Submitted:

31 July 2025

Posted:

04 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

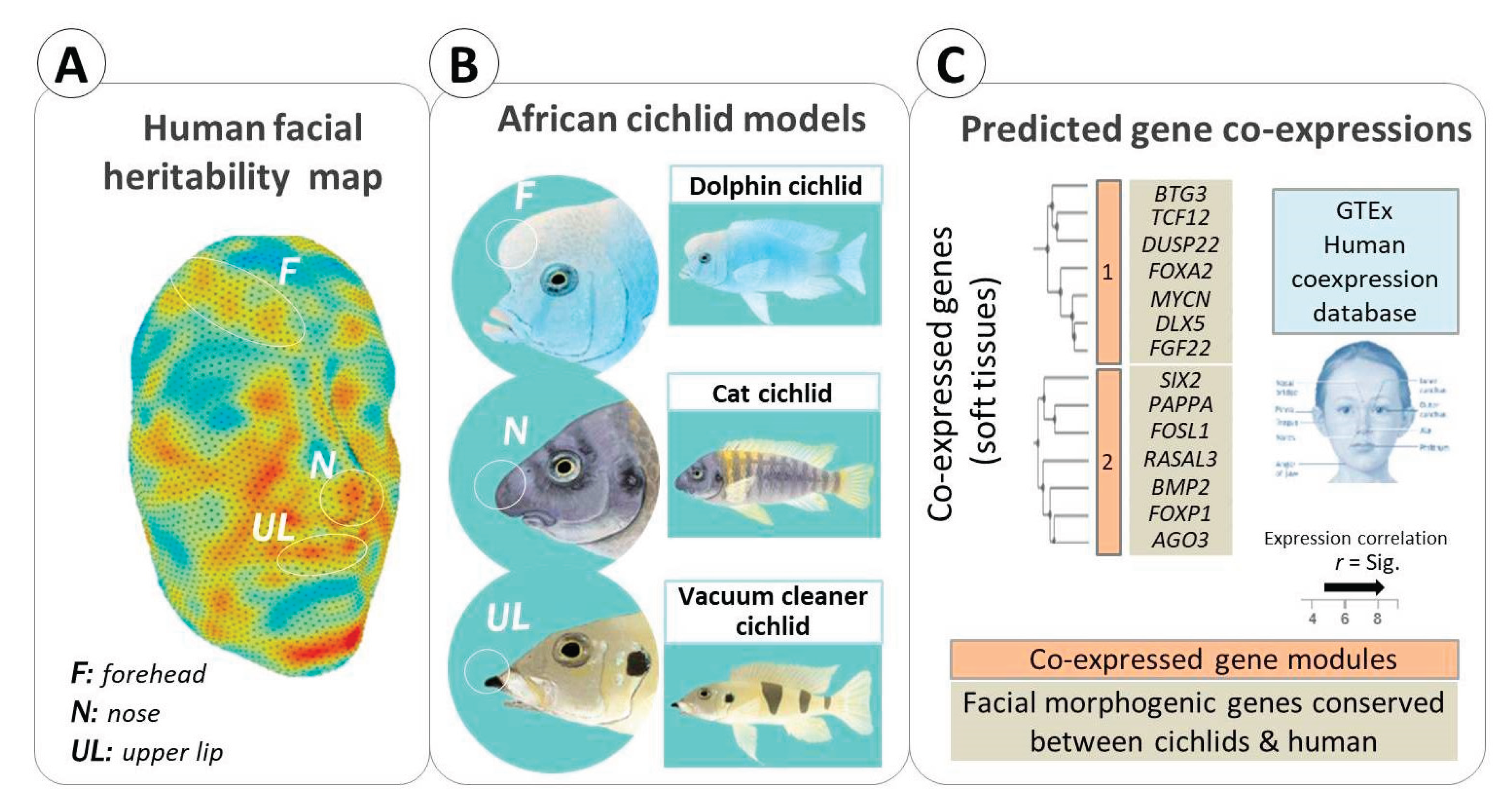

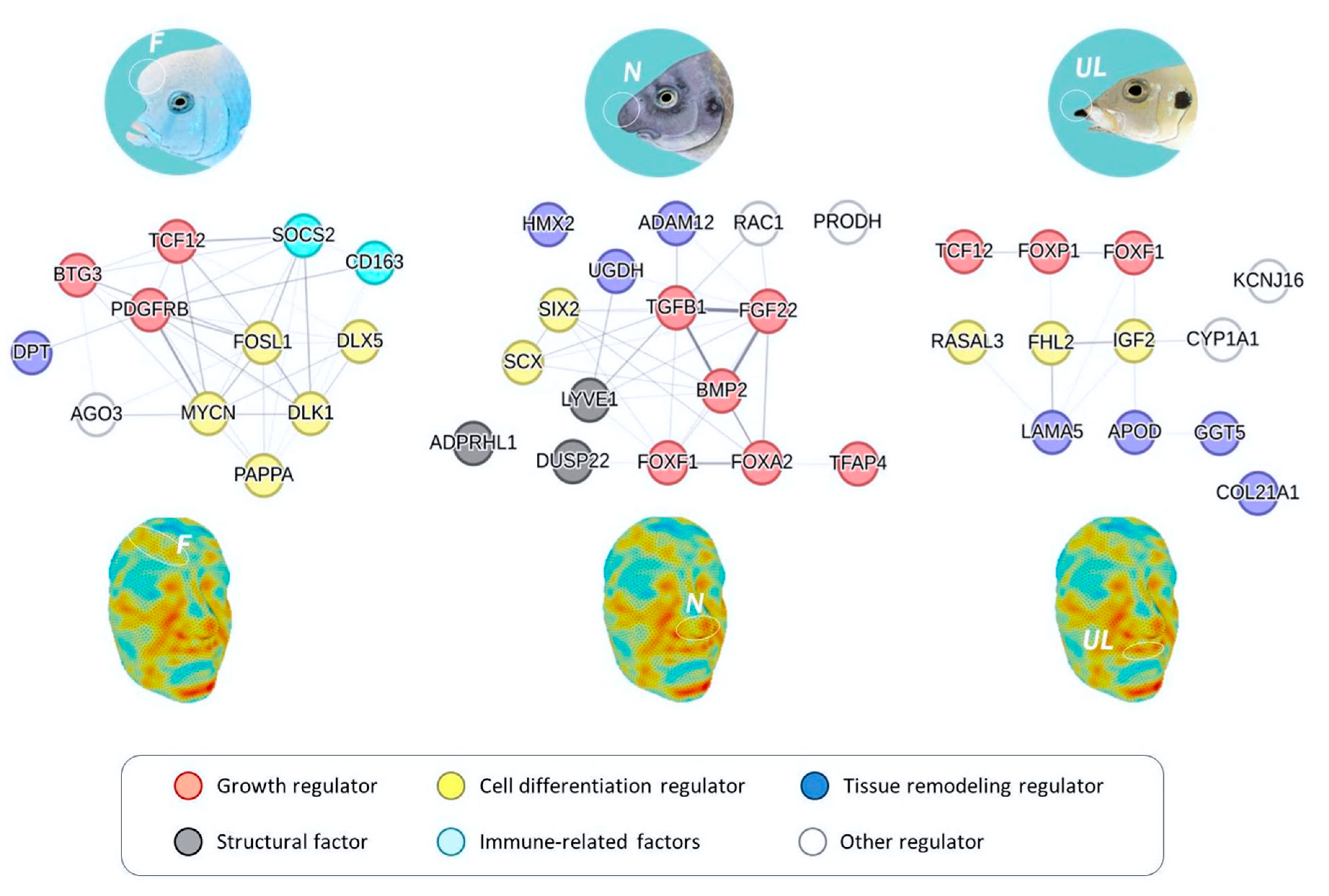

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Facial Soft Tissues

Cichlid Diversity in Facial Morphology Beyond Skeletal Tissues

Examples of Conserved Genes Underlying Facial Soft Tissue Morphogenesis

Conclusions

References

- Abdallah, B.M.; Ditzel, N.; Mahmood, A.; Isa, A.; Traustadottir, G.A.; Schilling, A.F.; Ruiz-Hidalgo, M.-J.; Laborda, J.; Amling, M.; Kassem, M. DLK1 is a novel regulator of bone mass that mediates estrogen deficiency-induced bone loss in mice. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2011, 26, 1457–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahi, E.P. Signalling pathways in trophic skeletal development and morphogenesis: Insights from studies on teleost fish. Dev. Biol. 2016, 420, 11–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahi, E.P.; Singh, P.; Duenser, A.; Gessl, W.; Sturmbauer, C. Divergence in larval jaw gene expression reflects differential trophic adaptation in haplochromine cichlids prior to foraging. BMC Evol. Biol. 2019, 19, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albertson, R.C.; Kocher, T.D. Genetic and developmental basis of cichlid trophic diversity. Heredity (Edinb) 2006, 97, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albertson, R.C.; Streelman, J.T.; Kocher, T.D. Directional selection has shaped the oral jaws of Lake Malawi cichlid fishes. PNAS 2003, 100, 5252–5257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhamoudi, K.M.; Bhat, J.; Nashabat, M.; Alharbi, M.; Alyafee, Y.; Asiri, A.; Umair, M.; Alfadhel, M. A Missense Mutation in the UGDH Gene Is Associated With Developmental Delay and Axial Hypotonia. Front. Pediatr. 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arseni, L.; Lombardi, A.; Orioli, D. From Structure to Phenotype: Impact of Collagen Alterations on Human Health; Int. J. Mol. Sci., 2018; Vol. 19, Page 1407 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgarten, L.; Machado-Schiaffino, G.; Henning, F.; Meyer, A. What big lips are good for: On the adaptive function of repeatedly evolved hypertrophied lips of cichlid fishes. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2015, 115, 448–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begemann, M.; Spengler, S.; Kordaß, U.; Schröder, C.; Eggermann, T. Segmental maternal uniparental disomy 7q associated with DLK1/GTL2 (14q32) hypomethylation. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2012, 158A, 423–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brawand, D., Wagner, C.E., Li, Y.I., Malinsky, M., Keller, I., Fan, S., Simakov, O., Ng, A.Y., Lim, Z.W., Bezault, E., Turner-Maier, J., Johnson, J., Alcazar, R., Noh, H.J., Russell, P., Aken, B., Alföldi, J., Amemiya, C., Azzouzi, N., Baroiller, J.-F., Barloy-Hubler, F., Berlin, A., Bloomquist, R., Carleton, K.L., Conte, M. a., D’Cotta, H., Eshel, O., Gaffney, L., Galibert, F., Gante, H.F., Gnerre, S., Greuter, L., Guyon, R., Haddad, N.S., Haerty, W., Harris, R.M., Hofmann, H. a., Hourlier, T., Hulata, G., Jaffe, D.B., Lara, M., Lee, A.P., MacCallum, I., Mwaiko, S., Nikaido, M., Nishihara, H., Ozouf-Costaz, C., Penman, D.J., Przybylski, D., Rakotomanga, M., Renn, S.C.P., Ribeiro, F.J., Ron, M., Salzburger, W., Sanchez-Pulido, L., Santos, M.E., Searle, S., Sharpe, T., Swofford, R., Tan, F.J., Williams, L., Young, S., Yin, S., Okada, N., Kocher, T.D., Miska, E. a., Lander, E.S., Venkatesh, B., Fernald, R.D., Meyer, A., Ponting, C.P., Streelman, J.T., Lindblad-Toh, K., Seehausen, O., Di Palma, F., 2014. The genomic substrate for adaptive radiation in African cichlid fish. Nature 513, 375–381. [CrossRef]

- Bredrup, C.; Stokowy, T.; McGaughran, J.; Lee, S.; Sapkota, D.; Cristea, I.; Xu, L.; Tveit, K.S.; Høvding, G.; Steen, V.M.; Rødahl, E.; Bruland, O.; Houge, G. A tyrosine kinase-activating variant Asn666Ser in PDGFRB causes a progeria-like condition in the severe end of Penttinen syndrome. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2018, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bull, R.; Rumsey, N. The Social Psychology of Facial Appearance, The Social Psychology of Facial Appearance; Springer New York, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona Baez, A.; Ciccotto, P.J.; Moore, E.C.; Peterson, E.N.; Lamm, M.S.; Roberts, N.B.; Coyle, K.P.; Barker, M.K.; Dickson, E.; Cass, A.N.; Pereira, G.S.; Zeng, Z.-B.; Guerrero, R.F.; Roberts, R.B. Gut length evolved under sexual conflict in Lake Malawi cichlids. Genetics 2025, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaimongkhol, T.; Mahakkanukrauh, P. The facial soft tissue thickness related facial reconstruction by ultrasonographic imaging: A review. Forensic Sci. Int. 2022, 337, 111365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, I.