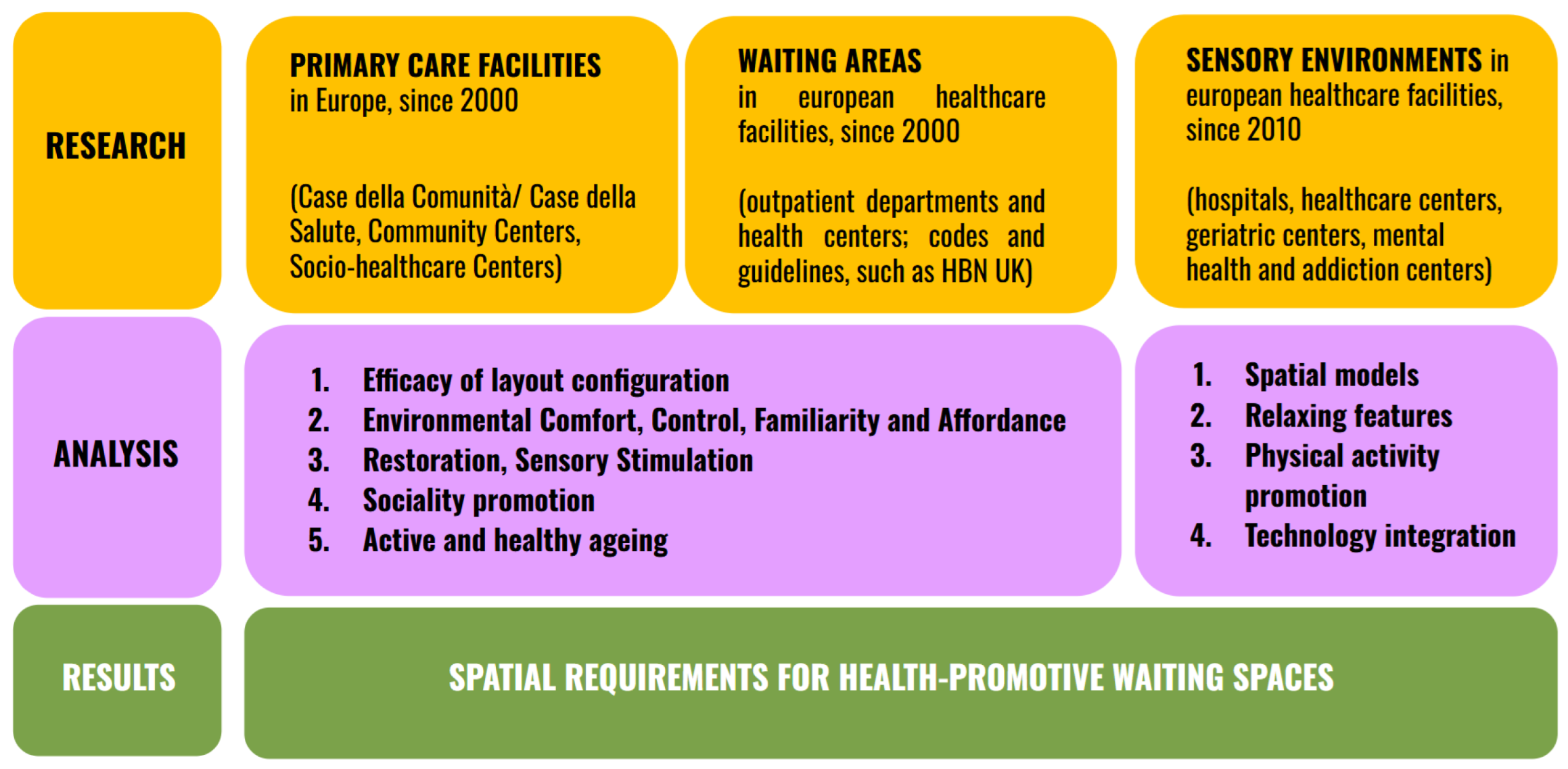

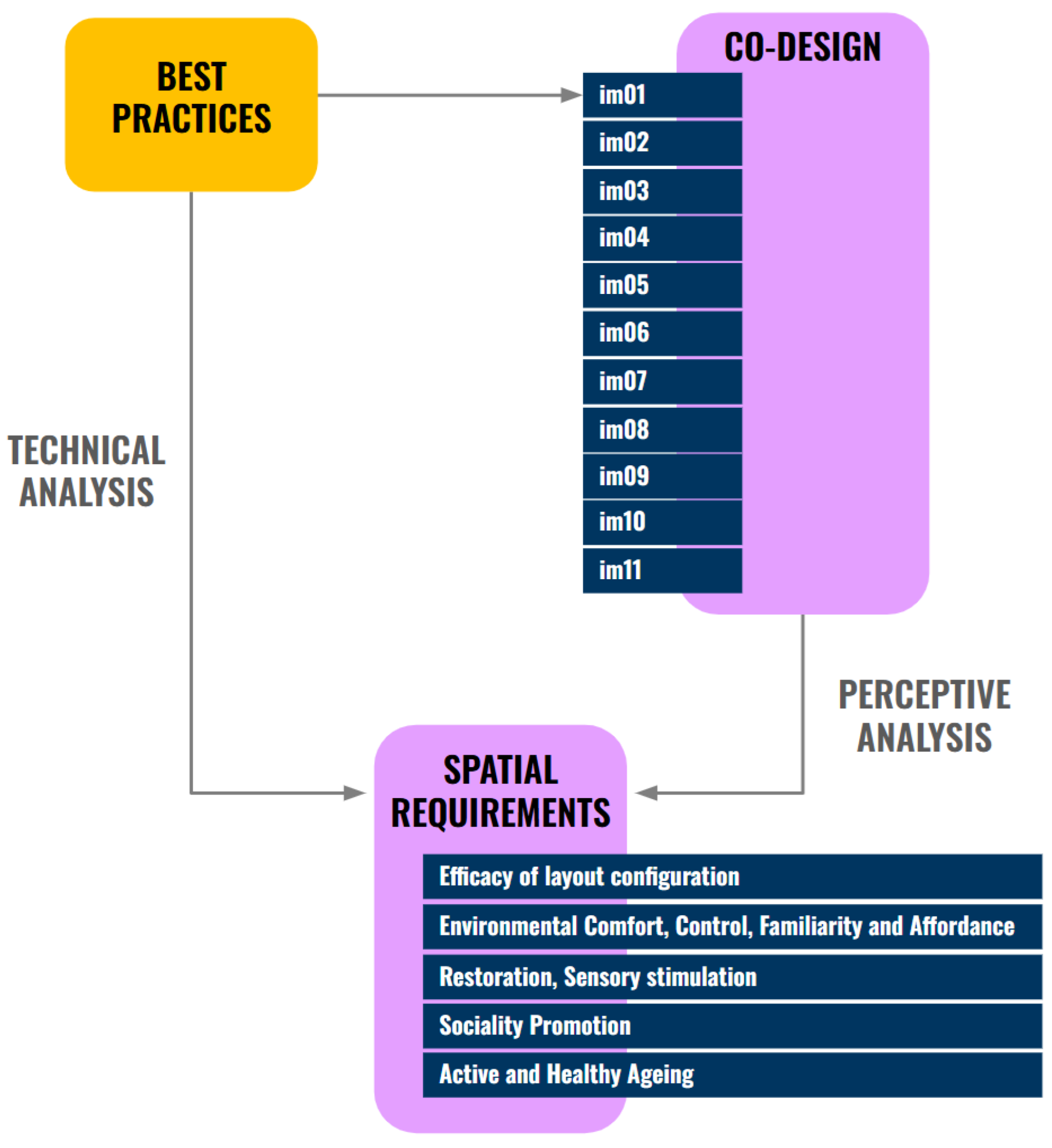

According to the aim of this paper, in this section we present the results of the definition of space requirements for active and healthy waiting space.

Space requirements represent the result of both, technical and perceptive analysis, mixing indications derived by the study of best practices and qualitative responses to the interviews, related to the point of view of patients, caregivers and staff regarding waiting spaces’ models of the technical phase.

3.1. Space Requirements

3.1.1. Efficacy of Layout Configuration

According to the different layouts of the healthcare facilities analysed, we identified 8 different models of waiting spaces based on the configuration layouts (

Table 3).

Waiting areas can be placed directly in the atrium (M01), articulated by spaces with different seats oriented to favour social relations, but also to guarantee privacy, depending on different needs (referring for example to case studies a12, a13 in

Table 1). This area can also be characterized by colours (a12, a16), art or nature, to favour comprehension and recognizability.

Waiting area can be along “the street” (M02), which runs longitudinally through the whole healthcare facility, recreating differentiated waiting corners along the route, like small sitting points. Nature can have an important role in this area, such as creating “green rooms” through flower beds with tall vegetation that divides the spaces (a2), or using flower beds with lower spread plants (a10); as well as art that can be spread along the path, such as artworks, sculptures, lighting systems (a8, a14) or large multi-level walls (a14, a18). Sociality can be supported by furniture, such as seats oriented to look at each other or around a table to encourage relationships; as well as games or art along the route (a10, a14, a17) to share the experience and favour the dialogue. The street can be on a single level, double or triple volume, overlooking the other floors through galleries and raised connections (a8, a17, a18, a20), also creating larger areas of interaction such as a central big square (a18, a20) or smaller ones at the various floors, creating a connection by stairs or slides that lead from one floor to another (a14).

