1. Introduction

The Alzheimer’s disease (AD), a progressive neurodegenerative disorder, manifests through irreversible cognitive decline, memory loss, and neuropsychiatric disturbances, ultimately leading to dementia [

1,

2]. Pathologically, AD is defined by extracellular amyloid-beta (Aβ) plaques, intra-neuronal neurofibrillary tangles of hyperphosphorylated tau proteins, synaptic degeneration, and cholinergic dysfunction [

3,

4]. Despite decades of research, existing therapies, i.e., primarily targeting Aβ aggregation or acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibition, offer only symptomatic relief and fail to halt the disease progression [

5]. With global AD cases projected to triple by 2050 due to aging populations and the absence of disease-modifying treatments, innovative strategies addressing its multi-factorial pathogenesis are imperative [

6,

7].

The central etiologies of AD are oxidative stress, Aβ fibrillization, and tau hyperphosphorylation, which synergistically drive neuronal loss and synaptic failure [

8,

9]. Among these, Aβ aggregation remains a pivotal therapeutic target, as soluble oligomers and mature fibrils disrupt membrane integrity, impair mitochondrial function, and propagate neurotoxicity [

4]. Natural products, with their structural diversity, multi-target potential, and favourable safety profiles, have emerged as promising candidates in modulating Aβ pathology [

10,

11]. In particular, gyrophoric acid, a lichen-derived secondary metabolites belonging to the depside class of polyphenolic compounds [

12], has been shown remarkable antioxidant properties [

13,

14] and anti-amyloid activity [

15]. Our prior works have demonstrated that application of gyrophoric acid effectively suppressed Aβ42 fibrillation, destabilized preformed fibrils, and protected neuronal cells from Aβ42-induced cytotoxicity, highlighting its neuroprotective potential [

15].

Translating natural compounds, e.g. gyrophoric acid, into clinical use requires overcoming challenges related to pharmacokinetic optimization and target specificity. For instance, gyrophoric acid’s hydrophobic structure facilitates the interactions with Aβ42’s amyloidogenic regions, but it may also limit its solubility and blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability. To address these limitations, we employed an

in silico pipeline integrating molecular docking, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations [

16], and ADMET (absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, toxicity) profiling [

17,

18] to reveal the possible drug-ability of gyrophoric acid. In addition,

in vitro biochemical analyses using Thioflavin T (ThT) assays and real-time confocal microscopy were further confirmed the role of gyrophoric acid in Aβ42 fibrillation. The current findings not only uncover the entropic dominance of gyrophoric acid’s Aβ42 stabilization in mirroring the “conformational selection” mechanism of intrinsically disordered proteins; but also lay the groundwork in developing next-generation anti-amyloid therapeutics with improved bioavailability and target engagement.

2. Results

2.1. XP Molecular Docking and MM-GBSA Calculaion

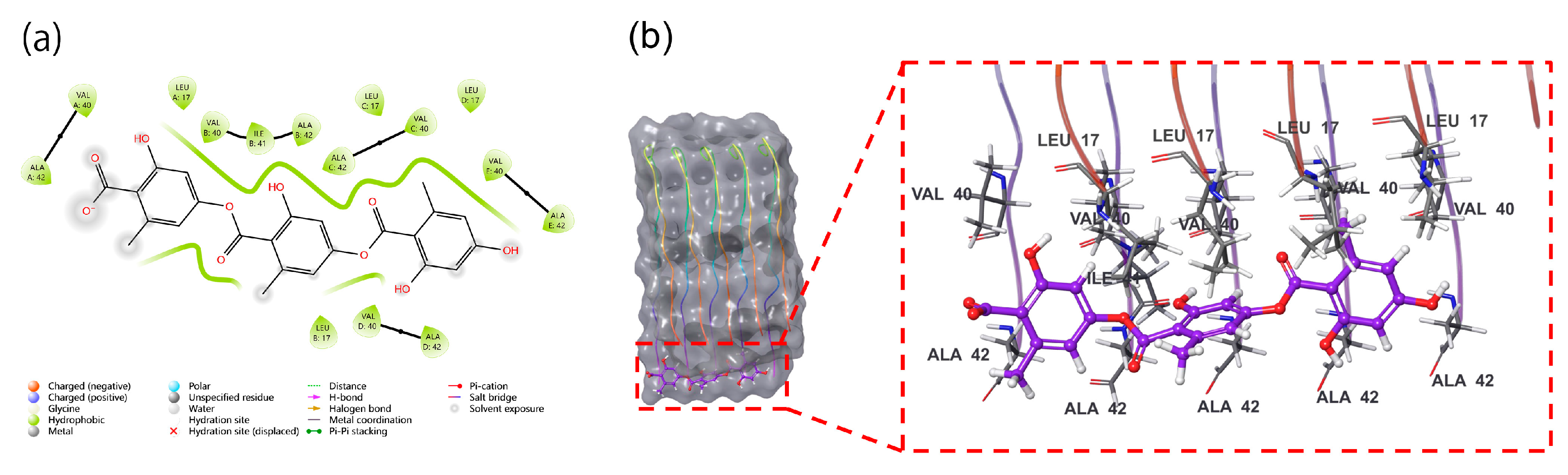

The computational profiling of gyrophoric acid revealed a paradoxical binding signature: while the Glide XP docking score (-1.121) suggested a weak initial binding affinity, the MM-GBSA-derived binding free energy (dG Bind -27.3 kcal/mol) indicated robust thermodynamic stabilization of the complex. Structural representation of gyrophoric acid showed the possible binding to surface of Aβ42 peptide's active pocket. Despite the spatial proximity, no significant non-covalent interactions, e.g., hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, or π-π stacking, were identified between gyrophoric acid and the protein. This dichotomy implied a multi-phase binding mechanism (Figure 1a), where kinetic barriers during the initial docking phase, such as suboptimal ligand positioning or partial desolation penalties, limited the binding efficiency. Hydrophobic interactions between gyrophoric acid and key residues of Aβ42 peptide were identified (Figure 1b). Critical residues mediating the hydrophobic contacts include Ala42 (chain E), Val40 (chain E), Val40 (chain C), Ala42 (chain C), and Ala42 (chain B). These residues collectively form a hydrophobic pocket that stabilizes gyrophoric acid binding, aligning with the strongly favourable MM-GBSA binding free energy (dG Bind -27.3 kcal/mol). The absence of conventional hydrogen bonds, or electrostatic interactions, suggests a dominance of entropically driven hydrophobic effects in the ligand stabilization.

This behaviour mirrors the “conformational selection” paradigm being observed in intrinsically disordered proteins, like Ab, where ligand binding stabilizes transient low-population states of the peptide [

17,

19]. Notably, the absence of canonical hydrogen bonds and the dominance of hydrophobic contacts suggest that the entropic gains from solvent displacement and van der Waals packing, rather than the enthalpic forces, drive the observed stabilization (

Figure 1). These findings raise intriguing pharmacological implications, i.e., the weak initial binding may reduce off-target interactions, while strong thermodynamic stabilization could enhance target residence time.