-H.; Han, J.; Iwata, J.; Chai, Y. Msx1 and Dlx5 function synergistically to regulate frontal bone development. genesis 2010, 48, 645–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, B.; Kuwalekar, M.; Fischer, B.; Woltering, J.; Biran, J.; Juntti, S.; Kratochwil, C.F.; Santos, M.E.; Almeida, M.V. Genome editing in East African cichlids and tilapias: state-of-the-art and future directions. Open Biol 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, M.; Diepeveen, E.T.; Muschick, M.; Santos, M.E.; Indermaur, A.; Boileau, N.; Barluenga, M.; Salzburger, W. The ecological and genetic basis of convergent thick-lipped phenotypes in cichlid fishes. Mol. Ecol. 2013, 22, 670–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Concannon, M.R.; Albertson, R.C. The genetic and developmental basis of an exaggerated craniofacial trait in East African cichlids. J. Exp. Zool. B. Mol. Dev. Evol. 2015, 324, 662–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conith, A.J.; Albertson, R.C. The cichlid oral and pharyngeal jaws are evolutionarily and genetically coupled. Nat. Commun. 2021, 2021 121 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conith, M.R.; Conith, A.J.; Albertson, R.C. Evolution of a soft-tissue foraging adaptation in African cichlids: Roles for novelty, convergence, and constraint. Evolution (N. Y). 2019, 73, 2072–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conith, M.R.; Hu, Y.; Conith, A.J.; Maginnis, M.A.; Webb, J.F.; Craig Albertson, R. Genetic and developmental origins of a unique foraging adaptation in a Lake Malawi cichlid genus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2018, 115, 7063–7068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conover, C.A.; Bale, L.K.; Overgaard, M.T.; Johnstone, E.W.; Laursen, U.H.; Füchtbauer, E.-M.; Oxvig, C.; van Deursen, J. Metalloproteinase pregnancy-associated plasma protein A is a critical growth regulatory factor during fetal development. Development 2004, 131, 1187–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, W.J.; Parsons, K.; McIntyre, A.; Kern, B.; McGee-Moore, A.; Albertson, R.C. Bentho-Pelagic Divergence of Cichlid Feeding Architecture Was Prodigious and Consistent during Multiple Adaptive Radiations within African Rift-Lakes. PLoS One 2010, 5, e9551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordero, D.R.; Brugmann, S.; Chu, Y.; Bajpai, R.; Jame, M.; Helms, J.A. Cranial neural crest cells on the move: their roles in craniofacial development. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2011, 155A, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotofana, S.; Lachman, N. Anatomy of the Facial Fat Compartments and their Relevance in Aesthetic Surgery. JDDG J. der Dtsch. Dermatologischen Gesellschaft 2019, 17, 399–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darrin Hulsey, C.; Zheng, J.; Holzman, R.; Alfaro, M.E.; Olave, M.; Meyer, A. Phylogenomics of a putatively convergent novelty: Did hypertrophied lips evolve once or repeatedly in Lake Malawi cichlid fishes? BMC Evol. Biol. 2018, 18, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dassati, S.; Waldner, A.; Schweigreiter, R. Apolipoprotein D takes center stage in the stress response of the aging and degenerative brain. Neurobiol. Aging. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Pater, J.M.; Nikkels, P.G.J.; Poot, M.; Eleveld, M.J.; Stigter, R.H.; Van Der Sijs-Bos, C.J.M.; Loneus, W.H.; Engelen, J.J.M. Striking Facial Dysmorphisms and Restricted Thymic Development in a Fetus with a 6-Megabase Deletion of Chromosome 14q. Pediatr. Dev. Pathol. 2005, 8, 497–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dines, J.N.; Liu, Y.J.; Neufeld-Kaiser, W.; Sawyer, T.; Ishak, G.E.; Tully, H.M.; Racobaldo, M.; Sanchez-Valle, A.; Disteche, C.M.; Juusola, J.; Torti, E.; McWalter, K.; Doherty, D.; Dipple, K.M. Expanding phenotype with severe midline brain anomalies and missense variant supports a causal role for FOXA2 in 20p11.2 deletion syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2019, 179, ajmg.a.61281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draaken, M.; Mughal, S.S.; Pennimpede, T.; Wolter, S.; Wittler, L.; Ebert, A.-K.; Rösch, W.; Stein, R.; Bartels, E.; Schmidt, D.; Boemers, T.M.; Schmiedeke, E.; Hoffmann, P.; Moebus, S.; Herrmann, B.G.; Nöthen, M.M.; Reutter, H.; Ludwig, M. Isolated bladder exstrophy associated with a de novo 0.9 Mb microduplication on chromosome 19p13.12. Birth Defects Res. Part A Clin. Mol. Teratol. 2013, 97, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duenser, A.; Singh, P.; Lecaudey, L.A.; Sturmbauer, C.; Albertson, R.C.; Gessl, W.; Ahi, E.P. Conserved Molecular Players Involved in Human Nose Morphogenesis Underlie Evolution of the Exaggerated Snout Phenotype in Cichlids. Genome Biol. Evol. 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Sergani, A.M.; Brandebura, S.; Padilla, C.; Butali, A.; Adeyemo, W.L.; Valencia-Ramírez, C.; Muñeton, C.P.R.; Moreno, L.M.; Buxó, C.J.; Long, R.E.; Neiswanger, K.; Shaffer, J.R.; Marazita, M.L.; Weinberg, S.M. Parents of Children With Nonsyndromic Orofacial Clefting Show Altered Palate Shape. Cleft Palate-Craniofacial J 2021, 58, 847–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Errichiello, E.; Novara, F.; Cremante, A.; Verri, A.; Galli, J.; Fazzi, E.; Bellotti, D.; Losa, L.; Cisternino, M.; Zuffardi, O. Dissection of partial 21q monosomy in different phenotypes: clinical and molecular characterization of five cases and review of the literature. Mol. Cytogenet. 