2. Coupling Mechanisms and Theoretical Foundations

The coupling effects of High-Intensity Radiated Fields (HIRF) fundamentally involve the propagation and interaction of electromagnetic fields in free space or within shielding enclosures. Therefore, a thorough understanding of electromagnetic field theory is essential for analyzing HIRF-induced interference and its effects on onboard systems. This section outlines the theoretical foundations of HIRF coupling, providing the necessary background to support the subsequent simulation analysis and experimental validation.

2.1. Coupling Paths of HIRF Interference

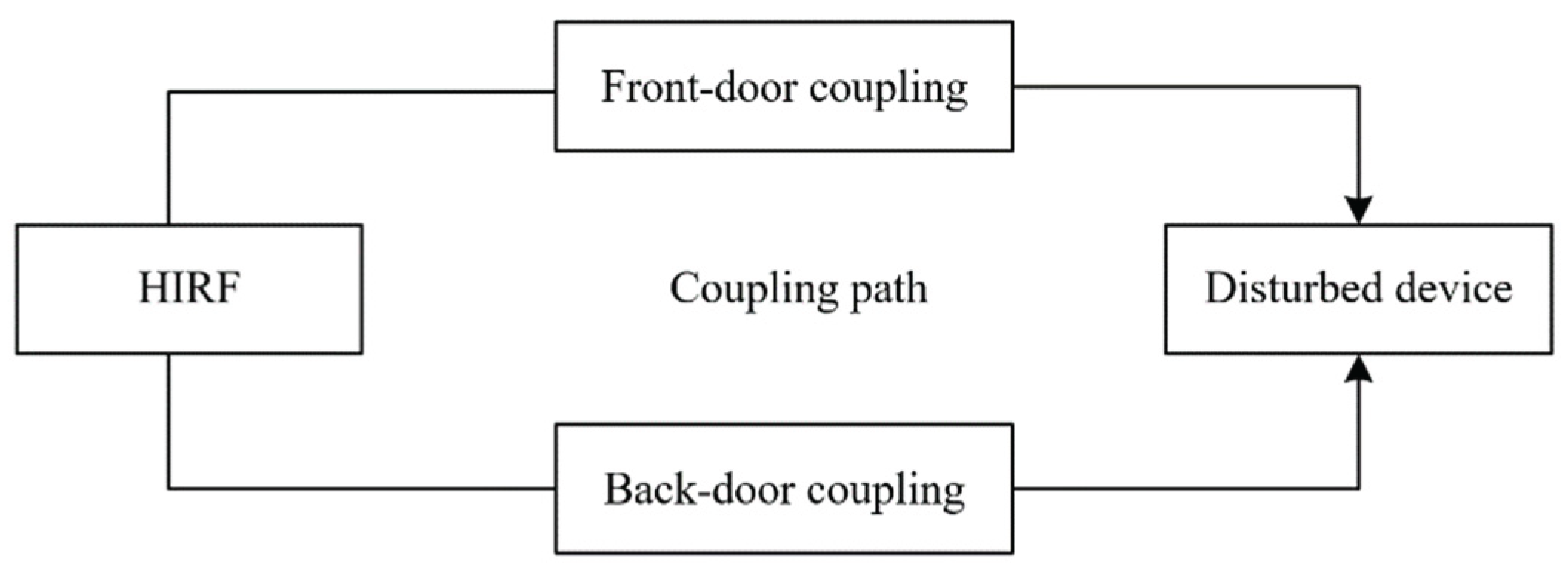

In HIRF environments, electronic equipment is highly susceptible to electromagnetic interference (EMI), which may disrupt normal operation or even lead to complete functional failure. As shown in Figure 2.1, three key elements are required for HIRF-induced interference: a strong external source of radiation, an effective coupling path, and a susceptible victim device.

Figure 1.

Schematic Diagram of HIRF Interference Mechanism.

Figure 1.

Schematic Diagram of HIRF Interference Mechanism.

HIRF sources typically originate from high-power electromagnetic emissions such as radar systems, communication base stations, and broadcast transmitters. The electromagnetic energy from these sources can couple into electronic systems via two primary mechanisms: front-door coupling and back-door coupling.

HIRF energy exhibits different coupling behaviors depending on the frequency band. The HIRF spectrum can generally be divided into three major regions:

Below 1 MHz: Coupling effects are weak and typically negligible for most aircraft systems, requiring no special mitigation measures.

1 MHz to 400 MHz: In this range, aircraft wiring harnesses can act as efficient antennas, making front-door coupling the dominant pathway. Effective cable shielding is particularly critical in this frequency band.

Above 400 MHz: Front-door coupling effects diminish, and HIRF energy more easily enters systems through structural discontinuities and enclosure apertures. In this high-frequency region, back-door coupling becomes the primary mechanism, and the design of enclosures and shielding becomes a key factor in preventing electromagnetic penetration [

21].

As a result, this study primarily focuses on analyzing shielding effectiveness in the HIRF frequency range above 400 MHz, where structural coupling dominates and shielding design plays a crucial role.

2.2. Maxwell’s Equations

Maxwell’s equations are the fundamental mathematical framework for describing electromagnetic fields and the propagation of electromagnetic waves. These four equations collectively define the interactions between electric fields, magnetic fields, electric charges, and electric currents. As the theoretical cornerstone of classical electromagnetics, Maxwell’s equations provide the basis for analyzing wave propagation, radiation, and field interactions in high-intensity radiated field (HIRF) environments.:

In these equations:

denotes the electric field intensity (V/m2),

denotes the current density (A/m2),

denotes the magnetic field intensity (A/m),

denotes the electric displacement vector (C/m2),

denotes the electric charge density (C/m3),

denotes the magnetic flux density (Wb/m2).

Together, Eqs. (1) through (4) form the integral form of Maxwell’s equations, serving as the theoretical basis for all electromagnetic phenomena and determining the fundamental laws governing electromagnetic wave propagation.

2.3. Electromagnetic Shielding Effectiveness

Electromagnetic Shielding Effectiveness (SE) is a critical metric used to evaluate the capability of shielding materials or structures to block the propagation of electromagnetic waves. It describes the effectiveness of materials or structures in reducing external electromagnetic interference (EMI) and preventing leakage of internal electromagnetic radiation. In HIRF environments, electromagnetic shielding effectiveness is especially crucial, particularly for protecting onboard electronic equipment from electromagnetic interference.

Electromagnetic shielding effectiveness refers to the attenuation capability of shielding materials or structures against electromagnetic waves, usually expressed in decibels (dB). It can be calculated as:

Electric Field Shielding Effectiveness:

Magnetic Field Shielding Effectiveness:

Where and represent the electric field strength before and after shielding, respectively; and and represent the magnetic field strength before and after shielding, respectively.

Several factors influence electromagnetic shielding effectiveness, mainly including:

Material properties: The primary factors affecting shielding effectiveness are the electrical conductivity and magnetic permeability of the material. Both conductivity and permeability have a positive correlation with shielding effectiveness.

Shielding structure: The structure of the shield, including its thickness, seams and openings, and other structural characteristics, significantly impacts shielding effectiveness. Generally, a thicker shield offers higher effectiveness. Electromagnetic waves can penetrate through seams and openings, reducing the overall shielding performance. Moreover, certain structural features can induce resonances at specific frequencies, causing significant degradation of shielding effectiveness.

Frequency range: Shielding effectiveness varies with frequency. Between 1 MHz and 400 MHz, cables themselves can act as strong antennas, causing considerable coupling effects. At frequencies above 400 MHz, high-frequency electromagnetic waves are more readily absorbed and reflected by metals and composite materials. Typically, multilayer shielding materials are required to effectively block these waves.

Electromagnetic shielding effectiveness is an important indicator for assessing the efficacy of materials or structures, especially in HIRF environments where it directly relates to the anti-interference capability of onboard equipment. By selecting appropriate materials and optimizing structural design, shielding effectiveness can be significantly improved, thereby reducing the impact of external electromagnetic waves on equipment and ensuring normal system operation.

2.4. Resonance Phenomenon

The resonance phenomenon is a significant factor that can degrade shielding effectiveness in electromagnetic shielding design. When the frequency of an external electromagnetic wave approaches the natural frequency of a shielding structure or material, the system’s response amplitude increases markedly. This leads to enhanced transmission or amplification of electromagnetic waves, causing a substantial reduction in shielding effectiveness.

Every shielding material or structure possesses one or more natural frequencies—referred to as resonant frequencies. In electromagnetic shielding, the geometric shape, dimensions, openings, and gaps of the shielding enclosure have a direct impact on its resonant frequencies. Physical properties such as electrical conductivity and magnetic permeability of the materials also influence the resonance behavior.

For an ideal rectangular resonant cavity made of a perfect conductor, the resonant frequency can be calculated using the following formula:

Where is the resonant frequency of the cavity (Hz), is the speed of light(3*108m/s),,, are the length, width, and height of the cavity(m),,, are positive integers representing the resonance mode numbers.

For a rectangular cavity with a single aperture or slit, the resonant frequency can be adjusted using the following modified formula:

Where is the maximum slit or aperture length in the direction of wave propagation.

When the enclosure of an onboard device contains multiple openings or slits, the resonant frequencies may shift, and multiple resonance peaks may occur due to internal reflections and interference within the cavity. Therefore, in HIRF protection simulation analysis, it is essential to use electromagnetic field simulation software (such as CST) to identify the resonance characteristics of the actual shielding cavity, and to validate the impact of resonance on shielding performance through experimental methods.

The resonance phenomenon directly affects the system’s immunity to interference and its electromagnetic leakage. Different materials and shielding structures exhibit distinct resonance behaviors. Studying these phenomena helps guide the selection of appropriate materials and the design of effective shielding structures. By adjusting parameters such as material thickness, geometry, and aperture size, resonance can be mitigated, thus enhancing shielding performance. In this study, simulation-based analysis of the resonance characteristics of various shielding enclosures is conducted to support design optimization and reduce electromagnetic interference in practical applications.

2.5. Software Selection

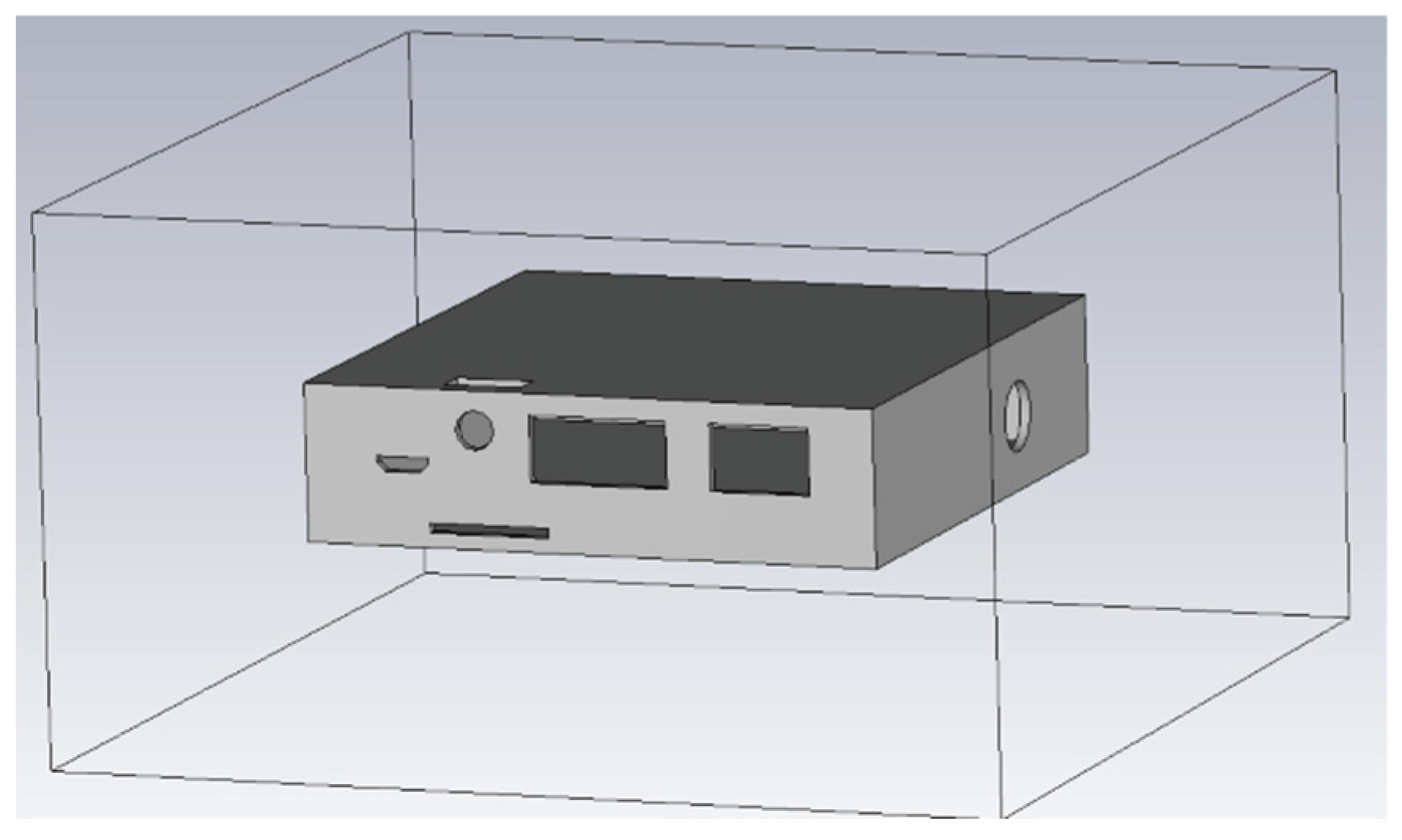

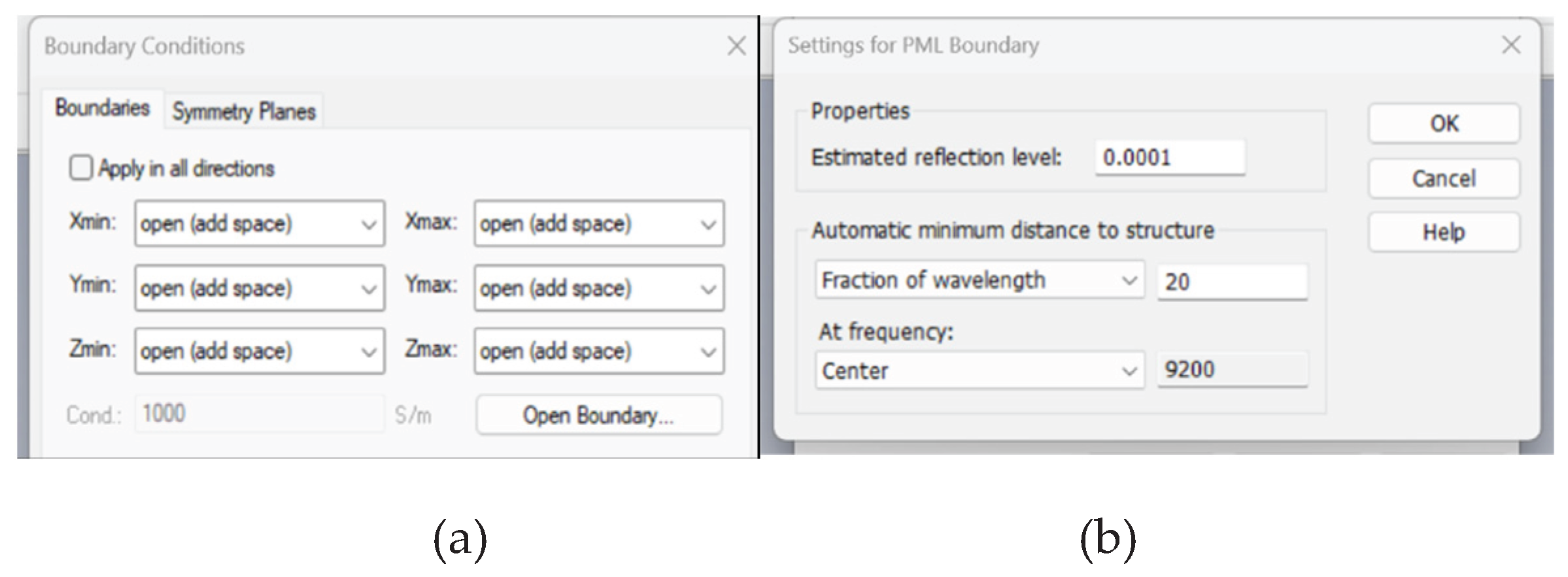

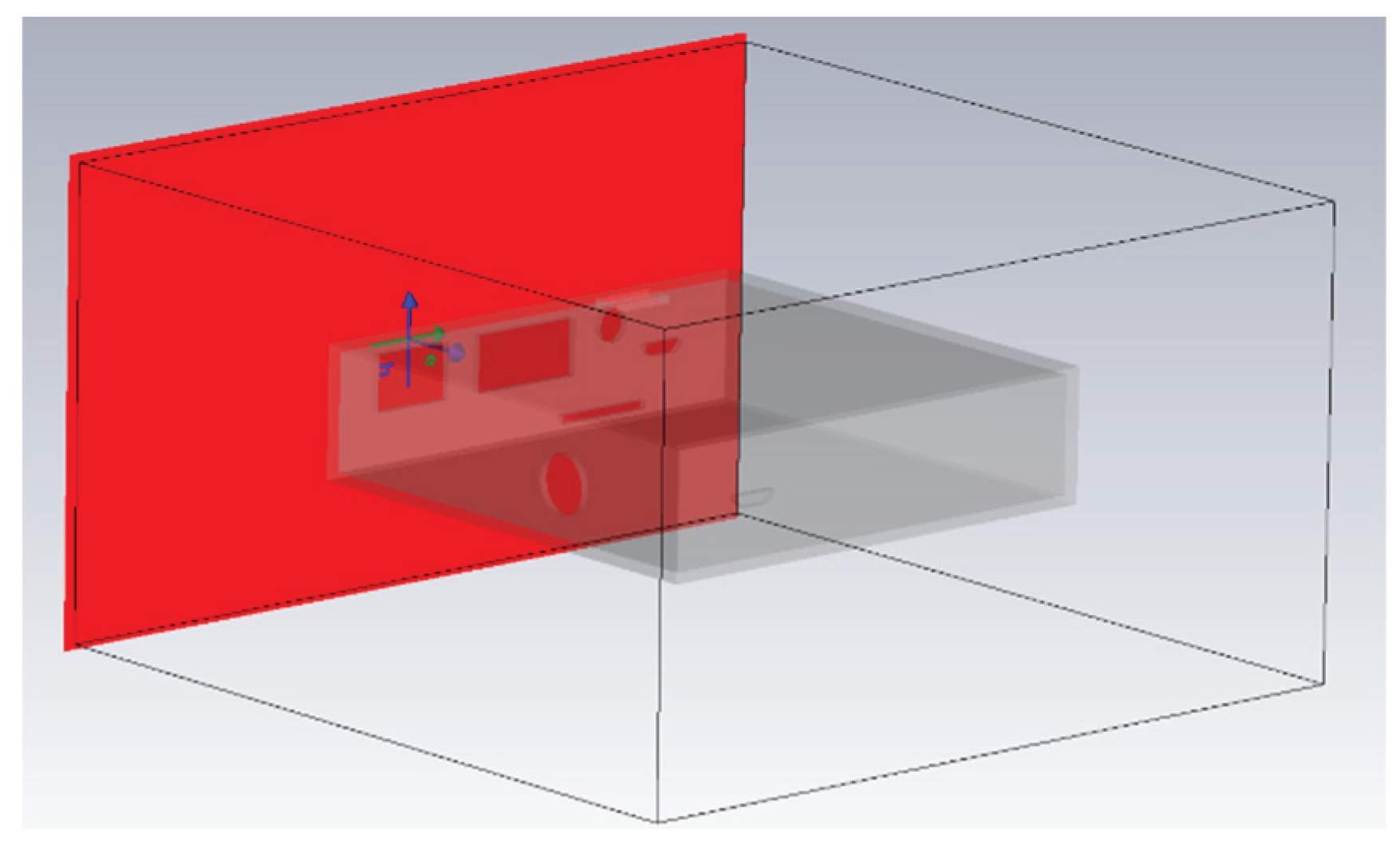

CST Studio Suite is a comprehensive electromagnetic simulation tool capable of handling complex electromagnetic problems under High-Intensity Radiated Fields (HIRF). Its powerful simulation capabilities, multi-frequency analysis, and accurate modeling of electromagnetic wave propagation and shielding effectiveness make it an ideal choice for this study.

