Submitted:

02 August 2025

Posted:

04 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Mathematical Model

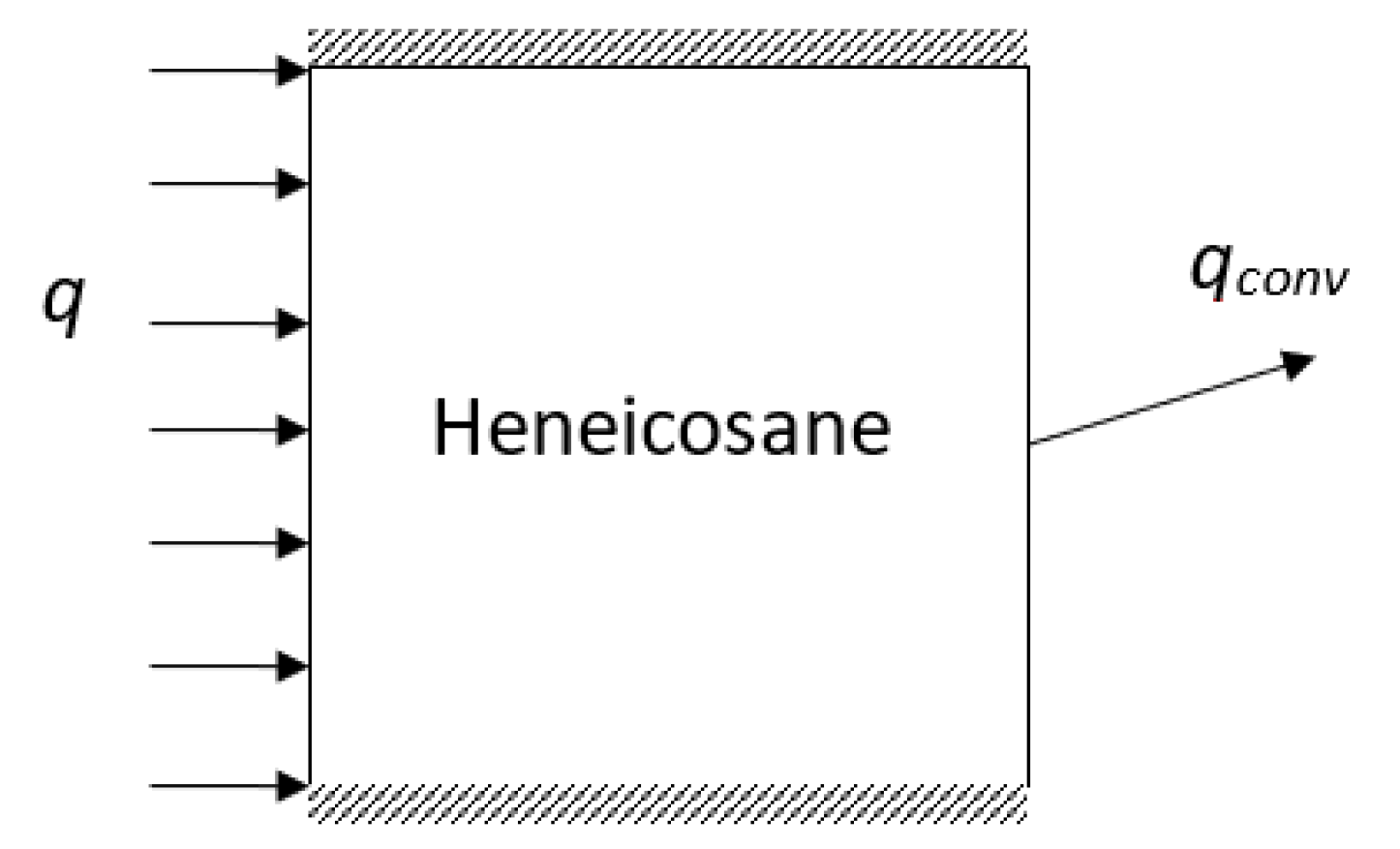

2.1. Physical Model and Simulation Methodology

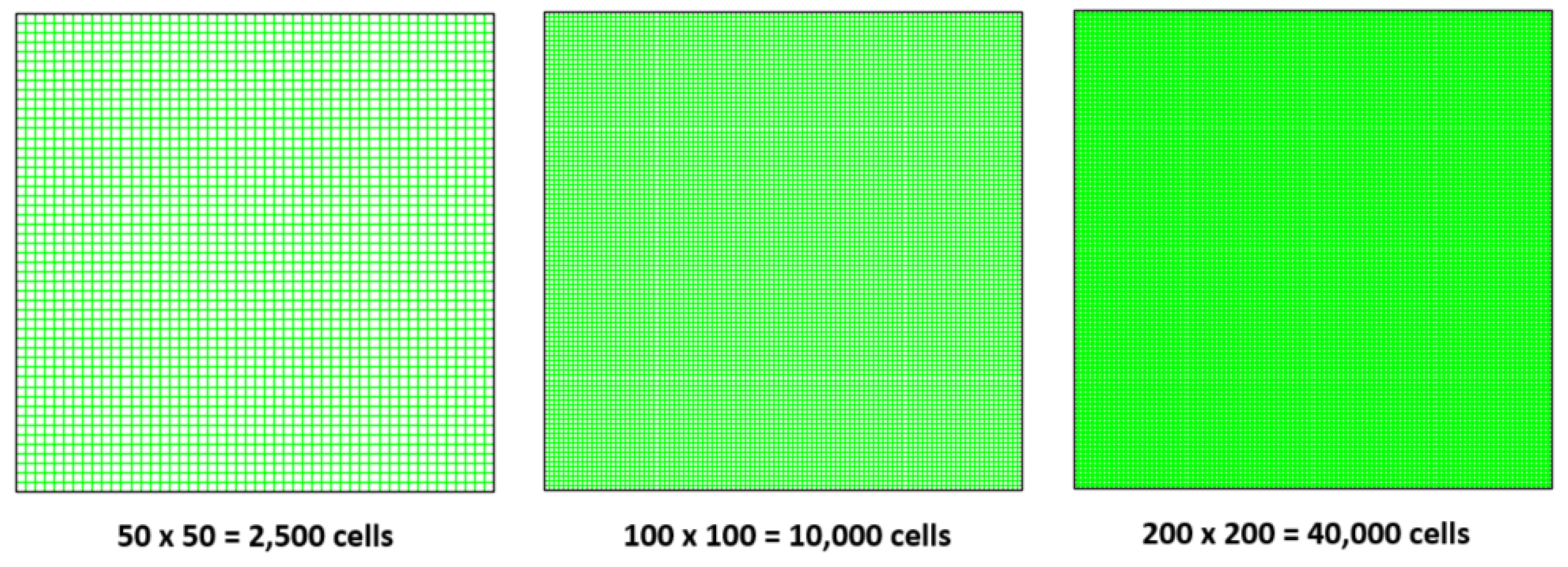

2.2. Grid Test

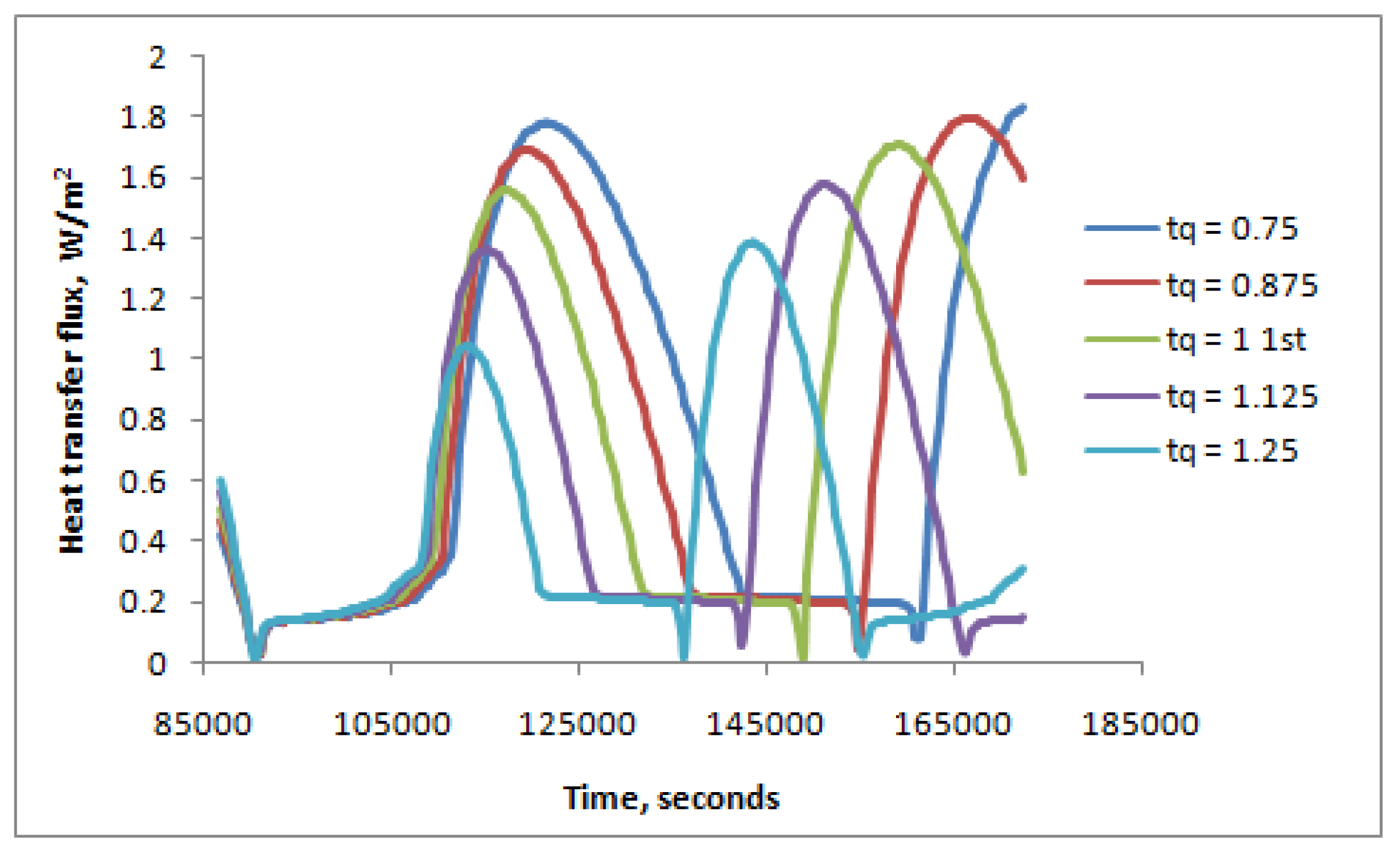

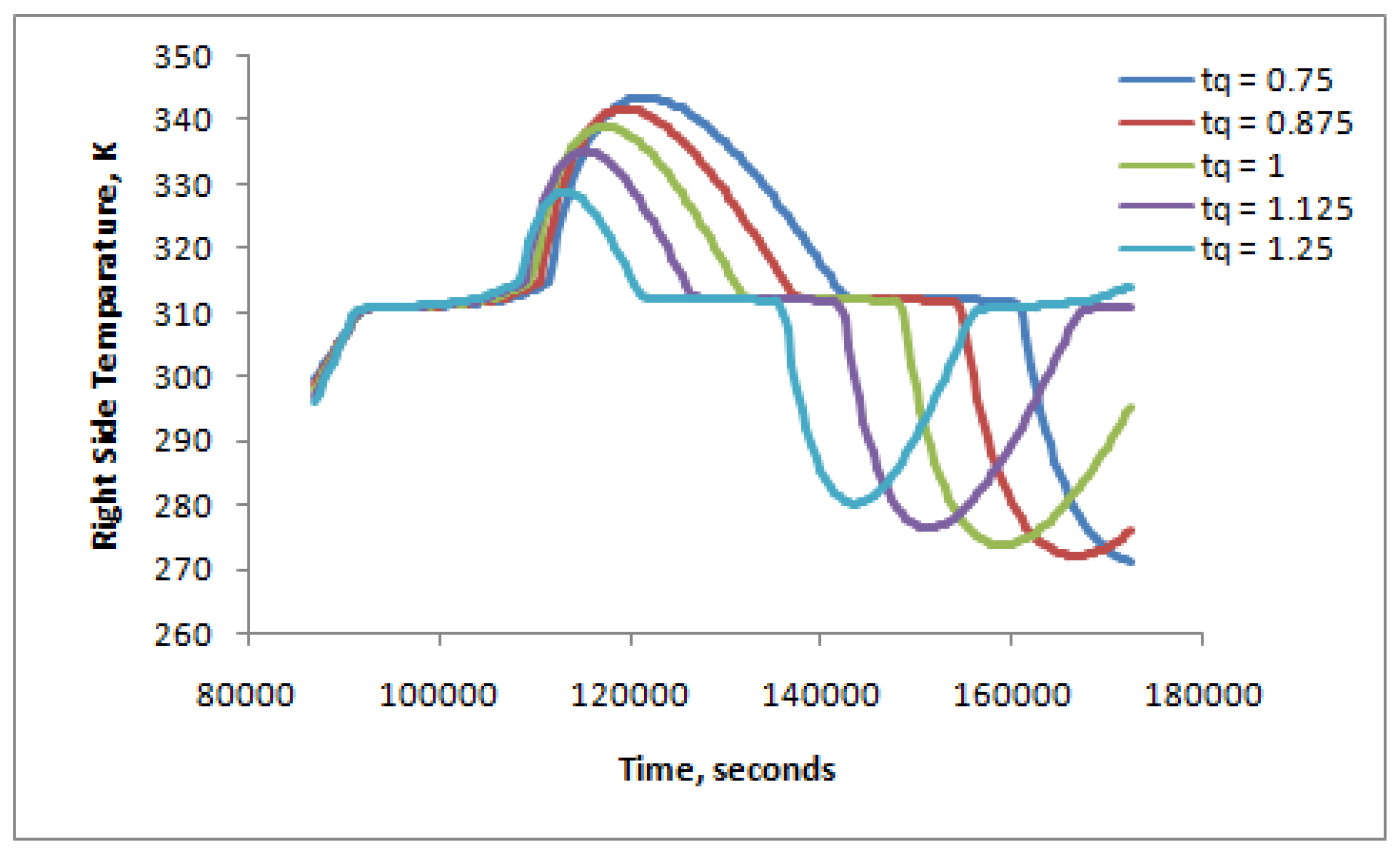

2.3. Time Step Selection

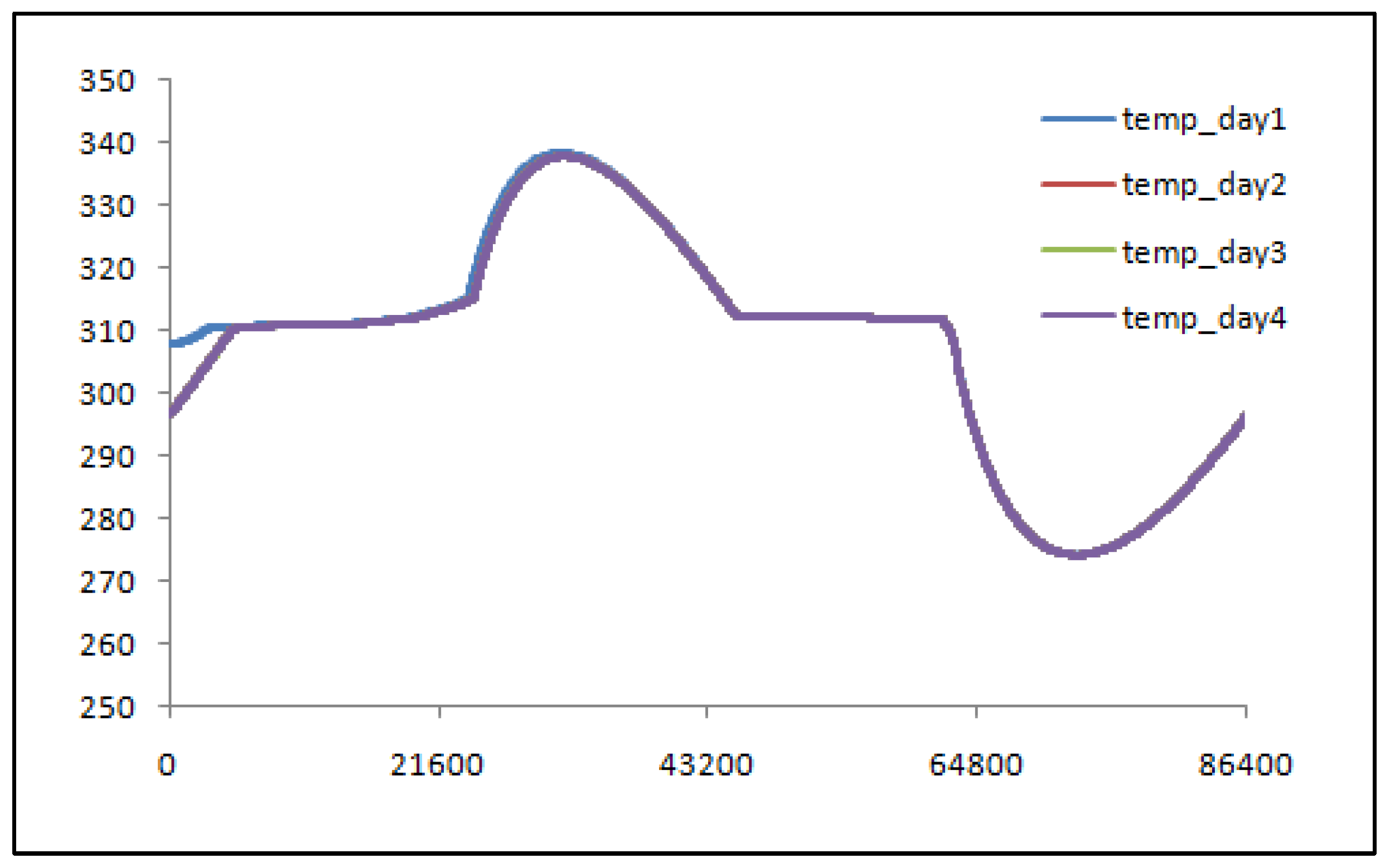

2.4. Initial Condition Effect

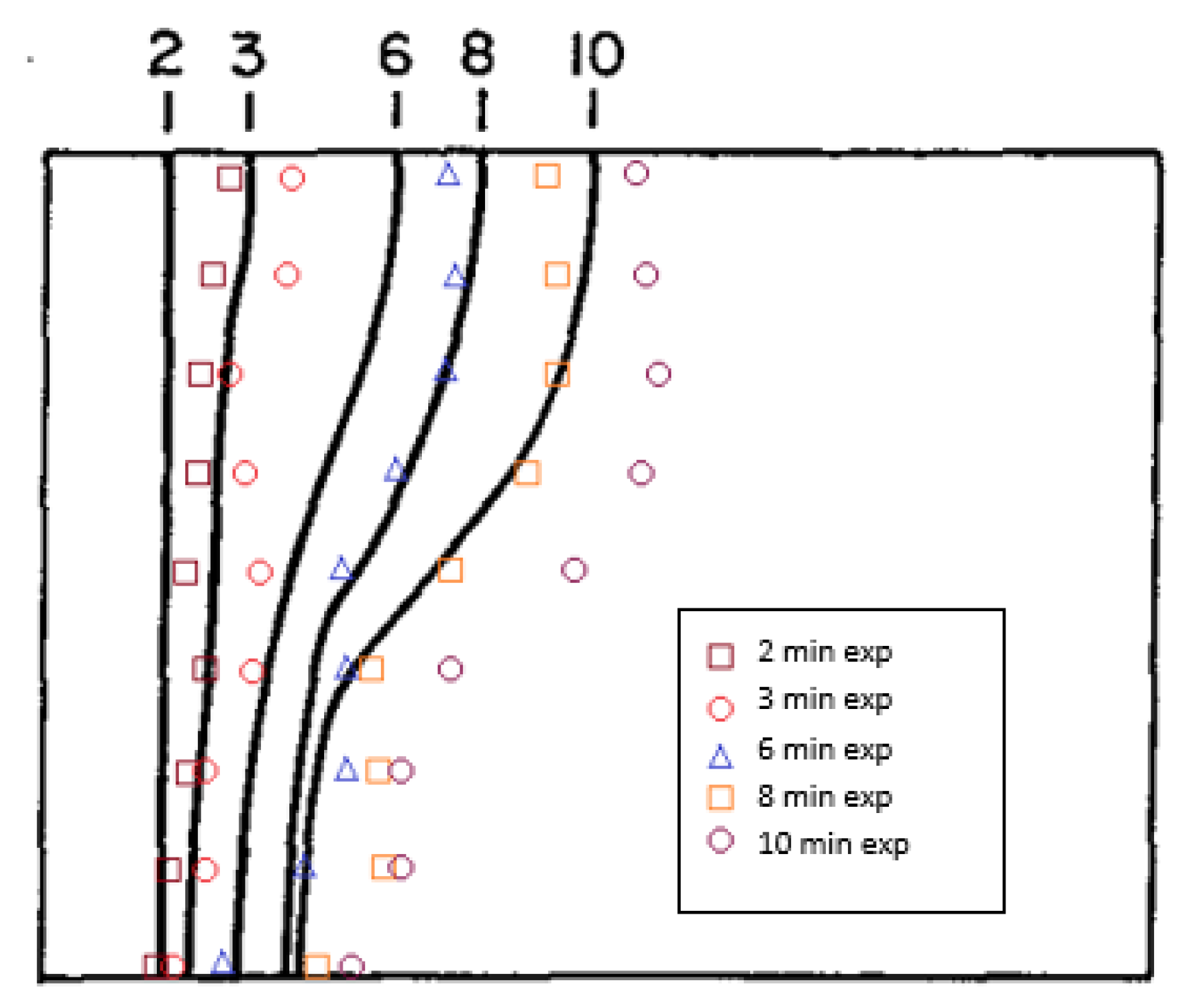

2.5. Numerical Model Validation

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| Cp | thermal capacity |

