1. Introduction

Poly(N-vinyl pyrrolidone), PNVP, is one of the most important water soluble polymers having a unique combination of properties including biocompatibility, lack of toxicity, ability to form complexes with metal ions, chemical and thermal resistance, ability to form uniform films and a high Tg value, which can be reduced upon absorbing humidity [

1]. These properties lead to numerous applications in several industrial sectors, including the pharmaceutical, biomedical and cosmetics sector, where PNVP can be used as blood plasma substitute, tablet binder for the enhancement of drug stability and dissolution, solubilizer for suspensions, in wound healing and disinfectant solutions (e.g., PNVP-Iodine), dispersion of crystallizing drugs, tissue engineering (scaffolds), hydrogels/nanogels, nanocarriers for drug/gene/protein/peptide delivery, wound/burn dressings, wettability of contact lenses, dental restoration, antifouling agent [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12], film for hair dressing products, setting lotions and conditioning shampoos [

13,

14,

15]. In addition, PNVP can be employed in food products [

8,

14,

15] as clarifying agent and food stabilizer (food processing for moisture retention), adhesives [

14,

15], as a suspending agent in polymerization systems, in textile processing as a dye-affinitive stripping and leveling agent [

14,

15,

16], in fuel cells and batteries technology [

17,

18], in environmental protection for the removal of heavy metals [

13] in the synthesis of metal nanoparticles [

19,

20] etc.

PNVP is an essential material for the development of amphiphilic block copolymers. These are macromolecules composed of two or more chemically distinct polymer segments, typically a hydrophilic (water-attracting) block and a hydrophobic (water-repelling) block [

21,

22,

23,

24]. This dual nature allows them to self-assemble into various nanostructures such as micelles, vesicles, and hydrogels, making them highly valuable in biomedical, pharmaceutical, and nanotechnology applications [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35]. Numerous linear (diblocks, triblocks, multiblocks) and non-linear (miktoarm stars, grafts, branched polymers) structures have been synthesized offering tools for numerous applications [

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54]. Amphiphilic block copolymers can be employed as polymeric micelles to encapsulate drugs for targeted therapy, as nanocarriers for gene therapy, delivering siRNA and DNA to target cells, as biodegradable hydrogels, which are used in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine, or as stimuli-responsive drug carriers, offering response to pH, temperature, and enzymes for controlled release [

55,

56]. Furthermore, they can be applied as anti-fouling coatings preventing bacterial adhesion, and as self-healing systems [

57,

58]. Amphiphilic block copolymers may also act as templates for nanoparticles, as surfactants and as emulsifiers [

59,

60,

61].

Among the various hydrophilic polymers poly(ethylene oxide), PEO, has been mostly employed for biomedical and pharmaceutical applications. The biocompatibility, the low toxicity, the commercial availability of samples with various molecular weights and end-groups along with the stealth properties, preventing the recognition of nanoparticles and uptake by the reticuloendothelial system are the main advantages of PEO for these applications [

62,

63,

64,

65,

66]. However, the recent developments of COVID-19 vaccines revealed several drawbacks of PEO as a stealth material [

67,

68,

69,

70]. For example, reduced interactions between liposomes and cell membranes were confirmed, when the liposomes were grafted with PEO, leading to decreased cellular uptake and endosomal escape, thus preventing the gene delivery. In addition, repeated administration of PEO covered nanoparticles led to immunogenicity implications. PEO was also found responsible for mild and even severe allergic reactions to patients. Therefore, there is a need for alternative solutions replacing PEO as the hydrophilic material. Towards this direction, PNVP has proven to be an adequate substitute of PEO as a water-soluble polymer. Several studies pointed to this direction and provided evidence that PNVP is an ideal replacement of PEO [

71,

72,

73,

74].

The limiting factor preventing the extended use of PNVP in pharmaceutical applications was for many years the difficulties to control the polymerization of the NVP monomer. However, the recent developments in Reversible Addition Fragmentation Chain Transfer, RAFT, polymerization technique offered the opportunity to synthesize well-defined statistical, diblock and triblock copolymers along with more complex architectures, such as star, graft and other branched copolymers [

75,

76]. The ability of these structures to self-assemble in selective solvents has been already demonstrated.

In this work, the synthesis of amphiphilic block copolymers of NVP with n-hexyl-, HMA, and stearyl methacrylate, SMA, is described. Poly(n-hexyl methacrylate), PHMA is a hydrophobic, water-insoluble polymer derived from HMA monomer. It is known for its flexibility, low glass transition temperature, Tg, and potential applications in protective coatings, offering flexibility and hydrophobicity, pressure-sensitive adhesives for packaging and medical tapes, biomedical research in drug delivery systems and bioinert coatings, due to its non-toxic and non-degradable properties, flexible electronics & optoelectronics, used as a polymer matrix in organic electronics and flexible displays and in light-sensitive coatings and optical films [

77,

78,

79,

80]. On the other hand, Poly(stearyl methacrylate), PSMA, is a hydrophobic polymer derived from SMA monomer, which contains a long-chain C18 stearyl group. This structure gives PSMA unique properties such as side-chain crystallinity, low glass transition temperature, Tg, hydrophobicity, and self-assembling behavior, making it valuable in hydrophobic coatings for textiles, glass, and metals, biomedical applications and drug delivery systems for nanoparticle coatings and the encapsulation of hydrophobic drugs, adhesives, improving adhesion of hydrophobic films and lubricants, providing low-friction surfaces due to its waxy texture, cosmetics and personal care products [

81,

82,

83,

84].

The synthesis of the block copolymers took place via RAFT polymerization and sequential addition of monomers was employed. The polymers were characterized through size exclusion chromatography, SEC, and NMR spectroscopy. Their thermal properties were studied via Differential Scanning Calorimetry, DSC, and thermogravimetric analysis, TGA. Static, SLS, and dynamic light scattering, DLS, were employed to study the micellization behavior in tetrahydrofuran, THF, which is selective for the PHMA and PSMA blocks [

85] and in aqueous solutions, where PNVP is soluble. The encapsulation of the hydrophobic compound curcumin was studied by UV-spectroscopy. In the past block copolymers of NVP with benzyl methacrylate, BzMA, [

86] and isobornyl methacrylate, IBMA, [

87] were prepared and their self-assembly properties were studied both in THF and in aqueous solutions. In these studies, emphasis was given on the effect of the macromolecular architecture on the micellization behavior, since the block copolymers were compared with the corresponding statistical copolymers. In the present work, the focus is given on the nature of the side ester group of the polymethacrylate block in order to elucidate the effect of the hydrophobicity and the flexibility of this side group to the self-organization process in selective solvents.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

N-Vinyl pyrrolidone (≥97% FLUCA) stabilized with sodium hydroxide as inhibitor was dried overnight over calcium hydride and was distilled prior to use. Tetrahydrofuran, THF was dried over sodium overnight and was distilled just prior to use. Benzene and hexyl methacrylate, HMA, (TCI Chemicals) which was containing methyl hydroquinone, were dried over calcium hydride overnight and were then distilled under vacuum prior the polymerization. Stearyl methacrylate, SMA, was dissolved in THF, and the solution was eluted through an inhibitor remover column (Sigma Aldrich). THF was then evaporated and the received SMA monomer was dried in a vacuum oven. Azobisisobutyronitrile AIBN (98% ACROS) was recrystallized twice from methanol and was then dried under vacuum. The Chain Transfer Agent, CTA, O-ethyl S-(phthalimidylmethyl) xanthate, CTA1, was synthesized following literature protocols [

88,

89]. Phthalimidylmethyl dithiobenzoate, CTA XM, was synthesized according to the following procedure: in a round bottom flask 0.045 mols of carbon disulfide, CS

2, were dissolved in 30 mL of anhydrous THF. A 3M diethyl ether solution of the Grignard reagent phenyl magnesium bromide (14 mL) was added drop wisely at room temperature into the CS

2 solution over a period of 30 min. The resulting red solution was then heated at 40 °C and 0.04 mols of N-(bromomethyl)phthalimide, dissolved in THF were added drop wisely. The final solution was heated at 50 °C for 12 h. Afterwards, 100 mL of chilled water were added and the pure CTA MX was collected through extraction with CHCl

3. The collected solution was dried over MgSO

4. Column chromatography using a mixture of petroleum ether and ethyl acetate (gradient from 8:2 to 7:3) was employed to purify the product. All other reagents and solvents were of commercial grade and were used as received.

2.2. Synthesis of PNVP-b-PHMA and PNVP-b-PSMA Block Copolymers via RAFT Polymerization

The block copolymers were prepared in glass reactors using high vacuum techniques [

90,

91], O–ethyl S–(phthalimidylmethyl) xanthate or phthalimidylmethyl dithiobenzoate, CTA XM, as the CTA and by sequential addition of monomers, starting from the polymerization of NVP in all cases. All the PNVP-

b-PSMA block copolymers and the block copolymers PNVP-

b-PHMA #1 and #2 were prepared with CTA1, whereas the samples PNVP-

b-PHMA #3 and #4 with CTA MX.

A typical polymerization procedure for NVP with final M

n=6.3x10

3 (

Table 3, sample #4) with a molar ratio of [NVP]

0/[CTA MX]

0/[AIBN]

0 = 100/1/0.2 is described as follows: 5g of NVP were polymerized in the presence of 0.0140g CTA MX and 0.0080g AIBN in 0.5 mL of benzene. The polymerization mixture was degassed employing three freeze-thaw pump cycles. The reactor was flame-sealed and placed in a preheated oil-bath at 60 °C for 12h. The polymerization reaction was terminated by removing the reactor from the oil-bath and cooling the mixture in cold water. The reactor was then opened to the atmosphere. The homopolymer was then precipitated in an excess of diethyl ether. The polymer was redissolved and reprecipitated three times to ensure the removal of any residual unreacted NVP monomer. The sample was subsequently dried overnight in a vacuum oven at 50 °C to remove any trace of solvent. The conversions for all homopolymers were near quantitative when CTA1 was employed and about 65% when CTA MX was used.

The block copolymerization reactions were performed in dioxane solutions at 80 °C for 72 h in glass reactors under high vacuum conditions. Quantities of the PNVP homopolymer, serving as the macro-CTA, the HMA monomer, the AIBN radical initiator and the dioxane solvent are reported in

Table 1. The corresponding quantities for the block copolymers with PSMA blocks are given in

Table 2. According to the general procedure, the polymerization mixture was subjected to three freeze-thaw pump cycles in order to eliminate the oxygen from the polymerization flask. The polymerization was terminated by removing the reactor from the oil-bath and cooling the mixture in cold water. The reactor was then opened so as to expose the mixture to air. The polymer was precipitated in an excess of methanol. The crude product was dissolved in THF and reprecipitated in methanol. This procedure was repeated three times in order to ensure the removal of any unreacted methacrylate monomer residues. Afterwards, the polymers were dried overnight in a vacuum oven at 50 °C to remove any residual solvent. The block copolymers PNVP-

b-PHMA #1 and #4 along with copolymer PNVP-

b-PSMA #1 were further purified from the excess PNVP block that remained in the final product by fractionation using chloroform/methanol as the solvent/non-solvent system.

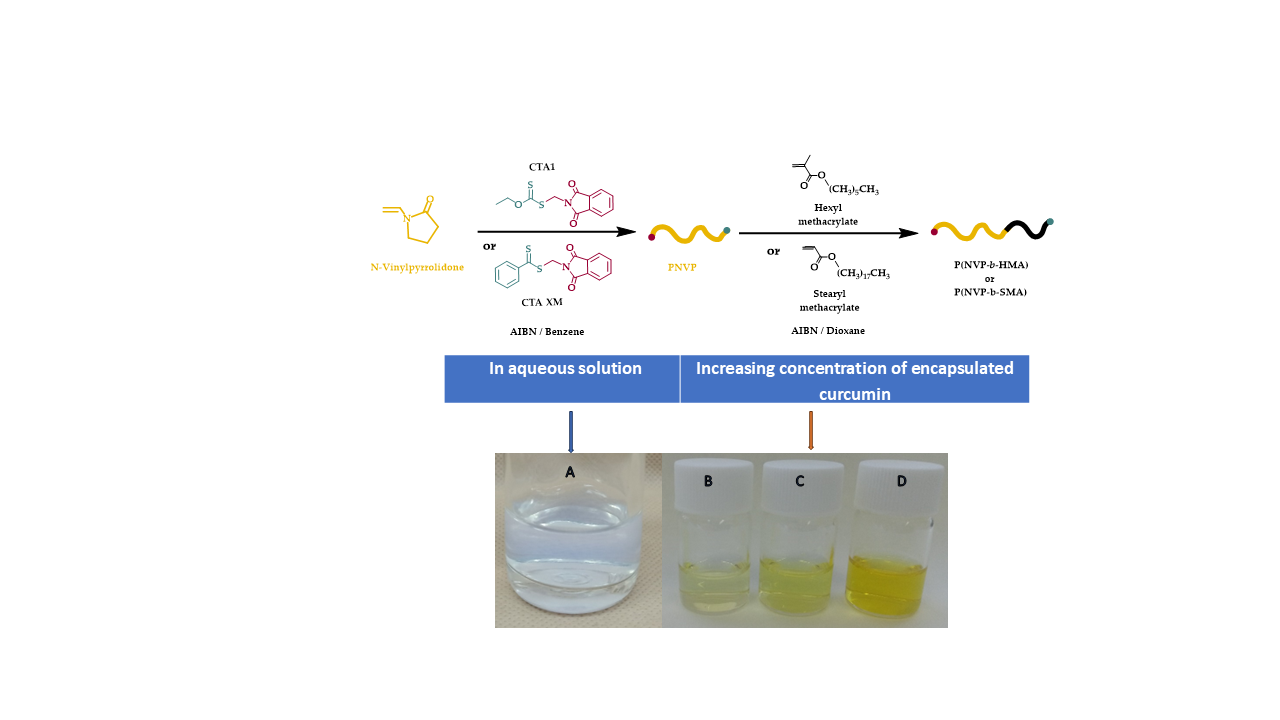

2.3. Encapsulation Process

The encapsulation studies were conducted preparing different solutions in THF, one for the block copolymer and one for the hydrophobic drug curcumin. The concentrations for both types of block copolymers, containing either PHMA or PSMA as the hydrophobic block, were close to 5x10

−4 g/mL. The exact concentration values are given in the Supporting Information Section, SIS (

Tables S1 and S2). The solutions were allowed to stand overnight for complete dissolution with periodic agitation. After that, the block copolymer solution was split into four separate vials, and a different amount of the curcumin stock solution was added to each one. After efficient mixing, 5 mL of extra pure water was added to the respective vials. THF was then allowed to evaporate gradually for several hours by heating at 65 °C. The final concentrations of curcumin were in the range of 10

−6 g/mL to 10

−5 g/mL. The exact values for all the block copolymers are given in the SIS. The final solutions had a yellow color and were stable for several weeks without any signal of precipitation.