Another recurring typology is represented by waiting spaces built around patios or courtyards (M03), which are suitable to be green (a1, a5, a6, a7, a9, a14, a15), to maintain continuous contact with nature and encourage distraction during the waiting time. Courtyards can be accessible (M04) or not. They can have different shapes and sizes: as an example, long and rectangular spaces allow natural but indirect, non-dazzling light to be given inside, and can provide seats along the openings (a5, a9) in order to maintain a relationship with nature even if not going outside; smaller and more contained spaces, with the same dimensional relationship between waiting and green space, can let the outside in interior spaces and expands the space up (a19), also thanks to big transparent glass openings. When accessible, they can be places to stop and relax on seats in a structured greenery (a7, a14) or in a wild and more natural context (a1, a6); they can have covered spaces to install artworks (a8) or doing different activities, such as yoga, children’s playing, etc. (a15). Green courtyards can represent the core of the structure, also having a function linked to health promotion, physical and mental support activities and sociality (a6, a15).

A different model can be represented by a well-defined waiting space, such as a separate waiting room (M05), independent from the other areas of the healthcare facility, while maintaining visual contact and access control of the relevant healthcare services/spaces. For example, this typology involves the placement of several rooms in different areas of the building, close to the healthcare services/spaces, completely separated and facing outwards to maintain the relationship with the context and the surrounding landscape (a11, a16). These waiting areas can be highlighted by colour to facilitate recognisability, both from inside and outside (a16). They can be closed and contained, to favour privacy and relaxation, supported also by dim light (a11) or other sensory elements. Otherwise, the separation of the space can be less strong, creating a filter (M06), such as glass walls (a13), wooden slats (a13), or a semi-transparent perforated surface (a4), which can let light filter through and maintain the visual relationship with the different areas, also favouring the relationship with other users and the visibility of the entrances to the outpatient area, reducing stress.