By using CST, variations in the shielding effectiveness of the onboard navigation equipment enclosure under different conditions can be effectively analyzed. This enables the prediction of shielding performance during the design phase, facilitates design optimization, and enhances the system’s immunity and reliability in high-intensity electromagnetic environments.

4. Simulation and Results Analysis

4.1. Surface Current Distribution

To gain a deeper understanding of the interaction mechanism between electromagnetic waves and the device enclosure, this section begins by analyzing the surface current distribution at different frequencies.

The distribution characteristics of surface current reflect the coupling strength of external electromagnetic waves to the enclosure as well as the regions where current tends to concentrate. These characteristics serve as important indicators for evaluating shielding effectiveness and identifying potential electromagnetic leakage paths.

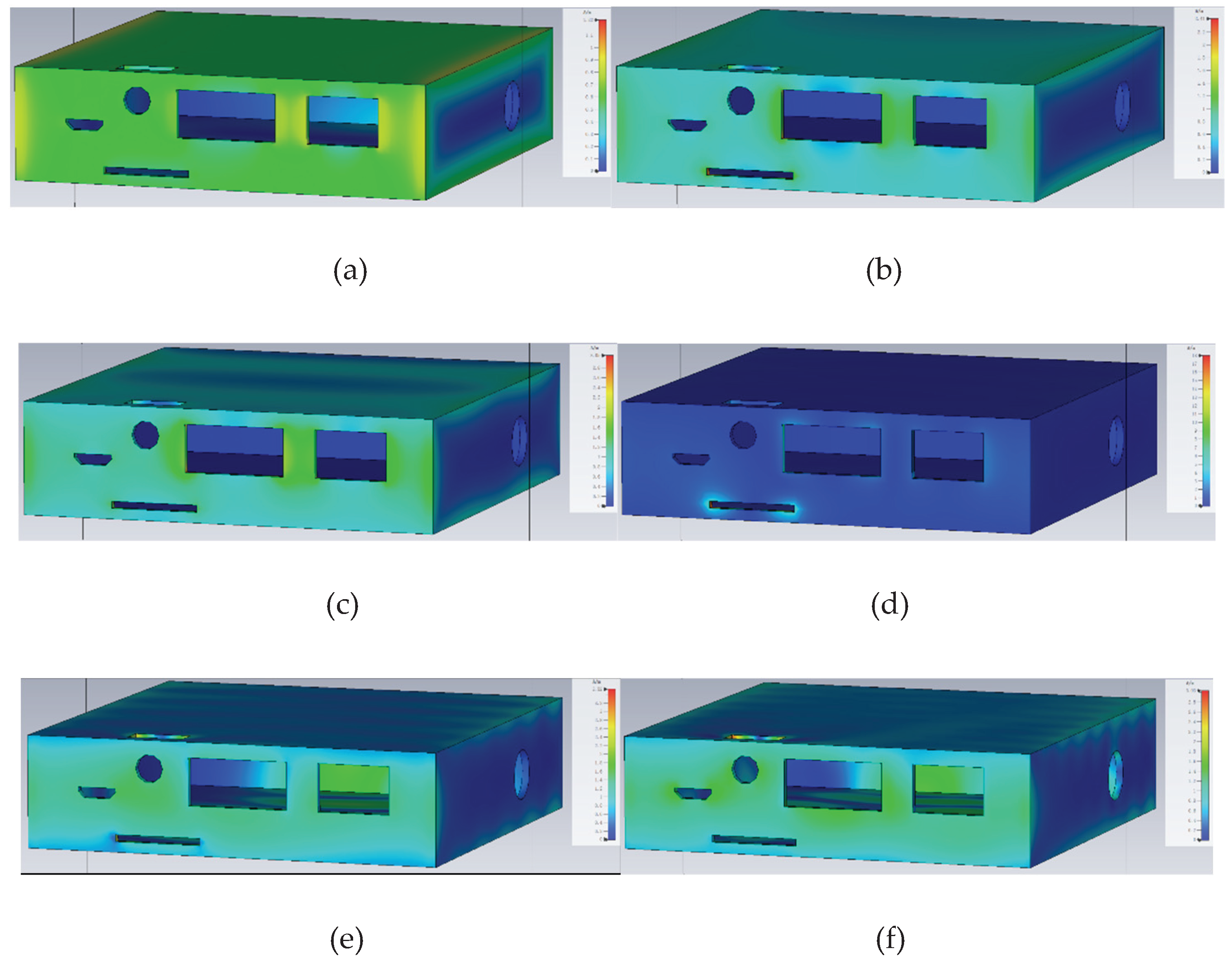

Figure 7 illustrates the surface current distribution on the enclosure at different frequencies. In each subfigure, warmer colors indicate higher current intensity. It is evident that frequency has a significant effect on both the pattern and peak values of surface current distribution.

At 400 MHz, the surface current is relatively uniform, with no strong local concentrations. The maximum current intensity is only 1.22 A/m, and the longer wavelength at this frequency does not effectively couple with the enclosure structure. As a result, shielding effectiveness is relatively high, and the risk of electromagnetic leakage is low.

When the frequency increases to 2000 MHz, the maximum current rises to 2.41 A/m, and localized enhancement begins to appear around aperture edges and areas with structural discontinuities. At 5000 MHz, the current intensity further increases to 3.05 A/m.

At 10,000 MHz, the surface current intensity surges to a peak value of 18 A/m, with significant concentration around multiple front-facing apertures. This suggests that the structure may be experiencing resonance or strong coupling at this frequency, leading to localized shielding failure. Similar trends continue at higher frequencies such as 13,000 MHz and 18,000 MHz, where current hotspots remain concentrated near structural openings and slits.

In general, higher surface current density indicates greater electromagnetic coupling into the interior, resulting in poorer shielding effectiveness. Conversely, areas with low current density correspond to better shielding performance. These results suggest that, in high-frequency HIRF environments, the shielding performance of the enclosure is largely constrained by local coupling at structural discontinuities. Therefore, edge designs, current concentration zones, and seam treatments should be prioritized for optimization to enhance overall shielding effectiveness.

4.2. Effect of Polarization Modes

The polarization direction of an electromagnetic wave directly affects its coupling behavior with structural features such as seams and apertures. This section compares the shielding effectiveness of the enclosure under horizontal and vertical polarization, aiming to reveal how polarization influences coupling paths and resonance phenomena.

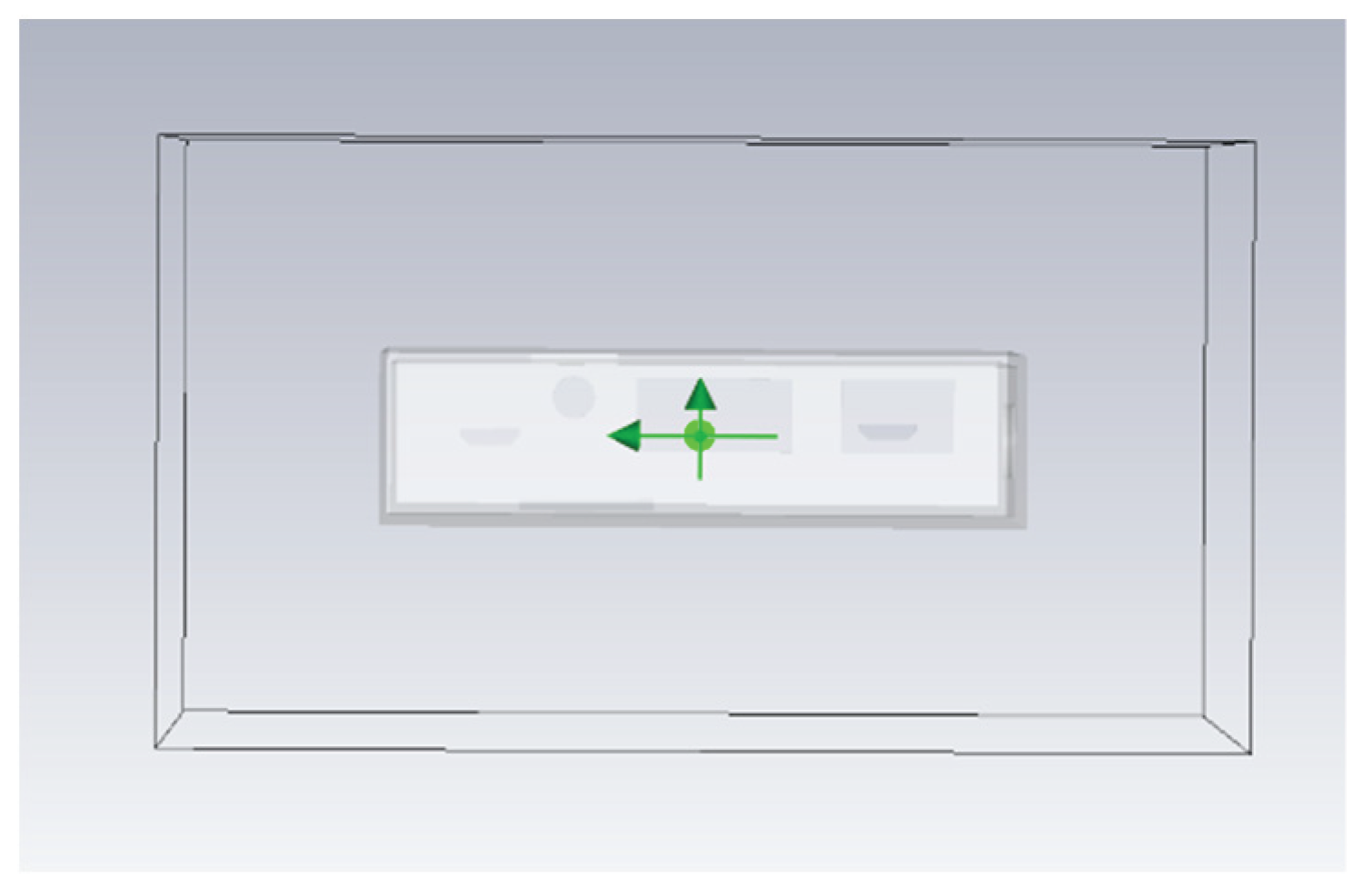

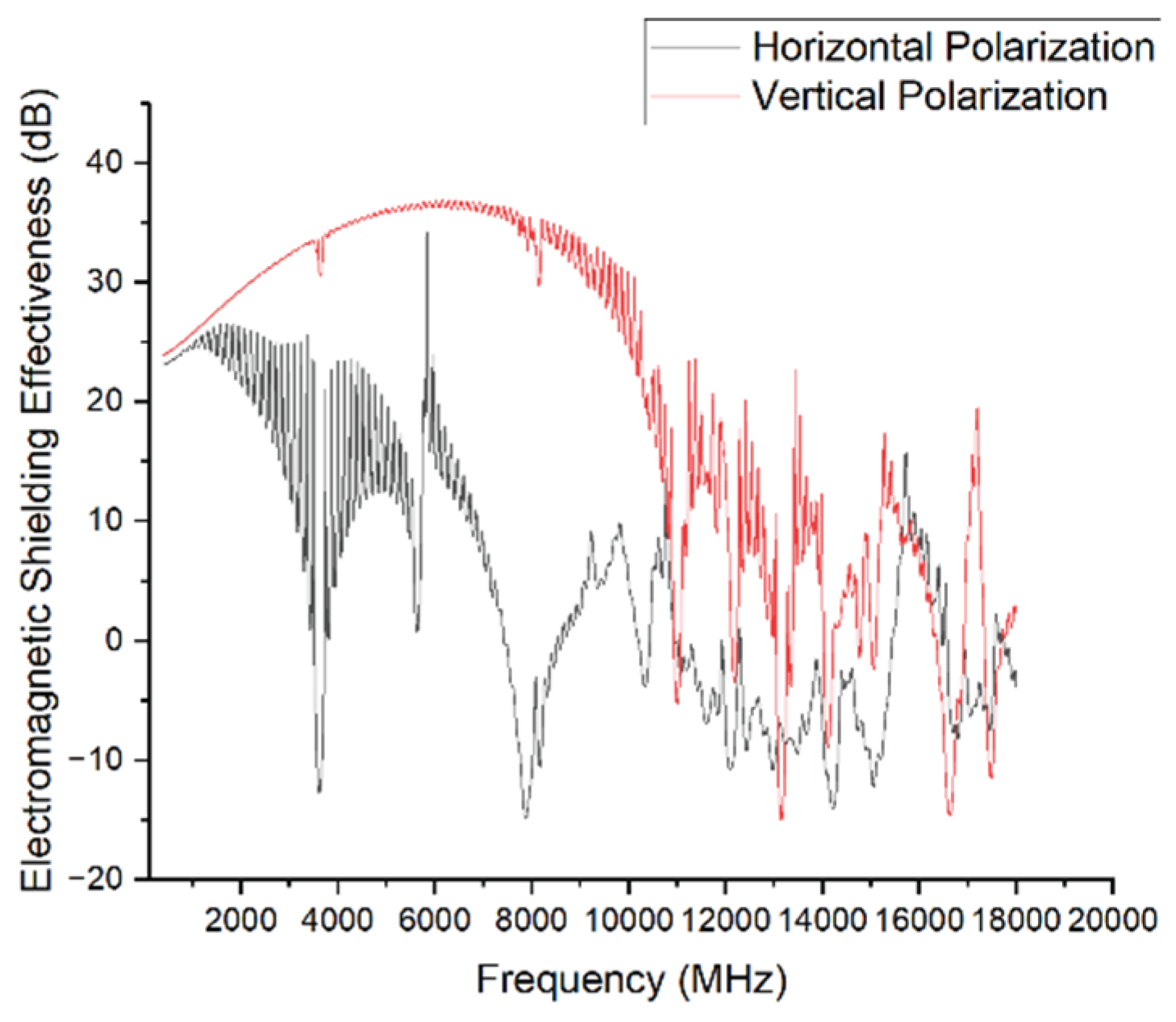

Figure 8.

Simulation results under different polarization modes.

Figure 8.

Simulation results under different polarization modes.

The simulation results show significant differences in shielding effectiveness depending on both frequency and polarization mode.

In the 1–3 GHz range, the shielding effectiveness remains between 20 and 35 dB for both polarizations, with minimal difference between the two.

From 3 to 6 GHz, resonant effects begin to emerge under horizontal polarization, notably near 3.6 GHz and 5.7 GHz, where strong coupling between the polarized waves and the enclosure's gaps and openings causes shielding effectiveness to drop sharply below –10 dB. In contrast, vertical polarization maintains a shielding effectiveness of around 30 dB in the same frequency range.

Within the 6–10 GHz band, the shielding performance under vertical polarization gradually declines, while horizontal polarization briefly recovers but then again exhibits resonance near 8 GHz, causing SE to fall below –10 dB.

Above 10 GHz, both polarization modes experience strong resonance-induced fluctuations, resulting in a significant drop in shielding effectiveness.

Overall, horizontal polarization leads to faster attenuation and a broader frequency range of shielding failure. Therefore, in order to achieve a more stringent assessment and further explore the shielding behavior under worst-case conditions, horizontal polarization is adopted as the standard excitation mode in subsequent simulations.

4.3. Effect of Incidence Angle

In actual High-Intensity Radiated Fields (HIRF) environments, electromagnetic waves may strike the device surface from arbitrary angles. To investigate the influence of incident angle on shielding effectiveness, this section presents simulation analyses at several typical angles to evaluate their impact on shielding performance.

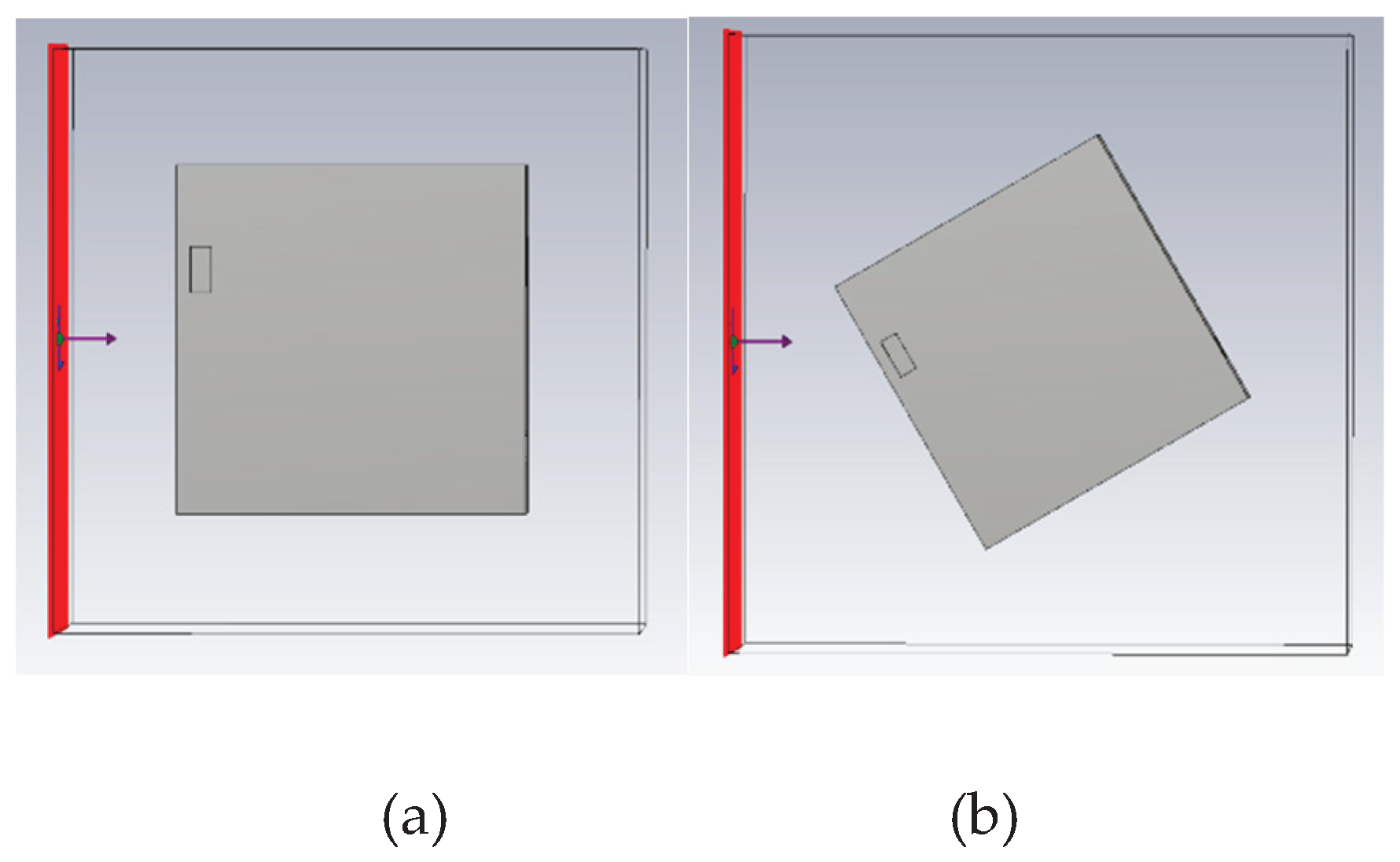

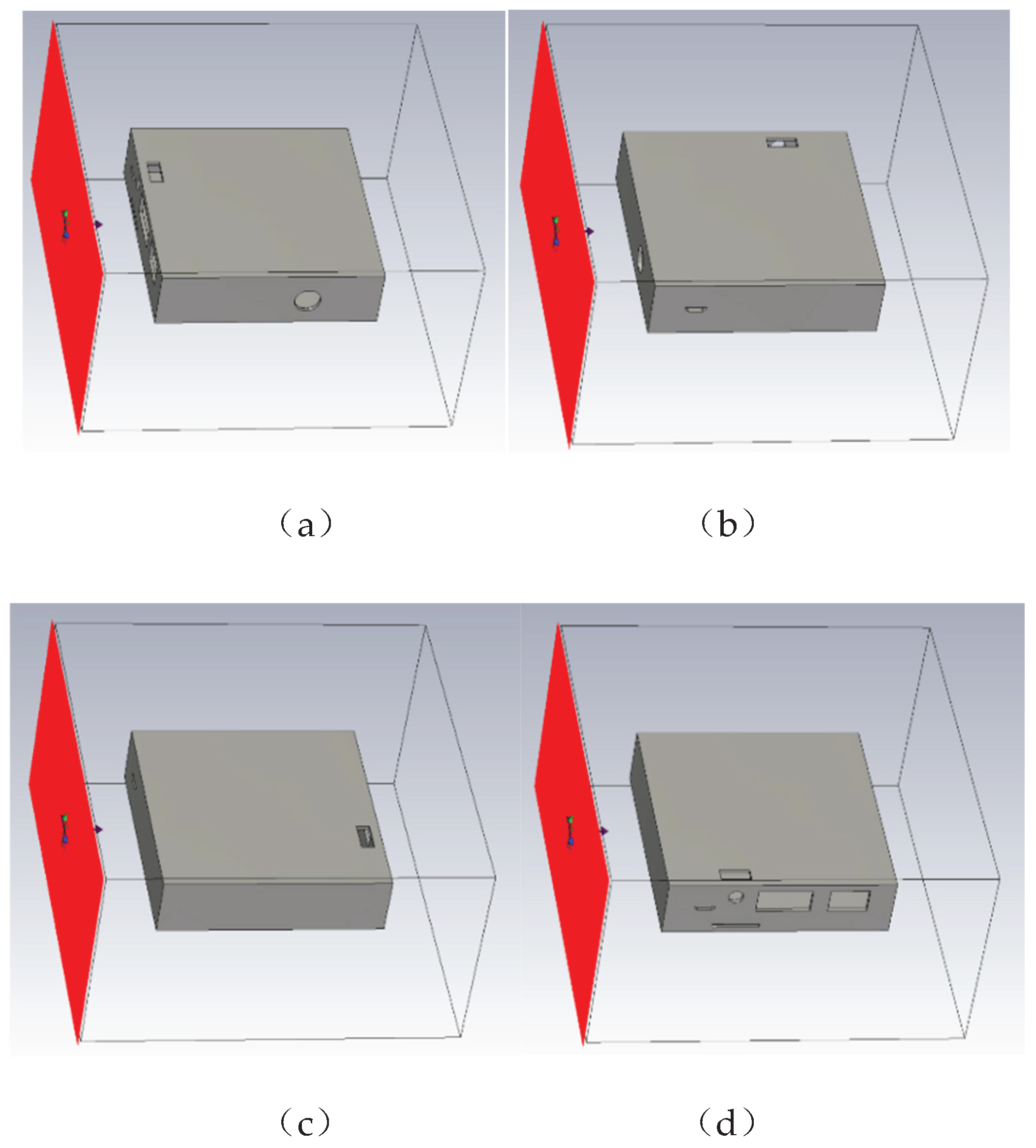

Figure 9.