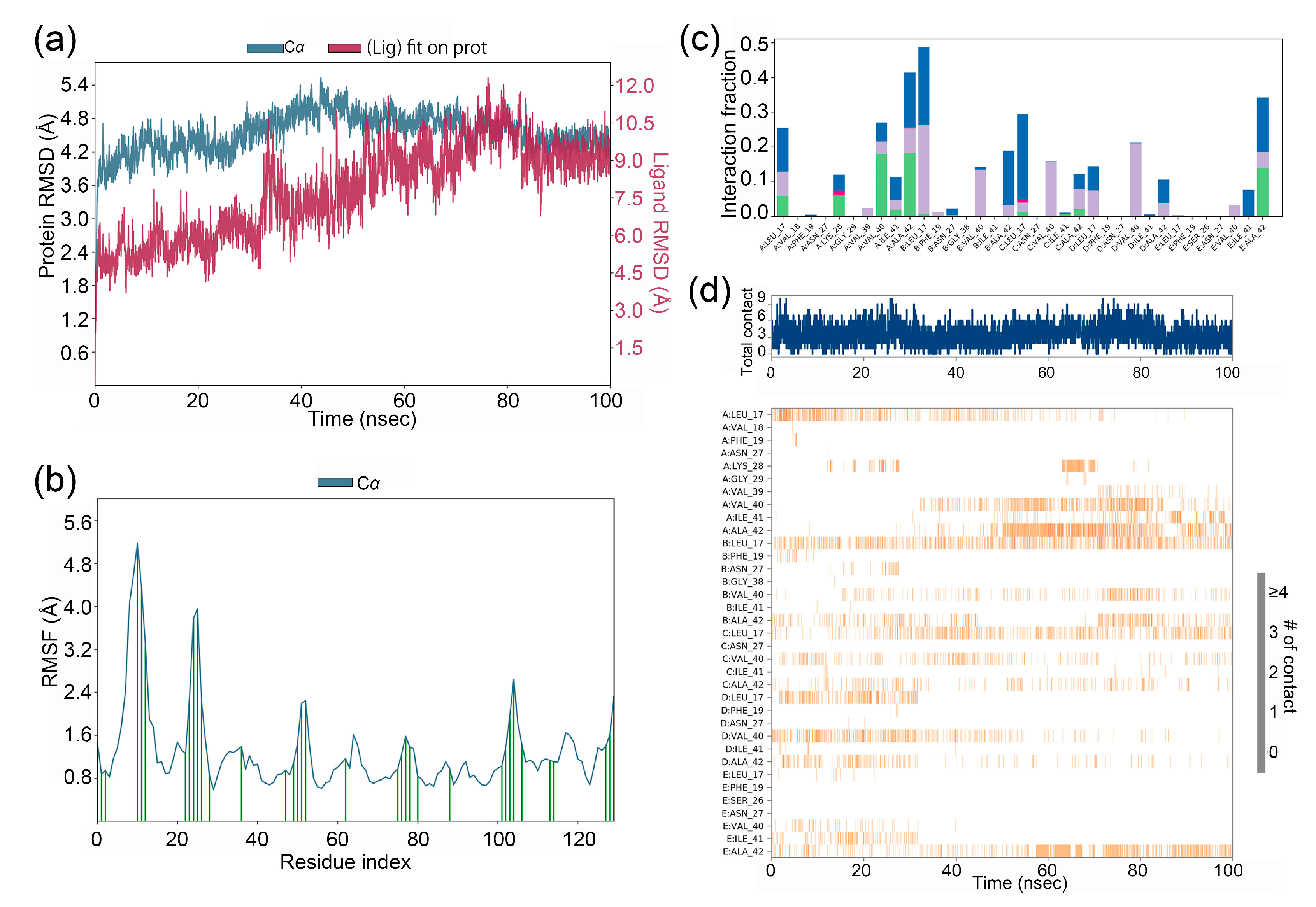

2.2. Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation

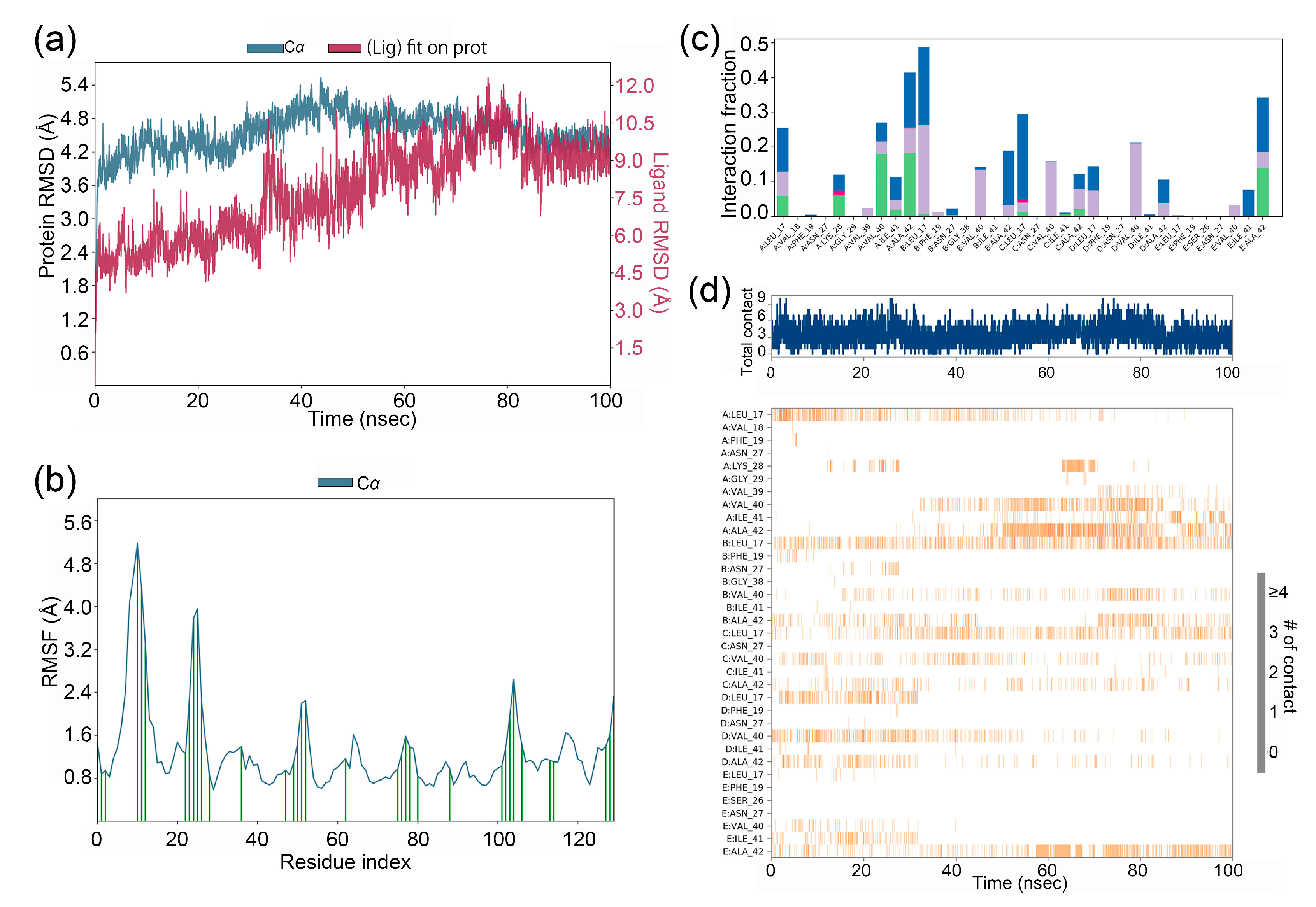

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, offering atomic-level precision and high temporal resolution, are now integral to drug development, which drive the design/optimization of therapeutics (e.g., small molecules, peptides, proteins) and elucidate the structural basis of diseases. MD simulations of the gyrophoric acid with Aβ42 peptide complex were performed for 100 ns, and the resulting trajectories were analysed for conformational stability (

Figure 2a). As shown in the figure, the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) plotted against simulation time revealed minor fluctuations (≤2.0 Å) across all systems, indicating that the complexes achieved stable conformational states. Specifically, the complex of gyrophoric acid with Aβ42 peptide exhibited relative stability after 70 ns, with RMSD values converging within a narrow range (1.2–1.8 Å), demonstrating that the system has reached equilibrium in the latter phase of the simulation.

The RMSF (root mean square fluctuation) analysis of Ab42 peptide chain revealed local conformational changes, with peaks corresponding to regions exhibiting the highest flexibility during the simulation. As shown in

Figure 2b, the binding to gyrophoric acid increased structural flexibility in the protein, particularly within residue regions of 5-20AA, 20-30AA, and 45-55AA.

