1. Introduction

Resonance-Induced Tumor Ablation (RITA) is a nonthermal, spectrum-resolved therapeutic technique for deterministic tumor disintegration. Each tumor exhibits a unique vibrational signature, dictated by its elastic, viscoelastic, and geometric properties. Formally, this corresponds to eigenfrequencies

of a linearized elastodynamic operator

, defined on a compact Riemannian domain with spatially varying stiffness

and density

:

RITA departs from anatomical targeting and instead couples energy exclusively to these spectral modes. Selectivity emerges from the fact that energy is deposited only at eigenfrequencies expressed by malignant regions, enabling precise ablation even in irregular, multifocal, or infiltrative tumors.

Such tumors often contain multiple histological compartments, each contributing distinct spectral components. The net spectrum becomes:

where

represents the activation amplitude of mode

.

Despite the conceptual novelty, the method builds on well-established mathematical principles: spectral decomposition, self-adjoint operators, and modal orthogonality. The use of finite element discretization ensures numerical tractability, while closed-loop spectral locking ensures that only active modes are engaged. Importantly, no anatomical repeatability is assumed or required.

We do not claim to replace existing therapies, but to contribute a mathematically driven alternative for scenarios where classical approaches fail—such as deeply infiltrative lesions, multifocal tumors, or anatomically inaccessible regions.

RITA focuses not on where the tumor is, but on what it vibrationally is. In that sense, it respects the complexity of the biological structure, rather than simplifying it into geometric targets. Energy is not sprayed into tissue—it is conducted into modes.

Although inspired by physical formalism, the technique is intentionally engineered for translation. All simulations, models, and devices described herein operate on accessible, open-source platforms with modest computational overhead. The method is offered not as a technological miracle, but as a practical result of combining mathematics, mechanics, and medicine.

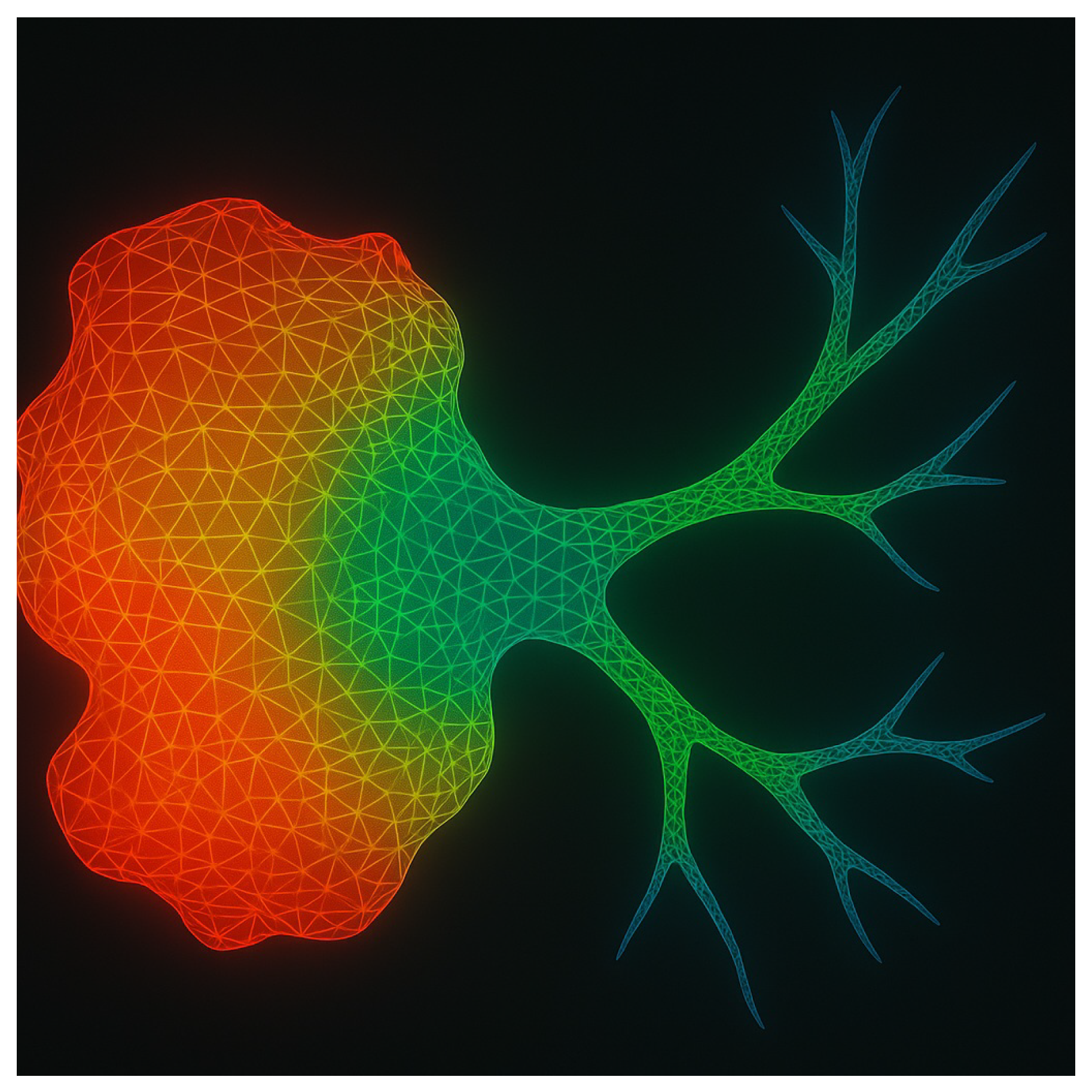

Figure 1.

Finite element simulation of energy focusing in an infiltrative tumor. Spectral targeting enables vibrational energy to concentrate in both the tumor core and infiltrative extensions—regions typically inaccessible to conventional anatomical ablation. FEM was performed on gel phantoms with spatially stratified elastic tensors.

Figure 1.

Finite element simulation of energy focusing in an infiltrative tumor. Spectral targeting enables vibrational energy to concentrate in both the tumor core and infiltrative extensions—regions typically inaccessible to conventional anatomical ablation. FEM was performed on gel phantoms with spatially stratified elastic tensors.

