Submitted:

03 August 2025

Posted:

04 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Synthesis of the Block Copolymers of NVP and VEs

3.2. Self-Assembly Behavior of the PNVP-b-PVEs Block Copolymers in THF Solutions by Static Light Scattering

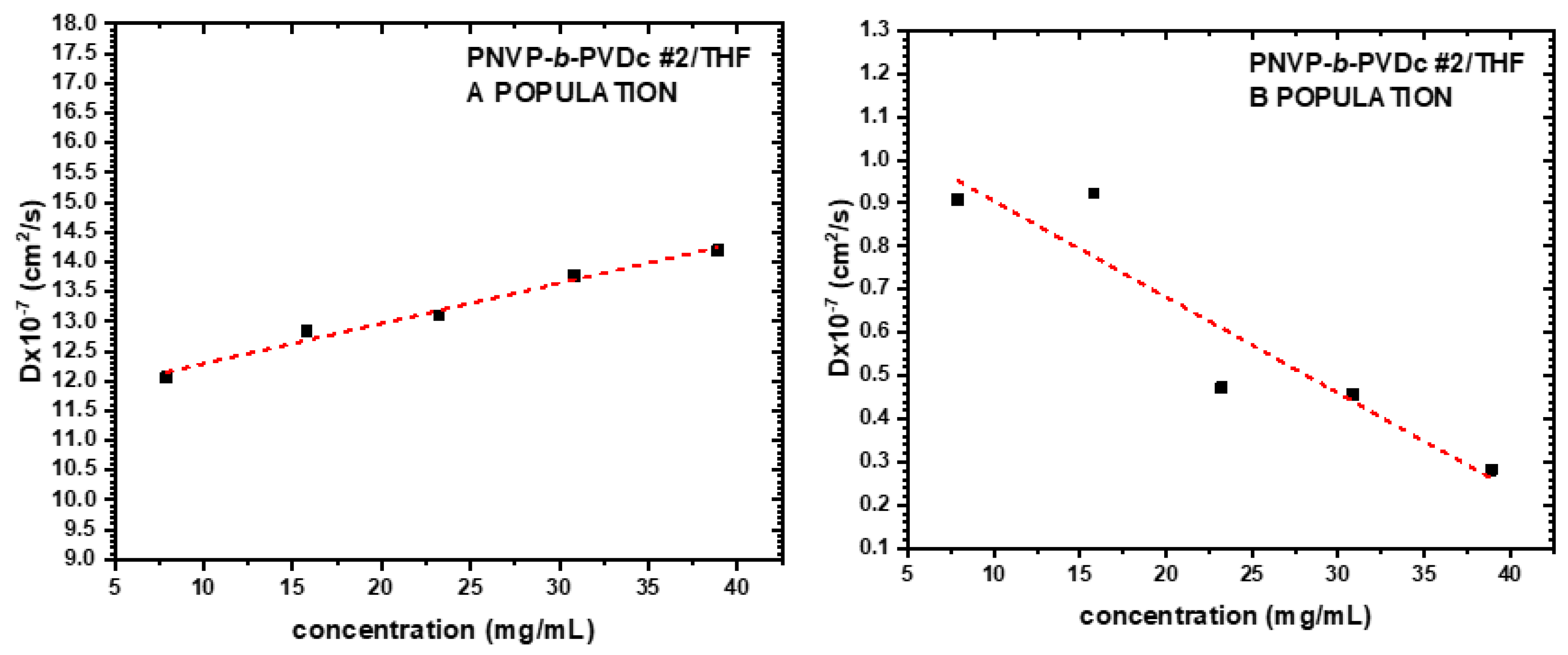

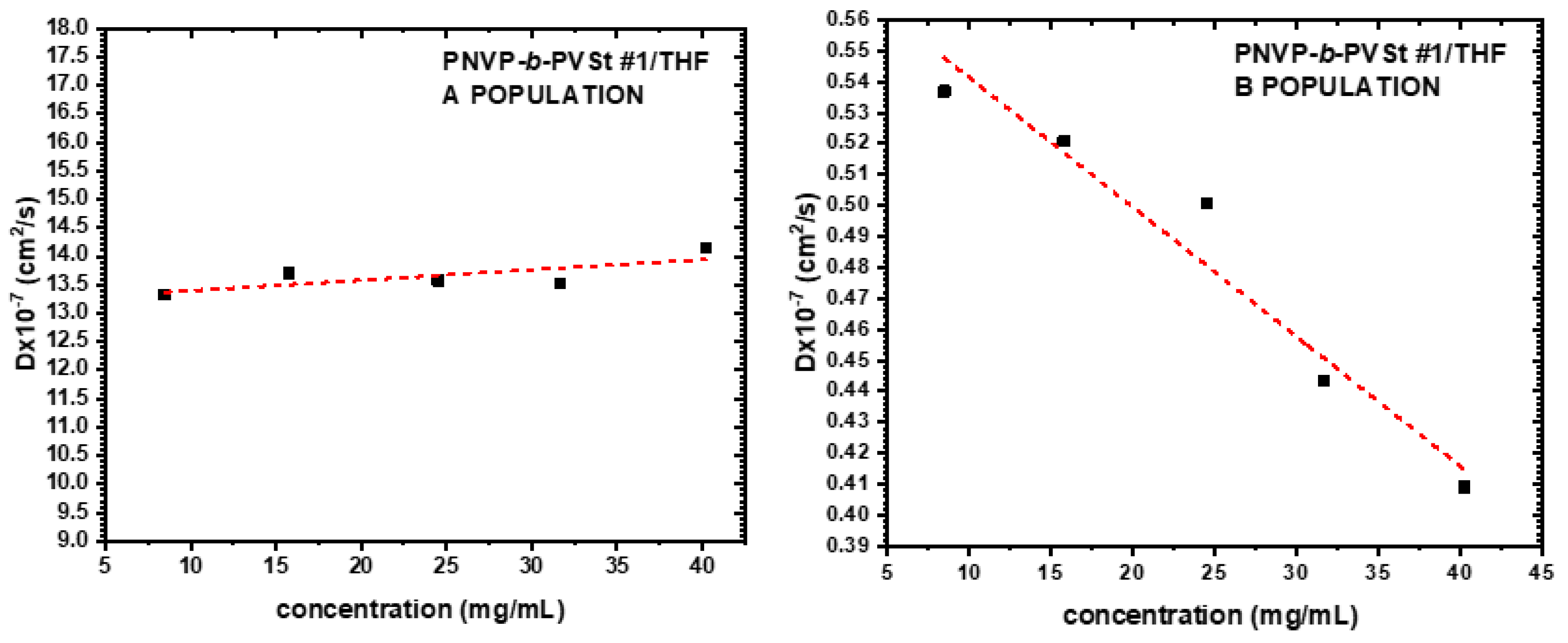

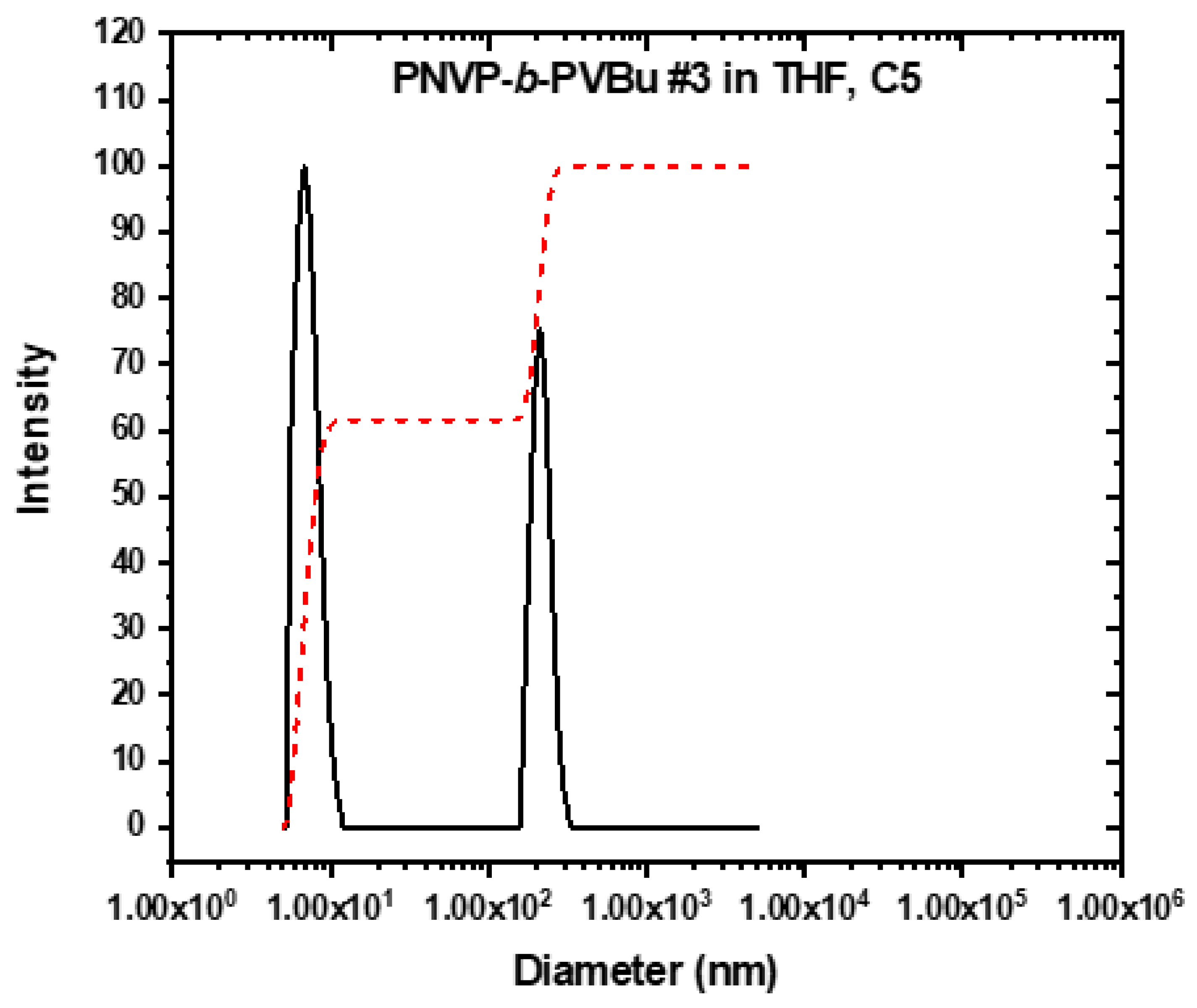

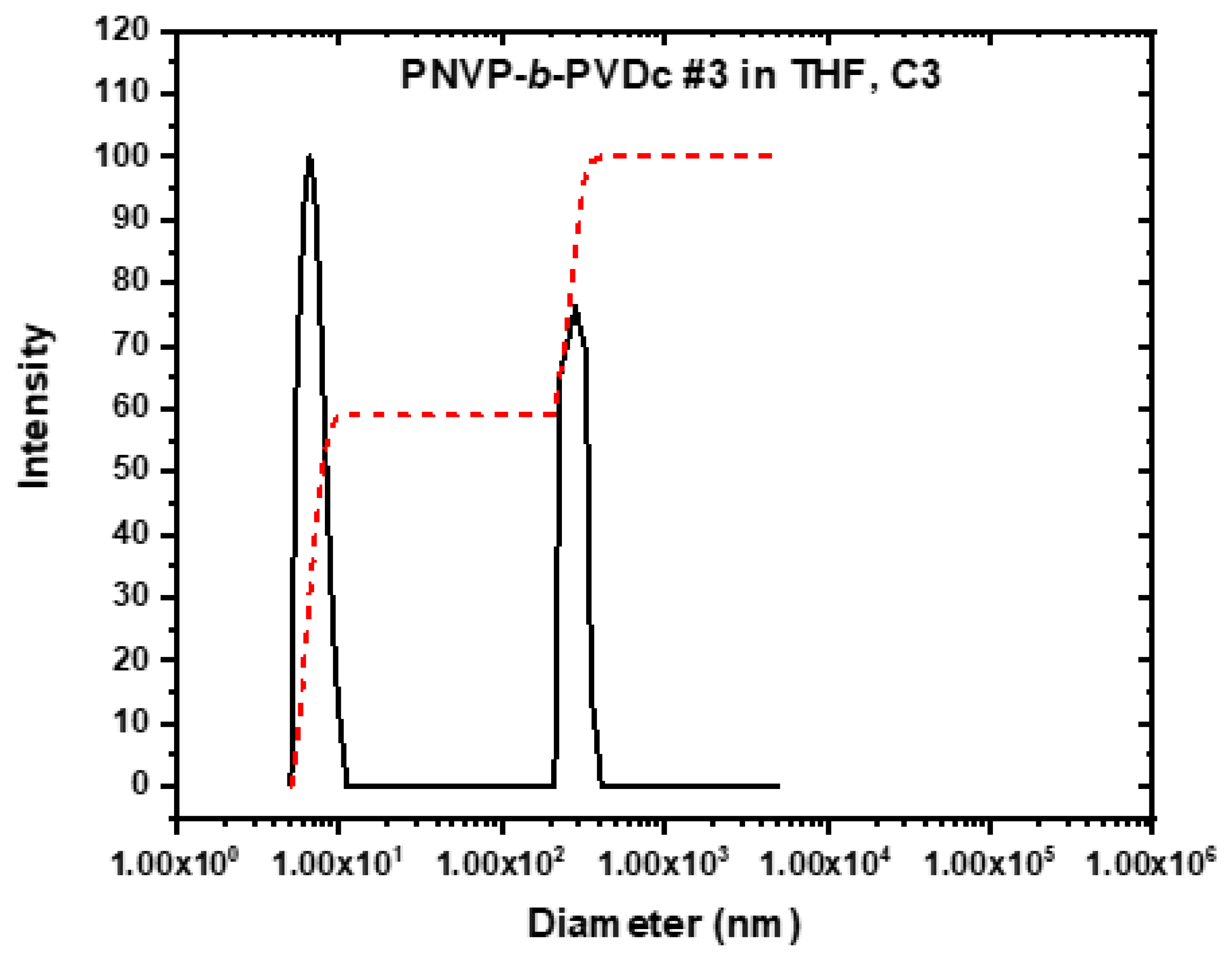

