3. Results and Discussion

Synthesis of 8,8’-O,O-[cobalt bis(1,2-dicarbollide)]phosphorothioate, [8,8'-μ-O

2P(O)SH-3,3'-[Co(1,2-C

2B

9H

10)

2]HDBU (

1) was performed in three steps as previously described [

15]. Briefly, first the cesium salt of metallacarborane complex, 3-cobalt bis(1,2-dicarbollide) was treated with concentrated sulfuric acid to form it’s B(8,8’)-dihydroxy-derivative [

22]. This was subsequently treated with freshly prepared tri(1H-imidazol-1-yl)phosphine to form (1H-imidazol-1yl)phosphoramidite of 8,8’-dihydroxy-3-cobalt bis(1,2-dicarbollide), which was hydrolyzed

in situ into the corresponding H-phosphonate [8,8'-μ-O

2P(O)H-3,3'-Co(1,2-C

2B

9H

10)

2]HNEt

3. The H-phosphonate was transformed into thiophosphate using an elementary sulfur in the presence of a strong organic base, DBU, providing thiophosphoric acid bridged between boron atoms at positions 8 and 8' of 3-cobalt bis(1,2-dicarbollide) [8,8'-μ-O

2P(O)SH-3,3'-[Co(1,2-C

2B

9H

10)

2]HDBU (

1). The pKa value for the thiophosphate group of compound

1 was found to be 2.04 ± 0.06. The measurements were performed on the Pion SiriusT3 instrument (Pion Inc. Ltd., Forest Row, UK) using the spectrometric technique (details not shown).

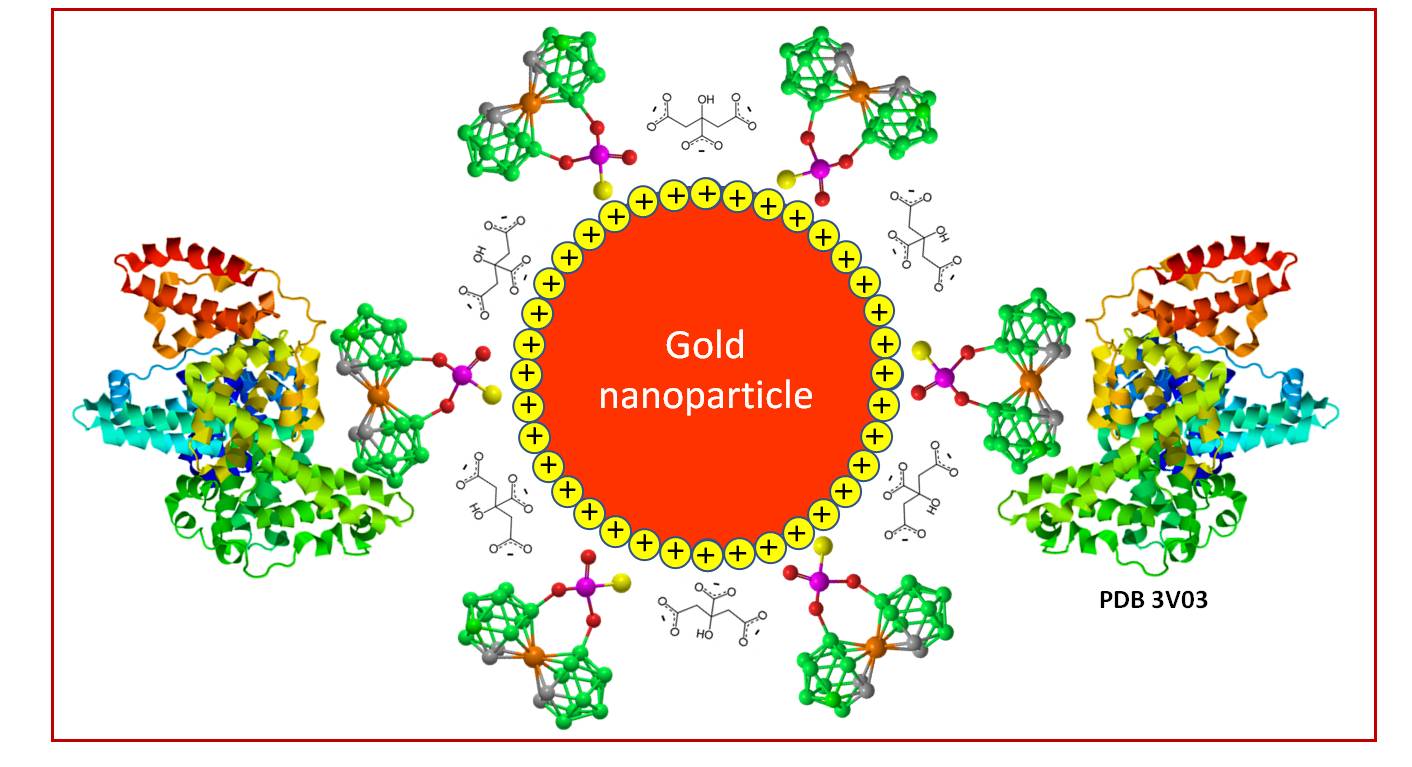

The preparation of AuNPs modified with

1 includes two main stages: 1) synthesis of AuNPs and 2) AuNPs functionalization with

1 (

Figure 1). In the first stage, sodium citrate was chosen as a reducing agent of Au(III) ions [

16,

17] for the preparation of gold nanoparticle colloid. According to the literature data [

17,

23,

24,

25], the mechanism of particle formation in the sodium citrate/HAuCl

4 system occurs through several stages: a) formation of nanoclusters less than 5 nm, b) formation of the network of nanoclusters forming gold nanowires, c) fragmentation of nanowires, and d) subsequent formation of individual AuNPs. These processes largely depend on the number of citrate carboxylate groups participating simultaneously in the reduction of metal ions, their binding to the surface of the resulting AuNPs, and the formation of a charge on their surface that stabilizes the nanoparticles due to electrostatic repulsion.

In the second stage, the AuNPs colloid (CAu = 3.00 × 10-4 M, CNaCitr = 6.00 × 10-4 M or 9.00 × 10-4 M) was treated with modifying component 1. Based on the obtained experimental data, the water was used as a solvent for preparation of 1 stock solution (0.25 mg/mL, 4.26 ×10-4 M) to avoid the aggregation of AuNPs, which occurred when organic solvents such as ethanol or DMSO were used as solvents for preparation of solutions of compound 1.

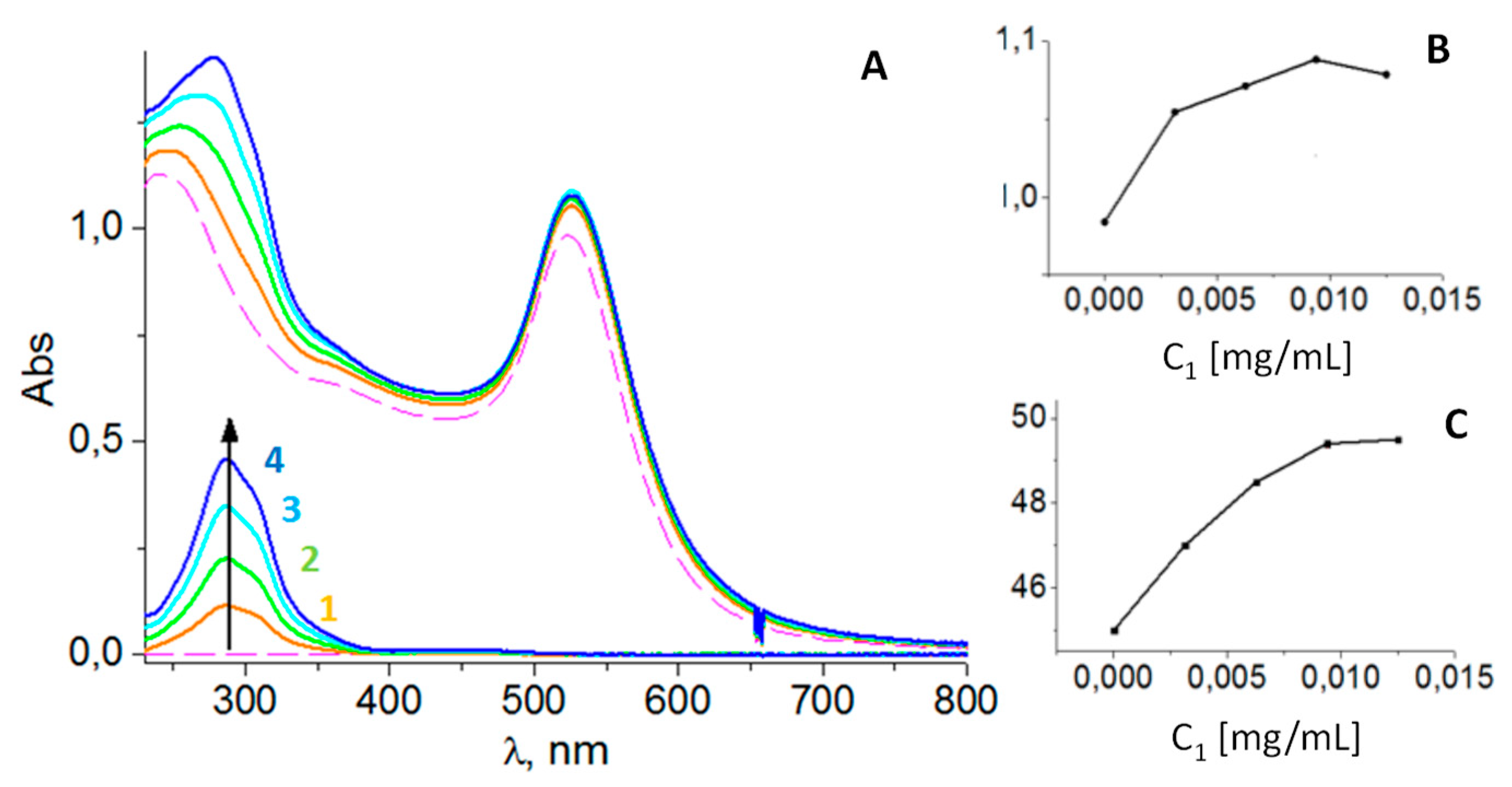

Optical properties. The detailed analysis of UV-Vis spectra of AuNPs and their functionalized conjugate AuNPs+

1 allowed us to identify changes that are specific to the binding of the modifier

1 to the AuNPs. The main change concerns the characteristic of the localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) band of gold nanoparticles as a result of the binding of functionalizing agent

1 to AuNPs. Firstly, the position of the band maximum in spectra measured in citrate solution (C

NaCitr = 9.00 × 10

-4 M) is red-shifted from λ

max = 520 nm for untreated AuNPs to λ

max = 524 nm for AuNPs+

1. Secondly, the intensity of the band maximum for AuNPs+

1 increased by approximately 7% compared to untreated AuNPs (

Figure 2A).