The last typology is represented by “the corner” (M07), some waiting points within a larger space, placed along the path or around the courtyards, identified by colour, seating elements (a2, a12, a17) or artworks (a15); as well as niches/pods open in corridors or other public spaces, built into the walls or with an independent structure, identified by colours or materials (a12); as well as furniture to create a point of rest, such as armchairs with higher backrests and sides, placed around the head to promote privacy (a12, a14, a17).

The model M08 is very common in the existing healthcare buildings, but it should be avoided in new designs because of some critical issues such as the lack of privacy, the passage of people, the noise, the lack of space, the difficulty in relating with other people. Anyway, in the Design Guidelines we decided to analyse this model as we are also referring to refurbishment of existing buildings.

The definition of the 8 spatial models (

Table 3) was an important result of the technical analysis which represented the basis of discussion in the interviews with the staff, to understand their opinion about the impact of configuration on people’s perception of the waiting experience in the different models. The staff itself expresses the importance of “the organization of spaces to enhance the perceived quality of the facility and consequently of the healthcare service, as well as reducing stress and fostering relationships of patients/caregivers with the staff”. A clear and comprehensible layout is therefore very important in the design.

The most debated point, which determines the different layouts of waiting spaces, concerns the view of the door of the healthcare service from the waiting area: on the one hand, seeing the door allows for monitoring and can therefore reassure the patient, for example, that they won’t miss their turn; on the other hand, it can generate anxiety since they are never able to distract themselves and relax, maintaining a constant state of stress. It is perhaps more important to know you are in the right place (and therefore provide appropriate information, both through spatial layouts and signage), to know that one of the staff will call you, or at least to have access to call systems for the visit/exam. In this sense, the waiting room can also be a completely separate room, which has the advantage of being a private place where patients/caregivers can relax and distract themselves.

It’s highly recommended to have a secluded area away from the main corridors to promote calm and privacy during waiting, while avoiding waiting directly in the corridors, as “it’s a transit point and therefore one can see various health, pathological, and social situations,” which can generate anxiety. This also promotes privacy, not looking at the doors during waiting and ensuring visual and acoustic privacy.

The configuration of waiting spaces should be as varied as possible to meet the different needs of users. For example, some people prefer seclusion (such as a seating area in an alcove), while others prefer a shared space where they can more easily pass the time, talk, and interact with others. The waiting area should foster relationships between patients or caregivers, for example by having a connected coffee or tea area, which promotes greater conviviality. Open large space is also suitable for people with dementia or Parkinson, where they can move freely and in safety. In any case, it is important to be able to find privacy in an open space, to recreate a sort of intimacy between the caregiver and the patient, to have the opportunity to read, for example, and to distract oneself, reducing the feeling of waiting time.

Outdoor waiting is a very interesting model, but it is affected by weather conditions, so at least some coverage is required, and obviously it cannot be the only waiting area. It’s beneficial to have space for walking while waiting, to “promote active aging,” or an area dedicated to “sensory stimulation”. “This could also be a corridor/greenhouse with plants inside”. In any case, it’s important that the green area be adjacent to the waiting room to maintain a connection.

Greenery can also be imagined within waiting areas, to “mentally escape and thus think less about what patients are about to do” and to create “privacy” between seats. However, it’s important to have big windows to allow proper oxygenation, that there be no flowers, which can cause allergies and infections, and that maintenance and cleaning are guaranteed. The sight of greenery already positively influences the waiting experience.

We discussed the same topics with patients and caregivers.

Regarding the layout, we discussed with users first of all the importance of seeing the door. This is a rather controversial topic, with the majority saying they are indifferent or, on the contrary, prefer not to see it, but with a small difference. Caregivers show a similar result, with the majority being indifferent or preferring not to see the door. People who ask to see the door are linked to the anxiety of “not seeing what’s happening,” or “losing their turn,” checking they “didn’t make a mistake,” or “making the visit seem closer”; in general, a sense of control. Many say that if they can’t see the door, a display or call support is necessary. However, the situation is different for caregivers who prefer to maintain eye contact to ensure they can intervene if needed. Those who prefer not to see the door are often linked to a situation of anxiety or distress caused by constantly seeing the door and constantly waiting for the other person to come out before it’s their turn; furthermore, not seeing the door makes it easier to distract oneself in a positive way, for example by “looking at a beautiful view”.

According to this idea, the use of a filter between the waiting area and the outpatient doors seems to be an effective solution. This allows for monitoring, but also ensures a more private waiting experience. On the other hand, the filter used should be pleasant and not too restrictive, like “sticks” or a “barbed wire fence,” which makes the area feel “like a prison”.

Many, however, report the importance of waiting in a large, open space. For this reason, many users dislike a separate waiting room, as it often feels small and cramped. This can be addressed by a large window overlooking the outside, which is always appreciated for its view, natural light, and connection to the outside world. Those who prefer to see the door view will obviously find a separate room unpopular, especially if it’s far from the outpatient area, but this problem can be addressed for many with a display or call system. The problem of small spaces is often associated with the potential for crowding, which is considered very negative. Anyway, there are some who prefer this model because it’s separate, quieter, and more secluded.

The connection with the outdoors, and in particular the view of greenery, is greatly appreciated by virtually all users. In this sense, many of them would gladly wait outside to “get some fresh air,” especially if there are many people and it’s hot, and to pass the time: “It’s more distracting, you can look around,” “you can completely disconnect from the inside.” Here, too, clearly, displays and call devices are necessary. Many prefer a situation where the outdoor space is adjacent to the waiting room, to maintain visual control. Finally, many report the problem of waiting outside in adverse weather conditions, such as rain, cold in winter, or hot in summer. They suggest adding seating, activity equipment, children’s games, fountains, social spaces, or connected services such as a cafeteria outside. The advantages of waiting outside for those with children were also highlighted, as it allows for easier entertainment during the wait.