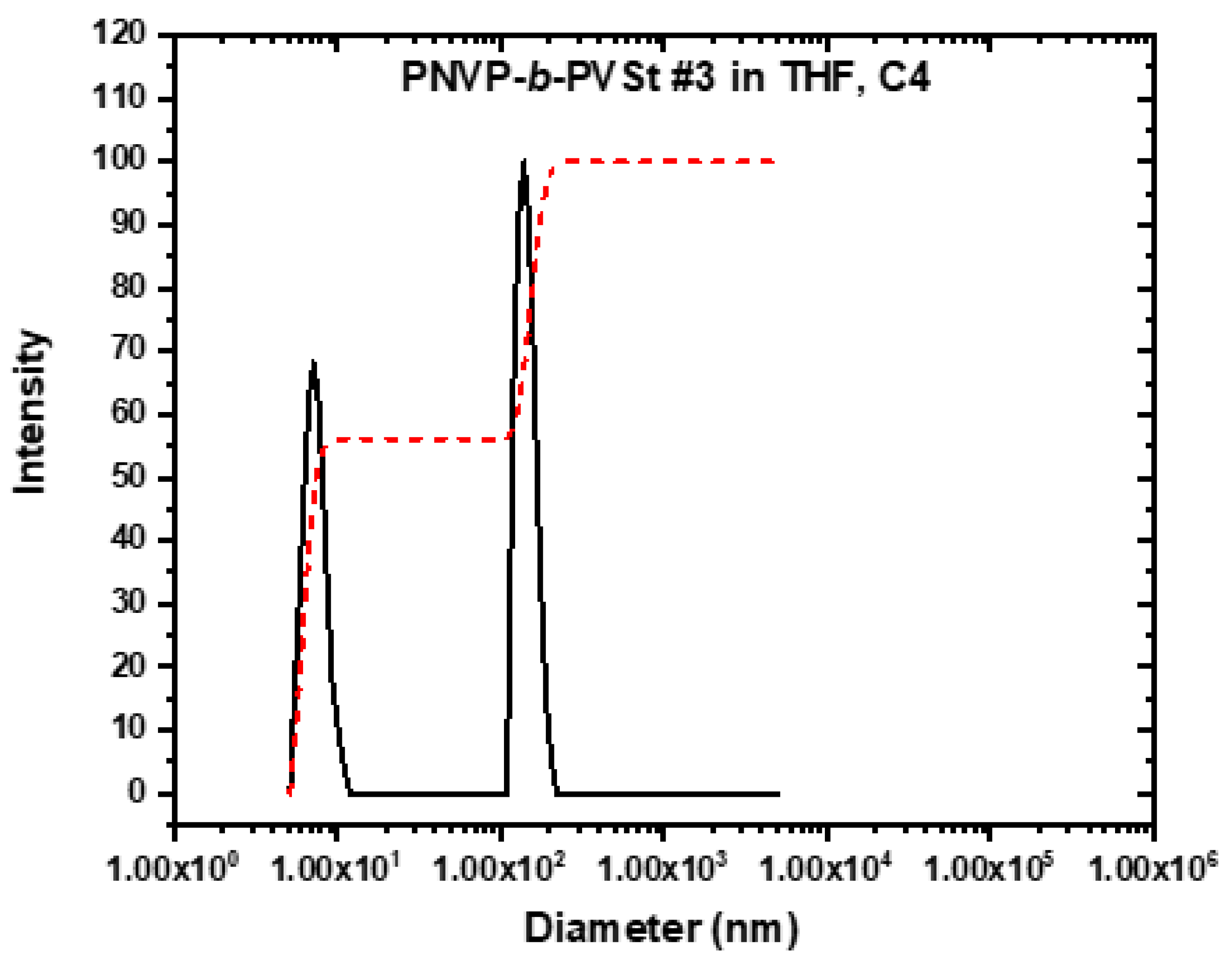

3.3. Self-Assembly Behavior of the PNVP-b-PVEs Block Copolymers in THF Solutions by Dynamic Light Scattering

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hadjichristidis, N.; Pispas, S.; Floudas, G.A. Block copolymers. In Synthetic Strategies, Physical Properties and Applications; J. Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003.

- Hamley, I.W. The Physics of Block Copolymers; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1998.

- Developments in block copolymer science and technology; Wiley, Chichester, West Sussex, England, Hamley, I.W. Ed., 2004.

- Complex macromolecular architectures. Synthesis, characterization and self-assembly, J. Wiley & Sons (Asia) Pte Ltd, Hadjichristidis, N.; Hirao, A.; Tezuka, Y.; Du Prez, F. Singapore, 2011.

