Submitted:

02 August 2025

Posted:

04 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

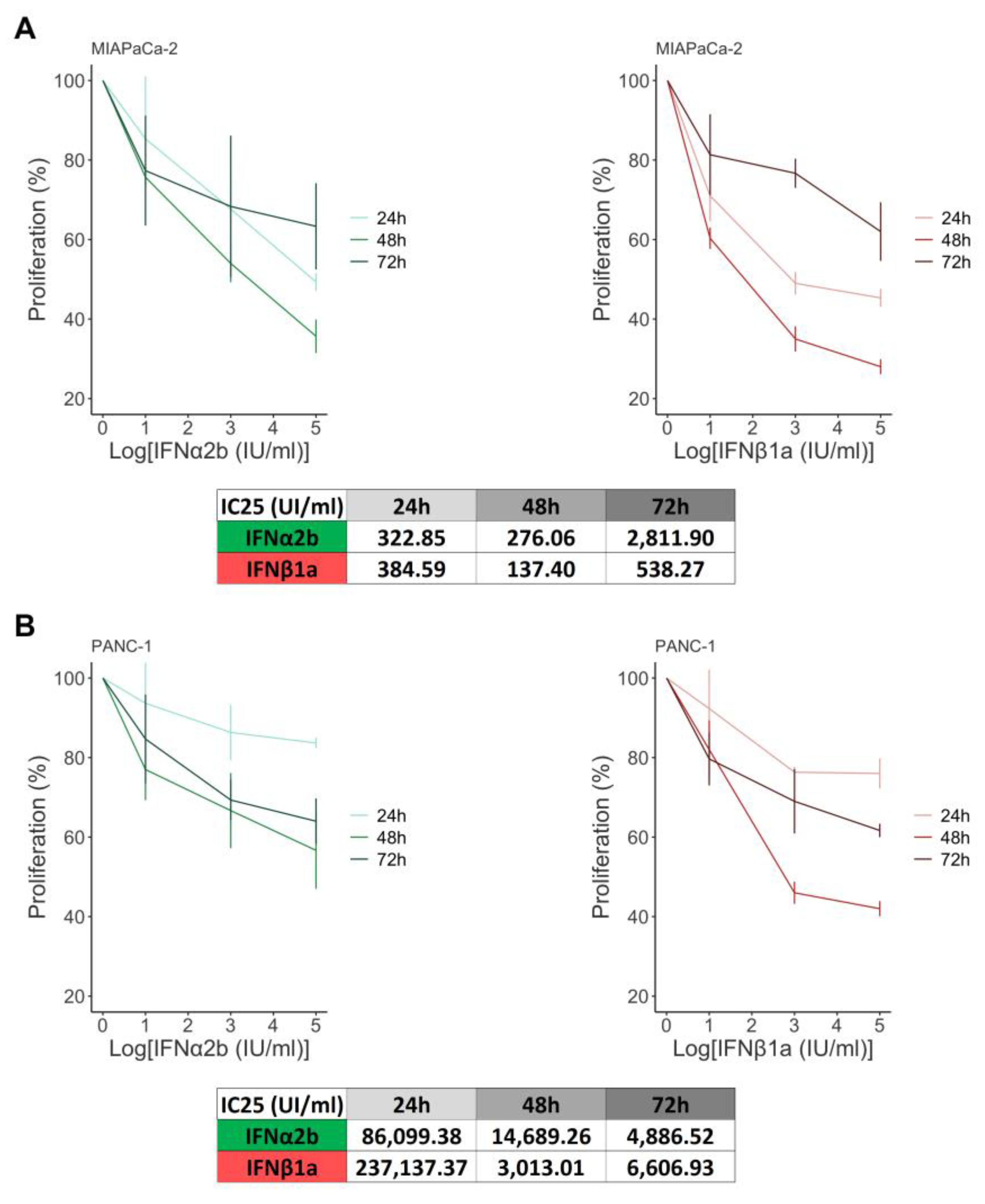

2.1. IFNα2b and IFNβ1a Decrease the Proliferation of MIAPaCa-2 and PANC-1 cells

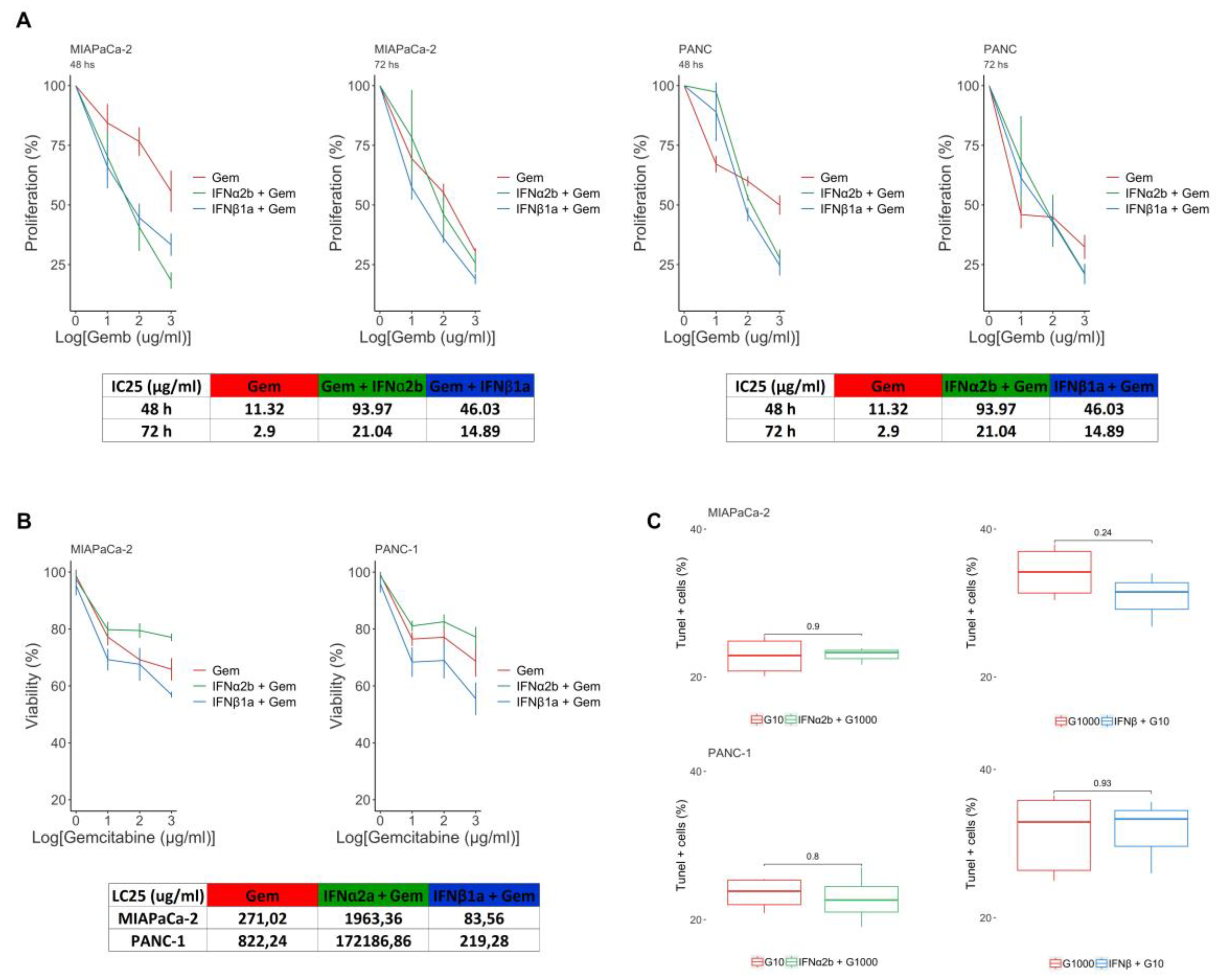

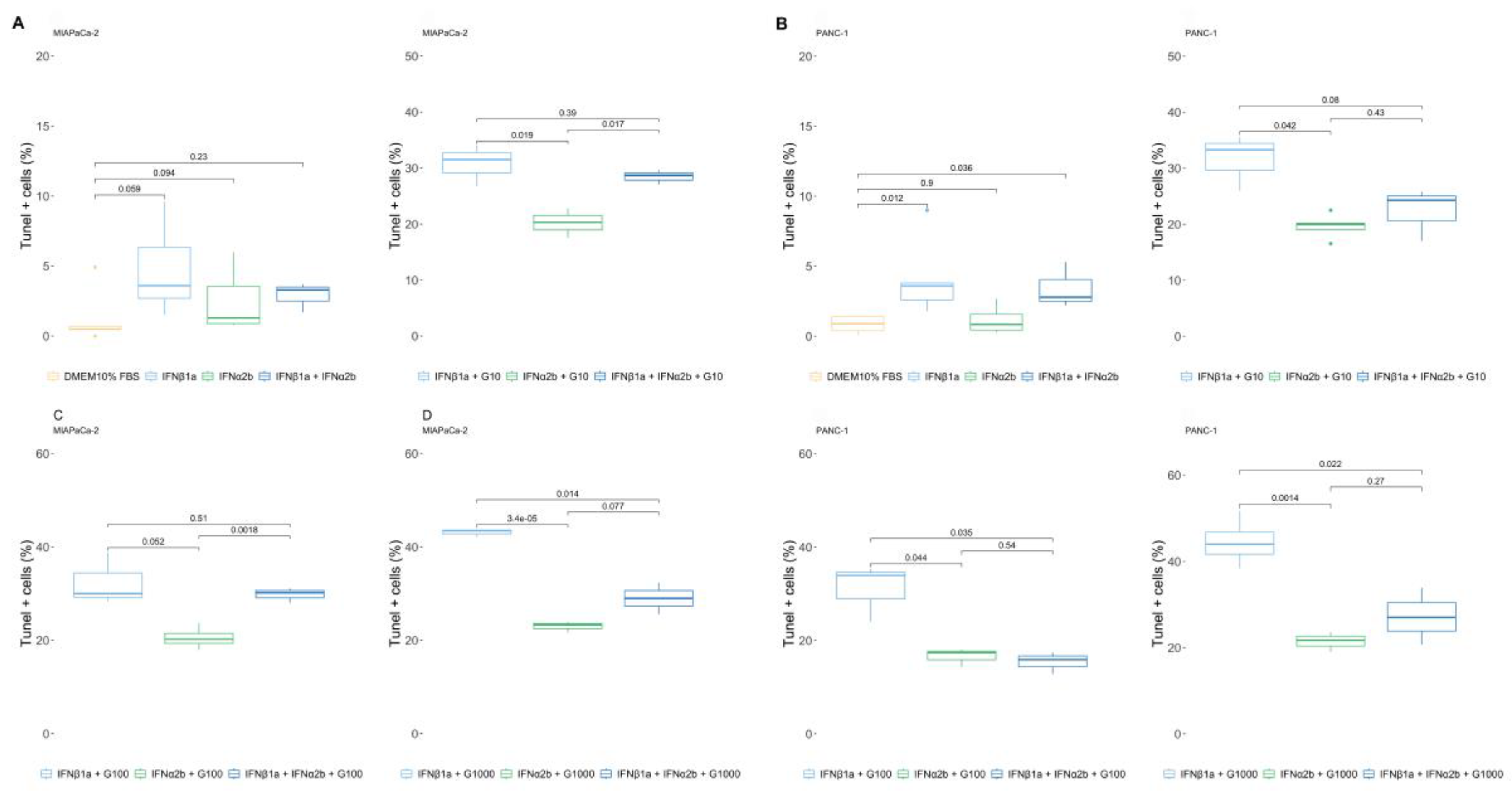

2.2. IFNβ1a Sensitizes Cells to Gemcitabine, but IFNα2b Renders Them More Resistant