The changes in the intensity of the LSPR band were non-additive compared to the sum of the absorption of the control solution of

1 and the AuNPs colloid. Attached for comparison are the spectra of

1 at the same concentrations as used in the AuNPs functionalization process, showing additivity in the region of characteristic maximum for metallocarborane absorption at λ

max = 320 nm and complete transparency of

1 in the broad region beyond 400 nm, including the region of LSPR band maximum for gold. The adsorption process of

1 on the surface of AuNPs depends on the concentration of

1, which is illustrated by the concentration dependence shown in

Figure 2B.

As expected, the functionalization process, which involves the exchange of citrate molecules on the surface of AuNPs due to the formation of a stronger Au-S bond between the thiophosphate residue of 1 and the gold of the nanoparticle surface (

Figure 1), may promote the aggregation of AuNPs.

This process is illustrated by a broadening of the LSPR band upon increasing the concentration of 1 in the AuNPs colloid (

Figure 2C). A possible cause of this phenomenon is the known tendency of metallacarboranes to self-assembly as a result of the formation of dihydrogen bonds between metallacarborane molecules [

26,

27]. However, based on the data obtained from DLS and ELS measurements shown below, it seems that despite this, the colloids of AuNPs-

1 were more stable compared to the untreated AuNPs.

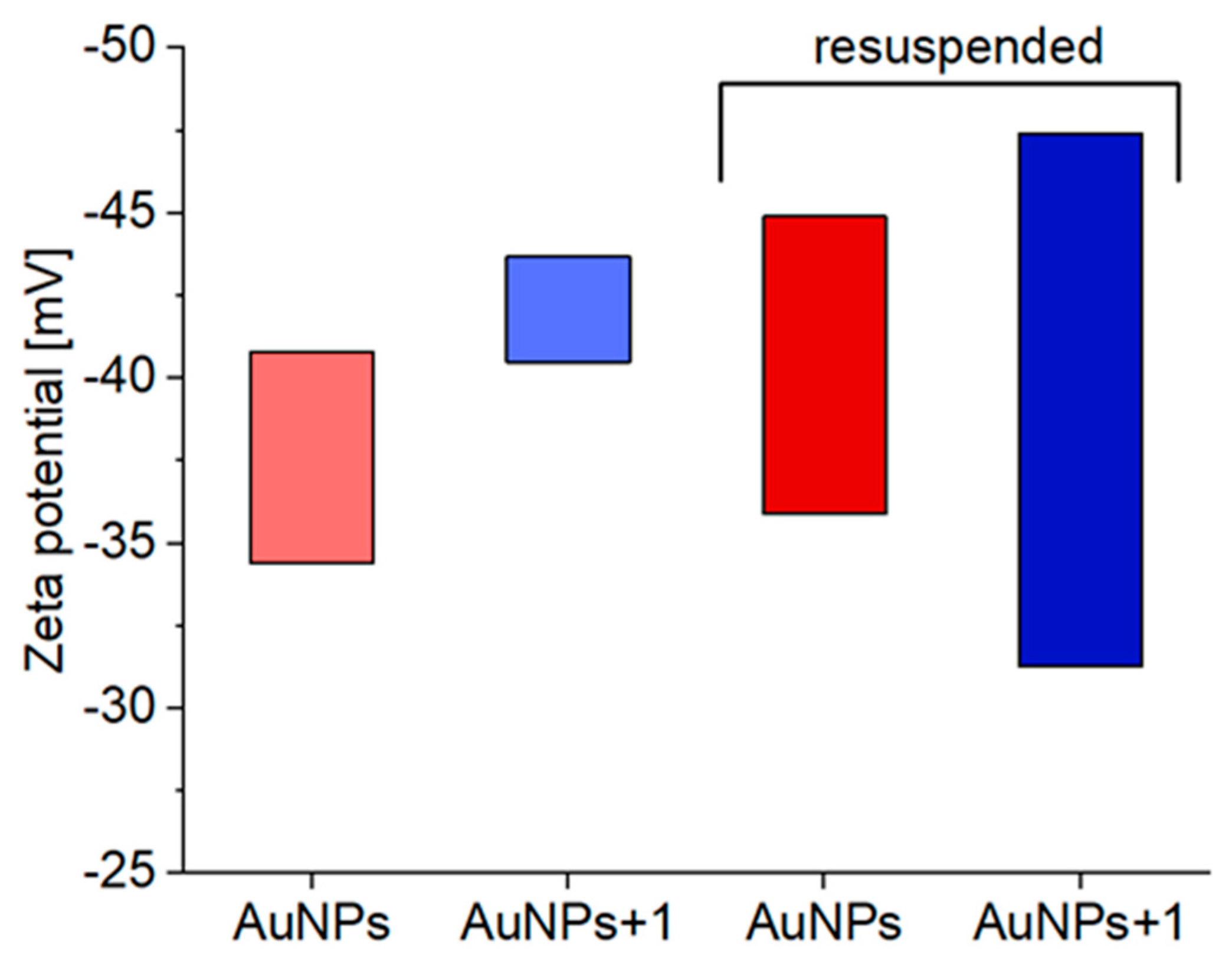

The AuNPs and AuNPs-1 zeta potential distribution. The data on zeta potentials of untreated and treated with

1 AuNPs colloids are shown in

Figure 3. In general, the negative surface charge of AuNPs treated with

1 was slightly increased compared to untreated AuNPs, with the average values of -42 mV and -37 mV, respectively, which is consistent with the above-mentioned increased stability of colloids of functionalized AuNPs+

1 preparations. At the same time, the zeta potential distribution of studied nanoparticles became less homogeneous upon centrifugation and subsequent resuspension of the AuNPs+

1 pellet.

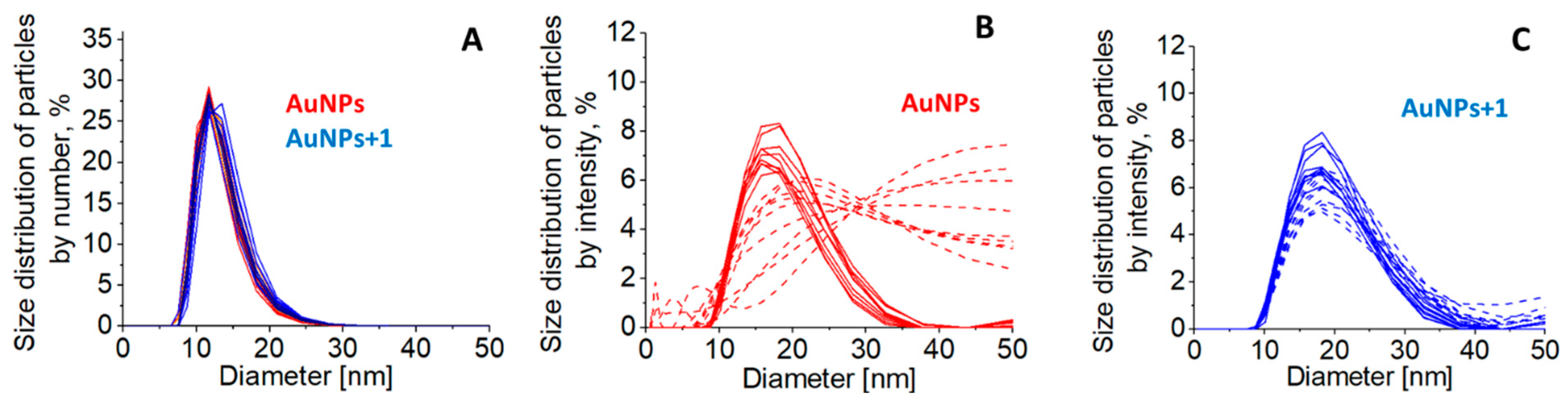

The AuNPs and AuNPs+1 size distribution. There are no obvious changes in the size of AuNPs upon functionalisation with

1 according to DLS data (

Figure 4). According to the distribution of nanoparticles by size (percentage of particles by quantity), the average size of the nanoparticles ranges from 10 nm to 16 nm, with a predominant population at 12 nm. According to the intensity basis, these values are 12-27 nm and 17 nm, respectively. Functionalized AuNPs were more stable compared to untreated, as the average size of particles in centrifuged and then resuspended systems remained generally unchanged (

Figure 4C, dashed) compared to the increased size of untreated AuNPs due to aggregation (

Figure 4B, dashed).

