tools that enhance the cultural and symbolic value of products and services. By placing immersive storytelling at the core of its methodology, the project encourages a shift in perspective: materials are no longer seen as inert, but as carriers of identity, history, and meaning. Through the narrative of production processes, particularly within the ceramic sector, participants learn the tangible and intangible values of a sustainable Made in Italy. The project promotes a hybrid approach where design, technology, and artistic expression converge to create emotionally engaging experiences. The work developed within the EMOTIONAL project reflects a vision of a sustainable Made in Italy that extends far beyond technical excellence. It in fact draws attention to a broader conception of sustainability, one that includes symbolic, emotional, and cultural dimensions. In this experience, concepts such as affective materiality, material storytelling, and animistic design come into play. Based on this vision, the project has focused on developing an immersive experience that center on the emotional and narrative potential of “things”. In the project’s video, it is the object itself that speaks in the first person: it recounts its journey from seemingly inert matter to animated form, from raw substance to a meaningful entity. In this transformation, the object acquires value not only as a product, but as a presence within the domestic space: it is no longer a silent absence, but a participant in the environment, ready for dialogue. This process appears to encourage the extension of the lifespan of objects that accompany daily life, yielding evident environmental benefits. Jane Bennett suggests that it is important to argue for the vitality of matter, as depicting matter as inherently inanimate may hinder the development of more ecologically sound and materially sustainable modes of production and consumption [

22]. Italy, in this regard, offers a particularly rich cultural heritage: the tale of Pinocchio, in which a piece of wood becomes a living child, metaphorically suggests that objects can come to life, an idea deeply embedded in the Italian design tradition. As [

32] notes, in fact, Italian design has historically contributed a distinct humanistic sensibility to the European design landscape, an ability to endow objects with a soul, an autonomous life that transcends mere functionalism. Italian design has been shown to foster complex, symbolic relationships between users and objects, resembling the bonds typically associated with domesticated animals, whose presence in living spaces is often shaped more by emotional tradition than by practical necessity. This animistic tradition is not new; in fact, it is deeply rooted in the material culture of ancient Rome and Pompei, where furniture and household items often featured animal limbs, tails, and heads, gestures toward a perceived inner vitality. Such a worldview, largely absent in other design traditions, stems from the influence of Mediterranean religions with animistic and pantheistic beliefs, in which objects were thought to possess a soul and the world was imbued with divine presence. Finally, as [

33] reflects, when objects are invested with emotions, ideas, and symbols, by individuals, societies, and history, they become things in a philosophical sense. They transcend their status as mere commodities or markers of social status and enter a realm akin to art: objects are removed from their precarious position in space and time and are transformed into 'miniatures of eternity,' thereby acquiring a lasting symbolic significance. In this specific case study project, the ceramic object becomes the narrator of its own transformation, from raw matter to valued design artifact, offering new modes of communicating sustainability. By animating the material and allowing it to express its own becoming, the project has been designed both to cultivate an affective bond between object and user and to offer a deeper understanding of the artisanal processes’ characteristic of the Italian ceramic tradition. In doing so, it transforms everyday products into emotionally resonant presences and makes visible the complexity, care, and cultural heritage embedded in their making. This sense of affection and symbolic attachment contributes to a reconfiguration of the object’s perceived value and role within domestic life. As a result, the aim of the immersive storytelling is to encourage reflection on the value of objects, making them less likely to be discarded and more likely to be preserved, repaired, or repurposed, thus contributing to the extension of their life cycle, by promoting responsible innovation and fosters more conscious production and consumption practices, while reinforcing the distinctive identity of Made in Italy as not only a marker of quality and craftsmanship, but also as a bearer of cultural depth and environmental awareness.

2.2. Identification of Analytical Elements for Empathic Immersive Storytelling

Given the emergent nature of emotionally immersive storytelling, particularly in educational contexts, the development of a structured analytical framework to assess its effectiveness is essential. In alignment with the aims of the EMOTIONAL case study, a set of evaluative dimensions has been specifically identified to guide the validation of design outcomes, with the intention of supporting both replication and further development in related research. The framework is intended to capture indicators that reflect the impact of immersive experiences in fostering empathy, encouraging perspective-taking, and stimulating reflective engagement with socially and environmentally relevant themes. The dimensions, described below, were defined based on existing literature and contextual adaptation to immersive educational storytelling:

Embodied Knowledge: this dimension refers to the participant’s holistic experiential integration of the content, encompassing cognitive understanding, a felt sense of presence, and emotional resonance with the narrative in the learning process. It builds on the concept of the human being as a “biological embodiment” [

34], underscoring the importance of lived and sensory engagement.

Attitudinal Shift: this dimension assesses shifts in participants’ values or viewpoints in relation to the topics addressed in the narrative, especially regarding sustainability, cultural awareness, and ethical sensitivity. Drawing on communication theories [

35], the focus is on how immersive storytelling can act as a catalyst for behavioral intention, attitude transformation, or increased relevance attribution.

Semantic Differential: a semantic differential technique is employed to gather participants’ subjective assessments of key experiential elements, capturing the connotative meanings they associate with specific themes or symbols. This allows for the quantification of nuanced perceptual and emotional responses in a structured and comparative format.

Technological Usability and Physical Response: this dimension includes measurements of cybersickness symptoms and user acceptance of the immersive medium, considering that interactions with technology can evoke a range of affective responses, both positive and adverse, linked to users’ values, expectations, and comfort levels [

36].

Cognitive and Emotional Engagement: this evaluates the degree of mental focus and affective investment during the experience. Given the increasing challenges of capturing sustained attention in digital environments, this dimension helps determine the narrative’s capacity to maintain user interest and provoke intellectual or emotional activation [

37].

Together, these analytical dimensions offer a comprehensive foundation for assessing the design functionality of immersive narratives aimed at education, awareness-raising, and the stimulation of empathic reflection. The framework is intended not only as a tool for validation within this specific study but also as a contribution to the broader discourse on evaluating the pedagogical and transformative potentials of immersive media.

2.3. Conscious Responses

In alignment with the evaluative dimensions outlined in the previous chapter, we developed a Subjective Assessment framework informed by existing validated tools and adapted to the specific aims of the EMOTIONAL case study. The selection and design of these instruments were guided by two priorities: ensuring the relevance of each item to the dimensions under investigation, and maintaining a high level of participant engagement to promote response accuracy while minimizing cognitive fatigue.

To meet these criteria, the framework integrates methods drawn from state-of-the-art literature in affective computing, user experience evaluation, and immersive learning, combined and restructured with particular attention to clarity of administration and narrative continuity. In particular, to evaluate shifts in attitude and perception, several key items are presented both before and after the immersive experience, enabling direct comparison and detection of change over time.