3.1.2. Environmental Comfort, Control, Familiarity and Affordance

The quality of light (natural and artificial) and ventilation are the basis of the design of a healthcare facility that creates comfort for the patient. Natural ventilation can be favoured by the use of courtyards and patios, but also through openings on the ceiling, for example in pitched roofs (a7). Acoustic is also the basis of the comfort of healthcare buildings. For example, it should be favoured the use of acoustic false ceilings in waiting areas where noises and reverberation can occur (a5, a11).

The design of spaces, openings and facade can be different according to solar orientation to promote comfort and energy saving (a5, a6, a11, a16). The use of large openings or transparent glass surfaces, even on the roof, should be favoured, especially in public areas (a1, a2, a4 , a10, a12, a13, a14, a15, a16, a17) to promote natural light and relation with the landscape. The system of shading for the façade can regulate the amount of incoming light and avoid glare and overheating phenomena (a5). There can also be an internal filter to regulate natural light and allow visibility, favouring comfort and privacy (a4). Moreover, the indirect light entering from internal green courtyards allows light to spread in a more comfortable way (a8, a9, a14).

Artificial lighting also plays an important role in the quality and comfort of the internal spaces of healthcare facilities. Lighting fixtures that are not dazzling and give a warm, welcoming and familiar atmosphere are to be favoured, guaranteeing a bright, comfortable and welcoming environment in any weather condition (a8, a13, a17). They can also be elements that, integrated into the artworks, favour interaction and navigation (a8).

The choice of colours and materials can also help spread light in a warm and welcoming way (a15), such as the use of wood, whereby the light is reflected and acquires a warm tone that offers softer contrasts ( A15). The use of warm and neutral colours should be encouraged (a3, a5, a8, a12, a16), which, together with the use of natural materials, can inspire a sense of familiarity (a8). Colours can liven up the environment and give a bright and positive tone, especially at the entrance and along the paths (a12, a16), promoting the idea of a welcoming and friendly place. For example, the use of yellow can promote a sense of positivity (a12, a16); the use of green and other natural shades can create a warm, bright and welcoming atmosphere (a17); cold colours are more functional for staff spaces, to create a stimulating and attractive work environment (a17). Then, the use of colour can also promote recognisability, comprehension and navigation. The use of wood is suitable (a1, a4, a5, a6, a7, a13, a14) to promote warmth, welcoming, familiarity and the sense of belonging to the territory, favouring the use of local and natural materials (a5, a6, a7). It also reminds of external nature and provides a positive associative effect, evoking positive memories, calm and well-being (a15). Then, it can be used in flooring also to identify waiting areas, to differentiate and highlight them compared to the paths, and to make them more domestic and comfortable (a14). Moreover, it can be used on the facade, reflecting from the outside of the building the desire to provide the city with a healthy and environmentally friendly building (a7) and creating a warm character also on the outside, encouraging people to enter (a15). The use of local materials is also valid for the use of stone and the integration with the surrounding context, therefore favouring identity and recognisability (a11). The same type of integration can also be favoured by the size of the building and its volumes, integrating with the surrounding urban landscape, while making itself recognizable through the use of materials and colours (a18, a19). In fact, the use of different materials on the façade completely changes the appearance from the outside and the relationship between the interior and the surrounding landscape (urban and natural), choosing to differ or to create a dialogue with the context (a19).

The familiarity of spaces, as well as their usability, are also favoured by the furniture. Various waiting possibilities with different types of seating are suitable to favour relations and facilitate control by users, facing outwards to encourage the relationship with nature. Sofas, chairs with tables (low or high), soft seats, armchairs, coloured or wooden chairs, promote familiarity, comfort and privacy (a1, a8, a11, a12, a14, a15, a18, a19, a20). Furniture can also promote identity and attachment with the community, using iconic and local products (a4). The involvement of citizens in the design, as well as for the furniture, can also be encouraged for iconic elements, such as patterns reproduced on the internal and external coverings of the building (a15). Another important role of furniture is to reduce the imbalance that may exist between patient and doctor, for example by the use of curved elements, such as round tables, in which everyone can sit at the same level (a13, a15). Finally, some accessories, such as lockers (a1), can improve user comfort.

According to the staff, brightness in a waiting room positively impacts the waiting experience, especially with regard to mental health. Natural light is preferred where possible, or artificial lighting that is well-diffused and not overwhelming (for example, avoid flickering neon lights). In addition to lighting, openings are very important to ensure natural ventilation, especially when waiting rooms are crowded, and a view of the outside (see next section).

Colours greatly help enliven the environment and make it more aesthetically pleasing. Some colours are ideal for relaxation, such as light blue, while others can create anxiety; in any case, light, not too bright colours, such as red, are preferred. Colours reminiscent of traditional healthcare and institutional environments, such as light green or white, should be avoided. It is suitable to use the same colours for walls and doors.

Materials are very important. For example, wood is a natural, warm, and welcoming material that can be very beneficial in waiting areas. “Curbed lines are also transmitting the same feelings of calm and welcoming”.

These spaces should also convey a sense of cleanliness and order, with linear furnishings. Comfortable sofas or armchairs are preferred for both seating comfort and conviviality. They evoke the idea of a more informal and familiar environment, where, for example, “you could also have a table with magazines to distract yourself while waiting.” The ergonomics of the seats should also be considered to facilitate standing, especially for elderly patients or those with mobility issues. As an example, it is important to have seats with armrests.

However, hygiene, health, and safety standards must always be respected.

According to patients and caregivers, a significant portion of users prefer a familiar environment, through the use of natural materials such as wood and a more homey style of furnishings. Wood, in particular, is appreciated by most people because it “provides warmth,” is “more welcoming, and less cold.” On the other hand, we did not expect a significant percentage (more than half) of people to be so concerned about hygiene and therefore, for this reason, less inclined to use more domestic fabrics or furnishings. They prefer a functional environment, easy to clean, and that “gives a sense of health,” reflecting the function of this space.

