1. Introduction

Remote sensing images (RSIs) serve as a vital data source for Earth observation. Semantic segmentation of RSIs, also referred to as land use and land cover (LULC) classification [

1], aims to assign a semantic label to each pixel, enabling pixel-level categorization. LULC classification plays a crucial role in various applications, including urban planning [

2], agricultural management [

3] environmental monitoring [

4], and the development of geographic information system (GIS) [

5].

With advances in sensor technology, the spatial resolution of RSI has significantly improved. High-resolution RSIs (HRRSIs) contain rich texture, geometric, and spectral information [

6], but also exhibit considerable diversity and complexity. These images are characterized by large intra-class variance, small inter-class variance, and low class separability [

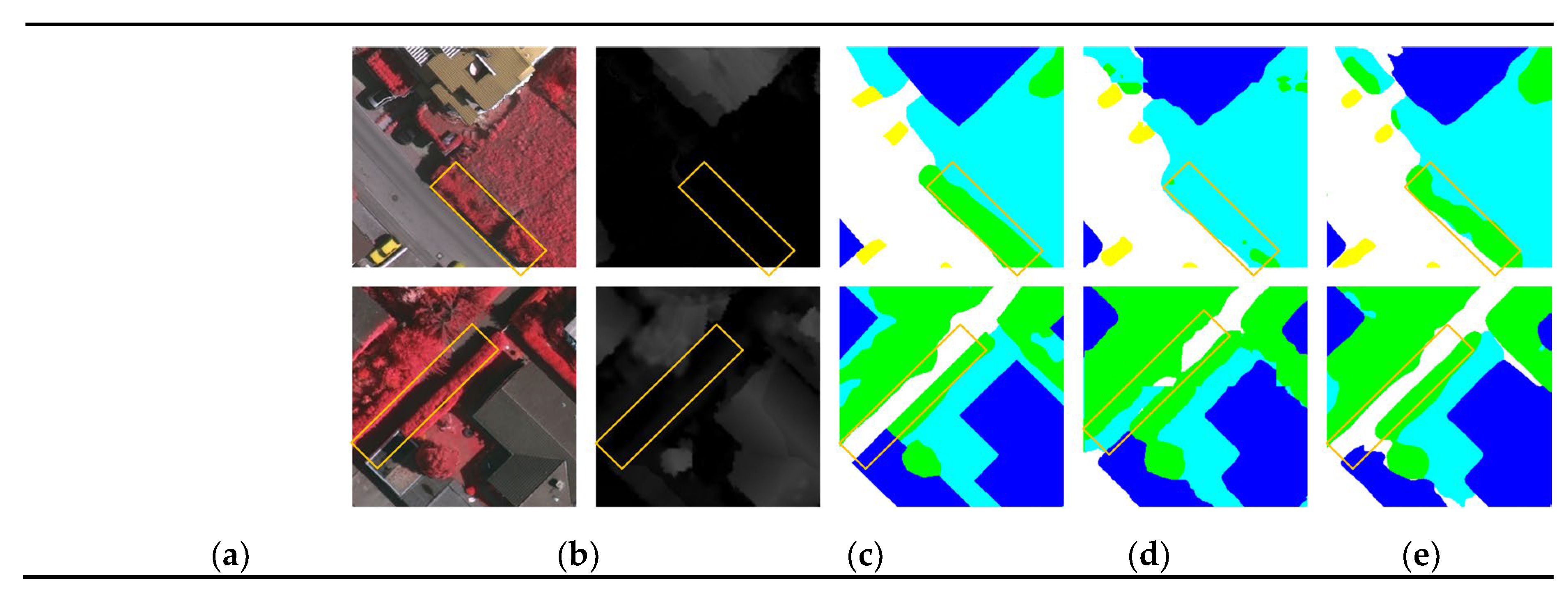

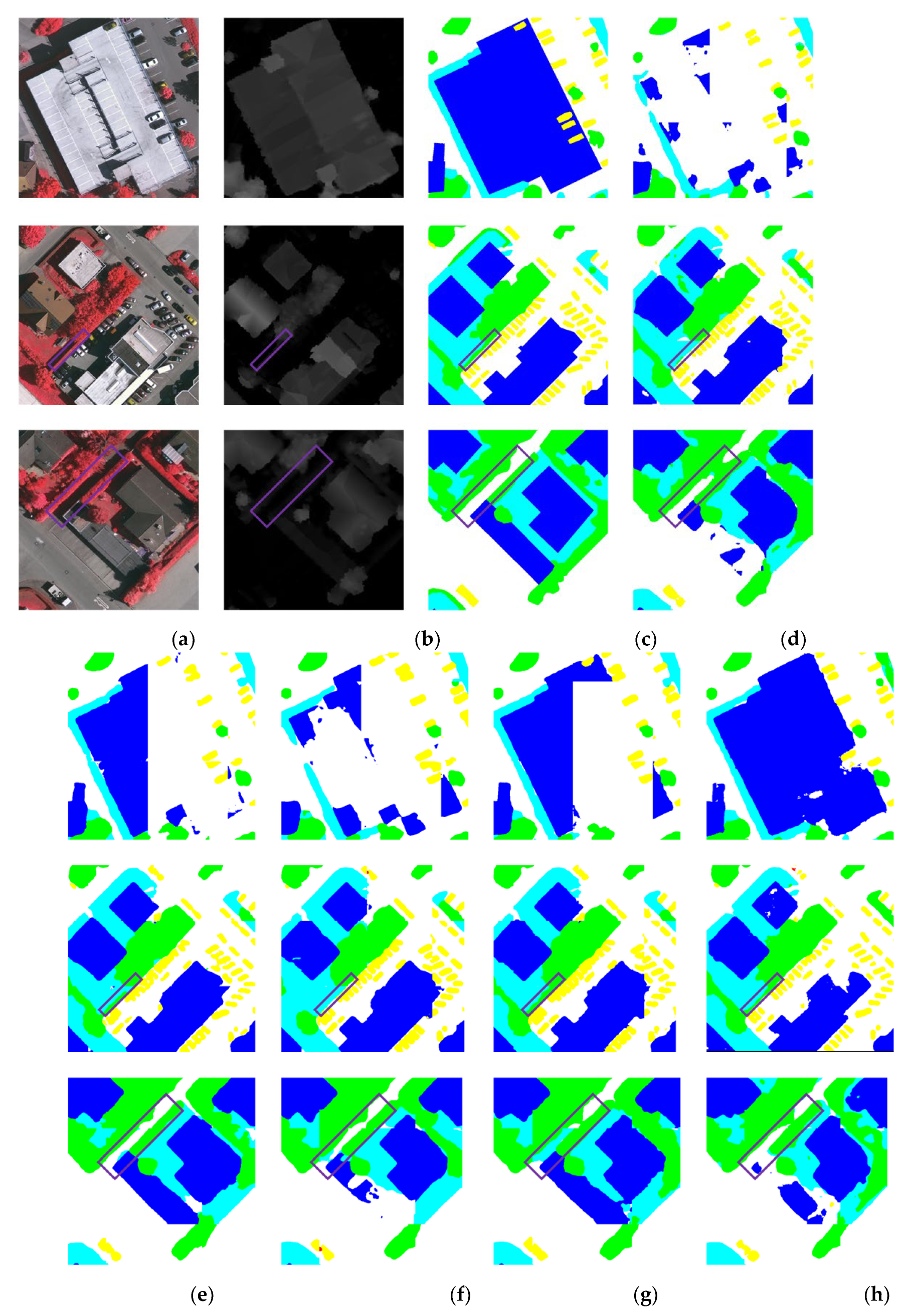

7], posing significant challenges to semantic segmentation tasks—for instance, the difficulty in distinguishing between trees and low vegetation in the first row of

Figure 1. Moreover, shadows in HRRSIs further complicate feature extraction, thereby reducing segmentation accuracy. An example is shown in the second row of

Figure 1, where shadowing impedes the identification of a path between tree canopies [

8].