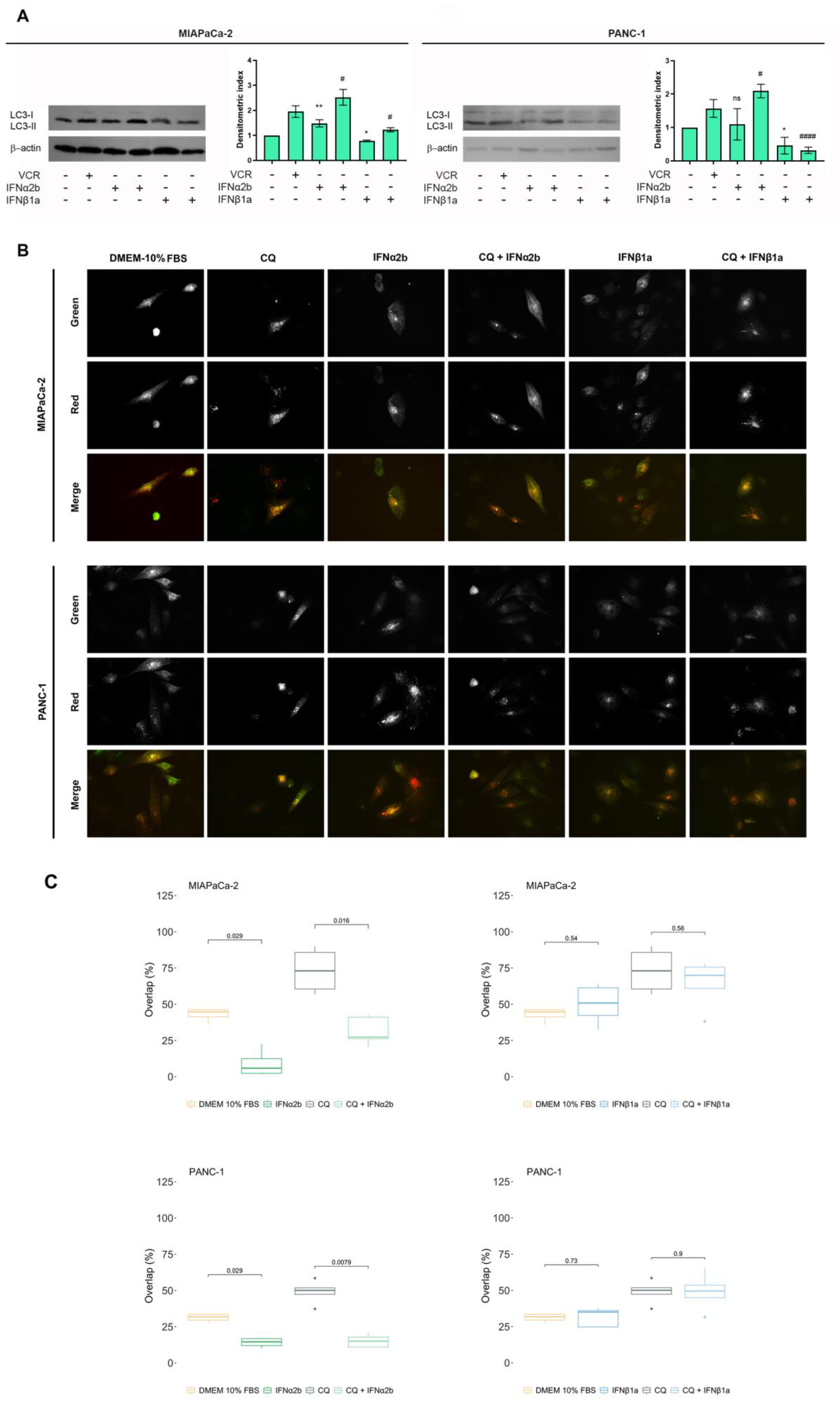

2.3. IFNα2b and IFNβ1a Have Opposite Effects on the Induction of Autophagy Flux

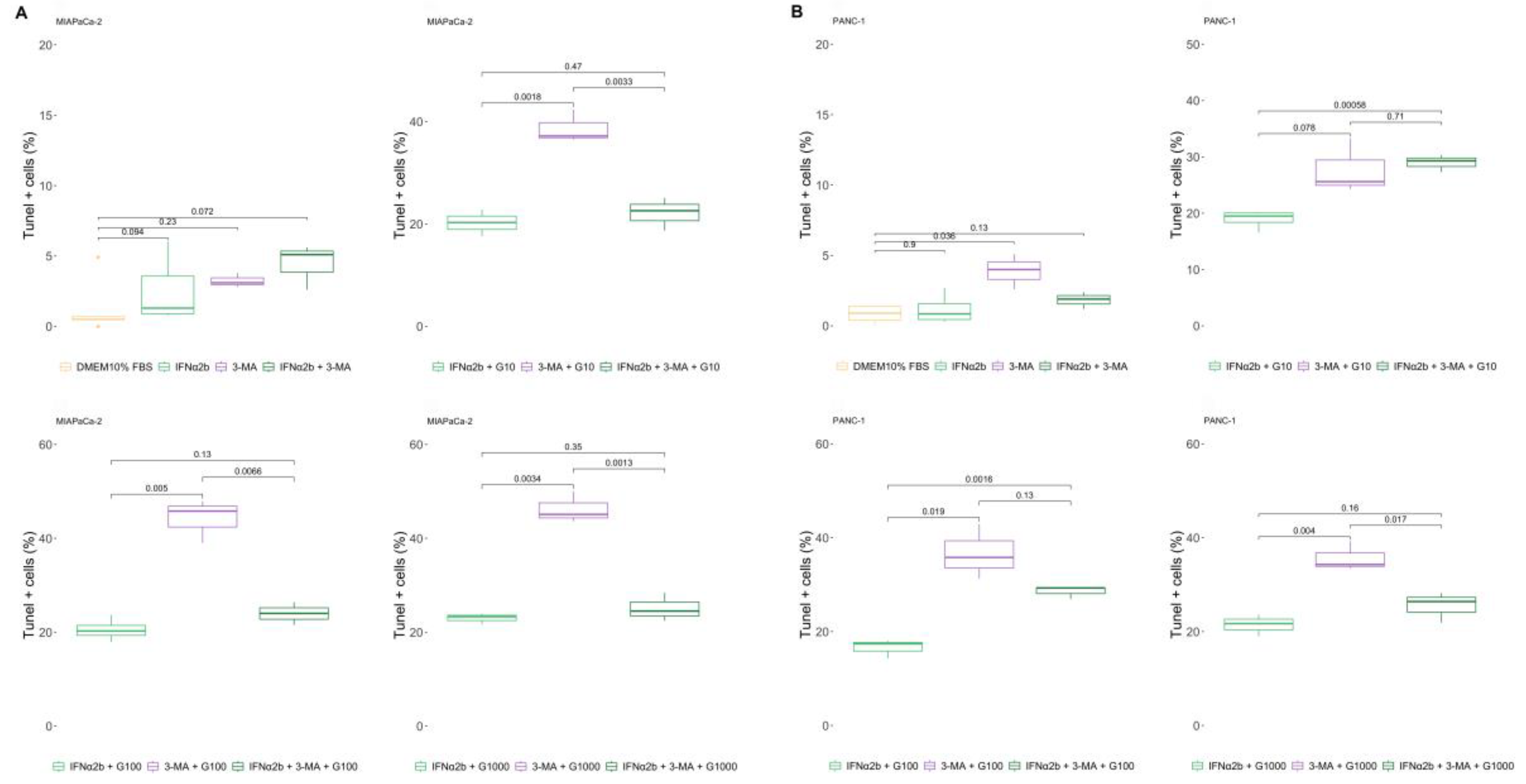

2.4. 3-MA Rescues the IFNα2b-Mediated Resistance of Pancreatic Cancer Cells to Gemcitabine, and IFNα2b Rescues IFNβ1a-Mediated Sensitization

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Cell Culure and Viability

4.3. Assessment of Cell Proliferation

4.4. Apoptotic Assessment

4.5. Total Protein Extracts

4.6. Western Blot

4.7. Autophagy Flux Assay

4.8. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 3-MA | 3-methyladenine |

| [³H]TdR | tritiated thymidine |

| AKT | Protein Kinase B |

| ATCC | American Type Culture Collection |

| CQ | chloroquine |

| DAPI | 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium |

| EC50 | half maximal effective concentration |

| EGFP | enhanced green fluorescent protein |

| FBS | fetal bovine serum |

| HCC | hepatocellular carcinoma |

| HEPES | 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid |

| IC25 / IC50 | inhibitory concentration 25% / 50% |

| IFN-I | type I interferons |

| IFNα2b | interferon alpha 2b |

| IFNβ1a | interferon beta 1a |

| IFNAR-1 / IFNAR-2 | interferon alpha/beta receptor subunit 1 / 2 |

| JAK/STAT | Janus kinase / Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription |

| LC25 | lethal concentration 25% |

| LC3B / LC3-II | microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3 isoform B / lipidated form (II) |

| MAPK | mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MHC | major histocompatibility complex |

| mTORC1 / mTORC2 | mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 / 2 |

| PBS | phosphate-buffered saline |

| PDAC | pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma |

| PI3K | phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase |

| PVDF | polyvinylidene difluoride |

| R | R statistical software |

| RFP | red fluorescent protein |

| SD | standard deviation |

| TBS | Tris-buffered saline |

| TUNEL | terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labelin |

| VCR | vincristine |

References

- B. M. Wiczer and G. Thomas, “Phospholipase D and mTORC1: Nutrients Are What Bring Them Together,” Sci. Signal., vol. 5, no. 217, pp. pe13–pe13, 2012. [CrossRef]

- J. P. Neoptolemos et al., “A Randomized Trial of Chemoradiotherapy and Chemotherapy after Resection of Pancreatic Cancer,” N. Engl. J. Med., vol. 350, no. 12, pp. 1200–1210, 2004. [CrossRef]

- M. Hidalgo, “Pancreatic Cancer,” N. Engl. J. Med., vol. 21, no. 6, pp. 1605–1618, 2010. [CrossRef]

- D. L. Papademetrio et al., “Interplay between autophagy and apoptosis in pancreatic tumors in response to gemcitabine,” Target. Oncol., vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 123–134, 2014. [CrossRef]

- H. A. Burris et al., “Improvements in survival and clinical benefit with gemcitabine as first-line therapy for patients with advanced pancreas cancer: a randomized trial.,” J. Clin. Oncol., vol. 15, no. 6, pp. 2403–13, 1997. [CrossRef]

- S. Pestka, J. A. Langer, K. C. Zoon, and C. E. Samuel, “Interferons and their actions.,” Annu. Rev. Biochem., vol. 56, pp. 727–77, 1987. [CrossRef]

- H. Schmeisser et al., “Type I interferons induce autophagy in certain human cancer cell lines,” Autophagy, vol. 9, no. 5, pp. 683–696, 2013. [CrossRef]

- E. C. Borden et al., “Interferons at age 50: past, current and future impact on biomedicine,” Nat. Rev. Drug Discov., vol. 6, no. 12, pp. 975–990, 2007. [CrossRef]

- L. C. Platanias, “Mechanisms of type-I- and type-II-interferon-mediated signalling,” Nat. Rev. Immunol., vol. 5, no. 5, pp. 375–386, 2005. [CrossRef]

- G. R. Stark and J. E. Darnell, “The JAK-STAT pathway at twenty,” Immunity, vol. 36, no. 4, pp. 503–514, Apr. 2012. [CrossRef]

- L. B. Ivashkiv and L. T. Donlin, “Regulation of type I interferon responses,” Nat. Rev. Immunol., vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 36–49, Jan. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Y. Li et al., “Role of p38alpha Map kinase in Type I interferon signaling.,” J. Biol. Chem., vol. 279, no. 2, pp. 970–979, 2004. [CrossRef]

- S. Kaur, E. Katsoulidis, and L. C. Platanias, “Akt and mRNA translation by interferons,” Cell Cycle, vol. 7, no. 14, pp. 2112–2116, 2008. [CrossRef]

- S. Kaur et al., “Regulatory effects of mTORC2 complexes in type I IFN signaling and in the generation of IFN responses.,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., vol. 109, no. 20, pp. 7723–8, 2012. [CrossRef]

- B. Kroczynska, S. Kaur, and L. C. Platanias, “Growth suppressive cytokines and the AKT/mTOR pathway,” Cytokine, vol. 48, no. 1–2, pp. 138–143, 2009. [CrossRef]

- H. Nagano et al., “Interferon-alpha and 5-fluorouracil combination therapy after palliative hepatic resection in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma, portal venous tumor thrombus in the major trunk, and multiple nodules,” Cancer, vol. 110, no. 11, pp. 2493–2501, 2007. [CrossRef]

- H. Bernhard et al., “Treatment of advanced pancreatic cancer with 5-fluorouracil, folinic acid and interferon alpha-2A: results of a phase II trial,” Br J Cancer, vol. 71, no. 1, pp. 102–105, 1995.