2.3.1. Format and Delivery

To enhance usability and participant engagement, the questionnaire was delivered in the form of an analog deck of cards, from which respondents physically draw and answer one question at a time. This format introduces a light gamification element, which has been shown to increase motivation, perceived autonomy, and attention in self-report tasks [

38]. The physical format also ensures a clean and focused interface, allowing participants to concentrate on a single item at a time without the distraction of digital interfaces.

Four response formats were used throughout the assessment:

Verbally annotated 5-point Likert scales, ranging from 1 (“not at all”) to 5 (“extremely”)

Visual Self-Assessment Manikin (SAM) scales

Yes/No multiple choice questions

Sorting tasks, involving the ordering of nine items from 1 to 8 (with one item pre-labeled)

All questions were originally written in Italian, reflecting the cultural and linguistic context of the target population. For reporting and international dissemination, English translations are provided here with utmost attention to semantic fidelity. The development and review of the questionnaires were conducted in collaboration with Dr. Francesca Borgnis, psychologist and researcher with a PhD in the application of 360° video in neurorehabilitation, ensuring scientific rigor and methodological alignment.

2.3.2. Embodied Knowledge

Drawing on existing literature that highlights the potential of 360° video for facilitating experiential and procedural learning [

39] embodied knowledge was assessed through a dual approach: (1) self-evaluation of confidence in the domain of Made in Italy ceramic manufacturing, and (2) a recall task involving the sequential reordering of the nine stages presented in the video. These items were included in both pre- and post-questionnaires to enable comparative analysis. The confidence question was phrased as:

Pre: “How confident do you feel with the manufacture of Made in Italy ceramics?”

Post: “Now that you have lived this experience, how confident do you feel with the manufacture of Made in Italy ceramics?”

The reordering task was intended to test narrative coherence and procedural retention, as indicators of the story-living approach’s capacity to convey practical knowledge.

2.3.3. Attitudinal Shift

To assess attitudinal change in relation to object value and attachment, we employed two adapted items from a validated psychometric tool on object attachment [

40]. Both items explore the willingness to part with the protagonist object of the narrative (a ceramic lamp), from whose first-person perspective the story is experienced:

The distinction between gift and disposal enables us to detect nuances in affective disposition and symbolic attachment.

2.3.4. Semantic Differential

To investigate semantic shifts in the way participants interpret key concepts such as Made in Italy and ceramic craftsmanship, we employed a semantic differential method [

41,

42]. Before and after the experience, participants were asked to select three keywords from a list of ten in response to two prompts:

In the post-experience version, both questions were preceded by the prompt: “Now that you have lived this experience…” The keyword pool was internally categorized as either emotional or technological in tone (unbeknownst to participants), enabling us to observe any affective or cognitive reframing following the immersive exposure.

2.3.5. Cybersickness and Technological Acceptance

To monitor cybersickness, we combined a general familiarity question in the pre-test, “Have you ever used a headset for Virtual Reality?”, with three SAM-rated items in the post-test measuring discomfort, nausea, and headache. These items were selected after reviewing several established scales, including the Simulator Sickness Questionnaire (SSQ) [

43], MISC Scale [

44]. and more recent instruments like VRSQ [

45] and CSQ-VR [

46]. The reduced item set was selected to ensure brevity while preserving diagnostic validity, considering the non-interactive and low-motion nature of the content.

2.3.6. Technological Acceptance Was Assessed via a Single Item Derived from Models Such as TAM [47] and UTAUT [48]

This streamlined format was chosen to reduce cognitive load while capturing immediate user sentiment toward the technology.

2.3.7. Attention and Engagement

Attention and engagement were assessed through one item, adapted from the Suitability Evaluation Questionnaire [

49]:

This item was intended to provide a concise yet meaningful indicator of participants’ cognitive and emotional absorption during the experience, allowing its integration into a broader multi-dimensional evaluation framework.

2.3.8. Data Extraction

To allow for meaningful comparison across participants, responses from the subjective assessment were transformed into numeric scores: pre-existing experience of HMDs for VR, answered with yes/no, was turned into 1/0 and used to compute the percentage of subjects with past experience; technology acceptance was calculated by subtracting the average of the three 5-point Likert-scale questions on cybersickness symptoms from the self-reported pleasantness of the experience, also rated on a 5-point Likert scale. This difference captures net acceptance, isolating positive appraisal from physical discomfort. Attention and engagement were directly derived from a single 5-point Likert scale item. Embodied learning was computed as the difference between post-experience and pre-experience self-reported knowledge, both measured on a 5-point Likert scale, reflecting perceived learning gain. Error count in the post-experience sorting task was inversely related to content retention, with lower scores indicating better recall. The semantic differential score was calculated as the difference between pre- and post-experience scores of the theme’s emotional connotation. Finally, attitude shift was quantified as the difference between a positive attitude score and a negative attitude score, both measured using 5-point Likert scale items.

2.4. Electrodermal Activity for Unconscious Responses

Electrodermal Activity (EDA) is a widely used psychophysiological measure that reflects changes in the electrical properties of the skin due to sweat gland activity, which is directly influenced by the sympathetic branch of the autonomic nervous system. These changes are interpreted as indicators of emotional arousal and cognitive engagement which offer precious insights about Quality of Experience even acknowledging this type of data does not offer information about the positive or negative valence of the emotional activation. EDA is typically decomposed into tonic components, representing baseline arousal, and phasic components, which reflect short-term responses to stimuli [

50]. This makes EDA particularly suitable for evaluating moment-by-moment engagement during 360-degree VR learning experiences, where immersive content can elicit varying levels of attentional and emotional responses across different narrative phases. Its non-intrusive and continuous nature allows researchers to track fluctuations in user involvement in real-time, complementing self-reports and behavioral measures [

51].

2.4.1. Equipment and Setup

Analog Devices EVAL-AD5940BIOZ evaluation board was predisposed to acquire EDA data. It is important to note that it measures electrical skin resistance, implying that lower signal values indicate higher arousal, as increased sympathetic nervous system activation reduces skin resistance by increasing sweat gland activity. The device was connected to an ASUS ZenBook Pro 15 laptop. The board was integrated with SensorPal, the official data acquisition software provided by Analog Devices, which enabled real-time signal visualization and export. The data were output as raw numerical datasheets in .csv format for subsequent analysis. To ensure accurate signal acquisition, we used disposable Ag/AgCl electrodes, which were applied to the palmar surface of the index and middle fingers, following the standard four-electrode measurement configuration. This electrode placement is commonly adopted in psychophysiological research due to its stability and signal fidelity. The electrodes were applied immediately after participants completed the onboarding questionnaire and before wearing the VR headset.

