1. Introduction

Coal gasification slag (CGS) is a typical industrial solid waste generated during the coal gasification process [

1]. With the widespread adoption of coal gasification, an efficient and cleaner coal utilization technology [

2], the discharge of its solid by-products (primarily coarse slag, CS, and fine slag, FS [

3]) has increased dramatically. Statistics indicate that China produces over 70 million metric tons of CGS annually [

4]. Currently, the vast majority of CGS is simply landfilled or stockpiled [

5,

6]. This practice not only consumes substantial land resources but also poses threats to water and soil environments due to the potential leaching risk of heavy metals [

7,

8]. Therefore, achieving the resource utilization of CGS is crucial for mitigating its adverse environmental impacts and promoting the sustainable development of the coal chemical industry [

9].

In mining environments, coal gangue, the primary solid waste arising from coal mining and washing processes [

10], also presents severe environmental problems due to its massive stockpiling. Coal gangue piles occupy extensive land areas and are prone to triggering geological hazards such as soil erosion, landslides, and debris flows [

11]. Furthermore, as they often contain pyrite and coal, they carry a risk of spontaneous combustion, releasing harmful substances including sulfur oxides (SO₂), nitrogen oxides (NOₓ), greenhouse gases, and benzo[a]pyrene [

12]. Critically, coal gangue frequently harbors various heavy metal elements, among which cadmium (Cd) is a highly toxic and mobile contaminant. Under the leaching action of precipitation, Cd is readily released from coal gangue into surrounding soils and groundwater [

13]. It can then accumulate in the food chain through crop uptake, posing serious threats to human health (e.g., causing kidney damage, osteoporosis) [

14] and disrupting ecosystem stability [

15,

16]. Consequently, developing efficient, economical, and environmentally friendly technologies to control the mobility and bioavailability of Cd in coal gangue is paramount for environmental remediation and ecological restoration in mining areas.

For the remediation of Cd-contaminated soils (including those affected by coal gangue leaching), the in-situ immobilization of heavy metals using passivators is a promising strategy. Carbon-based materials, clay minerals, and industrial solid wastes have been extensively studied for immobilizing Cd in soils. CGS exhibits potential for material applications due to its porous structure, richness in amorphous carbon [

17], and content of components such as SiO₂, Al₂O₃, CaO, and Fe₂O₃ [

18]. Its main utilization pathways include building materials [19-22], residual carbon recovery [23-25], water and soil treatment [

26,

27], and the preparation of porous materials [28-30]. Its layered carbon particles, possessing a large specific surface area, can be regarded as precursors for activated carbon [

31]. Previous studies have explored the adsorption performance of CGS for organic pollutants, such as propane [

32] and methylene blue [

33]. However, research on its direct application for heavy metal pollution remediation, particularly for Cd contamination in specific sources like coal gangue, remains relatively scarce. Transforming CGS into a remediation material for heavy metals in soils or solid waste matrices could realize the resource utilization concept of "waste control by waste" while yielding significant environmental co-benefits.

Nevertheless, unmodified raw CGS exhibits limited Cd passivation capacity and struggles to achieve long-term stable immobilization effects [

34]. To overcome this limitation and enhance its passivation performance, this study employed an iron salt impregnation method [

35] to modify CGS, producing iron-modified coal gasification slag (FGS). The objectives of this study are: (1) To evaluate the effect of FGS on the chemical speciation of Cd (specifically reducing the acid-extractable fraction and increasing the residual fraction proportion) in coal gangue through passivation experiments; and (2) To investigate the mechanism by which iron modification enhances the passivation capacity of CGS and elucidate the Cd passivation mechanism of FGS using characterization techniques including Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) and X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials

The coal gangue used in this study was sourced from the Buertai mining area. Coal gasification slag (CGS) was obtained from the Ordos Coal-to-Oil Plant. Iron-modified coal gasification slag (FGS) was prepared using an iron salt impregnation method. Briefly, 10 g of raw CGS was mixed with 100 mL of 2 mol/L NaOH solution [

36]. The mixture was stirred in a 90 °C water bath for 1.5 hours. After cooling to room temperature, the mixture was filtered and the residue washed with deionized water until the filtrate reached neutral pH. The washed residue was then dried to constant weight. Subsequently, the dried residue was mixed with a 1 mol/L FeCl₃ solution at a solid-to-Fe³⁺ mass ratio of 1:1.5. The mixture was allowed to stand for 3 hours, followed by filtration, washing with deionized water, and drying to obtain the final FGS material.

2.2. Adsorption

A cadmium adsorption kinetics experiment was conducted using a pure Cd solution. A 10 mL aliquot of a 100 mg/L Cd stock solution was diluted with 40 mL of deionized water in a centrifuge tube to achieve a final concentration of 20 mg/L. Then, 0.1 g of FGS was added to the centrifuge tube. The tube was placed in a constant-temperature incubator shaker maintained at 25°C with a shaking speed of 100 rpm. Supernatant samples were collected at specific time intervals (10, 30, 60, 120, and 300 minutes) for Cd concentration measurement. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

2.3. Characterization

The surface chemistry of the raw CGS, FGS, and Cd-loaded FGS was analyzed using Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR, VERTEX80V , Germany). Additionally, the elemental composition and chemical states were examined using X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS, ESCALAB 250Xi, American).

2.4. Passivation Experiment of Cadmium Contaminated Coal Gangue

To evaluate the Cd passivation capability of FGS, a comparative experiment was designed using iron-modified biochar (FBC) as a reference material, given its established use in heavy metal passivation studies. The passivators employed were FGS and FBC. For each experiment, 160 g of coal gangue was thoroughly mixed with the passivator at addition rates of 5% (8 g) and 10% (16 g) by mass of the coal gangue. The mixtures were then placed in a constant-temperature incubator with light control for a cultivation period of 10 days. Each treatment was performed with two replicates. After the cultivation period, samples were collected. The chemical speciation of Cd in the treated coal gangue was determined using the BCR (Community Bureau of Reference) sequential extraction procedure. This method fractionates Cd into four operationally defined forms: acid-extractable (F1), reducible (F2), oxidizable (F3), and residual (F4). Changes in the proportions of these fractions, particularly the decrease in the weak-acid-extractable fraction and the increase in the residual fraction, were used to assess the effectiveness of FGS in passivating Cd.

2.5. Analysis of Cd Fractions

The Cd concentration in the supernatant from the adsorption kinetics experiment was measured using Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry (ICP-OES, PerkinElmer Avio 200).