Illustration of different incidence angles:(a) 0°; (b) 30°; (c) 45°; (d) 60°.

Figure 9.

Illustration of different incidence angles:(a) 0°; (b) 30°; (c) 45°; (d) 60°.

Figure 9.

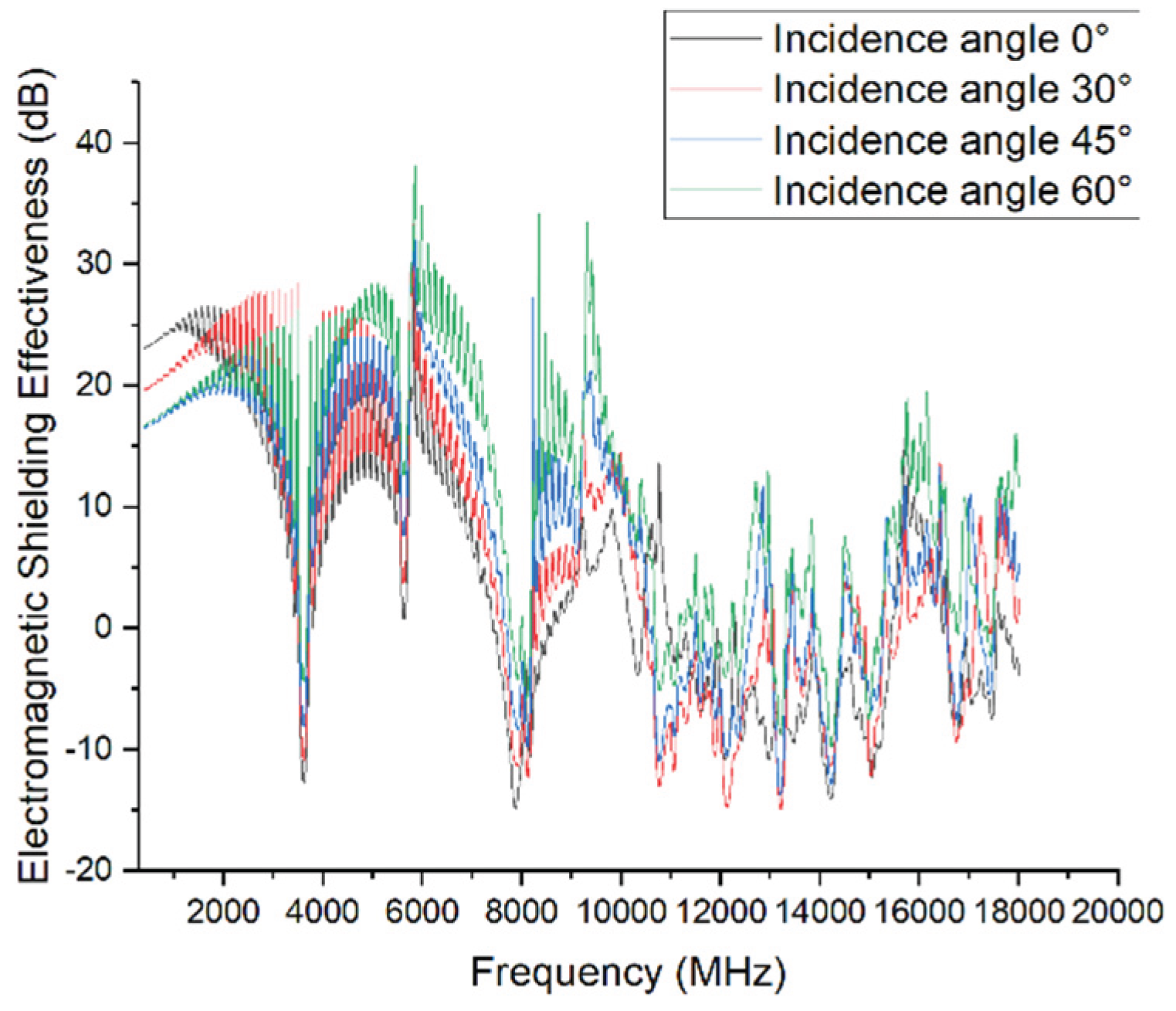

Simulation results for different incidence angles (full frequency range).

Figure 9.

Simulation results for different incidence angles (full frequency range).

Figure 10.

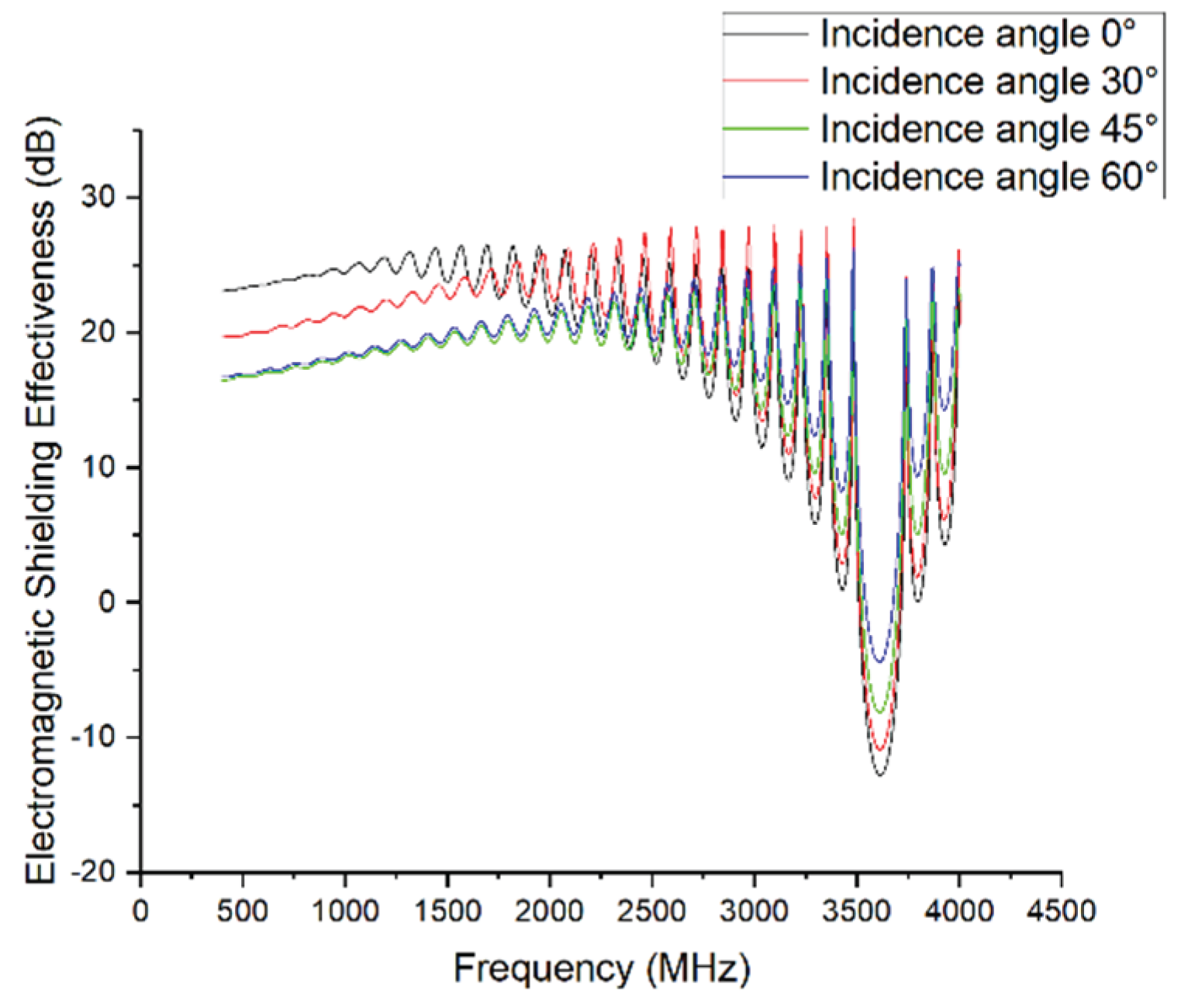

Simulation results for different incidence angles (low-frequency range).

Figure 10.

Simulation results for different incidence angles (low-frequency range).

Figure 11.

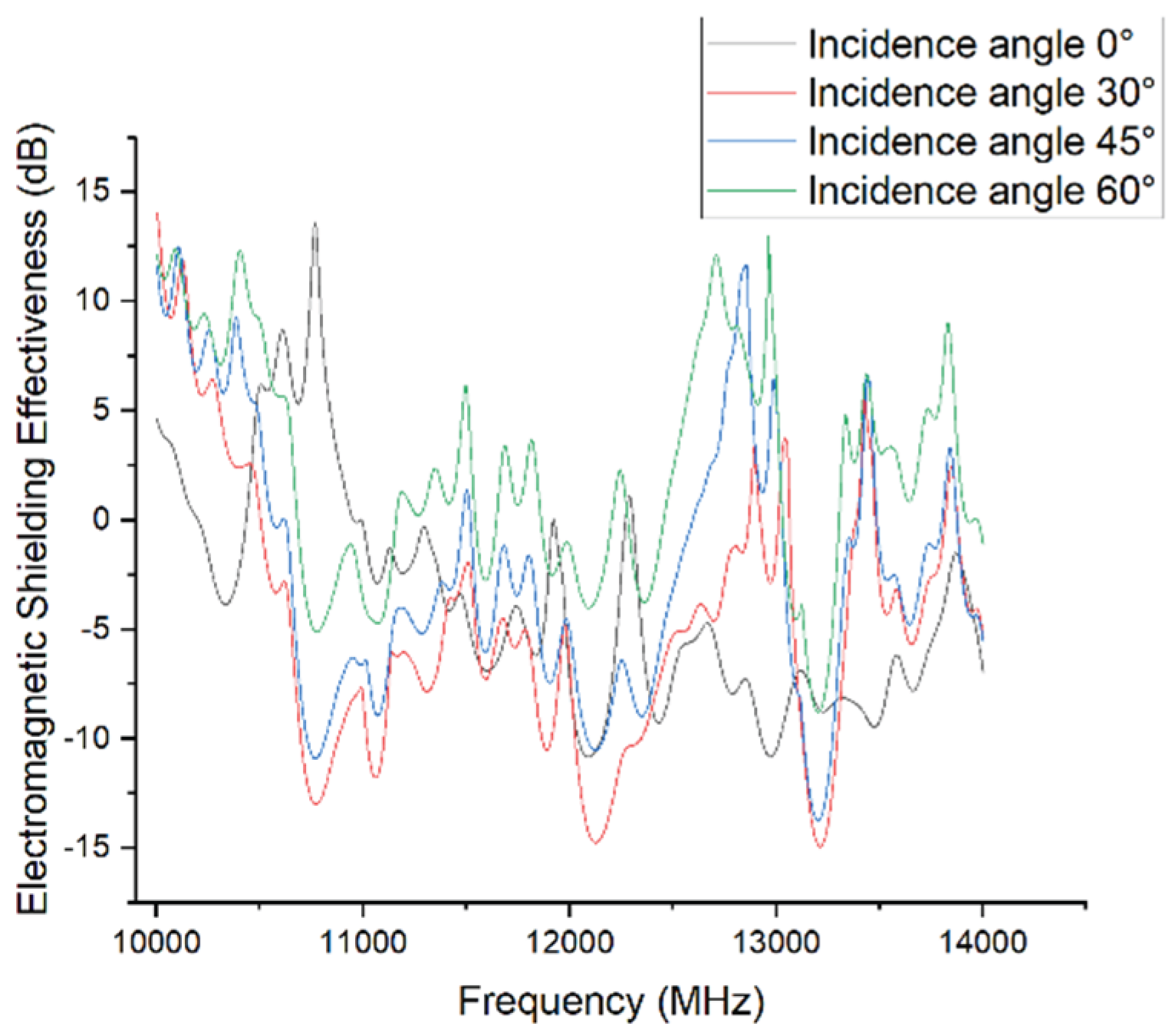

Simulation results for different incidence angles (high-frequency range).

Figure 11.

Simulation results for different incidence angles (high-frequency range).

A comparison of the SE curves at 0°, 30°, 45°, and 60° reveals that the angle sensitivity of shielding effectiveness is most pronounced in the 3–10 GHz range.

Near 3.6 GHz and 8 GHz, clear resonance effects are observed. The shielding effectiveness drops to approximately –10 dB at 0° and 30°, whereas the minima are mitigated to –6 dB and –3 dB at 45° and 60°, respectively. In the 6–8 GHz range, 60° incidence results in a peak SE of nearly 40 dB, which is about 25 dB higher than that of the 0° case, with other angles falling between these extremes.

These results suggest that oblique incidence can weaken the electric field component parallel to enclosure slits, thereby reducing coupling through gaps and apertures.

In contrast, within the 1–3 GHz and above 10 GHz bands, differences among the SE curves become negligible, with variations limited to 2–4 dB. This indicates that the shielding effectiveness is relatively insensitive to incident angle at low frequencies (where the wavelength is much larger than structural features) and at very high frequencies with complex multimode interactions.

In summary, variation in incidence angle mainly affects the resonance bandwidth and peak/valley depth in the mid-frequency range, while its influence on broadband average shielding effectiveness remains limited.

4.4. Effect of Incident Surface

Different surfaces of the enclosure exhibit varying structural features and aperture distributions, resulting in significant differences in their ability to withstand external electromagnetic radiation. This section compares several typical incident surfaces to analyze how surface structure determines shielding effectiveness, thereby providing a reference for future structural optimization.

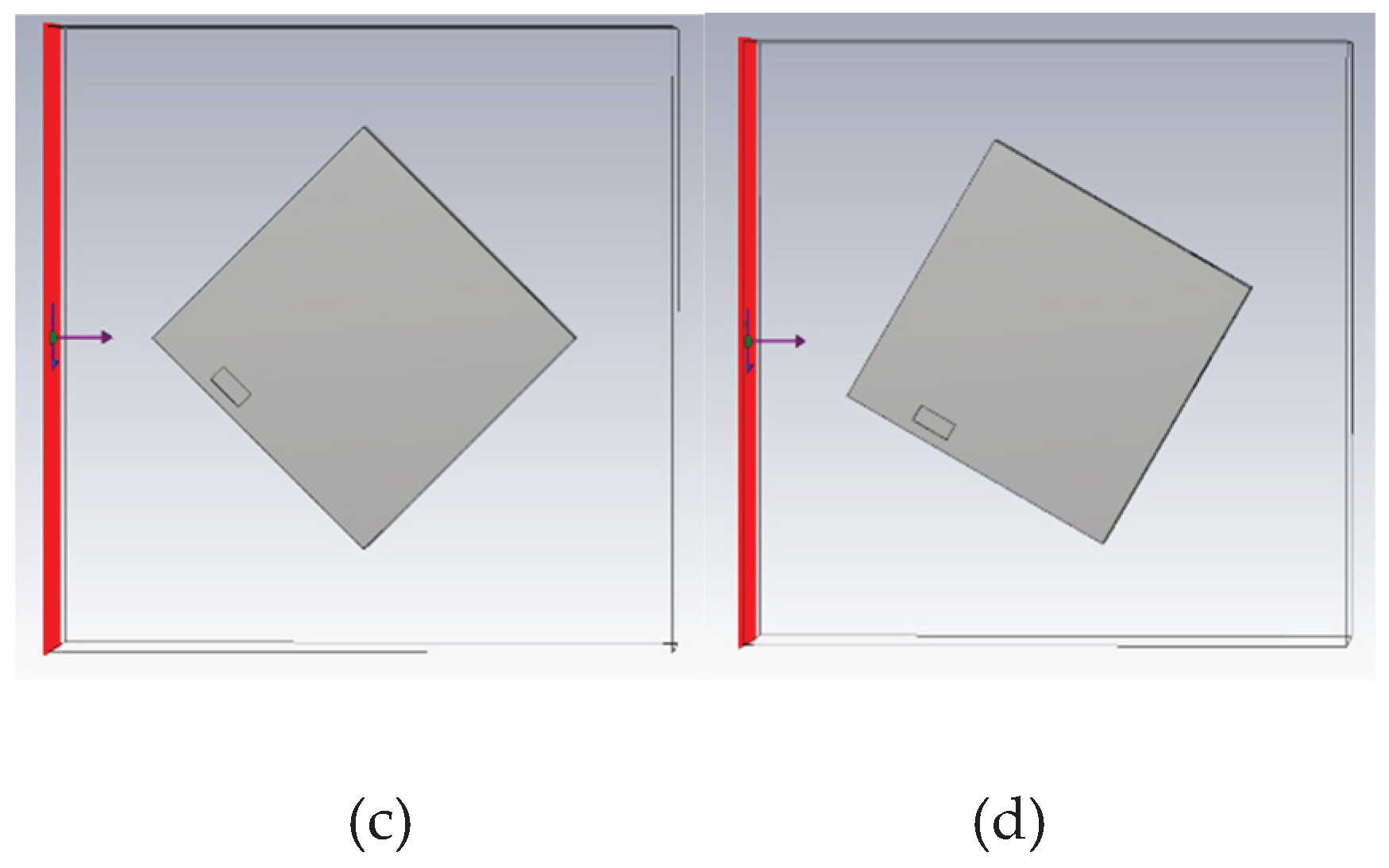

Figure 12.