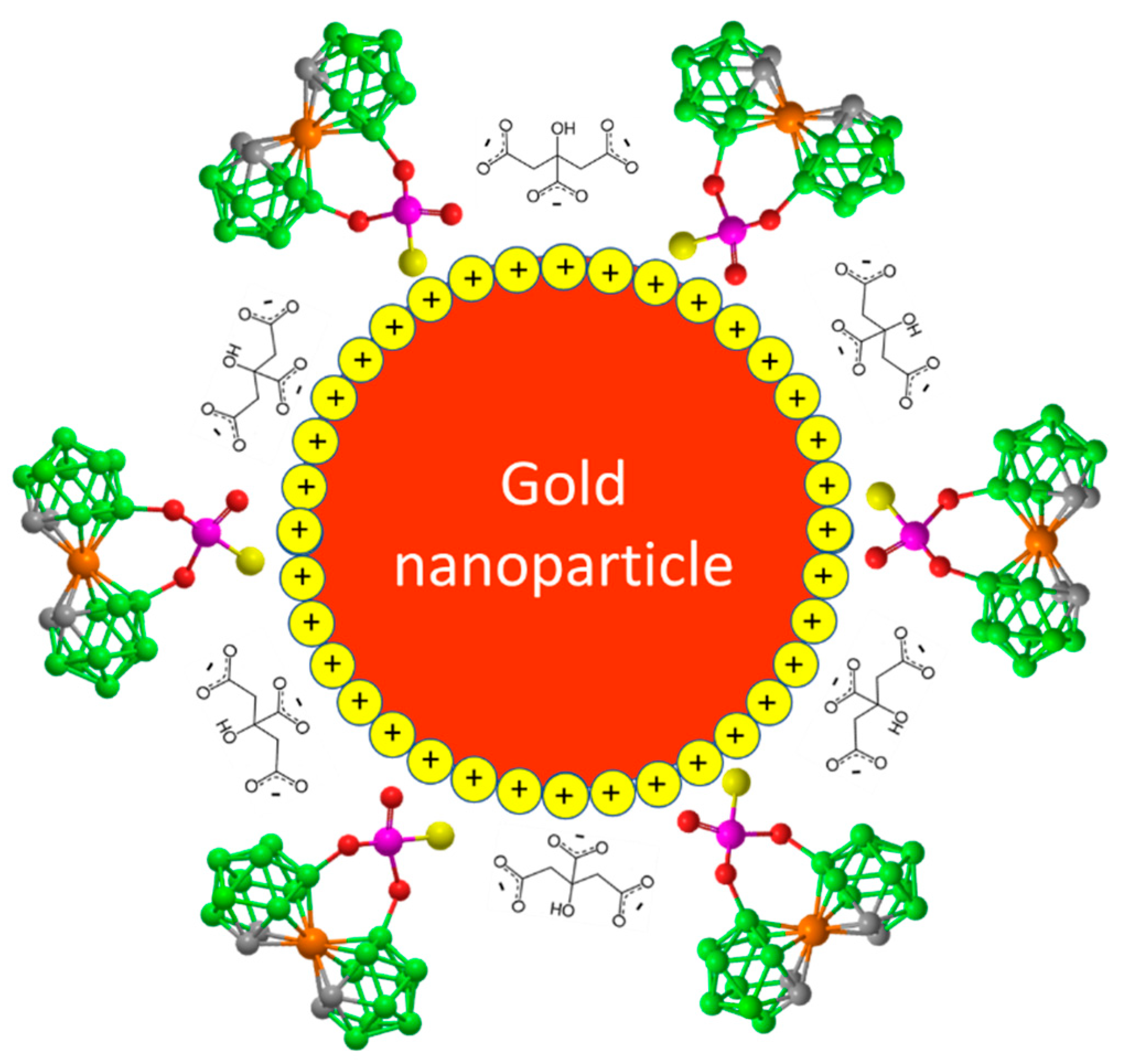

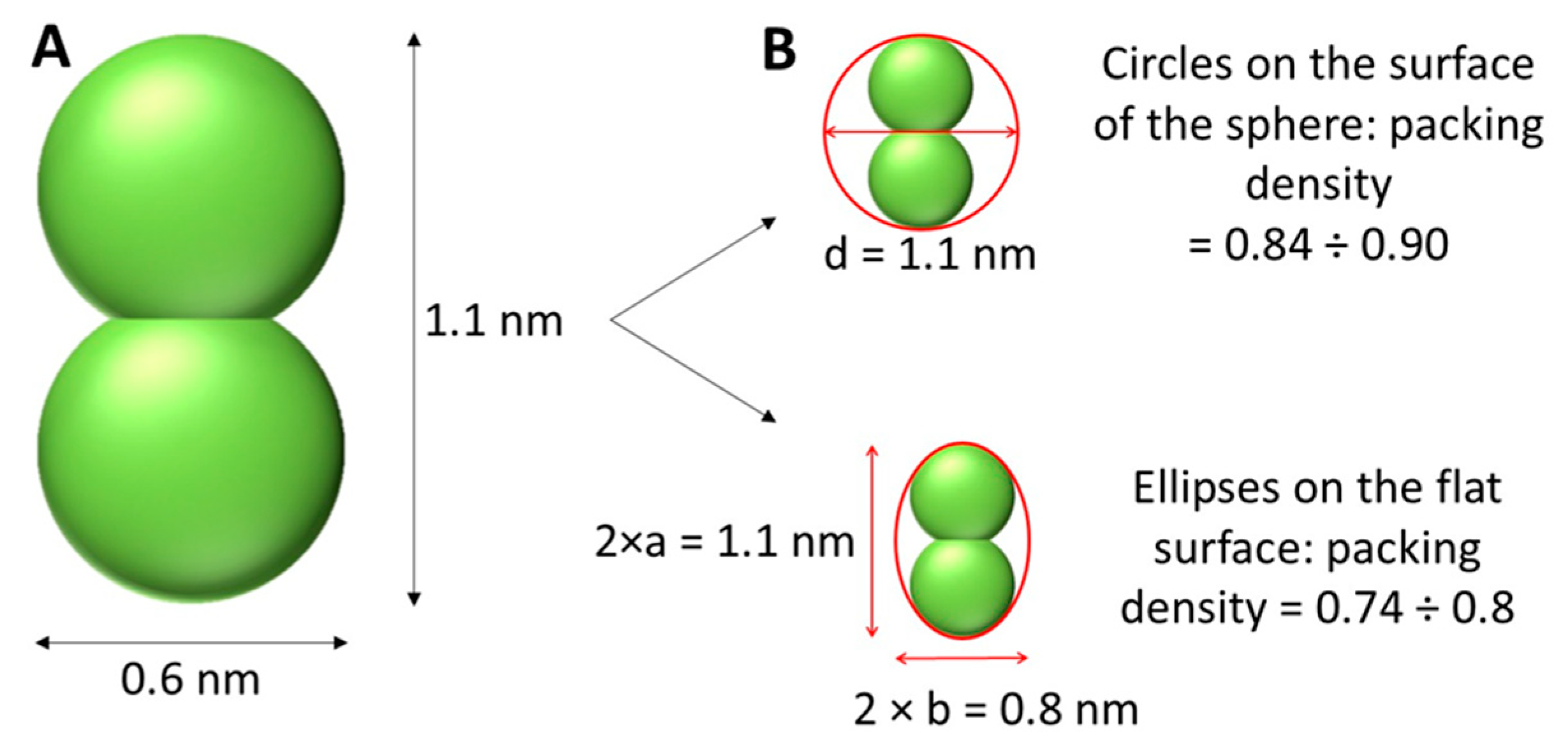

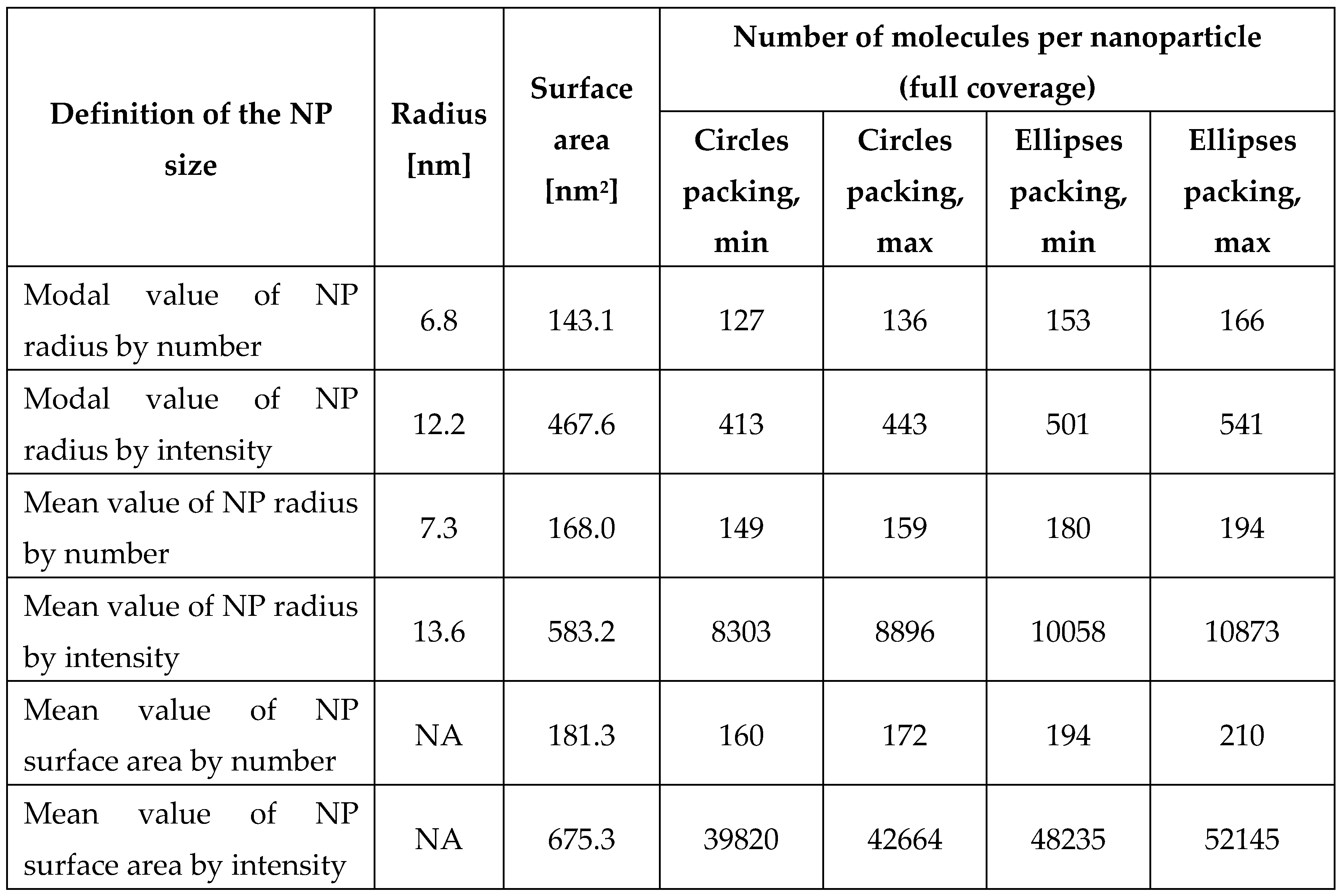

The coverage of the surface of AuNPs with 8,8’-O,O-[cobalt bis(1,2-dicarbollide)]phosphorothioate (1). For the estimation of surface coverage of AuNPs with

1, the structure of cobalt bis(1,2-dicarbollide, a metallacarborane core of

1, was adapted from [

19] and is shown in

Figure 5. It is supposed that the 2D projection is two crossed circles with a radius of 0.3 nm. For the theoretical calculations of coverage, different models were applied. Packing of flat shapes on some flat or curved surface is a mathematical and physical problem, which has been solved for various shapes and surfaces [28-30]. Two models were proposed here, as shown in

Figure 5.

In the framework of the "Circles packing” model, it is assumed that there is a circle, which is inscribed around the 2D-projection of the molecule (excircle), and the surface of the sphere (nanoparticle) is close-packed by these excircles. Clare and Kepert showed that the packing density for the optimal packing of circles on the sphere ranges from 0.84 to nearly 0.90 [

31]. The second model, "Ellipses packing," described the 2D projection of the molecule as an ellipse. Consequently, we need to find an ellipse inscribed around the 2D projection, and then pack these ellipses on the surface of the nanoparticle. For dense ellipse packing, the packing density is in the range from 0.74 to 0.80 [

32]. Hence, the number of molecules per one nanoparticle

is evaluated as follows:

where

is the area of the surface of the nanoparticle;

is the packing density (we use both the lowest and the highest values of the range); and

is the area of the shape escribed around the 2D projection of the molecule,

for circles packing with diameter

, and

for ellipse packing with

and

.