- Ofstead, E.A.; Wagener, K.B. in New methods for polymer synthesis, Mijs W.J. Ed. 1992 Plenum Press.

- Mortensen, K. PEO-related block copolymer surfactants. Colloids Surf. A 2001, 183, 277–292. [CrossRef]

- Adams, M.L.; Lavasanifar, A.; Kwon, G.S. Amphiphilic block copolymers for drug delivery. J. Pharm. Sci. 2003, 92, 1343–1355. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Ha, J.C.; Lee, Y.M. Poly (ethylene oxide)-poly (propylene oxide)-poly (ethylene oxide)/poly(ϵ-caprolactone)(PCL) amphiphilic block copolymeric nanospheres: II. Thermo-responsive drug release behaviors. J. Contr. Release 2000, 65, 345–358. [CrossRef]

- Torchilin, V.; Levchenko, T.; Whiteman, K.; Yaroslav, A.; Tsatsakis, A.; Rizos, A.; Michailova, E.; Shtilman, M. Amphiphilic poly-N-vinylpyrrolidone synthesis, properties and liposome surface modification. Biomaterials 2001, 22, 3035–3044.

- Roka, N.; Kokkorogianni, O.; Kontoes-Georgoudakis, P.; Choinopoulos, I.; Pitsikalis, M. Recent Advances in the Synthesis of Complex Macromolecular Architectures Based on Poly(N-vinyl pyrrolidone) and the RAFT Polymerization Technique Polymers 2022, 14, 701. [CrossRef]

- Hadjichristidis, N.; Pitsikalis, M.; Iatrou, H. Synthesis of block copolymers. Adv. Polym. Sci. 2005, 189, 11–24.

- Theodosopoulos, G.; Pitsikalis M. Block Copolymers: Recent Synthetic Routes and Developments. in “Anionic Polymerization: Principles, Practice, Strength, Consequences and Applications” J. Wiley & Sons (Asia) Pte Ltd, Hadjichristidis, N.; Hirao, A.; Tezuka, Y.; Du Prez, F. Singapore, 2011.

- Hadjichristidis, N.; Pitsikalis, M.; Pispas, S; Iatrou H. Polymers with complex architectures by living anionic polymerization Chem. Rev. 2001, 101, 3747–3792. [CrossRef]

- Anionic Polymerization: Principles, Practice, Strength, Consequences and Applications Hadjichristidis, N.; Hirao A. Eds Springer, 2015.

- Kennedy, J. P. Living cationic polymerization of olefins. How did the discovery come about? J. Polym. Sci., Part A: Polym. Chem. 1999, 37, 2285–2293.

- Webster, O. W. The discovery and commercialization of group transfer polymerization. J. Polym. Sci., Part A: Polym. Chem. 2000, 38, 2855–2860.

- Leitgeb, A.; Wappel, J.; Slugovc, C. The ROMP toolbox upgraded. Polymer 2010, 51, 2927–2946. [CrossRef]

- Handbook of Radical Polymerization Matyjaszewski, K.; Davis T.P. Eds. Wiley-Interscience, Hoboken, New Jersey 2002.

- Martin, L.; Gody, G.; Perrier, S. Preparation of complex multiblock copolymers via aqueous RAFT polymerization at room temperature. Polym. Chem. 2015, 6, 4875–4886. [CrossRef]

- Hadjichristidis, N.; Iatrou, H.; Pitsikalis, M.; Mays, J.W. Macromolecular architectures by living and controlled/living polymerizations Progr. Polym. Sci. 2006, 31, 1068–1132. [CrossRef]

- Hadjichristidis, N.; Pitsikalis, M.; Iatrou, H.; Sakellariou, G. Macromolecular architectures by living and controlled/living polymerizations in Controlled and Living Polymerizations. From Mechanisms to Applications Müller, A.H.E.; Matyjaszewski K. Eds., Wiley VCH, chapter 7, 2009, 343–443.

- Dau, H.; Jones, G.R.; Tsogtgerel, E.; Nguyen, D.; Keyes, A.; Liu, Y.-S.; Rauf, H.; Ordonez, E.; Puchelle, V.; Alhan, H.B.; Zhao, C.; Harth, E. Linear block copolymer synthesis Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 14471–14553. [CrossRef]

- Dey, A.; Hldar, U.; De, P. Block copolymer synthesis by the combination of living cationic polymerization and other polymerization methods Frontiers in Chemistry 2021, 9, 644547.

- Diaz, C.; Mehrkhodavandi, P. Strategies for the synthesis of block copolymers with biodegradable polyester segments Polym. Chem. 2021, 12, 783–806. [CrossRef]

- Macromolecular design of polymeric materials Hatada K.; Kitayama; T.; Vogl, O. Eds Marcel Dekker Inc Chapters 3,4, 1997.

- Matyjaszewski, K.; Xia, Atom transfer radical polymerization. J Chem Rev. 2001, 101, 2921–2990.

- Coessens, V.; Pintauer, T.; Matyjaszewski, K. Functional polymers by atom transfer radical polymerization. Progr Polym Sci. 2001, 26, 337–377. [CrossRef]

- Hawker, C.J.; Bosman, A,W.; Harth, E. New polymer synthesis by nitroxide mediated living radical polymerizations. Chem Rev 2001, 101, 3661–3688. [CrossRef]

- Buchmeiser, M.R. Homogeneous metathesis polymerization by well-defined group VI and group VIII transition-metal alkylidenes: Fundamentals and applications in the preparation of advanced materials. Chem Rev 2000, 100, 1565–1604. [CrossRef]

- Khandpur, A.K.; Förster, S.; Bates, F.S.; Hamley, I.; Ryan, A.J.; Almdal, K. Mortensen, K. Polyisoprene-polystyrene diblock copolymer phase diagram near the order-disorder transition Macromolecules 1995, 28, 8796–8806. [CrossRef]

- Floudas, G.; Vazaiou B.; Schipper, F.; Ulrich, R.; Wiesner, U.; Iatrou, H.; Hadjichristidis, N. Poly(ethylene oxide-b-isoprene) diblock copolymer phase diagram Macromolecules 2001, 34, 2947-2957.

- Abetz, V.; Simon, P.F.W. Phase behaviour and morphologies of block copolymers. Adv. Polym. Sci. 2005, 189, 125–212.