Illustration of different incident surfaces: (a) Surface A; (b) Surface B; (c) Surface C; (d) Surface D.

Figure 12.

Illustration of different incident surfaces: (a) Surface A; (b) Surface B; (c) Surface C; (d) Surface D.

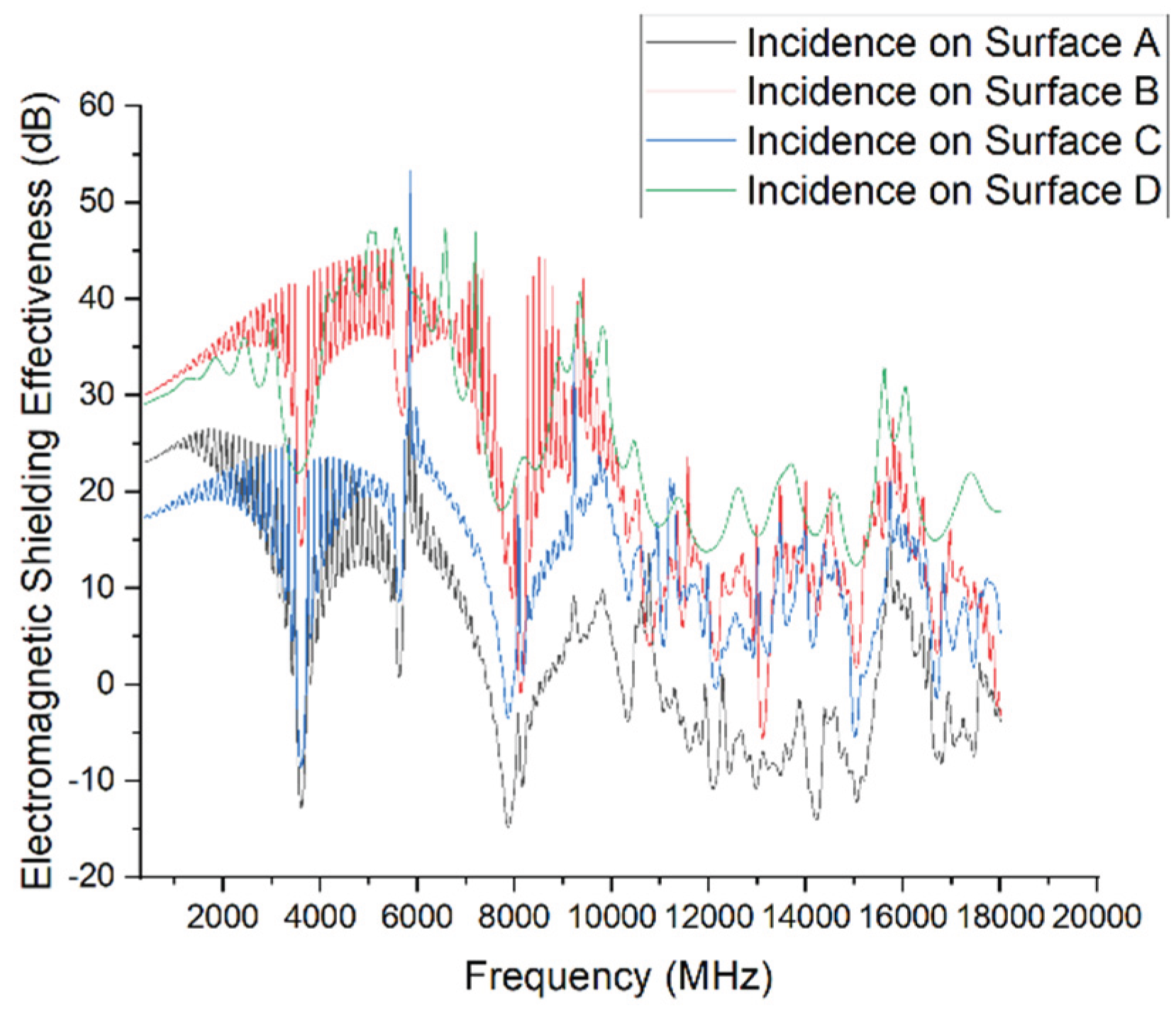

Figure 13.

Simulation results for different incident surfaces (full frequency range).

Figure 13.

Simulation results for different incident surfaces (full frequency range).

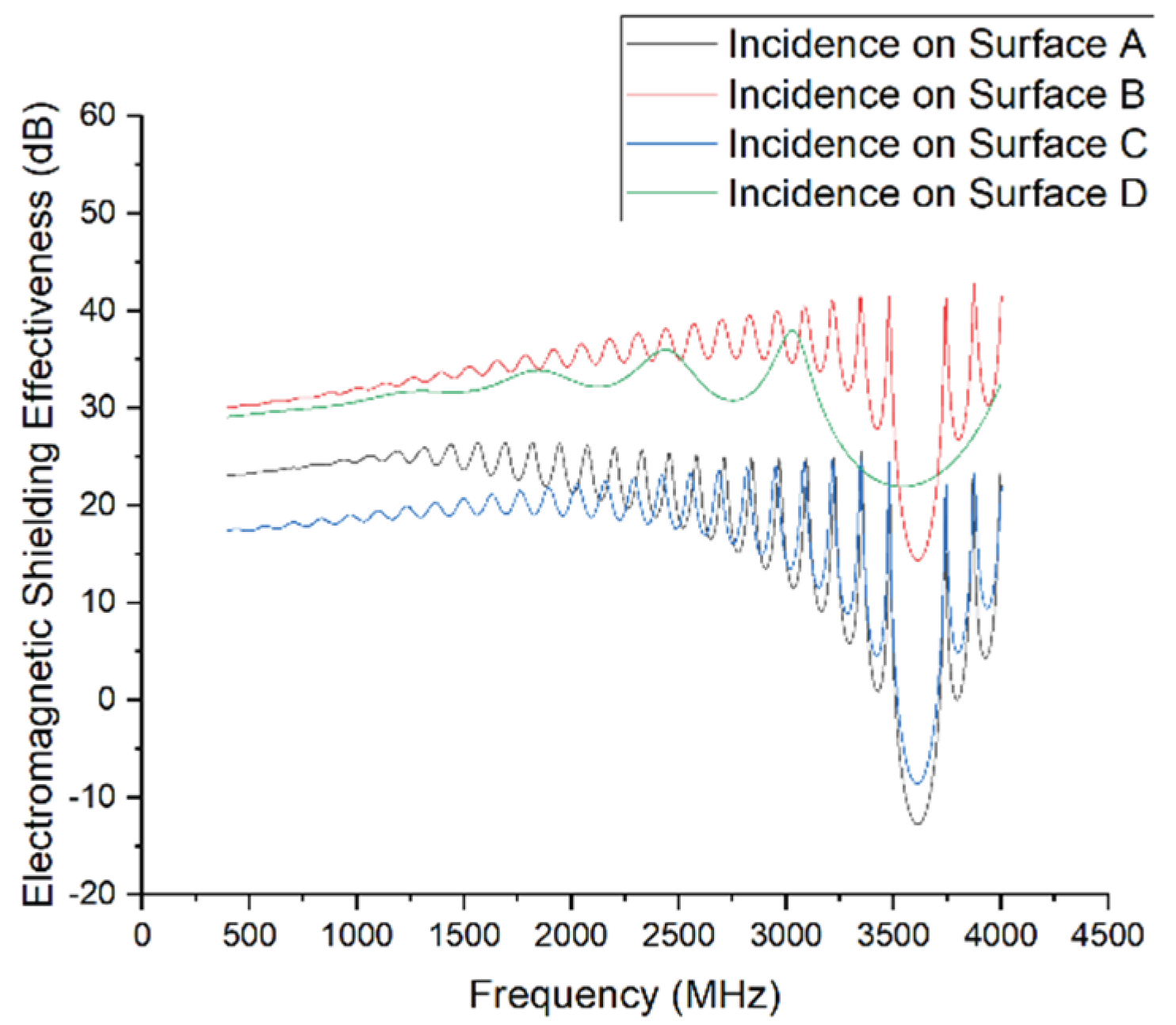

Figure 14.

Simulation results for different incident surfaces (low-frequency range).

Figure 14.

Simulation results for different incident surfaces (low-frequency range).

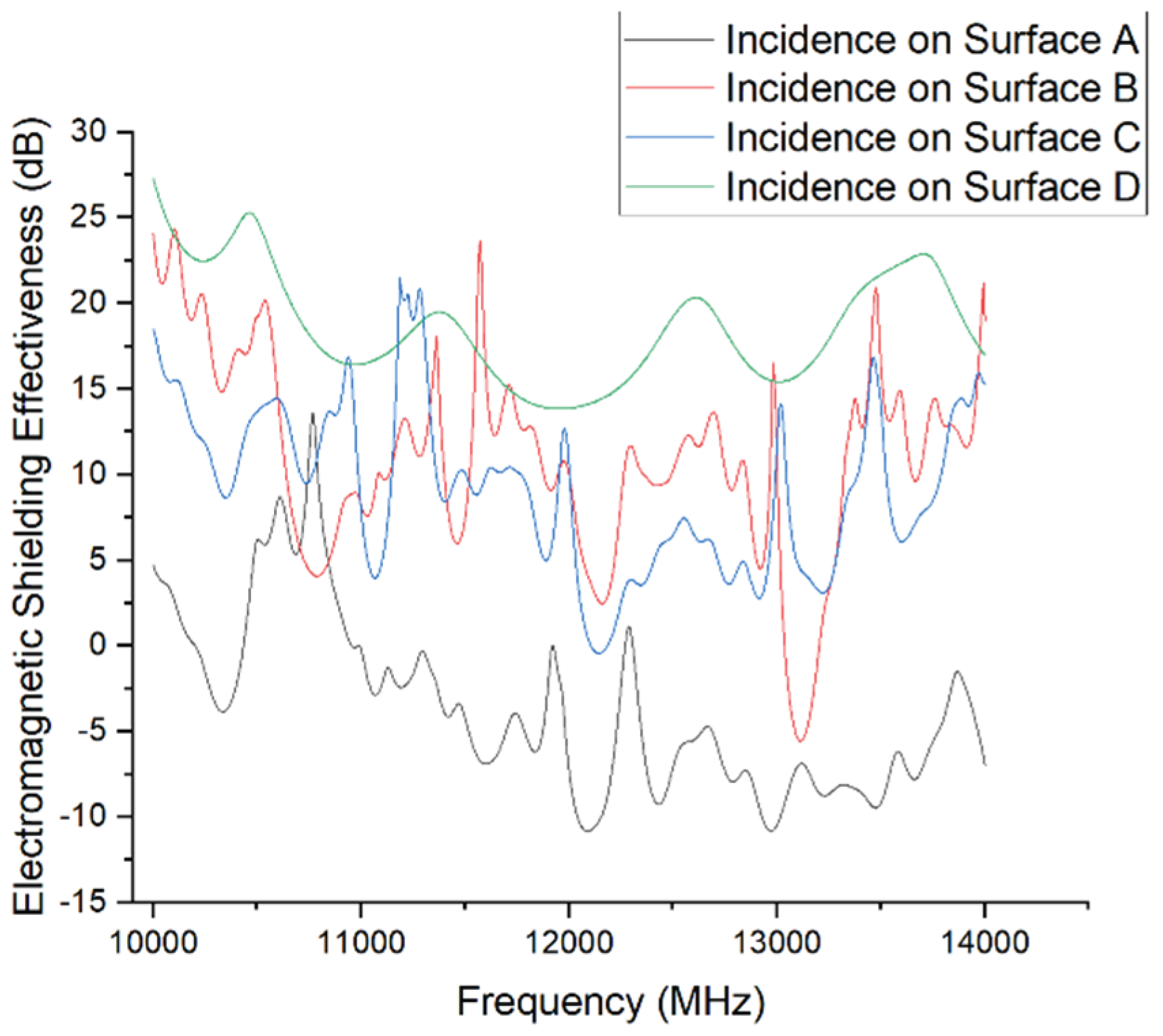

Figure 15.

Simulation results for different incident surfaces (high-frequency range).

Figure 15.

Simulation results for different incident surfaces (high-frequency range).

The simulation results indicate that shielding effectiveness varies significantly with the incident surface, especially in the mid-to-high frequency range (3–12 GHz).

Among the cases, Surface A exhibits the worst shielding performance, with pronounced resonances at approximately 3.6 GHz and 7.8 GHz, where SE drops as low as –15 dB. Across the 3–10 GHz range, the SE fluctuates between 0 and 20 dB, consistently lower than that of the other surfaces. This poor performance is closely related to the multiple structural apertures on Surface A, which facilitate electromagnetic coupling into the enclosure through gaps and holes, leading to shielding failure.

In contrast, Surface B performs better, with only a slight SE dip (minimum around 10 dB) in the 5–7 GHz range, and no significant resonance across the rest of the spectrum. Overall, it demonstrates good shielding performance.

Surface C, though containing only one trapezoidal opening, has a relatively long horizontal dimension. Combined with horizontal polarization excitation, this promotes coupling with the electric field, resulting in a notable SE decrease between 4 and 7 GHz, reaching a minimum of approximately 5 dB. Its overall performance is slightly better than that of Surface A.

Surface D delivers the best shielding effectiveness across the entire frequency range, maintaining SE above 30 dB between 3 and 10 GHz, with some frequency points exceeding 40 dB. This highlights that a structurally intact surface without visible gaps or apertures is crucial for stable shielding performance.

In summary, the number and size of apertures are key factors influencing shielding effectiveness. Surfaces with multiple openings (e.g., Surface A) can trigger strong resonant coupling at various frequencies, leading to substantial SE degradation. Conversely, surfaces with no openings (e.g., Surface D) consistently exhibit superior shielding performance across the spectrum.

4.5. Effect of Material Properties

Material properties such as electrical conductivity, magnetic permeability, and dielectric constant are among the core factors influencing electromagnetic shielding effectiveness (SE). This section compares several representative materials, including typical metals and composite materials, through simulation

The electromagnetic shielding performance of a material is primarily determined by its electromagnetic characteristics, including relative permittivity (), relative permeability (), and electrical conductivity (). The parameters used in the simulation for various materials are listed below:

Table 1.

Electromagnetic properties of different materials.

Table 1.

Electromagnetic properties of different materials.

| Material |

|

|

(s/m)

|

| Perfect Electric Conductor (PEC) |

1 |

1 |

∞ |

| Iron |

1 |

5000 |

1e6 |

| Aluminum |

1 |

1 |

3.5e7 |

| Copper |

1 |

1 |

5.8e7 |

| Carbon Fiber |

3 |

1 |

1e4 |

| Stainless Steel |

1 |

600 |

1e6 |

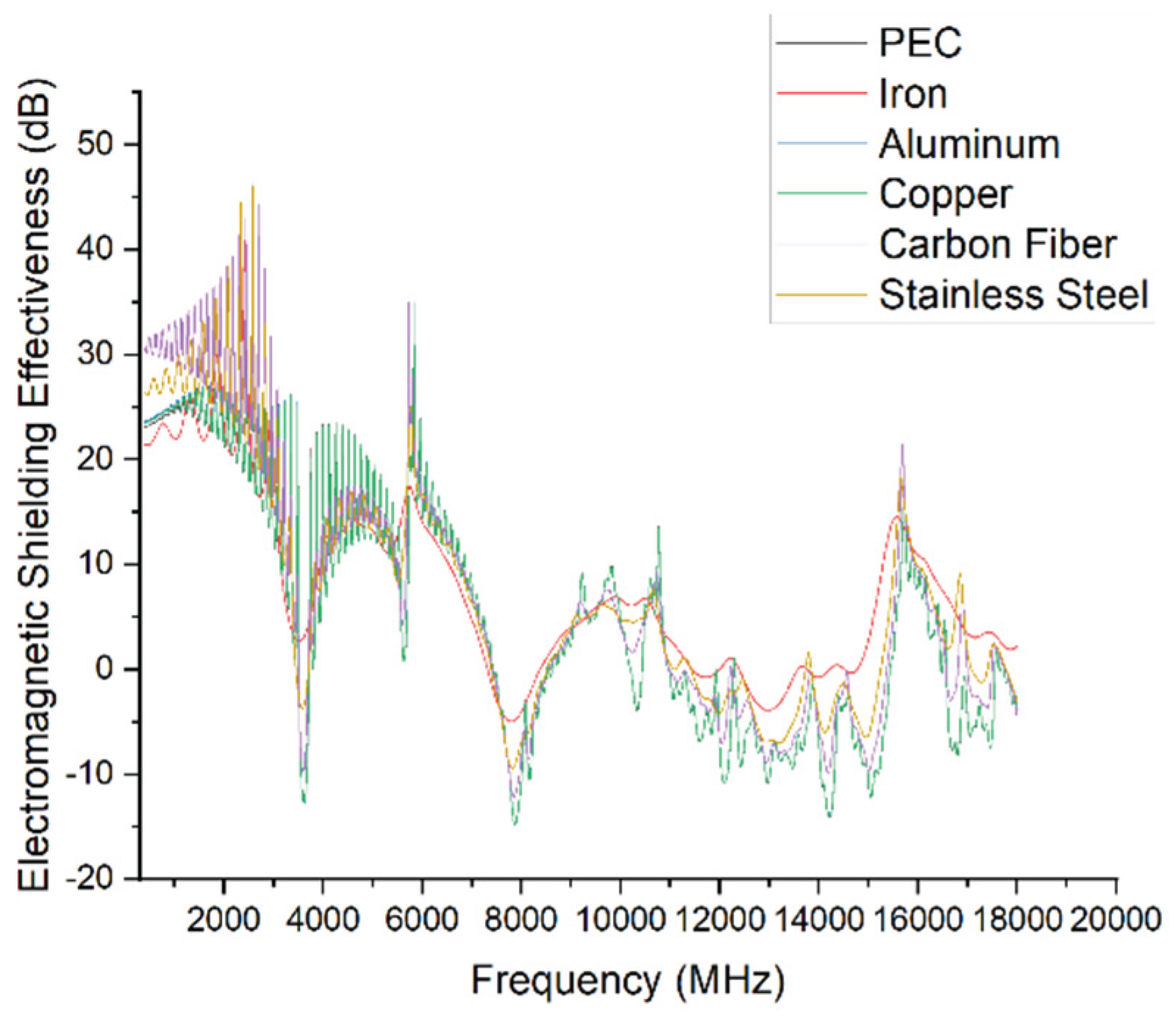

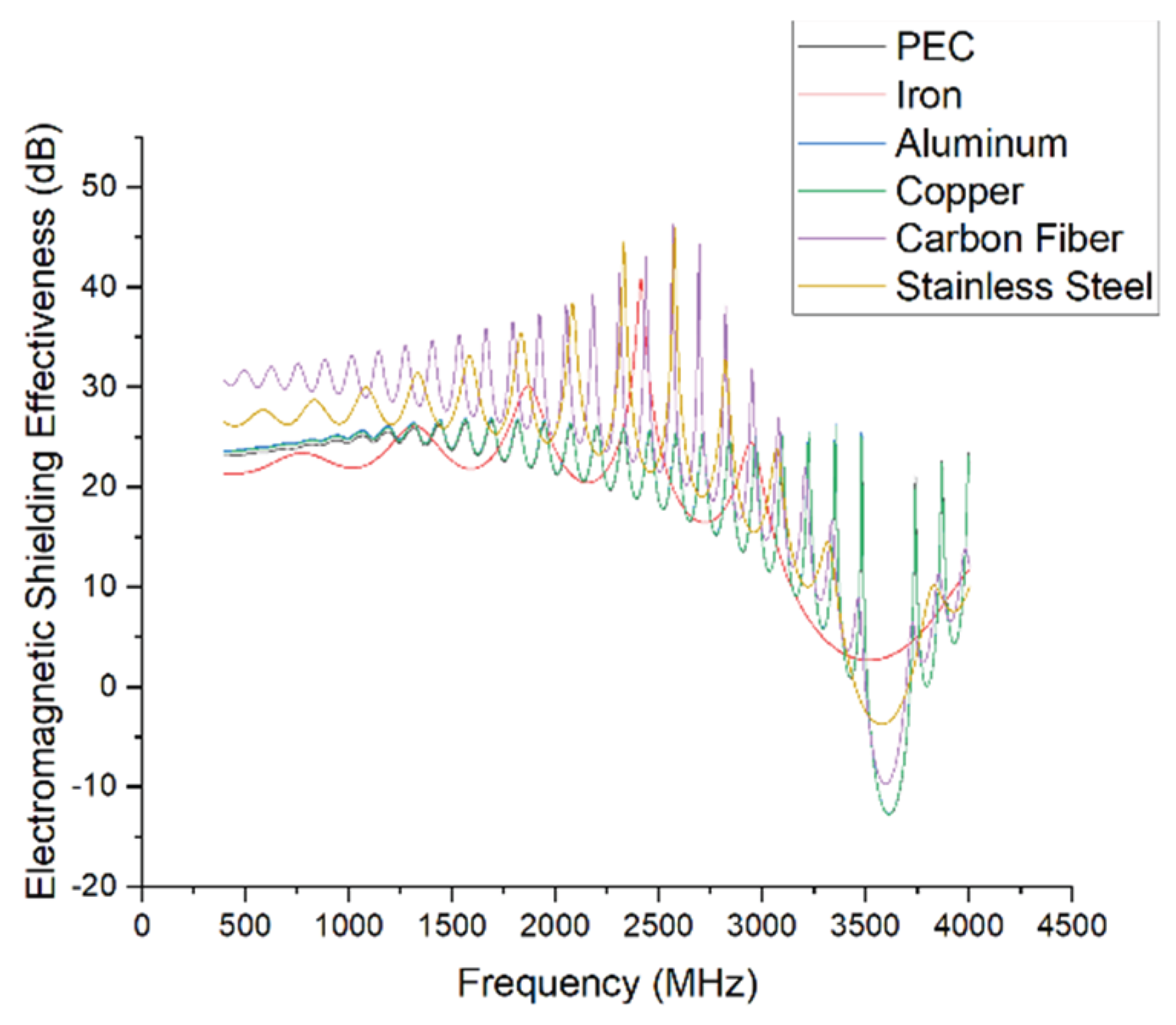

Figure 16.