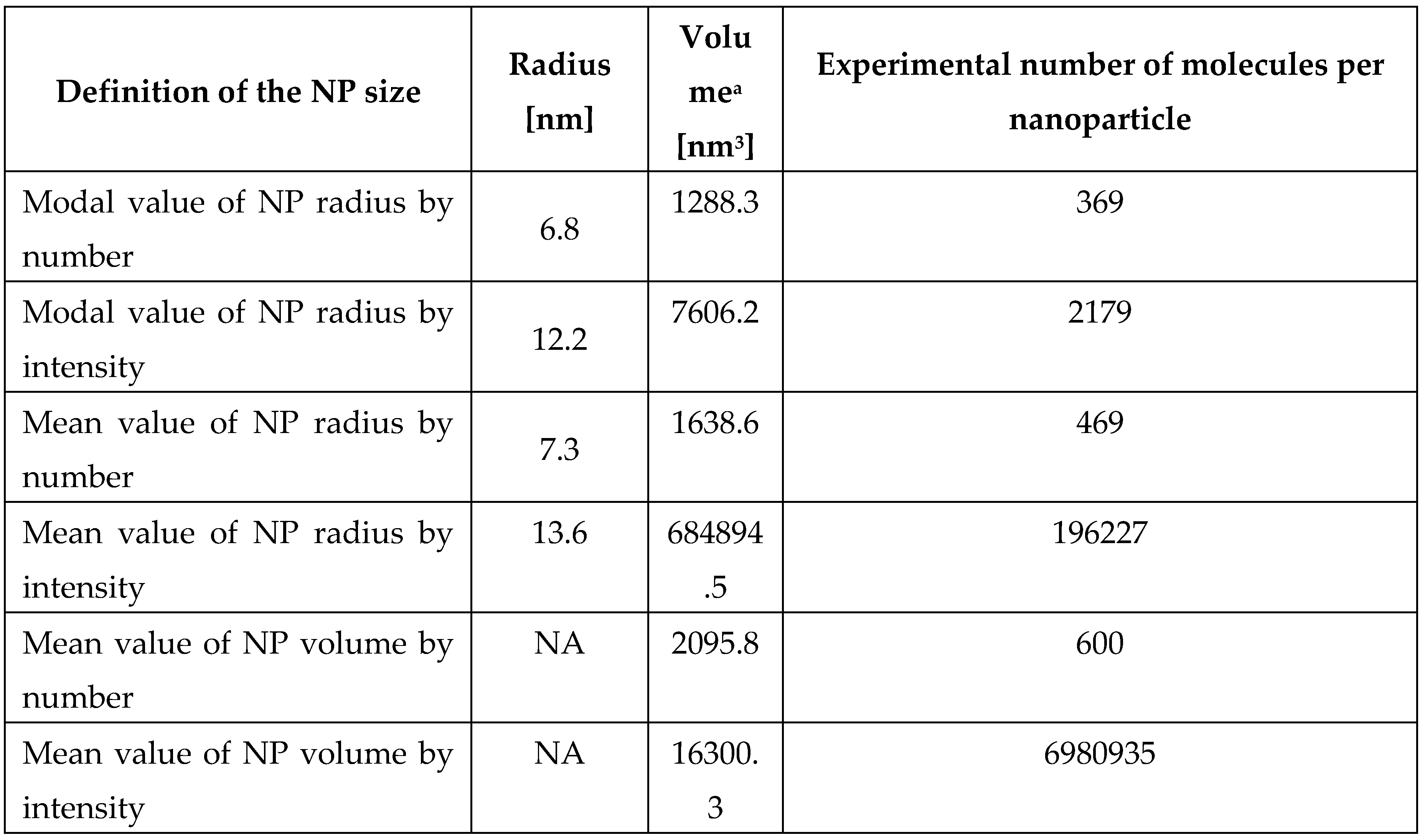

For the calculation of the radius of the nanoparticle, six approaches were used, which are shown in

Table 1. Both the modal and mean value of nanoparticle size were taken into consideration. The modal value is the value that is most frequently observed in DLS measurements. This means that the nanoparticles size is set to the one with the highest probability based on DLS signal intensity distribution. In this case, the surface area is calculated as

. Mean value of the NP radius is calculated as the sum of products of values of radius on their relative frequencies

, and the surface area then

. Mean value (averaged) of the NP surface area is calculated similarly, but for square radii

. Results of calculations are presented in

Table 1.

The experimental number of molecules 1 attached to one nanoparticle can be evaluated based on the intensity of 1 band in the absorption spectra of the supernatant of treated AuNPs colloid (

Figure S1). Taking into account the concentration of

1, C

1 = 2.13 × 10

-5 M (the concentration of saturation according to

Figure 2B, C), and the quantity of adsorbed molecules,

, the experimental number of molecules per nanoparticle is:

where

is Avogadro number, and

is the concentration of nanoparticles (numbers per liter), which may be calculated as follows:

where C

Au = 2.85 × 10

-4 M is molar concentration of gold, M

Au = 197 × 10

-3 kg/mol is molar mass of gold, ρ

Au = 19.3 × 10

-3 kg/m

3 is density of gold,

is the volume of one nanoparticle. As the difference in results using different approaches for calculating the surface area of a nanoparticle may differ by 2 orders of magnitude, we also evaluated the experimental value of adsorbed molecules using 6 approaches: for mode and mean values of radius, and for mean volume of a nanoparticle. Results are presented in

Table 2.

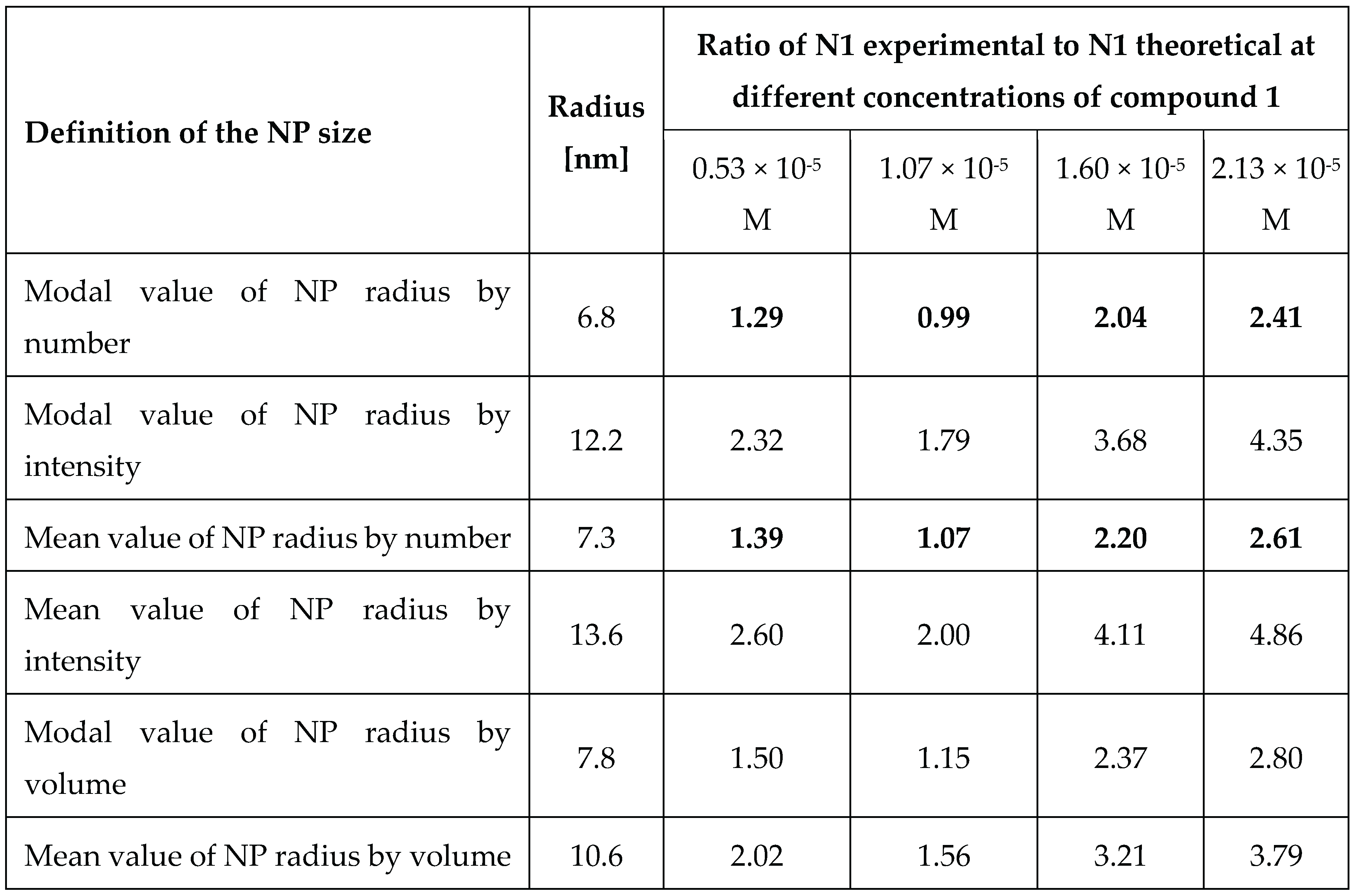

The surface roughness seems not to be high enough to influence the results [

33]. To compare theoretical and experimental results, it may be useful to calculate

instead. In this case, we calculate the ratio of the experimental value of the number of molecules attached to one nanoparticle to the theoretical value of the number of molecules needed for the full coverage of one nanoparticle. In this case, the ratio is proportional to the radius of the nanoparticle itself, and close to DLS measurements by number, and seems to be a better option to use due to the greater convergence of experimental estimates and theoretical values.

The results of these calculations are presented in

Table 3. Since the values for the ellipse packing fall within the middle range of values in

Table 1, and the actual type of packing is unknown, we chose to use a theoretical average value from the theory of ellipse packing

for our estimations.

Comparing the experimental results and theoretical evaluations, the following conclusion can be made. At low concentrations of compound

1 its molecules fully cover the surface of the nanoparticle in one layer. But for higher concentrations of modifier

1 the shell is formed in two layers of molecules, which is possible due to the tendency of

1 itself for self-assembling [

26,

27].