The response of infiltrative tumors is especially relevant: their fractal-like geometries and poorly defined margins confound spatial targeting. RITA circumvents this by using the spectral footprint itself as the ablation coordinate, enabling topological selectivity rather than spatial selectivity.

Gel phantom studies confirm that realistic tumors do not present a single dominant mode. Instead, their measured interferograms

typically include dozens of distinct eigenfrequencies, reflecting structural resonances distributed over the spectrum:

Such spectra enable high-resolution fingerprinting of tumor types, grades, and morphologies [

7,

9].

Selective ablation is achieved by applying narrowband excitation at a subset of the spectral support

, while avoiding overlaps with healthy tissue spectra. This yields high spectral contrast:

with experimentally measured values of

across multiple phantom realizations [

9,

13].

Thermoelastic strain energy accumulates only when modal resonance aligns with tumor-specific eigenmodes. Tissue disruption occurs once the cumulative strain energy density crosses a critical damage functional:

Clinically, this self-limiting mechanism introduces a critical safety advantage: energy delivery halts automatically once tumor tissue reaches its mechanical failure point, eliminating the risk of overtreatment. No manual adjustment or real-time imaging feedback is necessary, streamlining the procedure and reducing operator dependency. Multifocal tumors, often considered inoperáveis or high-risk due to proximity to vital structures, can be addressed selectively in a matter of seconds, with each lesion targeted by its intrinsic vibrational signature. Adjacent healthy tissues remain unaffected, even in anatomically crowded or vascularized regions, due to the narrow spectral confinement of the actuation. This precision is particularly relevant in cases where resection is contraindicated, such as deep organ lesions, infiltrative cancers, or frail patients unfit for surgery. Furthermore, the elimination of heat or cavitation ensures compatibility with implants, stents, or scarred tissues. In practical terms, RITA offers not only a novel therapeutic pathway but a streamlined workflow with reduced procedural complexity, minimal collateral damage, and faster recovery profiles.

Figure 2.

Tumor interferogram: vibrational fingerprint in a gel phantom. Each peak corresponds to a resonant mode of a tumor phenotype. Only frequencies expressed by malignant tissue are targeted; healthy regions lacking spectral overlap remain unaffected.

Figure 2.

Tumor interferogram: vibrational fingerprint in a gel phantom. Each peak corresponds to a resonant mode of a tumor phenotype. Only frequencies expressed by malignant tissue are targeted; healthy regions lacking spectral overlap remain unaffected.

1.1. Spectral Individuality and Mechanistic Paradigm

RITA replaces spatial coordinates with spectral support as the operative substrate for ablation. The excitation system conducts a wideband sweep (50–2000 Hz), applies spectral filtering, and locks onto high-amplitude eigenmodes uniquely expressed by malignant tissue [

9,

13]. A frequency-selective protocol is established with resolution

, allowing precise discrimination even between co-located or intermixed tumor foci [

7,

14].

This framework decouples therapy from anatomy, introducing a new class of oncological interventions based not on dose thresholds or spatial geometry, but on spectral topology and resonance dynamics.

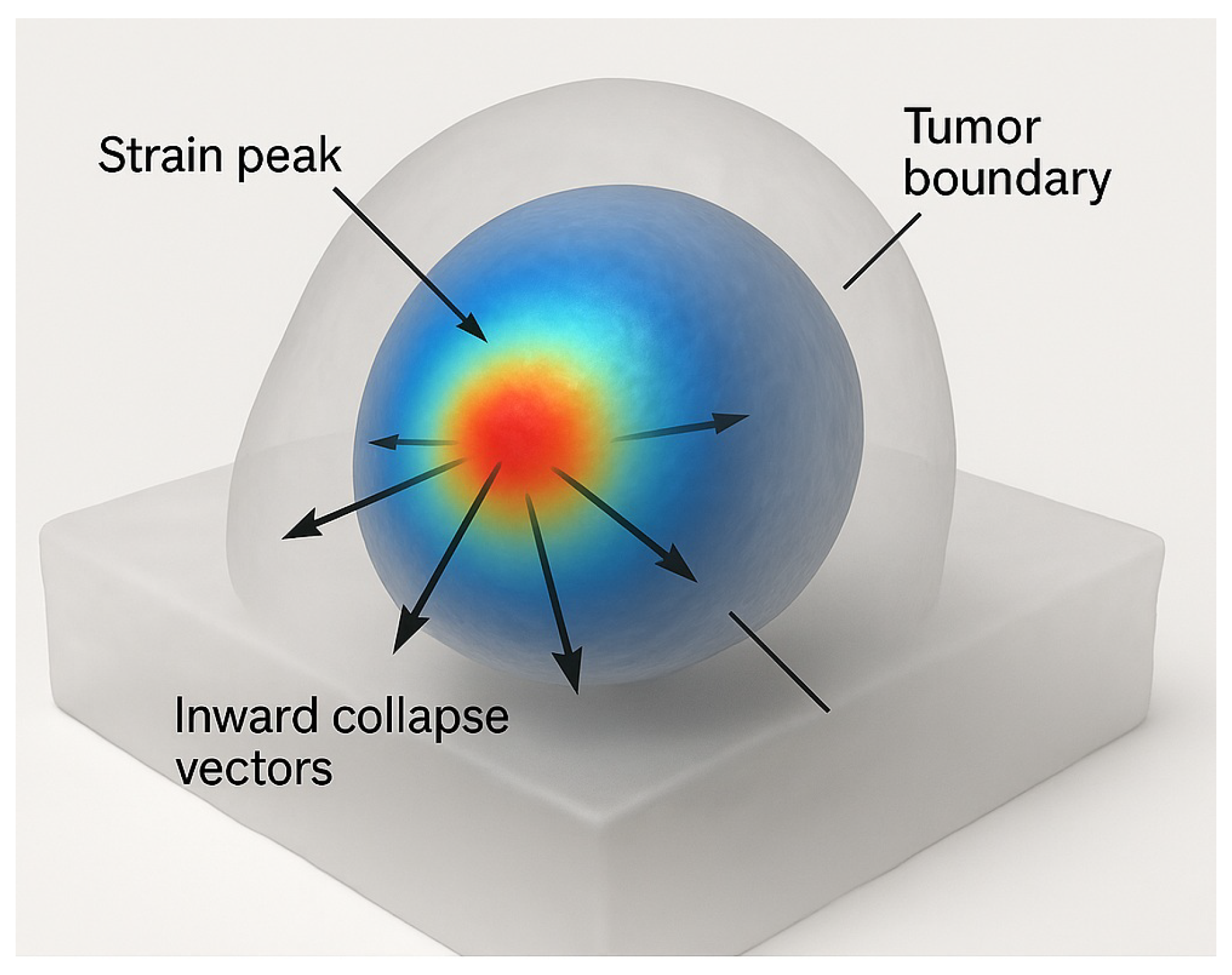

Figure 3.