- Bates, F.M.; Fredrickson, G.H. Block copolymer thermodynamics-theory and experiment. Ann. Rev. Phys. Chem. 1990, 41, 525–557. [CrossRef]

- Webber, S.E.; Munk, P.; Tuzar, Z. Eds. Solvents and Self-organization of Polymers NATO ASI Series Vol. 327, Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1996,.

- Xie, H.Q.; Xie, D. Molecular design, synthesis and properties of block and graft copolymers containing polyoxyethylene segments Progr. Polym. Sci. 1999, 24, 275–313.

- Gohy, J.-F. Block copolymer micelles. Adv. Polym. Sci. 2005, 190, 65–136.

- Riess, G. Micellization of block copolymers. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2003, 28, 1107–1170.

- Rodrígeuz-Hernádez, J.; Chécot, F.; Gnanou, Y.; Lecommandoux, S. Toward ‘smart’ nano-objects by self-assembly of block copolymers in solution. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2005, 30, 691–724.

- Astafieva, I.; Zhong, X.F.; Eisenberg, A. Critical micellization phenomena in block polyelectrolyte solutions Macromolecules 1993, 26, 7339-7352.

- Prochazka, K.; Bednar, B.; Mukhtar, E.; Svoboda, P.;Trnena, J.; Almgren, M. Nonradiative energy transfer in block copolymer micelles J. Phys. Chem. 1991, 95, 4563-4568. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Kausch, C.M.; Chun, M.; Quirk, R.P.; Mattice, W.L. Exchange of chains between micelles of labeled polystyrene-block-poly(oxyethylene) as monitored by nonradiative singlet energy transfer Macromolecules 1995, 28, 904-911. [CrossRef]

- Sidorov, S.N.; Bronstein, L.M.; Valetsky, P.M.; Hartmann, J.; Coelfen, H.; Schnablegger, H.; Antonietti, M. Stabilization of metal nanoparticles in aqueous medium by poly(ethylene oxide)-poly(ethylene imine) block copolymers. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1999, 212, 197–211.

- Spatz, J.P.; Sheiko, S.; Möller, M. Ion stabilized block copolymer micelles film formation and inter micellar interaction. Macromolecules 1996, 29, 3220–3226.

- Lazzari, M.; Scalarone, D.; Hoppe, C.E.; Vazquez-Vazquez, C.; Lòpez-Quintela, M.A. Tunable polyacrylonitrile based micellar aggregates as a potential tool for the fabrication of carbon nanofibers. Chem. Mater. 2007, 19, 5818–5820. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L.Y.; Bae, Y.H. Polymer Architecture and Drug Delivery. Pharm. Res. 2006, 23, 1–30.

- Karanikolopoulos, N.; Pitsikalis, M.; Hadjichristidis, N.; Georgikopoulou, K.; Calogeropoulou, T.; Dunlap, J. R. “pH-Responsive aggregates from double hydrophilic block copolymers carrying zwitterionic groups. Encapsulation of antiparasitic compounds for the treatment of leishmaniasis” Langmuir. 2007, 23, 4214–4224.

- Kwon, G.S.; Okano, T. Polymeric micelles as new drug carriers. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 1996, 21, 107–116. [CrossRef]

- Karanikolopoulos, N.; Zamurovic, M.; Pitsikalis, M.; Hadjichristidis, N. Poly(DL-lactide)-b-Poly(N,N-dimethylamino-2-ethyl methacrylate): Synthesis, characterization, micellization behaviour in aqueous solutions and encapsulation of the hydrophobic drug dipyridamole. Biomacromolecules. 2010, 11, 430–438.

- Kwon, G.S.; Okano, T. Polymeric micelles as new drug carriers.Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 1996, 21, 107–116.

- Li, J.; Barrow, D.; Howell, H.; Kalachandra, S. In vitro drug release study of methacrylate polymer blend system: effect of polymer blend composition, drug loading and solubilizing surfactants on drug release. J. Mater. Sci.: Materials in Medicine 2010, 21, 583–588. [CrossRef]

- Heinzmann, C.; Salz, U.; Moszner, N.; Fiore, G.L.; Weder, C. Supramolecular Cross-Links in Poly(alkyl methacrylate) Copolymers and Their Impact on the Mechanical and Reversible Adhesive Properties. ACS Appl. Mater. & Interf. 2015, 7, 13395−13404. [CrossRef]

- Khai, N.; Nguyen, H.; Dang, H.H.; Nguyen, L.T.; Nguyen, L.M.T.; Truong, T.T.; Nguyen, H.T.; Nguyen, T.Q.; Tran, C.D.; Nguyen, L.-T.T. Self-healing elastomers from supramolecular random copolymers of 4-vinyl pyridine. Europ. Polym. J. 2023, 199, 112474. [CrossRef]

- Trubetskoy, V.S. Polymeric micelles as carriers of diagnostic agents. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 1999, 37, 81–88. [CrossRef]

- Gerst, M.; Schuch, H.; Urban, D. Amphiphilic Block Copolymers as Surfactants in Emulsion Polymerization. ACS Symposium Series; Glass, J.E., Ed.; ACS Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2000, 765, 37–51.

- Yu-Su, S.Y.; Thomas, D.R.; Alford, J.E.; LaRue, I.; Pitsikalis, M.; Hadjichristidis, N.; DeSimone, J.M.; Dobrynin, A.V.; Sheiko, S.S. Molding copolymer micelles: A framework for molding of discrete objects on surfaces. Langmuir 2008, 24, 12671–12679. [CrossRef]

- Kataoka, K.; Harada, A.; Nagasaki, Y. Block copolymer micelles for drug delivery: Design, characterization and biological significance. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2001, 47, 113–131. [CrossRef]

- Bronstein, L.M.; Sidorov, S.N.; Valetsky, P.M.; Hartmann, J.; Coelfen, H.; Antonietti, M. Induced micellization by interaction of poly(2-vinylpyridine)-block-poly(ethylene oxide) with metal compounds. Micelle characteristics and metal nanoparticle formation. Langmuir 1999, 15, 6256–6262.

- Munch, M.R.; Gast, A.P. Kinetics of block copolymer adsorption on dielectric surfaces from a selective solvent. Macromolecules 1990, 23, 2313–2320. [CrossRef]

- Breulmann, M.; Förster, S.; Antonietti, M. Mesoscopic surface patterns formed by block copolymer micelles. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2000, 201, 204–211.