The BCR method was applied to analyze the chemical forms of Cd in the mixed sam-

ples, which were divided into weak-acid-extractable Cd (F1), reducible Cd (F2), oxidizable

Cd (F3), and residual Cd (F4). The required amount of coal gangue sample for this method

was 1.0 g. The extraction agents and methods for each form were as follows: 1.0 g of coal gangue sample was placed in a 50 mL polyethylene centrifuge tube, 40 mL of 0.11 mol/L acetic acid (CH₃COOH) was added, the mixture was shaken at 25°C for 16 h, centrifuged, and the supernatant collected for analysis; the residue from F1 extraction was treated with 40 mL of 0.5 mol/L hydroxylamine hydrochloride (NH₂OH·HCl), the mixture was shaken at 25°C for 16 h, centrifuged, and the supernatant collected for analysis; the residue from F2 extraction was treated with 10 mL of 8.8 mol/L hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) and digested at room temperature for 1 h, it was then placed in an 85°C water bath and digested for a further 1 h with intermittent manual shaking, another 10 mL of 8.8 mol/L H₂O₂ was added, and heating continued until the volume was reduced to near dryness, after cooling, 40 mL of 1 mol/L ammonium acetate (CH₃COONH₄) was added, the mixture was shaken at 25°C for 16 h, centrifuged, and the supernatant collected for analysis; 0.2 g of the residue remaining after the F3 extraction was transferred to a 50 mL polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) crucible, the residue was digested using a mixture of HCl-HNO₃-HClO₄-HF, after complete digestion, the solution was transferred to a 50 mL volumetric flask, made up to volume, and analyzed. After each extraction step, the supernatant was collected by centrifugation (4000 rpm) for 10 min and filtered. The Cd content in each extracted fraction was quantified using Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS, NexION 350X, PerkinElmer).

2.6. Data Analysis

The adsorption kinetics data were analyzed using pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second-order kinetic models to determine the equilibrium adsorption capacity[

37].

3. Results

3.1. Enhanced Hydroxyl Groups and New Functional Groups in Iron-Modified CGS

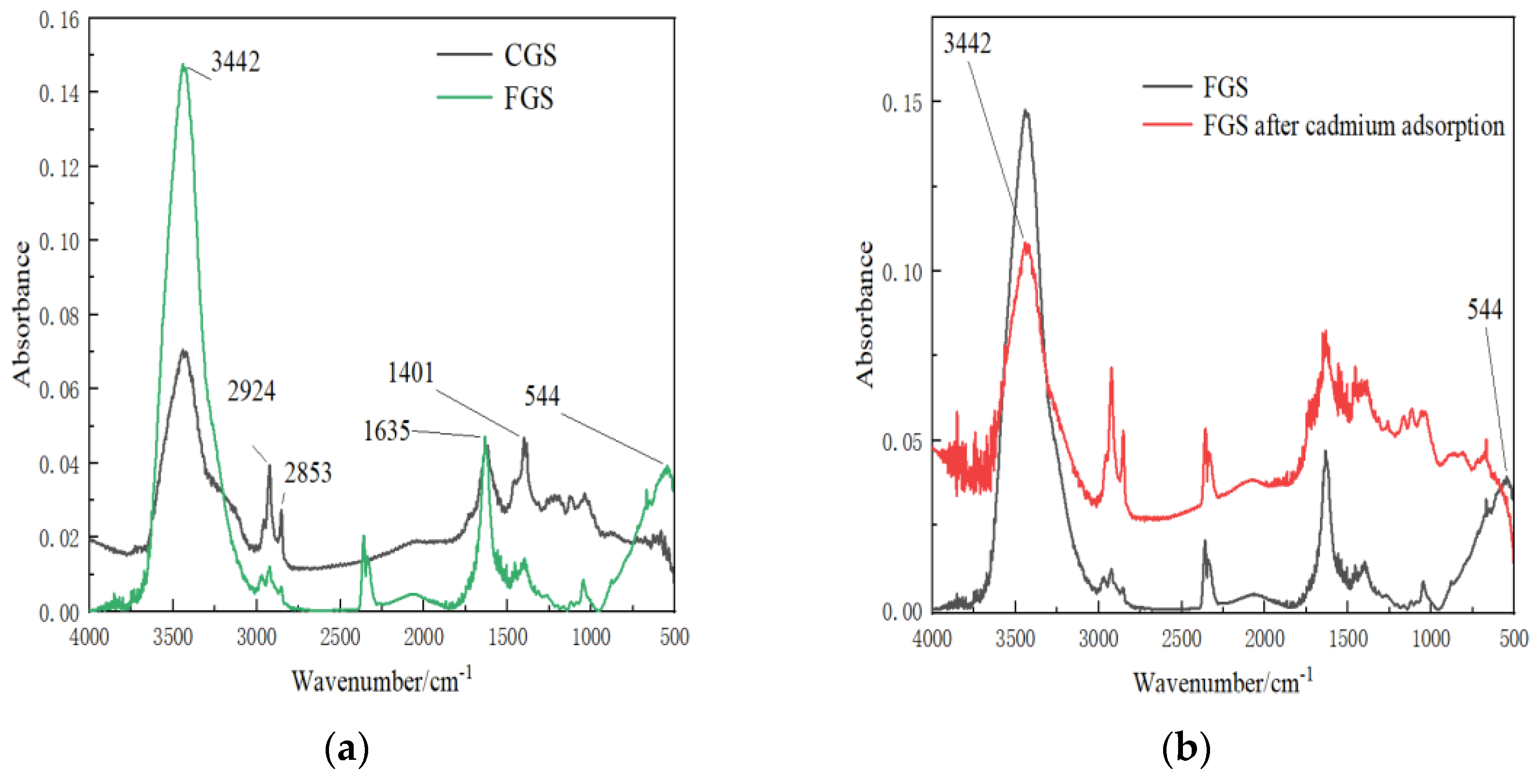

Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy analysis revealed significant changes in the surface functionality of coal gasification slag (CGS) following iron modification (

Figure 1a):

The iron-modified CGS (FGS) exhibited a pronounced enhancement in hydroxyl group density, with peak intensity in the hydroxyl characteristic region (∼3442 cm⁻¹) doubling compared to unmodified CGS. Furthermore, a distinct new absorption peak emerged at 544 cm⁻¹ in the FGS spectrum, attributed to Fe-O bond vibrations. No corresponding peak was observed in this region for pristine CGS.