2.4. Characterization Techniques

The molecular weight (Mw) as well as the molecular weight distribution, Ð= Mw/Mn, were determined by size exclusion chromatography, SEC, employing a modular instrument consisting of a Waters model 510 pump, U6K sample injector, 401 differential refractometer and a set of 5 μ-Styragel columns with a continuous porosity range from 500 to 106 Å. The carrier solvent was CHCl3 and the flow rate 1 mL/min. The system was calibrated using nine Polystyrene standards with molecular weights in the range of 970–600,000.

The composition of the copolymers was determined from their 1H NMR spectra, which were recorded in chloroform-d at 30°C with a 400 MHz Bruker Avance Neo spectrometer (Billerica, MA, USA).

For UV/Vis measurements, a Perkin Elmer Lamda 650 spectrophotometer was used from 250 to 800 nm, at room temperature, using a quartz cell of 3 mL.

The Tg values of the copolymers were determined by a 2910 Modulated DSC Model from TA Instruments. The samples were heated under nitrogen atmosphere at a rate of 10 °C/min from -30 °C up to 220 °C. The second heating results were obtained in all cases.

The thermal stability of the copolymers was studied by thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) employing a Q50 TGA model from TA Instruments. The samples were placed in a platinum pan and heated from ambient temperatures to 600 °C in a 60 mL/min flow of nitrogen at heating rates of 3, 5, 7, 10, 15 and 20 °C/min.

Refractive index increments, dn/dc, at 25 °C were measured with a Chromatix KMX-16 (Milton Roy, LDC Division, Riviera Beach, FL, USA) refractometer operating at 633 nm and calibrated with aqueous NaCl solutions.

Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) measurements were conducted with a Brookhaven Instruments (Holtsville, NY, USA) Bl-200SM Research Goniometer System (Holtsville, NY, USA) operating at λ = 640 nm and with 40 mW power. Correlation functions were analyzed by the cumulant method and Contin software (Holtsville, NY, USA) [

92]. The correlation function was collected at 45, 90, and 135°, at 25 °C.

The angular dependence of the ratio Γ/q

2, where Γ is the decay rate of the correlation function and q is the scattering vector, was not very important for most of the micellar solutions. In these cases, apparent translational diffusion coefficients at zero concentration, D

o,app, were measured using Equation (1):

where

kD is the coefficient of the concentration dependence of the diffusion coefficient. Apparent hydrodynamic radii at infinite dilutions,

Rh, were calculated with the aid of the Stokes–Einstein Equation (2):

where

k is the Boltzmann’s constant,

T is the absolute temperature and

ηs is the viscosity of the solvent.

3. Results and Discussion

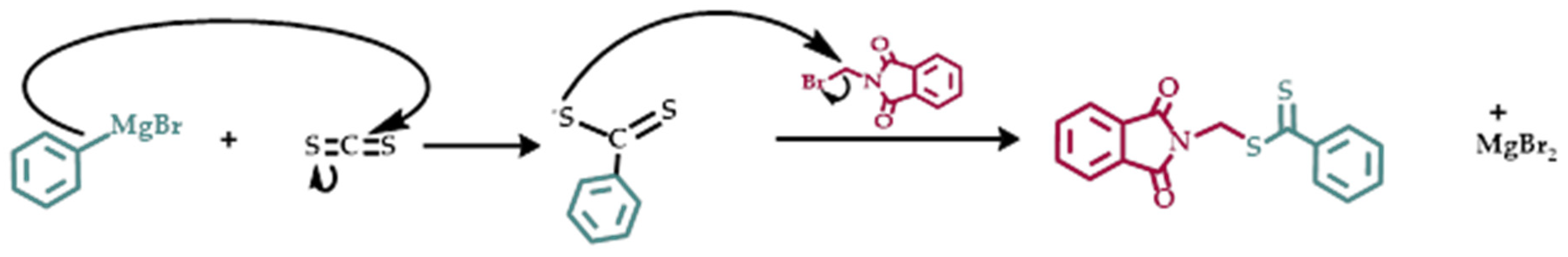

3.1. Synthesis of Phthalimidylmethyl Dithiobenzoate, CTA XM

It is well known that in RAFT polymerization monomers are divided in two distinct categories, the more activated monomers, MAMs, and the less activated monomers, LAMS, according to their ability to stabilize radicals [

75,

76]. NVP belongs to the family of LAMS, whereas HMA and SMA to MAMs. The polymerization of these monomers require different CTAs with variable ability to stabilize radicals. Therefore, CTA1 is a well-known xanthate, which has been frequenty employed for the polymerization of LAMs. The CTA XM has not been reposrted so far in the literature. The synthesis was conducted through the reaction given in

Scheme 1. The crude product was purified through column chromatography and the yield was about 80%. The synthesis was verified by NMR spectroscopy. The

1H NMR specrum is given in the SIS (

Figure S1) confirming the synthesis of the desired product.

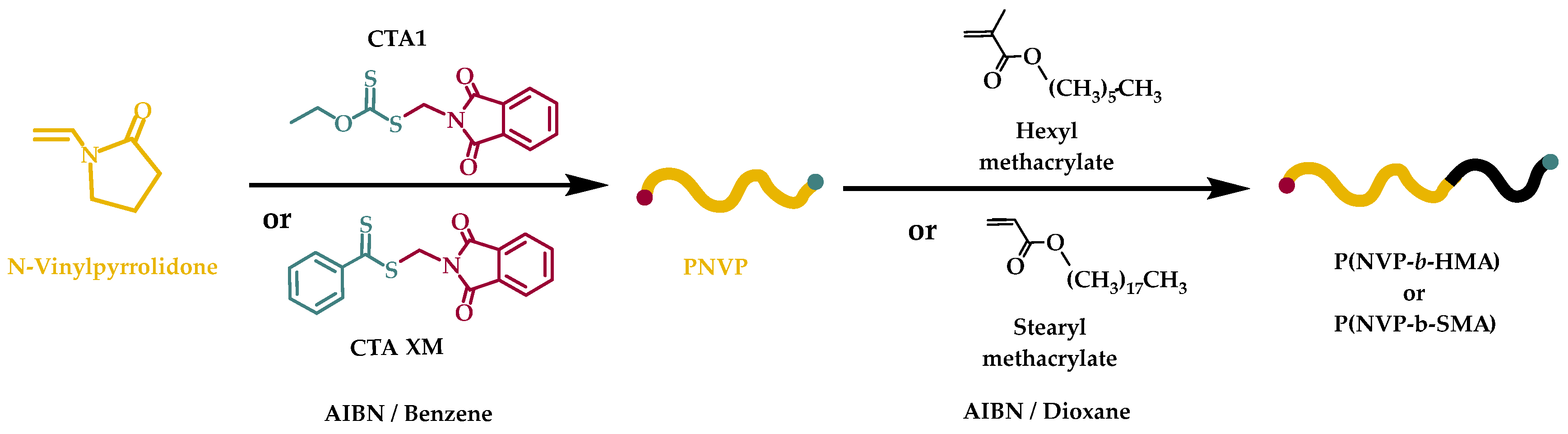

3.2. Synthesis of the Block Copolymers PNVP-b-PHMA and PNVP-b-PSMA

The RAFT methodology was adopted for the synthesis of the PNVP-b-PHMA and PNVP-b-PSMA block copolymers. The procedure is not a trivial task, since NVP and methacrylates belong to different families of monomers. On the one hand, NVP is considered to be a LAM, since it is not possible to stabilize radicals in its molecule. On the other hand, methacrylates have the ability to stabilize radicals and therefore, belong to the family of MAMs. This differentiation is crucial, since there are specific groups of CTAs that are suitable for each category of monomers. For example, xanthates and dithiocarbamates can be efficiently employed for the polymerization of LAMs, whereas dithioesters and trithiocarbonates for the polymerization of MAMs. There is also a family of CTAs that are considered to be universal, since they are efficient for both MAMs and LAMs and a family of switchable CTAs that may lead to the same results after simple chemical transformation, such as protonation in acidic environment. The combination of both MAMs and LAMs in the same copolymeric structure is not a common procedure requiring a special treatment, such as the use of universal or switchable CTAs.

Previously, the synthesis of block copolymers between PNVP and either poly(benzyl methacrylate), PBzMA [

86], or poly(isobornyl methacrylate), PIBMA [

87], has been reported by RAFT copolymerization. In the case of the PIBMA-

b-PNVP block copolymers, 2-cyanoprop-2-yl-1-dithionaphthalene (CPDN) was employed as CTA providing very good control over the RAFT polymerization of MAMs, such as IBMA. However, for LAMs it is not efficient providing poor control. However, it was found that using 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoro-2-propanol (HFIP) as the solvent, the polymerization of NVP, which is a typical LAM, can be promoted in a rather controlled way leading to well-defined block copolymers. The block copolymers with PBzMA were synthesized by sequential addition of monomers starting from the polymerization of NVP. O-ethyl S-(phthalimidylmethyl) xanthate was employed as the CTA, as a universal CTA. The specific CTA provides excellent control for the RAFT polymerization of NVP and LAMs in general. Subsequent polymerization of BzMA from the originally prepared PNVP macro-CTA afforded the desired block copolymer.