2016, 9, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fantauzzo, K.A.; Soriano, P. PDGFRβ regulates craniofacial development through homodimers and functional heterodimers with PDGFRα. Genes Dev 2016, 30, 2443–2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farquharson, C.; Ahmed, S.F. Inflammation and linear bone growth: the inhibitory role of SOCS2 on GH/IGF-1 signaling. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2013, 28, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, W.; Leach, S.M.; Tipney, H.; Phang, T.; Geraci, M.; Spritz, R.A.; Hunter, L.E.; Williams, T. Spatial and Temporal Analysis of Gene Expression during Growth and Fusion of the Mouse Facial Prominences. PLoS One 2009, 4, e8066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finucane, H.K.; Bulik-Sullivan, B.; Gusev, A.; Trynka, G.; Reshef, Y.; Loh, P.R.; Anttila, V.; Xu, H.; Zang, C.; Farh, K.; Ripke, S.; Day, F.R.; Purcell, S.; Stahl, E.; Lindstrom, S.; Perry, J.R.B.; Okada, Y.; Raychaudhuri, S.; Daly, M.J.; Patterson, N.; Neale, B.M.; Price, A.L. Partitioning heritability by functional annotation using genome-wide association summary statistics. Nat. Genet. 2015, 2015 4711 47, 1228–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitoussi, R.; Beauchef, G.; Guéré, C.; André, N.; Vié, K. Localization, fate and interactions of Emilin-1 in human skin. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2019, 41, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, G.J.; Hulsey, C.D.; Bloomquist, R.F.; Uyesugi, K.; Manley, N.R.; Streelman, J.T. An ancient gene network is co-opted for teeth on old and new jaws. PLoS Biol 2009, 7, e31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fryer, G.; Iles, T.D. The Cichlid Fishes of the Great lakes of Africa: their Biology and Evolution. In Oliver and Boyd; Edinburgh, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Gervasini, C.; Castronovo, P.; Bentivegna, A.; Mottadelli, F.; Faravelli, F.; Giovannucci-Uzielli, M.L.; Pessagno, A.; Lucci-Cordisco, E.; Pinto, A.M.; Salviati, L.; Selicorni, A.; Tenconi, R.; Neri, G.; Larizza, L. High frequency of mosaic CREBBP deletions in Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome patients and mapping of somatic and germ-line breakpoints. Genomics 2007, 90, 567–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, J.; Bockmann, M.; Brook, A.; Gurr, A.; Hughes, T. Genetic and environmental contributions to the development of soft tissue facial profile: a twin study. Eur. J. Orthod. 2024, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, C.J.; Alexander, W.S. Suppressors of cytokine signalling and regulation of growth hormone action. Growth Horm. IGF Res. 2004, 14, 200–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, C.J.; Rico-Bautista, E.; Lorentzon, M.; Thaus, A.L.; Morgan, P.O.; Willson, T.A.; Zervoudakis, P.; Metcalf, D.; Street, I.; Nicola, N.A.; Nash, A.D.; Fabri, L.J.; Norstedt, G.; Ohlsson, C.; Flores-Morales, A.; Alexander, W.S.; Hilton, D.J. SOCS2 negatively regulates growth hormone action in vitro and in vivo. J. Clin. Invest. 2005, 115, 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guilmatre, A.; Legallic, S.; Steel, G.; Willis, A.; Di Rosa, G.; Goldenberg, A.; Drouin-Garraud, V.; Guet, A.; Mignot, C.; Des Portes, V.; Valayannopoulos, V.; Van Maldergem, L.; Hoffman, J.D.; Izzi, C.; Espil-Taris, C.; Orcesi, S.; Bonafé, L.; Le Galloudec, E.; Maurey, H.; Ioos, C.; Afenjar, A.; Blanchet, P.; Echenne, B.; Roubertie, A.; Frebourg, T.; Valle, D.; Campion, D. Type I hyperprolinemia: genotype/phenotype correlations. Hum. Mutat. 2010, 31, 961–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Tripathi, T.; Singh, N.; Bhutiani, N.; Rai, P.; Gopal, R. A review of genetics of nasal development and morphological variation. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2020, 9, 1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henning, F.; Machado-Schiaffino, G.; Baumgarten, L.; Meyer, A. Genetic dissection of adaptive form and function in rapidly speciating cichlid fishes. Evolution (N. Y). 2017, 71, 1297–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersberger-Zurfluh, M.A.; Papageorgiou, S.N.; Motro, M.; Kantarci, A.; Will, L.A.; Eliades, T. Facial soft tissue growth in identical twins. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2018, 154, 683–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higashiyama, H.; Kuroda, S.; Iwase, A.; Irie, N.; Kurihara, H. On the Maxillofacial Development of Mice, Mus musculus. J. Morphol. 2025, 286, e70032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hînganu, M.V.; Cucu, R.P.; Hînganu, D. Personalized Research on the Aging Face—A Narrative History; J. Pers. Med., 2024; Vol. 14, Page 343 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holleville, N.; Quilhac, A.; Bontoux, M.; Monsoro-Burq, A.-H.; élèn. BMP signals regulate Dlx5 during early avian skull development. Dev. Biol. 2003, 257, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoskens, H.; Li, J.; Indencleef, K.; Gors, D.; Larmuseau, M.H.D.; Richmond, S.; Zhurov, A.I.; Hens, G.; Peeters, H.; Claes, P. Spatially Dense 3D Facial Heritability and Modules of Co-heritability in a Father-Offspring Design. Front. Genet. 