- Lazzari, M.; Scalarone, D.; Hoppe, C.E.; Vazquez-Vazquez, C.; Lòpez-Quintela, M.A. Tunable polyacrylonitrilebased micellar aggregates as a potential tool for the fabrication of carbon nanofibers. Chem. Mater. 2007, 19, 5818–5820. [CrossRef]

- Roka, N.; Pitsikalis, M. Synthesis and micellization behavior of amphiphilic block copolymers of poly(N-vinyl pyrrolidone) and poly(benzyl methacrylate): Block versus statistical copolymers. Polymers 2023, 15, 2215. [CrossRef]

- Kontoes-Georgoudakis, P.; Plachouras, N.V.; Kokkorogianni, O.; Pitsikalis, M. Amphiphilic block copolymers of poly(N-vinyl pyrrolidone) and poly (isobornyl methacrylate). Synthesis, characterization and micellization behaviour in selective solvents. Europ. Polym. J. 2024, 208, 112873.

- Roka, N.; Pitsikalis, M. Statistical copolymers of N-vinylpyrrolidone and benzyl methacrylate via RAFT: Monomer reactivity ratios, thermal properties and kinetics of thermal decomposition J. Macromol. Sci., Part A: Pure Appl. Chem. 2018, 55, 222–230. [CrossRef]

- Karatzas, A.; Bilalis, P.; Iatrou, H.; Pitsikalis, M.; Hadjichristidis, N. Synthesis of well-defined functional macromolecular chimeras based on poly(ethylene oxide) or poly(N-vinyl pyrrolidone) React. Funct. Polym. 2009, 69, 435–440. [CrossRef]

- Bilalis, P.; Zorba, G.; Pitsikalis, M.; Hadjichristidis, N. Synthesis of poly(n-hexyl isocyanate-b-N-vinylpyrrolidone) block copolymers by the combination of anionic and nitroxide-mediated radical polymerizations: Micellization properties in aqueous solutions J. Polym. Sci., Part A: Polym. Chem. Ed. 2006, 44, 5719–5728.

- Bilalis, P.; Pitsikalis, M.; Hadjichristidis, N. Controlled nitroxide-mediated and reversible addition-fragmentation chain transfer polymerization of N-vinylpyrrolidone: Synthesis of block copolymers with styrene and 2-vinylpyridine J. Polym. Sci., Part A: Polym. Chem. Ed. 2006, 44, 659–665.

- Roka, N.; Kokkorogianni, O.; Pitsikalis, M. Statistical copolymers of N-vinylpyrrolidone and 2-(dimethylamino)ethyl methacrylate via RAFT: Monomer reactivity ratios, thermal properties, and kinetics of thermal decomposition. J. Polym. Sci. Polym. Chem. 2017, 55, 3776–3787.

- Fokaidis-Psyllas A.; Kokkorogianni, O.; Pitsikalis, M. Statistical copolymers of N-vinylpyrrolidone and phenoxyethyl methacrylate via RAFT polymerization: monomer reactivity ratios, thermal properties, kinetics of thermal decomposition and self-assembly behavior in selective solvents Polym. Bull. 2025 in press. [CrossRef]

- Plachouras, N.V.; Pitsikalis, M. Statistical copolymers of N–vinylpyrrolidone and 2–chloroethyl vinyl ether via radical RAFT polymerization: Monomer reactivity ratios, thermal properties, and kinetics of thermal decomposition of the statistical copolymers Polymers 2023, 15(8), 1970.

- Roka, N.; Papazoglou, T.P.; Pitsikalis, M. Statistical copolymers of Poly(N–vinylpyrrolidone) and Poly(vinyl esters) bearing n-alkyl side groups via radical RAFT polymerization: Synthesis, characterization and thermal properties. Polymers 2024, 16, 2447.

- Rinno, H. Poly(vinyl esters) In Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH&Co. KGaA: Weinheim, Germany, 2000; Volume 28, pp.469-479.

- Murray, R.E.; Lincoln, D.M. Catalytic route to vinyl esters. Catal. Today, 1992, 13, 93–102. [CrossRef]

- Charmot, D.; Corpart, P.; Adam, H.; Zard, S.Z.; Biadatti, T.; Bouhadir, G. Controlled radical polymerization in dispersed media. Macromol. Symp. 2000, 150, 23–32.

- Matioszek, D.; Brusylovets, O.; Wilson, D.J.; Mazières, S.; Destarac, M. Reversible addition-fragmentation chain-transfer polymerization of vinyl monomers with N,N-dimethylsdiselenocarbamates. J. Polym. Sci. Part A: Polym, Chem., 2013, 51, 4361–4368.

- Benard, J.; Favier, A.; Zhang, L.; Nilararoya, A.; Davis, T.P.; Barner-Kowollik, C.; Stenzel, M.H. Poly(vinyl ester) star polymers via xanthate-mediated living radical polymerization: From poly(vinyl alcohol) to glycopolymer stars. Macromolecules 2005,38, 5475-5484. [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; He, J.; Li, C.; Zhou, C.; Song, S.; Yang, Y. Block copolymerization of vinyl acetate and vinyl neo-decanoate mediated by dithionosulfide. Macromolecules, 2010, 43, 4500–4510. [CrossRef]

- Lipscomb, C.E.; Mahanthappa, M.K. Poly(vinyl ester) block copolymers synthesized by reversible addition-fragmentation chain transfer polymerizations. Macromolecules, 2009, 42, 4571–4579. [CrossRef]

- Lipscomb, C.E.; Mahanthappa, M.K. Microphase separation mode-dependent mechanical response in poly(vinyl ester)/PEO triblock copolymers. Macromolecules, 2011, 44, 4401–4409. [CrossRef]

- Pingpin, Z.; Yuanli L.; Haiyang Y.; Xiaoming C. Effect of non-ideal mixed solvents on dimensions of poly(N-vinylpyrrolidone) and poly(methyl methacrylate) coils J. Macromol. Sci. Part B: Polym. Phys. 2006, 45, 1125–1134. [CrossRef]

- Provencher, S.W. CONTIN: A general purpose constrained regularization program for inverting noisy linear algebraic and integral equations. Comput. Phys. Commun. 1982, 27, 229–242. [CrossRef]

| Macro CTA (PNVP) a |

Block Copolymers a |

NVP |

Vinyl Ester |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | Mn 103 (Daltons) |