| ho | convective heat transfer coefficient |

| k | thermal conductivity |

| P | pressure |

| q | left side heat flux gain – variable over a full day |

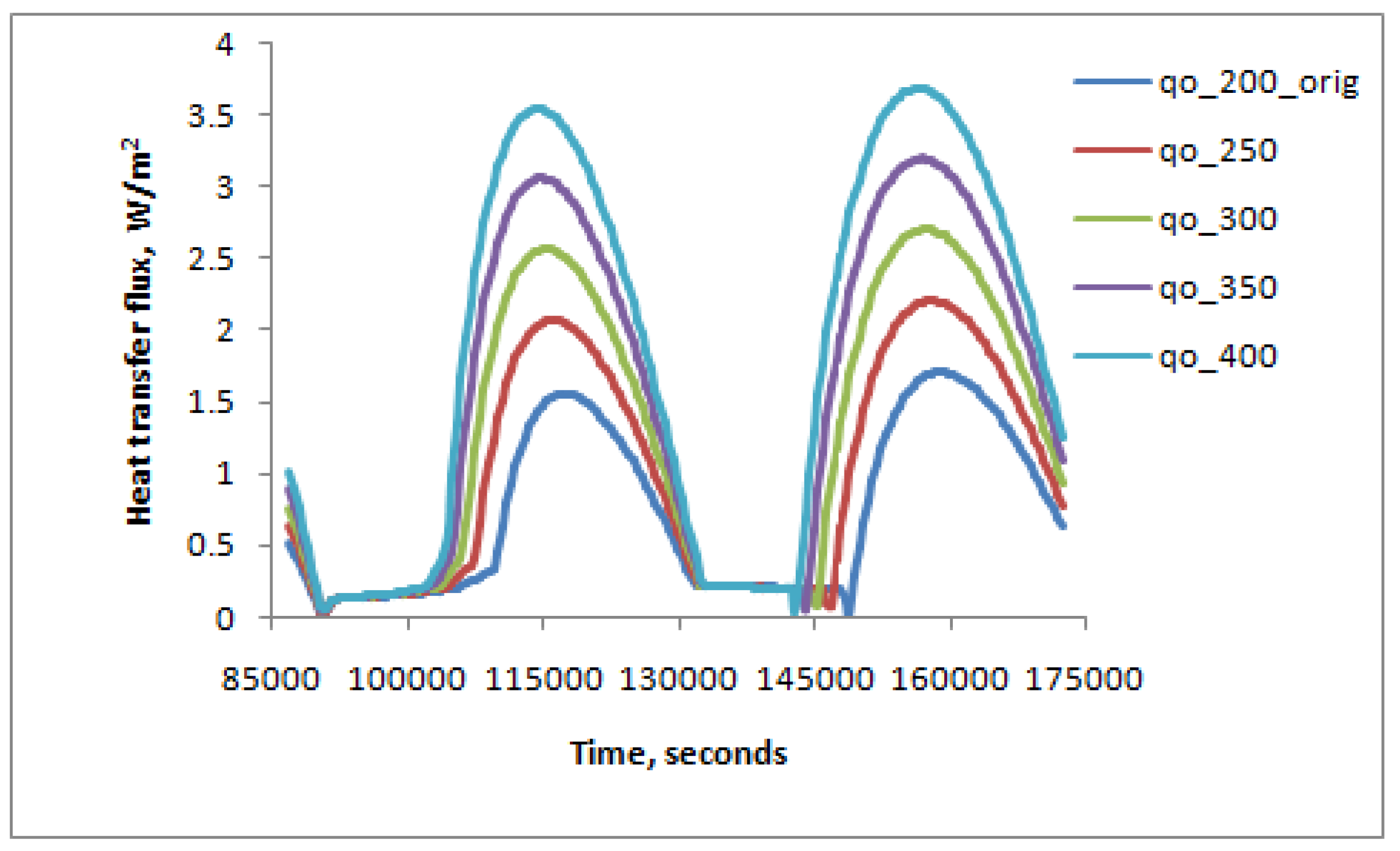

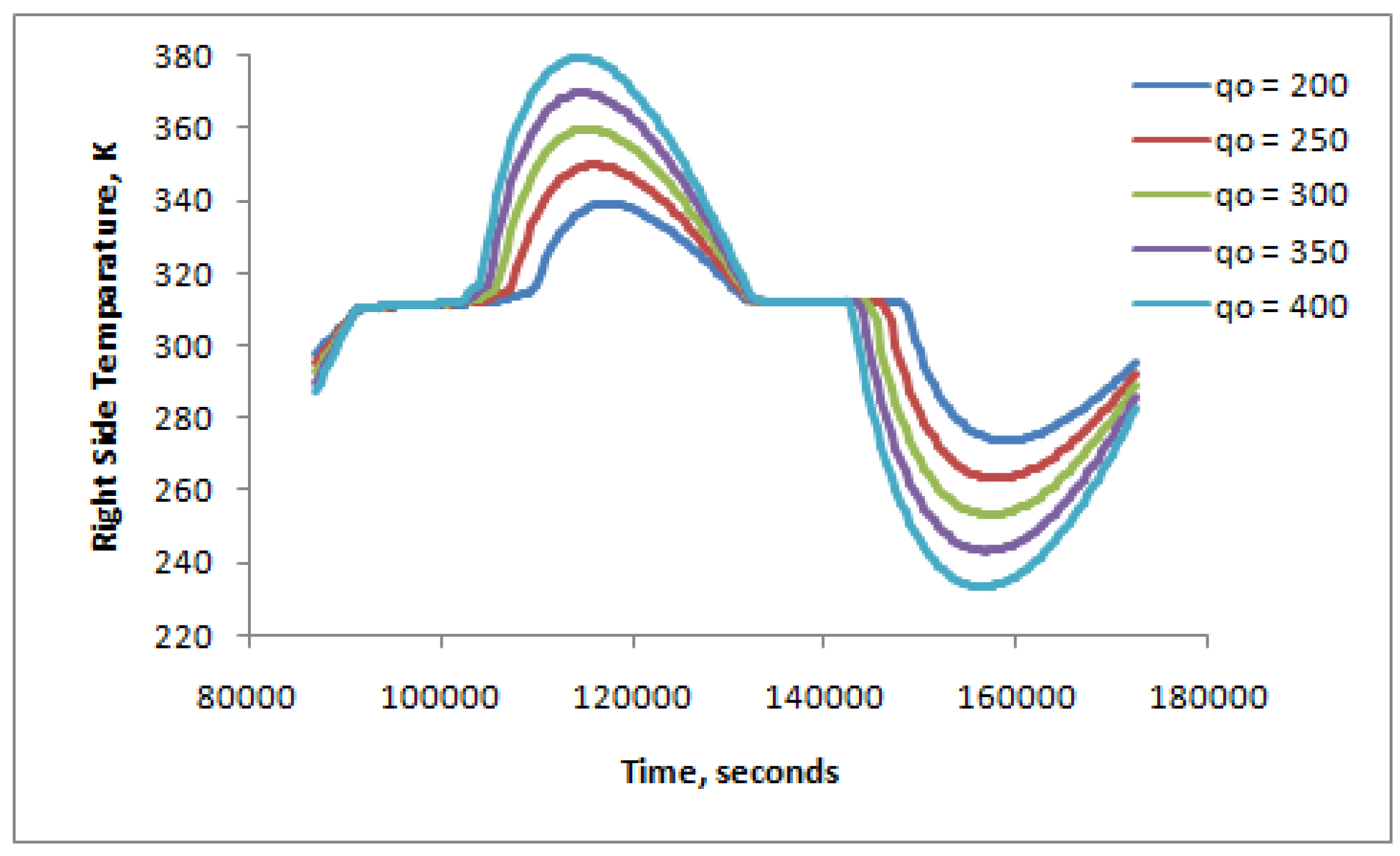

| qo | left side heat flux gain - constant |

| ql’’ | left side heat transfer flux |

| qr’’ | right side heat transfer flux |

| Ql | left side total heat transfer flux |

| Qr | right side total heat transfer flux |

| Qout | total heat flow rate leave the system during a full day |

