1. Introduction

Cancer is a disease characterized by the loss of control over the mechanisms of cell division, leading to variations in its etiology and pathogenesis depending on the individual patient. It is the second leading cause of death worldwide [

1,

2]. According to data from the World Health Organization, cancer is responsible for 9.6 million deaths annually, accounting for 1 in 6 deaths [

3]. Various factors, including lifestyle, diet, smoking, alcohol consumption, genetic predisposition, and exposure to harmful chemicals, can contribute to the development of cancer [

4,

5].

Gastrointestinal cancer, includes the gastric cancer, colon cancer and colorectal cancer types that typically develops sporadically and has a heterogeneous structure, is among the most common cancers both globally and in Türkiye, with a low survival rate [

6]. The pathogenesis of these cancers involves the accumulation of multiple genetic and epigenetic abnormalities in cells, which can lead to the progression from benign polyps to more advanced malignant polyps, eventually resulting in locally invasive cancers and metastatic disease [

7]. Factors such as the formation of stepwise mutations, either spontaneously or through inheritance, mutations or hypermethylation in DNA repair genes, disruption in the expression of genes associated with tumor formation or cell cycle control, and chromosomal instabilities caused by breakage and rearrangement during chromosome replication are considered underlying causes [

8,

9]. Recent studies in the literature also suggest that microorganisms in the tumor environment have been significantly associated with various diseases, may also play a role in occurrence of intestinal cancers [

10,

11,

12]. It is hypothesized that certain bacterial products, such as toxins, secondary bile acids, and reactive oxygen species produced by microorganisms, may have potential procarcinogen roles. In studies involving colorectal cancer patients, fecal and biopsy samples have revealed the presence of various microorganism species, including

Clostridium septicum,

Enterococcus faecalis, Streptococcus bovis, Bacteroides fragilis, Helicobacter pylori, and Fusobacterium spp. Additionally, the genotoxic

Escherichia coli strain, which produces the genotoxin colibactin and causes DNA damage, has been identified [

13,

14,

15].

Escherichia coli cyclomodulins (CMs) toxins producing strains which in turn interfere with the eukaryotic cell cycle of host cells, suggest a possible link between these bacteria and carcinogenesis. There are relatively limited data available concerning the colonization of colon tumors by cyclomodulin and genotoxin producing

E. coli. The

E. coli isolates can be placed into eight phylogroups i.e., A, B1, B2, C, D, E, F and Cryptic clade I [

16]. Phylogroups analysis from previous studies suggested that many pathogenic E. coli strains are mainly distributed across all phylogroups, but are mainly associated with A, B2 and D phylogroups [

17]. Members belonging to B2 phylogroup are more virulent and virulence potential has been attributed to presence of several virulent genes and siderophores/iron chelating/colibactin molecules [

18,

19]. Colibactin is a small genotoxin molecule and secondary metabolite synthesized by a hybrid non-ribosomal peptide synthetase-polyketide synthase (NRPS-PKS) complex encoded within the pks genomic island of

E. coli. Colibactin (not yet been isolated and purified) located on pks island found in the

Enterobacteriaceae family, especially in coli B2 phylogroup [

20,

21,

22]. Its synthesis and activation require complex machinery i.e., three non-ribosomal peptide mega synthases (NRPS), three polyketide megasynthases (PKS), two NRPS/PKS hybrids and about eight of nine accessory enzymes encoded in the pks island [

23]. Colibactin induces reactive oxygen species (ROS) formation, double-strand DNA breaks, and the associated Ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM)-mediated DNA damage response, cell cycle arrest and genomic instability [

24] and such colibactin-producing

E. coli (~21% of humans harbor colibactin producing

E. coli in their intestinal microbiota) can enhance tumor, damage the DNA of eukaryotic cells inducing double strand breaks and disrupting the cell cycle and thus contribute to the disease pathology, especially colon cancer [

25].

Moreover,

Helicobacter pylori is the leading global cause of gastric disorders and, if left undiagnosed, might drive the development of gastric cancer.

H. pylori infection occurs asymptomatically in most cases. This is the reason why it should be examined carefully including the detailed analysis of its virulence factors that are ureA, ureB, dupA, hpaA, napA, cagA, vacA. These genes determine whether

H.pylori is pathogenic or not. The main duties of these genes are providing a living environment for the bacteria to keep themselves away from the acidic condition of the stomach, adhesion to the surrounding epithelial cells and triggering inflammatory factors of the host which cause chronic inflammation [

26,

27,

28].

Gastrointestinal cancers, have high mortality and morbidity rates in Türkiye. Despite this pathogen prevalence, patient profile for colibactin producing E. coli and H. Pylori together has never been established before for constructing a colon and gastric cancer patient. The present study aimed to identify the prevalence of E. coli and H. pylori in gastrointestinal cancers (colon cancer and gastric cancer), as well as virulence factors incidence of these pathogens (clbA, clbB, clbN, clbQ for E. coli and ureA, ureB, dupA, hpaA, napA, cagA, vacA (s1/s2) for H. pylori).

2. Results

2.1. Analysis of Colibactin Genes for Colon Cancer Patients

Colibactin presences were checked in both colon tumor tissues and bacteria obtained from single colony culture. DNA extracted from tumor specimens and bacteria were put into processing of PCR to evaluate the possibility of determining clb genes directly from tumor tissues without needing single colony culturing step.