2.4.2. Signal Processing and Feature Extraction

To minimize participant burden and avoid priming or influencing emotional states prior to the session, no baseline recording was collected before the experience. As a result, inter-subjective differences in resting skin resistance were expected, and the analysis pipeline was designed accordingly to accommodate this variability. All EDA data were therefore normalized post hoc, enabling meaningful intra- and inter-subjective comparisons of both tonic and phasic arousal trends throughout the experience. The raw electrodermal activity (EDA) signal was collected at a temporal resolution of 250 ms (i.e., four samples per second) and exported as an Excel file. To reduce signal noise and enhance interpretability, the EDA data were smoothed by computing the average value per second, resulting in a down sampled but cleaner dataset that allowed for relevant information to emerge more clearly on the background of noise. The 12 minutes immersive VR experience was divided into 14 distinct phases, whose starting and ending time coordinates were useful to calculate, for each participant, the phase-by-phase mean slope of the smoothed EDA signal, providing an indicator of what events were able to trigger tonic change in physiological arousal. To enable meaningful comparisons across participants, the slope values were normalized to account for inter-individual variability: each subject's slope values were transformed into z-scores, using their own mean and standard deviation across the 14 phases:

where x is the slope of a given phase, μ is the subject's mean slope across all phases, and σ is the corresponding standard deviation. To classify slope magnitudes into discrete categories, binning was applied using Scott’s rule [

52] First, the full set of normalized slope values (26 subjects × 14 phases = 364 data points) was collected. The minimum, maximum and standard deviation of the dataset were computed. The optimal bin width h was calculated using Scott’s formula:

where σ is the standard deviation and n the number of observations. The number of bins was then calculated by dividing the data range by h:

Next, the bin thresholds were computed iteratively using the formula:

This produced a set of equally spaced intervals covering the range of normalized slope values. Finally, the resulting bins were grouped into five ordinal tiers centered around the mean (z = 0), corresponding to the labels: -2, -1, 0, +1, and +2. Returning to the slope analysis, for interpretability purposes, we inverted the valence of the tier scale when mapping slope z-scores into categorical levels. Since in our signal configuration lower slopes reflect greater arousal, we assigned the lowest slope values to the highest tier (+2), indicating intense engagement or emotional activation, while higher slopes (indicating low arousal or disengagement) were assigned to lower tiers (e.g., -2). This allowed for consistency in interpreting both phasic and tonic EDA dynamics, aligning the direction of the metrics with arousal magnitude across the dataset. In parallel, phasic EDA activations ("spikes") were extracted by first converting the smoothed EDA signal to z-scores, computed within each subject. This normalization step allowed us to identify punctual, subject-relative deviations in EDA that could reflect moments of heightened emotional reactivity. A detection threshold was then applied to identify significant downward deflections in the z-score, consistent with our setup in which EDA was recorded via skin resistance, meaning that lower values indicated higher arousal. Following the rationale of nonnegative convolution, we adapted this to a nonpositive detection model, setting thresholds for negative deviations in the z-score. In a small number of cases, this threshold set to z<-3, was manually adjusted to account for inter-subjective variability in baseline reactivity, ensuring meaningful spike detection without excessive false positives or omissions. To avoid counting physiologically redundant activations, spikes occurring within 1.5 seconds of one another were merged and treated as a single response event.

2.5. Rough Experiment Structure

The assessment process was carefully designed to capture user responses both before and after the immersive experience, enabling a direct comparison between baseline attitudes and post-exposure perceptions. The assessment unfolds across five main phases:

Onboarding, in this phase, participants are welcomed. They are informed about the following phases and are asked to provide written consent for photographic documentation and preference about biometric measurement.

Pre-experience questionnaire subjective discrete annotation, designed to explore participants’ prior knowledge and attitudes toward the content addressed in the immersive narrative, as well as their familiarity with immersive technologies such as HMDs.

Immersive experience objective continuous annotation, during which no verbal interaction is required, allowing for uninterrupted affective and cognitive engagement with the 360° video.

Post-experience questionnaire subjective discrete annotation, aimed at capturing changes in perception, emotional resonance, cognitive engagement, and physiological comfort, as well as subjective evaluation of the technology used.

Offboarding, after the immersive experience and the questionnaires, participants are finally thanked for their involvement and dismissed.

2.6. Sampling Design

A key component in testing the effectiveness of the proposed assessment framework was the purposeful and methodologically grounded selection of participants. Given the nature of the study, focused on immersive VR/AR learning experiences, it was essential not only to secure an adequate sample size to ensure statistical robustness, but also to account for factors that could influence how users perceive and respond to the immersive content. The selection strategy was guided by international standards, specifically the ITU-T P.919 (10/2020) Recommendations: Subjective test methodologies for 360º video on head-mounted displays, which indicate that a minimum of 28 participants is required to achieve sufficient statistical power for perceptual studies involving immersive media. Although the current study was conceived as a pilot, our objective extended beyond technical validation: we aimed to generate rich, interpretable insights into users’ subjective and physiological responses to the content, anticipating a range of individual factors, such as cultural familiarity or prior exposure to immersive environments, that might shape perception and engagement. To this end, we adopted a purposeful sampling strategy [

53] selecting a total of 60 participants and organizing them into four homogeneous subgroups of 15 participants each, based on shared sociodemographic and experiential characteristics. This structure follows a similarity logic, which aims to reduce within-group variability, a factor shown to significantly increase the statistical power of experimental designs [

54]. The composition of the subgroups was carefully controlled to enable more focused, internally consistent observations, while also allowing for comparative analysis across the broader sample. In parallel, for the objective component of the assessment, centered on biometric and physiological indicators such as Electrodermal Activity, we conducted data collection with a subset of 26 participants. This decision was informed by recent evidence on statistical power analysis in psychophysiological research, which indicates that a sample size of 26 is sufficient to detect medium effects with a statistical power of 0.8 [

55]. This level of power is generally accepted as the standard threshold in experimental research, balancing practical feasibility with the need for reliable inference. By aligning our sampling design with established methodological frameworks and statistical criteria, we sought to ensure that both subjective and objective components of our assessment could yield meaningful, generalizable findings. The integration of purposeful selection with power-driven sampling for biometric analysis positions the framework as both empirically robust and sensitive to the complexities of human experience in immersive educational environments.