Simulation results of different materials (full frequency range).

Figure 16.

Simulation results of different materials (full frequency range).

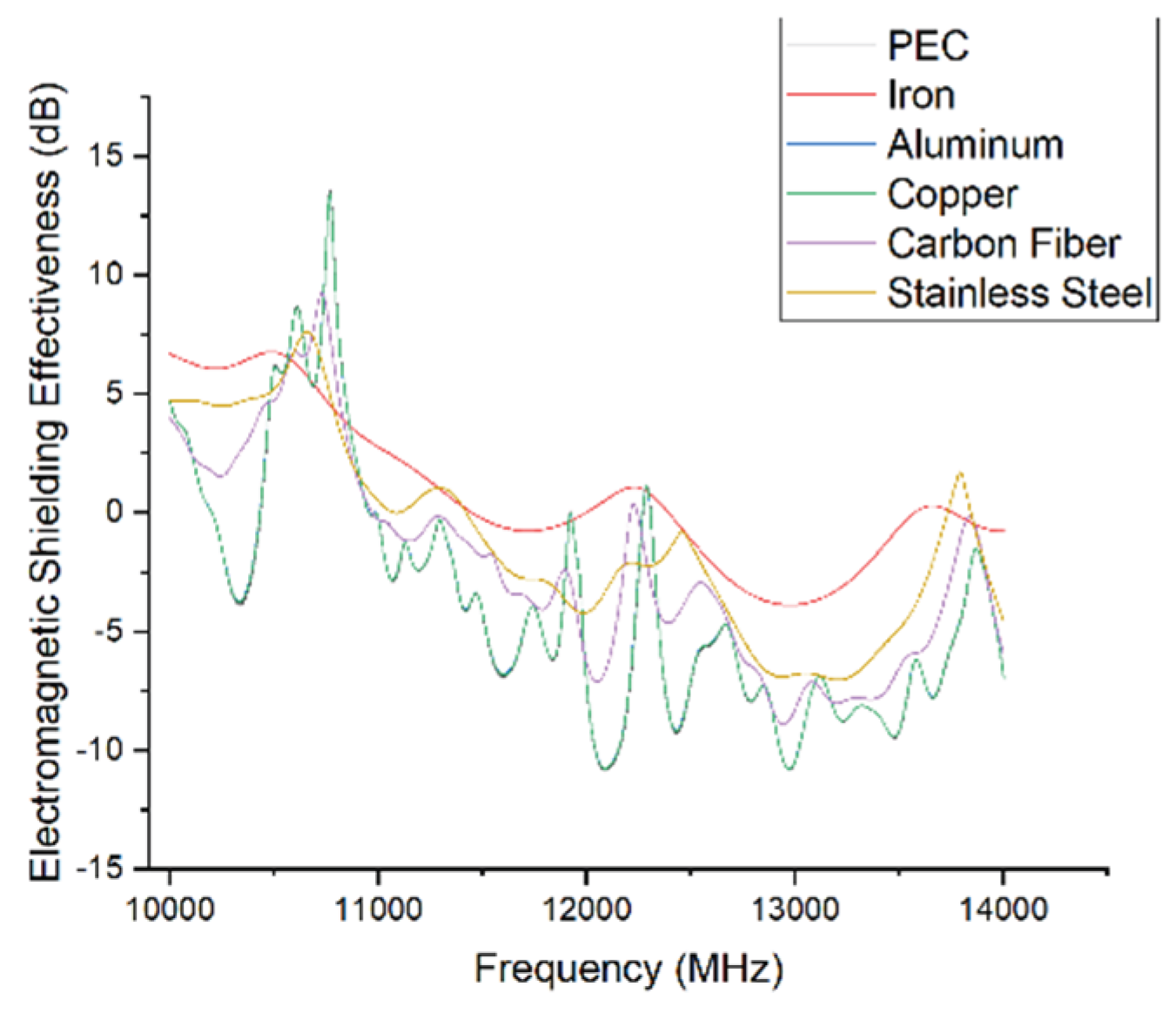

Figure 17.

Simulation results of different materials (low-frequency range).

Figure 17.

Simulation results of different materials (low-frequency range).

Figure 18.

Simulation results of different materials (high-frequency range).

Figure 18.

Simulation results of different materials (high-frequency range).

The simulation results show that while the overall trend of shielding effectiveness is similar across different materials, the SE degradation during resonance and the degree of fluctuation vary significantly.

Copper, aluminum, and the perfect electric conductor (PEC) exhibit very similar performance due to their high conductivity. Their SE curves largely overlap and show sharp dips near 3.6 GHz and 8 GHz, with minimum SE values dropping to approximately 15 dB, indicating severe resonance.

Carbon fiber performs best in the low-frequency range (<3 GHz) but shows greater fluctuation overall. It displays slightly better SE than copper, aluminum, and PEC in resonance zones and in the high-frequency region (>10 GHz).

Iron also exhibits resonances near 3.6 GHz and 8 GHz, but with less severe SE drops and smoother transitions, indicating greater stability. This stable performance extends into the high-frequency range as well

Stainless steel performs slightly worse than carbon fiber below 3 GHz but lies between iron and other materials across most of the spectrum.

This performance difference is likely due to the presence of magnetic permeability in iron and stainless steel, especially the high permeability of iron, which enhances its ability to absorb the magnetic component of incident waves. This effect suppresses resonance and improves SE stability.

In conclusion, materials with higher magnetic permeability can effectively mitigate SE degradation caused by structural resonance and improve the system's resistance to electromagnetic disturbances. This may explain the relatively stable shielding behavior observed in iron.

4.6. Effect of Aperture Shape

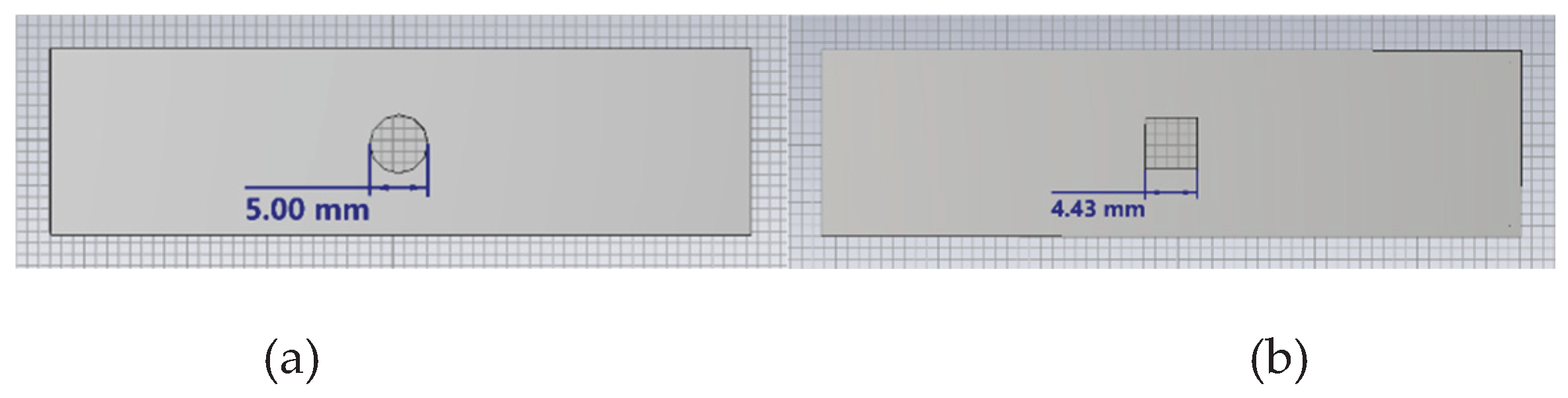

The shape of an aperture directly influences the local electric field distribution and current concentration characteristics, thereby affecting electromagnetic wave coupling and overall shielding performance. In this section, the shielding effectiveness of circular and rectangular openings is compared under the condition of equal effective aperture area.

Figure 19.

Illustration of different aperture shapes:(a) Circular opening; (b) Rectangular opening.

Figure 19.

Illustration of different aperture shapes:(a) Circular opening; (b) Rectangular opening.

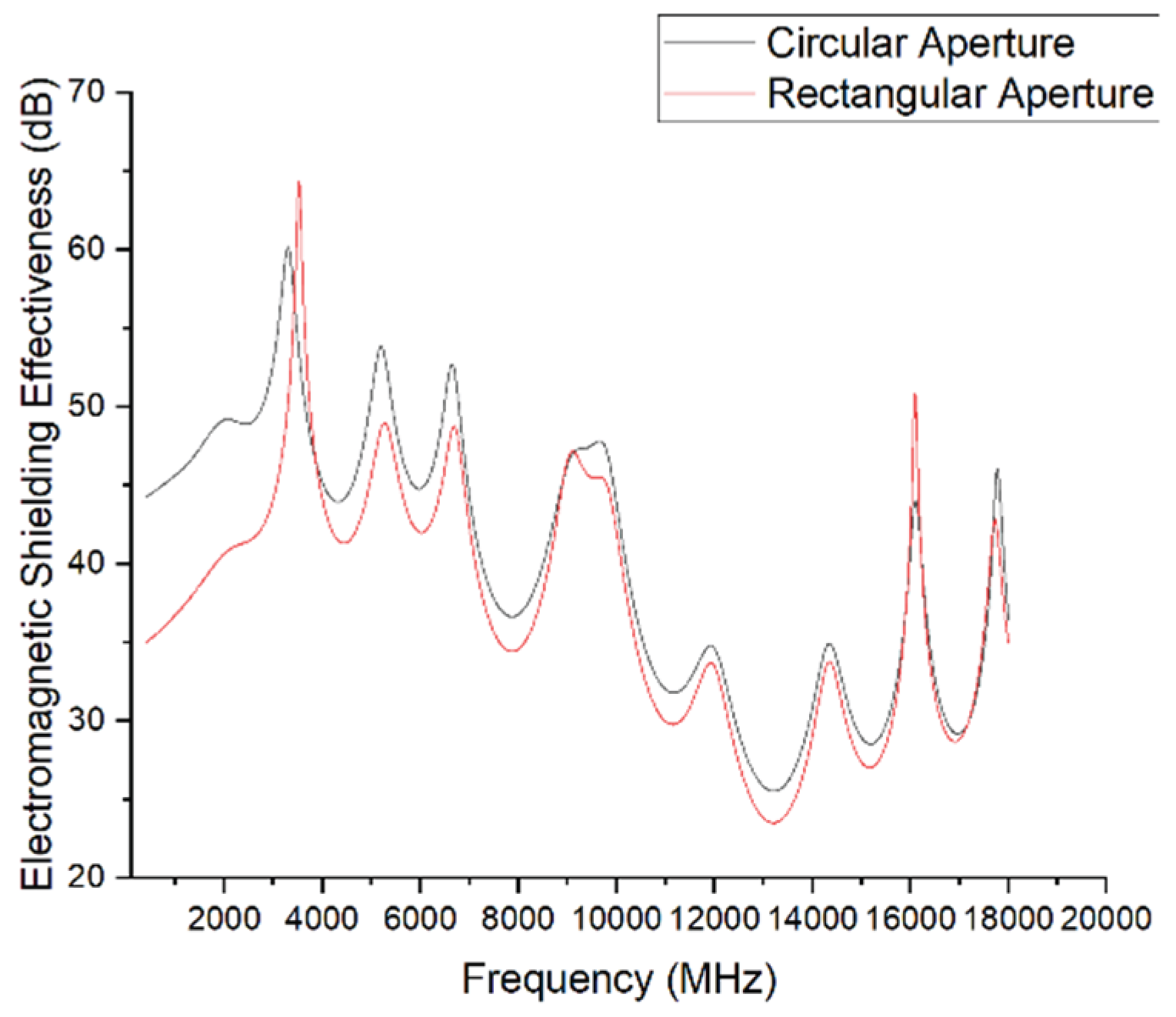

Figure 20.

Simulation results for different aperture shapes.

Figure 20.

Simulation results for different aperture shapes.

The simulation results show that even with identical aperture areas, the shape of the aperture has a significant effect on shielding effectiveness. The circular opening (diameter = 5 mm) demonstrates superior shielding performance across the entire frequency range compared to the rectangular opening (square, side length = 4.43 mm). This difference is particularly pronounced in the low-frequency range (2–6 GHz), where the maximum SE difference exceeds 10 dB.

As the frequency increases, the performance difference between the two shapes gradually decreases, and in the high-frequency range (16–20 GHz), the results tend to converge.

The underlying reason is that circular structures produce weaker edge field enhancement, and the diffraction path of electromagnetic waves is more evenly distributed, which helps mitigate gap coupling effects and improves shielding performance. In contrast, rectangular apertures feature sharp corners where electric fields are more likely to concentrate, leading to stronger coupling and resonance, and thus lower SE.

This demonstrates that even with identical aperture areas, the geometric edge characteristics and symmetry significantly affect the enclosure’s electromagnetic shielding behavior. Therefore, in structural design, circular or rounded aperture shapes should be prioritized to enhance electromagnetic compatibility.

4.7. Effect of Aperture Size

perture size is a critical factor that determines the local failure risk of a shielding structure. This section systematically analyzes the impact of aperture size on shielding performance and evaluates how it affects SE trends and failure mechanisms, particularly in resonance frequency bands.

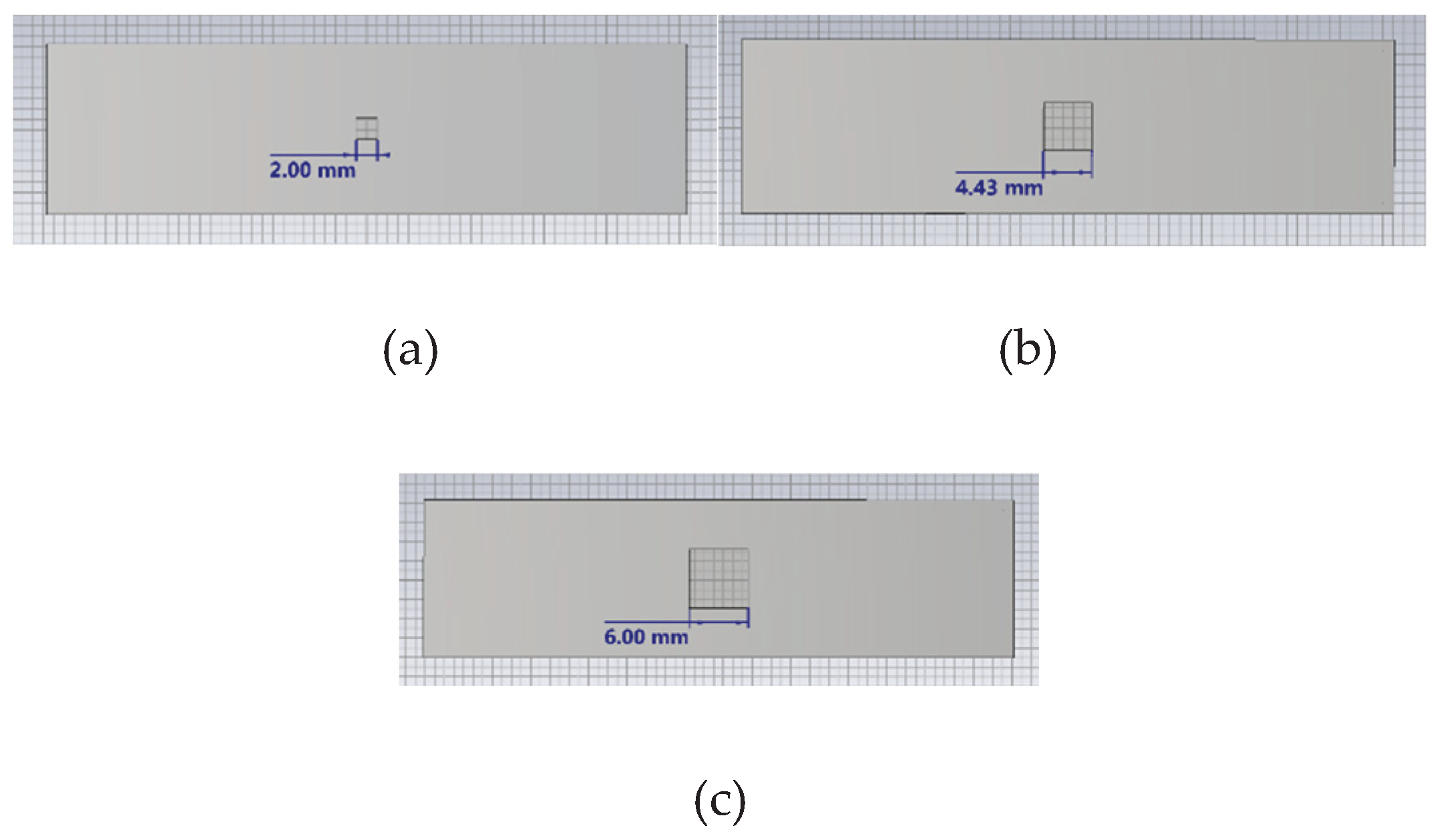

Figure 21.

Illustration of different aperture sizes:(a) Rectangular opening, side length = 2 mm; (b) Rectangular opening, side length = 4.43 mm; (c) Rectangular opening, side length = 6 mm.

Figure 21.

Illustration of different aperture sizes:(a) Rectangular opening, side length = 2 mm; (b) Rectangular opening, side length = 4.43 mm; (c) Rectangular opening, side length = 6 mm.