Compared with unimodal approaches, multimodal semantic segmentation (MSS) integrates diverse remote sensing sources—such as digital surface models (DSMs), multispectral, panchromatic, and radar data—to exploit complementary information across modalities, thereby improving segmentation accuracy [

9]. For instance, DSMFNet [

10] introduces a DSMF module that extracts informative features from DSM data to enhance segmentation performance in shadowed regions or areas with similar colour and texture. CMGFNet [

11] employs a Gated Fusion Module (GFM) to adaptively combine features from different modalities while suppressing redundancy. Similarly, CMFNet [

12] uses a cross-attention mechanism to fuse multimodal features at multiple scales, achieving cross-modal integration with multiscale awareness.

Most existing multimodal segmentation networks, however, rely on convolutional neural networks (CNNs) [

13] or vision transformer (ViT) [

14] as backbone architectures. CNNs excel at extracting local features due to their local connectivity and weight sharing, but their limited receptive field constrains their ability to model global context [

15]. ViT [

14], on the other hand, offer stronger long-range dependency modelling, but their quadratic computational complexity hinders their applicability to high-resolution imagery [

16]. Thus, multimodal segmentation models based on CNNs or ViT face a fundamental trade-off between capturing global context and maintaining computational efficiency.

Mamba [

17], a variant of the State Space Model (SSM), was originally introduced for natural language processing. It offers the capability to model long-range dependencies while maintaining linear computational complexity. Its successful adaptation to RSI segmentation, as demonstrated by Vim [

18] and VMamba [

19], highlights its potential as an alternative to Transformer-based architectures. Sigma [

20] represents the first attempt to apply SSMs to multimodal segmentation, proposing an end-to-end network entirely built upon the Mamba architecture. Specifically, Sigma adopts VMamba as the feature extraction backbone and designs two Mamba-based fusion modules, Cross Mamba Block (CroMB) and Concat Mamba Block (ConMB), to facilitate cross-modal interaction. Despite Mamba’s strength in capturing long-range dependencies, it performs suboptimally in segmenting small-scale objects. To address this limitation, MFMamba [

21] combines CNN and VMamba backbones to separately extract multimodal features. It incorporates a Feature Fusion Block (FFB) to enhance both global and local modality-specific features, which are then aggregated via element-wise addition. While this approach effectively captures multi-scale global and local features, it remains susceptible to information loss and feature misalignment, particularly in complex remote sensing scenes with large inter-modal differences.

In summary, several challenges persist in MSS of RSI:

(1) Balancing accuracy and efficiency. MSS is a dense, pixel-level classification task. Current approaches often adopt dual-encoder frameworks based on CNNs and Transformers to capture local and global semantic features, respectively. However, Transformer-based methods incur substantial computational overhead, making it difficult to achieve both high accuracy and computational efficiency.

(2) Effective multimodal feature fusion. Most existing methods perform feature fusion through concatenation or element-wise addition. However, when significant differences exist between modalities, such strategies may lead to information loss and feature misalignment. Moreover, redundant information may be introduced, amplifying the impact of image noise and ultimately degrading segmentation accuracy [

22].

To address these challenges, we propose MMFNet, a multimodal dual-encoder fusion network based on the Mamba architecture. In this framework, The primary encoder adopts ResNet-18 [

23] to extract local features, while the auxiliary encoder replaces Transformer with VMamba to capture global semantic features. It strikes a balance between accurate long-range dependency modelling and computational efficiency. To facilitate cross-modal interaction between the two encoders and to exploit complementary information across modalities, we introduce a multimodal feature fusion block (MFFB) at each feature extraction stage. This module integrates global and local information using multi-kernel convolution and window-based cross-attention, ensuring effective fusion of multimodal features.

In the decoder stage, to better integrate deep and shallow features both semantically and in the frequency domain, We employ FreqFusion [

24], a frequency-aware guided upsampling method, as a replacement for conventional feature fusion techniques. This approach enhances the restoration of fine spatial details and contributes to improved segmentation accuracy. In summary, the main contributions of this study are as follows:

A novel MFFB is designed to extract complementary features across modalities. The local branch captures fine-grained details using multi-scale depthwise separable convolutions, while the global branch employs Efficient Additive Attention [

25] to model global contextual information. These are further integrated via window-based cross-attention to enable effective interaction between local and global representations.

A frequency-aware guided upsampling method (FreqFusion) is introduced in the decoder stage to replace traditional upsampling strategies. This facilitates semantic fusion of deep and shallow features and enables finer reconstruction of spatial details.

Extensive experiments conducted on the ISPRS Vaihingen and Potsdam datasets demonstrate that MMFNet achieves superior segmentation performance compared to eight state-of-the-art methods, while maintaining low computational complexity.