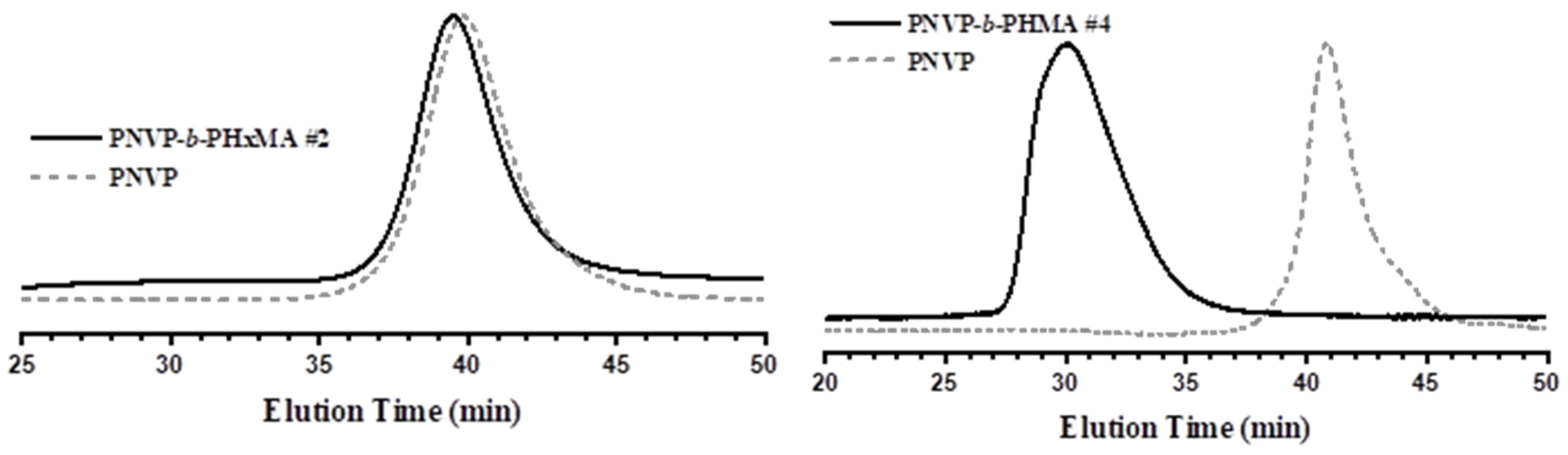

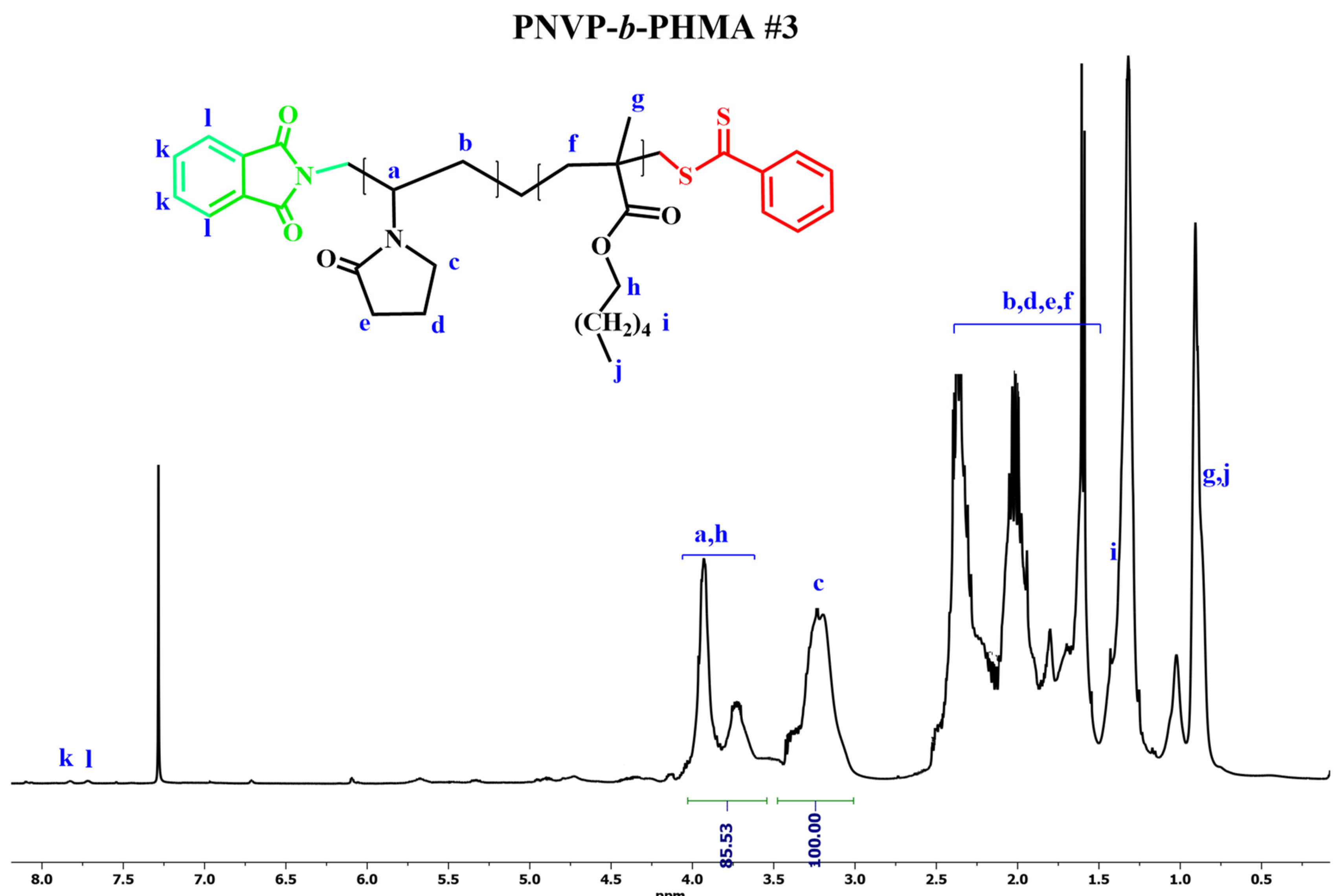

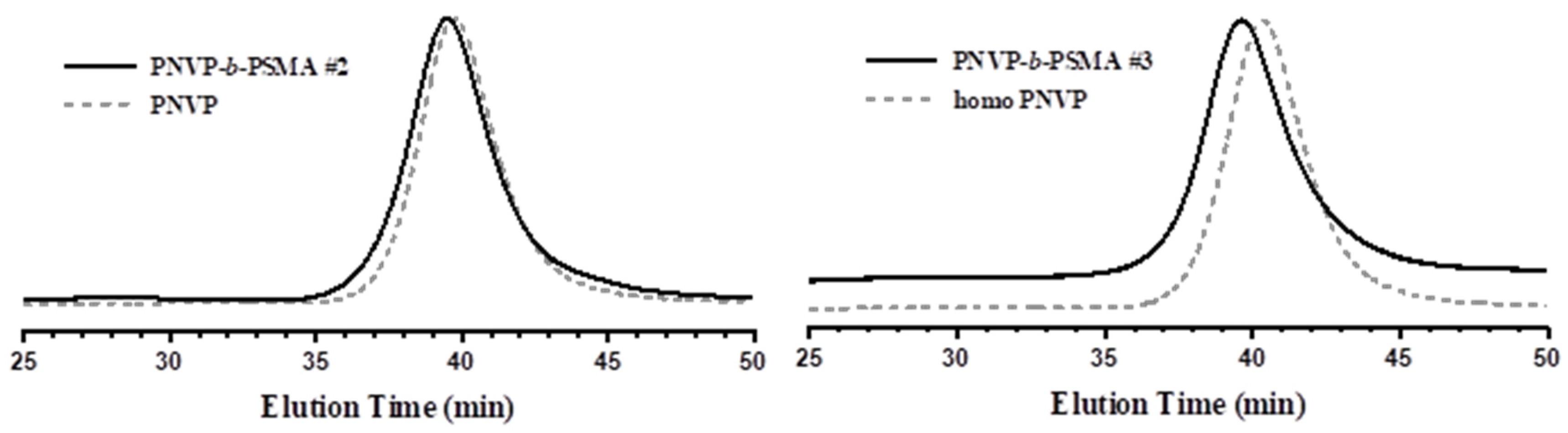

This procedure was also employed in the current work. The reaction sequence is given in

Scheme 2, whereas the molecular characteristics of the synthesized block copolymers in

Table 3 and

Table 4 for the PNVP-

b-PHMA and PNVP-

b-PSMA samples respectively. The reaction sequence was monitored by SEC and

1H NMR spectroscopy. Characteristic examples are given in

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4, whereas data for the remaining samples are given in the SIS (

Figures S2-S8). The polymerization of NVP was well controlled using CTA1, as was evidenced by the relatively low dispersity values (less than 1.30) and the symmetric peaks from SEC analysis. As was mentioned earlier, CTA1 and therefore, the corresponding PNVP macro-CTA is not very efficient for the polymerization of methacrylates. This event has two consequences for the obtained copolymers: the first has to do with the SEC traces. They are symmetric without important tailing effects but in certain cases the crude product gave a bimodal distribution, indicating either the presence of termination reactions during the polymerization of the methacrylate monomer or a non-very efficient crossover reaction from the first PNVP block to the final block copolymer.

Table 3.

Molecular characteristics of block copolymers PNVP-b-PHMA.

Table 3.

Molecular characteristics of block copolymers PNVP-b-PHMA.

| |

macro CTA

(PNVP) * |

block

copolymers * |

NVP

|

HMA

|

| Sample |

Mn 103

(Daltons) |

Ð |

Mn 103 (Daltons) |

Ð |

% mol** |

% mol** |

| PNVP-b-PHMA #1 |

29.8 |

1.29 |

36 |

1.26 |

87 |

13 |

| PNVP-b-PHMA #2 |

10.6 |

1.26 |

13 |

1.27 |

84 |

16 |

| PNVP-b-PHMA #3 |

27.0 |

1.60 |

32 |

1.68 |

74 |

26 |

| PNVP-b-PHMA #4 |

6.3 |

1.34 |

130 |

1.53 |

5 |

95 |

Therefore, the block copolymers PNVP-b-PHMA #1 and PNVP-b-PSMA #1 revealed the presence of excess remaining PNVP block from the SEC analysis. The samples were purified from the excess PNVP block that remained in the final product by fractionation using chloroform/methanol as the solvent/non-solvent system. The second consequence of using CTA1 for these experiments is that in order to minimize the broadening of the dispersity of the copolymers the yield of polymerization was not allowed to reach high levels. Usually, it was lower than 60% in all cases.

For the synthesis of the copolymers PNVP-b-PHMA #3 and #4 the newly synthesized CTA XM was employed. The specific CTA is in principle suitable for the polymerization of MAMs. Consequently, the dispersity values for the PNVP blocks were found to be higher than in the other cases and the yield was not quantitative. In addition, the SEC traces were not always symmetric, meaning that it is possible to have a substantial amount of the PNVP chains without having the desired end-groups coming from the CTA XM reagent. For this reason, the sample PNVP-b-PHMA #4 had to be purified by fractionation, as earlier reported. However, the polymerization of the second methacrylate block was well-controlled giving the advantage to synthesize copolymers with higher methacrylate contents.

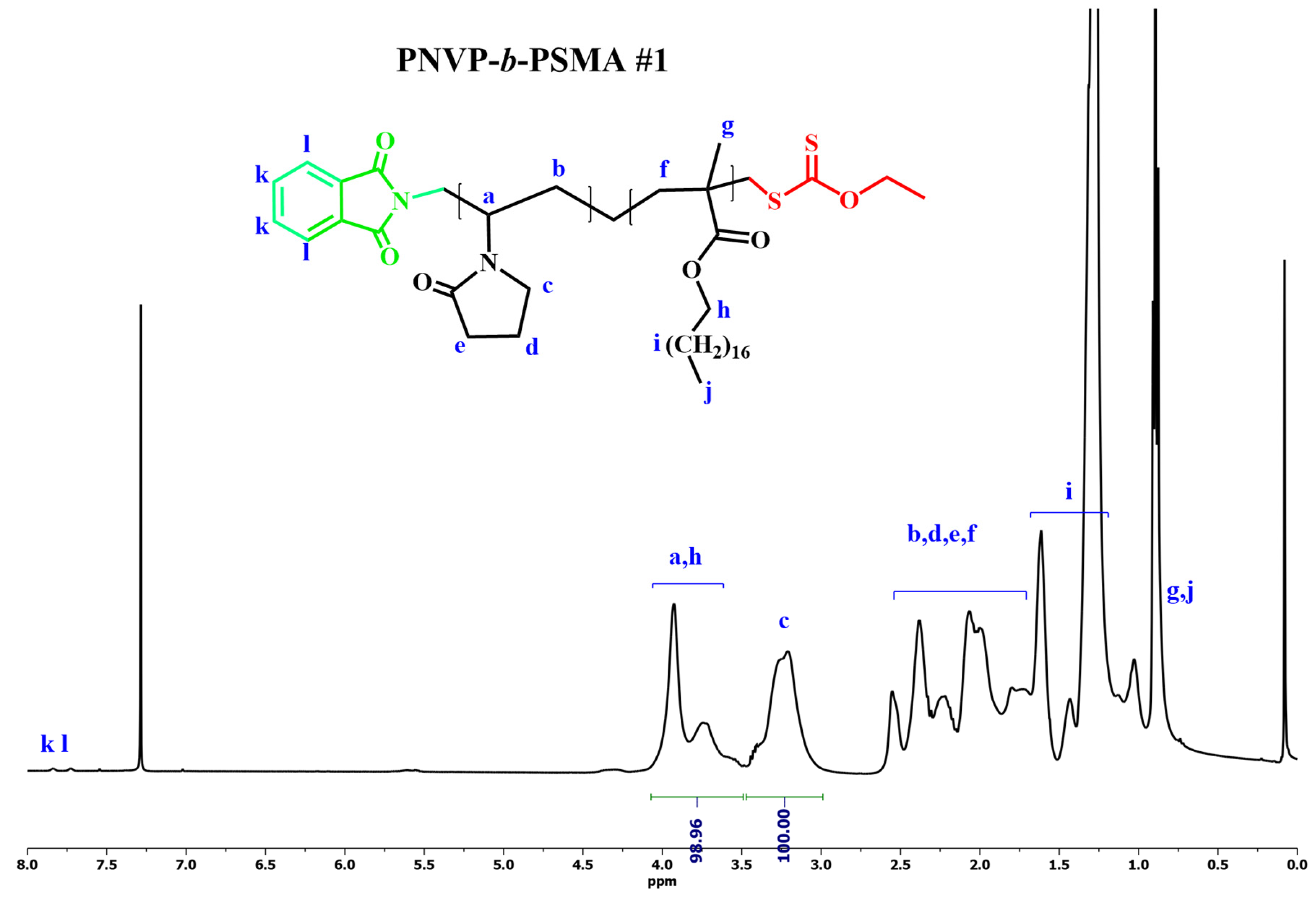

The synthesis of the desired products was confirmed by NMR spectroscopy. The signals of all the protons were traced in the spectra. It was possible to calculate the composition of the copolymers using the signals of the methine proton -CH of the backbone and the methylene protons -CH2 of the pyrrolidone ring that are adjacent to the nitrogen atom, along with the -COO-CH2 methylene protons of the ester group of the methacrylate monomer.