2.7. First Internal Validation

Following the definition of the assessment framework in its theoretical and structural aspects, a preliminary internal validation was conducted to identify potential areas for refinement and to gain practical familiarity with the full implementation of the protocol prior to testing with external participants. This initial trial also served to evaluate the overall usability of the procedure and the effectiveness of the designed tools in guiding participants through the three phases of the assessment. The internal sample consisted of five individuals, three faculty members and two research associates, who each completed the full testing sequence. This allowed for a preliminary appraisal of the framework’s internal consistency and its operational feasibility from both the participant and facilitator perspectives. The validation sessions took place at the Virtual Theater of the EDME Laboratory at Politecnico di Milano, an acoustically isolated environment specifically designed for immersive media experiences. The setting complies with recommendations from the ITU-T P.919 (10/2020) guidelines, ensuring minimal environmental interference during content delivery and data acquisition. While initial results confirmed the general validity of the framework and its potential to capture the targeted analytical dimensions, several practical issues were identified that informed adjustments for the subsequent pilot test. Notably, the use of a swivel chair, although recommended for immersive viewing, proved incompatible with EDA data collection due to cable constraints. As a result, biometric recordings were conducted using a stationary chair to ensure signal stability. Additional considerations emerged concerning the usability of the HMD. Participants unfamiliar with VR interfaces found the process of initiating video playback unintuitive. To address this, the moderator assumed responsibility for launching the video via the headset joystick, followed by verbal confirmation with the participant. Battery limitations of the Oculus device also required attention during scheduling: each full video playback consumed approximately 10% of the battery, imposing logistical constraints for extended testing sessions. Logistical challenges were also observed in relation to the physical administration of the analog card-based questionnaire. Although this format supported user engagement and clarity, it introduced potential risks of card misplacement or mixing. To mitigate this, each participant received a pre-bundled deck secured with elastic bands, and after completion, responses were manually transcribed into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. This internal validation phase also proved valuable in defining a standardized structure for the .csv file and establishing a consistent procedure for data transcription, ensuring the resulting dataset would be ready for streamlined analysis. Based on the insights from this internal validation, it was estimated that each session, including onboarding, video experience, and data collection, required a 20-minute time slot per participant. This informed the planning and scheduling of the subsequent pilot testing phase, ensuring appropriate time management and process optimization.

2.8. Fine-Tuned Experiment Design

Following the pilot test, the insights gained allowed us to refine and formalize the experimental procedure into a standardized assessment method. This finalized version, presented below, is structured into clearly defined phases, each accompanied by a detailed breakdown of the required materials and operational steps to ensure replicability and consistency across future applications.

2.8.1. On Boarding

Analog Devices EVAL-AD5940BIOZ The onboarding phase marked the formal initiation of the participant's involvement in the assessment procedure. Upon arrival, participants were greeted individually and introduced to the context of the study in neutral and non-directive terms. To avoid priming effects, no specific details about the content of the video or the purpose of the research were disclosed beyond what was necessary for informed participation. Participants were then provided with a form asking for photo release consent, outlining the possibility of being photographed during the session for documentation purposes and requesting formal authorization and EDA participation consent, describing the nature and purpose of the biometric monitoring (Electrodermal Activity) and allowing participants to opt in or decline based on comfort or health considerations. Following consent collection, participants were informed of the sequence of the assessment: the pre-experience questionnaire, the immersive video, the post-experience questionnaire, and final offboarding. Those who opted for EDA measurement were prepared for electrode placement immediately after completing the pre-questionnaire. This phase was designed to establish an environment of procedural transparency and ensure ethical compliance.

Materials: Photo release and EDA consent forms

2.8.2. Pre Experience Questionnaire

(Subjective Discrete Annotation) The second phase of the assessment consists of a structured pre-experience questionnaire, aimed at collecting baseline data on participants’ prior knowledge, attitudes, and familiarity with immersive technologies, specifically head-mounted displays (HMDs). This step is essential for establishing reference points against which post-experience changes could be measured. Participants complete the questionnaire individually, using analog decks of printed cards presented in a bundled format. All responses are manually collected and later transcribed into a structured .csv format for analysis. The pre-experience questionnaire serves not only as a diagnostic tool but also as a gentle cognitive warm-up before participants enter the immersive environment.

Materials: Analog questionnaire decks, printed and bundled with elastic bands to maintain card order; Pens for participant responses; Transcription of all analog responses into Microsoft Excel and export as a structured .csv file.

2.8.3. Immersive Experience

(Objective Continuous Annotation) The third phase involves the delivery of the immersive storytelling experience through a 360° video viewed using a head-mounted display (HMD). This stage is designed to allow uninterrupted affective and cognitive engagement, with no verbal interaction or tasks required from participants during the experience, which risk interfering with immersion and involvement. EDA measurement of compliant participants ensures a continuous annotation that allows for the detection of unconscious, real-time changes in emotional arousal and attentional engagement throughout the narrative experience. To ensure consistency and replicability across all sessions, the following standardized procedure was designed for the immersive experience phase:

Preparation of the Environment: The testing area is divided into semi-private stations using the mentioned sliding curtains, ensuring participant focus and minimizing external distractions. Each station is equipped with one head-mounted display (HMD) and either a stationary or swivel chair, depending on whether biometric data collection was planned.

Application of Electrodes (for EDA group only): For participants who consent to EDA measurement, disposable Ag/AgCl electrodes are applied to the palm surface of both hands following a standard four-electrode configuration.

Wearing and Adjustment of the HMD: The assigned HMD (Oculus Quest 3 or Pico 4) is placed and adjusted for each participant by the moderator to ensure optimal comfort and visibility.

Launching of the 360° Video: The moderator initiates video playback using the joystick/controller to avoid potential usability issues for participants unfamiliar with the interface of the device.

Confirmation of Successful Playback: A short verbal confirmation is given to the participant (e.g., “Can you confirm the video has started and you see the first scene clearly?”)

Start of EDA Measurement (if applicable): EDA data acquisition begins immediately following the confirmation of successful video launch. Measurement continues throughout the entire duration of the video, with real-time monitoring via SensorPal and RealTerm.

Participant Notification of Video Completion: Upon conclusion of the video, the participant is instructed to signal the moderator (e.g., by raising a hand), indicating that the experience had ended.

Termination of EDA Recording: Biometric data acquisition is stopped by the moderator, and the recorded session saved in .csv format for analysis.

Removal of HMD: The headset is carefully removed and put into charge until the next turn.

Removal of Electrodes (if applicable): Electrodes are gently detached and properly discarded and the participant is thanked for their cooperation.

This phase is critical for capturing both embodied emotional responses and sustained attentional engagement, key indicators in assessing the immersive and empathic potential of the narrative.

Materials for Environmental setup: Stationary chairs (used during EDA recording to avoid motion artifacts); Swivel chairs (used with Pico 4 for enhanced immersion in non-biometric sessions); Sliding curtain system to create semi-private interaction areas within the Virtual Theater

Material for Immersive media delivery: Oculus Meta Quest 3 head-mounted display; Pico 4 head-mounted display; Official joysticks/controllers for each HMD; HMD chargers and power cables, used between sessions to ensure battery continuity

Material for Biometric sensing: Disposable Ag/AgCl electrodes for skin contact; Analog Devices EVAL-AD5940BIOZ evaluation board; ASUS ZenBook Pro 15 laptop (Windows 11); SensorPal for signal acquisition; RealTerm v2.0.0.70 for real-time graph visualization and data logging (.csv output)

2.8.4. Post Experience Questionnaire

(Subjective Discrete Annotation) In the fourth phase of the assessment protocol, participants complete the post-experience questionnaire, designed to capture conscious reflections and perceived changes following the immersive narrative. This phase allows for direct comparison with baseline data collected during the pre-experience phase and focuses on evaluating shifts in knowledge, attitude, emotional resonance, and perceived technological comfort. administered in the form of analog cards. Participants respond individually, using pens to annotate their answers directly on the cards. Each set of cards is pre-bundled to prevent misordering and facilitate transcription. Upon completion, all responses are manually digitized into a structured .csv file for subsequent analysis. This phase is critical for contextualizing biometric data and exploring how participants assign meaning to the immersive experience. It is supposed to reveal whether and how the narrative succeeds in fostering perspective shifts, emotional engagement, and learning outcomes.