3.2. Dynamics Analysis of Cadmium Adsorption by FGS

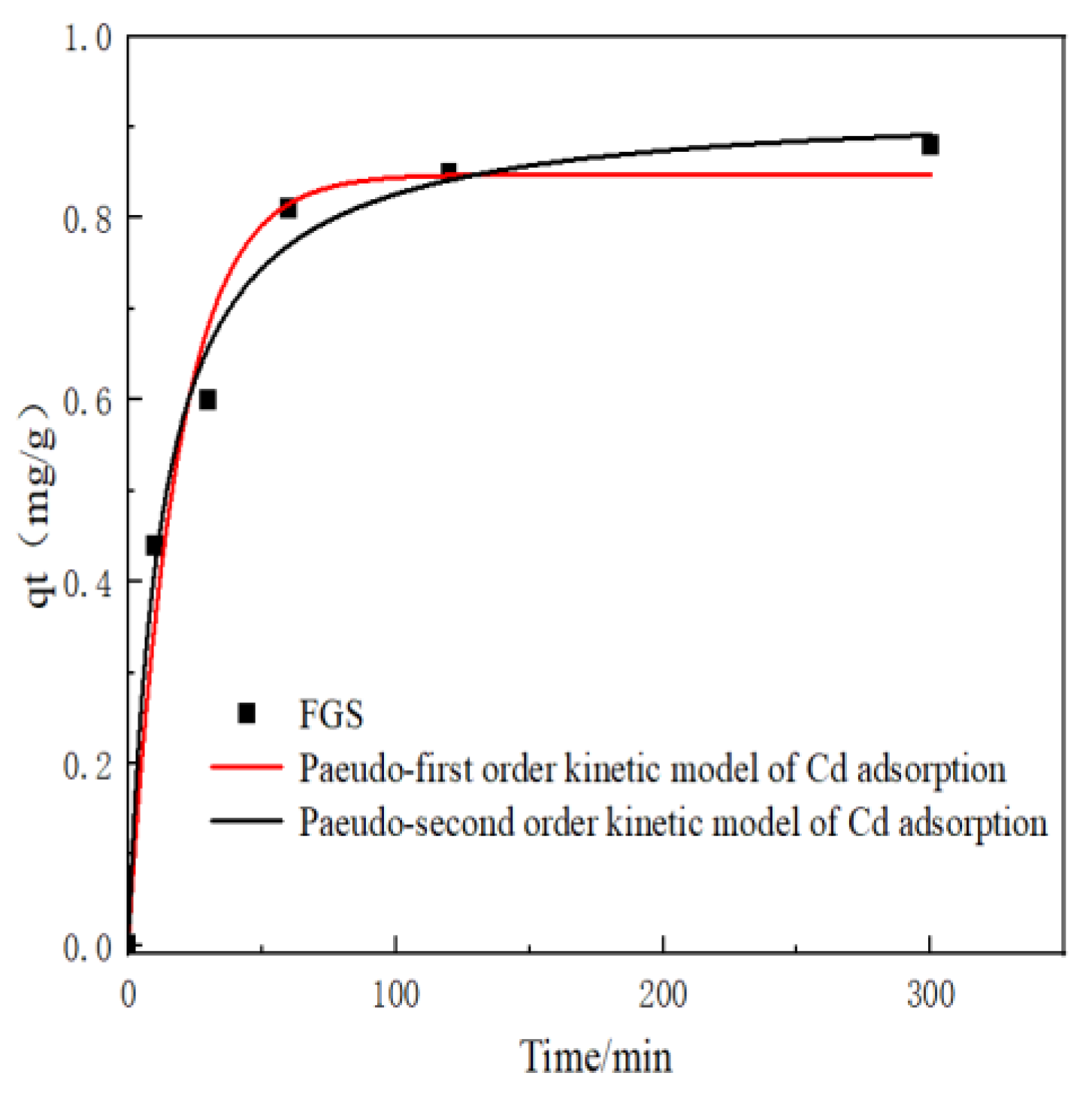

The adsorption kinetics of Cd²⁺ onto FGS were evaluated using pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second-order models (

Figure 2):

The adsorption capacity increased rapidly during initial stages and gradually approached equilibrium, indicating progressive saturation of active sites. Maximum Cd adsorption (0.88 mg/g) was achieved at 300 min. Kinetic fitting demonstrated superior correlation with the pseudo-second-order model (higher R² value), yielding a calculated equilibrium adsorption capacity of 0.91 mg/g. (The concentration and adsorption capacity of cadmium solution in the adsorption test are shown in

Table A1 and A2 of

Appendix A)