2.1.1. PCR Results of the Colon Tissue Specimens

We first checked the presence of

clbA, clbB, clbN and

clbQ genes via conventional PCR. 19 colon tumor tissues were used in PCR and 5 healthy colon tissue specimens were used as a control. Moreover, 7 tissue specimens that were obtained from healthy sites of the colon of the colon cancer patients were also included in PCR for internal control. 3 cancer patients were found as

clbA positive, 3 of them found as clbB positive, 4 of them were clbN positive and 2 of them were

clbQ positive (

Table 1). All of the health control samples were discovered as clb negative. However, some of the tissue specimens obtained from healthy site of the colon of cancer patients demonstrated positivity for clb genes.

ClbA gene was detected in only 2 tumor tissue samples (CC1 and CC19) and 1 internal control tissue obtained from healthy site of the colon of colon cancer patient (KN1). All tissue samples obtained from healthy individuals were negative

clbA gene. Gel electrophoresis results were reported in

Supplementary File Figure S1.

ClbB was found positive in three colon cancer patients (CC1, CC10 and CC19) and 2 tissue samples obtained from healthy site of the colon resulted in positive for clbB gene (KN1 and KN10). Healthy individual’s results were all negative for

clbB. (

Supplementary File S1 Figure S2). Four cancer patients were discovered as

clbN positive (CC1, CC2, CC10 and CC19) and two tissues obtained from healthy sites of cancer patients showed positive results for

clbN gene. All healthy individuals indicated negative result for

clbN virulence (

Supplementary File S2, Figure S3).

ClbQ gene was found in 2 tumor tissues (CC10 and CC19). This gene was not detected in tissues obtained from healthy sites of colon cancer patients and healthy control tissues (

Supplementary File S1, Figure S4).

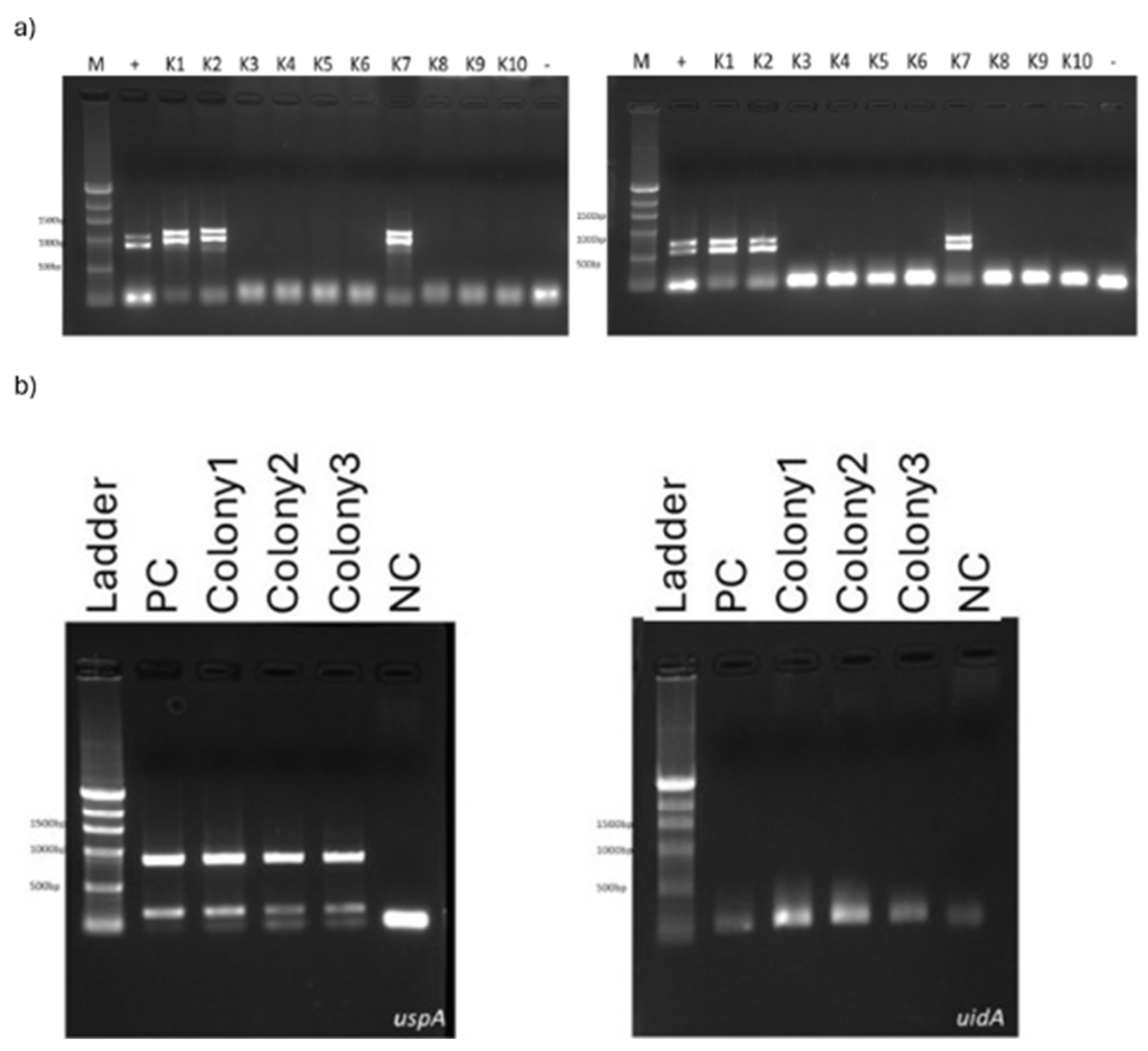

2.1.2. Colibactin PCR Analysis for Single Colony Culture

Tumor tissues that indicate positivity for clb genes (CC1, CC10 and CC19) were cultured to obtain single colonies. The reason behind obtaining single colonies is to observe the clb+