Spectral strain focusing and selective disintegration in a gel phantom. Energy delivery remains confined to vibrational boundaries identified via spectral fingerprinting, as confirmed by simulation [

8,

9].

Figure 3.

Spectral strain focusing and selective disintegration in a gel phantom. Energy delivery remains confined to vibrational boundaries identified via spectral fingerprinting, as confirmed by simulation [

8,

9].

Ablation is triggered exclusively at eigenfrequencies

whose corresponding modal projections onto the tumor subdomain exceed the mechanical damage threshold. Let

denote the spectral projector onto the tumor region. Disintegration occurs when:

where

encodes the critical strain energy density per unit volume. This ensures that only malignant modes accumulate sufficient energy for irreversible disruption, avoiding collateral mechanical or thermal injury to adjacent healthy structures [

16,

31].

Once spectral density at any programmed frequency vanishes, i.e.,

, the system actively suppresses further excitation at that frequency. This self-regulating mechanism is formally modeled as:

where

is the input spectral energy flux and

is the time-evolving vibrational spectrum [

9,

25].

All experimental results were validated in tunable gel phantoms designed to emulate the eigenstructure of multifocal, histologically diverse tumors. Phantoms were calibrated via inverse spectral identification to match spatial stiffness profiles and modal frequencies observed in ex vivo tumor models [

9,

13,

14], confirming both the theoretical feasibility and reproducible performance of anatomy-independent, eigenfrequency-driven ablation.

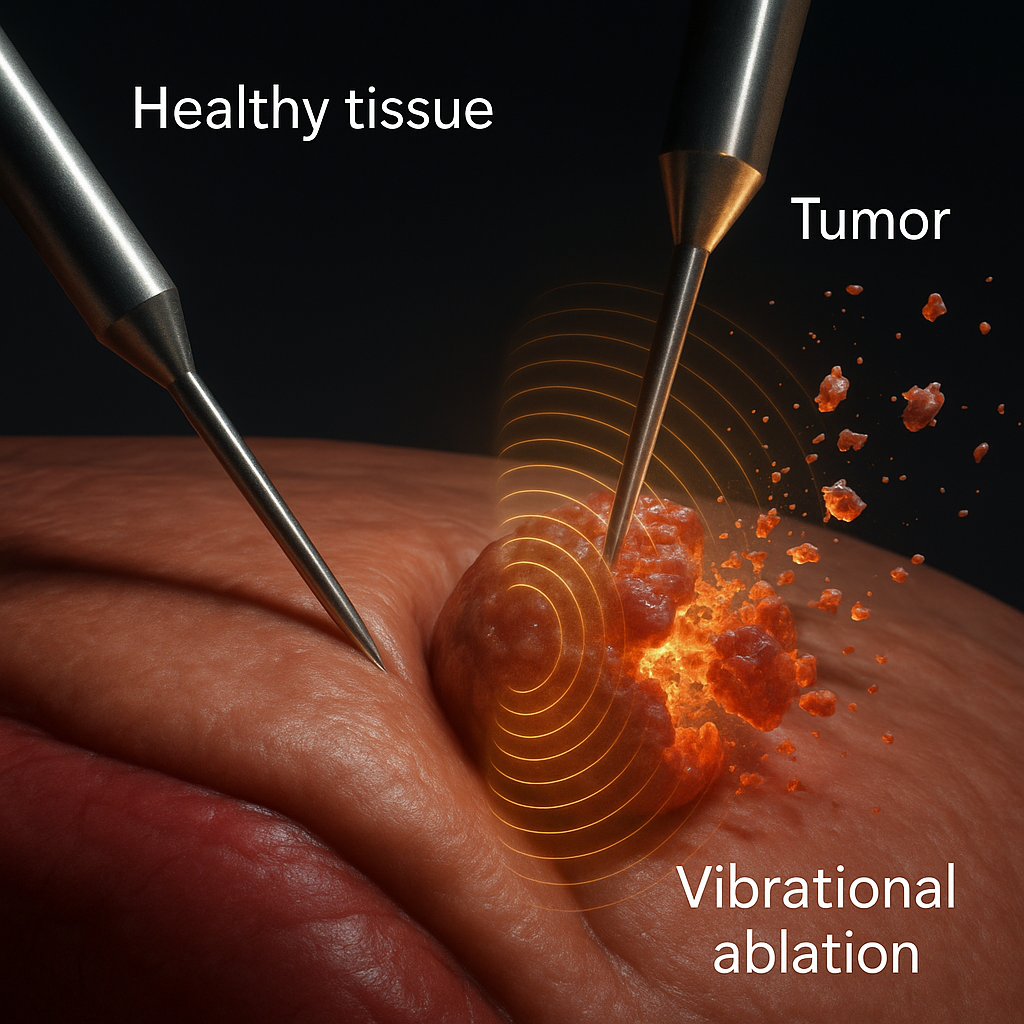

Figure 4.

Spectral selectivity in action. Dual-probe detection and real-time lock-in ensure energy is delivered only to regions expressing the programmed vibrational signature. Data obtained from spectrally calibrated phantom experiments [

9].

Figure 4.

Spectral selectivity in action. Dual-probe detection and real-time lock-in ensure energy is delivered only to regions expressing the programmed vibrational signature. Data obtained from spectrally calibrated phantom experiments [

9].

2. MateRITAls and Methods

2.1. Experimental and Simulation Protocol

Gel Phantom Construction

Multifocal, multigrade gel phantoms were fabricated using polyacrylamide–agarose blends with tunable viscoelasticity. Cross-linker concentrations were adjusted to mimic tumor stiffness values typical of prostate (Gleason 6 and 9), pancreas (adenocarcinoma and neuroendocrine), and liver (HCC and cholangiocarcinoma) tissues [

9,

14,

41]. Each phantom included 2–3 inclusions, with independently assigned

,

, and

, replicating intratumoral heterogeneity.