3. Methodology

3.1. Framework of MMFNet

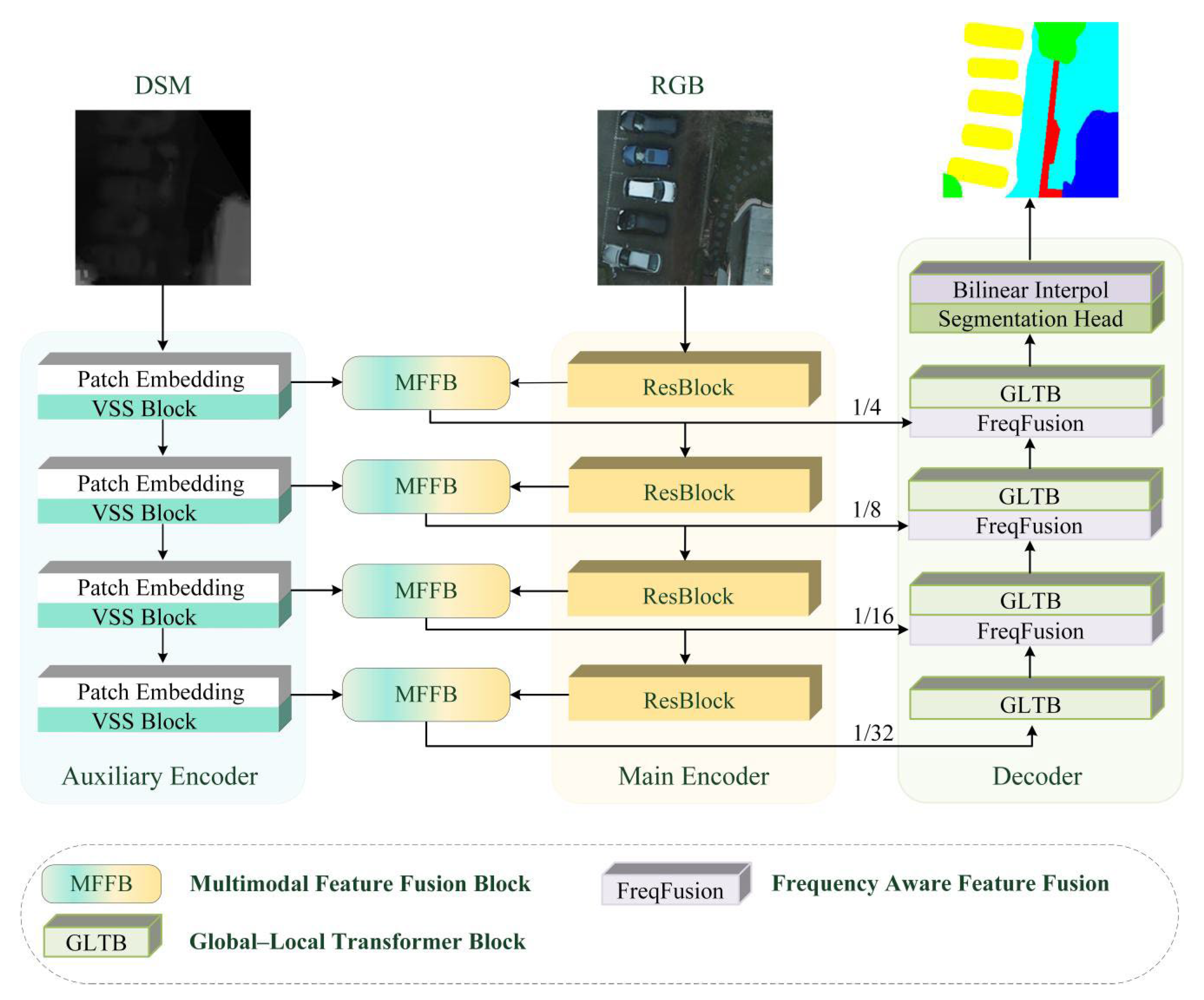

As illustrated in

Figure 2, the overall architecture of MMFNet follows the design of MFMamba and consists of four main components: a primary encoder, an auxiliary encoder, a feature fusion module, and a decoder. The primary encoder adopts ResNet-18, which focuses on capturing fine-grained local details, while the auxiliary encoder employs VMamba to provide complementary global context to the features extracted by ResNet-18.

The feature fusion module integrates multimodal features at each stage of the encoding process to generate multi-scale, multimodal representations. In MFMamba, feature fusion is implemented using the FFB. However, its element-wise addition strategy may cause information loss or feature misalignment when modality-specific characteristics differ significantly.

To address this limitation, we propose a novel MFFB, which incorporates both global and local branches to capture complementary information across modalities. A window-based cross-attention mechanism is employed within the fusion process to enable rich cross-modal interaction. This strategy facilitates the modelling of both intra- and inter-modal dependencies, allowing for more effective multimodal feature integration.

The decoder is responsible for restoring spatial details from the high-level features generated by the encoder, enabling precise segmentation. While MFMamba adopts bilinear upsampling, its fixed interpolation weights are not adaptive to varying semantic regions, leading to blurred boundaries in cross-scale feature fusion. To overcome this, we replace bilinear interpolation with FreqFusion in the decoder stage. FreqFusion performs frequency-domain decomposition to achieve adaptive fusion between deep and shallow features, thereby improving boundary sharpness in segmentation results.

3.2. Dual Branch Encoder

As shown in Figure 2, MMFNet adopts a dual-encoder architecture that facilitates multimodal feature extraction through the coordinated operation of a primary encoder based on ResNet-18 and an auxiliary encoder based on VMamba. The ResNet-18 encoder focuses on capturing local detail features, while the VMamba encoder—built upon the SSM—models’ global contextual information. Together, they form a complementary encoding framework that enables the effective representation of both fine-grained and long-range semantic features.