E. coli and prepare them for whole genome sequencing to identify the strain. DNA was extracted from ten bacteria colonies which grew in culture and PCR performed for these bacterial DNAs to observe

uspA, uidA, clbA, clbB, clbN and

clbQ genes. Among 10 colonies, 3 of them found to be positive for all clb genes (K1, K2 and K7) (

Figure 1a). Another PCR procedure was set for

uspA and

uidA detection for colony 1, colony 2 and colony 7. Each of them was also found positive for these two genes which prove that these colonies obtained from tumor tissues belonging to colon cancer patients are colibactin producing

E. coli (

Figure 1b).

2.1.3. Whole Genome Analysis

Single colonies that are obtained from CC1 and CC19 colon cancer patients (found positive in each clb genes because of PCR) were prepared for whole genome sequencing for the identification of

E. coli strain specifically. The reads generated from sequencing were assembled by using MHAP algorithm with 274.958.712 read depth. As a result of genome assembly 65 contigs and 4 scaffold were achieved. Reached biggest genome size was 4.846.766bp, the number of genes found in the biggest scaffold was 3247 and the number of genes found in whole contigs was 4868. Identification of the bacteria strain was carried out by blasting and “

Escherichia coli Nissle” was determined with 99.66% similarity (

Supplementary File S2). However, none of the clb genes were discovered in the whole genome. We observed the csg gene family (

csgA, csgB, csgC, csgF and csgG), fimD and fimA, ag43, luxS and bolA genes (

Table 2).

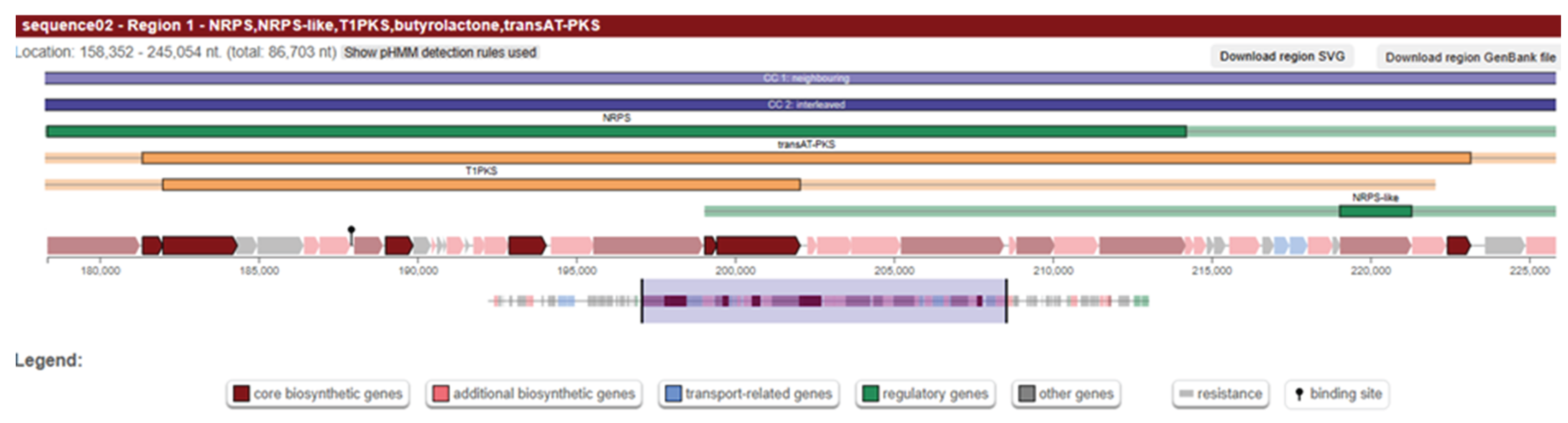

We further investigated the genome to find information about the presence of clb genes that we observed in PCR. We extracted the hypothetical proteins from genbank file and created another fasta file that only contains the hypothetical ones. Secondary metabolite prediction was performed using antiSMASH tool and we observed the presence of PKS island with high similarity confidence (

Figure 2). Then, we blast the region to determine the genes, and the hits obtained from ncbi blast result demonstrated the presence of clbI, clbB, clbC, clbG and clbO genes (

Supplementary File S3).