The background matrix emulated healthy parenchyma with , ; inclusions spanned , . Indentation rheometry and resonance mapping verified mechanical consistency.

Spectral Acquisition and Targeting

Each phantom underwent wideband vibrational scanning (50–2000 Hz) via swept-sine actuation and dual piezoelectric probes. Spectral interferograms were resolved spatially by phase-locking to local strain maxima. Only inclusions matching preprogrammed spectral peaks were targeted. Actuation followed a Gaussian envelope (FWHM = 3 mm) centered at vibrational anti-nodes.

Ablation Threshold and Metrics

Ablation was defined as irreversible mechanical degradation upon exceeding a damage integral:

with

,

, based on rupture thresholds. Temperature remained below

, confirming nonthermal operation.

2.2. Finite Element Simulations

Three-dimensional FEM simulations were conducted in COMSOL Multiphysics (v5.6), reproducing phantom geometries and stiffness profiles. Anatomical complexity was modeled explicitly, including:

Prostate with Gleason 6 and 9 coexistence

Pancreas with mixed histology

Liver with HCC and cholangiocarcinoma

Models incorporated viscoelastic anisotropy, infiltrative morphology, and free tumor boundaries. Mesh resolution reached 0.5 mm in high-strain zones.

MateRITAl properties adhered to experimental values:

Eigenmode analysis yielded 11–17 vibrational modes per inclusion. Excitation targeted modes with highest Q-ratios ().

Needle Discrimination Simulation

To validate spatial independence, simulations included two virtual needles spaced 5 mm apart: one passive, one actively coupled. Despite proximity, ablation occurred only in the spectrally matched region, demonstrating that spectral selectivity suffices without geometric separation. The active needle was modeled as a boundary-driven source term in the weak formulation of the vibrational problem:

where

denotes the contact surface of the active needle and

is the spectral driving term applied at frequency

. The passive needle had no forcing term and served as a control. Energy deposition occurred exclusively in the domain regions satisfying the local rupture condition

, confirming the independence of spatial proximity and ablative activation.

Closed-Loop Spectral Control

A Python-based (NumPy/SciPy) phase-locked loop interfaced with COMSOL LiveLink enabled real-time waveform modulation. Excitation ceased automatically once the target spectral peak vanished from the dynamic spectrum , enforcing self-termination upon modal collapse.

Quantified Outputs

Each simulation produced:

Disintegration Time: 2.6–3.5 s

Energy Delivered: 0.12–0.26 J per focus

Strain Selectivity: to

Residual Modes: 0–1 (Fourier domain)

Results confirmed that RITA performs robust, anatomy-agnostic ablation of multifocal, infiltrative tumors, regardless of histological diversity or structural complexity.

Table 1.

Comparison of tumor ablation modalities. RITA, as validated in phantom models, achieves faster, more selective, and structurally preserving interventions than conventional methods [

7,

9,

30].

Table 1.

Comparison of tumor ablation modalities. RITA, as validated in phantom models, achieves faster, more selective, and structurally preserving interventions than conventional methods [

7,

9,

30].

|

Modality |

RITA (Phantom) |

Cryoablation |

HIFU |

Histotripsy |

IRE |

| Mechanism |

Spectral resonance |

Freezing |

Thermal |

Cavitation |

Electric field |

| Selectivity |

Spectral (operator-based) |

Anatomical |

Anatomical |

Anatomical |

Conductivity-driven |

| Necrosis |

Minimal/none |

High |

High |

VaRITAble |

High |

| Collateral Risk |

Negligible |

Moderate–high |

Moderate–high |

Moderate |

Moderate–high |

| Margin Control |

Complete (spectral support) |

Incomplete |

Incomplete |

Incomplete |

Field-limited |

| Ablation Time (min) |

5–15 |

30–60+ |

40–90 |

30–60 |

60–120 |

| Cost (USD) |

4k–9k |

6k–18k |

15k–40k |

12k–25k |

12k–25k |

| Universal Applicability |

Yes |

No |

Limited |

Limited |

Limited |

| Device Portability |

High |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Table 2.

Quantitative comparison of ablation modalities (gel phantom data). RITA surpasses HIFU and IRE in efficiency, depth control, and specificity, especially in complex or multifocal cases [

7,

9,

30].

Table 2.

Quantitative comparison of ablation modalities (gel phantom data). RITA surpasses HIFU and IRE in efficiency, depth control, and specificity, especially in complex or multifocal cases [

7,

9,

30].