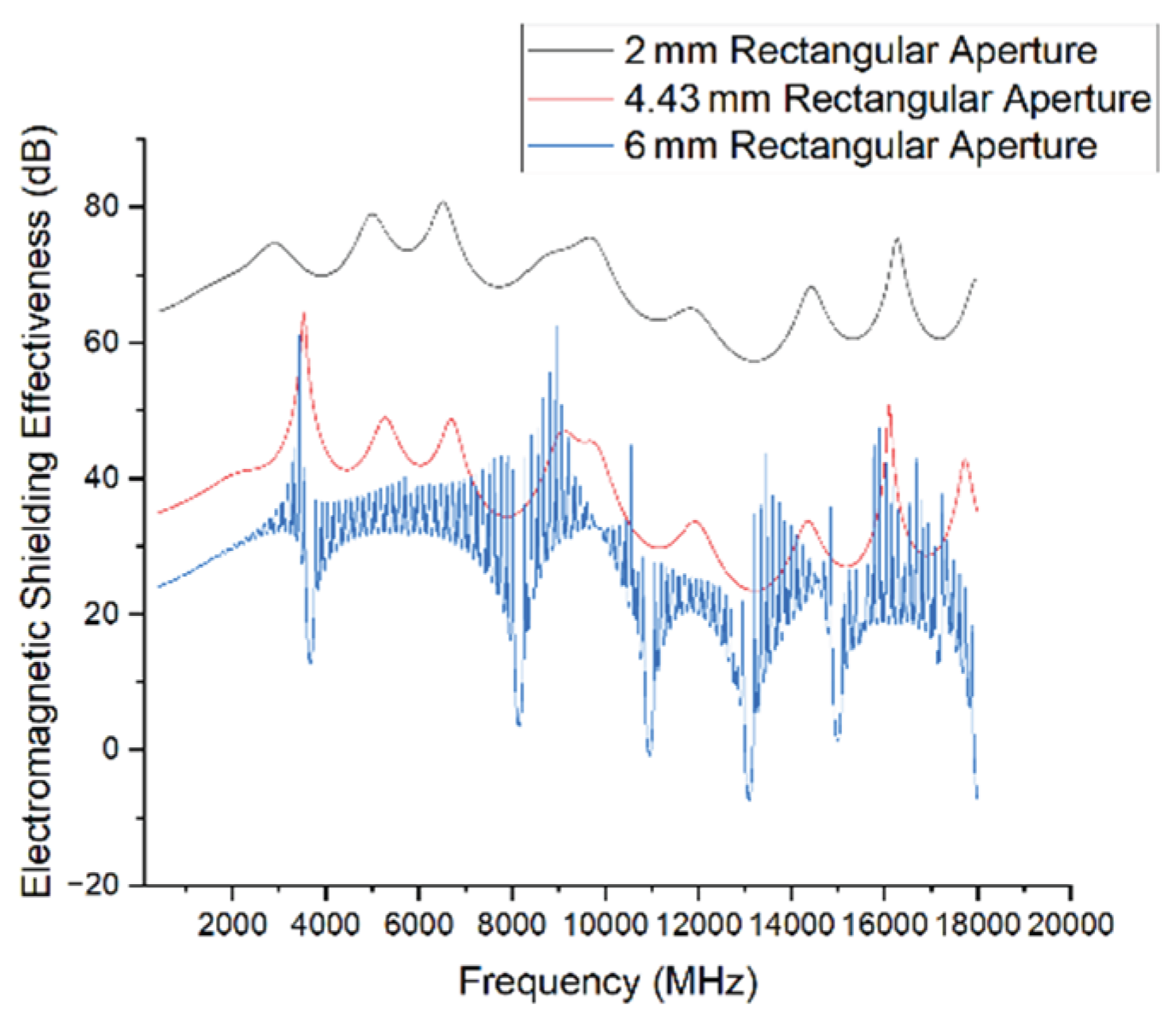

Figure 22.

Simulation results for different aperture sizes

Figure 22.

Simulation results for different aperture sizes

The simulation results clearly demonstrate that the size of the rectangular aperture has a significant influence on shielding effectiveness. As the side length increases, the shielding capability deteriorates notably.

The 2 mm aperture exhibits excellent shielding performance across the entire frequency range, with SE consistently maintained between 60 and 75 dB, indicating strong electromagnetic protection.

When the side length increases to 4.43 mm, the overall SE drops by approximately 20–30 dB, with localized dips observed at several frequencies.

Further increasing the side length to 6 mm results in severe SE fluctuations, with the minimum dropping to around –10 dB and multiple strong resonances appearing.

This sharp degradation in performance is closely related to enhanced coupling effects caused by larger apertures. Larger openings are more susceptible to resonance excitation, allowing electromagnetic waves to penetrate more efficiently and thereby severely compromising the shielding integrity of the enclosure.

Therefore, in equipment structural design, large apertures should be avoided, especially in systems sensitive to mid- and high-frequency interference. Controlling aperture size is a key factor in maintaining stable shielding performance.

4.8. Effect of Aperture Quantity

When the total aperture area remains constant, the number of apertures and their spatial distribution affect the formation of electromagnetic leakage paths in different ways. This section compares concentrated versus distributed multi-aperture configurations to assess their influence on shielding effectiveness across a range of frequencies.

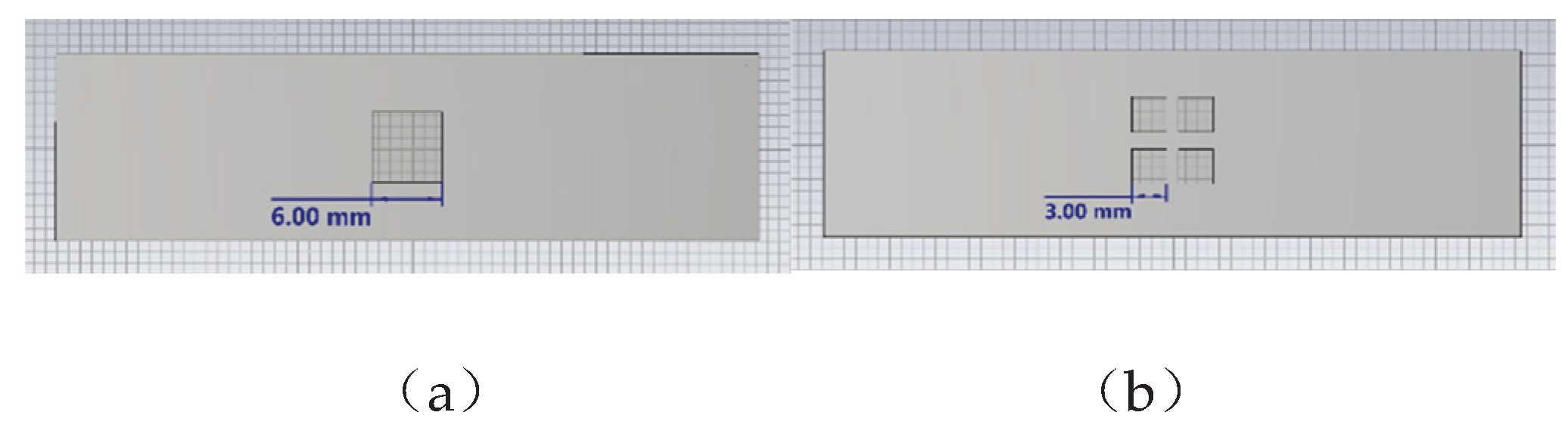

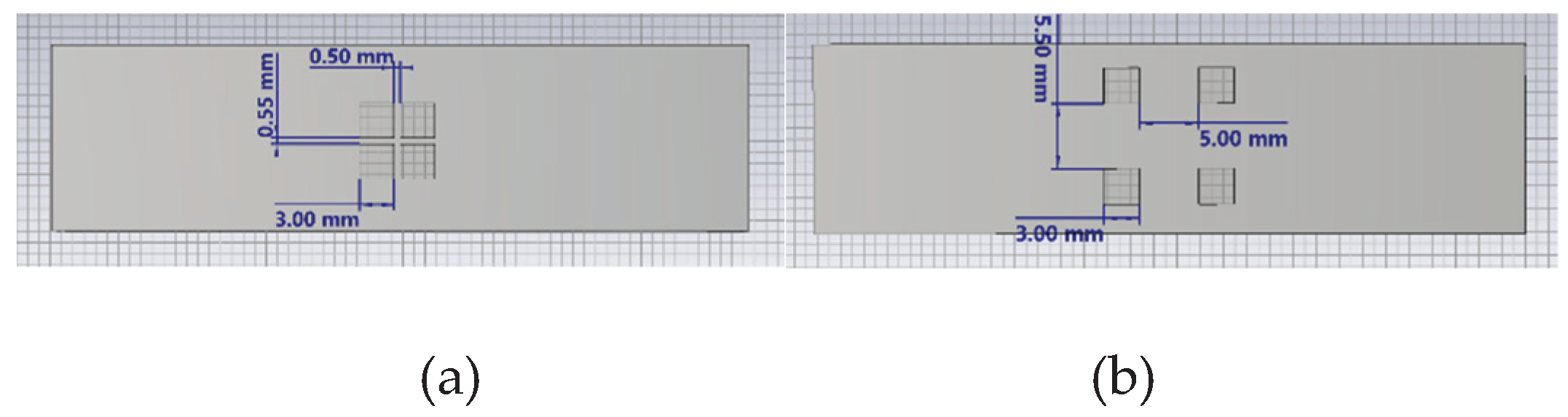

Figure 23.

Illustration of different aperture quantity configurations:(a) One rectangular aperture with side length = 6 mm; (b) Four rectangular apertures with side length = 3 mm each.

Figure 23.

Illustration of different aperture quantity configurations:(a) One rectangular aperture with side length = 6 mm; (b) Four rectangular apertures with side length = 3 mm each.

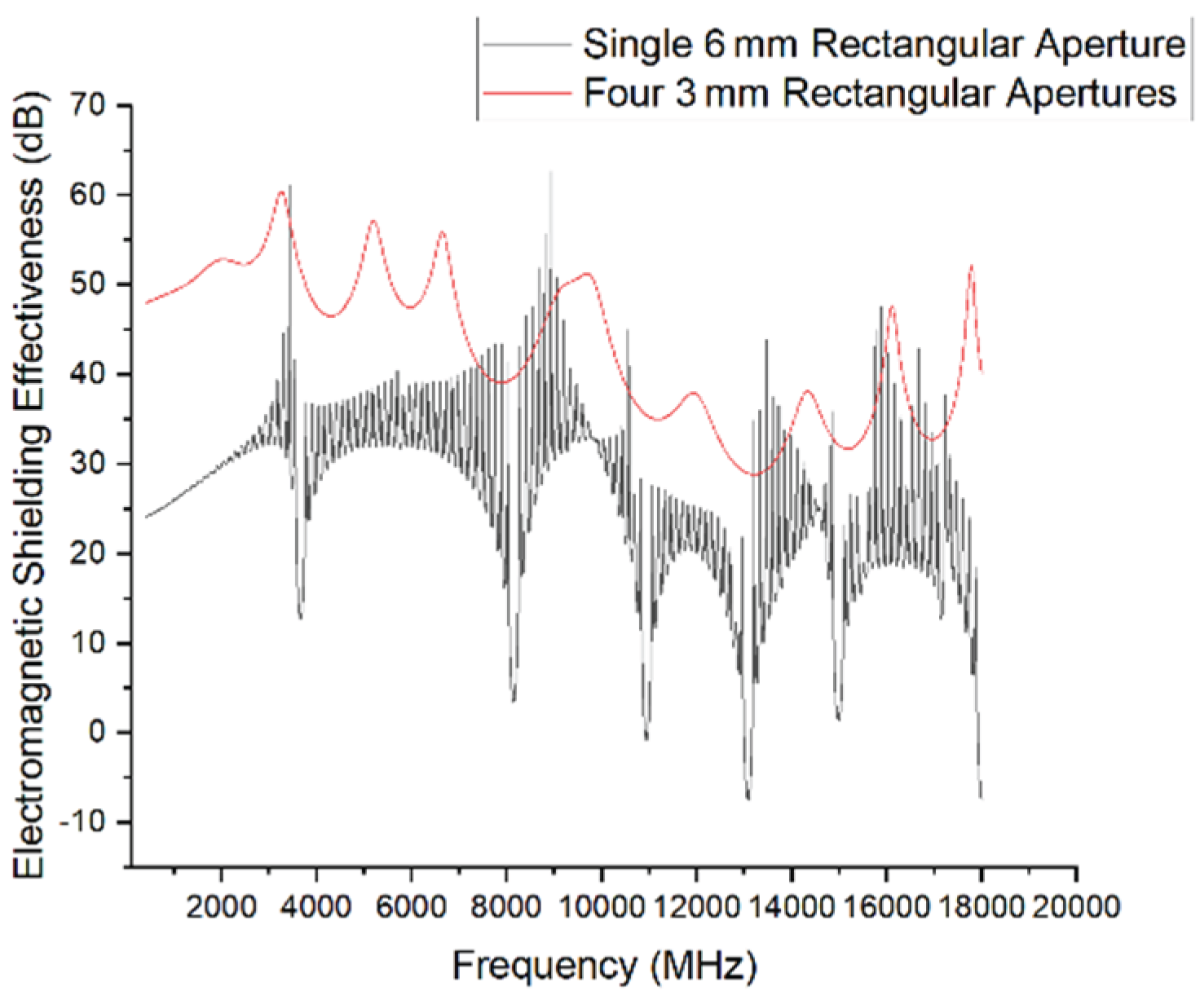

Figure 24.

Simulation results for different aperture quantities.

Figure 24.

Simulation results for different aperture quantities.

The simulation results clearly demonstrate that even under the same total aperture area, aperture quantity has a significant impact on shielding effectiveness. Compared to a single large rectangular opening (6 mm side length), the configuration with four smaller apertures (each 3 mm in side length) exhibits better overall shielding performance across the entire frequency range.

The single large aperture model shows severe resonances at multiple frequencies, where SE values drop dramatically, with minimum levels approaching –10 dB, indicating a substantial loss of shielding capability. In contrast, the four-aperture configuration maintains a higher and more stable SE, with no clear signs of resonant failure in the spectrum.

This result indicates that higher aperture concentration increases the likelihood of strong coupling effects and resonance, which in turn leads to enhanced electromagnetic leakage. In contrast, distributing the same total aperture area helps reduce the intensity of local resonances and improves the enclosure’s overall ability to suppress incident electromagnetic waves.

4.9. Effect of Aperture Spacing

This section investigates the impact of aperture spacing on shielding effectiveness while keeping the number, shape, and total area of the apertures constant.

Figure 25.

Illustration of different aperture spacing: (a) Closely spaced apertures; (b) Widely spaced apertures.

Figure 25.

Illustration of different aperture spacing: (a) Closely spaced apertures; (b) Widely spaced apertures.

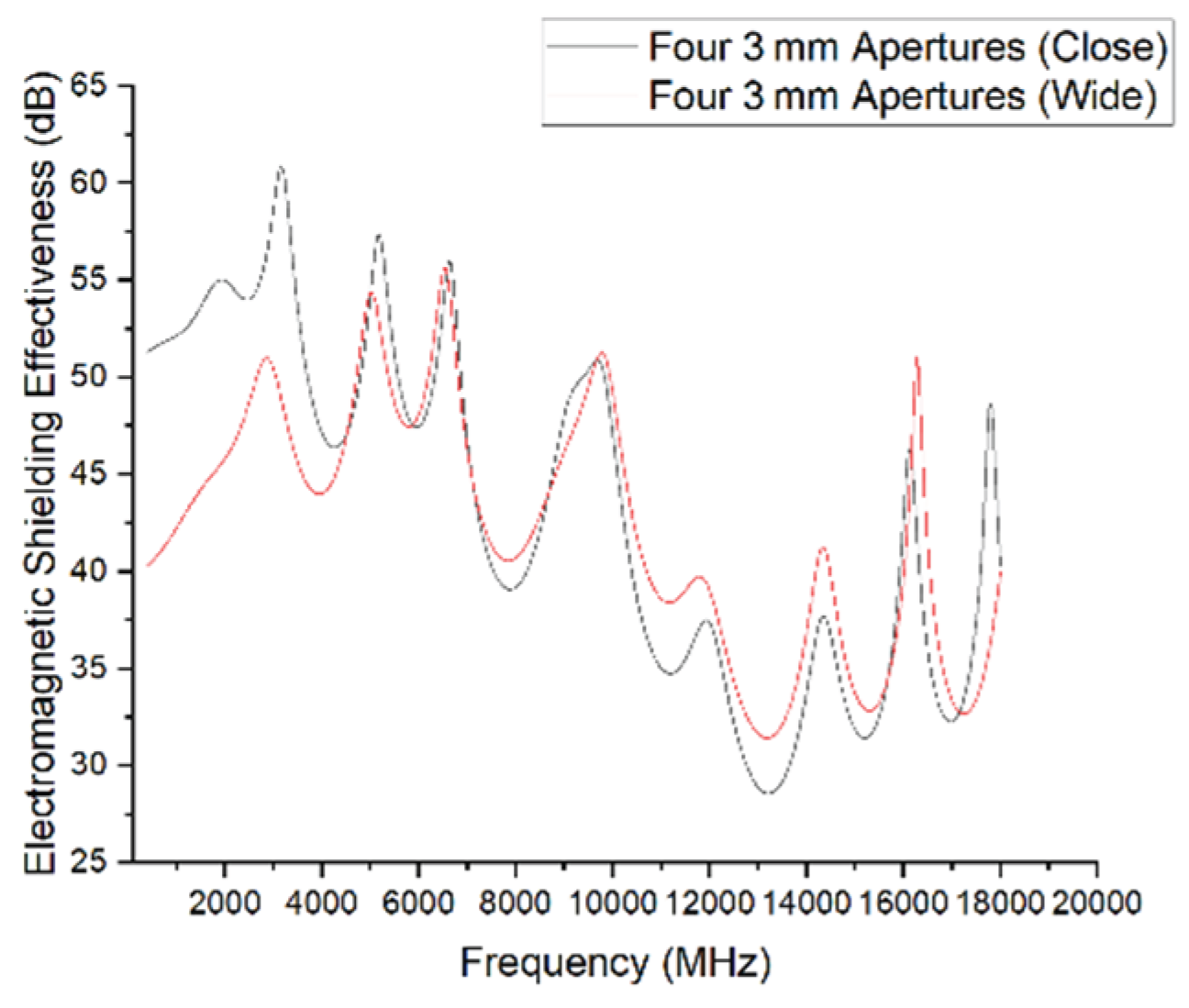

Figure 26.

Simulation results for different aperture spacing.

Figure 26.

Simulation results for different aperture spacing.

The simulation results indicate that aperture spacing significantly influences shielding performance, with varying effects across different frequency bands:

In the low-frequency range (below 8 GHz), configurations with closely spaced apertures exhibit better shielding effectiveness than those with wider spacing. The maximum SE difference exceeds 10 dB.

In the mid- to high-frequency range (8–16 GHz), the configuration with wider aperture spacing performs better at several frequency points, suggesting improved suppression of localized resonances.

At very high frequencies (e.g., around 16 GHz), the shielding effectiveness of both configurations begins to converge, and the influence of spacing becomes less pronounced.

These findings suggest that closer spacing may suppress low-frequency leakage, possibly by limiting long-wavelength resonance paths. Conversely, increased spacing helps reduce mutual coupling between apertures at higher frequencies, thereby enhancing performance in the mid-to-high frequency bands. However, at very high frequencies, the wavelength is short enough that spacing effects diminish.

5. Experimental Validation in a Microwave Anechoic Chamber

To verify whether the simulation results align with real-world performance and to evaluate the GNSS receiver's immunity under actual HIRF conditions, a radiated immunity test was conducted in a microwave anechoic chamber.