- B. Chauffert et al., “Phase III trial comparing intensive induction chemoradiotherapy (60 Gy, infusional 5-FU and intermittent cisplatin) followed by maintenance gemcitabine with gemcitabine alone for locally advanced unresectable pancreatic cancer. Definitive results of the 2,” Ann. Oncol., vol. 19, no. 9, pp. 1592–1599, 2008. [CrossRef]

- V. J. Picozzi, R. A. Kozarek, and L. W. Traverso, “Interferon-based adjuvant chemoradiation therapy after pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma,” in American Journal of Surgery, 2003, vol. 185, no. 5, pp. 476–480. [CrossRef]

- Y. Tomimaru et al., “Synergistic antitumor effect of interferon-ss with gemcitabine in interferon-alpha-non-responsive pancreatic cancer cells,” Int J Oncol, vol. 38, no. 5, pp. 1237–1243, 2011. [CrossRef]

- N. Mizushima, T. Yoshimori, and Y. Ohsumi, “The Role of Atg Proteins in Autophagosome Formation,” Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol., no. 27, pp. 107–32, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Y. Chen and D. J. Klionsky, “The regulation of autophagy – unanswered questions,” J Cell Sci., vol. 124, no. 124(Pt 2), pp. 161–70, 2011. [CrossRef]

- D. Schmid and C. Münz, “Innate and Adaptive Immunity through Autophagy,” Immunity, vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 11–21, 2007. [CrossRef]

- M. New and S. Tooze, “The Role of Autophagy in Pancreatic Cancer-Recent Advances,” Biology (Basel)., vol. 9, no. 1, p. 7, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- K. Görgülü et al., “The Role of Autophagy in Pancreatic Cancer: From Bench to the Dark Bedside,” Cells, vol. 9, no. 4, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Piffoux, E. Eriau, and P. A. Cassier, “Autophagy as a therapeutic target in pancreatic cancer,” Br. J. Cancer, vol. 124, no. 2, pp. 333–344, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. H. Eng et al., “Macroautophagy is dispensable for growth of KRAS mutant tumors and chloroquine efficacy,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., vol. 113, no. 1, pp. 182–187, Jan. 2016. [CrossRef]

- K. Degenhardt et al., “Autophagy promotes tumor cell survival and restricts necrosis, inflammation, and tumorigenesis,” Cancer Cell, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 51–64, 2006. [CrossRef]

- Criollo et al., “IKK connects autophagy to major stress pathways,” Autophagy, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 189–191, 2010. [CrossRef]

- N. Hay, “The Akt-mTOR tango and its relevance to cancer,” Cancer Cell, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 179–83, 2005. [CrossRef]

- T. Panaretakis, L. Hjortsberg, K. P. Tamm, A. C. Bjorklund, B. Joseph, and D. Grander, “IFN{alpha} Induces Nucleus-independent Apoptosis by Activating ERK1/2 and JNK Downstream of PI3K and mTOR,” Mol Biol Cell, vol. 46, no. 8, 2007, [Online]. Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=17942603.

- S. F. Lei H, Furlong PJ, Ra JH, Mullins D, Cantor R, Fraker DL, “AKT activation and response to interferon-beta in human cancer cells.,” Cancer Biol Ther., vol. 4, no. 7, pp. 709–715, 2005.

- C. H. Yang, A. Murti, S. R. Pfeffer, J. G. Kim, D. B. Donner, and L. M. Pfeffer, “Interferon alpha /beta promotes cell survival by activating nuclear factor kappa B through phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and Akt,” J Biol Chem, vol. 276, no. 17, pp. 13756–61, 2001. [CrossRef]

- D. A. Gewirtz, “The four faces of autophagy: Implications for cancer therapy,” Cancer Res., vol. 74, no. 3, pp. 647–651, 2014. [CrossRef]