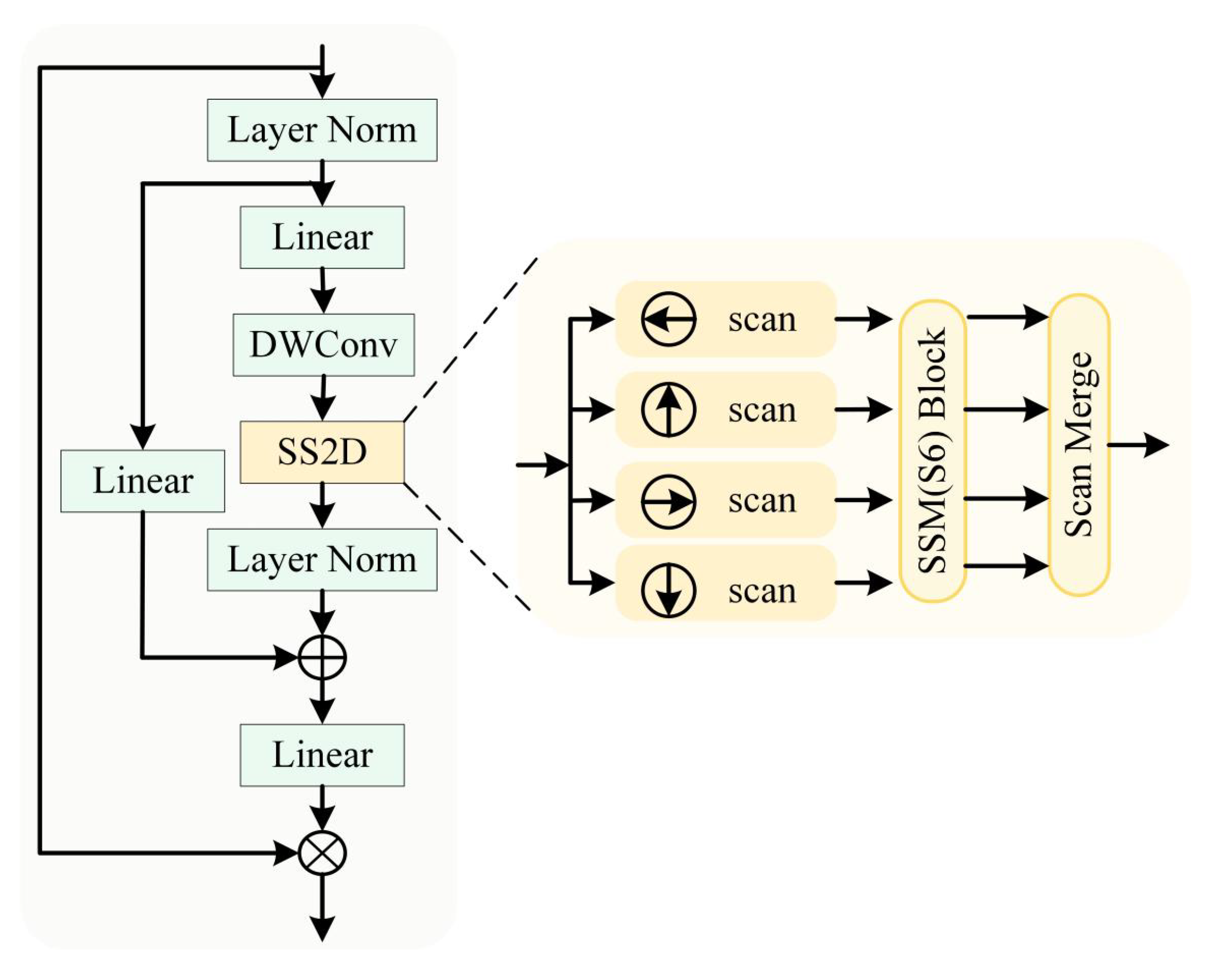

The primary encoder consists of four stages of residual blocks (ResBlocks). At each stage, features are enhanced by MFFB and then forwarded to the decoder. The auxiliary encoder is constructed using the Visual State Space (VSS) module (as shown in

Figure 3), whose core component is the Selective Scanning 2D (SS2D) mechanism. SS2D enables efficient long-range dependency modelling through multi-directional sequential scanning and state space transformation.

The auxiliary encoder also comprises four stages. It performs hierarchical downsampling through patch embedding and patch merging operations, while the integrated VSS modules progressively learn global semantic representations across scales.

This architectural design integrates the strengths of CNNs in local feature extraction with the global semantic modelling capabilities of Mamba, enabling an effective mechanism for collaborative representation of multimodal features.

3.3. Multimodel Feature Fusion Block

Fusion methods based on simple concatenation or alignment often fail to fully exploit the complementary characteristics of cross modal data [

42] while also neglecting the long-range dependencies between multimodal inputs [

43]. Moreover, inherent noise and redundant features may further degrade the quality of feature representation [

10].

To effectively model both intra-modal and inter-modal dependencies, and to extract modality-specific as well as modality-shared features, we design the MFFB. As illustrated in

Figure 4, MFFB consists of three main components: a local branch, a global branch, and a window cross attention (WCA) module. The local and global branches are responsible for capturing the detailed or global features that may be lacking in certain modalities, while the WCA module models cross-modal dependencies to obtain complementary features across modalities.

The MFFB takes as input the feature maps F

Ri from the CNN-based primary encoder and F

Vi from the VSS-based auxiliary encoder. Due to the limited receptive field of CNNs, the feature maps F

Ri from the primary encoder lack sufficient global context. Conversely, although Mamba excels at modelling long range dependencies, it is less effective in capturing fine-grained local details, resulting in relatively coarse representations in F

Vi from the auxiliary encoder. To integrate the global and local features from F

Ri and F

Vi, MFFB processes F

Ri through the global branch, where Efficient Additive Attention (for details, see [

25]) is applied to extract global contextual features F

Global.

Simultaneously, F

Vi is passed through the local branch, where three convolutional layers with different kernel sizes are used to capture fine-grained local features F

Local. The outputs of the global and local branches are then fused via the WCA module, as illustrated in

Figure 4.

To avoid the high computational cost of global attention, both F

Local and F

Global are first partitioned into non-overlapping windows of size 7×7. These windowed features are then passed through linear layers to generate the corresponding queries (Q), keys (K), and values (V), which are subsequently used to compute the cross attention. This process can be expressed by Equation (1), (2) and (3) as:

here,

denotes the relative positional bias, while

represent the query, key, and value matrices, respectively;

d refers to the dimensionality of the query/key vectors, and W is the window size.

The WCA model performs cross attention computation within each local window. By modelling cross modal dependencies in a windowed manner, WCA effectively captures complementary features across modalities with reduced computational overhead.

3.4. Transfomer Decoder

HRRSI poses significant challenges for object recognition and localization due to its high spatial resolution, dense object distribution, and wide variations in object scale. Therefore, the combination of global context and fine spatial detail is critical for reliable semantic reasoning in HRRSI [

43]. Although encoder–decoder architectures such as U-Net integrate shallow high-resolution features with deep semantic representations via skip connections, their decoders typically rely on fixed interpolation kernels—such as Bilinear Interpolation or Nearest Neighbor Interpolation—which are insufficient for capturing the rich contextual information required for accurate semantic reasoning. To address this limitation, FreqFusion [

24] introduces an adaptive frequency-domain upsampling strategy. Specifically, it applies adaptive low-pass filtering to upsampling deep (low-resolution) features by suppressing high-frequency noise and maintaining semantic consistency. A displacement generator is further used to perform spatial alignment. Meanwhile, adaptive high-pass filtering is applied to enhance boundary details in shallow (high-resolution) features, compensating for the loss of high-frequency information during downsampling. This enables complementary fusion of deep and shallow features in the frequency domain.

The decoder in this study adopts a hybrid architecture combining global local transformer block (GLTB) and FreqFusion. GLTB employs a multi-scale attention mechanism to simultaneously capture long-range dependencies and local spatial details. FreqFusion performs frequency-aware upsampling on deep (low-resolution) features and utilizes an adaptive frequency filtering mechanism in the spatial domain to achieve complementary fusion of deep and shallow features in terms of both semantic consistency and fine-grained detail. Further details of GLTB and FreqFusion can be found in [

24,

34].

3.5. Loss Function

We employ the cross-entropy loss to supervise the training of the network, which is defined as follows:

where

ti denotes the GT, and

pi is the softmax probability of class

i.