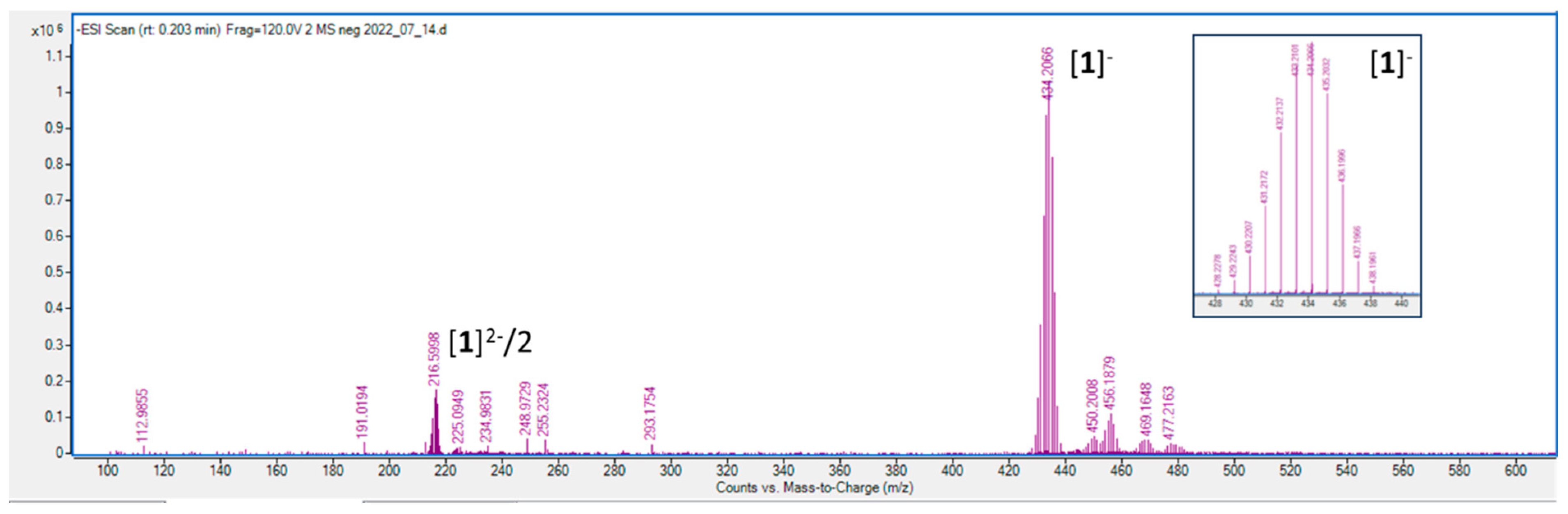

The ESI-MS measurements. The mass spectrometry was used to test the binding of 3-cobalt bis(1,2-dicarbollide) thiophosphate (

1) to a gold surface and the subsequent functionalization of AuNPs. The samples of AuNPs functionalized with

1 for mass spectrometry measurements were prepared by carefully washing several times with deionized water. The detachment of

1 from the gold surface of AuNPs was achieved

via reducing the gold ions Au(+1) with sodium borohydride [

18]. Untreated AuNPs used as a control were processed the same way. For a detailed procedure, please see the experimental.

As shown in

Figure 6, the mass spectrum of the analyte obtained from functionalized AuNPs recorded in negative mode unambiguously shows a diagnostic signal corresponding to a singly and doubly ionized modifier molecule

1 at 434.2066 m/z and 216.5998 m/z. Isotopic distribution within the molecular ion due to the natural abundance of 10B and 11B in natural elemental boron is characteristic of boron clusters (

Figure 6, inset). The presence of 216.5998 m/z ion is most probably an unprotonated double-charged 3-cobalt bis(1,2-dicarbollide) thiophosphate anion.

Binding of gold nanoparticle modified with compound 1 to BSA. The binding of BSA to AuNPs treated with 1 was estimated and compared to the BSA interaction with non-modified AuNPs. According to the literature, binding constants (Kb) and the stoichiometric ratio (n) of the components are usually estimated by analyzing the fluorescence emission of the protein in the 300-500 nm region.

Results obtained by other authors demonstrate that BSA exhibits strong and consistent binding affinity to AuNPs under different particle sizes and pH conditions, and linear Stern-Volmer plots suggest that dynamic quenching is the dominant mechanism. For example, the Ao and colleagues [

34] determined such parameters for the interaction of BSA with AuNPs (d = 26 nm) as

Kb = 1.19 ×10

10 М

-1 and

n = 1.46 at pH 7.4, respectively. As reported by Wangoo et al., the value of the binding constant for the BSA/AuNPs system was

Kb = 3.16×10

11 M

−1 at pH 7.0 (d = 40 nm) [

35]. In both cases, the Stern-Volmer plot was linear, which indicates a single type of quenching mechanism, most likely dynamic quenching. According to the data shown by Iosin et al. for spherical AuNPs (d = 18 nm) obtained

via the citrate method, the binding constant and stoichiometric ratio were

Kb = 2.34 × 10

11 M

-1 and

n = 1.37, respectively [

36].

The order of magnitude of the binding constant for the interaction of BSA with metallacarboranes alone is on the order of 10

5–10

6 M

-1 [

13]. Therefore, in the studied systems, a difference is expected between BSA attachment to the surface of untreated AuNPs and AuNPs coated with compound

1 – specifically, additional protein binding is likely to occur in the case of AuNPs-

1 due to inherent interaction with the metallacarborane.

Upon interaction with BSA, the position of the LSPR band maximum in the absorption spectra of gold shifted from 520 to 522 nm for untreated AuNPs and from 524 to 526 nm for

the 1-containing system, as shown for washed nanoparticles (

Figure S3A). Also, such interaction is accompanied by a slight but consistent increase in LSPR band intensity (

Figure S3B).

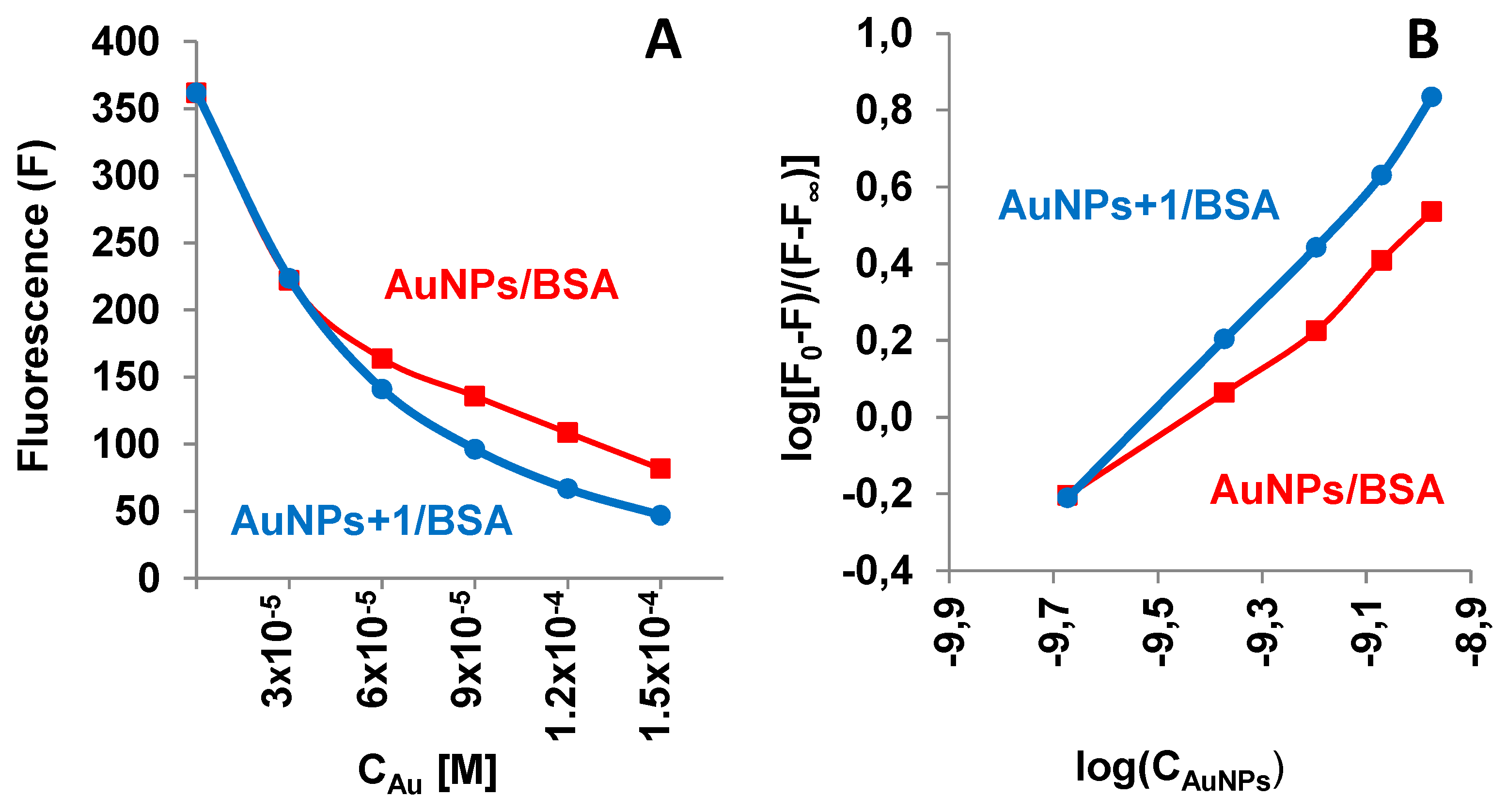

The aqueous solution of BSA exhibits a fluorescent signal in the range of 300-500 nm with an emission maximum at λ

em = 347 nm. It is known that AuNPs act as efficient energy acceptors in the process of fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET), and such a property was used for the detection of various analytes, in particular thiol-containing biomolecules [37-39]. Our results demonstrated that the BSA fluorescence is quenched upon the interaction with untreated AuNPs and AuNPs treated with compound

1. The intensity of the emission band of BSA at its maximum was decreased with increasing gold concentration (

Figure 7A).

The double-logarithmic plots of BSA fluorescence spectra after the addition of nanoparticles (

Figure 7B) allow estimation of the binding constants (

Kb) for both systems, on linear regression analysis of the plots (Supplementary Material, S3).

The

Kb value calculated for AuNPs/BSA and AuNPs-

1-BSA system, 2.84×10

9 M

-1 and 3.13×10

9 M

-1, respectively, indicated the BSA binding affinity to both types of nanoparticles

, with higher binding observed for AuNPs treated with compound

1. The increased BSA affinity for AuNPs functionalized with

1 may have a significant effect on the biological activity of this novel type of gold nanoparticles in comparison with untreated AuNPs. To define the difference in action of prepared nanosystems, a set of biological tests for the investigation of cytotoxicity and antiviral activity [

3] was also performed.