- V. Cavaliere, T. Lombardo, S. N. Costantino, L. Kornblihtt, E. M. Alvarez, and G. A. Blanco, “Synergism of arsenic trioxide and MG132 in Raji cells attained by targeting BNIP3, autophagy, and mitochondria with low doses of valproic acid and vincristine,” Eur. J. Cancer, vol. 50, no. 18, pp. 3243–3261, 2014. [CrossRef]

- H. Yano et al., “Interferon alfa receptor expression and growth inhibition by interferon alfa in human liver cancer cell lines,” Hepatology, vol. 29, no. 6, pp. 1708–1717, 1999. [CrossRef]

- D. Murphy, K. M. Detjen, M. Welzel, B. Wiedenmann, and S. Rosewicz, “Interferon-alpha delays S-phase progression in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells via inhibition of specific cyclin-dependent kinases.,” Hepatology, vol. 33, no. 2, pp. 346–56, 2001. [CrossRef]

- H. Yano et al., “Growth inhibitory effects of pegylated IFN alpha-2b on human liver cancer cells in vitro and in vivo.,” Liver Int., vol. 26, no. 8, pp. 964–75, 2006. [CrossRef]

- M. Murata, S. Nabeshima, K. Kikuchi, K. Yamaji, N. Furusyo, and J. Hayashi, “A comparison of the antitumor effects of interferon-alpha and beta on human hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines.,” Cytokine, vol. 33, no. 3, pp. 121–8, 2006,. [CrossRef]

- J. R. Sporn, A. C. J. R. Sporn, A. C. Buzaid, D. Slater, N. Cohen, and B. R. Greenberg, “Treatment of advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma with 5-FU, leucovorin, interferon-alpha-2b, and cisplatin,” Am J Clin Oncol, vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 81–83, 1997.

- F. H. Brembeck et al., “A phase II pilot trial of 13-cis retinoic acid and interferon-alpha in patients with advanced pancreatic carcinoma.,” Cancer, vol. 83, no. 11, pp. 2317–23, 1998.

- H. P. Knaebel et al., “Phase III trial of postoperative cisplatin, interferon alpha-2b, and 5-FU combined with external radiation treatment versus 5-FU alone for patients with resected panreatic adenocarcinoma - CapRI: Study protocol [ISRCTN62866759],” BMC Cancer, vol. 5, 2005. [CrossRef]

- D. J. T. Wagener, J. A. Wils, T. C. Kok, A. Planting, M. L. Couvreur, and B. Baron, “Results of a randomised phase II study of cisplatin plus 5-fluorouracil versus cisplatin plus 5-fluorouracil with alpha-interferon in metastatic pancreatic cancer: an EORTC gastrointestinal tract cancer group trial.,” Eur. J. Cancer, vol. 38, no. 5, pp. 648–653, 2002.

- S. Iwahashi et al., “Histone deacetylase inhibitor augments anti-tumor effect of gemcitabine and pegylated interferon-α on pancreatic cancer cells,” Int J clin Oncol, vol. 16, no. 6, pp. 671–8, 2011. [CrossRef]

- M. Ashrafizadeh, K. Luo, W. Zhang, A. Reza Aref, and X. Zhang, “Acquired and intrinsic gemcitabine resistance in pancreatic cancer therapy: Environmental factors, molecular profile and drug/nanotherapeutic approaches,” Environ. Res., vol. 240, p. 117443, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Zhao et al., “Interferon-alpha-2b induces autophagy in hepatocellular carcinoma cells through Beclin1 pathway.,” Cancer Biol. Med., vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 64–8, 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. Ambjørn, Y. M. Ambjørn, Y. Liu, M. Lees, and M. Jäättelä, “in MCF-7 breast cancer cells counteracts its proapoptotic function,” no. March, pp. 287–302, 2013.

- Y. Li et al., “Suppression of autophagy enhanced growth inhibition and apoptosis of interferon-beta in human glioma cells,” Mol Neurobiol, vol. 47, no. 3, pp. 1000–1010, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Blaauboer, K. Sideras, C. H. J. van Eijck, and L. J. Hofland, “Type I interferons in pancreatic cancer and development of new therapeutic approaches,” Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol., vol. 159, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Ritz, F. Baty, J. C. Streibig, and D. Gerhard, “Dose-Response Analysis Using R,” PLoS One, vol. 10, no. 12, p. e0146021, Dec. 2015. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).