5.1. Experimental Procedure

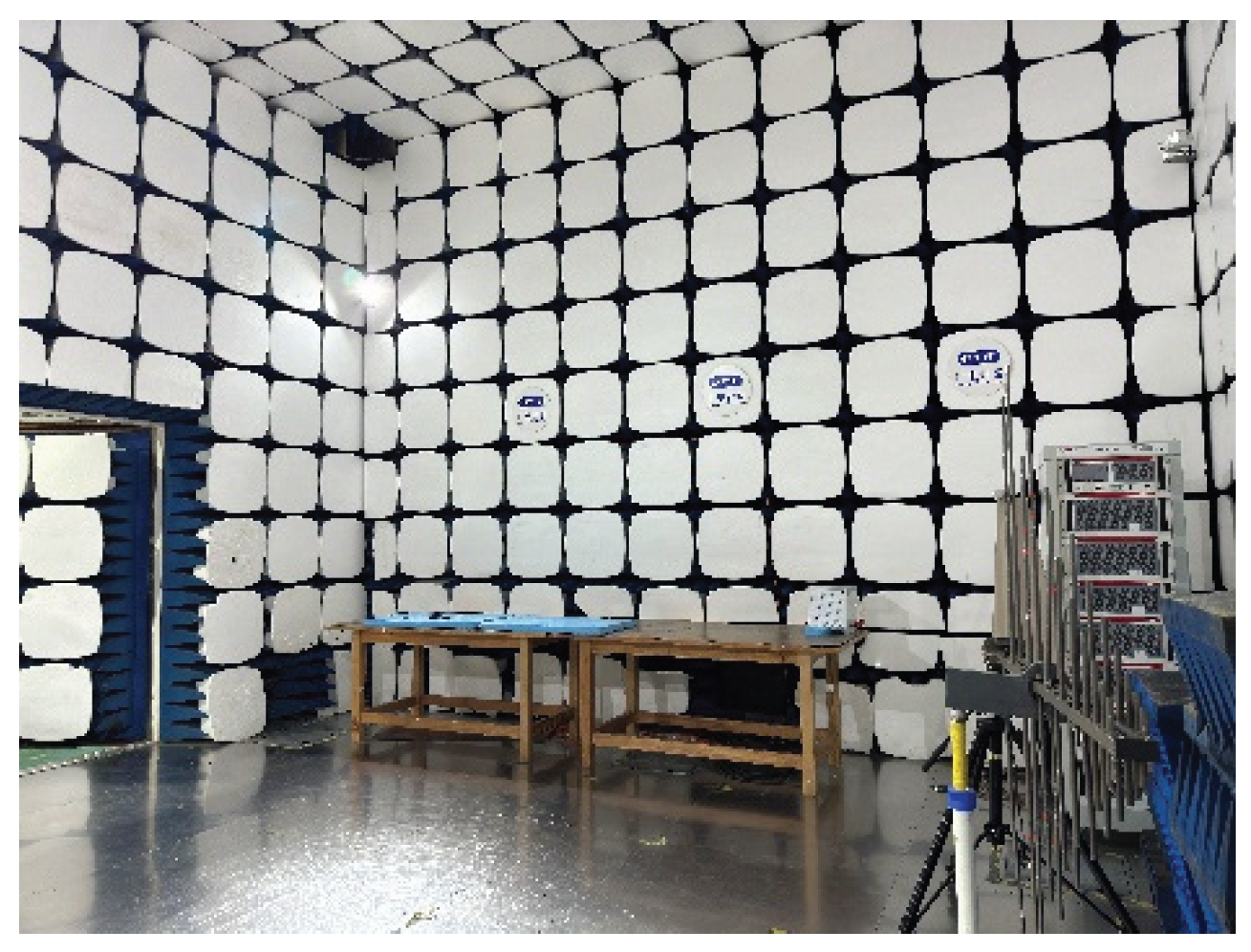

In radiated immunity testing, an anechoic chamber provides a stable and controlled electromagnetic environment for airborne electronic equipment, simulating the electromagnetic exposure conditions experienced by aircraft in HIRF scenarios. The chamber used in this study measures 10 m × 8 m × 6.4 m.

Figure 27.

Test environment for radiated immunity in the anechoic chamber.

Figure 27.

Test environment for radiated immunity in the anechoic chamber.

In the field of electromagnetic compatibility (EMC), immunity testing is commonly used to assess the behavior of electronic equipment under the influence of external electromagnetic fields. Immunity refers to the ability of a device to maintain normal operation in the presence of electromagnetic interference (EMI). In this study, a continuous wave (CW) signal was used to conduct the radiated immunity test, assessing the GNSS receiver's stability under a steady-state HIRF environment.The specific experimental steps are as follows:

Before the test, the GNSS receiver was confirmed to operate normally in a non-interference environment.

- 2.

Equipment setup.

The GNSS receiver was mounted on a test fixture inside the chamber and connected to a computer-based monitoring system to ensure stable data acquisition.

- 3.

Field strength definition and generation.

To evaluate the receiver's performance under high HIRF levels, the test adopted the field strength standards listed below, aiming to replicate the challenges encountered by avionics in extreme electromagnetic environments.

Table 2.

Radiated immunity test field strength

Table 2.

Radiated immunity test field strength

| Test Frequency Range (GHz) |

CW Field Strength (V/m) |

| 0.1-0.2 |

100 |

| 0.2-0.4 |

100 |

| 0.4-0.7 |

50 |

| 0.7-1 |

100 |

| 1-2 |

200 |

| 2-4 |

200 |

| 4-6 |

200 |

| 6-8 |

200 |

| 8-12 |

300 |

| 12-18 |

200 |

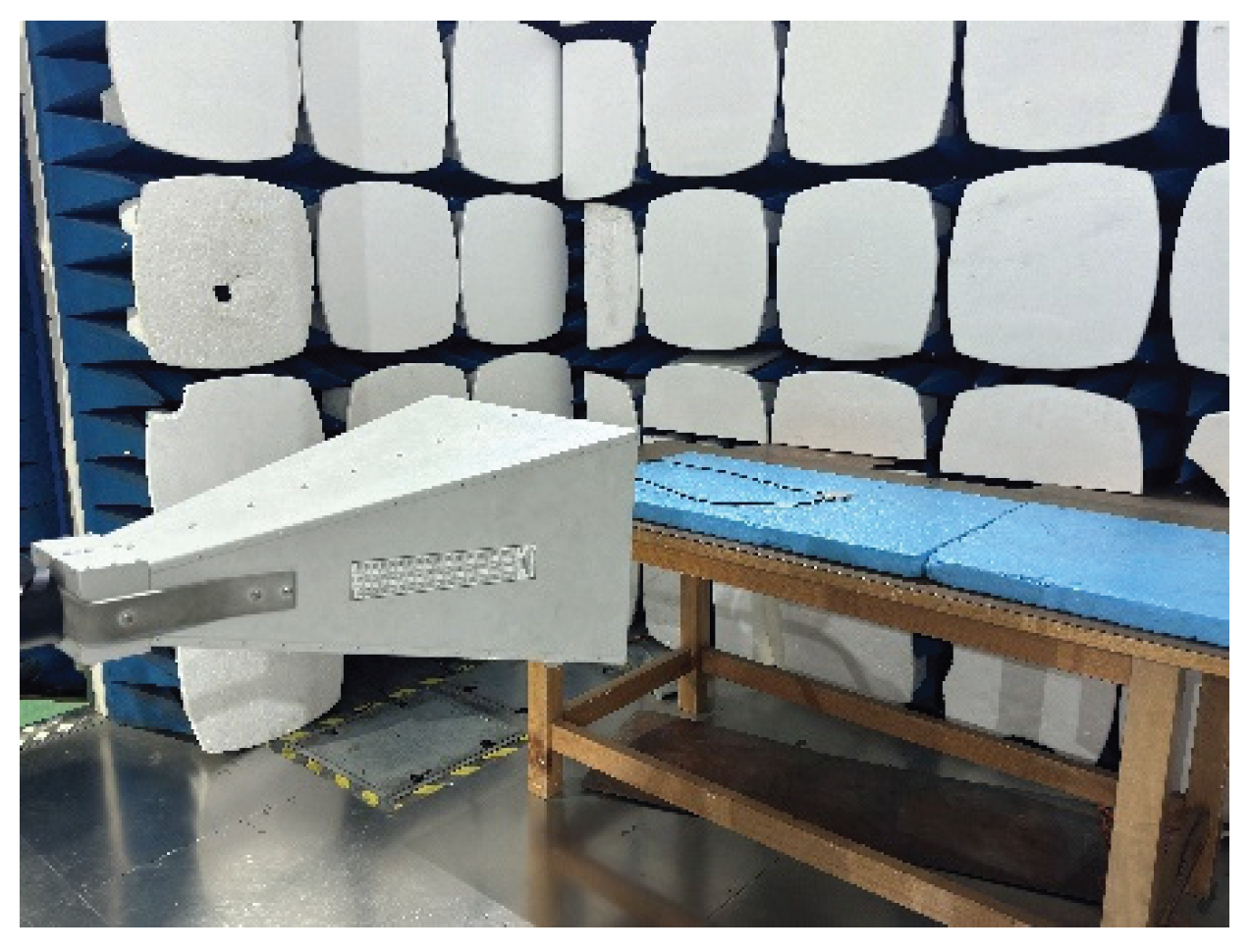

Figure 28.

Antenna illumination setup.

Figure 28.

Antenna illumination setup.

A sweep test was performed across each decade band with 100 frequency points, during which the receiver’s operating status was continuously monitored to evaluate its immunity under increasing field strengths.

- 4.

GNSS receiver status monitoring.

During the test, the GNSS receiver’s status indicators were observed using a camera system (see

Figure 29) to detect any shutdown or reboot events. Simultaneously, the receiver's solution parameters—including latitude, longitude, altitude, speed, and DOP—were monitored via computer software to detect signal loss or degraded accuracy.

Figure 29.

Camera monitoring interface.

Figure 29.

Camera monitoring interface.

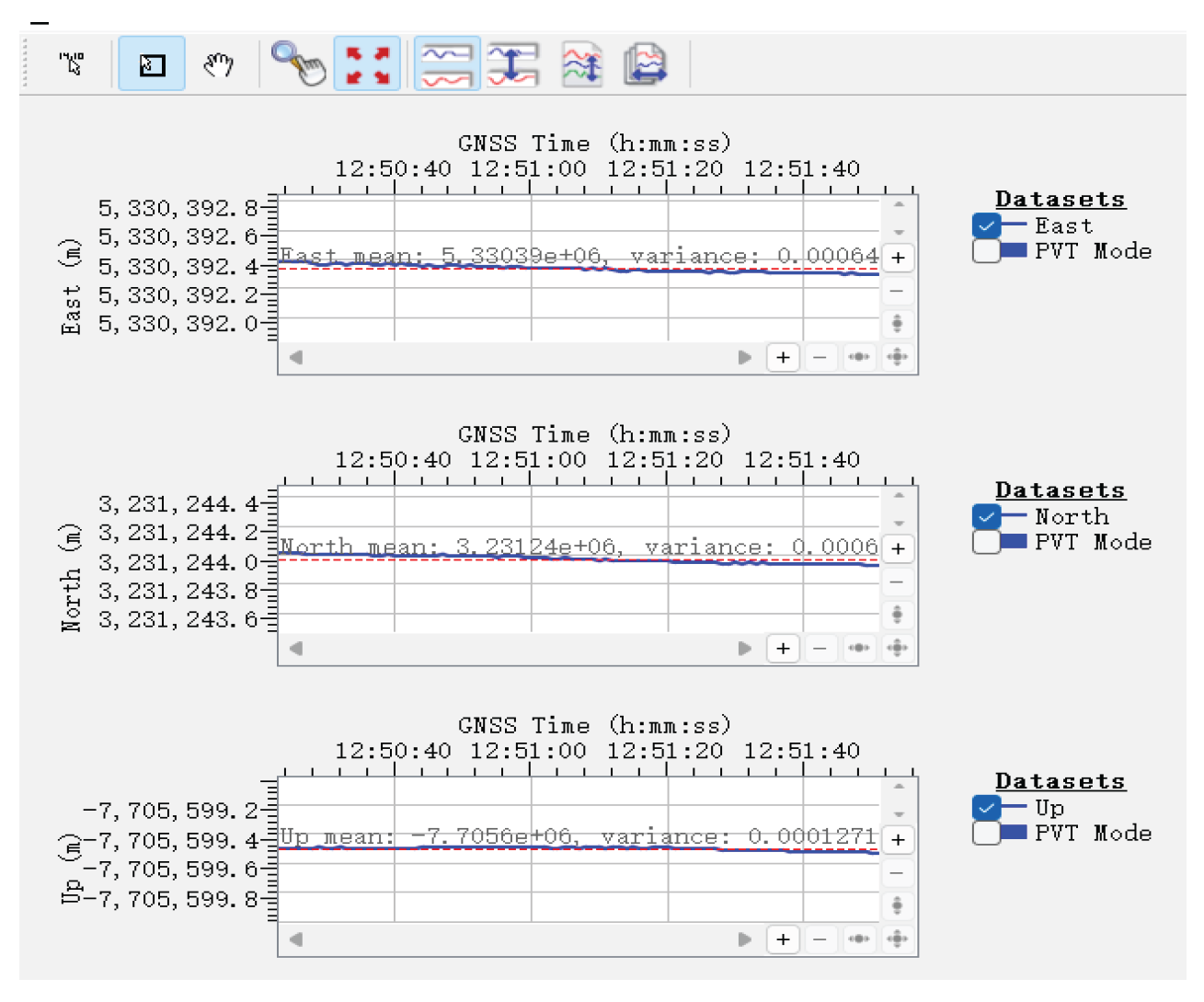

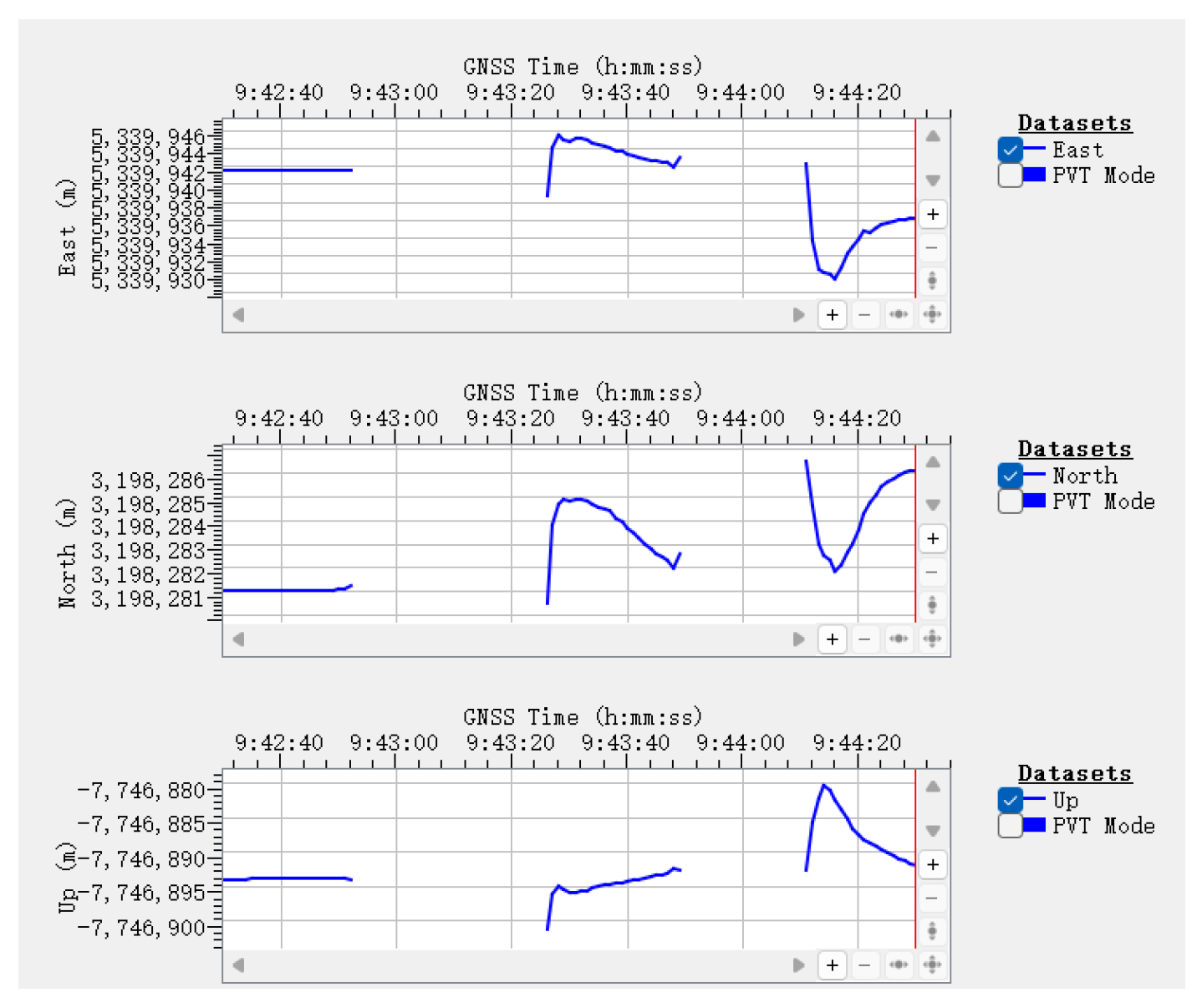

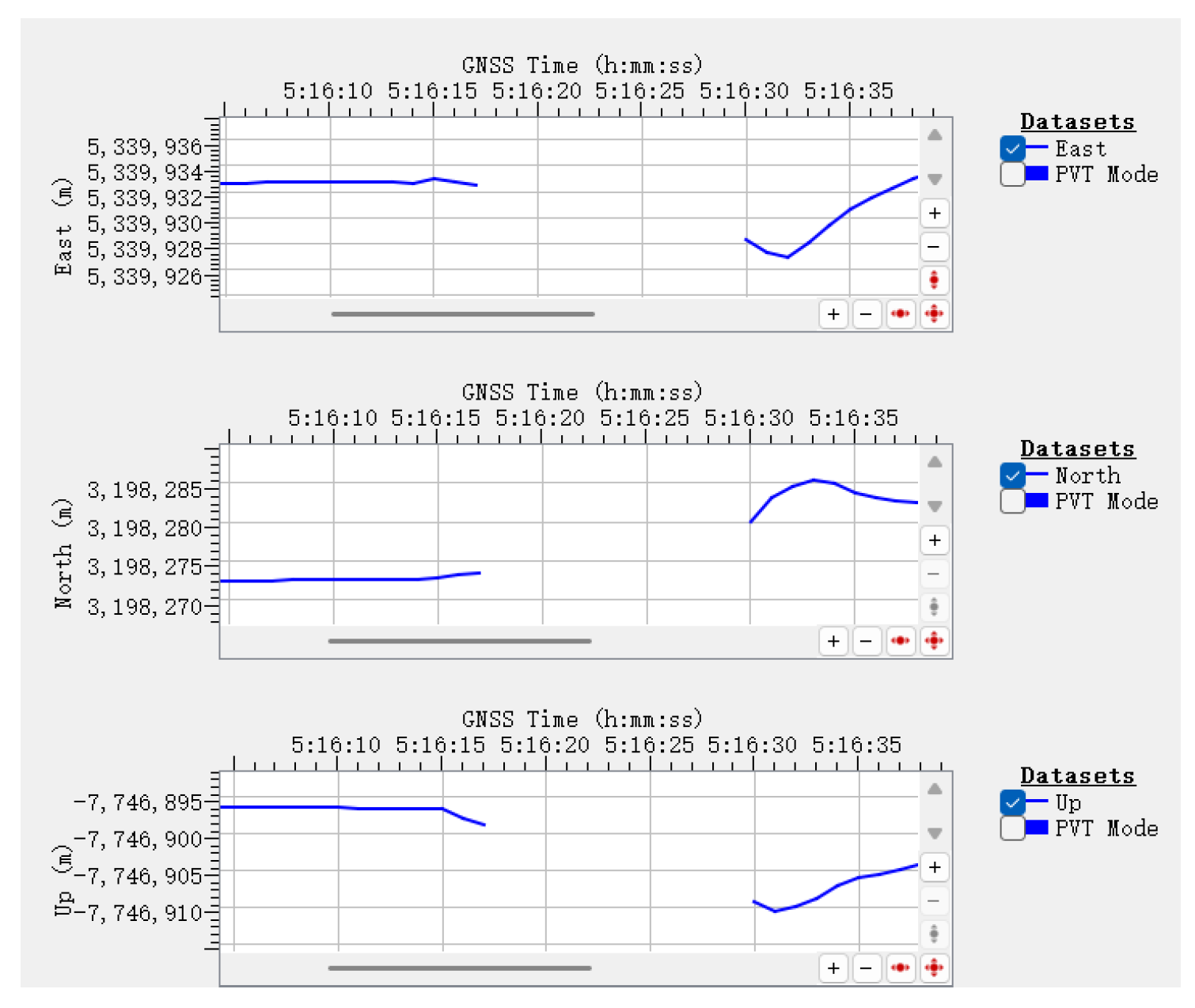

In the monitoring interface, the relative position is expressed using the East-North-Up (ENU) coordinate system, which represents the receiver’s deviation from a reference point in three orthogonal directions.