Other colony samples belonging to CC19 colon cancer patients were prepared for whole genome sequencing. The reads were generated from sequencing were assembled by using MHAP algorithm with 239.708.175 read depth; 20 contigs and 10 scaffold were obtained. Reached genome size reached 4.659.934bp, the biggest scaffold which contains 962 genes was 1.014.089 bp and the number of genes obtained from all contigs was 4306. The bacteria were identified as “

Citrobacter braakii” with 99% similarity by using blast (

Supplementary File S2). The significant genes obtained from the whole genome of the bacteria

were vexA, vexB, vexC, tviB, tviE, fimA, fimI, fimC, fimH, csgA, csgE and

csgG (

Table 3). We also excluded the hypothetical proteins to track the clb genes and performed the genome mining for secondary metabolite biosynthetic gene clusters using antiSMASH. No pks island were identified for Citrobacter braaki genome (

Supplementary File S3). The only hits observed from this analysis were non-ribosomal peptide metallophore (NRP) clusters.

2.2. Analysis of H. Pylori Virulence Factors for Gastric Cancer Patients

15 tissue samples were collected during the endoscopy procedure. 4 gastric cancer patients enrolled to our study, four tissue specimens obtained from the first patient and one of the specimens were taken from normal tissue in corpus region (GN1-Corpus), another specimen was taken from normal tissue in antrum region, one tumor tissue (GN1-Antrum), one specimen was taken from tumor tissue in antrum region (GC1-Antrum) and last tumor specimen belongs to the first patient was taken from corpus region (GC1-Corpus). Other cancer patients provided only one tumor tissue (GC2, GC3 and GC4). Other health controls were reported as GH (Gastric Healthy). PCR was performed to detect the prevalence of the virulence factors (

ureA, ureB, dupA, hpaA, napA, cagA, and

vacA (s1s2)) of the

Helicobacter pylori for each sample. Gel electrophoresis results were shown in

Supplementary File S4. None of the health controls demonstrated positivity for the

H. pylori virulence but only the third, healthy control, resulted as positive for each virulent gene that we have evaluated (

Table 4). On the other hand, all the four samples obtained from the gastric cancer patients contain at least one of the virulence genes except the fourth cancer patient sample was observed to be negative for each virulence. Among the seven virulence factors,

hpaA and

napA are the most observed ones compared to the others.

3. Discussion

Gastrointestinal cancer is one of the most observed cancer types in Türkiye and it contains gastric cancer colon cancer and colorectal cancer. There are plenty of pathways influencing the progression or occurrence of cancer. Helicobacter pylori and colibactin producing E. coli are one of the most virulent taxa that causes the gastric cancer and colon cancer respectively [

34,

35,

36]. In this study, we aimed to observe the profile of

H. Pylori virulence genes and its prevalence among gastric cancer patients and

E. coli clb genes on colon cancer patients’ profiles.

Four gastric cancer patients and nine healthy individuals enrolled in our study to investigate the

H.

pylori. Because of the exclusion of the patients that underwent antibiotic treatment and the budget of the research we couldn’t manage to reach desired sample size. In one of the health controls, all the virulent genes of the

H. Pylori demonstrated positivity. This is a plausible result because most of the individuals do not notice the

H. Pylori infections [

37,

38]. This taxon is able to grow in a silent way without causing any symptoms in the patient. What surprised us was the result of the fourth gastric cancer patient because its PCR results were negative for all virulence. Despite the fact that we have small sample sizes in our cohort, our evidence underlines the significance of

H. Pylori presence in the progression of gastric cancer. Even asymptomatic individuals may be infected with Helicobacter pylori strains carrying potent virulence factors that contribute to gastric carcinogenesis. However, other parameters should also be considered, as one of the gastric cancer patients in our study was

H. pylori negative, highlighting the potential importance of alternative biomarkers and pathways in the development of gastric cancer.

The study conducted on tissue samples from 19 colon cancer patients, the presence of the genotoxic E. coli strain containing the pks island was detected in 4 patients, with positivity in at least one of the clb genes (

clbA, clbB, clbN, clbQ). Of these, 3 patients tested positive for all four genes. No positivity was observed in the control group consisting of healthy colon tissue samples. Knowing the fact that tumor progression alters the microbiota in tissues, it is important to determine which bacteria specie contributes to the tumor growth. One of the most important candidates was genotoxin producing

E.coli strains. We applied single colony whole genome sequencing to identify if genotoxin producing E.coli strains present or not. Two colonies were cultured from two tumour specimens that belong to two different colon cancer patients and whole genome sequencing was applied to single colonies. As a result of whole genome sequencing,

Eschericihia coli Nissle and

Citrobacter braaki species were detected.

E. coli Nissle belongs to

Enterobacteriaceae family is a non-pathogenic bacterium which is generally being used as probiotics. However, this bacteria species contains the pks island which includes the clb genes. This bacterium is commonly seen in colon cancer patients but the impact of the colibactin producing activity has been studied rarely [

39,

40,

41,

42]. Colibactin toxins secreted from clb genes provide tumor formation or accelerate the tumor growth by causing double strand breaks in host DNA. In our whole genome dataset, we have not observed the clb genes directly, however further analysis on the data displayed the presence of the pks island in the genome of

E. coli Nissle. This evidence shows that presence of this bacterium should be considered seriously for the diagnosis of colon or colorectal cancer patients even if it is commonly classified as non-pathogenic.