Figure 2c depicts the interaction profiles between the ligand and key protein residues during the 100-ns simulation. The X-axis lists the specific binding site residues, while the Y-axis represents the fraction of simulation time at each interaction. While initial docking revealed no significant non-covalent interactions, and subsequent MD simulations in identifying protein-ligand interactions were monitored throughout the simulation. The interaction could be categorized into four types: hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, ionic bridges, and water bridges. Hydrogen bonds are represented by green, hydrophobic interactions by purple, and water bridges by blue. Key residues critical for binding include Leu17 (chain A), Val40 (chain A), Ala42 (chain A), Leu17 (chain B), Leu17 (chain C), and Ala42 (chain E), with interactions dominated by water bridges, hydrophobic forces and hydrogen bonds (

Figure 2c). As a result, these residues underwent several interactions over the duration of simulation.

Figure 2d shows the analysis revealed frequent ligand contacts (indicated by darker orange shading) with residues Leu17 (chain A), Val40 (chain A), Ala42 (chain A), Leu17 (chain B), Leu17 (chain C), and Ala42 (chain E).

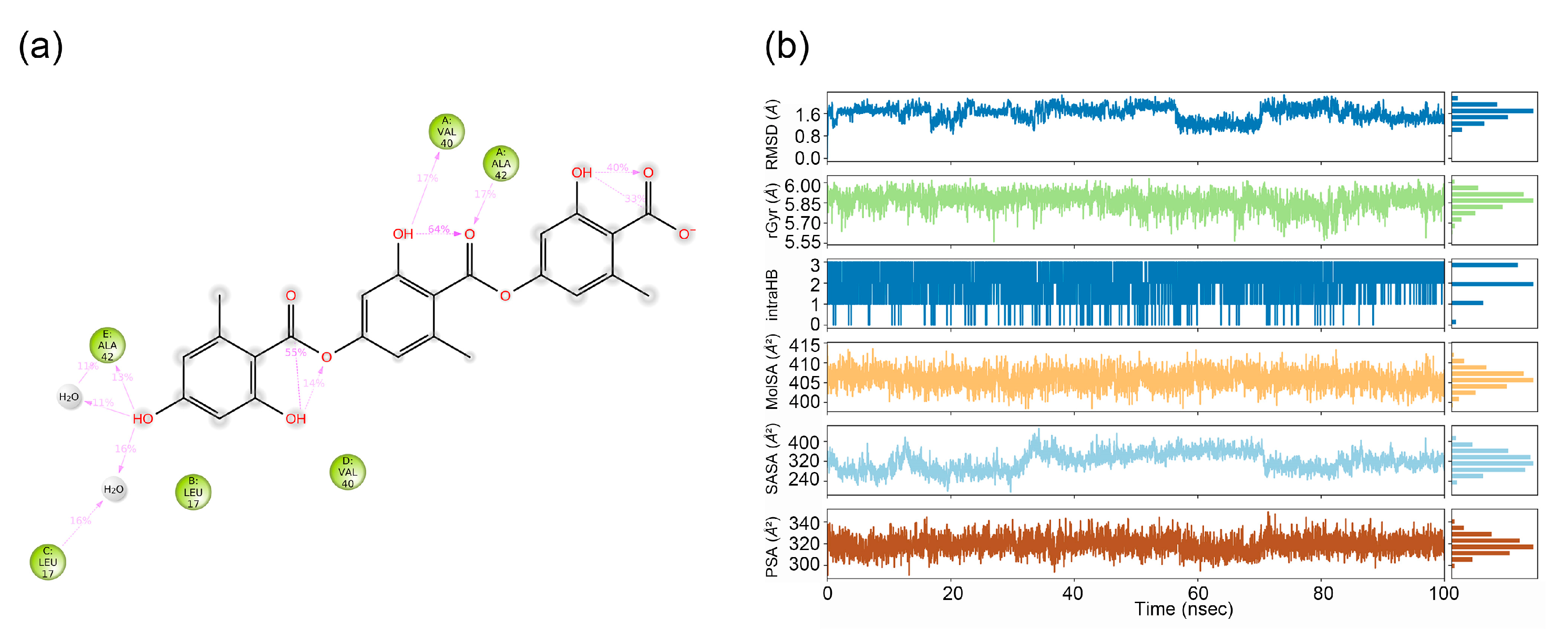

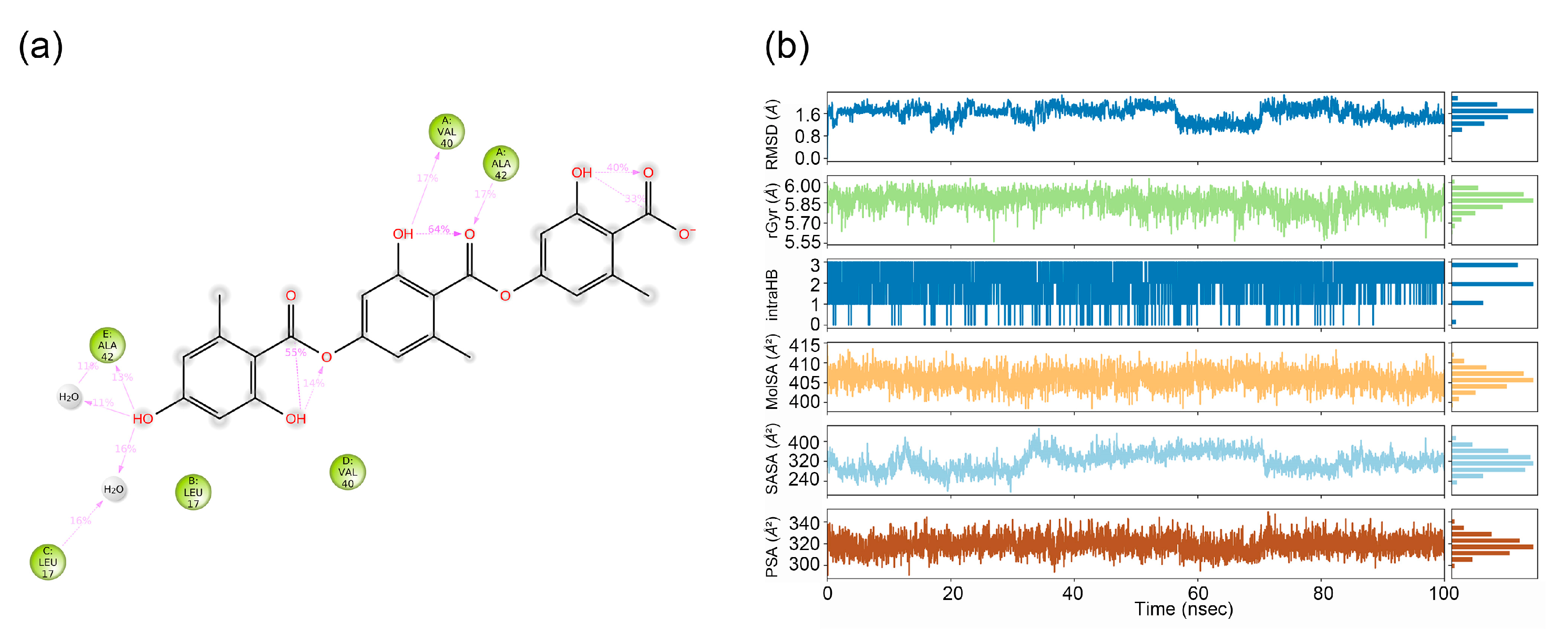

A schematic of detailed ligand atom interactions with the protein residues. Interactions that occur more than 10.0% of the simulation time in the selected trajectory (0.00 through 100.01 ns) (

Figure 3a). The diagram highlights interactions occurring for >10.0% of the simulation time (i.e., interaction durations exceeding 10 ns within the 100 ns trajectory). As shown in the left panel, gyrophoric acid directly forms hydrogen bonds with residues Ala42 (17%) (chain A), Val40 (17%) (chain A), and Ala42 (13%) (chain E) of Ab42 peptide. Water bridges mediated by intervening water molecules are observed with Ala42 (11%) (chain E) and Leu17 (16%) (chain C). Simulation time served as a quantitative metric to evaluate interaction stability and strength.