Regarding colours, users prefer soft, pastel, bright, and vibrant colours, but not too strong. Almost all users reject white, except for a few who prefer it above all else, as it “gives a sense of cleanliness” and “makes the space seem more open.” In general, blue is highly appreciated because it “relaxes,” “reminds one of the sky,” “of water,” or “of the sea.” Green is also highly appreciated, and some prefer yellow, but only if it’s not too strong, although many say they don’t like it.

Regarding lighting, natural light is preferred by virtually all users, as it “reminds one of being outdoors,” “is more vital and joyful,” and allows one to “maintain a connection with the environment and the passing of time,” except for a few who appreciate the use of coloured lights. As for artificial lighting, soft, not-too-bright, warm, “relaxing” lights are preferred, reproducing outdoor light or modulated at different times of the day.

They don’t like bare spaces, but they also don’t like messy, chaotic spaces that are overcrowded. A modern, linear furnishing style is often appreciated because it’s clean and tidy, but it shouldn’t be too cold. Some prefer single, unpadded chairs, as mentioned, but many instead point to the benefits of using sofas because they’re more comfortable and, above all, more convivial, as they foster social interaction.

3.1.3. Restoration, Sensory Stimulation

Most studies place nature as the major source of restoration, together with art and sensory elements.

The relationship with nature can be promoted in healthcare facilities, both inside and outside. Inside the building, nature can enter the spaces with internal greenery, which makes the space more lively, familiar, healthy and therapeutic (a2, a10), as well as creating a filter through the tallest vegetation, as if they were real “green rooms” (a2). Then, it can be an indirect visual relationship with the surrounding landscape (a1, a6, a11, a14, a15), of green patios and courtyards (a5, a9, a19), or of the sky itself (a19), through glass openings in the waiting and connecting spaces. When it is possible, it is suitable if green courtyards are accessible (a1, a5, a6, a7, a9, a14, a15), allowing a direct relationship with nature, more or less structured, with rest and interaction areas, or spaces equipped for various activities, such as yoga, or children’s playing (a15). This concept can be extended to the entire structure, creating a symbiosis between interior and exterior, in a variety of essences and colours, based on the seasons (a6), through larger and smaller courtyards or green terraces hanging in the volumes (a3, a14, a15, a18), and roof gardens (a6, a18). The design of green courtyards can also be associated with specific functions of the structure (atrium, bar, staff, children, etc.), extending their use outside, and be connected to different sensory stimuli, for example based on the 4 elements earth, air, fire and water (a15). The arrangement of the external greenery is important, both from the point of view of welcoming and involvement of citizens. Greenery at the entrance (a4, a12) or around the building (a17, a20) allows to create both a link and a filter with the urban context, and can be freely used by citizens (a15). It can be equipped with paths and seats (a4), work arts or other elements to encourage interaction and sensory experiences (a12), or connections with other functions such as the café or the waiting area (a18).