The second whole genome was discovered to be

Citrobacter braaki that belongs to Enterobacteriaceae family is determined from the second colony. In the genome of this bacterium, we have not seen any colibactin genes and no pks island were observed. It only contains some virulence factors that belong to

vex,

fim and

csg gene clusters which are generally responsible for the biofilm formation [

43]. We did not expect to observe this taxon however this kind of situations are likely to occur because the bacteria that we wanted to see (colibactin producing strain of an

E. coli) and

Citrobacter braaki belong to the same family. This means that they are most likely to grow in the selective medium [

44]. Although the abundance of

Citrobacter braakii in colorectal tumor tissue is generally low compared to well-known CRC-associated bacteria such as

Fusobacterium nucleatum or pks-positive

Escherichia coli [

45,

46], its presence remains noteworthy. The detection of other secondary metabolite biosynthetic clusters, including an NRP metallophore and a terpene precursor cluster, suggests potential alternative metabolic or ecological adaptations. Given that

C. braakii is an opportunistic pathogen [

47], further in-depth analyses are warranted to elucidate its possible role and the underlying mechanisms contributing to its presence in the colorectal tumor microenvironment.

All in all, the prevalence of the E. coli that belongs to the B2 phylogroup was discovered to be quite rare in our study cohort. It means that other potential taxa like Bacteroides fragilis or Fusobacterium nucleatum are most likely to contribute the progression the colon cancer in Turkish populations. In addition to that, the prevalence of Escherichia coli Nissle and the opportunistic bacteria Citrobacter braaki should be taken into consideration in further studies. It is difficult to make a comment on the gastric cancer based on our small sample size, but it still helped us to give valuable outputs. The presence of Helicobacter pylori strains harboring severe virulence factors is not uncommon among asymptomatic individuals. However, as H. pylori represents an important risk factor, it should not be considered the sole biomarker for gastric cancer development, as additional host and environment related parameters also contribute to disease progression. In our data, we identified one healthy control who was H. pylori positive and carried all major virulence genes, whereas one of the gastric cancer patients was H. pylori negative, further highlighting the multifactorial nature of gastric carcinogenesis.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Sample Collection and Patient Cohort

31 tissue samples were collected from 19 colon cancer patients, 5 healthy individuals and remaining 7 samples were taken from the normal tissue of the cancer patients. 12 female and 12 male volunteers were accepted to be involved in this study, and ages of the individuals were ranging from 42 to 87 (mean = 61.03, SD=±14.58). 15 gastric tissue sample were collected and 4 of them were obtained from the gastric cancer patients, 8 healthy individuals and one patient provided 4 tissue specimens, one from normal tissue in antrum region, one from the tumor tissue in antrum region, one from normal tissue in corpus region and one from tumor tissue in corpus region. 8 female and 4 male volunteers were enrolled in the study and their age was ranging from 28 to 87 (mean=59.7, SD =±15.5 ). Individuals that have similar diet and lifestyle were selected and those using antibiotics and/or gastric acid inhibitors during the last 15 days were excluded from the study. Two specimens were taken for everyone, one tissue specimen was collected in RNAlater solution (GenemarkBio, Taiwan) for keeping the sample properly to be used in RNA and DNA extraction procedures. The other one was collected in sterilized Brucella broth for the analyzing of virulence factors which belong to Helicobacter pylori and Escherichia coli.

4.2. Sample Preparation

Brucella broth was prepared for the colleciton of tumor tissue sample. It was prepared by dissolving 14g brucella broth in 500ml of ddH₂O. In addition to that sterilized steel beads (diameter of 1.5mm) were added into the tubes that contain tha brucella broth because of the further homogenization steps. Columbia agar was prepared for growing H. pylori which was obtained from gastric tumour tissue. 42,5g columbia agar was dissolved in 50ml horse blood, 10ml β-cyclodextrin, 5ml 200X antibiotic mixture and 1ml 1000X antibiotic mixture. 200X antibiotic mixture contains 100mg of vancomycin, 50mg of cefsulodin, 3.3mg of polymixin B and they all dissolved in 50ml of ddH₂O. 1000X antibiotic mixture was prepared by dissolving 100mg of trimethoprim and 160mg amphotericin B in 20ml of DMSO.

4.2.1. Single Colony Streaking from Tissue Specimens

Collection tubes that contain tumor tissue in brucella broth were placed to Beadbeater (Biospec, US). Homogenized samples were cultured on Eosin Methylene Blue agar to provide a growth of E. coli bacteria. Cultured plates were incubated at 37°C overnight. Tumor tissues obtained from gastric cancer patients were cultured on Columbia agar and incubated at 37°C overnight. Columbia agar was put into anaerobic tubes and tubes were filled with microaerophilic gas mixture by using gas filling system (Don Whitley Scientific). After incubation, single colony samples were stocked and kept at -80°C.

4.2.2. DNA/RNA Isolation from Tissue Specimens, Swab Samples and Bacterial Culture

Quick-DNA/RNA Miniprep Plus kit (Xymo Research, Orange, CA) was used for DNA/RNA isolation from tissue specimens. Bacteria Genomic DNA Purification kit (GenemarkBio, Taiwan) was used for the isolation of swab samples and bacteria obtained from culturing. Extraction steps were performed based on kit instructions. NanoDrop™ 2000/2000c Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific) was used for determining the concentration of isolated DNAs and RNAs.