Materials: Analog questionnaire decks, printed and bundled with elastic bands to maintain card order; Pens for participant responses; Transcription of all analog responses into Microsoft Excel and export as a structured .csv file

2.8.5. Offboarding

Analog The offboarding phase concludes the assessment protocol. Once participants have completed the post-experience questionnaire, they are thanked for their time and participation and informed that the testing session is complete. At this point, any remaining materials (e.g., pens, card decks) are collected, and participants are formally dismissed from the session.

2.9. Pilot-Test Sessions

Testing at Politecnico di Milano, within the Virtual Theater of the EDME Laboratory, and at the Made in Italy Innovation Forum hosted at Villa Erba in Cernobbio, a national event dedicated to circular and sustainable innovation, promoted by the MICS extended partnership. All testing environments were carefully selected to support immersion and reduce external interference. The Virtual Theater at Politecnico offers full acoustic isolation and is specifically designed for immersive media experimentation, in accordance with ITU-T P.919 recommendations, while the Cernobbio session was held in a dedicated exhibition space within the Villa Erba complex.

Participants took part on a voluntary basis and were divided into four homogeneous groups, following a similarity-based logic to reduce within-group variability:

Undergraduate students enrolled in the Bachelor’s Program in Product Design;

Graduate students enrolled in the Master’s Program in Product Design;

Graduate students from the Master’s Program in Interaction Design;

Entrepreneurs and business leaders from the Made in Italy sector, who were attending the Innovation Forum.

Participants were informed in advance that the activity would involve viewing a 360° video using a head-mounted display (HMD) and responding to written multiple-choice and sorting questions. However, in order to prevent priming or expectancy effects, no specific information was given regarding the content of the video or the goals of the study. They were also informed that biometric data would be collected during the session via disposable electrodes placed on the hand to measure Electrodermal Activity (EDA). Participation in this aspect of the test was optional and could be declined for any reason, including health concerns or personal preference. A total of 26 participants across all sessions chose to take part in the EDA measurement, which was conducted only using the Oculus Meta Quest 3; these individuals were seated on stationary chairs to avoid cabling related issues. Participants using the Pico 4 HMD, employed as a second device for parallel sessions, were instead seated on swivel chairs to maximize immersion, as recommended by ITU-T guidelines. Each of the three university-based sessions lasted approximately 2 hours and 20 minutes and was managed by two moderators operating in parallel. Each moderator was responsible for one HMD station, and for the sessions that took place in EDME Laboratory, thanks to a specifically designated space, the testing area was divided by a sliding curtain to provide a private and distraction-free setting for each participant, fostering immersion. In that context, participants were also assured that only their assigned moderator and, in some cases, a psychologist (for observational purposes) would be present during the experience.

Participants across all groups were generally receptive to the procedure. Their responses to the HMDs ranged from enthusiastic engagement to neutral curiosity, and all subjects displayed calm, collaborative behavior throughout the process, allowing for smooth facilitation and data collection.

3. Results

This chapter presents an analysis of participants' responses to the educational narrative-based 360° video VR experience, combining physiological data, subjective assessments, and cross-group comparisons to explore how users engaged with the content at cognitive, emotional, and attentional levels. In this context, an important premise is that the analysis of electrodermal activity (EDA) in this study does not aim to produce definitive or objective accounts of participants’ emotional states, but rather to offer a set of grounded physiological cues that may suggest how different moments of a 360 video VR learning experience were embodied by its viewers, in fact, given the intrinsically variable and context-dependent nature of EDA signals, influenced by individual differences in physiology, baseline arousal, and subtle environmental factors, alongside the calm, non-turbulent character of the video itself, the resulting data should not be read as a direct translation of inner affective states: instead, it provides a textured substrate from which to derive interpretive insights, revealing possible moments of heightened attention, subtle engagement, or arousal. We are going to integrate self-reported and biometric indicators to identify recurring patterns of engagement, learning, and meaning making. In the first place we will illustrate the data collected through the Subjective Assessment, to get a first insight of how the experience was overall received; then we are going to examine group intersections, exploring how different experiential traits, such as engagement, embodied learning, technology acceptance, and physiological reactivity, tend to co-occur or diverge across participants; finally, a phase-by-phase analysis of electrodermal activity identifies moments within the video that elicited consistent peaks in physiological arousal, offering clues about the narrative structure’s effectiveness in sustaining attention and emotional activation.

To enable meaningful performance comparisons across parameters with different underlying scales and calculation logics, all scores were normalized to a common 0-10 range. Parameters included direct ratings on a 5 points Likert scale as well as computed differences between pre- and post-experience measures, or between individual values and multi-item means. For consistency, scores based on Likert ratings were normalized using min-max scaling on the [

1,

5] interval and multiplying the result by 10, while difference-based metrics, whose theoretical range spans from -4 to +4, were normalized on the [-4, +4] range and then multiplied by 10 as well.