| Qin | total heat flow rate enter the system during a full day |

| T∞ | outdoor temperature |

| T | temperature |

| u | x-component velocity |

| v | y-component velocity |

| x | axial direction |

| y | vertical direction |

| Greek symbols | |

| Thermal diffusivity | |

| β | thermal coefficient of expansion |

| ηth | thermal efficiency |

| µ | dynamic viscosity |

| ρ | density |

| τq | time period |

References

- O’Connor WE, Warzoha R, Weigand R, Fleischer AS, Wemhoff AP. Thermal property prediction and measurement of organic phase change materials in the liquid phase near the melting point. Applied energy. 2014 Nov 1;132:496-506. [CrossRef]

- O’Connor WE, Wemhoff AP. Quantification of phase change material energy storage capability using multiphysics simulations. In International Electronic Packaging Technical Conference and Exhibition 2015 Jul 6 (Vol. 56888, p. V001T09A065). American Society of Mechanical Engineers. [CrossRef]

- European Association for Storage of Energy. Available online: https://ease-storage.eu/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/2023.09.26-Thermal-Energy-Storage_for-distribution.pdf (accessed on 3rd July 2025).

- Sarbu I, Sebarchievici C. A comprehensive review of thermal energy storage. Sustainability. 2018 Jan 14;10(1):191. [CrossRef]

- Tay NH, Liu M, Belusko M, Bruno F. Review on transportable phase change material in thermal energy storage systems. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 2017 Aug 1;75:264-77. [CrossRef]

- Tehrmtest Instruments. Available online: https://thermtest.com/phase-change-material-pcm#:~:text=There%20are%203%20types%20of,paraffin%20compounds%20or%20fatty%20acids%20 (accessed on 3rd July 2025).