3.3. Chemical Bond Changes After Adsorption of Cadmium by FGS

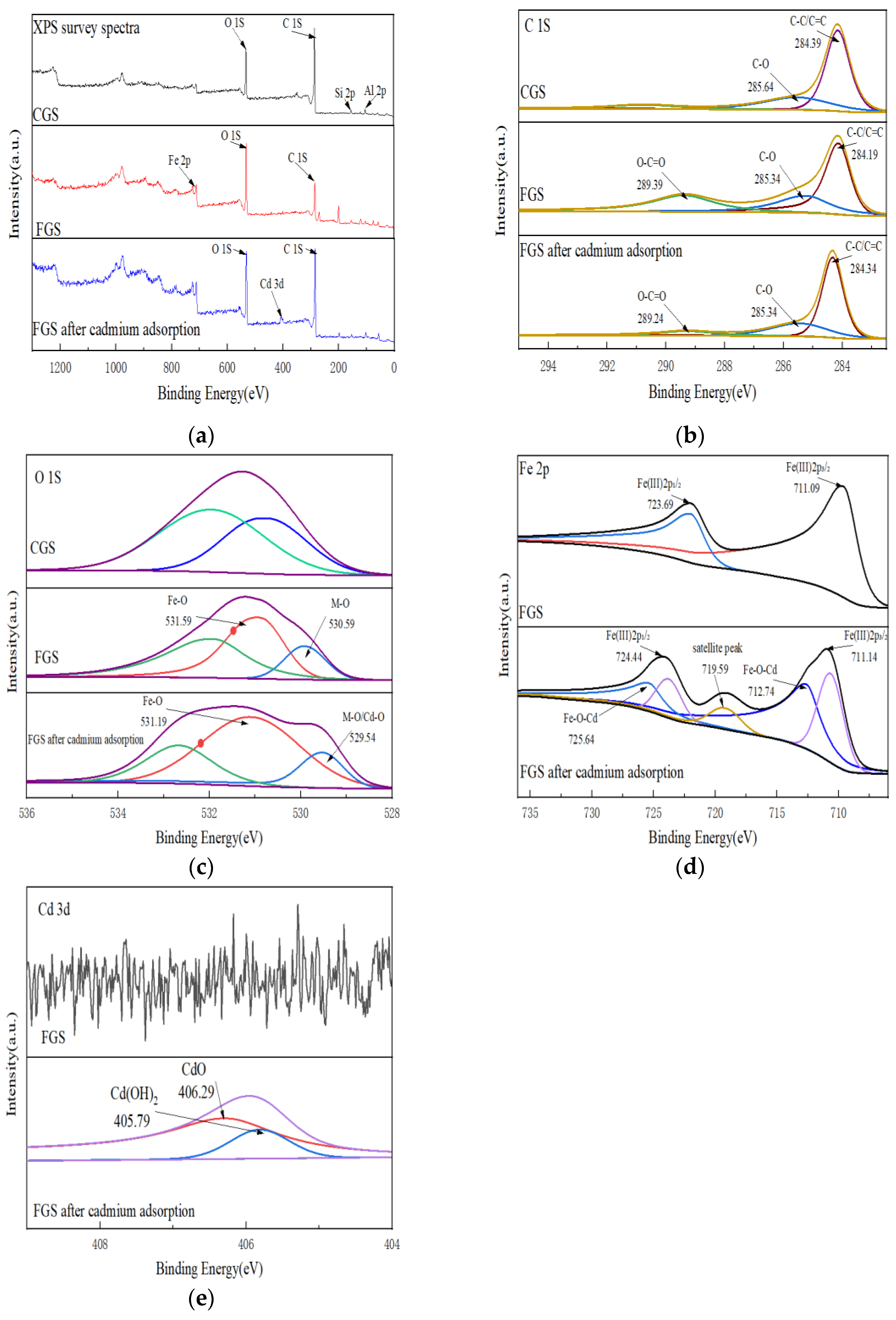

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) provided insights into elemental composition and bonding states:

Survey spectra (

Figure 3a) confirmed successful iron loading on FGS via the appearance of a Fe 2p peak at 711.09 eV. Cd adsorption was evidenced by a new Cd 3d peak at 406.69 eV.C 1s spectra (

Figure 3b) showed reduced peak intensities for C-O (285.34 eV) and O-C=O (289.39 eV) groups after Cd adsorption.O 1s spectra (

Figure 3c) indicated Fe-O bond formation after modification. Post-Cd adsorption, the M-O bond peak area (530.59 eV) increased significantly, while the Fe-O peak (531.59 eV) broadened.Fe 2p spectra (

Figure 3d) exhibited binding energy shifts at Fe 2p₃/₂ (711.09 eV) and Fe 2p₁/₂ (723.69 eV), along with a new peak at 719.59 eV after Cd uptake.Cd 3d spectra (

Figure 3e) displayed peaks at 406.29 eV and 405.79 eV, corresponding to CdO and Cd(OH)₂ species, respectively.

FTIR analysis (

Figure 1b) further supported these findings, showing substantial reductions in hydroxyl (3442 cm⁻¹) and Fe-O (544 cm⁻¹) peak intensities post-adsorption.

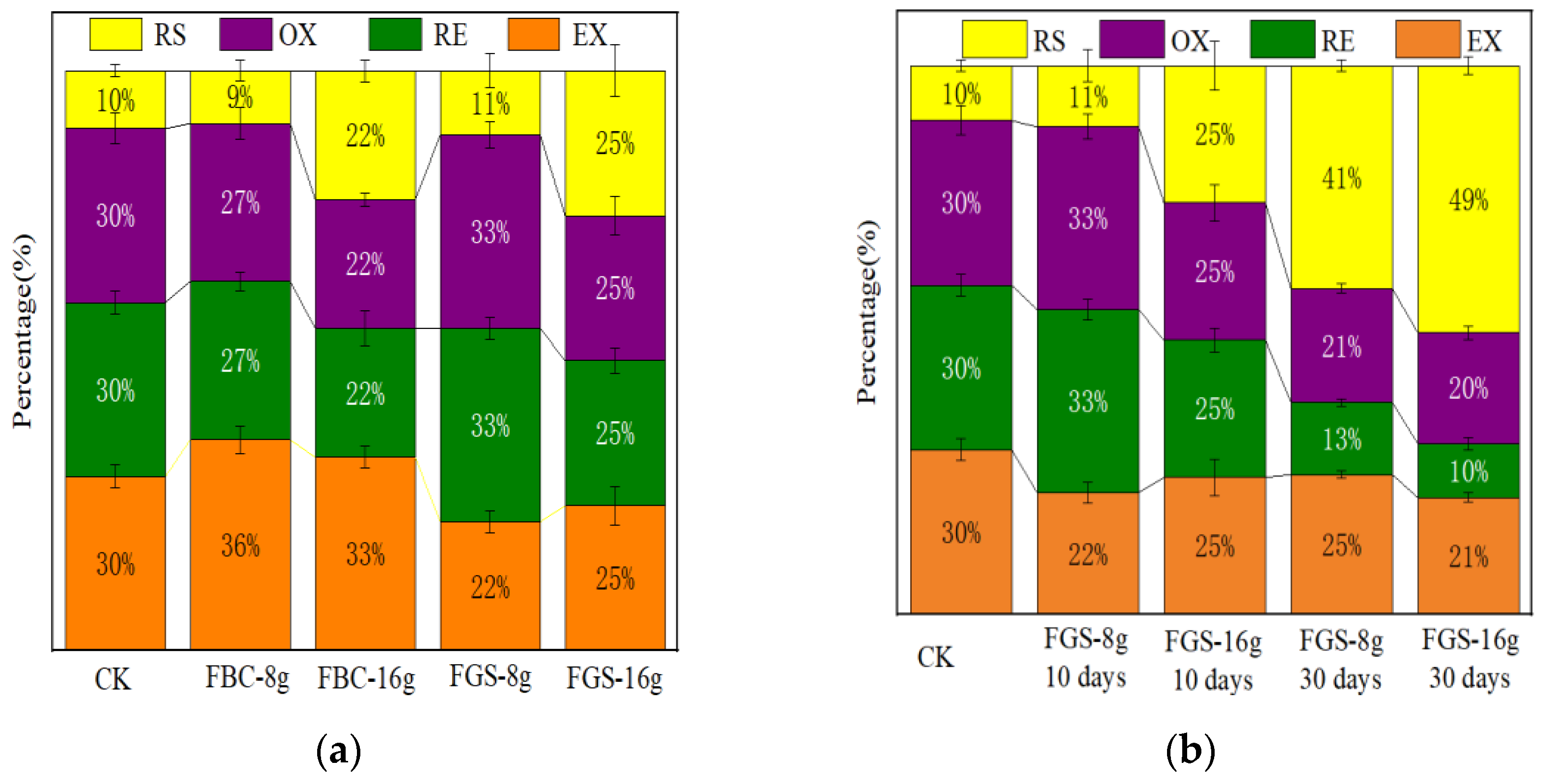

3.4. The Effect of FGS on Increasing the Proportion of Cadmium Residue in Passivation Experiment

The BCR method was applied to analyze the chemical forms of Cd in the mixed sam-

ples, which were divided into weak-acid-extractable Cd (EX), reducible Cd (RE), oxidizable Cd (OX), and residual Cd (RS).The passivation experiment results (