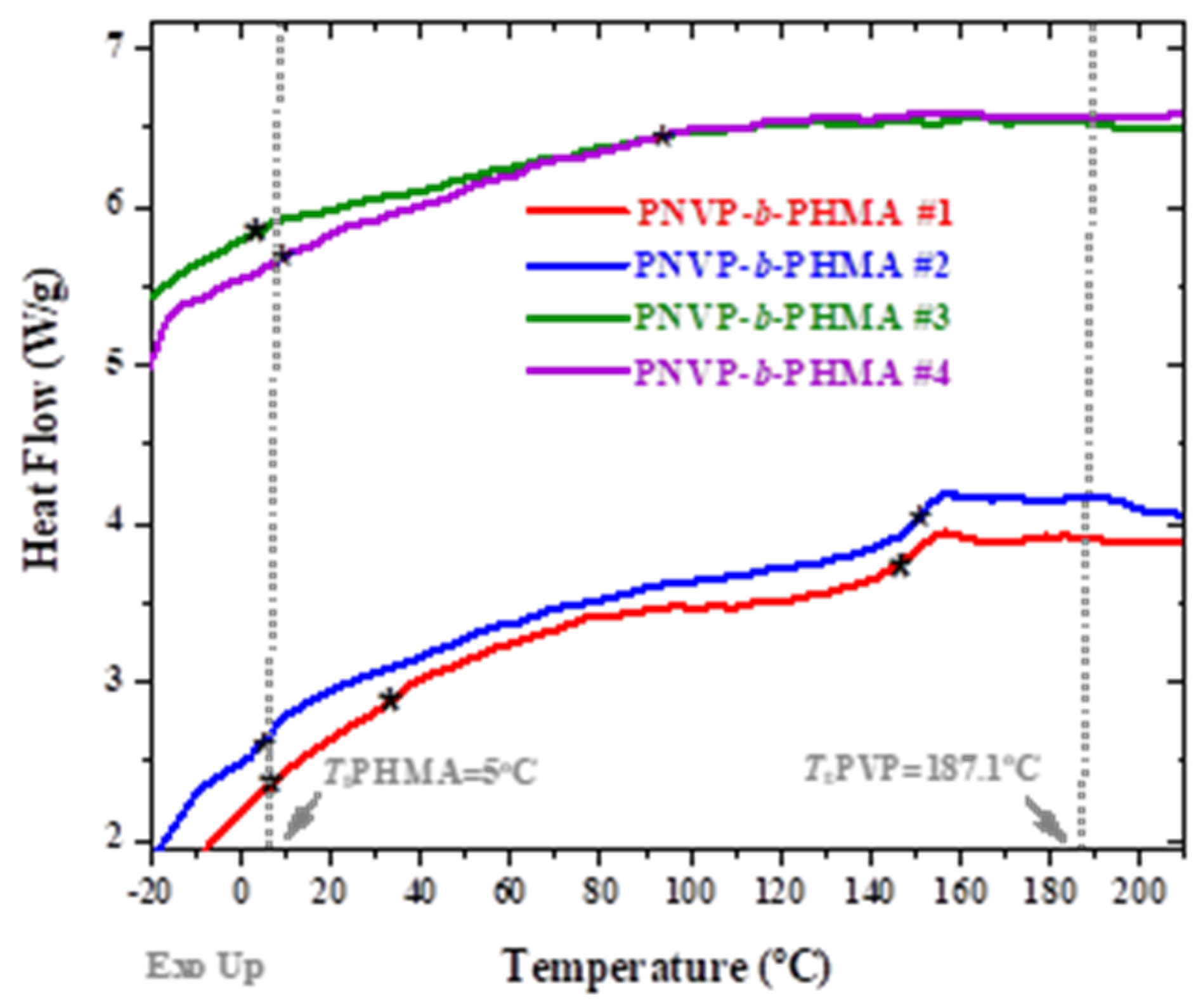

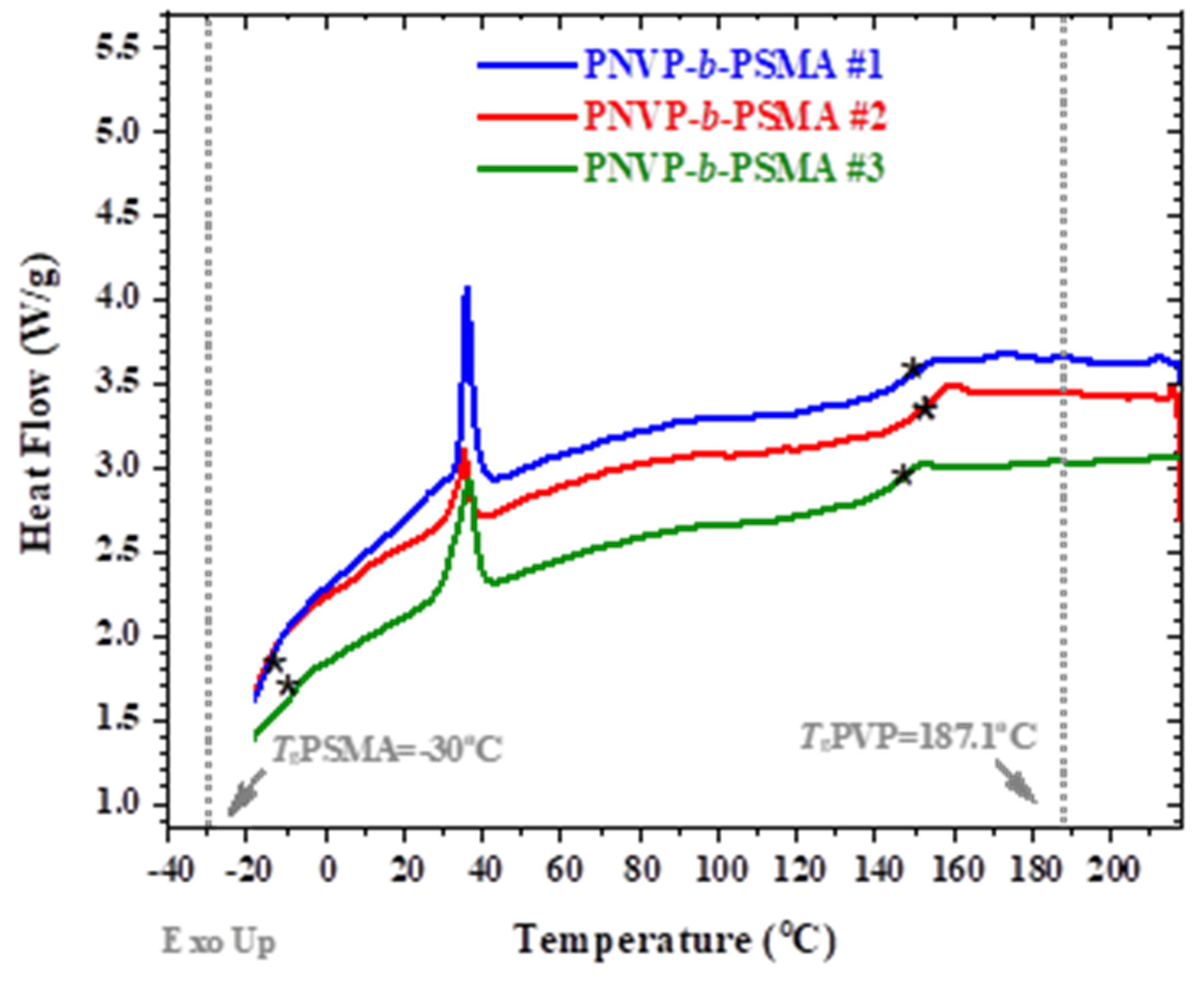

3.2. Thermal Properties

The thermal properties of the two families of copolymers were studied by DSC and TGA measurements. The data from the DSC experiments are given in

Table 5 and

Table 6 and

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 for the PNVP-b-PHMA and PNVP-b-PSMA block copolymers respectively.

Both PNVP and PHMA homopolymers are amorphous with Tg values equal to 187.1 [

93] and -5

°C [

94,

95] respectively. The lower value of PHMA is attributed to the flexible alkyl side chain of the polymethacrylate chains. The block copolymers showed two thermal transitions indicating that there is microphase separation in the system. However, the obtained Tg values are shifted from the corresponding values of the pure homopolymers, thus revealing the presence of partial mixing in the system. Only the sample #1 showed an intermediate weak transition due to the partial mixing of the two phases. This result is the consequence of the rather low molecular weights of the respective blocks and the obviously not very high value of the χ parameter of Flory, which does not allow phase separation in low molecular weight blocks.

The presence of the large alkyl side chain of the ester group in PSMA leads to side-chain crystallization and therefore the homopolymer is semi-crystalline showing a melting temperature at 34

°C and a glass transition temperature at -30

°C [

96,

97,

98]. The PNVP-b-PSMA block copolymers are also microphase separated providing on heating a first order transition attributed to the melting of the crystalline domains of the polymethacrylate block and two glass transitions from the amorphous regions of the respective blocks. The Tm values were slightly increased compared to the homopolymer, since the glassy phase of PNVP offers further stabilization to the PSMA crystalline regions. On the contrary, the enthalpy of melting and consequently the degree of crystallization, were reduced compared to the homopolymer. This behaviour is rather common in amorphous/semi-crystalline block copolymers indicating that the amorphous blocks prevent the organization of the semi-crystalline domains [

98,

99].The low Tg values were shifted to higher temperatures, whereas the high Tg values to lower, indicating a partial mixing of the two phases, as discussed previously.

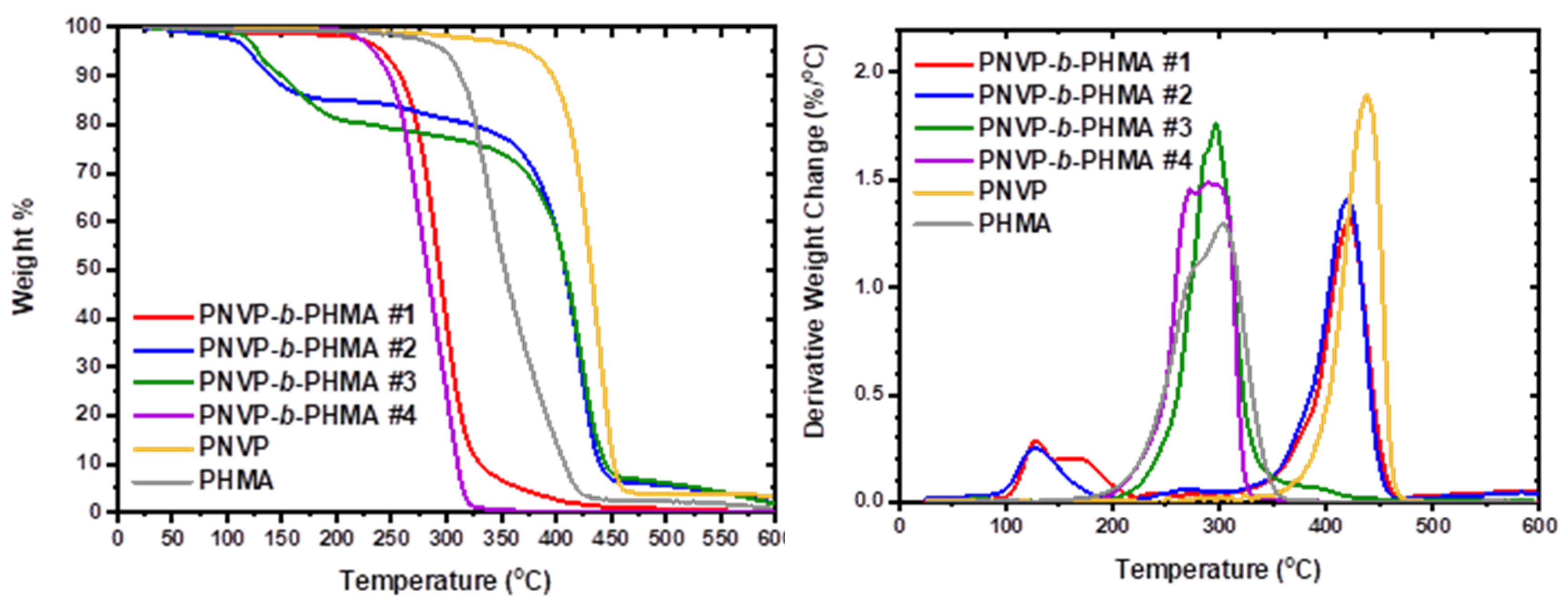

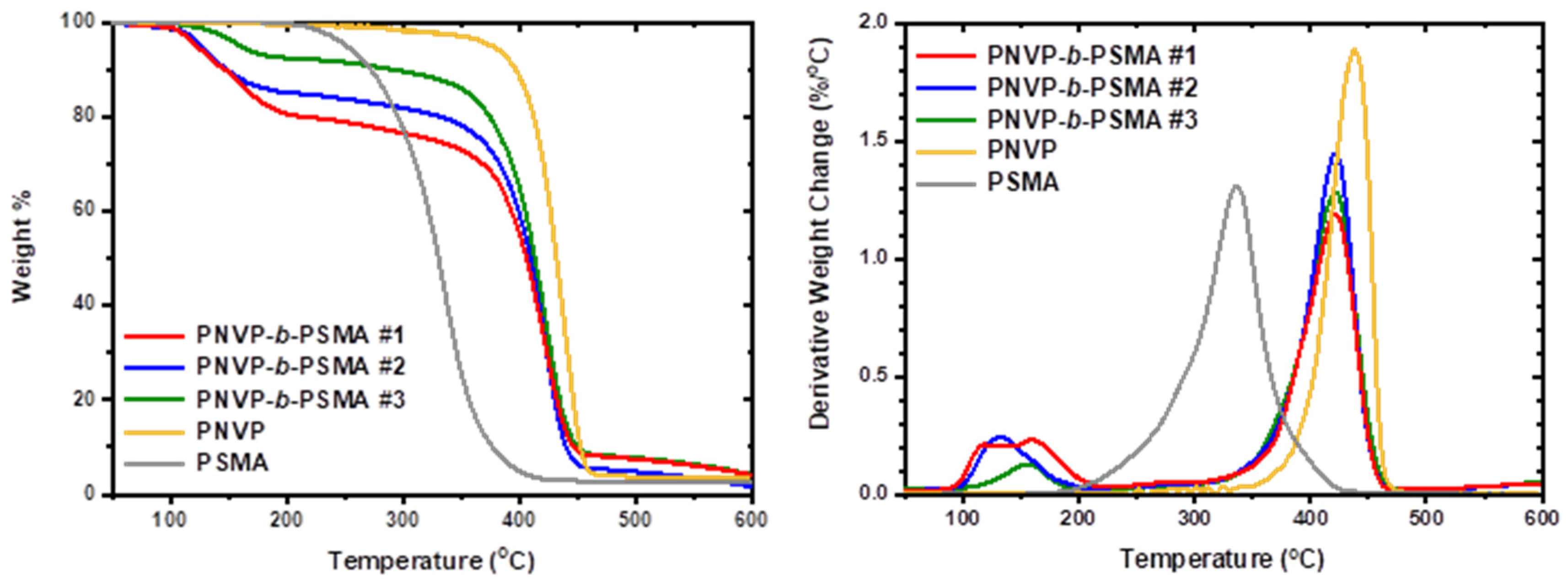

TGA measurements were employed to study the thermal stability of the respective homopolymers and block copolymers. The experimental results are shown in

Table 7 and

Table 8, whereas the TGA and DTG thermograms for all samples are provided in

Figure 7 and

Figure 8.