4.3. Virulence Gene Screening for Cancer Patients

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technique was used for the evaluation of gene expression analysis performed for colon tumor tissue specimens. Four colibactin genes which are

clbA, clbB, clbN and

clbQ were analyzed in our study. PCR was applied for both tumor and healthy control tissues to understand the virulence presence in healthy individuals and cancer patients. Primers were designed to

clbA, clbB, clbN and

clbQ genes (

Table 5). Mulitplex PCR mixture was consist of 4µl from 5X Hot Start PCR Master Mix, 1µl from forward primer, 1µl from reverse primer, 3µl from DNA and 11µl from dH₂O. PCR program included an initial denaturation step at 95°C for 4 minutes followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 30 seconds, primer annealing at 55°C for

clbA and

clbQ genes, 59°C for

clbB and

clbN genes for 40 seconds and primer extension at 72°C for 1 minute and with final extension step at 72°C for 5 minutes. All PCR products were visualized by using gel electrophoresis technique.

In gastric control and cancer tissues, primers specific for the H. pylori virulence genes ureA, ureB, dupA, hpaA, napA, cagA, and vacA s1/s2 were analyzed using conventional PCR. DNA from a reference H. pylori strain was used as positive control. Conventional PCR was performed using 5X Hot Start PCR Master Mix (GenemarkBio, Taiwan). The PCR reaction mixture consisted of 4 μl of 5X Hot Start PCR Master Mix (GenemarkBio, Taiwan), 1 μl of forward primer, 1 μl of reverse primer, 3 μl of DNA template, and 11 μl of dH₂O. The amplification conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 95°C for 3 minutes, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 45 seconds, annealing at 60°C for 45 seconds, and extension at 72°C for 2 minutes, with a final extension at 72°C for 5 minutes, and a hold at 4°C indefinitely.

5. Conclusions

Our findings highlight the complex and multifactorial nature of gastrointestinal cancers in the Turkish population. Although the prevalence of Escherichia coli strains from the B2 phylogroup was low, the detection of colibactin-producing Escherichia coli Nissle and the unexpected presence of Citrobacter braakii an opportunistic pathogen with biofilm-associated virulence factors emphasizes the need to broaden the scope of microbial investigations in colorectal cancer. Similarly, while Helicobacter pylori remain a critical risk factor for gastric cancer, the presence of virulent strains in asymptomatic individuals and the identification of an H. pylori negative gastric cancer patient underscore the importance of considering additional microbial, host, and environmental factors in gastric carcinogenesis. Larger, well powered studies integrating microbial profiling with host related parameters are warranted to better understand these interactions and their implications for cancer prevention, diagnosis, and management.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

T.K. and N.M. were equally contributed to the study. “Conceptualization, T.K., N.M.,S.O.O., O.U.S, and T.K.; methodology S.O.O., O.U.S, and T.K.; validation, T.K., N.M.. and S.O.O.; formal analysis, T.K., N.M.. and S.O.O.; investigation, T.K., N.M.. and S.O.O.; resources, A.T., S.Y., C.A., N.T.; data curation T.K., N.M.. and S.O.O.; writing—original draft preparation, T.K., N.M.. and S.O.O.; writing—review and editing, T.K., N.M.,S.O.O., O.U.S, and T.K.; visualization, T.K., N.M.. and S.O.O.; supervision, S.O.O.; project administration, N.T., T.K. and O.U.S.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research was funded by Technological Research Council of Türkiye (TÜBİTAK) with the Project no: 216S998.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by Acibadem Mehmet Ali Aydınlar Universitesi Tıbbi Araştırmalar Değerlendirme Kurulu (ATADEK) ethics committee.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support provided by the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Türkiye (TÜBİTAK), which made this research (Project no: 216S998) possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| clb |

Colibactin |

| SD |

Standart Deviation |

| WGS |

Whole Genome Sequencing |

| PCR |

Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| CC |

Colon Cancer |

| K |

Colony |

| GN |

Gastric Normal |

| GC |

Gastric Cancer |

| GH |

Gastric Healthy |

References

- Williams, G.H.; Stoeber, K. The Cell Cycle and Cancer. The Journal of Pathology 2012, 226, 352–364. [CrossRef]

- Glaviano A., Singh S.K., Lee E.H.C., Okina E., Lam H.Y., Carbone D., Reddy E.P., O’Connor M.J., Koff A., Singh G., Stebbing J., Sethi G., Crasta K.C., Diana P., Keyomarsi K., Yaffe M.B., Hunt K.K. Cell cycle dysregulation in cancer. Pharmacol. Rev. 2025, 77(2), 100030. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Cancer. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Byrne, S.; Boyle, T.; Ahmed, M.; Lee, S.H.; Benyamin, B.; Hyppönen, E. Lifestyle, Genetic Risk and Incidence of Cancer: A Prospective Cohort Study of 13 Cancer Types. International Journal of Epidemiology 2023, 52, 817–826. [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.; Afaq, F.; Mukhtar, H. Lifestyle as Risk Factor for Cancer: Evidence from Human Studies. Cancer Letters 2010, 293, 133–143. [CrossRef]

- Eser, S.; Örün, H.; Hamavioğlu, E.; Lofti, F. Cancer Incidence, Mortality and Survival in Türkiye as of 2020. bccr 2023. [CrossRef]