Figure 4a) showed that when 8g of FGS (accounting for 5% of the coal gangue mass) was added, the proportion of weakly acidic extracted cadmium decreased by 8% and the proportion of residual cadmium increased by 1%; When 16g of FGS (accounting for 10% of the coal gangue mass) is added, the proportion of weakly acidic extracted cadmium decreases by 5%, and the proportion of residual cadmium significantly increases by 15%. When the quality of the passivating agent added is the same, FGS has a greater effect on increasing the proportion of cadmium residue than FBC.

Figure 4b shows that the passivation effect is better after 30 days of FGS passivation than after 10 days, and the residual state ratio can be increased to 49% when the FGS addition amount is 16g. (The BCR test results of cadmium in passivation experiments are shown in

Table A3、

Table A4、

Table A5、

Table A6 of

Appendix A)

4. Discussion

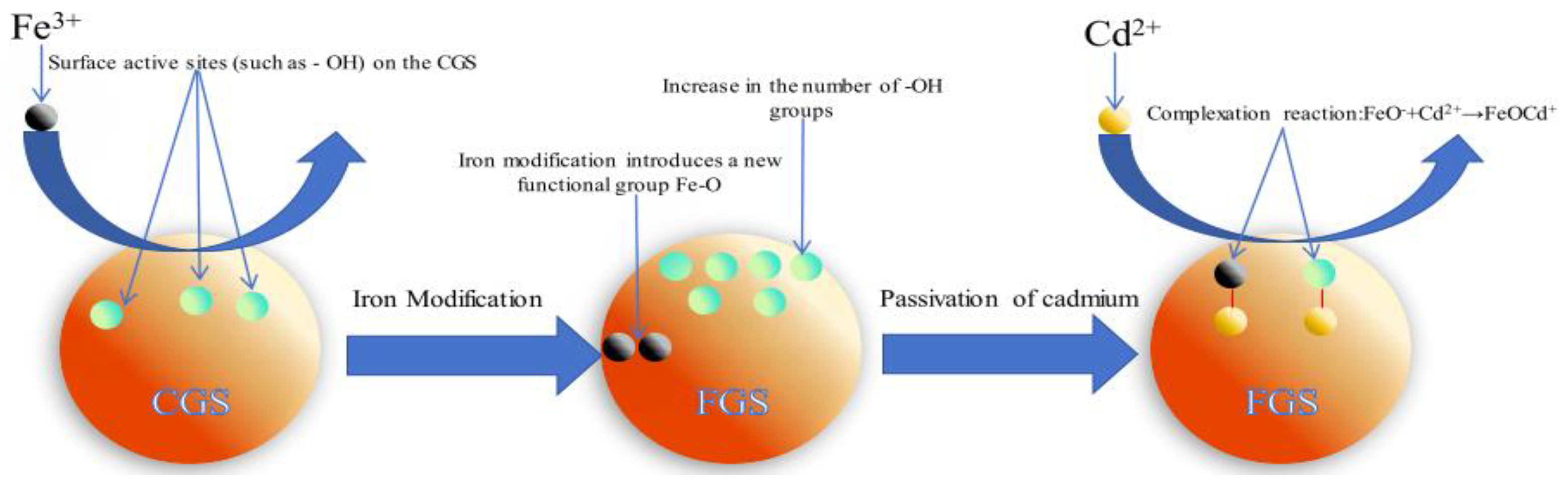

4.1. Mechanism of Enhanced Passivation Capacity via Iron Modification

The FTIR results (

Figure 1a) demonstrate that iron modification doubled the density of surface hydroxyl (-OH) groups on CGS. Alkaline pretreatment (2 mol/L NaOH) is recognized as the critical step facilitating this increase in hydroxyl functionality [

38,

39]. Enhanced hydroxyl density directly amplifies the material’s potential for metal complexation [

40]. Compared to the method reported by Zhou Chang-zhi et al. [

41], our FGS preparation protocol achieved more significant hydroxyl enhancement. This superiority arises from the fact that the FeCl

3 solution used in this study had a concentration of 1 mol/L, while the FeCl

2 solution used by Zhou Chang zhi et al. had a concentration of 0.5 mol/L.

Furthermore, the emergence of a distinct FTIR peak at 544 cm⁻¹ (

Figure 1a) confirms the successful introduction of Fe-O functional groups. These groups diversify the surface chemistry, providing additional sites for Cd complexation. Thus, iron modification synergistically enhances Cd passivation potential through both hydroxyl enrichment and Fe-O group incorporation.

Notably, the FGS synthesis method developed herein offers practical advantages over that of Zhou Chang-zhi et al. Their protocol required a costly tube furnace and prolonged (10 h) iron impregnation, whereas our method utilizes a simple 3-hour immersion at ambient conditions. This streamlined process reduces production costs while improving modification efficacy, facilitating large-scale application.