4. Experiment and Results

4.1. Dataset

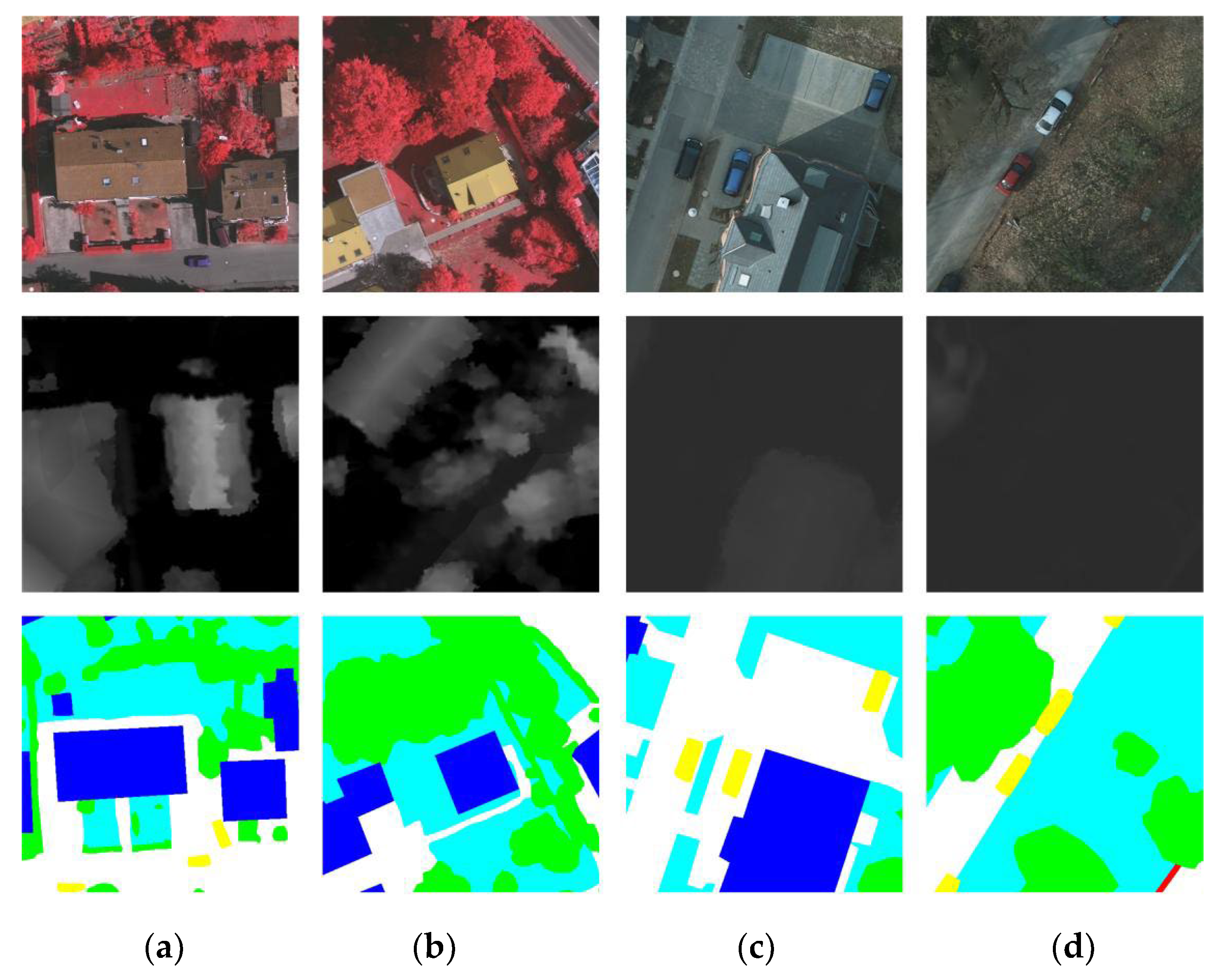

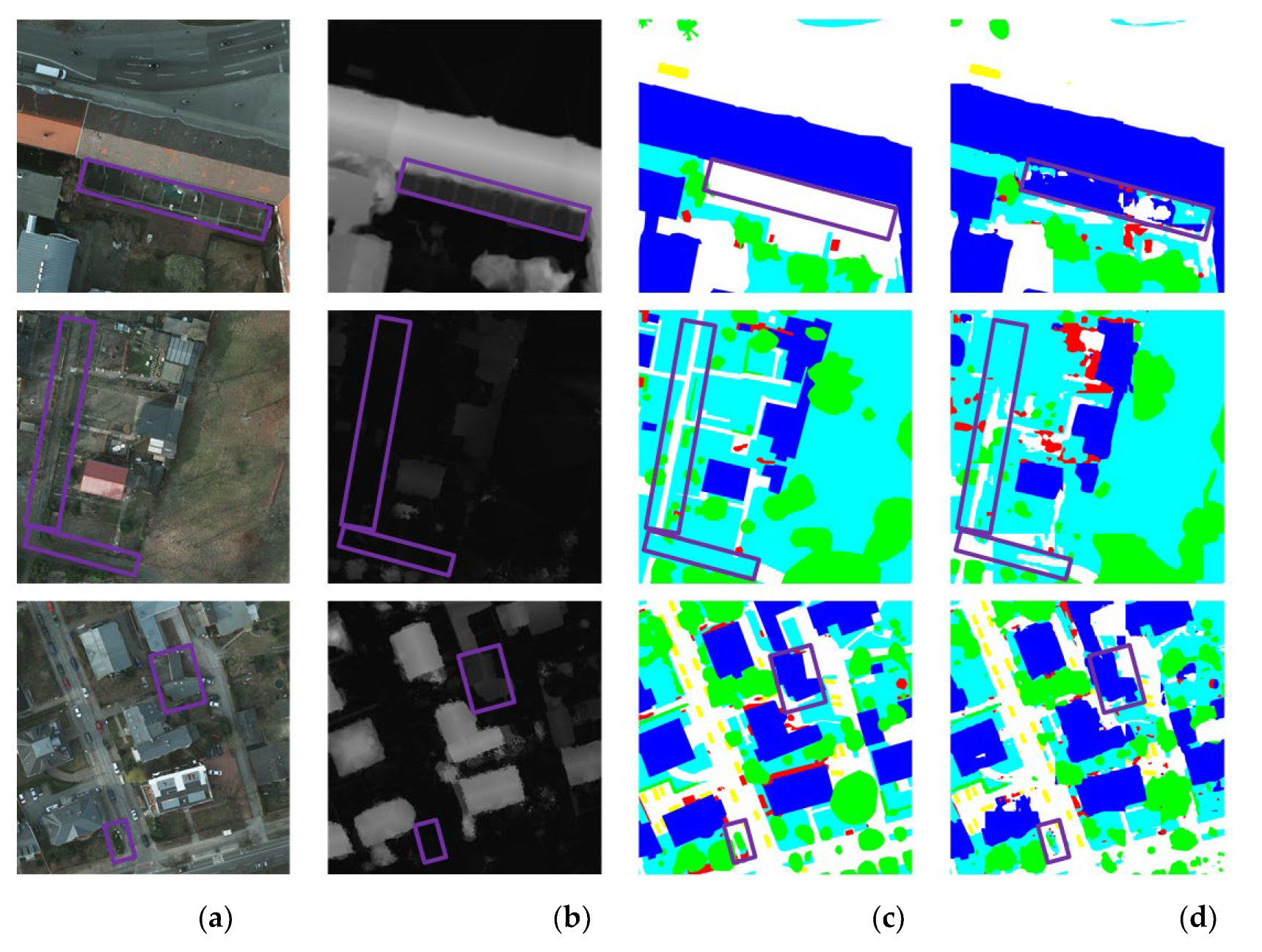

1) Vaihingen: Vaihingen dataset consists of 16 high-resolution true orthophoto images, each with an average size of approximately 2500 × 2000 pixels. Each image contains three spectral channels—near-infrared (NIR), red, and green (NIRRG)—as well as a DSM with a ground sampling distance (GSD) of 9 cm. The dataset includes five foreground classes: building (Bui.), tree (Tre.), low vegetation (Low.), car, and impervious surface (Imp.), as well as one background class: clutter. In our experiments, we utilized TOP image tiles and complete images. The 16 images are divided into a training set of 12 images and a test set of 4 images. The training set includes image IDs: 1, 3, 23, 26, 7, 11, 13, 28, 17, 32, 34, and 37; the test set comprises images 5, 21, 15, and 30.