- PCM Products. Available online: https://www.pcmproducts.net/Phase-Change-Material-Solutions.htm (accessed on 3rd July 2025).

- Jian-you L. Numerical and experimental investigation for heat transfer in triplex concentric tube with phase change material for thermal energy storage. Solar Energy. 2008 Nov 1;82(11):977-85. [CrossRef]

- Veerappan M, Kalaiselvam S, Iniyan S, Goic R. Phase change characteristic study of spherical PCMs in solar energy storage. Solar energy. 2009 Aug 1;83(8):1245-52. [CrossRef]

- Hoshi A, Mills DR, Bittar A, Saitoh TS. Screening of high melting point phase change materials (PCM) in solar thermal concentrating technology based on CLFR. Solar Energy. 2005 Sep 1;79(3):332-9. [CrossRef]

- Trp A. An experimental and numerical investigation of heat transfer during technical grade paraffin melting and solidification in a shell-and-tube latent thermal energy storage unit. Solar energy. 2005 Dec 1;79(6):648-60. [CrossRef]

- Medina MA, King JB, Zhang M. On the heat transfer rate reduction of structural insulated panels (SIPs) outfitted with phase change materials (PCMs). Energy. 2008 Apr 1;33(4):667-78. [CrossRef]

- Kenisarin M, Mahkamov K. Solar energy storage using phase change materials. Renewable and sustainable energy reviews. 2007 Dec 1;11(9):1913-65. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Tang B, Zhang S. Organic, cross-linking, and shape-stabilized solar thermal energy storage materials: A reversible phase transition driven by broadband visible light. Applied energy. 2014 Jan 1;113:59-66. [CrossRef]

- Neeper DA. Thermal dynamics of wallboard with latent heat storage. Solar energy. 2000 Jan 1;68(5):393-403. [CrossRef]

- Zhou G, Zhang Y, Zhang Q, Lin K, Di H. Performance of a hybrid heating system with thermal storage using shape-stabilized phase-change material plates. Applied Energy. 2007 Oct 1;84(10):1068-77. [CrossRef]

- Athienitis AK, Liu C, Hawes D, Banu D, Feldman D. Investigation of the thermal performance of a passive solar test-room with wall latent heat storage. Building and environment. 1997 Sep 1;32(5):405-10. [CrossRef]

- Zhu N, Ma Z, Wang S. Dynamic characteristics and energy performance of buildings using phase change materials: A review. Energy Conversion and Management. 2009 Dec 1;50(12):3169-81. [CrossRef]

- Diaconu BM, Cruceru M. Novel concept of composite phase change material wall system for year-round thermal energy savings. Energy and buildings. 2010 Oct 1;42(10):1759-72. [CrossRef]

- Cabeza LF, Castellón C, Nogués M, Medrano M, Leppers R, Zubillaga O. Use of microencapsulated PCM in concrete walls for energy savings. Energy and buildings. 2007 Feb 1;39(2):113-9. [CrossRef]

- Castellón C, Medrano M, Roca J, Cabeza LF, Navarro ME, Fernández AI, Lázaro A, Zalba B. Effect of microencapsulated phase change material in sandwich panels. Renewable Energy. 2010 Oct 1;35(10):2370-4. [CrossRef]

- Eddhahak-Ouni A, Drissi S, Colin J, Neji J, Care S. Experimental and multi-scale analysis of the thermal properties of Portland cement concretes embedded with microencapsulated Phase Change Materials (PCMs). Applied Thermal Engineering. 2014 Mar 1;64(1-2):32-9. [CrossRef]

- Li M, Wu Z, Tan J. Heat storage properties of the cement mortar incorporated with composite phase change material. Applied Energy. 2013 Mar 1;103:393-9. [CrossRef]

- Weinstein RD, Kopec TC, Fleischer AS, D’Addio E, Bessel CA. The experimental exploration of embedding phase change materials with graphite nanofibers for the thermal management of electronics. J. Heat Transfer. Apr 2008, 130(4): 042405 (8 pages). [CrossRef]

- Garimella SV, Fleischer AS, Murthy JY, Keshavarzi A, Prasher R, Patel C, Bhavnani SH, Venkatasubramanian R, Mahajan R, Joshi Y, Sammakia B. Thermal challenges in next-generation electronic systems. IEEE Transactions on Components and Packaging Technologies. 2008 Nov 25;31(4):801-15. [CrossRef]

- Garimella SV. Advances in mesoscale thermal management technologies for microelectronics. Microelectronics Journal. 2006 Nov 1;37(11):1165-85. [CrossRef]

- Bianco V, De Rosa M, Vafai K. Phase-change materials for thermal management of electronic devices. Applied Thermal Engineering. 2022 Sep 1;214:118839. [CrossRef]

- Kandasamy R, Wang XQ, Mujumdar AS. Application of phase change materials in thermal management of electronics. Applied Thermal Engineering. 2007 Dec 1;27(17-18):2822-32. [CrossRef]

- Sikiru S, Oladosu TL, Amosa TI, Kolawole SY, Soleimani H. Recent advances and impact of phase change materials on solar energy: A comprehensive review. Journal of Energy Storage. 2022 Sep 1;53:105200. [CrossRef]

- Javadi FS, Metselaar HS, Ganesan PJ. Performance improvement of solar thermal systems integrated with phase change materials (PCM), a review. Solar Energy. 2020 Aug 1;206:330-52. [CrossRef]

- Ismail KA, Lino FA, Machado PL, Teggar M, Arıcı M, Alves TA, Teles MP. New potential applications of phase change materials: A review. Journal of Energy Storage. 2022 Sep 1;53:105202. [CrossRef]

- Faraj K, Khaled M, Faraj J, Hachem F, Castelain C. Phase change material thermal energy storage systems for cooling applications in buildings: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 2020 Mar 1;119:109579. [CrossRef]

- Mahdaoui M, Hamdaoui S, Ait Msaad A, Kousksou T, El Rhafiki T, Jamil A, Ahachad M. Building bricks with phase change material (PCM): Thermal performances. Construction and Building Materials. 2021 Feb 1;269:121315. [CrossRef]

- Hawes DW, Banu D, Feldman D. Latent heat storage in concrete. Solar energy materials. 1989 Nov 1;19(3-5):335-48. [CrossRef]