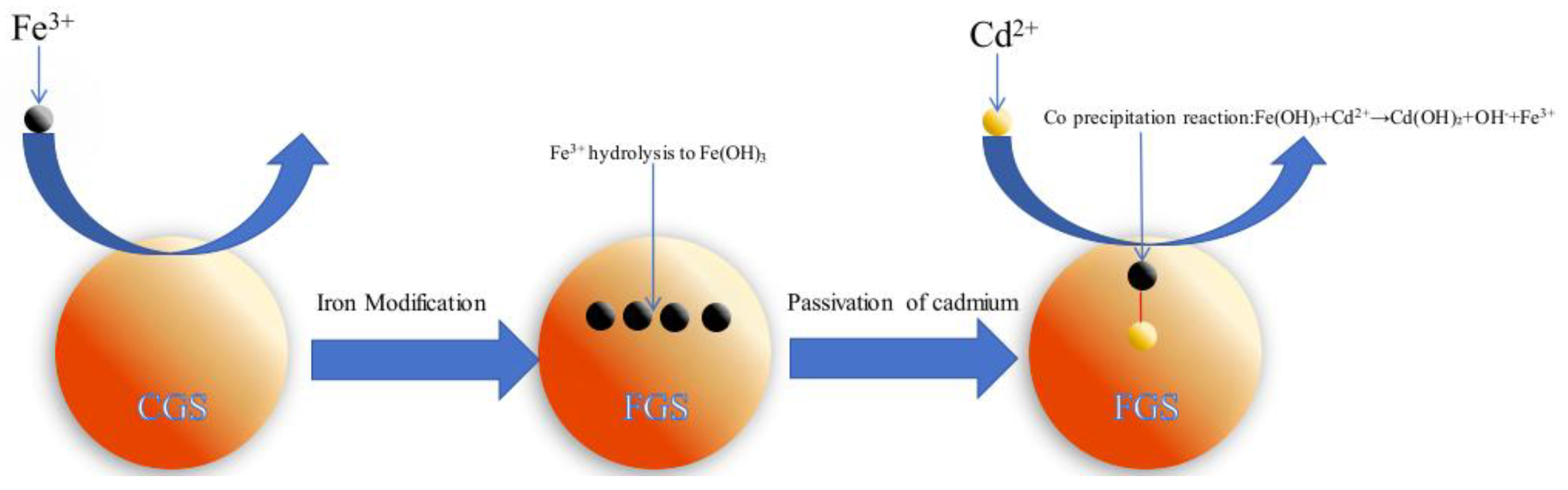

4.2. The Complexation and co Precipitation Mechanism of Cadmium Passivated by FGS

Adsorption kinetics analysis revealed that Cd uptake by FGS follows pseudo-second-order kinetics (

Figure 2), indicating chemisorption—specifically, surface complexation and/or coprecipitation—as the dominant passivation mechanism.

XPS and FTIR analyses provide mechanistic insights:

The increased M-O peak area and broadened Fe-O peak in O 1s spectra (

Figure 3c), coupled with binding energy shifts and new peak formation in Fe 2p spectra (

Figure 3d), suggest Cd²⁺ complexation with Fe-O groups to form Fe-O-Cd bonds [

42].

Reduced peak intensities for C-O and O-C=O in C 1s spectra (

Figure 3b) imply participation of oxygen-containing functional groups (notably carboxylates) in Cd complexation [

43].

Significant attenuation of hydroxyl (3442 cm⁻¹) and Fe-O (544 cm⁻¹) peaks in FTIR spectra (

Figure 1b) directly confirms the involvement of these groups in Cd adsorption.

Concurrently, the Cd 3d peak at 405.79 eV (

Figure 3e) indicates Cd(OH)₂ formation [

44]. This originates from coprecipitation between Cd²⁺ and Fe(OH)₃ colloids generated via hydrolysis of excess Fe³⁺ during modification.

Collectively, FGS passivates Cd through synergistic complexation and coprecipitation, governed by:

FeO-+Cd2+→FeOCd+ (1)

Fe(OH)₃+Cd2+→Cd(OH)₂+OH-+Fe3+ (2)

The mechanism diagrams of complexation reaction and co precipitation reaction are shown in the

Figure 5 and

Figure 6.

4.3. Efficacy and Advantages of FGS in Passivating Cadmium in Coal Gangue

The passivation experiment results (

Figure 4b) indicate that FGS can significantly increase the residual state proportion of cadmium (up to 39% increase) and reduce the weak acid extraction state proportion. The residual state is the most stable, migratory, and least biologically effective form of cadmium. Therefore, the application of FGS significantly reduces the environmental risks and bioavailability of cadmium.

It is worth noting that the FGS prepared in this study exhibits unique advantages in increasing the proportion of cadmium residue. Compared with the iron modified gasification slag prepared by Hongliang Yin et al., the FGS in this study significantly increased the residual state ratio, while the iron modified gasification slag prepared by Hongliang Yin et al. did not increase the residual state ratio of cadmium in the passivation experiment [

45]. This is because this study treated the gasification slag with alkali, which increased the number of active sites on the surface of the gasification slag. Under high concentration iron salt modification conditions, Fe (OH)

3 colloids that can undergo co precipitation reaction with cadmium can be generated on the surface of CGS, which significantly enhances the ability of coal gasification slag to passivate cadmium.

From

Figure 4, it can be seen that with the increase of passivation time, the passivation effect of FGS on cadmium becomes better and better. On the 30th day, when the mass of passivator is 16g, the residual state proportion of cadmium is 49%, which is 39% higher than that without passivation. Therefore, the FGS prepared in this study can achieve long-term stable passivation of cadmium. Meanwhile, at the same addition amount, FGS has a better passivation effect on cadmium (especially residual state transformation) than iron modified biochar (FBC), indicating that the ability of iron modified coal gasification slag to passivate cadmium is better than that of iron modified biochar.

5. Conclusions

This study developed iron-modified coal gasification slag (FGS) through iron salt impregnation and investigated its mechanisms and efficacy in cadmium (Cd) passivation. Key findings are summarized as follows:

(1) Enhanced surface functionality:FTIR analysis demonstrated that iron modification doubled hydroxyl group density and introduced Fe-O functional groups on the CGS surface. XPS analysis confirmed that these groups participate in Cd complexation through Fe-O-Cd bond formation.

(2) Synergistic passivation mechanisms:Excess Fe³⁺ hydrolysis during modification generated Fe(OH)₃ colloids, which facilitated Cd²⁺ immobilization via coprecipitation as Cd(OH)₂. Concurrently, surface complexation between Cd²⁺ and functional groups (-OH, Fe-O, -COOH) contributed to adsorption.

(3) Superior field efficacy:In coal gangue passivation experiments, FGS uniquely increased the residual Cd fraction by 39 percentage points—significantly outperforming reference materials that showed no residual fraction enhancement. This transformation effectively reduced Cd mobility and bioavailability.

This study provides a new approach for the resource utilization of coal gasification slag. Iron-modified coal gasification slag combines the advantages of low cost and environmental compatibility, making it a potential material for in-situ remediation of cadmium-contaminated soil, with significant prospects for engineering applications.

6. Patents

This section is not mandatory but may be added if there are patents resulting from the work reported in this manuscript.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.W.; methodology, Z.W.; validation, Z.W.; formal analysis, Z.W.; investigation, Z.W.; resources, Z.W.; data curation, Z.W.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.W.; writing—review and editing, Z.W.; visualization, Z.W.; supervision, Z.W.; project administration, Z.W. The author has read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author..

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ |

Directory of open access journals |

| CGS |

coal gasification slag |

| FGS |

iron-modified coal gasification slag |

| FBC |

iron-modified biochar |

| FTIR |

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| XPS |

X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy |

| BCR |

Community Bureau of Reference |

| ICP-OES |

Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry |

| ICP-MS |

Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry |

| EX |

weak-acid-extractable Cd (F1) |

| RE |

reducible Cd (F2) |

| OX |

oxidizable Cd (F3) |

| RS |

residual Cd (F4) |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Table A1.