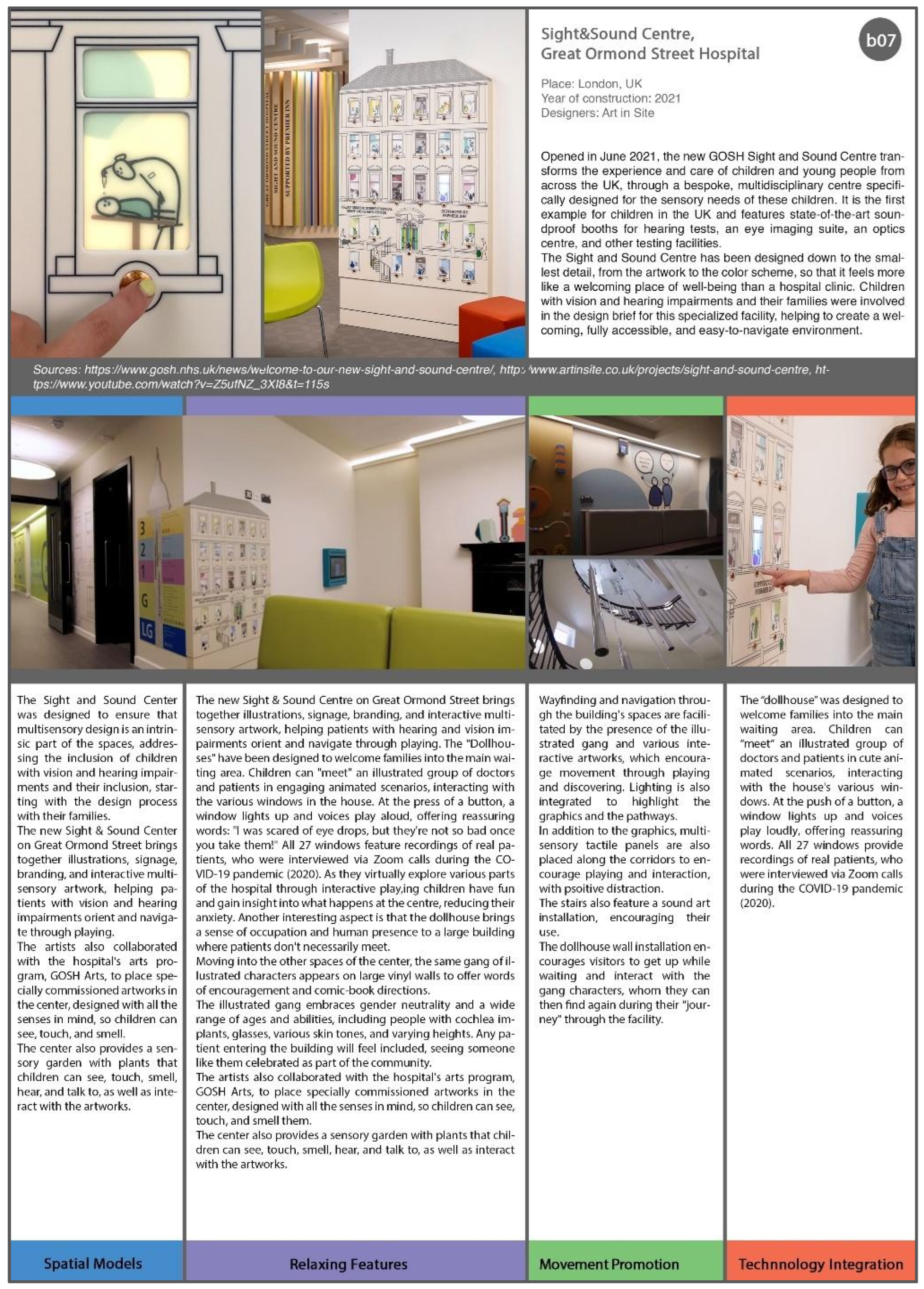

On the other hand, nature can also be transmitted through art, recreated in different artworks, colours and materials (a8), in graphics and illustrations (a14) or as a pattern that recurs throughout the building, also creating a link with the territory and promoting a sense of identity and belonging (a15).

The illustrations can become an integral part of the architecture, completely invested by art (a14, a17). Otherwise the colours can liven up the space, make it less institutional, and favour sensory stimulation (a19, a20). Art can be reproduced in artworks, paintings or sculptures, which invite interaction with the space and positive distraction; facilitate navigation, in focal points of the building such as the entrance or reception, in the waiting rooms or in the paths (a8, a10, a12, a15, a17); create a connection with the city (a3), with sculptures (a10) or street art outside. It is favourable to use artworks by local artists (a12), even creating exhibitions that change (a18), and open after closing the healthcare facility to favour visits and knowledge of the structure by new groups of citizens (a15).

Sensory perception can also be encouraged by dim and coloured lighting, and music, for example by placing a piano (a2) or diffusing sounds and music in the public area. Finally intimate spaces, such as sensory rooms, are suitable to favour relaxation, containment, and sensory rebalancing (a11).

According to the staff, it’s important to create a comfortable, welcoming, intimate, and safe waiting area where people can relax, allowing time to pass without worrying about when their turn will come. “If you feel more relaxed, you’re also a little more cooperative, perhaps more willing to talk and able to clarify, for example, symptoms.” It should be a sort of “decompression room.” “A quiet and serene environment, with comfortable seating, paintings or murals on the walls, succulents (which require no maintenance), and soft lighting.” The idea of “being able to involve local young people in creating the mural and have it donated to seniors, to foster the idea of multigenerationalism and the feeling of belonging”, is interesting. Colour, art, and greenery are all good in all their forms. Green elements keep people active and promote mental health. Even the pathways could be imagined as “tree-lined paths, with a view of greenery in the background, which can convey a message of greater tranquillity and health promotion.”

Projections of landscapes and natural scenery, video screens, or touch screens can distract and relax, refocusing attention elsewhere, as can background music. The music should be “low, non-disturbing (for example, loud sounds can create discomfort in people with dementia or make some people nervous), calm, and possibly instrumental, even better if you can choose based on your preferences,” or “sounds of nature, especially water,” “wind, rain, and animals.” Even objects that can be played and interacted with manually, such as a large chess set, are desirable.

In any case, “whether it’s a game, entertainment, music, or a connection... the important thing is not to feel like you’ve wasted the time you spent waiting.”

“A sensory preparation room can be ideal,” “a relaxing, meditative place where you can be alone, even with and for those accompanying you.” “A place where you can stay for an hour and not feel the need to do anything else, a warm, natural, familiar environment, darkened with curtains,” “illuminated by chromotherapy,” with “video projections for distraction,” “comfortable seating, waterfalls and sounds,” with “water, which also provides a sense of coolness.” Such a space “can also improve pain tolerance,” for example, in the case of invasive tests, “can feel better in case of bad news by the doctor”, “in case of fragility” and for “people with cognitive or behavioural diseases”. In general, a dedicated and “possibly isolated” space is preferred, as it is quieter and more intimate, offering greater privacy; however, some prefer the idea of having sensory elements in a larger waiting room, where they can continue to interact with others, or use a sensory alcove overlooking the waiting area, so as to still be able to isolate themselves somewhat.

As for the staff, art is appreciated by almost all patients/caregivers, as it “distracts”—especially if you’re alone—”stimulates curiosity,” “makes you stop and look,” “makes time pass,” “relaxes and calms,” and “provides a sense of beauty.” Only a few say it “isn’t interesting” or “not relevant,” but no one makes negative comments about it or disdains it.

Nature and the view outside are universally appreciated by all users, as it “is relaxing,” “provides calm,” “openness” and a “sense of respite,” conveys “the idea of being outside,” and allows you to “watch time pass.” Some did, however, mention the importance of seeing the outside, but without having a completely transparent glass wall overlooking the waiting area. This is likely also linked to the cultural context, where it is uncommon to have completely open glass facades.

More controversial is the issue of having greenery within the waiting area; the majority of users appreciate it, but some are concerned about the potential for allergies, the presence of insects, and the potential for dirt caused by plants. Above all, they are concerned about the possibility of inadequate maintenance, which could result in the plants becoming damaged or drying out. This can be addressed by choosing plants that are hypoallergenic, highly durable, and require little maintenance, or by using preserved plants.

For the same reason, although most people prefer real natural elements, some prefer the artificial view of nature, such as through screens or video projections, which “allow your imagination to travel.”