Figure 3b presents six dynamic parameters of gyrophoric acid during the 100-ns MD simulation: RMSD stabilized near 1.6 Å (range: 0.8–1.8 Å); radius of gyration (rGyr) equilibrated at ~5.85 Å (5.55–6.00 Å); intense intramolecular hydrogen bonds occurred at 0–22 ns and ~87 ns; molecular surface area (MolSA) averaged 408 Ų (395–415 Ų); solvent-accessible surface area (SASA) fluctuated widely (160–400 Ų); and polar surface area (PSA) ranged between 280–340 Ų

(note: verify consistency with MolSA/SASA ranges).

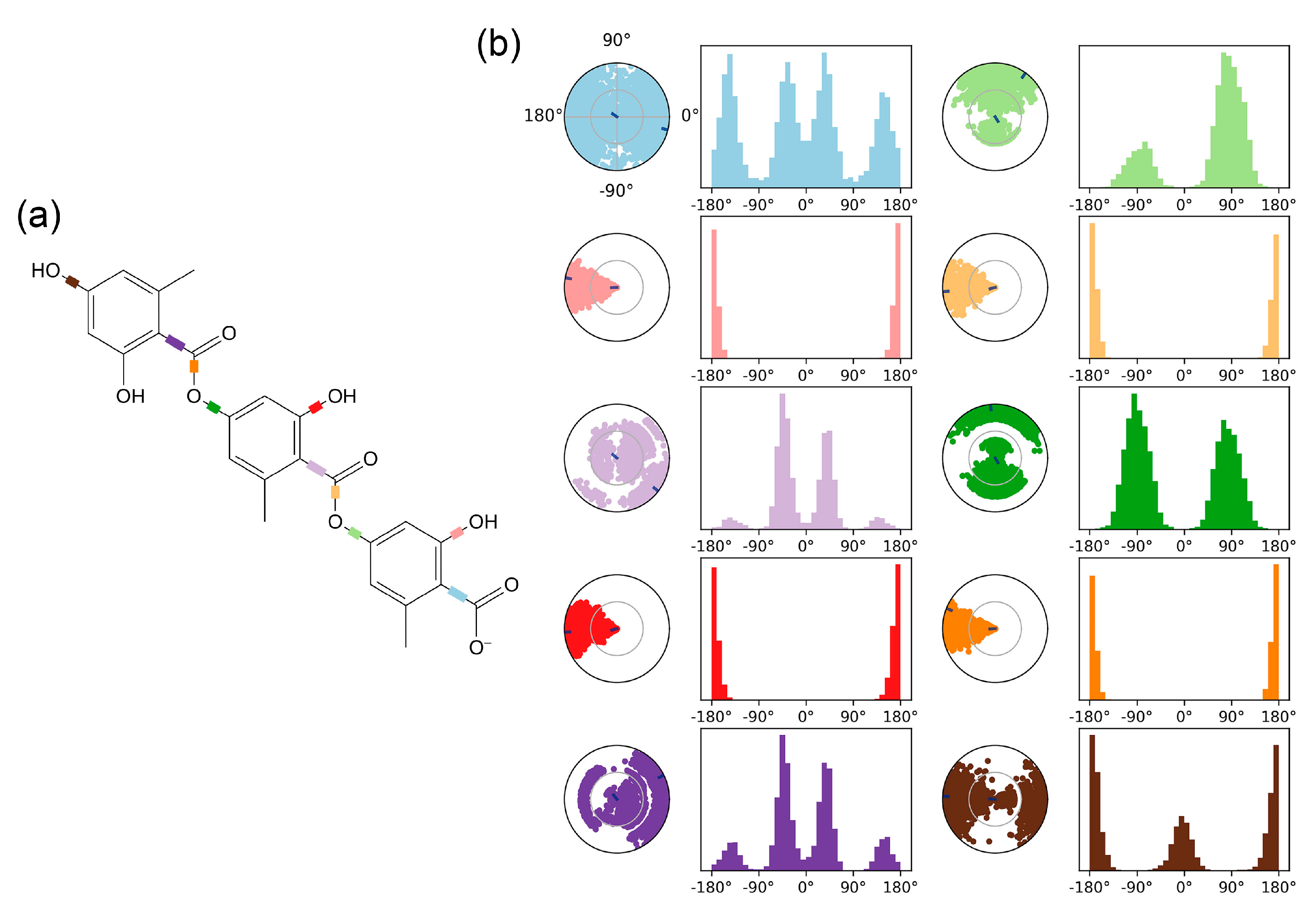

Figure 4 comprehensively characterizes the conformational evolution of gyrophoric acid's ten rotatable bonds (RBs) within the Aβ complex throughout the 100-ns simulation.

Figure 4a shows a 2D schematic of the ligand with color-coded RBs. Each RB’s torsion (

Figure 4b) is accompanied by a dial plot and a bar graph in the same color. The ligand torsion analysis flexibility patterns: RB1 (blue), RB3 (light purple) and RB5 (dark purple) exhibit broad angular sampling (0°-360°), while RB6 (light green) and RB8 (dark green) exhibit angular sampling (0°-150° and 240°-300°) with bimodal probability distributions, indicating multi-stable states. In contrast, RB2 (pink), RB4 (red), RB7 (yellow) and RB9 (orange) maintain rigid torsional confinement at 180° ± 30° (88% occupancy), while RB10 (brown) show moderate flexibility within 180° ± 30° and 0° ± 60° ° ranges respectively. This heterogeneity in rotational freedom – quantified through probability density histograms – correlates with steric constraints imposed by Aβ's binding pocket, where rigid bonds (RB2/RB4/RB7/RB9) anchor the ligand core while flexible termini (RB3/RB5/RB6/RB8) facilitate adaptive interactions.

2.3. Drug-Likeness Prediction

Drug-likeness evaluates the molecular and structural similarity of compounds to known pharmaceuticals, which requires balanced assessment of hydrophobicity, electronic distribution, hydrogen bonding, molecular weight, pharmacophoric groups, bioavailability, reactivity, toxicity, and metabolic stability [

20]. Lipinski's rule of five (RO5) is widely used to predict the absorption/permeation; violations typically indicate suboptimal bioavailability. SwissADME analysis [

21] confirms gyrophoric acid is fully complied with RO5 parameters, suggesting favorable absorption, positioning the acid as a viable lead compound. Pharmacokinetic profiling further indicates a high gastrointestinal absorption. Additional filters, including PAINS structural alerts in identifying instability/toxicity risks [

22,

23] and synthetic accessibility (SA) scoring, have been applied to assess the reactivity and synthetic feasibility.

2.4. ADME Properties

A comprehensive understanding of pharmacology and toxicology is essential to advance drug development. Such knowledge could reduce development timelines and enhance success rates. ADMET is frequently used to evaluate the properties of a substance. ADMET simulations of gyrophoric acid revealed moderate oral absorption potential (PHOA: 48.5–57.3%) and favourable human serum albumin binding (QPlogKhsa: -0.69 to 0.35), aligning with pharmacokinetic safety thresholds (

Table 1). The compound exhibited molecular weights (372.3–468.4 Da) and solvent-accessible surface areas (SASA: 525.8–763.1 Ų) within the drug-like ranges. Gyrophoric acid displayed the highest polar surface area (PISA: 224.7 Ų) and molecular volume (1363.6 ų), correlating with its larger structure. Despite suboptimal PHOA scores (<80%), the metabolites’ moderate absorption profiles, combining with low risks of excessive albumin binding (QPlogKhsa within -1.5–1.5), suggest potential systemic bioavailability. These properties, paired with their previously reported Aβ peptide affinity, position gyrophoric acid as viable candidates for further optimization, particularly for peripheral therapeutic applications.