Concentration of cadmium solution in FGS adsorption test.

Table A1.

Concentration of cadmium solution in FGS adsorption test.

| 10min |

30min |

60min |

120min |

300min |

| 19.12 |

18.80 |

18.38 |

18.30 |

18.24 |

Appendix A.2

Table A2.

Adsorption capacity of cadmium.

Table A2.

Adsorption capacity of cadmium.

| 10min (mg/g) |

30min (mg/g) |

60min (mg/g) |

120min (mg/g) |

300min (mg/g) |

| 0.44 |

0.6 |

0.81 |

0.85 |

0.88 |

Appendix A.3

Table A3.

Test results of BCR forms of cadmium in coal gangue.

Table A3.

Test results of BCR forms of cadmium in coal gangue.

|

weak-acid-extractable Cd (mg/kg) |

reducible Cd (mg/kg) |

oxidizable Cd (mg/kg) |

residual Cd (mg/kg) |

| 0.03±0.0020 |

0.03±0.0020 |

0.03±0.0030 |

0.01±0.0010 |

Appendix A.4

Table A4.

BCR test results after 10 days of FBC passivation of coal gangue.

Table A4.

BCR test results after 10 days of FBC passivation of coal gangue.

| FBC addition amount (g) |

weak-acid-extractable Cd (mg/kg) |

reducible Cd (mg/kg) |

oxidizable Cd (mg/kg) |

residual Cd (mg/kg) |

| 8 |

0.04±0.0027 |

0.03±0.0017 |

0.03±0.0030 |

0.01±0.0020 |

| 16 |

0.03±0.0017 |

0.02±0.0027 |

0.02±0.0010 |

0.02±0.0017 |

Appendix A.5

Table A5.

BCR test results after 10 days of FGS passivation of coal gangue.

Table A5.

BCR test results after 10 days of FGS passivation of coal gangue.

| FGS addition amount (g) |

weak-acid-extractable Cd (mg/kg)

|

reducible Cd (mg/kg)

|

oxidizable Cd (mg/kg)

|

residual Cd (mg/kg)

|

| 8 |

0.02±0.0017 |

0.03±0.0017 |

0.03±0.0020 |

0.01±0.0026 |

| 16 |

0.02±0.0027 |

0.02±0.0016 |

0.02±0.0027 |

0.02±0.0036 |

Appendix A.6

Table A6.

BCR test results after 30 days of FGS passivation of coal gangue.

Table A6.

BCR test results after 30 days of FGS passivation of coal gangue.

| FGS addition amount (g) |

weak-acid-extractable Cd (mg/kg)

|

reducible Cd (mg/kg)

|

oxidizable Cd (mg/kg)

|

residual Cd (mg/kg)