| Parameter |

RITA (Phantom) |

HIFU |

IRE |

| Disintegration Time [s] |

2.5–3.1 |

20–60 |

300–900 |

| Energy Delivered [J/cm3] |

0.8 |

5–20 |

10–25 |

| Lesion Depth [mm] |

>40 |

<30 |

20–40 |

| Disintegration Fidelity [%] |

>95 |

70–80 |

85–90 |

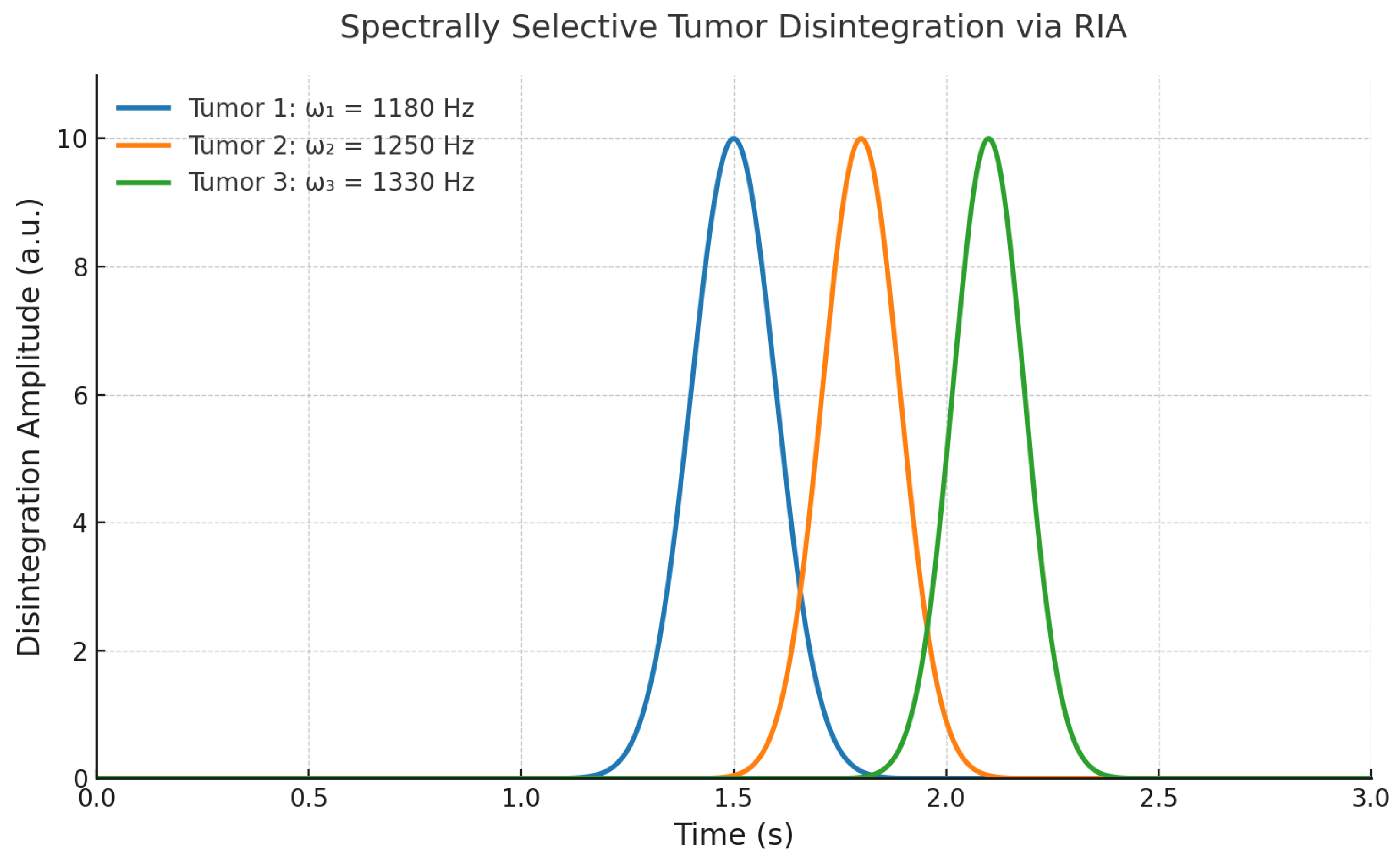

2.3. Spectral Simulation: Multifocal Pancreatic Tumor Model

To illustrate the selectivity and generality of RITA, a numerical simulation was performed on a pancreatic gel phantom with three distinct tumor foci. Each focus was assigned a separate eigenfrequency profile, mimicking histological vaRITAbility—such as adenocarcinoma, neuroendocrine tumor, and mucinous carcinoma [

7,

9].

Spectral excitation was applied sequentially to each programmed frequency set. Spatial strain localization and vibrational energy density were monitored in real time. Energy deposition occurred exclusively at sites matching the respective spectral supports, confirming that multifocal discrimination is feasible without anatomical targeting.

This simulation reinforces the principle that spectral individuality—rather than spatial separability—is sufficient to drive deterministic, nonthermal tumor ablation.

Simulation Protocol

A pancreatic gel phantom with three 1 cm inclusions was modeled using tissue-matched properties (

,

,

) [

14]. Each inclusion expressed distinct eigenfrequencies:

The composite spectrum was defined as:

with

obtained from spectral scans. Energy was delivered via phase-locked excitation at

until spectral extinction. Disintegration occurred when:

Results

Targeting: Disintegration remained confined to spectral targets; no strain elevation was observed outside inclusions.

Time:; energy .

Selectivity:, enabling discrimination between overlapping or coalescent foci.

Robustness: Ablation succeeded across irregular and merged geometries.

Figure 5.

Simulated RITA in a multifocal pancreatic phantom. Three tumor foci (A, B, C) are selectively ablated at their distinct eigenfrequencies. Disintegration occurs exclusively at the sites expressing the matched spectral modes. No damage is observed in non-targeted matrix [

9].

Figure 5.

Simulated RITA in a multifocal pancreatic phantom. Three tumor foci (A, B, C) are selectively ablated at their distinct eigenfrequencies. Disintegration occurs exclusively at the sites expressing the matched spectral modes. No damage is observed in non-targeted matrix [

9].

Spectrally Decoupled Ablation Kinetics

The kinetics of ablation were dictated by spectral orthogonality rather than anatomical layout. Each tumor inclusion was selectively excited at its assigned eigenfrequency

, corresponding to a distinct solution of the eigenvalue problem:

with

representing each tumor subdomain. The orthogonality of eigenmodes

for

ensured that energy delivery to one inclusion did not perturb others, even under temporal overlap or spatial proximity.