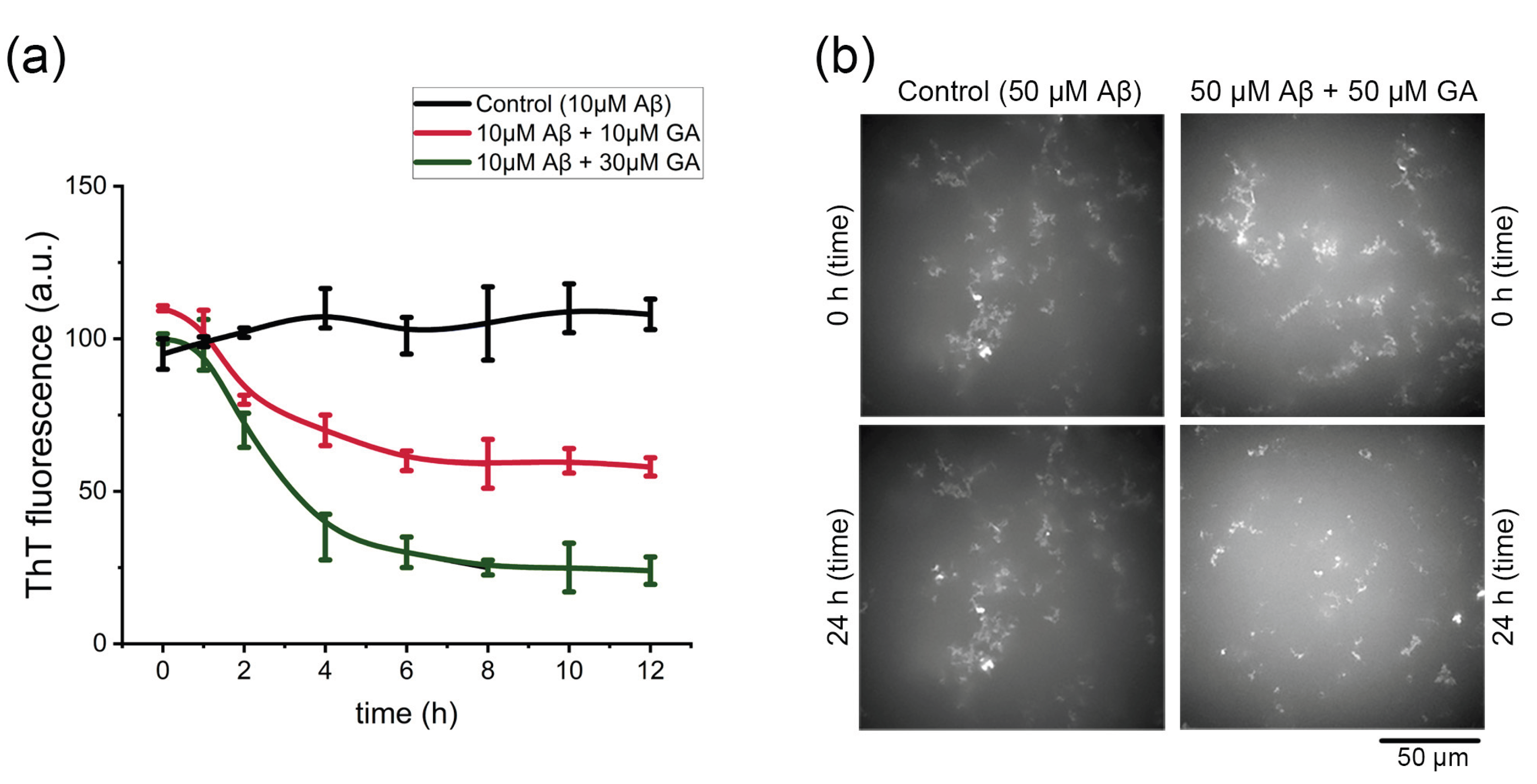

2.5. Gyrophoric Acid Disassemble Aβ42 Fibrils

The deposition of mature Aβ42 fibrils in the brain contributes to neuronal death, and the toxic oligomers are often generated through secondary nucleation catalyzed by existing fibrils [

24]. To investigate whether gyrophoric acid disrupting these fibrils, we monitored Aβ42 aggregate structure using the assays of

in vitro ThT fluorescence and confocal microscopy. ThT analysis (

Figure 5a) revealed that the untreated Aβ42 fibrils remained stable over time. In contrast, the co-treatment with gyrophoric acid induced a dose-dependent disassembly of Aβ42 fibrils. This disassembly reached maximal efficacy within 5 hours and remained stable thereafter.

To further characterize the disaggregation effect of gyrophoric acid in real-time, we performed confocal microscopy on freshly dissolved Aβ42 fibrils incubated with or without gyrophoric acid. After 24 hours in PBS at room temperature, the control fibrils (50 µM Aβ42) exhibited minimal structural change (

Figure 5b, from

Supplementary Video S1). Conversely, the fibrils co-treated with gyrophoric acid (50 µM Aβ42 + 50 µM gyrophoric acid) displayed significant disassembly compared to the initial state (0 hour). Time-lapse imaging captured hourly from 0 to 24 hours demonstrated that gyrophoric acid treatment markedly reduced the number of larger aggregates, as compared to the control, indicating the dissolution (

Video S1).

3. Discussion

Our integrated analyses establish gyrophoric acid—a characteristic lichen depside [

25]—as a dual-action inhibitor of Aβ42 aggregation, operating through distinct structural mechanisms. Thus, lichen-derived depsides represent a pharmacologically rich yet underexplored class of natural products. Their rigid aromatic scaffolds and high phenolic content enable unique biomolecular interactions, providing exceptional surface complementarity with amyloidogenic targets that synthetic compounds often fail to achieve.

Computational studies, as described here, resolved gyrophoric acid's paradoxical binding signature by revealing a multi-phase processes driven by entropic burial of hydrophobic side chains at key residues (Ala42, Val40, Leu17). This conformational selection mechanism, validated through 100-ns molecular dynamics simulations, demonstrated a stable complex formation (RMSD plateau: 1.2–1.8 Å after 70 ns) and induced flexibility in nucleation-critical regions.

Complementing computational predictions and biochemical assays confirmed rapid disassembly of preformed fibrils (<5 hours) triggered by gyrophoric acid, aligning with prior evidence of its neuroprotective effects on cell models [

15]. Our earlier study has identified superior Aβ inhibition by ethanol extracts of

Lobaria containing gyrophoric acid; however, the study lacks the comprehensive

in silico analysis, as being presented here. Furthermore, the time-lapse confocal microscopy here quantitatively confirmed near-complete dissolution of large aggregates within 24 hours.

As a natural depside, gyrophoric acid exhibits favorable drug-like properties consistent with the evolutionary advantages of lichen compounds. Biosynthesis under extreme environmental conditions confers remarkable metabolic stability and low cytotoxicity. ADMET profiling indicates low hepatotoxicity and minimal CYP450 inhibition. However, high polar surface area (224.7 Ų) suggests limited BBB permeability of gyrophoric acid. This challenge reflects a broader limitation for lichen-derived polyphenols, where high molecular weight often compromises BBB penetration. Nevertheless, the exceptional target stabilization (ΔG: -27.3 kcal/mol) and oxidative resilience offer compensatory advantages of these polyphenols.

Gyrophoric acid occurs in several lichen genera, e.g.,

Umbilicaria,

Lobaria,

Parmotrema,

Hypotrachyna, and which exhibits strong anti-microbial, antioxidant, and anti-cancer properties [

13,

14,

15,

26]. Traditional usage of lichen is still persistence. In the Himalayas regions, lichen is being consumed as food and/or medicine. Growing domestic tourism has spurred market demand for the health-promoting lichen products, raising concerns about over-harvesting due to low productivity. Concurrently, there is increasing interest in lichens as sources of innovative pharmacologically active compounds, particularly depsides and depsidones, e.g., gyrophoric acid, fumarprotocetraric acid, and lobaric acid, having known activities of anti-bacterial, anti-inflammatory, and cytotoxicity [

26]. Our innovative, first-of-its-kind research methodology provides a new direction in studying lichen-derived natural products.