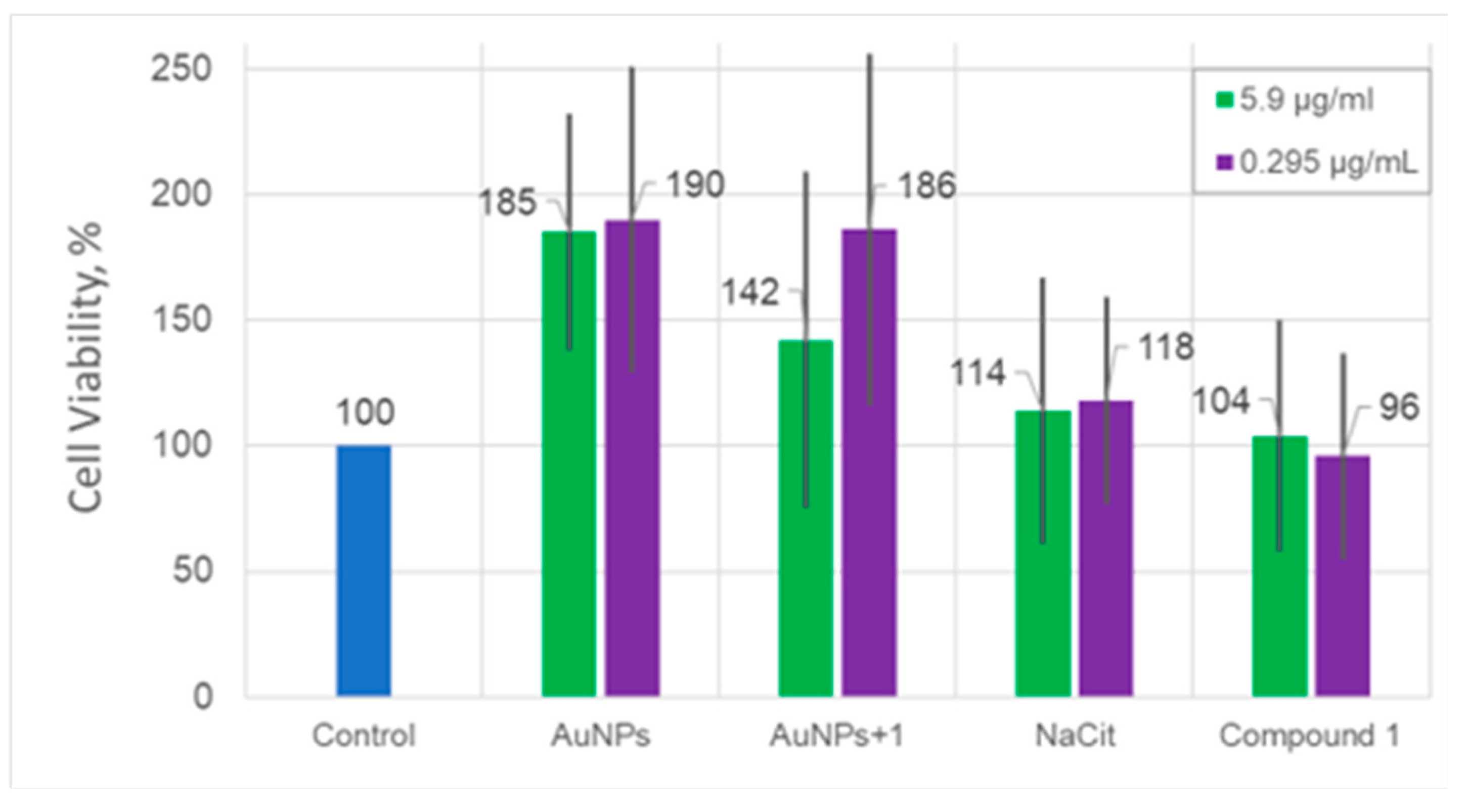

Cytotoxic activity of AuNPs and AuNPs+1. In the performed studies, no cytotoxicity of the tested nanoparticles, AuNPs neither AuNPs+1, was observed within the tested concentration range. On the contrary, their significant stimulating effect on Vero cell proliferation was observed. Suprasingly, the viability of Vero cells cultured with AuNPs or AuNPs+1 was almost two-fold higher in comparison to the viability of untreated cells (p = 0.01).

Figure 8.

Cytotoxicity of gold nanoparticles AuNPs and AUNPs+1, NaCit stabilizer used, and compound 1. Number of viable Vero cells in comparison to the untreated cell control, NaCit, and compound 1 after incubation for 48 h. The nanoparticles were studied at two different dilutions: 5.9 µg/mL and 0.295 µg/mL. Blue: control of the cell line used as a reference point; orange: cell viability after adding the solution with 5.9 μg/ml of the substance / NPs; green: cell viability after adding the solution with 0.295 μg/ml of the substance / NPs. Numbers above the bar are equal to the mean value of the cell concentration compared to the control in percent. The cell viability was measured using an MTT assay. The data are shown as means ± SD of three independent experiments.

Figure 8.

Cytotoxicity of gold nanoparticles AuNPs and AUNPs+1, NaCit stabilizer used, and compound 1. Number of viable Vero cells in comparison to the untreated cell control, NaCit, and compound 1 after incubation for 48 h. The nanoparticles were studied at two different dilutions: 5.9 µg/mL and 0.295 µg/mL. Blue: control of the cell line used as a reference point; orange: cell viability after adding the solution with 5.9 μg/ml of the substance / NPs; green: cell viability after adding the solution with 0.295 μg/ml of the substance / NPs. Numbers above the bar are equal to the mean value of the cell concentration compared to the control in percent. The cell viability was measured using an MTT assay. The data are shown as means ± SD of three independent experiments.

Washed nanoparticles, both AuNPs and AuNPs+

1 stimulate the growth of Vero cells in a concentration-dependent manner. It should be noted that the absorbance of light by the medium with AuNPs or AuNPs+

1 itself was subtracted from the absorbance of the cells with EMEM and AuNPs. Hence, we can be sure that these results reflect a proper number of cells. Moreover, NaCit and compound

1 demonstrated no effect on the viability of Vero cells (

p < 0.05). The promotion of cell proliferation by AuNPs has already been shown for MC3T3-E1 preosteoblastic cells derived from mouse calvaria [

40,

41]. It was stated that the size and concentration of nanoparticles are the key factors for this phenomenon [

40]. Moreover, the nonlinear, and more importantly, nonmonotonic dependence of the proliferation effect from the concentration of AuNPs was observed.