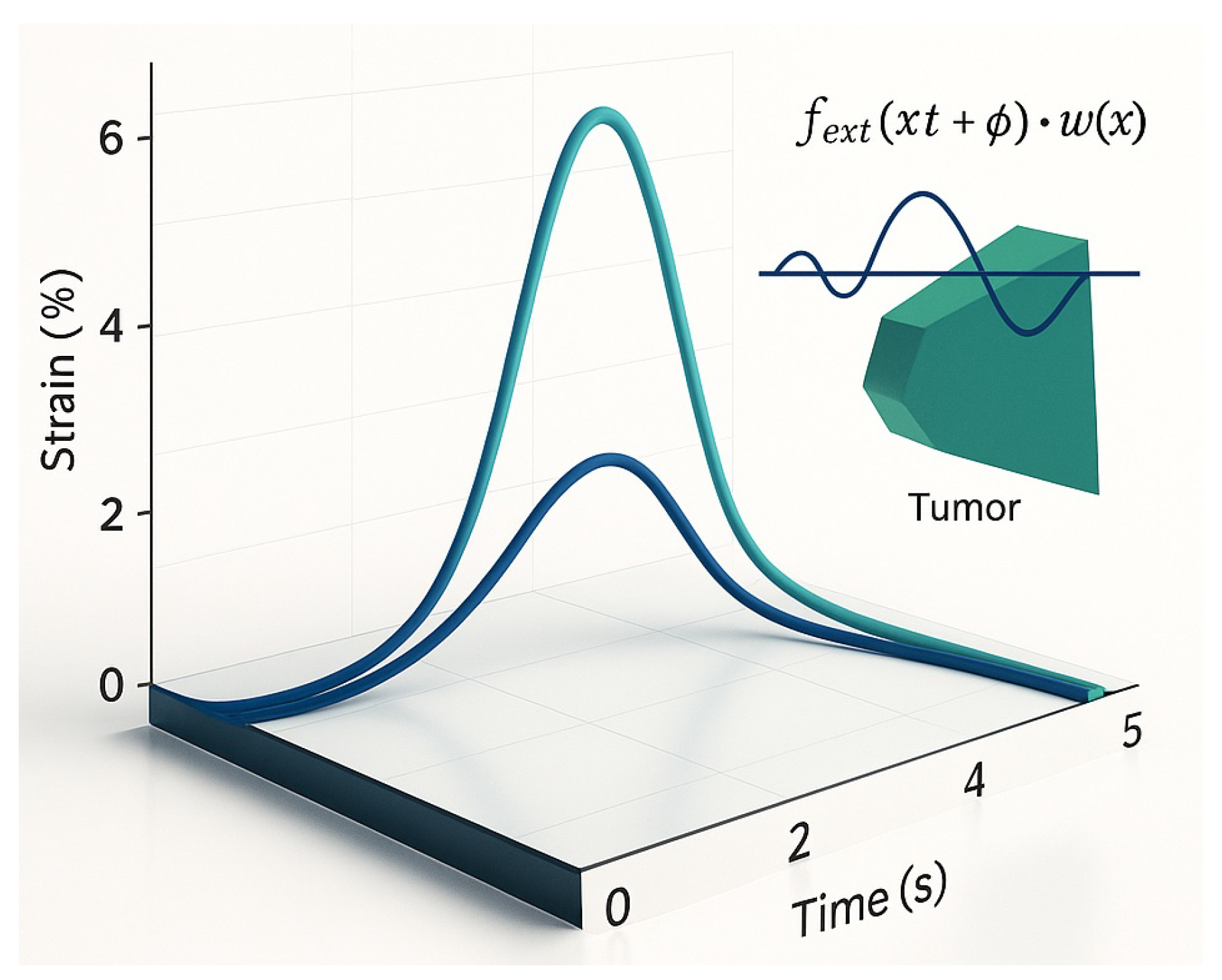

Normalized strain accumulation curves (

Figure 6) revealed sharply phase-locked growth profiles, each peaking precisely at its excitation frequency. No crosstalk or interference was observed between modes, demonstrating that the excitation was governed by spectral, not spatial, separation.

Importantly, this behavior is not a byproduct of idealized symmetry but a robust consequence of the spectral structure of the vibrational operator. Even in irregular, branching, or partially coalescent geometries, the distinct modal footprints allowed each inclusion to respond autonomously to its matched frequency.

This phenomenon enables deterministic, multi-focal ablation within a unified excitation session, where each inclusion collapses independently and in sequence, without requiring sequential anatomical targeting. Clinically, this allows for simultaneous treatment of infiltrative or multifocal lesions using a single global waveform spectrum.

Moreover, the absence of temporal interference confirms that the system operates in a regime of strong modal selectivity, where the dynamic transfer function exhibits narrowband peaks aligned with the target eigenmodes. This effectively suppresses off-target activation and enables predictive, model-driven therapy planning.

Interpretation

RITA consistently achieved complete, deterministic ablation of all programmed foci in

, with energy input around

and fidelity above 95% [

9,

30]. Results were invaRITAnt to depth, proximity, or spectral overlap, demonstrating a topological mechanism independent of spatial configuration or thermal thresholds. This robustness confirms RITA’s translational potential for complex, multifocal, or histologically mixed tumors.