|

| 8 |

0.0064±0.0002 |

0.0033±0.0002 |

0.0052±0.0002 |

0.01±0.0003 |

| 16 |

0.0039±0.0001 |

0.0018±0.0002 |

0.0037±0.0002 |

0.0089±0.0002 |

References

- Qu, J.; Zhang, J.; Li, H; Li, S. A high value utilization process for coal gasification slag: preparation of high modulus sodium silicate by mechano-chemical synergistic activation. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 801, 149761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, Z.; Yang, C.; Dong, L.; Bao, W.; Wang, J.; Fan, P. Recent advances and conceptualizations in process intensification of coal gasification fine slag flotation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 304, 122394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Guo, Y.; Chen, L.; Jia, W.; Zhu, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, H.; Yao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, J. Multitudinous components recovery, heavy metals evolution and environmental impact of coal gasification slag: a review. Chemosphere 2023, 338, 139473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Wu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Miao, Z.; Niu, Y.; Guo, F.; Xi, Y. Preparation of hierarchically porous carbon ash composite material from fine slag of coal gasification and ash slag of biomass combustion for CO2 capture. Sep. Purif.Technol, 2024, 330, 125452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, B.; Deng, X.; Jiao, F.; Dong, B.; Fang, C.; Xing, B. Enrichment and utilization of residual carbon from coal gasification slag: a review. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2023, 171, 859–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Ding, L.; Guo, Q.; Gong, Y.; Yu, G.; Wang, F. Characterization, carbon-ash separation and resource utilization of coal gasification fine slag: A comprehensive review. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 398, 136554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu,X. ; Jin,Z.; Jing, Y.; Fan, P.; Qi, Z.; Bao, W.; Wang, J.; Yan, X.; Lv, P.; Dong, L. Review of the characteristics and graded utilisation of coal gasification slag. Chin.J. Chem. Eng. 2021, 35, 92–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Guo, X.; Pan, X.; Finkelman, R.; Wang, Y.; Huan, B.; Wang, S. Changes and distribution of modes of occurrence of seventeen potentially-hazardous trace elements during entrained flow gasification of coals from Ningdong, China. Minerals, 2018, 8, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang,W. Green energy and resources: advancing green and low-carbon development. Green. Energy Resour. 2023, 1, 100009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Feng, Y.; Yan, W. The current situation of comprehensive utilization of coal gangue in China. Adv. Mater. Res. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Liu, Z. Recycling utilization patterns of coal mining waste in China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2010, 54, 1331–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Sun, W.; Yang, Z. Numerical simulation of the dynamic change law of spontaneous combustion of coal gangue mountains. ACS Omega. 2022, 7, 37201–37211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.Q.; Peng, J.F.; Xu, D.J; Tian, J.J.; Liu, T.H.; Jiang, B.B.; Zhang, F.C. Leaching characteristics and pollution risk assessment of potentially harmful elements from coal gangue exposed to weathering for different periods of time. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Control Ser. 2023, 30, 63200–63214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Guo, Q.; Yang, Z.; Sun, G.; Y, W.; H, X. A land use-based spatial analysis method for human health risk assessment of heavy metals in soil and its application in Zhuzhou City, Hunan Province, China. J.Journal of Central South University. 2016, 23, 1915–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Zhao, P.; Ran, Q.; Li, W.; Wang, P.; Luo, Y.; Huang, C.; Yang, X.; Yin, J.; Zhang, R. Enhanced electrokinetic remediation for Cd-contaminated clay soil by addition of nitric acid, acetic acid, and EDTA: Effects on soil micro-ecology. Sci Total Environ. 2021, 772, 145029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunadasa, S.G.; Tighe, M.K.; Wilson, S.C. Arsenic and cadmium leaching in co-contaminated agronomic soil and the influence of high rainfall and amendments. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 316, 120591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.; Huang, S.; Ji, L.; Wu, Y.; Gao, J. Structure characteristics and gasification activity of residual carbon from entrained-flow coal gasification slag. J. Fuel, 2014,122. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Xia, T.; Jatowt, A.; Zhang, H.; Feng, X.; Shibasaki, R.; Kim, K.S. Context-aware heatstroke relief station placement and route optimization for large outdoor events. Int J. Health Geogr. 2022, 20, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, B.; Cheng, Z.; Wang, D.; Li, N. Investigation on the utilization of coal gasification slag in Portland cement: reaction kinetics and microstructure. Constr.Build. Mater. 2022, 323, 126587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Lian, X.; Zhai, X.; Li, X.; Guan, M.; Wang, X. Mechanical Properties of Ultra-High Performance Concrete with Coal Gasification Coarse Slag as River Sand Replacement. Materials. 2022, 15, 7552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, F.; Jiang, Y.; Wei, C. Potential of decarbonized coal gasification residues as the mineral admixture of cement-based material. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 269, 121259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Q.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Wei, C.; Xu, C. Synergistic utilization of blast furnace slag with other industrial solid wastes in cement and concrete industry: synergistic mechanisms, applications, and challenges. Green. Energy Resour. 2023, 1, 100012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yang, F.; Tao, Y. Removal of unburned carbon from fly ash using enhanced gravity separation and the comparison with froth flotation. Fuel. 2020, 259, 116282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Liu, D.; Tu, Y.; Jin, L.; Wang, H. Enrichment of residual carbon in entrained-flow gasification coal fine slag by ultrasonic flotation. Fuel. 2020, 278, 118195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Zhao, X.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, J. Fractal analysis and pore structure of gasification fine slag and its flotation residual carbon. Colloids Surf. A:Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2020, 585, 124148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Xiang, Y.; Gao, X. Humic acid coupled with coal gasification slag for enhancing the remediation of Cd-contaminated soil under alternated light/dark cycle. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2023, 30, 1276–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, Y.; Xiang, Y.; Jiao, Y.; Wang, L. Effect of sludge amino acid–modified magnetic coal gasification slag on plant growth, metal availability, and soil enzyme activity. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation, 2020, 75, 515–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, R.; Qiu, G.; Jia, W.; Guo, Y.; Guo, F.; Wu, J. Synthesis of Porous Material from Coal Gasification Fine Slag Residual Carbon and Its Application in Removal of Methylene Blue. Molecules. 2021, 26, 6116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Z.; Guo, Z.; Qiu, G.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, J. Synthesis of activated carbon from high-ash coal gasification fine slag and their application to CO2 capture. J. CO2 Util. 2021, 50, 101585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zuo, J.; Zhang, J.; Qiu, F.; Wei, C.; Miao, S. Preparation of mesoporous coal gasification slag and applications in polypropylene resin reinforcement and deodorization. Powder Technol. 2021, 386, 437–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, N.J.; Matjie, R.H.; Slaghuis, J.H.; Heerden, J.H.P. Characterization of unburned carbon present in coarse gasification ash. Fuel. 2008, 87, 683–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zuo, J.; Ai, W.; Liu, S.; Zhu, D.; Zhang, J.; Wei, C. Preparation of a new high-efficiency resin deodorant from coal gasification fine slag and its application in the removal of volatile organic compounds in polypropylene composites. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 384, 121347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Chen, X.; Ai, W.; Wei, C. A new method to prepare mesoporous silica from coal gasification fine slag and its application in methylene blue adsorption. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 212, 1062–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Xiang, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, X. Effects of sewage sludge modified by coal gasification slag and electron beam irradiation on the growth of Alhagi sparsifolia Shap. and transfer of heavy metals. Environ Sci Pollut R. 2018, 25, 11636–11645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, L.; Meng, J.; Liu, X.; Xu, Z.; Wang, Fan. ; Brookes, P. Zeolite-supported nanoscale zero-valent iron: New findings on simultaneous adsorption of Cd(II), Pb(II), and As(III) in aqueous solution and soil. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018, 344, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Yang, L.; Wang, C.Q.; Zhang, Q.p.; Liu, Q.C.; Li, Y.D.; Li, Y.D.; Xiao, R. Rui Xiao,Adsorption of Cd(II) from aqueous solutions by rape straw biochar derived from different modification processes. Chemosphere 2017, 175, 332–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, S.; Chang,J. ; Liu, M. Study on Adsorption Kinetics of HCl on the Surface of Ethanol-modified Calcium Adsorbent. Power Equipment. 2025, 39, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyu, H.O.; Chong, R.P. Preparation and characteristics of rice-straw-based porous carbons with high adsorption capacity. Fuel. 2022, 81, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basta, A.H.; Fierro, V.; El-Saied, H.; Celzard, A. 2-Steps KOH activation of rice straw: An efficient method for preparing high-performance activated carbons. Bioresour. Technol. 2009, 100, 3941–3947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regmi, P.; Garcia Moscoso, J.L.; Kumar, S.; Cao, X.; Mao, J.; Schafran, G. Removal of copper and cadmium from aqueous solution using switchgrass biochar produced via hydrothermal carbonization process. J. Environ. Manag. 2012, 109, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Wang, Q.; Zhu, F.; Sun, J.; Yin, H.; Hou, H.; Wang, J. Preparation and performance of a coal gasification slag-based composite for simultaneous immobilization of Cd and As. J. Cent. South Univ. 2024, 31, 1331–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Qi,F. ; Zhang, L.; Zhang, P.; Li, Q. Enhanced Cd adsorption by red mud modified bean-worm skin biochars in weakly alkali environment. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 297, 121533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, F.; Zhang, S.; Sun, Y.; Cheng, K.; Li, J.; Daniel, C.W.T. Fabrication and characterization of hydrophilic corn stalk biochar-supported nanoscale zero-valent iron composites for efficient metal removal. Bioresource Technology, 2018, 265, 490–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Wang, J.; Wang, Q.; Leng, Z.; Geng, Y.; Sun, S.; Hou,H. Simultaneous adsorption of Cd and As by a novel coal gasification slag based composite: Characterization and application in soil remediation. Sci. Total. Environ. 2023, 882, 163374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, H.; Zhou, C.; Wang, J.; Yin, M.; Wu, Z.; Song, N.; Song, X.; Shangguan, Y.; Sun, Z.; Zong, Q.; et al. Fe-CGS Effectively Inhibits the Dynamic Migration and Transformation of Cadmium and Arsenic in Soil. Toxics 2024, 12, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).