This raises the topic of sensory spaces, which are appreciated by almost all patients, and the majority of caregivers, because they “relax,” “calm,” “relieve anxiety,” “help you sleep,” “distract you, and stop you from thinking.” Many have never experienced a sensory space, so the results may be partially affected by a lack of knowledge. Some refer to the use of this space not only during the wait, but also after the appointment, or for activities such as those of psychologists, or for specific pathologies and vulnerable users.

They also question whether they can truly relax in such a context. For this reason, the majority prefer a separate space, since it is isolated and “makes you feel more at peace,” and more than one person can use it at a time. For the same reason, the sensory pod is less appreciated. Some also raise the issue of hygiene, having to use it promiscuously. Those who generally prefer to isolate themselves appreciate it, as they can remain in the waiting room, yet still be isolated and have an individual experience. In this sense, for example, it can be useful for breastfeeding.

Screens and projections that reproduce natural scenarios are appreciated by almost all users, preferably with background music, as it “distracts and takes you away from your thoughts,” or “travel scenarios that let your imagination soar.”

Music is also appreciated by everyone, but it’s important that it be soft and light, just a background. Some people prefer to be able to choose it; otherwise, relaxing music, classical or instrumental, is generally preferred, along with the sounds of nature, especially water, “like a waterfall, ideally real.”

3.1.4. Sociality Promotion

A mix of functions and a connection with the surrounding territorial and social context should be encouraged. For example, placing healthcare facilities in buildings that also have a residential function (a3, a10), or more public functions such as an atelier/carpentry shop (a3), a gallery to exhibit the work of local artists, a space where local groups meet and a base for neighbourhood initiatives (a18), an area for firefighters (a12), a gym, physiotherapy services, a library (a18), spaces for children (a10) or consultants for family (a18), outdoor spaces also used by citizens, green areas (a3, a4, a10, a12) or market areas (a4), or the urban square itself (a4, a13). Otherwise, another strategy is to connect to functions already existing in the area, such as cafes, or sports facilities (a5), a contemporary art museum, or an arena for outdoor events (a9). In this sense also the choice to locate the structure in a central position in the city (a10) or well connected by public transport, for example by placing itself near the train station (a10).

The public atrium, the street and the courtyards are the point of greatest connection, encouraging meeting and exchange between the different users of the facility and creating a real public space that can be considered similar to a street or a town square (a2, a8, a10, a14, a17, a18, a20), also accompanied by public services and functions such as café, hairdresser (a2), etc.

It is important to create permeability between internal spaces and through paths, to guarantee visibility and favour relations. It can be provided by the use of transparent walls (a19); filters created with wooden slats (a11, a13) or grilled surfaces (a4); walkways, balconies and views of the double volume of the street (a2, a10, a11, a14, a17, a18, a20); corners or seats along the route that foster relationships during stops and passages (a12, a15). Even outside, permeable paths that promote circulation in the form of tunnels, elevated roads where residents meet, children play, plants grow, etc. (a3, are favourable for developing sociality. Finally, the relationship between inside and outside can promote permeability, for example by opening and making the central distribution axis transparent, as if it were an urban road (a4).

Likewise, patios and courtyards are a valid strategy not only to maintain the relationship with the greenery, but also to foster relationships between people, both if they are accessible, creating relaxation and leisure spaces where it is easier to meet and relate with other users (a6, a7, a15), and if they are not, placing waiting areas around the open spaces to promote continuous visibility and permeability (a1 , a5, a9, a19). Internal courtyards can also be enriched by artworks to improve distraction and restoration (a8), and encourage socialization (a2), also organising various activities, such as yoga or games for children (a15). This concept can be extended in the common spaces of the hospital organising various information and awareness-raising activities, distracting and regenerative ones, reading, physical activity, or workshops (a6).

Furniture represent another social strategy, through the use of different seating possibilities to favour usability for different types of users, oriented in various directions, with tables or low tables (a1, a2, a4, a6, a11, a12, a14, a17, a18, a20), to freely choose whether to have privacy or relationships with others. Tables, chairs and workstations with electrical sockets or for public use (a6) can also allow working while waiting (a2). Dedicated staff areas also allow to strengthen the relationship between professionals, especially if characterized by furnishings and materials that encourage familiarity and informality (a17, a18, a20).

In general, according to the staff, it’s very positive to have a convivial environment, “a fertile intergenerational space,” “useful for both patients and caregivers,” since “talking with others allows them to share and discuss their problems and find comfort,” “distraction, reduce tension,” and “support, especially if they are without a caregiver.” For example, “it can be helpful to bring together young people with diabetes, with the aim of getting them to know each other and better accept the situation.” Similarly, sharing is very important for pregnant women, as well as for the elderly, who “often suffer from loneliness and need to talk about their illnesses, grandchildren, etc.” However, it’s important that the waiting room isn’t overcrowded and that “one patient’s anxiety can be transmitted to another.” It could be interesting to have a “living room as a waiting space, where people can feel comfortable, looking outside and talking with other people”.

The majority of patients and caregivers say it’s very important to connect with others while waiting, “especially if you’re alone,” because “seeing people reduces anxiety,” “keeping others company,” “allowing you to hear about other experiences,” and “taking your mind off what you have to do.” Open spaces are best suited for this, as they allow you to choose whether or not to engage in this interaction and “not necessarily find yourself face-to-face.” In any case, it’s important to ensure acoustic comfort, reducing the noise from people talking, “which can be very annoying.” It’s also important to provide “a space for privacy,” depending on the moment and the person’s mood. A pod is a “cozy space” where you can “seclude and isolate yourself.” However, it’s appreciated by only a few patients and less than half of caregivers, as it’s considered “too closed off,” making them feel “excluded and isolated.” Some people expressed their willingness to use the pod for breastfeeding.

3.1.5. Active and Healthy Ageing

Health can be promoted by information panels (a15) or screens, as well as by activities, such as courses. The promotion of physical activity is also important, through spaces dedicated to fitness (a6), green courtyards (a6) and active and social spaces in which to encourage movement.