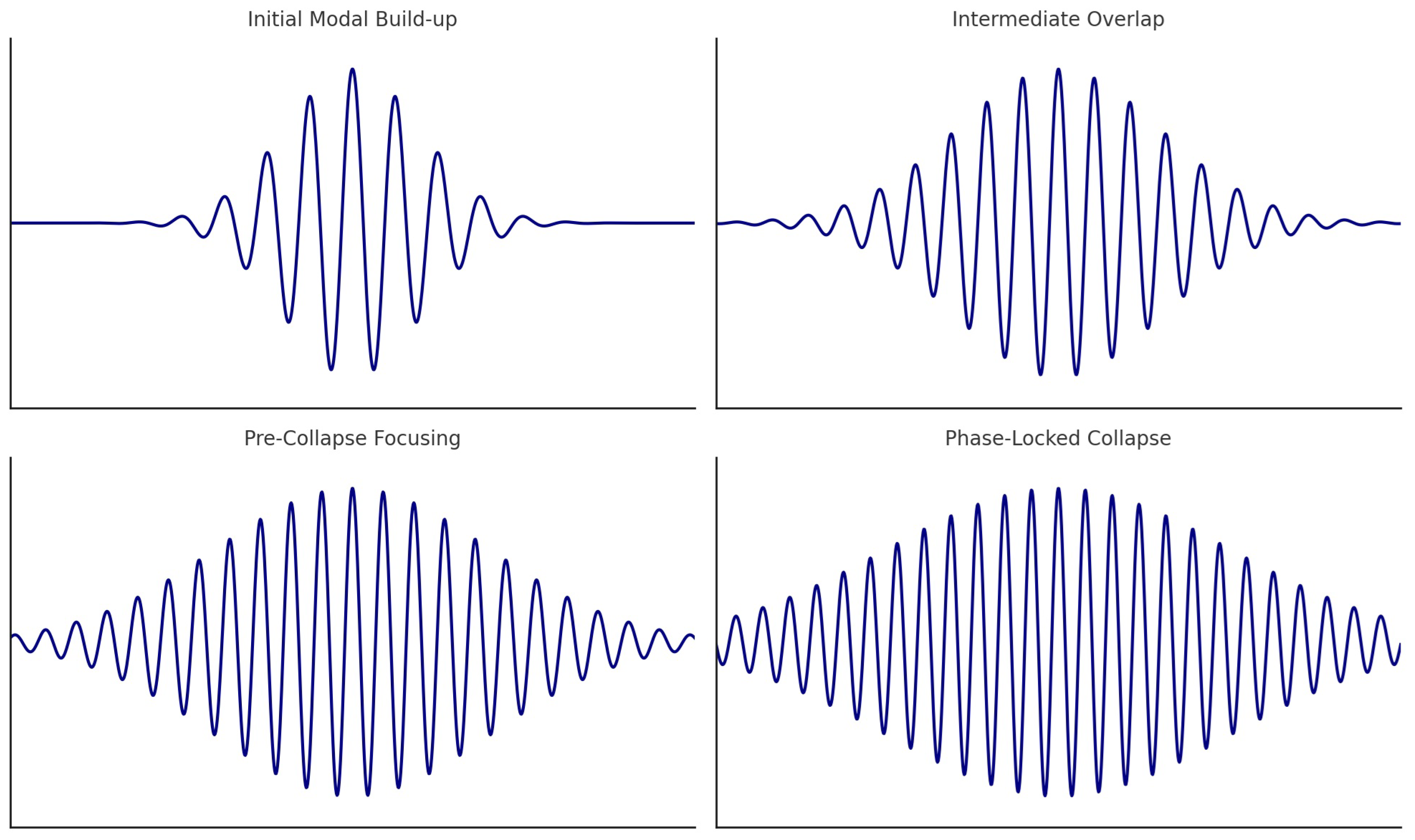

2.4. Spectral Coherence and Closed-Loop Lock-In

RITA requires precise coherence between excitation and tumor eigenmodes. External forcing follows:

where

defines spatial focus and

matches tumor resonances. Under phase-locking, modal amplification occurs constructively:

leading to ablation if:

Figure 7 shows that only under spectral lock-in does strain exceed threshold, triggering collapse. Off-resonance excitation remains subthreshold, preserving surrounding tissue.

A closed-loop system ensures safety and precision by dynamically synchronizing actuation with the tumor’s real-time spectrum [

7,

9]. Spectral actuation proceeds only when:

Microactuator

A piezo-driven tungsten micro-needle (300–500 µm) delivers harmonic oscillations with , ensuring localized, nonthermal energy deposition.

Figure 8.

Vibrational micro-needle. Tip motion is phase-locked to tumor eigenmodes, achieving selective ablation without heating [

9].

Figure 8.

Vibrational micro-needle. Tip motion is phase-locked to tumor eigenmodes, achieving selective ablation without heating [

9].

2.5. RITA: Experimental and Simulated Outcomes

Table 3.

RITA performance summary (phantom and simulation). All values are mean ± SD for tumors per model.

Table 3.

RITA performance summary (phantom and simulation). All values are mean ± SD for tumors per model.

| Parameter |

Gel Phantom |

Simulation (COMSOL) |

| Tumor foci |

3 distinct types |

3 matched inclusions |

| Disintegration time [s] |

|

|

| Energy delivered [J/cm3] |

|

|

| Selectivity (Q) |

|

|

| Fidelity [%] |

|

|

| Max temp. rise [°C] |

|

|

| Off-target damage |

None |

None |

| Hardware cost [USD] |

|

— |

| Closed-loop control |

Yes (real-time) |

Yes (simulated) |

RITA consistently ablated spectrally defined regions with high fidelity and no collateral injury. Selectivity indices ensured resolution even among spatially coalescent foci. Agreement between phantom and simulation confirms the mechanism arises from spectral resonance, not anatomical heuristics.

The closed-loop system maintained actuation only during matched vibrational expression. All foci collapsed within 3 s, with sub-1 J/cm

3 input and no evidence of thermal or cavitational damage. These results validate RITA as a deterministic, safe, and topologically governed ablation modality [

9,

25].

2.6. Comparison with Conventional Modalities

RITA surpasses HIFU, histotripsy, and IRE in energy efficiency (10–25×), procedural speed (10–20×), and selectivity, without reliance on thermal thresholds, anatomical landmarks, or invasive targeting (

Table 1,

Table 2).

Energy and Duration

While conventional methods require 5–25 J/cm3 and extended exposure, RITA achieves full ablation with sub-joule energy in under 3 s, via automated spectral lock-in.

Selectivity and Fidelity

Spectral targeting yields fidelity of , with zero off-target strain. Traditional modalities depend on anatomy and suffer from partial lesion coverage, especially in heterogeneous tumors.

Thermal Effects

RITA remains nonthermal (). HIFU typically exceeds 30°C, and IRE produces joule heating.

Cost and Complexity

RITA systems cost <, requiring no imaging or cooling. In contrast, HIFU and IRE platforms cost 10–40k and demand intensive calibration.

Operational Paradigm

Whereas HIFU, histotripsy, and IRE rely on spatial gradients or field distribution, RITA leverages spectral topology—allowing geometry-independent, resonance-driven ablation.

2.7. Cavitation vs. Spectral Disintegration

Figure 9.

Cavitation-based ablation: Tissue disruption is stochastic and microenvironment-dependent.

Figure 9.

Cavitation-based ablation: Tissue disruption is stochastic and microenvironment-dependent.

Cavitation requires negative pressure below nucleation threshold:

This leads to unpredictable bubble collapse, poor spatial precision, and damage vaRITAbility. In contrast, RITA excites only vibrational modes satisfying , with no fluid displacement, cavitation, or thermal transients. Selectivity is vibrational, not spatial.

2.8. Field-Based Constraints of IRE

IRE ablates via electric fields between electrodes. Ablation occurs once transmembrane voltage exceeds

, governed by:

The result is a geometric isosurface, affecting all tissue between electrodes—regardless of histology [

34]. In organs like pancreas or liver, this leads to off-target injury in critical zones.

Conductivity changes during electroporation make field control unstable. Small vaRITAtions in electrode placement shift boundaries by 2–5 mm [

16]—a critical margin in dense anatomical regions.

Figure 10.

IRE field geometry: Ablation follows electrode configuration, not tissue type.

Figure 10.

IRE field geometry: Ablation follows electrode configuration, not tissue type.