Figure 30.

ENU position monitoring under normal conditions.

Figure 30.

ENU position monitoring under normal conditions.

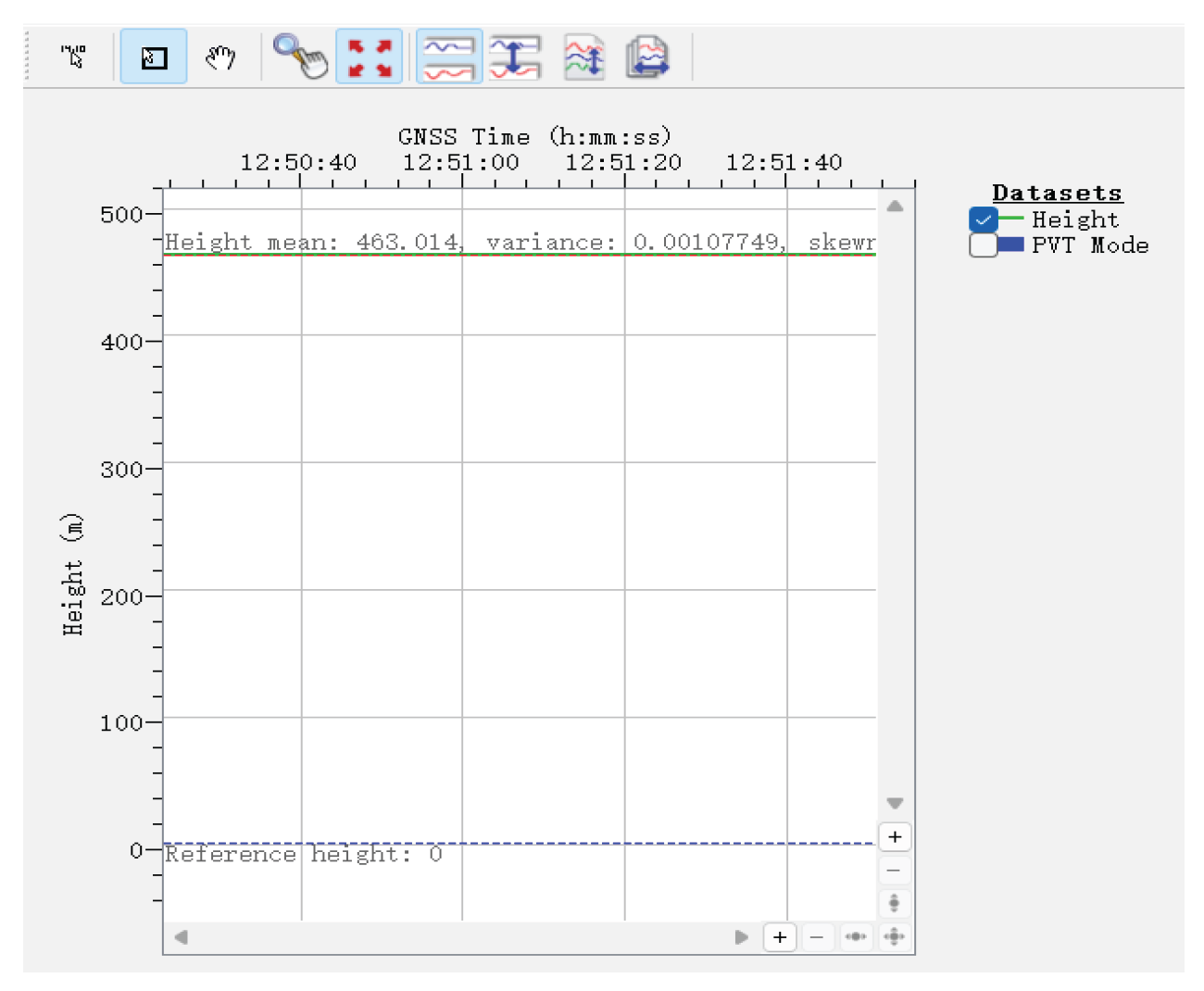

Ellipsoidal height refers to the altitude above the WGS-84 reference ellipsoid, a key parameter in GNSS positioning used for navigation and mapping.

Figure 31.

Ellipsoidal height under normal conditions.

Figure 31.

Ellipsoidal height under normal conditions.

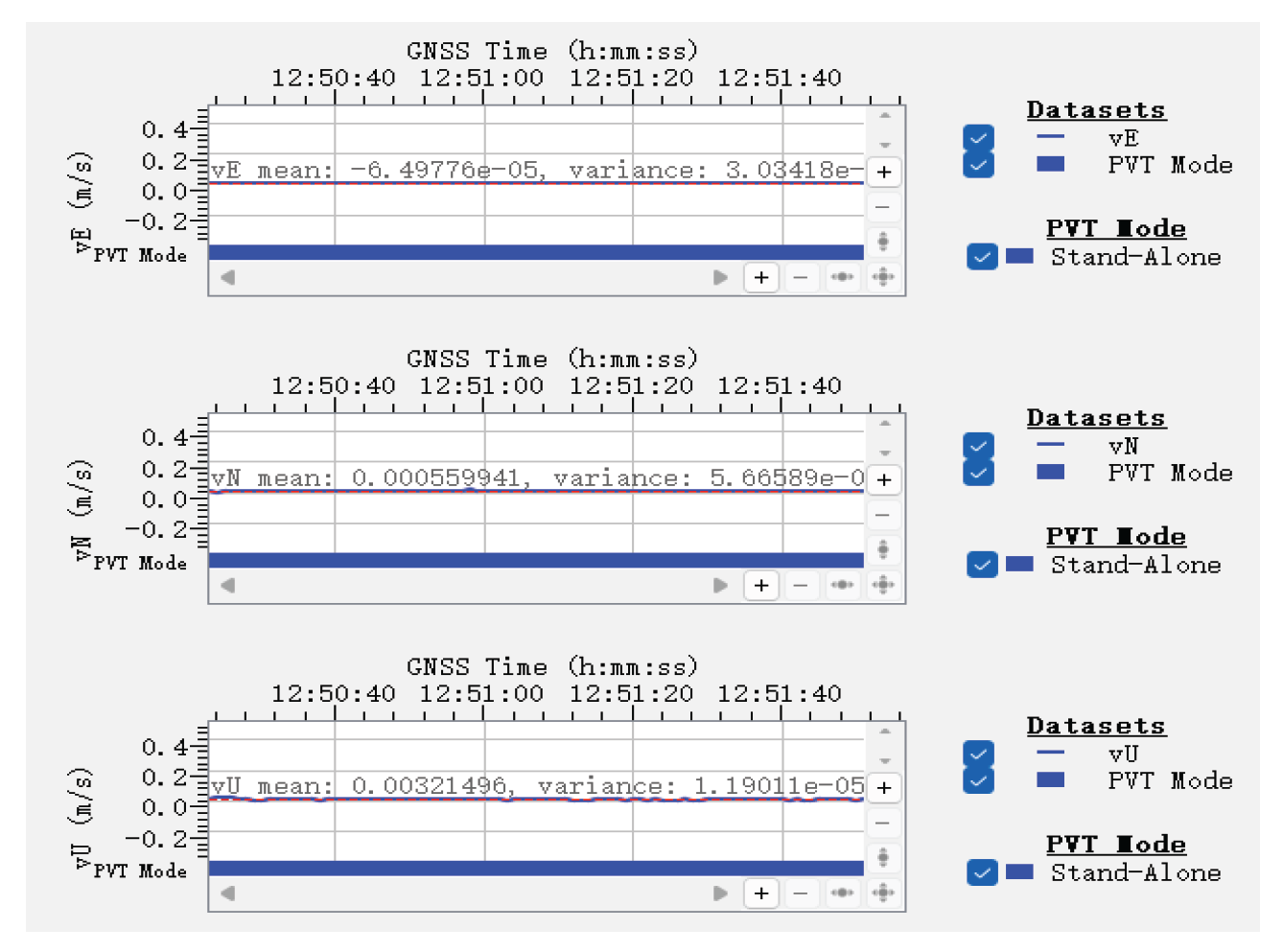

GNSS velocity is calculated in terms of velocity components along the ENU directions, represented by ∇E (eastward), ∇N (northward), and ∇U (upward or zenith).

Figure 32.

Velocity monitoring under normal conditions.

Figure 32.

Velocity monitoring under normal conditions.

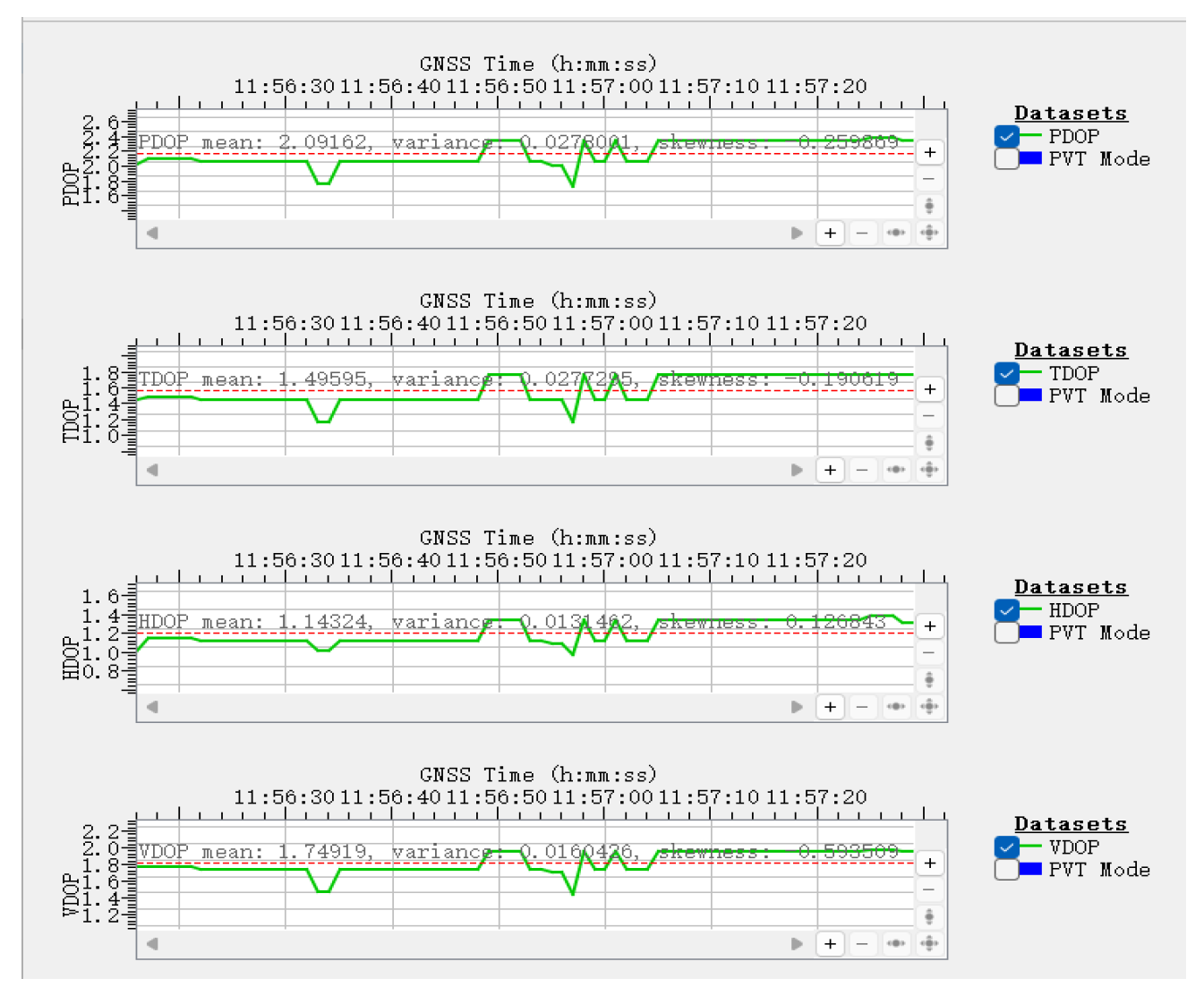

DOP (Dilution of Precision) is a critical metric for GNSS accuracy, reflecting the effect of satellite geometry on positioning precision. Key DOP indicators include:PDOP (3D positioning precision),TDOP (Timing precision),HDOP ( Horizontal precision), VDOP (Vertical precision).

Figure 33.

DOP monitoring under normal conditions.

Figure 33.

DOP monitoring under normal conditions.

- 5.

Data logging and analysis

During testing, the GNSS receiver’s status was recorded in real time for each frequency point. Three failure modes were specifically monitored: Device shutdown or reboot, Signal loss, Severe degradation in positioning accuracy.

After testing, all data were statistically analyzed to assess the GNSS receiver’s immunity performance under HIRF conditions.

5.2. Analysis of Anechoic Chamber Test Results

To evaluate the GNSS receiver’s immunity under HIRF conditions, this section analyzes and summarizes the monitoring data obtained across all test frequency bands.

During the test, no shutdown or reboot events were observed. However, signal loss occurred at several specific frequency points, indicating that the receiver was affected by the high-intensity electromagnetic environment. These results demonstrate a need to further improve the receiver’s HIRF protection capability.

As shown in

Figure 34, at 13.183 GHz with horizontal polarization, the GNSS receiver experienced repeatable signal loss. Once the electromagnetic field was applied, the receiver lost its navigation signal. The signal returned after the field was removed but disappeared again upon reapplying the same field strength. Although the signal eventually recovered, data discontinuities and degraded positioning accuracy were observed.

As illustrated in

Figure 35, at 14.125 GHz with vertical polarization, a similar signal loss event occurred. After the electromagnetic field was removed, the signal resumed, but not without error—the recovered data deviated from the stable state, suggesting that the GNSS receiver temporarily failed and suffered drift errors. Additionally, the navigation data showed a gradual return to stability over time, implying that HIRF interference can temporarily reduce the receiver's positioning accuracy, and the recovery process involves a noticeable latency.

Signal loss events were also recorded at other frequencies. The summary of observed failures is presented in

Table 3.

As shown in

Table 3, most signal loss events occurred in the 12–18 GHz range, where the receiver's susceptibility to electromagnetic interference was notably higher. These findings are consistent with the simulation results, particularly the predicted resonance frequencies, confirming the validity of the simulation model. Moreover, the data suggest that the receiver's immunity performance at high frequencies remains insufficient, indicating the need for further enhancements in HIRF shielding and design robustness.

6. Optimization Recommendations

To enhance the electromagnetic shielding effectiveness (SE) of airborne equipment enclosures under High-Intensity Radiated Fields (HIRF), this chapter presents targeted design recommendations based on the simulation results and anechoic chamber tests. The focus is on high-frequency shielding degradation, with strategies proposed in terms of frequency response behavior, material selection, and structural design.

6.1. Frequency Response Characteristics and Resonance Suppression

In the 3–10 GHz range, the enclosure is particularly prone to localized resonances, where the shielding effectiveness drops sharply. This typically occurs when the characteristic dimensions of the structure are comparable to the wavelength of the incident wave. To mitigate resonance-induced shielding failures, the following measures are recommended:

Geometrical Adjustment: Modify the overall dimensions of the enclosure and openings to shift the structure’s natural resonant frequencies away from critical EMI bands.

Absorptive Material Application: Apply ferrite coatings, conductive rubber, or other lossy materials near openings or regions with high surface current concentrations to suppress resonance.

Gap Optimization: Improve electrical continuity at seams and joints using conductive gaskets, EMI shielding fabric, or seam-sealing techniques to prevent resonance-induced coupling.

Table 4 summarizes the proposed mitigation strategies and their target frequency ranges.

6.2. Optimization of Aperture Design

The number, shape, size, and distribution of apertures are among the most critical factors affecting electromagnetic shielding performance. The following design recommendations are proposed to mitigate aperture-induced degradation, particularly in the mid-to-high frequency range:

Aperture Size Control: Larger aperture dimensions significantly degrade shielding effectiveness, especially at higher frequencies. It is essential to strictly limit the maximum aperture size, particularly for functional openings such as ventilation holes and connector interfaces. To maintain both functionality and shielding, EMC design solutions—such as honeycomb waveguide windows or filtered connectors—are recommended.

Aperture Shape Optimization: Prefer small-sized, circular, or rounded-corner apertures to avoid sharp-edge-induced electric field enhancement and current concentration, which increase the likelihood of resonance. Rounded geometries help minimize local field distortion and improve broadband SE stability.

Aperture Quantity and Distribution Strategy: When openings are unavoidable, adopt a multi-aperture, small-size, and non-periodic distribution strategy. For devices requiring large-scale ventilation, replacing a single large opening with multiple small, dispersed apertures is more effective in avoiding strong coupling and resonant failures. Additionally, avoid uniform spacing between apertures, as periodic distributions may induce structural resonance, forming localized weak points in the shielding performance.

6.3. Material Selection and Electromagnetic Property Matching

Materials with high electrical conductivity—such as copper and aluminum—generally offer strong shielding effectiveness (SE), but tend to exhibit severe performance fluctuations near resonance frequencies. In contrast, materials with high magnetic permeability, such as iron, demonstrate better resilience against resonance effects, providing more stable shielding performance across the spectrum.

Therefore, it is recommended to locally or globally incorporate high-permeability materials or magnetic composites into the enclosure structure—particularly at critical locations such as seams, apertures, or areas prone to current concentration—to suppress resonance amplification and improve shielding stability under high-intensity electromagnetic environments.

6.4. Multi-Polarization and Multi-Directional Electromagnetic Protection Design

Simulation results demonstrate that shielding effectiveness (SE) varies significantly with different polarization modes, incident angles, and incident surfaces. In practical HIRF environments, the polarization, propagation direction, and incidence location of electromagnetic waves are highly random. Therefore, optimizing the structure under a single direction or specific polarization condition cannot ensure comprehensive protection. Structural design must provide robust omnidirectional shielding capability.

Fundamentally, the anisotropy of shielding performance stems from the non-uniform distribution of structural features, especially the number, shape, and orientation of openings. The following strategies are recommended to enhance the overall shielding stability:

Structural Layout Optimization: Adjust the position of key apertures, seams, and connections to avoid strong coupling with specific polarization directions. This reduces polarization-sensitive weak points and enhances generalized SE performance.

Enhanced Multi-Angle Protection: Simulations reveal that variation in incident angle significantly affects SE in the mid-frequency band. Oblique incidence weakens the parallel electric field component, reducing aperture and seam coupling. Thus, the design should consider shielding uniformity under multiple incidence angles, rather than optimizing performance for only a single direction.

Reinforcement of Critical Aperture Surfaces: For areas with concentrated apertures, apply composite shielding techniques—such as EMI conductive gaskets, elastic grounding connections, and absorptive coatings. Incorporating waveguide-beyond-cutoff or notch structures within the aperture can block high-frequency leakage paths and suppress resonance effects. Moreover, aperture distribution should be spatially uniform to ensure balanced shielding across all incident surfaces, preventing "weakest surface" vulnerabilities.

6.5. Shielding Effectiveness Optimization in High-Frequency Bands

In the high-frequency range of 10–18 GHz, shielding effectiveness (SE) tends to decrease significantly, and airborne electronic systems become more prone to failure. At these frequencies, surface current concentration intensifies, and coupling paths become more complex, though gaps and small apertures remain the dominant leakage routes. The following strategies are recommended to enhance SE performance in the high-frequency domain:

Optimized Material Selection: It is advisable to use composite materials that exhibit both high electrical conductivity and high magnetic permeability, or to apply ferromagnetic metals at critical locations. This dual-parameter approach enhances the suppression of both electric and magnetic field components, effectively reducing resonance sensitivity and improving SE stability at high frequencies.

Integration of High-Frequency Notch Structures: Introduce frequency-selective structures (FSS)—such as embedded metallic grids or surface capacitive patches—inside the enclosure or at aperture sites. These microstructures are designed to produce frequency-selective attenuation, targeting high-frequency coupling paths for additional suppression.

Control of Effective Gap Length: At high frequencies, even sub-millimeter-scale gaps can cause significant current localization and leakage due to resonance excitation. It is critical to enhance the electrical continuity across seams, refine edge transitions around apertures, and smooth abrupt structural changes to prevent field intensification and localized breakdown.