2018, 9, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosono, K.; Kawase, K.; Kurata, K.; Niimi, Y.; Saitsu, H.; Minoshima, S.; Ohnishi, H.; Yamamoto, Takahiro; Hikoya, A.; Tachibana, N.; Fukao, T.; Yamamoto, Tetsuya; Hotta, Y. A case of childhood glaucoma with a combined partial monosomy 6p25 and partial trisomy 18p11 due to an unbalanced translocation. Ophthalmic Genet 2020, 41, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Albertson, R.C. Hedgehog signaling mediates adaptive variation in a dynamic functional system in the cichlid feeding apparatus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2014, 1323154111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hufnagel, R.B.; Zimmerman, S.L.; Krueger, L.A.; Bender, P.L.; Ahmed, Z.M.; Saal, H.M. A new frontonasal dysplasia syndrome associated with deletion of the SIX2 gene. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2016, 170, 487–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulsey, C.D.; Machado-Schiaffino, G.; Keicher, L.; Ellis-Soto, D.; Henning, F.; Meyer, A. The Integrated Genomic Architecture and Evolution of Dental Divergence in East African Cichlid Fishes (Haplochromis chilotes x H. nyererei). G3 GenesGenomesGenetics 2017, 7, 3195–3202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarra, B.A.; Atit, R. What Do Animal Models Teach Us About Congenital Craniofacial Defects? Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2020, 1236, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jelenkovic, A.; Poveda, A.; Susanne, C.; Rebato, E. Common genetic and environmental factors among craniofacial traits in Belgian nuclear families: Comparing skeletal and soft-tissue related phenotypes. HOMO 2010, 61, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kautt, A.F.; Kratochwil, C.F.; Nater, A.; Machado-Schiaffino, G.; Olave, M.; Henning, F.; Torres-Dowdall, J.; Härer, A.; Hulsey, C.D.; Franchini, P.; Pippel, M.; Myers, E.W.; Meyer, A. Contrasting signatures of genomic divergence during sympatric speciation. Nat 2020, 2020 5887836 588, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosaki, K.; Saito, H.; Kosaki, R.; Torii, C.; Kishi, K.; Takahashi, T. Branchial arch defects and 19p13.12 microdeletion: Defining the critical region into a 0.8 M base interval. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2011, 155, 2212–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnaswamy, V.R.; Balaguru, U.M.; Chatterjee, S.; Korrapati, P.S. Dermatopontin augments angiogenesis and modulates the expression of transforming growth factor beta 1 and integrin alpha 3 beta 1 in endothelial cells. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2017, 96, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnaswamy, V.R.; Korrapati, P.S. Role of Dermatopontin in re-epithelialization: Implications on keratinocyte migration and proliferation. Sci. Rep. 2015, 4, 7385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucharczyk, M.; Kochański, A.; Jezela-Stanek, A.; Kugaudo, M.; Sielska-Rotblum, D.; Gutkowska, A.; Krajewska-Walasek, M. The first case of a patient with de novo partial distal 16q tetrasomy and a data’s review. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2014, 164, 2541–2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labalette, C.; Nouët, Y.; Sobczak-Thepot, J.; Armengol, C.; Levillayer, F.; Gendron, M.C.; Renard, C.A.; Regnault, B.; Chen, J.; Buendia, M.A.; Wei, Y. The LIM-only protein FHL2 regulates cyclin D1 expression and cell proliferation. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 15201–15208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landi, F.; Barraclough, J.; Evteev, A.; Anikin, A.; Satanin, L.; O’Higgins, P. The role of the nasal region in craniofacial growth: An investigation using path analysis. Anat. Rec. 2022, 305, 1892–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Tanno, P.; Poreau, B.; Devillard, F.; Vieville, G.; Amblard, F.; Jouk, P.-S.; Satre, V.; Coutton, C. Maternal complex chromosomal rearrangement leads to TCF12 microdeletion in a patient presenting with coronal craniosynostosis and intellectual disability. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2014, 164, 1530–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecaudey, L.A.; Singh, P.; Sturmbauer, C.; Duenser, A.; Gessl, W.; Ahi, E.P. Transcriptomics unravels molecular players shaping dorsal lip hypertrophy in the vacuum cleaner cichlid, Gnathochromis permaxillaris. BMC Genomics 2021, 22, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecaudey, L.A.; Sturmbauer, C.; Singh, P.; Ahi, E.P. Molecular mechanisms underlying nuchal hump formation in dolphin cichlid, Cyrtocara moorii. Sci. Rep. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liem, K.F. Evolutionary strategies and morphological innovations: cichlid pharyngeal jaws. Syst. Zool. 1973, 22, 425–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, M.H.; Jeun, J.H.; Kim, D.H.; Park, S.H.; Kim, S.J.; Lee, W.S.; Hwang, S.H.; Lim, J.Y.; Kim, S.W. Evaluation of Collagen Gel-Associated Human Nasal Septum-Derived Chondrocytes As a Clinically Applicable Injectable Therapeutic Agent for Cartilage Repair. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2020, 17, 387–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linnenkamp, B.D.W.; Raskin, S.; Esposito, S.E.; Herai, R.H. A comprehensive analysis of AHRR gene as a candidate for cleft lip with or without cleft palate. Mutat. Res.-Rev. Mutat. Res. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Little, A.C.; Jones, B.C.; Debruine, L.M. Facial attractiveness: evolutionary based research. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2011, 366, 1638–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Meng, L.; Shi, Q.; Liu, S.; Cui, C.; Hu, S.; Wei, Y. Dermatopontin promotes adhesion, spreading and migration of cardiac fibroblasts in vitro. Matrix Biol 2013, 32, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado-Schiaffino, G.; Kautt, A.F.; Torres-Dowdall, J.; Baumgarten, L.; Henning, F.; Meyer, A. Incipient speciation driven by hypertrophied lips in Midas cichlid fishes? Mol. Ecol. 2017, 26, 2348–2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machii, N.; Hatashima, R.; Niwa, T.; Taguchi, H.; Kimirei, I.A.; Mrosso, H.D.; Aibara, M.; Nagasawa, T.; Nikaido, M. Pronounced expression of extracellular matrix proteoglycans regulated by Wnt pathway underlies the parallel evolution of lip hypertrophy in East African cichlids. Elife 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacRae, V.E.; Horvat, S.; Pells, S.C.; Dale, H.; Collinson, R.S.; Pitsillides, A.A.; Ahmed, S.F.; Farquharson, C. Increased bone mass, altered trabecular architecture and modified growth plate organization in the growing skeleton of SOCS2 deficient mice. J. Cell. Physiol. 2009, 218, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manousaki, T.; Hull, P.M.; Kusche, H.; Machado-Schiaffino, G.; Franchini, P.; Harrod, C.; Elmer, K.R.; Meyer, A. Parsing parallel evolution: ecological divergence and differential gene expression in the adaptive radiations of thick-lipped Midas cichlid fishes from Nicaragua. Mol. Ecol. 2013, 22, 650–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marconi, A.; Vernaz, G.; Karunaratna, A.; Ngochera, M.J.; Durbin, R.; Santos, M.E. Genetic and Developmental Divergence in the Neural Crest Program between Cichlid Fish Species. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2024, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masonick, P.; Meyer, A.; Hulsey, C.D. A Kiss of Deep Homology: Partial Convergence in the Genomic Basis of Hypertrophied Lips in Cichlid Fish and Human Cleft Lip. Genome Biol. Evol. 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, H.S.; Penington, A.J.; Hardiman, R.; Fan, Y.; Clement, J.G.; Kilpatrick, N.M.; Claes, P.D. Modelling 3D craniofacial growth trajectories for population comparison and classification illustrated using sex-differences. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, N.; Liu, J.S.; Richarte, A.M.; Eskiocak, B.; Lovely, C. Ben; Tallquist, M.D.; Eberhart, J.K. Pdgfra and Pdgfrb genetically interact during craniofacial development. Dev. Dyn. 2016, 245, 641–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meerschaut, I.; Rochefort, D.; Revençu, N.; Pètre, J.; Corsello, C.; Rouleau, G.A.; Hamdan, F.F.; Michaud, J.L.; Morton, J.; Radley, J.; Ragge, N.; García-Miñaúr, S.; Lapunzina, P.; Bralo, M.P.; Mori, M.A.; Moortgat, S.; Benoit, V.; Mary, S.; Bockaert, N.; Oostra, A.; Vanakker, O.; Velinov, M.; De Ravel, T.J.L.; Mekahli, D.; Sebat, J.; Vaux, K.K.; DiDonato, N.; Hanson-Kahn, A.K.; Hudgins, L.; Dallapiccola, B.; Novelli, A.; Tarani, L.; Andrieux, J.; Parker, M.J.; Neas, K.; Ceulemans, B.; Schoonjans, A.S.; Prchalova, D.; Havlovicova, M.; Hancarova, M.; Budisteanu, M.; Dheedene, A.; Menten, B.; Dion, P.A.; Lederer, D.; Callewaert, B. FOXP1-related intellectual disability syndrome: A recognisable entity. J. Med. Genet. 2017, 54, 613–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metcalf, D.; Greenhalgh, C.J.; Viney, E.; Willson, T.A.; Starr, R.; Nicola, N.A.; Hilton, D.J.; Alexander, W.S. Gigantism in mice lacking suppressor of cytokine signalling-2. Nature 2000, 405, 1069–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, N.D.; Nance, M.A.; Wohler, E.S.; Hoover-Fong, J.E.; Lisi, E.; Thomas, G.H.; Pevsner, J. Molecular (SNP) analyses of overlapping hemizygous deletions of 10q25.3 to 10qter in four patients: Evidence for HMX2 and HMX3 as candidate genes in hearing and vestibular function. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2009, 149A, 669–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzamohammadi, F.; Kozlova, A.; Papaioannou, G.; Paltrinieri, E.; Ayturk, U.M.; Kobayashi, T. Distinct molecular pathways mediate Mycn and Myc-regulated miR-17-92 microRNA action in Feingold syndrome mouse models. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitteldorf, C.; Llamas-Velasco, M.; Schulze, H.-J.; Thoms, K.