As was found for other polymethacrylates, PNVP is much more thermally stable than PHMA [

100]. DTG analysis revealed that a single decomposition peak is observed for the PNVP homopolymer in the range of 348 and 484 °C with a maximum rate of degradation at 438 °C. Similar analysis for PHMA showed that the decomposition pattern is a single peak with a maximum rate at 299 °C, having a shoulder at lower temperatures. The range of decomposition is between 191 and 357 °C. This is direct evidence that the degradation of the side ester group and the main chain of the polymethacrylate take place at similar ranges of temperatures.

A much more complex degradation profile was found for PBzMA [

86] and especially for PIBMA [

87], where a multistep procedure was traced, indicating that the nature of the ester group of polymethacrylates plays a crucial role in the determination of the thermal stability of the polymer and the exact mechanism of thermal decomposition. The block copolymers combine the characteristics of the respective homopolymers. The sample PNVP-b-PHMA #4 with the highest composition in PHMA behaves more or less as the respective homopolymer with a single decomposition peak at 292

°C. The sample #3 with 26% mole of HMA has a maximum rate of decomposition at a temperature of 297

°C, which is slightly higher than that of PHMA homopolymer. However, the range of decomposition is broader compared to the homopolymer and sample #4, as a result of the presence of the more thermally stable PNVP block. The block copolymers #1 and #2 with much higher compositions in PNVP have a single degradation peak, which is closer to that of the PNVP block, although relatively lower (421

°C for both blocks compared to 438

°C for the homopolymer).

On the other hand, PSMA is thermally more stable than PHMA, due to the side chain crystallization of the long alkyl side ester groups. The range of decomposition temperatures is very broad, certainly higher in PSMA rather than in PHMA, showing that the possible mechanism of degradtion is similar but the bulky and crystalline forming steryl group offers more thatmal stability to the hopolymer. The block copolymers PNVP-b-PSMA, rich in NVP have a thermal degradation behaviour similar to that of PNVP, showing a single decomposition peak having a maximum in the range 419 to 424 °C. These temperatures are slightly lower than that of the pure PNVP homopolymer, due to the presence of the less thermally stable PSMA block.

For both types of block copolymers minor peaks at low temperatures, slightly higher than 100 °C are attributed to humidity in the samples and to remaining traces of organic solvents from the synthetic procedure.

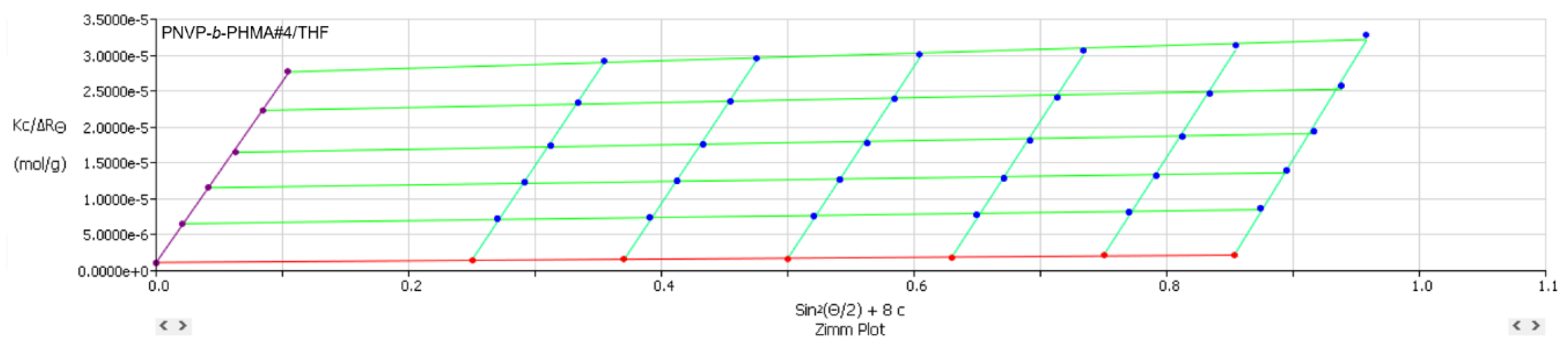

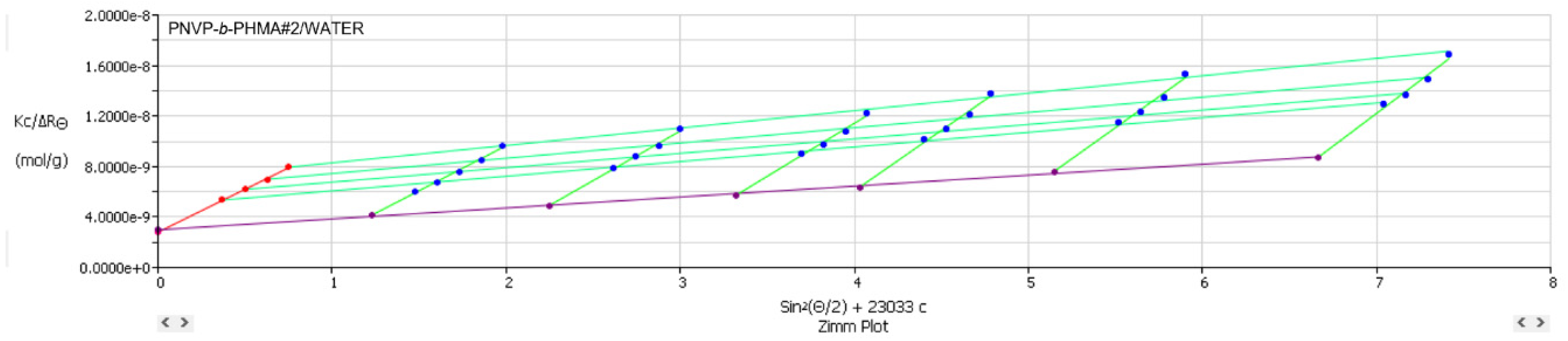

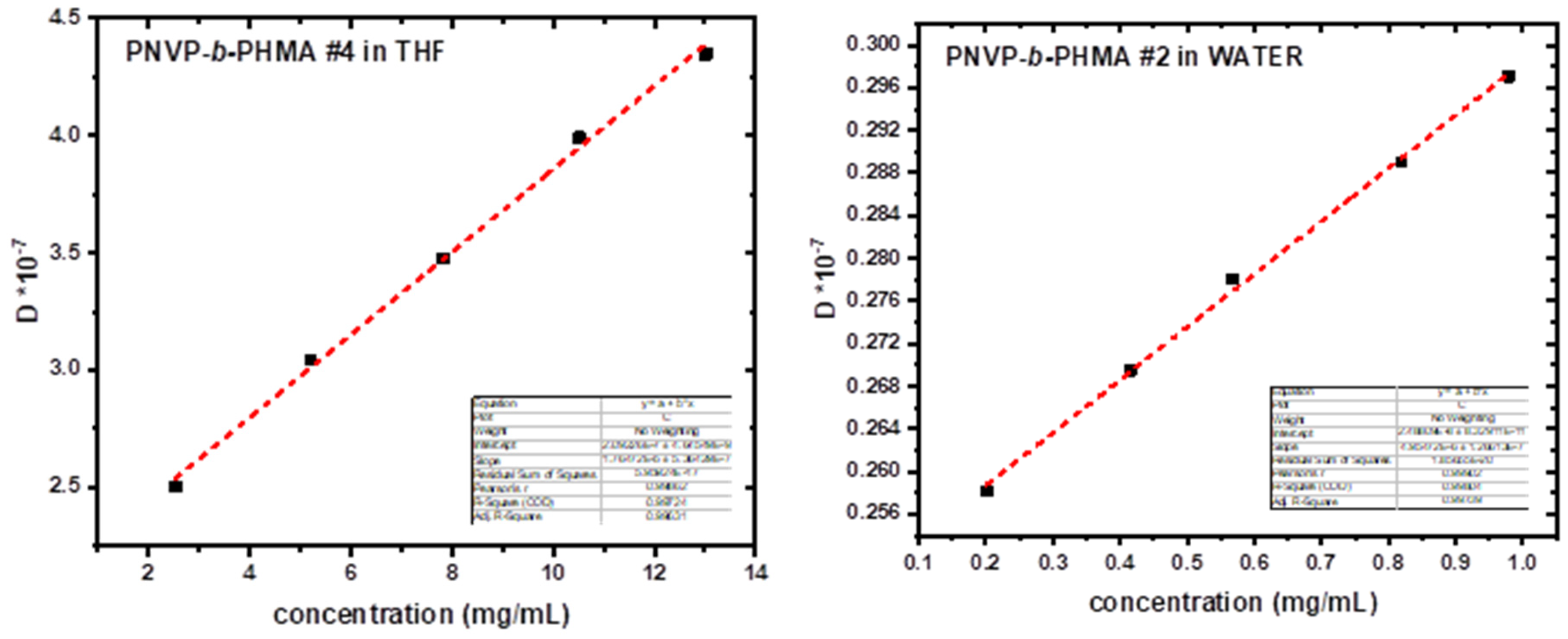

3.3. Self-Assembly Behavior of the PNVP-b-PHMA Block Copolymers in THF and Aqueous Solutions

The self-assembly behaviour of the PNVP-

b-PHMA block copolymers was studied in CHCl

3, which is a common good solvent for both components, in THF, which is a selective solvent for the PHMA blocks and in aqueous solutions, since water is a selective solvent for the PNVP blocks. Static, SLS, and Dynamic Light Scattering, DLS, techniques were employed to investigate the aggregation of the block copolymers. The SLS data of the PNVP-

b-PHMA block copolymers in both the common good and the selective solvents are reported in

Table 9, whereas the DLS results in

Table 10. Characteristic Zimm plots from the SLS measurements and diffusion coefficient, D, vs concentration, c, plots from DLS studies are given in

Figure 9,

Figure 10 and

Figure 11. In previous studies, regarding the association behaviour of block copolymers bearing PNVP blocks it was shown that THF, although a selective solvent for PNVP, is not able to promote strong aggregation effects leading to low degrees of association, N

w. Especially, for the PNVP-

b-PBzMA block copolymers the almost exclusive formation of unimolecular micelles was concluded [

86]. In the case of the PNVP-

b-PIBMA blocks slightly higher N

w values were obtained [

87]. Similar results were drawn in the present study with the PNVP-

b-PHMA block copolymers in THF. The aggregation numbers are very low (N

w<10) indicating the formation of unimolecular micelles or small spherical micelles. It is important to mention that the copolymers with the highest PNVP content (PNVP-

b-PHMA samples #1, #2 and #3) have slightly lower N

w values than the sample #4, which contains only 5% mol of PNVP. In this case compact star-like micelles prevail in THF solutions. The low second virial coefficient values, A

2, in THF solutions confirm the formation of unimolecular or low association number micelles. Therefore, it can be concluded that the ability of THF to form large associates in these PNVP based block copolymers is not very pronounced.

These results were further confirmed by the DLS measurements. CONTIN analysis revealed the presence of single population in THF solutions. The absence of angular dependence verifies the formation of spherical structures, which are relatively polydisperse, since the polydispersity factor μ

2/Γ

2, μ

2 being the second moment of the cumulant analysis and Γ the decay rate of the correlation function, were higher than 0.1 for all samples. These values were comparable for both the CHCl

3 and the THF solutions. Characteristic plots are given in the SIS (

Figures S9-S10). The R

h values in THF were lower than those measured in CHCl

3 for all samples supporting the conclusion derived from the SLS measurements regarding the formation of unimolecular or small and compact aggregates in THF. These findings were further confirmed by the plots D vs c, which were linear with small k

D values. In addition, the k

D values in THF were lower than those in CHCl

3. This result is reasonable, due to the relationship between k

D and A

2 through the following equation:

where M is the molecular weight, k

f the coefficient of the concentration dependence of the friction coefficient and u the partial specific volume of the polymer. The low values of A

2 in THF imply low k

D values as well.

A completely different behaviour was obtained in aqueous solutions. The data from SLS and DLS measurements are given in

Table 9 and

Table 10 respectively. The sample PNVP-

b-PHMA #4, due to the very low PNVP content, was not soluble in water despite the various protocols employed for the preparation of the solutions. In order to achieve equilibrium micellar structures, the copolymers were initially dissolved in THF, where, as previously discussed, unimolecular micelles or supramolecular structures with very low aggregation numbers exist. Water was then gradually added followed by the heating of the mixture at 50 °C leading to the re-organization of the supramolecular entities. Subsequent further heating at 60 °C allowed the gradual evaporation of the volatile THF and thus to the formation of equilibrium micellar structures in aqueous environment.

Very high aggregation numbers were measured by SLS measurements, despite the fact that the content of the copolymers in the soluble PNVP was vey high. Judging from these strong association phenomena it is reasonable to expect the very low A2 values that were measured. These values are an order of magnitude lower than those measured in THF, where also association is effective. In addition, very large radii of gyration, Rg, values were measured in aqueous solutions, much higher than in THF solutions. Comparison of these Rg values with the huge aggregation numbers leads to the conclusion that very compact supramolecular structures exist in aqueous solutions.