2) Potsdam: Potsdam dataset consists of 24 high-resolution aerial images captured over the city of Potsdam, Germany, each with a resolution of 6000 × 6000 pixels and a GSD of 5 cm. It provides four multispectral channels, including infrared, red, green, and blue (IRRGB), along with a DSM at the same 5 cm GSD. The dataset shares the same semantic classes as the Vaihingen dataset. In our experiments, we use the RGB composite images together with the corresponding DSM data. The dataset is divided into 18 images for training and 16 images for validation or testing. The training set comprises the following image IDs: 6_10, 7_10, 2_12, 3_11, 2_10, 7_8, 5_10, 3_12, 5_12, 7_11, 7_9, 6_9, 7_7, 4_12, 6_8, 6_12, 6_7, and 4_11. The test/validation set includes: 2_11, 3_10, 6_10, 7_10, 2_12, and 3_11.

Figure 5 presents some data samples from the Vaihingen and Potsdam datasets.

4.2. Evaluation Metrics

To quantitatively assess the performance of segmentation, we adopt four commonly used metrics: Intersection over Union (IoU), mean IoU (mIoU), overall accuracy (OA), and mean F1-score (mF1). These metrics are computed based on four fundamental quantities: true positives (TP), true negatives (TN), false positives (FP), and false negatives (FN).

For each class, IoU is defined as the ratio between the intersection and the union of the predicted and GT regions, and is calculated as follows:

The F1-score for each class is calculated as follows:

The precision for each class is calculated as follows:

The recall for each class is calculated as follows:

In addition, mIoU refers to the average IoU across all classes, and mF1-score denotes the mF1 calculated over all categories.

4.3. Experiment Setup

All experiments were implemented using PyTorch and conducted on a single RTX 4080 GPU. During training, images were randomly cropped into 256 × 256 patches, and data augmentation techniques such as random horizontal flipping, random vertical flipping, and random rotation were applied. The number of training epochs was set to 50.

The model was optimized using Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) with a learning rate of 0.01, a momentum of 0.9, a weight decay of 0.0005, and a batch size of 16.

4.4. Experimental Results and Analysis

4.4.1. Comparison Results on the Vaihingen Dataset

As shown in

Table 1, the proposed MMFNet achieves the highest scores on the Vaihingen dataset in terms of OA, mF1, and mIoU. Compared with the baseline MFMamba, MMFNet shows consistent improvements of 1.59% in mF1 and 2.04% in mIoU, demonstrating its ability to effectively extract and fuse complementary features from DSM and HRRSI data. In comparison with existing SOTA methods, MMFNet also delivers superior segmentation performance in key categories such as building, tree, low vegetation, and impervious surface. Specifically, it achieves an increase of 2.41% in IoU for low vegetation and 1.21% in IoU for car over the baseline, further highlighting its advantage in modelling fine-grained multimodal features.

Figure 6 presents visual comparisons of the segmentation results obtained by the nine methods. In the first and second rows, several single-modality models misclassify regions within buildings as impervious surfaces. In contrast, our method and CMFNet yield the most accurate building predictions. In the second row, the building contours predicted by our model are more consistent with the GT, exhibiting smoother and more complete edges. This demonstrates the ability of MMFNet to more precisely segment large-scale structures. Additionally, within the dashed box in the second row, MMFNet successfully identifies trees located within areas of low vegetation, whereas other methods (

Figure 6 (

d)–(

k)) either miss or partially detect them. This result highlights MMFNet’s superior effectiveness in addressing the challenge of inter-class similarity. In the third row, the dashed box marks a region where shadows cast by trees on both sides of the road alter the appearance of the surface in RGB images, making the road’s color and texture significantly different from the surrounding areas. As a result, most comparison methods misclassify the region. However, MMFNet accurately distinguishes the road from adjacent trees, demonstrating its robustness in mitigating the adverse effects of shadow occlusion.

4.4.2. Comparison Results on the Potsdam Dataset

The experimental results on the Potsdam dataset are consistent with those on the Vaihingen dataset, where our method achieves the highest scores in terms of OA, mF1, and mIoU. Compared with the baseline MFMamba, our method improves OA, mF1, and mIoU by 0.43%, 0.39%, and 0.65%, respectively. Notably, it also demonstrates superior segmentation performance in key categories such as building, tree, low vegetation, and impervious surface when compared with other SOTA methods. Specifically, our method yields an improvement of 1.45% in IoU for low vegetation and 0.81% in IoU for buildings over the baseline.

Table 2.

Comparison results with other methods on the Potsdam dataset (Unit: %). Bold numbers indicate the optimal value, and underlined numbers represent the sub-optimal value.

Table 2.

Comparison results with other methods on the Potsdam dataset (Unit: %). Bold numbers indicate the optimal value, and underlined numbers represent the sub-optimal value.