Positioned as a structurally novel lead compound, gyrophoric acid exemplifies the untapped potential of lichen symbionts in drug discovery for neurodegenerative diseases. Future work should prioritize: (i) in vivo validation; (ii) rational design of derivatives; and (iii) formulation strategies. Critically, lichen chemo-diversity offers diverse scaffolds (depsidones, dibenzofurans) with modified ring topologies that could enhance BBB permeability while retaining the anti-aggregation efficacy. The systematic screening of lichen metabolite libraries is needed to identify analogs with optimized pharmacokinetic profiles, leveraging co-evolutionary adaptations that confer both target specificity and environmental resilience.

4. Conclusions

This study establishes gyrophoric acid as a dual-action anti-amyloid agent capable of disassembling mature fibrils through a unique hydrophobic-driven mechanism. Computational resolution of its binding paradox (weak docking affinity vs. strong MM-GBSA stabilization [-27.3 kcal/mol]) revealed entropic burial at key residues (Ala42, Val40, Leu17). This was further validated by MD simulations demonstrating complex stability (RMSD: 1.2–1.8 Å) and enhanced fibril flexibility. Experimentally, gyrophoric acid showed rapid fibril dissolution (<5 hours, ThT/confocal microscopy), as well as its dose-dependent efficacy. Gyrophoric acid exhibits favorable ADMET properties and complies with Lipinski's rules [

27]. The integration of computational and experimental approaches is essential to advance gyrophoric acid as a potential anti-Alzheimer's therapeutic, paving the way for novel strategies against this disease.

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Preparation of Aβ Fibrils

Synthetic Aβ42 powder (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) was dissolved in 100% hexafluoro-isopropanol (HFIP) at 1 mM to disrupt pre-existing aggregates. After sonication (20 min, 25°C), the monomer solution was aliquoted, dried overnight in a fume hood to evaporate HFIP, and stored at −20°C. For fibril formation, the peptide film was resuspended in 20 μL DMSO and diluted in 10 mM HCl to 100 μM Aβ42. The solution was incubated at 37 °C for 6 days to generate mature fibrils.

5.2. Thioflavin T (ThT) Fluorescence Assay

ThT fluorescence assay was generated following the method described in a previous report [

15]. Briefly, Aβ42 fibrils (10 μM), aged for 6 days, were incubated with or without gyrophoric acid at 37 °C for 5 days. The ThT fluorescence was measured every two hours of 12 hours totally, in a 96-well black plate at excitation and emission wavelengths of 435 and 488 nm, respectively.

5.3. Confocal Microscopy Real-Time Measurement

Disaggregation kinetics were monitored using an Olympus IX73 confocal microscope (Tokyo, Japan) with a 60× objective. Samples (200 μL) included: control (50 μM Aβ42 fibrils) and gyrophoric acid treatment (50 μM Aβ42 fibrils + 50 μM gyrophoric acid) in PBS. Samples were deposited on glass-bottom dishes (10-mm diameter) and imaged hourly for 24 hours at room temperature. Images were acquired with Micro-Manager software and processed for quantitative analysis.

5.4. In Silico Analysis

The crystal structure of Aβ42 was retrieved from the largest structure repository Protein Data Bank (PDB) having PDB-ID 2BEG (

https://www.rcsb.org/structure/2BEG). The obtained protein structure was pre-processed using the Protein Preparation Wizard module in the Schrödinger Suite. This included the following steps: Structural optimization (e.g., correcting bond orders, adding missing hydrogen atoms); Regeneration of the native ligand’s protonation states at pH 7.4; Hydrogen bond assignment optimization; Energy minimization of the protein structure using the OPLS4 force field; Removal of crystallographic water molecules unrelated to binding. The 2D SDF structure file of the compound (gyrophoric acid) was processed using the LigPrep module in Schrödinger to generate all possible 3D chiral conformations. Ionization states were predicted at pH 7.4 ± 2.0, and low-energy stereoisomers were retained for subsequent docking studies. In active site identification, the SiteMap (Schrödinger) was employed to predict potential binding pockets on the Aβ42 peptide. The Receptor Grid Generation module was used to define an enclosing box around the top-ranked binding site identified by SiteMap, ensuring complete coverage of the predicted active region. In molecular docking, the prepared ligand (i.e., gyrophoric acid) was docked into the active site of the Aβ42 peptide using the Glide module in XP (Extra Precision) docking mode. Docking scores (expressed as Glide XP GScore) were calculated, where lower scores indicate stronger binding affinity and higher stability, due to the reduced binding free energy.

5.5. MM-GBSA Binding Free Energy Calculaions

The binding interactions between gyrophoric acid and the Aβ42 peptide were further evaluated using MM-GBSA (Molecular Mechanics/Generalized Born Surface Area) calculations. The Prime MM-GBSA module in Schrödinger was utilized to estimate the binding free energy (ΔGbind), where lower ΔGbind values correlated with enhanced ligand-protein binding stability.

5.6. MD Simulation

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were performed using Desmond (OPLS4 force field) to optimize compound-protein binding. The protein-ligand complex was solvated in a cubic water box (SPC/E model), neutralized with 0.15 M NaCl, and energy-minimized via steepest descent (50,000 steps). Systems underwent restrained NVT/NPT equilibration (50,000 steps; 300 K, 1 bar), followed by unrestrained 100-ns production runs. Trajectory analysis was conducted in Maestro 13.5.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Video S1: Real-time dissolution in 24h (confocal time-lapse) of two samples, control (50 µM Aβ42) comparing with gyrophoric acid (50 µM) disassembles Aβ42 (50 µM) fibrils.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.W.K.T. and M.Y.; methodology, M.Y., H.H. and Q.X.; software, M.Y. and H.H.; validation, M.Y.; formal analysis, M.Y.; investigation, J.G., F.E.; resources, Q.W.S.L., K.W.L. and T.T.X.D.; data curation, M.Y. and H.H.; writing—original draft preparation, M.Y.; writing—review and editing, K.W.K.T.; visualization, M.Y.; supervision, K.W.K.T. and Q.X.; project administration, K.W.K.T. and T.T.X.D.; funding acquisition, K.W.K.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding This work is supported by Hong Kong Research Grants Council Hong Kong (GRF 16100921); Zhongshan Municipal Bureau of Science and Technology (2019AG035); Guangzhou Science and Technology Committee Research Grant (GZSTI16SC02; GZSTI17SC02); GBA Institute of Collaborate Innovation (GICI022); The Key-Area Research and Development Program of Guangdong Province (2020B1111110006); Special project of Foshan University of Science and Technology in 2019 (FSUST19-SRI10); Hong Kong RGC Theme based Research Scheme (T13-605/18-W); Hong Kong Innovation Technology Fund (ITS/500/18FP; MHP/004/21; GHP/016/21SZ; ITCPD/17-9; ITC-CNERC14SC01); TUYF19SC02, PD18SC01 and HMRF18SC06; HMRF20SC07, AFD20SC01; Shenzhen Science and Technology Innovation Committee (ZDSYS201707281432317).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AD |

Alzheimer’s disease |

| Aβ |

Amyloid-beta |

| ThT |

Thioflavin T |

| MD |

Molecular dynamics |

| ADMET |

Absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, toxicity |

| AChE |

Acetylcholinesterase |

| MM-GBSA |

Molecular Mechanics-Generalized Born Surface Area |

| RMSD |

Root-mean-square deviation |

References

- Blass, J.P. Alzheimer’s disease and Alzheimer’s dementia: distinct but overlapping entities. Neurobiol. Aging 2002, 23, 1077–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohrabi, H.R.; Weinborn, M. Cognitive impairments in Alzheimer’s disease and other neurodegenerative diseases. In Neurodegeneration and Alzheimer’s Disease. Wiley, 2019; pp. 267–290. [CrossRef]