Further elucidation of this situation was offered by DLS measurements. Characteristic D vs c plots are given in

Figure 11. CONTIN analysis revealed the presence of single populations of associates in all concentrations and for all the samples with much higher R

ho values compared to those measured in CHCl

3 and THF. Representative CONTIN plots are given in

Figure S11. These populations have lower polydispersity factor (μ

2/Γ

2<0.2) values compared to the corresponding values in the common good solvent CHCl

3 and in THF. Furthermore, no angular dependence was found and the populations were thermally stable up to 60 °C without any signal of disassociation or formation of higher dimension supramolecular structures. Finally, the R

g/R

h ratios coming from SLS and DLS measurements were close to unity for all samples examined in aqueous solutions. All these findings point to the same conclusion that thermally stable, spherical and compact micelles are present in water. The k

D values were much higher in water than in THF for the aggregating systems, due to the extremely high molecular weight of the micellar entities.

Comparison of the micellization behaviour of the present system with the corresponding PNVP-

b-PBzMA [

86] and PNVP-

b-PIBMA block copolymer micelles [

87] in THF and water reveals the presence of both similarities and differences. In THF, a solvent selective for the polymethacrylate block the behaviour is more or less the same, indicating that the core forming PNVP block is responsible for the experimental results and that the exact chemical nature of the corona forming polymethacrylate block does not play a crucial role. Unimolecular or small spherical micelles having very low aggregation numbers are formed in THF. The situation was different in aqueous solutions. Polymethacrylates are the core forming blocks and therefore the nature of the side ester group has a significant impact on the association behaviour. In the case of the PNVP-

b-PIBMA block copolymers equilibrium between micelles and clusters is established. On the contrary, compact, spherical micelles of relatively low polydispersity values are formed in the other cases. The aggregation numbers of the micelles formed from the PNVP-

b-PBzMA block copolymers were lower than those measured for the respective PNVP-

b-PHMA block copolymers, despite the fact that both the molecular weight and the content of the PBzMA component were in most samples much higher than the corresponding PHMA. This indicates that the more flexible linear n-hexyl group of PHMA facilitates the accommodation of the polymethacrylate chains to larger and compact cores leading to the formation of micelles with very high N

w values.

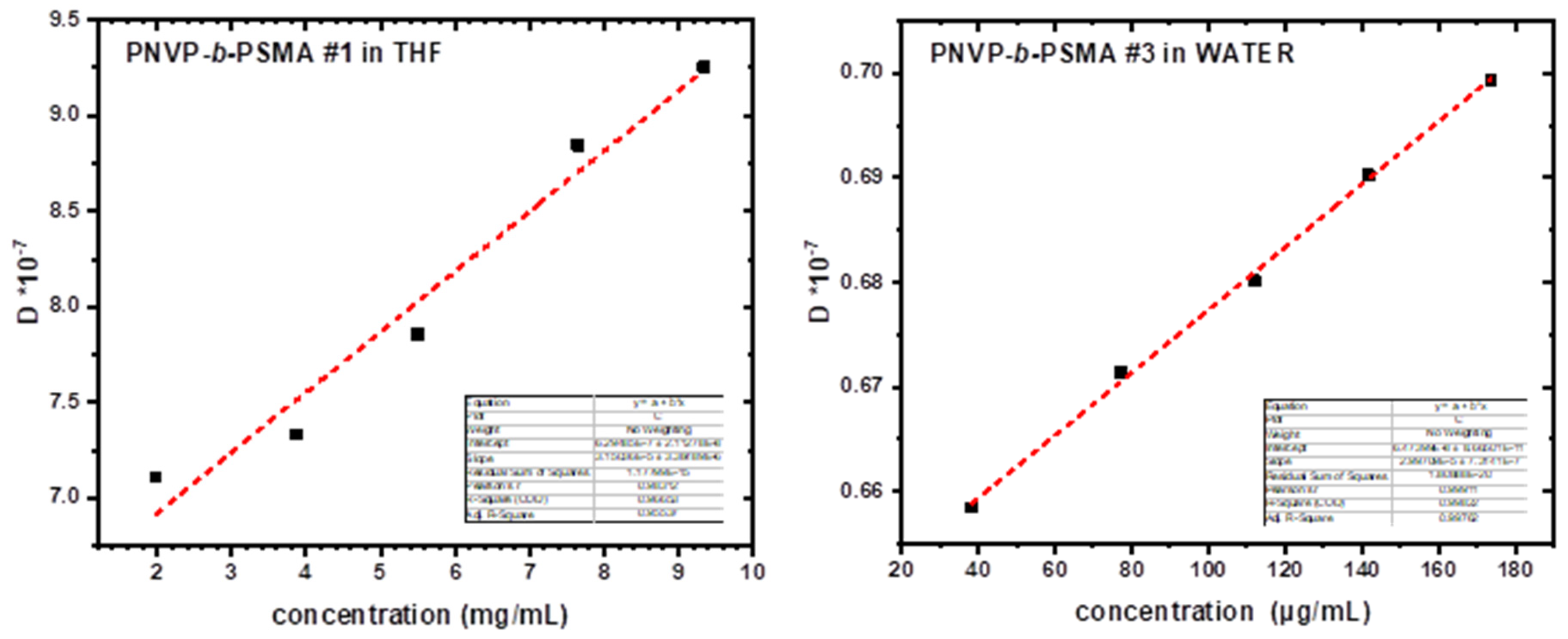

3.4. Self-Assembly Behavior of the PNVP-b-PSMA Block Copolymers in THF and Aqueous Solutions

The micellization properties of the PNVP-

b-PSMA block copolymers were studied in THF and aqueous solutions employing SLS and DLS measurements. The experimental results are provided in

Table 11 and

Table 12, whereas representative plots in

Figure 12. The general picture was similar to that mentioned for the PNVP-

b-PHMA block copolymers, since the chemical nature of both the hydrophilic and the hydrophobic compounds are almost identical. The only difference refers to the size of the ester group of the polymethacrylate block. The stearyl group of PSMA is more hydrophobic than the hexyl group of PHMA. This event is expected to further promote the association of the PNVP-

b-PSMA block copolymers in aqueous solutions. However, the stearyl group is bulkier than the hexyl group, thus preventing the organization of extended cores and leading to lower aggregation numbers. The experimental findings from SLS measurements revealed that the steric hindrance effects prevail and the N

w values for the PSMA containing copolymers, although large enough, are lower than those obtained for both PNVP-

b-PHMA and PNVP-

b-PBzMA block copolymers. Therefore, the manipulation of the chemical structure of the ester group of the polymethacrylate chain may alter the self-assembly behaviour.

In THF only unimolecular or small and compact aggregates were formed having R

h values lower than those measured in the common good solvent CHCl

3. On the other hand, spherical, compact and large micellar structures were obtained in aqueous solutions. CONTIN analysis from DLS experiments showed that single supramolecular populations exist in water with relatively low polydispersity factor values (μ

2/Γ

2<0.2) for all samples and all concentrations examined (

Figure S12). The ratio R

g/R

ho was close to unity in aqueous solutions.

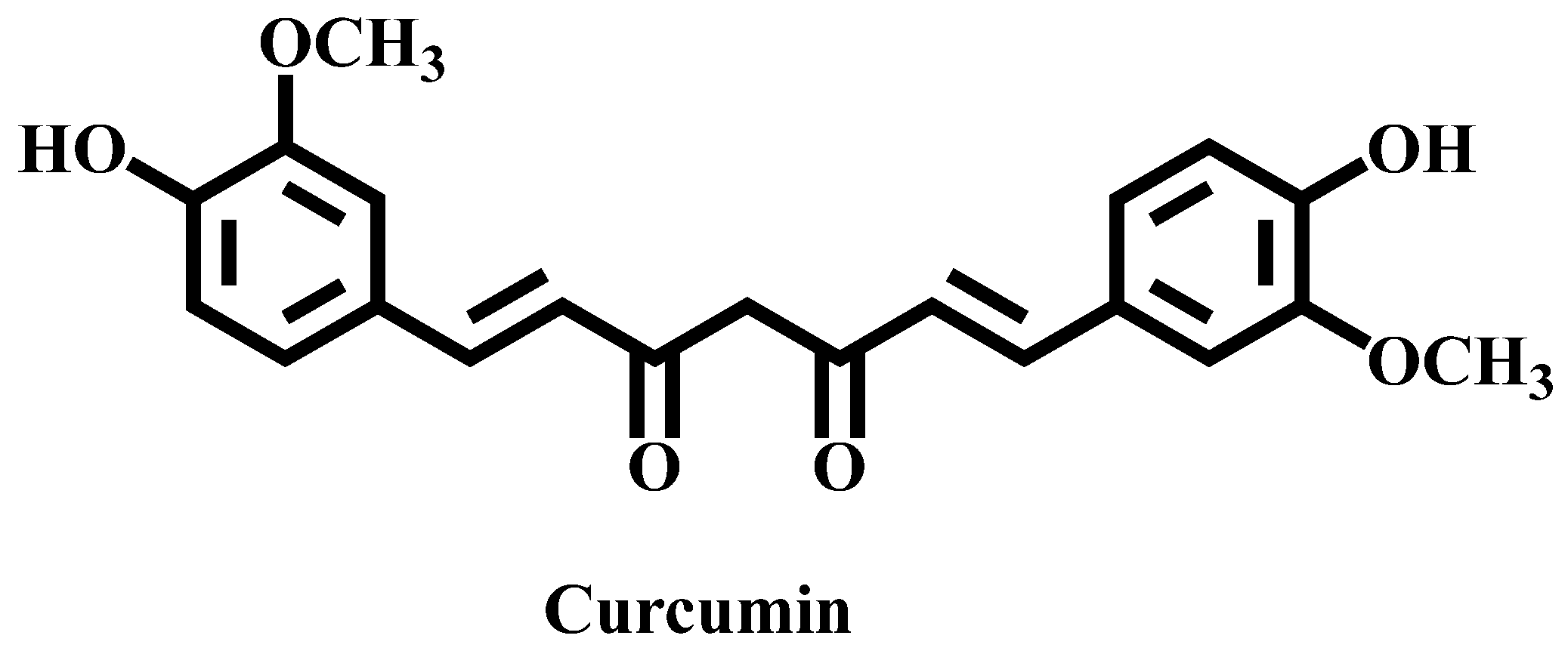

3.5. Encapsulation of Curcumin into the Micellar Solutions

One of the most important applications of the self-assembled structures formed by amphiphilic block copolymers in aqueous solutions is the encapsulation of hydrophobic compounds within the micellar core. Emphasis is given in the encapsulation of compounds with biological and pharmaceutical activity for gene or drug delivery studies. A lot of work has been reported in the literature for amphiphilic block bearing PNVP as the water-soluble constituent [

101]. In previous studies the encapsulation of curcumin was examined in the block copolymers PNVP-

b-PBzMA and PNVP-

b-PIBMA. Curcumin (

Scheme 3) is an interesting compound suitable for these studies for two main reasons. The first one is that it exhibits various interesting pharmaceutical activities, having antioxidant, antibacterial, antimicrobial, antifungal, anti-inflammatory and anti-carcinogenic properties [

102,

103,

104,

105]. Therefore, it has been applied for the treatment of several diseases, such as Alzheimer’s, multiple myeloma, psoriasis, myelodysplastic syndrome, and anti-human immunodeficiency virus cycle replication. The second reason is that the encapsulation of curcumin can be easily studied by UV-Vis spectroscopy, since the solutions of curcumin have a characteristic yellow-orange color. Subsequently, it is easy to understand why multiple efforts have been devoted to achieve efficient encapsulation of curcumin in block copolymer micelles [

106].

Curcumin has a characteristic absorbance band at 423.50 nm in THF solutions. A calibration curve from the absorbance values with concentration was recorded and the results are provided in the SIS (

Figure S13). Employing this calibration curve and measuring the absorbance of the polymer solutions with the encapsulated curcumin, the drug loading capacity, DLC, and the drug loading efficiency, DLE, were calculated employing the following Equations 3 and 4:

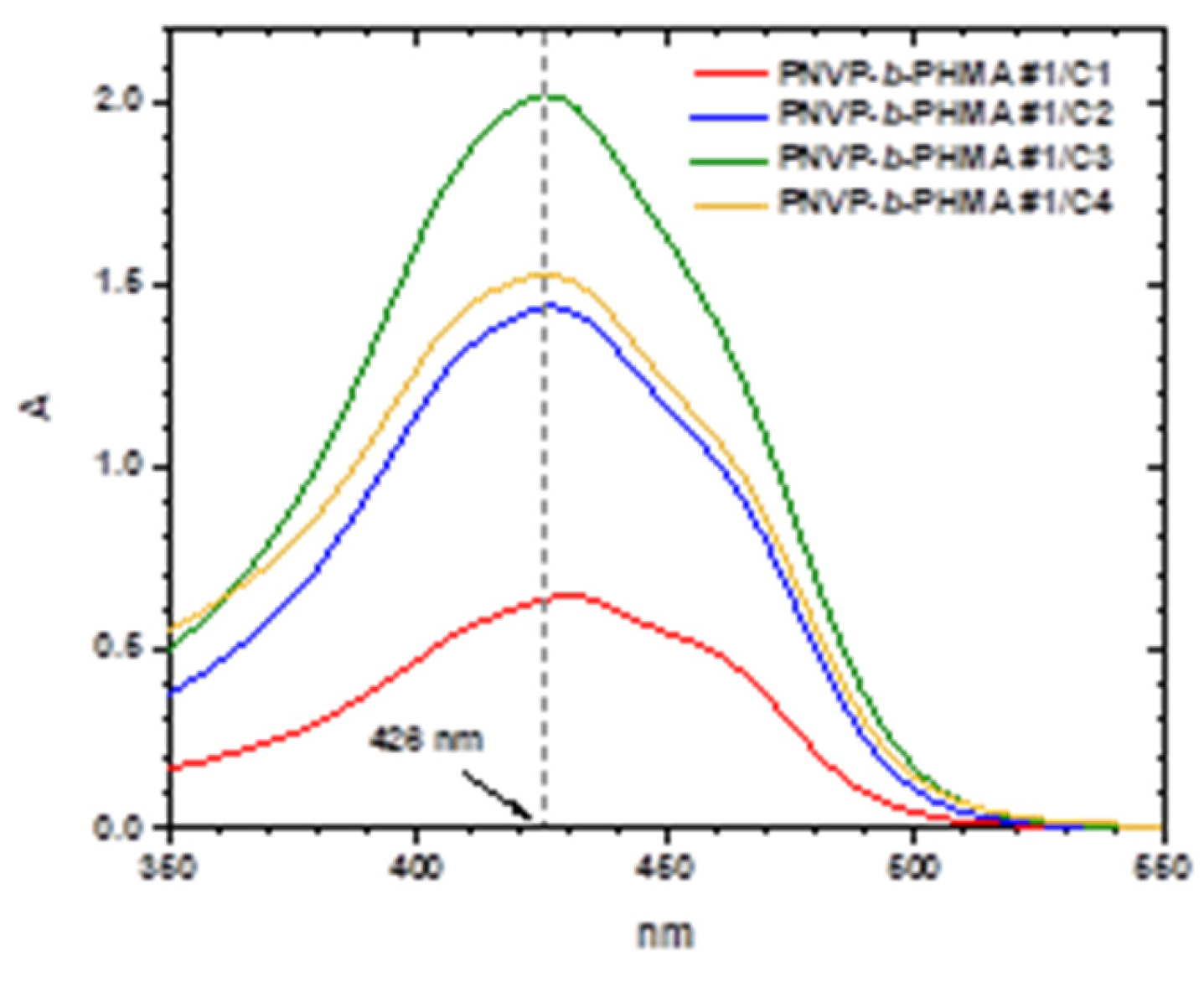

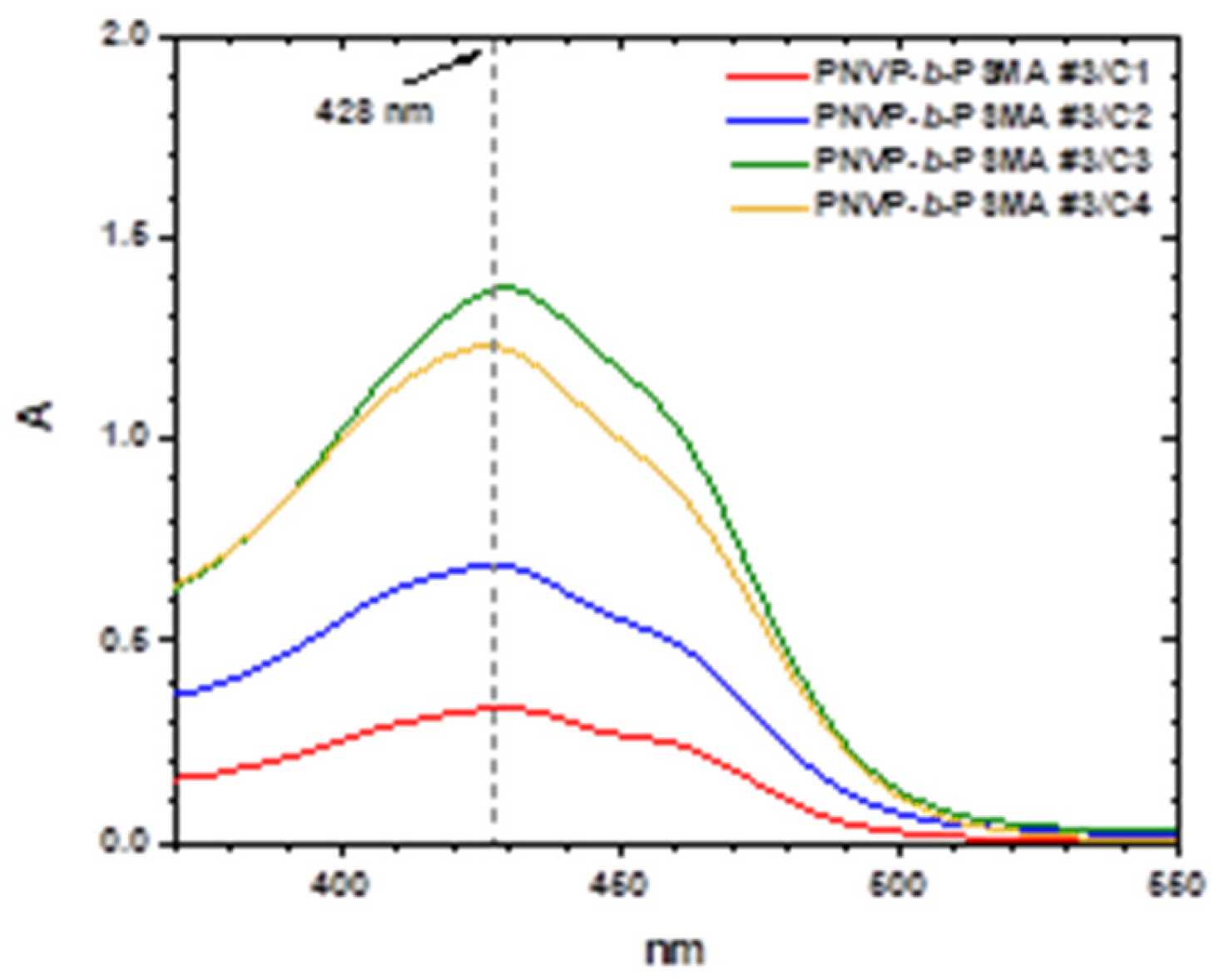

Characteristic UV-vis spectra from the encapsulation of various amounts of curcumin within the micellar core of the block copolymers PNVP-

b-PHMA#1 and PNVP-

b-PSMA#3 are given in

Figure 13 and

Figure 14, whereas the complete data with the DLC and DLE values are given in

Table 13 and

Table 14. More data are given in the SIS (

Figures S14-S15).

It is evident that the encapsulation of curcumin is efficient in the PNVP-b-PHMA solutions. The sample PNVP-b-PHMA #2 has the lower DLC and DLE values compared to the other samples, since it has the lowest molecular weight and therefore the micelles do not have very extended core for the encapsulation of larger quantities of curcumin. In general, the DLC values for the same concentration of the block copolymer progressively increase upon increasing the concentration of curcumin, whereas the DLE values initially increase and gradually reach a plateau value. These values are considerably lower than those found for the PNVP-b-PBzMA copolymers, indicating that the steric hindrance of the ester group of the hydrophobic polymethacrylate block greatly affects the entrapment ability of curcumin. This is further manifested in the case of the PNVP-b-PSMA block copolymers, where the steric hindrance is even more pronounced and the micellar cores are more compact leading to even lower DLC and DLE values.

4. Conclusions

Block copolymers of N-vinyl pyrrolidone (NVP) with n-hexyl methacrylate, HMA, PNVP-b-PHMA, and stearyl methacrylate, SMA, PNVP-b-PSMA, were prepared by the RAFT methodology and sequential addition of monomers, starting from the polymerization of NVP, employing O–ethyl S–(phthalimidylmethyl) xanthate, CTA1 and phthalimidylmethyl dithiobenzoate, CTA XM as universal CTAs. CTA XM was prepared for the first time and offered the possibility to synthesize block copolymers with high composition in PNVP. Relatively well-defined products were obtained according to Size Exclusion Chromatography, SEC and NMR spectroscopy measurements. In certain cases, bimodal distributions were obtained by SEC analysis, showing contamination with PNVP homopolymers, due to accidental termination reactions or not very efficient crossover reaction from the PNVP macro-CTA to the methacrylate monomer. The crude products were effectively purified by fractionation employing chloroform/methanol as the solvent-non solvent system. The thermal properties of the copolymers were analyzed by Differential Scanning Calorimetry, DSC, Thermogravimetric Analysis, TGA, and Differential Thermogravimetry, DTG. The copolymers are microphase separated. However, partial mixing was observed, due to the rather low molecular weights of the block copolymers and the relatively small χ parameter of Flory. The crystallinity of the PSMA block was reduced due to the presence of the amorphous PNVP blocks. The thermal stability of the block copolymers was determined by both components. The micellization behavior of the block copolymers was studied in THF, which is a selective solvent for the polymethacrylate blocks and in aqueous solutions were PNVP is soluble, employing static, SLS, and dynamic light scattering, DLS, techniques. In THF unimolecular micelles or low degree of aggregation supramolecular structures were observed for both types of block copolymers. On the other hand, stable, compact and spherical micelles having very high degrees of association were obtained in aqueous solutions. The bulky nature of the stearyl side ester group introduces severe steric hindrance effects leading to lower association numbers in the case of the PNVP-b-PSMA block copolymers compared to the corresponding PNVP-b-PHMA. Consequently, the manipulation of the nature of the methacrylate’s ester group may considerably alter the self-assembly behavior. The efficient encapsulation of curcumin within the micellar core of the supramolecular structures was demonstrated by UV-Vis spectroscopy measurements. The PNVP-b-PSMA block copolymers showed smaller ability to encapsulate curcumin, due to their lower degrees of association and the more compact micellar cores.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of phthalimidylmethyl dithiobenzoate (CTA XM).

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of phthalimidylmethyl dithiobenzoate (CTA XM).

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of block copolymers PNVP-b-PHMA and PNVP-b-PSMA.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of block copolymers PNVP-b-PHMA and PNVP-b-PSMA.

Figure 1.

SEC traces from the synthesis of the block copolymers PNVP-b-PHMA#2 and #4.

Figure 1.

SEC traces from the synthesis of the block copolymers PNVP-b-PHMA#2 and #4.

Figure 2.

1H NMR spectrum for PNVP-b-PHMA#3 in CDCl3.

Figure 2.

1H NMR spectrum for PNVP-b-PHMA#3 in CDCl3.

Figure 3.

SEC traces from the synthesis of the block copolymers PNVP-b-PSMA#2 and #3.

Figure 3.

SEC traces from the synthesis of the block copolymers PNVP-b-PSMA#2 and #3.

Figure 4.

1H NMR spectrum for PNVP-b-PSMA#1 in CDCl3.

Figure 4.

1H NMR spectrum for PNVP-b-PSMA#1 in CDCl3.

Figure 5.

DSC thermograms for the of the PNVP-b-PHMA block copolymers.

Figure 5.

DSC thermograms for the of the PNVP-b-PHMA block copolymers.

Figure 6.

DSC thermograms for the of the PNVP-b-PSMA block copolymers.

Figure 6.

DSC thermograms for the of the PNVP-b-PSMA block copolymers.

Figure 7.

TGA (left) and DTG (right) thermograms for the PNVP-b-PHMA block copolymers and respective homopolymers.

Figure 7.

TGA (left) and DTG (right) thermograms for the PNVP-b-PHMA block copolymers and respective homopolymers.

Figure 8.

TGA (left) and DTG (right) thermograms for the PNVP-b-PSMA block copolymers and respective homopolymers.

Figure 8.

TGA (left) and DTG (right) thermograms for the PNVP-b-PSMA block copolymers and respective homopolymers.

Figure 9.

SLS Zimm plot of the sample PNVP-b-PHMA#4 in THF.

Figure 9.

SLS Zimm plot of the sample PNVP-b-PHMA#4 in THF.

Figure 10.

SLS Zimm plot of the sample PNVP-b-PHMA#2 in aqueous solution.

Figure 10.

SLS Zimm plot of the sample PNVP-b-PHMA#2 in aqueous solution.

Figure 11.

DLS plots of the samples PNVP-b-PHMA#4 in THF and #2 in aqueous solution.

Figure 11.

DLS plots of the samples PNVP-b-PHMA#4 in THF and #2 in aqueous solution.

Figure 12.

DLS plots of the samples PNVP-b-PSMA#1 in THF and #3 in aqueous solution.

Figure 12.

DLS plots of the samples PNVP-b-PSMA#1 in THF and #3 in aqueous solution.

Scheme 3.

Structure of curcumin.

Scheme 3.

Structure of curcumin.

Figure 13.

UV-Vis spectra of the sample PNVP-b-PHMA#1 with varying concentrations of curcumin (polymer concentration ~5.2x10−4 g/mL and curcumin concentration from 3x10−6 up to 1.0 x10−5 g/mL).

Figure 13.

UV-Vis spectra of the sample PNVP-b-PHMA#1 with varying concentrations of curcumin (polymer concentration ~5.2x10−4 g/mL and curcumin concentration from 3x10−6 up to 1.0 x10−5 g/mL).

Figure 14.

UV-Vis spectra of the sample PNVP-b-PSMA#3 with varying concentrations of curcumin (polymer concentration ~5.3x10−4 g/mL and curcumin concentration from 1.4x10−6 up to 6.8 x10−6 g/mL).

Figure 14.

UV-Vis spectra of the sample PNVP-b-PSMA#3 with varying concentrations of curcumin (polymer concentration ~5.3x10−4 g/mL and curcumin concentration from 1.4x10−6 up to 6.8 x10−6 g/mL).

Table 1.

Quantities for the synthesis of the PNVP-b-PHMA.bock copolymers.

Table 1.