| Model |

Backbone |

IoU |

OA |

mF1 |

mIoU |

| Imp. |

Bui. |

Low. |

Tre. |

Car |

| PSPNet |

Resnet-18 |

78.98 |

88.93 |

68.23 |

68.42 |

77.77 |

86.12 |

82.51 |

76.47 |

| Swin |

Swin-T |

79.28 |

90.5 |

69.98 |

70.41 |

79.64 |

87.05 |

83.69 |

77.96 |

| Unetformer |

Resnet-18 |

84.51 |

92.08 |

72.70 |

71.42 |

83.45 |

89.19 |

89.20 |

80.83 |

| DCSwin |

Swin-T |

82.96 |

92.50 |

71.31 |

71.24 |

82.29 |

88.31 |

88.71 |

80.06 |

| CMFNet |

VGG-16 |

85.55 |

93.65 |

72.23 |

74.65 |

91.25 |

89.97 |

91.01 |

83.37 |

| Vmamba |

Vmamba-T |

84.82 |

91.24 |

75.16 |

75.38 |

88.04 |

81.52 |

90.40 |

82.93 |

| RS3Mamba |

R18-Mamba-T |

86.95 |

94.46 |

75.50 |

76.28 |

92.98 |

90.73 |

87.39 |

85.24 |

| MFMamba |

R18-Mamba-T |

87.34 |

94.90 |

75.09 |

76.81 |

92.88 |

90.89 |

91.92 |

85.41 |

| Ours |

R18-Mamba-T |

87.41 |

95.71 |

76.54 |

77.50 |

93.13 |

91.32 |

92.31 |

86.06 |

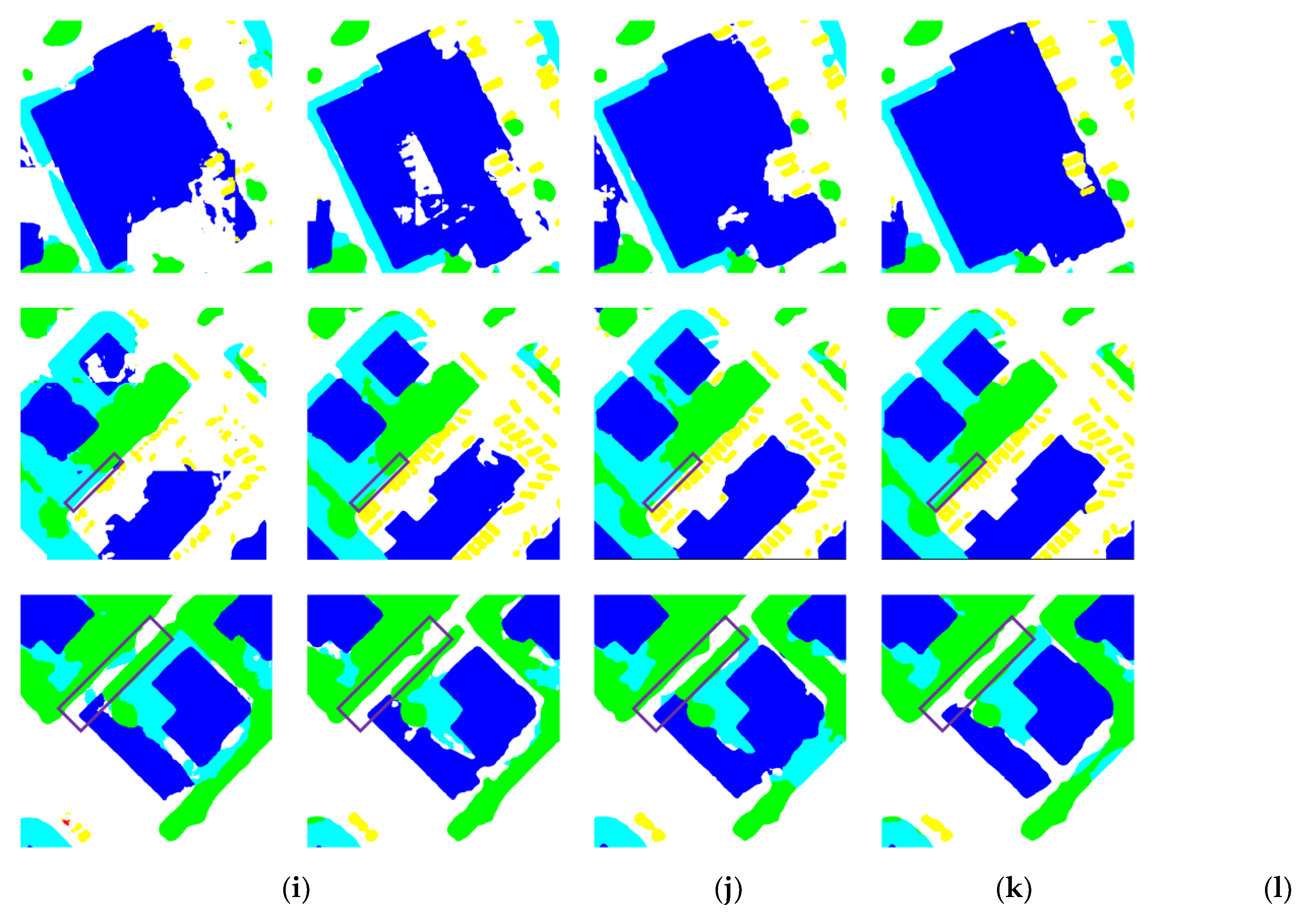

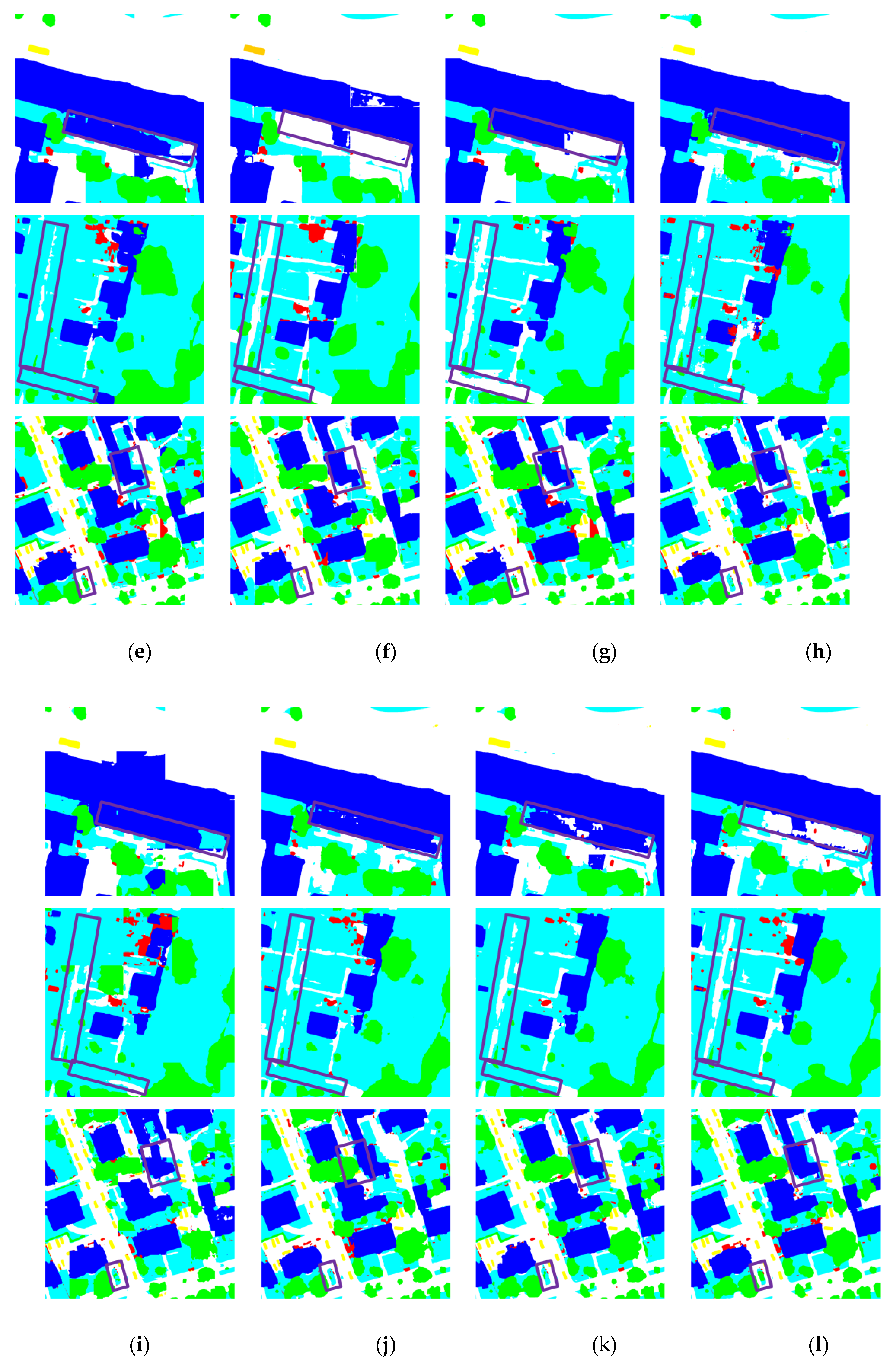

Figure 7 presents visual examples of the segmentation results produced by all nine methods on the Potsdam dataset. Although the performance differences in terms of OA and mIoU are not particularly large, our method shows noticeably better performance in segmenting large buildings and visually confusing regions compared to other networks. As shown in the top-right rectangular windows of the first and third rows, MMFNet is able to accurately identify the entire building structure, whereas other methods produce fragmented results or mistakenly classify other objects as buildings. From the rectangular boxes in the second and third rows, it is evident that our method performs better in confusing areas than the others. In the second row, the road highlighted in the rectangular window is narrow and surrounded by dense vegetation, making it easy to be confused with the surrounding vegetation. MMFNet successfully distinguishes the road from the vegetation, while other methods tend to confuse the two. Low vegetation and trees are also commonly confused due to their inter-class similarity. In the bottom-left rectangular box of the third row, where trees are surrounded by low vegetation, MMFNet is able to accurately separate the two categories, whereas other methods tend to confuse them.

4.4.3. Computational Complexity Analysis

We adopt floating point operations (FLOPs) and the number of model parameters as evaluation metrics to assess the computational complexity of the proposed MMFNet. FLOPs serve as an indicator of the time complexity of deep learning-based models, while the parameter count quantifies model size.

Table 3 presents the complexity analysis results for all comparison methods in this study.

As shown in

Table 3, although UnetFormer has the lowest FLOPs and parameter count, its mIoU score is significantly lower than that of our model. Compared with Transformer-based multimodal methods such as CMFNet, MMFNet achieves a substantial reduction in FLOPs and requires fewer parameters while maintaining superior mIoU performance. This efficiency is primarily attributed to the use of Mamba as the auxiliary branch in the encoder, in contrast to Transformer, which is typically more resource-intensive.

When compared with MFMamba, another multimodal method based on RS3Mamba, MMFNet has a larger number of parameters, but the FLOPs remain the same, and the segmentation performance is significantly improved. Compared to single-modality segmentation methods, the computational complexity of our model is slightly higher due to the incorporation of multimodal data, yet it achieves notably better segmentation performance. Furthermore, relative to the baseline RS3Mamba, MMFNet yields substantial improvements in segmentation accuracy with only a modest increase in the number of model parameters.

4.5. Ablation Studies

To evaluate the effectiveness of incorporating DSM data, we conduct ablation experiments by setting the input to HRRSI only and HRRSI+DSM on Vaihingen and Potsdam datasets. As shown in

Table 4, the inclusion of DSM data leads to overall performance improvements of MMFNet on both datasets. In particular, the most significant gains are observed in the segmentation of impervious surfaces and buildings, which can be attributed to the stable elevation characteristics of these classes.