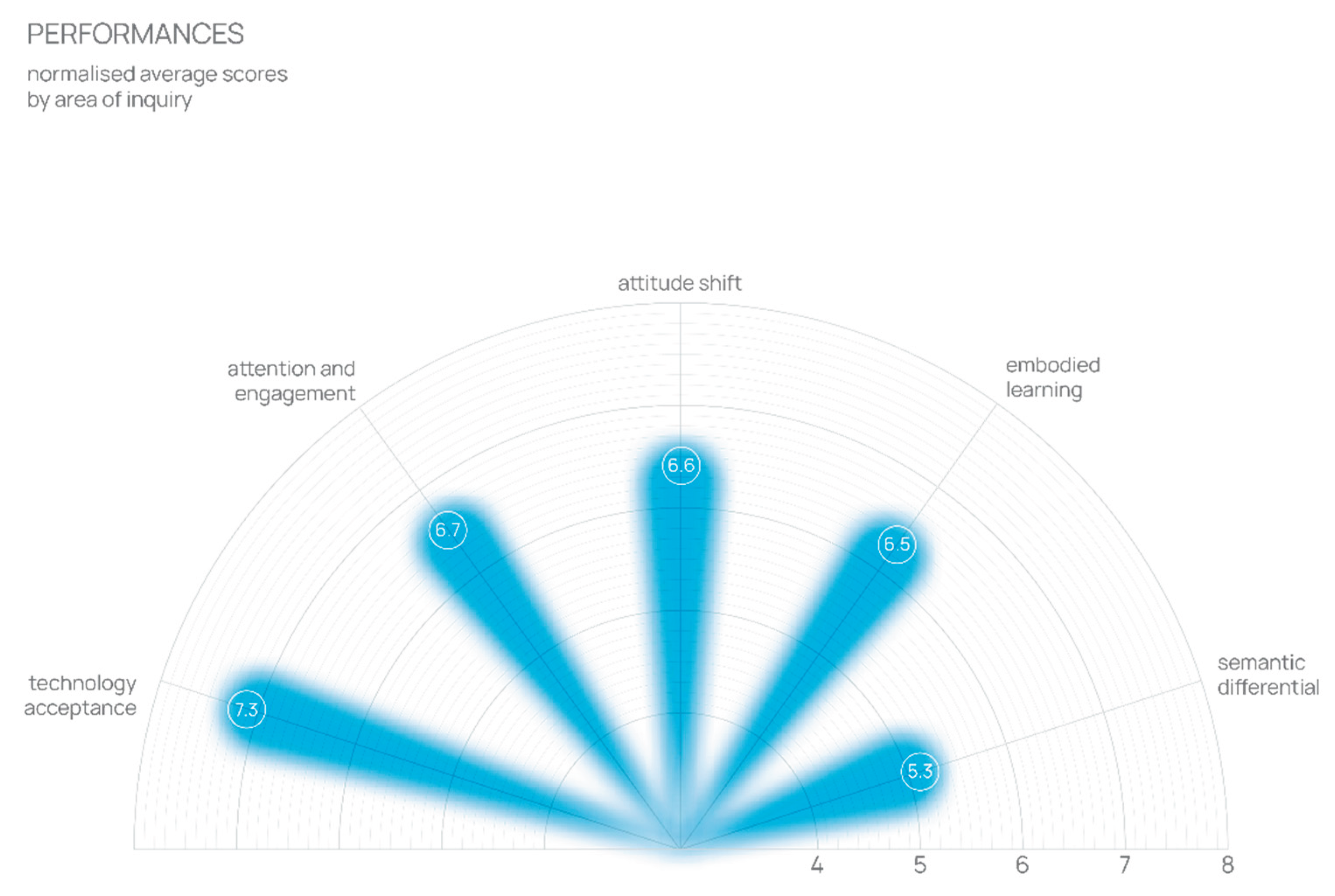

Overall, the data suggests that the content was well received. As visible in

Figure 1, among the total sample of 60 participants, 34 SC (Swivel Chair, no EDA) and 26 EDA, participants reported moderately high engagement (normalized score = 6.7), alongside a positive shift in self-perceived knowledge (normalized score = 6.5) and a notable attitudinal change (normalized score = 6.6) in favor of the theme presented. The normalized average semantic differential score (= 5.3) indicates that, even if modestly, the video encouraged participants to reframe the topic with more emotionally connoted or nuanced meanings. Technology acceptance was moderately high (normalized score = 7.3), suggesting participants tolerated the technology well and generally enjoyed the experience, but did not overwhelmingly embrace it. On average, participants made 3.1 errors in the post-experience sorting task, providing a baseline indicator of how well factual content was retained or understood under the constraints of a narrative-driven, immersive learning format. Even if moderate, differences across participant backgrounds revealed further nuances. Bachelor’s students in product design reported the highest level of engagement (7.2) and technology acceptance (8) but showed average semantic shift (5.3) and slightly below average attitude change (6), possibly reflecting a more pragmatic, design-process-oriented framing of the content. In contrast, interaction design master’s students showed the highest attitudinal shift (7) and semantic reframing (5.7) despite slightly below average technology acceptance (7), suggesting a stronger emotional or reflective response. Product design master’s students reported relatively high engagement (3.7) and consistent learning gains (6.4) but also had the lowest technology acceptance score (6.8) and the highest error rate (3.9) in the sorting task, which may point to greater sensitivity to the medium’s limitations or challenges in extracting structured information from the narrative. Finally, entrepreneurs showed the greatest perceived knowledge gain (6.9) and semantic differential change (6), perhaps due to lower initial familiarity with the content and greater openness to personal or cultural interpretation. These variations point to the relevance of disciplinary context and prior experience in shaping how participants make sense of immersive content, not only in terms of usability or performance, but also in emotional and cognitive reframing.