Quantities for the synthesis of the PNVP-b-PHMA.bock copolymers.

| Sample |

PNVP (g) |

AIBN (g) |

HMA (mL) |

Dioxane (mL) |

| PNVP-b-PHMA #1 |

5 |

0.0068 |

1 |

9 |

| PNVP-b-PHMA #2 |

5 |

0.0171 |

1 |

9 |

| PNVP-b-PHMA #3 |

1 |

0.0015 |

3 |

2 |

| PNVP-b-PHMA #4 |

0.5 |

0.0032 |

3 |

2 |

Table 2.

Quantities for the synthesis of the PNVP-b-PSMA bock copolymers.

Table 2.

Quantities for the synthesis of the PNVP-b-PSMA bock copolymers.

| Sample |

PNVP (g) |

AIBN (g) |

SMA (mL) |

Dioxane (mL) |

| PNVP-b-PSMA #1 |

5 |

0.0068 |

1 |

9 |

| PNVP-b-PSMA #2 |

5 |

0.0178 |

1 |

9 |

| PNVP-b-PSMA #3 |

5 |

0.0178 |

3 |

9 |

Table 4.

Molecular characteristics of block copolymers PNVP-b-PSMA.

Table 4.

Molecular characteristics of block copolymers PNVP-b-PSMA.

| |

macro CTA

(PNVP) * |

block

copolymers * |

NVP

|

SMA

|

| Sample |

Mn 103

(Daltons) |

Ð |

Mn 103 (Daltons) |

Ð |

% mol** |

% mol** |

| PNVP-b-PSMA #1 |

29.8 |

1.29 |

37 |

1.31 |

67 |

33 |

| PNVP-b-PSMA #2 |

7.9 |

1.28 |

9.3 |

1.35 |

94 |

6 |

| PNVP-b-PSMA #3 |

7.9 |

1.28 |

10.8 |

1.31 |

83 |

17 |

Table 5.

DSC results of the PNVP-b-PHMA block copolymers.

Table 5.

DSC results of the PNVP-b-PHMA block copolymers.

| Sample |

Tg Experimental (OC) |

|

| PNVP-b-PHMA #1 |

11.4 |

36.7 |

151.3 |

| PNVP-b-PHMA #2 |

7.1 |

- |

152.8 |

| PNVP-b-PHMA #3 |

5.5 |

- |

118.1 |

| PNVP-b-PHMA #4 |

18.5 |

- |

114.6 |

| PNVP |

- |

- |

187.1 |

| PHMA |

5 |

- |

- |

Table 6.

DSC results of the PNVP-b-PSMA block copolymers.

Table 6.

DSC results of the PNVP-b-PSMA block copolymers.

| Sample |

WVSt % |

Tm(°C) |

ΔH(j/g #) |

ΔH(j/gVSt) |

Xc % |

Tg1(°C) |

Tg2(°C) |

| PNVP-b-PSMA #1 |

59.9 |

35.9 |

31.6 |

52.7 |

69.4 |

-14.8 |

147.0 |

| PNVP-b-PSMA #2 |

16.2 |

35.2 |

9.6 |

59.2 |

77.9 |

-15.9 |

154.7 |

| PNVP-b-PSMA #3 |

38.4 |

36.6 |

22.3 |

58.0 |

76.4 |

-7.9 |

147.2 |

| PNVP |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

187.1 |

| PSMA |

- |

34.0 |

75.9 |

- |

- |

-30 |

- |

Table 7.

TGA results of the PNVP-b-PHMA block copolymers.

Table 7.

TGA results of the PNVP-b-PHMA block copolymers.

| Sample |

Start1 |

End1 |

Max1 (OC) |

Start2 |

End2 |

Max2 (OC) |

| PNVP-b-PHMA #1 |

94.9 |

220.4 |

128.7 (broad) |

320.2 |

466.1 |

420.9 |

| PNVP-b-PHMA #2 |

94.9 |

194.5 |

127.7 |

318.9 |

463.8 |

421.0 |

| PNVP-b-PHMA #3 |

204.3 |

413.2 |

296.9 |

- |

- |

- |

| PNVP-b-PHMA #4 |

188.3 |

333.0 |

291.5 (broad) |

- |

- |

- |

| PNVP |

- |

- |

- |

347.63 |

484.06 |

437.53 |

| PHMA |

190.8 |

356.6 |

299.1 (shoulder) |

- |

- |

- |

Table 8.

TGA results of the PNVP-b-PSMA block copolymers.

Table 8.

TGA results of the PNVP-b-PSMA block copolymers.

| Sample |

Start1 |

End1 |

Max1 (OC) |

Start2 |

End2 |

Max2 (OC) |

| PNVP-b-PSMA #1 |

88.8 |

216.6 |

140.8 (broad) |

339.4 |

463.7 |

419.3 |

| PNVP-b-PSMA #2 |

94.3 |

209.2 |

129.1 |

312.6 |

469.2 |

423.5 |

| PNVP-b-PSMA #3 |

113.4 |

198.9 |

154.8 |

323.6 |

470.8 |

421.0 |

| PNVP |

- |

- |

- |

347.6 |

484.0 |

437.5 |

| PSMA |

185.9 |

430.3 |

335.8 |

- |

- |

- |

Table 9.

SLS data for the PNVP-b-PHMA block copolymers.

Table 9.

SLS data for the PNVP-b-PHMA block copolymers.

| Sample |

Solvent |

MW

From SEC |

Mw

From SLS |

Nw

|

Rg

(nm) |

A

(cm3mol/g2) |

| PNVP-b-PHMA #1 |

CHCl3

|

36x103

|

|

|

|

|

| PNVP-b-PHMA #1 |

THF |

|

5.59x104

|

1.55 |

|

2.20x10−4

|

| PNVP-b-PHMA #1 |

WATER |

|

5.88x107

|

1633 |

59.9 |

2.96x10−5

|

| PNVP-b-PHMA #2 |

CHCl3

|

13x103

|

|

|

|

|

| PNVP-b-PHMA #2 |

THF |

|

2.84x104

|

2.18 |

|

1.75x10−4

|

| PNVP-b-PHMA #2 |

WATER |

|

3.58x108

|

27538 |

103.6 |

9.98x10−6

|

| PNVP-b-PHMA #3 |

CHCl3

|

32x103

|

|

|

|

|

| PNVP-b-PHMA #3 |

THF |

|

1.32x105

|

4.13 |

|

4.20x10−5

|

| PNVP-b-PHMA #3 |

WATER |

|

8.06x108

|

25187 |

124.0 |

1.18x10−5

|

| PNVP-b-PHMA #4 |

CHCl3

|

130x103

|

|

|

|

|

| PNVP-b-PHMA #4 |

THF |

|

8.76x105

|

6.74 |

65.0 |

1.01x10−3

|

Table 10.

DLS data for the PNVP-b-PHMA block copolymers .

Table 10.

DLS data for the PNVP-b-PHMA block copolymers .

| Sample |

solvent |

Do |

Kd

|

Rg

(nm) |

Rho

(nm) |

Rg/Rho

|

| PNVP-b-PHMA #1 |

CHCl3

|

6.294x10−7

|

23.36 |

|

6.41 |

|

| PNVP-b-PHMA #1 |

THF |

7.635x10−7

|

19.04 |

|

6.20 |

|

| PNVP-b-PHMA #1 |

WATER |

3.469x10−8

|

384 |

59.9 |

70.73 |

0.85 |

| PNVP-b-PHMA #2 |

CHCl3

|

3.500x10−7

|

143 |

|

11.53 |

|

| PNVP-b-PHMA #2 |

THF |

9.611x10−7

|

37.59 |

|

4.93 |

|

| PNVP-b-PHMA #2 |

WATER |

2.488x10−8

|

199 |

103.6 |

98.62 |

1.05 |

| PNVP-b-PHMA #3 |

CHCl3

|

2.532x10−7

|

160 |

|

15.94 |

|

| PNVP-b-PHMA #3 |

THF |

5.106x10−7

|

33.23 |

|

9.28 |

|

| PNVP-b-PHMA #3 |

WATER |

2.106x10−8

|

1023 |

124 |

116.51 |

1.06 |

| PNVP-b-PHMA #4 |

CHCl3

|

1.621x10−7

|

103 |

|

24.90 |

|

| PNVP-b-PHMA #4 |

THF |

2.092x10−7

|

84.35 |

65 |

22.64 |

2.87 |

Table 11.

SLS results of the PNVP-b-PSMA block copolymers in CHCl3, in THF and aqueous solution.

Table 11.

SLS results of the PNVP-b-PSMA block copolymers in CHCl3, in THF and aqueous solution.

| asmple |

Solvent |

Mw

From SEC |

Mw

From SLS |

Nw

|

Rg

(nm) |

A2

(cm3mol/g2) |

| PNVP-b-PSMA #1 |

CHCl3

|

37x103

|

|

|

|

|

| PNVP-b-PSMA #1 |

THF |

|

2.53x105

|

6.84 |

|

6.00x10−4

|

| PNVP-b-PSMA #1 |

WATER |

|

7.53x107

|

2035 |

48.0 |

4.53x10−5

|

| PNVP-b-PSMA #2 |

CHCl3

|

9.3x103

|

|

|

|

|

| PNVP-b-PSMA #2 |

THF |

|

4.70x104

|

5.05 |

|

3.50x10−4

|

| PNVP-b-PSMA #2 |

WATER |

|

3.68x107

|

3957 |

43.8 |

7.40x10−5

|

| PNVP-b-PSMA #3 |

CHCl3

|

10.8x103

|

|

|

|

|

| PNVP-b-PSMA #3 |

THF |

|

7.20x104

|

6.67 |

|

2.50x10−4

|

| PNVP-b-PSMA #3 |

WATER |

|

1.192x107

|

1104 |

36.1 |

7.30x10−5

|

Table 12.

DLS results of the PNVP-b-PSMA block copolymers in CHCl3, in THF and aqueous solution.

Table 12.

DLS results of the PNVP-b-PSMA block copolymers in CHCl3, in THF and aqueous solution.

| Sample |

solvent |

Do |

Kd

|

Rg (nm) |

Rho (nm) |

Rg/Rho

|

| PNVP-b-PSMA #1 |

CHCl3

|

3.289x10−7

|

158.8 |

|

12.27 |

|

| PNVP-b-PSMA #1 |

THF |

6.295x10−7

|

50.05 |

|

7.53 |

|

| PNVP-b-PSMA #1 |

WATER |

3.171x10−8

|

1179 |

48 |

77.38 |

0.62 |

| PNVP-b-PSMA #2 |

CHCl3

|

3.116x10−7

|

231.2 |

|

12.96 |

|

| PNVP-b-PSMA #2 |

THF |

9.033x10−7

|

28.90 |

|

5.24 |

|

| PNVP-b-PSMA #2 |

WATER |

4.418x10−8

|

952.0 |

43.8 |

55.53 |

0.79 |

| PNVP-b-PSMA #3 |

CHCl3

|

2.567x10−7

|

166.0 |

|

15.72 |

|

| PNVP-b-PSMA #3 |

THF |

6.577x10−7

|

156.8 |

|

7.20 |

|

| PNVP-b-PSMA #3 |

WATER |

6.474x10−8

|

462.9 |

36.1 |

37.90 |

0.95 |

Table 13.

DLC and DLE values from the encapsulation of curcumin within the micellar solutions of the PNVP-b-PHMA#1 block copolymers (polymer concentration ~5.2x10−4 g/mL and curcumin concentration from 3x10−6 up to 1.0 x10−5 g/mL).

Table 13.

DLC and DLE values from the encapsulation of curcumin within the micellar solutions of the PNVP-b-PHMA#1 block copolymers (polymer concentration ~5.2x10−4 g/mL and curcumin concentration from 3x10−6 up to 1.0 x10−5 g/mL).

| Sample |

DLC% |

DLE% |

| PNVP-b-PHMA #1 |

|

|

| 1/c1 |

0.59 |

50.54 |

| 1/c2 |

1.35 |

76.50 |

| 1/c3 |

1.92 |

67.96 |

| 1/c4 |

1.46 |

38.58 |

| PNVP-b-PHMA #2 |

|

|

| 2/c1 |

0.12 |

13.30 |

| 2/c2 |

0.78 |

35.75 |

| 2/c3 |

0.82 |

29.09 |

| 2/c4 |

1.01 |

29.56 |

| PNVP-b-PHMA #3 |

|

|

| 3/c1 |

0.32 |

34.65 |

| 3/c2 |

0.99 |

48.46 |

| 3/c3 |

1.28 |

47.33 |

| 3/c4 |

1.60 |

48.46 |

Table 14.

DLC and DLE values from the encapsulation of curcumin within the micellar solutions of the PNVP-b-PSMA#3 block copolymers (polymer concentration ~5.3x10−4 g/mL and curcumin concentration from 1.4x10−6 up to 6.8 x10−6 g/mL).

Table 14.

DLC and DLE values from the encapsulation of curcumin within the micellar solutions of the PNVP-b-PSMA#3 block copolymers (polymer concentration ~5.3x10−4 g/mL and curcumin concentration from 1.4x10−6 up to 6.8 x10−6 g/mL).

| Sample |

DLC% |

DLE% |

| PNVP-b-PSMA #1 |

- |

- |

| 1/c1 |

0.40 |

39.97 |

| 1/c2 |

0.91 |

40.99 |

| 1/c3 |

1.32 |

46.11 |

| 1/c4 |

1.68 |

47.01 |

| PNVP-b-PSMA #2 |

|

|

| 2/c1 |

0.14 |

11.88 |

| 2/c2 |

0.92 |

39.21 |

| 2/c3 |

0.81 |

26.74 |

| 2/c4 |

1.43 |

39.57 |

| PNVP-b-PSMA #3 |

|

|

| 3/c1 |

0.27 |

24.01 |

| 3/c2 |

0.61 |

26.39 |

| 3/c3 |

1.26 |

43.19 |