- DeTure, M.A.; Dickson, D.W. The neuropathological diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 2019, 14, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, H.; Li, R.; Sterling, K.; Song, W. Amyloid β-based therapy for Alzheimer’s disease: challenges, successes and future. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, J.; Feldman, H.H.; Scheltens, P. The “rights” of precision drug development for Alzheimer’s disease. Alz Res. Ther. 2019, 11, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gheidari, D.; Bayat, M. Current treads of targeted nanoparticulate carriers for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. In Nanomedical Drug Delivery for Neurodegenerative Diseases. Elsevier, 2022; pp. 17–39. [CrossRef]

- Korczyn, A.D.; Grinberg, L.T. Is Alzheimer disease a disease? Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2024, 20, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; An, N.; Wei, Y.; Wang, L.; Tian, C.; Yuan, M.; Sun, Y.; Xing, Y.; Gao, Y. Oxidative stress-mediated blood-brain barrier (BBB) disruption in neurological diseases. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 1, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamontagne-Kam, D.; Ulfat, A.K.; Hervé, V.; Vu, T.-M.; Brouillette, J. Implication of tau propagation on neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Neuro. Sci. 2023, 17, 1662–453X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqubal, A.; Rahman, S.O.; Ahmed, M.; Bansal, P.; Haider, M.R.; Iqubal, M.K.; Najmi, A.K.; Pottoo, F.H.; Haque, S.E. Current quest in natural bioactive compounds for Alzheimer’s disease: multi-targeted-designed-ligand based approach with Preclinical and Clinical Based Evidence. Curr. Drug Targets 2021, 22, 685–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagano, K.; Tomaselli, S.; Molinari, H.; Ragona, L. Natural compounds as inhibitors of Aβ peptide aggregation: chemical requirements and molecular mechanisms. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, M.; Bagheri, L.; Badreldin, A.; Fatehi, P.; Pakzad, L.; Suntres, Z.; van Wijnen, A.J. Biological effects of gyrophoric acid and other lichen derived metabolites, on cell proliferation, apoptosis and cell signaling pathways. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 2022, 351, 109768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goga, M.; Kello, M.; Vilkova, M.; Petrova, K.; Backor, M.; Adlassnig, W.; Lang, I. Oxidative stress mediated by gyrophoric acid from the lichen Umbilicaria hirsuta affected apoptosis and stress/survival pathways in HeLa cells. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2019, 19, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbanska,N. ; Karasova, M.; Jendzelovska, Z.; Majerník, M.; Kolesarova, M.; Kecsey, D.; Jendzelovsky, R.; Bohus, P.; Kiskova, T. Gyrophoric Acid, a secondary metabolite of lichens, exhibits antidepressant and anxiolytic activity in vivo in wistar rats. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Yan, C.; Ospondpant, D.; Wang, L.; Lin, S.; Tang, W.L.; Dong, T.T.; Tong, P.; Xu, Q.; Tsim, K.W.K. Unveiling the therapeutic potential of Lobaria extract and its depsides/depsidones in combatting Aβ42 peptides aggregation and neurotoxicity in Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1426569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, L.; Ha-Duong, T. Exploring the Alzheimer amyloid-β peptide conformational ensemble: a review of molecular dynamics approaches. Peptides 2015, 69, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sucharitha, P.; Ramesh Reddy, K.; Satyanarayana, S.V.; Garg, T. Absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity assessment of drugs using computational tools. In Computational Approaches for Novel Therapeutic and Diagnostic Designing to Mitigate SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Elsevier, 2022; pp. 335–355. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, L.L.G.; Andricopulo, A.D. ADMET modeling approaches in drug discovery. Drug Discov. Today 2019, 24, 1157–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raskatov, J.A. Conformational selection as the driving force of amyloid β chiral inactivation. ChemBioChem. 2020, 21, 2945–2949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoodi, N.; Bayat, M.; Gheidari, D.; Sadeghian, Z. In silico evaluation of cis-dihydroxy-indeno[1,2-d]imidazolones as inhibitors of glycogen synthase kinase-3: synthesis, molecular docking, physicochemical data, ADMET, MD simulation, and DFT calculations. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 2024, 28, 101894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, R. Theoretical studies on the molecular properties, toxicity, and biological efficacy of 21 new chemical entities. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 24891–24901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capuzzi, S.J.; Muratov, E.N.; Tropsha, A. Phantom PAINS: problems with the utility of alerts for pan-assay Iinterference compounds. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2017, 57, 417–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, S.I.A.; Linse, S.; Luheshi, L.M.; Hellstrand, E.; White, D.A.; Rajah, L.; Otzen, D.E.; Vendruscolo, M.; Dobson, C.M.; Knowles, T.P.J. Proliferation of amyloid-β42 aggregates occurs through a secondary nucleation mechanism. PNAS 2013, 110, 9758–9763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakur, M.; Bhardwaj, S.; Kumar, V.; Rodrigo-Comino, J. Lichens as effective bioindicators for monitoring environmental changes: a comprehensive review. Total Environ. Adv. 2023, 9, 200085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urena-Vacas, I. , Gonzalez-Burgos, E., Divakar, P.K., and Gomez-Serranillos, M.P. Lichen depsidones with biological interest. Planta Medica. 2021, 88, 855–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipinski, C.A. Lead- and drug-like compounds: the rule-of-five revolution. Drug Discov. Today Technol. 2004, 1, 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

(a) XP high accuracy 2D molecular docking (Schrodinger's maestro 13.5 software) of gyrophoric acid into the active site of Aβ peptide, docking scores -1.121 and binding free energies -27.3 kcal/mol indicate gyrophoric acid binding to Aβ peptide is low, but once bound, the interaction is relatively stable. (b) 3D binding’s mode of gyrophoric acid into the active site of Aβ peptide, gyrophoric acid binds to the surface of the active pocket of Aβ peptide. The residues Ala42 and Val40 on chain E, Val40 and Ala42 on chain C, and Ala42 on chain B contribute to the hydrophobic interactions with gyrophoric acid. Gyrophoric acid interacts with Aβ peptide through non-covalent bonds.

Figure 1.

(a) XP high accuracy 2D molecular docking (Schrodinger's maestro 13.5 software) of gyrophoric acid into the active site of Aβ peptide, docking scores -1.121 and binding free energies -27.3 kcal/mol indicate gyrophoric acid binding to Aβ peptide is low, but once bound, the interaction is relatively stable. (b) 3D binding’s mode of gyrophoric acid into the active site of Aβ peptide, gyrophoric acid binds to the surface of the active pocket of Aβ peptide. The residues Ala42 and Val40 on chain E, Val40 and Ala42 on chain C, and Ala42 on chain B contribute to the hydrophobic interactions with gyrophoric acid. Gyrophoric acid interacts with Aβ peptide through non-covalent bonds.

Figure 2.

(a) RMSD values for gyrophoric acid – Aβ peptide complex during MD simulation, the gyrophoric acid and Aβ complex remains relatively stable after 70 ns of molecular dynamics trajectory (b) RMSF plot for Cα of Aβ peptide chain residues with gyrophoric acid. Protein residues that interact with the ligand are marked with green-colored vertical bars. (c) gyrophoric acid-Aβ peptide interactions during MD simulation. Protein-ligand interactions were monitored throughout the simulation and categorized into four types: hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, ionic bridges, and water bridges. The key amino acid residues contributing to the binding of GA to the Aβ peptide protein include Chain A Leu17, Chain A Val40, Chain A Ala42, Chain B Leu17, Chain C Leu17, and Chain E Ala42. The dominant interactions observed were water bridges, hydrophobic contacts, and hydrogen bonds. (d) Time-dependent interactions between gyrophoric acid and specific amino acid residues of Aβ peptide across the simulation trajectory. The changes over time in the interactions between gyrophoric acid and specific amino acids of Aβ. The amino acid residues, Leu17, Val40, and Ala42 on chain A, Leu17 on chain B, Leu17 on chain C, and Ala42 on chain E, have multiple contacts with the ligand (represented by darker orange coloration).