According to the active design approach, stairs should be highlighted, such as by a scenic shape or a central position (a4, a6, a14, a15, a20), or even through the colour (a8), materials (a4, a11) or lights (a4, a8), encouraging their use; connecting elements can also include games such as a slide (a14). On the contrary, elevators can be positioned in a secondary area compared to the centrality of the staircase (a4, a11).

Slow and green mobility should be favoured through the study of viability (a12), the provision of slow traffic areas (a1), bicycle parking near the entrance (a20), guarded and covered (a3), reducing car parking spaces (a3), charging points for electric vehicles and foldable bicycle (a18), access to public transport (a3).

Healthy food and potable free water should be provided. To promote healthy behaviours, spaces dedicated to awareness-raising of healthy eating (a6) can be provided, also through an educational kitchen where families can learn to cook healthy meals (a15), or a city market with local products (a4).

The staff like very much the idea of promoting health during waiting; the main goal should be “improve patient/caregiver’s knowledge about health and make them feel relaxed after waiting”.

All staff expressed interest in the idea of “information points” where patients could “know where to go,” obtain information on the “needs of seniors,” or generally promote healthy lifestyles, in various forms: video seemed the most suitable solution, through a projection, a monitor, or a touchscreen, which could also be interacted with; posters or “something large on the walls”; and pamphlets and brochures, which could also be “picked up and taken home.” Most, however, preferred something shared over individual tablets. Informing could “be useful for distracting, shifting attention, and passing the time.” It is important to provide information “on nutrition, exercise, and social engagement”; on “prevention, such as smoking cessation, or the promotion of specific diets, which, for example, reduce vascular risk, including by providing recipes”; “education for expectant mothers”; “on gender-sensitive medicine for young people, including by organizing peer training or meetings with the public”; on “other patients’ experiences, through video stories, which can provide reassurance, particularly for young diabetics, to facilitate acceptance of the disease”; “on interventions to be performed or on specific pathologies, such as in-depth analysis, again through videos, of anatomy, since many things are often taken for granted when talking to the patient”; “on how to use the devices”; “on local itineraries that can be taken for patients with mobility difficulties to encourage walks, for example in the woods, which reduce behavioural disturbances.” “Having this information in a quiet, peaceful, and intimate setting is certainly more beneficial.” It would also be interesting if “they could watch these videos both before and after healthcare services, even at home, to prepare or, on the contrary, get suggestions for continuing the treatment.” Language should be simple, and explanations should be “with cartoon-like illustrations” or presented “in a fun, entertaining, and interactive way.”

Similarly, interaction and play can engage people and encourage them to exercise. The idea of “going outside and engaging in physical activity” is particularly positive, combining exercise with the opportunity to “see plants and stimulate the senses,” such as “a walk along a tree-lined avenue,” or a “wellness trail,” even with covered areas. This would be ideal, especially for diabetic patients.

We also discussed the opportunity of using passive training equipment, such as seating elements which make people stay in a position in order to activate the muscles and restore their motor function. As an example, we were showing a picture of MyActiveBench by the Italian company (Metalco s.r.l.) [26], a “standing” seat for correct posture and active muscle tone, specifically designed and conceived for “fast recovery” moments. Anyway, passive training equipment has been less successful, as the staff appear concerned about the safety of using the devices independently, imagining elderly patients and/or patients with mobility issues. However, some are very interested in the idea and have proposed using these devices for caregivers, suggesting including an educational message on how to use them. They are considered more suitable for use in a dedicated physical activity area, especially outdoors, in the area adjacent to the waiting room.

The staff was also divided on the idea of self-testing (physical and cognitive): an interactive screen/projection aiming at making people do individual tests such as getting up from a chair, walking, lifting weights, bending and stretching, etc. [26] to understand their healthy and active ageing level and a dedicated cognitive training interface to experiment their neuro skills. The staff think self-testing can be very useful for some patients (e.g., diabetics), on the other hand there is concern about doing the tests independently, due to the patient’s interpretation of the results and the worry and anxiety it may generate. Some of the tests considered useful, especially thinking about healthy and active aging, are represented by “the test of balance, the analysis of movement, the speed of walking, the memory test”.

The majority of patients and caregivers were interested in having access to information about health promotion. They preferred screens/video projections as a means of communication because they were more immediate and engaging, offering brief, “commercial-like” information, since people don’t read, and shared, thus fostering greater relations. They also referred to multiple shared screens, but not individual tablets that would perform the same function as a phone.

Among patients, those who responded that they preferred not to have this information cited concerns and anxiety about the procedure, preferring to distract themselves while waiting and escape from their current state. Some also preferred to receive this information from the doctor, as it was targeted and “safe.”

Those who proposed using paper-based support instead referred to the possibility of taking the information home for further study at a later time.

The majority of patients reported they would not use passive training equipment, while almost the half of caregivers said they would; this result may also be attributed to the age of the interviewees. In general, several patients stated “they want to be comfortable” while waiting and doing physical activity at home or in the gym, or at most outside, even being intimidated by the idea of doing so in front of other people. Some said they “prefer the idea of a walk rather than sitting in a position like this, as they need to release their anxiety.” Many reported that they do not consider these devices suitable for the elderly.

Regarding movement, the majority of patients and caregivers said they would enjoy playing and interacting with various devices “to pass the time.” Some also enjoyed light physical activity. This is certainly considered beneficial for children. Again, reference is made to the embarrassment of doing these activities in front of others, so they would be happy with a dedicated or screened area.

Finally, regarding the idea of being able to perform self-tests (physical and cognitive), more than half of patients and the majority of caregivers are in favour of using these devices. Many are concerned that they are not interpreted by a professional and therefore do not constitute “serious and reliable information,” “based on a doctor’s instructions.”