-M.; Mentzel, T.; Tronnier, M.; Kutzner, H. Deceptively bland cutaneous angiosarcoma on the nose mimicking hemangioma-A clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2018, 45, 652–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamad Shah, N.S.; Sulong, S.; Wan Sulaiman, W.A.; Halim, A.S. Two novel genes TOX3 and COL21A1 in large extended Malay families with nonsyndromic cleft lip and/or palate. Mol. Genet. Genomic Med. 2019, 7, e635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanda, R.S.; Meng, H.; Kapila, S.; Goorhuis, J. Growth changes in the soft tissue facial profile. Angle Orthod 1990, 60, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naqvi, S.; Hoskens, H.; Wilke, F.; Weinberg, S.M.; Shaffer, J.R.; Walsh, S.; Shriver, M.D.; Wysocka, J.; Claes, P. Decoding the Human Face: Progress and Challenges in Understanding the Genetics of Craniofacial Morphology. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 2022, 23, 383–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navon, D.; Male, I.; Tetrault, E.R.; Aaronson, B.; Karlstrom, R.O.; Craig Albertson, R. Hedgehog signaling is necessary and sufficient to mediate craniofacial plasticity in teleosts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2020, 117, 19321–19327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, C.F.; Ng, P.K.S.; Lui, V.W.Y.; Li, J.; Chan, J.Y.W.; Fung, K.P.; Ng, Y.K.; Lai, P.B.S.; Tsui, S.K.W. FHL2 exhibits anti-proliferative and anti-apoptotic activities in liver cancer cells. Cancer Lett 2011, 304, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okello, D.O.; Iyyanar, P.P.R.; Kulyk, W.M.; Smith, T.M.; Lozanoff, S.; Ji, S.; Nazarali, A.J. Six2 Plays an Intrinsic Role in Regulating Proliferation of Mesenchymal Cells in the Developing Palate. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, X.; Dong, N.; Zheng, Z. Small leucine-rich proteoglycans in skin wound healing. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 10, 501915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parnell, N.F.; Hulsey, C.D.; Streelman, J.T. THE GENETIC BASIS OF A COMPLEX FUNCTIONAL SYSTEM. Evolution (N. Y). 2012, 66, 3352–3366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parsons, K.J.; Trent Taylor, A.; Powder, K.E.; Albertson, R.C. Wnt signalling underlies the evolution of new phenotypes and craniofacial variability in Lake Malawi cichlids. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peixoto da-Silva, J.; Lourenço, S.; Nico, M.; Silva, F.H.; Martins, M.T.; Costa-Neves, A. Expression of laminin-5 and integrins in actinic cheilitis and superficially invasive squamous cell carcinomas of the lip. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2012, 208, 598–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peñaherrera, M.S.; Weindler, S.; Van Allen, M.I.; Yong, S.-L.; Metzger, D.L.; McGillivray, B.; Boerkoel, C.; Langlois, S.; Robinson, W.P. Methylation profiling in individuals with Russell-Silver syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2010, 152A, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piard, J.; Rozé, V.; Czorny, A.; Lenoir, M.; Valduga, M.; Fenwick, A.L.; Wilkie, A.O.M.; Van Maldergem, L. TCF12 microdeletion in a 72-year-old woman with intellectual disability. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2015, 167, 1897–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinchefsky, E.; Laneuville, L.; Srour, M. Distal 22q11.2 Microduplication. Child Neurol. Open 2017, 4, 2329048X1773765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powder, K.E.; Albertson, R.C. Cichlid fishes as a model to understand normal and clinical craniofacial variation. Dev. Biol. 2016, 415, 338–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powder, K.E.; Cousin, H.; McLinden, G.P.; Craig Albertson, R. A nonsynonymous mutation in the transcriptional regulator lbh is associated with cichlid craniofacial adaptation and neural crest cell development. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2014, 31, 3113–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powder, K.E.; Milch, K.; Asselin, G.; Albertson, R.C. Constraint and diversification of developmental trajectories in cichlid facial morphologies. Evodevo 2015, 6, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, W.; Zhang, M.; Wan, K.; Xie, Y.; Du, S.; Li, J.; Mu, X.; Qiu, J.; Xue, X.; Zhuang, X.; Wu, Y.; Liu, F.; Wang, S. Genetic evidence for facial variation being a composite phenotype of cranial variation and facial soft tissue thickness. J. Genet. Genomics 2022, 49, 934–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quigley, D.I.; Kaiser-Rogers, K.; Aylsworth, A.S.; Rao, K.W. Submicroscopic deletion 9(q34.4) and duplication 19(p13.3): Identified by subtelomere specific FISH probes. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2004, 125A, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinto-Sánchez, M.; Muñoz-Muñoz, F.; Gomez-Valdes, J.; Cintas, C.; Navarro, P.; De Cerqueira, C.C.S.; Paschetta, C.; De Azevedo, S.; Ramallo, V.; Acuña-Alonzo, V.; Adhikari, K.; Fuentes-Guajardo, M.; Hünemeier, T.; Everardo, P.; De Avila, F.; Jaramillo, C.; Arias, W.; Gallo, C.; Poletti, G.; Bedoya, G.; Bortolini, M.C.; Canizales-Quinteros, S.; Rothhammer, F.; Rosique, J.; Ruiz-Linares, A.; Gonzalez-Jose, R. Developmental pathways inferred from modularity, morphological integration and fluctuating asymmetry patterns in the human face. Sci. Reports 2018, 2018 81 8, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reijnders, M.R.F.; Ansor, N.M.; Kousi, M.; Yue, W.W.; Tan, P.L.; Clarkson, K.; Clayton-Smith, J.; Corning, K.; Jones, J.R.; Lam, W.W.K.; Mancini, G.M.S.; Marcelis, C.; Mohammed, S.; Pfundt, R.; Roifman, M.; Cohn, R.; Chitayat, D.; Millard, T.H.; Katsanis, N.; Brunner, H.G.; Banka, S. RAC1 Missense Mutations in Developmental Disorders with Diverse Phenotypes. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2017, 101, 466–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richmond, S.; Howe, L.J.; Lewis, S.; Stergiakouli, E.; Zhurov, A. Facial Genetics: A Brief Overview. Front. Genet. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, R.B.; Hu, Y.; Albertson, R.C.; Kocher, T.D. Craniofacial divergence and ongoing adaptation via the hedgehog pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011, 108, 13194–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rometsch, S.J.; Torres-Dowdall, J.; Machado-Schiaffino, G.; Karagic, N.; Meyer, A. Dual function and associated costs of a highly exaggerated trait in a cichlid fish. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 11, 17496–17508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruff, M.; Leyme, A.; Le Cann, F.; Bonnier, D.; Le Seyec, J.; Chesnel, F.; Fattet, L.; Rimokh, R.; Baffet, G.; Théret, N. The Disintegrin and Metalloprotease ADAM12 Is Associated with TGF-β-Induced Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0139179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samson, N.; Fink, B.; Matts, P.J. Visible skin condition and perception of human facial appearance. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2010, 32, 167–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandell, R.F.; Carter, J.M.; Folpe, A.L. Solitary (juvenile) xanthogranuloma: a comprehensive immunohistochemical study emphasizing recently developed markers of histiocytic lineage. Hum. Pathol. 2015, 46, 1390–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.E.; Braasch, I.; Boileau, N.; Meyer, B.S.; Sauteur, L.; Böhne, A.; Belting, H.G.; Affolter, M.; Salzburger, W. The evolution of cichlid fish egg-spots is linked with a cis-regulatory change. Nat. Commun. 2014, 2014 51 5, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.E.; Lopes, J.F.; Kratochwil, C.F. East African cichlid fishes. EvoDevo 2023, 14, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saultz, J.N.; Kaffenberger, B.H.; Taylor, M.; Heerema, N.A.; Klisovic, R. Novel Chromosome 5 Inversion Associated With PDGFRB Rearrangement in Hypereosinophilic Syndrome. JAMA Dermatology 2016, 152, 1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiavinato, A.; Marcous, F.; Zuk, A. V.; Keene, D.R.; Tufa, S.F.; Mosquera, L.M.; Zigrino, P.; Mauch, C.; Eckes, B.; Francois, K.; De Backer, J.; Hunzelmann, N.; Moinzadeh, P.; Krieg, T.; Callewaert, B.; Sengle, G. New insights into the structural role of EMILINs within the human skin microenvironment. Sci. Reports 2024, 2024 141 14, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.P.; Fenwick, A.L.; Brockop, M.S.; McGowan, S.J.; Goos, J.A.C.; Hoogeboom, A.J.M.; Brady, A.F.; Jeelani, N.O.; Lynch, S.A.; Mulliken, J.B.; Murray, D.J.; Phipps, J.M.; Sweeney, E.; Tomkins, S.E.; Wilson, L.C.; Bennett, S.; Cornall, R.J.; Broxholme, J.; Kanapin, A.; Consortium; 500 Whole-Genome Sequences (WGS500); Johnson, D.; Wall, S.A.; Spek; van der, P.J.; Mathijssen, I.M.J.; Maxson, R.E.; Twigg, S.R.F.; Wilkie, A.O.M. Mutations in TCF12, encoding a basic helix-loop-helix partner of TWIST1, are a frequent cause of coronal craniosynostosis. Nat. Genet. 2013, 453 45, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaw-Smith, C. Genetic factors in esophageal atresia, tracheo-esophageal fistula and the VACTERL association: Roles for FOXF1 and the 16q24.1 FOX transcription factor gene cluster, and review of the literature. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, P.; Ahi, E.P.; Sturmbauer, C. Gene coexpression networks reveal molecular interactions underlying cichlid jaw modularity. BMC Ecol. Evol. 2021, 21, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, P.; Tschanz-Lischer, H.; Ford, K.; Ahi, E.P.; Haesler, M.P.; Mwaiko, S.; Meier, J.I.; Marques, D.; Bruggman, R.; Kishe, M.; Seehausen, O. Highly modular genomic architecture underlies combinatorial mechanism of speciation and adaptive radiation. bioRxiv 2025, 2025.07.07.663194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Som, P.M.; Naidich, T.P. Illustrated review of the embryology and development of the facial region, part 1: Early face and lateral nasal cavities. AJNR. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2013, 34, 2233–2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Chae, H.S.; Shin, J.W.; Sung, J.; Song, Y.M.; Baek, S.H.; Kim, Y.H. Influence of heritability on craniofacial soft tissue characteristics of monozygotic twins, dizygotic twins, and their siblings using Falconer’s method and principal components analysis. Korean J. Orthod. 2018, 49, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuppia, L.; Capogreco, M.; Marzo, G.; La Rovere, D.; Antonucci, I.; Gatta, V.; Palka, G.; Mortellaro, C.; Tetè, S. Genetics of Syndromic and Nonsyndromic Cleft Lip and Palate. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2011, 22, 1722–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugimoto, Y.; Takimoto, A.; Akiyama, H.; Kist, R.; Scherer, G.; Nakamura, T.; Hiraki, Y.; Shukunami, C. Scx+/Sox9+ progenitors contribute to the establishment of the junction between cartilage and tendon/ligament. Development 2013, 140, 2280–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabo-Rogers, H.L.; Geetha-Loganathan, P.; Nimmagadda, S.; Fu, K.K.; Richman, J.M. FGF signals from the nasal pit are necessary for normal facial morphogenesis. Dev. Biol. 2008, 318, 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takenouchi, T.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Tanikawa, A.; Kosaki, R.; Okano, H.; Kosaki, K. Novel Overgrowth Syndrome Phenotype Due to Recurrent De Novo PDGFRB Mutation. J. Pediatr. 2015, 166, 483–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talbot, J.C.; Johnson, S.L.; Kimmel, C.B. hand2 and Dlx genes specify dorsal, intermediate and ventral domains within zebrafish pharyngeal arches. Development 2010, 137, 2507–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, T.Y.; Gonzaga-Jauregui, C.; Bhoj, E.J.; Strauss, K.A.; Brigatti, K.; Puffenberger, E.; Li, D.; Xie, L.Q.; Das, N.; Skubas, I.; Deckelbaum, R.A.; Hughes, V.; Brydges, S.; Hatsell, S.; Siao, C.J.; Dominguez, M.G.; Economides, A.; Overton, J.D.; Mayne, V.; Simm, P.J.; Jones, B.O.; Eggers, S.; Le Guyader, G.; Pelluard, F.; Haack, T.B.; Sturm, M.; Riess, A.; Waldmueller, S.; Hofbeck, M.; Steindl, K.; Joset, P.; Rauch, A.; Hakonarson, H.; Baker, N.L.; Farlie, P.G. Monoallelic BMP2 Variants Predicted to Result in Haploinsufficiency Cause Craniofacial, Skeletal, and Cardiac Features Overlapping Those of 20p12 Deletions. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2017, 101, 985–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, P.S.; Kim, J.; Nunez, S.; Glogauer, M.; Kaartinen, V. Neural crest cell-specific deletion of Rac1 results in defective cell-matrix interactions and severe craniofacial and cardiovascular malformations. Dev. Biol. 2010, 340, 613–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokita, M.J.; Chow, P.M.; Mirzaa, G.; Dikow, N.; Maas, B.; Isidor, B.; Le Caignec, C.; Penney, L.S.; Mazzotta, G.; Bernardini, L.; Filippi, T.; Battaglia, A.; Donti, E.; Earl, D.; Prontera, P. Five children with deletions of 1p34.3 encompassing AGO1 and AGO3. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2015, 23, 761–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Dowdall, J.; Meyer, A. Sympatric and Allopatric Diversification in the Adaptive Radiations of Midas Cichlids in Nicaraguan Lakes. In The Behavior, Ecology and Evolution of Cichlid Fishes; Springer; Dordrecht, 2021; pp. 175–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsagkrasoulis, D.; Hysi, P.; Spector, T.; Montana, G. Heritability maps of human face morphology through large-scale automated three-dimensional phenotyping. Sci. Reports 2017, 2017 71 7, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Mater, D.; Knelson, E.H.; Kaiser-Rogers, K.A.; Armstrong, M.B. Neuroblastoma in a pediatric patient with a microduplication of 2p involving the MYCN locus. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2013, 161, 605–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vera-Carbonell, A.; Moya-Quiles, M.R.; Ballesta-Martínez, M.; López-González, V.; Bafallíu, J.A.; Guillén-Navarro, E.; López-Expósito, I. Rapp–Hodgkin syndrome and SHFM1 patients: Delineating the p63–Dlx5/Dlx6 pathway. Gene 2012, 497, 292–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos, J.A.; Abbondanzo, S.L.; Barekman, C.L.; Andriko, J.W.; Miettinen, M.; Aguilera, N.S. Histiocytic sarcoma: a study of five cases including the histiocyte marker CD163. Mod. Pathol. 2005, 18, 693–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, M.; Wehrhan, F.; Deschner, J.; Sander, J.; Ries, J.; Möst, T.; Bozec, A.; Gölz, L.; Kesting, M.; Lutz, R. The Special Developmental Biology of Craniofacial Tissues Enables the Understanding of Oral and Maxillofacial Physiology and Diseases; Int. J. Mol. Sci., 2021; Vol. 22, Page 1315 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.; Kaiser, M.; Gershtein, Y.; Schnyder, D.; Deviatiiarov, R.; Gazizova, G.; Shagimardanova, E.; Zikmund, T.; Kerckhofs, G.; Ivashkin, E.; Batkovskyte, D.; Newton, P.T.; Andersson, O.; Fried, K.; Gusev, O.; Zeberg, H.; Kaiser, J.; Adameyko, I.; Chagin, A.S. The level of protein in the maternal murine diet modulates the facial appearance of the offspring via mTORC1 signaling. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Liu, H.; Lan, Y.; Aronow, B.J.; Kalinichenko, V. V.; Jiang, R. A Shh-Foxf-Fgf18-Shh Molecular Circuit Regulating Palate Development. PLOS Genet 2016, 12, e1005769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Hu, L.; Liu, X.; Zhan, G.; Mei, M.; Wang, H.; Zhang, X.; Qiu, Z.; Zhou, W.; Yang, L. A Novel MYCN Variant Associated with Intellectual Disability Regulates Neuronal Development. Neurosci. Bull. 2018, 34, 854–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, S.; Liu, D.; Zhao, Z.; Song, H.; Peng, K. Identification and validation of GIMAP family genes as immune-related prognostic biomarkers in lung adenocarcinoma. Heliyon 2024, 10, 33111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).