Figure 2.

(a) RMSD values for gyrophoric acid – Aβ peptide complex during MD simulation, the gyrophoric acid and Aβ complex remains relatively stable after 70 ns of molecular dynamics trajectory (b) RMSF plot for Cα of Aβ peptide chain residues with gyrophoric acid. Protein residues that interact with the ligand are marked with green-colored vertical bars. (c) gyrophoric acid-Aβ peptide interactions during MD simulation. Protein-ligand interactions were monitored throughout the simulation and categorized into four types: hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, ionic bridges, and water bridges. The key amino acid residues contributing to the binding of GA to the Aβ peptide protein include Chain A Leu17, Chain A Val40, Chain A Ala42, Chain B Leu17, Chain C Leu17, and Chain E Ala42. The dominant interactions observed were water bridges, hydrophobic contacts, and hydrogen bonds. (d) Time-dependent interactions between gyrophoric acid and specific amino acid residues of Aβ peptide across the simulation trajectory. The changes over time in the interactions between gyrophoric acid and specific amino acids of Aβ. The amino acid residues, Leu17, Val40, and Ala42 on chain A, Leu17 on chain B, Leu17 on chain C, and Ala42 on chain E, have multiple contacts with the ligand (represented by darker orange coloration).

Figure 3.

(a) Detailed schematic of the interactions between the compound and protein residues, showing interactions that occurred for more than 10.0% of the simulation time (i.e., interaction time exceeding 10 ns in a 100 ns simulation). Gyrophoric acid directly forms hydrogen bonds with chain A residue Ala42 (17%), chain A residue Val40 (17%), and chain E residue Ala42 (13%), while forming water-mediated bridges with chain E residue ALA42 (11%) and chain C residue Leu17 (16%). (b) Properties of the gyrophoric acid ligand during MD simulation. Ligand RMSD: root means square deviation of a ligand with respect to the reference conformation (typically the first frame is used as the reference, and it is regarded as time t=0). Radius of Gyration (rGyr): Measures the 'extendedness' of a ligand and is equivalent to its principal moment of inertia. Intramolecular hydrogen bonds (intraHB): Number of internal hydrogen bonds (HB) within a ligand molecule. Molecular surface area (MolSA): Molecular surface calculation with 1.4 Å probe radius. This value is equivalent to the van der Waals surface area. Solvent accessible surface area (SASA): Surface area of a molecule accessible by a water molecule. Polar surface area (PSA): Solvent accessible surface area in a molecule contributed only by oxygen and nitrogen atoms.

Figure 3.

(a) Detailed schematic of the interactions between the compound and protein residues, showing interactions that occurred for more than 10.0% of the simulation time (i.e., interaction time exceeding 10 ns in a 100 ns simulation). Gyrophoric acid directly forms hydrogen bonds with chain A residue Ala42 (17%), chain A residue Val40 (17%), and chain E residue Ala42 (13%), while forming water-mediated bridges with chain E residue ALA42 (11%) and chain C residue Leu17 (16%). (b) Properties of the gyrophoric acid ligand during MD simulation. Ligand RMSD: root means square deviation of a ligand with respect to the reference conformation (typically the first frame is used as the reference, and it is regarded as time t=0). Radius of Gyration (rGyr): Measures the 'extendedness' of a ligand and is equivalent to its principal moment of inertia. Intramolecular hydrogen bonds (intraHB): Number of internal hydrogen bonds (HB) within a ligand molecule. Molecular surface area (MolSA): Molecular surface calculation with 1.4 Å probe radius. This value is equivalent to the van der Waals surface area. Solvent accessible surface area (SASA): Surface area of a molecule accessible by a water molecule. Polar surface area (PSA): Solvent accessible surface area in a molecule contributed only by oxygen and nitrogen atoms.

Figure 4.

The ligand torsion plot summarizes the conformational evolution of each rotatable bond (RB) of the ligand (gyrophoric acid-Aβ) throughout the simulation trajectory. (a) The left panel shows a 2D schematic of the ligand with color-coded RBs. Each RB’s torsion is accompanied by a dial plot and a bar graph in the same color. (b) The right panel displays the dial (or radial) plot, illustrating the torsional conformations sampled during the entire simulation. The bar graph summarizes the data from the dial plot by showing the probability density of the torsion angles. (RB1: blue, RB2: pink, RB3: light purple, RB4: red, RB5: dark purple, RB6: light green, RB7: yellow, RB8: dark green, RB9: orange, RB10: brown, respectively).

Figure 4.

The ligand torsion plot summarizes the conformational evolution of each rotatable bond (RB) of the ligand (gyrophoric acid-Aβ) throughout the simulation trajectory. (a) The left panel shows a 2D schematic of the ligand with color-coded RBs. Each RB’s torsion is accompanied by a dial plot and a bar graph in the same color. (b) The right panel displays the dial (or radial) plot, illustrating the torsional conformations sampled during the entire simulation. The bar graph summarizes the data from the dial plot by showing the probability density of the torsion angles. (RB1: blue, RB2: pink, RB3: light purple, RB4: red, RB5: dark purple, RB6: light green, RB7: yellow, RB8: dark green, RB9: orange, RB10: brown, respectively).

Figure 5.

Disaggregation effect of gyrophoric acid (GA) against Aβ mature fibrils. (a) The final ThT fluorescence of mature Aβ42 fibrils after 3-day incubation ± GA (10–30 μM). Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 4 per group). (b) Confocal images of control (50 μM Aβ42) and gyrophoric acid-treated (50 μM Aβ42 + 50 μM GA) samples at 0 and 24 hours.

Figure 5.

Disaggregation effect of gyrophoric acid (GA) against Aβ mature fibrils. (a) The final ThT fluorescence of mature Aβ42 fibrils after 3-day incubation ± GA (10–30 μM). Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 4 per group). (b) Confocal images of control (50 μM Aβ42) and gyrophoric acid-treated (50 μM Aβ42 + 50 μM GA) samples at 0 and 24 hours.

Table 1.

ADMET simulation properties of gyrophoric acid.

Table 1.

ADMET simulation properties of gyrophoric acid.

| Property or Descriptor with range or recommended values |

Gyrophoric acid |

Property or Descriptor with range or recommended values |

Gyrophoric acid |

| Mol. Wt (130-725) |

468.416 |

QPlogPo/w (−2.0 – 6.5) |

3.256 |

| SASA (300-1000) |

763.078 |

QPlogS (−6.5 – 0.5) |

-6.041 |

| FOSA (0-750) |

208.919 |

CIQPlogS (−6.5 – 0.5) |

-6.959 |

| FISA (7-330) |

329.438 |

QPlogHERG (concern below −5) |

-4.367 |

| PISA (0-450) |

224.721 |

QPlogBB (−3.0 – 1.2) |

-3.595 |

| Volume (500-2000) |

1363.561 |

QPlogKp (−8.0 – −1.0) |

-5.935 |

| donorHB (0.0 – 6.0) |

2.000 |

IP(eV) (7.9 – 10.5) |

9.524 |

| accptHB (2.0 – 20.0) |

7.000 |

EA(eV) (−0.9 – 1.7) |

0.621 |

| dip^2/V (0.0 – 0.13) |

0.130 |

#metab (1 – 8) |

7 |

| ACxDN^.5/SA (0.0 – 0.05) |

0.013 |

QPlogKhsa (−1.5 – 1.5) |

0.354 |

| glob (0.75 – 0.95) |

0.780 |

HumanOralAbsorption |

1 |

| QPpolrz (13.0 – 70.0) |

44.783 |

PHOA (<25% is poor, >80% is high) |

50.942 |

| QPlogPC16 (4.0 – 18.0) |

15.378 |

QPlogKhsa (-1.5 to 1.5) |

0.354 |

| QPlogPoct (8.0 – 35.0) |

23.996 |

RuleOfFive (maximum is 4) |

4 |

| QPlogPw (4.0 – 45.0) |

13.164 |

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).