However, the segmentation accuracy for low vegetation and trees shows slightly different trends across the two datasets. Specifically, the inclusion of DSM improves the performance of MMFNet on low vegetation in the Vaihingen dataset but reduces its accuracy on trees. Conversely, in the Potsdam dataset, adding DSM decreases the performance on low vegetation but enhances the segmentation of trees. This may be due to the strong spectral similarity between these two classes, along with their highly irregular structures and ambiguous boundary shapes. These results suggest that while DSM contributes to improved overall segmentation performance, distinguishing between trees and low vegetation remains a challenge due to their inherent inter-class similarity and spatial complexity.

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed WCA module and the integration of FreqFusion, we conduct ablation experiments by comparing the model performance with different components added. The evaluation results are summarized in

Table 5, where a tick (√) indicates that the corresponding module is included. The first row of

Table 5 presents the ablation result for FreqFusion, where bilinear interpolation is used to upsample feature maps instead of the proposed frequency-aware method. The second row shows the ablation result for WCA. In this setting, the structure of MFFB is retained, but the fusion operation is modified: the local feature F

Local and the global feature F

Global are fused via element-wise addition without the WCA module.

The results in the first and third rows demonstrate that FreqFusion enables effective complementary fusion between deep and shallow features. The notable improvements in global semantics (e.g., building) and local details (e.g., low vegetation) suggest that this module enhances the model’s capability to represent multi-scale features.

The results in the second and third rows confirm that the WCA module improves semantic understanding in complex scenes by adaptively fusing depth and RGB features. The performance gains for confusing categories such as low vegetation indicate that WCA enhances the quality of cross-modal feature interaction.

Overall, the third-row results show that both components contribute positively to model accuracy, and their combination yields the best performance.

The results in the first and third rows demonstrate that FreqFusion enables complementary fusion between deep and shallow features. The significant improvements in global semantics (building) and local details (low vegetation) indicate that this module enhances the model’s ability to represent multi-scale features. The results in the second and third rows verify that the WCA module improves semantic understanding in complex scenes by adaptively fusing DSM and HRRSI features. The observed improvements in confusing categories such as low vegetation suggest that WCA enhances the quality of cross-modal feature interaction. Overall, the third row confirms that both components contribute positively to model accuracy, and their combination yields the best performance.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we proposed MMFNet, a Mamba-based MSS network for remote sensing, designed to address the challenges of complex scene understanding, multimodal feature fusion, and computational efficiency. By integrating the strengths of CNN and Mamba architectures, MMFNet effectively leverages high-resolution spectral information (HRRSI) and DSM data to improve segmentation accuracy while maintaining low computational complexity. To better fuse multimodal features, we introduced the MFFB, which employs a window-based cross-attention mechanism to achieve adaptive fusion across modalities. This design effectively alleviates the insufficient interaction between global and local information in traditional approaches. Additionally, a frequency-aware upsampling module is incorporated into the decoder to reduce the loss of spatial detail during conventional upsampling and to facilitate semantic fusion of deep and shallow features, thereby enhancing edge segmentation accuracy. Compared to existing CNN or Transformer based methods, MMFNet offers a novel perspective for semantic segmentation of multimodal RSI. Experimental results on two public benchmarks ISPRS Vaihingen and Potsdam demonstrate that MMFNet outperforms eight state-of-the-art methods in segmentation performance, while maintaining relatively low computational cost.

Nonetheless, due to differences in imaging mechanisms, feature misalignment between DSM and RGB (IRRG) data can lead to misclassification in the segmentation results. In future work, we plan to explore cross-modal feature alignment techniques to more effectively exploit the complementary information across modalities and further improve the segmentation accuracy of HSRSI.