- Grady, W.M.; Carethers, J.M. Genomic and Epigenetic Instability in Colorectal Cancer Pathogenesis. Gastroenterology 2008, 135, 1079–1099. [CrossRef]

- Delgado J.M., Shepard L.W., Lamson S.W., Liu S.L., Shoemaker C.J.; The ER membrane protein complex restricts mitophagy by controlling BNIP3 turnover. Journal of Cellular Physiology 2024, 239(12), e31418. [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.-Y.; Ye, K. Risk Factors for the Prognosis of Colon Cancer. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2024, 16, 3738–3740. [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, N.; Kitano, S.; Puah, G.R.Y.; Kittelmann, S.; Hwang, I.Y.; Chang, M.W. Microbiome and Human Health: Current Understanding, Engineering, and Enabling Technologies. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 31–72. [CrossRef]

- Hou, K.; Wu, Z.-X.; Chen, X.-Y.; Wang, J.-Q.; Zhang, D.; Xiao, C.; Zhu, D.; Koya, J.B.; Wei, L.; Li, J.; et al. Microbiota in Health and Diseases. Sig Transduct Target Ther 2022, 7, 135. [CrossRef]

- Ogunrinola, G.A.; Oyewale, J.O.; Oshamika, O.O.; Olasehinde, G.I. The Human Microbiome and Its Impacts on Health. International Journal of Microbiology 2020, 2020, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Afzaal, M.; Saeed, F.; Shah, Y.A.; Hussain, M.; Rabail, R.; Socol, C.T.; Hassoun, A.; Pateiro, M.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Rusu, A.V.; et al. Human Gut Microbiota in Health and Disease: Unveiling the Relationship. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 999001. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lee, H.K. Potential Role of the Gut Microbiome In Colorectal Cancer Progression. Front. Immunol. 2022, 12, 807648. [CrossRef]

- Wong C.C., Yu J. Gut microbiota in colorectal cancer development and therapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 20(7), 429–452. [CrossRef]

- Rebersek, M. Gut Microbiome and Its Role in Colorectal Cancer. BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 1325. [CrossRef]

- Clermont, O.; Christenson, J.K.; Denamur, E.; Gordon, D.M. The Clermont Escherichia coli phylo-typing method revisited: Improvement of specificity and detection of new phylo-groups. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2013, 5 (1), 58–65. [CrossRef]

- Martin, P.; Tronnet, S.; Garcie, C.; Oswald, E. Interplay between Siderophores and Colibactin Genotoxin in Escherichia Coli. IUBMB Life 2017, 69, 435–441. [CrossRef]

- Royer, G.; Clermont, O.; Marin, J.; Condamine, B.; Dion, S.; Blanquart, F.; Galardini, M.; Denamur, E. Epistatic Interactions between the High Pathogenicity Island and Other Iron Uptake Systems Shape Escherichia Coli Extra-Intestinal Virulence. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 3667. [CrossRef]

- Faïs, T.; Delmas, J.; Barnich, N.; Bonnet, R.; Dalmasso, G. Colibactin: More Than a New Bacterial Toxin. Toxins 2018, 10, 151. [CrossRef]

- Lv, C.; Abdullah, M.; Su, C.-L.; Chen, W.; Zhou, N.; Cheng, Z.; Chen, Y.; Li, M.; Simpson, K.W.; Elsaadi, A.; et al. Genomic Characterization of Escherichia Coli with a Polyketide Synthase (Pks) Island Isolated from Ulcerative Colitis Patients. BMC Genomics 2025, 26, 19. [CrossRef]

- Suresh, A.; Ranjan, A.; Jadhav, S.; Hussain, A.; Shaik, S.; Alam, M.; Baddam, R.; Wieler, L.H.; Ahmed, N. Molecular Genetic and Functional Analysis of Pks-Harboring, Extra-Intestinal Pathogenic Escherichia Coli From India. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2631. [CrossRef]

- Balskus, E.P. Colibactin: Understanding an Elusive Gut Bacterial Genotoxin. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2015, 32, 1534–1540. [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, M.; Mestivier, D.; Sobhani, I. Contribution of Pks+ Escherichia Coli (E. Coli) to Colon Carcinogenesis. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1111. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Sun, D. The Synthesis of the Novel Escherichia Coli Toxin—Colibactin and Its Mechanisms of Tumorigenesis of Colorectal Cancer. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1501973. [CrossRef]

- Yamaoka, Y.; Graham, D.Y. Helicobacter pylori virulence and cancer pathogenesis. Helicobacter 2021, 26(S1), e12771. [CrossRef]

- Jones, K.R.; Whitmire, J.M.; Merrell, D.S. A Tale of Two Toxins: Helicobacter Pylori CagA and VacA Modulate Host Pathways That Impact Disease. Front. Microbio. 2010, 1. [CrossRef]

- Link A, Langner C, Schirrmeister W, Habendorf W, Weigt J, Venerito M, Tammer I, Schlüter D, Schlaermann P, Meyer TF, Wex T, Malfertheiner P. Helicobacter pylori vacA genotype is a predominant determinant of immune response to Helicobacter pylori CagA. World J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 23(26), 4712–4723. [CrossRef]

- Johnson JR, Johnston B, Kuskowski MA, Nougayrède J P, Oswald É. Molecular epidemiology and phylogenetic distribution of the Escherichia coli pks genomic island. J Clin Microbiol. 2008, 46(12), 3906–3911. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Griffiths, M.W. PCR differentiation of Escherichia coli from other Gram-negative bacteria using primers derived from the nucleotide sequences flanking the gene encoding the universal stress protein (uspA). Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 1998, 27 (6), 369–371. [CrossRef]

- Heijnen L., Medema G. Quantitative detection of Escherichia coli, E. coli O157, and other Shiga-toxin-producing E. coli in water using a combined culture and PCR method. J. Water Health 2006, 4(4), 487–498. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17176819/.