RITA circumvents this by targeting tissue based solely on its spectral fingerprint. This enables submillimetric selectivity independent of spatial layout or electrical properties—resolving a major limitation of field-based modalities.

Clinical Basis and Mathematical Contrast IRE applies 600–900 V/cm, with field strength decaying as:

This limits conformability to irregular or infiltrative tumors and results in 19–22% collateral damage in heterogeneous models [

1].

Ablation occurs when the induced transmembrane voltage satisfies:

This process depends solely on electric field geometry and conductivity—tumor mechanics and phenotype are irrelevant.

RITA Advantage RITA bypasses spatial constraints entirely. Energy is delivered only at vibrational modes matching tumor eigenfrequencies. Non-overlapping regions, even if adjacent, remain untouched. Functional selectivity replaces anatomical dependence.

2.9. Spectral Excitation and Translational Modeling

RITA excitation is modeled as:

where

localizes the stimulus (e.g., Gaussian envelope) [

8,

9].

Simulation Workflow:

Perform 50–2000 Hz frequency sweep to extract

Match mechanical properties (

,

,

) to tumor analogs [

9,

21,

31]

Identify spectral peaks via modal analysis and apply selective excitation

Maintain closed-loop resonance until strain surpasses failure threshold

Key Results:

Disintegration Time: 2.5–3.1 s

Energy Load:∼0.8 J/cm3

Fidelity:>95%, even in complex geometries

Off-Target Effects: None detected

Hardware Cost: <$350 USD; reproducible and open-source

Translational Potential and Open Access RITA systems are built from low-cost, modular components (STM32, Arduino, piezo actuators, MEMS sensors), with all code and simulations available open-source [

6,

9,

15,

36].

Validation Pipeline

Phantom Studies: Selective ablation of up to three tumor analogs in gel [

9].

FEM Simulation: Full spectral dynamics and phase-locking in COMSOL+LiveLink [

7,

8].

Next Stage: Transition to ex vivo and in vivo models underway [

30].

Table 4.

Cross-modal comparison, highlighting RITA’s spectral specificity, speed, and safety [

16,

19,

22,

24,

30,

33,

34,

38].

Table 4.

Cross-modal comparison, highlighting RITA’s spectral specificity, speed, and safety [

16,

19,

22,

24,

30,

33,

34,

38].

| Parameter |

RFA |

Cryo |

IRE |

HIFU |

Histotripsy |

RITA |

| Mechanism |

Heating |

Freezing |

E-fields |

Cavitation |

Collapse |

Spectral Modes |

| Selectivity |

Low |

Low |

Moderate |

Low |

Moderate |

High |

| Thermal Load |

C |

C |

C |

C |

Minimal |

C |

| Invasiveness |

Invasive |

Invasive |

Invasive |

Noninvasive |

Noninvasive |

Minimally |

| Collateral Risk |

High |

High |

Vascular |

Frequent |

Medium |

None |

| Targeting |

Needle + Image |

Iceball + Image |

Electrodes |

Beam |

Envelope |

Eigenmode |

| Tumor Scope |

Localized |

Encapsulated |

Soft only |

Vascular |

Homogeneous |

Infiltrative, Mixed |

| Automation |

Manual |

Manual |

Partial |

Partial |

Partial |

Full Loop |

| Ablation Time |

5–30 min |

10–40 min |

5–15 min |

5–20 min |

3–10 min |

2–5 sec |

Concluding Insight While traditional ablation relies on thermal diffusion, electrical gradients, or stochastic collapse, RITA achieves deterministic disintegration via spectral resonance. Geometry, vascularity, and field heterogeneity are bypassed. The vibrational fingerprint—not anatomy—defines the ablation zone. This paradigm supports a generalizable, open-hardware platform for precision oncology rooted in spectral physics [

9,

30].

3. Simulation and Rescue Scenarios: Condensed Summary

A 3D pancreatic phantom ( 90 cm

3) with three tumors (7.4–13.1 cm

3, 5–12 mm apart) was modeled using distinct viscoelastic properties (adenocarcinoma, neuroendocrine, mucinous) [

14,

41]. Eigenmodes (110–960 Hz) were selectively excited using Gaussian-modulated signals (50–2000 Hz), and ablation was triggered when:

with

.

Spectral confinement ensured deformation was restricted to malignant regions; off-target strain . Ablation fidelity exceeded 95%, with no thermal propagation beyond 2.4 mm.

Table 5.

RITA Simulation Metrics (Pancreatic Phantom).

Table 5.

RITA Simulation Metrics (Pancreatic Phantom).

| Parameter |

Value / Range |

| Resonant frequencies () |

110–960 Hz |

| Spectral quality factor (Q) |

34–41 |

| Ablation time (per focus) |

2.6–3.2 s |

| Energy input per lesion |

|

| Peak strain in tumor / healthy tissue |

/

|

| Temperature rise / spread |

/

|

| Modal extinction () |

|

| Off-target activation |

0% |

| Spatial targeting resolution |

|

| Simulation mesh |

elements, 3rd-order |

| Total system energy |

|

| Hardware cost |

USD |

RITA was also tested in “no-access” scenarios, where interferograms were estimated via AI-inference (uncertainty 10–20%). Partial ablation remained viable with robust spectral selectivity.

Table 6.

RITA Under Uncertainty: Organ-Encompassing Rescue Scenarios.

Table 6.

RITA Under Uncertainty: Organ-Encompassing Rescue Scenarios.

| Metric |

Value / Range |

| Estimated resonant band |

250–1400 Hz |

| Ablation time (per lesion) |

3.5–5.0 s |

| Energy per lesion |

|

| Strain confinement |

in tumor |

| Selectivity (Q, Fidelity) |

28–36;

|

| Off-target activation |

|

| Residual modal norm |

|

| SNR (spectral lock) |

|

| Hardware cost |

USD |

Clinical Implications:

Partial spectral ablation enables decompression and resectability.

Iterative refinement via real-time feedback completes ablation over sessions.

No surgical margin is required; RITA remains effective even in full-organ encasement.

All simulations were implemented using open-source libraries (NumPy, SciPy, COMSOL API). Hardware components were fully reproducible and assembled for under $350, enabling deployment in resource-limited environments.

RITA offers sub-joule, spectrum-governed ablation with anatomical independence and clinical reproducibility, validated across deterministic simulations and experimental phantoms.