Ð | Mn 103 (Daltons) | Ð | % molb | % molb |

| PNVP-b-PVBu #1 | 8.5 | 1.30 | 16.0 | 1.90 | 22 | 78 |

| PNVP-b-PVBu #2 | 28.0 | 1.27 | 32.0 | 1.32 | 84 | 16 |

| PNVP-b-PVBu #3 | 8.9 | 1.35 | 17.5 | 1.40 | 57 | 43 |

| PNVP-b-PVBu #4 | 8.9 | 1.35 | 15.5 | 1.54 | 48 | 52 |

| PNVP-b-PVDc #1 | 8.5 | 1.30 | 12.5 | 1.31 | 63 | 37 |

| PNVP-b-PVDc #2 | 5.5 | 1.47 | 12.5 | 1.60 | 38 | 62 |

| PNVP-b-PVDc #3 | 8.5 | 1.30 | 11.0 | 1.45 | 56 | 44 |

| PNVP-b-PVDc #4 | 9.5 | 1.36 | 10.5 | 1.36 | 93 | 7 |

| PNVP-b-PVSt #1 | 8.5 | 1.30 | 10.5 | 1.44 | 78 | 22 |

| PNVP-b-PVSt #2 | 7.5 | 1.30 | 10.4 | 1.51 | 61 | 39 |

| PNVP-b-PVSt #3 | 8.1 | 1.30 | 10.9 | 1.37 | 85 | 15 |

| PNVP-b-PVSt #4 | 8.1 | 1.30 | 12.5 | 1.22 | 83 | 17 |

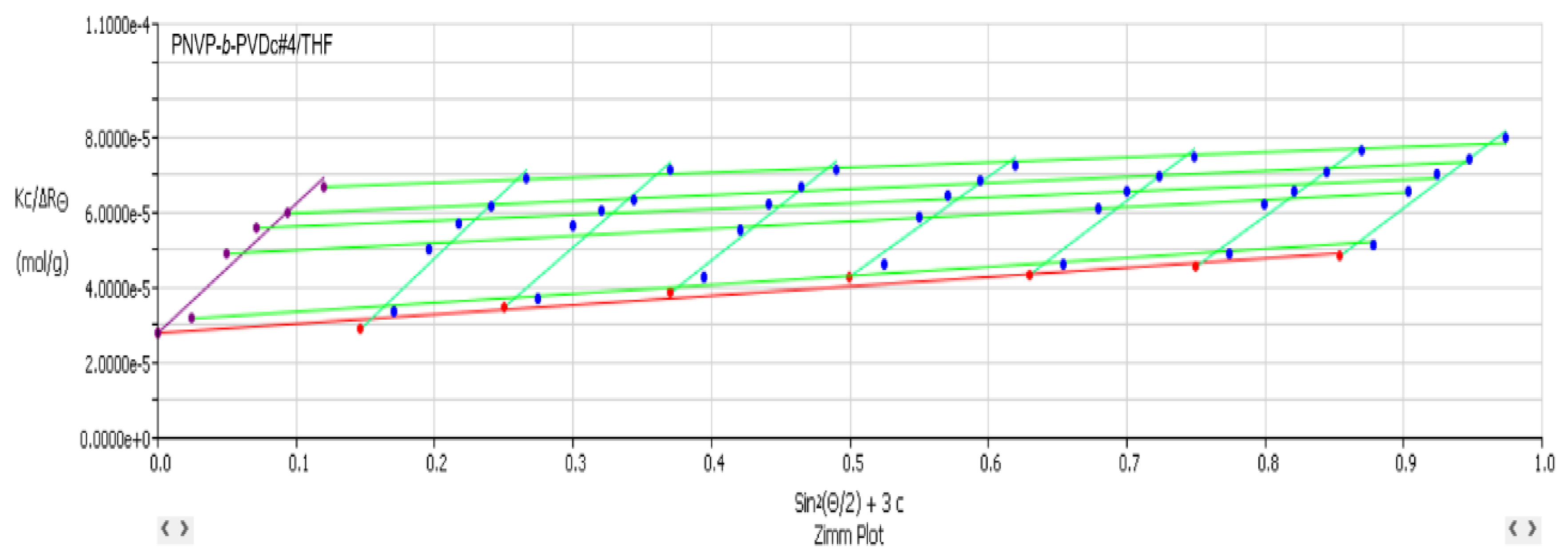

| Sample | Mw x10-4 |

Nw | A2 x 104 (cm3mol/g2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PNVP-b-PVBu #1 | 15.9 | 9.94 | 1.40 |