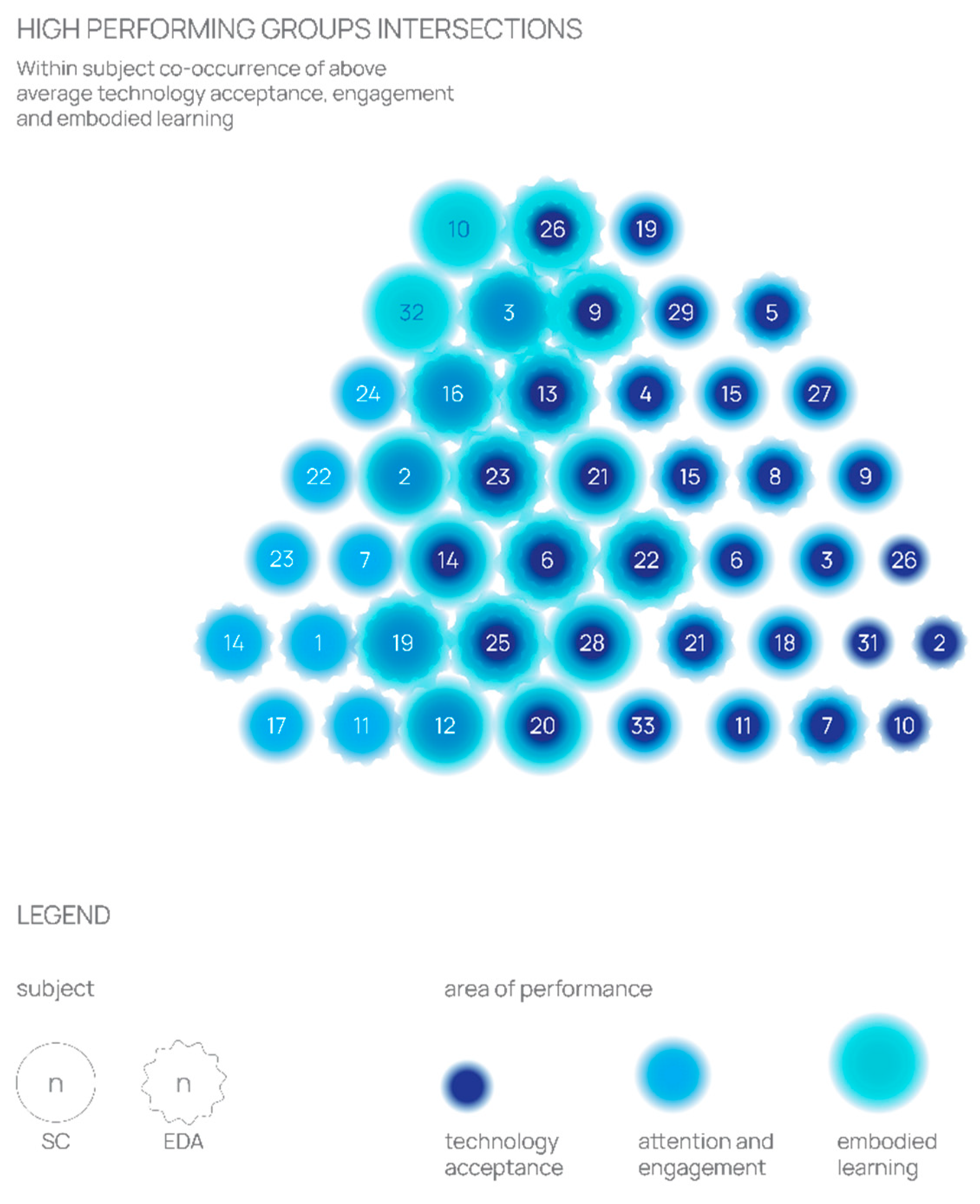

The intersection analysis of subject group memberships across the 60 participants revealed multiple recurrent patterns that shed light on engagement dynamics and experience interpretation during the VR learning session. Notably, a strong co-occurrence emerged between above average engagement and above average technology acceptance, with 25 subjects (EDA4, EDA5, EDA6, EDA7, EDA8, EDA13, EDA15, EDA21, EDA22, EDA23, EDA25, SC3, SC6, SC9, SC11, SC14, SC15, SC18, SC19, SC20, SC21, SC27, SC28, SC29, SC33) present in both groups, suggesting that engagement and acceptance may reinforce one another.

A significant triple intersection was observed across above average engagement, above average technology acceptance, and above average semantic differential, where 11 participants (EDA6, EDA7, EDA11, EDA13, EDA15, EDA25, SC11, SC15,SC21, SC27, SC28, SC33) not only demonstrated sustained attentional involvement and positive evaluations of the technological medium, but also demonstrated a semantic shift in how they interpreted the cultural content of the experience. This 18% subset of the population may represent the most holistically responsive users, suggesting that cognitive, affective, and usability-related satisfaction may be positively correlated.

As shown in

Figure 2, another notable intersection was observed between participants classified with above average engagement and above average embodied learning, encompassing 14 individuals (EDA3, EDA6, EDA13, EDA16, EDA19, EDA22, EDA23, EDA25, SC2, SC12, SC14, SC20, SC21, SC28), corresponding to 23% of the total sample. This overlap indicates a convergence between attentional focus and self-perceived cognitive assimilation. Within this subset, 9 participants (EDA6, EDA13, EDA22, EDA23, EDA25, SC14, SC20, SC21, SC28) also demonstrated above average technology acceptance, forming a distinct intersection across three key experiential dimensions, engagement, learning, and attitudinal openness to the medium. Representing approximately 15% of all subjects, this group may exemplify an optimal profile for immersive educational content, characterized by consistent receptivity across cognitive, affective, and technological parameters.

Patterns among below average groups also revealed meaningful insights. The intersection of below average engagement and below average technology acceptance included 16 subjects (EDA12, EDA17, EDA18, EDA20, EDA24, SC1, SC4, SC5, SC8, SC10, SC13, SC16, SC25, SC30, SC32, SC34), suggesting that disengagement was often accompanied by reduced affinity toward the VR system, possibly limiting the depth of learning. Similarly, below average engagement and below average embodied learning overlapped in 10 participants (EDA2, EDA10, EDA24, EDA26, SC4, SC5, SC8, SC10, SC25, SC26), highlight the critical role of engagement in supporting meaningful cognitive outcomes.

When examining how prior VR experience relates to user traits, participants encountering HMD VR for the first time were represented across both high and low-performing groups, suggesting no univocal trend. However, a subset of first-time users, such as EDA6, EDA15, and EDA25, stood out for their presence in multiple above average groups, including engagement, technology acceptance, and embodied learning. Interestingly, first-time users reported higher pleasantness scores on average (4 out of 5 vs. 3 out of 5), which may have positively biased their classification into the above average technology acceptance group. This raises the possibility that, for novice users, initial affective excitement may temporarily elevate perceived acceptance, even if their cognitive or embodied engagement is less developed. Conversely, experienced users, while showing comparable resilience to cybersickness, may have rated the experience more critically, perhaps due to higher expectations or diminished novelty effects. Still, several experienced users, most notably EDA13, EDA22, and EDA23, appeared across nearly all positive trait clusters, combining high engagement, technology acceptance, and embodied learning with stable physiological indicators (e.g., least oscillating slopes and no spikes). This suggests that sustained positive outcomes may depend less on novelty and more on an integrated response profile, where prior familiarity supports more stable attentional and affective involvement. Taken together, these intersections do not point to definitive profiles but rather highlight emerging patterns that may inform future inquiry. Engagement in immersive learning may take multiple forms, ranging from emotionally reactive to sustained and focused, and its relationship with other traits appears to be complex and context dependent.

When considering physiological responses, it has been observed that positive mean slope trends by phase, indicative of increasing arousal throughout the experience, were present in only a few participants (9, 21, 25), yet these individuals consistently aligned with other positive traits, including high engagement, high embodied learning, or high technology acceptance. This suggests that a gradual build-up of emotional activation may characterize the most holistically engaged users.