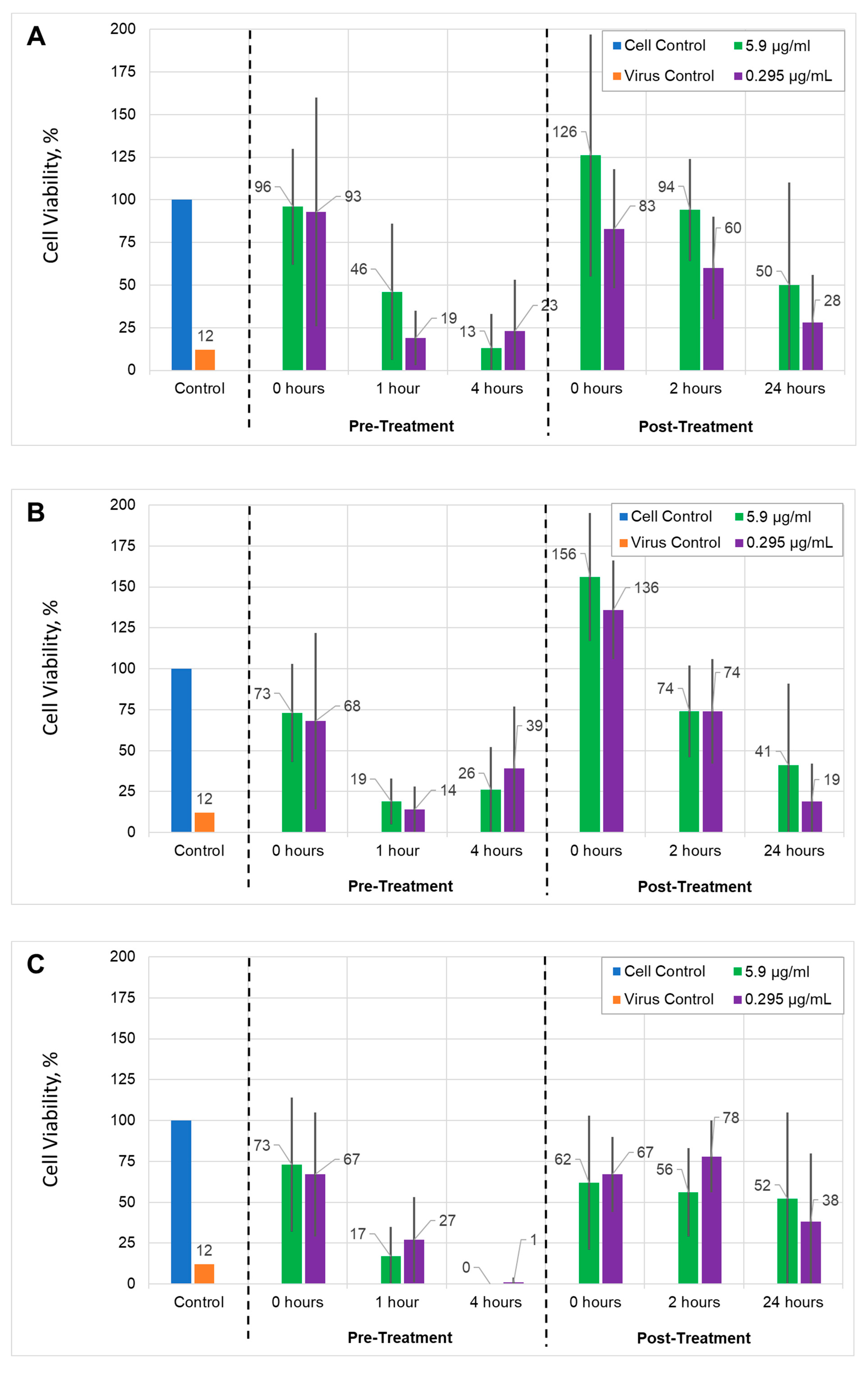

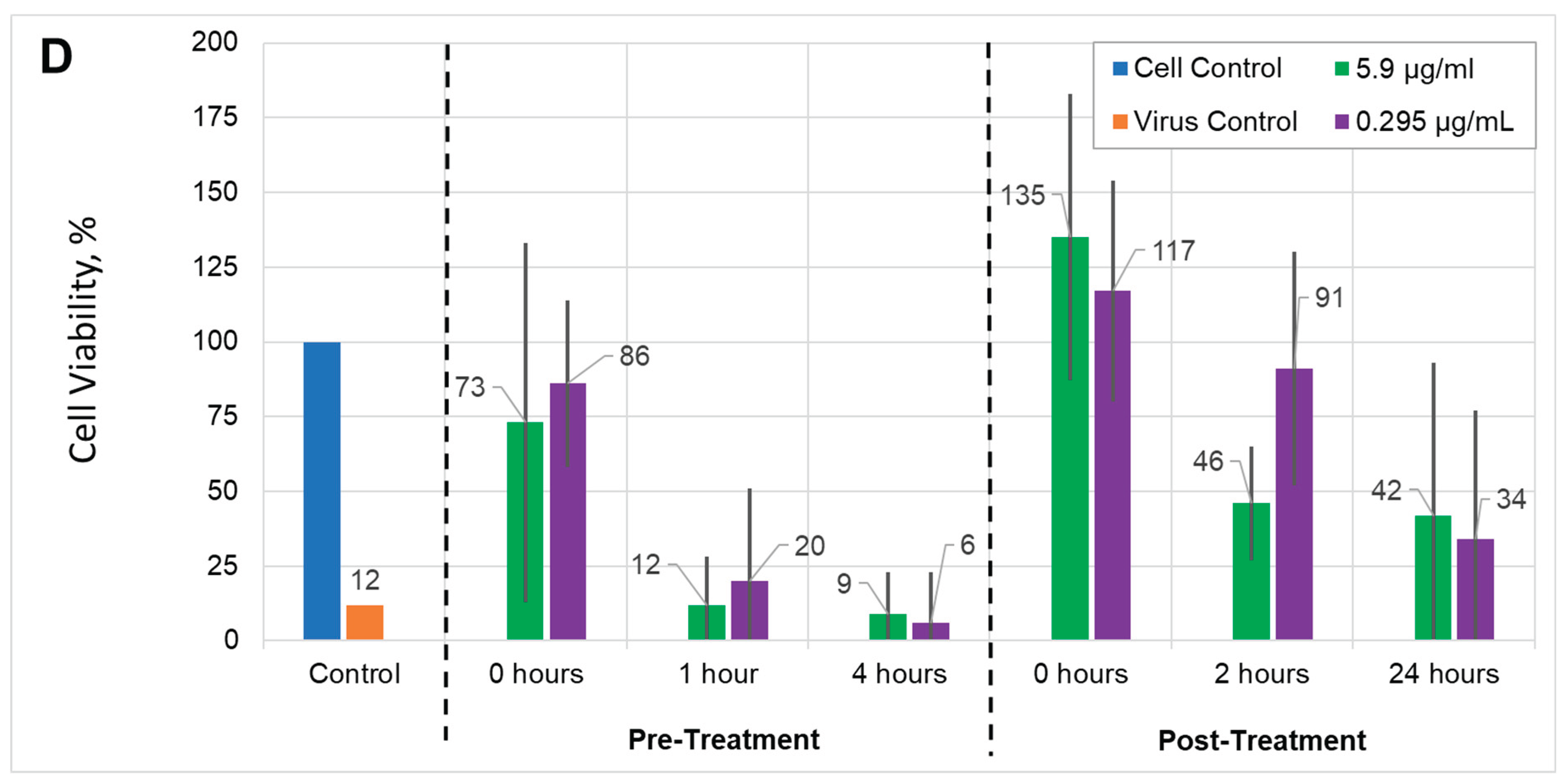

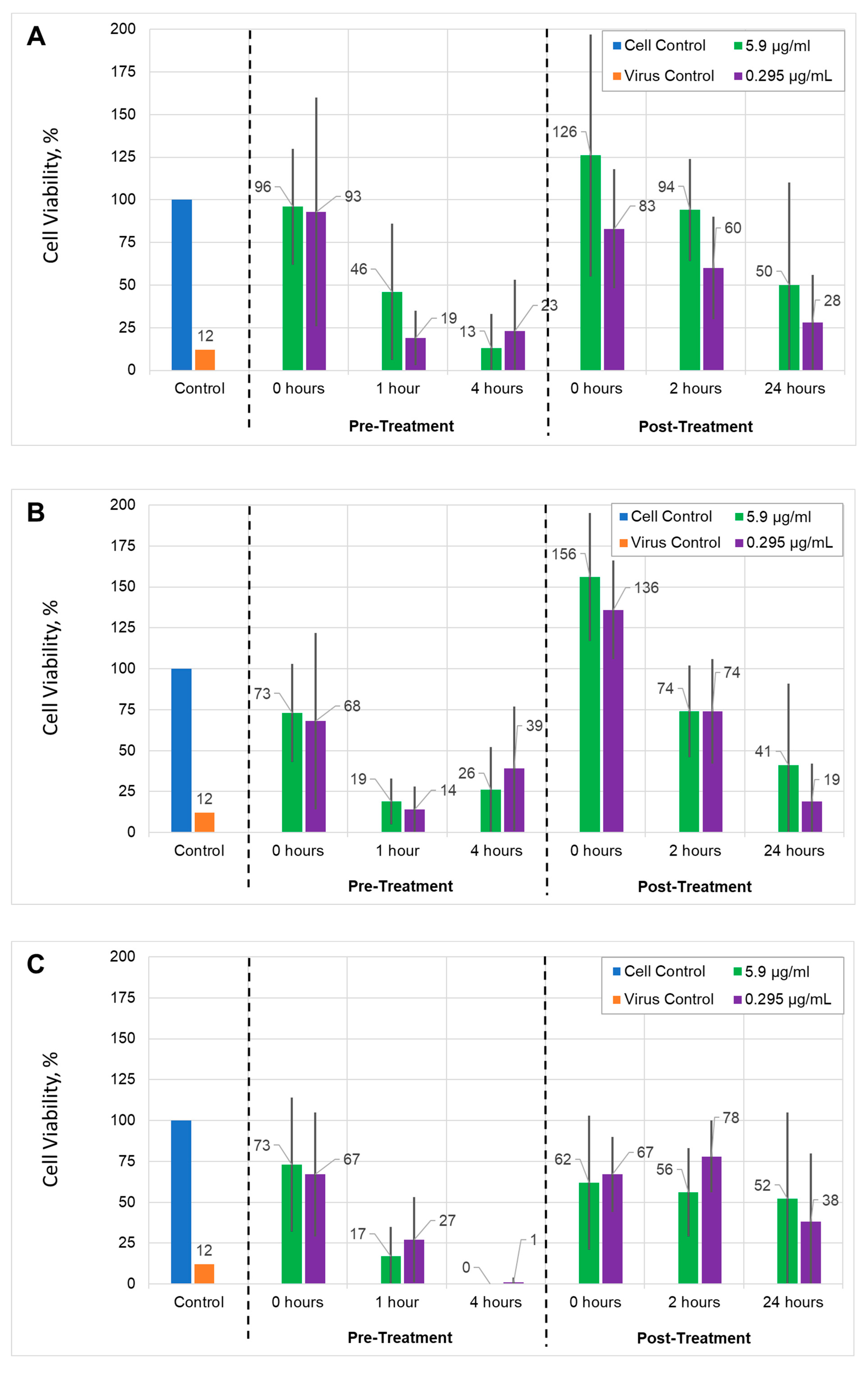

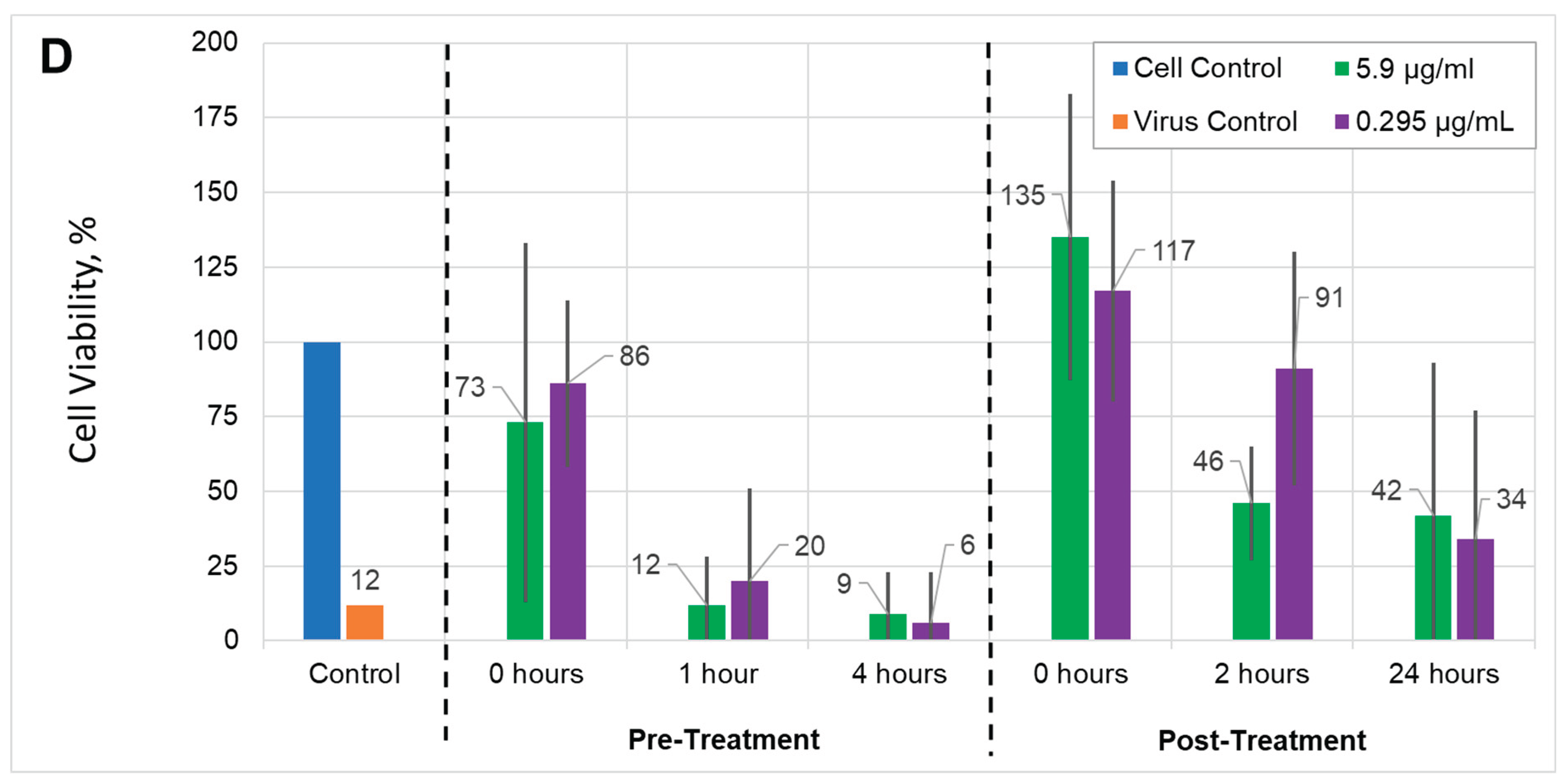

Antiviral activity. To assess the effect of AuNPs and AUNPs+

1 on the inhibition of HSV-1 replication, pre-treatment and post-treatment assays were used. The dose-dependent efficiency of AuNPs or AuNPs+

1 on viral titers released into cell-free culture supernatant was observed. Both AuNPs types demonstrated antiviral activity, but at different rates as well in pre-treatment as post-treatment assays. The highest antiviral activity in the pre-treatment assay was observed for 0 hours. We hypothesize that AuNPs may disturb the virus attachment to the cellular receptors and prevent entry to the cell or fusion with its membrane [

21]. Interestingly, at low concentration, the antiviral action of AuNPs+

1 after 24 hours post-treatment was higher than that for AuNPs (0.3 μg/mL), independent of the viral load. The respective cell viability was 38% for AuNPs+

1 vs. 28% for AuNPs (MOI = 0.001), and 34% for AuNPs+

1 vs. 19% for AuNPs (MOI = 0.002 ) (

Figure 9A–D). Similarly, after 2-hour post-treatment with low concentration, AuNPs+

1 showed higher antiviral activity than AuNPs (78% for AuNPs+

1 vs. 60% for AuNPs in lower MOI, and 94% for AuNPs+

1 vs. 74% for AuNPs in higher MOI conditions,

Figure 9A–D). Functionalizing of AuNPs with compound

1 appears to enhance the nanoparticles' antiviral activity against HSV-1 in Vero cells after long-term infection.