| PNVP-b-PVBu #2 | 5.69 | 1.78 | 0.69 |

| PNVP-b-PVBu #3 | 3.62 | 2.07 | 3.86 |

| PNVP-b-PVBu #4 | 3.22 | 2.08 | 4.39 |

| PNVP-b-PVDc #1 | 10.5 | 8.40 | 3.50 |

| PNVP-b-PVDc #2 | 6.35 | 5.08 | 2.07 |

| PNVP-b-PVDc #3 | 3.35 | 3.05 | 2.50 |

| PNVP-b-PVDc #4 | 3.59 | 3.42 | 5.16 |

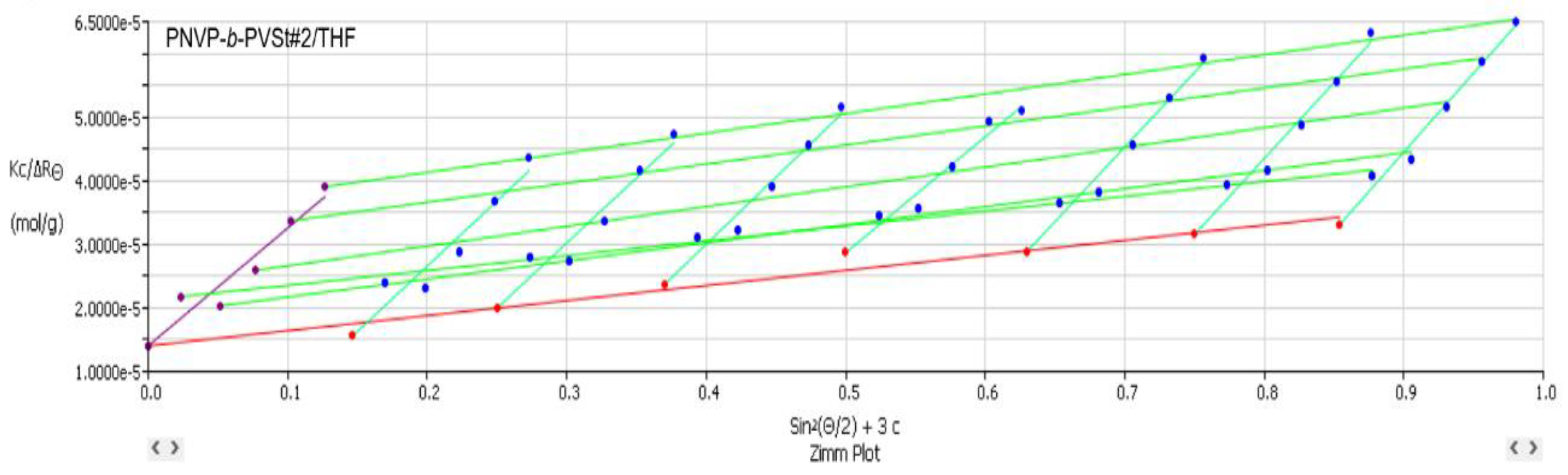

| PNVP-b-PVSt #1 | 3.82 | 3.64 | 1.48 |

| PNVP-b-PVSt #2 | 7.13 | 6.86 | 2.78 |

| PNVP-b-PVSt #3 | 4.44 | 4.07 | 1.30 |

| PNVP-b-PVSt #4 | 18.6 | 14.88 | 1.90 |

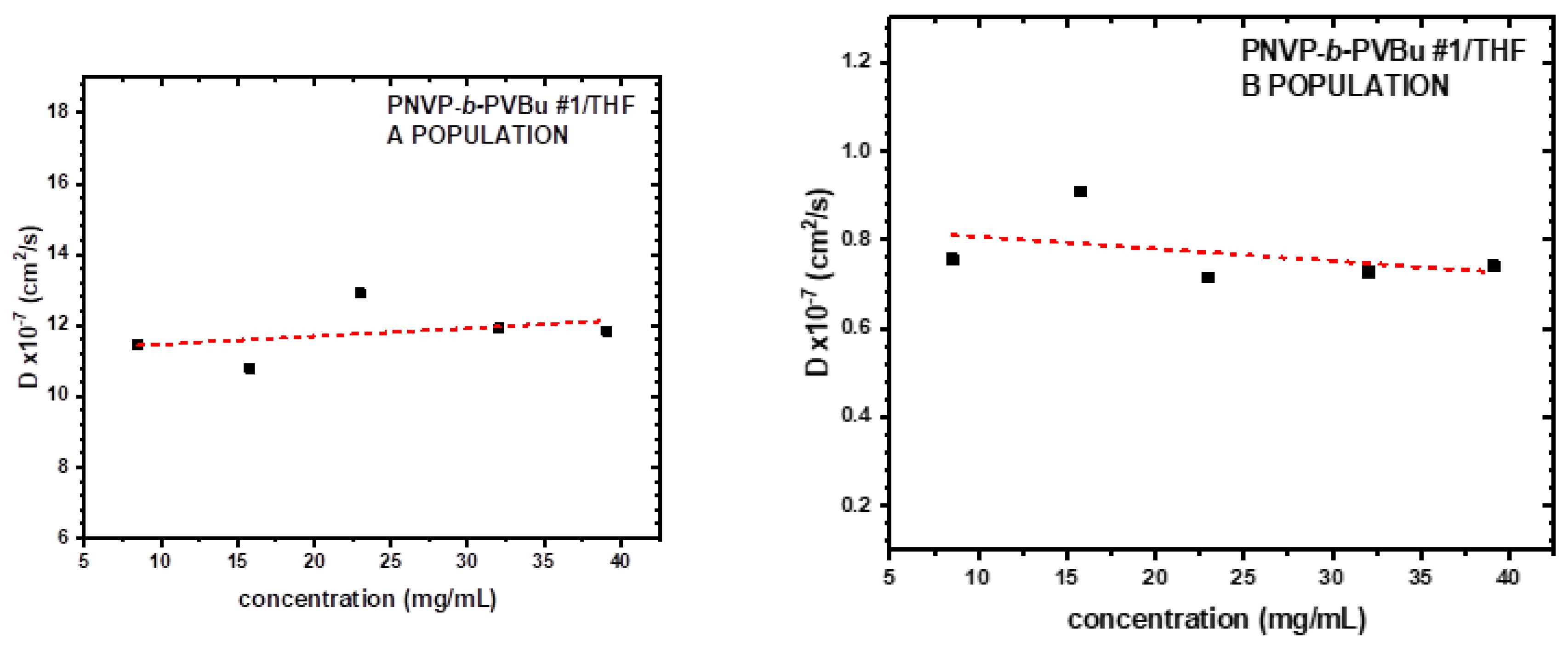

| Sample | Do (cm2/s) |

Kd | Rho A (nm) |

Rho B (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PNVP-b-PVBu #1 | 11.2405 | 2.04 | 4.22 | 48.45 |

| PNVP-b-PVBu #2 | 9.19953 | -2.98 | 5.16 | 96.31 |

| PNVP-b-PVBu #3 | 9.9667 | 8.58 | 4.76 | 170.06 |

| PNVP-b-PVBu #4 | 10.4839 | 4.63 | 4.53 | 32.97 |

| PNVP-b-PVDc #1 | 15.1746 | -1.11 | 3.13 | 15.58 |

| PNVP-b-PVDc #2 | 14.2491 | 0.96 | 3.33 | 35.82 |

| PNVP-b-PVDc #3 | 11.6172 | 5.81 | 4.08 | 76.10 |

| PNVP-b-PVDc #4 | 14.0547 | 0.29 | 3.38 | 85.11 |

| PNVP-b-PVSt #1 | 12.2076 | 3.09 | 3.89 | 71.94 |

| PNVP-b-PVSt #2 | 13.2195 | 1.37 | 3.59 | 81.37 |

| PNVP-b-PVSt #3 | 14.3697 | 0.32 | 3.30 | 84.08 |

| PNVP-b-PVSt #4 | 13.8421 | 1.40 | 3.43 | 94.93 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).