- Memon SA. Phase change materials integrated in building walls: A state of the art review. Renewable and sustainable energy reviews. 2014 Mar 1;31:870-906. [CrossRef]

- Zhu N, Li S, Hu P, Wei S, Deng R, Lei F. A review on applications of shape-stabilized phase change materials embedded in building enclosure in recent ten years. Sustainable Cities and Society. 2018 Nov 1;43:251-64. [CrossRef]

- Warzoha RJ, Weigand RM, Fleischer AS. Temperature-dependent thermal properties of a paraffin phase change material embedded with herringbone style graphite nanofibers. Applied Energy. 2015 Jan 1;137:716-25. [CrossRef]

- Gau C, Viskanta RC. Melting and solidification of a pure metal on a vertical wall. J. Heat Transfer. Feb 1986, 108(1): 174-181 (8 pages). [CrossRef]

- O’Connor WE. Predictions of phase change material thermal efficiency using multiscale analysis. Master’s thesis, Villanova University, 2015.

- White FM, Majdalani J. Viscous fluid flow, Vol. 3; McGraw-Hill: New York, USA, 2006; pp. 433-434.

- Nikitin ED, Pavlov PA, Bessonova NV. Critical constants of n-alkanes with from 17 to 24 carbon atoms. The Journal of Chemical Thermodynamics. 1994 Feb 1;26(2):177-82. [CrossRef]

- CAMEO Chemicals. Database of Hazardous Materials. In: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, editor.2013.

- National Institutes of Health. PubChem. PubChem2013.

- Weast RC, Graselli JG. CRC Handbook of Data on Organic Compounds. 2nd ed. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, Inc. 1989.

- LookChem. LookChem. In: LookChem.com, editor.2013.

- Domalski ES, Hearing ED. Heat capacities and entropies of organic compounds in the condensed phase. Volume III. Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data. 1996;25:1-525.

- Jalal IM, Zografi G, Rakshit AK, Gunstone FD. Thermal analysis of fatty acids. Chemistry and Physics of Lipids. 1982 Dec 1;31(4):395-404. [CrossRef]

- Grodzka PG. Study of phase-change materials for a thermal control system. Huntsville, Ala: Lockheed Missiles & Space Company. 1970.

| Property | Symbol | Value | Units |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density | ρ | 772 | kg/m3 |

| Thermal Capacity | Cp | 2,390 | J/kg.K |

| Thermal Conductivity | k | 0.145 | W/m.K |

| Dynamic Viscosity | µ | 0.008 | kg/m.s |

| thermal coefficient of expansion | β | 0.0005 | K-1 |

| Melting Heat | ΔHf | 295,000 | J/kg |

| Solidus Temperature | 311.5 | K | |

| Liquidus Temperature | 312.5 | K |

| First day run | Second day run | |||

| Average parameters on right side along edge | 50x50 | 100x100 | 50x50 | 100x100 |

| Temperature, Average Error % compared to 200x200 | 0.4684 % | 0.2473 % | 0.4877 % | 0.2490 % |

| Efficiency, Average Error % compared to 200x200 | 0.04651 % | 0.02765 % | 0.05795 % | 0.03083 % |

| First day run | Second day run | |||

| Average parameters on right side along edge | 10 seconds | 5 seconds | 10 seconds | 5 seconds |

| Temperature, Average Error % compared to 3 seconds | 0.3235 % | 0.04177 % | 0.3388 % | 0.05028 % |

| efficiency, Average Error % compared to 3 seconds | 0.04130 % | 0.005230 % | 0.04372 % | 0.006251 % |

| Error compared to 4th day results | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Average parameters on right hand side along edge |

First day | Second day | Third day |

| Temperature, Average Error % compared to 4th day |

0.1763 % | 0.01080 % | 0.001704 % |

| Heat transfer rate, Average Error % compared to 4th day |

26.58 % | 0.1007 % | 0.003386 % |

| Efficiency, Average Error % compared to 4th day |

0.0009194 % | 0.00006136 % | 0.00000181 % |

| Property | Symbol | Value | Units |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liquid density, ρ | ρ | 6093 | Kg/m3 |