- Godambe S.L., Bhowmik A.K., Hossain M.A., et al. Molecular detection and phylogenetic characterization of Escherichia coli isolates from Indian street foods using uspA and uidA primer sets. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. Food Sci. 2017, 6 (Issue 1), 15–23. [CrossRef]

- Oktem Okullu, S.; Cekic Kipŗiţci, Z.; Kiliç, E.; Seymen, N.; Mansur Özen, N.; Sezerman, U.; Gurol, Y. Analysis of correlation between the seven important Helicobacter pylori virulence factors and drug resistance in patients with gastritis. Gastroenterology Research and Practice 2020, 2020, 3956838. [CrossRef]

- Akinduti, P.A.; Izevbigie, O.O.; Akinduti, O.A.; Enwose, E.O.; Amoo, E.O. Fecal Carriage of Colibactin-Encoding Escherichia Coli Associated With Colorectal Cancer Among a Student Populace. Open Forum Infectious Diseases 2024, 11, ofae106. [CrossRef]

- Tariq, H.; Noreen, Z.; Ahmad, A.; Khan, L.; Ali, M.; Malik, M.; Javed, A.; Rasheed, F.; Fatima, A.; Kocagoz, T.; et al. Colibactin Possessing E. Coli Isolates in Association with Colorectal Cancer and Their Genetic Diversity among Pakistani Population. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262662. [CrossRef]

- Yalçın, S. Gastric cancer in Turkey—a bridge between West and East: epidemiology, histopathology, and survival data. Gastrointest. Cancer Res. 2009, 3 (1), 29–32. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2661126/.

- Liou, J.-M.; Malfertheiner, P.; Lee, Y.-C.; Sheu, B.-S.; Sugano, K.; Cheng, H.-C.; Yeoh, K.-G.; Hsu, P.-I.; Goh, K.-L.; Mahachai, V.; et al. Screening and Eradication of Helicobacter Pylori for Gastric Cancer Prevention: The Taipei Global Consensus. Gut 2020, 69, 2093–2112. [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Hu, Y.; Lv, N.; Eradication of Helicobacter Pylori Reduces Gastric Cancer Risk by Preventing Gastric Mucosal Atrophy and Intestinal Metaplasia. Cancer Screen Prev 2024, 3, 227–229. [CrossRef]

- Massip C.; Branchu P.; Bossuet Greif N.; Chagneau C.V.; Gaillard D.; Martin P., et al.; Deciphering the interplay between the genotoxic and probiotic activities of Escherichia coli Nissle 1917. PLoS Pathog. 2019, 15(9), e1008029. [CrossRef]

- Nougayrède J.P.; Chagneau C.V., et al.; Genotoxic activity of probiotic strain Escherichia coli Nissle 1917. mSphere 2021, 6(4), e00624 21. [CrossRef]

- Falzone L.; Lavoro A.; Candido S.; Salmeri M.; Zanghì A.; Libra M.; Benefits and concerns of probiotics: an overview of the potential genotoxicity of the colibactin-producing Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 strain. Gut Microbes 2024, 16(1), 2397874. [CrossRef]

- Lv, C.; Abdullah, M.; Su, C.-L.; Chen, W.; Zhou, N.; Cheng, Z.; Chen, Y.; Li, M.; Simpson, K.W.; Elsaadi, A.; et al. Genomic Characterization of Escherichia Coli with a Polyketide Synthase (Pks) Island Isolated from Ulcerative Colitis Patients. BMC Genomics 2025, 26, 19. [CrossRef]

- Sonnenborn U.; Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 from bench to bedside and back: history of a special E. coli strain with probiotic properties. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2016, 363(19), fnw212.

- Bourgieux, A.; Deneys, V.; Maji, J. Citrobacter spp. are Gram-negative bacilli in the Enterobacteriaceae family, ferment glucose, and grow well on selective enteric media. ScienceDirect Topics (2025).

- Kostic A.D.; Gevers D.; et al. Association of Fusobacterium nucleatum in colorectal carcinoma and its clinical implications. Oncology 2019, 12(3), 368. [CrossRef]

- Vaqueiro P.; et al. Intratumoural pks+ E. coli as a risk factor for metachronous colorectal cancer in Lynch syndrome patients. EBioMedicine 2025, 58, 103421. [CrossRef]

- Jabeen, I.; Islam, S.; Hassan, A.K.M.I.; Tasnim, Z.; Shuvo, S.R. A Brief Insight into Citrobacter Species - a Growing Threat to Public Health. Front. Antibiot. 2023, 2, 1276982. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).