Figure 1.

Idealized image of a gold nanoparticle modified with 8,8’-O,O-[cobalt bis(1,2-dicarbollide)]phosphorothioate (1).

Figure 1.

Idealized image of a gold nanoparticle modified with 8,8’-O,O-[cobalt bis(1,2-dicarbollide)]phosphorothioate (1).

Figure 2.

Optical properties of AuNPs treated with compound 1. A) UV-Vis absorption spectra of untreated AuNPs colloid (dashed line) and AuNPs treated with 1 (solid lines) at the same molar concentration of gold (CAu = 2.85 × 10-4 M) and different concentrations of the functionalizing agent 1: C1 = 0.53 × 10-5 M, 0.0031 mg/mL (1); 1.07 × 10-5 M, 0.0063 mg/mL (2); 1.60 × 10-5 M (3), 0.0094 mg/mL; 2.13 × 10-5 M, 0.0125 mg/mL (4). The spectra of 1 at concentrations used are shown for comparison. B) The effect of concentration of 1 on the intensity of the LSPR band maximum, and C) the halfwidth (HW) of the LSPR band.

Figure 2.

Optical properties of AuNPs treated with compound 1. A) UV-Vis absorption spectra of untreated AuNPs colloid (dashed line) and AuNPs treated with 1 (solid lines) at the same molar concentration of gold (CAu = 2.85 × 10-4 M) and different concentrations of the functionalizing agent 1: C1 = 0.53 × 10-5 M, 0.0031 mg/mL (1); 1.07 × 10-5 M, 0.0063 mg/mL (2); 1.60 × 10-5 M (3), 0.0094 mg/mL; 2.13 × 10-5 M, 0.0125 mg/mL (4). The spectra of 1 at concentrations used are shown for comparison. B) The effect of concentration of 1 on the intensity of the LSPR band maximum, and C) the halfwidth (HW) of the LSPR band.

Figure 3.

Averaged zeta potential values of untreated AuNPs (red), CAu = 2.85 × 10-4 M, and treated AuNPs with 1 (blue), CAu = 2.85 × 10-4 M, C1 = 2.13 × 10-5 M, for original colloids (light red and light blue bars) and centrifuged, resuspendent systems (dark red and dark blue bars).

Figure 3.

Averaged zeta potential values of untreated AuNPs (red), CAu = 2.85 × 10-4 M, and treated AuNPs with 1 (blue), CAu = 2.85 × 10-4 M, C1 = 2.13 × 10-5 M, for original colloids (light red and light blue bars) and centrifuged, resuspendent systems (dark red and dark blue bars).

Figure 4.

The distribution of nanoparticles by size according to DLS data in untreated AuNPs colloid at CAu = 2.85 x 10-4 M (red) and the same AuNPs colloid treated with 1 at C1 = 2.13 x 10-5 M (blue) represented by number basis (percentage of particles by quantity) (A) and by intensity basis (percentage of particles by scattered light) (B, C). Solid lines indicate the size distribution of nanoparticles in colloids in statu nascendi, before centrifugation, and dashed lines indicate centrifuged and resuspended systems.

Figure 4.

The distribution of nanoparticles by size according to DLS data in untreated AuNPs colloid at CAu = 2.85 x 10-4 M (red) and the same AuNPs colloid treated with 1 at C1 = 2.13 x 10-5 M (blue) represented by number basis (percentage of particles by quantity) (A) and by intensity basis (percentage of particles by scattered light) (B, C). Solid lines indicate the size distribution of nanoparticles in colloids in statu nascendi, before centrifugation, and dashed lines indicate centrifuged and resuspended systems.

Figure 5.

Two shape projections of compound 1 were adopted for the calculation of AuNPs surface coverage by compound 1: A) circular projection and B) an elliptical projection.

Figure 5.

Two shape projections of compound 1 were adopted for the calculation of AuNPs surface coverage by compound 1: A) circular projection and B) an elliptical projection.

Figure 6.

ESI-mass spectra of analite derived from functionalized AuNPs with 1 recorded in negative mode. The inset shows the characteristic isotopic distribution within the molecular ion of 1.

Figure 6.

ESI-mass spectra of analite derived from functionalized AuNPs with 1 recorded in negative mode. The inset shows the characteristic isotopic distribution within the molecular ion of 1.

Figure 7.

Fluorescence properties of AuNPs/BSA systems: (A) A typical dependence of BSA fluorescence intensity (F) on nanoparticles concentration (expressed as molar Au concentration, CAu), and (B) double-logarithmic plots of BSA fluorescence spectra after the addition of untreated AuNPs (red) and AuNPs treated with compound 1 (blue). The concentrations of Au and BSA were, respectively, CAu = 3.00 x 10-5, 6.00 x 10-5, 9.00 x 10-5, 1.20 x 10-4, 1.50 x 10-4 M, and BSA concentrationCBSA = 0.01 mg/mL. Fluorescence intensity was measured at emission wavelength λem = 347 nm and excitation at λex = 270 nm and expressed in relative units.

Figure 7.

Fluorescence properties of AuNPs/BSA systems: (A) A typical dependence of BSA fluorescence intensity (F) on nanoparticles concentration (expressed as molar Au concentration, CAu), and (B) double-logarithmic plots of BSA fluorescence spectra after the addition of untreated AuNPs (red) and AuNPs treated with compound 1 (blue). The concentrations of Au and BSA were, respectively, CAu = 3.00 x 10-5, 6.00 x 10-5, 9.00 x 10-5, 1.20 x 10-4, 1.50 x 10-4 M, and BSA concentrationCBSA = 0.01 mg/mL. Fluorescence intensity was measured at emission wavelength λem = 347 nm and excitation at λex = 270 nm and expressed in relative units.

Figure 9.

Antiviral activities of gold nanoparticles: Vero cells infected with HSV-1 MOI = 0.001 (A) or MOI = 0.002 (B) treated with AuNPs; cells infected with HSV-1 MOI = 0.001 (C) or MOI = 0.002 (D) treated with AuNPs +1. In the pre-treatment assay, Vero cell monolayers were infected with HSV-1 pre-treated with gold nanoparticles, then the cell culture was additionally treated with nanoparticles at different times. In the post-treatment assay, the cells were infected with HSV-1 and then treated with gold particles. Two gold nanoparticle concentrations, 5.9 µg/mL and 0.295 µg/mL, as well as two multiplicity of infection (MOI) were used. Blue: cell control, used as a reference; orange: virus control, cells infected with virus; green: results of experiments using the 5.9 μg/ml NPs solution; violet: results of experiments using the 0.295 μg/ml NPs solution. Numbers above the bar are equal to the mean value of the cell concentration compared to the cell control in percent. The cell viability was measured using an MTT assay. The data are shown as means ± SD of three independent experiments.

Figure 9.

Antiviral activities of gold nanoparticles: Vero cells infected with HSV-1 MOI = 0.001 (A) or MOI = 0.002 (B) treated with AuNPs; cells infected with HSV-1 MOI = 0.001 (C) or MOI = 0.002 (D) treated with AuNPs +1. In the pre-treatment assay, Vero cell monolayers were infected with HSV-1 pre-treated with gold nanoparticles, then the cell culture was additionally treated with nanoparticles at different times. In the post-treatment assay, the cells were infected with HSV-1 and then treated with gold particles. Two gold nanoparticle concentrations, 5.9 µg/mL and 0.295 µg/mL, as well as two multiplicity of infection (MOI) were used. Blue: cell control, used as a reference; orange: virus control, cells infected with virus; green: results of experiments using the 5.9 μg/ml NPs solution; violet: results of experiments using the 0.295 μg/ml NPs solution. Numbers above the bar are equal to the mean value of the cell concentration compared to the cell control in percent. The cell viability was measured using an MTT assay. The data are shown as means ± SD of three independent experiments.

Table 1.

Calculated number of 8,8’-O,O-[cobalt bis(1,2-dicarbollide)]phosphorothioate (1) molecules per one nanoparticle, assuming full coverage of the NP surface by 1 (saturation state).

Table 1.

Calculated number of 8,8’-O,O-[cobalt bis(1,2-dicarbollide)]phosphorothioate (1) molecules per one nanoparticle, assuming full coverage of the NP surface by 1 (saturation state).

Table 2.

Evaluation of number of molecules per nanoparticles based on experimental results for C1 = 2.13 × 10-5 M concentration of 8,8’-O,O-[cobalt bis(1,2-dicarbollide)]-phosphorothioate (1).

Table 2.

Evaluation of number of molecules per nanoparticles based on experimental results for C1 = 2.13 × 10-5 M concentration of 8,8’-O,O-[cobalt bis(1,2-dicarbollide)]-phosphorothioate (1).

Table 3.

Ratio of experimental value of number of molecules attached to one nanoparticle to theoretical value of number of molecules needed for the full coverage of one nanoparticle for different concentrations of 8,8’-O,O-[cobalt bis(1,2-dicarbollide)]phosphorothioate (1).

Table 3.

Ratio of experimental value of number of molecules attached to one nanoparticle to theoretical value of number of molecules needed for the full coverage of one nanoparticle for different concentrations of 8,8’-O,O-[cobalt bis(1,2-dicarbollide)]phosphorothioate (1).