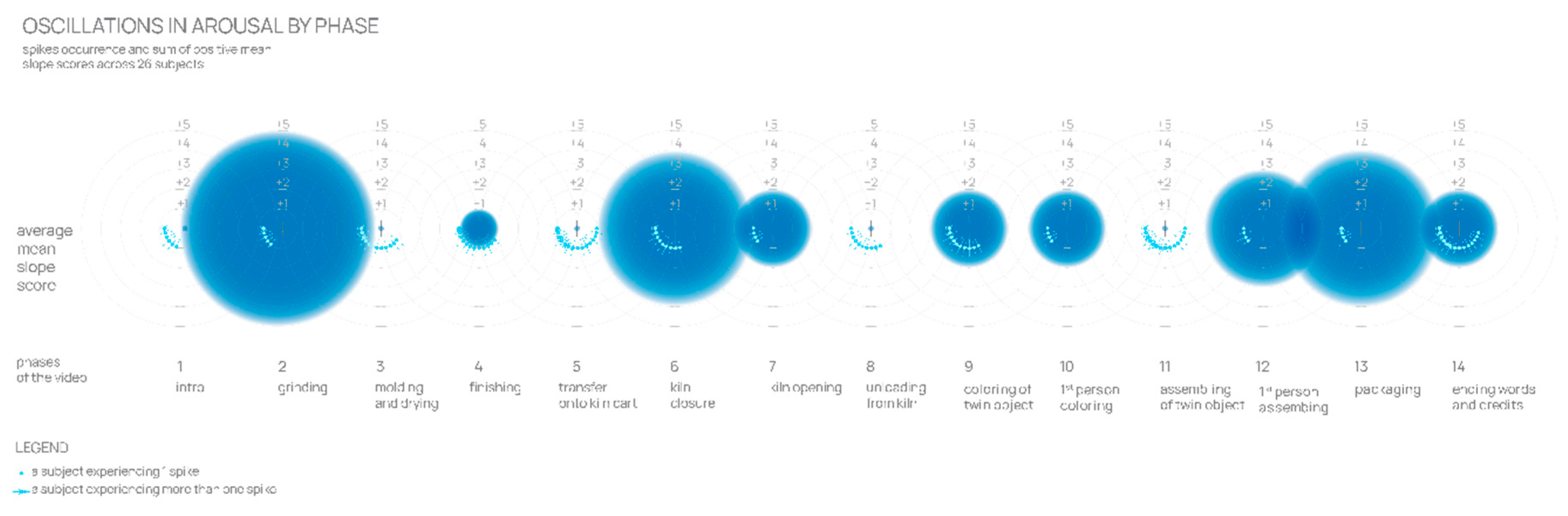

Finally, the continuous analysis of electrodermal activity (EDA) across the video experience allowed us to identify specific phases associated with heightened physiological activation, providing data-driven insights into which segments were most engaging for participants. This approach enabled a phase-by-phase mapping of arousal without interrupting the experience or relying on retrospective self-reports, which are often subject to memory bias and limited temporal resolution. Specifically – as observable in

Figure 3 - the phases most frequently associated with positive slope trends across subjects, indicating a sustained increase in sympathetic activation, were the 2nd phase, 6th phase, 12th phase, and 13th phase.

These moments may represent key points of increased attention or emotional resonance, suggesting that the temporal progression of the narrative induced gradual shifts in engagement. In parallel, the highest number of EDA spikes, reflecting brief but intense changes in arousal, were observed in the 14th phase (30 spikes across 14 subjects), 11th phase (29 spikes across 15 subjects), and 5th phase (23 spikes across 15 subjects). These results highlight discrete moments of heightened physiological response, which can be interpreted as peaks of immediate attentional or emotional reaction shared across multiple subjects. Continuous physiological monitoring allowed us to capture both gradual trends and sudden shifts in engagement throughout the video without introducing response fatigue or disrupting the experience with in-situ questioning. This method offers a reliable and non-invasive way to evaluate narrative structure and pacing and can inform the design of future immersive educational or experiential content by identifying which segments consistently elicit user activation.

Taken together, the findings suggest that the immersive learning experience was moderately effective in fostering a multidimensional form of engagement, combining attentional focus, emotional resonance, and moderate cognitive gains. High engagement, embodied learning, and technology acceptance co-occurred among certain participants suggesting such experiential aspects could be positively correlated in a virtuous cycle, unveiling the potential of immersive narratives, however, the data also highlights the variability of user responses, dependent on the subjective and situated nature of the experience.

4. Discussion

This study set out to explore the potential of low-threshold immersive technologies -specifically 360° video with 3 degrees of freedom (3DoF)- to generate emotionally engaging, cognitively effective learning experiences in the context of sustainability education. Grounded in the hypothesis that narrative-driven immersion could stimulate both embodied knowledge and attitudinal reflection, even in the absence of full interactivity, the project aimed to validate a hybrid evaluation framework capable of capturing these multidimensional outcomes through a combination of subjective and objective metrics. The preliminary findings of the EMOTIONAL project confirm that immersive storytelling, even when delivered through so-called “low-intensity” media like 3DoF 360° video, can be effective in promoting embodied learning, emotional resonance, and value-oriented engagement. While such formats are often considered limited in comparison to full-scale VR environments with six degrees of freedom (6DoF), these technical constraints do not necessarily reduce educational or affective impact. In the EMOTIONAL project, communicative efficacy was enhanced through a first-person narrative delivered by the object itself, transforming inert matter into an expressive protagonist. This approach, rooted in emotional design and material storytelling, appears to foster empathy and identification, amplifying users’ affective and cognitive immersion. Moreover, the restriction of physical movement inherent to 3DoF may function as a cognitive advantage: by reducing navigational complexity, users can direct more attentional resources to the emotional and semantic dimensions of the experience. These findings are consistent with prior research demonstrating that narrative coherence and emotional salience can compensate for limited interactivity in immersive experiences. Similarly, the role of emotional design in promoting memory retention and behavioral intention aligns with theoretical models and extended immersive storytelling design. The integration of narrative design and immersive media thus emerges as an effective lever for transformative learning. The hybrid evaluation framework employed in this study -merging self-report instruments with biometric measures (Electrodermal Activity) -enabled a layered analysis of user engagement that captured both conscious reflection and unconscious arousal. EDA analysis revealed patterns of physiological reactivity that closely mirrored participants’ self-reported levels of attention, engagement, and narrative impact. Interestingly, users with prior VR experience tended to demonstrate superior performance in procedural learning tasks (e.g., recall of manufacturing stages), suggesting that familiarity with the medium may free cognitive resources for content assimilation. In contrast, first-time users reported higher emotional resonance and showed more significant semantic reframing, confirming a novelty effect that enhanced emotional receptivity. Nevertheless, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, this is an exploratory study with a relatively small and culturally homogeneous sample (N=60), composed primarily of students and professionals in the fields of design and Italian craftsmanship. While this focus facilitated methodological control and initial protocol validation, it limits the generalizability of findings to broader or international populations. Moreover, the disciplinary background of participants may have predisposed them to be more receptive to the narrative, visual, and emotional dimensions of the immersive experience, introducing potential affinity or motivation bias. This needs to be carefully addressed in future studies by involving participants from diverse fields and demographic profiles. Additionally, the experimental sessions were conducted in highly controlled environments (immersive labs and innovation events), which, while methodologically rigorous, do not reflect the conditions under which such content might be accessed at scale -e.g., in schools, museums, public exhibitions, or domestic contexts. The replicability of the observed effects in less structured environments remains to be tested. For these reasons, future research should expand testing to more diverse, cross-cultural samples varying in age, education, and digital literacy, in order to assess the framework’s robustness across learning domains and sociocultural settings. Longitudinal studies are also essential to evaluate whether short-term attitudinal shifts translate into durable behavioral changes, especially in domains such as environmental awareness, sustainable consumption, and material culture appreciation. In conclusion, while the framework presented in this study is preliminary and requires further validation across diverse contexts and populations, it is not only a post-hoc tool for evaluation but a strategic design support mechanism, capable of guiding content creation. In a time marked by interconnected ecological, social, and cultural crises, immersive technologies -when grounded in systemic, participatory, and emotionally resonant design- can offer powerful platforms for value transmission, critical reflection, and sustainable behavioral change.