| Mass-based heat capacity, Cp | Cp | 381.5 | J/kg.K |

| Thermal conductivity, k | k | 32.0 | W/m.K |

| Dynamic viscosity, μ | μ | 1.81e-3 | Pa.s |

| Thermal coefficient of expansion, β | β | 1.2e-4 | K-1 |

| Latent heat of fusion, ΔHf | ΔHf | 80.16 | kJ/kg |

| Melting temperature, Tm | 302.93 | K |

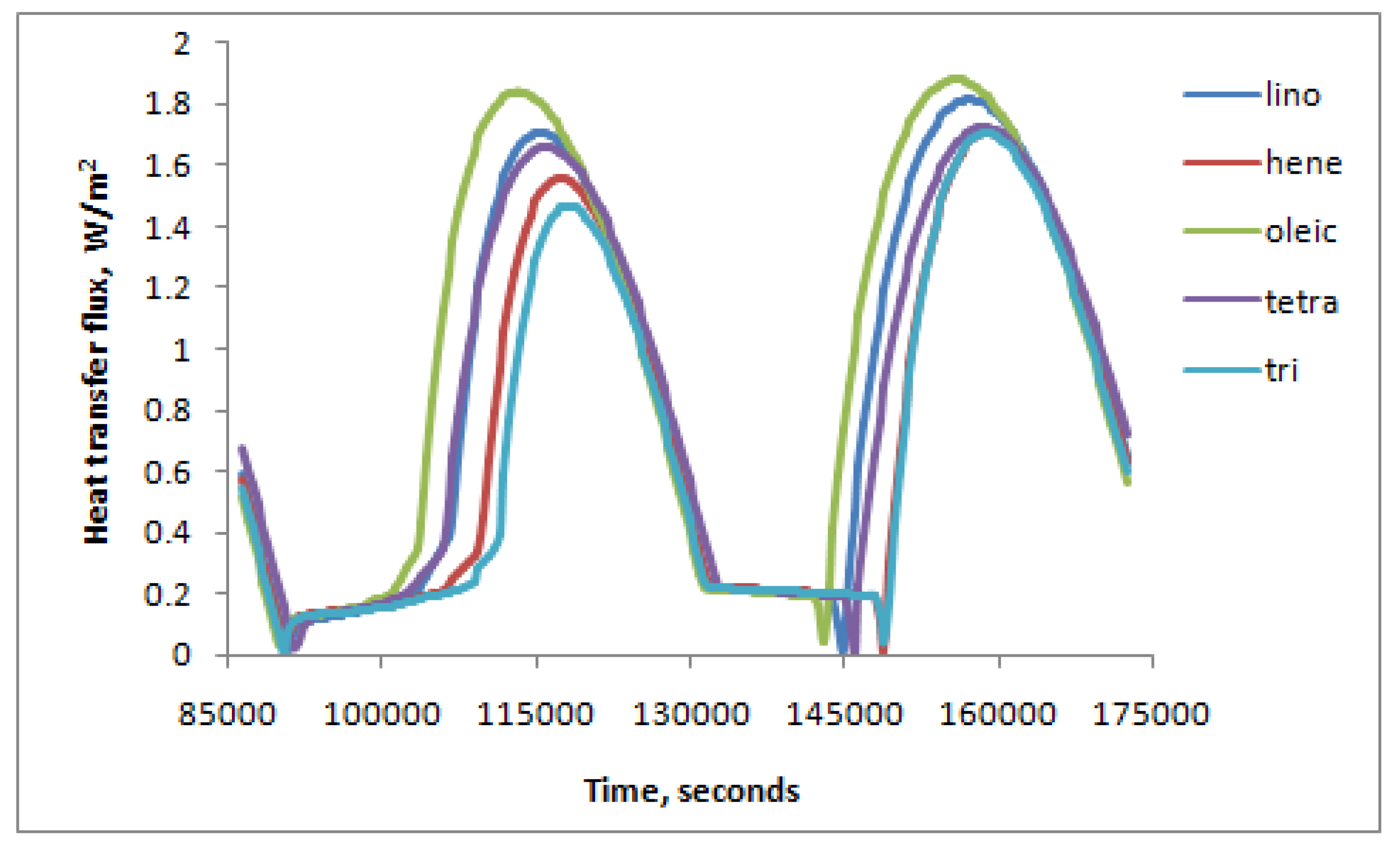

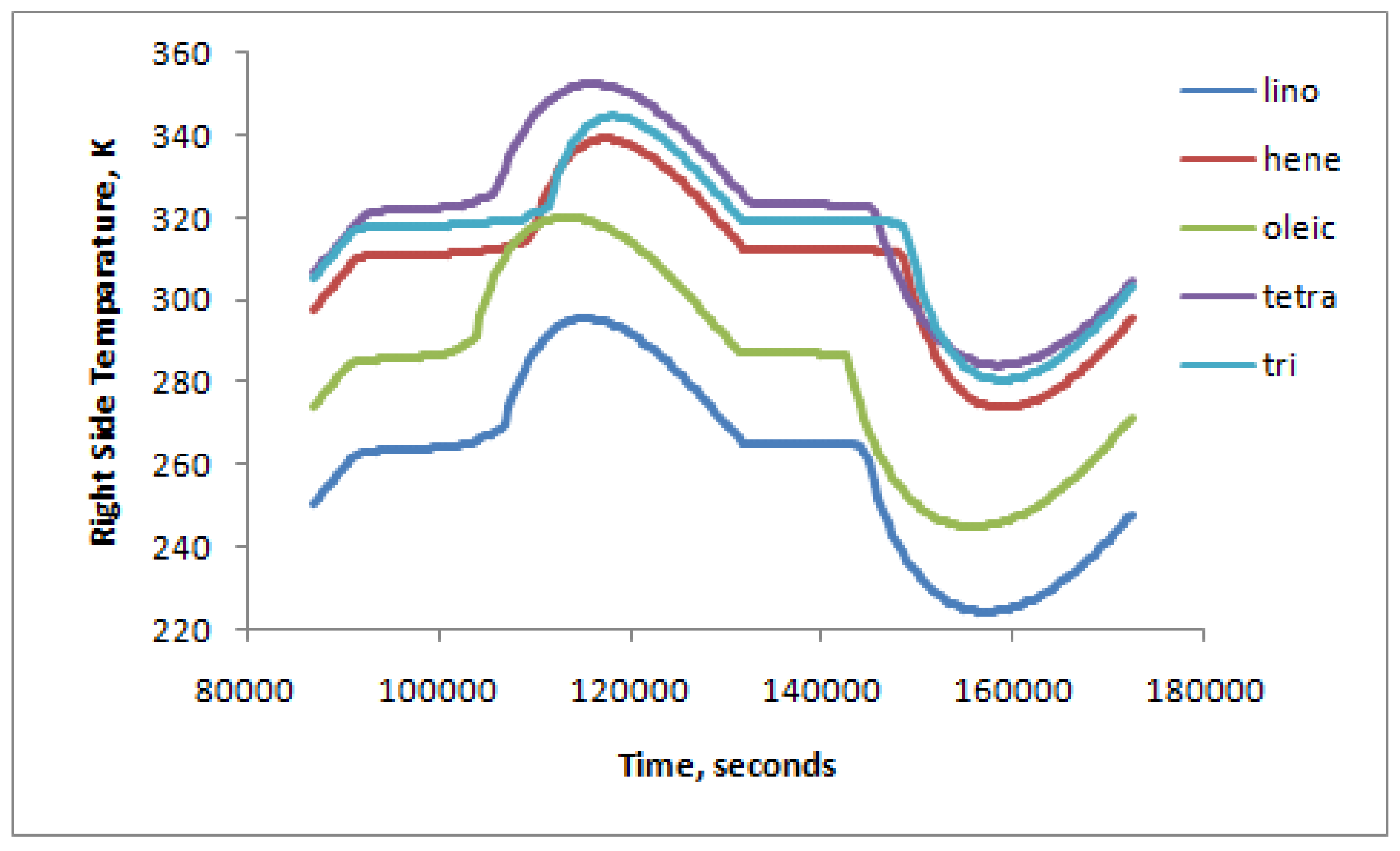

| PCM material | Tm (K) | ρ (kg/m3) | Cp (kJ/kg.K) | K (W/m.K) | ΔHf (kJ/kg) |

| Heneicosane | 312 | 772 | 2.39 | 0.145 | 295 |

| Tricosane | 319 | 778 | 2.18 | 0.124 | 303 |

| Tetracosane | 323 | 774 | 2.92 | 0.137 | 208 |

| Oleic Acid | 287 | 871 | 1.74 | 0.103 | 140 |

| Linoleic Acid | 265 | 902 | 1.92 | 0.087 | 170 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).